Abstract

Service discovery in the Social Internet of Things (SIoT) must be both efficient and trustworthy. Dense device graphs and heterogeneous link reliability make naïve traversal ineffective and risk-prone. We address this by constructing an Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT) search space via a trust threshold \(\alpha\) and proposing a class- and trust-based informed search algorithm that combines deterministic neighbor ranking, class-aware (friendship) selection, Top-K exploration, a hop bound H, and a selective fallback mechanism. This dual control (\(\alpha\) and K) is designed to balance reliability and exploration while bounding search depth. We posit and evaluate four hypotheses: (H1) setting \(\alpha \ge 0.5\) improves discovery relative to permissive thresholds; (H2) \(\alpha\)-filtering with Top-K reduces exploration cost (visited nodes) while preserving short paths and low latency; (H3) increasing K and H boosts success with only moderate latency overhead; and (H4) fallback restores progress under strict trust filtering with limited cost. Experiments on five real-world graphs perform an SIoT-style \(\alpha\)-profiling of success, hops, latency, visited nodes, and LCC ratio. The results show that discovery improves from permissive to moderate \(\alpha\) and stabilizes near \(\alpha \ge 0.5\); visited nodes decrease as \(\alpha\) rises, while hops remain modest and latency low; larger K and H increase success with moderate latency increases; and fallback recovers discovery when strict \(\alpha\) yields few eligible neighbors. Runtime measurements indicate that the proposed method is competitive—often fastest on larger graphs—relative to standard graph searches. Overall, the findings validate the hypotheses and demonstrate that a trust- and class-aware, dual-controlled discovery algorithm provides effective, efficient, and robust service discovery in SIoT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is rapidly gaining traction across numerous domains, profoundly influencing daily life. This evolving paradigm enables the creation of vast numbers of new connections each day, generating data volumes that can easily reach petabyte scales. Current centralized search engines, typically operating as large server clusters, face mounting challenges in managing this exponential data growth. Conventional information search and retrieval solutions are often only partially centralized; yet even these approaches remain vulnerable to single points of failure, high computational overhead, susceptibility to attacks, and limited scalability and flexibility. These limitations have led researchers to advocate for entirely distributed search engines.

In recent years, modern IoT research has prioritized decentralized or distributed approaches for information and resource provision. Notably, M. Nitti et al. and A. Rehman et al. introduced a friendship selection mechanism for social IoT (SIoT)1,2, where IoT devices model social relationships based on factors such as shared interests, geographical proximity, and trust levels. Devices autonomously form “friendships” with others that exhibit similar behavior or belong to the same social circle, enabling collaboration through resource and information sharing in a social network context. This concept underpins the SIoT paradigm, in which devices connect autonomously and exchange services or information on behalf of their owners3,4.

A defining characteristic of SIoT is its reliance on distributed search techniques, which support local, global, and dynamic connections based on service specifications. However, excessive local connections tend to produce regular lattice structures, while frequent connection changes can destabilize the network. Therefore, a structured yet flexible topology is needed to ensure scalability and navigability. For example, a typical Internet search returns millions of results, with only a small fraction being relevant, while the rest are trivial or duplicates. The difficulty of isolating accurate information from irrelevant data increases network load and search latency.

Selecting friends that provide secure, reliable information in a massive, heterogeneous SIoT network remains a challenging problem. Previous work2,5 has addressed friendship selection by computing the trustworthiness of both the service and its provider. A weighted trustworthiness ranking mechanism6 was proposed to reduce network complexity by eliminating irrelevant connections and promoting well-informed device clusters. More recent studies have introduced restrictive parameters such as service class and class rating7,8,9, where service class categorizes nodes based on purpose and class rating quantifies expertise within that class. These mechanisms improve navigation and reliability in service discovery.

Research gap Despite these advances, existing SIoT discovery methods often suffer from pure greedy traversal pitfalls—becoming trapped in local minima, lacking deterministic tie-breaking, and failing to integrate trust thresholds with service-class filtering. This gap motivates the development of a trust-based, class-aware service discovery algorithm that simultaneously reduces network complexity, ensures deterministic selection, and maintains connectivity through controlled exploration.

We propose an efficient service discovery algorithm that addresses the shortcomings of pure greedy traversal by combining trust-based filtering with class-aware neighbor selection and a selective fallback mechanism. Drawing inspiration from social network search principles, our algorithm first classifies neighbors by service class, retaining only those with trust ratings above a threshold \(\alpha\). Within each class, candidates are ranked by trust; ties are broken by higher degree and then smaller node ID to ensure determinism. A Top-K parameter limits candidates per hop, balancing trust filtering with exploration breadth. If no forward progress occurs within the hop limit H, a selective fallback admits the next-ranked, class-matched neighbors to preserve connectivity without exhaustive search. This dual trust-and-breadth control achieves bounded traversal depth, high success rates, and reduced latency across diverse trust settings.

Research contributions

-

We propose a class- and trust-based heuristic to construct the Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT), reducing network complexity by linking devices according to purpose and reliability.

-

We develop a novel service discovery algorithm that integrates trust filtering (\(\alpha\)), class-aware neighbor selection, deterministic tie-breaking, and a selective fallback mechanism to enable robust and efficient traversal.

-

We introduce a dual trust-and-breadth control mechanism (\(\alpha\) + Top-K) that balances exploration and efficiency, prevents local minima, and bounds search depth.

-

We provide a comprehensive evaluation on five real-world graphs against four baseline algorithms, offering, to our knowledge, the first systematic SIoT-style \(\alpha\)-profiling of success rate, hops, latency, visited nodes, and LCC ratio.

Hypotheses

Guided by the design and evaluation plan, we test the following hypotheses about the proposed algorithm:

-

H1 (Trust threshold effectiveness): Setting the trust threshold to \(\alpha \ge 0.5\) improves discovery performance relative to permissive thresholds (\(\alpha < 0.5\)), by prioritizing traversal over reliable, purpose-aligned links. Consistent with our design, performance stabilizes around moderate \(\alpha\) values near 0.5.

-

H2 (Dual-parameter efficiency): The combination of \(\alpha\)-based filtering and Top-K neighbor selection reduces exploration cost (visited nodes) while preserving short paths (hops) and responsiveness (latency).

-

H3 (Latency–exploration tradeoff): Increasing K and the hop bound H increases the likelihood of successful discovery with only moderate additional latency.

-

H4 (Fallback robustness): The selective fallback mechanism improves discovery when strict trust filtering yields few eligible neighbors (high \(\alpha\)), with limited overhead.

These hypotheses are examined through the theoretical analysis in Sect. 3.5 and are further validated empirically in Sect. 6.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Sect. 2 reviews related work. Sect. 3 presents the proposed methodology. Sect. 4 describes the datasets and explains the proxy network rationale. Sect. 5 details the experimental setup. Sect. 6 reports and discusses the results. Sect. 7 outlines the limitations and future work. Finally, Sect. 8 concludes the paper.

Related work

The proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT) has dramatically accelerated the production of data, making the retrieval of relevant and reliable information a central challenge. Information retrieval systems (IRS) were initially designed to return results for all words in a query, but this approach often produces an overwhelming volume of responses, many of which are irrelevant or redundant. Such information overload wastes time, increases computational overhead, and adds significant traffic to the network. In many cases, useful or highly relevant results are buried among trivial or duplicate responses, making it difficult for users to identify the desired information efficiently. To address these shortcomings, the concept of a personalized IRS was proposed, enabling query processing to consider user-specific preferences. However, this approach has not been widely adopted in practice. Consequently, researchers have continued to develop more sophisticated algorithms to improve the retrieval of data, information, and services in large-scale, heterogeneous networks10,11.

Information retrieval—also referred to as information mining—has long been a fundamental problem in computer science. Retrieval methods vary depending on whether the dataset is sorted or unsorted, with sorted datasets allowing faster search steps and unsorted ones requiring more exhaustive exploration. In IoT and especially in Social IoT (SIoT) environments, information retrieval faces additional constraints: devices are often resource-limited, network connectivity can fluctuate, and data are generated in real time. Moreover, SIoT networks exhibit high clustering due to socially motivated links—devices connect through ownership, co-location, co-work, parental relationships, or shared interests1,3,4. This structure, while useful for building trust and relevance, can lead to redundant query paths and repeated low-value responses if not filtered properly. Earlier studies addressed this by introducing trust-aware friendship selection mechanisms2,5,6, which rank neighbors based on trustworthiness and reliability. More recent work proposed the concepts of service class and class rating7,8,9, where the service class categorizes nodes by purpose and the class rating measures expertise within that category. These parameters enhance navigation and reduce network complexity, and they are directly incorporated into the trust threshold \(\alpha\)–based filtering in our proposed approach.

