Abstract

Pithecellobium dulce represent a valuable source of biologically active phytoconstituents. This study aimed to screen the methanolic extract for its different phytochemical classes, isolate the active principles from the ethyl acetate fraction, and conduct phenolic profiling using the HPLC-DAD technique. Additionally, the antioxidant, wound-healing, and cytotoxic activities were assessed in vitro. The molecular modelling (docking) studies are performed for the investigation of cervical and breast cancer cytotoxic activities for some isolated compounds. The extract phytochemical screening revealed the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, terpenes, sterols, tannins, saponins, carbohydrates, and reducing sugars. Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside (Afzelin) (1), fisetin 3-O-rhamnoside (2), and alangilignoside D (3) were isolated and identified from the ethyl acetate fraction using LC-MS, 1H and 13C NMR analysis. The methanolic extract showed total phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, and alkaloids of 51.44 mg GAE/g extract, 49.48 mg RE/g extract, 145.5 mg CE/g extract, and 18.62%, respectively. HPLC-DAD analysis enabled identifying and quantifying 13 phenolic acids and 7 flavonoids. The extract’s antioxidant activity was assessed using DPPH and ORAC assays, revealing an IC50 of 239.5 ± 8.42 µg/ml and 575.94 ± 11.30 µM TE, respectively. The extract achieved a wound closure % of 78.78 after 72 h. The cytotoxic activity was assessed against 4 cancer lines using the MTT assay, which revealed significant cytotoxic activity against the HeLa cell line, using cisplatin as a reference drug. The present investigation dealt with molecular modelling (docking) of the potent compounds showing their anticancer activities targeting cervical carcinoma HeLa cell line and breast cancer cell line MCF-7 for BCL-2 XL and EGFR. Consequently, P. dulce can be considered an effective natural antioxidant and cytotoxic agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medicinal plants have long been recognized as valuable sources of potential treatments for various human diseases. The medicinal value of these plants is attributed to their phytochemicals, including alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, saponins, steroids, glycosides, tannins, and terpenoids. These compounds have proven effective against cancer, diabetes, inflammation, and many other disorders. The therapeutic properties of medicinal plants have spurred interest in alternative medicine, which often has fewer side effects than conventional drugs. Plant extracts have shown effectiveness in cancer therapy due to their bioactive components and many cancer treatments were derived from plants1.

Numerous natural bioactive compounds are known for their antioxidant activity. This ability to scavenge free radicals is crucial, as free radicals are linked to numerous life-threatening disorders. In recent decades, medicinal plants have become an important source of natural antioxidants, playing a key role in treating various human ailments. Therefore, plants with strong antioxidant activity may have the potential to treat a range of illnesses where oxidative stress is a significant factor2.

Cancer is the second greatest cause of mortality in both developed and developing nations3. In 2020, over 18.1 million cancer cases were reported globally. Lung and breast cancers are the most prevalent malignancies worldwide. Cervical cancer ranks as the fourth most prevalent cancer among women and the seventh overall in cancer incidence. As the worldwide burden of cancer continues to rise, one of the greatest public health concerns of the twenty-first century is cancer prevention4. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) protein expression has moderate to high levels in Cervical cancer5. EGFR is overexpressed in 91% of advanced cervical cancer6. Also overexpression of EGFR or the high activity of EGFR signal pathway has been related in breast cancer patients with increases in cell proliferation7. Apoptosis is known to be regulated by the BCL-2 gene regulates apoptosis, which encodes a cellular protein that inhibits apoptosis in normal cell8. The progression of premalignant cervical lesions to invasive malignancy is linked to the expression of BCL-2, and the prognostic value of BCL-2 as a predictor of treatment outcomes in cervical cancer have been evaluated via various studies9.

Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. family Leguminosae is a moderately sized perennial tree with a wide geographical distribution. Out of 100–200 species of Pithecellobium, P. dulce popularly known as “Manila tamarind”, is the only one that has expanded outside its native range. The word “dulce” indicates the pulp’s sweetness in the species’ Latin name. However, the Greek words “Pithekos” (ape) and “Lobos” (pod), which describe the real shape of the pod, are combined to form the genus10.

Historically, different P.dulce extracts have been utilized to treat various ailments in multiple nations due to several physiologically active phytoconstituents. P. dulce has been scientifically proven to possess numerous biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, antibacterial, antiulcer, antioxidant, anticancer, hepatoprotective, antidiarrheal, cardioprotective, and nephroprotective activities11.

P. dulce fruit is consumed in various parts of India raw due to its sweet flavor and as a decoction or mixed with atole (a hot beverage made with corn flour) or agua fresca (a cold tea)12. The seeds can be boiled, roasted, or used as a substitute for coffee. It can also be used as a condiment to treat diabetes mellitus and stomach ulcers13. The infusion of leaves relieves toothaches, earaches, gallbladder, and intestinal problems. Vitamins like ascorbic acid, niacin, thiamine, and riboflavin, as well as several amino acids such as valine, phenylalanine, lysine, and tryptophan, and a few valuable minerals like Ca, Na, P, K, and Fe, are present in P. dulce fruits and seeds, which increase its nutritive value14. Given its rich nutrient profile and various medicinal uses, P. dulce may have potential applications in cancer prevention.

In our previous work, 67 phytoconstituents of different chemical classes mainly flavonoids and phenolic acids were identified from the methanolic extract of P. dulce leaves using UPLC-ESI–MS/MS technique. In addition, the extract demonstrated a neuroprotective and anti-amnesic property against scopolamine-induced cognitive decline and cerebral damage through the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity, reduction of dopamine and noradrenaline levels, and elevation of acetylcholine content in the brain. The extract also demonstrated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties15.

The present study was designed to explore other potentials of P. dulce by exploring the phytochemical constituents of the leaves’ methanolic extract through their isolation via column chromatography. Besides, phytochemical screening of various classes and profiling of phenolic compounds utilizing high-performance liquid chromatography with a diode array detector. Furthermore, the study assessed the total content of phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, and alkaloids, and assessed the biological activities for possible antioxidant, wound-healing, and cytotoxic properties. Also applying molecular modelling (docking) studies to determine the binging mode of the potential compounds with the targeted enzymes in the cytotoxic activity on both cervical cancer HeLa cell line and breast cancer cell line MCF-7.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents, and materials

All experiments and methodologies, including plant collection, were conducted in compliance with national and international regulations as followed by the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sadat City, Sadat City, Egypt.

The following chemicals, solvents and reagents were used: distilled water, concentrated H2SO4, ferric chloride, Fehling’s A, B, Dragendorff’s reagent, potassium hydroxide, acetone, sodium hydroxide, methanol, ethyl ether, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, n-hexane, aluminum chloride, ammonium hydroxide, dimethyl sulfoxide, cisplatin, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, fetal bovine serum, penicillin G sodium (10.000 UI), streptomycin (10 mg), amphotericin B (25 µg) (PSA), sodium dodecyl sulfate- hydrochloric acid (SDS-HCL), Trolox, rutin, gallic acid, catechin, DPPH, APPH, acetic acid, and Na2CO3.

