Abstract

This study investigated the association between nocturnal oxygen desaturation, muscle quality, and functional performance in individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), with and without coexisting Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSAS). Forty-four participants (COPD: n = 22; COPD-OSAS: n = 22) underwent a standardized three-day evaluation protocol comprising: (1) clinical assessment, body composition analysis, and pulmonary function testing; (2) cardiac function evaluation and home sleep monitoring; and (3) handgrip strength (HGS) and six-minute walk test (6MWT). Muscle quality was operationalized as the ratio between appendicular skeletal muscle mass and isometric strength. Sleep parameters, including the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) and oxygen desaturation index (ODI), were obtained via home polysomnography. Patients with COPD-OSAS showed significantly reduced 6MWT distance and HGS values compared with those with isolated COPD (p < 0.05). Indices of sleep-disordered breathing exhibited significant inverse associations with functional performance and muscle quality. In multivariable regression, sex, AHI, and ODI were identified as independent predictors of muscle quality, with ODI representing the strongest contributor after adjustment. These findings indicate that individuals with COPD-OSAS present greater impairments in muscle quality and physical performance, and that hypoxic burden is closely related to these outcomes. Further studies with larger cohorts and longitudinal designs are needed to elucidate underlying mechanisms and to determine the long-term clinical implications of these associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a respiratory disorder characterized by progressive airflow limitation, often accompanied by abnormal pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses1. The progression and severity of COPD increase morbidity, mortality and health care costs2. Additionally, skeletal muscle dysfunction is one of the most significant extrapulmonary manifestations of COPD, negatively affecting patients quality of life. This dysfunction is characterized by loss of muscle mass, strength, and power, as well as the reduction of oxidative muscle fibers, capillary rarefaction and mitochondrial dysfunction3,4,5,6,7.

COPD is frequently associated with multimorbidity, with sleep-disordered breathing further exacerbating disease-related comorbidities8. Ventilatory control in patients with COPD follows the similar principles to those in healthy individuals, who may experience a drop in ventilation of up to 40% during sleep without significant oxygen desaturation9. However, in patients with COPD, hypoventilation during sleep can become more pronounced, leading to more severe hypoxia10.

Impaired sleep quality in patients with COPD is a key contributor to chronic fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and the overall decline in functional capacity and quality of life11,12. Sleep-breathing abnormalities are particularly critical in patients with COPD with coexisting Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSAS), a condition known as overlap syndrome13. These patients experience more pronounced nocturnal hypoxemia, a higher likelihood of developing pulmonary hypertension and an increased risk of mortality compared to those with isolated COPD14,15.

The hypoxia associated with COPD, particularly during sleep, may further contribute to skeletal muscle dysfunction through the enhancement of chronic systemic inflammation16 and oxidative stress17. This in turn, impairs muscle contractility due to the increased production of reactive oxygen species, which mediate damage to lipids, proteins and DNA, and activate inflammatory cascades18. Hypoxemia can also directly affect muscle function by disrupting the regulation of the AKt/mTOR pathway — responsible for protein synthesis and maintenance of muscle mass — potentially through the overexpression of hypoxia-induced genes, leading to reduced muscle mass and functional impairment19,20.

Although research on sleep in COPD patients has received increasing attention in recent years, the relationship between nocturnal symptoms and theirdaytime consequences on muscle quality and functional capacity remains uncertain.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Federal University of SaoCarlos, Sao Paulo, Brazil (CAAE: 81713317.4.0000.5504). Participants were screened at the pulmonology outpatient clinics of a university hospital inSão Carlos and in previous studies conducted at the Cardiopulmonary Physiotherapy Laboratory (LACAP) of the Federal University of Sao Carlos(UFSCar). All participants were informed about the study objectives, experimental procedures, and potential risks involved, and signed an informedconsent form before the beginning of the study. Only individuals who provided consent were included.

