Abstract

Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) is a robust cementitious material with high compressive strength exceeding 125 MPa. UHPC can reach up to 80 MPa after one day of casting, which expands the material application domain and makes it appealing for accelerated construction. The appropriate on-site quality control methods should be implemented to guarantee that desired UHPC design has been achieved. The cylinder specimens of 75 mm diameter are used in the United States for quality control purposes. However, cylinders require surface preparation and grinding using special equipment, which consumes more time and affects the strength results at very early ages. Thus, this research aims to establish the conversion factors to use cubes confidently for UHPC quality control. To provide comprehensive and generalized results and allow for immediate implementation, this research considers, for the first time, five UHPC types and a total of eight mixtures with variable steel fiber (SFs) ratios, different cube sizes, and examines the compressive behavior at both early and late ages. The study provides results from about 900 specimens with different curing conditions sets and covers a wide range of strength from 7 to 140 MPa. The experimental results assist in understanding the shape and size effect and revisit the cubes-to-cylinders strength conversion factors. A detailed application for strength maturity was also conducted to further validate the newly proposed conversion factors and extend the use of cubes for early age quality control. To summarize, this study presents new conversion factors for the cube compressive strength at an early age, in addition to recommendations for adopting the strength maturity method for quality control. The dataset of all tested specimens is also summarized and presented in the Appendices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing interest in the use of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) due to its superior mechanical characteristics and durability. UHPC is widely used for accelerated construction, where construction duration is crucial. The widespread application of UHPC is in field joints for accelerated bridge construction (ABC)1,2. The ABC technology reduces the duration of road closures and eliminates the need for altering routes and resulting traffic jams. UHPC achieves high early-age strength, making it ideal for closure and field joints, resulting in shorter construction time and reduced costs. The UHPC is preferable in accelerated bridge construction due to high early-age strength development. The cementitious grout used in field-cast connection can achieve compressive strength of 20–35 MPa after 24 hours3. However, the UHPC mixes can gain compressive strength of about 95 MPa within 12 hours4. Another study3 reported that UHPC achieved a compressive strength of 70 MPa after 24 hours. Apart from high early-age strength development, UHPC exhibits superior durability to conventional grouts. An earlier study5 indicated that conventional grouts developed shrinkage cracks within a few days, while the deck concrete cracked after several weeks. However, UHPC developed fine and fiber-bridged cracks and much later visible cracks without the abrupt loss of ring strain that was observed for the grouts3,5. Furthermore, the UHPC exhibits low chloride ion penetration and good freeze-thaw resistance compared to conventional grout5. The bond performance of UHPC is superior to conventional concrete and grouts. The pull-out tests on rebars embedded in UHPC indicated that the bond strength of UHPC is six times more than that of conventional concrete. In addition, the required development length of rebars can be reduced by 50% relative to that of grout-filled duct connections6. Apart from ABC applications, the use of UHPC can substantially reduce the cross-sections of architectural and structural members. Moreover, the new geometric forms and shapes can be realized with the use of UHPC. These characteristics motivate the precast industry to adopt UHPC and further utilize the high UHPC early age strength and stiffness7,8,9.

Given the importance of characterizing UHPC compressive strength, especially at an early age for precast or accelerated construction applications, a robust quality control and testing method is required. Currently, in the United States, when casting UHPC, standard 75 × 150 mm (3 × 6 inch) cylinders are sampled and delivered to specialized laboratories for preparation and compression testing to verify the strength10. Preparing the UHPC cylinder specimens involves cutting and grinding their end surfaces. These procedures are time-consuming and demand specialized equipment, which is often impractical to transport to on-site quality control labs, especially in remote locations. The cube specimens can be used as an alternative to cylinder specimens to reduce cost and time. In some countries, like China12, cubes are employed for quality control testing, with the standard specimen in compression being a 100 × 100-mm (4-inch) cube. The selection of cube size was also based on standard practices, in addition to convenience for on-site use. The standard BS EN 12390–1: 202111 suggests that a nominal cube size of 100 × 100 mm can be used to determine the compressive strength of concrete. Moreover, the Chinese standard GB/T 50,107 − 201012 also suggests evaluating the concrete compressive strength by testing 100 × 100 mm cubes. For steel fiber-reinforced concrete, the least dimension of the specimen should be at least 3 times the length of the fibers. The use of 50 × 50 mm satisfies this criterion. Furthermore, the earlier studies also evaluated the compressive strength of UHPC by testing 50 × 50 mm cube specimens13,14. The cube specimens are preferable for construction projects, since most site-based compression testing machines can accommodate the cube specimens. Furthermore, the cube specimens can be used for quick compressive strength evaluation (e.g., at the age of one day). The primary advantage of employing cubes is that the cubes obviate the need for any specialized preparatory procedures, such as face cutting and grinding. Other commonly available cube sizes include the 50 × 50-mm (2-inch) cube, which, if demonstrated to be viable for UHPC, can be advantageous because its relatively smaller breaking loads can be achieved using any regular on-site quality control compression machine. However, further research is necessary to explore the impact of various specimen shapes and sizes on compression strength estimates and conversion factors. This topic received limited attention in the past, as summarized below.

Mansur and Islam15 examined UHPC specimens subjected to compressive testing at 28 days. The specimens consisted of cylinders and cubes. Eleven distinct concrete mixtures exhibited compressive strengths ranging from 20 to 100 MPa. It was observed that the ratio of cube-to-cylinder strength varied following different concrete strength levels and specimen aspect ratios. Graybeal16 investigated how shape and size variations in specimens affect the compressive strength of a specific UHPC, which is a proprietary mix containing 6% SFs by weight. Cylinders with diameters of 50, 75, and 100 mm (2, 3, and 4 inches) and a height-to-diameter ratio 2.0, along with cubes measuring 50 mm and 100 mm (2 and 4 inches), were tested. Results showed that smaller specimens had larger standard deviations compared to larger ones, leading to the recommendation against using specimens smaller than 75 mm. In a supplementary investigation, Graybeal and Davis17 further examined various sizes of UHPC cubes and cylinders. The specimen dimensions included 50, 75, and 100-mm cylinders and 50, 70, and 100-mm cubes, each sampled from three distinct mixtures. Two of these mixtures incorporated silica fume at a volume fraction of 2%, while the third did not contain any silica fume. The specimens underwent two different curing regimes. Cube and cylinder specimens were tested at 3, 4, 9, 27, and 28 days after casting, covering a range of 80–100 MPa compressive strengths. The researchers suggested conversion factors of 1.00 for the 100-mm cube and 0.96 for the 50-mm cube to derive the cylinder strength for 75-mm cylinders. The researchers proposed against using the 50-mm cube and cylinder specimens, since a greater variability was noticed in strength compared to larger sizes. Zabihi and Eren18 evaluated various UHPC specimens with different compressive strengths at 28 days of curing. The specimens included 100-mm, 150-mm, and 200-mm cubes, as well as 150 × 300 mm and 100 × 200 mm cylinders. The strength levels of UHPC were 54 MPa and 73 MPa, while the two curing conditions (air and water curing) were implemented. The cylinder-to-cube strength conversion factors exhibited a different trend under different curing regimes. This variation was attributed to the differing influence of the curing methods on the strength development. The details on the effect of curing regimes on the compressive strength of UHPC are available in an earlier study19. Fladr et al20. examined the conversion factors for various strength levels through tests on 150-mm and 100-mm cubes. The non-proprietary UHPC mixture was used, and specimens were tested at the age of 28 days. It was noticed that the conversion factor between the two cube sizes depended on the strength of the concrete. The strength ratio increased with compressive strength up to 140 MPa. After this threshold, the strength ratio stabilized and showed no variation with specimen size.

