Abstract

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most prevalent malignancy among men worldwide. However, current screening tools such as serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests and digital rectal examination (DRE) are limited by low specificity and high false-positive rates, often leading to unnecessary biopsies and overtreatment. To address this clinical challenge, we developed a novel diagnostic framework termed PCASSO (Prostate CAncer diagnosis using Sensitive and Sophisticated ML classifiers based on nOn-invasive urinary RNA biomarkers), which integrates machine learning (ML) algorithms with non-invasive urinary RNA biomarker profiles obtained from DRE-free whole urine. A total of 163 urine samples (112 PCa, 51 benign prostatic hyperplasia [BPH]) were analyzed using quantitative PCR for 20 RNA biomarkers, including 2 long noncoding RNAs, 1 fusion gene, and 17 miRNAs. Among six ML classifiers evaluated, a Gradient Boosting model using an optimized 9-biomarker panel achieved the highest diagnostic performance (AUC: 0.99), with robust cross-validation results (Stratified-K-Fold: 0.912; LOOCV: 0.890). Notably, this classifier retained high accuracy in patients within the PSA gray zone (3–10 ng/mL), where clinical decision-making is often ambiguous. Our results demonstrate that ML-based classifiers using DRE-free urinary RNA biomarkers showed improved performance through robust internal validation, providing a basis for future validation studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer in males, with an estimated 1.4 million new cases worldwide in 20201. The current standard PCa screening methods include tracing the level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in serum and digital rectal examination (DRE)2. In particular, serum PSA testing allows early cancer detection that can affect patient outcome3. Still, limited specificity of elevated PSA level alone results in a high false positive rate, leading to unnecessary prostate biopsies and subsequent overtreatments4. Therefore, there is a critical need for a non-invasive, DRE-free screening platform that is highly accurate and minimizes false results for PCa diagnosis.

There has been a surge in research to identify PCa-specific biomarkers that can surpass the diagnostic performance of PSA5,6. Noncoding RNAs and fusion transcripts show measurable diagnostic signal in urine, tissue, and blood, indicating that molecular readouts can complement clinical assessment7,8,9,10. However, single-marker assays capture only one biological axis of cancers with heterogeneous origins and are typically sensitive to cohort differences, related benign conditions, and pre-analytical variation, thereby reducing stability across studies and clinical settings6,11,12. These limitations motivate the use of multivariate panels that integrate biologically complementary biomarkers with relevant clinical variables to improve accuracy and reproducibility beyond single analytes13,14,15. Clinical models composed of multiple biomarker panels could better accommodate pathway diversity, provide more reliable risk estimates, and reduce unnecessary biopsies by refining decisions in the PSA gray zone, where single markers often underperform14,16. Since prostate-derived RNAs are readily detected in DRE-free urine, often at elevated levels compared to those in blood, this matrix supports a clinically relevant and patient-friendly sampling method that preserves key molecular signatures14,17,18. Given this framework for diverse molecular signatures representative of disease states, machine learning (ML) offers a principled way to combine multiple RNA markers, capture interactions and nonlinearity, and generate individualized risk estimates suitable for real-world screening workflows11,19.

In this study, we developed a novel method called Prostate Cancer diagnosis using Sensitive and Sophisticated ML classifiers based on non-invasive urinary RNA biomarkers (PCASSO) to diagnose PCa using ML techniques and urinary RNA biomarkers from DRE-free whole urine samples. Six types of supervised ML classifiers were evaluated with 20 urinary RNA biomarkers (2 long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), 1 fusion gene mRNA and 17 miRNAs). Furthermore, this study aimed to evaluate the performance of the pre-trained ML classifier on PSA gray zone patients (PSA 3–10 ng/mL), for whom clinical decision-making is often ambiguous. Therefore, this study presents novel ML-based diagnostic models using DRE-free urinary RNA biomarkers and to evaluate their performance through robust internal validation, providing a basis for future external validation studies.

Methods

Patient information and clinical data collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Republic of Korea/IRB No. 2019-1312) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All clinical data and urine samples were prospectively collected from patients treated between 2019 and 2021 at Asan Medical Center. The final cohort included urine samples from 51 patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and 112 patients with histologically verified PCa. Clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

To establish a definitive diagnostic standard for model training and evaluation, we defined the ground truth as follows: For the 98 patients (out of 112 PCa cases) who underwent radical prostatectomy (RP), the final histopathological report from the resected prostate tissue was used to confirm the definitive diagnosis. This approach provided a definitive diagnosis for all the patients in this subgroup, including cases where the initial biopsy data were not recorded but were subsequently confirmed by post-surgical pathology with pathological Gleason score and staging. Notably, 3 of these 98 RP patients were classified as pT0. These patients were retained in the PCa cohort as their initial biopsy-confirmed diagnosis (cT2, Gleason score 6) represented the ground truth at screening. This “vanishing cancer phenomenon” (pT0) has been reported for small, low-grade tumors potentially removed entirely by biopsy20. For the remaining 14 PCa patients who did not undergo RP (e.g., received radiation therapy or other treatments), the diagnosis confirmed by the initial prostate biopsy results was used instead. For the 51 patients with benign conditions, the diagnosis was also confirmed by initial prostate biopsy results.

