Abstract

The UV-shielding composite films based on nanocrystalline cellulose (CNC) modified with both CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles were prepared by solvent casting method. In the composites, both CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles showed redox activity under UV-irradiation, and the joint effects of that metal oxides in the composite films were evidenced. The WO3 nanoparticles provided reversible photochromic properties to the WO3/CNC film under UV-irradiation while CeO2 nanoparticles inhibited the photochromic effect. The mechanism of this inhibition in the CeO2/WO3/CNC films was investigated using UV–vis and FTIR spectroscopy. The photodegradation of CNC catalyzed by CeO2 nanoparticles inherent in CeO2/CNC films was prevented by the addition of WO3 nanoparticles. The CeO2/CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC films exhibited strong UV-shielding property. The synthesized photostable UV-shielding CeO2/WO3/CNC films with photochromic property which can easily be tuned by the CeO2 to WO3 ratio can be useful for various applications, including protection of UV-sensitive dyes and production of UV-shielding packages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inorganic nanoparticles are widely used in UV-protective materials because of their greater stability compared to organic UV-absorbers, which are often prone to photodegradation. Among the most popular materials, TiO2, ZnO, ZrO2 and CeO2 nanoparticles effectively block UV-A or UV-B radiation, depending on the particle size1,2,3,4. The photocatalytic activity of some inorganic materials, e.g. TiO2 or ZnO can limit their use as photoprotectors. Absorption of UV radiation leads to charge separation and trigger redox reactions on the surface of semiconductor metal oxide nanoparticles, which is advantageous for catalytic or photocatalytic applications1,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, with regard to photoprotective materials, redox surface activity is undesirable because it can result in the material’s degradation and even in the formation of toxic products1,2.

Nanoscale cerium dioxide (CeO2) is considered as a promising photoprotective material as it effectively absorbs UV light and often shows negligible photocatalytic activity1,11,12. CeO2 with particle size less than 10 nm can be prepared by various methods, including hydrothermal13, solvothermal14, microwave15, spray pyrolysis16, room-temperature synthesis in biopolymer matrices17,18 and others. The CeO2 nanoparticles possess fluorite-type crystal structure, where cerium is surrounded by eight oxygen atoms, the band gap of this semiconductor is about 3.2 eV8,9,15.

The CeO2 nanoparticles are considered to be low- or non-cytotoxic12,16,19, and thus attract a great deal of attention as an alternative component of cosmetic sunscreens that doesn’t cause whitish appearance of skin in contrast to TiO2 and ZnO1. Therefore, cerium oxide is well studied as a UV-protective component in dispersions1,12. Availability of synthesis methods of fine CeO2 nanoparticles that can easily disperse in a polymer matrix enables the use of cerium dioxide as a UV-protective component in various composite bulk materials, including electospun cellulose nanofibers13, shielding for wood20, automotive lacquers8, mesostuctured layers for solar cells21. Immobilizing cerium oxide in biopolymers is particularly interesting for producing safe materials for wearable textiles, medical applications, and product packaging.

Nanocrystalline cellulose or cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) is a widely used nontoxic, biodegradable and commercially available material, which allows to produce flexible and transparent films22,23. Chemical modification and functionalization of cellulose-based materials with inorganic nanoparticles improve their barrier24, photoprotective3,25, luminescence26, magnetic27, antimicrobial28, adsorption29 and other properties.

Nanocrystalline cellulose is a transparent material, which can be provided with UV-protective properties by introduction of UV absorbers. Although various nanoparticles (e.g., metal oxides and lignin) significantly improve the UV-protective properties of CNC films, they often reduce transparency in the visible range and increase light scattering (haze) of the composite films. Recently, CNC films with different percentages of lignin nanoparticles and ZnO nanoparticles demonstrated a strong UVC and UVB blocking performance30. Increasing of nanoparticles content from 1 to 5% gradually increased UV-blocking properties, however, at the same time reduced transparency in the visible light region. The PVA/CNC/TiO2 composite exhibited high mechanical strength, which was provided by the CNC, and excellent UPF values, which were provided by the TiO2 nanoparticles31. Incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles into CNC/pectin nanocomposite films reduced transmissions at 600 nm and 280 nm from 70.11 to 29.93% and 28.27 to 4.93%, respectively32. Hybrid films composed by cellulose nanocrystals and carboxymethylated cellulose nanofibrils loaded with montmorillonite clay, despite their low transparency, possessed UV-blocking features33.

However, only a few studies have focused on bulk UV-protective composites based on cellulose or nanocrystalline cellulose modified with cerium dioxide. These studies have shown that cerium dioxide nanoparticles provide cellulose materials with strong photoprotective properties. The in situ synthesis of CeO2 nanoparticles on chitosan-treated linen fabrics improved the UV-protective properties of the material, increasing the UPF sevenfold compared to untreated fabric34. Nanofibers of natural cotton cellulose were prepared by electrospinning and decorated with CeO2 nanoparticles of 40–60 nm in size by hydrothermal method to improve UV-protective properties of the material13. The UV-blocking hybrid coatings with CeO2 and SiO2 were prepared using cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofiber as a biopolymer matrix35. CeO2 of 8 nm in size and SiO2 of 5 nm in size nanoparticles were added to improve UV screening and hardness properties, respectively. The coatings were highly transparent in visible light region, while absorption in UVA region increased with CeO2 content. The transparent UV-shielding composite films based on regenerated cellulose were fabricated by in situ synthesis of CeO2 from cerium nitrate precursor36. The diameters of rod-like cerium oxide nanoparticles in composites vary from 20 to 50 nm depending on the precursor concentrations. The transmittance of the nanocomposite films in the visible light region decreased with increasing precursor concentrations.

Therefore, this work focuses on a novel bulk composites based on nanocrystalline cellulose and CeO2. Using the hydrothermal method described in our previous work allows for the production of ultrafine CeO2 particles37, which can be easily introduced into nanocrystalline cellulose films via solvent casting. Additionally, the use of small particles is expected to produce films transparent in the visible range.

