Abstract

Environmental changes including urbanization significantly influence the spatial distribution and the ecology of mosquito vectors, such as Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti, which are responsible of the transmitting of dengue, chikungunya, and Zika arboviruses. While studies often focus on breeding site typology, the physicochemical characteristics of these habitats remain underexplored, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. This study investigates (i) the larval ecology of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti in Franceville, an equatorial forest region undergoing urbanization, south-eastern Gabon, and (ii) emphasizing habitat typology and the physicochemical attributes influencing their proliferation. Field larval surveys were conducted across central, intermediate, and peripheral settings of the town, documenting the diversity of larval habitats and their physical features (nature, substrate material and size) and the mosquito species recovered. Water samples were analysed to determine physicochemical properties including pH, salinity, conductivity, and the presence of organic matter. The results reveal significant physicochemical heterogeneity across settings, with central urban areas more characterised by plastic (12.9%) and rubber (10.7%) breeding sites while peripheral areas were dominated by cement microhabitats (15.7%). Notably, the findings have clarified the ecological niche of these two species (Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti), revealing a preference for anthropogenic water bodies composed of rubber, plastic, or cement materials, with small to medium surface areas (< 1,250 cm2) and low to medium salinity levels (< 0.4 ppt). These findings underscore the importance of integrating physicochemical analyses into vector ecology studies to enhance our understanding of vector proliferation in rapidly urbanizing regions. By addressing this knowledge gap, the study provides critical insights to inform public health strategies and urban planning, offering a foundation for targeted vector control interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global burden of vector-borne diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika necessitates a deeper understanding of the ecology of the vectors, Aedes mosquitoes, particularly in tropical regions where these arboviruses pose significant public health threats. In sub-Saharan Africa, numerous studies have examined the typology of Aedes larval habitats, and breeding sites such as tires, plastic containers, and other anthropogenic waste are well-documented as prime habitats for Ae. albopictus, a prolific invasive vector, and Aedes aegypti, a native species that sustains epidemic cycles1,2. However, these efforts often remain limited to identifying habitat types with limited emphasis on the complex physicochemical conditions within these sites, which directly influence larval development and survival. Yet, understanding the interplay between larval ecology and the physicochemical features of breeding sites holds the potential to transform vector control strategies effectively. For instance, research from São Paulo, Brazil, demonstrated that variables such as water pH and salinity significantly shape the community composition of immature mosquitoes, underscoring the role of physicochemical factors in vector ecology3. Likewise, insights from Sri Lanka, for instance, reveal that Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti exhibit distinct habitat preferences based on water salinity and substrate composition, demonstrating the ecological complexity of larval habitats4. Thus, investigating how these mosquitoes exploit diverse breeding sites under varying physicochemical conditions could uncover key ecological determinants driving their proliferation, especially in the tropical African context, where data yet remain scarce.

The anthropogenic influence on mosquito ecology, especially in rapidly urbanizing cities of sub-Saharan Africa, adds another layer of complexity. These cities often feature a mosaic of wild vegetation and expanding urban landscapes, coupled with poorly regulated water adduction and effective waste management systems. This is particularly evident in Gabon, where natural green cover dominates, but inefficient water supply and waste management systems create abundant artificial breeding sites2. Such environmental conditions exacerbate the proliferation of Aedes mosquitoes, increasing the risk of arboviral transmission5.

In this context, studies that integrate urbanization dynamics with larval ecology, particularly through detailed physicochemical analyses of breeding sites, are essential. This is why, in this study, we address this gap by investigating the larval ecology of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti in Franceville, south-eastern Gabon. More specifically, we seek to identify typological and physicochemical factors that significantly influence the distribution of Aedes vector across the urbanization gradient of the city of Franceville, southeastern Gabon, to better inform control strategies.

Methods

Clinical trial number: not applicable

Study area

The study was conducted in the city of Franceville (1°37′15″S, 13°34′58″E), located in the Haut-Ogooué province in the southeast of Gabon (Fig. 1). Franceville has a transitional equatorial climate, with annual rainfall between 1,700 and 2,200 mm, distributed unevenly throughout the year. The yearly average temperature is approximately 24.6 °C, with the warmest period between March and May (25.1–25.4 °C)6. Franceville is Gabon’s second most populous city and comprises neighbourhoods with varying levels of urbanization. These include densely urbanized central neighbourhoods, moderately urbanized intermediate areas, and sparsely urbanized peripheral neighbourhoods located on the city’s periphery.