Zhang et al21. investigated the size effect of cube specimens on compressive strength. The study considered variables such as fiber type, fiber volume fraction, and water-to-binder ratio. Tested cube sizes included 40 mm, 70 mm, 100 mm, and 150 mm. Test results indicated that increasing the fiber volume fraction improved the compressive strength. Furthermore, the type of fiber also impacted how the size of the cube influenced its strength. Literature evidence suggests that specimens with a high compressive strength of 130 MPa or more exhibit a reduced size effect. However, achieving these high-strength levels in UHPC mixtures typically occurs at later ages. However, this does not apply to the 12-hour or one-day strength when bridge owners plan to open the structure. Literature suggests that conversion factors for 50-mm and 100-mm cubes to 75 mm cylinders are close to 1.00, which is accurate at later curing times or when the material has fully gained its strength. Nevertheless, such conversion factors are not available for UHPC mixtures’ 12-hour or one-day compressive strength. The bridge can only be considered operational once the field joint concrete strength reaches 95 MPa4,22, and using a factor of 1.00 at this level is not appropriate. In the initial phase of this study, the authors23 investigated whether new conversion factors are necessary across various UHPC strength levels. The preliminary study by the authors confirmed that a more detailed evaluation of the compression strength relationships between cubes and cylinders at different ages is required, especially for early ages. The results of a preliminary study by the authors24 indicated that the ASTM C107425 maturity method provides appropriate strength predictions for UHPC at ages greater than one day. However, the method exhibited limited reliability at the ages of one day or less when the ASTM C107425 recommendations are followed, since the method was developed primarily for conventional concrete rather than UHPC. For this reason, the authors made modifications in the maturity method to make it applicable to UHPC at both early and later ages, instead of implementing the standard specimens directly on UHPC. The early age mentioned in this study refers to ages less than three days. The Iowa DOT developmental specification DS-23,02922 for UHPC connections states that the bridge can be opened to traffic (including construction equipment) when the UHPC achieves compressive strength of 95 MPa. Similarly, the New York DOT also uses a 95 MPa compressive strength as a threshold4. The maturity study results from an earlier study by the authors26 are utilized and incorporated into the comparative assessment of UHPC cubes and cylinders within this study, as will be further explained.

Based on the summary above, there is a notable research gap in the literature on conversion factors for lower compressive strength or conversion factors that could be adopted for both early age strength and at all ages or strength levels. Furthermore, the published results advocate that UHPC mixture, volume fraction of fibers, curing regimes, and strength levels can significantly affect the conversion factors. Nevertheless, almost no previous studies, or at least recent ones, comprehensively considered a wide range of UHPC mixtures. Additionally, less literature is available dealing with the strength maturity method for UHPC at early ages and from a cube versus cylinder perspective. This research work builds on the preliminary findings by the authors23,26 and has the following objectives: (1) provide the fundamental understanding in terms of compressive behavior and trends of 50-mm and 100-mm cubes as alternative to 75-mm cylinders for UHPC quality control, (2) develop comprehensive conversion factors between cubes and the required standard ASTM cylinder size for UHPC for full range of early and late age and using comprehensive experimental datasets that covers wide spectrum of UHPC types for the first time, and (3) demonstrate the validity of using the strength maturity method for UHPC strength characterization using cubes instead of cylinders. The motivation is the implementation of cube specimens for quality control at on-site or remote construction sites.

In the current study, four different commercial (proprietary) and one non-proprietary UHPC mixtures were used along with varying SFs ratios (1% and 2% for some mixtures). A total of eight different UHPC mixtures were used to cover the full range of UHPC types and generalize the results. Approximately 900 UHPC specimens were sampled and subjected to two curing regimes, i.e., laboratory-cured and site-cured, and tested at different ages. The results cover the full compressive strength range of 7–140 MPa. The primary goal of the study is to establish reliable conversion factors for UHPC. This research also aims to propose a quality control method to predict the strength of UHPC at early ages by assessing and modifying the well-established method for conventional concrete, i.e., strength maturity. The outcomes of the study shall be helpful for researchers and practitioners to correlate the compressive strength of UHPC cubes and cylinders with different sizes and at different ages.

Materials and methods

Materials

Four different commercial (proprietary) UHPC mixtures, along with one non-proprietary mixture, were used in this study. The proprietary mixtures were obtained from four different vendors to represent UHPC products that are used worldwide, and the non-proprietary mixture was based on one of our previous studies1. The different mixtures and constituents are provided next, but the information on the locally sourced materials for the non-proprietary or semi-proprietary mixtures is as follows. ASTM Type-I cement27 was used as a binding material in two of the UHPC mixtures. The fine masonry sand was acquired from a local Reno, Nevada quarry (Q&D Construction Mustang28. The sand was oven-dried before using in the non-proprietary mixtures to avoid the sand’s moisture contribution to the water/binder ratio. The slag was sourced from Skyway Cement Company29. The admixtures were provided by Master Builders Solutions30. Accelerators were used in two of the UHPC mixtures. All UHPC mixtures were reinforced with either 1% or 2% SF by volume31,32,33. Manufactured SF of uniform properties (13 mm length, 0.2 mm diameter, 65 length-to-diameter aspect ratio, 7850 kg/m3 density, and 3000 MPa tensile strength) were obtained either through the UHPC vendors or from local providers in the US.

Mixture proportioning

The UHPC mixtures used in the current study were divided into five groups, i.e., UHPC Type A with 1% SFs, Type B with 1% and 2% SFs, Type C with 1% and 2% SFs, Type D with 2% SFs, and Type E with 2% SFs with and without accelerator (acc.). The mixture labels and the proportions of the different UHPC mixtures are listed in Table 1.

UHPC mixing and sampling

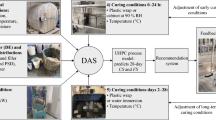

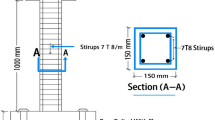

This study examines specimens of various shapes and sizes, including: (1) cylinders measuring Ø75 × 150 mm, referred to as 75-mm cylinders; (2) cubes measuring 100 mm on each side, called 100-mm cubes or 4 × 4 cubes; and (3) smaller cubes measuring 50 mm on each side, labeled as 50-mm cubes. For simplicity, the cube specimens of 50-mm and 100-mm size are referred to in this paper as small and large cubes, respectively. Figure 1 shows the UHPC mixing and sampling setup and illustrates the different specimens shapes and sizes. The figure also presents the installation of temperature sensors into the molds for the maturity study that was employed to predict the strength of UHPC as explained later. The maturity method is a non-destructive technique that utilizes embedded temperature sensors to correlate the strength of concrete or UHPC with the maturity index34. The measurement and tracking of the temperature of specimens were performed by using temperature sensors that represent wired and wireless technologies from three different vendors35,36,37.