Tungsten trioxide (WO3) semiconductor nanoparticles demonstrate strong UV-absorption, photochromic, photocatalytic and electrochromic properties38,39,40,41,42. Tungsten trioxide exhibits photocatalytic properties under UV-irradiation, and WO3 composites are used for water splitting systems and waste water pollutant treatment43,44, since an efficient charge transfer is provided at the liquid–solid interface. On the other hand, the UV-induced electron transfer in WO3 nanoparticles can lead to reduction of the colorless W+6 to the blue-colored W+5 39. The subsequent oxidation by oxygen molecules in dark results in bleaching of blue color39, thus the reversible photochromic properties make tungsten trioxide a photostable and reusable marker of UV-radiation. Adjusting of WO3 photochromic performance in nanocomposites reveal opportunity to produce smart UV-protective and UV-sensitive materials. For example, influence of the preparation method on coloring contrast and photochromism reversibility of TiO2-WO3 nanoparticles was recently reported45. The highly reversible photochromism of the composite films of nanocrystalline cellulose with WO3 nanoparticles stabilized by polyvinylpyrrolidone was reported in our previous work39. Ultrafine tungsten oxide nanoparticles are colorless, unlike larger particles, which are yellow in color. Therefore, a nanocrystalline cellulose film containing ultrafine WO3 nanoparticles was transparent in the visible range39. Due to the photochromic properties of tungsten oxide, the WO3 composite films can also be used as UV sensors. The current study aims to use WO3 and CeO2 nanoparticles to develop UV-protective composite nanocellulose films and examine the effect of the material’s composition on the photochromic properties of tungsten oxide.

In this study, we produced a novel UV-shielding composite film based on nanocrystalline cellulose (CNC) modified with CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles with tunable photochromism dependent on the CeO2/WO3 ratio and enhanced photostability. Transparent films were obtained by synthesizing ultrasmall CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles, that were immobilized in CNC without additional surfactants. For the first time, the mutual influence of CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles under the action of UV irradiation was investigated. We propose an electron transfer mechanism, whereby CeO2 quenches the photochromic response of WO3, while WO3 inhibits the pro-oxidant photocatalytic degradation of the cellulose matrix typically catalyzed by CeO2 under UV light. The prepared CeO2/WO3/cellulose composite film overcomes the individual limitations of each component, offering an alternative to organic filters and CeO2-based filters for protecting light-sensitive materials. UV–vis and FTIR spectroscopy have been applied to study the UV-shielding properties of the composite films using tungsten trioxide as a photochromic marker and β-carotene as a photodegradable natural dye, and to monitor the kinetics of WO3 photochromism and the photodegradation of the cellulose film.

Experimental

Materials

Ceric ammonium nitrate (NH4)2Ce(NO3)6 (Sigma Aldrich), sodium tungstate (VI) dihydrate Na2WO4∙2H2O (Sigma Aldrich), 1-(4-tert-Butylphenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3-propanedione – “avobenzone” (Sigma Aldrich), β-carotene (0.30%, Luxomix), isopropanol (purity 98%), ethanol (purity 95%), and H2SO4 (purity 98%) were used as starting reagents. Filter paper “blue ribbon” was utilized as a cellulose source. Cation exchange resin (Amberlite® IR120) in acidic form was used in WO3 synthesis.

Preparation of CNC

The dispersion of nanocrystalline cellulose (CNC) was prepared by a commonly used method described elsewhere46. Filter paper (blue ribbon) was shredded and soaked in distilled water for 30 min, then sulfuric acid (98%) was added slowly with vigorous stirring in an ice bath until the acid concentration reached 65%. After 50 min stirring at 47 °C, 1.5 L of cold distilled water was added to the obtained pulp to stop hydrolysis. The resulting nanocrystalline cellulose was rinsed with distilled water, separated by centrifugation, and the residual acid was removed by dialysis. Finally, the nanocrystalline cellulose was sonicated in an ice bath for 2 h to obtain a homogeneous dispersion. The concentration of CNC in the dispersions, measured gravimetrically, was 1–2 wt.%.

Preparation of the metal oxide sols

A facile method of synthesis of surfactant-free CeO2 nanoparticles with narrow size distribution from ceric ammonium nitrate (NH4)2Ce(NO3)6 was described in details previously37. (NH4)2Ce(NO3)6 was dissolved in deionized water to obtain a 0.28 M solution. The solution was heated in an autoclave at 95 °C for 24 h to obtain a yellow precipitate of cerium dioxide. The precipitate was separated by centrifugation and rinsed with isopropanol. The prepared cerium dioxide readily dispersed in deionized water to form a stable, transparent yellow sol with a pH of about 3. The concentration of the sol, measured gravimetrically, was 2.9 wt.%.

The method of preparation of ultra-small WO3 nanoparticles described elsewhere47,48 was modified to obtain WO3/CNC composites. Transparent solution of tungstic acid was prepared from 0.033 M solution of Na2WO4∙2H2O in distilled water, using cation exchange resin in H+ form. The obtained sol of hydrated tungsten trioxide was added to the CNC dispersion immediately after the preparation. The concentration of WO3 in the sol was 2.4 wt.% as measured gravimetrically.

Preparation of the composite films

The flexible transparent colorless films were prepared by the solvent casting method. The ratios of metal oxides to CNC in the films varied as follows: CeO2/CNC (1/10, 0.5/10, 0.1/10, and 0.01/10), CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10, 0.5/1/10, 0.1/1/10, and 0.01/1/10), WO3/CNC (1/10), avobenzone/CNC (0.1/10 and 0.01/10), and avobenzone/WO3/CNC (0.1/1/10 and 0.01/1/10), the molar ratios were calculated per formula units of oxides and cellulose monomer. The corresponding wt.% of CeO2, WO3, and CNC in the prepared films are summarized in Table 1.

To prepare the film, the required amount of CeO2 or WO3 sols were added to the CNC dispersion and stirred to obtain homogeneous mixtures. As avobenzone is virtually insoluble in water, it was dissolved in a small amount of ethanol before mixing with cellulose or WO3/CNC dispersions. The required amount of distilled water was added to achieve CNC concentration of 1.2% in each resulting mixture. Then 4 mL of the mixtures were poured into plastic Petri dishes of 40 mm diameter and dried at room temperature for 5 days. After additional drying at 50 ⁰C, the weight loss due to residual water elimination was 3–7% for all the samples. The thickness of the films was 40 ± 2 μm.

