Abstract

Smartphones have become essential tools in healthcare, particularly in assessing human posture. This systematic review evaluated mobile applications that utilize photogrammetry to assess body alignment in both the sagittal and coronal planes. The review adhered to PRISMA 2020 guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024573433). We conducted a search across multiple databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, ACM Digital Library, Embase, and Google Scholar. Studies were included if they reported the development, testing, or validation of smartphone apps for posture analysis. Excluded were studies that used wearables, radiographic or sensor-based methods, or those without full-text availability. Two authors independently screened the studies and extracted relevant data. The COSMIN checklist was employed to assess the quality of the studies. A meta-analysis using MedCalc calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and Pearson’s r for assessing reliability and validity. A total of 29 studies involving 1,910 participants were included in the review. The pooled ICCs demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.904) and inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.889) for the craniovertebral angle, while measurements for hip tilt, head tilt, and acromion alignment showed moderate to excellent reliability. Limitations of this review include the restriction to English-language studies, heterogeneity in methods, small sample sizes, and inconsistent reporting (e.g., SEM, MAD). These findings support the clinical utility of smartphone applications for posture assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postural assessment is conducted regularly in health clinics and physical therapy centers1. Various tools are utilized in this process, including quantitative measurements with goniometers and plumb lines, as well as motion capture systems like Vicon and 3D infrared camera systems for visual dynamic assessment2. Although radiological methods are considered the most accurate among posture assessment techniques2 and the gold standard and reliable process, as they allow for clear visualization of bony landmarks3, they are limited in routine clinical application due to cost and radiation exposure4. Radiographs are invasive and thus cannot be used for repeated measures of body segment posture2. As such, Photogrammetry and mobile-based tools offer a non-invasive, more accessible alternative for evaluating external posture based on anatomical landmarks5, though they cannot fully replace the diagnostic value of radiographs. Recently, there has been a growing body of evidence supporting the use of artificial intelligence in patient assessment and treatment. The rise of smartphones has also revolutionized how clinicians access clinical measuring application technologies, including machine learning, deep learning, and computer vision, which show considerable potential in automating diagnostic processes, interpreting medical imaging, and aiding clinical decision-making6.

Mobile health, or mHealth, was a term introduced by Robert Istepanian in 20037. The implementation of mHealth has enabled the monitoring and management of health information for individuals outside clinical and hospital settings8. Mobile devices are primarily used for monitoring individuals with chronic diseases, but they also have applications in medical diagnostics. This includes assessing human biomechanical functions, such as evaluating walking and body posture. Recent advancements in photogrammetry and the assessment of body alignment in both the sagittal and frontal planes have contributed to this field. Smartphones are equipped with built-in sensors such as accelerometers, magnetometers, and gyroscopes, which enable them to assess a human posture9. Numerous mobile software applications1,10,11,12 are now available for posture analysis and assessment. Additionally, mobile applications have emerged as a viable alternative to photogrammetry devices, simplifying the processes of image acquisition and data analysis, while also being more cost-effective1,10,11,12.

In a systematic review conducted by Moreira et al9., the authors analyzed posture assessment applications published between 2012 and 2020, identifying a total of 13 mobile applications. These applications utilize the available features of smartphones to evaluate body alignment. Based on their functionalities, the applications were categorized into two groups: sensor-based solutions, which included eleven applications, and image-based solutions, which comprised two applications9. There is a growing body of literature indicating an increasing development of new image-based applications10,11,13,14,15. However, these applications were not assessed in the study conducted by Moreira et al., and therefore require systematic and quantitative evaluation. Addressing this gap in the literature will assist future researchers in evaluating the effectiveness and technical characteristics of these applications, as well as identifying which ones are the most valid and reliable. The goal of the present study is to identify and compare mobile phone applications that utilize images to assess postural deviations. We conducted a review of relevant digital libraries and compared various studies, taking into account important factors such as study design and the functionalities offered by the applications.

Results

Study selection

The initial literature search on the databases identified a total of 4,349 studies. After removing duplicates, 2,558 studies remained. We then resulting in 28 studies that were deemed eligible for inclusion. Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram that summarizes the selection process and shows the number of studies excluded at each stage.

Study characterization

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies, including application names, study design, sample size, sex distribution, measured variables, and key findings. A total of 29 studies, involving 1,910 participants, examined eight smartphone applications designed to assess human postural deviations using images. The applications studied included APECS, PostureScreenMobile (PSM), Fizyoprint, NLMeasurer, Biomechanics Augmented Reality Marker (BAR-M), FHPapp, CVA-CVapp, and Surgimap. Each of these mobile applications has a unique name and measurement protocol. Additionally, Table 2 presents information about the validity and reliability levels of these applications.

To further evaluate the statistical rigor of the included studies, data on power analysis and sample size estimation were extracted whenever available. Three studies12,16,17 provided clear information on the statistical power or sample size calculations for their reliability outcomes. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that several studies incorporated appropriate statistical planning to ensure adequate reliability assessment. However, the inconsistent or incomplete reporting of power analyses across the included studies reveals a methodological gap in photogrammetry-based spinal posture research and highlights the need for standardized statistical reporting in future investigations.

Quality assessment

The included studies were evaluated using the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) checklist. The results of the qualitative assessments in the validity studies revealed that six studies were of high quality1,10,11,15,16,17, while one study13 was rated as moderate quality. In terms of reliability studies, seven studies were rated as high quality1,10,11,15,16,18,19, and two studies12,17 received a moderate quality rating. Judgments regarding the risk of bias are illustrated in Fig. 2, and further details can be found in Supplementary Table 3. The assessment of item selection for participants indicated a higher number of studies categorized as high risk (27.58%). The item concerning the blinding of outcome assessment showed a significant number of studies rated as unclear risk (68.96%). The overall quality of evidence (GRADE) is presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Due to the limited number of studies included in each meta-analysis (fewer than ten per outcome), formal statistical assessments of reporting bias, such as funnel plots or Egger’s regression tests, were not performed because they would not be reliable. However, visual inspection of the available effect sizes indicated consistent directions and magnitudes across studies, suggesting a low likelihood of significant reporting bias.