Plant material

The leaves of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. were collected in September 2020 from a private garden of Prof. Dr. Omar Ahmed Tamam in El-Rabwa City, 6th of October City, Giza, (29°54’21.6” N 30°55’27.2” E). The plant was verified by Prof. Dr. Abdel-Halim Abdel-Magley, Head of the Flora and Phytotaxonomy Research Unit at the Horticulture Research Institute in Giza, Egypt. Under reference number CAIM-218, a voucher specimen was maintained in the Flora and Phytotaxonomy Research Unit of the Horticulture Research Institute in Giza, Egypt.

Extraction and fractionation

The leaves of P. dulce (2 kg) were air-dried in the shade, ground into a coarse powder, and macerated in methanol (10 L) then filtered. The maceration process was repeated multiple times until no further extraction was possible. Following full extraction, the extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator at low temperatures (less than 40 °C) under vacuum until complete dryness. The prepared dry extract (200 gm) was liquid-liquid fractionated utilizing different organic solvents of ascending polarities (n-hexane, DCM, and EtOAc) to obtain the n-hexane fraction (52 gm), DCM fraction (11 gm), EtOAc fraction (20 gm), and the remaining aqueous fraction (50 gm). All the obtained fractions were then concentrated and kept in the refrigerator at (4 °C) for further investigation.

Phytochemical investigation

Phytochemical screening

Freshly prepared P. dulce leaves’ extracts were tested for the presence of different classes of phytoconstituents using the different phytochemical tests16,17 mentioned in detail in (Table S1).

Isolation of compounds

The ethyl acetate fraction (20 g) previously prepared was subjected to column chromatography utilizing normal phase silica gel column mesh size (60–200 µ) and was gradually eluted using a mobile phase consisting of different ratios of n-hexane: dichloromethane (DCM) (1:1), and the polarity was increased by 5% until DCM 100%. Then, elution was completed using several ratios of DCM: MeOH which gradually increased by 5% until 100% MeOH. The obtained fractions were collected by TLC monitoring and sprayed with several reagents specific for different chemical classes to obtain 30 fractions. Three compounds were isolated Compound (1) (50 mg) was obtained as yellow crystals from the purification of fraction 8 with DCM: MeOH (9:1). Compound (2) (25 mg) was obtained as yellowish-brown crystals from fractions (20–30) of the Sephadex sub-column of fraction (10–12) from EtOAc silica gel column chromatography, which was subjected to the preparative TLC method using silica gel and DCM: MeOH (8.5:1.5) as a mobile phase. Compound (3) (36 mg) was obtained as a white amorphous powder from fractions 14–17 of the Sephadex (20 L) sub-column eluted with MeOH of fraction (10–12) from EtOAc silica gel column chromatography. The isolated compounds were detected by TLC using a UV-Vis lamp, sprayed with AlCl3, and p-anisaldehyde, and identified via LC/MS, NMR (500 MHz 1H NMR and 100 MHz 13C NMR).

Total phenolics (TP) and total flavonoids (TF) content

The total phenolics in the methanolic extract of P. dulce were analyzed using Folin–Ciocalteu and standard gallic acid according to18. The total phenolic content was determined by utilizing the following equation: \(\:\text{Y\hspace{0.17em}=\hspace{0.17em}0.0031x\hspace{0.17em}-\hspace{0.17em}0.0564}\) (R2 = 0.9961) based on the calibration curve (Fig. S1A) and expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per g of extract (mg GAE/g extract) ± standard deviation. Additionally, the total flavonoid content was computed according to19 employing the aluminum chloride colorimetric technique. The results were expressed as the mg rutin equivalent (RE) per g of extract (mg RE/g extract) ± standard deviation using the following equation \(\:\text{Y\hspace{0.17em}=\hspace{0.17em}0.0032x\hspace{0.17em}+\hspace{0.17em}0.0398}\) (R2 = 0.9981) based on the calibration curve (Fig. S1B).

Total condensed tannins content

The total condensed tannins were obtained by using the acidic vanillin method in a 96-well microplate20. A micropipette was used to transfer 25 µL of sample to a labeled well in the microplate, after which 150 µL of vanillin (4%in MeOH) and 75 µL of HCl (30%) were incorporated. After 15 min, the absorbance was determined utilizing a microplate reader at 500 nm. Different concentrations of standard catechin were prepared (125, 200.250, 300, and 400 µg/mL) in methanol. The results were expressed as mg catechin equivalent (CE) per g of the extract (mg CE/g extract) using the calibration curve (Fig. S1C) and the following equation \(\:\text{Y\hspace{0.17em}=\hspace{0.17em}0.0027x-0.1231}\) (R2 = 0.9624)21.

Total alkaloids content

200 ml of acetic acid (10% in ethanol) was mixed with 5 g of the extract, which was then weighed into a beaker. The mixture was then covered and left for 4 h. After filtering, the extract was concentrated to one-quarter of its initial volume. Until the precipitation was complete, concentrated NH4OH was added dropwise to the extract. The precipitate was collected, settled, cleaned with diluted NH4OH, and filtered22. The residue was dried and weighed, and the alkaloid percentage was calculated according to the equation:

HPLC-DAD phenolic profiling

The leaves’ powder was extracted in a conical flask using 20 mL of 2 M NaOH. N2 was used to flush the flask, and the stopper was installed. After 4 h of shaking the flask at room temperature, 6 M HCl was employed to correct the pH to 2. The flask was centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 rpm, then the supernatant was obtained. The phenolic compounds were extracted twice using 50 mL of (1:1) Et2O and EtOAc. The organic layer was taken out and evaporated at 45 °C. The resulting residue was dissolved using 2 mL MeOH. The volume of injection was 50 µL and all samples underwent filtration using the Gelman Laboratory, MI Acrodisc syringe filter (0.45 μm)23.

The HPLC analysis was conducted using the method described by24 utilizing an 1100 series liquid chromatograph from Agilent Technologies coupled with an autosampler and a diode-array detector. The employed analytical column was an Eclipse XDB-C18 (150 × 4.6 μm) and a particle size of 5 μm. Also, a (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) C18 guard column was used. The mobile phase comprised solvents A and B (acetonitrile) and (2% acetic acid in H2O), respectively. The flow rate was maintained at 0.8 mL/min for the 60-minute run. The gradient program consisted of the following steps: transitioning from 100% to 85% B over 30 min, then from 85%to 50%B over 20 min, followed by a transition from 50% to 0% B in 5 min, and finally from 0%to 100%B in 5 min. The peaks were observed at 280, 320, and 360 nm. It was possible to identify the peaks by comparing their retention time and UV spectra to those of the standards.

