Abstract

Rising global temperatures and heatwaves pose escalating health risks. This study aims to explore heatstroke (HS) awareness and prevention among 1142 residents of Fukuoka City, Japan, in 2020 and 2022. Questionnaire data revealed that while many respondents reported past experiences of HS-like symptoms (78.8%) and possessed high knowledge of HS symptoms (90.1%), only 56.3% adopted extensive (≥ 4) preventive measures. Crucially, a robust understanding of HS symptoms—rather than personal experience with mild symptoms—was the strongest predictor of adopting daily preventive practices (odds ratio [OR] 2.556, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.715, 3.809], p < 0.001). The findings also highlight distinct challenges across demographics: older adults were more proactive in taking preventive measures, yet ensuring this translates to timely recognition of specific symptoms remains a key challenge. Conversely, younger individuals showed a significant behavioural gap, lagging in prevention despite frequent symptom experience. Notably, the adoption of preventive measures increased significantly in 2022 compared to 2020 (OR 2.808, p < 0.001), a change that coincided with the implementation of new national public health initiatives. These results underscore the need for tailored interventions, focusing on symptom recognition for older males and strategies to close the knowledge-behaviour gap among the young.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the escalating health risks associated with rising global temperatures and more frequent heatwaves have drawn significant attention worldwide1, especially among the climate change analysts. Mora et al.2 projected that 74% of the global population is expected to face deadly heat conditions for at least 20 days per year by 2100, a significant increase from the current 30%. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change3 underscores the growing heat-related risks, marking it as a pressing global public health challenge. Analysing future climate and socioeconomic change, Chen et al.4 also show that more people worldwide are projected to be increasingly subjected to extreme heat events.

Heatstroke (HS) is a severe life-threatening condition resulting from the body’s inability to regulate heat stress5. Although HS is an acute medical emergency6, the broader health impacts of excessive heat also include the worsening of chronic conditions7, such as cardiovascular8 and respiratory diseases9, which contribute significantly to heat-related morbidity and mortality. Moreover, as Kjellstrom et al.10 reported, heat stress can impair human performance, work capacity, and productivity, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. Vulnerable populations—including the elderly, children, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions—are disproportionately affected by excessive heat11. Other at-risk groups include outdoor workers12,13,14 and individuals of lower socioeconomic status7.

While some studies have documented a long-term decline in heat-related vulnerability over the past decades in certain developed regions—likely due to improved prevention strategies such as heat warning systems, increased air-conditioning use, and heightened public awareness15—effectiveness of specific interventions, particularly for vulnerable groups under diverse social and environmental contexts, remains inadequately understood16.

Given the anticipated rise in frequency, intensity, and duration of heatwaves, it is critical to develop and implement effective heat action plans and public health strategies17. Previous research18,19,20,21,22 emphasised the importance of population-level interventions such as public education campaigns and engagement of healthcare professionals. The most recent guidelines of WHO Regional Office for Europe23 recommend a multi-faceted approach that includes early warning systems, improved building thermal performance, access to cooling devices, behavioural adaptations, public awareness campaigns, and urban planning improvements. In addition to population-wide interventions, targeted outreach to vulnerable individuals—such as home visits and health surveillance of frail elderly people—is crucial, though these programmes are often challenging to implement and under-resourced.

Public awareness is a critical component of effective prevention, yet studies reveal a complex global picture. For instance, investigation in the United Arab Emirates24, Indonesia25, and rural India26 identified significant gaps in public knowledge and preventive behaviours. In contrast, according to the studies targeting Europe23 and North America27, awareness of heat risks is relatively high. However, translating this into consistent protective actions remains a challenge, particularly among vulnerable groups who may underestimate their personal risk16,23. These studies suggest that factors such as age, gender, and information sources heavily influence preventive practices.

This global challenge is particularly pertinent in Japan, which faces a unique combination of a super-aged society and rising heatwave frequency. The nation has witnessed an uptick in midsummer days and tropical nights, signalling increased health risks due to higher temperatures28,29. Domestic studies have examined HS from various perspectives, including influences of demographic and environmental characteristics on ambulance dispatches14,30 and the development of a HS alert31. Despite a high penetration rate of household air conditioners (92.2%)32, a staggering 76% of indoor HS deaths in Tokyo in 2021 occurred in homes where AC units were available but not used33. This “behavioural gap” underscores the fact that technological availability does not guarantee protection. While the Japanese government has launched a national action plan in May 2023 to halve HS-related deaths by 203034, persistent high rates of mortality and emergency transports14,35 signal an urgent need to understand the specific drivers and barriers to preventive action at the community level. In fact, over 1,000 fatalities are recorded annually (five-year moving average), and more than 91,000 emergency transports were reported between May and September of 2023 alone35.