Inclusion criteria

The study included adults aged 50 years or older, of both sexes, with a confirmed clinical and spirometric diagnosis of COPD according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria21. All participants underwent home polysomnography for diagnostic confirmation and OSAS severity staging. Only after the home polysomnography examination were participants allocated to the COPD (AHI < 5/h) or COPD-OSAS (AHI > 5/h) groups. Participants were required to be clinically stable, without respiratory exacerbations, hospitalizations, or acute infections for at least three months. Ultimately, only individuals able to walk unassisted and perform the proposed functional tests, without severe osteoarticular or neurological limitations that could interfere with the performance of the walking and handgrip strength tests, were included.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included the use of home oxygen therapy or non-invasive ventilation and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP); the presence ofdiabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, or potential electrocardiogram abnormalities; and neurological or psychiatricdisorders that could interfere with the execution of the study protocol.

Experimental procedures

Assessments were performed over three days: (1) clinical assessments, body composition, and pulmonary function tests; (2) cardiac function evaluationand home sleep testing; and (3) handgrip strength (HGS) and the six-minute walk test (6MWT).

Measurements

Clinical evaluation

Anamnesis and physical examinations were carried out by the principal investigator to assess participants’ general health status and current medications. Afterward, participants were referred for pulmonary function testing.

Body composition by electrical bioimpedance

Body composition was assessed by measuring height using a stadiometer (Welmy R-110, Santa Bárbara d’Oeste, Sao Paulo, Brazil). The individual was barefoot and stood erect in the center of the equipment, arms extended at the sides, and head raised at a right angle to the neck, looking straight ahead. Body mass, body mass index, skeletal muscle mass (appendicular), as well as fat mass and fat percentage, were obtained using an InBody® 720 bioimpedance scale (Biospace Co. Ltd, Seoul, Korea), following the same positioning and instructions as before, with the subject wearing light clothing and having fasted for at least four hours22.

Pulmonary function test

The pulmonary function test was assessed using spirometry (CPFS/D® Medgraphic, MGC Diagnostics Corporation, St. Paul, MN, USA) conducted by a trained researcher, according to the technical standards and the acceptability and reproducibility criteria outlined by the American Thoracic and European Respiratory Societies (ATS/ERS)21. COPD severity was classified as mild (GOLD I), moderate (GOLD II), severe (GOLD III), or very severe (GOLD IV) based on the FEV121.

Cardiac function test

The cardiac function was assessed using echocardiography to rule out heart failure, conducted by a specialist physician following the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines23. The Philips HD11 model (Bothell Everett Highway; Bothell, WA, USA) was used for the echocardiogram. Patients with left ventricular ejection fraction < 50% were excluded23.

Home sleep test

The home sleep test was performed over a single night using the ApneaLink® Air™ device (ResMed Corporation, Germany Inc. Fraunhoferstr), after participants received personalized training on its correct installation and use. The device was delivered on the day of the test, accompanied by verbal and written instructions, and a practical demonstration to ensure proper placement of the sensors before bed. The equipment was positioned by the patient in the home environment, as instructed, and included a nasal airflow sensor, a pulse oximeter for continuous monitoring of peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and a thoracic respiratory effort sensor.

After overnight data collection, the recordings stored on the device were exported to a computer and visually analyzed by an experienced evaluator using the device’s dedicated software. Recording interpretation followed current American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines24, ensuring standardized criteria for detecting and classifying respiratory and desaturation events. The following parameters were recorded: apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), oxygen desaturation index (ODI), mean SpO₂, and the percentage of total recording time with SpO₂ <90%. For the examination to be considered valid, a minimum recording time of four hours of interpretable data was required. Apnea-hypopnea events were defined as a reduction of at least 30% in airflow lasting at least 10 s, associated with desaturation ≥ 4% and/or microarousals. The severity of OSAS was classified based on hourly AHI values: mild (AHI: 5–15 events/h), moderate (AHI: 16–30 events/h), and severe (AHI: >30 events/h), according to the AASM recommendations. Finally, participants were allocated into two groups for analysis: isolated COPD (AHI < 5 events/h) and COPD-OSAS (AHI ≥ 5 events/h), based on the results obtained24.

