Abstract

The brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stal is a key pest of rice in Asia, causing extensive crop losses and transmitting major viruses. We analysed mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (mtCOI) sequences from 63 field-collected samples representing 21 populations across ten states to understand its genetic structure across India’s diverse agroclimatic zones. Our analysis revealed two highly conserved haplotypes, with one major haplotype shared across over 85% of individuals. This consistent haplotype distribution is supported by a TCS network and minimal mutational steps and this reflects strong genetic cohesion across geographically distant populations. Population genetic parameters, neutrality tests, and mismatch distribution patterns support a recent demographic expansion of N. lugens in India. A majority of genetic variation was observed within populations, with only subtle regional differences, as confirmed by AMOVA and phylogenetic tree topology. These results indicate robust gene flow and suggest that Indian populations are highly interconnected, likely facilitated by seasonal migration and shared agricultural practices. Our study offers one of the most comprehensive mitochondrial diversity assessment of Indian N. lugens to date and provides critical genetic benchmarks for future monitoring, resistance management, and predictive modelling of BPH outbreaks in the subcontinent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a fundamental food crop cultivated in approximately 118 countries, with Asia accounting for the majority of its cultivation and production1. As a staple food for over half the global population, rice plays a central role in food security and rural livelihoods, contributing over 20% of the world’s dietary calorie intake2. With increasing pressure from biotic and abiotic stresses, sustaining rice productivity has become a critical global challenge. Insect pests, especially stem borers, leaf-feeding defoliators, and sap-sucking hoppers, are major threats to rice production.

The brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens Stal is one of the most destructive pests of rice, posing both direct and indirect threats to crop yield. This phloem feeding hemipteran, results in “hopperburn” or wilting and eventually plant death. In addition, this monophagous pest transmits important rice viruses such as rice ragged stunt virus (RRSV) and rice grassy stunt virus (RGSV), leading to significant yield losses3,4,5.

Outbreaks of BPH have become increasingly frequent in Asia, with major incidents reported in Indonesia, India, Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand6,7,8. These outbreaks were largely linked to intensified rice cultivation during the Green Revolution of the 1970 s and 1980s9. While the widespread adoption of resistant rice varieties initially helped manage BPH, repeated and large-scale deployment of such varieties led to the rapid selection of virulent BPH populations that overcame resistance within just 10 to 20 generations9,10,11.

These outbreaks were accompanied by the emergence of BPH biotypes. Biotypic variation in BPH is driven by the evolutionary “arms race” between the pest and its host plant. The term “biotype” refers to genetically distinct populations capable of overcoming specific resistance genes in rice. According to Horgan (2024)10, a BPH biotype reflects changes in the frequency of virulence alleles within a population, often arising from local selection and sympatric speciation. Early work by Khush (1987)12 introduced a biotyping scheme based on planthopper performance on different rice lines. Five major biotypes were originally recognized: Biotype 1 feeds on susceptible rice variety TNh1 (no resistance genes), Biotype 2 overcomes BPH1 in Mudgo, Biotype 3 defeats BPH2 in ASD7, Biotype 4 feeds on Rathu Heenati carrying BPH3, and Biotype 5 is virulent on Babawee with BPH412,13. In India, Biotype 4 is currently dominant, showing virulence toward varieties like Ptb33 and ARC1055014. In Indonesia, Biotype Y was recently detected in Bali for the first time8. Similarly, in Thailand, highly virulent new biotypes, designated Biotype 5(t), 6(t), and 7(t) have been documented15.

Accurate and timely identification of N. lugens remains a critical challenge for effective pest management. Morphological identification relies on anatomical traits such as wing shape, head structure, and genitalia16. However, this requires expert knowledge and it is prone to human error, and only practical for small, well-preserved sample sets. Molecular tools provide a faster, more accurate, and scalable alternative for large-scale surveillance, pest diagnostics, and biotype tracking.

Several molecular markers have been employed to study BPH population structure and biotypic divergence, including mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (mtCOI), simple sequence repeats (SSR), sequence-related amplified polymorphisms (SRAP), and EST-SSRs14,17,18. DNA marker analysis has also been widely used in other insect species to assess whether divergence is linked to geographic isolation or host plant adaptation5. While early studies using RAPD markers showed limited power in distinguishing biotypes19, later studies achieved partial discrimination of biotypes 1 and 220. More recent work using EST-SSR markers successfully differentiated four BPH biotypes17. SRAP markers, which target gene-rich regions and their flanking sequences, provide functional insights into host adaptation and biotype evolution21.

