Abstract

The influence of muscle mass on post-stroke outcomes remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate whether lean body mass index (LBMI), a surrogate for muscle mass, is independently associated with 3-month outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. We analyzed data of 10,735 patients with acute ischemic stroke enrolled in the Fukuoka Stroke Registry between June 2007 and September 2019. LBMI and fat mass index (FMI) were calculated using validated anthropometric prediction equations. Patients were categorized into sex-specific LBMI quartiles. Outcomes included poor functional outcomes (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score, 3–6), functional dependency (mRS score, 3–5), and mortality at 3 months. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess associations between LBMI and outcomes, after adjusting for clinical covariates and FMI. As LBMI increased, proportions of poor functional outcomes, functional dependency, and mortality decreased. After multivariable adjustment, higher LBMI was associated with lower odds of poor functional outcome and mortality. These associations remained significant even after further adjustment for FMI. In the subgroup analysis, a significant interaction was observed between LBMI and diabetes for poor functional outcomes (P-value for interaction = 0.03). Thus, higher LBMI was independently associated with better short-term outcomes after ischemic stroke, indicating that skeletal muscle mass may be a crucial prognostic factor distinct from fat mass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke remains a major contributor to mortality and disability1. Its clinical prognosis is influenced by a range of factors, including preexisting comorbidities and the quality and timing of acute management2. Therefore, identifying modifiable prognostic determinants is critical for improving clinical outcomes as well as the quality of life of the patients. In our previous study, we observed that overweight individuals exhibited a reduced risk of unfavorable outcomes 3 months after stroke onset, whereas an underweight status was associated with an increased risk3,4. However, the underlying biological mechanisms remain poorly understood, particularly the relative contributions of adipose tissue and skeletal muscle mass to post-stroke prognosis.

Sarcopenia, defined as the loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, adversely affects long-term health outcomes, including decreased quality of life5, increased mortality6, and increased risk of falls7. Recently, it has also been reported to be associated with short-term outcomes in acute conditions, such as in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit8, and patients with heart failure9. Similar associations have been observed in cardiovascular diseases, in which sarcopenia is commonly and independently associated with poor prognosis10. One possible explanation lies in the role of skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ that secretes myokines that regulate metabolism, inflammation, and immune responses11. Loss of muscle mass may disrupt these regulatory functions, thereby impairing systemic homeostasis and recovery. Stroke-related sarcopenia, driven by catabolism, systemic inflammation, and alterations in muscle fiber, contributes to functional decline12. However, whether muscle mass at the onset of stroke predicts outcome remains a topic of debate13,14,15,16.

The accurate and standardized assessment of skeletal muscle mass remains a methodological challenge in clinical research. Conventional techniques, including bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), are commonly used to calculate the appendicular skeletal muscle index (ASMI)13,14,16. Additionally, the temporalis muscle thickness (TMT) measured using computed tomography has also been proposed15. However, these approaches lack consistency across settings and are often impractical during the acute stroke phase. Recently, anthropometric prediction equations have gained attention as feasible alternatives for estimating body composition17. Among these, the lean body mass index (LBMI), derived from simple measurements, has been validated as a reliable surrogate for skeletal muscle mass17,18. In this study, we examined the association between skeletal muscle mass, as estimated by LBMI, and 3-month functional outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 10,735 patients (mean age: 70.4 ± 12.1 years; female: 35.8%) were included in the analysis of 3-month outcomes. The correlation between LBMI and FMI was low in the overall cohort; however, when stratified by sex, stronger correlations were observed, with a particularly high correlation observed in women (Supplementary Table S1). The LBMI values were higher in males than in females (Table 1). Patients with higher LBMI were younger and had higher predicted FMI and BMI. As the LBMI increased, the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia also increased, whereas the prevalence of atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease decreased. With increasing LBMI, the proportion of cardioembolic strokes decreased, whereas the proportion of small-vessel occlusions increased. In addition, patients with a higher LBMI exhibited milder neurological symptoms and were less likely to receive hyperacute reperfusion therapy.

