Abstract

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), the most common primary glomerular disease worldwide, poses challenges in predicting progression at diagnosis—particularly in primary care. This study developed and validated a model to estimate 5-year renal survival and support early risk stratification for personalized management. A total of 1135 patients with biopsy-confirmed IgAN from Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2014–2017) were retrospectively enrolled and randomly assigned to training and internal validation cohorts in a 7:3 ratio. An external validation cohort comprising 352 patients was obtained from three independent centers (2015–2020). To identify robust prognostic variables, 1000 bootstrap samples were generated from the training set, each subjected to tenfold cross-validation to determine the optimal regularization parameter (λ) for the LASSO-Cox model. Variables with non-zero coefficients were recorded across iterations, and the five most frequently selected were used to construct both the XGBoost survival model and a corresponding nomogram. Model performance was evaluated through discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility using ROC curves, Brier scores, calibration curve and decision curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) of the nomogram was 0.951 (95% CI, 0.914–0.988) in the training cohort and 0.927 (95% CI, 0.877–0.978) in the internal validation cohort. In the external validation cohort, the AUC was 0.913 (95% CI, 0.870–0.955). The Brier scores were 0.029 and 0.045 for the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively. DCA further demonstrated the favorable clinical utility of the nomogram. A clinically practical prognostic model incorporating routine clinical and pathological features was developed to estimate 5-year renal survival in patients with IgAN. Specifically designed for primary care settings, the model leverages easily accessible data to enable early identification of high-risk individuals and support personalized long-term management. Its simplicity and applicability in resource-limited environments make it a valuable tool for improving outcomes beyond specialist centers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most prevalent primary glomerulonephritis (GN) globally. According to a global risk map derived from genome-wide association studies, the eastern region of China is identified as a high-prevalence area for IgAN1. The clinical progression of IgAN is highly variable: while some patients maintain stable renal function for years, others progress rapidly to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Reported 10-year renal survival rates range from 57 to 91%2. Due to the recurrent nature of renal inflammation and the risk of progressive kidney function deterioration, early identification of high-risk patients and the implementation of personalized management strategies are crucial for improving long-term outcomes.

Currently, prognostic risk assessment in IgAN primarily relies on traditional models such as the Oxford classification and the International IgAN Prognostic Score. Previous studies have often utilized conventional logistic regression models, which typically suffer from limited sample sizes and fail to adequately address issues like missing or imbalanced clinical data, thus restricting the development of effective predictive tools. In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool in data mining and has rapidly gained traction in the medical field due to its strong computational capabilities, allowing for the exploration of complex relationships between multiple variables and disease outcomes. For instance, Ryunosuke Noda et al. developed a noninvasive diagnostic prediction model for IgAN using ML techniques3, and Ying Zhang et al. constructed a short-term risk prediction model for chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression in patients with IgAN based on clinical data from 443 individuals4. While these studies highlight the potential of ML in IgAN diagnosis and short-term risk prediction, an integrated long-term prognostic model incorporating clinical data, laboratory parameters, and renal histopathologic features has yet to be developed. This gap limits the clinical applicability of ML approaches in the long-term management and personalized treatment of patients with IgAN.

This study aims to develop and validate a 5-year survival prediction model for IgAN using ML approaches, integrating clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, and renal histopathologic features. The objective is to provide accurate long-term outcome predictions for patients with IgAN, thereby improving risk stratification, optimizing individualized treatment strategies, and enhancing the clinical translation of these models into practice.

