Abstract

The current study estimated the in vitro anti-inflammatory activity and in vivo anti-arthritic activities of the aqueous ethanolic extract of Ximenia caffra (X. caffra) seeds extract. It was hypothesized that X. caffra seeds extract, rich in phytochemicals that could modulate inflammatory pathways and protect joint tissues in an antigen-induced arthritis rat model. The chemical composition of X. caffra seeds extract was examined using liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS). Ximenia caffra seeds extract showed promising in vitro anti-inflammatory activity with an IC50 = 26.01 ± 0.85 µg/ml. To evaluate in vivo efficacy, antigen-induced arthritis was established in rats using Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA), followed by subcutaneous administration of X. caffra extract at doses of 26, 50, and 100 mg/kg body weight, alongside a standard drug control [Methotrexate (MTX), 0.3 mg/kg] in separate groups of animals. Anti-arthritic effects were assessed by measuring joint diameter, arthritic score, body weight, and through histopathological and ultrastructural analyses of joint and muscle tissues as well as osteoclast assessment, cytokine analyses, renal and kidney functions. The optimal dose (26 mg/kg) significantly alleviated arthritis symptoms, restoring joint and muscle morphology toward normal architecture. Ex vivo osteoclast evaluation and flow cytometric apoptosis analysis indicated that X. caffra extract promoted cellular recovery and reduced inflammatory damage. Furthermore, cytokine profiling demonstrated that treatment with X. caffra shifted pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IFN-γ) toward an anti-inflammatory balance by elevating IL-4 and regulating IgG1a/IgG2a ratios. Collectively, these results support the hypothesis that X. caffra seeds extract had potent anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic effects by modulating immune responses and preserving joint integrity, suggesting its potential as a natural therapeutic alternative for rheumatoid arthritis management after further validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a lifelong autoimmune sickness that affects about 0.2–1% of the world’s population1,2. It has multiple symptoms, including severe pain and joint swelling, that could develop into cartilage, joints, and bone destruction leading to disability in some cases3,4,5. RA has many systemic complications in essential body organs such as the lungs and pericardium, leading to a greater death percentage among cases with RA6,7. The cellular mechanisms involved in inflammatory joint diseases have advanced considerably through the use of animal models and have been alleviated in the testing of potential disease-targeting pharmaceuticals8,9,10. Various induced models of arthritis exhibit pathological features that resemble those of human disease and are widely used to investigate cellular and immunological mechanisms underlying arthritis. These induced arthritis models include: collagen-induced arthritis; antigen-induced arthritis11, zymosan-induced arthritis12, proteoglycan-induced arthritis13, and arthritis induced by injection of streptococcal cell wall fragments14. Many immune and joint-associated cells, such as chondrocytes, osteoclasts, and lymphocytes, along with pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, play essential roles in the pathology of RA. Chondrocytes have multifunctional roles in RA as they act as target and effector cells that upregulate the inflammatory response15. Osteoclasts have pivotal roles in bone resorption and the pathogenies of RA16. Modulating the secretion of inflammatory mediators using natural products offers an effective alternative strategy for treating RA17. Ximenia caffra is a tropical tiny tree belonging to the family Olacaceae18. It grows steadily in clay-rich soils and bears fruit during the winter season19. The plant has high protein content and contains vitamins and minerals, leading its use in many food additives. Its leaves and roots have been used as natural remedies in the cure of sterility and skin lesions as well as antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents20. The leaf extract of X. caffra contains many phenolic compounds, including quercetin and gallic acid. Medicinal plants, rich in phytochemicals such as terpenoids, phenolics, and flavonoids, exhibit potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities. These molecules regulate inflammatory mediators like TNF-α and IL-1β, with fewer negative effects than synthetic medicines. Long-term usage of synthetic chemicals frequently results in cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal issues. Medications derived from plants can treat the symptoms and underlying causes of oxidative stress and immunological dysregulation at the same time. Owing to their low toxicity and high biocompatibility, they are suitable for long-term therapy. Furthermore, the synergistic activity of the combined compounds in plant extracts also improves the effectiveness of treatment. Their traditional usage in inflammatory disorders is supported by ethnopharmacological evidence21. The current study evaluates the in vitro anti-inflammatory impact and in vivo anti-arthritic activities of the aqueous ethanolic extract of X. caffra seeds. It was proposed that its rich content of phytochemicals of the extract could modulate inflammatory mediators and immune cell responses. Moreover, it was hypothesized that X. caffra seeds extract would help to restore joint integrity and reduce arthritis severity in antigen-induced arthritic rats.

Material and methods

Preparation of the extract

Ximenia caffra dry seeds were purchased from a traditional medicine shop, taxonomically identified and authenticated by an expert (Dr. Nashaat N. Mahmoud) in the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University (Voucher: FS00257). The seeds were cleaned and kept at room temperature until extraction. Fifty grams (50 g) of dried X. caffra seeds were coarsely ground (Supplementary Fig. 1) and macerated in 70% aqueous ethanol for 24 h at ambient temperature with occasional stirring. The mixture was filtered through 0.45 μm Whatman filter paper, and the filtrate was collected in a clean flask. A yield of 4.5 g of dried extract was obtained and stored at − 80 °C until further use22.