Handgrip strength

Handgrip strength (HGS)) was assessed using a hydraulic dynamometer (Jamar Jackson®, MI 49203, USA). Patients were seated, with their elbows flexed at 90º, forearm and wrist in neutral position, in accordance with the American Society of Hand Therapists recommendations25. Three voluntary contractions, separated by 60 s of rest, were performed with the dominant hand. Sarcopenia was defined based on criteria from Cruz-Jentoft et al., 201926. Muscle quality was determined by the ratio of appendicular muscle mass to isometric muscle strength 27.

Muscle quality

Muscle quality was obtained from the ratio of isometric muscle strength to appendicular skeletal muscle mass, reflecting the muscle’s ability to generate force per unit mass. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass was measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis, which allows for an accurate assessment of body composition and regional distribution of lean mass, and isometric muscle strength was assessed using handgrip strength testing, a validated method for measuring the maximum strength of specific muscle groups in static contraction without joint movement. The ratio between these two measurements provides an index of muscle quality, capable of identifying functional alterations not evident by muscle mass alone, such as adipose infiltration, changes in muscle architecture or metabolism, and is a relevant marker for detecting sarcopenia, muscle dysfunction, and functional risk28,29.

Six-minute walk test

The 6MWT was conducted on a 30-meter flat corridor, with standardized verbal encouragement provided throughout. Participants were instructed to walk the longest possible distance within six minutes. The test was performed twice, with a 30-minute rest between trials. The best performance, measured as the longest distance walked, was used for analysis30. Heart rate (HR), SpO2, systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and subjective exertion were monitored throughout the test.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA - version 20.0) and SigmaPlot (SyStat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA - version 11.0). After confirming data normality and homogeneity, group comparisons were conducted using the independent samples Student’s t-test or the chi-square test. Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses were used to examine associations between ODI, AHI, muscle quality, and functional outcomes (HGS and 6MWT distance). To identify independent predictors of muscle quality, a multiple linear regression model was constructed with muscle quality as the dependent variable and age, sex, AHI, and ODI as independent variables. These predictors were defined a priori based on physiological plausibility, and AHI and ODI were included simultaneously because they represent complementary dimensions of sleep-disordered breathing—respiratory event frequency and hypoxic burden, respectively. Regression coefficients were interpreted as adjusted estimates of the contribution of each predictor to muscle quality. Model adequacy was confirmed through residual analysis, including inspection of linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and independence. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was adopted for all analyses.

Results

A total of 187 individuals were identified from the patient registry. Following telephone screening, 143 patients were excluded, and 44 were invited to participate in the study and were subsequently allocated to one of the two experimental groups. The specific reasons for exclusions are specified in Fig. 1.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of our sample, which consisted primarily of patients with moderate-severity COPD, with no significant differences in the distribution of severity levels between the study groups. Notably, the group with overlapping OSAS had a significantly higher proportion of male participants. When stratified by the presence of OSAS, patients with COPD-OSAS had higher AHI and ODI values (p < 0.0001) and a higher percentage of sleep time with saturation below 90% (p = 0.02).

Table 2 presents the functional performance by the HGS and the walked in the distance 6MWT along with the hemodynamic behavior during this test. Significantly lower functional performance was observed in the COPD-OSA group, evidenced by reduced handgrip strength (p = 0.03), as well as a higher prevalence of individuals classified as having sarcopenia in this group (p = 0.01), reflecting impaired peripheral muscle function. Additionally, the walked distance during the 6MWT was significantly shorter among participants with concomitant COPD-OSAS (p = 0.04), corroborating the functional limitation of this phenotype. On the other hand, the hemodynamic variables assessed at rest, at peak exertion, and in the recovery phase, did not show statistically significant differences between the groups.

