Abstract

Fetal MRI provides high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging with superior soft tissue contrast, offering critical diagnostic insights that complement ultrasound, particularly in cases of suspected abnormalities. However, its interpretation remains labour-intensive and highly dependent on subspecialized radiological expertise, which limits accessibility and contributes to diagnostic delays. To address these challenges, we present the Fetal Assessment Suite (FetAS), a secure, web-based platform designed to streamline and standardize fetal MRI analysis. FetAS automates key tasks, including artifact detection, motion correction, segmentation of the fetal body, amniotic fluid, and placenta, as well as classification of fetal and placental position and orientation, using AI models developed to reduce reliance on expert radiologists. By consolidating these capabilities into a single, user-friendly interface, FetAS reduces the cognitive and time burden of interpretation, supports timely clinical decision-making, and promotes equitable access to care in regions without local expertise. In addition, FetAS enables research through standardized pipelines, facilitates data sharing, and provides a foundation for future advancements in maternal–fetal imaging. Collectively, these features establish FetAS as both a diagnostic tool and a platform for expanding high-quality prenatal care across diverse healthcare settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

Prenatal evaluation of fetal anatomy is typically performed with ultrasound according to guidelines from the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG)1. A screening fetal ultrasound examination is usually performed at 18 to 24 weeks of gestational age1. An additional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) examination may be performed if the initial ultrasound findings are inconclusive or if there is suspicion of potential abnormalities not sufficiently characterized by ultrasound2. MRI is a safe imaging modality without ionizing radiation, which has very high soft-tissue contrast, resulting in significantly better anatomical visualization compared to ultrasonography3. MRI can provide additional diagnostic information in up to 23% of cases when documenting fetal anomalies, significantly enhancing diagnostic accuracy4. MRI has, therefore, become an increasingly more widely used modality for fetal diagnostic decision making, facilitating treatment planning and prognostication.

Radiological reporting of fetal MRI requires highly subspecialized knowledge. Segmentation, classification, and quality assurance can be time-consuming. Specifically, segmentation involves the manual delineation of different anatomical structures, for biometric assessment, and can help diagnostic decision-making in certain conditions, such as fetal growth restriction (FGR). Classification tasks in fetal imaging can encompass a wide range of objectives, including the detection of fetal abnormalities, identification of biometric deviations indicative of pathology, and determination of fetal position, all of which are critical for accurate diagnosis and clinical decision-making. MRI is susceptible to different imaging artifacts, with maternal/fetal motion being the most common. Such artifacts can distort fetal anatomy and, thus, hinder diagnostic decision-making. Meshaka et al.5 provide a comprehensive review of these different tasks and how artificial intelligence (AI) can advantageously be used in such scenarios.

Related works

To address the challenges of manual fetal MRI analysis, numerous algorithms have been developed, targeting specific processes such as segmentation, classification, and quality assurance. However, these solutions often operate in isolation, addressing individual steps rather than providing an integrated analysis pipeline.

For segmentation tasks, most efforts have focused on the fetal brain, aiming to delineate brain structures for neurodevelopmental assessment6,7,8,9,10. In comparison, fewer studies have targeted segmentation of the entire fetal body, despite its importance for comprehensive biometric analysis11,12,13. Some works have pursued even more specific targets, such as segmenting individual fetal organs, such as the lungs14,15. Beyond fetal anatomy, research has focused on maternal tissues, particularly segmenting the placenta and amniotic fluid due to their relevance in assessing fetal growth and pregnancy health16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Classification tasks in fetal MRI cover a wider range of objectives. Many studies focus on abnormality prediction, such as detecting neurodevelopmental disorders in the fetal brain or diagnosing conditions affecting other fetal organs23,24,25. Less commonly, classification approaches have been applied to tasks such as fetal position and pose detection, which can support movement tracking and inform mode of delivery decisions26,27.

In terms of quality assurance, most existing methods have targeted motion correction, with many involving slice-to-volume registration and deep learning based methods28,29,30,31. However, there is comparatively limited research on detecting and correcting other artifacts that can arise in fetal MRI and impact diagnostic confidence32.

Despite these advancements, a clear gap remains in the literature: current research typically addresses only individual steps of the workflow rather than providing a fully integrated solution to streamline the entire fetal MRI analysis process. Moreover, existing approaches often overlook clinical accessibility and ease of use, which greatly limits their applicability in real-world healthcare settings.

Objectives

In response to these challenges, we propose the Fetal Assessment Suite (FetAS). This specialized software platform incorporates a range of developed AI methods to automate the processing and analysis of fetal MRI. FetAS currently performs several key tasks: (1) artifact detection, (2) motion correction, (3) segmentation of the fetal body, amniotic fluid, and placenta, and (4) classification of fetal and placental position and orientation. The software is deployed as a secure, user-friendly web-based platform, allowing clinicians and researchers to easily upload datasets and perform all necessary analyses within a single integrated environment. By streamlining fetal MRI analysis and improving workflow efficiency, FetAS aims to support clinical practice, particularly in settings with limited access to specialized fetal radiologists. Furthermore, FetAS can facilitate research by enabling collaboration and the development of large, curated dataset cohorts.