Among various molecular markers, the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) gene is widely used in evolutionary studies due to its unique genetic properties7,22,23. It is highly conserved within species while exhibiting sufficient variation between species, making it useful for both intraspecific and interspecific analysis. Its universality across taxa makes it especially valuable when other markers are absent or unreliable24. The MtCOI-based analyses have revealed distinct haplotypes and migration routes in BPH populations across Southeast Asia, including the Philippines and Indonesia8,25.

Mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited, non-recombining, and evolves relatively rapidly, making it a reliable marker for population genetic studies in insects26,27. The COI gene, in particular, shows high variation at silent sites while retaining protein-level conservation, enabling analysis of species boundaries, population structure, and evolutionary relationships26,28,29.

Previous studies have reported the genetic diversity of N. lugens in countries such as China, South Korea, Pakistan, India, and Malaysia17,30,31. Despite these studies, information on the spatial genetic structure of N. lugens within India remains limited and fragmented. Most previous reports have focused on specific regions or included few samples, offering only a partial picture of genetic variation across the country. In addition, comparative information linking Indian populations with other Asian lineages is still lacking, leaving gaps in our understanding of gene flow and the possible occurrence of unique local haplotypes. The present study was therefore designed to provide a broader view of the genetic diversity and population relationships of N. lugens in India using mtCOI sequences collected from major rice-growing states. By analyzing samples from diverse agroclimatic zones, we aimed to assess the extent of genetic variation among Indian populations and to determine whether any regional patterns or distinct haplotypes could be observed across the subcontinent. In the present study, we investigated intraspecific variation in Indian BPH populations using mtCOI gene sequences. Samples were collected from 21 locations, each with three replicates, spanning ten rice-growing states: Haryana, Punjab, Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Kerala. This extensive sampling across varied agroclimatic zones provides insights into the spatial genetic structure of BPH in India. The study aimed to determine whether Indian N. lugens populations exhibit regional genetic differentiation or constitute a genetically homogeneous population across the subcontinent.

Results

Sample Collection; molecular characterization and sequence deposition in NCBI

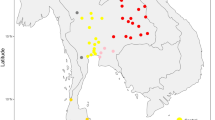

A total of 63 N. lugens samples were collected from 21 distinct geographic locations across ten key rice-growing states of India, including Haryana, Punjab, Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Kerala (Table 1). At each site, three biological replicates were obtained, ensuring robust representation per location. This sampling strategy covered both adult and nymph stages and provided a broad ecological cross-section, capturing diverse rice agroecosystems. The geographic coordinates of the sampling sites ranged from 10.54°N (Kerala) to 29.85°N (Haryana), reflecting coverage across both northern and southern rice belts (Fig: 1). All the samples were amplified for MtCOI gene of 710 bp and visualised under UV Transilluminator (Fig:2). Importantly, after sequencing and quality control in CODONCODON software, all 63 MtCOI sequences were confirmed to be intact, showing no insertions, deletions, or premature stop codons, thereby verifying the integrity of the mitochondrial gene regions for analysis. All high-quality sequences were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database, and the respective accession IDs are listed in Supplementary Table S1 for reference. These sequences served as the foundation for downstream assessments of genetic variation and population structure in N. lugens populations across India.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic reconstruction using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates revealed well-supported clades among the analyzed sequences (Fig. 3). The Indian N. lugens sequences grouped predominantly into a single monophyletic clade with a strong bootstrap value of 97%, clearly separated from the reference sequences, including those from Karnataka (NBAIR), Odisha (NRRI), and Uttar Pradesh. Within this Indian clade, two additional sub-clades were observed i.e., one primarily containing 15 sequences from Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, supported by a bootstrap value of 91%, and another cluster with 12 mixed-origin sequences showing bootstrap support of 90%. Interestingly, a few sequences from this study clustered near sequences from other countries, suggesting possible historical connections or shared ancestry. The node connecting the major green and blue clades showed a bootstrap value of 70, indicating moderate confidence in deeper evolutionary relationships. Overall, the tree topology indicates that Indian BPH populations exhibit subtle genetic structuring at regional scales and maintain clear separation from many international reference lineages. This confirms both local differentiation and broader genetic cohesion. The Bayesian phylogenetic tree depicts the evolutionary relationships among N. lugens populations from various Indian states alongside reference sequences of other countries. The tree revealed a strong monophyletic clade comprising all Indian samples, supported by high posterior probabilities (100) (Fig. 4). This indicates robust genetic cohesion. Outgroup species (N. bakeri and S. furcifera) form a clearly distinct lineage, validating the tree topology and evolutionary divergence among species.