Location of Franceville and Libreville the capital. The map was generated using the Quantum GIS software version 3.42.1, freely available online at https://qgis.org.

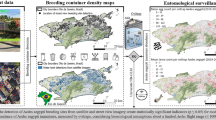

Sampling procedure

Mosquito sampling was conducted during the short rainy season, from March to June 2023, during larval surveys in various domestic and peri-domestic habitats such as flowerpots, concrete blocks, tires, and empty cans. A minimum of 50 larval habitats were surveyed in each type of neighbourhood. Physicochemical parameters of larval microhabitats, including salinity (in part per thousand [ppt]), pH, dissolved oxygen (in percentage), conductivity (µS.cm⁻1), height from the ground level, surface and volume, were measured using a multi-parameter device (WTW multiline® IDS). Immature stages (G1 generation) were collected and stored in 500 mL plastic containers before being transported to the insectary for rearing to the adult stage. The rearing conditions were 25–27 °C and 12 h:12 h photoperiod. Upon emergence, adults were individually placed in dry hemolysis tubes sealed with cotton and identified morphologically using a binocular microscope and updated taxonomic keys of Edwards7 and Huang8. Identified mosquitoes were grouped by species, with Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus being fed on rabbit blood to produce the G2 generation, which was used for salinity tolerance tests.

To enhance our understanding and conduct a comparative assessment of salinity tolerance between the two species, additional mosquito egg samples were collected in Libreville (0°23′24.36″N, 9°27′15.84″E) (Fig. 1), Gabon’s coastal capital city. The collection was carried out using ovitraps deployed for five consecutive days during the same period in Nzeng-Ayong, a densely urbanized neighbourhood of the city. The eggs were then transported to Franceville, and were hatched and reared until the adult stage under the insectary conditions. Upon emergence, the adults were identified according to the same methodology. Aedes albopictus adult mosquitoes from Libreville [the only species we recovered over there] were subsequently fed with the same method to generate the G2 generation, which was also subjected to salinity tolerance testing.

Data analysis

Field data were meticulously recorded, cleaned, and formatted using Microsoft Excel (version 2016). Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.1.3). To examine larval typology, we measured occurrence and abundance of species according to the nature of microhabitat substrates and the types of neighbourhoods in Franceville [either central, intermediate, or peripheral]. The Chi-squared test of independence was employed to assess the proportions of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti according to substrate type and neighbourhood. The distribution and variability of larval habitats were analysed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), taking into account the physicochemical parameters of the breeding sites. The PCA allowed us to study microhabitat segregation based on environmental parameters such as microhabitat type, neighbourhood classification, and the type of substrate. A generalized linear model (GLM) was used to evaluate the relationship between the abundance of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti and the physicochemical parameters. Graphical analysis of abundance data was performed using histograms, complemented by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test to determine the type of distribution. Parameters influencing the abundance of the two species were retained at a significance threshold of p = 0.05.

Results

Larval habitat distribution and characteristics

Microhabitat distribution across neighbourhoods

A total of 178 water containers were analysed, including a large majority of 170 (95.5%) positive and only 8 (4.5%) negative. Of the 178 containers, 61 (34.3%), 63 (35.4%) and 54 (30.3%) were found in central, intermediate and peripheral neighbourhoods respectively (Table 1). Regarding the nature of microhabitat, cement containers (32%) represented the majority of microhabitats, followed by plastic (29.7%) and rubber containers (24.2%) (Table 1). Regarding the distribution of microhabitats across neighbourhoods, we found that cement containers were more frequent in peripheral neighbourhoods (n = 28, 15.7%), whereas rubber and plastic containers were more prevalent in central neighbourhoods (Table 1).

Mircohabitats and physicochemical properties

The PCA revealed that the measured variables allowed to explain 51.9% of the total variability of larval microhabitats with the first two components (Fig. 2a). Of these variables, water volume (> 20% of contribution), followed by conductivity, salinity and microhabitat surface (all > 15% of contribution each) contributed the most to this variance. The variables with the less contribution (< 10% each) were height from the ground level and pH (Fig. 2b).

Larval microhabitat variability across neighbourhoods and their substrate nature. PCA explained variance is expressed according to dimension (a) and physicochemical variables (b). Red dotted horizontal line in (b) indicates the mean contribution of parameters. Bidimensional segregation of larval microhabitats and the associated correlations are illustrated according to neighbourhood types (c and d) and microhabitat nature (e and f).

