Abstract

Weight stigma remains a major public health issue that negatively impacts individuals living with obesity. This study explores its prevalence in the Spanish adult population and examines whether viewing obesity as a disease influences societal attitudes. A representative sample of 1,000 adults participated in a Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview assessing knowledge, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination related to obesity, along with sociodemographic data and personal beliefs about its causes. While 40.8% attributed obesity to a lack of self-control, 59.2% considered it a disease. Those in the latter group were more likely to recognize its multifactorial causes and support public funding for treatment. However, weight bias remained prevalent across both perspectives, with no significant differences in discriminatory attitudes. Around 30% of participants admitted to holding negative stereotypes or engaging in weight-based discrimination. These findings suggest that simply framing obesity as a disease does not meaningfully reduce weight stigma. Broader efforts are needed—beyond education alone—to challenge societal narratives and address structural contributors to bias, ultimately fostering a more supportive and inclusive environment for individuals affected by obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Weight stigma is a global public health issue that not only affects individuals living with obesity but also has far-reaching consequences for healthcare systems and research investment1,2,3. The stigma associated with obesity contributes to poorer health outcomes, as individuals who experience weight bias may avoid seeking medical care, leading to delayed diagnoses and inadequate treatment4,5. Furthermore, weight-based discrimination within healthcare settings compromises the quality of care, reinforcing biases that can result in misdiagnoses or inappropriate treatment recommendations6,7. Additionally, weight stigma undermines funding for obesity research, as obesity is often perceived as a preventable condition requiring only individual effort and behavioral changes, discouraging investment in innovative treatments and interventions8.

Our research group recently conducted a study exploring societal attitudes toward obesity in Spain, analyzing both explicit rejection and subtle stigmatization across a diverse range of body weights, from normal weight to morbid obesity9. The findings revealed a complex and often contradictory perception of obesity. Surprisingly, individuals with obesity exhibited greater aversion toward the condition compared to those with normal weight, suggesting the presence of internalized weight bias. Additionally, experiences of weight-based stigma were more prevalent among younger individuals, raising concerns about the increasing societal reinforcement of weight discrimination in early adulthood. However, the literature on this topic is not entirely consistent. Some research has shown that individuals with overweight or obesity tend to report lower levels of explicit anti-fat attitudes than those with lower BMI, suggesting a possible protective or defensive mechanism10,11. This apparent discrepancy highlights the complexity of weight stigma, which may manifest differently depending on whether it is internalized, explicit, or implicit.

Over the past years, the Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity (SEEDO) and other scientific societies dedicated to obesity research have led a major public awareness campaign emphasizing that obesity is a chronic, complex, and relapsing disease with no definitive cure12,13,14. These initiatives highlight not only its detrimental impact on quality of life but also its negative effect on life expectancy. Understanding how these messages are received by the public and whether they contribute to changing societal attitudes is essential for developing more effective strategies to combat weight stigma. The present study aims to quantify the extent of negative attitudes toward individuals with overweight and obesity in the Spanish adult population. Additionally, we seek to assess how deeply ingrained weight stigma is in our society and whether the way obesity is perceived, or access to better information about its causes, represents a turning point in reducing bias.

Results

The Spanish sample, comprising 52.1% females, had a mean age of 49.1 ± 16.1 years and a self-reported BMI of 25.4 ± 7.2 kg/m². Additionally, 50.7% of respondents were classified as having excess weight, with 33.9% categorized as living with overweight and 16.8% as with obesity. Moreover, approximately 59.2% (95% CI: 56.1%–62.2%) believed that obesity is a disease, whereas 40.8% (95% CI: 37.8%–43.9%) attributed obesity to a lack of self-control. Among those who perceived obesity as a disease, the majority were women (66.4%), belonged to a high or medium-high social class (64.5%), and were college graduates (63.1%) (Table 1). However, no significant differences were observed between the two perspectives in terms of age (above or below 45 years), habitat size (more or less than 10,000 inhabitants), or BMI categories (living with overweight/obesity vs. with normal weight/underweight).

When participants were questioned about their awareness of obesity pathophysiology, those who considered obesity a disease were more likely to recognize that weight regulation depends on biological, genetic, and environmental factors rather than solely on voluntary control or willpower (58.4% vs. 35.2%; p < 0.001). Additionally, they were more likely to agree that addressing excess adiposity requires more than simply eating less and exercising more (48.6% vs. 17.6%; p < 0.001), and that medications for managing obesity should be either fully or significantly funded by the Public Health System (74.3% vs. 56.6%; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Participants under 35 years of age were significantly more likely than older participants to acknowledge that weight regulation involves biological, genetic, and environmental factors, not just willpower (60.8% vs. 45.6%, p < 0.001). They also more frequently recognized that addressing overweight and obesity requires more than diet and exercise alone (39.1% vs. 27.3%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, women were more likely than men to agree that treating obesity goes beyond diet and exercise (38.5% vs. 20.6%, p < 0.001).