Methods

Study participants

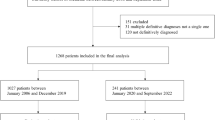

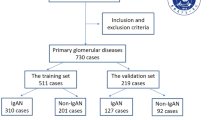

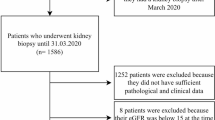

This retrospective study utilized a follow-up dataset of 1,135 patients diagnosed with IgAN who underwent long-term follow-up at Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine from January 2014 to December 2017. An additional dataset of 352 patients diagnosed with IgAN, who underwent long-term follow-up at Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital and Wenzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine between February 2015 and December 2020, was also included. This study received approval from the ethics committee (approval number: 2021KY045). All IgAN diagnoses were confirmed based on histological and immunofluorescence studies of renal biopsies. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age ≥ 18 years; 2) eGFR ≥ 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline; 3) follow-up duration ≥ 6 months; and 4) at least 8 glomeruli. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients with comorbid chronic kidney diseases; 2) patients with secondary causes of mesangial IgA deposits; 3) patients with acute renal failure; and 4) patients with incomplete or ambiguous data. Ultimately, 723 patients were included in the study. The study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

Clinical and laboratory data

Clinical characteristics were collected at the time of renal biopsy (baseline). Data were retrieved from the medical record system of Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine and included variables such as renal biopsy time, gender, age, body mass index (BMI), hemoglobin (Hb), serum albumin (SA), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), blood uric acid (BUA), 24-h urinary total protein (24 h UTP), microscopic hematuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum complement C3 (C3), serum complement C4 (C4), and serum immunoglobulins IgA, IgG, and IgM. The baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Anemia was defined according to standard clinical criteria as Hb < 120 g/L in males and < 110 g/L in females5. The eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula, and eGFR stages were classified as follows: G5 (< 15 mL/min/1.73 m2), G4 (15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2), G3 (30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2), G2 (60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2), and G1 (≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2). All indicators were defined according to traditional cutoff values, following the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines6. Additional details of each variable’s definition are presented in Table 1.

Tissue pathology data

Histopathological data were collected by the Nephrology Department of Hangzhou TCM Hospital, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University. Routine staining of renal biopsy tissue included hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, hexamine silver, and Masson staining. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to assess the expression intensities and renal deposition sites of IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, C4, and C1q (Fig. 2).

For each patient, pathological indicators were scored using the MEST-C classification. Electron microscopy images were used to evaluate foot process effacement (FPE). The MEST-C score characterizes tissue lesions as follows: M for mesangial, E for endocapillary, S for glomerular sclerosis, T for tubulointerstitial damage, and C for crescents. Mesangial lesions were classified as M0 (absence) or M1 (presence) based on the proportion of mesangial cells. Endocapillary and glomerular sclerosis lesions were categorized as E0/E1 and S0/S1, respectively, depending on their presence or absence. Crescents were defined as extravascular proliferation of capillaries of any size exceeding two cell layers. Renal tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis and crescent lesions were graded as T0 (0–25%), T1 (26–50%), or T2 (> 50%) and C0 (none), C1 (0–25%), or C2 (≥ 25%), respectively7. FPE was defined by the disappearance of the normal fissure diaphragm between adjacent foot processes or complete effacement. The extent of FPE was expressed as the percentage of the length of the FPE relative to the total length of each capillary loop; FPE ≥ 50% was classified as widespread FPE, while FPE < 50% was considered segmental FPE8,9. Renal pathology inflammatory cell infiltration (RPICI) primarily consisted of lymphocytes, monocytes, and plasma cells, with neutrophils and eosinophils being less frequent. The degree of inflammatory cell infiltration was classified into four categories: no infiltration, < 25%, > 25% but < 50%, and ≥ 50% inflammatory cell infiltration7. All biopsy specimens were reviewed by two renal pathologists who were blinded to the clinical data.

Endpoint and and follow-up

A composite endpoint was defined as the development of ESRD (eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, dialysis, or kidney transplantation), a doubling of serum creatinine (Scr) levels, or a 40% decline in eGFR within five years after the diagnostic renal biopsy. Information on Scr, eGFR, total follow-up duration, and whether the patient reached the renal composite endpoint within five years was recorded during each follow-up.In cases where information was unavailable, follow-up data were obtained via phone inquiry. To account for the potential competing risk of death occurring prior to renal endpoints, the single patient who died of an unknown cause was excluded from the analysis. This approach was undertaken to minimize bias arising from competing events during model development and evaluation, thereby preserving the integrity of the study cohort and ensuring the robustness of the predictive model.