All UHPC mixing, specimen sampling, and fabrication were performed using a high-shear mixer, as shown in Fig. 2. The figure illustrates the preparation process for one non-proprietary UHPC batch and shows how UHPC was placed into various molds for specimen fabrication. The UHPC specimens were categorized into two groups, i.e., lab-cured specimens and site-cured specimens. The lab-cured specimens underwent curing in standard laboratory conditions following the provisions of ASTM C51143 . However, the site-cured specimens were placed outdoors to emulate typical construction site conditions. The experimental program extended over 12 months, from winter through summer in Reno, Nevada, USA. During this period, ambient temperatures ranged from about − 7 °C in the winter (with snow) to about 30 °C in the summer. The UHPC mixtures were cast during different months of the year, resulting in batches produced under nearly all seasonal conditions in Reno. The site-cured specimens were left outside, while laboratory specimens were transported to the lab curing room after casting. Furthermore, some UHPC specimens were heated in an electric oven at 40 °C for approximately 12 hours. The curing of UHPC at elevated temperatures is a common strategy to accelerate early-age strength gain, particularly in accelerated bridge construction projects. For example, in one New York bridge project, an accelerated UHPC mix cured at 37 °C for 12 hours was found to provide the compressive strength needed to meet the 95 MPa opening-strength requirement for UHPC joints under live traffic4. This practice motivated to include a heated curing regime in the experimental program. The oven-cured specimens were used to (i) provide data for the conversion-factor functions developed in this study and (ii) support a companion study on the maturity method38, where the influence of elevated-temperature curing on UHPC strength development is investigated.

Specimens preparation and testing

One of the main challenges of using cylinders for determining early age strength and quality control is the need for careful cylinder preparation. The bottom and top surfaces of UHPC cylinders need to be ground to ensure parallelness and levelness before compression testing. The procedure of cutting and grinding a UHPC cylinder is depicted in Fig. 3. For the cubes, no specimen preparation is needed, as any two parallel surfaces of the cube other than the one side of casting can be used for the testing. Figure 4 illustrates axial compression testing of cubes and cylinders. The cylinder specimens were tested following the provisions of ASTM C39 39, while the specifications of ASTM C10940 were followed to test the cube specimens. Loading rates in accordance with the findings reported by Graybeal41 was used for the testing.

Compression test results and discussion

Compressive strength range and trends

The compressive strength value mentioned in this study is the average of three tested specimens. The statistical metrics from all compression tests are provided in Appendices A and B for lab-cured and site-cured specimens, respectively. The compressive strength development over age of the lab-cured different UHPC specimens tested at ages of 0.6, 0.7, 0.9, 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 days is first shown in Fig. 5. The results indicate that curing duration and type of UHPC mixtures affect the observed compressive strength of cylinder and cube specimens. The cylinder specimens from UHPC Type E2 exhibited the highest compressive strength of 157 MPa at a curing age of 28 days. The least 28-day cylinder compressive strength of 114 MPa was observed for the UHPC Type A mixture. Such values are noted for reporting purposes only and not to carry out any comparisons among different UHPC types. Overall, the specimens showed higher compressive strength as the curing age increased. The average values refer to the mean of three replicate specimens of the same shape at the same break age, following the provisions of ASTM C107425, which states that “Test two specimens at each age and compute the average strength. If the range of compressive strength of the two specimens exceeds 10% of their average strength, test another cylinder and compute the average of the three tests.” In the current study, this acceptance criterion was implemented not only for cylinders, but also for the large and small cubes. The testing ages for both lab and site specimens are listed in the appendix. For all specimen types (cylinders, large cubes, and small cubes), the compressive strength tests were conducted at ages ranging from 0.6 days to 28 days. However, small cube specimens exhibited a minor reduction in strength that was more skewed due to larger variability among specimens at later curing ages. The higher variability in the small cubes is mainly attributed to fiber distribution and orientation at the small specimen scale. No mechanical technique, such as magnets, was used to orient fibers in the small cubes, nor was it attempted to proportion the fibers individually for each small cube. Instead, the concrete was filled directly from the mixing drum using a shovel after the mixing process was completed.

The small volume of small cubes resulted in a non-uniform distribution of fibers within the replicates. Contrarily, the relatively large volume of cylinders and large cubes promoted more uniform fiber dispersion, resulting in reduced variability in measured strength. The skewed results refer specifically to the behavior of the small cubes (50 mm) at later ages. In several mixtures (for example, B2 and A at ages ≥ 3 days, and B1 at 7 days), the average strength of the small cubes dropped relative to the previous test age, even though compressive strength should theoretically be non-decreasing with time. The deviation from the strength gain trend is referred to as “skewed” results. At the curing age of 7-days, cylinder specimens achieved 74–90% of the 28-day compressive strength. The respective strength achievement for large and small cubes was in the range of 75–88% and 51–97%, respectively. The cylinders and large cubes made of UHPC Type C2 and Type D mixtures exhibited almost identical compressive strength at the curing age of 28-days.

The detailed compression test results of all cylinders and cubes are presented in Appendices A and B. The statistical metrics and conversion factors of cylinder and cube specimens at different curing ages. However, a simple summary of just the statistical metrics and key findings is listed in Table 2 for convenience. The table summarizes the values of standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and conversion factors for lab- and site-cured specimens of different sizes and shapes. The cube compressive strength of site-cured specimens exhibited a significant coefficient of variation (~ 19.5%). However, the coefficient of variation for compressive strength of cylinder specimens was 9.4%. A similar trend was recorded for lab-cured specimens. The values of conversion factors of site-cured large cube-to-cylinder, small cube-to-cylinder, and large cube-to-small cube were in the range of 0.96–1.23, 0.93–1.59, and 0.84–1.45, respectively. The respective conversion factor values for lab-cured specimens were 1.05–1.22, 0.91–1.43, and 0.82–1.49. The overall conversion factor values for large cube to cylinder, small cube to cylinder, and large cube to small cube were 1.15, 1.21, and 1.08, respectively.

Variation of cubes versus cylinder compressive strength

The cube and cylinder specimens were tested at a full range of early and late ages from 14 hours to 28 days. The tested specimens had a compressive strength ranging from below 7 MPa to over 140 MPa. Such a range significantly enriches and complements datasets in the literature. This section describes the effect of UHPC type and strength levels on conversion factors. The conversion factors between the cylinder specimens of size 75 mm and cubes of 50 mm and 100 mm sizes were developed and reported. The data recategorized and used here are part of the full test results presented in Appendix A and B for the lab-cured and site-cured specimens, respectively.

Effect of UHPC mixtures on conversion factors

Figure 6 illustrates how various UHPC mixtures influenced the conversion factor between cubes of different sizes and the standard cylinder. The conversion factors of large cube size (100-mm cubes) and small cube size (50-mm cubes) to standard 75-mm cylinders are depicted in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. The experimental results show that there is no constant or consistent ratio between the strength of cylinders and cubes. In other words, the conversion factors vary depending on the type and strength level of UHPC. At lower strength levels, significant discrepancies were recorded in conversion factors when converting 50-mm cube strength to 75-mm cylinders and 100-mm cubes. However, the discrepancies in conversion factors were reduced for a strength level of more than 60 MPa. Additionally, fewer inconsistencies were observed in the conversion between 100-mm cubes to 75-mm cylinders, where conversion factor values are closer to 1.0.

The influence of UHPC age and strength level on conversion factors

Figure 7 illustrates the correlation between the compressive strength of UHPC and conversion factors for individual testing sets in the form of a scatter plot. The x-axis represents the strength range based on large and small cubes, while the y-axis indicates the respective conversion factors of large cubes to cylinders (Fig. 7a), small cubes to cylinders (Fig. 7b), and small cubes to large cubes (Fig. 7c). At lower strength values, a large variation in the values of conversion factors can be observed from the figures. The discrepancies were more evident for conversion factors of a small cube to a cylinder and a small cube to a large cube. However, the discrepancies in the conversion factor values are reduced when the compressive strength reaches higher levels (greater than 60 MPa).

