Abstract

This study aimed to characterize the phytochemicals in Ficus hispida fruits and evaluate the anticancer potential of gallic acid against breast cancer using in-silico and in-vitro approaches. The objectives were to identify bioactive compounds using LC-MS, assess gallic acid’s binding affinity with breast cancer-related targets via molecular docking and dynamics, and validate its cytotoxicity and apoptotic effects in breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cells. Ethyl acetate extract of Ficus hispida fruits was prepared via Soxhlet extraction and analyzed using LC-MS/MS. Molecular docking studies were performed to evaluate gallic acid’s interactions with breast cancer proteins (2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha, 1P7K-Anti-ssDNA antibody Fab fragment, 5OTE-Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta), followed by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for stability analysis. In-vitro cytotoxicity (MTT assay) and apoptosis detection (AO/EB staining, DAPI staining) were conducted on MDA-MB-231 cells. LC-MS analysis identified key phytochemicals, including gallic acid (m/z 169.14), quercetin (m/z 302.33), and β-sitosterol (m/z 414.58). Molecular docking revealed strong binding of gallic acid to Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha (-6.2 kcal/mol), stabilized by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. MD simulations confirmed stable protein-ligand complexes with an RMSD of 2.1 Å for the protein and 3.2 Å for the ligand. In vitro studies showed the dose-dependent cytotoxicity of gallic acid against MDA-MB-231 cells, with an IC₅₀ of 15–20 µg/mL and 34.80% viability at 20 µg/mL. Apoptosis was confirmed through nuclear fragmentation and chromatin condensation. Ficus hispida fruits are rich in bioactive compounds, particularly gallic acid, demonstratinga strong binding affinity to breast cancer targets and potent cytotoxic effects against MDA-MB-231 cells. These findings highlight its potential as a therapeutic candidate for breast cancer treatment, warranting further clinical exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is among the most frequently diagnosed cancers around the world and is a significant cause of illness and death in women1. Each year, more than 2.3 million new cases are identified, making it the primary reason for cancer-related mortality in the female population2. While significant progress has been made in treatments like chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapies, issues such as resistance to drugs, harmful side effects, and toxicity remain significant obstacles in effective management3. These limitations have driven researchers to explore alternative therapeutic approaches, particularly plant-derived bioactive compounds, which offer promising anticancer properties with minimal side effects. In this context, Ficus hispida Linn., a tropical fig species widely used in traditional medicine for various ailments4, emerges as a potential candidate for anticancer drug discovery due to its rich phytochemical composition5.

The fruits of Ficus hispida have been traditionally utilized for their medicinal properties, including anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and wound-healing effects. Recent scientific investigations into the phytochemical profile of Ficus hispida reveal the presence of bioactive compounds such as β-sitosterol, β-amyrin, hispidin, tannins, and gallic acid derivatives6. Among these constituents, gallic acida naturally occurring phenolic compoundhas attracted considerable attention for its potent antioxidant and anticancer activities. Gallic acid has demonstrated efficacy against various cancer types through mechanisms such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, and caspase-mediated apoptosis7. Its ability to modulate key molecular pathways involved in cancer progression further underscores its therapeutic potential.

Gallic acid exerts multimodal anticancer effects by targeting several molecular pathways critical to tumor growth and survival. It inhibits the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway while activating the MAPK pathway, thereby promoting apoptosis in cancer cells. Additionally, gallic acid disrupts β-catenin nuclear translocation and alters the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in favor of apoptosis8,9. In breast cancer models, particularly breast cancer (MDA-MB-231 cells) subtypes, gallic acid has shown specificity by inducing apoptosis and suppressing metastasis-associated markers such as matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9)10,11. These findings highlight gallic acid’s potential as a targeted therapeutic agent against aggressive breast cancer phenotypes.

MDA-MB-231 is an aggressive and invasive triple-negative breast cancer cell line characterized by the absence of estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors. It shows properties of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and has high metastatic potential, especially to bone, brain, and lungs. This cell line is extensively utilized in research focused on cancer progression, metastasis, and drug resistance.

MDA-MB-231 cells uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of suppressors, resistance to apoptosis, immortality, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, altered metabolism, and immune escape, driving tumor growth, progression, and therapeutic resistance. Gallic acid exerts anti-cancer effects in breast cancer by regulating critical signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK. It inhibits the PI3K/Akt pathway, reducing phosphorylation of key proteins, which suppresses metastasis-related factors like β-catenin and matrix metalloproteinases. Simultaneously, it activates MAPK pathways including JNK and p38, triggering increased reactive oxygen species and apoptosis, thereby hindering cancer cell proliferation and invasion. This multifaceted modulation ultimately promotes cell death and curbs tumor progression. The 2VCJ structure represents the Estrogen Receptor-α ligand-binding domain, important in ER-positive breast cancer12. Natural compound genistein and resveratrol bind ER, altering gene activity and slowing growth. The Anti-ssDNA antibody Fab fragment structure is Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein; curcumin and gossypol inhibit Bcl-2, restoring cell death13. 5OTE corresponds to HER2 kinase, often overexpressed in aggressive breast cancer; EGCG and berberine inhibit HER2 signaling, reducing tumor growth and spread14. These phytochemicals target key breast cancer pathways, promoting apoptosis and blocking proliferation.