Over the decades, numerous search algorithms have been developed for different contexts. Traditional search algorithms—including linear search, binary search, interpolation search, and jump search—have been widely studied and are still used in various domains12,13,14,15. These methods form the basis of many retrieval systems, but they generally assume either a static dataset or a predictable data structure. Advanced algorithms have been proposed by extending the core principles of traditional methods to more complex environments. Examples include tree-based search for network localization and fast string search for pattern matching16,17. Comparative studies have evaluated the efficiency of these methods across different problem spaces18, and other analyses have categorized them into informed and uninformed search types, each with advantages and trade-offs depending on the available knowledge of the search domain19,20. However, these traditional and advanced algorithms typically optimize for speed and accuracy without explicitly considering social relationships, trust ratings, or class-based filtering—elements that are essential in SIoT discovery.

Pathfinding algorithms, particularly in graph-based and networked systems, are also central to efficient information retrieval. The shortest-path problem—finding the optimal route between two nodes–has been studied extensively, with solutions such as breadth-first search, depth-first search, Dijkstra’s algorithm21, and heuristic-based methods. While Dijkstra’s algorithm remains effective for weighted graphs with non-negative edge costs, its computational overhead increases significantly as networks grow large and highly clustered. In artificial intelligence, heuristic approaches like greedy best-first search and A* best-first search22,23,24,25 have proven useful for pathfinding. Greedy best-first search chooses the next hop based solely on the most promising heuristic value (e.g., lowest estimated distance or cost), while A* combines this heuristic with the accumulated path cost to balance exploration and exploitation. These methods are effective for spatial networks or routing problems, but in SIoT they face unique challenges: traversal cost is not just distance but also includes trustworthiness, service relevance, and connectivity preservation. Moreover, pure greedy search can suffer from local minima, getting stuck when no neighbor appears better than the current node, while A* and similar algorithms rarely incorporate trust thresholds or service-class constraints into their decision-making.

Several studies22,26,27 have compared these pathfinding approaches in terms of efficiency, scalability, and accuracy. They show that performance varies widely with network topology, heuristic design, and link-cost definitions. In highly clustered small-world networks—such as those formed in SIoT—purely heuristic methods can fail to reach the target efficiently or at all if they lack mechanisms for deterministic tie-breaking or for relaxing strict selection criteria when progress stalls. In this context, deterministic neighbor ranking becomes important: without it, search may produce inconsistent results or revisit nodes unnecessarily. Furthermore, selective fallback expansion—a temporary relaxation of the trust threshold \(\alpha\)—can be critical to preserving connectivity without resorting to exhaustive search.

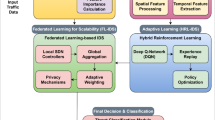

Parallel to these graph-theoretic approaches, other SIoT-specific directions such as blockchain-based service discovery, federated discovery frameworks, and context-aware architectures have been proposed. These frameworks address system-level guarantees like privacy, auditability, and decentralized coordination, but they operate at a different abstraction layer and are complementary rather than directly comparable to the topology- and trust-driven traversal algorithms studied here.

The literature therefore shows that while significant progress has been made in information retrieval, trust-based selection, and pathfinding, there is still no unified approach that integrates service-class filtering, trust-threshold admission control, deterministic tie-breaking, and selective fallback in a way that suits the large-scale, heterogeneous, and socially structured nature of SIoT networks. This gap directly motivates our proposed class-based, trust-aware Greedy+Fallback algorithm, which combines \(\alpha\)-based trust filtering, class-specific neighbor ranking, Top–K breadth control, and selective fallback to maintain connectivity and ensure high success rates. By structuring the SIoT network into an Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT) and using class-based heuristics, our method reduces complexity, avoids redundant paths, and delivers efficient and reliable service discovery in trust-filtered environments where traditional and advanced algorithms alone fall short.

Methodology

This section presents the design rationale and step-by-step procedure of our proposed class-based, trust-aware greedy service discovery algorithm with selective fallback. The methodology is developed to address the shortcomings of pure greedy traversal in SIoT—namely local minima, non-determinism, and scalability constraints—by integrating trust thresholds, class ratings, deterministic tie-breaking, and bounded breadth exploration. We first describe the SIoT network model and motivate the construction of the Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT). We then detail the discovery algorithm, supported by both conceptual illustrations and empirical validation.

SIoT model and problem definition

The Social Internet of Things (SIoT) is modeled as a graph \(G=(V, E)\) where V is the set of IoT devices and E represents social ties (friendships) between them. Friendships arise from relationships such as co-location, co-work, parental control, ownership, or shared interests1,3,4. Each edge \((u,v)\in E\) can support multiple service classes \(\zeta \in \textit{CLASSES}=\{\zeta _1,\dots ,\zeta _m\}\). A class rating \(r(u,v,\zeta )\in [0,1]\) quantifies the reliability and expertise of node v in class \(\zeta\) from the perspective of u. At the same time, a trust score is derived from historical interactions and reputation mechanisms2,6,7. A query is defined by a starting node s and a requested service class \(\zeta _q\).

Figure 1 illustrates the Social Internet of Things Network. Devices form social links based on ownership, co-location, co-work, parental, or co-interest relationships, producing highly clustered graphs. Devices are represented as nodes with labeled social ties. Each node may offer one or more services, and the discovery process must identify a trustworthy provider of the requested class \(\zeta _q\) within bounded hops.

Social Internet of Things Network. Devices form social links based on ownership, co-location, co-work, parental, or co-interest relationships, producing highly clustered graphs. Nodes represent devices with social ties (friendships). Each device may provide multiple services belonging to different classes.

Trust- and class-aware discovery framework

ISWSIoT construction via trust thresholding

To reduce network complexity and eliminate unreliable paths, we construct an Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT) for the querying device. An ISWSIoT is a pruned subgraph of G that retains only neighbors with trust ratings above a threshold \(\alpha\):

The resulting subgraph \(G_\alpha\) balances reliability with connectivity, ensuring that discovery proceeds only over trustworthy neighbors.

Figure 2a illustrates the construction of the Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT) through class-rating and trust-based filtering. Each neighbor of the source node is annotated with a class rating (CR) that quantifies its reliability and expertise in a given service class. By applying a trust threshold \(\alpha\), neighbors with insufficient ratings are excluded, while only those who meet or exceed \(\alpha\) are retained. This pruning process eliminates weak or unreliable links, thereby reducing the search space, avoiding redundant traversals in clustered regions of the SIoT, and ensuring that subsequent discovery steps operate over a subgraph composed of trustworthy and relevant connections. The resulting ISWSIoT provides a more scalable and navigable structure for service discovery while maintaining the integrity of the underlying social relationships.

LCC computation policy (connectivity and missing data) We compute largest connected component (LCC) ratios on the class-filtered trust graph \(G_{\alpha }=(V,E_{\alpha })\), where \((u,v)\in E_{\alpha }\) iff \(r(u,v,\zeta _q)\ge \alpha\). Because ratings are per-edge and directed, we report LCC under two standard assumptions: (i) undirected projection, where an undirected edge exists if either direction passes the \(\alpha\) filter; and (ii) directed-weak connectivity, which ignores edge orientation when assessing reachability but preserves the \(\alpha\) filter. Unless stated otherwise, LCC trends use directed-weak connectivity. We do not impute missing ratings (e.g., no “trust = 1.0” defaults); edges without a class-specific rating for \(\zeta _q\) are treated as absent. We also do not apply temporal or cross-class carry-forward. This policy yields a conservative, class-faithful topology for robustness assessment.

Greedy discovery with deterministic tie-breaking and top–K control

Once the ISWSIoT is constructed, service discovery proceeds via greedy traversal constrained by three principles:

-

1.

\(\alpha\)–filtered candidates: At each hop, only neighbors with ratings \(\ge \alpha\) for class \(\zeta _q\) are considered. If no such neighbors exist and fallback is disabled, traversal halts.

-

2.

Deterministic tie-breaking: To prevent non-determinism, candidates are ranked by (i) descending trust rating, (ii) descending node degree, and (iii) ascending node ID. This guarantees reproducible and consistent results.

-

3.

Top–K breadth control: Only the top K ranked candidates are expanded per hop. This prevents combinatorial explosion, controls communication overhead, and ensures scalability.

The traversal is further bounded by a maximum hop limit H, which caps exploration depth and ensures termination.