Conversion factors

The data points from different UHPC types, ages, and curing regimes were combined, and the method of least squares was implemented. This was done to eliminate the effect of UHPC mixture type and strength age (maturity) variabilities on the cube and cylinder correlations. Furthermore, this approach facilitated the generalization of the study’s results. The different functions were used to correlate the cylinder and cube compressive strength. The function used in the regression analysis comprised (1) a linear function with an intercept, (2) a linear function without an intercept, (3) a power function, (4) a hinge function with an intercept, and (5) a hinge function without an intercept. As illustrated in (Figures 8, 9, 10), these multi-slope models can increase the coefficient of determination \(( R^2 )\) slightly; however, it also requires multiple expressions and hinge points, which makes it more complicated for practical use. The multi-slope linear function plots and the respective “error” plots are also added (see Figs. 11, 12 and 13), where the vertical axis represents the ratio fc, exp/fc, pred as a function of predicted strength for the proposed conversion models between 50 × 50 mm cubes, 100 × 100 mm cubes, and 75 × 150 mm cylinders. The horizontal line at fc, exp/fc, pred=1.0 corresponds to perfect agreement. The values below 1.0 indicate overprediction (unconservative), whereas values above 1.0 indicate underprediction (conservative). The red and green background bands highlight the unconservative and conservative regions, respectively. The fitted conversion equation and coefficient of determination (R) are reported in the plots. The plots indicate a slightly better fit for the piecewise models. However, the improvement in strength prediction is modest. Therefore, it was concluded that the additional complexity is not justified. Therefore, a power regression model as an alternative to a non-linear model was adopted.

The statistical significance of each conversion model was evaluated by conducting a statistical analysis. For every linear and power function, an ordinary least squares regression was fitted and hypothesis tests were performed on each regression coefficient (intercept \(\:{B}_{0}\)and slope \(\:{B}_{1}\)). The statistical significance of each regression coefficient was assessed using the standard t-tests from ordinary least squares linear regression42. For each coefficient, the null hypothesis \(\:{H}_{0}:\beta\:=0\) was tested against the alternative \(\:{H}_{1}:\beta\:\ne\:0\), and the corresponding p-values are presented in Table 3. Following common practice, coefficients with p-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant42. Table 3 summarizes the p-values for all coefficients in the conversion functions . For each conversion (50-mm cubes to 100-mm cubes, 50-mm cubes to 75-mm cylinders, and 100-mm cubes to 75-mm cylinders), the functional form and the p-values for the intercept and slope are listed. As shown in this table, all regression slopes and intercepts exhibited a p-value less than 0.05, signifying that these coefficients are statistically significant. The only non-significant coefficient occurs in the power function for the 50-mm cube to 75-mm cylinder conversion (p = 0.733). This simply means that the data do not provide strong evidence that the multiplicative factor in this power model (1.04) is different from 1.

The power function exhibits a higher R2 value relative to those of linear regression functions for all three conversions. The higher R2 values for cube-to-cylinder conversion confirm the robustness of the proposed conversion procedure and advocate the use of cube specimens as an alternative to cylinders, especially for quality control and early age strength when the cylinder’s surface preparation is challenging and could affect the compressive strength39,40. This is also time-effective and viable for on-site operation, where the handling of cube specimens is relatively much easier than cylinders. For construction site applications, a practical factor of safety was calibrated from the experimental data. For each conversion equation, the ratio between the experimental strength and the predicted strength was computed and plotted \(\:{r}_{i}\)versus the predicted strength.

This ratio plot allows to quantify how much the regression overestimates or underestimates the measured strength across all tests. Afterward, the empirical 5th and 10th percentiles of \(\:{r}_{i}\) evaluated and plotted as illustrated in Fig. 14. The ratio of experimentally measured to predicted compressive strength, fexp/fpred, versus predicted strength for the selected conversion equations between 50 × 50 mm cubes, 100 × 100 mm cubes, and 75 × 150 mm cylinders. The solid horizontal line at fexp/fpred=1.0 denotes perfect agreement, while the dashed and dotted lines indicate the 5th and 10th percentiles of fexp/fpred, respectively. The red band marks the lower 10% of the ratios (most unconservative cases), and the green band covers the remaining 90% of the data. These plots are used to evaluate the reliability and conservatism of the proposed conversion expressions. Since the design practices adopt conservative material strength rather than overestimation, the 10th percentile of this ratio was adopted as a reduction factor \(\:{{\Phi\:}}_{10}\)for each equation. The corresponding design conversion is then defined as follows:

Table 4 presents the original functions with 10th-percentile reduction factors. For clarity, the design equations are presented in the form \(\:{{\Phi\:}}_{10}\times\:\text{Function}\). These revised equations provide explicit guidance to end users and incorporate a consistent, statistically based factor of safety that addresses the concern about possible overestimation and early opening.

Error curves using linear with and without intercept and power function: (a) 50-mm cubes to 100-mm cubes; (b) 50-mm cubes to 75 × 150 mm cylinders; (c) 100-mm cubes to 75 × 150 mm cylinders (fexp=experimental strength, fpred=predicted strength, f75 = 75 × 150 mm cylinder strength, f100 = 100 × 100 mm cube strength, f50 = 50 × 50 mm cube strength).

Application and validation of conversion factors: strength maturity

Maturity method

The high early-age strength development for closure joints in accelerated construction projects is crucial. The practitioners need to verify the achievement of the required UHPC strength as early as 12 hours post-casting. This quality control can be effectively managed through the maturity method. The maturity method allows for accurate, non-destructive prediction of concrete strength based on temperature history, ensuring that project specifications are met. It is a well-established technique for traditional concrete. ASTM C107425 provides standards and guidelines for predicting concrete strength via the maturity method. Additionally, there have been reports of the method being explored or applied to estimate the early-age strength of UHPC mixtures24,34. For practical applications, the UHPC should be prepared and cast into cylindrical specimens with a standard diameter of 75 mm10 , then cured under laboratory conditions. These cylindrical specimens are to be subjected to compressive testing at curing ages of 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 days, with their respective maturity indices corresponding to each specimen. The maturity index of each specimen is associated with its temperature history, recorded via temperature sensors positioned at the midpoint height of the cylinders at the time of casting. ASTM C107425 delineates two maturity functions: (i) the Nurse-Saul function (NS), also known as the time-temperature factor, and (ii) the Arrhenius function, or Equivalent Age (EQ), for computation of the maturity index. The NS maturity function assumes a linear relationship between temperature and the rate of strength development, as described in Eq. 3.

Where Ta represents the average concrete temperature during the time interval, To is the reference temperature, and M(t) denotes the temperature-time factor at age t. In contrast, the EQ function represents a non-linear relationship between temperature and strength development, as shown in Eq. 4.

where te indicates the equivalent age at a specified temperature Ts, Q is activation energy divided by the gas constant 8.13 J/(K.mol), and Ta is the average concrete temperature during time interval \(\:\varDelta\:t\).

Sensors data and comparative temperature histories of cubes and cylinders

A sample of the recorded temperature history curves of lab-cured specimens is depicted in Fig. 15. There was an insignificant variation in the temperature of specimens irrespective of the type of UHPC mixture. A zoomed-in view of the temperature variations of cube and cylinder specimens up to the curing age of 2 days is also demonstrated in Fig. 15. For the same UHPC mixtures, the temperature curves exhibited similar trends irrespective of the specimens’ shapes and sizes. No significant variation in temperature history was recorded, irrespective of UHPC mixture types, after a curing age of 1.2 days. For completeness, sample temperature history curves of site-cured cubes and cylinders are also shown in Fig. 16. The temperature curves exhibited almost sinusoidal behavior irrespective of the specimens’ shapes and sizes. The small cubes exhibited the highest temperature peaks at different ages of curing. Furthermore, cylinders and large cubes exhibited similar temperature variations at the same age of curing.