LC-HRMS analysis of bioactive compounds

The separation was performed using LC-HRMS with an SB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm; Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. Elution was carried out using solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Gradient elution was performed at a flow rate of 200 µL/min with a 5 µL injection volume, as follows: 0–2 min, 20% B; 3–4 min, 25% B; 5–6 min, 35% B; 8–12 min, 65% B; 14–16 min, 80% B; and 20–28 min, 20% B. Mass spectrometric detection was carried out on a 3200 QTRAP mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, MA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and a triple quadrupole–ion trap mass analyzer. Compounds were identified by comparison with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) mass spectral library (USA)22,23.

In vitro anti-inflammatory testing

The aqueous ethanolic extract of X. caffra seeds and the reference standard Ibuprofen were tested to investigate their anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of the lipoxygenase (LOX) enzyme from Glycine max (type I1 B). The assay was performed with slight modifications to a previously described method24. Briefly, in 96-well plates, 100 µL of soybean LOX solution (1000 U/mL in borate buffer, pH 9) and 200 µL of borate buffer were mixed with varying concentrations of the crude extract to obtain a final concentration range of 0.98–125 µg/mL. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 15 min. Samples were then preincubated with 100 µL of linoleic acid (substrate) to initiate the reaction. The inhibitory activity was determined by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 234 nm using a microplate reader (BIOTEK, USA).

Animals and treatments

Male Wister albino rats weighing 140–160 g were purchased from the animal unit of the faculty of medicine at Ain shams University, left for acclimation for two weeks, and split into six groups (nine rats each). Isoflurane (Sigma, Egypt) has been used to anesthetize rats at a level of 1–3%. The first group served as the negative control (NC) and received subcutaneous injections of saline and 10% Tween 80, respectively. The other groups were injected subcutaneously at the base of the tail with 100 µL of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) twice weekly for 15 days to induce an arthritis model25. After the establishment of the antigen-induced model, signs of arthritis appeared in the remaining rat groups. The second group represented the positive control (PC) and received no treatment. The third, fourth, and fifth groups were administered X. caffra seeds extract at doses of 26, 50, and 100 mg/kg body weight (b.w.), respectively, via subcutaneous injection. The sixth group received the anti-rheumatic standard drug methotrexate (MTX; Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland) at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg b.w., administered subcutaneously twice per week26. The X. caffra seeds extract was administered three times per week for two weeks. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Regional Center for Mycology and Biotechnology (Approval No. RCMB22062020). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 8023, revised 1978).

Assessing swelling and mobility scoring

The clinical signs of inflammation were monitored daily from the first day after arthritis induction until the end of the experiment. The severity of inflammation was classified into six levels as follows: level 0 (inflammation score = 0), level 1 (inflammation score between 0.1 and 0.9), level 2 (inflammation score between 1 and 1.9), level 3 (inflammation score between 2 and 2.9), level 4 (inflammation score between 3 and 4.9) and level 5 (arthritis score of 5.0 and more than 5.0). The arthritis score was evaluated alongside joint swelling, which was measured using a digital caliper (Fischer Darex, France). Body weights were recorded regularly and expressed as mean values for all six rat groups27,28.

Histopathology studies

Rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the tibiofemoral joints and hind limb muscles were harvested. The tibiofemoral joint samples were decalcified using 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Thermo Fisher, USA) for two weeks. The tissues were then sectioned into 10 μm-thick slices and processed for histopathological examination. Slides were stained sequentially with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Fisher Scientific, USA), then dehydrated, mounted, and air-dried at room temperature for several days before imaging. Histological images were captured at 40× magnification using a Zeiss microscope and imaging system (Carl Zeiss Inc., Germany)29.

Transmission electron microscopy

Decalcified tibiofemoral joint and hind limb muscle samples were collected to be processed for transmission electron microscopy. Samples were fixated with 2% glutaraldehyde and 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated with acetone, embedded with epoxy resin, sectioned using an ultra-microtome, and stained. The different cellular structures were then visualized by transmission electron microscopy (JEOL, Japan)30.

Cell culture studies

Bone marrow-derived monocyte/macrophages were isolated from the tibias of animals by scrub the bone-marrow hollow with RPMI-1640 medium. The cells were brood for 6 h to split non- adherent from adherent cells. Non-adherent cells were then cultured in 48-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well and cultivated in the existence of 10 ng/mL rh M-CSF (Life Science, USA) for 3 days to macrophage-like osteoclast precursor cells. After 3 days, the non-adherent cells were washed, and pre-osteoclasts were cultivated in the presence of 10 ng/mL M-CSF, 50 ng/mL, RANKL, and various levels of sodium butyrate for 4 days to induce the formation of osteoclasts. On the second day, the medium was replaced with fresh medium contained M-CSF, RANKL, and sodium butyrate. Photos were taken using inverted microscopy (Zeiss microscope and imaging system, Carl Zeiss Inc., Germany)31,32.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cultured osteoclasts were de-aggregated using trypsin in 0.25% pancreatin and washed using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The death rate was assessed by an Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining kit (BD Bioscience, USA). The cells were suspended in a buffer has PI stock solution and kept away from light at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were examined by flow cytometry (BD Bioscience, USA)33,34.