Analysis methods

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (CuKα radiation). Crystallite sizes were estimated using Scherrer equation. The crystallinity index of cellulose nanocrystals was calculated by Segal’s method using the intensity of the reflection at 23° (I200) and the intensity in the minima at 19° between < 110 > and < 200 > reflections as the amorphous part of the signal (IAM) by Eq. (1)26:

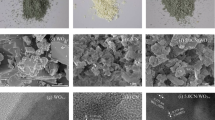

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained on Carl Zeiss NVision 40 electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 0.5 kV, elements content and distribution in samples were measured by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis (X-Max detector, Oxford Instruments). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained on a Leo-912 AB OMEGA microscope with an accelerating potential of 60–120 kV. Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) were measured with resolution of 2 cm-1 in the range of 400–4000 cm-1 using an INFRALUM FT-08 spectrometer. The hydrodynamic radii and ζ-potentials were assessed using a Photocor Compact Z analyzer with a thermally stabilized 638 nm semiconductor laser.

UV–visible reflection spectra of the films were measured using an Ocean Optics QE65000 spectrometer with HPX-2000 xenon lamp. Kinetic features of photochromic reactions were studied using a xenon lamp of spectrometer as a UV-light source. Beta-carotene photodegradation was studied using UV-camera with the emission maximum at 312 nm, UV–visible transmittance spectra of solutions were measured on an OKB SPEKTR SF-2000 spectrometer.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the composite films

The X-ray diffraction data for the CNC film (Fig. 1a) showed signals at 2θ = 16° and 23° corresponding to < 1–10 > overlapped with < 110 > and < 200 > reflections of the Iβ crystalline cellulose structure, respectively46,49. Crystallinity index of cellulose material calculated by Segal’s method was 80%, which is in accordance with literature data for sulfuric acid hydrolyzed cellulose (60–90%)22. TEM image of the CNC sample clearly shows rod-like disordered particles (SI, Fig. S1). The measurements taken on 100 individual particles shows, that the hydrolysis of cellulose with sulfuric acid resulted in the formation of cellulose nanorods with a length of 240 ± 65 nm and a width of 9 ± 2 nm, which corresponds to the typical size range for nanocrystalline cellulose22. EDX data shows that sulfur is present in the material due to the partial esterification of CNC during hydrolysis (SI, Table S1). The ζ-potential of the CNC dispersion at pH 6.5 was - 28 mV, and the charge measured using NaOH titration was 0.4 mmol/g.

(a) XRD patterns of the films: CNC, WO3/CNC 1/10, CeO2/CNC 1/10 (*asterisks mark reflections of CeO2) and CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10). (b) Fragments of FTIR spectra of the CNC (upper), CeO2/CNC 1/10 (middle), and WO3/CNC 1/10 (lower) films. (c) SEM image of the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) film and distributions of Ce and W elements.

The prepared cerium dioxide surfactant-free sol is stabilized by electrostatic interaction between nanoparticles, as was described in details previously37. The sol shows a pH about 3, and the ζ-potential of the CeO2 nanoparticles is about + 30 mV, due to the presence of nitric acid formed during hydrothermal treatment of ceric ammonium nitrate. The TEM image reveals ultrasmall CeO2 nanoparticles within 2–3 nm (Fig. S2). The average hydrodynamic radius of CeO2 was about 7 nm (SI, Fig. S3). The XRD patterns of the CeO2/CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC films, in addition to the CNC reflections show weak reflections attributed to CeO2 nanoparticles of fluorite-type (PDF2 #34–394) crystal structure (Fig. 1a), the average size of the crystallites was estimated as 3 nm. The deconvolution of the peaks in the CeO2/CNC XRD pattern is shown in Fig. S4 (see SI).

The as prepared WO3 nanoparticles with average hydrodynamic radius about 1.4 nm possess ζ-potential of about - 20 mV and the bare sol remains visually transparent and stable during several hours (SI, Fig. S3). In the XRD patterns of the WO3/CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC films, the wide signal is present at 2θ angles < 10⁰ due to scattering on ultra-small amorphous particles of WO3 (Fig. 1a)39. The TEM image shows ultrasmall nanoparticles of WO3 within 2–6 nm (Fig. S2), that is in consistence with previously data reported for the WO3 synthesized by the similar method47,48.

Figure 1b shows FTIR spectra of the composite films. The broad band at 3500–3100 cm-1 is related to stretching vibrations of –OH groups of cellulose, the band at 2900 cm-1 is due to the stretching vibrations of CH– and CH2– groups, the band at 1650 cm-1 is attributed to C = O vibrations of CNC23,50. The band at 1430 cm-1 corresponds to CH2 deformation vibrations, and broad band at 1200–1000 cm-1 is due to the stretching vibrations of C–O–C and C–O groups50. In addition to the CNC absorption bands, the bands at 803 and 947 cm-1 assigned to W–O–W and W = O vibrations, respectively, are present in FTIR spectrum of the WO3/CNC composite film39,51,52. The absorption band at 899 cm-1 corresponds to C–O vibration in CNC film50. In the WO3/CNC film the more intensive absorption band with maximum at 895 cm-1 appears due to overlapping of the C–O vibration of CNC with the absorption band related to WO3.

The very weak absorption band related to Ce–O stretching vibrations is present at 550–450 cm-1 in the FTIR spectrum of the CeO2/CNC film53. In addition, FTIR spectrum of the CeO2/CNC film has the absorption band at 1570 cm-1 in the region of carboxyl group vibrations.

Cerium and tungsten oxides were uniformly distributed in the CeO2/WO3/CNC composite films (Fig. 1c), and the molar ratio of W and Ce atoms in the prepared composite film was also confirmed by EDX data (SI, Table S2). Thermal analysis of the CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) films showed 4–5% weight loss at temperatures below 200 ⁰C due to water desorption, the degradation of the films occurred at 250–450 ⁰C, and oxide nanoparticles did not significantly affect the thermal stability of the films (SI, Fig. S5-S6).