Despite the promising pharmacological properties of gallic acid and its presence in Ficus hispida fruits, scientific validation of the plant’s anticancer efficacy remains limited. Gallic acid is a natural phenolic acid found in various plants like gallnuts, tea leaves, and oak bark. It possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties. Gallic acid is widely studied for its role in protecting cells from oxidative damage and its potential therapeutic applications in health and disease. While preliminary studies have demonstrated cytotoxic effects of Ficus hispida extracts on cancer cell lines, comprehensive phytochemical characterization and mechanistic evaluations are lacking15,16. Furthermore, the synergistic interactions between gallic acid and other phytochemicals present in Ficus hispida remain unexplored. Understanding these interactions could pave the way for developing more effective plant-based therapies with enhanced therapeutic indices. This study addresses these research gaps by adopting an integrated approach combining phytochemical characterization with pharmacological evaluation.

Materials and methods

Ficus hispida fruit collection and identification

Ficus hispida was collected from the wild in Vaddeswaram, Andhra Pradesh, India (16.441554°N, 80.615216°E) on May 22, 2025, at 1:26 PM IST, following guidelines under Dr. K. Deepti’s supervision. Identification was confirmed by Prof. S. B. Padal, Department of Botany, Andhra University, by examining morphological traits against taxonomic literature. The specimen, verified as Ficus hispida (family Moraceae), was deposited in the Andhra University Herbarium (Code: AUV) with specimen number 25,599 (Fig. 1).

Extraction hot continuous Extraction-Soxhlet

500 g of shade-dried Ficus hispida fruits was ground and placed in a filter paper thimble, which was loaded into chamber E of a Soxhlet apparatus. Ethyl acetate, chosen for its efficiency in dissolving a wide range of phytochemicals, was heated in flask A, vaporized, and condensed in condenser D before dripping onto the plant material. The extraction process relied on continuous solvent recycling, facilitated by a siphon mechanism that transferred liquid back to flask A once the chamber reached a specific level. This cyclic process thoroughly extracted bioactive compounds from the plant material. The procedure continued until a drop of solvent from the siphon tube evaporated without residue, indicating completion. The yield of extract is calculated by dividing the weight of the dried extract by the initial weight of the dried plant material, then multiplying by 100 to express it as a percentage. The resulting crude ethyl acetate extract, saturated with bioactive compounds, was carefully preserved for subsequent phytochemical analysis17,18.

Phytochemical analysis by using LC-MS analysis

The ethyl acetate extract underwent molecular weight analysis using an LC-MS/MS system (Shimadzu 8045) (12). The crude extract 0.2 mg was diluted to 1000 µL, vortexed immediately, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through sterile syringe filters, and the filtrate was stored at 18 °C for phytochemical studies. 10 µL supernatant was injected. The mobile phases comprised 0.5% acetic acid (v/v) and pure methanol. The PDA detector (HPLC, 340 nm wavelength) operated with a column temperature of 30 °C. The mass spectrometer used positive ionization mode, scanning 150–1000 m/z, with a capillary voltage of 3.50 kV, cone voltage of 30 V, extractor voltage of 3 V, gas flow of 30 L/h, and collision gas flow of 0.18 ml/min.