When participants were asked about their views on societal discrimination, those who consider obesity a disease were more likely to agree that society discriminates against individuals living with obesity or excess weight (78.7% vs. 66.4%, p < 0.001). However, nearly one-third of participants who view obesity as a disease admitted that they have, at some point, experienced prejudice or rejection toward a person living with obesity—a percentage nearly identical to those who believe obesity stems from a lack of willpower (29.0% vs. 29.1%, p = 0.982) (Table 2). Similarly, although the prevalence of negative misconceptions—such as perceiving individuals with obesity as having fewer aptitudes for managerial roles or public office—was low, it did not differ between those who view obesity as a disease and those who attribute it to personal responsibility.

When participants were asked about their feelings towards individuals living with obesity, those who considered obesity a disease reported a similar level of discomfort if their children’s friends were very or quite overweight compared to those who viewed obesity as a lack of willpower (44.0% vs. 38.9%, p = 0.122) (Table 3). Similarly, attitudes towards romantic relationships showed no significant differences between the groups, with both expressing comparable reticence to the idea of falling in love with a partner living with excess weight. Interestingly, individuals living with overweight or obesity themselves were more likely to consider such a romantic relationship compared to those without (42.0% vs. 27.7%, p < 0.001). Regarding authority figures, such as politicians or bosses, both groups demonstrated comparable acceptance of individuals living with overweight or obesity.

Discussion

Our study highlights that the belief that obesity is the fault of the individual and linked to a lack of self-control is deeply rooted in Spanish society, with 40.8% of participants endorsing this view. As expected, individuals holding this belief were more likely to express discomfort with overweight individuals in social contexts and to believe that personal effort alone is sufficient for weight management. Conversely, those who perceive obesity as a disease were more likely to recognize its multifactorial nature, acknowledging the role of biological, genetic, and environmental factors in weight regulation. Interestingly, in Spain, the proportion of individuals with this positive perspective is higher than in other countries, such as Canada, where only 28% of people attribute obesity to endocrine or metabolic factors, suggesting cultural differences in how obesity is conceptualized15,16,17. Participants who embraced the pathologization of obesity were also more likely to agree that addressing obesity requires more than just diet and exercise and were more supportive of public health funding for obesity treatments. These perspectives were more commonly expressed by women, individuals from higher social classes, and those with higher education levels, suggesting a possible socioeconomic gap in how obesity is understood. This may reflect greater access to medical information and public health narratives among higher socioeconomic groups, whereas individuals with lower educational attainment may be more likely to internalize traditional and stigmatizing views of obesity18,19.

Interestingly, our findings did not reveal differences in BMI between the two belief groups, with similar rates of overweight and obesity observed in both. This suggests that even individuals with overweight or obesity may internalize weight bias and attribute their condition to personal shortcomings. This aligns with prior research indicating that conceptualizing obesity as a disease does not necessarily reduce weight stigma, as internalized bias can perpetuate negative stereotypes even among those directly affected20.

While some studies suggest that recognizing obesity as a disease can shift causal attributions away from personal responsibility and foster more sympathetic attitudes21, our findings indicate that weight bias persists even among those who conceptualize obesity as a medical condition. Notably, around 30% of participants who identified obesity as a disease admitted to displaying prejudiced attitudes or rejecting individuals with obesity, a percentage nearly identical to those who attributed obesity to a lack of self-control. Although we did not assess internalized weight bias among our participants, prior research has shown that weight stigma is often internalized, perpetuating negative stereotypes even among individuals with obesity, including healthcare professionals22. Therefore, our results suggest that merely pathologizing obesity is insufficient to reduce weight stigma in the general population23. Even professionals specializing in obesity research and treatment exhibit significant weight bias, as demonstrated by both implicit associations and explicit stereotypes. A study involving a multinational sample of healthcare professionals from Australia found that even those who endorse weight as a health heuristic, when presented with a hypothetical patient with obesity seeking care for migraines, tended to focus more on the patient’s weight than on their primary health concern20. This persistent stigma within the healthcare field negatively impacts medical decision-making and the quality of care provided to patients with obesity23,24.