This stratified diagnostic standard was established to evaluate the models against the most reliable clinical endpoint available for each patient subgroup, using post-prostatectomy histopathology as the gold standard where possible to minimize the known bias of biopsy-based diagnoses21.

Urine specimen collection

The protocols for the human urine assay were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Asan Medical Center, and the human urine assays were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines. All urine samples were collected without DRE. Urine was immediately processed and extraction of urinary RNA was conducted using the QIAamp® Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (QIAGEN). Urinary RNA was synthesized into cDNA for mRNA and miRNA detection, using the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit and the miRCURY LNA™ Universal RT Kit (QIAGEN), respectively. The detailed experimental procedure is provided in Supplementary materials and methods.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

qPCR was performed on synthesized cDNA from urinary RNA using the Stratagene Mx3000P (Agilent Technologies). ORA™ qPCR Green ROX L Mix (highQu) was used for amplification. miRCURY LNA™ miRNA PCR Assay (QIAGEN) was used as primers to quantify miRNA levels. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Thermal cycling for lncRNA and mRNA detection started with a 15 min denaturation step at 95 °C, followed by 50 repeated cycles of 15 s at 95 °C for denaturation and 60 s at 60 °C for annealing/extension. Thermal cycling protocol for miRNA detection followed manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in R version 4.0.1 (http://www.R-project.org). Raw qPCR traces were processed using Stratagene Mx3000P software to determine cycle threshold (Ct). The urinary RNA marker expression levels were normalized against their mean β-actin and 18S rRNA values as follows: Normalized expression (− ΔCt) = (Ctβ-actin + Ct18S-rRNA)/2 − Cttarget gene. Comparison of normalized expression levels (− ΔCt) between BPH and PCa was analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and p-values were adjusted with Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. The diagnostic potential of each RNA marker was assessed using normalized expression (− ΔCt) in a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with the pROC package22. The bootstrap method of 2000 replicates was applied to computing the measurement uncertainties in ROC analysis22,23, and the ML decision margins were analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test24.

Supervised ML classifiers

A customized ML program based on Python 3.8.5 including open libraries, Scikit Learn25 and Pandas26 was utilized to construct PCa/BPH classifiers. Supervised ML classifiers used were as follows: C-support Vector Classification (SVC)27,28, Random Forest Classifier (RF)29, Gaussian Naïve Bayes Classifier (NB)30, Gradient Boosting Classifier (GB)31,32, and Multilayer Perceptron Classifier (MLP)33,34. Logistic Regression (LR)35 was used as a baseline. For learning process, the class weight was set to ‘balanced’. Single biomarker-based ML analysis used default parameters, whereas for multi-biomarker cases, parameters were tuned via GridSearchCV algorithm25. Normalized expression levels (-ΔCt) were min-max normalized per marker basis, and patients were randomly divided into a training set (75%) and a test set (25%). Classifiers were trained using train dataset, and evaluated on the test dataset. It is well known that a single random split can yield unstable or overly optimistic performance estimates, particularly in small or unbalanced datasets36,37,38. To mitigate this source of bias and ensure more reliable generalization assessment, we incorporated additional cross-validation analyses. Two complementary strategies, specifically Stratified K-Fold and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV), were employed to provide consistent and unbiased out-of-sample performance estimates39. Stratified K-Fold cross-validation maintains class balance across folds and offers robust evaluation for unbalanced datasets, whereas LOOCV iteratively evaluates each individual sample, maximizing data utilization and minimizing dependence on any single partition.

Feature selection for multimarker models

Recursive feature elimination with cross-validation (RFECV) was used with GB as the estimator and LOOCV as the scoring method39,40. The RFECV procedure was performed with all 20 urinary RNA markers initially. RFECV then proceeded by removing the least-informative marker at each step according to the GB estimator, and recomputed the LOOCV score after each step with reduced number of markers. In LOOCV with n patients, the data are split into n folds, where each fold holds out one patient for testing and fits the model on the remaining n − 1, to reduce dependence on any single random split. Compared with a simple train/test split, LOOCV provides more robust and unbiased estimates by iteratively using all samples for both training and validation41,42. Iteration proceeded until only a single marker remained, and the subset that maximized the LOOCV score was selected (Fig. 2a). This procedure yielded a fixed 9-RNA biomarker subset (PCA3, TMPRSS2:ERG, hsa-miR-125b-5p, hsa-miR-141-5p, hsa-miR-17-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p, hsa-miR-31-5p), which was then used consistently for all subsequent multivariate analyses.