Association between LBMI and clinical outcomes

First, we evaluated the association between LBMI and poor functional outcomes and functional dependency 3 months after stroke onset (Table 2). The proportion of patients with poor functional outcomes and functional dependency decreased progressively with increasing LBMI. After adjusting for potential confounders, including FMI, the ORs for both outcomes were significantly lower across the higher LBMI categories. We also examined the association between LBMI and 3-month mortality (Table 3). The proportion of deaths decreased with increasing LBMI, and the adjusted ORs for mortality were significantly lower across the higher LBMI groups, even after accounting for all potential confounding factors except FMI. Further adjustment for FMI slightly attenuated these associations; however, the ORs remained significantly lower in the second and third quartiles than in the lowest quartile (Q1).

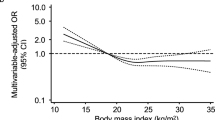

Furthermore, restricted cubic spline analysis stratified by sex demonstrated a statistically significant nonlinear association between LBMI and 3-month outcomes, with the odds of unfavorable outcomes decreasing below the median LBMI and plateauing thereafter (Supplementary Figure S1).

Association between FMI and clinical outcomes

Next, we evaluated the association between FMI and the 3-month functional outcomes after stroke onset (Supplementary Table S2). Although the proportion of poor functional outcomes and functional dependency decreased with increasing FMI, these patterns mirrored those observed in LBMI. In the multivariable-adjusted model, a higher FMI was significantly associated with lower ORs for both outcomes. However, after further adjustment for LBMI, the ORs moved substantially closer to unity, and the statistical significance in the highest quartile (Q4) was attenuated.

A similar trend was observed for the association between FMI and 3-month mortality (Supplementary Table S3). The significant differences observed for Q2 and Q4 in the multivariable model were no longer apparent after adjusting for LBMI.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed two sensitivity analyses. First, to minimize the potential influence of subacute interventions, we assessed the association between LBMI and the clinical outcomes at discharge. The proportions of poor functional outcomes and functional dependency decreased with increasing LBMI, and the multivariable-adjusted ORs were significantly lower. These associations remained significant in Q2 and Q3 compared to Q1, even after additional adjustment for FMI (Supplementary Table S4). Conversely, the association between LBMI and in-hospital mortality was no longer significant after adjusting for FMI.

Second, to address the potential bias related to a history of stroke, which may affect muscle mass or overall health, we analyzed the association between LBMI and functional outcomes in patients with first-ever stroke. Although the association in Q4 lost statistical significance, a trend toward better short-term outcomes with higher LBMI was still observed (Supplementary Table S5).

Subgroup analysis

Finally, subgroup analyses were conducted to assess whether the association between LBMI and the 3-month functional outcomes varied according to age, sex, diabetes mellitus, and obesity/overweight status. Significant heterogeneity in the associations between poor functional outcomes and functional dependency was observed for the diabetes mellitus status (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, no significant heterogeneity was observed in the association with mortality across any of the subgroups examined (Supplementary Figure S3).

Subgroups analysis for association between LBMI and poor functional outcomes at 3 months. OR (square) and 95% CI (horizontal bars) of poor functional outcomes are shown for Q2–Q4 compared to Q1 according to sex, age (< 75 y and ≥ 75 y), diabetes mellitus (yes and no), and obese/overweight (body mass index < 23 and ≥ 23 kg/m2). The multivariable model included the following covariates: age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, drinking, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, history of stroke, stroke subtype (cardioembolism, small-vessel occlusion, large-artery atherosclerosis, or others), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score on admission, and reperfusion therapy. OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

This study had several novel findings. First, a higher LBMI was independently associated with a lower risk of poor functional outcomes, functional dependency, and mortality 3 months after acute ischemic stroke, irrespective of FMI. Second, although higher FMI was associated with a lower risk of these outcomes, its effect was attenuated after adjusting for LBMI. Third, the protective effect of LBMI on clinical outcomes may differ according to the diabetes status, suggesting a potential modification by underlying metabolic conditions.

Previous studies have shown that a lower ASMI is associated with unfavorable outcomes after stroke; however, these studies had relatively small sample sizes (ranging from 164 to 657 participants)13,14,15,16. Although some studies have explored the associations with short-term mortality, their findings are inconclusive14,15. The ASMI is internationally recognized as a standard index of muscle mass, but its assessment typically requires BIA or DEXA, which may be impractical in acute stroke settings19,20. Similarly, TMT requires advanced radiological interpretation and is not feasible in routine clinical practice21. By contrast, the LBMI used in this study offers several advantages. It reflects skeletal muscle mass, correlates strongly with the ASMI18, and can be easily estimated from readily available clinical data, making it suitable for use in large-scale acute care settings.