Methods

System architecture

The FetAS platform employs a modern web architecture to ensure responsive, scalable, and secure MRI data analysis (Fig. 1). The frontend leverages Vite33 React34 for rapid development cycles and optimized production builds, with a responsive user interface crafted using HeroUI35 components and Tailwind CSS36 that seamlessly adapts across all device form factors. This client-side application communicates with a robust Node.js37 and Express.js38 backend that manages RESTful API endpoints and handles user authentication through Passport.js39 middleware integrated with JSON Web Tokens40 (JWTs) for secure, stateless session management. A sophisticated queuing system is implemented to manage incoming analysis requests, ensuring data is processed sequentially and reliably to support smooth clinical workflows without bottlenecks.

Data persistence is achieved through multiple specialized storage solutions. User credentials and data metadata are securely stored in an encrypted MySQL41 database hosted on Amazon Relational Database Service42 (RDS), ensuring data integrity, redundancy, and compliance with security standards. All uploaded and processed imaging data, including DICOM43 files, are stored in Amazon S344, providing scalable, durable, and secure object storage for large medical datasets.

The entire system is deployed on Amazon Web Services (AWS) infrastructure, where the frontend is compiled and hosted on Amazon S3 with global content delivery through Amazon CloudFront45 for low-latency worldwide access. The backend services run on dedicated Amazon EC246 instances equipped with GPU acceleration, enabling efficient execution of integrated AI models for computationally intensive tasks such as image segmentation and classification. This distributed architecture ensures optimal performance while maintaining the security and reliability required for clinical applications.

The platform includes secure clinician login and user management, enabling authorized users to upload, process, share, and collaboratively review imaging data. Only authorized users are allowed to view datasets they have uploaded; otherwise, access is denied. Uploaded MRI data undergoes automated preprocessing, starting from automatic data deidentification, to ensure no personal health information is ever stored on the platform. This is followed by image normalization and histogram adjustments to standardize inputs for subsequent analyses and improve algorithm robustness. These processes are for algorithm performance; however, the original DICOMs are displayed to the user, unless replaced by motion correction, to ensure clinically relevant details are not lost. This system architecture design ensures high availability, security, and scalability, enabling deployment in both research and clinical environments.

The FetAS platform uses a layered security and access-control approach within AWS. All data is encrypted at rest and in transit using the AWS Key Management Service47 and Transport Layer Security. Storage is separated into Amazon S3 buckets for raw uploads, processed data, logs, and model files, with bucket policies that limit access by dataset and role. All components operate inside a Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) with public and private subnets, and traffic is controlled through security groups and network access control lists. Identity and Access Management (IAM) roles follow a least-privilege model for Amazon EC2, Amazon RDS, S3, and other services, and user permissions are assigned by role. Secrets and passwords are stored in AWS Secrets Manager48, and administrator accounts use Multi-Factor Authentication. Amazon RDS, MySQL, S3, and Redis are encrypted and deployed in private subnets, and system activity is recorded through Amazon CloudWatch, AWS CloudTrail49, and VPC Flow Logs.

Each process runs in a new batch environment with a clean Python runtime. Model files are stored in encrypted S3 but are preloaded onto encrypted Amazon Elastic Block Store50 volumes on the EC2 instance for inference. This keeps model access local to the instance and avoids cross-service data transfer during processing. Automatic RDS snapshots, S3 versioning, and defined recovery steps support data persistence.

Dataset and preprocessing

The core functions of FetAS are designed to process Half-Fourier Acquisition Single-shot Turbo spin Echo (HASTE) and Steady-State Free Precession (SSFP) sequences with SENSE, acquired on either 1.5T or 3.0T Siemens MRI scanners. These MRI datasets were obtained from The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. Data collection spanned between the years 2000 and 2024. This retrospective study was approved by The Hospital for Sick Children Research Ethics Board (REB #1000062640), the Toronto Metropolitan University Research Ethics Board (REB #2018 − 398), and Clinical Trials Ontario (REB #4861). Gestational ages spanned from 20 to 37 weeks. Extremely rare pathologies (1:100,000) were excluded from this study. All data extraction, utilization, and related methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of these REBs. Given the retrospective design and complete de-identification of all data, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick Children and the Research Ethics Board at Toronto Metropolitan University.

Each processing module was trained on a diverse subset of this dataset, with all annotations clinically validated. General preprocessing was applied to the raw DICOM files prior to model training. This included extracting pixel or voxel data, depending on whether the method used a 2D or 3D approach. Min-max normalization was applied to standardize intensities between 0 and 1. Additionally, data augmentation was performed on-the-fly during training to enhance model robustness and generalizability. A summary of the sample size for each task is shown in Table 1.

Main processes

FetAS allows users to easily complete one of many post-acquisition processing tasks on their uploaded datasets. The datasets and results from each process can be securely shared for collaborative work, with all data stored in S3 for future access. The following subsections briefly outline the methodology, functionality, and significance of each process. A summary of each task’s performance and methods is shown in Table 1.