Molecular docking

Compounds identified via LC-MS analysis were selected for in silico studies. Molecular docking simulations using AutoDock 4.2.6 investigated interactions between Gallic acid and breast cancer proteins (Estrogen Receptor Alpha - ERα, PDB ID: 1P7K-Anti-ssDNA antibody Fab fragment), Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2, PDB ID: 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha), and Progesterone Receptor (PR, PDB ID: 5OTE-Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta)19. Protein and ligand 3D structures were converted to pdbqt format, with hydrogens added to enhance flexibility20. A grid box (0.3 Å spacing) was positioned for 1P7K (53 × 47 × 58 Å), 2VCJ (32 × 14 × 20 Å) and 5OTE (19 × 1 × 18 Å), around each protein’s active site to capture ligand binding regions. The active site of the individual proteins was determined using PrankWeb server (https://prankweb.cz/) and re-verified using Proteins Plus (https://proteins.plus/) web-based tool. The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) optimized conformational sampling, employing 3 independent runs per target, each generating 50 docking solutions21. Parameters included a population size of 500, 2.5 million energy evaluations, and 27 generations. Simulations aimed to identify optimal Gallic acid binding conformations, analyzing affinity and interaction patterns to guide experimental validation. Results were stored for binding mode and energy analysis, supporting potential drug design strategies.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using Desmond 2020.1 to evaluate the stability of a protein-ligand complex with gallic acid22. The system was set up with the OPLS-2005 force field and an explicit solvent model using SPC water molecules within a periodic boundary solvation box measuring 10 × 10 × 10 ų. Sodium ions (Na⁺) were added to neutralize the system’s electrical charge, and a solution of 0.15 M NaCl was introduced to mimic physiological conditions. The simulation protocol included an initial equilibration phase, where the protein-ligand complexes were restrained and subjected to a 10-nanosecond NVT ensemble, followed by a 12-nanosecond NPT ensemble for minimization and equilibration. During the production run, a simulation duration of 200 nanoseconds was employed with a time step of 2 femtoseconds. Temperature control was achieved using the Nose-Hoover chain coupling method, while pressure was maintained at 1 bar using the Martyna-Tuckerman-Klein barostat technique with a relaxation time of 2 picoseconds23. Long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald method, and short-range Coulomb interactions were limited to a cutoff radius of 9 Å24. Bonded forces were computed using the RESPA integrator with a time step of 2 femtoseconds. Several key parameters were analyzed to assess the stability of the MD simulations, including root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and hydrogen bond count (H-bonds). These metrics provided valuable insights into the conformational stability, compactness, flexibility, and interaction persistence of the protein-ligand complex under near-physiological conditions25.

Binding free energy analysis

The molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA) method was employed to determine the binding free energies of ligand-protein complexes. Using the Python script thermal mmgbsa.py, energy values were derived from the simulation trajectory by applying the VSGB solvation model and OPLS5 force field. The analysis focused on the final 50 frames, utilizing a 1-step sampling size for computation26,27. The MM-GBSA binding free energy (kcal/mol) was calculated through additive contributions from distinct energy components, including Coulombic and van der Waals interactions, covalent bonds, hydrogen bonding, lipophilic effects, ligand/protein solvation energies, and self-contact corrections28. This approach systematically combines these thermodynamic terms to quantify molecular affinity. The equation used to calculate ΔGbind is the following:

Where.

-

ΔGbind: Represents the total binding free energy, quantifying molecular interaction strength.

-

ΔGMM: Derived from gas-phase energy differences between the ligand-protein complex and the isolated protein/ligand (electrostatic, van der Waals, covalent, and hydrogen bonding contributions).

-

ΔGSolv: Reflects solvation energy changes, computed as the difference between the solvated complex and the sum of individually solvated protein and ligand.

-

ΔGSA: Captures solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) effects, comparing surface energy changes between bound and unbound states.

In-vitro breast cancer activity of Gallic acid

The MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cell line at passage 11, acquired from NCCS (Pune, India), was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (penicillin 100 U/ml and streptomycin 100 µg/ml). The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. For cytotoxicity assessment, MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) was prepared by dissolving 50 mg powder in PBS, filter-sterilized using 0.45 μm membranes, and stored protected from light at 4 °C. Post-trypsinization, viable cells were quantified via hemocytometer and plated in 96-well plates at 10⁴ cells/well for 24-hour adhesion. Gallic acid treatments (5–25 µg/ml) were administered for 24 h, followed by MTT incubation (4 h) and formazan dissolution using DMSO. 0.1% DMSO was used as a control. Absorbance measurements at 540 nm enabled calculation of proliferation inhibition using the formula: Inhibition (%) = (Control OD − Treated OD/Control OD) × 100. IC50 values were determined through nonlinear regression of dose-dependent response graphs. Experimental protocols included triplicate independent trials for statistical robustness29,30.

Fluorescence microscopy for apoptosis detection in breast cancer cells

Apoptotic cell death in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells was assessed via fluorescence microscopy using Acridine Orange (AO) and Ethidium Bromide (EB) as per Baskic et al. (2006). AO permeates all cells, staining viable/nonviable cells green (binding dsDNA) or red (binding ssRNA), while EB selectively stains membrane-compromised nonviable cells red (intercalating DNA). Cells were categorized into four types: viable (bright green, organized nuclei), early apoptotic (green nuclei with chromatin condensation), late apoptotic (orange-red nuclei with fragmented chromatin), and necrotic (uniform orange-red nuclei without condensation). For analysis, cells (5 × 10⁴/well in 6-well plates) were treated with gallic acid (15–20 µg/ml) for 24 h, detached, washed with 1% PBS, and stained with AO/EB (1:1 ratio, 100 µg/ml each) for 5 min. Fluorescent images (20× magnification) were captured immediately post-staining to evaluate chromatin morphology and viability status31.