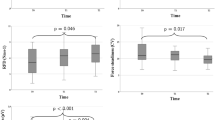

Figure 2 shows significant correlations obtained between the AHI and ODI with functional performance (6MWT and HGS): (A) a moderate negative correlation between the 6MWT and AHI (r=−0.41; p = 0.006); (B) a moderate negative correlation between 6MWT and ODI (r=−0.41; p = 0.006); (C) a weak negative correlation between HGS and AHI (r=−0.29; p = 0.06); (D) a weak negative correlation between HGS and ODI (r=−0.30; p = 0.05); (E) a moderate negative correlation between AHI and muscle quality (r=−0.63; p = < 0.0001); (F) a moderate negative correlation between ODI and muscle quality (r=−0.68; p = < 0.0001).

Correlation analysis between AHI and ODI indexes, functional capacity (6MWT and HGS) and muscle quality. (A) Spearman correlation between 6MWT and AHI; (B) Spearman correlation between 6MWT and ODI; (C) Spearman correlation between HGS and AHI; (D) Spearman correlation between HGS and ODI. (E) Spearman correlation between AHI and muscle quality; (F) Spearman correlation between ODI and muscle quality.

Figure 3 presents the muscle quality for the COPD and COPD-OSAS groups, showing worse muscle quality for the group with overlapping diseases.

In the final multivariable model (Table 3), the ODI remained an independent negative predictor of muscle quality (β= − 0.025; p = 0.003). Sex was also significantly associated with muscle quality (β= −0.20; p = 0.02), indicating lower muscle quality among women compared with men, who served as the reference category. Interestingly, the coefficient for AHI was positive (β = 0.008; p = 0.03), despite its negative bivariate correlation with muscle quality. This change in direction suggests the presence of a statistical suppression effect arising from collinearity between AHI and ODI, as both indices reflect overlapping aspects of sleep-disordered breathing severity. Age did not show a significant association in the adjusted model (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The main findings of this study demonstrate that patients with COPD-OSAS have a worse clinical and functional profile than those with COPD alone. The overlap group showed greater functional impairment, reflected by poorer performance on the walk test and lower handgrip strength, as well as greater impairment of muscle quality. These outcomes were also inversely associated with intermittent hypoxemia indices, supporting the interpretation that more pronounced nocturnal desaturation is linked to poorer muscle and functional parameters, suggesting that OSAS severity contributes to muscle dysfunction and functional limitation. In multivariable analysis, hypoxemia indices, particularly ODI, and sex emerged as independent predictors of muscle quality, reinforcing the role of OSAS as an additional determinant of muscle and functional impairment in patients with COPD.

Although both the 6MWT and HGS are used to assess aspects related to functional capacity, they measure distinct domains of muscular and physical function. The 6MWT is considered a dynamic and direct test of global functional capacity, as it involves the integration of the cardiorespiratory, muscular, and metabolic systems, predominantly recruiting slow-twitch muscle fibers (type I) and utilizing the oxidative bioenergetic system31. On the other hand, the HGS assesses the isometric strength of the upper limb muscles, engaging a smaller muscles group and relying on the glycolytic energy system, which predominantly activates fast-twitch muscle fibers (type II)32. Thus, the combined use of these two measures provides complementary insights into different functional and muscular domains, since muscular strength is a key component of functional capacity and is associated with relevant clinical outcomes in populations with chronic diseases, such as COPD33,34. Therefore, the combined use of these measures enables a more comprehensive understanding of the functional limitations faced by patients.