Visualization of amplified PCR product using electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and staining by ethidium bromide. Lane M: 1 kb DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Lane P: Positive control, Lane NC: Negative Control, Lane NTC: Non-template control, Lane 1–21: Lanes 1–21: MtCOI amplicons from field-collected N. lugens samples. All sample lanes show a clear ~ 710 bp band corresponding to the expected fragment size.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree constructed using MtCOI sequences illustrating the genetic relationships among Indian populations of N. lugens. Coloured branches indicate major clade-wise grouping and genetic differentiation among the sequences generated in the present study. Outgroup sequences (Nilaparvata bakeri and Sogatella furcifera) are highlighted in red. Numbers displayed at the nodes represent bootstrap support values. The scale bar denotes the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Bayesian Inference (BI) phylogenetic tree based on MtCOI sequences showing the genetic relationships among N. lugens populations collected across India. Samples generated in the present study are marked with black circles, while blue circles indicate sequences retrieved from NCBI used for comparative analysis. Outgroup sequences (Nilaparvata bakeri and Sogatella furcifera) are highlighted in red. Numbers at the nodes represent Bayesian posterior probability support values.

Haplotype diversity and distribution

Haplotype analysis of the 63 mtCOI sequences from 21 populations revealed two distinct haplotypes, separated by three nucleotide substitutions. Haplotype 1 was predominant, accounting for approximately 85% of the sequences (54 out of 63), while Haplotype 2 was detected in a few northern populations, including Punjab.The overall haplotype diversity (Hd) and nucleotide diversity (π) were low, indicating limited genetic differentiation among populations. This pattern is further supported by the haplotype network (Fig. 5), where identical sequences are grouped into two clusters represented by merged nodes. The AMOVA results revealed that 96.46% of variation existed within populations, with 3.54% among populations, but with an FST of ~ 0.72, indicating moderate regional structuring. This outcome reflects real structuring within an otherwise widely shared genetic framework. Genetic diversity analysis revealed that the northern-central group (21 sequences) displayed a haplotype diversity (Hd) of 0.286, nucleotide diversity (π) of 0.00135 and consisted of two haplotypes across three polymorphic sites (Fig. 5) The southern group (42 sequences) showed slightly lower values, with Hd = 0.143 and π = 0.00112. Across all 63 sequences, the total haplotype diversity was 0.286, nucleotide diversity was 0.00045, and only two haplotypes were identified overall (Tables 2, 3 and 4). These numerical patterns suggest a largely homogenous population structure with minimal sequence divergence across India. The presence of only two haplotypes point toward either a recent common ancestry or strong ongoing gene flow among regions. The higher haplotype diversity in the northern-central group compared to the south may reflect localized genetic differentiation or historical demographic events. However, the nucleotide diversity reported in the current study across the entire dataset indicates that most of the genetic variation is shared, supporting the idea of interconnected population. This level of differentiation aligns with earlier findings in Asian BPH studies, where large-scale migrations and wind-mediated dispersal contribute to genetic mixing across broad landscapes. The AMOVA results revealed that 96.46% of variation existed within populations, with 3.54% among populations, but with an FST of ~ 0.72, indicating moderate regional structuring. This outcome reflects real structuring within an otherwise widely shared genetic framework. Minor geographic signals, such as slightly higher haplotype diversity in the northern-central group (Hd = 0.286) than in the south (Hd = 0.143), support this notion.