Technical features of the applications

In this systematic review, APECS, PSM, Fizyoprint, NLMeasurer, BAR-M, FHPapp, CVA-CVapp, and Surgimap were the applications examined, with PSM and APECS were the most cited tools for evaluating posture. Below is a concise overview of the technical features of the applications.

APECS

The APECS (Artificial Intelligence Posture Evaluation and Correction System) app utilizes artificial intelligence to evaluate and correct a patient’s posture. APECS conducts posture evaluations using markers placed on a photo of the patient’s body, employing photogrammetric algorithms for accurate body symmetry assessment. Out of the 12 articles that utilized APECS for posture assessment, two articles5,38were excluded from the systematic review because they did not focus on evaluating the spine. In the study by Kumar et al38., participants’ working positions were recorded on video, and their postures were analyzed using the Ovako Working Posture Analysis (OWAS) through the APECS app. Additionally, Welling et al5.demonstrated that APECS is a reliable tool for measuring the hip-knee-ankle angle in lower limbs. The APECS app has been used in previous studies to evaluate postural alignment12,30,31,32, scoliosis14, lumbopelvic alignment33, and head posture36. Trovato et al12. noted that most analyzed postural variables showed high reproducibility and highlighted distinct gender-based postural differences.

PSM

PSM is a specialized application designed for healthcare professionals to assess and analyze posture and movement. The app takes pictures of subjects from various angles, including anterior (front), posterior (back), left, and right views. The application marks specific anatomical points on the individual being analyzed to calculate posture variables. It then computes the body angles based on these marked points. In the systematic analysis reviewed, the PSM app was the most cited tool for evaluating posture. 13 articles used this application to evaluate posture. The PSM app has demonstrated a strong reliability and validity for postural assessments19.

Fizyoprint

The Fizyoprint app is a mobile application designed to assess standing posture. Developed by researchers at Marmara University’s Faculty of Health Sciences, it is a free and valid tool for postural analysis. The app utilizes X, Y, and Z coordinates as reference points: the X-axis indicates direction from left to right, the Y-axis represents forward and backward, and the Z-axis indicates up and down. Fizyoprint shares a similar technological platform with PSM. This app demonstrates acceptable inter- and intra-rater reliabilities and serves as a valid tool for identifying static standing posture11.

NLMeasurer

NLMeasurer utilizes PoseNet, a computer vision model from TensorFlow, to identify 17 anatomical reference points (ARPs). This application can detect these 17 anatomical landmarks from images showing a frontal view of the human body, even if physical markers are not attached to the body. By analyzing these anatomical landmarks, the application can evaluate posture. NLMeasurer is a valid tool for evaluating posture measurements from the frontal view10. The use of surface markers on specific anatomical landmarks, such as the ears, iliac spines, and ankles, helps in the digital identification of these landmarks, thereby enhancing the reliability of postural measurements taken with the NLMeasurer10. Additionally, NLMeasurer is also utilized in anthropometric evaluations. The study by Fialho et al39.. was excluded from this systematic review because it focused on using NLMeasurer for anthropometric assessment rather than evaluating the spine.

BAR-M

The BAR-M system comprises three main components designed for clinical use13: (1) the AprilTag fiducial marker, (2) a mobile application, and (3) the BAR-M adapter. AprilTag2 is utilized as the marker for the BAR-M application. The BAR-M app is an innovative mobile application that enhances biomechanical assessments through augmented reality (AR) technology. This novel Android app tracks the orientation and 2D position of AprilTag2 in real time, utilizing smartphone capabilities to provide immediate measurements of angles and distances. These measurements are essential for evaluating posture and range of motion (ROM) during various physical activities.

FHPapp

FHPapp is a mobile application designed to assess Forward Head Posture (FHP) by measuring the craniovertebral (CV) angle. Since its launch in 2016, FHPapp aims to accurately determine cervical posture by analyzing the CV angle. Gallego-Izquierdo et al. validated the FHPapp mobile application for measuring FHP16.

CVA-CVapp

The CVA-CVapp was developed to automatically measure the craniovertebral angle using computer vision and two red markers: the first marker is placed at C7, and the second is positioned at the tragus of the ear. The primary distinction between the FHPapp and the CVA-CVapp lies in their methods of use. To measure FHP with the FHPapp, the physiotherapist takes a photo and then places three markers on the image: one at the tragus of the ear, one at the C7 vertebra, and a horizontal line parallel to the ground through these markers to determine the Cervical vertebral angle (CVA). In contrast, the CVA-CVapp streamlines this process by allowing the physiotherapist to place only two markers, one on the tragus of the ear and one at C7. After taking a photo of these markers, the application automatically calculates the CVA. The CVA-CVapp demonstrates excellent test-retest and inter-rater reliability, as well as strong concurrent validity when compared to Kinovea software for measuring CVA15.

Surgimap smartphone app

Surgimap is a digital software designed for medical professionals. It is available for free and is used to calibrate and save images. Both a smartphone application and software measure angles effectively; however, the real advantage lies in the portability of the smartphone. software requires a computer or laptop, which can limit its use in clinical settings. A study conducted by Aafreen et al17.. demonstrated that the intra-class reliability of the Surgimap mobile application for smartphones yielded excellent results, with an ICC value exceeding 0.9. This indicates that the Surgimap mobile application is a reliable measurement tool for assessing the craniovertebral angle.

