Abstract

This research examines the advantages of utilizing 3D hand skeletal information for sign language identification from RGB videos within a cutting-edge, multi-stream deep learning recognition framework. Since most sign language datasets are just standard RGB video with no depth information, we want to use a robust architecture that has been mostly used for 3D human pose estimation to get 3D coordinates of hand joints from RGB data. After that, we combine these estimates with extra sign language data streams, such as convolutional neural network-derived representations of the hand and head pose estimation, using an attention-based encoder-decoder to identify the signs. We assess our proposed methodology using a corpus of isolated signs from AUTSL and WLASL, demonstrating substantial improvements through the incorporation of 3D hand posture data. Our method achieved 90.5% accuracy on AUTSL and 88.2% accuracy on WLASL, with F1-scores over 0.89, which is better than several state-of-the-art approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the most widespread health issues in the world. The World Health Organization estimates that two and a half billion people will have some form of hearing impairment by 2050; 700 million of them will require hearing re-education1. As a result, the dependency on sign language increases. Just like spoken languages, sign language is also very distinct. There are various sign languages used all over the world, such as Chinese Sign Language (CSL), American Sign Language (ASL), and Australian Sign Language (Auslan)2. Sign language is a language that uses both non-manual gestures and manual gestures3. Most sign words rely on manual gestures for communication between hearing-impaired individuals. Most signs are produced with non-manual gestures such as facial expressions and body situations. In many sign languages, non-manual gestures represent a significant role in conveying information and emotions that cannot be communicated through only manual gestures. For instance, expressions of the face are often produced to indicate negation in sign languages and play the role of adjectives or adverbs that change manual sign’s significance4. Furthermore, expressions on the face are used to differentiate between signs that have identical manual gestures. Static and dynamic signs are the two categories into which signs can be divided based on the movements involved. The majority of letters and numbers in sign language are static signs, meaning they don’t move. Hand orientations and finger shapes play a major role in these signs5. Dynamic signs, on the other hand, entail the manual and non-manual gestures. Most of the sign words in the sign language lexicon are represented by these signs. Therefore, in order to portray signs when the motion gesture is basic, a video stream is needed. The process of recognizing sign movements in static or dynamic scenes and translating them into their counterpart in a natural language is known as recognition. According to the input given, this step may produce individual words or sentences as its output. When a sign is received, isolated sign recognition frameworks translate it into an equivalent spoken word. Systems for continuous sign language recognition recognize a series of signs made each next to the other and produce a set of words that make up sentences. The grammar and sentence structure of the original sign language are present in these sentences, which typically differ from those of natural languages. Numerous methods have lately been put out for sign language recognition. Nonetheless, some constraints still require attention. First of all, when learning and classifying signs, the majority of sign recognition algorithms take into account the frames of all signs. As a result of the differences in the signs made by various signers, the accuracy of recognition may be reduced. Consequently, a method is required to identify the primary postures of the sign motion while disregarding the minor ones. Second, the majority of temporal learning methods for dynamic sign gesture recognition were unable to effectively learn non-manual motions. This article concentrates on isolated sign recognition benchmarks (AUTSL, WLASL); nevertheless, we recognize that transitioning to continuous sign language recognition (CSLR) presents other issues, including sign coarticulation and border segmentation, which we will address in the Limitations section. The main contributions of this research are as follows: 1. The RGB videos that are input can be transformed into skeletal data by the data qualification step. The frame sampling phase is supplementary and appropriate in situations where rapid recognition is needed. 2. We create a two-stream feature extraction network. The first stream extracts features to provide fine-grained accuracy for predicting head pose. In the second stream, temporal features are extracted using the Attention Enhanced Temporal Convolutional Network (AETCN), while multi-scale features are extracted using the Multi-Scale Attention GCN (MSA-GCN). Ultimately, the fully connected layer and global average pooling are employed to derive the categorization outcomes.

Related work

Recently, a large number of publications on the recognition of sign languages have been released to aid those who are hard of hearing. Multi-modal methods Huang et al. used a dual-channel approach to recognize gestures by combining muscle electrical data, hand acceleration, and angular velocity with the KNN algorithm6. Some investigations employed many pieces of modal information, referred to as a multi-modal technique, to improve recognition outcomes7. To categorize handgrip and finger movements, authors included electromyography data from the fingers and musculature of the arm8. One kind of neural network that is used to analyze sequences of data is the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)9. Cate et al. utilized the RNN to model time series and identify 95 different categories of sign language lexicon. Li et al. created new descriptors for hand types and used temporal modeling utilizing LSTM on these descriptors. This led to precise outcomes in Chinese sign language recognition10. A two-stream RNN network (2S-RNN) was proposed by Chai et al.11. In order to feed another RNN network, the model might excerpt features from the gradient histogram and skeleton data. For dynamic motion recognition, certain techniques often incorporate color information (in RGB format), bone joint point information, and depth map information. Nevertheless, obtaining data other than RGB images typically calls for a particular sensor, like the Realsense3 from Intel, the ASUS Xtion Pro, or Microsoft’s Kinect. In contrast, the low cost and ease of use of the RGB data-based motion recognition system are benefits12,13,14,15,16.