Regarding outcomes, prior research on obesity and 3-month stroke prognosis has suggested that underweight status is associated with unfavorable outcomes, overweight status with favorable outcomes, and obesity status has associations comparable to those of normal weight3. However, BMI does not distinguish between the fat and lean components of body weight, such as muscle and FM. To better elucidate their respective roles, we simultaneously analyzed LBMI and FMI derived from the predictive equations. Both LBMI and FMI, such as BMI, were independently associated with poor functional outcomes and mortality; however, the effect of FMI was diminished when adjusted for LBMI, suggesting that muscle mass may play a more dominant role in stroke recovery. The association between LBMI and favorable outcomes may be weaker in patients with diabetes. In diabetes, muscle deterioration involves not only loss of mass, but also a qualitative decline (myosteatosis), impaired insulin signaling, reduced mitochondrial function, and altered muscle fiber composition22,23. These changes may impair the rehabilitation response and contribute to metabolic dysregulation and chronic inflammation, which negatively affect recovery. Therefore, a comprehensive approach to skeletal muscle assessment beyond simple mass estimation may be essential for patients with diabetic stroke. Although sex-based heterogeneity in poor functional outcomes was not observed in this study, significant differences in LBMI and FMI values were noted between the sexes, with stronger associations observed in women. This finding is consistent with the fact that older women tend to have lower muscle mass, which contributes to a long-term decline in physical function through frailty24. Indeed, we previously reported that women who were functionally independent at 3 months after ischemic stroke were more likely to become dependent 5 years later25. Future studies should consider sex-specific cutoffs and strategies for sarcopenia and stroke care26. The use of sex-specific thresholds defined by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia and the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People in previous studies further supports the need for sex-sensitive analyses13,14,16.

We demonstrated that the short-term beneficial effects of BMI on functional outcomes after ischemic stroke are more likely attributable to skeletal muscle mass than to FM. Several potential mechanisms may explain the contribution of skeletal muscles to improved short-term outcomes. First, skeletal muscles play a crucial role in maintaining systemic homeostasis8. Reduced muscle mass has been associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased mortality in patients with sepsis and heart failure9,27. Second, skeletal muscles function as endocrine organs by secreting myokines that regulate energy metabolism, cardiovascular function, and inflammatory responses11. Exercise-induced myokine secretion exerts systemic health benefits beyond fat reduction28. Furthermore, preservation of muscle mass may enhance resistance to catabolic stress and improve responsiveness to rehabilitation interventions12. Collectively, these mechanisms may contribute to improved functional recovery. In contrast, the adipose tissue may exert both beneficial and detrimental effects on stroke outcomes. Its energy storage capacity protects against physiological stress, and adipokines such as adiponectin are known to exert anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects29. However, the hypertrophy of adipocytes due to excessive nutrient intake may lead to metabolic abnormalities and increased cardiovascular risk30. In our analysis, the protective effect of FM was attenuated after adjusting for skeletal muscle mass, suggesting that adiposity alone does not uniformly confer any benefits.

These findings underscore the importance of considering FM when evaluating the independent effects of muscle mass. A narrative review that assessed both LBM and FM concurrently reported that a lower LBM was inversely associated with mortality, whereas a higher FM was positively associated with mortality in the general population31. Although evidence in acute stroke populations remains limited, a study of hospitalized patients with advanced heart failure demonstrated that higher LBM was associated with reduced mortality; in contrast, FM showed no significant association27. These data support the notion that skeletal muscle may serve as a more critical determinant of prognosis than FM in acute clinical settings, a concept reinforced by our findings.

The distinct prognostic implications of LBMI and FMI have important clinical relevance. As LBMI can be estimated from readily available clinical information, it may serve as a practical tool for early risk stratification in the care of acute stroke. Incorporating LBMI into prognostic models can help identify high-risk patients and enable personalized early interventions, such as rehabilitation and nutritional support. For example, patients with preserved muscle mass may benefit from early intensive rehabilitation, whereas those with low muscle mass may require targeted nutritional interventions and individualized exercise programs. Future studies should focus on standardizing muscle assessment methods and integrating them into comprehensive stroke management pathways.