Validity and reliability of Image-based app

Craniovertebral angle

Three studies investigated the validity and reliability of measuring the craniovertebral angle using image-based applications15,16,17. The meta-analysis showed moderate evidence of a significant correlation for inter-rater reliability of the craniovertebral angle, as measured by smartphone applications, which was excellent. (total n = 86; ICC = 0.889, 95% CI [0.833 to 0.927]; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001)15,16 (Fig. 3). There is moderate evidence of a significant correlation, showing that the test-retest reliability for the same angle was excellent in the two studies. (total n = 86; ICC = 0.904, 95% CI [0.854 to 0.937]; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001)15,16 (Fig. 4). Additionally, there is moderate evidence indicating that the validity of the craniovertebral angle measured by image-based smartphone applications is also excellent. (total n = 131; ICC = 0.938, 95% CI [0.852 to 0.975]; I2 = 84.82%; p < 0.001)15,16,17 (Fig. 5). The analyses demonstrated high inter-rater and test-retest reliability with no observed heterogeneity (I² = 0%), while the validity analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity (I² = 84.82%). This variability may be attributed to differences in study methodologies, such as the types of image-based smartphone applications used, the positions and protocols for measuring the craniovertebral angle, and the reference standards employed for validation. Due to the limited number of included studies, we were unable to conduct a formal sensitivity analysis—such as removing high-risk bias studies or comparing fixed versus random effects models. Nonetheless, the consistency in the direction and magnitude of effect sizes across the reliability analyses, with all ICCs above 0.85, indicates that the synthesized results are robust. Additionally, the I² values of 0% in the reliability syntheses demonstrate low variability between studies, further supporting the stability of the findings.

Head Tilt

Four studies examine the reliability1,11,18,19 of head tilt in the lateral view of image-based applications. The meta-analysis showed moderate evidence of a significant correlation in the inter-rater reliability of head tilt measurements taken using image-based smartphone applications, which demonstrated excellent reliability. (total n = 50; ICC = 0.962, 95% CI [0.898 to 0.986]; I2 = 60.60%; p < 0.001)11,18,19 (Fig. 6). Additionally, there is moderate evidence of a significant correlation in the test-retest reliability of head tilt measurements using these applications, which also showed excellent reliability. (total n = 100; ICC = 0.898, 95% CI [0.381 to 0.987]; I2 = 95.37%; p = 0.007)1,11,18,19 (Fig. 7). Moderate heterogeneity was observed in the inter-rater reliability analysis (I² = 60.60%), while substantial heterogeneity was found in the test-retest reliability analysis (I² = 95.37%). Potential sources of this heterogeneity may include variations in study designs, the characteristics of sample populations, and the types of smartphone applications used across different studies. Due to the limited number of studies available, formal sensitivity analyses—such as excluding studies with a high risk of bias or those with outlier results—could not be performed robustly.

Acromion alignment

Six studies investigate the reliability1,10,11,12,18,19, and two studies assess the validity10,11 of acromion alignment in the anterior view of image-based applications. The meta-analysis indicated moderate evidence of a significant correlation in the inter-rater reliability of acromion alignment measured by image-based smartphone applications, which was excellent. (total n = 170; ICC = 0.904, 95% CI [0.834 to 0.946]; I2 = 56.91%; p < 0.001)10,11,12,18,19 (Fig. 8). There is moderate evidence of a significant correlation in the test-retest reliability of acromion alignment measured by these applications, which was good. (total n = 120; ICC = 0.771, 95% CI [0.551 to 0.891]; I2 = 73.83%; p < 0.001)1,10,11,18,19 (Fig. 9). Additionally, the validity of acromion alignment measured by image-based smartphone applications showed moderate evidence of a significant correlation, with findings moderate. (total n = 40; ICC = 0.603, 95% CI [0.347 to 0.776]; I2 = 0.00%; p < 0.001)10,11 (Fig. 10). Moderate heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis of inter-rater reliability (I² = 56.91%), while substantial heterogeneity was found in the test-retest reliability analysis (I² = 73.83%). Due to the limited number of available studies, formal sensitivity analyses—such as excluding studies with a high risk of bias or those with outlier results—could not be conducted robustly.

Hip Tilt

Six studies examine the reliability1,10,11,12,18,19 and two studies evaluate the validity10,11 of hip tilt in the anterior view of image-based applications. The meta-analysis showed moderate evidence of a significant correlation in the inter-rater reliability of hip tilt measured by image-based smartphone applications, which was good. (total n = 170; ICC = 0.842, 95% CI [0.585 to 0.945]; I2 = 88.37%; p < 0.001)10,11,12,18,19 (Fig. 11). There is strong evidence of a significant correlation in the test-retest reliability of hip tilt measurements, which was moderate. (total n = 120; ICC = 0.642, 95% CI [0.466 to 0.768]; I2 = 36.24%; p < 0.001)1,10,11,18,19 (Fig. 12). Finally, moderate evidence suggests a significant correlation in the validity of hip tilt measured by image-based smartphone applications, with findings moderate. (total n = 40; ICC = 0.462, 95% CI [−0.515 to 0.917]; I2 = 90.12%; p = 0.360)10,11 (Fig. 13). Significant heterogeneity was observed in the inter-rater reliability analysis (I² = 88.37%) and the validity analysis (I² = 90.12%). These inconsistencies may stem from methodological differences across studies, including variations in measurement protocols, sample characteristics, rater experience, and the specific smartphone applications or algorithms used. In contrast, the test-retest reliability analysis showed low to moderate heterogeneity (I² = 36.24%), indicating relatively better consistency in repeated measures across studies. Sensitivity analyses were limited due to the small number of studies for each outcome. However, an examination of the forest plots revealed that the direction of effects for test-retest reliability was relatively consistent, supporting the robustness of the findings despite some variation. Conversely, for inter-rater reliability and validity, the wide confidence intervals and high I² values suggest that the results may be sensitive to study-specific factors, indicating less robustness and greater variability in those findings.