Therefore, this study aims to bridge this critical gap. Using questionnaire data from municipal surveys in Fukuoka City (2020 and 2022), we evaluate residents’ awareness and preventive behaviours across various demographic groups. Thus, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

What are the prevalence of heatstroke symptom experience, the level of knowledge about symptoms, and the status of preventive practices among Fukuoka City residents?

-

Is the level of knowledge regarding heatstroke symptoms significantly associated with the adoption of preventive behaviours?

This study also intended to identify key factors influencing these actions, gauge engagement with prevention practices, and contribute evidence-based recommendations for enhancing community resilience through tailored public health strategies. The findings are expected to contribute to evidence-based recommendations for enhancing community resilience to heat stress through tailored educational initiatives and improved municipal support systems.

Data and methodology

Ethical statement

This study was conducted using existing, anonymized data. As such, it was determined to be exempt from formal ethical review by the Kyushu University’s Standard Operating Procedures for the Ethics Review Board (Observational and Interventional Studies). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of Kyushu University and the ethical standards for research involving human participants. Individual informed consent was waived by Kyushu University’s Standard Operating Procedures for the Ethics Review Board.

Outline of questionnaire surveys

This study utilises a dataset from questionnaire surveys conducted by the local government of Fukuoka City, a major city in the Kyushu region of southern Japan with a population of 1.65 million.

Since 2007, Fukuoka City has been conducting these surveys four to six times annually to gauge citizens’ needs and perceptions of various municipal policies, and to enhance citizens’ understanding of the municipal administration. The pool of survey monitors is newly constituted each year. Invitations are sent to a new randomly selected group of citizens aged 18 and over from the basic resident register. From among them, approximately 600 citizens agree to participate and serve as registered monitors. This annual sampling process ensures that the respondent pools for the 2020 and 2022 surveys are independent, with negligible overlap between them. As an incentive, respondents receive a prepaid card worth 500 yen at the end of the year for each survey they complete. Surveys are distributed either by paper mail or email, based on the respondents’ prior preferences. Those receiving paper questionnaires also have the option to respond online via a designated URL.

The questionnaires cover a variety of topics that may vary depending on social conditions and other factors. This paper utilises data from the surveys conducted between 25 June and 9 July, 2020, and 25 May and 8 June, 2022, as these focused on HS countermeasures in Fukuoka City.

Weather conditions during these survey periods differed notably. In June 2020 survey period experienced significantly hotter conditions, with average daily maximum temperatures of 30.2 °C, well above the normal of 27.0 °C. In contrast, during the May 2022 survey period, temperatures were closer to normal or slightly above, with an average daily maximum of 24.8 °C compared to a normal of 24.4 °C, indicating less severe heat than in 2020. “Normal” temperatures are defined as the 30-year average (1991–2020) for the responding month.

In the 2020 and 2022 surveys, questionnaires were sent to 622 and 681 registered monitors, respectively, resulting in 549 and 609 responses. This brings the total sample size to 1,158, with a response rate of 88.9%. Around half of the respondents (46.63%) were male, while 53.4% were female. The surveys included eight questions focusing on various aspects of HS, such as knowledge about the symptoms of HS, actions taken when individuals felt HS symptoms in the past, daily preventive measures against HS, sources of information on HS prevention, and requests to Fukuoka City regarding HS prevention measures. After discarding all missing and inconsistent observations, 1142 complete observations on target variables were finally analysed in this study. The variables and values originally collected from the questionnaires and those used for the statistical analysis are summarised in Table 1.

Methodology

The key outcome variables, “Knowledge on HS symptoms” and “HS preventive measures,” were operationalized through categorization to facilitate meaningful group comparisons and ensure robust analysis. This categorization process was informed by both the distribution of responses from the survey data and the analytical need to create distinct, interpretable groups.

Specifically, for the “Knowledge on HS symptoms” variable, which was derived from a question assessing familiarity with 12 listed HS symptoms, a binary categorization was applied. As detailed in Table 1, respondents who knew 0–4 symptoms were classified into the “Less to no information” category, while those who knew 5 or more symptoms were grouped into the “Moderate to well-known” category. This dichotomization was chosen to clearly distinguish participants with limited awareness from those with a greater understanding of HS symptoms, allowing for a distinct contrast in health knowledge.

Regarding the “HS preventive measures” variable, which was based on the number of preventive actions adopted by respondents from a pre-defined list (see Table 1), a three-level ordinal classification was employed: “Less prevention” (0–1 measures adopted), “Moderate prevention” (2–3 measures adopted), and “High prevention” (4 or more measures adopted). This ordinal structure was designed to capture increasing levels of engagement in HS prevention and to support interpretable comparisons within the ordinal logistic regression models.