Statistical analysis

The overall proportion of missing values per variable ranged from 0.2 to 10.6%, with BMI missing in 3.1% of cases, Hb, LDL, and renal C1q in 0.2%, SA in 0.4%, TC in 0.6%, 24 h UTP in 0.8%, MH and renal C4 in 1.2%, serum IgG, IgA, and IgM in 2.3%, serum C3 and C4 in 2.9%, and FPE in 10.6%; overall, no variable exceeded 15% missingness. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) implemented via the mi package in R (version 4.4.1), ensuring sample representativeness and improving result accuracy. Each variable was imputed using a method appropriate to its type: 1) continuous variables: predictive mean matching (PMM); 2) categorical variables: multinomial logistic regression;3) ordinal variables: proportional odds model.We generated five imputed datasets, each subjected to model fitting, and pooled estimates were obtained according to Rubin’s rules to ensure robust inference.Given the single-center origin of the dataset, stringent internal validation protocols were implemented to reduce overfitting and enhance model generalizability. The cohort was randomly split into training (70%) and independent internal validation (30%) sets.

In the training set, bootstrap resampling generated 1000 replicates, each undergoing tenfold cross-validation to identify the optimal regularization parameter (λ) that minimized cross-validation error. LASSO Cox proportional hazards models were then applied to each bootstrap sample at the selected λ threshold, recording variables with non-zero coefficients. Variables were ranked based on their selection frequency across iterations. The top five features were analyzed for correlation and collinearity, with results visualized in Fig. 3 using SHAP plots. These features informed the XGBoost model for predicting 5-year IgAN survival. Model performance was evaluated based on discrimination (AUC), calibration (Brier scores and calibration curve), and clinical utility (decision curve analysis [DCA]).External validation was performed using datasets from Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital and Wenzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine to assess clinical applicability, with AUC values confirming model promising predictive ability.Two validation analyses were performed: the first used an endpoint defined as the development of ESRD (eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, initiation of dialysis, or kidney transplantation), a doubling of serum creatinine (Scr) levels, or a 40% decline in eGFR within five years after the diagnostic renal biopsy; the second used an endpoint defined as the development of ESRD (eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, initiation of dialysis, or kidney transplantation), a doubling of Scr levels, or a 50% decline in eGFR within five years after the diagnostic renal biopsy to allow comparison with the International IgA Nephropathy Prediction Tool (IIgANPT). Model discrimination was assessed using the AUC.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and compared using t-tests (for normally distributed data) or Kruskal–Wallis tests (for non-normally distributed data). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and compared using chi-square tests. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS (v29.0, Mac) and R (v4.4.1).

Methods statements

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Characteristics of the clinical variables of studied participants

Each patient’s baseline was defined as the time of renal biopsy, which ranged from January 2014 to December 2017 in the dataset. The total follow-up period was 5 years following the renal biopsy. Within this cohort, 44 patients (6.1%) reached the endpoint event within 5 years after biopsy. Based on the occurrence of endpoint events, the 723 patients were divided into two groups: the endpoint events group and the non-endpoint events group. Thirty-one candidate predictors were considered, including demographics, clinical characteristics, and pathological features. Overall, patients undergoing renal biopsy were middle-aged, with a median age of 35 years, and predominantly female (58.0%). The median BMI was 22.66 kg/m2. Specifically, patients in the endpoint events group had higher values for age (mean 42.5 vs. 35 years), LDL (mean 2.92 mmol/L vs. 2.57 mmol/L), BUA (mean 365 μmol/L vs. 304 μmol/L), 24 h UTP (mean 2.40 g/24 h vs. 0.85 g/24 h), and HTN (86.4% vs. 34.5%) and lower Hb (mean 110 g/L vs. 121 g/L) and SA (mean 34.45 g/L vs. 38 g/L) compared to those without endpoint events. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Notably, patients with lower baseline eGFR stages were more likely to progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Specifically, 1.8% of patients in Group 1 (eGFR stage G4) progressed to ESKD, compared to 29.5% in Group 2. Similar trends were observed for renal C1q deposition, RPICI, FPE, and T. In addition, several predictors, including gender, BMI, TC, HDL, MH, serum immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgM), serum C3, serum C4, and renal IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, and C4 deposition, as well as the M, E, S, and C scores, showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups at baseline. The clinical characteristics of the endpoint event group and non-endpoint event group from the Hangzhou TCM Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University are summarized in Table 1.