TCS haplotype network of the MtCOI sequences of N. lugens populations collected from ten states of India. Each circle represents a distinct haplotype, and the size of the circle is proportional to the number of individuals sharing that haplotype. The lines connecting haplotypes represent mutational steps, with each line indicating a single mutation. Colours denote the geographic origin of individuals: Kerala (KA, n = 3), Odisha (OD, n = 3), Andhra Pradesh (AP, n = 6), Telangana (TG, n = 24), Haryana (HR, n = 3), New Delhi (DL, n = 3), Karnataka (KR, n = 9), Maharashtra (MH, n = 6), Punjab (PB, n = 3), and Chhattisgarh (CG, n = 3).

Haplotype network

The TCS haplotype network constructed using PopART software revealed a clear star-like pattern centered on the dominant haplotype. It accounted for approximately 85% of the sequences. This central haplotype was shared across both northern-central and southern regions, while the rare secondary haplotype was confined to a few southern locations. The network displayed only three mutational steps separating the observed haplotypes, underscoring the limited genetic divergence within the Indian populations. This configuration suggests a recent population expansion where most individuals trace back to a common maternal ancestor, with rare haplotypes representing either recent mutations or isolated local variants. The low number of mutational steps and absence of multiple branching clusters further indicate that no deep genetic splits or long-standing isolated lineages are present in the dataset. These findings are consistent with patterns observed in other planthopper species and support the notion that strong gene flow due to wind dispersal and agricultural practices must have shaped the genetic makeup of Indian N. lugens populations.

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the molecular diversity and phylogeographic structure of BPH populations across India using mtCOI sequences. On sampling 63 populations from 21 geographically and ecologically distinct rice-growing regions, the results revealed 2 haplotypes. These findings suggest a largely panmictic population structure with minor geographic clustering, supporting previous reports on BPH dispersal patterns and host adaptation7,25,32,33.

The identification of two haplotypes across all sequences, with one dominant haplotype shared by 85.7% of the individuals, is indicative of high gene flow. Our results are consistent with earlier studies across tropical Asia, where high mobility and seasonal migration have contributed to genetic homogenization. For instance, Mun et al.. (1999)7 reported limited geographic structure in both N. lugens and S. furcifera Harvath using mtCOI data. He attributed the observed panmixia to wind-aided dispersal and the widespread cultivation of susceptible rice varieties. Their analysis revealed a dominant haplotype shared across populations from Korea, China, and the Philippines, with almost no variation detected within or between populations from the Indochina peninsula that supports high gene flow and regular mixing. Notably, their study showed that Chinese populations likely served as the primary source of yearly N. lugens immigration into Korea and Japan. Our findings align closely with this pattern. Despite sampling N. lugens from 21 populations across ten diverse Indian states, we detected two haplotypes with minimal nucleotide divergence. This supports the hypothesis that wind-mediated dispersal and large-scale monoculture practices not only facilitate long-range migration but also suppress regional genetic differentiation. Together, these results reinforce the view that N. lugens exhibits continent-scale genetic connectivity driven by ecological and agricultural forces.

A recent study by Anant et al.., (2022)31 compared N. lugens populations from India, Bangladesh, China, and Japan and identified 47 haplotypes. Indian populations showing low nucleotide (0.004) and haplotype diversity (0.667), suggesting limited genetic differentiation. Despite regional sampling, geographic distance had little influence on population structure, and demographic signals pointed to a recent expansion. These findings align with our results, further supporting the view that N. lugens populations across Asia maintain high gene flow and low regional isolation due to migratory behaviour. Our findings contrast with studies where more structured populations have been detected using nuclear markers or biotype-specific resistance screening. For example, using EST-SSR markers observed clear genetic separation among biotypes, suggesting that mtCOI gene may not fully capture all dimensions of population structure, particularly those influenced by host resistance adaptation17. Similarly, using SSR and SRAP markers reported higher polymorphism in virulent Indonesian populations compared to avirulent ones, underscoring the role of host-plant selection pressure in shaping genetic patterns4.