Results

Diagnosis of PCa using urinary RNA markers

To develop a multiplexed qPCR-based test for PCa, we assessed 20 putative PCa urinary RNA biomarkers in a cohort of 112 patients with PCa and 51 patients with BPH. These 20 urinary RNAs were selected based on their biological roles in prostate cancer progression, prior evidence of diagnostic utility, and validation in our internal cohort. Canonical RNAs such as PCA3, MALAT1, and TMPRSS2:ERG were included9,43, along with 17 microRNAs that regulate androgen receptor signaling, PI3K/AKT/STAT3, EMT, and tumor suppressing pathways44,45. The detailed descriptions of target pathways, reported diagnostic performance, and internal cohort validation results for all 20 biomarkers are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. The two lncRNAs (MALAT1 and PCA3) and TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene were up-regulated in PCa, but all miRNA biomarkers were down-regulated in PCa (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 3). ROC curves for individual urinary RNA markers for the diagnosis of PCa showed that AUCs for two lncRNAs and the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene were 0.78 and 0.74, respectively. AUCs for a subset of miRNAs were high with a maximum of 0.85 for hsa-miR-222-3p (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 4).

Characterization of candidate urinary RNA biomarkers of PCa. (a) AUC values for single urinary RNA biomarkers for the diagnosis of PCa. ROC curves were constructed from expression levels for single urinary RNA biomarkers (Supplementary Fig. 1). (b) ROC curves for single urinary RNA biomarkers with six different ML classifiers. Each ML model was trained on the training dataset and ROC curves were constructed on the test set. (c) AUC values for the ROC curves in (b). (d) Stratified-K-Fold cross-validation (K = 51) scores. This unbiased indicator maintains the ratio of PCa to BPH in each fold.

Single-biomarker analysis by ML

Prior to the multi-marker approach, we first constructed and tested the performance of ML classifiers using single urinary RNA biomarkers. The normalized expression levels for 20 urinary RNA markers from the final cohort (112 PCa and 51 BPH) were used to train and evaluate the ML classifiers. Six different ML algorithms (SVC, RF, LR, NB, GB, MLP) representative of diverse ML approaches including those that are often used in clinical models were chosen for evaluation46,47. These ML classifiers were trained on the training dataset and the performance of each model was evaluated with the test dataset. Single biomarker-based classifiers showed variable performance depending on the choice of biomarker and ML algorithm (Fig. 1b,c, Supplementary Fig. 2a). It is often the case that the reported AUC could be overoptimized due to the randomized train/test set split instances36.

To correct this bias, we further performed cross-validation analysis using the Stratified-K-Fold and LOOCV37 (Fig. 1d). The maximum values of AUC and Stratified-K-Fold/LOOCV were 0.84 (hsa-miR-17-3p, model: SVC) and 0.864/0.859 (hsa-miR-125b-5p, model: SVC), respectively. We confirmed that ML classifier models can be successfully constructed using single biomarkers, and their performances compare favorably with previous models (Supplementary Table 5). However, this variability in performance also highlights the inherent limitations of a univariate approach, as a single marker is often insufficient to capture the full biological heterogeneity of a complex disease like prostate cancer6,11,12.

Multimarker analysis by ML

To overcome the reported limitations of univariate analyses, which capture only a single biological axis and are prone to variability across diverse pathological conditions, ML models with multiple markers were constructed and analyzed6,11,12,13,14,15. Multiple biomarker combinations have the potential to improve classification accuracy; however, the inclusion of insignificant terms in the model could negatively impact performance48. In particular, when applying machine learning to high-dimensional datasets, the outcome can be strongly dependent on both the feature combinations and the random data partitioning38,49. To address this issue, TRIPOD/PROBAST recommended resampling-based selection and validation rather than single-split workflows50,51. To identify the optimal combination of features among the 20 urinary RNA markers, we chose the RFECV algorithm to select informative biomarkers as an exploratory model with reduced bias while utilizing the complete experimental dataset40. RFECV was applied to the min-max normalized qPCR data, using GB as the estimator and LOOCV as the scoring method. For each round of selection step, RFECV removed a single least-informative marker by computing the LOOCV score with the GB estimator40. RFECV was initiated with all 20 biomarkers and proceeded until only one biomarker remained, with maximum LOOCV scores reported for the given number of features (Fig. 2a). This selection procedure yielded an optimized 9-RNA biomarker panel consisting of PCA3, TMPRSS2:ERG, hsa-miR-125b-5p, hsa-miR-141-5p, hsa-miR-17-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p, and hsa-miR-31-5p. This 9-RNA subset was then used consistently for all subsequent multivariate analyses. As a control, a 3-feature set composed of conventional PCa RNA markers (PCA3, MALAT1, and TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene) was constructed and analyzed7,52,53,54.