Discussion

The primary aim of this review was to evaluate the validity and reliability of angles measured using image-based smartphone applications. We intended to synthesize the findings and offer valuable recommendations based on existing literature. In this meta-analysis, we evaluated the validity of measuring angles with smartphone applications by comparing their results to standard reference measures, including VICON 3D motion analyzers and Kinovea software. Twenty-nine studies were included, examining over ten different outcomes in this review; however, we were able to conduct meta-analysis for only four specific angles. The evidence indicated good to excellent validity and reliability for the craniovertebral angle, acromion alignment, and measurements of head and hip tilt. Given that the results of this study showed that the measurements from these applications are valid and require less time for evaluations, mobile apps can be an effective tool for tracking spinal deviations and body angles. The increasing need to assess and monitor individuals’ posture has prompted sports professionals to adopt methods and techniques that enhance the evaluation process while ensuring validity and reliability. As a result, mobile applications designed for this purpose have gained popularity in both the sports and scientific communities. An analysis of publication years for relevant articles shows that most were published within the last three years (Fig. 14), indicating a current trend among health professionals and researchers toward seeking quicker, more practical, and reliable methods for assessing postural deviations. The studies included in this review utilized statistical tests to compare smartphone applications with traditional measurement techniques.

Craniovertebral angle

Three apps, FHPapp, CVA-Cvapp, and Surgimap, measured the craniovertebral angle and reported on their validity and reliability. The results of the meta-analysis indicated that both inter-rater and test-retest reliability were excellent for CVA-Cvapp and FHPapp, and validity was demonstrated to be excellent for all three apps. The CVA-CVapp, is designed to assess head position, particularly the CV angle, using computer vision technology. The FHPapp and CVA-CVapp both use mobile technology to measure cervical posture, but they employ different methodologies. With FHPapp, the physiotherapist captures a photo and places three markers on the image. The app then calculates the cervical vector (CV) angle by subtracting the measured angle from 360°. This app has demonstrated high intra- and inter-rater reliability, with ICCs ranging from 0.82 to 0.88. It also exhibits a sensitivity of 94.4% and a specificity of 84.6% for detecting FHP, indicating that it is a valid tool for clinical use16. In contrast, CVA-CVapp utilizes advanced computer vision techniques to analyze head posture from images, potentially providing more precise measurements compared to traditional methods. This smartphone app has demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and strong concurrent validity when compared to Kinovea software for measuring the CVA15.

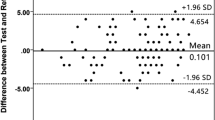

Head Tilt

Two applications, Fizyoprint and PSM, were utilized to evaluate head tilt in the lateral view. However, there was insufficient data to conduct a meta-analysis regarding head tilt in this perspective. The analysis indicated that both inter-rater reliability and test-retest reliability were excellent for the two applications, Fizyoprint and PSM. The validity1,19 and reliability1,18,19 of the PSM app have been investigated. In a comparison between PostureScreen (PSM) and Vicon, findings from Hopkins et al.1. indicated that PSM measurements demonstrated similar reliability for 6 out of 10 postural assessments. However, there was bias in postural measurements for 8 out of 10 assessments, and lower ICC values were observed in 3 out of 10 assessments when using the PSM app. These findings suggest that the use of photographs and touchscreen technology may introduce some inherent errors. One potential source of error could be the difficulty in accurately identifying anatomical landmarks, as well as the size of the finger used on the touchscreen1.

Acromion alignment and hip Tilt

Four apps, NLMeasauer, PSM, Fizyoprint, and APECS, reported validity and reliability for acromion alignment and hip tilt. The results of the meta-analysis revealed that inter-rater and test-retest reliability were good to excellent for all four apps, while validity was moderate for NLMeasauer and Fizyoprint. These results indicate that both intra- and inter-rater angular measurements were consistent and reproducible when compared to other methods.

Mobile applications for assessing human posture offer several advantages over traditional methods such as visual inspection and palpation. Research has shown that these mobile apps are reliable and valid for posture assessment, often demonstrating good to excellent agreement with traditional methods like goniometers, inclinometers, and electromagnetic tracking system9. Some mobile applications utilize computer vision and machine learning algorithms to automate the posture assessment process10,15. For instance, the NLMeasurer, a computer vision-based mobile tool, has been found to be in agreement with validated biophotogrammetry software and has demonstrated good inter-rater and intra-rater reliability10.

APECS, Fizyoprint, and PSM are photogrammetry-based tools used to assess body posture. APECS uses the Anterior Trunk Symmetry Index (ATSI) and Posterior Trunk Symmetry Index (POTSI) to measure asymmetry between the left and right sides of the body. These indices offer a quick and straightforward method for screening individuals with scoliosis40. Information and Communications Technology-based management of scoliosis involves two main approaches41: (i) standalone software tools or web applications; and (ii) smartphone applications, commonly referred to as apps. Mobile applications can be classified into two categories: sensor-based solutions and image-based solutions9. Measurements obtained from image-based systems can be affected by various factors, including camera resolution and lighting conditions, which may lead to inaccuracies. To address the limitations of these systems, electronic sensors such as accelerometers and gyroscopes are often used in applications. Several apps are available for assessing scoliosis41, including ScolioTrack, Scoliometer, CobbMeter, Scoliosis Tracker, and ScolioDetector. These apps utilize sensors to evaluate scoliosis. However, sensor-based applications have encountered issues, including disturbances caused by trunk movement and gyroscope drift. The PhysioCode Posture (PCP) is an Android application that integrates camera functionality with an inertial sensor42. It offers features such as the amplification of analyzed points through touch interaction with the image. This technological tool, known as sensory magnification in engineering, enhances the precision of virtual marker positioning, thereby optimizing postural assessments in clinical settings. The PCP has shown excellent intra- and inter-rater reliability, as well as excellent agreement with the Kinovea software42.

