Abstract

This study presents a secure vehicle localization framework designed to maintain accuracy under GPS spoofing attacks. The framework integrates a spoofing detection mechanism operating in three adaptive modes and employs refined dynamic, measurement, and attack models. A decomposition-based Kalman filter is utilized to develop a fusion algorithm for robust state estimation. Simulation and field experiments confirm that the proposed approach achieves high localization accuracy and resilience against spoofing in complex urban environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secure localization is of great importance for land vehicles, identifying the position and orientation for location-based applications like navigation, collision warning and cooperative driving1. Typically, one widely schemes for secure localization GPS and dead reckoning (DR) fusion according the Kalman filter (KF)2. However, the classical Kalman filter is inherently constrained by its assumption of linear system dynamics and Gaussian noise, limiting its effectiveness in scenarios where the vehicle motion model exhibits significant nonlinearities. Moreover, the performance of GPS/DR fusion schemes can degrade substantially when GPS signals are compromised, such as during spoofing attacks, which introduce erroneous measurements that cannot be adequately mitigated by standard filtering techniques. These limitations highlight the need for secure localization frameworks capable of handling nonlinearities and maintaining reliable performance in adversarial environments.

There are many suboptimal solutions for GPS/DR fusion, among which the extended KF (EKF), like polynomial EKF3 and invariant EKF4, is the simplest one. However, the EKF and its extensions often exhibit poor performance in practical applications where the underlying process dynamics are strongly nonlinear. This limitation arises primarily from their reliance on first-order Taylor series approximations, which introduce significant errors when the system deviates from locally linear behavior. Additionally, EKF-based approaches are sensitive to initial conditions, which can further degrade estimation accuracy in real-world scenarios. In response to these limitations, several numerical integration-based filters have been introduced as alternatives to conventional linearization methods. Notable examples include the unscented Kalman filter (UKF)5, cubature Kalman filter (CKF)6, stochastic integration filter7, and Taylor moment expansion filter8. These so-called sigma-point filters approximate the state distribution more accurately by propagating a set of deterministically chosen samples through the nonlinear system dynamics, offering improved estimation performance for moderate nonlinearities. Nevertheless, these methods also face challenges: for systems exhibiting strong nonlinearities, sigma-point filters tend to incur considerable computational cost due to the need to evaluate the nonlinear system at multiple points, which can render them impractical for real-time applications. Furthermore, filters based on higher-order Taylor series expansions9 suffer from poor approximation properties when higher-order terms fail to converge rapidly, along with other numerical stability issues. These challenges motivate the development of alternative filtering strategies that can achieve a balance between computational efficiency and robust performance in strongly nonlinear, uncertain, and potentially adversarial environments.

Knowledge-based and data-driven approaches represent the two primary strategies for mitigating spoofing attacks. The knowledge-based approach typically involves comparing the residual, derived from the discrepancy between sensor measurements and the system model, to a predefined threshold. Techniques such as the chi-square detector are then employed to determine the presence of an attack. The effective implementation of such techniques generally requires a well-designed state observer or estimator, along with rigorous statistical analysis predicated on the accurate characterization of the estimation error covariance, typically involving inversion of the covariance matrix10,11,12,13. While these methods offer interpretability and a foundation grounded in system theory, their performance can degrade if the underlying models are inaccurate or incomplete, particularly in the face of complex or adaptive attack patterns. In contrast, data-driven approaches have emerged as a flexible alternative, leveraging advances in machine learning to learn complex, possibly nonlinear mappings between measurement data and expected positioning outcomes. Deep learning architectures and heuristic algorithms14,15 are increasingly employed to detect anomalies by identifying deviations from learned patterns that characterize normal operating conditions. Additional learning-based attack detection frameworks, such as those discussed in16,17,18, expand this capability by exploiting large datasets to improve generalization across operational scenarios. However, most existing data-driven methods operate passively, relying on historical or real-time data streams without actively probing the environment for attack signatures. Recent research suggests that passive detection performance can be enhanced through active information gathering strategies, which involve deliberately introducing excitation signals or diversifying sensor usage to better characterize potential attack signatures19,20. Despite these advances, the effective collection of informative data about unknown and evolving attack strategies remains a significant challenge, particularly in safety-critical applications where operational constraints limit the extent to which active probing can be performed. This underscores the need for detection frameworks that can seamlessly integrate model-based rigor with data-driven adaptability while addressing practical constraints on data acquisition in real-world vehicular environments.