Skeleton-based approaches Skeletal data has also been employed for effective action recognition in numerous studies17,18,19,20,21. Architectures utilizing skeletal data have been prevalent in SLR tasks, emphasizing the simultaneous capture of global body motion and local arm, hand, or facial expressions. Tunga et al.22 introduced a skeleton-based sign language recognition approach that employed Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)23 to model spatial dependencies and Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)24 for temporal dependencies inside skeletal data in sign language recognition. The two representations were ultimately amalgamated to ascertain the sign class. Boháček and Hrúz25 introduced a systematic literature review (SLR) employing a Transformer model that utilizes skeletal data, incorporating innovative data augmentation techniques and delineating the spatial domains of hands and body according to their respective border values. In the last few years, transformer-based and diffusion-based methods have made even more progress in the field. For instance, SHuBERT35 learns strong multi-stream representations (facial, hand, and body) from huge ASL video corpora and does better than any other system on several benchmarks. ADTR36 suggests a Transformer-based system for recognizing and translating signs without gloss annotations. This system has good BLEU and recognition scores. Lightweight or specialized Transformer variations, such as TSLFormer37 and Spike-SLR38, can nevertheless provide good accuracy with only skeleton or event-based input. Diffusion models like SignDiff39 and Neural Sign Actors40 are pushing the limits of how to make sign language from text or skeletal data on the generative side. These recent papers suggest that using temporal attention, cross-stream fusion, and strong feature normalization is becoming more and more important. These are all things that fit nicely with what we did (head posture rectification + skeleton normalization + multi-stream fusion).

multi-stream & attention-based methods Nevertheless, as the pre-established graphs might not be ideal for particular categories, many studies26,27,28,29,30 advocate for various forms of adaptive graphs derived directly from data. Additionally, other studies investigate the significance of bone and motion data in skeletal information through multi-stream graph convolutional networks31,32,33,34 utilizing a straightforward delayed integration approach.

Recent research has investigated 3D reconstruction and depth estimation techniques for sign and gesture recognition, employing RGB-D sensors or monocular depth recovery. These methods get very detailed information about hand poses and add to skeletal representations, which often makes them more resilient to occlusion and signer variability. Although these methods do work, they usually need certain sensors.

These methods made the models more durable, but they mostly used raw head pose or unnormalized skeletons, which made them susceptible to changes in camera angle and differences between signers. In contrast, our solution explicitly incorporates both manual and non-manual elements inside a multi-stream structure. We present (i) head pose rectification, which aligns the signer’s face to a consistent virtual camera perspective, minimizing viewpoint distortions, and (ii) skeleton normalization, which re-centers skeletons at the hip and adjusts their scale in relation to torso size, providing scale- and translation-invariance. These processes make the model more resilient than previous skeleton-based and multi-stream models, which means that feature learning is more consistent across different signers.

Proposed approach

Overview

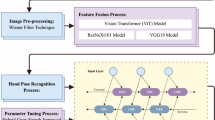

First, as illustrated in Fig. 1, we present the general framework of our suggested approach in this section. The data qualification step can transform the RGB videos into skeletal data. The frame sampling phase serves as a supplementary step and is suitable for situations requiring rapid recognition. Inspired by the work of41, the first stream conducts an extraction of features to provide fine-grained accuracy for predicting head pose. In the second stream, temporal features are extracted using the Attention Enhanced Temporal Convolutional Network (AETCN), while multi-scale features are extracted using the Multi-Scale Attention GCN (MSA-GCN). Ultimately, we employ the fully connected layer and global average pooling to derive the categorization outcomes.

Head pose estimation

In this section, we construct a lightweight CNN for the estimation of head position and suggest using image correction to lessen the effects of perspective distortion. To match the head center alongside the optical pivot of a virtual camera coordinate framework, we analytically straighten the input image, which was taken at the time the head center failed to correspond with the camera coordinate system. For 3D hand pose extraction, we employ the pretrained MediaPipe Hands framework developed by Google Research. This model combines a lightweight convolutional backbone with an inverse-kinematics solver to predict 21 hand keypoints in 3D from monocular RGB input. MediaPipe is used without any fine-tuning and provides stable, real-time skeletal estimates for both AUTSL and WLASL, making it suitable for datasets that do not include depth information or explicit calibration. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the real camera system (\(R_{C}\)) corresponds to the original imaging coordinate frame, while the virtual camera system (\(V_{C}\)) represents the rectified frame obtained after rotating the input so that the head center lies on the optical axis. The figure also clarifies the geometric elements used during this transformation, including the unit vectors \(e_z\) and \(u_z\), the rotation axis \(r = u_z \times e_z\), and the rotation angle \(\theta\), which together define the rotation that aligns the signer’s head for consistent pose estimation. The approach uses the face-surrounding box center as the principal center of the head after first identifying the face in the entry frame. Perspective warping is used to convert the detected facial area of the input frame \(R_{C}\) to \(V_{C}\). Following warping, the virtual optical center and the head center of the adjusted frame line up. In \(V_{C}\), the facial area of the adjusted frame is trimmed and then employed as the entry to the estimation network for determining the head pose. As the last step in the estimation process of the head pose, the estimate network’s output is converted to return to the coordinate system of the camera \(R_{C}\).

Camera system transformation

The pinhole camera pattern projects the face upon the frame plane \(P_{O}\). To transform the face center in \(R_{C}\) along the optical axis in \(V_{C}\), one needs to compute a rotation matrix specifying the conversion between \(V_{C}\) and \(R_{C}\). The 3D rotation of the face for correction is given by the angle of rotation \(\theta\) and the vector of rotation axis r. As can be seen in 2, \(e_{z}\) represents the unit vector along the z-axis of \(R_{C}\), and \(u_{z}\) represents the projection unit vector of the head center to the optical center O of the camera. Assume that \(K = [f_{x}, 0, c_{x}; 0, f_{y}, c_{y}; 0, 0, 1]\) represents the camera projection matrix. In our implementation, the intrinsic parameters \((f_x, f_y, c_x, c_y)\) are taken directly from the dataset whenever they are provided. For AUTSL, we use the official calibration values included in the dataset metadata. For WLASL, where no calibration information is available, we follow a standard pinhole camera approximation: the focal lengths are set proportional to the frame size, and the principal point is placed at the image center. This normalized intrinsic matrix allows us to perform consistent rectification across videos recorded with different devices and viewpoints.