DAPI staining for nuclear apoptosis assessment

Morphological changes in MDA-MB-231 cells were analyzed using a phase-contrast microscope (Zoe Fluorescent Cell Imager, Bio-Rad). Cells (5 × 10⁴/well in 6-well plates) were treated with gallic acid for 24 h, washed with PBS (pH 7.4), and observed for structural alterations. For nuclear analysis, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (10 min, room temperature), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS (10 min), and stained with 0.5 µg/ml DAPI (15 min, 37 °C, light-protected). Apoptotic nuclei, characterized by intense staining, chromatin condensation, or fragmentation, were visualized under fluorescence microscopy (Bio-Rad Zoe Imager)32.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were conducted in triplicate every time to ensure data accuracy and consistency. Statistical evaluation was performed using GraphPad Prism software. Both one-way ANOVA and the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test were employed to analyze differences between groups. A 95% confidence level was established to determine the statistical significance of the results, enhancing the rigour and reliability of the findings. This comprehensive approach allowed for a thorough assessment of treatment effects and validation of conclusions.

Results and discussion

Phytochemical analysis of Ficus hispida Ethyl acetate extract by LC-MS

Ficus hispida ethyl acetate extract yields 80% by using the Soxhlet method. LC-MS analysis of the Ficus hispida ethyl acetate extract revealed the presence of several key phytochemicals, as indicated by their characteristic m/z values. Flavonoids, specifically Quercetin (m/z 302.33 ES+) and Kaempferol (m/z 284.26 ES+), were detected, aligning with previous reports of flavonoid content in Ficus species. These compounds are known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Phenolic acids were also identified, gallic acid (m/z 169.14 ES-) and Caffeic acid (m/z 180.18 ES+). Gallic acid, a simple phenolic compound, contributes to the extract’s potential antioxidant activity, while caffeic acid is associated with various biological activities, including anticancer effects. Terpenoids such as Lupeol (m/z 434.48 ES+) and β-sitosterol (m/z 414.58 ES+) suggest potential triterpenoid and sterol content. Lupeol has demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and anti-angiogenic properties. β-sitosterol, a phytosterol, is known for its cholesterol-lowering and potential anticancer activities. The identification of Coumarins, namely Psoralen (m/z 137.10 ES-) and Bergapten (m/z 215.04 ES), is also notable. These compounds are known for their photosensitizing and potential anticancer effects (Table 1).

Molecular docking

The molecular docking analysis of Gallic acid with the 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha protein, yielding a binding energy of -6.2 kcal/mol, suggests a moderately strong interaction, indicating potential biological relevance (Fig. 2A). The left panel of the image illustrates the three-dimensional conformation of the protein-ligand complex, where the protein’s secondary structures-α-helices (blue and green), β-sheets (yellow), and loops (orange)-are distinctly represented, with Gallic acid (red) positioned within the binding pocket. The right panel highlights key interacting residues and their respective binding interactions. Conventional hydrogen bonds, crucial for ligand stabilization, are observed between Gallic acid and Asn A:137, while Met A:98 engages in a π-sulfur interaction, contributing to binding affinity. Additional π-alkyl interactions with Ala A:55 further stabilize the ligand, and van der Waals forces with residues like Ile A:91, Ser A:32, and Val A:186 enhance molecular complementarity. The docking grid selection and interaction profile suggest that Gallic acid effectively binds within the pocket, forming stabilizing interactions predominantly through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts, which could be explored for further computational and experimental validation in drug design studies.

(A) Molecular docking analysis of gallic acid with the protein 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha. (Left panel) The 3D structure of 2VCJ is shown in a ribbon representation, with beta-sheets in yellow, alpha-helices in blue, and loops in green. The protein surface is displayed in a semi-transparent white overlay, highlighting the binding pocket. Gallic acid, the docked ligand, is represented in red, positioned within the active site. (Right panel) A 2D interaction diagram of gallic acid with key amino acid residues of 2VCJ. (B) The image represents a molecular docking result, depicting the interaction between a ligand and a protein. The left panel shows the 3D structure of a protein in a ribbon format with a surface representation, where the ligand is bound within the active site, highlighted in red. The protein structure is colored in a rainbow gradient, suggesting secondary structural elements such as beta-sheets (arrows) and alpha-helices (coils). The right panel presents a 2D interaction diagram of the ligand, illustrating its interactions with specific amino acid residues.(C) Molecular docking interaction analysis of gallic acid with 5OTE-Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta. The left panel displays the 3D representation of the protein-ligand complex, where 5OTE-Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta is shown as a ribbon model with secondary structures colored (blue, green, yellow, and orange), and the molecular surface in white. Gallic acid is represented as a red stick model within the binding pocket. The right panel provides a 2D schematic of ligand interactions with surrounding residues.