In general, the PCA results revealed a structured pattern in the distribution of larval microhabitats regarding the type of neighbourhoods and the nature of the substrate. Indeed, we observed that larval microhabitats from central neighbourhoods form a unique cluster different from those in the periphery of the city. However, those from the intermediate neighbourhoods seem more homogenously distributed on the bi-dimensional frame without distinct physicochemical segregation from central and peripheral neighbourhoods (Figs. 2c). In addition, there was a notable effect of microhabitat surface and conductivity in their segregation across the types of neighbourhood (Fig. 2d). Regarding the nature of the substrate, rubber and plastic microhabitats formed a homogenous unique cluster which in return was different from the cement cluster, which also appeared distinct from the metal cluster (Figs. 2e). Similarly, conductivity and surface appeared significantly associated with microhabitat’s variability, especially those of organic (highly correlated with conductivity), metal and rubber substrates (highly correlated with surface) (Fig. 2f).

Species distribution across neighbourhoods and microhabitat properties

Species relative abundance

The larval survey resulted in 6,113 mosquitoes collected, distributed in 7 species outnumbered by Ae. albopictus (n = 4,547, 74.4%), followed by Ae. aegypti (n = 952, 15.6%) and Culex quinquefasciatus (n = 571, 9.3%). The less represented species included Anopheles gambiae s.l. (n = 26, 0.4%), Ae. dendrophilus (n = 12, 0.2%), Ae. africanus (n = 4, 0.08%) and Cx. cinereus (n = 1, 0.02%) (Fig. 3). Due to the very small numbers of these last species, we focused mainly on the most abundant species (i.e. Aedes albopictus, Ae. aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus).

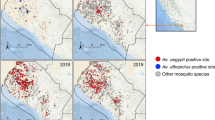

Spatial distribution of larval habitats and species across neighbourhood types in Franceville. Map created using TerraIncognita software (v2.45, https://terra-incognita.en.lo4d.com/windows). Base satellite imagery is a Copernicus Sentinel-2 image (acquired on 2020–07–24), freely accessed and downloaded from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu). This date was selected for its optimal cloud-free conditions over the study area.

Distribution across neighbourhoods

Analyses revealed that both Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti were present in all types of neighbourhood, with notable similar proportions across the three categories for Ae. albopictus (central = 38.2%, intermediate = 28.2%, peripheral = 33.6%). However, Ae. aegypti was mostly found in intermediate and peripheral settings (central = 13.3%, intermediate = 31.5%, peripheral = 55.2%) (Fig. 4a), as confirmed by the significant increasing variation of the mean abundance per microhabitat from central towards peripheral settings (Fig. 4b). Regarding the other species, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx. cinereus, and Ae. africanus were exclusively recovered in intermediate settings, whereas Ae. dendrophilus (central = 0%, intermediate = 16.7%, peripheral = 83.3%) and An. gambiae s.l. (central = 3.8.%, intermediate = 23.1%, peripheral = 73.1%) were found predominantly in peripheral neighbourhoods and to a lesser extent, in intermediate ones (Fig. 4a).

Distribution and physicochemical properties

Regarding species distribution across microhabitat substrates, we observed that Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti shared a similar and diversified pattern of exploited microhabitats, including preferentially rubber and cement, but also plastic to a lesser extent (Figs. 4c and 4 d). However, Cx. quinquefasciatus was exclusively found in plastic substrates (Fig. 4c).

The analyses also revealed that amongst the measured physicochemical parameters, the surface and the conductivity of larval microhabitats were the best predictors of the species distribution, especially for Cx. quinquefasciatus (Fig. 4e). This was also remarked for Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus but to a lesser extent. However they seemed more recovered in microhabitats of smaller surfaces (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, although there was no statistically significant relationship with conductivity, we noticed a trend of highest abundance of both species in the medium conductivity range (Fig. 4g). This trend was confirmed with the salinity analysis, showing that the highest abundance of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus was significantly associated with a low to medium salinity range, whereas they were nearly absent in microhabitats with high salinity concentrations (Fig. 4h).