The analysis began with checking the percentage distribution of the selected variables, followed by depicting how the corresponding outcomes are distributed within the categories of the covariates. The chi-square test36 of independence evaluated the statistical significance of the one-to-one association between the outcome variables and covariates of interest. Various logistic regression models were used to analyse each outcome variable. Binary logistic regression model37 analysed the first two outcome variables (past experience of HS symptoms and knowledge on HS symptoms) while HS preventive measures, an ordinal variable with more than two categories was scrutinized through ordinal logistic regression model38,39,40. The variables found to have significant associations in the previous part were included in the respective regression models.

Let \(\:Y\) be the categorical variable with \(\:J\:(>\)2\(\:)\) categories, which can be ordered, and \(\:{Y}_{i}\) be the response on this variable obtained from the \(\:{i}^{th}\:\left(i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,\:n\right)\:\)individual. Suppose that \(\:{x}_{i}=({x}_{i1},{x}_{i2},\cdots\:,{x}_{ik},\cdots\:,{x}_{iK})^{\prime\:}\) is the \(\:(K\times\:1)\) vector of covariates for the corresponding individual and \(\:\beta\:=({\beta\:}_{1},{\beta\:}_{2},\cdots\:,{\beta\:}_{k},\cdots\:,{\beta\:}_{K})^{\prime\:}\) is the \(\:(K\times\:1)\) vector of regression coefficients. The equation below represents the ordinal logistic regression model, which can be written as follows.

In the above equation, \(\:{\alpha\:}_{j}\) is the threshold term for the \(\:{j}^{th}\) category. The left part of the equation is odds for the \(\:{j}^{th}\:(j=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,J-1)\) category of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) individual. Hence, the odds ratio (OR) of the covariate \(\:{x}_{k}\) is \(\:\text{exp}\left({\beta\:}_{k}\right).\) On the other hand, for a binary outcome variable, which can take only two possible values (0 and 1), the binary logistic regression model is used and expressed as follows.

The maximum likelihood estimation approach is applied in this study to estimate the regression coefficients.

In the logistic regression model for another target variable—the past experience of HS symptoms—a specific strategy for covariate inclusion was employed. This variable is binary, indicating whether any HS-like symptom was experienced or not). The covariates of interest were incorporated sequentially to illustrate their relationship with the outcome before and after accounting for confounding effects. Initially, variables regarding people’s awareness, such as the knowledge of HS symptoms, HS preventive measures, and checking weather updates, were included in the first model (Model I). This was followed by the inclusion of socio-economic condition-related variables: occupation and type of residence (Model II). Finally, demographic variables like an age-sex composite variable and a temporal covariate (the year of the survey) were incorporated into the previous two sets of variables to form Model III. The age-sex composite variable —with six categories: young males, young females, middle-aged males, middle-aged females, old males, and old females—was considered to capture variations across both age and gender. Such a categorization allowed for a straightforward yet meaningful comparison of HS experiences combining different age-gender groups, resulting in a simpler interpretation of the findings. The findings of a study conducted in Fukuoka city of Japan14 motivated this approach of age- and sex-related decomposition.

To serve this purpose, STATA version 14.041 was used. For each regression coefficient, statistical significance was assessed using a Wald test42, which evaluates whether the coefficient differs significantly from zero. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data and variables

All variables considered in this study are presented in Table 1. This table presents how survey questions are used to construct and re-categorize the target variables.

Result and discussion

Descriptive statistics

The analysis began with the descriptive statistics of all the variables considered in this study. First, the percentage distribution of the selected variables is presented in Table 2. This table also displays the percentages of the responses within the categories of the respective covariates, along with the p-values of the chi-square test of independence36.

Among the 1,142 target respondents, 78.8% had experienced HS or similar health issues in the past. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for this estimate was [76.32%, 81.15%]. This indicates HS-related discomfort as a highly relevant public health concern. It should be noted that this high percentage suggests that many of these self-reported experiences likely encompass mild symptoms such as dizziness or temporary fatigue, rather than solely severe episodes. This is supported by the fact that the figure is considerably larger than official statistics for severe HS cases requiring emergency transport. For instance, figures for emergency transports due to HS in Fukuoka City are much lower; Toosty et al.14 reported that for males aged 70 and over, a demographic often considered high-risk, the number of such transports was approximately 6–10 cases per 1,000 population.

In addition, 90.1% (95% CI = [88.22%, 91.78%]) of the respondents possessed moderate to high knowledge on HS symptoms, meaning they knew at least five symptoms of HS. On the other hand, more than half of the respondents (56.5% [53.37%, 59.21%]) adopted at least four preventive measures of HS in their daily life, whereas only 7.2% (95% CI = [5.83%, 8.93%]) followed a less preventive lifestyle, practising at most one precaution.