The docking analysis between 1P7K-Anti-ssDNA antibody Fab fragment and Gallic acid reveals a binding energy of −4.8 kcal/mol, indicating a moderate binding affinity. Several key interactions are observed: conventional hydrogen bonds (green dashed lines) are formed with TYR-175 and THR-110, contributing to ligand stabilization. van der Waals interactions (light green circles) involve GLU-148, SER-108, VAL-109, ALA-88, and VAL-89, enhancing overall binding. Pi-alkyl interactions (pink dashed lines) are observed between the ligand’s aromatic ring and PRO-41, which play a role in hydrophobic stabilization. Additionally, carbon-hydrogen bonds are present, further strengthening ligand affinity (Fig. 2B). The specific positioning and interactions suggest that the ligand is well accommodated within the binding pocket, with a combination of hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces contributing to the stability of the complex. This docking study provides insights into the potential mechanism of ligand binding. It highlights key residues that might be crucial for receptor-ligand recognition, which could be useful for further drug design and optimization.

The molecular docking results between the protein 5OTE-Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta and gallic acid reveal a binding energy of −5.6 kcal/mol, suggesting moderate binding affinity (Fig. 2C). The structural visualization highlights multiple key interactions stabilizing the ligand within the binding pocket. Conventional hydrogen bonds, depicted in green, form between gallic acid and residues such as ASP218, ASP154, GLU124, and LYS105, enhancing binding specificity. Pi interactions play a significant role in stabilizing the ligand, with Pi-sigma and Pi-sulfur interactions observed between the aromatic system of gallic acid and MET153, while Pi-alkyl interactions with hydrophobic residues such as ALA217 contribute further to stabilization. Van der Waals forces, though non-specific, are widely distributed across the pocket, involving residues such as LEU128, THR137, TYR155, LEU207, and PHE219, supporting the ligand in the binding site. Notably, unfavorable donor-donor interactions (highlighted in red) suggest steric hindrances or repulsions within the binding cavity that might slightly impact binding efficiency. The combination of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions ensures a stable binding conformation, but the moderate binding energy suggests that gallic acid may act as a weak to moderate inhibitor or modulator of 5OTE, warranting further refinement for potential optimization in drug design.

Molecular dynamics analysis of 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha Gallic acid complex stability

A 200-ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was conducted to evaluate the structural stability and convergence of the 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha protein complexed with gallic acid. The study revealed consistent conformational stability, with root mean square deviation (RMSD) values of 2.1 Å for the Cα-backbone and 3.2 Å for the ligand (Fig. 3A), both within acceptable thresholds for stable biomolecular systems. These low deviations suggest robust ligand-protein binding and equilibrium attainment. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis showed minimal residue displacements (< 3 Å) across the protein (Fig. 3B), indicating rigid tertiary structure maintenance in the ligand-bound state. Compactness metrics derived from the radius of gyration (Rg) revealed a moderate reduction from 17.0 Å to 16.9 Å (Fig. 3C), consistent with structural tightening upon ligand interaction. Hydrogen bond analysis demonstrated persistent formation of two intermolecular bonds over the simulation (Fig. 3D), reinforcing the complex’s thermodynamic stability. Collectively, these metricsstable RMSD trajectories, low residue flexibility, enhanced compactness, and sustained hydrogen bonding validate the high-affinity interaction between gallic acid and the 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha binding site, underscoring the complex’s suitability for further pharmacological exploration.

A 200-nanosecond molecular dynamics simulation was conducted for the 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha gallic Acid complex. (A) The RMSD plot displays the structural deviations, with the black line representing the protein and the red line indicating the ligand. (B) The RMSF graph shows the fluctuations of the Cα backbone of the protein when bound to the ligand. (C) The radius of gyration (Rg) plot illustrates the compactness of the Cα backbone in the protein-ligand complex. (D) The number of hydrogen bonds formed between the protein and ligand throughout the simulation is also presented.

Molecular mechanics generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA) calculations

Using the MD simulation trajectory, the binding free energy and its individual energy components were calculated for the 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha gallic acid complex via the MM-GBSA method. As shown in Table 2, the primary factors contributing to the overall binding free energy (ΔGbind) and the stability of the complex were the Coulombic (ΔGbindCoulomb), van der Waals (ΔGbindvdW), and lipophilic (ΔGbindLipo) interactions. At the same time, ΔGbindCovalent and ΔGbindSolvGB contributed to the instability of the corresponding complexes. The 2VCJ-Heat shock protein HSP90-alpha bound to the gallic acid complex showed comparatively higher binding free energy. These findings highlight the potential of gallic acid in association with 5UGB-Serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK beta, demonstrating its effective binding to the target protein and its capacity to form stable protein-ligand complexes.