Approximately 30% of the Spanish population acknowledged having experienced prejudice or rejection toward a person with overweight or obesity, feeling uncomfortable if their children’s friends suffer overweight, or expressing reluctance to engage in romantic relationships with individuals living with obesity. Our findings reinforce the notion that weight bias is deeply ingrained in societal and cultural norms, emphasizing personal responsibility while undervaluing systemic and environmental factors.

Our data suggests that the pathologization of obesity alone is insufficient to reduce weight stigma. This underscores the need for a shift in interventions that go beyond merely promoting the recognition of obesity as a disease6,23,25. Efforts to combat weight stigma and reshape public narratives around obesity must engage academic institutions, professional organizations, media, public health authorities, governments, and policy frameworks that perpetuate weight bias, integrating education into the multifactorial nature of obesity with broader strategies that cultivate empathy and reduce stigma7,26. Alternative frameworks, such as the Health at Every Size (HAES) movement, emphasize shifting the focus from weight loss to weight-neutral health outcomes, prioritizing well-being, physical functionality, and overall health rather than body weight27,28.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design prevents us from establishing causal relationships. Second, self-reported data on height, weight, and attitudes may be influenced by acquiescence or social desirability bias and underreporting of weight29,30. Third, a validated questionnaire for directly assessing weight bias and personal experiences of discrimination, such as the Spanish version of the Anti-Fat Attitudes Scale, was not used11,31. This may limit our ability to capture the lived experiences of individuals facing weight-based stigma as well as our comparability with studies using such validated instruments9,17,32. However, our study aimed to capture general population beliefs and perceptions about the causes of obesity rather than to quantify individual prejudice or discriminatory attitudes. Fourth, the main variable was assessed dichotomously, asking participants to classify obesity either as a disease or as a result of lack of control. This approach does not capture the potential coexistence of these views but was designed to contrast the two dominant explanatory frameworks observed in public discourse (i.e., individual responsibility vs. structural/biological causation)33. Additionally, the absence of ethnicity data restricts our ability to analyze subgroup differences, which is particularly relevant given the presence of non-European populations living in Spain. Previous research by our group has demonstrated clear cross-cultural differences in weight discrimination and stigma internalization between Spain and Egypt17.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of societal attitudes toward obesity in a representative sample of the Spanish population. While recognizing obesity as a disease is associated with a better awareness of its multifactorial nature, this recognition alone does not appear to reduce discriminatory attitudes or behaviors toward individuals with obesity. Future research should assess whether public policies that promote empathy, challenge societal norms, and emphasize health and functionality obesity-centric approaches are more effective in preventing the perpetuation of weight stigma and marginalization.

Methods

Study design

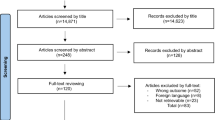

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted to analyze data collected through personal telephone interviews, adhering to established best practices and quality standards for survey research. The survey included 25 closed-ended questions designed to assess stereotypes (cognitive perceptions), prejudice (emotional attitudes), and discrimination (behavioral actions) related to individuals with excess weight or obesity (Supplementary Table 1). The manuscript adhered to the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

The questions were displayed directly on the computer screen for the interviewer, who read them aloud to the participants. This Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) was conducted out in accordance with the ISO 20,252/2012 standard of the Spanish Association for Standardization and Certification for market studies and opinion through the 40 dB company, following the excellence and standards for best practices in survey research34. The interviews averaged 8 min (5–16 min). Responses were documented in real-time using a standardized data entry system, ensuring accuracy and consistency. No additional data transformation or manipulation was performed after recording the responses.

Participants

Between 9 February and 14 February 2023, a total of 1,000 participants were recruited through a market research company (40dB, Madrid, Spain) to generate a representative sample of the Spanish population aged 18 years and older. Participants were contacted by telephone. Interviewers explained the study objectives, ensured data confidentiality, and obtained verbal informed consent before starting the questionnaire. Participation was entirely voluntary, and no economic compensation was provided.

Quota sampling, which is a non-probability sampling method, was applied to ensure the sample was approximately representative of the Spanish demographic distribution based on sex, age, region (excluding Ceuta and Melilla), and habitat size. Depending on the size of the region, population ranged from 0.6% from Navarra to 17.6% from Andalusia. A sample size of 1,000 individuals provides a statistical power of 95.5% and a margin of error of ± 3.1% for detecting differences in binary variables where p = q, assuming simple random sampling.