Our phylogenetic analysis supports the panmixia hypothesis, showing that all Indian sequences clustered into a single monophyletic clade with strong bootstrap support. Sub-clade formation among Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh populations reflects mild regional differentiation, which may be due to agroclimatic variation or different rice cultivar usage. The presence of a few sequences showing affinity to international references further indicates the potential for long-range gene flow, possibly due to transboundary migration or historical lineage sharing. The haplotype network’s star-like pattern, with a central, highly frequent haplotype and few peripheral variants, aligns with scenarios of recent demographic expansion. This structure was similarly reported by Arabit et al.. (2024)25 reported moderate genetic diversity in N. lugens populations from the Visayas region of the Philippines, identifying five distinct haplotypes with relatively high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.780) and low nucleotide variation. These similarities suggest that N. lugens populations in both regions may be shaped by comparable forces, including strong selection pressure from resistant cultivars and large-scale movement across landscapes.

However, our results contrast with findings from Indonesia8, Indonesian populations exhibited a more structured pattern and reported the presence of Biotype Y which is a highly virulent and distinct group not detected in our Indian dataset. This absence suggests that Indian BPH populations may not yet have undergone the same degree of biotype diversification or that such biotypes exist but remain undetected due to limited marker resolution. Notably, Latif et al.. (2012)30 also demonstrated strong genetic structuring between sympatric BPH populations feeding on rice and Leersia hexandra, highlighting the potential for host-associated divergence even within the same geographic zone.

Although neutrality tests (Tajima’s D, Fu and Li’s D and F) yielded negative but non-significant results, their direction is still suggestive of population expansion. Combined with the low nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00045 overall), these results further substantiate the hypothesis of a recent demographic expansion, possibly following a bottleneck or a selective sweep driven by resistant host selection. This is supported by ecological observations from tropical Asia, where widespread outbreaks of N. lugens have been linked to selective pressures such as insecticide overuse, nitrogen-rich hybrid rice cultivation, and synchronized population growth across regions factors that may facilitate rapid expansions and genetic connectivity among subpopulations10.

Mitochondrial genes such as COI have proven to be powerful tools in tracing population histories and estimating gene flow and migration, primarily due to their maternal inheritance, haploid nature, and lack of recombination26,27. These features allow mitochondrial DNA to provide a clearer signal of recent evolutionary events compared to nuclear markers, which undergo recombination and biparental inheritance. The mtCOI region, being maternally inherited, conserved, and free from recombination, continues to serve as a preferred molecular tool for tracking genetic diversity and migration in hemipteran pests. Furthermore, our findings also additionally reinforce the utility of mtCOI as a reliable marker for population-level analysis and surveillance of BPH genetic structure. However, the integration of nuclear markers such as SSRs or SNPs23 would complement mtDNA results and allow for biotype-level resolution and detection of adaptive divergence.

The AMOVA findings resonate with the work on WBPH populations across Myanmar and Yunnan, where high within-population variation coexisted with moderate differentiation among regions33. Similarly, 20 haplotypes in WBPH populations across East and Southeast Asia was identified along with their diversity being shaped by both migration and sampling effort34. Pairwise FST values between individual populations also supported moderate to high levels of genetic differentiation between some regions, especially between southern states (Kerala, Andhra Pradesh) and northern populations like Punjab and Haryana.

To conclude, our mtCOI-based analysis of N. lugens populations across India showed the presence of genetic variation, with one haplotype being dominant across regions. The nucleotide diversity and spatial differences of our analysis suggest that N. lugens has a high ability to migrate and mix between populations. These findings provide important insights for planning effective, large-scale pest management strategies. It is crucial to note that the extensive genetic uniformity and mobility that were observed in this study serve as an early warning It says that under changing climate conditions that facilitate pest survival and dispersal, these populations may expand swiftly and precipitate more frequent or severe outbreaks in the future. This is supported by ecological niche modelling, which predict that climate change will significantly increase the suitable habitat range for N. lugens in India, especially with rising temperatures35. It indicates an urgent need for adaptive surveillance and mitigation strategies. These patterns mirror those reported in other parts of Asia and underline the importance of coordinated regional monitoring. Future studies integrating nuclear markers, biotyping assays, ecological modelling, and host plant resistance data are essential for better understanding the genetic dynamics of BPH populations and for improving pest management strategies across rice ecosystems.