Our findings demonstrated that patients with COPD-OSAS overlap had poorer functional performance, with a shorter walked distance in the 6MWT (300 m) and lower HGS (p = 26 kgf). Previous studies suggest that walking distances below 350 meters35,36 and HGS values below 20kgf for women and 30 for men are associated with more severe disease, increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations and mortality37. The reduced functional capacity in this population appears to stem from distinct but synergistic mechanisms. In COPD, airflow obstruction and alveolar destruction compromise gas exchange, promoting chronic hypoxemia and increased work of breathing, resulting in early fatigue and limited physical activity11,38,39. In patients with OSAS, these challenges area exacerbated, as recurrent nocturnal micro-awakenings impair sleep quality, leading to increased daytime drowsiness and fatigue13,40. This fatigue, compounded by reduced oxygenation due to airflow limitation, contributes to muscle weakness and diminished physical capacity. Furthermore, systemic inflammation associated with chronic hypoxemia can exacerbate muscle weakness and contribute to sarcopenia41,42. These combined mechanisms help explain the poorer functional performance observed in individuals with COPD-OSAS compared to those with COPD alone.

Studies by Zangrando et al.43, and Carvalho-Jr et al.44, have also examined exercise capacity in patients with overlapping OSAS and COPD, reporting worse functional and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with comorbid conditions. However, it is worth noting that both studies included patients with mild OSAS in the COPD group (AHI = 5.8), which differs from our sample, where we carefully stratified participants based on AHI values and our COPD group presented AHI = 3.4. Additionally, in Zangrando et al.43 study, the COPD group showed worse lung function than the COPD-OSAS group (FEV1 42,7 vs. 61,3, respectively), contrasting with our findings, where COPD severity did not differ between groups. This distinction reinforces that, in the present study, the worse outcomes observed in the overlap group are less likely attributable to differences in COPD severity and more plausibly associated with the presence of OSAS.

Moreover, we observed that apnea-hypopnea and oxygen desaturation indices during sleep were inversely correlated with functional performance and muscle quality. Intermittent reductions in oxygen availability may compromise oxidative phosphorylation, an essential process for ATP production and muscle contraction45,46. This reduction in energy synthesis leads to muscle fatigue and diminished strength, reducing muscle efficiency during physical activity45,46.

In our multivariate analysis, ODI remained the strongest independent predictor of muscle quality, reinforcing the central role of hypoxic load in muscle flexibility in COPD-OSAS patients. Although both ODI and AHI showed negative correlations with muscle quality in univariate analyses, the adjusted model revealed a positive coefficient for AHI. This change in direction is consistent with a suppression effect resulting from shared variance between these indices, which represent overlapping yet physiologically distinct dimensions of sleep-disordered breathing. As ODI accounts for most of the variance associated with intermittent hypoxemia, a process linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation47,48, AHI reflects only a residual component not directly associated with muscle impairment.Its statistical pattern underscores that nocturnal desaturation, rather than respiratory event frequency alone, is more strongly associated with muscle alterations in this population. These findings align with prior work showing that ODI is a more sensitive marker of systemic consequences of OSAS49, highlighting the importance of prioritizing hypoxic burden in clinical monitoring.

Hypoxemia is also linked to a systemic inflammatory response, characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines play a critical role in modulating inflammation, and at elevated levels, they exacerbate inflammation within the musculoskeletal system. This inflammatory cascade impairs protein synthesis, making it difficult for the body to regenerate or maintain muscle mass50,51, thus contributing to muscle weakness and sarcopenia.

It is essential to emphasize the qualitative differences in hypoxemia between the two study groups. In COPD, hypoxemia is typically chronic and sustained during sleep, resulting from persistent ventilation-perfusion mismatch and alveolar destruction52. Conversely, in OSAS, hypoxemia is intermittent, characterized by recurrent cycles of desaturation and reoxygenation due to repeated upper airway obstruction53. Although mean nocturnal oxygen saturation was similar across groups, more sensitive parameters such as the ODI and the percentage of total sleep time with SpO2 below 90% differed significantly, highlighting the greater physiological stress imposed by intermittent hypoxemia in OSAS. This pattern is associated with increased oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired muscle adaptation54 and may help explain the poorer functional outcomes in the overlap group.