The p-values of the chi-square test of independence reveal the past experience of HS symptoms to have significant unadjusted associations with HS preventive measures, occupation, and age-sex composite variable. On the other hand, the outcome variable knowledge on HS symptoms was found to be significantly associated (one-to-one) with the HS preventive measures, checking weather updates, and age-sex composite variable. Finally, the significant associates of HS preventive measures, according to the Chi-square test of independence, were past experience of HS, knowledge of HS symptoms, checking weather forecasts, occupation, age-sex composite variable, and year of survey.

Regression analyses

Past experience of heatstroke-like symptoms

The associations of different covariates with the past experience of HS-like symptoms were examined using sequential logistic regression models (Table 3). This sequential approach was adopted because a preliminary analysis, which included all covariates simultaneously, found that the association was significant only for the age-sex composite variable, potentially masking the effects of other variable groups.

In Model I, high adoption of HS preventive measures was significantly associated with a 33.4% (i.e., (1–0.667) × 100%) lower odds of experiencing HS-like symptoms compared to moderate prevention (OR = 0.661, p < 0.05). This finding aligns with expectation that preventive actions reduce symptom experience. However, the significance of preventive measures diminished when socio-economic variables were included in Model II.

Model II revealed significant differences in symptom experience based on occupation. Compared to employed individuals, unemployed individuals had 45.1% lower odds (p < 0.001) of reporting HS-like symptoms, likely due to less exposure to high daytime temperatures while at home. Conversely, students exhibited 172.8% higher odds (p < 0.05), possibly due to participation in outdoor sports during hot weather—a finding consistent with Toosty et al.14

In the comprehensive Model III, which adjusted for all variables including demographic and temporal factors, only the age-sex composite variable remained significantly associated with past HS-like experiences. Notably, middle-aged females, older males, and older females reported experiencing HS-like symptoms significantly less frequently than young males. This may appear counter-intuitive, as older individuals are generally more vulnerable to severe HS requiring emergency care14. However, this study captured any self-reported HS-like symptoms, including milder ones like dizziness or temporary fatigue, rather than severe cases requiring emergency transportation and intensive care.

While employment status was a factor in Model II, its statistical significance did not persist in Model III. This suggests that employment status alone does not fully explain the lower reported symptom experience among middle-aged females and older adults. Other lifestyle factors associated with these age-sex groups likely contribute by reducing overall exposure to high-heat environments. For instance, retirees (common in older age groups) may spend more time indoors, and some middle-aged females (e.g., homemakers) may have daily routines with less outdoor exposure compared to full-time outdoor workers12.

Therefore, the lower reporting of HS-like symptoms by older individuals is likely due to differing lifestyle-related heat exposure and potentially a reduced perception of milder symptoms as HS. Ultimately, this finding suggests that a robust understanding of HS’s potential severity—rather than a personal history of mild discomfort—is the critical driver for adopting daily preventive measures. This highlights the necessity of public health campaigns that effectively communicate the serious dangers of HS, as personal experience with minor symptoms may not be a sufficient catalyst for sustained behavioural change. The ORs along with the 95% confidence intervals obtained from Model III are visualised using the dot-and-whisker plot in (Fig. 1).

Knowledge on heatstroke symptoms

The ‘Knowledge on HS symptoms’ variable assesses respondents’ familiarity with a list of 12 specific symptoms associated with HS. Many of these symptoms—such as dizziness, fatigue, profuse sweating, or muscle cramps—often manifest during the early or mild stages of the condition. Recognising these initial warning signs is critically important because it enables individuals to become aware of their compromised physical state and to take immediate self-help actions, such as moving to a cooler environment, rehydrating, and resting. Such prompt responses can be crucial in preventing the progression of HS to more severe, potentially life-threatening stages. This type of knowledge differs from awareness of daily preventive measures (discussed later); while daily practices aim to avert the onset of HS, specific knowledge of symptoms is vital for effective self-management and rapid mitigation if the initial signs of HS do unfortunately appear.

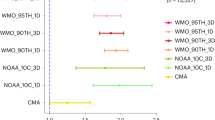

To identify the potential determinants of knowledge about HS symptoms, the selected covariates were included in a binary logistic regression. The results of this model are reported in Table 4. The estimated ORs along with the error bars representing 95% confidence intervals are presented in (Fig. 2).

Table 4 reveals that the respondents practising lower preventive measures had 61.4% lower odds (p < 0.01) of possessing greater knowledge of HS symptoms compared to those adopting moderate prevention against HS. On the contrary, the highly preventive group had significantly 103.8% higher odds of having broader knowledge of HS symptoms than those who practised a moderate level of HS preventive measures. This finding indicates that practising HS preventive measures daily is positively associated with the level of knowledge of HS symptoms. This result is highly plausible since the people who regularly practise preventive measures against HS are likely to have greater knowledge of its symptoms. On the other hand, those who usually check weather forecasts in advance were found to have significantly higher odds of possessing advanced knowledge of the symptoms of HS. Checking weather updates reflects people’s awareness, which is associated with their understanding of HS symptoms.