Conclusion

The study analysed N. lugens samples from 21 geographically diverse Indian rice ecosystems and revealed moderate genetic diversity with minimal regional structuring. A single dominant haplotype was prevalent across most populations, indicating extensive gene flow likely facilitated by wind-aided dispersal and monoculture practices and a second haplotype in few regions of study. Phylogenetic and haplotype network analyses suggest a recent demographic expansion. While such genetic connectivity may inform large-scale management strategies, it simultaneously signals the potential for swift transregional outbreaks under changing climatic scenarios. Future efforts should encourage integrative genomics, spatiotemporal modelling, and advanced molecular diagnostics to enable anticipatory surveillance and precision-guided N. lugens mitigation frameworks.

Methods

Sample collection and study area

The BPH samples were collected during the 2024–2025 rice cropping seasons from 21 locations across ten geographically diverse states in India: Haryana, Punjab, Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Kerala. These regions represent major rice cultivation zones with distinct agroclimatic conditions, ranging from humid coastal plains to semi-arid inland belts. This wide ecological coverage irrespective of variety was chosen to capture potential geographic structuring of N. lugens populations within the Indian subcontinent. In each state, three biological replicates were collected, totalling 63 samples across 21 populations. Each population consisted of twenty insects. Adult and nymphal stages of BPH were aspirated directly from rice plants using a hand-held mechanical aspirator, a non-destructive method ensures clean capture and minimal sample degradation. Immediately after collection, the insects were transferred into sterile microcentrifuge tubes containing absolute ethanol (≥ 95%) and all collected insects were frozen at − 70◦C for further use for downstream molecular analysis. Locations (district and state), GPS coordinates, Sequence ID, collection date are shown in Table 1.

Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from individual planthopper specimen using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method, following standard protocols optimized for BPH36. DNA was precipitated using chilled isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in nuclease-free water. The concentration and purity of extracted DNA were evaluated using NanoDrop spectrophotometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and integrity was checked on 1.5% agarose gels. DNA extracts were stored at − 20 °C until PCR amplification.

PCR amplification of MtCOI gene

To assess mitochondrial genetic variation, we targeted a 710 bp fragment of the cytochrome oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) gene using the universal primer pair LCO1490 (5′- GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′) and HCO2198 (5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′), as originally described by Folmer et al. (1994)37. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a final volume of 25 µL comprising 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 10 pmol of each primer, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific), and ~ 50 ng of genomic DNA. PCR cycling was conducted using a Bio-Rad thermal cycler under the following conditions: 94 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1:30 min; with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplification success was verified by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. Amplified PCR products were purified using a GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (Catalog number K0701).

Sanger sequencing and quality control

The purified amplicons were submitted for bidirectional Sanger sequencing to Barcode Biosciences, a commercial genomics facility based in Bangalore, India. Sequencing was performed using the both the primers i.e., LCO1490 and HCO2198 to ensure complete coverage of both forward and reverse strands. Chromatogram files were inspected for peak quality and trimmed to remove low-quality ends using CodonCode Aligner and BioEdit v7.2.5, ensuring generation of high-fidelity consensus sequences.

Genetic diversity and phylogenetic analyses

A total of 63 mtCOI sequences obtained from 21 geographical locations were used for analysis. The initial amplicons were 710 bp in length before assembly and quality-check. Following manual trimming using BioEdit, clean sequences of 600 bp were retained for downstream analysis. Each of the 21 populations was represented by three high-quality sequences. To provide broader phylogenetic context, reference sequences from previous studies were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database and included in the analysis alongside the 63 sequences generated in this study.

A Nilaparvata bakeri and Sogatella furcifera were used as outgroup species for phylogenetic analysis. All MtCOI sequences, including both study-generated and reference sequences, were aligned and used to construct a phylogenetic tree. A Maximum Likelihood tree was generated using the Neighbor-Joining method under the Jukes-Cantor model of nucleotide substitution38, with bootstrap resampling performed 1,000 times to assess branch support in MEGA v12 software39,40. The newick file was visualized in ITOL version 7.1. The tree topology was assessed for clade support and geographic clustering patterns, allowing interpretation of potential regional lineages and migration histories.

Population genetic analysis

Genetic diversity parameters, including the number of haplotypes, haplotype groups, haplotype diversity (Hd), nucleotide diversity (π), the number of polymorphic sites, and genetic differentiation were analyzed using DnaSP v6.10.0141. To analyse diversity, the sequences of samples from Haryana, Punjab, Delhi, Maharashtra, Odisha and Chhattisgarh were grouped as North Central while those from Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Kerala were categorised as South group. Neutrality tests such as Tajima’s D42, Fu and Li’s F, and Fu and Li’s D were conducted to assess deviations from the neutral model of evolution. In addition, mismatch distribution analyses were performed in DnaSP to infer the long-term demographic history of the populations.