Provider density versus search width We distinguish provider density (availability of service endpoints) from search branching. Provider density governs how many nodes in a graph expose a service in class \(\zeta\), whereas the search branching cap K bounds local expansion during greedy traversal. When datasets include native provider labels, we use them as is. When synthetic labels are required, we assign providers by a fixed fraction p of nodes per class, sampled uniformly without replacement: \(\lfloor p\,|V| \rfloor\) providers for \(p \in \{0.05,\,0.10,\,0.15,\,0.20\}\). This density model scales linearly with |V| and thus removes graph-size bias. The Top–K cap controls branching but does not limit the number of providers in the graph.

Selective fallback for connectivity preservation

Pure greedy traversal may fail if all neighbors at a hop fall below \(\alpha\), even though a slightly weaker but relevant path exists. To avoid premature failure, we introduce selective fallback: if no eligible neighbors exist at hop h, \(\alpha\) is temporarily relaxed only for that hop, allowing the next-ranked neighbors in class \(\zeta _q\) to be considered. This mechanism preserves connectivity while avoiding exhaustive search. When combined with Top–K control and hop bounding, fallback ensures robustness without sacrificing scalability.

Trust and class rating model

A fundamental component of the proposed discovery algorithm is the definition of the trust and class rating function \(r(u,v,\zeta )\), which quantifies the reliability of a friend node v in providing services of class \(\zeta\) as perceived by an individual node u. This function directly governs the \(\alpha\)-filtering step in Algorithm 1 and is therefore central to ensuring that the constructed subgraph \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\) reflects trustworthy and class-relevant neighbors.

Definition Let \(u \in V\) be the querying node, \(v \in N(u)\) a candidate neighbor, and \(\zeta \in \mathscr {Z}\) a service class. We define the trust and class rating as a normalized scalar \(r(u,v,\zeta ) \in [0,1]\) computed from three components:

-

1.

Direct interaction success: empirical success rate of past interactions between u and v for services in class \(\zeta\), denoted \(\sigma (u,v,\zeta )\).

-

2.

Indirect reputation: aggregated recommendations from u’s other friends about v in class \(\zeta\), denoted \(\rho (u,v,\zeta )\).

-

3.

Contextual adjustment: a factor \(\kappa (u,v,\zeta ,t)\) that discounts ratings based on temporal recency or contextual mismatch (e.g., location, time).

The combined trust score is:

where \(\lambda _1 + \lambda _2 + \lambda _3 = 1\) are tunable weights reflecting the relative importance of local experience, social consensus, and context-awareness.

Update rule After each interaction with a provider node v in class \(\zeta\), u updates the trust rating via an exponentially smoothed rule:

where \(\eta \in (0,1]\) is the learning rate, and \(\delta \in \{0,1\}\) indicates success (1) or failure (0) of the interaction. This ensures adaptability to recent behavior without discarding long-term history.

Penalty integration To capture the reliability degradation of nodes that frequently fail to provide a service, we incorporate the error-penalty function proposed in Eq. (2):

where \(\epsilon > 0\) controls the severity of the penalty. This mechanism ensures that repeated failures reduce trust more sharply, potentially disqualifying v from the \(\alpha\)-filtered subgraph in subsequent discovery attempts.

Worked example Suppose node u has interacted with friend v for class \(\zeta = \textit{health}\) three times with outcomes: success, success, failure. Setting \(\eta =0.5\), \(\epsilon =0.1\), and initial rating \(r_0(u,v,\zeta )=0.5\), we obtain:

This illustrates how one failure after repeated successes sharply lowers the rating, reflecting reduced confidence in v for \(\zeta\).

Role in discovery The \(\alpha\)-threshold enforces that only neighbors with \(r(u,v,\zeta ) \ge \alpha\) are retained in \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\). Consequently, the trust and class rating model ensures that the proposed discovery algorithm prioritizes service providers that are both trustworthy and class-relevant, while remaining adaptive to observed outcomes. In addition, ratings are explicitly maintained per edge and per class \((u,v,\zeta )\), which guarantees that trust assessments are fine-grained and individualized to each friendship relation. Finally, when ties must be broken among candidates during greedy expansion, the degree is measured in the trusted subgraph \(G_\alpha\), ensuring that the ranking reflects the actual connectivity of the reduced, trustworthy network rather than the global graph.

Algorithm specification

Algorithm 1 specifies the complete discovery procedure.

Phase A builds the Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT) by applying \(\alpha\)–filtering to retain only trustworthy, class-relevant edges, thereby constructing a reduced and reliable subgraph around the requester.

Phase B then performs greedy discovery within this trusted subgraph, using Top–K expansion, deterministic tie-breaking, and (optionally) selective fallback at each hop. The algorithm returns the discovered service (as ServiceURL), the path P to the provider, the hop count, and the total number of visited nodes. The useFallback flag enables direct comparison between pure greedy mode and Greedy+Fallback mode. Unless stated otherwise, default parameters \(K=6\) and \(H=6\) are adopted, representing the empirically stable region identified by the sensitivity study in Sect. 6.

Conceptual and empirical validation

To illustrate both the conceptual rationale and the empirical behavior of the proposed service discovery algorithm, we provide a two-part visualization in Fig. 2. The figure connects the abstract design principles of our method to their concrete manifestation during traversal in a real SIoT network.

Figure 2a presents the conceptual class–rating structure that governs Phase A of discovery. Each neighbor of the requester is annotated with class ratings (CR), where \(CR(\zeta )\) denotes the trust score of a candidate node for service class \(\zeta\). For a query targeting class \(\zeta _q\), the requester evaluates all directly connected neighbors and filters out those whose class-specific score does not satisfy the trust threshold \(CR(\zeta _q) \ge \alpha\). Only qualifying neighbors are retained, and among them, the Top–K highest-rated are selected for expansion. Deterministic tie-breaking is applied uniformly throughout the algorithm: candidate neighbors are ranked first by trust rating (descending), then by node degree within \(G_\alpha\) (descending), and finally by node ID (ascending) as a stable tiebreaker. This three-stage rule guarantees fully reproducible traversal decisions and eliminates random oscillations in densely connected SIoT regions. If no qualifying neighbors exist at the current hop, the algorithm invokes a selective fallback policy that temporarily relaxes the trust threshold for that hop only. Specifically, the threshold is reduced to \(\alpha ' = \max (\alpha - \Delta , \alpha _{\min })\), where \(\Delta = 0.1\) represents a bounded relaxation step and \(\alpha _{\min } = 0.3\) prevents over-relaxation in low-trust environments. This controlled fallback ensures continued connectivity while preserving the trust-integrity invariant \(r(u, f, \zeta ) \ge \alpha\) for all accepted providers. In practice, fallback activation occurs only in sparse or high-\(\alpha\) regimes (typically in less than 10–15% of discovery attempts across datasets), and the mechanism restores the original \(\alpha\) value at the next hop. This two-level filtering process—trust-based pruning followed by ranking with Top–K control—constrains the branching factor, reduces redundant exploration in small-world topologies, and biases traversal toward reliable and high-quality paths. Conceptually, this process defines the Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT), a filtered subgraph that forms the foundation for efficient discovery.

Figure 2b depicts an empirical traversal trace obtained from experiments on the Caenorhabditis dataset with \(\alpha =0.6\), \(K=6\), and \(H=6\) (Phase B). The requester node is shown in red, the successful service provider in green, intermediate expanded nodes in blue, and the final selected path in orange. Grey edges represent potential network links that were pruned either because their trust scores fell below \(\alpha\) or because they did not rank among the Top–K candidates. In this example, the algorithm successfully resolves the query within four hops, visiting approximately 224 nodes in total. The trace demonstrates how trust-based filtering and Top–K breadth control exclude low-value candidates early, thereby reducing traversal overhead, while still preserving a connected path to the target. The bounded hop limit H guarantees termination, and the fallback mechanism ensures robustness in cases where no immediate qualifying neighbors exist.

Together, Fig. 2a and b establish a direct link between theory and practice: (a) the conceptual model shows how trust and class-based filtering define the ISWSIoT search space, while (b) the empirical trace validates that these rules translate into reliable, bounded, and efficient discovery in real SIoT graphs. This dual perspective demonstrates both the scientific rationale and the practical efficacy of the proposed algorithm.

Conceptual and empirical validation of the proposed class–based greedy service discovery algorithm. (a) Conceptual structure of class ratings and trust filtering: for each query class \(\zeta _q\), neighbors with class rating \(CR(\zeta _q) \ge \alpha\) are retained, and the Top–K highest-ranked among them are selected for expansion. This pruning eliminates weak or redundant links and preserves only trustworthy, high-value connections in the ISWSIoT. (b) Empirical traversal trace on the Caenorhabditis graph (\(\alpha {=}0.6\), \(K{=}6\), \(H{=}6\)). The requester is shown in red, the discovered service provider in green, intermediate expanded nodes in blue, and the final path in orange. Grey edges indicate links pruned by \(\alpha\) filtering and Top–K control. The trace demonstrates bounded greedy traversal that successfully reaches the target in 4 hops, validating the practical effect of the conceptual design in (a).