The focal distances of the camera in the x-axis and y-axis are \(f_{x}\) and \(f_{y}\), respectively, and the position of the frame optical center is \((c_{x}, c_{y})\). The homogeneity of the head center coordinate is represented by the symbol p; \(p = [p_{x}, p_{y}, 1]^T\), where the 3D position of the center of the head in \(R_{C}\) is designated by \(c = [x_{c}, y_{c}, z_{c}]^T\), and the center of the head in the input frame is represented by \((p_{x}, p_{y})\). The definition of the 3D projection is \(C = z_{c}K^{-1}p\). The projection of the head center to the camera optical center’s unit vector is \(u_{z} = \frac{c}{\Vert c\Vert _{2}} = \frac{K^{-1}p}{\Vert K^{-1}p\Vert _{2}}\). Equations 1 and 2 can be used to compute r and \(\theta\).

Here, \(\textbf{K}\) denotes the intrinsic camera matrix \(\begin{bmatrix}f_x & 0 & c_x\\ 0 & f_y & c_y\\ 0 & 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\), where \(f_x\) and \(f_y\) are the focal lengths (in pixel units) along the x and y axes, and \((c_x, c_y)\) is the principal point. \(\textbf{R}\) and \(\textbf{t}\) correspond to the camera rotation and translation matrices that define the extrinsic parameters. \(\textbf{X}\) represents a 3D point in world coordinates, and \(\textbf{P}\) is its homogeneous projection on the image plane.

The head center is determined by locating the face bounding box center. Let \(r=[r_{x}, r_{y}, r_{z}]^T\) be assumed the rotation matrix \(H_{P \rightarrow R}\) that characterizes the transformation between \(V_{C}\) and \(R_{C}\), where \(r_{x}^2+ r_{y}^2+ r_{z}^2 = 1\).

Image reprojection

To calculate the rectified face image, the face area of the input picture can be translated via the virtual image surface (\(P_{VI}\)) in \(V_{C}\) using the rotation matrix \(H_{P \rightarrow R}\). To conduct the reverse projection, we initially suppose that all of the pixels in the face frame have known depths. A reversal perspective projection, depicted in Eq. 3, can be used to determine the coordinates of the 3D point w that matches the pixel within the entry image at \((q_{xo}, q_{yo})\) and has a depth of \(z_{o}\) in relation to \(R_{C}\).

where \(q_{0}\) is the pixel’s homogeneous coordinate. The 3D point coordinates w in \(R_{C}\) can be multiplied by the rotation matrix \(H_{P \rightarrow R}\) to yield the 3D point coordinates \(w_{r}\) in \(V_{C}\). Equation 4 may be used to get the 3D point coordinates in \(V_{C}\) \(w_{r}\).

Employing full-perspective projection, the converted \(w_{r}\) can be projected upon \(P_{VI}\) of \(V_{C}\). Equation 5 may be used to determine the homogeneous coordinate \(q_{r}\) of the pixel emanating via \(w_{r}\), given that \(R_{C}\) and \(V_{C}\) divide the same matrix K.

where \(z_{r}\) is the third component of \(w_{r}\) in \(V_{C}\). Using the three previous equations, any pixels in the entry frame’s face area can be corrected or transformed using the following equation:

Head posture rectification makes the signer’s head look like the camera is right in front of them, even if it is tilted, rotated, or yawed. This makes sure that later features, like face landmarks or gaze direction, are measured in the same coordinate frame. Figure 3 shows the input head pose and the fixed outcome.

Head pose transformation

It is possible to transform the Euler angle-based head pose calculation into a rotation matrix. Where the yaw, pitch, and roll angles are denoted by \(\beta\), \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\), correspondingly42. \(H_{P}\) is the head pose of the ground truth, which may be transformed to the identical matrix form supplied by the datasets in \(R_{C}\). In \(V_{C}\), the head pose rotation matrix is represented by \(H_{R}\). The rotation matrix \(H_{P \rightarrow R}\) can be used to compute \(H_{R}\). Using the image correction technique, all training images in the benchmarks are converted from \(R_{C}\) to \(V_{C}\). Next, we convert the head pose of the ground truth from \(R_{C}\) to \(V_{C}\). The converted images and head pose of the ground truth in \(V_{C}\) are used to train our network.

Frame sampling

Enhancing the system’s precision and efficacy is the goal of the suggested SLR system. The retrieved frames of an SL video contain superfluous and redundant data. As a result, removing pointless and superfluous frames increases the system’s precision and efficacy. Finding specific frames that differ from other frames in terms of motion position forms the fundamental idea of frame sampling. We choose the histogram-difference (HD) method among a number of frame sampling approaches43. This method is frequently used in gesture detection and video summary44. HD looks at how the pixels are distributed between two frames, which makes it resistant to small changes in lighting and easy to calculate. HD needs a lot less computing power than other methods like optical flow or deep embedding-based selection, but it still picks up on big motion variations in sign language videos. These qualities make it a good choice for our task. The procedure runs in two stages. The first stage calculates each frame’s histogram. We then calculate the difference between two consecutive frames using the Euclidean distance method. The Euclidean distance approach produced the best result, yet other distance-based matrices are also employed, such as Manhattan distance, City block distance, Absolute distance and Euclidian distance. Following the distance calculation, we compute the standard and mean deviation from the sequence of distances. In the second phase, we compute the threshold value and compare it with the distances to obtain keyframes.