ELISA assays

The serum titers of cytokines including IFN- γ, IL-1β, IgG1a, IgG2a, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-17 were quantified by an ELISA kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Biochemical assays

The levels of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatinine, and urea have been detected in the serum that collected from all examined animal groups using (Human Diagnostic Company, Germany) kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol35.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 5). For comparisons, an unpaired Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test were used; the significance level was measured at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Identification of compounds in X. caffra seeds extract

The following compounds were positively identified using 198 LC-HRMS: citric acid with m/z (191, 111, 87 and 173), Gallic acid with m/z (125, 169 and 111), aconitic acid with m/z (111), procyanidin B1 with m/z (289, 407, 425 and 577), p-Coumaorylquinic acid with m/z (163, 119, 191 and 337), catechin with m/z (289, 125, 203, 245 and 151), procyanidin B2 with m/z (289, 407, 425 and 577), epicatechin at retention time 13.57 min., quercetin galloyl glucoside with m/z (300, 615, 463, 255 and 169), quercetin galloyl glucoside with m/z ( 300, 463 and 615), quercetin-3-O-robinobioside with m/z (300, 609, 271 and 125), rutin with m/z (300, 609, 271 and 255), hyperoside with m/z (300, 463, 271, 255), isoquercitrin with m/z (300, 463, 271,301 and 255), quercetin-3-O-glucoside with m/z (300, 271, 463, 255 and 125), kaempferol glucoside with m/z (285,169 and 447), luteolin-7-O-glucoside with m/z (285, 284, 169,125 and 447), trilobatin with m/z (315 and 345), quercetin- 3-O-pentoside with m/z ( 300, 271, 255, 433 and 315), quercetin rhamnoside with m/z (300, 271, 255 and 447), quercetin rhamnoside with m/z (300, 271, 255, 447, and 243), quercetin with m/z (125 and 169), hesperetin at retention time 24.49 min., dihydroxy hexadecenoic acid with m/z (287) (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). In the present study, the aqueous ethanolic extract of X. caffra seeds yielded various compounds with diverse levels where, catechin, citric acid, hyperoside, isoquercetin, procyanidin B1, kaempferol glucoside, quercetin-3-O-robinobioside, and rutin were the most frequent bioactive compounds with highest concentrations in extract. The findings are in same line with other reports22,36 who used ethanol to extract efficient antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds as solvent with minimal cytotoxicity.

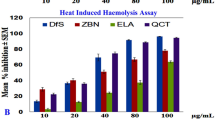

In vitro anti-inflammatory activity

The results indicated that the aqueous ethanolic seeds extract of X. caffra significantly (p ≤ 0.05) inhibited the LOX enzyme, with a promising inhibitory impact (IC50 = 26.01 ± 0.85 µg/mL) compared to Ibuprofen, as a reference compound (IC50 = 1.5 ± 1.3 µg/mL), respectively. In particular, X. caffra seeds extract possesses anti-inflammatory potential in a dose dependent manner, as shown in (Fig. 1). The aqueous ethanolic extract of X. caffra seeds showed a promising in vitro anti-inflammatory effect, attributed to its phenolic and flavonoids content. In accordance with Tremocoldi et al.37, who reported the pharmaceutical anti-inflammatory role of avocado due to its content of procyanidin B1, catechin, and epicatechin. Additionally, Chen et al.38 explained the action of rutin in the treatment of wound in diabetic animal model through an anti-inflammatory response. Furthermore, Shen et al.39 examined the role of isoquercitrin in controlling oxidative and inflammatory responses in rat muscles model. Moreover, Abdallah et al.40 reported the anti-inflammatory role of kaempferol-7- O-β-glucoside, cuneatannin, and 2R-naringenin from Euphorbia cuneata extract in pulmonary infected animals. Lastly, Sun et al.41 reported both in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory effects of hyperoside.