Biological investigation

Total antioxidant activity

DPPH assay

The DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate) assay was performed according to previous methods25. In brief, a 96-well plate was used to mix 100 µL of fresh DPPH (0.1% in MeOH) and 100 µL of the extract (n = 3). The mixture was allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Then, the color intensity of DPPH was measured at 540 nm, mean ± SD are used to represent the data. The radical scavenging activity (%) was determined using the equation:

where (Ac) represents the control absorbance and (As) represents the extract absorbance. A microplate reader (FluoStar Omega) was utilized to document the results. A standard solution of 100 µM Trolox in MeOH was used to prepare seven concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µM). Microsoft Excel was used to analyze the data, and Graph Pad Prism 5 was used to obtain the IC50 values through logarithmic conversion of the concentrations and the use of the nonlinear regression equation (Fig. S2A)26.

ORAC assay

Using the method of Liang et al.27 with minor modifications, an oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay was conducted. In brief, 12.5 µL of the prepared extract (100 µg/mL in methanol) was incubated for 30 min with 75 µL of fluorescein (10 nM) at 37 °C in a 96-well plate. Three cycles of fluorescence measurements (485 EX, 520 EM, nm) were conducted (cycle time, 90 s.). Next, 12.5 µL of recently made 2,2’-azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) (240 mM) was promptly incorporated into each well. For 2.5 h, fluorescence measurements (485 EX, 520 EM, nm) were carried out (100 cycles, each 90 s) using microplate reader FluoStar Omega. The extract antioxidant activity was determined as µM Trolox equivalent using the linear regression equation \(\:\text{Y= 32356.3x + 989769.9}\) (R2= 0.9957) (Fig. S2B). The data are presented as the means (n = 3) ± SD.

Wound healing activity

The methanolic extract of P. dulce leaves was investigated as a wound-healing aid28 as follows: Human skin fibroblast (HSF) cells obtained from Nawah Scientific Inc. (Mokatam, Cairo, Egypt) were cultured (2 × 105 cells/well) onto a 12-well plate for wound scratch assays, in 5% fetal bovine serum-Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (FBS - DMEM) and then incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The following day, horizontal wounds were inflicted on the confluent monolayer; the plate was carefully cleaned with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the control wells were filled with fresh medium, and the test wells were filled with extract (50 µg/mL) in fresh media. The experiment was conducted in triplicate. An inverted microscope was used to take images periodically during the incubation period for 72 h29. Version 3.7 of MII Image View software was utilized to analyze wound closure and scratch width at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. time intervals30,31.

The migration rate was determined using \(\:\text{(Rm = }{\text{W}}_{\text{i}}\text{-}{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}\text{/t),}\) where Rm represents the cell migration rate, Wi represents the mean initial wound width, Wf represents the mean final wound width, and t represents the migration duration in hrs. The wound closure percentage was computed from \(\left( {{\text{A}}{{\text{t}}_{0{\text{hr}}}} - {\text{A}}{{\text{t}}_{\Delta {\text{h}}}}/{\text{A}}{{\text{t}}_{0{\text{hr}}}}} \right) \times 100\), where At0hr is the mean wound area recorded at time zero after scratching and AtΔh is the mean wound area determined hours after the scratch was made.

Cytotoxic activity

Cell lines

P. dulce leaves methanolic extract cytotoxicity was screened against four cell lines of cancer, namely, human lung cancer (A-549), human cervical carcinoma (HeLa), human osteosarcoma (Saos-2), and human breast cancer (MCF-7), and one normal cell line, human fetal lung fibroblast (WI-38) (American type culture collection, LGC Promochem, UK). The source of the cells used in this study was Global Research Labs, Nasr City, Cairo 11,528, Egypt. The IC50 was determined for the cell line that exhibited increased activity. The screening and IC50 calculations were carried out utilizing the MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2 H-tetrazolium bromide).

In vitro screening of cytotoxic efficacy

A-549, WI-38, Saos-2, HeLa, and MCF-7 cells were implanted in 96-well culture plates the day before the experiment was carried out. The culture plates were seeded with an average of 10,000 cells in 200 µL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) mixed with FBS (10%) and PSA (1%) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment to achieve 70% confluence. The next day, 100 µg/L P. dulce extract was added and incubated with cancer cells for 48 h. Additionally, the control cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%). Cisplatin was utilized as a positive control32.

MTT assay and IC50 calculation

Thermo Fisher, Germany Vybrant MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (cat. no.: M6494) was used to conduct the cytotoxicity assay. Using DMEM, the cells (8 × 103 cells per well) were plated and incubated in 96-well culture plates for 48 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Next, 100 µL of fresh media and 20 µL of MTT solution (1 mg/mL) were added to each well. Then, the plates were incubated in the same conditions for four hours. Finally, The MTT solution was eliminated, and 100 µL of SDS-HCl was introduced to the wells. The cell viability was assessed by using a spectrophotometer (ELx 800; Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) to measure the optical density at 570 nm, and cisplatin was utilized as a positive control.

Serial dilutions of the extract, including 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 100 µg/mL, were used to treat HeLa cells. The cancer cells were subjected to the previously described cell proliferation experiment. The correlation relating to the log dose of the extract and the normal response was explained using the linear regression curve. GraphPad Prism software 9 was utilized to compute the half-maximal stimulatory concentration (IC50).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was employed for the data statistical analysis, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests, the unpaired t-test to check for equality between two group averages, and the p-value to establish the significance level. After revision and coding, the gathered data were imported into GraphPad Prism Software 9. For parametric numerical data the mean, standard deviation (± SD), and range were employed.

Molecular modeling and docking

Protein target selection and preparation

The 3-dimensional (3D) X-ray crystallographic structures of BCL-2 and EGFR proteins with PDB IDs: 2W3L and 1xkk respectively were obtained from The Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) protein (URL: https://www.rcsb.org) data library. The proposed compounds were choosing for docking study via the use of CDOCKER protocol in the Accelrys Discovery studio 2.5 program using CHARMm-based molecular dynamic (MD) scheme to dock ligands into a receptor binding site. The complexes bound to the receptor molecule, such as non-essential water molecules, including heteroatoms were removed from the target receptor molecule. Finally, hydrogen atoms were added to the target receptor molecule.

The docked compounds

The three LC-MS, H1 isolated compounds Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside (Afzelin) (1), fisetin 3-O-rhamnoside (2), and alangilignoside D (3) and also the top 6 compounds with the highest concentration (> 100 Concentration (µg/g)) in phenolic content in Table 3 of HPLC-DAD phenolic profiling were chosen for the docking study investigations on both PDB pockets of (2W3L, and 1XKK) for both cervical and breast cancer cell lines. The results of the docking studies were listed in Table 5.

Results and discussion

Phytochemical investigation

Phytochemical screening

P. dulce leaves phytochemical screening confirmed the presence of medicinally important phytochemical classes such as flavonoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, terpenes and/or sterols, tannins, saponins, carbohydrates, and reducing sugars with the absence of cardiac glycosides.