Artifact detection

Degradation of fetal MRIs is most commonly caused by motion, chemical shift, and radiofrequency artifacts51. These artifacts can obscure parts of the fetus, making interpretation challenging for the radiologist. Currently, MRI operators have to manually review each MRI series to determine the presence of artifacts. Thus, the goal of this process was to automate this procedure, and provide a quick alert on whether the MRI was corrupted by artifacts (Fig. 2). This would significantly improve workflow efficiency, allowing clinicians to see more patients and helping to reduce the existing backlog. Although reacquisition is unlikely at this stage, the artifact detection module remains useful beyond its primary purpose. It provides insights into the type and severity of artifacts, which can assist researchers or clinicians who may be less familiar with the appearance of such distortions, thereby serving as a valuable teaching and training tool. In addition, it can contribute to dataset curation and standardization by allowing users to rapidly identify and flag artifact-corrupted images, facilitating the inclusion or exclusion of scans according to the specific objectives of a study or analysis pipeline.

The artifact detection algorithm makes use of a 2D convolution neural network (CNN) framework which incorporates skip connections, Inception blocks, and Squeeze and Excitation (SE) blocks that stem from the ResNet-50, Inception, and SE networks, respectively. The output gives the type of artifact detected as well as a corresponding 4-class severity grade (none, mild, medium, severe). A preliminary version of this algorithm has been developed and validated, as described in32.

Motion artifact correction

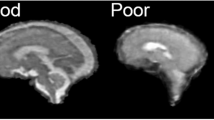

Among the various artifacts encountered in fetal MRI, motion is the most prominent and stems from either fetal or maternal movement. Although there exist motion artifact reduction techniques, which rely on implementing specific sequence types and/or utilizing patient dependent strategies, such as maternal breath-hold, there is no absolute guarantee that the corrected MRI will be motion-free. Thus, we have developed and implemented this process to automatically correct for motion artifacts, ensuring that radiologists can make accurate diagnoses with clear and interpretable anatomy (Fig. 3). Furthermore, by mitigating motion artifacts, this process reduces the need for repeat scans, thereby enhancing overall workflow efficiency.

v

To accomplish this, a 2D generative adversarial network (GAN) was developed and trained on image pairs, one with motion artifacts, and the other without. The motion artifacts were synthetically generated by modifying the frequency contents of its motion-free counterpart, introducing random translational and rotational variations to mimic the diverse and unpredictable nature of motion in fetal MRI, resulting in varying levels of artifact severity across the dataset. By training with these realistic simulated artifacts, the network was able to correct genuine motion artifacts in clinical MRIs during inference effectively. An initial implementation of this approach was proposed and evaluated in previous work31.

Anatomy segmentation

Biometrics like estimated fetal weight, amniotic fluid volume, and placental volume are key indicators of fetal growth, maternal health, and overall pregnancy well-being. These metrics help detect conditions such as FGR and amniotic fluid abnormalities, including oligohydramnios and polyhydramnios, while placental volume can reveal complications like preeclampsia and placental insufficiency. However, assessing these conditions currently requires manual segmentation, a process that is labour-intensive and requires specialized expertise. This process addresses these challenges by automatically, rapidly, and accurately segmenting fetal MRIs into three classes: fetal body, amniotic fluid, and placenta. These segmentations (Fig. 4) enable volume-based biometrics that can assist in the timely diagnosis of common abnormalities, ultimately improving pregnancy monitoring and outcomes.

A 3D UNet-based architecture was developed. Specific enhancements were made to improve segmentation quality such as spatial and channel attention mechanisms and Multi-Level Feature Extraction using dilated convolutions. This encoder-decoder network takes a fetal MRI volume as input, down-samples and then up-samples it to generate a segmentation mask for the fetal body, amniotic fluid, and placenta. This methodology builds upon an early version that was introduced and validated in previous work52. Although not required, utilizing the motion correction process prior to segmentation is recommended as this has been shown to improve segmentation quality, and therefore biometric estimation accuracy, in prior research53.

Fetal body and placenta classification

Anatomical position assessment is essential for pregnancy management. For example, fetal presentation can be classified as vertex (head-down), breech (buttocks or feet-down), or transverse (lying sideways), each carrying different delivery implications and potential risks. Similarly, accurate determination of placental location is required, particularly for identifying placenta previa, where the placenta partially or completely covers the cervical os, increasing the risk of bleeding and complications during delivery. While these position assessments are commonly done using ultrasound, they still need to be determined as part of a fetal MRI radiological assessment to ensure the radiological report is complete. Thus, in the absence of expertise in fetal MRI, these too need to be evaluated. Therefore, we developed these processes to automate the detection of fetal presentation (Fig. 5) and placental position (Fig. 6) in MRI, which can assist in timely clinical decision-making, support treatment planning, and improve maternal-fetal outcomes.

To achieve this, 2D CNNs were utilized. For fetal orientation, we use an average prediction, two slice-based classification models. We then take a majority vote across the entire 3D array to classify fetal orientation. For placental previa classification, there are two sequential CNNs, the first of which classifies if an image contains the placenta in view, which then feeds to the placenta previa classification model. An extensive analysis, featuring an ablation study and a detailed comparison to other models, was performed and published in our prior work26,54.

Performance evaluation

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the FetAS platform, focusing on processing performance and specific metrics. Specifically, processing time was evaluated through log streams timestamping the initial and final requests the server produced for a given task. CPU and memory usage are calculated through the htop Linux command55, providing the average CPU and memory increase a process produces once queued. GPU usage was calculated through the nvidia-smi56 command. Test datasets consisted of fetal MRI scans with sequences described in the Dataset and Preprocessing section. To distinguish between dataset size, we included a small dataset of 512 × 512 T2 fetal MRI containing 60 slices with a total size of 30.1 MB. The modules evaluated in the small dataset included artifact detection, motion correction, multi-organ segmentation and uploading a dataset. For artifact detection, motion correction, and multi-organ segmentation, we utilized a 512 × 512 T2 fetal MRI dataset with 104 slices for the large dataset, resulting in a final size of 52.3 MB. To benchmark the dataset upload process, the large dataset was changed to reflect an entire study with multiple sequences, resulting in 1,353 MRI files totalling 966 MB. The upload metrics were 119 MB/s with a latency of 23 ms.