Effect of X. caffra extract on digital scoring of disease

Arthritis score, joint size, and body weight have been used to assess the development of disease in the present model of antigen-induced arthritis. On Day 0, animals were induced using CFA twice a week for 15 days, while the negative control group was administered saline and 10% Tween-80, showing no signs of inflammation, regular joint size, and a steady increase in body weight as the rats maintained normal feeding behavior until the end of the experiment. However, ankle joint sizes, arthritis scores, and body weight differed significantly (P ≤ 0.05) in induced rats which received no treatment compared to negative control rats after three days post-induction (Fig. 2A–C). Treatment with 26 and 50 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract in the separate animals’ groups significantly reduced (P ≤ 0.05) ankle joint size and arthritis scores, showing effects comparable to those of the MTX-treated group, and restored near-normal measurements by the end of the experiment. Administration of 100 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract had a marked effect on all tested parameters, resulting in minimal inflammation throughout the study period. Furthermore, body weight was enhanced in the tested groups, confirming the effectiveness of the treatments. This model designed to study joint structural alterations, characterized by pannus formation and infiltration of various cell types, which are early manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis42. This report studied the anti-inflammatory effect of different doses of X. caffra seeds extract in AIA rats to primarily illustrate the role of chondrocytes, osteoclasts and various inflammatory cytokines in the investigated model. Administration of X. caffra seeds extract produced an early reduction in inflammatory signs in a dose-dependent manner, consistent with Alamgeer et al.43, who reported that Berberis calliobotrys extracts improved inflamed paw conditions by the 15th day of treatment. Similarly, Alternanthera bettzickiana ethanolic extract significantly reduced arthritis symptoms compared to normal rats44, while Yang et al.45 reported restoration of normal body weight following treatment with Pterospermum heterophyllum extract in experimental animals.

Standard methods were used for 15 days after disease induction. (A) Experimental arthritis scores of tested groups comparing levels upon using 26, 50 and 100 mg/kg X. caffra seeds extract versus negative, induced and of positive control groups. Additional conventional measurements were manually collected in the present model, such as joint measurements (B), and body weight (C) confirmed effectiveness of treatments. ∗P ≤ 0.05 vs. control. (n = 3).

Histopathology and TEM examinations

Sections from the normal (negative control) group showed that the knee joint contained typical articular hyaline cartilage with elongated chondrocytes exhibiting a regular nuclear structure (Fig. 3A, a). In contrast, the antigen-induced arthritic group showed irregular and condensed synovial tissue containing numerous inflammatory cells and exudates, as well as shrunken, degenerated chondrocytes with dark, eccentric nuclei (Fig. 3B, b). Treatment with 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract enhanced chondrogenic perichondrium differentiation, resulting in regularly preserved chondrocytes with normal nuclei and cytoplasm, thereby restoring normal joint structure (Figs. 3C, c). Sections from rats administered 50 and 100 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract showed differentiated cells with mild nodular necrosis, irregular chondrocyte nuclei, and vacuolated cytoplasm, suggesting that these higher doses were suboptimal for proper cellular organization (Fig. 3D, d, E and e). In contrast, sections from the MTX-treated group showed a reduction in peripheral chondrocytes and slightly irregular nuclear morphology in the articular cartilage (Fig. 3F, f).

Chondrocytes are enclosed within the extracellular matrix of articular cartilage, which contains various proteins such as collagen type II and hyaluronan46. It has been shown that curcumin, in vitro, downregulates IL-1β and MMP-3 production, thereby enhancing the gene expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in normal chondrocytes47. In the present study, X. caffra seeds extract exhibited a regenerative effect on chondrocytes in rats’ joints, in agreement with Abdel-Azeem et al.48, who reported that secondary metabolites isolated from Chaetomium globosum helped preserve chondrocyte structure. Totoson et al.49 reported muscle proteolysis in the rectus femoris and tibialis anterior muscles, accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration on day 40 after induction in rats. Consistent with our findings, an inflammatory response associated with structural alterations in muscle tissue was observed. Moreover, treatment with graded doses of X. caffra seeds extract reversed these harmful effects, leading to the restoration of normal movement in the animals.

H&E staining and transmission electron micrographs of rat’s knee joints. Control (A, a), AAI (B, b) knee joint. (F, f), served as positive control where induced animals received standard drug [MTX; 0.3 mg/kg BW]. Where chondrocytes are regular shapes arranged in parallel rows (green arrows) in the normal group, while chondrocytes shrink (green arrows) in infected animals with irregular nucleus shape and pannus reaction in the induced rats. Note a decrease number of hypertrophic chondrocytes (green arrows) in the cartilage zone in positive control group as compared to the control knee. (C, c; D, d; E, e) displaying inflammatory cellular buildup and differentiated cells and nodular necrosis. Where 26, 50 and 100 mg/kg X. caffra seeds extracts were used respectively with induced animals and caused the tissue injury with minor inflammation (magnification 20× to images A–F & 8000× to images a–f).