During the survey year of 2022, people were less likely to possess enhanced knowledge on HS symptoms than those in 2020. This observed difference may be attributed to the differing ambient temperatures during the survey periods. As previously mentioned, the 2020 survey was conducted under hotter weather conditions, with daily maximum temperatures approximately 3 °C higher than the 1991–2020 average for the month. This higher heat exposure likely led to the increased public and media attention on HS, enhancing the immediate salience and retention of HS symptom knowledge among the public. In contrast, the 2022 survey was conducted approximately one month earlier than in 2020, with temperatures closer to the 30-year average for that month. The less intense heat during this earlier period may have resulted in a reduced focus on HS information, contributing to lower reported knowledge levels compared to 2020.

Regarding the age-sex composite variable, neither older males nor older females revealed any significant difference in the odds of having sufficient knowledge about HS symptoms compared to young males. This finding suggests that despite the higher likelihood of experiencing HS-like symptoms, the younger generation does not exhibit a significantly different level of knowledge about HS symptoms compared to their older counterparts.

Preventive measures against heatstroke

The results of ordinal logistic regression models that scrutinized HS preventive measures encompassing all the selected covariates, are presented in Table 5. These results are also illustrated in Fig. 3 presenting the estimated proportional ORs along with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 5 shows that knowledge of HS symptoms is a significant factor (p < 0.001) in adopting HS preventive measures, even after adjusting for other covariates. Those with moderate to high knowledge of HS symptoms had an OR of 2.556 (p < 0.001), indicating they were 2.556 times more likely to adopt greater preventive measures (high or moderate prevention versus less prevention) compared to those with little knowledge of HS symptoms. This finding is expected, as advanced knowledge of HS symptoms motivates individuals to safeguard themselves by adopting greater preventive measures. This strong association between knowledge and practice is consistent with the broader literature. For instance, a scoping review by Hasan et al.21 identified public education as a cornerstone of effective heat action plans. Our results provide strong empirical support for this principle in the Japanese context, demonstrating that enhancing specific knowledge about HS symptoms is a powerful lever for promoting protective behaviours.

Both unemployed individuals and students had respectively 61.1% and 94.1% higher odds, respectively (p < 0.05) compared to the employed individuals. The employed individuals, who are mostly middle-aged, do not belong to the most vulnerable age group. Additionally, the low proportion (13.5%) of outdoor workers among the employed population in Fukuoka city43 may lessen the need for extensive HS prevention measures within this group. This finding highlights that perceived risk—shaped by daily environment and occupation—strongly influences preventive behaviour. Our results for a predominantly non-outdoor workforce contrast with the context of populations with high occupational heat exposure, such as farmers. For example, a study of farmers in Lucknow, India26, found that while the majority had moderate (61.90%) or adequate (35.71%) knowledge of HS, they represent a group for whom heat is a constant and direct occupational hazard. Although that study did not compare farmers with other occupational groups, its focus on an outdoor-working population provides a critical counterpoint. It suggests that public health messaging may need to be tailored differently for office workers, who may underestimate their incidental exposure, versus those like farmers who face continuous exposure. This aligns with observations from other research, such as a study on Indonesian pilgrims, which noted that farmers accustomed to sun exposure might paradoxically underestimate the risks in a new environment25.

Middle-aged males and females along with both the older males and females were more likely to adopt greater prevention measures than young males. In Japan, with its high proportion of senior people, both local and national governments have recently focused on HS prevention campaigns for seniors, as they are less resilient to heat stress. Consequently, older individuals have become more conscious of preventing HS by adopting more extensive preventive measures.

Our finding that older adults are more proactive in prevention contrasts with a study in the UAE24, which reported that older age was associated with poorer knowledge24. This apparent discrepancy can be understood by considering the different demographic contexts. The “older” cohort in the UAE study (≥ 36 years) likely represents a working, middle-aged population, whereas our study’s older groups (≥ 60 years) are predominantly seniors targeted by intensive public health campaigns in Japan. Therefore, our result likely demonstrates the positive impact of these campaigns on a recognised high-risk group.

Interestingly, while our analysis did not find a statistically significant difference in the overall knowledge scores of older adults compared to younger groups, they were significantly more proactive in taking preventive measures. This suggests that public health campaigns have been successful in promoting protective behaviours, likely by increasing the sense of personal risk among this key demographic. Therefore, the remaining challenge may not be a simple lack of overall knowledge, but ensuring this general awareness is refined into the ability to recognise specific, early symptoms to prompt timely action.