Multiple urinary RNA biomarker-based ML analysis for the diagnosis of PCa. (a) The optimal biomarker combination was selected through the RFECV algorithm with GB and LOOCV. The highest LOOCV score was observed when the number of features was 9. (b, c) ROC curves for multiple urinary RNA biomarker-based ML classifiers for the diagnosis of PCa. The number of features used for training is 3 in (b) and 9 in (c), respectively. The 3-feature combination consisting of MALAT1, PCA3, and TMPRSS2:ERG was introduced as a baseline for conventional biomarker combinations. The 9-feature combination obtained from the RFECV analysis in (a) consists of PCA3, TMPRSS2:ERG, hsa-miR-125b-5p, hsa-miR-141-5p, hsa-miR-17-3p, hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-30b-5p, hsa-miR-30c-5p, and hsa-miR-31-5p. (d) AUC values for the ROC curves in (b) and (c). (e) Stratified-K-Fold cross-validation (K = 51) scores for the trained ML classifiers in (b) and (c). (f, g) Feature importance was calculated using RF or GB for 3 features (f) and 9 features (g).

In our cohort, the multiplexed models achieved significantly higher AUC values compared with single biomarker-based models (Table 2, Fig. 2b–e, Supplementary Fig. 2b). Among all the classifiers tested, GB model with nine urinary RNA biomarkers demonstrated the best overall performance. While high AUC values may appear to indicate near-perfect discrimination, these values can be over-optimistic as a result of data overfitting or random data partitioning bias, particularly in small medical datasets. To ensure reliable evaluation of model performance and reduce this potential bias, we performed additional cross-validation analyses using Stratified K-Fold and LOOCV39,41,55. Both cross-validation methods provided consistent and robust internal validation scores (AUC 0.99, Stratified K-Fold 0.912, LOOCV 0.890), confirming that the GB model’s performance is expected to be stable. The bootstrap method was applied to compare ROC curves, indicating that the GB model with 9 markers could improve performance over all single biomarkers for non-ML ROC curves (hsa-miR-222-3p with AUC of 0.85; p < 0.00001; Supplementary Table 6) and ML models (GB model using hsa-miR-30c-5p with AUC of 0.81; p < 0.01; Supplementary Table 7). Feature importance analysis of the 9-biomarker combination using RF or GB indicated that miRNA markers contributed significantly with summed feature importance of 76.3% for RF and 80.1% for GB (Fig. 2f,g).

The ML decisions for different algorithms and biomarker choices were further analyzed based on the predictor values (0 ≤ BPH < 0.5, 0.5 ≤ PCa ≤ 1) (Fig. 3a,b). Notably, LR was not included due to its limited performance and SVC was not included since it does not provide predictor values. The limited number of error cases typically appeared near the threshold value of 0.5, reflecting the low prediction certainty for these error cases. The decision margin significantly increased for 9-marker combinations compared to 3-marker combinations, except for RF (Fig. 3c). Together, GB and MLP with 9 marker combinations showed the highest decision margin and unanimity in 37 out of 41 cases, with only one common error case, indicating that the performance could potentially be improved if multiple trained ML models are combined for decision-making.

Diagnostic performances of multiple urinary RNA biomarker-based ML analysis. (a, b) Predictor values calculated as decision probability for the test set using four different ML algorithms (RF, NB, GB, MLP). Predictor values using the 3-feature combination (a) and the 9-feature combination (b). The predictor value close to 1 indicates that the patient is likely a PCa patient, while the predictor value close to 0 indicates that the patient is likely a BPH patient. Open circles: predictor values for BPH patients; filled circles: predictor values for PCa patients. (c) Decision margin based on predictor values for individual patients. The decision margin has a value equal to the distance from the threshold (0.5), and the sign is positive when the diagnosis is correct and negative when the diagnosis is incorrect. In the box-and-whiskers plot, the ends of the box mark the first quartile (25%) and third quartile (75%). The two whiskers extend from the first quartile to the smallest value and from the third quartile to the largest value. The median is shown with a dashed line. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to compare the distribution of decision margin values for the 3- and 9-feature combinations (ns > 0.05, ** p = 0.001–0.01, *** p = 0.001–0.0001).