To evaluate the effect of graded doses of X. caffra seeds extract on the morphological structure of hind limb muscles, tissue samples were collected, processed, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and prepared for transmission electron microscopy examination. In the negative control group, classical muscle structure was observed, characterized by regular fibers and nuclei with homogeneous distribution (Fig. 4A, a). However, in antigen-induced arthritic animals, severe inflammation, myofiber degradation, reduced muscle mass, decreased fiber size, and the presence of large vacuoles were evident (Fig. 4B, b). Treatment with 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract in the induced rats restored the normal organization of muscle bundles, showing numerous fibers with regularly distributed nuclei (Fig. 4C, c). Furthermore, administration of 50 and 100 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract resulted in reduced cellular infiltration, although fibers appeared irregular with numerous centrally located nuclei (Fig. 4D, d, E and e). In comparison, muscles from MTX-treated rats showed slight necrosis and mild nuclear aggregation (Fig. 4F, f).

Photomicrographs of muscles taken from control rats or those submitted to adjuvant-induced arthritis (AIA). In the control groups, the muscles exhibited normal morphology (A, a). In AIA group, the muscle showed signs of damage where asterisk: nuclear aggregations; blue arrow: inflammatory infiltrate (B, b). While induced animals were treated with 26, 50 and 100 mg/kg X. caffra seeds extract respectively showing normal muscle fibers (yellow arrows) (C–E) & (c–e). The last group where induced animals treated with MTX as standard drug showed slight necrosis in muscles (green arrow). Where (A–F) Staining: hematoxylin and eosin (20× magnification) while (a–f) Transmission electron micrographs (8000× magnification).

Effect of X. caffra extract on ex vivo cultured osteoclast

To investigate the effect of X. caffra seeds extract on osteoclast structure, isolated osteoclasts from different experimental groups were cultured for seven days and examined using an inverted microscope. A significant decrease (p < 0.05) was observed in the size of osteoclast cells isolated from induced rats compared to cells from the negative control group. In contrast, osteoclasts cultured from animals treated with 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract regained their normal morphology, resembling that of the negative control group. A slight change in osteoclast size was observed in cultured cells from animals treated with 50 and 100 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract, as well as MTX-treated rats (Fig. 5I). These findings indicate that 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract represents an optimum dose for enhancing the maturation and preservation of osteoclast structure in treated arthritic rats. The apoptosis rate was measured ex vivo in osteoclasts using an Annexin V staining kit and flow cytometry. The apoptotic rate in the normal group was 19 ± 1.7%, whereas it significantly increased to 44.8 ± 4.6% in cultured cells from induced animals (p < 0.05), indicating an elevated rate of cell death. Treatment with 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract was found to be optimal in restoring osteoclast morphology and normalizing apoptosis levels, comparable to the standard drug-treated group (Fig. 5II). Similarly, Hong et al.50 reported that Chrysanthemum zawadskii regulated osteoclast development and mitigated inflammatory colitis and arthritis in experimental animals. Consistent with their findings, our results demonstrated that 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract played a notable role in modulating osteoclast apoptosis in induced arthritic rats.

I-Microscopic examination of prepared osteoclasts from rat bone marrow progenitors (magnification 200X) where (A) Control Cells, (B) Cells cultured from induced rats. (C, D, E) Cells cultured from induced rats and treated with X. caffra seeds extract 26, 50 and 100 mg/kg respectively and (F) Cells cultured from induced rats and treated with standard drug [MTX; 0.3 mg/kg BW]. Cells size was measured and by image analysis using the ImageJ software and affected in induced animals while this size recovers upon using 26 and 50 mg/kg X. caffra seeds extract compared to control and treatment by standard drug. II-Apoptosis in osteoclasts cultured from normal, induced rats, induced and treated with 26, 50 and 100 mg/kg X. caffra seeds extract, induced rats and treated with standard drug were detected by flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide on the cells. Where number of cells were affected in induced animals while this number recover upon using 26 mg/kg X. caffra compared to control and treatment by standard drug. (*order of flow cytometry results is same order like of microscopic osteoclast examinations).

Effect of X. caffra extract on cytokines production

Cytokine (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IgG1a, IgG2a, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-17) concentrations were measured at the end of the experiment. Serum samples were collected, and cytokine levels were determined using an ELISA kit. Cytokine levels differed between the control and treated groups. The results showed how 26, 50, and 100 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract affected cytokine expression in rats. In normal rats, the tested cytokines were within the normal range, and no inflammatory response was observed in the negative control group. In contrast, in the antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) group, the levels of IFN‐γ, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17 were significantly increased (p < 0.05), while IL-4 levels were significantly decreased (p < 0.05). Treatment with 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract exhibited a highly protective effect, as both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels returned to near-normal values, comparable to those observed in methotrexate-treated animals (0.3 mg/kg body weight). Treatment with 50 and 100 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract also produced a beneficial effect on cytokine levels in induced animals, though less pronounced than that observed with the 26 mg/kg dose (Fig. 6).The release of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, COX-2, and 5-LOX plays a key role in the progression of inflammation, alteration of joint function, synovial degeneration, cartilage destruction, and bone remodeling. IL-1β stimulates osteoclast activation, leading to bone damage, while IL-6 contributes to immune regulation and osteoclast differentiation. Moreover, IL-17 has a crucial role in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by promoting excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), as well as enhancing osteoclast activation51,52. The present study revealed that treatment with X. caffra seeds extract significantly reduced the concentrations of IFN-γ, IgG1a, IgG2a, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17, while enhancing IL-4 production, confirming the anti-arthritic activity of 26 mg/kg of X. caffra seeds extract through the downregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators and the upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines in the experimental rat model.