Nevertheless, these campaigns must now be refined to deliver more detailed information on symptom recognition to this key demographic. This aligns with Fujimoto et al.44, who noted that older adults may struggle to objectively assess heat levels, and highlighted that interventions for this group must address both the promotion of preventive behaviours and the filling of specific knowledge gaps, such as early symptom recognition. Furthermore, factors like living alone, which Fujimoto et al.44 identified as a primary risk factor, underscore the need for social support systems alongside individual behavioural change.

Interestingly, after adjusting for other covariates, previous experience of HS-like symptoms was not significantly associated with the adoption of higher levels of preventive measures (Table 5). As previously noted in the descriptive statistics (discussion of Table 2), a large proportion of respondents reported such experiences, which are inferred to have largely encompassed mild symptoms. This prevalence of predominantly mild experiences might explain the lack of a significant association with the ongoing, daily preventive measures assessed in this study; individuals may have perceived immediate, temporary actions taken at the time of the mild episode (such as rehydration or rest, as outlined in Table 1 as potential responses) as sufficient, rather than feeling compelled to adopt more comprehensive or numerous routine preventive strategies. This finding, when contrasted with the strong positive association observed between knowledge of HS symptoms and preventive actions, suggests that a robust understanding of HS risks and potential severity may be a stronger driver of daily preventive behaviour than a personal history of predominantly mild heat-related discomfort.

This finding offers a nuanced perspective that contrasts with the general assumption that personal experience directly drives behavioural change. While past studies focus on knowledge or sociodemographic factors, the impact of the severity of past experiences is less explored. Our results suggest that experiencing only mild symptoms may not be a sufficient catalyst for adopting sustained, daily preventive measures. Instead, as our other findings indicate, a robust understanding of the potential severity and risks of HS, likely acquired through educational interventions and public health messaging, appears to be a more critical driver for sustained preventive action. This highlights the necessity of public health campaigns that go beyond simple symptom awareness to effectively communicate the serious dangers of HS.

During the survey year of 2022, people were more likely to adopt greater preventive measures compared to those in the year 2020. As mentioned earlier, in 2021, the Japanese Government established the Council for the Promotion of Heatstroke Countermeasures34 and has since actively promoted protective measures to citizens through media and public relations. Given this background, the current result may suggest a positive trend in people’s behaviours toward better health practices, which aligns with the goals of these national efforts.

The seemingly contrasting findings between 2020 and 2022—specifically, higher knowledge of HS symptoms in 2020, yet a significant increase in the adoption of preventive measures in 2022—suggest a qualitative shift in the public health environment surrounding HS prevention.

As previously discussed, the heightened knowledge observed in 2020 can be largely attributed to the immediate impact of the severe heat experienced during that survey period, which likely increased public awareness and short-term retention of HS-related information. In contrast, the marked improvement in preventive behaviours by 2022 may be associated with more directed and structured interventions. While the establishment of the Council for the Promotion of Heatstroke Countermeasures in 2021 played a role, a more direct contributor may be the nationwide rollout of the “Heatstroke Alert” system in April 2021.

This alert system provides a powerful trigger for immediate action. In fact, in Fukuoka Prefecture, where the study was conducted, the alert was issued 23 times during the summer of the preceding year, 2021. In Fukuoka City, an alert prompts public notifications through disaster prevention emails, the official LINE account, and digital signage, urging citizens to take specific precautions. We hypothesize that this frequent, push-style delivery of actionable risk information shifted public response from knowledge-based to trigger-based habitual behaviour.

This interpretation is strongly supported by Hasan et al.21, who identified “early warning systems” as a key component of highly effective Heat-Health Action Plans. Our results suggest that the “Heatstroke Alert” system functions as precisely such a mechanism, translating risk information into timely, actionable behavioural prompts. Therefore, the temporal changes observed are not merely a reflection of a time lag between knowledge acquisition and behaviour change but can be interpreted as the result of a shift in public communication strategy—from general awareness-raising to specific, real-time calls to action. This highlights the critical importance of timely risk communication in fostering sustained preventive actions.

Hasan et al.21 concluded that multi-faceted Heat-Health Action Plans—incorporating early warning systems, public information, and monitoring of vulnerable individuals—are highly effective in reducing heat-related morbidity and mortality. The “Heatstroke Alert” system in Japan can be seen as a practical application of the “early warning system” component recommended in their review. Our hypothesis that this “push-style” delivery of information encourages habitual action, rather than relying solely on knowledge, aligns with their finding that educational interventions combined with tangible resources are effective for behaviour change. The significant increase in preventive measures in Fukuoka between 2020 and 2022 is consistent with the intended outcomes of structured, government-led public health interventions, suggesting their potential contribution.