The external validation cohort, comprising patients from Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital and Wenzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, had follow-up durations and variables consistent with the training and internal validation cohorts. The external cohort was predominantly composed of middle-aged individuals, with a median age of 37 years, and a majority of females (55.7%). The median BMI was 23.45 kg/m2, and 20 patients (5.7%) reached the endpoint event. The characteristics of the external validation cohort are presented in Table 1.

Model performance

A correlation analysis was performed on the included variables, revealing strong correlations between TC and LDL, SA and 24 h UTP, as well as RPICI and T. Based on prior research findings, TC, SA, and RPICI were excluded from further analysis. A correlation heat map of continuous variables (Fig. 2) showed significant correlations among several variables, with color depth representing the correlation coefficient. To address the potential impact of multicollinearity on the model, a LASSO Cox proportional hazards model was employed for variable selection. The top five selected variables were further analyzed for correlation and collinearity, and the results indicated no significant multicollinearity among them. These selected variables—Hb, 24 h UTP, HTN, eGFR, and Oxford classification T—were used to construct the XGBoost model for predicting the 5-year survival rate of patients with IgAN. Figure 4 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier curve showing the association of these variables with endpoint events. In the training set, the AUC of the XGBoost model was 0.951 (95% CI: 0.914–0.988), and in the internal validation set, it was 0.927 (95% CI: 0.877–0.978), indicating that the model did not exhibit overfitting. The Brier scores for the internal and external validation cohorts were 0.029 and 0.045, respectively. Both the Brier score and DCA confirmed the model’s good calibration and clinical applicability. External validation using data from patients with IgAN at Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital and Wenzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine showed an AUC of 0.913 (95% CI: 0.870–0.955), suggesting that the model demonstrates promising predictive performance and potential clinical utility. A more detailed presentation of the model’s performance is provided in Table 2, with the ROC curve and DCA displayed in Fig. 5.

KM survival curve of clinical variables selected by LASSO. (A) KM suvival curve of anemia status. (B) KM suvival curve of hypertension. (C) KM suvival curve of T. (D) KM suvival curve of 24 h UTP. (E) KM suvival curve of eGFR stage. Abbreviations: KM, Kaplan–Meier Curve; LASSO, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator; T, T in Oxford classification;eGFR stage, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate,according to the KDIGO CKD staging,1-G1, 2-G2, 3-G3, 4-G4; Urine protein,1-urine protein < 1 g/24 h, 2-1 g/24 h < = urine protein < 3 g/24 h, 3-urine protein > = 3 g/24 h

ROC curve and DCA curve of XGBoost model. (A) ROC curve and DCA curve of XGBoost model on the training set. (B) ROC curve and DCA curve of XGBoost model on the internal validation set. (C) ROC curve and DCA curve of XGBoost model on the external validation set. Abbreviations: DCA, decision curve analysis; XGBoost, Extreme Gradient Boosting.

Using the second endpoint definition—which included the development of ESRD, a doubling of serum creatinine levels, or a ≥ 50% decline in eGFR within five years—the external validation demonstrated that our XGBoost model achieved an AUC of 0.915 (95% CI: 0.870–0.961), whereas the IIgANPT showed an AUC of 0.715 (95% CI: 0.559–0.872). These findings indicate that our model exhibited superior discriminative performance compared with the IIgANPT in the external cohort.