Isolation of compounds

Three compounds (Fig. 1) were isolated from the ethyl acetate fraction of P. dulce leaves: kaempferol 3-O-rhamnoside (1), fisetin 3-O-rhamnoside (2), and alangilignoside D (3). Notably, fisetin-3-O-rhamnoside and alangilignoside D are being reported in P. dulce for the first time.

Compound (1) (50 mg) was isolated and purified as yellow crystals. Based on the LC-MS/MS spectrum (Fig. S3) and the 1H (Fig. S4) and 13C-NMR (Fig. S5) profiles (Table 1), the molecular formula for Compound (1) was C21H20O10. The compound exhibited a molecular ion peak at m/z 433 [M + H] + & 431 [M - H]− in the LC-MS spectrum33,34,35,36. The 1H-NMR spectrum displayed two aromatic hydrogen signals at δH 6.38 (br.s, 1H) and δH 6.18 (br.s, 1H), which were assigned to C-6 and C-8 hydrogens. Additionally, two signals with ‘ortho coupling’ at δH 7.71 (d, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz) and δH 6.89 (d, 2H, J = 7 Hz), these signals were attributed to H-2’,6’ and H-3’,5’, respectively. The compound was suggested to be a flavonol glycoside owing to the existence of an anomeric hydrogen signal for H-1” at δH 5.27 (br.s, 1 H). The anomeric carbon signal at δC 102.3 indicated the existence of sugar moiety, denoted as rhamnose due to the methyl group at δH 0.77 (d, 3 H, J = 5.8 Hz) and δC 17.9. By comparing all obtained data with those reported, Compound (1) was identified as kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside (Afzelin).

Compound (2) (25 mg) was isolated and purified as yellowish-brown crystals. Based on the LC-MS spectrum37 which exhibited m/z 433 [M + H]+ molecular ion peak (Fig. S6) and the 1H (Fig. S7) and 13C-NMR (Fig. S8) profiles (Table 1)38,39. The compound had a molecular formula of C21H20O10. By comparing all obtained data with those reported, Compound (2) was identified as fisetin-3-O-rhamnoside which was isolated for the first time from the genus Pithecellobium.

Compound (3) (36 mg) was isolated and purified as a white amorphous powder. Based on the LC-MS spectrum40,41 which exhibited a molecular ion peak at m/z 551 [M - H]− (Fig. S9) and the 1H (Fig. S10), 13C, DEPT 13C NMR (Fig. S11), HMBC NMR profiles (Table 2), the compound represented a molecular formula of C27H36O12. The HMBC spectrum (Fig. S12) demonstrated a cross peak correlating the protons signal of the methoxy groups at δH 3.77 (s, 6H) with the carbon signal at δC 147.6 (C-3’,5’), and at δH 3.76 (s, 3H) with the carbon signal at δC 145.93 (C-3). These data confirmed that C-3’,5’, and 3 are blocked with three OCH3 groups. The glucose residue linkage to C 9’ was proven through the cross-peak correlation between the δH 4.36 (H-1”) signal and the δC 65.7 (C-9’) signal. By comparing all obtained data with those reported, Compound (2) was identified as alangilignoside which was isolated for the first time from this species.

Total phenolics and total flavonoids content

The total phenolics in P. dulce leaves methanolic extract was 51.44 ± 1.36 mg GAE/g extract. Moreover, the total flavonoids were 49.48 ± 3.6 mg RE/g extract.

Condensed tannins content

The total condensed tannins of the P. dulce leaves methanolic extract was 145.5 ± 7.6 mg CE/g extract.

Total alkaloids content

The bioactive total alkaloids content in P. dulce leaves was 18.62%.

HPLC-DAD phenolic-profiling

The HPLC-DAD analysis is one of the most frequently applied techniques to identify and quantify flavonoids and phenolic compounds present in plants. This approach is convenient and adaptable, offering numerous advantages such as high resolution, selectivity, sensitivity, and precision42.

The phenolic composition of P. dulce leaves methanolic extract was determined and quantified in µg/g using HPLC–DAD and twenty reference phenolic acids and flavonoids as standards. The HPLC chromatogram (Fig. 2), enabled the determination and quantification of a total of (20) phytoconstituents including (13) phenolic acids and (7) flavonoids (Table 3). Gallic acid and ferulic acid were the most abundant phenolic acids with values of 1433.70, and 941.28 µg/g, respectively. Kaempferol and apigenin showed the highest concentrations among the analyzed flavonoids with values of 370.74 and 234.46 µg/g respectively.

All the quantified compounds possess variable biological activities. Gallic and ferulic acids are among the most abundant phenolic acids reported in plants. Numerous scientific studies document their pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activities43,44. Kaempferol and apigenin are prevalent flavonoid molecules found in numerous plants, exhibiting various biological functions such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities through different mechanisms45.

Biological investigation

Antioxidant activity

Numerous in vitro assays exist to assess the radical scavenging activity of the methanolic plant extract. The radical scavenging effect was carried out using two different assays, the DPPH and ORAC assays due to their simplicity, reproducibility, and ability to measure different aspects of the antioxidant capacity.

The DPPH assay is commonly utilized to assess the free radical scavenging capacity of plant extracts due to its rapidity, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness25. On the other hand, the ORAC assay is thought to simulate the phenolics’ antioxidant activity in biological systems better than other assays as it employs biologically relevant free radicals and integrates the time and the antioxidants’ degree of activity46.

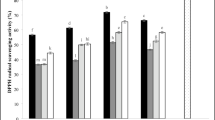

DPPH assay

The antioxidant effect of the leaves methanolic extract was evaluated utilizing the DPPH assay, shown in the initial screening stage, that the IC50 was between 100 and 1000 µg/mL. The dose that achieved 50% inhibition (1000 µg/mL) was serially diluted to five concentrations, revealing an IC50 of 239.5 ± 8.42 µg/mL (Fig. S2A). Trolox as a reference drug exhibits an IC50 of 24.42 ± 0.87 µM.

ORAC assay

The antioxidant activity of the total methanolic extract of P. dulce leaves was 575.94 ± 11.30 µM TE/equivalent (Fig. S2B).

The results of both assays suggest that the phenolic compounds may contribute to the antioxidant activity of the P. dulce extract. Phenolics, which include phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, and the less common lignans and stilbenes, are significant secondary metabolites widely found across the plant kingdom. These metabolites play a critical role in defending against free radicals and oxidative stress. The free radical scavenging activity of the phenolic compounds is due to the presence of hydroxyl groups, where flavonoids inhibit the generation of ROS by chelating trace elements linked to free radical formation, thereby aiding in the ROS scavenging and boosting antioxidant activity46,47.

Wound healing activity

Wound healing is significantly influenced by several mechanisms such as ROS scavenging, apoptosis induction, and enzyme inhibition. These mechanisms can promote tissue repair, reduce inflammation, and enhance wound closure by targeting various cellular functions. By scavenging excessive ROS, antioxidants reduce oxidative stress, promote cell proliferation, and improve tissue repair. This helps in the formation of new blood vessels, collagen synthesis, and overall wound closure48.