To examine the temperature variation based on UHPC mixtures and types, the temperature history of site-cured 50-mm cube specimens was also recorded, as illustrated in Fig. 17. There was a variation in temperature history for different UHPC types. An initial drop in temperature is seen for all specimens except UHPC Type E2. The highest and the lowest temperature peak values were recorded for cubes made with the UHPC Type A mixture and the UHPC Type C mixture, respectively.

Application of maturity method

After the calculation of the maturity indexes of lab-cured cylinders and matching the indexes with the compressive strength of the cylinders, the maturity index and strength point could be plotted, and logarithmic curve fitting could be applied to generate the strength-maturity curves. The strength maturity curves of the tested UHPC can then be used in construction sites for that UHPC type. The strength-maturity curves will be used as input parameters in the maturity sensors so that practicing engineers can be notified when the UHPC has achieved a certain strength. This could be possible since the maturity indexes of UHPC structural members at the construction site will be calculated based on the temperature history of the structural member. Although the site engineers cannot remove the formwork based on strength prediction by maturity curves, it could indicate that UHPC has reached a certain strength level. The provisions of ASTM C107425 requires that maturity-based strength estimates be verified using companion testing before critical operations, for example by testing field-molded cylinders cured in accordance with ASTM C3144 and comparing measured strengths with those estimated from the established strength–maturity relationship. For UHPC, compressive strength testing is performed in accordance with ASTM C3939 as modified by ASTM C1856 10 which specifies 75 mm cylinders.. The construction engineers could use maturity curves for UHPC structural elements if the results of the compression test match the maturity curve prediction. As noted before, the compression testing of cylinder specimens requires surface preparation that includes cutting and grinding, and is not always possible on-site or feasible for remote construction sites. Furthermore, the surface preparation process of cylinders might influence the strength due to strength concentrations, thereby causing discrepancies in strength, especially at an early age39,40.

Considering the limitations associated with cylinder surface preparation, the authors recommend the use of large cubes as an alternative. However, design codes and specifications of some countries require cylinder strength for quality control purposes, which highlights the importance of robust conversion factors. Hence, the authors suggest the application of the strength-maturity method for UHPC quality control through either of two approaches:

-

(i)

The cubes can be employed in the entire maturity method, i.e., the strength-maturity curves can be developed in the lab using cube specimens. Furthermore, cubes can be cast along with UHPC structural members at construction sites and assessed directly against the developed curves. Meanwhile, the tested cubes strength can be converted into cylinder strength using the proposed conversion factors, if needed.

-

(ii)

The second approach involves the development of strength-maturity curves in the laboratory using cylinders as might be required by some specifications. Afterwards, the quality control of UHPC at construction sites can be ensured using cube specimens. The cubes strength will be obtained, then converted into cylinder strength using the conversion factors before assessing such site strength points against the developed lab curves.

The two approaches above are investigated and presented herein for demonstration purposes as well as validation of the developed and proposed conversion functions. A comprehensive study was conducted on the maturity method using both 75-mm cylinders and 100-mm cubes. The NS and EQ maturity functions were employed. The authors observed that 100-mm cubes yielded a better strength prediction at early ages34,39. The case study in this section illustrates the application of conversion factors using four different UHPC mixtures for further generalization and validation.

The investigation started with the development of four strength-maturity relationships in the laboratory using the 75-mm cylinders for the four different UHPC mixtures, as illustrated in Fig. 18. The figure shows the individual test points as well as the developed maturity curve (grey line). The curing of lab-cured specimens was performed following the provisions of ASTM C51143 . The strength-maturity correlation for each UHPC mixture was developed by employing the Piecewise Linear Method that was proposed by the authors in an earlier study38.

The cylinder and cube specimens were subjected to laboratory and site curing regimes. The lab-cured specimens were placed inside the laboratory, while the site-cured specimens were placed outside the laboratory to represent typical ambient site conditions. The temperature variations of lab-cured and site-cured specimens were measured using wired and wireless temperature sensors from three different providers. Different sensor technologies were used to ensure that the presented results and conclusions are independent of specific technology or method and can be generalized. The site-cured specimens were tested for different curing ages starting as early as 14 h. The results of the site-cured cylinder and cube specimens are plotted and depicted in Fig. 18. The strength-maturity relationship is shown by a grey line, and the actual site 75 × 150 mm cylinders and the actual site 100 × 100 mm cubes are plotted as a red hollow circle and green hollow square, respectively. The final developed and proposed conversion functions 1.2x and 0.8 × 1.1 (see Table 3 for 100-mm cube to 75-mm cylinder conversion) were adopted as shown in Fig. 18. It is observed that the function of 1.2x exhibited good results for UHPC Type C. However, the function 1.2x led to an overestimation of the compressive strength of cylinders of UHPC Type A, B, and D. However, the function 0.8 × 1.1 yielded good results for UHPC type A, B, and D. However, the compressive strength of UHPC Type C was conservatively predicted by function 0.8 × 1.1. Such observations indicate that, within acceptable accuracy, cube specimens can be used at construction sites. Additionally, the conversion factors can effectively be used to convert cube compressive strength to cylinder strength. The function 0.8 × 1.1 is shown to provide better prediction results and the least error within the 10% ASTM acceptable range, but only for the very early age strength.

Validation of the conversion factors

The proposed conversion factors are applied within the ASTM C1074 25maturity framework. For each UHPC mixture, 100 mm cubes and 75 mm cylinders were instrumented with embedded maturity sensors (see Fig. 1) to record the internal temperature history (see Figs. 15, 16 and 17). Using this data, the Nurse–Saul maturity index “M (t)” was calculated with a datum temperature of − 2 °C38 , and compressive strengths were measured at approximately 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 days in accordance with ASTM C107425.

At each age, the measured strength was paired with the corresponding maturity index, and these strength–maturity pairs were fitted with the ASTM C107425 recommended logarithmic relationship to obtain strength–maturity curves for each specimen geometry. In Fig. 19, the solid black curves represent the strength–maturity curves derived directly from cylinder test data, while the solid grey curves represent curves derived directly from cube test data. For the curves, the cube strengths were first converted to equivalent cylinder strengths using the proposed conversion factors (1.2x and 0.8x¹·¹), and the same logarithmic fit was then applied to these converted values. Comparison with the cylinder-based maturity curves confirms that cube-based maturity data, combined with the linear regression function: 1.2x conversion, can reproduce the cylinder strength development with good accuracy over the early-age range of interest. The power-law conversion (0.8x¹·¹) tends to underestimate the cylinder strength when combined with the ASTM logarithmic fitting, but this underestimation is conservative from a quality-control standpoint and therefore acceptable and even preferable when a safer estimate is desired.

Conclusions

This study aimed to examine the effect of cube size versus cylinders on the compressive strength of UHPC and to develop robust conversion factors that can correlate the cube’s strength to standard cylinder compressive strength. A total of about 900 specimens were prepared and tested at varying curing ages and strength levels. To generalize the results, eight different UHPC mixtures, varying SF ratio, and different curing regimes were considered while developing the conversion factors. The full dataset is provided in the Appendices for future use. The study also investigated the application of cubes and the validity of the developed conversion factors for UHPC strength maturity using both the standard ASTM method as well as another fitting procedure previously proposed by the authors38 . The main conclusions and recommendations of the study are as follows:

-

The 50-mm cubes exhibit significant discrepancies, large variations, and inconsistent results in strength determination at low strength levels (early ages), even after conversion to equivalent 100-mm cube and 75-mm cylinder strengths. Thus, using 50-mm cubes for UHPC quality control at early ages with strengths below 60 MPa is not advisable.