The APECS app has been referenced in articles on postural alignment12,30,31,32, scoliosis14, lumbopelvic alignment33, and head posture36 from 2022 to 2024. It is available for download on the Google Play Store. The APECS application has demonstrated a high percentage of matching (98.74%) and agreement (94.64%) with the gold standard (X-ray), indicating excellent validity in measuring the hip-knee-ankle angle5. This validation study aimed to assess the hip-knee-ankle angle in the lower body5. The structure and function of the joints in the lower body can affect the spine; for instance, an ankle injury can alter the functioning of trunk muscles43. However, the validity of the APECS application for spinal assessment was not reviewed. To effectively use the APECS application in articles, it is essential to assess its validity and reliability for various evaluations. A measurement is considered reliable when it employs accurate, valid, and reliable tools and methods. Therefore, it is important to investigate the validity and reliability of the APECS application in future research. Only the study conducted by Trovato et al.12 noted that most of the postural variables analyzed with this application demonstrated high reproducibility. Two studies33,34 investigated the correlation between APECS and Spinal Mouse for assessing sagittal imbalance and lumbopelvic alignment in adolescents with thoracic kyphosis. The results indicated a moderate to good correlation for standing and flexion positions between some measurements taken with both devices.

Posture assessment apps utilize a range of technologies, including photogrammetry, inertial sensors, and augmented reality, to deliver precise evaluations of body posture. For instance, marker-based systems monitor the movement of markers affixed to a person’s body, employing either active, magnetic, or passive markers. The BAR-M application is designed to detect, track, and calculate anatomical angles between key landmarks in real-time. Fiducial marker systems are defined as recognizable objects within the field of view of an optical imaging device and can be dynamically detected through specialized software13. The BAR-M application utilizes AprilTag2 as the marker, tracking its orientation and 2D position in real time13. Compared to Vicon, the BAR-M application accurately tracked and displayed angles based on evaluations conducted with a Body Opponent Bag, where clothing and participant movement did not affect anthropometric measurements. Evaluations involving humans also showed viability for posture, body symmetry, and range of motion assessment, although the results were not as good as those from the BOB analyses13. Clothing movement errors are well known in marker-based systems. To improve accuracy and compensate for errors caused by clothing movement and other factors, enhancements are needed. Using a suitable strap along with the AprilTag marker can help minimize errors caused by clothing movement, as well as secure the marker to the person13.

The results of this study indicated that image-based applications have made significant advancements in recent years. The findings from this comprehensive review and meta-analysis highlight the growing body of literature in this field. According to a review by Moreira et al9. in 2020, out of 13 applications designed for assessing human body posture, only one—PSM—utilized image-based technology, while the other 11 relied on sensors. This systematic review and meta-analysis found that each image-based application has distinct goals and algorithms, leading to both similarities and differences among them. However, research concerning the validity and reliability of these applications remains limited. Future studies should focus on evaluating their validity and reliability in specific populations, ideally with larger sample sizes. Previous Studies examining the validity and reliability of mobile apps have revealed certain limitations that could be misleading. Synthesizing these findings is challenging due to the lack of standardized protocols and the small sample sizes involved. This review has limitations, including its restriction to English-language articles and the search conducted across only six well-established digital libraries. Consequently, our conclusions are limited by the published literature that is available to us. Many studies lacked essential measurement-error indices (e.g., SEM, MAD), and because standard deviations and reliability coefficients were inconsistently reported, we chose not to estimate them to avoid bias. Notably, the absence of these precision metrics prevents the determination of the MCID, which is a significant barrier to applying these findings in everyday clinical practice. Other limitations include significant variability in interventions and outcome measures, inconsistent measurement protocols, small sample sizes, and incomplete reporting. These issues underscore the need for more standardized and rigorous reporting in future research.

Conclusion

This systematic review examined eight image-based apps for posture assessment, each with distinct goals and algorithms, resulting in both similarities and differences among them. Among these apps, three—Surgimap, CVA-Cvapp, and FHPapp—assess the craniovertebral angle, report on their validity and reliability, and were therefore included in the meta-analysis. Although PSM is also capable of measuring this angle, it was excluded from the meta-analysis due to methodological discrepancies in the relevant studies. The Fizyoprint, PSM, and APECS apps assess the subject’s posture using markers placed on the patient’s body image, employing photogrammetric algorithms to evaluate body symmetry accurately. In contrast, the NLMeasurer and CVA-Cvapp use computer vision models for their assessments, and the BAR-M app utilizes augmented reality (AR) technology for its evaluations. Although PSM includes features that may be categorized as AR, such as live anatomical point overlays and real-time alignment guidance, these aspects were not evaluated in the studies included in our review and, therefore, were not specifically analyzed. Overall, research on the validity and reliability of these applications is still limited. In conclusion, image-based applications are a viable, cost-effective tool for postural screening, but their current limitations require greater methodological rigor before they can be used reliably to track clinically significant changes over time.

Research methodology

This Systematic Review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines44. We successfully registered the protocol with the International Platform for Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols, assigned the number CRD42024573433. No amendments were made to the registered protocol during this review.

Research questions

In order to achieve the goal of this systematic review, we have considered the following research questions: (1) What mobile apps have been used for analyzing the human posture through spine alignment? (2) What are the technical features of mobile applications for assessing human spine alignment? (3) What are the outcomes in terms of performance achieved by the mobile applications?