Construction of graph data

Some techniques have focused learning on the pertinent information by employing frame-based retrieved skeletons rather than the raw RGB frames. Strong skeleton collection procedures enhance these approaches’ recognition and learning performance, as they remain unaffected by extraneous information such as background. Keypoint sets of body joints or skeleton graphs with joint edges included are two formats in which extracted skeletons can be found. CNNs and RNNs were utilized in the early methods of action and sign language recognition in order to get the necessary temporal information45,46. These models’ incapacity to capture keypoint connections in both time and space is a drawback.47 presented the first Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN) as a solution to this drawback and demonstrated how well GCNs perform for learning the spatio-temporal skeletal dynamics. Nevertheless, ST-GCN uses solely the joint links of the human body to gather and analyze spatio-temporal keypoint information. Consequently, the exchanges of non-immediately related keypoints, like those between the two hands, receive less attention. From the RGB frames, we initially excerpted the two-dimensional skeleton information. The skeleton information can be thought of as \(X \in \textbf{R}^{T \times V \times C}\), where T represents the number of frames, V represents the number of joints in every frame, and C represents the number of channels, which relates to every joint’s dimension. The skeleton data of the \(t^{th}\) frame is \(X_{t} \in \textbf{R}^{V \times C}\). We created the graph data \(G=(V, E)\) from \(X_{t}\), where the set of vertices is \(V = (V_{1}, V_{2},..., V_{N})\), and the set of edges that join any two points in the graph is E. To build the graph from the skeleton, we assign the bones as the edges, and the human joints serve as the vertices. The starting value of C is 2, as the joint points that we obtained are two-dimensional coordinates. The adjacency matrix \(A \subseteq \textbf{R}^{V \times V}\) can be used to define E, which is the link between V vertices. Furthermore, since the graph we created is undirected, A is symmetrical:

where the smallest number of human bones between \(V_{j}\) and \(V_{i}\) is given by \(d(V_{i}, V_{j})\).

Skeleton data normalization

Human actions typically entail body movement, such as relocation and angle changes, and body sizes vary throughout individuals. Therefore, maintaining a constant skeleton data view angle and body size is crucial, as well as normalizing it. Instead of using the initial coordinates in absolute terms, we employ the normalized relative 3D coordinates in our work. Every joint in the initial skeleton data has three coordinates, which can be shown at frame t as \(P_{i}(t) = (x_{i}(t), y_{i}(t), z_{i}(t))\). We now use the hip center as our new source, and we can determine the new coordinates of the other joints by comparing their coordinates with the hip center. To eliminate the body size variation, we normalize every new coordinate by computing the distance between the spline joint and the shoulder center joint using the initial coordinates. We can then state each joint’s new coordinates as follows:

We depict the human upper body as a graph, with each joint serving as a node and each bone (anatomical connection) functioning as an undirected edge. An edge signifies “direct anatomical connection”; thus, features like position and motion move along bones, and the network learns how to relate poses to each other both locally and globally. If joints i and j are directly attached (one bone apart), then the adjacency matrix A is 1. If they aren’t, then A is 0. Figure 4 displays the three steps that make up the pipeline for the upper body.

Graph convolutional networks

In the classical method47, features were extracted for action data \(X \in \textbf{R}^{T \times V \times C}\) by alternating between spatial and temporal convolution. Each frame of data \(X_{t} \in \textbf{R}^{V \times C}\) is handled independently during the spatial convolution, which is represented as follows:

The matrix of adjacency of the undirected graph, which represents the connections of the intra-body, is represented by A. W denoted the network’s trainable weight matrix, and I denoted the matrix of identity. \(\sigma\) denoted a ReLU activation function, and \(\tilde{D}\) denoted the matrix of diagonal degree of \(\tilde{A}\). The Temporal Convolution Network (TCN) may be implemented as a two-dimensional convolutional network, with T and V serving as the extent of convolution and \(X_{t_{exit}} \in \textbf{R}^{T \times V \times C}\) as the input. The frames number in the approved field is denoted by \(K_{t}\), and we fix the kernel as \(K_{t} \times 1\). Therefore, we limit the temporal convolution function to the temporal dimension.

Multi-scale attention GCN

When modeling dependencies between distant vertices, the aforementioned GCN technique is ineffective. Given that joints typically span a greater distance than actions in sign language recognition operations, we proposed an MSA-GCN as the first module in the second stream. It includes two components: multi-scale GCN (MS-GCN), which captures features at multiple degrees, and the Multi-Scale Attention Mechanism (MSAM), which allocates attention weights to various scales.

Multi-scale GCN

In order to conduct GCN processes, we can utilize Equation 10 to rearrange the entry data of MS-GCN, which is \(X_{entry} \in \textbf{R}^{T \times V \times C_{entry}}\).

where the matrix of k-adjacency is \(A_{K}\) and the matrix of trainable weight is \(W_{K}\):

A can be extended to farther-off neighbors with \(A_{K}\). More specifically, \(A_{1} = A\). K also governs the number of aggregated scales. To gather various types of semantic information, we change the graph architecture by choosing a various scale k and carrying out concurrent GCN processes. Subsequently, merge the k divergent GCN outputs into \(X^{\prime } \in \textbf{R}^{T \times V \times kC_{exit}}\). The GCN finds it easier to understand the dependencies connecting distant vertices when the value of k is large.

Multi-scale attention mechanism

While standard GCN makes it easier to describe the interaction among distant vertices, MS-GCN allows graphs of various dimensions to acquire features at distinct levels. Nevertheless, MS-GCN only organizes the derived attributes into a stack. Figure 5 illustrates the sign “scream” and highlights the network’s ability to capture both long-range correlations between distant joints (e.g., hand–face) and local dependencies between adjacent joints. These observations motivate the design of the proposed Multi-Scale Attention Module (MSAM), which adaptively weights multi-scale features to represent signs with diverse spatial patterns.