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the larval ecology of the species Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti in Franceville, southeastern Gabon, with a special focus on microhabitat typology and their physicochemical characteristics. The PCA analysis revealed a homogeneous distribution of microhabitats in intermediate settings, with no distinct segregation from those of other neighbourhoods. This finding indicates greater physicochemical heterogeneity within the microhabitats of this setting. Conversely, the observed segregation trend between microhabitats in central and peripheral settings suggests a more structured distribution of larval habitats in these areas, shaped by their physicochemical characteristics. This differentiation may reflect distinct influences on microhabitat conditions, including intrinsic factors such as substrate composition (e.g. plastic, rubber, cement, metal, organic, etc.) and extrinsic factors such as environmental dynamics (e.g., exposure to meteorological elements) or human activities (e.g., accumulation of discarded and polluted artificial breeding sites from domestic waste as we described it in a previous study2).

Regarding species distribution, several studies have been conducted on the typology of Aedes larval habitats. However, very few have explored the variability of habitat typologies in relation to substrate characteristics using PCA alongside a consistent design framework (central, intermediate, and peripheral zones). However, our results align with findings from a significant body of work on Aedes habitat typologies. For instance, Djiappi-Tchamen et al. (2021) conducted a larval survey in Cameroon, Central Africa, across urban, peri-urban, and rural settings, identifying tires (rubber materials) and plastic containers as the primary breeding sites for Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti, respectively, in contrast to other container types such as metal or cement. Similarly, Herath et al. (2024) observed comparable patterns in urban areas of Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, with an inverted association: larval densities of Aedes albopictus were linked to plastic containers, while Aedes aegypti predominantly utilized rubber-based containers. Apart from rubber and plastic as the primary breeding of these species, we have also noticed an important use of cement sites (i.e., cinder blocks), which cannot be neglected as a larval source. Therefore, based on these results, one can say that the preference of these two species for rubber, plastic and cement water bodies as breeding sites in Franceville may be related to the increase in construction sites from central to peripheral zones, leading to the outdoor storage of cinder blocks that collect rainwater. This could also be linked to the rise in domestic waste production, coupled with the lack of awareness among populations regarding sanitation measures to reduce the proliferation of mosquito larval habitats2,9. Therefore, within the context of Franceville, an urbanization plan built around a waste collection system and campaigns aimed at raising awareness among communities about the elimination of potential artificial breeding sites could significantly reduce the abundance of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti species.

Field investigations revealed that the species Ae. albopictus was significantly more abundant than Ae. aegypti in central, intermediate and peripheral neighbourhoods. These results align with past observations in Gabon, where Ae. albopictus was found to be overwhelmingly predominant among native Aedes species, particularly in urban areas and their outskirts10, confirming the hypothesis of an ongoing or already completed replacement of native Aedes species (such as Ae. aegypti) by the invasive species Ae. albopictus in favourable environments in Gabon and Central Africa2,11. The abundance and widespread distribution of Ae. albopictus can be attributed to the ecological plasticity of this species. Indeed, female Ae. albopictus seeking hosts have the ability to feed on blood from various hosts, including humans, depending on their availability in the environment12. Moreover, they can lay their eggs in both natural and artificial habitats, in contrast to highly anthropophilic female Ae. Aegypti2. Similarly, during the larval stages, some studies have shown a negative association between the abundance of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus, due to the competitive advantage of Ae. albopictus larvae in accessing nutrients when cohabiting with Ae. aegypti larvae13,14.

Regarding the distribution of species according to physicochemical parameters, the PCA revealed that salinity was the best predictor of Ae. albopictus abundance, while salinity and the open surface of larval microhabitats were the best for Ae. aegypti abundance. Indeed, both species were mostly found in site of low (or small) to medium salinity and surface. These results are consistent with those observed by Multini et al. in 2021 in Brazil, South America15, showing that Ae. albopictus preferentially exploits low salinity environments. Conversely, some other studies have reported results different from ours. For instance, Ouédraogo et al. in 2022 observed that the abundance of Ae. aegypti was rather mostly associated with pH in Burkina Faso, West Africa16. Similarly, Medeiros-Sousa et al. in 2020 reported that the presence of Ae. albopictus in various natural and artificial habitats was largely dependent on pH in urban parks in São Paulo, Brazil3. However, Ruairuen et al. in 2022 noticed that the density of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti was positively correlated with the width of larval habitats in Thailand, Southeast Asia17. This result heterogeneity might suggest that the abiotic factors influencing the presence and abundance of Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti larvae in a given habitat can vary based on the environment and the capacity of these species to adapt. In this respect, the fitness of Ae. albopictus is a significant asset for this species, allowing it to thrive in different environmental contexts. It would be of value to conduct more studies aimed at characterizing life history traits that could explain the adaptative plasticity and the invasive success of Ae. albopictus compared to Ae. aegypti, especially in Central Africa where trends of overdominance of Ae. albopictus is now commonly observed and admitted. In addition, although we measured key physicochemical characteristics such as salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, surface, and volume of larval microhabitats, other potentially influential factors (such as turbidity, sunlight exposure, and vegetation cover) were not assessed in this study. Inclusion of these variables in future work would add a layer of comprehensive understanding of the ecological determinants of mosquito species distribution. Another possible limitation of the present study is the lack of comprehensive environmental datasets, such as long-term rainfall, temperature trends, and detailed land-use information, for all sampling sites. Incorporating these variables in future research could enhance the precision of ecological analyses and improve more deep analyses such as predictive modelling of vector distribution and microhabitat use.