-

Low discrepancies and more consistency are observed when directly using 100-mm cubes or converting 100-mm cube strength to equivalent 75-mm cylinder at any age for all strength levels. Therefore, it is recommended to use 100-mm cubes as a possible alternative for cylinders to assess UHPC strength at any age and for quality control purposes.

-

The strength maturity method can be effectively used for UHPC, and the proposed conversion factors are validated to use lab and site cube strength breaking points. Comparison with the cylinder-based maturity curves confirms that cube-based maturity data, combined with the linear regression function: 1.2x conversion, can reproduce the cylinder strength development with good accuracy over the early-age range of interest. The power-law conversion (0.8x¹·¹) tends to underestimate the cylinder strength when combined with the ASTM logarithmic fitting, but this underestimation is conservative from a quality-control standpoint and therefore acceptable and even preferable when a safer estimate is desired.

-

For construction site applications, a practical factor of safety was calibrated from the experimental data. The 10th percentile of the ratio (fc, exp, i/fc, pred, i) was taken as a reduction factor. The implementation of the factor of safety avoids the risk of overestimation of the UHPC strength at the early ages.

-

The proposed conversion factors cover the full range of proprietary and non-proprietary UHPC blends with a full range of compressive strength levels at early and later ages. Therefore, the proposed conversion factors can be readily implemented and effectively used by researchers and practitioners to predict the cylinder compressive strength from cube specimens.

Appendix A

Summary of compression test results of lab-cured specimens.

Time [day] | Comp. Strength [MPa] | St. Deviation [MPa] | Coeff. of Variation [%] | Conversion Factors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

cyl. | cube size1 | cube size 2 | cyl. | cube size1 | cube size 2 | cyl. | cube size1 | cube size 2 | cu1 to cyl. | cu2 to cyl. | cu1 to cu2 | |

UHPC Type A – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 16.0 | 18.5 | 13.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 1.18 | 1.37 |

0.7 | 29.1 | 29.4 | 18.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 8.4 | 0.99 | 1.56 | 1.57 |

0.9 | 33.2 | 27.4 | 32.2 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 8.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 1.21 | 1.03 | 0.85 |

1 | 47.3 | 42.9 | 44.8 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 0.96 |

2 | 68.4 | 55.1 | 36.4 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 1.24 | 1.88 | 1.51 |

3 | 83.0 | 67.7 | 42.6 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 18.9 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 1.23 | 1.95 | 1.59 |

7 | 97.4 | 69.5 | 66.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 1.40 | 1.47 | 1.05 |

14 | 104.2 | 81.2 | 80.8 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 14.4 | 33.3 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.00 |

28 | 114.1 | 89.7 | 79.8 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 66.7 | 5.2 | 53.5 | 1.27 | 1.43 | 1.12 |

Mean values: | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 12.2 | 5.6 | 12.7 | 1.18 | 1.43 | 1.22 | |||

UHPC Type B – 1% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 8.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.00 | 1.92 | 1.92 |

0.7 | 28.1 | 33.4 | 15.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 0.84 | 1.86 | 2.21 |

0.9 | 51.9 | 48.6 | 47.1 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 11.4 | 15.6 | 9.8 | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.03 |

1 | 60.0 | 52.0 | 57.1 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 17.9 | 9.7 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 0.91 |

2 | 73.1 | 72.9 | 78.5 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 3.6 | 8.7 | 0.9 | 26.6 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

3 | 93.1 | 71.4 | 83.8 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 6.1 | 37.0 | 1.6 | 78.2 | 1.30 | 1.11 | 0.85 |

7 | 107.4 | 81.5 | 57.9 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 14.5 | 1.32 | 1.85 | 1.41 |

14 | 122.0 | 93.8 | 90.9 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 37.6 | 6.2 | 1.30 | 1.34 | 1.03 |

28 | 136.6 | 92.6 | 113.4 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 10.0 | 32.0 | 5.8 | 1.48 | 1.20 | 0.82 |

Mean values: | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 9.0 | 12.8 | 16.9 | 1.16 | 1.38 | 1.23 | |||

UHPC Type B – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 25.9 | 48.5 | 10.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.53 | 2.44 | 4.58 |

0.7 | 48.7 | 52.0 | 29.5 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 26.8 | 16.2 | 6.9 | 0.94 | 1.65 | 1.76 |

0.8 | 61.5 | 56.2 | 37.6 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 21.6 | 12.5 | 5.6 | 1.09 | 1.64 | 1.49 |

1 | 63.1 | 66.0 | 58.6 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 26.5 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 1.13 |

2 | 84.0 | 65.3 | 81.9 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 44.9 | 38.6 | 1.29 | 1.03 | 0.80 |

3 | 90.6 | 82.7 | 102.4 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 24.5 | 80.7 | 114.6 | 1.10 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

7 | 107.5 | 80.0 | 94.8 | 4.8 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 47.4 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 1.34 | 1.13 | 0.84 |

14 | 123.5 | 87.3 | 83.7 | 7.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 131.8 | 2.0 | 5.7 | 1.41 | 1.48 | 1.04 |

28 | 134.0 | 96.6 | 105.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 7.5 | 24.1 | 22.8 | 117.2 | 1.39 | 1.27 | 0.92 |

Mean values: | 3.5 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 34.1 | 20.7 | 33.0 | 1.12 | 1.40 | 1.49 | |||

UHPC Type C – 1% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 7.2 | 10.8 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.67 | 1.47 | 2.19 |

0.7 | 11.0 | 12.2 | 7.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.90 | 1.42 | 1.58 |

0.9 | 27.7 | 22.5 | 15.7 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 8.7 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.23 | 1.76 | 1.43 |

1 | 63.6 | 67.2 | 48.4 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 55.8 | 25.8 | 21.8 | 0.95 | 1.31 | 1.39 |

2 | 105.8 | 93.5 | 90.6 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 25.7 | 48.7 | 4.7 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 1.03 |

3 | 111.0 | 87.3 | 88.0 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 47.4 | 76.9 | 21.4 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 0.99 |

7 | 109.0 | 91.9 | 78.2 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 13.9 | 16.0 | 41.6 | 1.19 | 1.39 | 1.18 |

14 | 122.8 | 102.4 | 86.5 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 4.6 | 31.2 | 12.2 | 43.9 | 1.20 | 1.42 | 1.18 |

28 | 147.7 | 119.2 | 111.5 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 68.8 | 111.2 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.07 |

Mean values: | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 21.1 | 27.9 | 27.3 | 1.09 | 1.39 | 1.34 | |||

UHPC Type C – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 27.1 | 34.4 | 33.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 11.6 | 16.7 | 14.7 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 1.03 |

0.8 | 39.3 | 46.6 | 37.9 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 18.6 | 2.4 | 15.0 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 1.23 |

0.9 | 66.0 | 54.8 | 62.6 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 26.6 | 4.4 | 52.5 | 1.20 | 1.05 | 0.87 |

1 | 94.8 | 63.2 | 92.8 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 27.3 | 12.6 | 11.0 | 1.50 | 1.02 | 0.68 |

2 | 111.8 | 83.9 | 102.9 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 4.6 | 19.2 | 2.3 | 43.9 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 0.82 |

3 | 112.1 | 79.6 | 104.4 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 17.2 | 3.7 | 15.2 | 1.41 | 1.07 | 0.76 |

7 | 126.9 | 96.7 | 105.8 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 39.7 | 2.0 | 1.31 | 1.20 | 0.91 |

14 | 134.0 | 103.2 | 117.2 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 11.8 | 26.9 | 26.3 | 1.30 | 1.14 | 0.88 |

28 | 140.3 | 115.8 | 141.7 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 38.7 | 42.4 | 59.7 | 1.21 | 0.99 | 0.82 |