Limitations and future scope

This study has some limitations, which can be addressed by future research. Firstly, the findings of this work are derived from a municipal survey in Fukuoka City, which may limit direct generalizability to other regions with different demographics and climate conditions. Secondly, the questionnaire relies on self-reported experiences, which could be subject to recall bias or social desirability bias. Thirdly, the surveys were conducted in two different periods (2020 and 2022), and environmental or situational factors (such as temperature or public health campaigns) have differed across these periods. Furthermore, this study could not account for factors such as time spent outdoors for employed respondents, nor for other socioeconomic variables such as educational background or living arrangements (e.g., living alone), which could potentially influence HS risk and awareness levels. It should also be noted that survey weights were not considered in the analysis since this study focused on identifying the determinants of the outcomes of interest along with estimating their effects on HS experience, knowledge, and preventive-measures adaptation, rather than producing nationally representative estimates of specific indicators45,46,47.

Further studies are needed to address these issues and, more importantly, to establish a logical pathway among the three variables: past experience of HS, knowledge of HS symptoms, and HS preventive measures. A structural equation model could be employed to explore the interrelationships among these variables. Furthermore, a more nuanced, time-sequenced dataset should be collected to enable the use of quasi-experimental or mediation-based analytical approaches to more rigorously examine the pathways linking heat-related exposure, HS knowledge, and preventive behaviours.

Conclusions

This study reveals key findings to enhance public health strategies against heatstroke (HS). Firstly, a robust understanding of HS symptoms is a more powerful driver of preventive behaviour than personal experience with mild symptoms. Secondly, the findings highlight distinct challenges across demographics: for older adults, who are already taking more preventive actions, interventions should focus on ensuring their knowledge leads to timely symptom recognition. For younger individuals, the focus must be on closing the critical behavioural gap, where frequent symptom experience is not translating into preventive action. Finally, the increase in preventive actions in 2022 suggests that trigger-based risk communication, such as Japan’s “Heatstroke Alert” system, may be a promising strategy for fostering community-wide change.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the Fukuoka City Environmental Bureau, but restrictions apply to their availability. These data were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. However, data can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the Fukuoka City Environmental Bureau.

References

Watts, N. et al. The lancet countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet 391, 581–630 (2018).

Mora, C. et al. Global risk of deadly heat. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 501–506 (2017).

Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Chen, J. et al. Global socioeconomic exposure of heat extremes under climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123275 (2020).

Xia, D. M. et al. Research progress of heat stroke during 1989–2019: a bibliometric analysis. Mil Med. Res. 8, 5 (2021).

Leon, L. R. & Bouchama, A. Heat stroke. In Comprehensive Physiology. 611–647 https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c140017. (Wiley, 2015).

McLean, K. E., Lee, M. J., Coker, E. S. & Henderson, S. B. A population-based case-control analysis of risk factors associated with mortality during the 2021 Western North American heat dome: focus on chronic conditions and social vulnerability. Environ. Res. Health 2, 035010 (2024).

Schulte, F., Röösli, M. & Ragettli, M. S. Heat-related cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in switzerland: a clinical perspective. Swiss Med. Wkly. 151, w30013–w30013 (2021).

O’Lenick, C. R. et al. Impact of heat on respiratory hospitalizations among older adults in 120 large U.S. Urban areas. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 22, 367–377 (2025).

Kjellstrom, T. et al. Human performance, and occupational health: A key issue for the assessment of global climate change impacts. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 37, 97–112 (2016). Heat.

Kovats, R. S. & Hajat, S. Heat stress and public health: A critical review. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 29, 41–55 (2008).

Xiang, J., Bi, P., Pisaniello, D. & Hansen, A. Health impacts of workplace heat exposure: an epidemiological review. Ind. Health 52, 91–101 (2014).

Antony, A. et al. Demography and clinical profile of heatstroke patients. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.81852 (2025).

Toosty, N. T., Hagishima, A. & Tanaka, K. I. Heat health risk assessment analysing heatstroke patients in Fukuoka City, Japan. PLOS ONE. 16, e0253011 (2021).

Sheridan, S. C. & Allen, M. J. Temporal trends in human vulnerability to excessive heat. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 043001 (2018).

Mayrhuber, E. A. S. et al. Vulnerability to heatwaves and implications for public health interventions – A scoping review. Environ. Res. 166, 42–54 (2018).

Ashbaugh, M. & Kittner, N. Addressing extreme urban heat and energy vulnerability of renters in Portland, OR with resilient household energy policies. Energy Policy. 190, 114143 (2024).

O’Neill, B. et al. Key risks across sectors and regions. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II To the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed Pörtner, H. O.) (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Matthies, F. & Menne, B. Prevention and management of health hazards related to heatwaves. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 68, 8–12 (2009).

Huang, C. et al. Managing the health effects of temperature in response to climate change: challenges ahead. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 415–419 (2013).