The findings presented in this study are unprecedented within the context of Gabon and Central Africa. Previously, we established a strong correlation between the proliferation of Aedes albopictus and the abundance of artificial microhabitats composed of plastic and rubber materials in domestic waste deposits, highlighting the heightened risk of vector-borne diseases faced by nearby populations2. However, this study is the first to specifically examine how Aedes species utilize larval habitats based on their physicochemical properties. Moreover, it stands among the few investigations into these aspects of Aedes larval ecology in Central Africa, particularly in light of the regional invasion of Aedes albopictus5.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study primarily aimed to explore the larval ecology of the species Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti in Franceville, southeastern Gabon, with a special focus on microhabitat typology and physicochemical characteristics. It provides new insights into the larval ecology of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti in Franceville, southeastern Gabon, by analysing the typology and physicochemical characteristics of their breeding habitats. The findings revealed a clear preference of both species for artificial containers made of rubber, plastic, and cement, particularly those with low to medium salinity and small to medium surface area, conditions commonly found in peri-domestic environments. These preferences are likely influenced by the proliferation of construction sites and the accumulation of domestic waste, especially in peripheral and intermediate urban zones.

A significant outcome of this work is the confirmation of Ae. albopictus dominance over Ae. aegypti in all urban settings studied, supporting the hypothesis of an ecological replacement in progress, driven by the higher ecological plasticity and competitive advantage of Ae. albopictus. Moreover, while salinity and surface area emerged as key predictors of larval abundance, our study also highlights the context-dependent nature of these abiotic influences, underscoring the need for localized studies in diverse ecological settings.

From a public health perspective, the high abundance and adaptability of Ae. albopictus, a competent vector of arboviruses such as chikungunya, dengue, and Zika, raises serious concerns for vector-borne disease emergence in Franceville and similar urban settings. This study is significant as it helps to better understand the characteristics of arboviruses vectors present in Gabon in general and in Franceville in particular, and the results underscore the urgent need for integrated vector surveillance and control strategies by Gabon’s health authorities, including waste management, better urban planning, and public education campaigns mostly targeting artificial breeding site reduction.

Finally, this study sets the stage for further research into the eco-epidemiology associated with Aedes species in Central Africa, particularly through broader, transnational investigations that integrate larval ecology, adult behaviour, genetic profiling, vector-virus interactions including vector competence and virus transmission dynamics. Such efforts will be essential to inform regional public health strategies and policies and to anticipate future arboviral threats in a rapidly changing urban landscape.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- GLM:

-

Generalized linear model

References

Djiappi-Tchamen, B. et al. Aedes mosquito distribution along a transect from rural to urban settings in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Insects 12(9), 819 (2021).

Obame-Nkoghe, J. et al. Urban green spaces and vector-borne disease risk in Africa: The case of an unclean forested park in libreville (Gabon, Central Africa). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(10), 5774 (2023).

Medeiros-Sousa, A. R. et al. Influence of water’s physical and chemical parameters on mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) assemblages in larval habitats in urban parks of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Acta Trop. 205, 105394 (2020).

Herath, J. M. K., De Silva, W. P. P., Weeraratne, T. C. & Karunaratne, S. P. Breeding habitat preference of the dengue vector mosquitoes aedes aegypti and aedes albopictus from urban, semiurban, and rural areas in Kurunegala District, Sri Lanka. J. Trop. Med. 2024(1), 4123543 (2024).