Mean values: | 2.9 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 19.5 | 16.8 | 26.7 | 1.21 | 1.05 | 0.89 | |||

UHPC Type D – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

0.9 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.79 |

1 | 9.4 | 11.3 | 15.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.73 |

1.5 | 57.8 | 54.2 | 61.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 8.7 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

2 | 72.3 | 56.3 | 68.1 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 14.8 | 34.3 | 24.8 | 1.28 | 1.06 | 0.83 |

3 | 86.1 | 62.4 | 81.5 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 31.9 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 1.38 | 1.06 | 0.77 |

7 | 106.1 | 90.1 | 103.3 | 3.0 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 18.4 | 91.9 | 55.2 | 1.18 | 1.03 | 0.87 |

14 | 136.2 | 112.8 | 129.6 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 5.4 | 13.4 | 10.5 | 1.21 | 1.05 | 0.87 |

28 | 141.5 | 118.4 | 143.1 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 67.8 | 56.3 | 21.2 | 1.20 | 0.99 | 0.83 |

Mean values: | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 17.8 | 25.2 | 15.2 | 1.11 | 0.91 | 0.82 | |||

UHPC Type E1 – 2% steel fibers without accelerator | ||||||||||||

1 | 2.9 | 4.9 | 7.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.69 |

2 | 59.3 | 52.3 | 55.3 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 16.5 | 1.5 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 0.95 |

3 | 78.8 | 71.0 | 64.8 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 31.2 | 1.11 | 1.22 | 1.10 |

7 | 115.4 | 93.4 | 107.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 1.24 | 1.08 | 0.87 |

15 | 124.5 | 113.9 | 103.8 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 18.6 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 1.09 | 1.20 | 1.10 |

28 | 143.8 | 124.0 | 115.6 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 8.2 | 2.0 | 48.9 | 141.7 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.07 |

Mean values: | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 11.6 | 29.5 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 0.96 | |||

UHPC Type E2 – 2% steel fibers with accelerator | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 0.95 |

0.8 | 22.8 | 18.7 | 14.2 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.22 | 1.61 | 1.32 |

1 | 42.3 | 39.4 | 36.7 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 7.0 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 1.07 | 1.15 | 1.07 |

1.2 | 53.1 | 42.1 | 46.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 1.26 | 1.15 | 0.91 |

2 | 92.1 | 71.0 | 92.7 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 12.1 | 0.2 | 21.3 | 1.30 | 0.99 | 0.77 |

3 | 100.0 | 83.9 | 103.2 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 22.5 | 0.0 | 32.1 | 1.19 | 0.97 | 0.81 |

7 | 128.9 | 95.9 | 110.0 | 0.9 | 6.0 | 9.1 | 1.9 | 74.4 | 172.3 | 1.34 | 1.17 | 0.87 |

14 | 149.9 | 118.1 | 138.1 | 2.5 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 12.9 | 168.0 | 176.9 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 0.85 |

28 | 156.8 | 127.4 | 113.3 | 6.5 | 0.6 | 8.6 | 87.8 | 0.8 | 154.8 | 1.23 | 1.38 | 1.12 |

Mean values: | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 16.1 | 27.7 | 63.0 | 1.22 | 1.17 | 0.96 | |||

Overall Mean: | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 16.8 | 18.5 | 28.0 | 1.14 | 1.22 | 1.11 | |||

Appendix B

Summary of compression test results of site-cured specimens.

Time [day] | Comp. Strength [MPa] | St. Deviation [MPa] | Coeff. of Variation [%] | Conversion Factors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

cyl. | cube size1 | cube size 2 | cyl. | cube size1 | cube size 2 | cyl. | cube size1 | cube size 2 | cu1to cyl. | cu2 to cyl. | cu1 to cu2 | |

UHPC Type A – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

2 | 74.2 | 52.6 | 47.5 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 11.4 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 1.41 | 1.56 | 1.11 |

3 | 73.3 | 70.8 | 37.9 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 14.1 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 1.04 | 1.93 | 1.87 |

7 | 89.7 | 80.2 | 69.9 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 20.1 | 91.5 | 47.7 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 1.15 |

Mean values: | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 15.2 | 32.4 | 17.9 | 1.19 | 1.59 | 1.38 | |||

UHPC Type B – 1% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

1 | 66.6 | 63.2 | 63.6 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 16.8 | 26.5 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.99 |

2 | 82.3 | 70.8 | 78.2 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 17.4 | 45.7 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.91 |

3 | 89.0 | 81 | 74.8 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 0.3 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 1.08 |

Mean values: | 0.7 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 13.3 | 24.2 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.99 | |||

UHPC Type B – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

1 | 73.1 | 54.8 | 53.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 6.7 | 9.2 | 23.0 | 1.33 | 1.37 | 1.03 |

2 | 76.4 | 66.4 | 76.9 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 35.0 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 1.15 | 0.99 | 0.86 |

3 | 89.0 | 74.1 | 90.8 | 0.2 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 59.6 | 29.0 | 1.20 | 0.98 | 0.82 |

Mean values: | 2.0 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 13.9 | 29.2 | 23.6 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 0.90 | |||

UHPC Type C – 1% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

1 | 42.2 | 48.2 | 24.7 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 31.3 | 29.2 | 0.1 | 0.88 | 1.71 | 1.95 |

2 | 77.2 | 75.4 | 57.9 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 37.6 | 1.02 | 1.33 | 1.30 |

3 | 90.0 | 80 | 73.8 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 61.8 | 1.13 | 1.22 | 1.08 |

Mean values: | 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 12.0 | 11.6 | 33.2 | 1.01 | 1.42 | 1.45 | |||

UHPC Type C – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

1 | 72.2 | 53.8 | 62.2 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 22.1 | 18.7 | 19.8 | 1.34 | 1.16 | 0.87 |

2 | 91.7 | 71.1 | 85.7 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 6.2 | 9.2 | 11.7 | 1.29 | 1.07 | 0.83 |

3 | 101.0 | 72 | 81.9 | 0.5 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 58.3 | 13.5 | 1.40 | 1.23 | 0.88 |

Mean values: | 1.8 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 9.6 | 28.7 | 15.0 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 0.86 | |||

UHPC Type D – 2% steel fibers | ||||||||||||

3 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 9.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.52 | 0.85 | 0.56 |

8 | 53.0 | 40 | 36.2 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 1.32 | 1.46 | 1.10 |

28 | 82.4 | 67.5 | 58.9 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 11.2 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 1.22 | 1.40 | 1.15 |

Mean values: | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 3.7 | 5.4 | 1.35 | 1.24 | 0.94 | |||

UHPC Type E1 – 2% steel fibers without accelerator | ||||||||||||

0.6 | 6.5 | 7 | 8.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.81 |

0.8 | 34.4 | 38.3 | 36.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 12.6 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 1.05 |

1 | 35.8 | 40.1 | 40.6 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.99 |

2 | 47.3 | 47.7 | 50.8 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

3 | 55.1 | 59.7 | 52.9 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 10.0 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 1.13 |

7 | 72.0 | 71.8 | 61.2 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 8.0 | 21.8 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 1.17 |

15 | 84.6 | 88.8 | 81.3 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 23.0 | 98.8 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.09 |

28 | 102.5 | 93.3 | 84.7 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 60.4 | 60.1 | 7.3 | 1.10 | 1.21 | 1.10 |

Mean values: | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 13.7 | 18.7 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.04 | |||

UHPC Type E2 – 2% steel fibers with accelerator | ||||||||||||

1 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.27 | 0.56 | 0.44 |

2 | 21.2 | 16.9 | 25.4 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 1.25 | 0.84 | 0.67 |

3 | 47.1 | 44.3 | 44.5 | 2.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 15.8 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.00 |

7 | 79.4 | 68.2 | 73.1 | 1.3 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 39.8 | 0.0 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 0.93 |

14 | 90.5 | 87.6 | 87.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 86.3 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.00 |

29 | 96.0 | 96.3 | 96.3 | 0.6 | 6.6 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 92.1 | 7.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Mean values: | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 6.0 | 24.2 | 16.7 | 1.13 | 0.93 | 0.84 | |||

Overall Mean: | 1.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 9.4 | 19.6 | 19.3 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.05 | |||

Data availability

The data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abokifa, M. & Moustafa, M. A. Mechanical characterization and material variability effects of emerging non-proprietary UHPC mixes for accelerated Bridge construction field joints. Constr. Build. Mater. 308, 125064 (2021).