Optical and photochromic properties of the composites

The CNC film was transparent in UV and visible region. Cerium dioxide semiconductor nanoparticles caused strong absorption below 430 nm in UV–vis spectrum of the CeO2/CNC composite films (Fig. 2a). The band gap about 2.8 eV estimated using Tauc plot is typical for CeO2 nanoparticles (SI, Fig. S7)8.

(a) UV–vis spectrum of the CeO2/CNC 1/10 film. (b and c) Changes in UV–vis. spectra of the WO3/CNC (1/10) and CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) films, respectively, under UV-irradiation for 2-, 8- and 16-min. (d) Reflectance at 780 nm in spectra of the WO3/CNC (1/10) under irradiation with different wavelengths (as measured after 5 min of irradiation of the initially colorless sample). e) The appearance of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films with different component ratios before and after UV-irradiation.

The prepared WO3/CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC composite films were also colorless and possessed a strong absorption in UV-region. UV light exposure caused an intense blue coloration of the WO3/CNC film, while the blue coloration of the CeO2/WO3/CNC film was very weak.

Photochromic properties of WO3 nanoparticles are related to UV-induced reduction of W+6 in colorless WO3 nanoparticles to W+5 and W+4 species which absorb light in the visible region38,39,54,55,56. Absorption of a UV-photon with an energy higher than the band gap of WO3 nanoparticles (2.6–3.0 eV, depending on particle size57) initiates electron transition to conduction band and formation of positively charged hole in valence band (2). Reduction of the W+6 ion by the electrons results in blue coloration of the tungsten trioxide nanoparticles (3). Interaction between positive holes and water molecules absorbed on the surface of WO3 nanoparticles weakens O–H bonds, resulting in a release of protons H+6 and highly reactive oxygen species, which can recombine to form O2 molecules or produce OH• radicals (4)38,48. The reverse discoloration occurs in the dark due to oxidation of tungsten ions to colorless W+6 species by oxygen molecules (5).

The efficiency of electron–hole recombination and alternative redox reactions affect the photochromic properties of tungsten oxide. Various ligands with -OH or = NH groups enhance the photochromism in WO3 composites. Apparently, complexation with ligands through hydrogen and donor–acceptor bonds promotes the reduction of W+6 under UV light. For example, Adachi et al. showed strong photochromic properties of WO3/cellulose films, while surfactant-free WO3 nanoparticles and WO3/triacetyl cellulose hybrid films were not photochromic38. Polyvinylpyrrolidone and polycarbonate have also been used to enhance the photochromic properties of tungsten oxide39,54.

Although cellulose bear three -OH groups in each glucopyranose fragment, the aqueous dispersion containing both WO3 and CNC did not exhibit photochromic properties. The –OH groups on cellulose surface probably cannot substitute water molecules in the coordination sphere of the hydrated WO3 nanoparticles. On the contrary, the WO3/CNC films obtained by the solvent casting method were strongly photochromic, indicating coordination bonds between tungsten trioxide nanoparticles and –OH groups on the surface of the cellulose nanoparticles.

Exposure of the composite films to UV-light resulted in the increase in the intensity of absorption bands near 780 and 620 nm corresponding to W+5 and W+4 species, respectively (Fig. 2b and c)55,56. The absorption at 780 nm appeared first under UV irradiation, while the absorption band at 620 nm grew rapidly and dominated in the spectra of the films after several minutes of UV-exposure. Notably, the absorption band intensities in the WO3/CNC spectrum increased significantly faster than in the corresponding CeO2/WO3/CNC film spectra. This effect depends on the composition of the composite films, resulting in slower coloration of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films with higher CeO2 content (Fig. 2e). In order to estimate the excitation wavelengths causing photochromic reaction, the WO3/cellulose film was exposed to narrow-band UV light (bandwidth ~ 10 nm) having wavelengths ranging from 470 to 380 nm. The absorption band in the UV spectra at 780 nm indicating the photochromic transition appeared under irradiation with wavelengths shorter than 390 nm (see Fig. 2d).

Effect of CeO2 on photochromic properties of the composite films

In order to study the effect of CeO2 on the photochromic properties of the synthesized composite films, the coloration kinetics under irradiation with the Xe-lamp of a spectrometer were measured for WO3/CNC, CeO2/WO3/CNC and WO3/CNC top covered with CeO2/CNC film (Fig. 3).

(a) The coloration kinetic of the WO3/CNC (1/10) film and the WO3/CNC (1/10) top covered with the CeO2/CNC films with different CeO2 content. (b) The coloration kinetic of the WO3/CNC (1/10) film and the CeO2/WO3/CNC films with different component ratios. (c) The coloration kinetic of the WO3/CNC (1/10) film, the WO3/CNC (1/10) film top covered with the avobenzone/cellulose films with different component ratios, and the avobenzone/WO3/cellulose films with different component ratios. The kinetic curves were measured using the relative intensities of the 620 nm band in UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra. d) The fragments of the FTIR spectra before and after UV-irradiation of the films: WO3/CNC (1/10), CeO2/WO3/CNC (0.5/1/10) and CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10).

The CeO2/CNC film placed onto the WO3/CNC sample showed a strong shielding effect and inhibited the coloration of tungsten species upon Xe-lamp irradiation, because of the strong UV-absorption of CeO2 nanoparticles. The UV-absorption band of CeO2 (< 430 nm) fully overlapped the spectral region initiating coloration of WO3 (< 390 nm). The CeO2/CNC (0.01/10) film with very low content of ceria did not affect the WO3/CNC coloration kinetics (Fig. 3a). In turn, the samples with higher CeO2/CNC ratios (0.1/10, 0.5/10, and 1/10) decreased coloration rate of the WO3/CNC film (Fig. 3a).