Ngoagouni, C., Kamgang, B., Nakouné, E., Paupy, C. & Kazanji, M. Invasion of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) into central Africa: What consequences for emerging diseases?. Parasit. Vectors. 8, 1–7 (2015).

Ovono, P. O., Gatarasi, T., Minko, D. O., Koumagoye, D. M. & Kevers, C. Etude de la dynamique des populations d’insectes sur la culture du riz NERICA dans les conditions du Masuku, Sud-Est du Gabon (Franceville). Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 8(1), 218–236 (2014).

Cockerell, T. D. A. The African mosquitoes: Mosquitoes of the Ethiopian Region III. Culicine adults and pupae. By F. W. Edwards. British Museum, 1941. 499 pp.. Science 96(2502), 537–538 (1942).

Huang, Y. M. The subgenus Stegomyia of Aedes in the Afrotropical Region with keys to the species (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa 700(1), 1–120 (2004).

Stewart Ibarra, A. M. et al. A social-ecological analysis of community perceptions of dengue fever and Aedes aegypti in Machala, Ecuador. BMC Public Health 4(14), 1135 (2014).

Pagès, F. et al. Aedes albopictus mosquito: The main vector of the 2007 Chikungunya outbreak in Gabon. PLoS ONE 4(3), e4691 (2009).

Paupy, C. et al. Comparative role of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti in the emergence of Dengue and Chikungunya in central Africa. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. Larchmt. N. 10(3), 259–266 (2010).

Delatte, H. et al. Blood-Feeding Behavior of Aedes albopictus, a Vector of Chikungunya on La Réunion. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 10(3), 249–258 (2010).

Deerman, H. & Yee, D. A. Competitive interactions with Aedes albopictus alter the nutrient content of Aedes aegypti. Med. Vet. Entomol. 37(4), 715–722 (2023).

Yang, B. et al. Modelling distributions of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus using climate, host density and interspecies competition. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 15(3), e0009063 (2021).

Multini, L. C. et al. The influence of the pH and salinity of water in breeding sites on the occurrence and community composition of immature mosquitoes in the green belt of the City of São Paulo, Brazil. Insects 12(9), 797 (2021).

Ouédraogo, W. M. et al. Impact of physicochemical parameters of Aedes aegypti breeding habitats on mosquito productivity and the size of emerged adult mosquitoes in Ouagadougou City, Burkina Faso. Parasit. Vectors. 15(1), 478 (2022).

Ruairuen, W., Amnakmanee, K., Primprao, O. & Boonrod, T. Effect of ecological factors and breeding habitat types on Culicine larvae occurrence and abundance in residential areas Southern Thailand. Acta Trop. 234, 106630 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the institutions that helped us carry out this study, in particular the Interdisciplinary Centre for Medical Research of Franceville (CIRMF) and the Masuku University of Science and Technology (USTM), for the technical support they provided. We would particularly like to thank the Biology Department of the Faculty of Science of the USTM, and the staff of the Health Ecology Research Unit of the CIRMF and the Zoology and Entomology Department of the UFS, who welcomed us.

Funding

This study has been conducted with the financial support of the European Union (Grant no. ARISE-PP-FA-072 to JON), through the African Research Initiative for Scientific Excellence (ARISE), pilot program. ARISE is implemented by the African Academy of Sciences with support from the European Commission and the African Union Commission. This study also benefited from the internal support of the University of the Free State, South Africa (to PVO), for English editing services in addition to the salary support provided to the corresponding author by the University of Science and Technology of Masuku and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Medical Research, Gabon. We benefited from the support GDRI-GRAVIR network (led by CP) in conceptualizing the study. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union, the African Academy of Sciences, the African Union Commission, or the institutions to which the authors are affiliated. The funders played no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, the decision to publish or the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: JO-N, PK, CP; Data curation: NYK, AOO, JO-N, FMK, BGN, MFN, LCNN, PY, NMLP; Formal analysis: JO-N, AOO, YON, NYK, FMK, REO; Data visualization: FMK, LEM, PVO, REO, JO-N; First article drafting: JO-N, FMK, AOO; Reviewing and editing: PK, PVO, LEM, YON, Acquisition of funding: JO-N, PVO.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Obame-Nkoghe, J., Moudoumi Kondji, F., Niangui, B.G. et al. Physicochemical and typological insights into Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti larval habitats in a sub-Saharan African urban gradient setting. Sci Rep 16, 2545 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32398-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32398-9