All evaluations were conducted on the deployed backend Amazon EC2 G4dn 2xlarge instance, which is equipped with an NVIDIA T4 GPU, 16 GiB of GPU memory, 64 GiB of memory, eight virtual CPU cores running 2.5 GHz Cascade Lake 24 C processors, and one 225 GB NVMe SSD. The total network throughput has a baseline of 10 GB/s with a burst of up to 25 GB/s.

Results

Platform interface and workflow demonstration

The following subsections show an end-to-end working demonstration of FetAS from a user’s standpoint. This includes logging in, an overview of the homepage, dataset details, dataset loading, dataset processing, and result visualization. For this work, we define a “process” as a collection of functions encompassing an anatomical region (e.g. Fetal Body), or combined use of anatomical regions (e.g. Relative Measures). A “subprocess” (or “Operation”) includes a specific function that uses an MRI dataset (e.g. Segmentation, Biometric Evaluation).

Login

Upon entering the landing page and clicking on “Authorized Login”, the user is prompted to log in with their email and password (Fig. 7). Accounts are created by the website administrator or the “Clinician” user role.

Homepage

The homepage is the first page displayed after logging in (Fig. 8). This page provides the user with the dashboard: a page of the processes and datasets that are currently stored for the user. A top navigation bar is provided to access all the relevant components of the website, alongside user-specific information.

Homepage of FetAS. The navigation bar presents the user with redirecting tabs to the (a) dashboard, (b) dataset, (c) processes, (d) clinicians, and (e) sites. The username and role (f) are displayed on the navbar, offering options on click to view your account, access website information, toggle dark mode, submit support tickets, and log out.

Dataset details

In the datasets page, users are provided with a list of all currently uploaded datasets (Fig. 9). This page is intended to create, view, edit, and delete any datasets stored within the website. To facilitate this function, we include a list of columns with headers that can be sorted either alphabetically or chronologically: the assigned ID given by our database, the user specified name of the dataset, the time at which the dataset was created, the gestational age of the fetus, the sex of the fetus, whether the dataset was motion corrected, the acquisition plane of the dataset, and action buttons to view, edit, download or delete the dataset. Users can modify which columns appear within the datasets page for ease of access.

When a user navigates to view the dataset by pressing on the blue folder button in the actions column, they are shown the “View Dataset” page (Fig. 10). This page provides a detailed breakdown of the column fields previously shown in the “Datasets” page, along with a list of processes the user has performed with this dataset. The user can also download the specified dataset as a compressed folder. The folder contains a root dataset folder with a subfolder for the dataset ID, which in turn contains two subfolders: dcm holding the DICOM files, and result holding the process’s results.

The datasets page, which includes a sortable table of datasets stored in the user’s FetAS account. At the top left of the table, users can create new datasets (a). Within the table, columns can be hidden or displayed under the “Columns Options” tab (b). Actionable buttons (c) include the blue folder to view the dataset (Fig. 10), and the triple dotted dropdown to edit, download, or delete the respective dataset.

View dataset page. Dataset information is shown on the left, and a list of associated processes is shown to its right (a). If a user presses on one of the processes, they are navigated to the “View Process” page. A cropped version of the “View Process” page (b) is shown, demonstrating the fetal body biometric results.

Loading dataset

After selecting to create a dataset on the “Datasets” page, the user is presented with a stepper-style progress bar that indicates what part of the dataset creation process they are in. Figure 11 demonstrates the first step of this task: filling out the required fields describing the dataset. Next, users are prompted to upload their dataset by navigating their local file explorer or by dragging and dropping selected files (Fig. 12). The various deep learning models were and will be trained on different types of fetal MRI sequences; therefore, model selection must align with the sequence type being analyzed. For instance, our segmentation models trained on SSFP with SENSE T2-weighted sequences should only be applied to SSFP with SENSE T2 data. Users are expected to choose the appropriate model corresponding to the sequence type present in their uploaded dataset. This is shown in Fig. 13, where the series description metadata is displayed to the user for ease of sequence selection. The fourth and fifth steps for uploading a dataset involve running the “Artifact Detection” and “Motion Correction” algorithms. These can be skipped and applied later in the “Processes” page; as such, we will cover them in the next section.

Processing data

After uploading a dataset, a user can begin a new process by navigating to the “Processes” page (Fig. 14). This page, similar to the “Datasets” page, contains a table with filterable column fields. The fields are described in the following order: dataset name, process type, subprocess type, process status, last modification time, and actions for viewing or deleting the process. Notably, a queuing system is used to handle a large number of user requests, so demonstrating the status of a process is essential for ease of use.