As the output of MS-GCN, \(X^{\prime } \in \textbf{R}^{T \times V \times kC_{exit}}\), serves as the input of MSAM. \(f \in \textbf{R}^{K \times C_{exit} \times 1 \times 1}\) is obtained by first averaging \(X^{\prime }\) in temporal and spatial plans. The attention information on the multi-scale semantic features is then extracted by adding the first fully connected layer, which has \(K \times \frac{C_{exit}}{R}\),\((R > 1)\) neurons. The attention map (AM) is then obtained by copying the features on the dimensions V and T after using the second fully connected layer to re-establish features to the initial dimension of \(K \times C_{exit}\). To append attention information to the feature, \(X^{\prime }\) and the map of attention are linked. One of the variable parameters, R, is fixed at 2. The following equation describes the multi-scale attention technique:

AETCN: Attention enhanced temporal convolutional network

Multiple key actions and their transitions make up the majority of sign language acts. As a result, the significance of sign language varies over time. Frames that contain more discriminative information should receive more attention. We chose the Attention-Enhanced Temporal Convolutional Network (AETCN) and the Multi-Scale Attention Graph Convolutional Network (MSA-GCN) because they are a good mix of accuracy and speed. We also thought about using transformer-based temporal encoders, but early tests on a small part of the AUTSL dataset showed that transformer models needed a lot more memory and took a lot longer to converge without making a big difference in accuracy. The suggested combination of temporal convolution and graph-attention modules, on the other hand, led to steady training behavior and enhanced generalization for medium-sized sign language datasets. As a consequence, we created the AETCN, which is able to focus more on the sign language’s essential actions than on their transitional actions. After activating the sigmoid function, we copy the feature matrix in the \(C_{exit}\) size and the V-size to obtain the attention map. Initially, we carry out a global average pooling process to generate the V size average. This yields a matrix of features with dimensions of \(C \times T\), displacing T to the batch dimension. Next, we achieve a one-dimensional convolution, the output dimension being \(T \times 1\). The attention map has a dimension of \(C_{exit} \times V \times T\). The Attention-Enhanced Temporal Convolutional Network (AETCN) is made up of three dilated convolutional blocks and an attention-based channel weighting mechanism. It is shown in Fig. 6. It models how sign sequences vary on time.

Experiments

Datasets

We experiment on two datasets in this work: AUTSL48 and WLASL49. They stand for two categories of datasets. While WLASL emphasizes the variety of signers and their surroundings, AUTSL is mainly concerned with the number of utterances of a tiny number of signs by a relatively tiny sample of signers in a better driving. Additionally, elite performers are captured in WLASL recordings, while a combination of expert and novice signers perform AUTSL. Moreover, the amount of glosses that need to be recognized divides the WLASL dataset into multiple subsets. We employ the WLASL300 subgroup in this work. Table 1 provides a summary of the datasets characteristics.

43 distinct signers are recorded by AUTSL: six are Turkish sign language (TSL) professors, three are TSL interpreters, one is deaf, one is the kid of a deaf adult, twenty-five are students enrolled in TSL courses, and seven are experienced signers who have picked up the signs from the collection of data. There are thirty-three women and ten men among the signers; additionally, two of the signers are southpaws. The signers’ ages range from 19 to 50, with 31 being the mean age of all signers. Native American SL interpreters or signers always execute the sign instances in the WLASL dataset. The information was gathered from a variety of publicly available sources with the primary goal of teaching sign language. As a result, there are unrestricted variations in signing techniques or dialects, as well as video backgrounds.

Experimental setting

We evaluated our model using an Intel(R) Xeon(R) 2 CPUs, with 40 GB RAM, the MS Windows 10 operating system, Python software, and an NVIDIA Tesla K80 GPU. We applied our architecture to the Keras API. We use the Adam optimizer and set the mini-batch size at 50. We divide the learning frequency by 10 every ten epochs, starting at 0.001. The suggested model undergoes 80 training epochs with early stopping. Furthermore, we employ an acceleration of 0.9 and a weight loss of \(1^{-4}\). We used two datasets for the assessment. We employed the typical data split ratio, training (80%) and testing (20%). All experiments use a signer-independent partitioning technique to make sure that the evaluation is fair. The 80/20 ratio is about how the signers are split up, not the video samples themselves. This means that no signer is in both the training and testing groups. We used the official subject split given by the dataset authors for the AUTSL dataset. For the WLASL dataset, we randomly sorted signers into training and testing groups that did not overlap and had the same number of signers. This plan makes sure that the model’s effectiveness is based on generalizing to new signers instead of remembering specific people. For multi-class classification problems, we employed categorical cross-entropy as the loss function, which is usual. This decision is acceptable since each sign instance belongs to exactly one class, and cross-entropy efficiently penalizes wrong predictions while boosting confident correct categorization.

Evaluation metrics

We employed the metrics of mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), and coefficient of determination, or R-squared metrics, to assess the efficiency of our model. We calculate the MAE between the current and anticipated values of the dataset. The following equation provides it:

The following Equation can be used to compute the MSE between the dataset’s current and predicted values:

The model’s \(R^2\) score reveals how effectively it matches the provided dataset. It shows the degree to which the expected value and the current data values agree. The value ranges from 0.0 to 1.0, where 1.0 denotes the ideal match and 0.0 represents the worst match. The following equation was used to calculate it:

where \(\bar{y}\) indicates the y mean value and \(\hat{y}\) indicates the y projected value. The computation of errors was done using the three previous equations. Table 2 shows that the MSE and MAE scores are greater for the different evaluated models. This indicates that the residual’s variance and average are large. In addition, we tried to use our suggested model to generate relatively low prediction errors.

We present two categories of metrics: (i) regression metrics (MSE, MAE, \(R^2\)) for intermediate feature estimation modules such as head pose rectification, and (ii) standard classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) for standalone sign identification. The latter are highlighted as the primary performance metrics of our methodology. MAE, MSE, and R\(\phantom{0}^2\) are not direct measures of classification accuracy, but they are important for testing the intermediate estimation modules of our framework, which include head pose rectification and skeleton normalization. These modules’ accurate geometric alignment and low projection errors have a direct effect on the quality of the spatial-temporal features that are retrieved for recognition. These measurements show how well the auxiliary regression tasks help the downstream classification goals. This makes sure that the non-manual feature estimators work correctly before they are combined with the gesture-based stream.