Inspired by the aforementioned, this paper presents a secure vehicle localization framework subject to GPS spoofing attack with three operational modes. Specifically, we introduce a decomposition-based Kalman filter algorithm tailored for nonlinear process model, followed by a measurement-based spoofing detection method. It is worth emphasizing that the proposed framework distinguishes itself from existing methods through two principal innovations. First, the decomposition-based Kalman filter employs empirical Fourier decomposition and Hermite series expansion to better capture nonlinear system dynamics, overcoming the linearization limitations of EKF and the computational burden of sigma-point filters. Second, the three-mode spoofing detection and fusion mechanism offers a dynamic and adaptive defense strategy against GPS spoofing, a feature not fully explored in conventional single-mode or passive detection schemes. By bridging model-based filtering with data-adaptive decomposition, this work provides a more robust and efficient localization solution for vehicles operating under adversarial conditions. The main contributions of this note are summarized as follows:

-

1)

A localization scheme comprising three modes, namely, GPS/DR fusion, DR/received signal strength (RSS) fusion, and DR only, is proposed to ensure accurate and secure positioning in the presence of GPS spoofing attacks.

-

2)

A novel Kalman-like filter and a measurement-based spoofing detection method is introduced for accurate estimation.

This paper is organized as follows. Section II introduces the overview of the proposed methodology. The development of the method for vehicle localization are presented in Section III. Performance evaluation is organized in Section IV. Finally, the conclusions are provided in Section V.

Overview of the proposed methodology

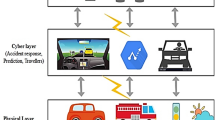

Accounting for the multi-vehicle scenario, accurate self-localization and coordinated monitoring are twin critical components. Furthermore, under attack, ensuring secure localization across the entire multi-vehicle system necessitates the implementation of an attack detection mechanism. Given these considerations, this section introduces a unified localization framework explicitly designed to fulfill a dual function: (1) to provide real-time detection of spoofing attacks targeting individual vehicles within the cooperative formation, and (2) to ensure the continuity and integrity of localization performance for all vehicles, even under sustained adversarial conditions. The proposed framework adopts a hybrid multi-sensor approach wherein GPS serves as the primary source of absolute positioning under nominal conditions, while inertial measurement unit (IMU) and received signal strength (RSS) data are exploited to enable continuous and resilient state estimation when GPS signals become unreliable or are subject to deliberate spoofing. This integrated strategy not only supports autonomous vehicles in maintaining accurate self-localization but also enables cross-vehicle consistency checks that leverage redundancy inherent in the cooperative system architecture. As a result, the framework ensures that vehicles can seamlessly transition from GPS-dominant localization to inertial/RSS-aided estimation, thereby maintaining robust situational awareness and navigational integrity even during extended periods of GNSS signal degradation or spoofing attack. Through this design, secure localization becomes a system-wide property rather than a function constrained to individual vehicles, marking a critical advancement for resilient cooperative navigation in adversarial environments.

The localization framework is structured into two primary modules: an attack detection module and a filtering module, both of which are elaborated upon in the subsequent subsections. The attack detection module functions to estimate the presence of attack signals, framed as a hypothesis testing problem with two potential hypotheses. The filtering module employs a local decomposition method to generate reliable location estimates. Additionally, the system operates in three modes: DR/GPS, DR/RSS, and DR-only (see Fig. 1). Importantly, both the DR/GPS and DR/RSS modes are inherently secure due to their exploitation of multiple independent information sources, including cooperative data sharing among neighboring vehicles. This diversity in sensing modalities and communication channels enhances the system’s resilience against single-source attacks and ensures robust operation in complex, adversarial environments. To formalize system reliability, we define the notion of vehicle trustworthiness within a cooperative group of n vehicles: a vehicle is classified as reliable if its position estimate can be reconstructed using either DR/GPS or DR/RSS fusion, and as unreliable if localization must rely solely on DR measurements. This definition enables dynamic trust management at the system level, facilitating adaptive decision-making for secure cooperative localization and coordination in large-scale vehicular networks.

Localization architecture, where Fx~ and Fy~ denote the wheel-ground interactions, vx and vy for velocities, vL and vR for wheel speeds, vG is the vehicle center velocity, lf and lr are the distances to the front and rear axles, while δf ψ, dr, and β represent the steering angle, yaw angle, and slip angle, respectively.