The central contribution of this study is the identification of ODI as a clinically relevant predictor of muscle quality in COPD-OSAS, based on a model constructed with variables that are easily obtained in routine practice. However, this does not constitute a predictive tool, and further validation is required before clinical implementation. Monitoring ODI in COPD patients may provide additional insights into the severity of nocturnal hypoxemia and its potential impact on functional and muscular parameters.

Assessment of functional capacity and muscle quality should be an essential part of managing patients with COPD and OSAS. The intermittent hypoxemia characteristic of OSAS, with its recurrent cycles of desaturation and reoxygenation, exerts unique and deleterious effects on muscle function and adaptation, further compromising physical performance in this population. Early identification of functional deficits enables targeted interventions, such as pulmonary rehabilitation programs, which have proven effective in improving functional capacity and quality of life by directly addressing the physiological mechanisms, including those triggered by intermittent hypoxemia that contribute to muscle weakness and decreased endurance. Therefore, integrating this assessment into treatment plans not only enhances clinical outcomes but also provides a more holistic and personalized approach to patient care.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, the sample size was limited. Second, the impact of different OSAS severities on functional capacity and muscle quality was not specifically analyzed. Third, home polysomnography was performed over a single night, which may not capture night-to-night variability in respiratory events and oxygenation. Fourth, inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers were not assessed, limiting mechanistic interpretation. Fifth, residual confounding due to unmeasured variables, such as, for example, comorbidities cannot be completely excluded. Future studies with larger samples, stratification of OSAS severity and multi-night recordings are needed to expand these findings.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that nocturnal hypoxemia is associated with reduced functional capacity and lower muscle quality in patients with COPD and OSAS. In particular, greater hypoxemic burden was linked to poorer six-minute walk test performance and lower muscle strength, reflecting important functional limitations experienced by this population. These findings underscore the clinical relevance of monitoring nocturnal oxygenation but should not be interpreted as evidence of causality, given the cross-sectional design. They also suggest that incorporating assessments of hypoxic burden into clinical follow-up may help identify individuals at higher risk of functional decline, informing early referral to established interventions such as pulmonary rehabilitation. Nevertheless, these implications should be interpreted cautiously, and additional research is required to clarify underlying mechanisms, validate these associations in larger cohorts, and determine whether targeted therapeutic strategies can mitigate the functional consequences of nocturnal hypoxemia in COPD-OSAS.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vestbo, J. COPD: definition and phenotypes. Clin. Chest Med. 35 (1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.010 (2014).

Cruz, M. M. & Pereira, M. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cien Saude Colet. 25 (11), 4547–4557. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320202511.00222019 (2020).

Couillard, A. From muscle disuse to myopathy in COPD: potential contribution of oxidative stress. Eur. Respir. J. 26 (4), 703–719. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00139904 (2005).

Gosker, H. R., Zeegers, M. P., Wouters, E. F. M. & Schols, A. M. W. J. Muscle fibre type shifting in the Vastus lateralis of patients with COPD is associated with disease severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 62 (11), 944–949. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2007.078980 (2007).

Picard, M. et al. The mitochondrial phenotype of peripheral muscle in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 178 (10), 1040–1047. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200807-1005OC (2008).

Adami, A., Cao, R., Porszasz, J., Casaburi, R. & Rossiter, H. B. Reproducibility of NIRS assessment of muscle oxidative capacity in smokers with and without COPD. Respir Physiol. Neurobiol. 235, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2016.09.008 (2017).

Maltais, F. et al. An official American thoracic society/European respiratory society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 189 (9), e15–62. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201402-0373ST (2014).

Vanfleteren, L. E. et al. Multimorbidity in COPD, does sleep matter? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 73 (December 2019), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.12.032 (2020).

Phillipson, E. A. Control of breathing during sleep (state of the art). Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 118 (5), 909–937. https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1978.118.5.909 (1978).

Douglas, N. J. et al. Lancet ;313(8106):1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(79)90451-3 (1979).

Breslin, E. et al. Perception of fatigue and quality of life in patients with COPD. Chest 114 (4), 958–964. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.114.4.958 (1998).