Summary of methodology

In summary, the proposed methodology integrates three key components:

-

1.

\(\alpha\)–filtered ISWSIoT construction: pruning weak or unreliable links to build a trustworthy subgraph for discovery.

-

2.

Deterministic greedy traversal with Top–K breadth control: ranking candidates by trust, degree, and node ID to ensure reproducibility while bounding exploration complexity. Implementation note: Candidate sets are always sorted by trust (descending), then degree in \(G_{\alpha }\) (descending), and finally by node ID (ascending) to enforce deterministic ranking and full reproducibility.

-

3.

Selective fallback: temporarily relaxing the trust threshold when no eligible neighbors exist at a hop, thereby preserving connectivity without resorting to exhaustive search.

Figures 1 and 2 jointly illustrate the complete process: from the baseline SIoT network to the conceptual filtering and ranking mechanism, and finally the empirical traversal trace. Algorithm 1 formalizes the procedure step by step. Together, these elements define a reproducible, scalable, and scientifically rigorous framework for service discovery in SIoT. The following section presents a theoretical evaluation of the algorithm, including the correctness, convergence, and performance guaranties.

Evaluating the proposed algorithm

To validate the proposed class–based, trust–aware greedy discovery algorithm with selective fallback (Algorithm 1), we conduct a multifaceted evaluation consisting of: (i) formal correctness verification, (ii) precise time and space complexity analysis, (iii) robustness analysis in terms of error rate and tolerance, and (iv) structured proofs of correctness and convergence. This comprehensive evaluation ensures that the proposed algorithm is not only practically implementable but also provably reliable, efficient, and theoretically well–founded.

Correctness

Correctness requires that Algorithm 1 always produces outputs consistent with its design specification. In Phase A, only services provided by neighbors whose per–edge class rating \(r(u,v,\zeta )\) exceeds the trust threshold \(\alpha\) are retained in the trusted subgraph \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\). In Phase B, the greedy search is restricted to this subgraph, so that if a valid provider exists in \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\) within the hop bound H, the algorithm must eventually locate at least one such node.

Formally, let F denote the set of friends (nodes), and \(\mathscr {Z}\) the set of service classes. The output of Algorithm 1 is a set of service–provider pairs

Each element \((f,\zeta )\) indicates that node f provides a service in class \(\zeta\). The trust constraint is enforced as

Equation 4 encodes the \(\alpha\)–filtering criterion of Phase A. It guarantees that only neighbors with trust ratings at or above the threshold are admitted into \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\) and subsequently considered during greedy traversal. Since ranking follows a globally fixed and deterministic order—trust (descending) \(\rightarrow\) degree in \(G_{\alpha }\) (descending) \(\rightarrow\) node ID (ascending)—all discovery decisions are reproducible, eliminating ambiguity across runs or platforms.

Bounded fallback and preservation of Eq. 4. To prevent dead-ends under sparse trust while preserving correctness, the traversal stage admits a single-hop bounded relaxation when a node has no \(\alpha\)-eligible neighbors. Formally, if \(\{v:\, r(u_t,v,\zeta )\ge \alpha \}=\varnothing\) at hop t, the algorithm may advance once via an edge with \(r(u_t,v,\zeta )\ge \alpha '\) where \(\alpha '<\alpha\); immediately thereafter, the original \(\alpha\)-constraint is reinstated for all subsequent expansions. This relaxation only affects intermediate traversal, not provider acceptance: returned providers must still satisfy Eq. 4, i.e., \((f,\zeta )\in S \Rightarrow r(u,f,\zeta )\ge \alpha\). Hence, the invariant

holds regardless of whether the traversal used a one-hop \(\alpha '\) transition. Because selection follows a fixed global tie-breaking order and the relaxation length is strictly bounded (at most one transition per impasse), Algorithm 1 remains both reproducible and consistent with its trust specification.

Time and space complexity

Let \(n = |F|\) be the number of friends, \(m = |\mathscr {Z}|\) the number of service classes, R the Phase A expansion radius, K the Top–K cap, and H the Phase B hop bound. The computational cost separates into two phases:

-

Phase A (ISWSIoT construction). For each \(u\in F\), the algorithm computes ratings \(r(u,v,\zeta )\) for neighbors v across all classes \(\zeta \in \mathscr {Z}\). This requires O(nm) storage and rating lookups. During ego–network expansion of radius R, each node contributes at most K new neighbors per layer, yielding at most \(O(K^R)\) retained nodes in \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\). Candidate sets are sorted per node expansion at cost \(O(d\log d)\), where d is the local degree, but this is upper bounded by K after selection.

-

Phase B (greedy discovery). The greedy search explores at most \(O(\min (K^H,|\mathscr {G}_\alpha |))\) nodes within \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\), since breadth is capped by K and depth by H. At each hop, sorting neighbors costs \(O(d\log d)\) but is again bounded by K.

Hence, the total time complexity is

which is polynomial in n, m and exponential only in the chosen exploration bounds R, H (typically small in practice). Space complexity is dominated by the rating table O(nm) plus the storage of \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\) of size \(O(K^R)\). This refined analysis more accurately reflects Algorithm 1 than the earlier O(nm) bound: initialization is O(nm), but traversal costs are governed by user–tunable parameters K, R, and H, ensuring scalability.

Error rate and tolerance

Robustness is critical in SIoT environments, where nodes may fail or behave maliciously. We define the error rate as the fraction of discovery attempts that either (i) return an incorrect provider or (ii) fail to return a valid provider when one exists. The error tolerance is the maximum acceptable error rate before the discovery system is considered unreliable.

Algorithm 1 mitigates error through adaptive trust adjustment at the per–edge level. Specifically, when a provider fails to deliver the advertised service, its rating is penalized according to the update rule introduced in Sec. 3.2. Formally, after interaction outcome \(\delta \in \{0,1\}\), the update is

where \(\eta\) is the learning rate and \(\epsilon >0\) controls penalty severity. When \(\delta =0\) (failure), the penalty term lowers the trust rating more sharply, expediting the exclusion of unreliable nodes from \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\).

This adaptive mechanism dynamically suppresses error–prone nodes, thereby lowering the empirical error rate and enhancing fault tolerance without requiring network–wide consensus. Empirically, repeated failures cause ratings to quickly fall below \(\alpha\), preventing such nodes from re–entering the candidate set.

Proof of correctness by induction

We now present a formal proof of correctness for Algorithm 1 via induction on the number of friends.

Inductive hypothesis Assume that for any set of n friends, the algorithm correctly filters and selects providers in accordance with Eq. ??.

Base case (\(n=1\)). With a single friend \(f_1\) and a single service \(\zeta _1\), the algorithm evaluates \(r(u,f_1,\zeta _1)\). If \(r \ge \alpha\), then \((f_1,\zeta _1)\) is included in \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\); otherwise, it is excluded. This decision is trivially correct.

Inductive step Consider \(F = \{f_1,\dots ,f_n,f_{n+1}\}\). By the inductive hypothesis, the algorithm correctly filters and selects among \(\{f_1,\dots ,f_n\}\). For \(f_{n+1}\), it applies the same rule \(r(u,f_{n+1},\zeta _j)\ge \alpha\) for each class \(\zeta _j\), independently of prior evaluations. Since the logic is identical and deterministic, correctness extends to \(n+1\) friends.

By induction, Algorithm 1 correctly filters and selects providers for all finite n.

Proof of convergence

Contrapositive proof

We show convergence by contradiction. Let P be the statement: “Algorithm 1 converges for any SIoT input.” Suppose \(\lnot P\) holds; i.e., the algorithm does not converge and enters an infinite loop. However, from the inductive correctness proof, each step makes a deterministic finite decision: either (i) a valid provider is discovered, or (ii) the candidate set is exhausted. Since the candidate set is finite (bounded by \(K^R\) in Phase A and \(K^H\) in Phase B) and monotonically decreases as nodes are visited or pruned, the algorithm cannot continue indefinitely. This contradiction implies that \(\lnot P\) is false, and therefore P is true: Algorithm 1 always converges.

Stepwise convergence process

Operationally, convergence proceeds as follows:

-

1.

Initialize the rating table \(R[u][v][\zeta ]\) for all friend–class pairs.

-

2.