When a new process is selected, the platform’s currently available processes are displayed (Fig. 15). In order, they are: Amniotic Fluid, Placenta, Fetal Body, Multi-Organ (or Multi-Region) and Relative Measures. Each process outlines the number of subprocesses (or tools) available. With a process selected, a user can choose a subprocess and the corresponding dataset(s) to be queued at once. Specific subprocesses have dependencies on other processes being performed; for example, to perform fetal biometrics, the fetal body or multi-region segmentation subprocesses must first be performed. If a subprocess has a dependency, it is shown to the user as a dependency to be performed first, with the subprocess greyed out.

The processes page outlines a table of processes the user has. At the top left of the table, users can create new datasets (a). The status column (b) describes the process as either queued, executing, or currently in use (as a dependency). The status and last updated columns can be hidden from view using the “Columns Options” button (c). The actions column gives two buttons to either view or delete the process while it is being completed (d).

Visualization of processed outputs

(a) Artifact Detection Output & Motion Correction.

The artifact detection process is available after sequence selection to facilitate the detection of any low-quality image. If a user proceeds with artifact detection, a fetal body segmentation will be performed first and displayed to the user before running the artifact detection (Fig. 16. a). This provides feedback in case there are any errors during either process. Once artifact detection is complete, three pie charts will be displayed corresponding to the type of artifact. The pie charts are then sub-categorized by None, Mild, Medium or Severe types of artifacts explained in Lim et al.32. In Fig. 16, the fetal MRI shows a large proportion of slices being Severe for all three artifact classifications. Hovering over a sub-classification, users are shown the exact number of slices in such a sub-classification. If a user uploads an image with severe motion artifacts, the motion correction option is provided as the following step. This step runs the motion correction algorithm31, allowing the user to compare the motion-corrected dataset with the original dataset (Fig. 17). Due to the generative nature of this process, a user can regenerate, confirm or discard any changes to the motion-corrected dataset.

Both motion correction and artifact detection are optional processes to ensure a streamlined method of using the application. Artifact detection and motion correction are included before any further processing if a user wants to perform motion correction on an already highly motion-corrupted image. In this way, users are prompted to perform preprocessing before they are shown the complete list of processes to take advantage of a higher-quality dataset.

The Artifact Detection step. A cropped page demonstrating the transition between running (a) and finalizing artifact detection (b) is shown as cropped fields. The classification results are displayed as pie charts once the process is complete. From left to right, the classifications are motion artifacts (c), radio frequency (d) and chemical shift (e).

The Motion Correction step. Comparison of the original SSFP with SENSE fetal MRI, along with its motion-corrected output, is shown. The side-by-side images are slightly zoomed in for clarity. Users have three available buttons from left to right: regenerate results (grey), discard results (red) and accept uploaded images (green).

(b) Segmentation Output.

The segmentation subprocess is an integral part of FetAS. Currently, we provide 2D or 3D-based segmentation models. For amniotic fluid, placenta, and fetal body processes, the segmentation models available are 2D slice-based models11,16, which are effective in datasets with a low number of slices, as they avoid slice-wise downsampling loss, unlike 3D models that ensure image shape consistency across all three dimensions. However, for Multi-Organ segmentation, we implemented a 3D-based model that outperforms the 2D approach when given a sufficiently large 3D MRI (e.g., 256 × 256 × 64). Once segmentation is performed, the user can view their segmentations through a scroll-based panel, where the dataset, segmentation and resulting masked dataset are synchronized (Fig. 18).

Cropped visualization of the “View Process” page when the Multi-Organ Segmentation processes and subprocesses are selected. A fetal SSFP sequence with SENSE is demonstrated above (a) with its placenta (white), amniotic fluid (grey) and fetal body (dark grey) segmentation labels (b), and the corresponding mask of the original DICOM (c).

(c) Classification Output.

Current classification subprocesses involve placenta previa and fetal orientation classification26. An example output of fetal orientation classification is seen in Fig. 19. These subprocesses are available through the Fetal Body and Placenta processes, respectively. For fetal body orientation, the classification is performed by calculating the majority vote of the three classifications: vertex, breech or transverse. If all slices are classified as unknown, then the classification of unknown is applied. For placenta previa detection, the algorithm identifies placenta-relevant slices and feeds them into another model to classify the placenta as previa or not (Fig. 20). To ensure transparency in our models, we plan to provide model confidence for all classifications, along with the slice index for visual confirmation if needed.

The classification result of fetal orientation is shown in the “View Process” page. For the fetal MRI shown in Fig. 18, the fetal orientation subprocess displays its classification as in the vertex orientation.

The classification results for the placenta previa model are shown on the “View Process” page. A slice from the fetal MRI used for this process is shown in the figure. The current implementation generates a JSON output format (prototype), where the average probability as a whole, probability per slice and index are shown. The user interface for this system is under development to be user-friendly.

Processing performance

Table 2 presents the processing performance metrics of FetAS, based on evaluations using representative test datasets. We tested a range of tasks, including a 2D classification ensemble model for artifact detection, a generative model for motion correction, and a 3D segmentation model for multi-organ segmentation, to assess overall system performance. Average processing time across tasks was approximately 20 s, excluding the network-dependent data upload step. CPU usage was generally similar for small and large datasets, except during data upload and 3D segmentation. In the upload step, the EC2 instance parsed a significantly greater number of files before transferring them to the S3 bucket, increasing CPU load. In 3D segmentation, CPU usage was elevated due to preprocessing operations that scale with dataset size. GPU usage remained consistent across tasks because the deep learning architectures used in FetAS constrained the input size and model parameters to a fixed configuration, with the CPU performing any necessary preprocessing to meet these constraints. Finally, memory usage increased with dataset size across all tasks, reflecting the greater computational demands of processing larger inputs.