The photochromic property of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films depended on the CeO2 content in the composite. Upon the UV-irradiation of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films, the intensity of the absorption band at 620 nm increased slowly (Fig. 3b). The kinetic colouration curves for the CeO2/WO3/CNC (0.01/1/10 and 0.1/1/10) samples demonstrated minor differences from the kinetics for the reference WO3/CNC (1/10) film. For the composite films with higher CeO2 concentration, significantly slower coloration was observed. The CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) film remained transparent and nearly colorless during prolonged UV-exposure (over 7 h). As shown in Fig. 3a and b, the addition of CeO2 in the CeO2/WO3/CNC composite films inhibits photochromism of WO3 in a more pronounced manner than top covering the WO3/CNC film with the CeO2/CNC film.

The same experiments were performed to compare the UV-protecting effect of CeO2 with that of one of the most common organic UV-filters, avobenzone (absorption maximum at 357 nm)58,59. Both the avobenzone/WO3/CNC (0.01/1/10 and 0.1/1/10) films and the WO3/CNC film top covered with the avobenzone/CNC (0.01/10 and 0.1/10) films were exposed to UV-light. As shown on Fig. 3c, the avobenzone/CNC films effectively shielded WO3/CNC films and inhibited their coloration, and the UV-shielding efficiency correlated with the avobenzone concentration in the avobenzone/CNC films. On the other hand, the use of avobenzone as a component in composite films (avobenzone/WO3/CNC samples) showed only a negligible effect on the coloration of WO3 (Fig. 3c), and thus the shielding effect of CeO2 nanoparticles in the composite CeO2/WO3/CNC films was much more prominent than that of avobenzone.

The rate of non-chain photochemical processes linearly depends on intensity of absorbed light, and each UV-absorber reduces a light intensity according to the following Eq. (6):

where I(UV) and I0(UV) – intensities of transmitted and incident UV-light; C – concentration of UV-absorber; ε – extinction coefficient of UV-shielding material; l – optical path length.

The UV-shielding CeO2/CNC and avobenzone/CNC films had the same thickness and the optical path lengths were also the same. Thus, the intensity of UV-light which reaches the surface of the WO3/CNC film depended only on the concentration of the UV-filter (CeO2 or avobenzone) in the CeO2/CNC or avobenzone/CNC films.

When avobenzone or CeO2 were added directly in the photochromic films (avobenzone/WO3/CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC samples, respectively) the WO3 nanoparticles in the composites were exposed to UV-light along with avobenzone and CeO2. In the case of avobenzone/WO3/CNC films this expectedly resulted in a quite low UV-shielding effect of avobenzone. In contrast, the strong inhibition of photochromism of CeO2/WO3/CNC films cannot be fully explained by CeO2 UV-absorption. Since cerium has two stable oxidation states, it can participate in additional redox reactions that affect the photochromism of WO3.

The FTIR spectra of the CeO2/WO3/CNC and WO3/CNC films demonstrated changes after UV-exposure (Fig. 3d). The absorption band of WO3 in the WO3/CNC film at 803 cm-1 faded under UV-irradiation, while another band of WO3 at 947 cm-1 became more intense. The observed changes in the vibrational spectra are related to the changes in the chemical bonding in the WO3/CNC composite due to the reduction of tungsten ions in the course of the reaction (3). For the non-irradiated CeO2/WO3/CNC (0.5/1/10 and 1/1/10) samples, the intensity of the IR-absorption band at 803 cm-1 negatively correlated with the CeO2 content. Note that UV-irradiation caused only minor changes in the absorption band intensities at 803 and 947 cm-1 of the CeO2/WO3/CNC (0.5/1/10) film, and almost negligible changes in the absorption band intensities of the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) film. These results indicated that CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles in the composite films are able to interact chemically, preventing the coloration of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films. Such an interaction between CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles may provide effective electron transfer from excited tungsten trioxide to CeO2 thus leading to the partial reduction of cerium ions instead of the reduction of tungsten from colorless W+6 to blue W+5 (reaction (3)).

Blue WO3/CNC films became colorless when oxidized with atmospheric oxygen in the dark by reaction (5). Discoloration kinetic curves of the WO3/CNC (1/10) and CeO2/WO3/CNC (0.1, 0.5, and 1/1/10) films are presented in Fig. 4a. The discoloration kinetic of the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) film cannot be compared to those of the other samples due to the very low intensity of the band at 620 nm. Comparison of the discoloration kinetics of the CeO2/WO3/CNC (0.1/1/10 and 0.5/1/10) films showed that the higher CeO2 content promotes faster discoloration process. The oxidation of tungsten ions by CeO2 by the reaction (7) may facilitate the discoloration of WO3:

(a) The discoloration kinetic of the WO3/CNC (1/10) film and the CeO2/WO3/CNC films with different component ratios, as measured using intensities of an absorption band at 620 nm in the diffuse reflectance spectra. (b) The fragments of FTIR spectra of the CeO2/CNC (1/10) and CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) films before and after 7 h UV-exposure. (c) The effect of the CeO2/WO3/CNC and CNC shielding films on the UV-photodegradation of beta-carotene. (d) The effect of the CeO2/WO3/CNC and CNC protective films on the UV-photodegradation of dyes used in office supplies.

Effect of WO3 on the photostability of the composite films

Metal oxide nanoparticles are photostable, unlike organic photoprotectors such as avobenzone59. However, due to their photocatalytic properties, they can affect the photodegradation of the polymer matrix in which they are embedded.

The prolonged UV-irradiation of the CeO2/CNC film resulted in the growth of a new band at 1570 cm-1 in the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 4b), which corresponds to asymmetric vibrations of -COO- carboxylic groups. This indicates that the photo-induced oxidation of CNC can proceed in the presence of CeO2 nanoparticles. In some cases, nanoscale CeO2 can show catalytic effects and can exhibit prooxidant properties which are often regarded as oxidoreductase-like activity60,61. CeO2 also caused oxidation of the chelating molecules under light exposure, as was observed for dextran coated and citrate coated cerium oxide nanoparticles20,62. In the CeO2/CNC films the hydroxyl groups of cellulose coordinated with cerium ions possibly undergo oxidation under UV-light.