Search strategy

We conducted a thorough search across six prominent electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, the ACM Digital Library, Embase, and Google Scholar. This comprehensive review aimed to collect studies from the inception of these databases up to September 7, 2024, ensuring a rich collection of relevant research. The search was conducted through the PICO framework: Participants—individuals, both with and without postural alterations; Intervention—a mobile application dedicated to postural assessment; Comparison—evaluating mobile applications alongside traditional methods for postural assessment; Outcomes—Spinal alignment values for angulations and translations. The key terms in our search strategy were thoughtfully selected from broad categories and relevant synonyms:

#1 “Static standing posture” OR “Postur* Analysis” OR “Postur* Assessment” OR “Postur* evaluation” OR Scoliosis OR Lordosis OR Kyphosis OR “postur* alignment” OR “upper cross” OR “posture screening” OR Spin* OR Craniovertebral OR Craniocervical OR “Scapular dyskinesis” OR “Forward head” OR Torticollis OR “Sway back”.

#2 “Mobile System” OR “Mobile phone” OR “Mobile devices” OR “Mobile Application” OR “smartphone application” OR “Mobile App” OR “smartphone app” OR Iphone.

#1 AND #2.

Reference lists from earlier systematic reviews on Mobile Applications for Assessing Human Posture searched to guarantee that all pertinent studies.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) be written in English; (2) be published between 2010 and 2024; (3) focus on the development, testing, validation, evaluation, or comparison of mobile applications that assess human posture based on coronal and sagittal alignment. We excluded studies that: (1) only analyzed specific body segments like arms and legs without considering spinal posture; (2) focused solely on variations in body position related to balance; (3) papers with text unavailable in full; (4) relied exclusively on mobile applications designed for wearable devices or used X-ray or three-dimensional computed tomography scans to analyze spinal radiography images and applications employed by the sensors.

Study selection

Two researchers independently screened the papers using a search string on digital libraries. They then removed any duplicate papers and applied selection criteria based on analyzing the titles and abstracts of the remaining papers. To ensure agreement, Cohen’s kappa45 was calculated. Any disagreements between the two reviewers, M.K. and S.H.M., were first discussed between them to reach a consensus. If they were unable to achieve consensus, a third reviewer, R.R., was consulted to help resolve the disagreement. The final decision was based on the majority agreement among the three reviewers. After this process, all selected papers were read in full by the two primary reviewers, M.K. and S.H.M., independently to assess study quality and extract relevant data. In cases of uncertainty or ambiguity during data extraction, the third reviewer, R.R., was consulted for verification and consensus.

Data extraction

One author (M.K.) extracted all relevant data from the included studies. To reduce potential bias or inaccuracies in the data collection process, all data was verified by (S.H.M.). The data extraction process involved using a predefined form that included various details from each study. The primary outcome measures focused on the performance of mobile applications for posture assessment, specifically their validity and reliability. The posture parameters extracted included the Craniovertebral Angle, Head Tilt, Acromion Alignment, and Hip Tilt. Comprehensive data were gathered for all results aligned with these outcome domains, including all reported measures (e.g., correlation coefficients for inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability, and validity) across all time points. Additional variables extracted, as specified in the predefined form, included the following details: (1) Study Identification: The author and year of the study. (2) Intervention Characteristics: The name of the application, the study design (based on Wieringa et al46.), categorization based on the type of technical feature (e.g., photogrammetry, computer vision models, augmented reality), and availability in application stores (3) Participant Characteristics: Information on the sample size and gender of participants. (4) Evaluation Metrics: Metrics used for evaluating and validating mobile applications, key findings, and quality assessments. (5) Funding Sources: Information regarding funding sources. Data were recorded exactly as reported in the original studies; no assumptions were made, and no data imputations were performed for missing information. In cases of uncertainty or ambiguity during data extraction, the third reviewer (R.R.) was consulted for verification and consensus.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the COSMIN checklist. Specifically, forms H and B from the COSMIN checklist were used to assess the validity and reliability of the studies47. The quality assessments were based on a 4-point scale (i.e., excellent, good, fair, poor) for each item on the checklist. For validity, studies were classified as having high quality (total score of 14–18), moderate quality (total score of 8–13), or low quality (total score of 3–7). Similarly, for reliability, studies were categorized as high quality (total score of 25–33), moderate quality (total score of 14–24), or low quality (total score of 3–13). The COSMIN checklist used for these evaluations is available in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The risk of bias in results or inferences was assessed using the RoBANS tool48. Each study was analyzed individually and rated as having a low, high, or unclear risk of bias across several domains: selection of participants, confounding variables, measurement of exposure, blinding of outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. The quality assessment was performed independently by two authors (M.K. and S.H.M.). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. In cases of uncertainty, the third author (R.R.) was consulted.

Synthesis of results

Correlation coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random effects model in MedCalc Statistical Software version 23.1.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org). The primary effect measure used in each quantitative synthesis was the ICC with 95% CIs, which represent the strength of agreement or reliability between measures. When multiple studies assessed the same outcome using comparable methodologies, effect sizes were combined using a random-effects model to account for potential heterogeneity. Results were visualized using forest plots generated in MedCalc Statistical Software. Before synthesis, extracted data were verified for completeness and consistency. When summary statistics such as standard errors or confidence intervals were not directly reported, they were calculated from available data using standard meta-analytic formulas. No conversions between different effect size metrics were required, and no imputation of missing data was performed. Possible causes of heterogeneity among study results were planned to be explored through subgroup analyses or meta-regression, if sufficient numbers of studies were available. However, because fewer than ten studies were included for each outcome and study designs were heterogeneous, these analyses could not be meaningfully performed. Instead, heterogeneity was interpreted qualitatively based on variations in sample characteristics, methodological quality, and measurement protocols across studies. A meta-analysis was performed when at least two studies examined the same outcome measure using similar methodologies. The results of studies and meta-analyses were summarized in structured tables and forest plots. Forest plots were created using MedCalc software to visualize effect sizes and confidence intervals. The level of statistical heterogeneity for the pooled data was quantified using I² statistics and associated P-values (P < 0.05). Results were presented according to levels of evidence as defined by van Tulder et al.49and modified by Mousavi et al50., as shown in Supplementary Table 5. Since fewer than ten studies were included for each outcome, it was not possible to conduct a formal statistical assessment of reporting bias, such as funnel plots or Egger’s test. Additionally, the limited number of available studies meant that we could not conduct formal sensitivity analyses, such as excluding studies with a high risk of bias or those with outlier results. The certainty of the evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) approach51. Heterogeneity was quantified using I² and categorized as low (I² < 25%), moderate (I² 25%–50%), high (I² 50%–75%), or extreme (I² > 75%).