Apoptosis helps remove inflammatory cells and damaged tissue, preventing excessive inflammation and promoting tissue remodeling. This ensures that only healthy cells contribute to tissue repair, enhancing the efficiency of wound healing49. Additionally, enzyme inhibition can reduce inflammation, promote collagen synthesis, and enhance tissue remodeling. This promotes wound healing by preserving the extracellular matrix’s structural integrity and facilitating cell migration and proliferation50.

Several studies have reported the potential of many phytoconstituents such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, and alkaloids in wound treatment since they can interact in the various stages of the wound-healing pathway51. The wound scratch assay was employed to evaluate the wound-healing activity of P. dulce leaves. The average distance between the scratch edges at different time intervals (Fig. 3A and C) was used to determine the width of the wound, which diminishes as cell migration is induced, the migration rate and the wound closure percentage (Fig. 3B) were calculated (Table S2) and demonstrated in. P. dulce extract achieved a closure % of 78.78 after 72 h while the control (normal healing) achieved 100% closure after the same time.

Cytotoxic activity

Cytotoxicity in cancer therapy is significantly influenced by mechanisms such as ROS scavenging, apoptosis induction, and enzyme inhibition. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive molecules that cause cellular damage through oxidative stress, playing a crucial role in cancer development and progression52. ROS can activate various signaling pathways that control cell proliferation, survival, and apoptosis. At high concentrations, ROS can induce apoptosis in cancer cells by activating pro-apoptotic signaling pathways, such as the p53 pathway, leading to subsequent cell death. Additionally, ROS can inhibit enzymes involved in DNA repair and cell cycle regulation, causing genomic instability and uncontrolled cell growth. For instance, ROS can inhibit the activity of DNA repair enzymes, resulting in the accumulation of DNA damage53,54.

The cytotoxicity of P. dulce leaves methanolic extract at 100 µg/mL concentration was screened against four cell lines of cancer (A-549, Saos-2, HeLa, and MCF-7), and one normal cell line WI-38 employing the MTT assay. The results revealed that the greatest effect was observed with the HeLa cell line, for which the percentage of viable cells decreased to 13.9%, followed by the MCF-7 cell line, which showed a percentage of viability of 60.28% ± 3.06. The other cell lines (A-549, WI-38, and Saos-2) showed viability percentages of 113.7% ± 1.18, 101.6% ± 0.81, and 107.8%± 0.82, respectively (Fig. 4). The unpaired independent t-test was utilized to compare the cell viability (%) between the treated and untreated cells for each cell line (Table S3). The results revealed a significant cytotoxic effect of P. dulce extract was detected in A-549 vs. A-549 + extract (mean difference: -13.60, p = 0.0001), HeLa vs. HeLa + extract (mean difference: 86.53, p < 0.0001), MCF-7 vs. MCF-7 + extract (mean difference: 39.27, p = 0.0004), and Saos-2 vs. Saos-2 + extract (mean difference: -7.70, p < 0.0023). Conversely, no significant difference between the treated and untreated forms was detected in the WI-38 cells (mean difference: -2.03, p = 0.05).

The HeLa cell line was selected as the best target for the extract effect because it showed the least viability among all the tested cancer cell lines. Cell viability was assessed after treatment with five different concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 µg/mL) of the extract, which inhibited the HeLa cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner. For instance, at 100 µg/mL, the percentage of viable cells was 14.65% ± 3.16, whereas it was 96.17% ± 6.3 at a concentration of 0.01 µg/mL (Table 4). The IC50 was 2.05 µg/mL (Fig. S13). The ANOVA test (Fig. S15) was conducted to assess the significant difference between the cytotoxic effect of extract and untreated cells (negative control) as well as cells treated with standard cisplatin. The findings indicated a significant difference between the cell viability of the three tested groups (F: 929.12, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5). In addition, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (Table S3) revealed that the lowest cell viability was demonstrated in cells treated with cisplatin, and no significant difference was observed when compared to HeLa cells treated with 100 µg/mL extract (mean difference: 2.08, p = 0.50). As previously reported, this cytotoxic activity may result from the presence of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and alkaloids55.

Many of the compounds identified in this study have been proven to possess many biological activities. Afzelin, a flavonoid with diverse properties, presents a potential therapeutic agent owing to its anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and anti-cancer effects, achieved by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting inflammatory pathways with fewer adverse effects than traditional therapies, and may aid in preventing treatment resistance56.

Furthermore, afzelin facilitates wound healing by minimizing UVB-induced cellular damage, decreasing lipid peroxidation, and preventing cell apoptosis in human keratinocytes. It also suppresses the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, thereby diminishing inflammation and facilitating tissue repair57.

Lignans demonstrate antioxidative properties by activating antioxidant enzymes and scavenging free radicals, thereby protecting against human LDL oxidation. They also possess anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, and antimicrobial properties58.

Gallic acid was reported to possess cytotoxic and antitumor effects through the modification of antioxidant/pro-oxidant balance. Also, it can inhibit carcinogenesis induced by reactive oxygen species, through various mechanisms43. Additionally, gallic acid’s antioxidant properties may facilitate wound healing by mitigating oxidative stress at the wound site, facilitating tissue repair, and preventing infection59.

Ferulic acid is a potent antioxidant with the capability to scavenge free radicals and inhibit oxidative stress. It neutralizes ROS and enhances the body’s antioxidant defense systems. Furthermore, ferulic acid inhibits enzymes responsible for free radical generation and boosts the activity of scavenger enzymes. It also protects skin structures such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, collagen, and elastin, thereby accelerating wound healing. Ferulic acid has shown cytotoxic activity against various cancer cell lines by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation. Additionally, ferulic acid and its derivatives have been synthesized and evaluated for their cytotoxic effects on cancer cell lines like HeLa and A-549, demonstrating promising results in inhibiting cancer cell growth and inducing cell death60,61.

Molecular modelling (docking)

The polycyclic phenolic compounds containing more than 3 ring systems (Afzelin, Fisetin O-rhamnoside, and Alangilignoside D) show the highest -CDOCKER Interaction energy near to or higher than the main enzyme ligand in both 2W3L and 1XKK PDB pockets which higher than the tricyclic phenolic compounds (Kaempferol and Apigenin), while the monocyclic phenolic compounds show the lowest scores (ferulic acid, caffeic acid, Gallic acid and Protocatechuic acid) but still have good fitting and binding within the pocket of the targeted proteins. This investigates that the more polycyclic phenolic compounds that mimic the main reference ligands’ structures, the better binding mode, docking, H-bonds and hydrophobic interaction with the enzymes’ binding pocket. The results of the docking studies were listed in the following Table 5.

Docking with PDB pocket (2W3L): Fig. 6-AI–AVIII)

The BCL-2 XL and Phenyl Tetrahydroisoquinoline amide Complex (PDB id: 2W3L) shows the fitting of the reference ligand (Phenyl Tetrahydroisoquinoline amide) in the BCL-2 XL pocket with -CDOCKER interaction energy of (43.4124). This reference ligand contains 6 ring systems that have good fitting within the pocket of the enzyme, (Fig. 6-AI-6-AIII)).