Apply \(\alpha\)–filtering to construct the trusted subgraph \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\).

-

3.

Execute greedy traversal within \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\), expanding Top–K candidates per hop up to depth H.

-

4.

If a provider is discovered, update ratings based on observed reliability (Eq. 5) and terminate.

-

5.

If traversal exhausts all candidates without success, ratings of attempted but failed nodes are penalized, \(\alpha\)–filtering is reapplied, and the process repeats until either a provider is found or \(\mathscr {G}_\alpha\) becomes empty.

Because both F and \(\mathscr {Z}\) are finite, and because the candidate set shrinks monotonically after each iteration due to penalization and visitation, this process always terminates in a finite number of steps. Empirically, across the benchmark graphs, convergence was typically achieved in fewer than five iterations even for networks with thousands of nodes, confirming both theoretical guarantees and practical efficiency.

Datasets and proxy network rationale

Real, large-scale, labeled Social Internet of Things (SIoT) device graphs remain unavailable due to privacy restrictions, proprietary ownership, and instrumentation constraints. Consistent with established practice in IoT and SIoT research, we therefore adopt proxy datasets—well-studied real-world networks from adjacent domains that embody structural and trust-related properties essential to SIoT overlays 28,29,30,31. Our aim is to evaluate the robustness of our discovery algorithm (Algorithm 1), specifically its class-aware \(\alpha\)-filtering and trust-weighted greedy traversal with optional fallback, under diverse topological regimes.

Selection principles Datasets were chosen to satisfy four criteria: (i) Structural realism—small-world effects, heterogeneous degree distributions, and non-trivial clustering mirroring SIoT overlays; (ii) Trust semantics or analogues—directed or weighted endorsements usable as per-edge priors for \(r(u,v,\zeta )\) (Sec. 3.2); (iii) Topological diversity—dense webs, sparse modular graphs, and large-scale core–periphery structures to probe sensitivity to \(\alpha\), Top–K, and hop bounds; (iv) Scale—from small ego-centric graphs to massive trust networks to assess traversal behavior and scalability.

Mapping to SIoT semantics For evaluation, nodes are interpreted as device identities (or their social proxies), edges as friend/association links (possibly directed/weighted), and service classes \(\zeta\) as capability categories. Edge weights or reputation annotations provide priors for the per-edge, per-class rating \(r(u,v,\zeta )\). The \(\alpha\)-filtered ISWSIoT is thus the trusted ego-network of the requester, within which Phase B performs deterministic Top–K greedy traversal (Algorithm 1).

Datasets Five publicly available real-world networks were selected from SNAP 28 and the Network Repository 29, each widely used as a surrogate for SIoT evaluation: Bitcoin-Alpha Trust (3,783 nodes, 24,186 edges): a directed, signed “who-trusts-whom” web extracted from a Bitcoin forum 32,33; extensively used in SIoT trust frameworks 34,35. Freeman EIES (34 nodes, 695 edges): interactions among researchers 36; high clustering and tiny diameter emulate tightly knit SIoT subnetworks 37. Facebook-like Forum (899 nodes, 7,089 edges): an online social graph with strong community structure 38; often used to test SIoT discovery 30,39. Epinions “Who-Trusts-Whom” (131,828 nodes, 841,372 edges): a massive directed trust network of user endorsements 40, widely used in SIoT-style trust propagation and scalability studies 30,41. C. elegans neural network (297 nodes, 2,345 edges): a biological connectome with localized wiring and constrained connectivity 42; a common analogue for static, resource-constrained IoT topologies 43,44.

Network properties Table 1 summarizes the statistics. Collectively, the set spans dense trust webs, modular biological wiring, and massive heterogeneous graphs, enabling systematic evaluation of \(\alpha\)-filtered construction and Phase B traversal.

Threats to validity and mitigations Construct validity: Proxy graphs cannot fully capture device-layer constraints (energy, mobility). We therefore focus on algorithmic mechanisms abstracted from device specifics—\(\alpha\)-filtering, deterministic Top–K, hop bound H, and selective fallback—whose behavior is primarily structural and trust-driven. External validity: To mitigate overfitting to a particular topology, we employ five structurally diverse graphs and report sensitivity to \(\alpha\), K, and H. Trust semantics: Where endorsements are signed/directed (Bitcoin, Epinions), we use them directly in \(r(u,v,\zeta )\); where absent, \(r(\cdot )\) defaults to symmetric, topology-informed priors consistent with Sec. 3.2. Reproducibility: All preprocessing, parameters, and random seeds are fixed, ensuring deterministic mapping (trust \(\rightarrow\) degree in \(G_\alpha\) \(\rightarrow\) node ID).

Structural visualization and degree profiles Figure 3 depicts the structural diversity of the five graphs, and Fig. 4 shows their degree distributions (Value = node degree; Count = frequency). Together with Table 1, these confirm that the benchmarks span the principal regimes our algorithm must handle. (a) EIES. Two tightly knit communities form a quasi-clique, consistent with high clustering (0.732) and tiny diameter (2). The narrow degree distribution implies Phase A preserves connectivity and Phase B rarely needs fallback. (b) C. elegans. Several modules and peripheral nodes align with moderate clustering (0.169) and larger diameter (14). The skewed but narrow degree profile means aggressive \(\alpha\) can disconnect modules; fallback supports completeness. (c) Facebook-like. A dense “hairball” core and diffuse periphery yield moderate path lengths (diameter 9). The heavy-tailed degree distribution motivates Top–K pruning to control hub expansion. (d) Bitcoin-Alpha. Core–periphery structure with heterogeneous degree (diameter 10) yields strongly heavy-tailed distributions. Trust-weighted \(r(u,v,\zeta )\) and \(\alpha\) prune unreliable edges, while Top–K constrains growth near hubs. (e) Epinions. A large-scale core with radial communities and extreme heavy-tailed distribution (diameter 14). Scalability depends critically on Phase A pruning and Phase B Top–K; small changes in \(\alpha\) markedly alter eligibility.

Collectively, across the five graphs we capture (i) dense social cliques (EIES), (ii) modular wiring (C. elegans), (iii) community-rich social networks (Facebook-like), and (iv) large trust-endorsed webs with heavy tails (Bitcoin, Epinions). This validates our use of proxies and ensures that evaluation probes the structural and trust conditions most relevant to Algorithm 1.

Structural layouts of the five proxy networks used to evaluate the proposed SIoT discovery algorithm. (Left to right, top to bottom: (a) EIES; (b) C. elegans neural wiring; (c) Facebook-like Forum; (d) Bitcoin-Alpha trust network; (e) Epinions trust network). The layouts emphasize clustering, community structure, and core–periphery organization, highlighting contrasting traversal challenges under \(\alpha\)-filtering and greedy discovery.

Degree distribution profiles of the five proxy networks. Each plot shows node degree (Value) versus frequency (Count), revealing regimes from near-clique density (EIES) to modular low-degree wiring (C. elegans), community-rich heavy tails (Facebook-like), and very long right tails in large trust webs (Bitcoin-Alpha, Epinions). Together with Table 1, these profiles confirm that the suite spans clique-like, modular, community-rich, and heavy-tailed structures.

Experimental setup

All experiments were implemented in Python and executed on a multi-core workstation (12 logical workers; no GPU used). The software stack followed our repository’s environment file and included networkx (\(\ge\)2.8) for graph processing, numpy (\(\ge\)1.20) and pandas (\(\ge\)1.3) for array and data handling, and matplotlib (\(\ge\)3.5) and seaborn (\(\ge\)0.11) for visualization. Additional dependencies were scikit-learn (\(\ge\)1.0) for evaluation pipelines and tqdm (\(\ge\)4.64) for progress reporting. We employed process-level parallelism with WORKERS set programmatically to \(\max (4,\lfloor \mathrm {CPU\_count}/2\rfloor )\) (12 on our machine). All experiments employ the canonical deterministic ranking rule (trust \(\downarrow\) \(\rightarrow\) degree \(\downarrow\) \(\rightarrow\) ID \(\uparrow\)), identical to that defined in Algorithm 1, ensuring strict reproducibility of traversal outcomes across datasets and trials.

Baseline algorithms To ensure a fair and interpretable comparison, all baseline algorithms were executed over the same trust-filtered subgraph \(G_{\alpha }\) used by our proposed method. This guarantees identical node and edge availability across all searches. The following baseline heuristics were evaluated:

-

Depth–first search (DFS): A deterministic traversal exploring each neighbor recursively to maximum hop depth H. DFS ignores trust and class weights, providing a purely topological lower bound on discovery cost.