Constructing a nomogram

Based on the variables selected by LASSO—Hb, 24 h UTP, HTN, eGFR, and Oxford classification T—a nomogram was developed to predict the 5-year renal survival probability for patients with IgAN. The nomogram calculates the total score by projecting the values of each variable onto the points axis and summing the scores. The total score is then mapped to the risk axis to estimate the patient’s 5-year survival probability (Fig. 6). For example, for a patient with IgAN exhibiting 24 h UTP of 4.51 g/24 h, Oxford classification T = 2, HTN = 1, eGFR = G4, and no anemia, the respective scores are approximately 43.5, 100, 52.6, 47.5, and 0. The total score is 243.6, which corresponds to a 5-year survival rate of about 13%, indicating a high risk of progression to ESRD. This suggests that the patient warrants close clinical monitoring. Clinicians should comprehensively assess the patient’s condition, develop an individualized treatment plan, and regularly monitor renal function and 24 h UTP.

Nomogram based on XGBoost model. The nomogram was constructed to estimate the 5-year renal survival probability in patients with IgAN. To utilize the nomogram, each predictor is located on its corresponding axis, and a vertical line is drawn upward to determine the number of points assigned. The total score is calculated by summing the individual points from all variables. This total score is then projected downward onto the probability scale to estimate the 5-year renal survival likelihood. Abbreviations: XGBoost, Extreme Gradient Boosting; T, T in Oxford classification; eGFR stage, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, according to the KDIGO CKD staging, 1-G1, 2-G2, 3-G3, 4-G4; Urine protein, 1-urine protein < 1 g/24 h, 2-1 g/24 h < = urine protein < 3 g/24 h, 3-urine protein > = 3 g/24 h; anemia, 0-without anemia, 1-with anemia; hypertension, 0-without hypertension, 1-with hypertension.

Discussion

This study developed an XGBoost model and a corresponding nomogram to predict the 5-year renal survival probability in patients with IgAN. The nomogram incorporated five readily available variables (anemia status, eGFR stage, HTN status, Oxford classification T score, and 24 h UTP) and demonstrated strong discriminatory performance and calibration in both internal and external validation cohorts. As a user-friendly tool, the nomogram enables primary care physicians to easily interpret the contribution and weight of each risk factor, thus facilitating more accurate and personalized risk assessment for patients with IgAN.

The IIgANPT is a widely used model that integrates clinical parameters and the Oxford MEST score to estimate the risk of a 50% decline in eGFR or progression to ESRD within 60 months. It includes two versions: one with and one without a race parameter10. In our study, we conducted two external validation analyses to compare the performance of our XGBoost model with the IIgANPT. Using the endpoint consistent with model development (ESRD, doubling of serum creatinine, or a ≥ 40% decline in eGFR), our model demonstrated robust predictive performance. To enable direct comparison with the IIgANPT, we redefined the external cohort endpoint as a ≥ 50% decline in eGFR, under which our XGBoost model achieved a substantially higher AUC of 0.915, indicating superior discriminative ability. Moreover, adopting a ≥ 40% eGFR decline as the primary endpoint allows our model to identify high-risk patients earlier than the IIgANPT, providing a longer window for clinical intervention and increasing sensitivity to early disease progression.Several other models have also been proposed. For instance, Zhang-Yu Tian et al. developed a prediction model based on five variables (n = 519)-LDL, Oxford S and T scores, cardiovascular disease, and 24 h UTP-to estimate the risk of initiating renal replacement therapy or reaching an eGFR < 15 mL·min−1·(1.73 m2)−1 at 5, 8, and 10 years11. Notably, this model includes only the M, E, S, and T scores of the Oxford classification, excluding the C score—a pathological feature that is closely associated with poor prognosis in Asian patients with IgAN—thereby potentially limiting the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the model’s prognostic assessment for this population.

With the advancement of ML, Yngvar Lunde Haaskjold et al. applied a random forest approach to data from Norwegian patients (n = 232) to identify predictive features and develop a risk prediction model. The selected predictors included T%, segmental glomerular sclerosis, normal glomeruli, global sclerotic glomeruli, segmental adherence, and perihilar glomerular sclerosis. While the model showed potential, it has not undergone rigorous external validation, and its clinical utility remains uncertain12.