The polycyclic phenolic compound Alangilignoside D that has 4 ring systems (more than 3 ring systems that mimic the reference ligand structure) shows -CDOCKER interaction energy of (44.4558) which is greater than that of the main reference ligand dicked in 2W3L. Also, Afzelin and Fisetin O-rhamnoside show the -CDOCER Interaction energy of (38.4124 and 37.8179) respectively which are near to that of main ligand in 2W3L. These polycyclic compounds with 4 ring systems perform H-bonds with in the binding site and supposed to perform more hydrophobic interactions and better fitting within it due to its polycyclic structure which show structure similarity to the main reference ligand, (Fig. 6-AIV-AVI)).

The tricyclic phenolic compounds (Kaempferol and Apigenin) show the -CDOCKER Interaction energy of (30.0543 and 28.0144) respectively which are > 63% that of main ligand in 2W3L and lower than that of polycyclic compounds having 4 ring systems, but still form H-bond interactions within the BCL-2 XL pocket (2W3L) with good fitting manner in the binging pocket, (Fig. 6aVII-6aVIII).

These scores are followed by that of the monocyclic phenolic compounds (Ferulic acid, Caffeic acid, Gallic acid and Protocatechuic acid) that show the lowest -CDOCKER interaction energy scores (25.4504, 24.355, 20.7058 and 18.7929, respectively) but these scores are considered in a good range of (58% to 42%) that of the -C-DOCKER interaction energy of main ligand docked in 2W3L, and these compounds still perform 3 H-bond interactions within the BCL-2 XL pocket (2W3L) with good fitting to the enzyme pocket, (Figures S16-S19).

(AI), (AII), and (AIII): 3D and 2D Docking and the surface picture of the co crystalline Ligand Phenyl Tetrahydroisoquinoline Amide in BCL-2 XL(PDB: 2W3L). (AIV): Docking of afzelin within 2W3L (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond with GLU95 and 1 H-Bond with LEU96 amino acids. (AV): Docking of Fisetin O-rhamnoside within 2W3L (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond with TYR67 and 1 H-Bond with ASP70 amino acid. (AVI): Docking of Alangilignoside D within 2W3L (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond with ASP70 amino acid. (AVII): Docking of kaempferol within 2W3L (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond with GLU95, 2 H-Bonds with ARG105 and 1 H-Bond with ALA108 amino acids. (AVIII): Docking of apigenin D within 2W3L (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond with GLU95, 1 H-Bond with LEU96 and 1 H-Bond with ARG105 amino acids.

Docking with PDB pocket (IXKK): Fig. 7AI–7AVIII

The EGFR and Lapatinib Complex (PDB id: 1XKK) shows the fitting of the reference ligand Lapatinib in the EGFR pocket with -CDOCKER interaction energy of (69.8465). The reference ligand Lapatinib contains 5 ring systems that have good fitting within the pocket of the enzyme and performs 1 H-BOND with EGFR binding site amino acid MET 793 and also within THR 854 via H2O molecule in the binding pocket, (Fig. 7-AI-AIII).

The polycyclic phenolic compounds containing 4 ring systems Fisetin O-rhamnoside, Afzelin, and Alangilignoside D show -CDOCKER Interaction energy of (59.1423, 58.7544, and 57.2688) respectively which are near to that of main reference compound lapatinib in EGFR binding site 1XKK. These compounds perform H-bonds with in the binding site: Fisetin O-rhamnoside, Afzelin perform 7-H-bonds and 6-Hbonds, respectively within the binding site including 2 H-bonds with in MET793 amino acid that mimic the binding mode of the main reference ligand Lapatinib which perform 1 H-bond with MET793, while Alangilignoside D perform H-bond within THR 854 amino acid but directly via the OCH3 moity (not via H2O molecule) that mimic the binding mode of the main reference ligand Lapatinib that performs H-bond within THR854 but via H2O molecule, (Fig. 7-AIV-VI).

The tricyclic phenolic compounds (Kaempferol and Apigenin) show the -CDOCKER Interaction energy of (40.4677 and 38.4715) respectively which are > 55% that of main ligand in 1XKK and lower than that of the polycyclic phenolic compounds having more 4 ring systems, but still form H-bond interactions within the EGFR pocket (1XKK) including at least 1 H-bond with in MET793 amino acid that mimic the binding mode of the main reference ligand Lapatinib, with good fitting manner in the binging pocket, (Fig. 7-AVII-AVIII)).

Although the monocyclic phenolic compounds (Ferulic acid, Caffeic acid, Gallic acid and Protocatechuic acid) show the lowest -CDOCKER interaction energy scores within the EGFR pocket (1XKK) (28.4905, 25.6133, 24.627 and 22.6784, respectively) but these scores are considered in a range of (41% to 32%) of the -C-DOCKER interaction energy of that of main ligand Lapatinib in 1XKK, and these compounds still perform H-bond interactions within MET 793 of the EGFR pocket (1XKK) that mimic the binding mode of the main reference ligand Lapatinib, with good fitting to the enzyme pocket, (Figures S.20-S.23).

(AI), (AII) and (AIII): Docking of the co crystalline ligand lapatinib and 2D Docking of Lapatinib within the ATP binding site of EGFR62. (AIV): Docking of afzelin within 1XKK (3D and 2D): 2 H-Bonds with MET793, 2 H-Bonds with Lys745, 1 H-Bond with ASP855, and 1 H-Bond with ASN842 amino acids. (7-AV): Docking of Fisetin O-rhamnoside within 1XKK (3D and 2D): 2 H-Bonds with MET793, 2 H-Bonds with Lys745, 2 H-Bonds with ASP855, and 1 H-Bond with ASN842 amino acids. (AVI): Docking of Alangilignoside D within 1XKK (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond directly with THR854 amino acid (not via H2O Molecule). (AVII): Docking of Kaempferol within 1XKK (3D and 2D): 2 H-Bonds with MET793 and 1 H-Bond with ASP855 amino acids. (AVIII): Docking of Apigenin D within 1XKK (3D and 2D): 1 H-Bond with MET793 amino acid.