On the contrary, the FTIR spectra of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films didn’t change significantly after even prolonged UV-exposure (over 7 h) and the band inherent in asymmetric vibrations of -COO- carboxylic groups was not detected (Fig. 4b). This observation confirms the protective effect of WO3 nanoparticles against possible cellulose oxidation in the presence of CeO2. Photochromic WO3 sol can show photoreductive properties and act as photoprotector in photooxidation processes, as it was reported elsewhere63. Thus, the effect of WO3 on the photostability of the CeO2/WO3/CNC composite may involve photoreduction mechanisms that prevents oxidation of cellulose under UV-irradiation.

UV-shielding property of the CeO2/WO3/CNC composite films

All the prepared CeO2/WO3/CNC films demonstrated strong absorption in UV range, while the photochromic properties depended on the CeO2 to WO3 ratio. The film with the highest cerium dioxide content CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) showed the least photochromic changes in comparison with the other films and remained nearly colorless when exposed to UV radiation. As the transparency in visible range and no color changes is preferable for UV-shielding materials, the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) has the most preferable composition among others.

The ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) and percentages of UVA and UVB radiation blocking for the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) film were calculated using equations 8-1064,65:

where E (λ) is the relative erythema spectral effectiveness, S(λ) is the spectral irradiance (W/m-2 nm-1), T(λ) is the experimental spectral transmittance of the sample, and λ is wavelength. The values of E(λ) and S(λ) were obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration database (NOAA). Transmittance spectra were measured on UV–vis spectrometer using air as a reference. The sample was rotated for 90⁰ each time, resulting in four spectra.

The CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) demonstrated UVA and UVB shielding of 99% and 100%, respectively (Table 2). UPF is typically used to characterize UV-protective textiles, with values above 50 being considered excellent. While the UPF in the CNC film was only 3.4 in the 320–400 nm range, it was about 450 for the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) composite film, which demonstrates the excellent UV-protection properties of the material.

The UV shielding properties of the synthesized films were tested with respect to a solution of beta-carotene—the well-known antioxidant66,67. Cuvettes containing β-carotene solutions in heptane were covered with the CNC or CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) films and further exposed to UV light with a wavelength maximum at 312 nm. The reference sample of beta-carotene was stored in the dark. Upon the UV-irradiation of β-carotene sample covered with unmodified CNC film, its optical absorption band at 450 nm rapidly faded and its intensity showed a twofold decrease within 2 h. In turn, CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) composite film effectively prevented the bleaching of β-carotene, and only a 10% decrease in the intensity of the absorption band was observed after 2 h of UV-irradiation (Fig. 4c). The UV-shielding properties of the CeO2/WO3/CNC (1/1/10) composite were also demonstrated for the common office notepaper sheets (Fig. 4d).

Conclusions

The CeO2/CNC, WO3/CNC, and CeO2/WO3/CNC composite films were produced from nanocrystalline cellulose and metal oxide sols containing no additional organic stabilizers by the solvent casting method. The UV-shielding and photochromic properties of the films were studied.

The WO3/CNC films turned blue under UV- irradiation with wavelengths below 390 nm due to the reduction of W+6 to W+5 and W+4 and became colorless upon exposure to atmospheric oxygen in the dark, demonstrating reversible photochromic properties. The addition of CeO2 nanoparticles inhibited the photochromic properties of the CeO2/WO3/CNC films in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition to the absorption of UV light by CeO2, its redox interactions with WO3 can impact the inhibition of the photochromic property of the composites.

The CeO2/CNC and CeO2/WO3/CNC films demonstrated strong UV-shielding properties, and protected both photochromic films and photodegradable organic dyes from the colour changes. The UV-exposure of the CeO2/CNC films caused photodegradation of CNC, while the addition of WO3 nanoparticles protected CNC in the CeO2/WO3/CNC composites.

Therefore, the mutual influence of CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles in CeO2/WO3/CNC composite films was studied for the first time, and the transparent UV-shielding CeO2/WO3/CNC films with enhanced photostability were produced. The photochromic properties of these films can easily be tuned by the CeO2 to WO3 ratio change. The CeO2/WO3/CNC films can be useful for various applications, including protection of photodegradable dyes, paper documents, and production of UV-shielding packages.

Data availability

Data analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Nery, É. M., Martinez, R. M., Velasco, M. V. R. & Baby, A. R. A short review of alternative ingredients and technologies of inorganic UV filters. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 20, 1061–1065 (2021).

Yousefi, F., Mousavi, S. B., Heris, S. Z. & Naghash-Hamed, S. UV-shielding properties of a cost-effective hybrid PMMA-based thin film coatings using TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles: a comprehensive evaluation. Sci. Rep. 13, 7116 (2023).

Liao, Y., Wang, C., Dong, Y. & Yu, H.-Y. Robust and versatile superhydrophobic cellulose-based composite film with superior UV shielding and heat-barrier performances for sustainable packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 127178 (2023).

Alebeid, O. K. & Zhao, T. Review on: developing UV protection for cotton fabric. J. Text. Inst. 108, 2027–2039 (2017).

Sofroniou, C. et al. Tunable Assembly of Photocatalytic Colloidal Coatings for Antibacterial Applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 6, 10298–10310 (2024).

Dinoop lal, S. et al. Accelerated photodegradation of polystyrene by TiO2-polyaniline photocatalyst under UV radiation. Eur. Polym. J. 153, 110493. (2021).

Maraveas, C., Kyrtopoulos, I. V., Arvanitis, K. G. & Bartzanas, T. The Aging of Polymers under Electromagnetic Radiation. Polymers (Basel). 16, 689 (2024).

Saadat-Monfared, A., Mohseni, M. & Tabatabaei, M. H. Polyurethane nanocomposite films containing nano-cerium oxide as UV absorber Part 1. Static and dynamic light scattering, small angle neutron scattering and optical studies. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 408, 64–70 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Fabrication of a modified straw cellulose and cerium oxide nanocomposite and its visible-light photocatalytic reduction activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5, 3734–3740 (2017).