To address these limitations, this study contributes novel insights to the existing literature by developing a prognostic model using multicenter data and conducting independent external validation, which confirmed the model’s strong discriminatory performance. The final model incorporated anemia status, eGFR stage, HTN status, the T score from the Oxford classification, and 24 h UTP. Among these variables, the Oxford T score, eGFR stage, and 24 h UTP align with KDIGO guidelines and are widely recognized as key prognostic indicators in IgAN. Early identification of CKD stages is clinically significant for risk stratification and the development of personalized intervention strategies, potentially delaying renal function deterioration and improving long-term outcomes and quality of life . Proteinuria is the most extensively studied risk factor for IgAN progression to ESRD, and recent reports have identified proteinuria reduction as a surrogate endpoint in IgAN trials13. Our study found that proteinuria levels > 1 g/24 h are a risk factor for poor prognosis, which is consistent with KDIGO recommendations that suggest targeting proteinuria < 1 g/24 h as a reasonable therapeutic goal13. A retrospective study by Heather N. Reich et al., which included follow-up data from 542 patients with IgAN, reported that those with persistent proteinuria > 3 g/day experienced a renal function decline rate 25 times faster than patients with proteinuria < 1 g/day14. However, after adjusting for time-dependent confounding factors, Chen Tang et al. observed that patients with proteinuria ≥ 0.5 g/24 h were still at an increased risk of kidney failure, highlighting the importance of controlling proteinuria in IgAN management, even at lower levels15. The prognostic significance of tubulointerstitial lesions has also been well established. A retrospective cohort study and meta-analysis by Bingxin Yu et al. confirmed that the presence of T lesions is a strong predictor of poor renal outcomes in IgAN, independent of all clinical and laboratory parameters16. Our findings support this conclusion. In the Oxford classification, the T score reflects the extent of tubulointerstitial injury. During the pathogenesis and progression of IgAN, the deposition of immune complexes-particularly IgA-in the tubulointerstitium activates local immune responses and triggers sustained inflammation, ultimately leading to interstitial fibrosis17. Therefore, a higher T score is associated with an increased risk of progression to ESRD and necessitates close clinical monitoring and targeted interventions.

In addition to the previously discussed indicators, anemia was identified as a strong and independent predictor of poor renal prognosis in patients with IgAN. Chronic kidney injury can contribute to anemia through several mechanisms, including reduced red blood cell survival, erythropoietin (EPO) deficiency, suppressed erythropoiesis, and iron dysregulation18,19,20,21,22,23. Anemia may further aggravate renal damage by inducing tissue hypoxia, potentially via activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signaling pathway, which plays a role in the progression of chronic kidney disease24,25. This mechanistic pathway helps explain the observed association between anemia and adverse renal outcomes in our cohort. A retrospective study by Tae Ryom Oh et al., involving 4,326 patients with biopsy-confirmed IgAN, found that for each 1.0 g/dL increase in Hb, the risk of disease progression decreased by 13%, aligning with our findings26. Renal anemia is driven by various mechanisms, including reduced red blood cell survival, EPO deficiency, suppressed erythropoiesis, and iron imbalance18,19,20,21,22,23. Among these, EPO deficiency and functional iron deficiency—both related to the HIF pathway—have attracted increasing attention for their roles in renal anemia and disease progression27. Furthermore, prior studies have documented a correlation between anemia and tubulointerstitial injury in IgAN, further underscoring its prognostic significance28,29. Our study further validates anemia as a risk factor for poor renal prognosis. Additionally, the importance of HTN in IgAN is reinforced. HTN at the time of renal biopsy has been linked to increased urinary protein excretion during follow-up, suggesting its ongoing impact on glomerular injury. Histopathological findings indicate that hypertensive patients typically exhibit more severe vascular lesions, which, compared to mesangial cell proliferation, play a more dominant role in glomerulosclerosis30. Therefore, in IgAN individuals with comorbid HTN, regular blood pressure monitoring and the use of antihypertensive medications during treatment are crucial for improving patient outcomes.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, event-per-variable (EPV) ratio of our study is relatively low, with 31 candidate predictors and 44 outcome events (EPV = 1.19), which may introduce some risk of overfitting and affect the stability of parameter estimates. In future studies, larger cohorts with more outcome events are needed to increase the EPV and improve the robustness and generalizability of the predictive model.Secondly, as a retrospective study, while multiple imputation using the “mi” package was applied to address missing data, residual bias cannot be entirely ruled out. Prospective studies with standardized and comprehensive data collection are necessary to validate these findings and minimize potential bias. Finally, this study focused solely on clinical and histopathological data, excluding genetic information. With the increasing accessibility of genomic sequencing technologies, integrating clinical and genetic data may provide additional value in improving risk prediction, diagnosis, and prognostication in IgAN, and should be explored in future research.