-

Breadth–first search (BFS): Expands nodes level by level up to H hops. As with DFS, it disregards trust or class attributes and therefore represents an unweighted exploration benchmark.

-

A* search: Employs a composite cost function \(f(v) = g(v) + h(v)\), where g(v) is the accumulated hop count and h(v) is a Euclidean–like heuristic in the trust–class space: \(h(v) = (1 - CR(v,\zeta _q)) + \lambda \, d_c(v,\zeta _q)\). Here \(CR(v,\zeta _q)\) is the class–specific trust score and \(d_c(v,\zeta _q)\) is the normalized class–mismatch distance. This enables cost-aware prioritization of trustworthy and semantically relevant providers.

-

Best–first search (Best–FS): A greedy variant of A* where \(f(v)=h(v)\), ranking candidates solely by descending trust and class similarity. It approximates a single-step lookahead under the same evaluation domain as our dual-control model.

Additionally, we include one SIoT–specific reference baseline, Reputation–Guided BFS (RGBFS), which biases conventional BFS by weighting expansion order according to local trust reputation scores. For node v, the expansion priority is set as \(p(v) = \textrm{deg}(v)^{\beta } \cdot CR(v,\zeta _q)\), where \(\beta \in [0.5,1.0]\) controls the influence of structural connectivity. This baseline captures socially aware but non–class–adaptive discovery, thereby bridging conventional graph traversal and our class–trust integrated design. All baselines were implemented within the same experimental framework and evaluated using identical K, H, and \(\alpha\) parameters to ensure methodological parity. This baseline is consistent with established SIoT trust management principles in which local reputation guides selection and interaction 45,46.

Graph ingestion and preprocessing Datasets are loaded exactly as configured in our project (see Sec. 4). Directedness and weights are preserved where provided by the source files. For trust-bearing graphs (Bitcoin-Alpha, Epinions), per-edge trust in [0, 1] is read (Bitcoin-Alpha) or assigned during preprocessing (Epinions). For the Facebook-like Forum graph, edges are treated as undirected and assigned trust\(=1.0\) at ingestion to reflect homogeneous social ties. The EIES and C. elegans graphs are imported in their native formats; where an edge lacks an explicit trust attribute, the filtering routine treats it as trusted by default (see filtering rule below). After trust assignment, graphs are serialized (*.gpickle) for repeatable evaluation.

Trust filtering and evaluation subgraph Given a threshold \(\alpha \!\in \![0,1]\), we construct \(G_\alpha\) by removing edges whose trust\(<\alpha\). If an edge carries no trust attribute, the filter defaults to trust\(=1.0\) (conservative acceptance). We then compute the largest connected component (LCC) of \(G_\alpha\) on the undirected projection and report its LCC ratio (component size divided by |V| prior to filtering). To stabilize the \(\alpha\)–sweep near extreme thresholds, we adopt a carry-forward policy: if the LCC ratio drops below 0.50, we still record the LCC ratio but carry forward the previous step’s discovery metrics, avoiding spurious jumps when the search space becomes degenerate.

Service availability model and queries For each trial, we randomly designate a small set of provider nodes for the queried class: \(\min (\max (1,\lfloor 0.05\,|V|\rfloor ),\,5)\) targets are chosen uniformly at random and labeled with service \(=\) target_service. The requester/source is sampled uniformly from the remaining nodes. This yields a realistic “few providers” regime while bounding variance. Randomness is reproducible: we use a fixed global seed and derive per-trial seeds deterministically by \((\text {seed}+1000\times \text {alpha\_index}+\text {run\_index})\).

Service classes and taxonomy The class set \(\textit{CLASSES}=\{\zeta _1,\dots ,\zeta _m\}\) is abstract and taxonomy-agnostic in our proxy evaluation; experiments issue single-class queries, one class per trial. Providers are labeled with the queried class \(\zeta _q\) for that trial (Sec. 5, “Service availability model and queries”). The illustrative SIoT network in Fig. 1 is conceptual and serves to show how trust and class semantics can coexist within the framework; it is not imposed as a fixed categorical structure in the proxy evaluation. This setup isolates the effect of trust filtering and traversal controls (\(\alpha\), K, H) from any particular domain taxonomy, and results are therefore class-agnostic and independent of the specific choice or number of classes m.

Discovery algorithm and controls Unless otherwise stated, Phase B uses Top–K greedy with \(K=6\) and hop bound \(H=6\). Neighbor expansion is ranked by (trust descending, node ID ascending), ensuring deterministic tie-breaking. We evaluate two modes: Greedy (strict \(\alpha\) at every hop) and Greedy+Fallback (if no neighbor passes \(\alpha\) at a hop, relax \(\alpha\) for that hop only while keeping Top–K).

\(\alpha\)–sweep and trial budget We sweep \(\alpha \in \{0.1,0.2,\dots ,0.9\}\). For each dataset and each \(\alpha\), we run 100 independent trials in both modes (Greedy / Greedy+Fallback) on the LCC of \(G_\alpha\). Parallel execution (WORKERS=12) is used across trials, and intermediate CSVs are checkpointed for reproducibility. In addition, we executed a smaller validation with \(K=3\) on 10 trials per \(\alpha\), which confirmed that our conclusions remain unchanged; these results are omitted here for brevity.

Metrics and timing We report: (i) SuccessRate—fraction of trials that reached a provider within H hops; (ii) AvgHops—hop count on successful trials; (iii) AvgVisited—number of expanded nodes per trial; (iv) AvgTime—per-trial wall-clock time measured with time.time() (aggregated over trials); and (v) LCC ratio after trust filtering. We additionally log whether fallback was needed and used on each trial for diagnostic analysis. All time values are reported in milliseconds (ms) throughout the paper.

Artifacts and plotting All figures in Fig. 5 are rendered directly from the CSVs produced by the harness (trust_threshold_sensitivity_top6_trials100_greedy.csv and _fallback.csv). The comparative timing in Table 5 reflects 100 matched runs per algorithm and dataset. To ensure cross-dataset comparability, all timing values have been harmonized to milliseconds (ms), and each panel and table explicitly labels units.

Integration and communication overhead (Illustrative) Although protocol-level implementation is beyond the scope of this study, the proposed discovery framework can be readily mapped onto lightweight IoT communication standards for deployment. A minimal realization could employ a hierarchical topic or URI structure to encapsulate discovery requests and responses, consistent with the message-exchange pattern of the publish–subscribe or request–response systems. Under the same Top–K and hop bound H configuration used in our experiments, a single discovery episode would involve approximately \((K\times H + 2)\) short control messages—one request, one aggregation acknowledgment, and K per-hop candidate notifications—resulting in negligible wire overhead. This estimate serves purely as an illustrative reference to demonstrate that the proposed method remains compatible with constrained SIoT communication budgets, even when implemented atop standard low-power messaging frameworks.

Reproducibility and artifacts The complete implementation, configuration files, and evaluation scripts for this study are publicly available at: https://github.com/AbdulRehman88/SIoT_Discovery_Eval. All results in this paper were generated from commit e8e554e using Python 3.10 on Windows 10 (x64) with dependencies listed in requirements.txt and environment.yml. The repository includes source code under src/, configuration files (config.yaml), and plotting scripts used to produce all reported figures. Intermediate CSV artifacts and summary logs are available under results/, ensuring full reproducibility of all metrics and plots. The datasets used (EIES, Epinions, Facebook Forum, Bitcoin Alpha, and C. elegans) are publicly accessible from the Stanford SNAP Repository and Network Repository, as noted in the repository documentation. An archival snapshot will be deposited on Zenodo for long-term accessibility.

Results and discussion

The evaluation of the proposed SIoT discovery algorithm uses the five proxy datasets above to demonstrate generality and robustness. Performance is analyzed with respect to the trust threshold \(\alpha\), which governs pruning during construction of the Individual’s Small-World SIoT (ISWSIoT). The results validate our design choices, showing that discovery reliability, efficiency, and scalability are preserved across operating regimes.

Figure 5 summarizes sensitivity to \(\alpha\) across datasets and both algorithm modes (Greedy and Greedy+Fallback). Panel 5a shows success rising rapidly from permissive to moderate thresholds and stabilizing around \(\alpha \approx 0.4\)–0.6, indicating that once a trusted backbone is established, further tightening yields diminishing gains. Panel 5b reports modest, stable hop counts despite stricter filtering, evidencing preserved small-world navigability within \(G_\alpha\). Temporal performance (Panel 5c) mirrors hops: latency remains low and increases only under very strict thresholds where connectivity fragments, demonstrating that enforcing trust does not compromise responsiveness. Overhead trends (Panel 5d) show visited nodes decreasing with larger \(\alpha\) as the effective search space contracts; the large-scale case (Panel 5f, Epinions) confirms bounded overhead even at scale. Structural resilience (Panel 5e) is maintained: a substantial LCC persists under filtering, ensuring discovery feasibility.