Precision and clinical relevance metrics

To provide a comprehensive assessment of measurement precision and clinical relevance, we extracted or calculated the SEM and the MDC for each outcome. The SEM was obtained directly from the primary studies when available (Table 2). When studies reported the ICC and Standard Deviation (SD), we calculated the SEM using the formula: SEM = SD × √(1 – ICC). Next, we calculated the MDC using the following formula: MDC = 1.96 × SEM × √2. While the MDC is essential for determining the smallest detectable change that goes beyond measurement error, the Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) was not reported in any of the included studies, preventing its inclusion in the quantitative analysis. Additionally, we extracted data on Power Analysis from individual studies that reported it to assess their statistical rigor.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The template data collection forms and extracted data from included studies can also be provided upon request. No custom analytic code was created beyond the standard procedures and functions available within MedCalc Statistical Software.

References

Hopkins, B. B. et al. Validity and reliability of standing posture measurements using a mobile application. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 42, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2019.02.003 (2019).

Fortin, C., Ehrmann Feldman, D., Cheriet, F. & Labelle, H. Clinical methods for quantifying body segment posture: a literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33, 367–383 (2011).

Sprigle, S., Wootten, M., Bresler, M. & Flinn, N. J. A. o. p. m. & rehabilitation. Development of a noninvasive measure of pelvic and hip angles in seated posture. 83, 1597–1602 (2002).

Mylonas, K., Tsekoura, M., Billis, E., Aggelopoulos, P., Tsepis, E. & Fousekis, K. Reliability and validity of non-radiographic methods of forward head posture measurement: a systematic review. Cureus, 14, e27696 (2022).

Welling, A., Gurudut, P., Shirodkar, G., Shetye, N. & Khan, S. J. Validation of non-radiographic APECS software in comparison with standard radiographic measurement of full-length lower limb hip-knee-ankle angle in elderly obese women. P Q. 31, 90–94 (2023).

Dhumale, A., Shinde, S., Ambali, M. P. & Patil, P. Integration of artificial intelligence for diagnostic methods in musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. Cureus, 17, e79391 (2025).

Istepanian, R., Laxminarayan, S. & Pattichis, C. S. M-health: Emerging mobile health systems (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

Saponara, S., Donati, M., Fanucci, L. & Celli, A. An embedded sensing and communication platform, and a healthcare model for remote monitoring of chronic diseases. Electronics 5, 47 (2016).

Moreira, R. et al. Mobile applications for assessing human posture: a systematic literature review. Electronics 9, 1196 (2020).

Moreira, R. et al. A computer vision-based mobile tool for assessing human posture: A validation study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106565 (2022).

Timurtaş, E. et al. A mobile application tool for standing posture analysis: development, validity, and reliability. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 191, 2123–2131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02827-5 (2022).

Trovato, B. et al. Postural evaluation in young healthy adults through a digital and reproducible method. J. Funct. MORPHOLOGY Kinesiol. 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk7040098 (2022).

Basiratzadeh, S., Lemaire, E. D. & Baddour, N. A novel augmented reality mobile-based application for biomechanical measurement. BioMed, 2, 255–269 (2022).

Belli, G., Toselli, S., Latessa, P. M. & Mauro, M. J. E. J. o. I. i. H., Psychology & Education. Evaluation of self-perceived body image in adolescents with mild idiopathic scoliosis. 12, 319–333 (2022).

Carrasco-Uribarren, A. et al. A Computer Vision-Based Application for the Assessment of Head Posture: A Validation and Reliability Study. Appl. SCIENCES-BASEL 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063910 (2023).

Gallego-Izquierdo, T. et al. Psychometric Proprieties of a Mobile Application to Measure the Craniovertebral Angle a Validation and Reliability Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186521 (2020).

Aafreen et al. Clinimetric properties of a smartphone application to measure the craniovertebral angle in different age groups and positions. Heliyon 9, e19336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19336 (2023).

Boland, D. M., Neufeld, E. V., Ruddell, J., Dolezal, B. A. & Cooper, C. B. Inter- and intra-rater agreement of static posture analysis using a mobile application. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 28, 3398–3402. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.28.3398 (2016).

Szucs, K. A. & Brown, E. V. D. Rater reliability and construct validity of a mobile application for posture analysis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 30, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.30.31 (2018).

Szucs, K. A., Cicuto, K. & Rakow, M. A comparison of upper body and limb postures across technology and handheld device use in college students. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 30, 1293–1300. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.30.1293 (2018).

Iacob, S. M. et al. Is PostureScreen® mobile app an accurate tool for dentists to evaluate the correlation between malocclusion and posture? Cranio: J. Craniomandib. Pract. 38, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/08869634.2018.1512197 (2020).

Turhal, C., Soyupek, F. & Baykal, T. J. J. o. C. M. Posture analysis and presence of sacroiliac joint dysfunction in patients with chronic lower extremity edema. J. Contemp. Med. 13, 294–300 (2023).