Tables 2 and 3 together give an overview of how the proposed framework was tested. Table 2 shows regression metrics (MAE, MSE, R\(\phantom{0}^2\)) that check how accurate the intermediate estimation modules are, like head pose correction and skeleton normalization. Tables 3 and 5 shows how well the whole SLR model recognized data from the AUTSL and WLASL datasets using classification-based measures like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These tables show that each part of the proposed architecture has been quantitatively tested and that the whole system consistently achieves high-accuracy sign recognition performance.

Quantitative analysis

We examined the accuracy of prediction for each sign using the classification metrics, as shown in Table 4. Using four values, true negatives (TN), false negatives (FN), true positives (TP), and false positives (FP), these attributes include F1-score, recall, and precision that are computed. We performed experiments with various models, as listed in Table 2, by substituting each model for our suggested layers in the paper’s design. Accuracy is the number of accurately anticipated sign language losses; it ideally ought to be near to one. To evaluate statistical robustness, each experiment was conducted five times using distinct random seeds. We report the average performance and the standard deviation (mean ± SD) for all the runs. The slight differences seen show that the training is stable and the convergence is constant.

We calculate the positive predicted value, or precision, by dividing the total number of predicted positive class scores by the total number of positive predictions. Because of the costly nature of false positives, precision is a crucial metric to assess. Similar to accuracy, this metric must be close to unity.

Recall is a crucial metric to ascertain because of the significant cost of false negatives. Recall is the percentage of positive events that the model properly predicts.

The F-measure, or F1-score, a consistent mean of recall, and precision, signifies a balanced recall and precision. The F1 score reaches its maximum value of 1 when there is ideal recall and precision.

Based on the computations provided, Table 4 displays the classification findings. According to the classification metrics, the model’s F1-score, recall and precision are nearly all 1, with the exception of one value for each of the last two metrics and three values for the F1-score, which are nevertheless perfect for being near 1. This demonstrates that after completing training, our model successfully learned data. On the other hand, while the accuracy of other models like MNM-VGG16, Simple RNN, LSTM, MNM-SLR, and BiLSTM was good, their learning efficiency was not. Some baseline models show lower metric values on specific classes, indicating challenges in learning certain motion patterns. Their performance varies depending on architecture and dataset characteristics. Table 4 shows very high regression values (MSE, MAE, and R²). These values should be read with care. Part of the reason for these results is that the datasets were carefully chosen, and the intermediate head pose and skeleton normalization jobs don’t change much. Still, the risks of overfitting and class inequality can’t be ruled out. To make sure it was stable, we did several training runs with different random seeds and saw that the performance was always the same, with less than 1% difference between runs. This shows that the results are stable, but more cross-validation on a wider range of datasets would be helpful for future work.

Our proposed method achieves the highest \(R^{2}\) value among the evaluated configurations, indicating improved fit for the intermediate regression task within these experimental settings. This suggests that the model has a strong match. Figure 7 presents the training accuracy and loss for several models. From Fig. 7, the variation between epochs and loss and accuracy suggests inconsistent training. But with our model, training goes more quickly and smoothly because of effective data learning. Therefore, when compared to other models, including MNM-VGG16, Simple RNN, LSTM, MNM-SLR, and BiLSTM, respectively, our suggested model performs better with less loss. We find that our proposed model has the greatest test accuracy of 90.5% when compared to other models and a minimum loss of 0.19.

Table 4 shows very high regression values (MSE, MAE, and R²). These values should be read with care. Part of the reason for these results is that the datasets were carefully chosen, and the intermediate head pose and skeleton normalization jobs don’t change much. Still, the risks of overfitting and class inequality can’t be ruled out.

The standard deviations stay below 0.5% for accuracy and 0.01 for F1-score, which shows that the model’s performance is statistically stable over different runs. The minimal variances show that the optimization process is stable and that the measurements are accurate as shown in Fig. 5.

Ablation on model components

To quantify the contribution of each proposed module, we performed ablation experiments on the AUTSL dataset under five settings: (1) baseline model using 2D skeletons without head pose rectification or multi-scale attention; (2) baseline + head pose rectification (HPR); (3) baseline + normalized 3D skeletons (3D-Norm); (4) baseline + multi-scale attention (MSA); and (5) the full proposed model combining all components. Table 6 summarizes the results.

The results show that each part of the model improves its performance. Head posture rectification (HPR) increases accuracy by 2.2% by aligning non-manual factors like the direction of the face. Normalizing skeletons in 3D space makes stability even better for signers, adding 1.1% accuracy. The multi-scale attention mechanism gives the biggest single boost (0.8%) by focusing on spatial-temporal areas that are important. When put together, these modules improve the accuracy of the baseline model by almost 5%, which shows that each design choice made a difference.

Comparative analysis

We experimented on two distinct benchmark datasets, AUTSL and WLASL, respectively, to assess the effectiveness and achievement of our suggested model. We then compared our findings to those of various state-of-the-art models that are currently in use, such as I3D, Pose-based gated recurrent unit (Pose-GRU), and Pose-based temporal graph convolutional network (Pose-TGCN). Under the same evaluation protocol, our proposed model obtained higher accuracy than the selected baseline approaches. However, additional comparisons with a broader range of state-of-the-art methods would further validate these findings. With the use of fewer parameters and the activation function during training, our suggestion had a high efficiency in learning and a rapid rate of convergence when compared to other models employed in the experimentation. The isolated word-level sign recognition issue uniquely suits existing datasets. Therefore, we used two benchmark datasets with a sufficient number of instances and signers to assess our model. The combination of head pose rectification, skeleton normalization, and multi-scale attention contributes to improved efficiency in our experiments. While the results indicate advantages over the evaluated GCN and attention-based baselines, further testing is required to assess performance differences across a wider range of architectures.