Participants were asked a single question to assess their familiarity with scientific information about the causes of obesity: “Today we know that weight regulation depends on biological, genetic, and environmental factors, not on a person’s voluntary control or willpower. Were you aware of this fact?” (Yes/No). This item was intended to capture awareness of established evidence rather than a detailed understanding of causal mechanisms.

Measures

The demographic section of the interview included questions on sex (binary classification), age (six categories), habitat size (six categories), social class (three categories), educational level (three categories) and self-reported height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI) (four categories). Participants were classified according to the WHO BMI categories as follows: (i) underweight (BMI < 18.5), (ii) normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), (iii) overweight (BMI 25–29.9), and (iv) obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²). Due to the small number of participants initially classified as underweight, this group was combined with the normal weight category for analysis to ensure a more balanced distribution across BMI groups. The final BMI categories used for analysis were: non-overweight, overweight, and obesity.

The sample was representative of the Spanish population in terms of BMI distribution. According to the ENE-COVID study35, the prevalence of overweight and obesity (BMI > 25 kg/m²) in Spain is 55.8% and 17.6%, respectively, whereas in our sample these figures were 50.7% and 16.8%. Both studies relied on self-reported anthropometric data, although ENE-COVID was based on face-to-face interviews, while our survey was conducted by telephone.

Explicit weight bias was assessed through 25 items in the questionnaire, measuring the extent to which individuals expressed stereotypes, prejudice, and discriminatory attitudes toward individuals with excess weight. Response options for these items varied, providing descriptive variables with two to five categories.

Statistical analysis

Given the categorical nature of all assessed variables, descriptive statistics were expressed as percentages. Frequency tables were used to compare the percentage of approval for each value of the qualitative data. Pearson chi-square tests were conducted to assess differences between groups. Exploratory analyses were performed to simplify the original contingency tables into 2 × 2 tables, allowing for the calculation of comparable p-values. Subjects were classified into one of two groups: the former comprised subjects who self-reported that believe that obesity is due to a lack of self-control while the latter comprised those who reported obesity as a disease. All statistical tests were two-sided, with significance set at p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were conducted using the R statistical software package (version 4.2.1).

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Di -, E. et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: Individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 388, 776–786 (2016).

Fruh, S. M., Graves, R. J., Hauff, C., Williams, S. G. & Hall, H. R. Weight bias and stigma: Impact on health. Nurs. Clin. North. Am. 56, 479–493 (2021).

Puhl, R. M. Weight stigma and barriers to effective obesity care. Gastroenterol. Clin. North. Am. 52, 417–428 (2023).

Puhl, R. M. & Heuer, C. A. The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity 17, 941–964 (2009).

Tomiyama, A. J. Stress and obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 703–718 (2019).

Phelan, S. M. et al. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes. Rev. 16, 319–326 (2015).

Rubino, F. et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat. Med. 26, 485–497 (2020).

Busetto, L., Sbraccia, P. & Vettor, R. Obesity management: At the forefront against disease stigma and therapeutic inertia. Eat. Weight Disord. 27, 761–768 (2022).

Sánchez, E. et al. Assessment of obesity stigma and discrimination among Spanish subjects with a wide weight range: The OBESTIGMA study. Front. Psychol. 14, 1209245 (2023).

Lieberman, D. L., Tybur, J. M. & Latner, J. D. Disgust sensitivity, obesity stigma, and gender: Contamination psychology predicts weight bias for women, not men. Obes. (Silver Spring). 20, 1803–1814 (2012).

Macho, S., Andrés, A. & Saldaña, C. Anti-fat attitudes among Spanish general population: Psychometric properties of the anti-fat attitudes scale. Clin. Obes. 12, e12543 (2022).

Mechanick, J. I., Hurley, D. L. & Garvey, W. T. Adiposity-Based chronic disease as a new diagnostic term: The American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology position statement. Endocr. Pract. 23, 372–378 (2017).

Busetto, L. et al. A new framework for the diagnosis, staging and management of obesity in adults. Nat. Med. 30, 2395–2399 (2024).

Lecube, A. et al. The Spanish GIRO guideline: A paradigm shift in the management of obesity in adults. Obes. Facts. 18, 375–387 (2025).

Caixàs, A. et al. Weight-related quality of life in Spanish obese subjects suitable for bariatric surgery is lower than in their North American counterparts: A case-control study. Obes. Surg. 23, 509–514 (2013).

Forouhar, V. et al. Weight bias internalization and beliefs about the causes of obesity among the Canadian public. BMC Public. Health. 23, 1621 (2023).