Effects of 26, 50 and 100 mg/kg X. caffra seeds extract on the levels of cytokines in serum of AIA rats versus normal rats and upon treatment using MTX. Pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels in serum were measured using ELISA. (A) IFN-γ, (B) IL-1β, (C) IgG1a, (D) IgG2a, (E) IL-4, (F) IL-6 (G) IL-17. Values are presented as mean ± SEM of nine animals per group. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Effect of X. caffra extract on liver and kidney functions

To test the effect of a mixture of active components from X. caffra seeds extract on liver and kidney functions in all tested rat groups in this study, biochemical tests were conducted. ALT and AST were measured as markers of liver function (Fig. 7A and B). ALT and AST values were significantly increased in the MTX group (p < 0.05) compared to the control group, while only slight increases were observed in the induced and treated animals receiving different doses of X. caffra seeds extract. Creatinine and urea were evaluated as markers of kidney functions (Fig. 7C and D). It was observed that creatinine levels were significantly elevated (p < 0.05) in the MTX group, accompanied by a slight increase in urea levels in the same group. However, the other tested animal groups exhibited kidney function values comparable to those of the control group, indicating the safety of X. caffra seed extract on hepatic and renal functions in the tested animals. MTX is commonly used in low doses to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, but its use is limited due to its harmful effects on various tissues and organs resulting from its strong oxidative activity53,54. In the present study, X. caffra seeds extract demonstrated minimal effects on liver and kidney functions, suggesting that it can be safely used in the treatment of MTX-induced toxicity in rats.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that X. caffra seeds aqueous ethanolic extract has strong anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic properties in both in vitro and in vivo settings. Administration of 26 mg/kg of the extract had maximally reduced the symptoms of arthritis, improved protective mediators (IL-4), decreased inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, and IFN-γ), and restored joint structure. Bioactive polyphenols and flavonoids, especially those with established immunomodulatory and antioxidant properties, are probably responsible for these biological effects. Besides, the results imply that X. caffra seeds extract may provide a safe and efficient natural alternative for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with low hepatic and renal toxicity. It should be noted that this study has several limitations including: (1) The present results are based on an animal model, and it is yet unknown if they apply to rheumatoid arthritis in humans. (2) Chronic toxicity and pharmacokinetics were not thoroughly examined; only one type of extract and a small dose range were assessed. (3) The exact chemical and molecular processes behind the observed immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory actions were not entirely understood. (4) Reproducibility may also be impacted by variations in phytochemical composting upon change of ecological conditions surrounding the plants. Thus, more research involving a variety of extracts, longer treatment periods, mechanistic evaluations, and clinical trials is required to confirm X. caffra’s therapeutic potential for rheumatoid arthritis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LC-HRMS:

-

liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry

- LOX enzyme:

-

lipoxygenase enzyme

- CFA:

-

Complete Freund’s Adjuvant

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

References

Cross, M. et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 1316–1322 (2014).

Lwin, M. N., Serhal, L., Holroyd, C. & Edwards, C. J. Rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of mental health on disease: A narrative review. Rheumatol. Therapy. 7(3), 457–471 (2020).

Boers, M., Kostense, P. J., Verhoeven, A. C., van der Linden, S. & COBRA Trial Group. Combination therapy Bij rheumatoid Arthritis. Inflammation and damage in an individual joint predict further damage in that joint in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 44(10), 2242–2246 (2001).

Boonen, A. et al. Orthopaedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A shift towards more frequent and earlier non-joint-sacrificing surgery. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65(5), 694–695 (2006).

Fardellone, P., Salawati, E., Le Monnier, L. & Goëb, V. Bone loss, osteoporosis, and fractures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A review. J. Clin. Med. 9(10), 3361. (2020).

Turesson, C., O’Fallon, W. M., Crowson, C. S., Gabriel, S. E. & Matteson, E. L. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 29(1), 62–67 (2002).

Young, A. & Koduri, G. Extra-articular manifestations and complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 21(5), 907–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2007.05.007 (2007).

Hegen, M., Keith, J. C. Jr, Collins, M. & Nickerson-Nutter, C. L. Utility of animal models for identification of potential therapeutics for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67(11), 1505–1515 (2008).

Bevaart, L., Vervoordeldonk, M. J. & Tak, P. P. Evaluation of therapeutic targets in animal models of arthritis: How does it relate to rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 62(8), 2192–2205 (2010).

Brand, D. D., Latham, K. A. & Rosloniec, E. F. Collagen-induced arthritis. Nat. Protoc. 2(5), 1269–1275 (2007).