This study has several strengths. The large sample size and prospective collection of standardized anthropometric data ensured high data quality with minimal missing values. However, this study had some limitations that must be noted. First, WC was measured in the supine position because many patients were unable to stand post-stroke, which may differ from standard methods; nonetheless, measurements were performed uniformly. Second, LBMI and FMI were calculated using predictive equations, which may be less precise than direct measurements. LBMI includes not only muscle but also bone, organs, and skin tissue, and thus may not perfectly reflect skeletal muscle mass. Moreover, qualitative aspects of skeletal muscle—such as intramuscular fat infiltration (myosteatosis), muscle stiffness, and bioelectrical phase angle—are important determinants of physical function and recovery post-stroke; however, these qualitative characteristics were not directly assessed herein. Reduced muscle quality, which is often observed in older or diabetic individuals even when muscle mass is preserved, may partly modify associations between LBMI and clinical outcomes. Future studies incorporating direct assessments of muscle quality using imaging or bioelectrical impedance analysis could provide a deeper understanding of the relationship between LBMI and stroke prognosis. Third, muscle strength was not assessed for patients in the acute phase of hospitalization. Fourth, the presence of motor impairment during the acute stage might have influenced the observed associations between muscle mass and functional outcomes. Finally, the study population was limited to patients from hospitals in Japan, necessitating further validation for generalizability to other populations.

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of skeletal muscle mass in determining functional and survival outcomes following acute ischemic stroke. These findings suggest that LBMI may be more strongly associated with prognosis than FMI, and highlight the need to consider muscle mass and quality, especially in patients with diabetes or in sex-specific analyses. These results may inform individualized stroke management strategies and underscore the importance of sarcopenia assessment in acute neurological care.

Methods

Study design and participants

The Fukuoka Stroke Registry (FSR) is a multicenter, hospital-based registry of patients with acute stroke within 7 days of onset who were admitted to one of seven stroke centers (see Appendix) in Fukuoka, Japan (UMIN000000800). Each participating hospital obtained ethics committee approval for the FSR (Kyushu University Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research, 22086-00; Kyushu Medical Center Institutional Review Board, R06-03; Clinical Research Review Board of Fukuokahigashi Medical Center, 29-C-38; Fukuoka Red Cross Hospital Institutional Review Board, 629; St. Mary’s Hospital Research Ethics Review Committee, S13-0110; Steel Memorial Yawata Hospital Ethics Committee, 06-04-13; Kyushu Rosai Hospital Institutional Review Board, 21 − 8). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal representatives; permission was obtained from the next of kin or legal guardian as a proxy for patients who could not consent. The present study was performed according to the Ethics of Clinical Research (Declaration of Helsinki).This study was conducted following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines32.

Stroke was defined as the sudden onset of non-convulsive focal neurological deficits. Ischemic stroke was diagnosed by brain computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or both.

In total, 15,569 patients with acute ischemic stroke were prospectively enrolled in the Fukuoka Stroke Registry between June 2007 and September 2019. We excluded 1162 patients with transient ischemic attack, 3,262 functionally dependent patients (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score ≥ 2) before stroke onset, 185 patients with missing data required for multivariable analysis, and 225 patients lost to follow-up at 3 months. Finally, 10,735 patients were included in the primary analysis (Supplementary Figure S4).

Data collection and variables

Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), risk factors and comorbidities, history of previous stroke, and reperfusion therapy, were collected upon admission for the index stroke. The definitions of risk factors and comorbidities have been previously described in detail33,34. The mechanism of ischemic stroke was classified according to the criteria of the Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment35. Stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score.

Exposure measurements

Predicted body composition

We used predicted lean body mass (LBM) and fat mass (FM) as indicators of skeletal muscle mass and adiposity, respectively. These values were estimated using anthropometric prediction equations developed from large-scale data collected by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey17. The equations were constructed using linear regression models with DEXA-measured LBM and FM as dependent variables and simple clinically accessible anthropometric parameters, such as age, race, weight, height, and waist circumference (WC), as independent variables. The specific prediction equations used in this study are as follows:

Prediction equations for lean body mass

Prediction equations for fat mass

Race/ethnicity variables were coded as binary indicators (1 = yes, 0 = no), with White as the reference category. In this cohort, all participants were classified as “Other ethnicity” because they were of Japanese descent.