Limitations and future work

Even though the suggested model performs well on the two datasets used in this investigation, there are still a number of drawbacks. First, the model has not yet been tested on continuous sign language, where co-articulation and transition movements add complexity, and the evaluation is limited to isolated sign recognition. Second, the model may be less able to generalize to real-world signing scenarios due to the limited diversity of signers, backgrounds, and recording conditions in both datasets. Third, any mistakes or occlusions at this stage could have an impact on the final classification because the method depends on precise pose and hand landmark estimation. Lastly, the method’s robustness across various sign languages is still unknown and has not been tested in cross-lingual or cross-dataset scenarios. In the future, we plan to extend the model to continuous sign language recognition. Evaluate it on a broader set of datasets, improve its robustness against pose-estimation errors, and explore more efficient architectures suitable for real-time use.

Conclusion

This research illustrated the advantages of integrating estimated 3D hand skeletal data into a multi-stream deep learning architecture for sign language recognition (SLR) from RGB films. Our method combined head pose estimation, 3D hand positions, and manual and non-manual information from CNNs. Our method worked well, with 90.5% accuracy on AUTSL and 88.2% accuracy on WLASL. The F1-scores were over 0.89, which is better than many other state-of-the-art methods. Although there are still some problems in the real world. Performance can be affected by body size, signing style, and facial expressions when signing. For interactive applications to work in the actual world, it is also important to make sure that inference speed is real-time. Also, if we want to use our method for continuous signing, we need to deal with segmentation, coarticulation, and non-sign transitions, which are not specifically represented in isolated recognition. Ethical issues are just as important. For example, making sure that different signer groups can access the system, fixing problems with biased datasets, and helping all of these systems work with real-life assistive technology will be necessary for responsible deployment. As a result, future work will focus on making real-time applications as efficient as possible, making them more robust for different signers, and expanding the foundation for continuous sign language detection.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available. AUTSL (A Turkish Sign Language Dataset): Available at https://chalearnlap.cvc.uab.cat/dataset/40/description/ WLASL (Word-Level American Sign Language Dataset): Available at https://dxli94.github.io/WLASL/.

References

World Health Organization. Deafness and Hearing Loss. WHO Newsroom Fact Sheets. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss Published 26 February (2025).

Howell, T., Sung, V., Smith, L. & Dettman, S. Australian families of deaf and hard of hearing children: Are they using sign? Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 179, 111930 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2024.111930 (2024).

Javaid, S. & Rizvi, S. Manual and non-manual sign language recognition framework using hybrid deep learning techniques. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 45, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-230560 (2023).

Proctor, H. & Cormier, K. Sociolinguistic Variation in Mouthings in British Sign Language: A Corpus-Based Study. Lang. Speech 66. 002383092211070 https://doi.org/10.1177/00238309221107002 (2022).

Hwangbo, H.J., Ji, Y. & Jo, J. Relations between handshape and orientation in simultaneous compounds in Korean sign language. Linguist. Res. 40, 119-150 https://doi.org/10.17250/khisli.40.1.202303.005 (2023).

Huang, D., Zhang, X., Saponas, T., Fogarty, J. & Gollakota, S. Leveraging dual-observable input for gine-grained thumb interaction using forearm EMG. the 28th Annual ACM Symposium. 523-528. https://doi.org/10.1145/2807442.2807506 (2015).

Neverova, N., Wolf, C., Taylor, G. & Nebout, F. ModDrop: Adaptive multi-modal gesture recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 38, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2015.2461544 (2014).

Adewuyi, A., Hargrove, L. & Kuiken, T. An analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic HandMuscle EMG for improved pattern recognition control. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 24, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2015.2424371 (2015).

Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 404, 132306 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2019.132306 (2020).

Li, X., Mao, C., Huang, S. & Ye, Z. Chinese sign language recognition based on SHS descriptor and encoder-decoder LSTM model. 719-728. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69923-3_77 (2017).

Chai, X., Liu, Z., Yin, F., Liu, Z. & Chen, X. Two streams recurrent neural networks for large-scale continuous gesture recognition. 31-3 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR.2016.7899603 (2016).

Sadeghzadeh, A., Shah, S. & Islam, M.B. MLMSign: Multi-lingual multi-modal illumination-invariant sign language recognition. Intell. Syst. Appl. 22, 200384 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswa.2024.200384 (2024).

Vahdani, E., Jing, L., Huenerfauth, M. & Tian, Y. Multi-modal multi-channel American sign language recognition. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Robo. Res. 01, https://doi.org/10.1142/S2972335324500017 (2023).

Balachandra, M. & Manjula, A. Multimodal real-time translation system for hearing impaired accessibility using deep learning. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 08, 1-4 https://doi.org/10.55041/IJSREM39280 (2024).

Singh, P. Sign language detection using action recognition LSTM deep learning model. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 08, 1-5 https://doi.org/10.55041/IJSREM34861 (2024).

Liu, E., Lim, J., Macdonald, B. & Ahn, H. Weighted multi-modal sign language recognition. 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive. 880-885 https://doi.org/10.1109/RO-MAN60168.2024.10731214 (2024).

Singh, A., Hashmi, F., Tyagi, N. & Jayswal, A. Impact of colour image and skeleton plotting on sign language recognition using convolutional neural networks (CNN). 14th International Conference on Cloud Computing. 436-441 https://doi.org/10.1109/Confluence60223.2024.10463239 (2024).

Shin, J. et al. Korean sign language alphabet recognition through the integration of handcrafted and deep learning-based two-stream feature extraction approach. IEEE Access 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3399839 (2024).