Hasan, F., Marsia, S., Patel, K., Agrawal, P. & Razzak, J. A. Effective Community-Based interventions for the prevention and management of Heat-Related illnesses: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 8362 (2021).

Martinez, G. S. et al. Heat-health action plans in europe: challenges ahead and how to tackle them. Environ. Res. 176, 108548 (2019).

Heat and Health in the WHO European Region: Updated Evidence for Effective Prevention. (WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, 2021).

Alebaji, M. B. et al. Knowledge, Prevention, and practice of heat strokes among the public in united Arab Emirates (UAE). Int. J. Med. Stud. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijms.2022.1269 (2022).

Istiqomah, I. N. & Azizah, L. N. Heatstroke prevention behavior by pilgrims from Lumajang, East Java, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 485, 012057 (2020).

Maurya, P., Mishra, J., Chaudhari, A., Soni, P. & Rawat, P. A study to assess the knowledge regarding heat stroke and is prevention among farmers in selected rural Area, Lucknow. Nternational J. Multidiscip Res. IJFMR 6, (2024).

Sheridan, S. C. A survey of public perception and response to heat warnings across four North American cities: an evaluation of municipal effectiveness. Int. J. Biometeorol. 52, 3–15 (2007).

Fujibe, F. Long-term variation in heat mortality and summer temperature in Japan. Tenki. 60(5), 371–381 (2013).

Hayashida, K., Shimizu, K. & Yokota, H. Severe heatwave in Japan. Acute Med. Surg. 6, 206–207 (2019).

Kotani, K. et al. Effects of high ambient temperature on ambulance dispatches in different age groups in Fukuoka, Japan. Glob Health Action. 11, 1437882 (2018).

Oka, K., Honda, Y. & Hijioka, Y. Launching criteria of ‘Heatstroke alert’ in Japan according to regionality and age group. Environ. Res. Commun. 5, 025002 (2023).

Economic Statistics Department, The Economic and Social Research Institute, Office, C. & Government of Japan. Consumer Confidence Survey, Survey Results conducted in March 2021. Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&toukei=00100405&tstat=000001014549 (2021).

Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Current situation and measures against heatstroke. (2022).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Heat Stroke Prevention Council. https://www.wbgt.env.go.jp/heatillness_rma.php

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Ambulance dispatches due to heatstroke. https://www.fdma.go.jp/disaster/heatstroke/post3.html

McHugh, M. L. The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Med. 143–149. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2013.018 (2013).

Dobson, A. J. & Barnett, A. G. An Introduction To Generalized Linear Models, Fourth Edition https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315182780 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018).

Ananth, C. Regression models for ordinal responses: a review of methods and applications. Int. J. Epidemiol. 26, 1323–1333 (1997).

Lall, R., Campbell, M. J., Walters, S. J. & Morgan, K. A review of ordinal regression models applied on health-related quality of life assessments. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 11, 49–67 (2002).

McCullagh, P. Regression models for ordinal data. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 42, 109–127 (1980).

StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. (2015).

Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis (Wiley-Interscience, 2013).

The Bureau of Statistics of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. National Population Census. Portal Site Official Stat. Japan https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&toukei=00200521&tstat=000001080615 (2015).

Fujimoto, M., Hayashi, K. & Nishiura, H. Possible adaptation measures for climate change in preventing heatstroke among older adults in Japan. Front Public. Health 11, (2023).

Khan, J. R., Bari, W. & Latif, A. H. M. M. Trend of determinants of birth interval dynamics in Bangladesh. BMC Public. Health. 16, 934 (2016).

Rutstein, S. O. & Rojas, G. Guide To DHS Statistics (ORC Macro, Calverton, 2006).

Winship, C. & Radbill, L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociol. Methods Res. 23, 230–257 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Katsuma Kadono for his work on data curation and to the Fukuoka City Environmental Bureau for providing the data from the municipal surveys. This study utilised existing, anonymized questionnaire data collected by the Fukuoka City government for regular citizen opinion surveys. As these surveys were not initially designed for research purposes, and all participant information was fully anonymized prior to our access, ensuring that individual participants cannot be identified by the researchers, this study was determined to be exempt from formal ethical review. This exemption was granted by our affiliated institution’s ethical guidelines, specifically the Kyushu University’s Standard Operating Procedures for the Ethics Review Board (Observational and Interventional Studies). Consequently, approval from institutional review boards (e.g., Ethics Committees of Kyushu University Hospital and Medical Institutions) approval and individual informed consent were not required for this particular research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.T.: Formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft; B.L.: conceptualization; A.H.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Toosty, N.T., Lala, B. & Hagishima, A. Survey reveals heatstroke awareness and prevention in Fukuoka City, Japan. Sci Rep 16, 864 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32221-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32221-5