Sánchez, E. et al. Discrimination and stigma associated with obesity: A comparative study between Spain and Egypt Data from the OBESTIGMA study. Obes. Facts. 17, 582–592 (2024).

Himmelstein, M. S., Puhl, R. M. & &Quinn, D. M. Intersectionality: An understudied framework for addressing weight stigma. Am. J. Prev. Med. 53, 421–431 (2017).

Bernard, M., Fankhänel, T., Riedel-Heller, S. G. & Luck-Sikorski, C. Does weight-related stigmatisation and discrimination depend on educational attainment and level of income? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 9, e027673 (2019).

Rathbone, J. A. et al. How conceptualizing obesity as a disease affects beliefs about weight, and associated weight stigma and clinical decision-making in health care. Br. J. Health Psychol. 28, 291–305 (2023).

Styk, W., Wojtowicz, E. & Zmorzynski, S. Reliable knowledge about obesity Risk, rather than Personality, is associated with positive beliefs towards obese people: Investigating attitudes and beliefs about obesity, and validating the Polish versions of ATOP, BAOP and ORK-10 scales. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 14977 (2022).

Pearl, R. L. & Puhl, R. M. Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 19, 1141–1163 (2018).

Schwartz, M. B., Chambliss, H. O., Brownell, K. D. & Blair, S. N. Billington C. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes. Res. 11, 1033–1039 (2003).

Telo, G. H. et al. Obesity bias: How can this underestimated problem affect medical decisions in healthcare? A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 25, e13696 (2024).

Tomiyama, A. J. et al. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Med. 16, 123 (2018).

Talumaa, B., Brown, A., Batterham, R. L. & Kalea A. Z. Effective strategies in ending weight stigma in healthcare. Obes. Rev. 23, e13494 (2022).

Bacon, L. & Aphramor, L. Weight science: Evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr. J. 10, 9 (2011).

Tylka, T. L. et al. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: Evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J. Obes. 983495 2014 (2014).

Christian, N. J., King, W. C., Yanovski, S. Z., Courcoulas, A. P. & Belle, S. H. Validity of Self-reported weights following bariatric surgery. JAMA 310, 2454 (2013).

Vesely, S. & Klöckner, C. A. Social desirability in environmental psychology research: Three Meta-Analyses. Front. Psychol. 11, 1395 (2020).

Macho, S., Andrés, A. & Saldaña, C. Validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale in a Spanish adult population. Clin. Obes. 11, e12454 (2021).

Tsai, M. C. et al. Attitudes toward and beliefs about obese persons across Hong Kong and taiwan: Wording effects and measurement invariance. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 17, 134 (2019).

Westbury, S., Oyebode, O., van Rens, T. & Barber, T. M. Obesity stigma: Causes, Consequences, and potential solutions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 12, 10–23 (2023).

Draugalis, J. R., Coons, S. J. & Plaza, C. M. Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 72, 11 (2008).

Gutiérrez-González, E. et al. Socio-geographical disparities of obesity and excess weight in adults in spain: Insights from the ENE-COVID study. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1195249 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity (Sociedad Española de Obesidad, SEEDO) supported this study.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding. The Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity (Sociedad Española de Obesidad, SEEDO) supported the costs associated with the design and dissemination of the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.L., R.J.G., I.M., M.M.M.; Data curation: A.L., J.S., B.S-R.; M.M.M.; Formal analysis: A.L., J.S.; Investigation: A.L., A.C., A.B.C., C.M., S.A., R.G-B., C.B., J.B., G.E.U.; Methodology: A.L., J.S., B.S-R., I.M., M.M.M.; Project administration: A.L., M.M.M.; Supervision: A,L.; Visualization: A.L., M.M.M.; Writing—original draft: J.S.; Writing—review & editing: A.L., R.J.G., G.E.U., M.M.M.; Approval of the final version: All.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital, approval number CEIC-2190 (December 16, 2019). This study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and Spanish legislation on the protection of personal data was also followed. Additionally, the study adhered to the ethical standards specified by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) International Code on Market, Opinion, and Social Research and Data Analytics. Participants were asked to join voluntarily and were not awarded any financial or other compensation. As this was a telephone-based survey, no written consent was collected; however, verbal informed consent was obtained in accordance with Spanish legislation on data protection and ethical standards for opinion and social research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lecube, A., Galindo, R.J., Salinas-Roca, B. et al. Awareness of obesity’s causes is not linked to less Weight-Related bias. Sci Rep 15, 45105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32682-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32682-8