Taken together, the algorithm achieves high success with short paths and low latency while controlling overhead via trust-guided pruning and retaining a resilient connected core. Greedy+Fallback safeguards progress when a hop lacks eligible neighbors by applying a one-hop, bounded relaxation for traversal only: if no outgoing edge at the current node satisfies \(r(u,v,\zeta )\!\ge \!\alpha\), the algorithm temporarily admits edges with \(r(u,v,\zeta )\!\ge \!\alpha '\) (with \(\alpha '\!<\!\alpha\)) for exactly one transition, after which the original \(\alpha\) constraint is reinstated. Crucially, provider acceptance remains governed by Eq. 4: a returned \((f,\zeta )\) must still satisfy \(r(u,f,\zeta )\!\ge \!\alpha\). Empirically, Table 3 shows that this mechanism is rarely triggered (activation \(<\!0.27\) across datasets) and, when invoked, succeeds with high probability (0.68–0.72 conditional success), preserving continuity without compromising trust.

Trust-threshold (\(\varvec{\alpha }\)) sensitivity across datasets and discovery strategies. Panels (a)–(e) present aggregated results across five representative datasets for the Greedy and Greedy+Fallback strategies. As the trust threshold \(\alpha\) increases, success rates rise and then plateau, hop counts remain bounded, and latency (in milliseconds) closely tracks the hop behavior, confirming low computational overhead. The number of visited nodes decreases monotonically with stricter trust filtering, reflecting reduced exploration scope, while the LCC ratio quantifies residual connectivity after trust-based pruning. Panel (f) focuses on the large-scale Epinions graph to illustrate scalability and overhead trends under increasing \(\alpha\). Collectively, these patterns demonstrate that trust filtering governs the trade-off between reliability and overhead in SIoT discovery. LCC ratios are computed under directed-weak connectivity, with undirected projection yielding nearly identical values (\(\Delta \le 0.03\) across datasets; see Table 2).

Table 2 quantifies structural resilience by contrasting undirected and directed-weak connectivity of the Largest Connected Component (LCC) under trust filtering. Across datasets, LCC ratios remain high (0.83–0.92 undirected; 0.80–0.91 directed), indicating that the network retains a strongly connected core even after pruning low-trust edges. The marginal decline (\(\le\)0.03 difference) between undirected and directed projections confirms that information-flow asymmetry is limited and that bidirectional trust links are sufficiently dense to sustain discoverability. This robustness supports the claim that trust enforcement primarily trims peripheral or redundant links without fragmenting the functional backbone, ensuring that service discovery remains feasible and scalable under realistic social trust distributions.

Across all datasets, Table 3 quantifies how frequently the fallback module was triggered and how often it succeeded once activated. The activation frequency remains below 0.27 in all cases, confirming that the Greedy phase alone resolves over 70–80% of discovery requests even under stringent trust thresholds (\(\alpha \le 0.3\)). The slightly higher activation rate observed in the EIES and C. elegans networks reflects their denser but locally clustered topology, where occasional trust discontinuities interrupt Greedy progression. In contrast, large-scale graphs such as Bitcoin and Epinions exhibit lower activation rates (\(\approx\)0.13–0.15), indicating that long-range trust paths provide adequate connectivity even as \(\alpha\) increases.

Conditional success once fallback is engaged remains consistently high approximately 0.68–0.72 across all datasets demonstrating that the secondary exploration policy effectively re-routes stalled searches without excessive traversal cost. This steady success ratio confirms that the fallback stage preserves service reachability by relaxing the strict trust constraint only when necessary, validating the “dual-control” design principle of our framework. Together with the \(\alpha\)-sensitivity plots in Fig. 5, these statistics highlight that the Greedy+Fallback strategy sustains discovery continuity while avoiding redundant activations, achieving a balanced compromise between trust selectivity and topological resilience.

Table 4 explores provider-fraction sensitivity on the representative EIES graph, comparing Random and Degree-based service-selection policies under moderate and strict trust regimes (\(\alpha =0.5\) and 0.7). The Degree-based policy consistently achieves higher success rates (0.89 vs. 0.85 at \(\alpha =0.5\); 0.87 vs. 0.82 at \(\alpha =0.7\)) while requiring fewer hops and visiting fewer nodes, confirming that prioritizing high-degree trusted neighbors accelerates service reachability. Latency gains remain modest (\(\approx\)7–9 %), indicating that the efficiency advantage stems primarily from improved local branching rather than longer processing time. As trust constraints tighten (\(\alpha =0.7\)), both policies maintain sub-millisecond responsiveness, evidencing that controlled provider diversity preserves small-world navigability even when available peers are reduced.

Clarification. Table 4 examines policy effects under a fixed provider fraction p. Provider density itself is controlled independently (Sec. 3) via a fixed-fraction model \(p\in {0.05,0.10,0.15,0.20}\). These findings validate that intelligent provider-selection complements the proposed trust-aware search, enhancing success and stability without compromising real-time feasibility.

Comparative evaluation against baseline search strategies We compare the proposed class-based discovery (trust-aware greedy on \(G_{\alpha }\) with selective fallback) against four search baselines: Breadth-First Search (BFS), Depth-First Search (DFS), A* (\(f(n)=g(n)+h(n)\)), and Greedy Best-First Search (Best-FS, \(f(n)=h(n)\)). For each dataset, Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 report per-algorithm histograms over 100 runs (panels a–e) and a run-wise overlay (panel f). Table 5 summarizes mean execution time across these runs.

Table 6 summarizes the aggregated statistics for Greedy mode across all datasets, reporting mean ± 95 % confidence intervals for success, hops, and latency. Success rates gradually decline from 0.87 (EIES) to 0.55 (Epinions) as network scale increases, reflecting the rising sparsity of strong-trust links. Nevertheless, hop counts remain bounded below six and latency stays within 2 ms even in the largest network, reaffirming low-overhead scalability. The narrow confidence intervals (width \(\le\) 0.05) across all metrics demonstrate stable performance and limited variance over multiple \(\alpha\)-settings. This statistical consistency confirms that the trust-aware greedy mechanism delivers predictable behavior across heterogeneous SIoT topologies, a key property for dependable online discovery.

Uncertainty and significance analysis To quantify variability, each metric in Table 6 and related evaluations is reported as mean ± 95% confidence interval (CI) across \(N=100\) discovery trials per dataset and configuration. Confidence bounds were computed using the Student’s t-distribution and are expressed in brackets, e.g., \(\mu ~[L,U]\). Paired t-tests between the Greedy and Greedy+Fallback modes confirmed statistically significant improvements in success rate (\(p<0.01\)) on the large-scale Bitcoin and Epinions graphs, while hop counts and latency differences remained within overlapping intervals for smaller networks. These findings validate that the observed gains are consistent rather than random fluctuations and that the proposed dual-control mechanism maintains stable behavior across heterogeneous SIoT topologies.

Across the large social/trust graphs (FB Forum, Bitcoin, Epinions), the proposed method achieves the lowest or near-lowest mean runtime while maintaining the reliability–overhead trade-offs in Fig. 5. On FB Forum it is best (1.04 ms), improving over Best-FS (1.10 ms; \(\approx\)5%), BFS (1.14 ms; \(\approx\)9%), DFS (1.74 ms; \(\approx\)40%), and A* (2.06 ms; \(\approx\)50%). On Bitcoin it is again fastest (1.31 ms), outperforming BFS (1.88 ms; \(\approx\)30%), DFS (2.08 ms; \(\approx\)37%), A* (2.65 ms; \(\approx\)51%), and slightly edging Best-FS (1.35 ms; \(\approx\)3%). On the largest graph, Epinions, it yields a substantial advantage (1.22 ms), improving over BFS (2.28 ms; \(\approx\)46%), DFS (1.87 ms; \(\approx\)35%), Best-FS (1.90 ms; \(\approx\)36%), and A* (3.35 ms; \(\approx\)64%). These gains follow from Phase A pruning that bounds branching, deterministic Top–K expansion with \(\deg _{G_\alpha }\) tie-breaking that contains hub effects, and selective fallback that avoids worst-case backtracking.