Van den Berg, W. B., Joosten, L. A. & van Lent, P. L. Murine antigen-induced arthritis. Methods Mol. Med. 136, 243–253 (2007).

Frasnelli, M. E., Tarussio, D., Chobaz-Péclat, V., Busso, N. & So, A. TLR2 modulates inflammation in zymosan-induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis Res. Ther. 7(2), R370–R379 (2005).

Glant, T. T. et al. Proteoglycan-induced arthritis and Recombinant human proteoglycan Aggrecan G1 domain-induced arthritis in BALB/c mice resembling two subtypes of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 63(5), 1312–1321 (2011).

Koenders, M. I. et al. Interleukin-17 receptor deficiency results in impaired synovial expression of interleukin-1 and matrix metalloproteinases 3, 9, and 13 and prevents cartilage destruction during chronic reactivated Streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 52(10), 3239–3247 (2005).

Tseng, C. C. et al. Dual role of chondrocytes in rheumatoid arthritis: the chicken and the egg. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(3), 1071 (2020).

Yokota, K. Inflammation and osteoclasts. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 40(5), 367–376 (2017). Japanese.

Shan, L., Tong, L., Hang, L. & Fan, H. Fangchinoline supplementation attenuates inflammatory markers in experimental rheumatoid arthritis-induced rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 111, 142–150 (2019).

Otieno, J. N., Hosea, K. M., Lyaruu, H. V. & Mahunnah, R. L. Multi-plant or single-plant extracts, which is the most effective for local healing in tanzania? African journal of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicines. AJTCAM 5(2), 165–172 (2008).

Ndhlala, A. R. et al. Phenolic content and profiles of selected wild fruits of zimbabwe: Ximena caffra, Artobotrys brachypetalus and Syzygium cordatum. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 43(8), 1333–1337 (2008).

Munodawafa, T., Chagonda, L. S. & Moyo, S. R. Antimicrobial and phytochemical screening of some Zimbabwean medicinal plants. J. Biologically Act. Prod. Nat. 3(5–6), 323–330 (2013).

Marrelli, M., Amodeo, V., Perri, M. R., Conforti, F. & Statti, G. Essential oils and bioactive components against arthritis: A novel perspective on their therapeutic potential. Plants (Basel Switzerland). 9(10), 1252 (2020).

Oosthuizen, D. et al. Solvent extraction of polyphenolics from the Indigenous African fruit Ximenia Caffra and characterization by LC-HRMS. Antioxid. (Basel). 7(8), 103 (2018).

Anna, B., Natalia, V., Małgorzata, C., Wioleta, P. & Katarzyna, S. Polyphenol composition of extracts of the fruits of Laserpitium krapffii Crantz and their antioxidant and cytotoxic activity. Antioxid. (Basel). 8(9), 363 (2019).

Granica, S., Czerwińska, M. E., Piwowarski, J. P., Ziaja, M. & Kiss, A. K. Chemical composition, antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activity of extracts prepared from aerial parts of Oenothera biennis L. and oenothera paradoxa Hudziok obtained after seeds cultivation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 30(4), 801–810 (2013).

Bendele, A. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 1, 377–385 (2001).

Suzuki, H., Hirano, N., Watanabe, C. & Tarumoto, Y. Carbon tetrachloride does not induce micronucleus in either mouse bone Marro or peripheral blood. Mutat. Res. 394, 77–80 (1997).

Claude, M. et al. Association between arthritis score at the onset of the disease and long-term locomotor outcome in adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17(1), 184 (2015).

Lim, M. A. et al. Development of the digital arthritis index, a novel metric to measure disease parameters in a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 8 (2017).

Collins, K. H., Paul, H. A., Reimer, R. A., Hart, D. A. & Herzog, W. Relationship between inflammation, the gut microbiota, and metabolic osteoarthritis development: studies in a rat model. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 23, 1989–1998 (2015).

Fan, C., Xiaoya, C., Sen, C., Shaopeng, H. & Hui, J. LncRNA LOC100912373 modulates PDK1 expression by sponging miR-17-5p to promote the proliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Transl Res. 12(12), 7709–7723 (2020).

Barrett, J. P., Costello, D. A., O’Sullivan, J., Cowley, T. R. & Lynch, M. A. Bone marrow-derived macrophages from aged rats are more responsive to inflammatory stimuli. J. Neuroinflammation. 12, 67 (2015).

Chevalier, C. et al. Primary mouse osteoblast and osteoclast culturing and analysis. STAR. Protoc. 2(2), 100452 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Osteoprotegerin induces apoptosis of osteoclasts and osteoclast precursor cells via the Fas/Fas ligand pathway. PLoS One. 10(11), e0142519 (2015).

Yuan, K. et al. Cerium oxide nanoparticles regulate osteoclast differentiation bidirectionally by modulating the cellular production of reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Nanomed. 15, 6355–6372 (2020).