Conclusion

The phytochemical screening of the P. dulce (Roxb) Benth. leaves methanolic extract revealed the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, terpenes, sterols, tannins, saponins, carbohydrates, and reducing sugars. Thirteen phenolic acids and seven flavonoids were recognized and quantified using HPLC-DAD analysis. In addition, three compounds were isolated from the ethyl acetate fraction, and it is noteworthy that the identified compounds fisetin 3-O-rhamnoside (2), and alangilignoside D (3) are the first to be identified in P. dulce. Besides, the leaves’ methanolic extract exhibited in vitro antioxidant activity and antitumor effect against different cell lines, mainly the cervical carcinoma (HeLa) in a dose-dependent manner. The extract achieved a wound closure percentage of 78.78 after 72 h. The presence of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and tannins is suggested to be responsible for these activities. According to the molecular docking that discovers the binding mechanism and interaction between the proposed potential compounds with in the BCL-2 XL (PDB: 2W3L) and EGFR (PDB: 1XKK) that are overexpressed in cervical carcinoma Hela cell line and the breast cell line MCF-7, the more polycyclic phenolic compounds that mimic the main reference ligands structures, the better binding mode, docking, and H-bonds and hydrophobic interaction with the enzymes’ binding pocket as 4 ring systems polycyclic phenolic compounds (Afzelin, Fisetin O-rhamnoside, and Alangilignoside), followed by tricyclic phenolic compounds (Kaempferol and Apigenin) and then the monocyclic phenolic compounds (Ferulic acid, Caffeic acid, Gallic acid and Protocatechuic acid). Future research, in vivo validation, nanoparticle formulations, or clinical translation is essential to explore the full potential of each phytoconstituent present in the extract and for enhanced therapeutic potential.

Data availability

This article and its supplementary information file include all data generated and analyzed during this study.

Abbreviations

- A-549:

-

Human lung cancer

- APPH:

-

2,2′-azobis (2-amidinopropan) dihydrochloride

- CE:

-

Catechin equivalent

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- DPPH:

-

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- GAE:

-

Gallic acid equivalent

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- HeLa:

-

Human cervical carcinoma

- HPLC-DAD:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detector

- HSF:

-

Human skin fibroblast

- MCF-7:

-

Human breast cancer

- ORAC:

-

Oxygen radical absorbance capacity

- PSA:

-

Penicillin G sodium, streptomycin, amphotericin B

- RE:

-

Rutin equivalent

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Saos-2:

-

Human osteosarcoma

- SDS-HCL:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate with hydrochloric acid

- TE:

-

Trolox equivalent

- WI-38:

-

Human fetal lung fibroblast

References

Banni, M. & Jayaraj, M. Phytochemical characterization and therapeutic potential of leaf of Emilia sonchifolia (L.) DC.: A comprehensive study on functional groups and bioactive compounds. Pharmacol. Res. - Nat. Prod. 5, 100120 (2024).

Banni, M. & Jayaraj, M. Profile of bioactive compounds, in vitro anticancerous and antioxidant activity of stem extracts of Sida cordata. Plant. Biosystems - Int. J. Dealing all Aspects Plant. Biology. 157, 1221–1233 (2023).

Lin, L. et al. Incidence and death in 29 cancer groups in 2017 and trend analysis from 1990 to 2017 from the global burden of disease study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 96 (2019).

Reports, W. World Health Statistics 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs. Sustain. Dev. Goals. (2022).

Vora, C. & Gupta, S. Targeted therapy in cervical cancer. ESMO Open. 3, e000462 (2018).

Viswanath, L. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) overexpression in patients with advanced cervical cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, e16538–e16538 (2014).

Garcia, R., Franklin, R. A. & McCubrey, J. A. Cell death of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells induced by EGFR activation in the absence of other growth factors. Cell. Cycle. 5, 1840–1846 (2006).

Entezari, M., Sheikhan, S. & Khazaie, Z. M. Evaluation of Bcl2 gene expression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells under treatment of Centaurea Behen extract and cisplatin. J. Paramed Sci. 9, 11–16 (2018).

Das, S. et al. Prognostic significance of Bcl-2 expression in carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Lab. Physicians. 0, 1 (2025).

El-hewehy, A., Mohsen, E., El-fishawy, M. & Fayed, M. A. A., Traditional, phytochemical, nutritional and biological importance of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxib.) Benth. Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi. 34, 354–380 (2024).

Dhanisha, S. S., Drishya, S. & Guruvayoorappan, C. Traditional knowledge to clinical trials: A review on nutritional and therapeutic potential of Pithecellobium dulce. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 33, 133–142 (2022).

Monroy, R. & Colín, H. El guamúchil Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth, un ejemplo de uso múltiple. Madera Y Bosques. 10, 35–53 (2004).

Narsing Rao, G. Physico-chemical, mineral, amino acid composition, in vitro antioxidant activity and sorption isotherm of Pithecellobium dulce L. seed protein flour. J. Food Pharm. Sci. 1, 74–80 (2013).

Murugesan, S., Lakshmanan, D. K., Arumugam, V. & Alexander, R. A. Nutritional and therapeutic benefits of medicinal plant Pithecellobium dulce (Fabaceae): A review. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 9, 130–139 (2019).

Elhewehy, A. A. et al. UPLC-ESI–MS/MS phytochemical profile, in vitro, in vivo, and in silico anti-Alzheimer’s activity assessment of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. leaves. Futur J. Pharm. Sci. 11, 30 (2025).

Banni, M. & Jayaraj, M. Identification of bioactive compounds of leaf extracts of Sida cordata (Burm.f.) Borss.Waalk. by GC/MS analysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195, 1–17 (2022).

Fayed, M. A. A. et al. Sterols from Centaurea pumilio L. with cell proliferative activity: in vitro and in silico studies. 21, (2023).

Boly, R., Lamkami, T., Lompo, M., Dubois, J. & Guissou, I. DPPH free radical scavenging activity of two extracts from Agelanthus dodoneifolius (Loranthaceae) leaves. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 8, 29–34 (2016).

Kiranmai, M., Kumar, C. B. & Ibrahim, M. Comparison of total flavanoid content of Azadirachta indica root bark extracts prepared by different methods of extraction. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2, 254–261 (2011).

Broadhurst, R. B. & Jones, W. T. Analysis of condensed tannins using acidified Vanillin. J. Sci. Fd Agric. 29 (1978).

Saci, F., Bachir bey, M., Louaileche, H., Gali, L. & Bensouici, C. Changes in anticholinesterase, antioxidant activities and related bioactive compounds of carob pulp (Ceratonia siliqua L.) during ripening stages. J. Food Meas. Charact. 14, 937–945 (2020).

Harbome, J. B. Phytochemical Methods:Guide To Modern Technique of Plant Analysis (Chapman and Hall, 1973).

Mahnashi, M. H. et al. HPLC-DAD phenolics analysis, α-glucosidase, α-amylase inhibitory, molecular docking and nutritional profiles of Persicaria hydropiper L. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 22, 26 (2022).

Kim, K. H., Tsao, R., Yang, R. & Cui, S. W. Phenolic acid profiles and antioxidant activities of wheat bran extracts and the effect of hydrolysis conditions. Food Chem. 95, 466–473 (2006).

Boly, R., Lamkami, T., Lompo, M., Dubois, J. & GuissouI P. DPPH free radical scavenging activity of two extracts from Agelanthus dodoneifolius (Loranthaceae) leaves. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. (IJTPR). 8, 29–34 (2016).

Chen, Z., Bertin, R. & Froldi, G. EC50 estimation of antioxidant activity in DPPH assay using several statistical programs. Food Chem. 138, 414–420 (2013).