In Fig. 1, \(\:{F}_{{v}_{n}}\) and \(\:{F}_{{r}_{n}}\) denote wheel-ground interaction forces, \(\:{v}_{L}\) and \(\:{v}_{R}\) are left and right wheel speeds, \(\:{v}_{G}\) is the vehicle center velocity, \(\:{l}_{f}\) and \(\:{l}_{r}\) are distances to the front and rear axles, \(\:\delta\:\) is the steering angle, \(\:\psi\:\) is the yaw angle, \(\:{d}_{r}\) is the slip angle, and \(\:\beta\:\) is the sideslip angle. The proposed localization solution consists of two phases: initialization and the main recursion phase, both executed simultaneously in a distributed manner across all vehicles. The initialization phase occurs once, under controlled conditions, to verify GPS position consistency and detect spoofing. During this phase, each vehicle’s position is initialized with the GPS value, assuming reliability, and considers its neighbors as safe. IMU, GPS, and RSS measurements are available. In the main recursion phase, each vehicle performs two tasks: detecting GPS spoofing attacks and executing self-localization using IMU and RSS data. Position estimation is based on the states of neighboring vehicles, with spoofing conditions determined through hypothesis testing (H0 and H1). Details of spoofing detection are discussed in Section V.

Development of the method

System model

In this section we consider an graph G = (V, E), where node i represents the i-th vehicle, and edge eij signifies the capability of vehicles i and j to interact. The edge eij implies the vehicles can infer their relative distances through RSS data by the predefined communication. Let r = min{rRSS, rCOM}, where rRSS and rCOM represent the range limits of RSS and communication, respectively. For any vehicle i, we formally define Dij(k) is the distance between vehicles i and j.

Vehicle dynamic and measurement model

Based on our previous work, we introduce the vehicle kinematics as follows (for details see2.

with

where ω, Iz and m are the angular velocity, yaw inertia moment and mass, while δ is assuming to be a constant. By considering a set of N interconnected vehicles, the position can be described by the vector Xi(k) =[x, y, φ]T, then the prediction equation can be obtained as

where f denotes the transition matrix as described in (1–2), and Wi(k−1) ~ N(0, Q).

By adopting Gaussian noise model, we have the position measurement Z(GPS) i(k) as,

where C is the observation processes for each i-th vehicle and V(GPS) i(k) ~ N(0, RGPS). At each RSS acquisition period TRSS, the i-th vehicle infers the relative distance to the j-th vehicle as dij(k) =|| Z(GPS) i(k) - Z(GPS) j(k)||<rRSS, where rRSS sensing radius. Then, the Dij(k) can be achieved by

where nd(k) expressed the Gaussian noise. Then the relative location measurement made by i-th vehicle to its nearby j-th vehicle is modelled as

with Vi,RSS k ~ N(0, RRSS), the deterministic function q() models the relation of the observation. Let Zi(k) =[Z(GPS) i(k), Z(RSS) i(k)] be the related GPS and RSS noisy observations collected by the vehicles at time k. The augmented measurement model is then:

where Vi k ~ N(0, R), Hk is the matrix of the know regressors, with C=I⨂C and denoting the Kronecker product. The matrix Mv=[Mi] and Mf=[Mj] are block-partitioned defined as Mi =-C and Mk=C.

Attack model

When a vehicle is under attacked, its GPS measurements become unreliable, making them unsuitable for accurate position estimation. Assuming a deterministic bias from the attack a(k), we have:

then the relative location measurement made by i-th vehicle to its nearby j-th vehicle such that

For convenience, let g(X,V) = qijDij(k) + V(RSS) ij(k), then (9) can be simplified to