Discussion

Principal findings

In this study, we presented FetAS, a novel web-based platform integrating multiple automated analysis processes for fetal MRI, including artifact detection, motion correction, multi-anatomical segmentation, and classification of fetal and placental position. The results demonstrate that FetAS provides a seamless, end-to-end workflow, enabling clinicians and researchers to securely upload datasets, process them through an integrated pipeline, visualize outputs, and export results within a single user-friendly environment. Processing performance evaluations showed that all modules operated within feasible runtime ranges, and maximum capability testing confirmed FetAS’s robustness in handling clinically relevant dataset sizes and multiple concurrent requests.

The process design is intended to support future iterations of subprocesses that encompass a wide range of maternal and fetal anatomy and functions related to these regions. This is also similar to how a radiologist could categorize diseases; for example, our amniotic fluid process includes segmentation as a subprocess. When selecting this subprocess, a clinician must choose a dataset to use, with the option to queue multiple datasets simultaneously. Once completed, the subprocess for biometric evaluation can be processed, which currently only provides a clinician with the total amniotic fluid volume; however, classifying AF disorder can be incorporated. This exemplifies the modularity of our application, where if a clinician finds a specific use case with the original fetal MRI, segmentation, classification or metrics extracted, they can facilitate the research and implementation of it.

Our performance results demonstrate what a user can currently expect when testing FetAS with their datasets. The EC2 instance can handle any process at a time, and with a first-in, first-out queuing system, we ensure there are no bottlenecks when multiple concurrent users use it. Additionally, this enables us to scale up our resources based on demand; thus, the performance metrics listed in Table 2 are not fixed measures. Overall, these results provide a clear baseline for iterative development to improve upon.

Comparison with prior work

Previous efforts in fetal MRI analysis have focused predominantly on isolated algorithmic tasks, such as segmentation of the fetal body or placenta, motion correction methods, or artifact detection algorithms implemented as standalone scripts or research pipelines. While these developments have advanced the field, their integration into routine clinical workflows remains limited due to barriers in usability, accessibility, and the need for technical expertise to deploy and operate them.

In contrast, FetAS provides a comprehensive platform that bridges this translational gap by incorporating multiple validated AI methods within an accessible web-based interface. To our knowledge, FetAS is among the first platforms to integrate artifact detection, motion correction, anatomical segmentation, and classification tasks specific to fetal imaging into a unified tool accessible via standard browsers without the need for local installation or specialized computational infrastructure. Similar software has been developed in other domains, such as the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) for brain MRI analysis57. Another example is 3D Slicer paired with plug-ins, such as DeepInfer, which enables AI model deployment and visualization across multiple imaging modalities58. These platforms are widely used and demonstrate the potential of integrated, user-friendly software to advance clinical research in medical imaging. However, most of these platforms rely on local computing resources, which are typically unavailable in clinical environments. Comprehensive, accessible solutions remain particularly rare in the context of fetal MRI, demonstrating the unique value of FetAS. Unlike these traditional tools, FetAS is fully web-based, eliminating the hardware and software constraints associated with local installation and enabling broader, more seamless adoption in both clinical and research settings.

Clinical and research implications

The development of FetAS has several important clinical and research implications. First, in terms of clinical workflow efficiency, FetAS automates time-intensive tasks such as segmentation and motion correction. This automation has the potential to reduce reporting times, facilitate more timely diagnoses, and facilitate radiological decision-making, particularly in clinical settings with limited subspecialty expertise. FetAS can help extend high-quality diagnostic support, enabling more equitable access to care in rural or remote areas where dedicated radiological expertise may be unavailable. Second, the integration of artifact detection and motion correction modules improves the quality of input data for subsequent analyses. This improvement has the potential to increase diagnostic confidence and accuracy, particularly in the assessment of fetal growth and rare anomalies. Third, FetAS offers a standardized pipeline for the analysis of fetal MRI datasets, which can significantly benefit research efforts. By enabling the creation of large, curated cohorts, the platform supports future AI development, population-based studies, and the discovery of novel imaging biomarkers.

Limitations & future work

The current evaluation of FetAS showcases the current workflow capabilities that a radiologist can expect to be automated. Performance metrics for these algorithms have been published or are under review in prior work11,16,25,26,31,32,53,54. Platform performance is currently limited by cloud resources, particularly GPU instances for ultra-high-resolution datasets. Integrating AI into clinical workflows also poses challenges, requiring clear communication with radiologists and staff about software capabilities and limitations. Although preliminary internal user testing has been conducted, formal usability and workflow impact studies are still underway via a multi-center clinical study across Ontario (CTO #4861). This study will also expand the platform’s generalizability across sequences and scanners.

Ongoing work at the Maternal Fetal Imaging Lab includes integrating a 3D visualization tool and supporting multimodal data fusion (e.g., ultrasound, electronic health records), leveraging the software’s modular design. The ability of the current data uploading scheme, by which clinical MRIs are uploaded from a local filesystem onto our secure cloud storage, can be limiting. In busy clinical scenarios, local filesystem uploading can be impractical. Therefore, integration with hospital database software would streamline this process, making it an essential consideration for future updates. These enhancements will establish FetAS as a scalable, comprehensive platform for maternal–fetal diagnostics and clinical research.