The LBMI (kg/m²) and fat mass index (FMI) (kg/m²) were calculated as follows:

LBMI = predicted LBM (kg) / height² (m²).

FMI = predicted FM (kg) / height² (m²).

These indices were used in subsequent analyses as standardized measures of skeletal muscle mass and adiposity. Sex-specific quartiles of predicted LBMI and FMI were generated and combined to create overall quartile groups.

Clinical outcome

The study outcomes were poor functional outcomes (mRS score, 3–6), functional dependency (mRS score, 3–5), and mortality, defined as any cause of death at 3 months after onset. In the sensitivity analysis, outcomes were assessed at discharge to avoid the influence of interventions during the post-acute stage. Stroke neurologists evaluated the study outcomes at discharge. A follow-up study at 3 months was performed by well-trained authorized nurses using a standardized questionnaire in person or by telephone.

Statistical methods

Pearson correlation coefficients between predicted LBMI, predicted FMI, and BMI were calculated for the overall population and separately for males and females.

Differences in baseline characteristics were assessed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. Trends in baseline characteristics were evaluated using the Jonckheere–Terpstra test for continuous variables and Cochran–Armitage trend test for categorical variables.

Logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each outcome of interest. Models were adjusted for the following covariates: (1) age and sex (age- and sex-adjusted model); (2) multivariable-adjusted model (MV-adjusted), including age, sex, vascular risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, alcohol consumption, atrial fibrillation, and chronic kidney disease), history of prior stroke, stroke subtype (cardioembolism, small-vessel occlusion, large artery atherosclerosis, or other), NIHSS score on admission, and acute reperfusion therapy; (3) MV-adjusted + FMI or LBMI, in which either FMI or LBMI was added as a continuous variable for mutual adjustment. The same analyses were repeated for FMI to evaluate its association with the 3-month functional outcomes. To assess potential nonlinear associations, restricted cubic spline logistic regression was performed separately for each sex. The number and placement of knots were determined based on Harrell’s recommendations, with four knots placed at specified percentiles of the exposure variable distribution (5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles). ORs and 95% CIs were estimated using the median value as a reference. Nonlinearity was evaluated using likelihood ratio tests to compare models with and without spline terms.

Subgroup analyses were performed using strata defined by sex, age (< 75 or ≥ 75 years), diabetes mellitus, and obesity/overweight status (BMI < 23 or ≥ 23 kg/m²)36. Heterogeneity across the subgroups was tested using the likelihood ratio test by including an interaction term between the LBMI categories and each subgroup variable.

We also conducted sensitivity analyses to minimize potential bias and strengthen the validity of our findings. First, we examined the association between LBMI and 3-month outcomes specifically in patients with first-ever stroke to address potential confounding effects related to prior stroke history. Additionally, we analyzed outcomes at discharge to further confirm the consistency and robustness of the observed associations across different time points.

Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value of < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, United States of America, College Station, TX, USA).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Forlivesi, S., Cappellari, M. & Bonetti, B. Obesity paradox and stroke: A narrative review. Eat. Weight Disord. 26, 417–423 (2021).

Saposnik, G. et al. IScore: A risk score to predict death early after hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke. Circulation 123, 739–749 (2011).

Wakisaka, K. et al. Non-linear association between body weight and functional outcome after acute ischemic stroke. Sci. Rep. 13, 8697 (2023).

Wakisaka, K. et al. Association between abdominal adiposity and clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. PLOS One 19, e0296833 (2024).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. & Sayer, A. A. Sarcopenia. Lancet 393, 2636–2646 (2019).

Xu, J., Wan, C. S., Ktoris, K., Reijnierse, E. M. & Maier, A. B. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontology 68, 361–376 (2022).

Larsson, L. et al. Sarcopenia: Aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol. Rev. 99, 427–511 (2019).

Zhang, X. M. et al. Sarcopenia as a predictor of mortality among the critically ill in an intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 21, 339 (2021).

Konishi, M. et al. Prognostic impact of muscle and fat mass in patients with heart failure. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12, 568–576 (2021).

Damluji, A. A. et al. Sarcopenia and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 147, 1534–1553 (2023).

Pedersen, B. K. & Febbraio, M. A. Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 8, 457–465 (2012).