In-vitro breast cancer activity of Gallic acid

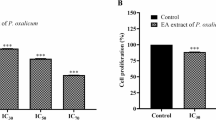

Gallic acid demonstrated potent dose-dependent anti-breast cancer activity in MDA-MB-231 cells, with cell viability decreasing from 84.88% ± 3.78 at 5 µg/ml to 19.72% ± 1.74 at 25 µg/ml, compared to untreated controls (100% viability). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) derived from dose-response curves fell between 15 µg/ml (56.19% viability) and 20 µg/ml (34.80% viability), indicating strong cytotoxic effects. Low standard deviations (< 4%) across triplicate experiments underscore the reproducibility of these results, supporting gallic acid’s potential as a therapeutic candidate for triple-negative breast cancer (Figs. 4 and 5). Figure 5, a photomicrograph (20× magnification), illustrates morphological changes in MDA-MB-231 cells induced by gallic acid treatment at 15 µg/ml and 20 µg/ml concentrations for 24 h. Observed alterations include cell shrinkage, detachment, membrane blebbing, and distorted shapes, as compared to the control group, which exhibited normal intact cell morphology. Images were captured using a Bio-Rad Fluorescent Microscope. Phytochemicals inhibit cancer cell growth through multiple mechanisms, including induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and suppression of angiogenesis. Compounds like curcumin and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) disrupt mitochondrial function, activate caspases, and modulate pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, facilitating cancer cell death. They also interfere with key signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, and MAPK, which are crucial for cell proliferation and survival. Phytochemicals like sulforaphane target cancer stem cells, reducing tumor recurrence. By simultaneously acting on various molecular targets, phytochemicals offer a multifaceted approach to inhibiting cancer progression with reduced toxicity compared to conventional therapies33.

Fluorescence microscopy for apoptosis detection in breast cancer cells

MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to gallic acid (15–20 µg/ml for 24 h) and stained with AO/EB exhibited clear signs of apoptosis at various stages. Live cells showed green fluorescence and maintained normal nuclear structure. In contrast, early apoptotic cells appeared yellow, indicating chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation. Late apoptotic cells emitted orange-red fluorescence, signifying extensive chromatin degradation and compromised membrane integrity (Fig. 6). These findings demonstrate gallic acid’s dose-dependent induction of apoptosis, characterised by progressive nuclear disintegration and membrane damage, aligning with its observed cytotoxic effects in viability assays (IC₅₀ ~15–20 µg/ml). The clear differentiation of apoptotic stages underscores the compound’s potential to trigger programmed cell death in triple-negative breast cancer cells.

Gallic Acid and Control (24 h).

3.7. DAPI-based nuclear apoptosis assessment in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells treated with gallic acid versus untreated controls (24 h).

The Fig. 7 presents DAPI-stained MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells exposed to gallic acid at concentrations of 30 µg/ml and 40 µg/ml for 24 h, in comparison with untreated controls. Control cells display intense blue fluorescence, reflecting intact nuclei and normal cellular structure. In contrast, gallic acid-treated cells demonstrate a noticeable decline in cell density along with prominent nuclear fragmentation, with fluorescence progressively weakening as the concentration increases. At 40 µg/ml, marked chromatin condensation and pronounced nuclear disintegration are observed, indicative of advanced apoptotic changes. These results clearly suggest that gallic acid induces apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells in a concentration-dependent manner by promoting nuclear damage and cell death.

Phytochemicals have garnered significant attention for their therapeutic potential against breast cancer, with recent studies highlighting their ability to target multiple signaling pathways involved in cancer progression. For example, curcumin, a polyphenol derived from Curcuma longa, exerts anticancer effects by modulating pathways such as NF-κB, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and Wnt/β-catenin, leading to apoptosis induction and inhibition of tumor growth34. Quercetin, found abundantly in fruits and vegetables, has shown potential to regulate proliferation and promote apoptosis in breast cancer cells35. Sulforaphane, an organosulfur compound from cruciferous vegetables, effectively targets breast cancer stem cells, reducing their self-renewal and sensitizing them to chemotherapy. Resveratrol, present in grapes, inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis, limiting tumor blood supply and growth36. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) from green tea also demonstrates anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties through multiple molecular mechanisms. These phytochemicals exhibit lower toxicity than conventional therapies and hold promise for integration as complementary treatments.

Conclusion

The study highlights the phytochemical composition, molecular interactions, and anticancer potential of Ficus hispida ethyl acetate extract, focusing on gallic acid. LC-MS analysis identified key bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and coumarins, which exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties. Molecular docking studies revealed moderate to strong binding affinities of gallic acid with target proteins (e.g.,2VCJ), supported by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the stability of protein-ligand complexes, with favorable binding free energy values from MM-GBSA calculations. In vitro experiments demonstrated gallic acid’s potent cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, with an IC₅₀ of 15–20 µg/ml. Microscopic analysis confirmed apoptosis induction through nuclear fragmentation and membrane damage. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of gallic acid as a candidate for triple-negative breast cancer treatment. Further in vivo, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics will help to optimize its efficacy and explore clinical applications.