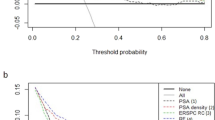

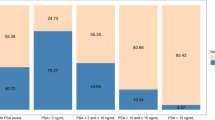

Classification of PSA gray zone patients using ML classifiers

Although PSA is a key diagnostic tool, management of patients with borderline PSA is not straightforward56. Thus, we assessed the ability of the ML classifiers by analyzing the subset of the cohort in the PSA gray zone to validate their robustness (Fig. 4a–d, Supplementary Fig. 2c). The trained ML classifiers had higher AUC values than serum PSA (AUC: 0.59; Supplementary Fig. 3) and generally high cross-validation scores. The GB algorithm with 9 biomarkers showed the best performance with AUC of an 1.00, with robust cross-validation scores at 0.885 for Stratified-K-Fold, and 0.865 for LOOCV. Together, these results indicate that ML classifiers with multiple urinary RNA markers could be a useful strategy with further developments.

Diagnostic performances of multiple urinary RNA biomarker-based ML analysis on PSA gray zone patients. Among the patient cohort, 96 patients (24 BPH, 72 PCa) with serum PSA levels of 3–10 ng/mL were selected for analysis. (a, b) ROC curves for six different ML algorithms using the 3-feature combination (a) and the 9-feature combination (b). Each ML model was trained on the training dataset and ROC curves were constructed on the test set. (c) AUC values for the ROC curves in (a) and (b). (d) Stratified-K-Fold cross-validation (K = 24) scores calculated for the trained ML classifiers in (a) and (b).

Discussion

In this study, we developed a diagnostic model for PCa, termed PCASSO, combining sophisticated ML techniques and simple qPCR assays on urinary RNA biomarkers from DRE-free whole urine samples. To explore the potential of multimarker ML models, well-established urinary markers such as PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG as well as several miRNAs were assayed as inputs to ML algorithms. Although there are no commercially available miRNA signatures, there are many that have been described in the literature with attractive characteristics including high stability in the blood and urine due to their association with proteins (such as Argonaute)57,58,59. To capture the highly complex relationship between inputs while minimizing potential over-optimization, the best feature combination was selected via the RFECV algorithm, resulting in a 9-biomarker combination that features both the well-known biomarkers and multiple miRNA species (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 8). The 9-biomarker ML model significantly improves predictive performance compared with any single RNA marker and the 3 conventional biomarker combinations7,52,53,54 (Table 2, Fig. 2b–e, Supplementary Fig. 2b). Among the different ML algorithms, GB showed the best performance in terms of AUC and cross-validation scores (AUC: 0.99, Stratified-K-Fold score: 0.912, LOOCV score: 0.890). In addition, feature importance analysis confirmed that miRNAs contribute to improve classifier accuracy and compare favorably with other well-established markers (Fig. 2f,g). The performance of ML classifiers was largely maintained when applied to the subset of the cohort with intermediate PSA levels (Fig. 4a–d, Supplementary Fig. 2c).

Our ML-based diagnostic classifier results compare favorably to serum PSA test and those from other early detection tests. First, the ML classifiers developed here need only a simple qPCR assay on DRE-free urinary RNA biomarkers, and therefore, could minimize patient discomfort, potentially without the high false positive rate known for the PSA test1,60. This feature may allow clinical application of ML models with further clinical validation and development in the future. As an example, we provide a potential workflow where all nine RNA markers from DRE-free urine are assayed concurrently, and the resulting ΔCt values are used as inputs to a pre-trained classifier to calculate the disease score for PCa (Supplementary Fig. 4). Second, our ML classifier showed diagnostic ability and robustness that compare favorably with other multivariable PCa diagnostic models. Logistic regression-based multivariable models typically reported relatively low specificity and/or sensitivity43,54,61 (Supplementary Table 5), whereas a manually constructed non-ML model required a time-consuming optimization process yet with limited robustness44. Commercially available biomarker tests could be more effective than PSA test alone, including 4Kscore (AUC: 0.82) and prostate health index (AUC: 0.70) that use blood samples, and PCA3 (AUC: 0.76) and SelectMDx (AUC: 0.86) that use post-DRE urine samples62. The PCASSO model with simple and cost-effective assays demonstrated robust classification accuracy for PCa upon biopsy, without resorting to prior clinical data, blood draw, and DRE (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10).

Further, it is well documented that prostate-derived RNAs are preferentially shed into urine63,64 such that our DRE-free urinary biomarker assay targets the medium with direct linkage and rich information on PCa. Meanwhile, prior studies showed that several urinary RNA biomarkers—most notably miR-375—are detectable in blood and are associated with metastatic disease and survival in advanced PCa/CRPC, suggesting potential prognostic utility65,66. Although challenges remain to elucidate the nature of differences in biomarker concentrations between urine and blood samples due to distinct compartments and different release/clearance kinetics, future work could explore paired urine-plasma samples for RNA biomarkers to evaluate the potential benefit of including blood marker levels alongside a urine-based diagnostic panel.