Apostolia, D., Hristara-Papadopoulou, A., Kallistratos, I. et al. Screening for asymmetries in upright posture using the posture screen mobile application in adolescence: potential factors of postural disorder and asymmetries. Int Res J Public Environ Health, 7, 105–110 (2020).

Babydov, E. et al. Strength training and posture alighment. J. IMAB–Annual Proceeding Sci. Papers. 29, 4974–4979 (2023).

Tariq, I., Riaz, H., Anwar, M. & Ahmed, A. J. P. B. J. Correlation between forward head posture and neck pain in IT professionals by using postural screen mobile app: forward head posture and neck pain in IT professionals. Pakistan BioMedical Journal, 5, 190–194 (2022).

Santos, J. G. L. et al. Body postural realignment in the first 2 months after orthognathic surgery. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 159, e281–e290 (2021).

Al-Rawi, N. H. et al. Vertebral malalignment among male dentists with Work-related musculoskeletal pain in the united Arab Emirates. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 19, 773–777 (2018).

Mariyam Farzana, S. F. & Pooja Analysis of posture using posture screening mobile application among collegiates. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 15, 597–602. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijfmt.v15i1.13472 (2021).

Emir, A., Tarakci, D., Atilgan, E. & Tarakci, E. Comparing body posture and postural control in children with intellectual disability and dyslexia to typically developing children using technology-based assessments. Int. J. Therapy Rehabilitation 30, https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2022.0007 (2023).

Cengiz, Ş. Ş. & Delen, B. Postural analysis of adolescent young athletes in different sports branches. Journal of Human Sciences, 21, 292–300 (2024).

Çankaya, M., Takı, F. N. & J. I. J. o. O. S. & Ergonomics. Comparison of postural assessment and awareness in individuals receiving posture training using the digital AI posture assessment and correction system. 1–7 (2024).

Akbulut, A. S. The Effect of TMJ Intervention on Instant Postural Changes and Dystonic Contractions in Patients Diagnosed with Dystonia: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13203177 (2023).

Belli, G., Russo, L., Mauro, M. & Toselli, S. & Maietta Latessa, P. in Healthcare. 738 (MDPI).

Belli, G., Toselli, S., Mauro, M., Maietta Latessa, P. & Russo, L. Relation between photogrammetry and spinal mouse for sagittal imbalance assessment in adolescents with thoracic kyphosis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 8, 68 (2023).

Badau, A., Badau, D., Cengiz, S. S. & Coşkun, E. Ş. J. L. The Relationship between Sleep Quality and Posture: A Study on University Students. 14, 1244 (2024).

Nehru, A., Muthukumaran, J. & J. I. J. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the active correction exercises in forward head posture in young adults. (2023). (2023).

Irfan, U., Asif, S., Mumtaz, M., Jamal, S., Khalid, F., Fatima, K., Nawaz, I., Sheikh, N., Rafique, H. & Aslam, I. Prevalence of poor body posture among physiotherapists using APECS. Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Research, 4, 1323–1327 (2024).

Kumar, G. P. & Thangavelu, R. B. J. W. Postural analysis and ergonomic intervention of unorganized workers in indian construction sectors. 1–12.

Fialho, R. et al. in 2021 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS). 119–124 (IEEE).

Asher, M., Lai, S. M., Burton, D. & Manna, B. Discrimination validity of the scoliosis research society-22 patient questionnaire: relationship to idiopathic scoliosis curve pattern and curve size. Spine 28, 74–77 (2003).

Bottino, L., Settino, M., Promenzio, L. & Cannataro, M. J. I. J. o. E. R. & Health, P. Scoliosis management through apps and software tools. 20, 5520 (2023).

Sabino, G. S., de Souza, L. A., Ribeiro, T., Nascimento, D. H., Vimieiro, C. B. & Resende, R. A. Validity and reliability of a smartphone application for knee posture quantification and the effects of external markers on the precision of this measure. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 28, 42–48 (2021).

Karbalaeimahdi, M., Alizadeh, M. H., Minoonejad, H., Behm, D. G. & Alizadeh, S. Higher leg and trunk muscle activation during balance control in copers versus people with chronic ankle instability and healthy female athletes. Sports, 10(8), 111 (2022).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. PRISMA Group*, t. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269 (2009).

Cohen, J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 70, 213 (1968).

Wieringa, R., Maiden, N., Mead, N. & Rolland, C. Requirements engineering paper classification and evaluation criteria: a proposal and a discussion. Requirements Eng. 11, 102–107 (2006).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Medical Research Methodology 10, 1–8 (2010).

Kim, S. Y., Park, J. E., Lee, Y. J., Seo, H. J., Sheen, S. S., Hahn, S., Jang, B. H. & Son, H. J. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66, 408–414 (2013).

Furlan, A. D., Pennick, V., Bombardier, C. & van Tulder, M. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane back review group. Spine 34, 1929–1941 (2009).

Mousavi, S. H. et al. Kinematic risk factors for lower limb tendinopathy in distance runners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 69, 13–24 (2019).

Guyatt, G. et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings Tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64, 383–394 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This paper is a section of the Mina Karbalaeimahdi’s PhD dissertation from Department of Health and Sports Medicine Department, Faculty of Sport Sciences and Health, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, identified as number 71916433.

Funding

The authors have not received any specific grants for this research from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.: conducted the search, review, data extraction, and meta-analysis, and was responsible for the main writing of the manuscript. S.H.M.: assisted with the search, quality appraisal of the included papers, and data extraction. R.R. and H.M.: supervision, reviewing the article. All authors contributed to drafting the article and critically revising it for essential intellectual content. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karbalaeimahdi, M., Minoonejad, H., Mousavi, S.H. et al. Photogrammetry-based smartphone applications for spinal posture assessment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 16, 2885 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32708-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32708-1