Akhtar, M. F. et al. Chemical characterization and anti-arthritic appraisal of monotheca buxifolia methanolic extract in complete freund’s Adjuvant-induced arthritis in Wistar rats. Inflammopharmacology 29(2), 393–408 (2021).

Gironi, F. & Piemonte, V. Temperature and solvent effects on polyphenol extraction process from chestnut tree wood. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 89, 857–862 (2011).

Tremocoldi, M. A. et al. Exploration of avocado by-products as natural sources of bioactive compounds. PLoS One. 13(2), e0192577 (2018).

Chen, L. Y. et al. Effects of Rutin on wound healing in hyperglycemic rats. Antioxid. (Basel). 9(11), 1122 (2020).

Shen, Y. et al. Isoquercitrin delays denervated soleus muscle atrophy by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation. Front. Physiol. 11, 988 (2020).

Abdallah, H. M. et al. Euphorbiacuneata represses LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice via its antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities. Plants (Basel). 9(11), 1620 (2020).

Sun, K. et al. Hyperoside ameliorates the progression of osteoarthritis: An in vitro and in vivo study. Phytomedicine 80, 153387 (2021).

Irmler, I. M., Gajda, M. & Bräuer, R. Exacerbation of antigen-induced arthritis in IFN-gamma-deficient mice as a result of unrestricted IL-17 response. J. Immunol. 179(9), 6228–6236 (2007).

Alamgeer, A., Hasan, U. H., Uttra, A. M. & Rasool, S. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo anti-arthritic potential of Berberis calliobotrys. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 10, 807–819 (2015).

Manan, M. et al. Antiarthritic Potential of comprehensively standardized extract of Alternanthera bettzickiana: In vitro and in vivo studies. ACS Omega. 5(31), 19478–19496 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Chemical composition of Pterospermum heterophyllum root and its anti-arthritis effect on adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats via modulation of inflammatory responses. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 584849 (2020).

Lee, G. J. et al. Biological effects of the herbal plant-derived phytoestrogen Bavachin in primary rat chondrocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 38(8), 1199–1207 (2015).

Comblain, F. et al. Curcuminoids extract, hydrolyzed collagen and green tea extract synergically inhibit inflammatory and catabolic mediator’s synthesis by normal bovine and Osteoarthritic human chondrocytes in monolayer. PLoS One. 10(3), e0121654 (2015).

Abdel-Azeem, A. M., Zaki, S. M., Khalil, W. F., Makhlouf, N. A. & Farghaly, L. M. Anti-rheumatoid activity of secondary metabolites produced by endophytic Chaetomium globosum. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1477 (2016).

Totoson, P. et al. Microvascular abnormalities in adjuvant-induced arthritis: relationship to macrovascular endothelial function and markers of endothelial activation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 1203–1213 (2015).

Hong, J. M. et al. BST106 protects against cartilage damage by Inhibition of apoptosis and enhancement of autophagy in Osteoarthritic rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 41(8), 1257–1268 (2018).

Jing, R. et al. Therapeutic effects of the total lignans from Vitex Negundo seeds on collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Phytomedicine 58(1), 152825 (2019).

Dar, A. A. et al. The protective role of Luteolin against the methotrexate-induced hepato-renal toxicity via its antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects in rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 40(7), 1194–1207 (2021).

Jafaripour, L. et al. Effects of Rosmarinic acid on Methotrexate-induced nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in Wistar rats. Indian J. Nephrol. 231(3), 218–224 (2021).

Nakafero, G. et al. What is the incidence of methotrexate or Leflunomide discontinuation related to cytopenia, liver enzyme elevation or kidney function decline? Rheumatol. (Oxford). keab254. (2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohammed Yosri: conceptualization, writing review, methodology, resources, results, investigation, writing original draft, supervision and submitting the paper to the journal. Alsayed E. Mekky: writing review, editing, supervision, methodology, results, writing original draft, resources and investigation. Mahmoud M. Elaasser: phytochemical testing, writing review, methodology, writing original draft, resources and investigation, Marwa M. Abdel-Aziz: writing review, methodology, resources and investigation. Fady Sayed Youssef: writing review, editing, methodology, writing original draft, resources, supervision and investigation. Hend A. Kamel: methodology, resources and investigation. Mahmoud M. Al-Habibi: methodology, writing original draft, resources and investigation. Eman E. Helal: writing review, methodology, writing original draft, resources and investigation. Basma H. Amin: writing review, methodology, writing original draft, resources and investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal studies were approved by the ethical committee in the Regional Center for Mycology and Biotechnology, Al-Azhar University (No. RCMB22062020). All animal research studies follow the ARRIVE guidelines and are conducted in compliance with the National Institute of Health’s handbook for the care and use of lab animals (NIH publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yosri, M., Mekky, A.E., Elaasser, M.M. et al. In vitro anti-inflammatory potential and in vivo anti-arthritis activities of Ximenia caffra extract on antigen-induced arthritis in rats. Sci Rep 16, 797 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32300-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32300-7