While we demonstrated that our ML classifiers showed robust performance in PCa diagnosis, further developments could be achieved by addressing certain limitations. First, our study is limited as an exploratory study using data from a single-country cohort of voluntarily participating Korean men (51 BPH, 112 PCa). Following TRIPOD-aligned guidance and methodological reviews, we chose to resort to cross-validation rather than a simple split sample because the dataset is used efficiently while providing realistic error estimates50,67. Two widely-used and complementary cross-validation procedures, stratified K-fold and LOOCV, were employed to approximate out-of-sample behavior and minimize overfitting, in line with recommendations for medical AI model development41,55. Although the GB model maintained high discrimination power in both the overall cohort and the PSA gray zone patients, the cross-validation results indicated a slight decrease in the model performance metrics within the PSA gray zone. This difference suggests that diagnostic performance for patients with borderline PSA levels could be affected by patient sample distributions and limited sample size. Future extension of the current exploratory work in an independent, multi-center cohort with controlled age and PSA levels would provide additional evaluation metrics for potential clinical utility68. Second, methods to elucidate the decision-making process of ML algorithms are often lacking. The ML classifiers provided the predictor values as the probability of algorithms’ predictions, helping to evaluate the performance of models and mostly reaching unanimity for multiple classifiers. Dissecting the reasons for misclassifications may provide a crucial aspect for model optimization. Third, no clinical parameters were considered in the ML classifiers. While our ML classifiers based solely on DRE-free urinary RNA markers showed robust performance, combining the models with novel imaging tests and other clinical parameters may further improve performance and robustness69. The non-invasive PCa screening via ML classifiers using DRE-free urine causes minimal side effects for patients, and may open doors to new ways of screening and monitoring the disease70,71.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included within the article and its additional file, and also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BPH:

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- Ct:

-

Cycle threshold

- DRE:

-

Digital rectal examination

- GB:

-

Gradient boosting classifier

- lncRNA:

-

Long noncoding RNA

- LOOCV:

-

Leave-one-out cross validation

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- miRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- MLP:

-

Multilayer perceptron classifier

- PCa:

-

Prostate cancer

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- qPCR:

-

Real-time quantitative PCR

- RF:

-

Random forest classifier

- RFECV:

-

Recursive feature elimination with cross validation

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal RNA

- SVC:

-

C-support vector classification

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590 (2020).

Heidenreich, A. et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur. Urol. 59, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039 (2011).

Wolf, A. M. et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: Update 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 60, 70–98. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20066 (2010).

Klotz, L. et al. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180 (2010).

Prensner, J. R., Rubin, M. A., Wei, J. T. & Chinnaiyan, A. M. Beyond PSA: The next generation of prostate cancer biomarkers. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 127rv123. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003180 (2012).

Eskra, J. N., Rabizadeh, D., Pavlovich, C. P., Catalona, W. J. & Luo, J. Approaches to urinary detection of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 22, 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-019-0127-4 (2019).

Wang, F. et al. Development and prospective multicenter evaluation of the long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 as a diagnostic urinary biomarker for prostate cancer. Oncotarget 5, 11091–11102. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2691 (2014).

Mao, Z. et al. Diagnostic performance of PCA3 and hK2 in combination with serum PSA for prostate cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 97, e12806. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012806 (2018).

Koo, K. M., Wee, E. J., Mainwaring, P. N. & Trau, M. A simple, rapid, low-cost technique for naked-eye detection of urine-isolated TMPRSS2: ERG gene fusion RNA. Sci. Rep. 6, 30722. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30722 (2016).

Fabris, L. et al. The potential of microRNAs as prostate cancer biomarkers. Eur. Urol. 70, 312–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.054 (2016).

Juracek, J., Madrzyk, M., Stanik, M. & Slaby, O. Urinary microRNAs and their significance in prostate cancer diagnosis: A 5-Year update. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14133157 (2022).

Jain, G. et al. Urinary extracellular vesicles miRNA-A new era of prostate cancer biomarkers. Front. Genet. 14, 1065757. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1065757 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Targeted proteomics identifies liquid-biopsy signatures for extracapsular prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 7, 11906. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11906 (2016).

McKiernan, J. et al. A prospective adaptive utility trial to validate performance of a novel urine exosome gene expression assay to predict high-grade prostate cancer in patients with prostate-specific antigen 2–10ng/ml at initial biopsy. Eur. Urol. 74, 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.019 (2018).