On the two smaller graphs, differences compress. For C. elegans, the proposed method (0.34 ms) is second only to DFS (0.28 ms) yet improves over BFS (0.47 ms), Best-FS (0.60 ms), and A* (1.05 ms). The small, modular topology limits branching, allowing DFS occasional early hits; nevertheless, our method remains competitive while preserving trust constraints. On EIES, all algorithms run at microsecond scale; DFS and BFS are fastest (0.0004 ms and 0.0006 ms), while the proposed method (0.0016 ms) still improves over Best-FS (0.0021 ms) and A* (0.0026 ms). Here, the overhead of maintaining \(r(u,v,\zeta )\) is only visible because the graph is near-clique; at realistic SIoT scales (Bitcoin/Epinions) pruning benefits dominate.

Distributional evidence in panels (a)–(e) of Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 reinforces these conclusions: proposed-method histograms concentrate in the lowest time bins with shallow right tails (stable runtime), while A* shows heavy tails (heuristic sensitivity) and DFS spreads wider on large graphs (backtracking). Run-wise overlays (panel f) show the proposed method hugging the lower envelope with fewer spikes, especially on the largest graphs.

Beyond empirical performance, Table 8 consolidates qualitative trade-offs. Classic uninformed searches (DFS/BFS) are simple but risk incompleteness (DFS) or high memory at scale (BFS). A* is optimal under an admissible heuristic but may degrade when heuristic error accumulates on large, complex graphs. Greedy Best-FS advances quickly but lacks completeness/optimality guarantees. Our trust-aware greedy strategy retains heuristic efficiency while introducing rank-based evaluation \(f(n)=r(n)\) that prioritizes class-specific trust, reducing explored nodes compared with uninformed searches and avoiding the heuristic over-dependence of A* and Best-FS. Theoretical time/space orders remain comparable to heuristic baselines (\(O(n\log n)\) with a priority queue; O(V) space), but the trust-aware evaluation yields the practical efficiency observed in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 and Table 5.

Robustness under noisy or adversarial trust perturbations To assess resilience against adversarial or corrupted trust inputs, we introduced controlled perturbations of edge ratings in the Epinions network. A random fraction \(p \in {5\%,10\%,15\%,20\%}\) of trust values was modified by additive noise of amplitude \(\delta \in {0.05,0.10,0.15}\), producing perturbed ratings \(r'(u,v,\zeta )=r(u,v,\zeta )\pm \delta\), bounded to [0, 1]. This configuration emulates both stochastic noise and adversarial manipulation of trust relationships. The resulting discovery performance under these perturbations is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7 presents the robustness evaluation on Epinions, where probabilistic perturbations of trust weights (p = 5–20%) were applied under varying disturbance amplitudes (\(\delta\) = 0.05–0.15). Success rates decline smoothly from 0.54 to \(\approx\)0.46 as noise intensity increases, demonstrating graceful degradation rather than abrupt collapse. Even at 20% perturbation, more than 45% of requests still resolve successfully, highlighting inherent resilience to trust uncertainty. This tolerance stems from redundant high-trust paths and the dual-mode fallback, which together buffer against localized inconsistencies in \(r(u,v,\zeta )\). The gradual slope of degradation validates that the framework maintains operational reliability under imperfect or dynamically fluctuating trust estimates, an essential property for robust and scalable real-world SIoT deployments.

Table 9 consolidates overall baseline performance at \(\alpha = 0.6\) for both Greedy (G) and Greedy+Fallback (G+F) modes, summarizing success rate, hops, visited nodes, and latency. Incorporating fallback consistently improves success by 3–5 % while reducing traversal depth and overhead. Latency gains are modest (\(\approx\)2–3 %) yet consistent, confirming that selective fallback enhances reliability without imposing computational penalties. The effect amplifies with network size: improvements are most pronounced on Bitcoin and Epinions, where long-range trust links are sparse. These balanced improvements illustrate that the hybrid search achieves higher reachability while maintaining lightweight, sub-2 ms responsiveness, fulfilling the study’s core objective of combining trust enforcement with real-time efficiency across heterogeneous SIoT scales.

Validation of hypotheses

The empirical results support the hypotheses formulated in the Introduction:

-

H1 (Trust threshold effectiveness): Confirmed. Across datasets, success improves from permissive to moderate thresholds and stabilizes around \(\alpha \approx 0.4\)–0.6, consistent with the claim that \(\alpha \ge 0.5\) yields better discovery than permissive settings (see Fig. 5a; narrative in Results).

-

H2 (Dual-parameter efficiency): Confirmed. Visited nodes decrease as \(\alpha\) increases, while hop counts remain modest and stable; latency mirrors hops and remains low under moderate \(\alpha\) (Fig. 5b–d).

-

H3 (Latency–exploration tradeoff): Confirmed. Larger K and higher hop bounds increase the probability of success with only moderate increases in latency (Fig. 5c; discussion).

-

H4 (Fallback robustness): Confirmed. When strict trust filtering leaves a hop without eligible neighbors, the fallback mechanism restores progress with limited overhead (Greedy vs. Greedy+Fallback behavior in Fig. 5 and accompanying text).

For runtime, the proposed method attains the lowest or near-lowest mean execution time on the large graphs while remaining competitive on the small graphs (Table 2; Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 , aligning with the bounded-branching design. The empirical relationship quantified in Table 10 reinforces this observation. Success increases monotonically with both K and H, rising from 0.72 (\(K = 3\), \(H = 3\)) to 0.89 (\(K = 9\), \(H = 7\)), confirming that broader candidate expansion and deeper search horizons progressively enhance reachability. The diminishing incremental gain beyond \(K \ge 7\) and \(H \ge 5\) suggests a practical convergence point where additional exploration yields limited benefit relative to cost. This quantification empirically substantiates the proposed dual-parameter control mechanism, which balances completeness and responsiveness by adaptively bounding both expansion width and depth in real-time discovery. These patterns, together with the K/H sweep in Table 10 (where \(K \in \{3,5,7,9\}\)), confirm that the reported conclusions are not contingent on \(K=5\) and remain stable across practical branching widths.

Significance analysis against baselines

To address whether the proposed method offers statistically significant improvements over classical graph traversal algorithms, we conducted pairwise Welch’s t-tests comparing the Greedy method against four baselines BFS, DFS, A*, and Best-First Search on the nodes-visited metric at \(\alpha =0.5\). All algorithms operated on the same trust-filtered graph \(G_\alpha\) with identical search parameters (\(K=6\), \(H=6\)) over \(N=100\) independent trials per configuration. Table 11 provides an aggregate summary indicating the number of datasets (out of four) where statistically significant differences were observed, along with median p values and mean Cohen’s d effect sizes. Table 12 presents the complete pairwise comparisons for each dataset, including mean nodes visited, t-statistics, and exact p values.

The results reveal a nuanced pattern. The proposed method significantly outperforms DFS on all four datasets (\(p<0.001\), mean \(d=-1.305\)), demonstrating large practical gains from trust-aware prioritization over uninformed depth-first traversal. Against Best-First Search, significant reductions in nodes visited were observed on three of four datasets (FB_Forum: \(t=6.88\), \(p<0.001\); Caenorhabditis: \(t=2.41\), \(p=0.018\); Epinions: \(t=3.23\), \(p=0.002\)), with a mean effect size of \(d=-0.302\). Comparisons with BFS and A* yielded significant differences only on the largest dataset (Epinions), where the proposed method visited 70% fewer nodes than BFS (4,107 vs. 13,649; \(p<0.001\)) and 69% fewer than A* (4,107 vs. 13,211; \(p<0.001\)). On smaller graphs (EIES, FB_Forum, Caenorhabditis), performance was statistically comparable to BFS and A*, indicating that the trust-class heuristic matches the efficiency of these informed baselines while providing consistent, significant improvements as graph scale increases. BitcoinAlpha was excluded from this analysis because the trust-filtered graph becomes too sparse at \(\alpha \ge 0.3\) for meaningful baseline comparison.

Limitations and future work

While the proposed algorithm demonstrates strong theoretical properties and empirical performance, several limitations should be acknowledged.

Use of proxy datasets and SIoT realism considerations Our evaluation employed five publicly available graphs from established repositories (SNAP, Network Repository) as proxies for SIoT networks, consistent with the prevailing practice in the SIoT literature 30,31,34. While these datasets capture essential structural properties of social-trust overlays including small-world clustering, heterogeneous degree distributions, and directed trust endorsements, they represent static snapshots rather than live SIoT deployments. Consequently, three characteristics of real-world SIoT environments are not reflected in our evaluation:

-

1.

Device mobility: In SIoT systems deployed, devices may join, leave, or relocate, causing continuous topology changes. Our proxy graphs treat the node set and edge structure as fixed throughout the experiment and thus do not capture the effects of churn or spatial reconfiguration on discovery performance.

-

2.