Fu and Li’s D_test and F_test and Tajima’s D tests of neutrality index and genetic differentiation will be useful for demographic history information, and thereby were also performed using DnaSP ver. 5.10.01 software for detecting the range of population expansions. The genetic differentiation (FST) between different state populations in range referring to the criterion by Wright defined genetic differentiation as low for FST < 0.05, moderate for 0.05 < FST < 0.15, high for 0.15 < FST < 0.25 and very high for FST > 0.25. The goodness of fit of population expansion analyse done with Raggedness indices model according to Harpending.

To assess genetic variation across different populations, Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) was performed using Arlequin v3.543. A TCS haplotype network was constructed using PopART v1.744 to visualize relationships among haplotypes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Chinna Babu N. V., repository [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/].

References

Abeysekara, I. & Rathnayake, I. Global trends in rice production, consumption and trade. Consumption Trade (2024).

Prismantoro, D. et al. J. Agric. Food Res. 18, 101324 (2024).

Bragard, C. et al. Navas Cortes, J. A. Pest categorisation of Nilaparvata lugens. EFSA J. 21, e07999 (2023).

Chaerani, R., Sahid, M., Hidayat, P. & Santoso, S. SSR and SRAP markers revealed genetic divergence among Indonesian brown planthopper populations. Indonesian J. Agril Sci. 22, 83–92 (2021).

Wang, Q., Luo, C. & Wang, R. Insecticide resistance and its management in two invasive cryptic species of Bemisia tabaci in China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6048 (2023).

Lamba, K. & Dono, D. A review on brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål), a major pest of rice in Asia and Pacific. Asian J. Res. Crop Sci. 6, 7–19 (2021).

Mun, J. H., Song, Y. H., Heong, K. L. & Roderick, G. K. Genetic variation among Asian populations of rice planthoppers, Nilaparvata lugens and Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae): mitochondrial DNA sequences. Bull. Entomol. Res. 89, 245–253 (1999).

Listihani, L., Ariati, P. E., Yuniti, I. G. & Selangga, D. G. The brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) attack and its genetic diversity on rice in Bali, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Diver. 23, 4696–4704 (2022).

Kumar, P. The brown planthopper as a recurrent danger to high-yielding rice cultivation. Academia: an Int. Multidis Res. J. 11, 1221–1229 (2021).

Horgan, F. G., Bernal, C. C., Ramal, A. F., Almazan, M. L. & Mundaca, E. A. Crisol-Martínez E. Heterosis for resistance to insect herbivores in a 3-line hybrid rice system. Insects 15, 164 (2024).

Yan, L. et al. Recent advances in molecular mechanism and breeding utilization of brown planthopper resistance genes in rice: an integrated review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 12061 (2023).

Khush, G. S. Rice breeding: past, present and future. J. Genet. 66, 195–216 (1987).

Laksminarayana, A. & Khush, G. S. New genes for resistance to the brown planthopper in rice. Crop Sci. 17, 96–100 (1977).

Babu, S. B. et al. Genetic analysis of brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål.) (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) based on microsatellite markers. Curr. Sci. 125, 777 (2023).

Thanysiriwat, T., Pattwatan, P. & Angeles, E. R. New biotypes of brown planthopper in Thailand. Rice Sci. J. 30, 386–389 (2021).

Saxena, R. C. & Barrion, A. A. Classification of the three Korean biotypes of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stal) by morphological variation. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 32, 317–322 (1993).

Jing, S. J. et al. Development and use of EST-SSR markers for assessing genetic diversity in the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål). Bull. Entomol. Res. 102, 113–122 (2012).

Chaerani, R., Sahid, M. & Hidayat, P. Molecular analysis of virulent and avirulent BPH biotypes using SRAP and SSR markers. Pl Prot. J. 35, 1–10 (2023).

Shufran, K. A. & Whalon, M. E. Genetic analysis of brown planthopper biotypes using random amplified polymorphic DNA-polymerase chain reaction (RAPD-PCR). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 16, 27–33 (1995).