Tomlins, S. A. et al. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG plus PCA3 for individualized prostate cancer risk assessment. Eur. Urol. 70, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.039 (2016).

Visser, W. C. H. et al. Clinical use of the mRNA urinary biomarker SelectMDx test for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 25, 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-022-00562-1 (2022).

Connell, S. P. et al. Integration of urinary EN2 protein & cell-free RNA data in the development of a multivariable risk model for the detection of prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13092102 (2021).

Frick, J. & Aulitzky, W. Physiology of the prostate. Infection 19(Suppl 3), S115-118. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01643679 (1991).

Alarcon-Zendejas, A. P. et al. The promising role of new molecular biomarkers in prostate cancer: From coding and non-coding genes to artificial intelligence approaches. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 25, 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-022-00537-2 (2022).

Karamık, K. et al. Stage pT0 prostate cancer: A single-center study and literature review. J. Urol. Surg. 8, 255–260. https://doi.org/10.4274/jus.galenos.2021.2021.0039 (2021).

Epstein, J. I. et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: Definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/pas.0000000000000530 (2016).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinf. 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 (2011).

Carpenter, J. & Bithell, J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat. Med. 19, 1141–1164. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9%3c1141::aid-sim479%3e3.0.co;2-f (2000).

Young, I. T. Proof without prejudice: use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the analysis of histograms from flow systems and other sources. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 25, 935–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/25.7.894009 (1977).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Reback, J. et al. Pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas 1.0.3 (v1.0.3). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3715232 (2020).

Chang, C. C. & Lin, C. J. LIBSVM: A library for support vector machines. ACM T. Intel. Syst. Tec. 2, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/1961189.1961199 (2011).

Platt, J. C. in Advances in Large Margin Classifiers Ch. 5, 61–74 (MIT Press, 1999).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Zhang, H. in International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference (FLAIRS) 562–567 (AAAI Press).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013203451 (2001).

Friedman, J. H. Stochastic gradient boosting. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 38, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9473(01)00065-2 (2002).

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. in International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS) (eds Yee, W. T. & Mike, T.) 249–256 (PMLR).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. in IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 1026–1034 (IEEE).

Fan, R. E., Chang, K. W., Hsieh, C. J., Wang, X. R. & Lin, C. J. LIBLINEAR: A library for large linear classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 1871–1874 (2008).

An, C. et al. Radiomics machine learning study with a small sample size: Single random training-test set split may lead to unreliable results. PLoS ONE 16, e0256152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256152 (2021).

Xu, Y. & Goodacre, R. On splitting training and validation set: A comparative study of cross-validation, bootstrap and systematic sampling for estimating the generalization performance of supervised learning. J. Anal. Test 2, 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41664-018-0068-2 (2018).

Varma, S. & Simon, R. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinform. 7, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-7-91 (2006).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. H. The Elements of Statistical Learning Vol. 1 (Springer, 2001).

Guyon, I., Weston, J., Barnhill, S. & Vapnik, V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 46, 389–422 (2002).

Bradshaw, T. J., Huemann, Z., Hu, J. & Rahmim, A. A guide to cross-validation for artificial intelligence in medical imaging. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 5, e220232. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.220232 (2023).

Cheng, H., Garrick, D. J. & Fernando, R. L. Efficient strategies for leave-one-out cross validation for genomic best linear unbiased prediction. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 8, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-017-0164-6 (2017).

Hessels, D. et al. Detection of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts and prostate cancer antigen 3 in urinary sediments may improve diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5103–5108. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0700 (2007).

Fredsoe, J. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic microRNA biomarkers for prostate cancer in cell-free urine. Eur. Urol. Focus 4, 825–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2017.02.018 (2018).

Urabe, F. et al. Large-scale circulating microRNA profiling for the liquid biopsy of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 3016–3025. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2849 (2019).

Ahsan, M. M., Luna, S. A. & Siddique, Z. Machine-learning-based disease diagnosis: A comprehensive review. Healthcare (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030541 (2022).

Sadr, H. et al. Unveiling the potential of artificial intelligence in revolutionizing disease diagnosis and prediction: A comprehensive review of machine learning and deep learning approaches. Eur. J. Med. Res. 30, 418. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-025-02680-7 (2025).

Rainio, O., Teuho, J. & Klén, R. Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14, 6086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56706-x (2024).

de Hond, A. A. H. et al. Perspectives on validation of clinical predictive algorithms. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00832-9 (2023).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMJ 350, g7594. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7594 (2015).

Andaur Navarro, C. L. et al. Risk of bias in studies on prediction models developed using supervised machine learning techniques: systematic review. BMJ 375, n2281. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2281 (2021).