FetAS implements comprehensive data security measures, including encryption in transit and at rest, network and storage segregation, least-privilege IAM roles, and automatic de-identification of all personal health information before upload. The application is compliant with local regulatory approval for research environments. As such, access to the platform is currently granted for research purposes upon obtaining the necessary inter-institutional and ethics approvals. The validation of this work in a clinical setting is currently underway, with clinical implementation as the end goal.

Conclusion

FetAS promises to address current challenges towards translating fetal MRI analysis methods into routine clinical and research workflows. By integrating multiple automated processes within an accessible, secure, and user-friendly platform, FetAS can improve the limited availability of specialized fetal radiologists and the resulting backlog in imaging interpretation. Through the automation of time-consuming tasks such as artifact detection, motion correction, segmentation, and classification, FetAS can reduce processing and reporting times, thereby enhancing diagnostic efficiency, improving clinical workflows, and enabling timely decision-making in fetal care. Ultimately, FetAS is designed to equalize access to high-quality fetal MRI diagnostics by enabling use in regions with limited radiological expertise, while also serving as a triaging tool in centers with established radiology services. By providing a consistent analytical pipeline, FetAS facilitates large-scale research, supports data sharing, and promotes the development of future AI tools. Its modular design also enables training and education, empowering clinicians, trainees, and researchers to contribute to advancing maternal–fetal imaging across both clinical and academic settings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to legal restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request of a data sharing agreement. FetAS is currently available at https://fetas.mfi-lab.ca/ with access being granted upon request.

References

Salomon, L. J. et al. ISUOG practice guidelines (updated): performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59, 840–856 (2022).

Prayer, D. et al. ISUOG practice guidelines (updated): performance of fetal magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 278–287 (2023).

Saleem, S. N. & Fetal, M. R. I. An approach to practice: A review. J. Adv. Res. 5, 507–523 (2014).

Levine, D. Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging in fetal evaluation. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 12, 25–38 (2001).

Meshaka, R., Gaunt, T. & Shelmerdine, S. C. Artificial intelligence applied to fetal MRI: A scoping review of current research. Br. J. Radiol. 20211205 https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20211205 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Semi-automatic segmentation of the fetal brain from magnetic resonance imaging. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1027084 (2022).

Khalili, N. et al. Automatic extraction of the intracranial volume in fetal and neonatal MR scans using convolutional neural networks. NeuroImage Clin. 24, 102061 (2019).

Ebner, M. et al. An automated framework for localization, segmentation and super-resolution reconstruction of fetal brain MRI. NeuroImage 206, 116324 (2020).

Comte, V. et al. Unsupervised Segmentation of Fetal Brain MRI using Deep Learning Cascaded Registration. Preprint at (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2307.03579

Caballo, M., Pangallo, D. R., Mann, R. M. & Sechopoulos, I. Deep learning-based segmentation of breast masses in dedicated breast CT imaging: radiomic feature stability between radiologists and artificial intelligence. Comput. Biol. Med. 118, 103629 (2020).

Lo, J. et al. Cross attention squeeze excitation network (CASE-Net) for whole body fetal MRI segmentation. Sensors 21, 4490 (2021).

Specktor-Fadida, B. et al. Deep learning–based segmentation of whole-body fetal MRI and fetal weight estimation: assessing performance, repeatability, and reproducibility. Eur. Radiol. 34, 2072–2083 (2023).

Ryd, D., Nilsson, A., Heiberg, E. & Hedström, E. Automatic segmentation of the fetus in 3D magnetic resonance images using deep learning: accurate and fast fetal volume quantification for clinical use. Pediatr. Cardiol. 44, 1311–1318 (2023).

Uus, A. U. et al. Automated body organ segmentation, volumetry and population-averaged atlas for 3D motion-corrected T2-weighted fetal body MRI. Sci. Rep. 14, 6637 (2024).

Conte, L. et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: automatic lung and liver MRI segmentation with nnU-Net, reproducibility of pyradiomics features, and a machine learning application for the classification of liver herniation. Eur. J. Pediatr. 183, 2285–2300 (2024).

Costanzo, A., Ertl-Wagner, B. & Sussman, D. AFNet algorithm for automatic amniotic fluid segmentation from fetal MRI. Bioengineering 10, 783 (2023).

Csillag, D. et al. AmnioML: Amniotic Fluid Segmentation and Volume Prediction with Uncertainty Quantification. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 37, 15494–15502 (2023).

Alkhadrawi, A. M. et al. Adaptive resolution attention network for precise MRI-Based segmentation and quantification of fetal size and amniotic fluid volume. J. Imaging Inf. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-025-01556-w (2025). ARANet.

Han, M. et al. Automatic segmentation of human placenta images with U-Net. IEEE Access. 7, 180083–180092 (2019).

Pietsch, M. et al. Automatic prediction of placental health via U-net segmentation and statistical evaluation. Med. Image Anal. 72, 102145 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Deep-learning based segmentation of the placenta and uterine cavity on prenatal MR images. In Medical Imaging 2023: Computer-Aided Diagnosis Vol. 21 (eds Iftekharuddin, K. M., Chen, W. et al.) (SPIE, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2653659.