Data availability

Data generated while conducting the research are available to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LC-MS/MS:

-

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry

- MDA:

-

M.D. Anderson Cancer Centre

- MB:

-

Metastatic Breast

- MD:

-

Molecular Dynamics

- MM-GBSA:

-

Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area

- NVT:

-

Constant Number of Particles, Volume, and Temperature Ensemble

- NPT:

-

Constant Number of Particles, Pressure, and Temperature Ensemble

- OPLS:

-

Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations

- SPC:

-

Simple Point Charge

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-Buffered Saline

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- FBS:

-

Fetal Bovine Serum

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- AO/EB:

-

Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole

- RMSD:

-

Root Mean Square Deviation

- RMSF:

-

Root Mean Square Fluctuation

- Rg:

-

Radius of Gyration

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

DeSantis, C. E. et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69 (6), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21583 (2019).

Holohan, C., Van Schaeybroeck, S., Longley, D. B. & Johnston, P. G. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 13 (10), 714–726. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3599 (2013).

Cheng, J. X. et al. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of ficus hispida L.f.: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 248, 112204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2019.112204 (2020).

Ali, M. & Chaudhary, N. Ficus hispida Linn.: A review of its pharmacognostic and ethnomedicinal properties. Pharmacogn Rev. 5 (9), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-7847.79104 (2011).

Ghosh, R., Sharatchandra, K. H., Rita, S. & Thokchom, I. S. Hypoglycemic activity of Ficus hispida (bark) in normal and diabetic albino rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 36 (4), 222–225 (2004). PMID: 15389376.

You, B. R. & Park, W. H. Gallic acid-induced lung cancer cell death is related to glutathione depletion as well as reactive oxygen species increase. Toxicol. Vitro. 24 (5), 1356–1362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2010.04.009 (2010).

Lin, S. et al. Gallic acid suppresses the progression of triple-negative breast cancer HCC1806 cells via modulating PI3K/AKT/EGFR and MAPK signaling pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1049117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1049117 (2022). Published 2022 Nov 29.

Liu, C. C. et al. Lauryl gallate induces apoptotic cell death through Caspase-dependent pathway in U87 human glioblastoma cells In vitro. Vivo 32 (5), 1119–1127. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.11354 (2018).

Chen, Y. J., Lee, Y. C., Huang, C. H. & Chang, L. S. Gallic acid-capped gold nanoparticles inhibit EGF-induced MMP-9 expression through suppression of p300 stabilization and NFκB/c-Jun activation in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 310, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2016.09.007 (2016).

Lee, H. L., Lin, C. S., Kao, S. H. & Chou, M. C. Gallic acid induces G1 phase arrest and apoptosis of triple-negative breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231 via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/p21/p27 axis. Anticancer Drugs. 28 (10), 1150–1156. https://doi.org/10.1097/CAD.0000000000000565 (2017).

Bottone, F. G. Jr & Alston-Mills, B. The dietary compounds Resveratrol and genistein induce activating transcription factor 3 while suppressing inhibitor of DNA binding/differentiation-1. J. Med. Food. 14 (6), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2010.0110 (2011).

Bahadar, N. et al. Epigallocatechin gallate and Curcumin inhibit Bcl-2: a pharmacophore and Docking based approach against cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 26 (1), 114 (2024).

Singh, B. N., Shankar, S. & Srivastava, R. K. Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): mechanisms, perspectives and clinical applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82 (12), 1807–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2011.07.093 (2011).

Sathiyamoorthy, J. & Sudhakar, N. In vitro cytotoxicity and apoptotic assay in HT-29 cell line using Ficus hispida linn: leaves extract. Pharmacogn Mag. 13 (Suppl 4), S756–S761. https://doi.org/10.4103/pm.pm_319_17 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Potential cancer chemopreventive and anticancer constituents from the fruits of ficus hispida L.f. (Moraceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 214, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.11.016 (2018).

Begum, Y. et al. Antibacterial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of Ficus hispida leaves and fruits. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 3 (8), 841–845 (2016).

Azwanida, N. N. A review on the extraction methods use in medicinal plants, principle, strength and limitation. Med. Aromat. Plants. 4 (3), 196. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0412.1000196 (2015).

Arsianti, A., Nur Azizah, N. & Erlina, L. Molecular docking, ADMET profiling of Gallic acid and its derivatives (N-alkyl gallamide) as apoptosis agent of breast cancer MCF-7 cells. F1000Res 11, 1453. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.127347.2 (2024). Published 2024 Feb 8.