Conclusion

Using real-world data and a data-driven approach, this study developed a 5-year survival prediction model for IgAN utilizing the XGBoost ML algorithm. The model incorporates five routinely available clinical variables at the time of renal biopsy and demonstrated promising predictive performance in both internal and external validation cohorts. Moreover, when compared with the widely used IIgANPT, our model achieved higher discriminative efficiency and, by adopting a ≥ 40% decline in eGFR as the primary endpoint, was able to identify high-risk patients at an earlier stage, providing a longer window for clinical intervention and greater sensitivity to early disease progression. An intuitive nomogram derived from the model enables individualized risk assessment at diagnosis, helping primary care physicians recognize high-risk individuals, optimize follow-up strategies, and guide early, personalized management. By facilitating timely risk stratification and supporting evidence-based decision-making, this model may contribute to more precise, proactive, and resource-efficient care in IgAN, ultimately improving long-term outcomes. Further multicenter, prospective studies are warranted to validate its generalizability and support its integration into routine clinical practice.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Floege, J. Primary glomerulonephritis: A review of important recent discoveries. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 32(3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.krcp.2013.06.004 (2013).

D’Amico, G. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy: Role of clinical and histological prognostic factors. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 36(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2000.8966 (2000).

Noda, R., Ichikawa, D. & Shibagaki, Y. Machine learning-based diagnostic prediction of IgA nephropathy: Model development and validation study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 12426. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63339-7 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Tang, W., Yuan, X. & Xie, X. Development and internal and external validation of a nomogram model for predicting the risk of chronic kidney disease progression in IgA nephropathy patients. PeerJ 30(12), e18416. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.18416 (2024).

Luo, H. L., Zhang, H. N., Wei, W., Chen, C., Tang, K. N., Cui, X.N. Application of low-dose chest CT in predicting the grading of anemia severity. Lin Chuang Fang She Xue Za ZHi. 44(06):1015–1020.https://doi.org/10.13437/j.cnki.jcr.2025.06.004 (2025).

Levey, A. S., de Jong, P. E., Coresh, J., et al. The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference report [published correction appears in Kidney Int. 2011 Nov;80(9):1000]. Kidney Int. 80(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2010.483 (2011).

Trimarchi, H., Barratt, J., Cattran, D. C., et al. IgAN classification working group of the international IgA nephropathy network and the renal pathology society; conference participants. Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA Nephropathy Classification Working Group. Kidney Int. 91(5):1014–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.003 (2017).

Peng, Y. C. et al. Long-term prognosis of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 60(9), 894–900. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20220228-00161 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Plasma soluble urokinase receptor level is correlated with podocytes damage in patients with IgA nephropathy. PLoS ONE 10(7), e0132869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132869 (2015).

Hu, L. et al. External Validation of the International Prognosis Prediction Model of IgA Nephropathy. Ren. Fail. 46(1), 2313174. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022X.2024.2313174 (2024).

Tian, Z. Y. et al. Prognostic value of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in IgA nephropathy and establishment of nomogram model. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 10(14), 1037773. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1037773 (2023).

Haaskjold, Y. L. et al. Long-term follow-up of IgA nephropathy: Clinicopathological features and predictors of outcomes. Clin. Kidney J. 16(12), 2514–2522. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfad154 (2023).

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 99(3S):S1-S87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.11.003 (2021).

Reich, H. N.*; Troyanov, Ste[Combining Acute Accent]phan†; Scholey, J. W.*; Cattran, D. C.* for the Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry. Remission of Proteinuria Improves Prognosis in IgA Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18(12):3177–3183.https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2007050526.