Budhiraja, R., Siddiqi, T. A. & Quan, S. F. Sleep disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Etiology, Impact, and management. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 11 (03), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4540 (2015).

McNicholas, W. T., Hansson, D., Schiza, S. & Grote, L. Sleep in chronic respiratory disease: COPD and hypoventilation disorders. Eur. Respiratory Rev. 28 (153), 190064. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0064-2019 (2019).

Marin, J. M., Soriano, J. B., Carrizo, S. J., Boldova, A. & Celli, B. R. Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 182 (3), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200912-1869OC (2010).

Camargo, P. F. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea reduces functional capacity and impairs cardiac autonomic modulation during submaximal exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A follow-up study. Heart Lung. 57, 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.10.007 (2023).

Kim, H. C., Lee, G. D. & Hwang, Y. S. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Tuberc Respir Dis. (Seoul). 68 (3), 125. https://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2010.68.3.125 (2010).

Lage, V. K., da Paula, S. & dos Santos, F. A. Are oxidative stress biomarkers and respiratory muscles strength associated with COPD-related sarcopenia in older adults? Exp. Gerontol. 157, 111630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111630 (2022).

Couillard, A. et al. Exercise-induced quadriceps oxidative stress and peripheral muscle dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 167 (12), 1664–1669. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200209-1028OC (2003).

Bodine, S. C. et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3 (11), 1014–1019. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1101-1014 (2001).

Jatta, K. et al. Overexpression of von Hippel-Lindau protein in skeletal muscles of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 62 (1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2008.057190 (2009).

Miller, M. R. et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 26 (2), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 (2005).

Kyle, U. G. et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin. Nutr. 23 (6), 1430–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2004.09.012 (2004).

Lang, R. M. et al. EAE/ASE recommendations for image acquisition and display using three-dimensional echocardiography. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 13 (1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jer316 (2012).

Kapur, V. K. et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 13 (03), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6506 (2017).

Donnell, M. The American society of hand therapists. J. Hand Ther. 8 (4), 237–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0894-1130(12)80113-X (1995).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 39 (4), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq034 (2010).

Pion, C. H. et al. Muscle strength and force development in high- and low-functioning elderly men: influence of muscular and neural factors. Exp. Gerontol. 96, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.05.021 (2017).

Newman, A. B. et al. Sarcopenia: alternative definitions and associations with lower extremity function. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51 (11), 1602–1609. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51534.x (2003).

Wen, Z. et al. Handgrip strength and muscle quality: results from the National health and nutrition examination survey database. J. Clin. Med. 12 (9), 3184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093184 (2023).

Issues, S., Test, M. W., Equipment, R. & Preparation, P. ATS statement. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 166 (1), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 (2002).

Solway, S., Brooks, D., Lacasse, Y. & Thomas, S. A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 119 (1), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.119.1.256 (2001).

Waldo, B. R. Grip strength testing. Strength. Cond J. 18 (5), 32. https://doi.org/10.1519/1073-6840(1996)018%3C0032 (1996). :GST>2.3.CO;2

Kyomoto, Y. et al. Handgrip strength measurement in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: possible predictor of exercise capacity. Respir Investig. 57 (5), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resinv.2019.03.014 (2019).

Holden, M. et al. Handgrip strength in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 101 (6). https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab057 (2021).

Zanoria, S. J. T. & ZuWallack, R. Directly measured physical activity as a predictor of hospitalizations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron. Respir Dis. 10 (4), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972313505880 (2013).

Andrianopoulos, V. et al. Prognostic value of variables derived from the six-minute walk test in patients with COPD: results from the ECLIPSE study. Respir Med. 109 (9), 1138–1146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2015.06.013 (2015).

Lee, C. T. & Wang, P. H. Handgrip strength during admission for COPD exacerbation: impact on further exacerbation risk. BMC Pulm Med. 21 (1), 245. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01610-7 (2021).

Casaburi, R. Skeletal muscle function in COPD. Chest 117 (5), 267S–271S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.267S-a (2000).