Osorio, T., Mozo, R., Sabanilla, K. & Gunay, N. WiKA: A vision based sign language recognition from extracted hand joint features using DeepLabCut. J. Eng Environ. and Agri. Res. 3, 19-28 https://doi.org/10.34002/jeear.v3i1.75 (2024).

Vijitkunsawat, W., Racharak, T. & Nguyen, L. Deep multimodal-based number finger spelling recognizer for Thai sign language. 22nd International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies. 99-104 https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCIT57293.2023.10376072 (2023).

Woods, L. & Rana, Z. Modelling sign language with encoder-only transformers and human pose estimation keypoint data. Mathematics 11, 2129 https://doi.org/10.3390/math11092129 (2023).

Tunga, A., Nuthalapati, S. & Wachs, J. Pose-based Sign Language recognition using GCN and BERT. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2012.00781 (2020).

Thomas, K. & Max, W. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805 (2018).

Matyáš, B. & Marek, H. Sign pose-based transformer for wordlevel sign language recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision 182–191 (2022).

Memari, M. & Taheri, A. Adaptive teaching of the Iranian sign language based on continual learning algorithms. IEEE Access 1-1 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3492056 (2024).

Özdemir, O., Baytaş, İ & Akarun, L. Hand graph topology selection for skeleton-based sign language recognition. 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1109/FG59268.2024.10581950 (2024).

Khan, K., Aslam, N., Abid, M. & Munir, S. Robot assist sign language recognition for hearing impaired persons using deep learning. VAWKUM Trans. Comput. Sci. 11, 245-267 https://doi.org/10.21015/vtcs.v11i1.1491 (2023).

Li, Y., Han, M., Yu, J., Lin, C. & Ju, Z. Adversarial attacks on skeleton-based sign language recognition. International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Applications. 33-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6483-3_4 (2023).

Bhatt, R., Malik, K. & Indra, G. ASL detection in real-time using TensorFlow. IEEE International Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation. https://doi.org/10.1109/IATMSI60426.2024.10503138 (2024).

Saleh, A. et al. Multi-stream general and graph-based deep neural networks for skeleton-based sign language recognition. Electronics. 12, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12132841 (2023).

Zhang, M., Gao, Q. & Ju, Z. DHF-SLR: Dual-hand multi-stream fusion network for skeleton-based sign language recognition. 649-654. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICARM62033.2024.10715929 (2024).

Naz, N., Sajid, H., Ali, S., Hasan, O. & Ehsan, M.K. MIPA-ResGCN: a multi-input part attention enhanced residual graph convolutional framework for sign language recognition. Computers, Electrical Engineering. 112, 109009 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.109009 (2023).

Qi, Y., Pang, C., Liu, Y. & Lyu, L. Multi-stream Global-Local Motion Fusion Network for skeleton-based action recognition. Appl. Soft Comput. 145, 110536 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110536 (2023).

Xu, H., Zhou, Z. & Yu, M. SHuBERT: Self-supervised sign language representation learning via multi-stream cluster prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.16765. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.16765 (2024).

Elakkiya, R., Ruba Soundar, K. & others. Adaptive transformer-based deep learning framework for continuous sign language recognition and translation (ADTR). Mathematics 13, 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13060909 (2025).

Özkul, A., Altinel, B., Göksu, O., & Sari, Y. TSLFormer: A lightweight transformer model for Turkish sign language recognition using skeletal landmarks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.07890. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.07890 (2025).

Fang, W., Wang, X., Wu, Y. & Chen, X. Spike-SLR: An energy-efficient parallel spiking transformer for event-based sign Language Recognition. Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC). https://bmvc2024.org/proceedings/493/ (2024).

Feng, F., Li, R. & Wang, J. SignDiff: Diffusion models for American sign language production. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16082. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.16082 (2023).

Bragg, D., Bharadwaj, S. & Morency, L.P. Neural sign actors: Diffusion models for 3D sign language production from text. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.02702. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.02702 (2023).an

Li, X., Zhang, D., Li, M. & Dah-Jye, L. Accurate head pose estimation using image rectification and a lightweight convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2022.3144893 (2022).

Zingoni, A., Diani, M. & Corsini, G. Tutorial: Dealing with rotation matrices and translation vectors in image-based applications: A common reference system for cameras. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 34, 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAES.2018.170100 (2019).

Damdoo, R. & Kumar, P. SignEdgeLVM transformer model for enhanced sign language translation on edge devices. Discov. Computing 28, 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10791-025-09509-1 (2025).

Das, S., Biswas, S. K. & Purkayastha, B. Hybrid feature based deep ensemble approach for Indian sign language recognition. Eng. Res. Express 7, 015275. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/adbb40 (2025).

Han, Y., Fan, X., Bhosale, R., Sundaram, R. & Liaw, J. Fusion-based spatiotemporal convolutions with constant temporal snapshots for sign language recognition. 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition. 01-08. https://doi.org/10.1109/FG52635.2021.9666973 (2021).

Rastgoo, R., Kiani, K., Escalera, S. & Sabokrou, M. Multi-modal zero-shot sign language recognition. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2109.00796 (2021).

Sijie, Y., Yuanjun, X. & Dahua, L. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 32, https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v32i1.12328 (2018).

Mercanoglu, O. & Keles, H. AUTSL: A large scale multi-modal Turkish sign language dataset and baseline methods. IEEE Access. 8, 181340–181355. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3028072 (2020).

Li, D., Rodríguez, C., Yu, X. & Li, H. Word-level deep sign language recognition from Video: A new large-scale dataset and methods comparison. arXiv:1910.11006. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1910.11006 (2019).

Funding

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il – Saudi Arabia through project number RG-24 128.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. and L.T. Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization. and M.J. and O.G. Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harrouch, H., Trabelsi, L., Jebali, M. et al. A deep learning-based method combines manual and non-manual features for sign language recognition. Sci Rep 16, 2981 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32768-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32768-3