Bahagiawati, B. & Rijzaani, H. Clustering of brown planthopper biotype based on RAPD-PCR. HAYATI J. Biosci. 12, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4308/hjb.12.1.1 (2005).

Li, G. & Quiros, C. F. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on a simple PCR reaction: its application to mapping and gene tagging in brassica. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103, 455–461 (2001).

Dong, Z., Wang, Y., Li, C., Li, L. & Men, X. Mitochondrial DNA as a molecular marker in insect ecology: current status and future prospects. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 114, 470–476 (2021).

Pentinsaari, M. Utility of DNA barcodes in identification and delimitation of beetle species with insights into COI protein structure across the animal kingdom. Academic dissertation, University of Oulu (2016).

Deagle, B. E., Jarman, S. N., Coissac, E., Pompanon, F. & Taberlet, P. DNA metabarcoding and the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I marker: not a perfect match. Biol. Lett. 10, 20140562 (2014).

Arabit, J. K., Montecalvo, M. P. & Sapin, G. D. Genetic diversity and susceptibility of the selected Visayas populations of brown planthopper. Philippine Entomol. 38, 1–22 (2024).

Simon, C. et al. Evolution, weighting and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 87, 651–701 (1994).

Roderick, G. K. Geographic structure of insect populations: gene flow, phylogeography and their uses. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 41, 325–352 (1996).

Jones, P. L., Gacesa, P. & Butlin, R. K. Systematics of brown planthopper and related species using nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Syst. Assoc. Spec. Vol. 53, 133–148 (1996).

Zhang, D. X. & Hewitt, G. M. Insect mitochondrial control region: a review of its structure, evolution and usefulness in evolutionary studies. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 25, 99–120 (1997).

Latif, M. A. et al. Genetic dissection of sympatric populations of brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål), using DALP-PCR molecular markers. Sci. World J. 1, 586831 (2012).

Anant, A. K. et al. Evaluation of brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Stål.) resistance. Indian J. Entomol. 83, 223–225 (2021).

Hereward, J. P. et al. Migration dynamics of an important rice pest: the brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) across Asia-Insights from population genomics. Evol. Appl. 13, 2449–2459 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. The genetic diversity of white backed planthoppers (Sogatella furcifera) between Myanmar and Yunnan Province of China. Genes 14, 2164 (2023).

Matsumoto, Y. et al. Mitochondrial Cox sequences of Nilaparvata lugens and Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae): low specificity among Asian planthopper populations. Bull. Entomol. Res. 103, 382–392 (2013).

Guru, P. P. G. et al. Predicting the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stl) (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) potential distribution under Climatic change scenarios in India. Curr. Sci. 121, 1600–1609 (2021).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R. & Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 294–299 (1994).

Jukes, T. H. & Cantor, C. R. Evolution of protein molecules. In Mammalian Protein Metabolism (ed. Munro, H. N.) 21–132 (Academic, 1969).

Soltis, P. S. & Soltis, D. E. Applying the bootstrap in phylogeny reconstruction. Stat Sci 18, 256–267 (2003).

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M. & Kumar, S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 (8), 1596–1599 (2007).

Rozas, J. et al. Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302 (2017).

Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989).

Excoffier, L. & Lischer, H. E. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and windows. Mol. Ecol. Res. 10, 564–567 (2010).

Clement, M., Posada, D. C. & Crandall, K. A. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1657–1659 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to their affiliated institution, ICAR-IIRR, Hyderabad; the Director, ICAR-IIRR, Hyderabad; and DST-SERB for their support. We also thank the anonymous editor and reviewers for their valuable comments, which helped improve the quality of our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VCBN planned the experiment, manuscript preparation, formal analysis; KAVS data collection, data analysis and compilation of results; AK Sample collection for the experiment. PRV and PT Data Analysis; RMS reviewed the manuscript and project plan.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors agree to publish the paper in scientific report.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naik, V.C.B., Sindhura, K.A.V., Kokkula, A. et al. Genetic structure and haplotype diversity in Indian populations of brown plant hopper, Nilaparvata lugens stal using mtCOI. Sci Rep 16, 2971 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32756-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32756-7