Hessels, D. et al. DD3(PCA3)-based molecular urine analysis for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 44, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00201-x (2003).

Nguyen, P. N. et al. A panel of TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcript markers for urine-based prostate cancer detection with high specificity and sensitivity. Eur. Urol. 59, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.11.026 (2011).

Laxman, B. et al. A first-generation multiplex biomarker analysis of urine for the early detection of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3224 (2008).

Wilimitis, D. & Walsh, C. G. Practical considerations and applied examples of cross-validation for model development and evaluation in health care: Tutorial. JMIR AI 2, e49023. https://doi.org/10.2196/49023 (2023).

Ross, T., Ahmed, K., Raison, N., Challacombe, B. & Dasgupta, P. Clarifying the PSA grey zone: The management of patients with a borderline PSA. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 70, 950–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12883 (2016).

Schwarzenbach, H., Nishida, N., Calin, G. A. & Pantel, K. Clinical relevance of circulating cell-free microRNAs in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 11, 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.5 (2014).

Rana, S., Valbuena, G. N., Curry, E., Bevan, C. L. & Keun, H. C. MicroRNAs as biomarkers for prostate cancer prognosis: A systematic review and a systematic reanalysis of public data. Br. J. Cancer 126, 502–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-021-01677-3 (2022).

Palanisamy, H., Manoharan, J. P. & Vidyalakshmi, S. Prognostic microRNAs as biomarkers for prostate cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 20, 297–303. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcrt.jcrt_1469_22 (2024).

Guo, D. P. et al. The research implications of prostate specific antigen registry errors: Data from the veterans health administration. J. Urol. 200, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2018.03.127 (2018).

Salami, S. S. et al. Combining urinary detection of TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 with serum PSA to predict diagnosis of prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 31, 566–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.04.001 (2013).

Becerra, M. F., Atluri, V. S., Bhattu, A. S. & Punnen, S. Serum and urine biomarkers for detecting clinically significant prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 39, 686–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.02.018 (2021).

Tinzl, M., Marberger, M., Horvath, S. & Chypre, C. DD3PCA3 RNA analysis in urine–A new perspective for detecting prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 46, 182–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2004.06.004 (2004).

Bandini, E. Urinary microRNA and mRNA in tumors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2292, 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-1354-2_6 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Exosomal miR-1290 and miR-375 as prognostic markers in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 67, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.035 (2015).

Bryant, R. J. et al. Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 106, 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.595 (2012).

Moons, K. G. et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, W1-73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0698 (2015).

Collins, G. S. et al. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): From development to external validation. BMJ 384, e074819. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-074819 (2024).

Hagens, M. J. et al. Diagnostic performance of a magnetic resonance imaging-directed targeted plus regional biopsy approach in prostate cancer diagnosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 40, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2022.04.001 (2022).

Kawakami, E. et al. Application of artificial intelligence for preoperative diagnostic and prognostic prediction in epithelial ovarian cancer based on blood biomarkers. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 3006–3015. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3378 (2019).

Catto, J. W. et al. The application of artificial intelligence to microarray data: identification of a novel gene signature to identify bladder cancer progression. Eur. Urol. 57, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.029 (2010).

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Basic Science Institute [2021R1A6C101A390], National Research Foundation of Korea [RS-2025-00561294, Leaders in INdustry-university Cooperation 3.0] and Korea Health Industry Development Institute [RS-2023-00304637]. The sponsors played no direct role in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.K and J.M.K. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. H.G., T.H., and J.W.K contributed equally, and each reserves the right to place their name first. C.S.K. and J.M.K. conceived and designed the study. H.G., J.W.K., Y.K., and B.L. acquired the data. T.H., H.G., and J.W.K analyzed and interpreted the data. T.H., H.G., J.W.K., and J.M.K. drafted the manuscript. M.K.W., K.Y.C., C.S.K., and J.M.K. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. H.G., T.H., and J.W.K. performed the statistical analysis. K.Y.C., C.S.K., and J.M.K. obtained funding. Y.K. and B.L. provided administrative, technical, and material support. C.S.K. and J.M.K. supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.H., K.Y.C. and J.M.K. are the named inventors on a provisional patent application related to the technologies developed in this work. H.G., J.W. K., Y.K., B.L., M.K.W., and C.S.K. declare no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental plan was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Republic of Korea/IRB No. 2019-1312). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The protocols for the human urine assay were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Asan Medical Center, and the human urine assays were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goh, H., Heo, T., Kim, J. et al. Prostate cancer diagnosis using sensitive and sophisticated machine learning classifiers based on non-invasive urinary RNA biomarkers (PCASSO). Sci Rep 16, 2445 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32334-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32334-x