Scherbakov, N., Sandek, A. & Doehner, W. Stroke-related sarcopenia: Specific characteristics. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 272–276 (2015).

Honma, K. et al. Impact of skeletal muscle mass on functional prognosis in acute stroke: A cohort study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 112, 43–47 (2023).

Lee, S. H., Choi, H., Kim, K. Y., Lee, H. S. & Jung, J. M. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass associated with sarcopenia as a predictor of poor functional outcomes in ischemic stroke. Clin. Interv Aging 18, 1009–1020 (2023).

Lin, Y. H. et al. Association of temporalis muscle thickness with functional outcomes in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy. Eur. J. Radiol. 163, 110808 (2023).

Nozoe, M. et al. Muscle weakness is more strongly associated with functional outcomes in patients with stroke than sarcopenia or muscle wasting: An observational study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36, 4 (2024).

Lee, D. H. et al. Development and validation of anthropometric prediction equations for lean body mass, fat mass and percent fat in adults using the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2006. Br. J. Nutr. 118, 858–866 (2017).

Kawakami, R. et al. Fat-free mass index as a surrogate marker of appendicular skeletal muscle mass index for low muscle mass screening in sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23, 1955–1961e3 (2022).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing 39, 412–423 (2010).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307 (2019) Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. (2020).

Steindl, A. et al. Sarcopenia in neurological patients: Standard values for temporal muscle thickness and muscle strength evaluation. J. Clin. Med. 9, 1272 (2020).

Hickey, M. S. et al. Skeletal muscle fiber composition is related to adiposity and in vitro glucose transport rate in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 268, E453-457 (1995).

Pinti, M. V. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: An organ-based analysis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 316, E268–E285 (2019).

Della Peruta, C. et al. Sex differences in inflammation and muscle wasting in aging and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 4651 (2023).

Irie, F. et al. Sex differences in long-term functional decline after ischemic stroke: A longitudinal observational study from the Fukuoka stroke registry. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 52, 409–416 (2023).

Tseng, L. A. et al. Body composition explains sex differential in physical performance among older adults. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69, 93–100 (2014).

Ge, Y. et al. Association of lean body mass and fat mass with 1-year mortality among patients with heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 824628 (2022).

Zhang, L., Lv, J., Wang, C., Ren, Y. & Yong, M. Myokine, a key cytokine for physical exercise to alleviate sarcopenic obesity. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 2723–2734 (2023).

Ibrahim, M. M. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: Structural and functional differences. Obes. Rev. 11, 11–18 (2010).

Oikonomou, E. K. & Antoniades, C. The role of adipose tissue in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 83–99 (2019).

Lee, D. H. & Giovannucci, E. L. Body composition and mortality in the general population: A review of epidemiologic studies. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 243, 1275–1285 (2018).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

Kamouchi, M. et al. Prestroke glycemic control is associated with the functional outcome in acute ischemic stroke: The Fukuoka stroke registry. Stroke 42, 2788–2794 (2011).

Kumai, Y. et al. Proteinuria and clinical outcomes after ischemic stroke. Neurology 78, 1909–1915 (2012).

Adams, H. P. Jr. et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment in Stroke 24, 35–41 (1993).

Anuurad, E. et al. The new BMI criteria for Asians by the regional office for the Western Pacific region of WHO are suitable for screening of overweight to prevent metabolic syndrome in elder Japanese workers. J. Occup. Health 45, 335–343 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our appreciation to all participants for their involvement in this study. We would also like to thank all investigators at the Fukuoka Stroke Registry for data collection, all clinical research coordinators at the Hisayama Research Institute for Lifestyle Diseases for their assistance in obtaining informed consent, collecting clinical data, conducting follow-up surveys, and Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

G.H. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, and visualization. K.N. contributed to writing—review & editing, data curation, validation, and supervision. F.I. contributed to writing—review & editing, methodology, data curation, and supervision. N.S. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, and data curation. T.K. contributed to supervision. T.W. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, and supervision. R.M. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, and funding acquisition. M.K. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. T.A. contributed to supervision and project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashimoto, G., Nakamura, K., Irie, F. et al. Impact of lean body mass index on short-term outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke: an observational cohort study. Sci Rep 16, 2470 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32252-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32252-y