Abokifa, M. & Moustafa, M. A. Experimental behavior of precast Bridge deck systems with Non-Proprietary UHPC transverse field joints. Mater. Basel Switz. 14, 6964 (2021).

Swenty, M. K. & Graybeal, B. A. Characterization of materials used in field-cast precast concrete connections. PCI J. 62 (5), 33–44 (2017).

Royce, M. Utilization of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) in New York. Int. Interact. Symp. Ultra-High Perform. Concr. Pap. 1, (2016).

Swenty, M. & Graybeal, B. A. Characterization of Materials Used in Precast Bridge Element Connections, PCI National Bridge Conference, (2011).

Tazarv, M. & Saiidi, M. S. Next generation of Bridge columns for accelerated Bridge construction in high seismic zones. (2014). https://trid.trb.org/View/1410827

Akeed, M. H. et al. Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Part IV: durability properties, cost assessment, applications, and challenges. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01271 (2022).

Azmee, N. M. & Shafiq, N. Ultra-high performance concrete: from fundamental to applications. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 9, e00197 (2018).

Aboukifa, M. & Moustafa, M. A. Structural and buckling behavior of full-scale slender UHPC columns. Eng. Struct. 255, 113928 (2022).

ASTM C1856. Standard Practice for Fabricating and Testing Specimens of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024).

BS EN 12390-. 1:2021 – Testing Hardened concrete – Part 1: Shape, Dimensions and Other Requirements for Specimens (British Standards Institution, 2021).

50107 – 2010, G. B. T. GB/T 50107 – 2010 Standard for Evaluation of Concrete Compressive Strength (English Version) - Code (China Architecture & Building,2010 ).

Choi, D., Hong, K., Ochirbud, M., Meiramov, D. & Sukontaskuul, P. Mechanical properties of Ultra-High performance concrete (UHPC) and Ultra-High performance Fiber-Reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) with recycled sand. Int. J. Concr Struct. Mater. 17, 67 (2023).

Alsaif, A., Fares, G. & Alhozaimy, A. Effectiveness of ultra-high-performance concrete containing recycled tire steel fibers and high-volume scoria rock powder as natural Pozzolan. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03841 (2024).

Mansur, M. A. & Islam, M. M. Interpretation of concrete strength for nonstandard specimens. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 14, 151–155 (2002).

Graybeal, B. A. Material Property Characterization of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. (2006). https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov

Graybeal, B. & Davis, M. Cylinder or cube: strength testing of 80 to 200 MPa (11.6 to 29 ksi) Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced concrete. ACI Mater. J. 105, 603–609 (2008).

Zabihi, N. & Eren, O. Compressive strength conversion factors of concrete as affected by specimen shape and size. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 7, 4251–4257 (2014).

Hamada, H., Alattar, A., Tayeh, B., Yahaya, F. & Almeshal, I. Influence of different curing methods on the compressive strength of ultra-high-performance concrete: A comprehensive review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01390 (2022).

Fládr, J. & Bílý, P. Specimen size effect on compressive and flexural strength of high-strength fibre-reinforced concrete containing coarse aggregate. Compos. Part. B Eng. 138, 77–86 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. Size effect of ultra-high-performance concrete under compression: effects of steel fiber characteristics and water-to-binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 330, 127170 (2022).

Iowa Department of Transportation (Iowa DOT). Developmental Specifications for Ultra High Performance Concrete Connections (DS-23029) (Iowa Department of Transportation, 2023).

Ibrahim, M. S. & Moustafa, M. A. UHPC Compressive Strength Conversion Factors: Cubes versus Cylinders. Int. Interact. Symp. Ultra-High Perform. Concr. Pap. 3, (2023).

Ibrahim, M. S. & Moustafa, M. A. Robust Methods for UHPC Early-Strength Determination and Quality Control for ABC. (2022). https://trid.trb.org/View/2534054

ASTM C1074. Standard Practice for Estimating Concrete Strength by the Maturity Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, (2019).

Ibrahim, M. S. & Moustafa, M. A. Assessment and Development of Maturity Method for UHPC Quality Control. Int. Interact. Symp. Ultra-High Perform. Concr. Pap. 3, (2023).

ASTM C150/150 M-24. Standard Specification for Portland Cement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, (2024).

Mustang Quarry and Hot Plant. https://qdconstruction.com/materials/mustang/

Skyway Slag Cement. https://www.skywaycement.com/

Master Builders Solutions Home Page. North America https://www.master-builders-solutions.com/en-us

UHPC Concrete Technology. | Cor-Tuf Concrete Professionals. Cor-tuf UHPC https://cor-tuf.com/

Home UHPC | Ready-Mix | Proven-Results | Steelike® https://steelike.com/

Ceentek Inc. https://projects.constructconnect.com/companies/2152395-ceentek-inc&find_loc=CA-95032

Ibrahim, M. & Moustafa, M. Strength Maturity Method for Quality Control of Field-Cast UHPC Seismic Accelerated Bridge Construction Connections. (2022).

LumiNode2+. LumiCon https://getlumicon.io/products/luminode-plus

Maturix |. Concrete temperature, strength and maturity monitoring. Maturix https://maturix.com/

Giatec Giatec SmartRock Concrete Sensors. https://info.giatecscientific.com/giatec-smartrock

Ibrahim, M. S. Robust Methods for UHPC Early-Strength Determination and Quality Control for Accelerated Bridge Construction. (2022).

ASTM C39/C39M-20. Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens (West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021).

ASTM C109/C109M-20. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. Or [50-mm] Cube Specimens) (ASTM International, 2020).

Graybeal, B. A., PSI & Inc Material Property Characterization of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. (2006). https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/38714

Linear Models with R | & Julian, J. Faraway | Taylor & Francis eBooks, Re. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203507278/linear-models-julian-faraway

ASTM C511-21. Standard Specification for Mixing Rooms, Moist Cabinets, Moist Rooms, and Water Storage Tanks Used in the Testing of Hydraulic Cements and Concretes. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, (2021).

ASTM C31.Standard Practice for Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens in the Field. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend gratitude to LumiCon, Maturix, and Giatec for lending or donating sensors. The donation of UHPC slag by Skyway Cement Company and admixtures by Master Builders Solutions is acknowledged. We also express gratitude to Lafarge, Cor-Tuf, SteeLike, and CeEntek for UHPC donations. The help of undergraduate students Aron McCulloch and Allen Rivas during experimental phase is also appreciated.

Funding

The authors are thankful to ABC-UTC for sponsoring this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shoaib Shahrukh: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software. Ibrahim Mohammed: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Moustafa Mohamed A.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, M.S., Moustafa, M.A. & Shoaib, S. Compressive strength and maturity of UHPC cubes and cylinders: new conversion factors and recommendations for early-age quality control. Sci Rep 16, 2450 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32316-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32316-z