Ji, P., Zhang, J., Chen, F. & Anpo, M. Study of adsorption and degradation of acid orange 7 on the surface of CeO2 under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 85, 148–154 (2009).

Miri, A., Akbarpour Birjandi, S. & Sarani, M. Survey of cytotoxic and UV protection effects of biosynthesized cerium oxide nanoparticles. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 34, e22475 (2020).

Shcherbakov, A. B. et al. CeO2 Nanoparticle-Containing Polymers for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymers (Basel). 13, 924 (2021).

Li, C., Shu, S., Chen, R., Chen, B. & Dong, W. Functionalization of Electrospun Nanofibers of Natural Cotton Cellulose by Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles for Ultraviolet Protection. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 130, 1524–1529 (2013).

Kar, S., Patel, C. & Santra, S. Direct room temperature synthesis of valence state engineered ultra-small ceria nanoparticles: Investigation on the role of ethylenediamine as a capping agent. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 4862–4867 (2009).

Goharshadi, E. K., Samiee, S. & Nancarrow, P. Fabrication of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Characterization and optical properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 356, 473–480 (2011).

Xia, T. et al. Comparison of the Mechanism of Toxicity of Zinc Oxide and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Based on Dissolution and Oxidative Stress Properties. ACS Nano 2, 2121–2134 (2008).

Melnikova, N. et al. Synthesis of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in a Bacterial Nanocellulose Matrix and the Study of Their Oxidizing and Reducing Properties. Molecules 28, 2604 (2023).

Spiridonov, V. V et al. One-Step Low Temperature Synthesis of CeO2 Nanoparticles Stabilized by Carboxymethylcellulose. Polymers (Basel). 15, 1437 (2023).

Shcherbakov, A. B. et al. Nanocrystalline ceria based materials—Perspectives for biomedical application. Biophysics (Oxf). 56, 987–1004 (2011).

Auffan, M. et al. Long-term aging of a CeO2 based nanocomposite used for wood protection. Environ. Pollut. 188, 1–7 (2014).

Corma, A., Atienzar, P., García, H. & Chane-Ching, J. Y. Hierarchically mesostructured doped CeO2 with potential for solar-cell use. Nat. Mater. 3, 394–397 (2004).

Habibi, Y., Lucia, L. A. & Rojas, O. J. Cellulose Nanocrystals: Chemistry, Self-Assembly, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 110, 3479–3500 (2010).

Lu, P. & Hsieh, Y.-L. Preparation and properties of cellulose nanocrystals: Rods, spheres, and network. Carbohydr. Polym. 82, 329–336 (2010).

Kaschuk, J. J. et al. Cross-Linked and Surface-Modified Cellulose Acetate as a Cover Layer for Paper-Based Electrochromic Devices. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 3, 2393–2401 (2021).

Ning, R., Takeuchi, M., Lin, J. M., Saito, T. & Isogai, A. Influence of the morphology of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the properties of zinc oxide/nanocellulose composite films. React. Funct. Polym. 131, 293–298 (2018).

Fedorov, P. P. et al. Preparation and properties of methylcellulose/nanocellulose/CaF2:Ho polymer-inorganic composite films for two-micron radiation visualizers. J. Fluor. Chem. 202, 9–18 (2017).

Liu, S., Zhou, J., Zhang, L., Guan, J. & Wang, J. Synthesis and Alignment of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in a Regenerated Cellulose Film. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 27, 2084–2089 (2006).

Jia, B., Mei, Y., Cheng, L., Zhou, J. & Zhang, L. Preparation of copper nanoparticles coated cellulose films with antibacterial properties through one-step reduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 4, 2897–2902 (2012).

Riva, L. et al. Silver Nanoparticles Supported onto TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibers for Promoting Cd2+ Cation Adsorption. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 2401–2413 (2024).

Lotfy, V. F. & Basta, A. H. Sustainable development of rice straw pulping liquor-based lignin nanoparticles in enhancing the performance of cellulose nanostructured suspension for UV shielding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 307, 142124 (2025).

Nguyen, S. V. & Lee, B.-K. PVA/CNC/TiO2 nanocomposite for food-packaging: Improved mechanical, UV/water vapor barrier, and antimicrobial properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 298, 120064 (2022).

Sharaby, M. R., Soliman, E. A., Abdel-Rahman, A. B., Osman, A. & Khalil, R. Novel pectin-based nanocomposite film for active food packaging applications. Sci. Rep. 12, 20673 (2022).

Valdez Garcia, J. et al. Multifunctional nanocellulose hybrid films: From packaging to photovoltaics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 292, 139203 (2025).

Tripathi, R., Narayan, A., Bramhecha, I. & Sheikh, J. Development of multifunctional linen fabric using chitosan film as a template for immobilization of in-situ generated CeO2 nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 121, 1154–1159 (2019).

Abitbol, T., Ahniyaz, A., Álvarez-Asencio, R., Fall, A. & Swerin, A. Nanocellulose-Based Hybrid Materials for UV Blocking and Mechanically Robust Barriers. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 2245–2254 (2020).

Wang, W., Zhang, B., Jiang, S., Bai, H. & Zhang, S. Use of CeO2 nanoparticles to enhance UV-shielding of transparent regenerated cellulose films. Polymers (Basel). 11, (2019).

Shcherbakov, A. B. et al. Facile method for fabrication of surfactant-free concentrated CeO2 sols. Mater. Res. Express 4, 55008 (2017).

Adachi, K. et al. Kinetic characteristics of enhanced photochromism in tungsten oxide nanocolloid adsorbed on cellulose substrates, studied by total internal reflection Raman spectroscopy. RSC Adv. 2, 2128–2136 (2012).

Evdokimova, O. L. et al. Highly reversible photochromism in composite WO3/nanocellulose films. Cellulose 26, 9095–9105 (2019).

Stoenescu, S., Badilescu, S., Sharma, T., Brüning, R. & Truong, V.-V. Tungsten oxide–cellulose nanocrystal composite films for electrochromic applications. Opt. Eng. 55, 127102 (2016).