Miranda, E. F., Malaguti, C., Marchetti, P. H. & Dal Corso, S. Upper and lower limb muscles in patients with COPD: similarities in muscle efficiency but differences in fatigue resistance. Respir Care. 59 (1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.02439 (2014).

Mjelle, K. E. S., Lehmann, S., Saxvig, I. W., Gulati, S. & Bjorvatn, B. Association of excessive sleepiness, pathological Fatigue, Depression, and anxiety with different severity levels of obstructive sleep apnea. Front. Psychol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.839408 (2022).

Locke, B. W., Lee, J. J. & Sundar, K. M. OSA and chronic respiratory disease: mechanisms and epidemiology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (9), 5473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095473 (2022).

Di Girolamo, F. G. et al. Skeletal muscle in hypoxia and inflammation: insights on the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Nutr. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.865402 (2022).

Zangrando, K. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and its association with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: impact on cardiac autonomic modulation and functional capacity. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 13, 1343–1351. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S156168 (2018).

de Carvalho Junior, L. C. S. et al. Overlap syndrome: the coexistence of OSA further impairs cardiorespiratory fitness in COPD. Sleep. Breath. 24 (4), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-02002-2 (2020).

Dewan, N. A., Nieto, F. J. & Somers, V. K. Intermittent hypoxemia and OSA. Chest 147 (1), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0500 (2015).

Pau, M. C. et al. Evaluation of inflammation and oxidative stress markers in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). J. Clin. Med. 12 (12), 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12123935 (2023).

Mathur, S., Brooks, D. & Carvalho, C. R. F. Structural alterations of skeletal muscle in Copd. Front. Physiol. 5 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2014.00104 (2014).

Liao, Y. X. et al. Associations of fat, bone, and muscle indices with disease severity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Sleep. Breath. 29 (1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-024-03241-8 (2025).

Labarca, G., Gower, J., Lamperti, L., Dreyse, J. & Jorquera, J. Chronic intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea: a narrative review from pathophysiological pathways to a precision clinical approach. Sleep. Breath. 24 (2), 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01967-4 (2020).

He, Q. et al. Effects of varying degrees of intermittent hypoxia on Proinflammatory cytokines and adipokines in rats and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. PLoS One. 9 (1), e86326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086326 (2014).

Ichiwata, T. et al. Oxidative capacity of the skeletal muscle and lactic acid kinetics during exercise in healthy subjects and patients with COPD. In: 537–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1241-1_78 (2010).

Nathan, S. D. et al. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung disease and hypoxia. Eur. Respir. J. 53 (1), 1801914. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01914-2018 (2019).

Ryan, S. Adipose tissue inflammation by intermittent hypoxia: mechanistic link between obstructive sleep Apnoea and metabolic dysfunction. J. Physiol. 595 (8), 2423–2430. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP273312 (2017).

Lavie, L. Oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea and intermittent hypoxia – Revisited – The bad ugly and good: implications to the heart and brain. Sleep. Med. Rev. 20, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.003 (2015).

Funding

This study was supported bygrants from the Federal University of São Carlos/FAPESP (process numbers 2015/26501-1 and 2018/00860-3) and from the Coordenação deAperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES, Finance Code 001). Audrey Borghi-Silva is an established investigator (Level IB) fundedby the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil. The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PFC and AB-S conceived the study. PFC, Carvalho-Junior LCS, LRL, and LAF contributed to data collection. PFC, GDB, and AB-Sperformed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. PFC, CLG, and AB-S performed the final revisions. All authors read and approved the finalversion of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financialinterest (such as honoraria, educational grants, participation in speakers’ bureaus, membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership or other equityinterests, and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements) or any non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations,knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Camargo, P.F., Back, G.D., de Carvalho-Junior, L.C.S. et al. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on functional performance and muscle quality of patients with COPD. Sci Rep 16, 2277 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32126-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32126-3