Li, J. et al. Placenta segmentation in magnetic resonance imaging: addressing position and shape of uncertainty and blurred placenta boundary. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 88, 105680 (2024).

Attallah, O., Sharkas, M. A. & Gadelkarim, H. Fetal brain abnormality classification from MRI images of different gestational age. Brain Sci. 9, 231 (2019).

Shinde, K. & Thakare, A. Deep Hybrid Learning Method for Classification of Fetal Brain Abnormalities. in 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Vision (AIMV) 1–6IEEE, Gandhinagar, India, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/AIMV53313.2021.9670994

Lo, J., Lim, A., Wagner, M. W., Ertl-Wagner, B. & Sussman, D. Fetal organ anomaly classification network for identifying organ anomalies in fetal MRI. Front. Artif. Intell. 5, 832485 (2022).

Eisenstat, J., Wagner, M. W., Vidarsson, L., Ertl-Wagner, B. & Sussman, D. Fet-Net algorithm for automatic detection of fetal orientation in fetal MRI. Bioengineering 10, 140 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Fetal pose Estimation in volumetric MRI using a 3D Convolution neural network. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2019 Vol. 11767 (eds Shen, D. et al.) 403–410 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Sobotka, D. et al. Motion correction and volumetric reconstruction for fetal functional magnetic resonance imaging data. NeuroImage 255, 119213 (2022).

Uus, A. et al. Deformable Slice-to-Volume registration for motion correction of fetal body and placenta MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 39, 2750–2759 (2020).

Uus, A. U. et al. Automated 3D reconstruction of the fetal thorax in the standard atlas space from motion-corrupted MRI stacks for 21–36 weeks GA range. Med. Image Anal. 80, 102484 (2022).

Lim, A., Lo, J., Wagner, M. W., Ertl-Wagner, B. & Sussman, D. Motion artifact correction in fetal MRI based on a generative adversarial network method. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 81, 104484 (2023).

Lim, A., Lo, J., Wagner, M. W., Ertl-Wagner, B. & Sussman, D. Automatic artifact detection algorithm in fetal MRI. Front. Artif. Intell. 5, 861791 (2022).

VoidZero Inc. and Vite contributors. Vite.

Platforms, M. Inc. React.

NextUI & Inc HeroUI.

Tailwind Labs Inc. Tailwind CSS.

OpenJS Foundation. Node.js.

OpenJS Foundation. Express.js.

Jared Hanson. Passport.js.

Jones, M., Bradley, J. & Sakimura, N. JSON Web Token (JWT). RFC7519 https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7519 (2015). https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC7519

Oracle MySQL.

Amazon Web Services, Inc. Amazon Relational Database Service.

National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) Standard. (2024).

Amazon Web Services, Inc. Amazon S3.

Amazon, W. Services, Inc. Amazon CloudFront.

Amazon Web Services, Inc. Amazon EC2.

Amazon Web Services, Inc. AWS Key Management Service.

Amazon Web Services, Inc. AWS Secrets Manager.

Amazon, W. Services, Inc. AWS CloudTrail.

Amazon Web Services, Inc. Amazon Elastic Block Store.

Manganaro, L. et al. Fetal MRI: what’s new? A short review. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 7, 41 (2023).

Lim, A., Wagner, M., Vidarsson, L., Ertl-Wagner, B. & Sussman, D. Automated Multi-Organ Segmentation in Fetal MRI. in 2025 ISMRM & ISMRT Annual Meeting & Exhibition Proceedings (Honolulu, Hawaii, USA).

Lim, A. Using Deep Learning To Improve Post-Acquisition Assessment In Fetal MRI: Quality Assurance, Motion Correction, and SegmentationToronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada,. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. (2025).

Momeni, N. Automated Deep Learning Algorithms For Placental Previa and Placental LocalizationToronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada,. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. (2025).

Hisham & Muhammad htop.

NVIDIA Corporation. Nvidia-Smi - NVIDIA System Management Interface Program. https://docs.nvidia.com/deploy/nvidia-smi/index.html

Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E. J., Woolrich, M. W. & Smith, S. M. FSL NeuroImage 62, 782–790 (2012).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by CIHR Project Grant #202303PJT-496119-MPI-ABAF-192837 (Sussman), the government of Ontario through the Early Researcher Award #ER21-16-130 (Sussman) and Toronto Metropolitan University.

Funding

This work was supported by CIHR Project Grant #202303PJT-496119-MPI-ABAF-192837 (Sussman), the government of Ontario through the Early Researcher Award #ER21-16-130 and Toronto Metropolitan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alejo Costanzo: Data curation, Software, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Software, Visualization. Adam Lim: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Michael Pereira: Software, Validation, Visualization, Formal Analysis. Yasmin Modarai: Software. Nika Momeni: Software. Joshua Eisenstat: Software. Justin Lo: Software, Data Curation. Matthias W. Wagner: Validation, Data Curation. Logi Vidarsson: Data Curation. Elka Miller: Validation. Birgit Ertl-Wagner: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision. Dafna Sussman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costanzo, A., Lim, A., Pereira, M. et al. Fetal Assessment Suite (FetAS): a web-based platform for automatic fetal MRI analysis using AI. Sci Rep 16, 2502 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32298-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32298-y