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated Docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30 (16), 2785–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21256 (2009).

Morris, G. M. et al. Automated Docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19 (14), 1639–1662. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14%3C1639::AID-JCC10%3E3.0.CO;2-B (1998).

Ghosh, A. et al. Nonlinear molecular dynamics of Quercetin in Gynocardia odorata and Diospyros Malabarica fruits: its mechanistic role in hepatoprotection. PLoS One. 17 (3), e0263917. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263917 (2022).

Rathee, S., Rajan, M. V., Sharma, S. & Hariprasad, G. Structural modeling of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-γ with novel derivatives of stilbenoids. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 40, 101861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2024.101861 (2024). Published 2024 Nov 18.

Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103 (19), 8577–8593. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.470117 (1995).

Hospital, A., Goñi, J. R., Orozco, M. & Gelpí, J. L. Molecular dynamics simulations: advances and applications. Adv. Appl. Bioinform Chem. 8, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.2147/AABC.S70333 (2015). Published 2015 Nov 19.

Genheden, S. & Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 10 (5), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936 (2015).

Lyne, P. D., Lamb, M. L. & Saeh, J. C. Accurate prediction of the relative potencies of members of a series of kinase inhibitors using molecular Docking and MM-GBSA scoring. J. Med. Chem. 49 (16), 4805–4808. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm060522a (2006).

Potvin, O., Hudon, C., Dion, M., Grenier, S. & Préville, M. Anxiety disorders, depressive episodes and cognitive impairment no dementia in community-dwelling older men and women. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 26 (10), 1080–1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2647 (2011).

Moghtaderi, H., Sepehri, H., Delphi, L. & Attari, F. Gallic acid and Curcumin induce cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231. Bioimpacts 8 (3), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.15171/bi.2018.21 (2018).

Jabbari, N., Feghhi, M., Esnaashari, O., Soraya, H. & Rezaie, J. Inhibitory effects of Gallic acid on the activity of Exosomal secretory pathway in breast cancer cell lines: A possible anticancer impact. Bioimpacts 12 (6), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.34172/bi.2022.23489 (2022).

Aljari, S. M. et al. Acute and subacute toxicity studies of a new herbal formula induced apoptosis in the highly metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 33 (10), 101515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101515 (2021).

Asghariazar, V. et al. MicroRNA-143 act as a tumor suppressor MicroRNA in human lung cancer cells by inhibiting cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49 (8), 7637–7647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-07580-1 (2022).

El Mihyaoui, A. et al. Phytochemical compounds and anticancer activity of Cladanthus Mixtus extracts from Northern Morocco. Cancers (Basel). 15 (1), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010152 (2022). Published 2022 Dec 27.

Singh, D. & Shukla, G. The multifaceted anticancer potential of luteolin: involvement of NF-κB, AMPK/mTOR, PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. Inflammopharmacology 33 (2), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-024-01596-8 (2025).

Li, S. F., Hu, T. G. & Wu, H. Fabrication of colon-targeted Ethyl cellulose/gelatin hybrid nanofibers: regulation of Quercetin release and its anticancer activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253 (Pt 6), 127175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127175 (2023).

Chao, W. W., Liou, Y. J., Ma, H. T., Chen, Y. H. & Chou, S. T. Phytochemical composition and bioactive effects of Ethyl acetate fraction extract (EAFE) of glechoma Hederacea L. J. Food Biochem. 45 (7), e13815. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13815 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Institutional Fund Projects under grant no. (IFPIP:1695-249-1443). The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical and financial support provided by the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University, DSR, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Vaddeswaram, Andhra Pradesh, India, for providing the necessary facilities, infrastructure, and academic support to carry out this research work.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institutional Fund Projects under grant no. (IFPIP:1695-249-1443). The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical and financial support provided by the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University, DSR, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jatla Murali Prakash: Experimental work, analysis, and Manuscript writing.Shaimaa M. Badr-Eldin: Funding resource and proofreading.Hibah Mubarak Aldawsari: Funding resource and proofreading. Sabna Kotta: Funding resource and proofreading. Deepti Kolli: Work designing, Supervising, Manuscript writing and submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The present research work, “Characterization of Ficus hispida Fruit Extract and Assessment of Gallic Acid Using In Silico and In Vitro Studies Against Breast Cancer, " did not involve any in vivo experimental procedures involving animals or humans. Therefore, this study did not require ethical approval from an Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) or Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IHEC).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prakash, J.M., Badr-Eldin, S.M., Aldawsari, H.M. et al. Characterization of ficus hispida fruit extract and assessment of Gallic acid using in Silico and in vitro studies against breast cancer. Sci Rep 16, 2407 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32363-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32363-6