Liang, Z., Cheng, L., Zhong, G. Y. & Liu, R. H. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of twenty-four Vitis vinifera grapes. PLoS One. 9, e105146 (2014).

Main, K. A., Mikelis, C. M. & Doçi, C. L. In vitro wound healing assays to investigate epidermal migration. In Methods in Molecular Biology Book Series (MIMB) 147–154 https://doi.org/10.1007/7651_2019_235 (2019).

Jonkman, J. E. N. et al. An introduction to the wound healing assay using live-cell microscopy. Cell. Adh Migr. 8, 440–451 (2014).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682 (2012).

Rueden, C. T. et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 529 (2017).

Yang, W. et al. Genomics of drug sensitivity in cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D955–D961 (2013).

Akter, M., Parvin, M. S., Hasan, M. M., Rahman, M. A. A. & Islam, M. E. Anti-tumor and antioxidant activity of kaempferol-3-O-alpha-L-rhamnoside (Afzelin) isolated from pithecellobium Dulce leaves. BMC Complement. Med. Ther 22, (2022).

Diantini, A. et al. Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside isolated from the leaves of Schima wallichii Korth. inhibits MCF-7 breast cancer cell proliferation through activation of the caspase cascade pathway. Oncol. Lett. 3, 1069–1072 (2012).

Gurbuz, P., Baran, M. Y., Demirezer, L. O., Guvenalp, Z. & Kuruuzum-Uz, A. Phenylacylated-flavonoids from Peucedanum chryseum. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia. 28, 228–230 (2018).

Bilia, A. R., Palme, E., Marsili, A., Pistelli, L. & Morelli, I. A flavonol glycoside from Agrimonia eupatoria. Phytochemistry 32, 1078–1079 (1993).

Parajuli, P., Pandey, R. P., Trang, N. T. H., Chaudhary, A. K. & Sohng, J. K. Synthetic sugar cassettes for the efficient production of flavonol glycosides in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell. Fact. 14 (2015).

Srinivasan, R., Natarajan, D., Subramaniam Shivakumar, M. & Nagamurugan, N. Isolation of Fisetin from Elaeagnus indica Serv. Bull. (Elaeagnaceae) with antioxidant and antiproliferative activity. Free Radicals Antioxid. 6, 145–150 (2016).

Radhakrishnan, R. & Selvarajan, G. Isolation of fisetin 3-o-glucoside from Vitex negundo and its hypotonicity induced membrane stabilization studies. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 12 http://www.sciensage.info (2021).

Yuasa, K. et al. Lignan and neolignan glycosides from stems of Alangium premnifolium. Vol. 45 (1997).

Simayi, J. et al. UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS and network pharmacology analysis to reveal quality markers of Xinjiang Cydonia oblonga Mill. for antiatherosclerosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022 (2022).

Flandez, L. E. L., Castillo-Israel, K. A. T., Rivadeneira, J. P., Tuaño, A. P. P. & Hizon-Fradejas, A. B. Development and validation of an HPLC-DAD method for the simultaneous analysis of phenolic compounds. Malaysian J. Fundamental Appl. Sci. 19, 855–864 (2023).

Kahkeshani, N. et al. Pharmacological effects of gallic acid in health and disease: A mechanistic review. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 22, 225–237 (2019).

Pyrzynska, K. Ferulicacid—a brief review of its extraction, bioavailability and biological activity. Separations. 11, (2024).

Tian, C. et al. Investigation of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of luteolin, kaempferol, apigenin and quercetin. South. Afr. J. Bot. 137, 257–264 (2021).

Dai, J. & Mumper, R. J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 15, 7313–7352 (2010).

Younis, I. Y. et al. Exploring geographic variations in Quinoa grains: unveiling anti-Alzheimer activity via GC–MS, LC-QTOF-MS/MS, molecular networking, and chemometric analysis. Food Chem. 465, (2025).

Dong, Y. & Wang, Z. ROS-scavenging materials for skin wound healing: advancements and applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, (2023).

Wu, Y. S. & Chen, S. N. Apoptotic cell: linkage of inflammation and wound healing. Front. Pharmacol. 5, (2014).

Kurahashi, T. & Fujii, J. Roles of antioxidative enzymes in wound healing. J. Dev. Biol. 3, 57–70. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb3020057 (2015).

Szliszka, E. et al. Ethanolic extract of propolis (EEP) enhances the apoptosis- inducing potential of TRAIL in cancer cells. Molecules 14, 738–754 (2009).

Liou, G. Y. & Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic. Res. 44, 479–496. https://doi.org/10.3109/10715761003667554 (2010).

Arfin, S. et al. Oxidative stress cancer cell metabolism. Antioxidants. 10, (2021).

Iqubal Ashif & Haque, S. E. Molecular mechanism of oxidative stress in cancer and its therapeutics. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects (ed. Chakraborti, S.) 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-1247-3_150-1 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2021).

Khan, T. et al. Anticancer plants: A review of the active phytochemicals, applications in animal models, and regulatory aspects. Biomolecules. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10010047 (2020).

Kciuk, M. et al. Exploring the comprehensive neuroprotective and anticancer potential of afzelin. Pharmaceuticals. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17060701 (2024).

Shin, S. W. et al. Antagonizing effects and mechanisms of Afzelin against UVB-Induced cell damage. PLoS ONE 8, (2013).

Karimi, R. & Rashidinejad, A. Lignans. In Handbook of Food Bioactive Ingredients 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81404-5_15-1 ((Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Kim, J. W., Choi, J., Park, M. N. & Kim, B. Apoptotic effect of Gallic acid via regulation of p-p38 and ER stress in PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells pancreatic cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2023).

Kiran, T. N. R. et al. Synthesis, characterization and biological screening of ferulic acid derivatives. J. Cancer Ther. 06, 917–931 (2015).

Srinivasan, M., Sudheer, A. R. & Menon, V. P. Serial review ferulic acid: therapeutic potential through its antioxidant property. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 40 (2007).

El Azab, I. H., El-Sheshtawy, H. S., Bakr, R. B. & Elkanzi, N. A. A. New 1,2,3-triazole-containing hybrids as antitumor candidates: design, click reaction synthesis, DFT calculations, and molecular docking study. Molecules 26, 708 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sadat City, Sadat City 32897, Egypt, for providing the necessary facilities for this research.The authors acknowledge Prof. Dr. Omar Ahmed Tamam, Department of Natural Resources, Environmental Studies and Research Institute, University of Sadat City, Sadat City, Egypt, for providing the plant specimens used in this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**A.A.H.:** Phytochemical study, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing original draft & editing. **A.M.F.:** Supervision, Conceptualization, reviewing & editing. R. M. A.: *In silico* study & Software. **E.M. & M.A.A.F.:** Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing original draft, reviewing & editing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elhewehy, A.A., El-Fishawy, A.M., Aly, R.M. et al. Isolation and quantification of polyphenolics, exploration of antioxidant, cytotoxicity, and wound healing activities of Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. Sci Rep 16, 1338 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32257-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32257-7