Márquez-Lucero, A. et al. Room Temperature Detection of Acetone by a PANI/Cellulose/WO 3 Electrochemical Sensor. J. Nanomater. 2018, 1–9 (2018).

An, F. H., Yuan, Y. Z., Liu, J. Q., He, M. D. & Zhang, B. Enhanced electrochromic properties of WO3/ITO nanocomposite smart windows. RSC Adv. 13, 13177–13182 (2023).

Enesca, A. & Cazan, C. Polymer Composite-Based Materials with Photocatalytic Applications in Wastewater Organic Pollutant Removal: A Mini Review. Polymers (Basel). 14, 3291 (2022).

Shabdan, Y., Markhabayeva, A., Bakranov, N. & Nuraje, N. Photoactive Tungsten-Oxide Nanomaterials for Water-Splitting. Nanomaterials 10, 1871 (2020).

Belhomme, L. et al. Investigation of the Photochromism of WO3, TiO2, and Composite WO3–TiO2 Nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. 63, 10079–10091 (2024).

Fedorov, P. P. et al. Composite up-conversion luminescent films containing a nanocellulose and SrF 2: Ho particles. Cellulose 26, 2403–2423 (2019).

Shiryaeva, E. S. et al. Unusual enhancement of the radical production in the X-ray irradiated aqueous-organic systems containing W(VI) in homogeneous and nanoparticle forms. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 222, 111812 (2024).

Popov, A. L. et al. Photo-induced toxicity of tungsten oxide photochromic nanoparticles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 178, 395–403 (2018).

French, A. D. Idealized powder diffraction patterns for cellulose polymorphs. Cellulose 21, 885–896 (2014).

Tsuboi, M. Infrared spectrum and crystal structure of cellulose. J. Polym. Sci. 25, 159–171 (1957).

Barroso-Bogeat, A., Alexandre-Franco, M., Fernández-González, C., Macías-García, A. & Gómez-Serrano, V. Preparation of Activated Carbon-SnO2, TiO2, and WO3 Catalysts. Study by FT-IR Spectroscopy. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 5200–5206 (2016).

Dejournett, T. J. & Spicer, J. B. The influence of oxygen on the microstructural, optical and photochromic properties of polymer-matrix, tungsten-oxide nanocomposite films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 120, 102–108 (2014).

Verma, A., Bakhshi, A. K. & Agnihotry, S. A. Effect of citric acid on properties of CeO 2 films for electrochromic windows. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 90, 1640–1655 (2006).

Hwang, D. K., Kim, H. J., Han, H. S. & Shul, Y. G. Development of Photochromic Coatings on Polycarbonate. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 32, 137–141 (2004).

Fayad, A. M., Ouis, M. A., ElBatal, F. H. & Elbatal, H. A. Shielding Behavior of Gamma-Irradiated MoO3 or WO3-Doped Lead Phosphate Glasses Assessed by Optical and FT Infrared Absorption Spectral Measurements. SILICON 10, 1873–1879 (2018).

Kameneva, S. V. et al. Photochromic aerogels based on cellulose and chitosan modified with WO3 nanoparticles. Nanosyst. Physics. Chem. Math. 13, 404–413 (2022).

González-Borrero, P. P. et al. Optical band-gap determination of nanostructured WO3 film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 61909 (2010).

Vielhaber, G., Grether-Beck, S., Koch, O., Johncock, W. & Krutmann, J. Sunscreens with an absorption maximum of ≥360 nm provide optimal protection against UVA1-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1{,} interleukin-1{,} and interleukin-6 in human dermal fibroblasts. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 5, 275–282 (2006).

Afonso, S. et al. Photodegradation of avobenzone: Stabilization effect of antioxidants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 140, 36–40 (2014).

Takio, N., Bora, D., Basumatary, D., Yadav, M. & Yadav, H. S. An Oxidoreductase Biomimetic System Based on CeO2 Nanoparticles. J. Water Chem. Technol. 44, 216–224 (2022).

Filippova, A. D. et al. Peroxidase-like Activity of CeO 2 Nanozymes: Particle Size and Chemical Environment Matter. Molecules 28, 3811 (2023).

Barkam, S. et al. The Change in Antioxidant Properties of Dextran-Coated Redox Active Nanoparticles Due to Synergetic Photoreduction–Oxidation. Chem. – A Eur. J. 21, 12646–12656 (2015).

Kozlov, D. A. et al. Photochromic and photocatalytic properties of ultra-small PVP-stabilized WO3 nanoparticles. Molecules 25, 1–16 (2020).

Yassin, S. et al. Sheet-like Cellulose Nanocrystal-ZnO Nanohybrids as Multifunctional Reinforcing Agents in Biopolyester Composite Nano fi bers with Ultrahigh UV-Shielding and Antibacterial Performances. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 1, 714–727 (2018).

Becheri, A., Dürr, M., Lo Nostro, P. & Baglioni, P. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles: application to textiles as UV-absorbers. J. Nanoparticle Res. 10, 679–689 (2008).

Zhou, Y.-M., Chang, H.-T., Zhang, J.-P. & Skibsted, L. H. Clove Oil Protects β-Carotene in Oil-in-Water Emulsion against Photodegradation. Appl. Sci. 11, 2667 (2021).

Safdarian, M., Hashemi, P. & Ghiasvand, A. A fast and simple method for determination of β-carotene in commercial fruit juice by cloud point extraction-cold column trapping combined with UV–Vis spectrophotometry. Food Chem. 343, 128481 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 24-13-00370). The experiments were performed using the equipment of the Joint Research Centre of IGIC RAS. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Alexander B. Shcherbakov and Prof. Sergey V. Ryazantsev for the valuable discussions they provided during the planning and development of this work.

Funding

The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project 24–13-00370).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K., A.B., and V.I. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by S.K., M.P., T.K., A.L., A.Y. The first draft of the manuscript was written by S.K. and M.P. All the authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kameneva, S.V., Popkov, M.A., Kozlova, T.O. et al. UV-shielding photochromic composite films based on nanocrystalline cellulose modified with CeO2 and WO3 nanoparticles. Sci Rep 16, 2516 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32327-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32327-w