Tang, C. et al. Time-varying proteinuria and progression of IgA nephropathy: A cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 84(2), 170-178.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.12.016 (2024).

Bingxin, Yu. et al. Evaluation of the Oxford classification in immunoglobulin A vasculitis with nephritis: A cohort study and meta-analysis. Clin. Kidney J. 14(2), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfaa129 (2021).

Suzuki, H. & Novak, J. IgA nephropathy: Significance of IgA1-containing immune complexes in clinical settings. J. Clin. Med. 13, 4495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154495 (2024).

Eschbach, J. W. et al. Erythropoiesis in patients with renal failure undergoing chronic dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 276, 653–658. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196703232761202 (1967).

Vos, F. E. et al. Red blood cell survival in long-term dialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 58(4), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.031 (2011).

Sahay, M. et al. Diabetes and Anemia: International diabetes federation (IDF) - Southeast Asian Region (SEAR) position statement. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 11(Suppl 2), S685–S695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2017.04.026 (2017).

Eschbach, J. W. The anemia of chronic renal failure: Pathophysiology and the effects of recombinant erythropoietin. Kidney Int. 35, 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1989.18 (1989).

MacDougall, I. C. et al. A randomized controlled study of iron supplementation in patients treated with erythropoietin. Kidney Int. 50, 1694–1699. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1996.487 (1996).

Babitt, J. L. & Lin, H. Y. Molecular mechanisms of hepcidin regulation: Implications for the Anemia of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 55, 726–741. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.030 (2010).

Schödel, J. & Ratcliffe, P. J. Mechanisms of hypoxia signalling: New implications for nephrology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0182-z (2019).

Ito, M. et al. Prolyl hydroxylase inhibition protects the kidneys from ischemia via upregulation of glycogen storage. Kidney Int. 97, 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.10.020 (2020).

Oh, T. R., Song, S. H., Choi, H. S., Kim, C. S., Han, S. H., Kang, K. P., Kwon, Y. J., Kim, S. W., Ma, S. K., Bae, E. H., on behalf of the Korean GlomeruloNEphritis sTudy (KoGNET) Group. The Association between Serum Hemoglobin and Renal Prognosis of IgA Nephropathy. J. Clin. Med. 10:363. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10020363 (2021).

Gupta, N. & Wish, J. B. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors: A potential new treatment for anemia in patients with CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 69, 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.011 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Clinical and pathological factors of renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy in Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9, e023479. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023479 (2019).

Zhu, B. et al. The association of low hemoglobin levels with IgA nephropathy progression: A two-center cohort study of 1828 cases. Am. J. Nephrol. 51, 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508770 (2020).

Ikee, R. et al. Impact of hypertension and hypertension-related vascular lesions in IgA nephropathy. Hypertens Res. 29(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.29.15 (2006).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82205008), the Zhejiang Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Project (No. 2023ZF137), the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Health Project (No. 2023RC242),the Research Project of the Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation (No. LQ24H180007),and the Joint TCM Science & Technology Projects of National Demonstration Zones for Comprehensive TCM Reform(No.GZY-KJS-ZJ-2026–090) .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jinjin Wang:Data Curation,Methodology,Visualization,Writing-Original Draft; Tianmu Chen:Methodology,Software,Formal analysis,Supervision; Yan Fu:Data Curation,Investigation; Tianqi Zhu:Data Curation,Investigation; Yaning Feng:Data Curation,Resources; Yuxi Feng:Investigation;Junwei Huang:Investigation; Xuan Zhang:Investigation;Junwei Huang:Investigation; Yi Cai:Data Curation; Li Gao:Data Curation; Yongqiang Lin:Conceptualization,Writing-Review&Editing; Qinyang Jin:Data Curation,Writing-Review&Editing; Qin Zhu:Writing-Review&Editing,Supervision,Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (IRB number 2021KY045). Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tianmu Chen and Yan Fu are recognized as co-first authors.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Chen, T., Fu, Y. et al. Development and preliminary validation of a predictive model for IgA nephropathy progression. Sci Rep 16, 2486 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32280-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32280-8