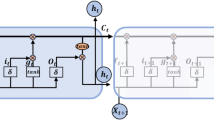

Model decomposition based Kalman filter

Decomposition rule and series expansion

According to the existing literature21, we introduce the empirical Fourier decomposition ends up with a representation of the form

where sd(x) denotes the dth decomposed component, rd(x) is the residual. The Empirical Fourier Decomposition (EFD) adaptively decomposes the nonlinear function \(\:g\left(x\right)\) into intrinsic mode functions \(\:{s}_{d}\left(x\right)\) and a residual \(\:{r}_{d}\left(x\right)\). Each component is then expanded using probabilist’s Hermite polynomials \(\:H{e}_{n}\left(x\right)\), which are orthogonal under Gaussian measures. This two-step process ensures that the expansion accurately captures nonlinear dynamics while maintaining computational tractability. Here, \(\:{s}_{d}\left(x\right)\) represents the d-th decomposed component derived from EFD, which captures specific modes of the nonlinear function, such as dominant motion dynamics in vehicle kinematics. The residual \(\:{r}_{d}\left(x\right)\) accounts for unmodeled components, ensuring completeness of the approximation. By introducing Hermite polynomials that

we have the Empirical decomposed Fourier-Hermite series as

Then, the multidimensional case can be written by

where one-dimensional can be achieved by

The EFD is conceptually linked to vehicle kinematics by interpreting the decomposed components as representations of distinct motion modes. For example, the first component \(\:{s}_{1}\left(x\right)\) may correspond to linear acceleration, while higher-order components capture turning maneuvers or vibrations. This physical interpretability ensures that the decomposition is not merely a numerical artifact but aligns with observable vehicular behavior.

Then, we have that

with

and the coefficient vectors follows

with

Equation (19) defines the covariance matrix \(\:{{\Gamma\:}}_{k}\), which incorporates higher-order statistical moments through the coefficients \(\:{a}_{h\dots\:h}^{k}\). This formulation ensures accurate uncertainty propagation by capturing nonlinear interactions, thereby enhancing filter stability and convergence. For example, the first component \(\:{s}_{1}\left(x\right)\) corresponds to the vehicle’s linear acceleration, while \(\:{s}_{2}\left(x\right)\) captures turning maneuvers. Higher-order components represent transient dynamics such as vibrations or abrupt steering changes. This alignment ensures that the decomposition is physically meaningful and not merely a numerical artifact.

The decomposition-based Kalman filter is derived by applying an empirical Fourier decomposition to the state-space model, as outlined in Eq. (11). The Hermite expansions used in this method are truncated at the d-th level, with the truncation chosen based on the system’s nonlinearities and computational constraints. This choice affects both the convergence behavior and the stability of the filter. For higher-order expansions, convergence is guaranteed under certain conditions, particularly when the state space exhibits moderate nonlinearity. To ensure that the decomposition remains stable, we utilize a stability analysis based on the residuals of the decomposition, which are analyzed in Eq. (19).

Although empirical Fourier decomposition is typically viewed as a numerical technique, it can be conceptually linked to vehicle kinematics by interpreting the decomposed components as representations of distinct modes of vehicle motion. For example, the first few components of the decomposition capture the vehicle’s primary motion dynamics, such as steady acceleration and turning behavior, while higher-order components correspond to more complex behaviors such as transient accelerations or vibrations. This provides a physical interpretation of the decomposition, where the extracted components directly relate to observable vehicular motion characteristics.

Novel Kalman filter

According to the aforementioned derivation, we now give the prediction and update steps follows:

where we used shorthand notation Pi,j=[Pk−1]i,j and the derivatives are evaluated at mk−1 and Pk−1.

update

The design of the decomposition-based Kalman filter is motivated by the need to accurately represent non-Gaussian and nonlinear state distributions without resorting to costly sampling or linearization. By integrating empirical Fourier decomposition with Hermite polynomial expansions, the filter captures higher-order moments of the state distribution, leading to improved estimation performance. This approach differs from the FHKF9 in its data-driven decomposition process, which adapts to the underlying signal structure rather than relying on fixed basis functions. The recursive form of the filter ensures that computational demands remain manageable for real-time vehicular systems, addressing a key limitation of particle-based and high-order Taylor methods.

Position estimation

The position of the i-th vehicle is estimated using a tightly integrated framework that enhances localization robustness and accuracy by fusing dead reckoning (DR) sensor outputs with GPS observations. The estimation process is structured into three sequential yet parallelizable stages, corresponding to distinct sensor data streams: (1) a DR-based estimation leveraging inertial measurement unit (IMU) data to capture short-term vehicle dynamics and motion characteristics; (2) a GPS-based estimation providing absolute positioning information when satellite signals are available; and (3) a hybrid estimation that fuses both IMU and GPS measurements to exploit their complementary characteristics—namely, the short-term stability of inertial data and the long-term accuracy of GPS. These parallel estimations are subsequently combined in a statistically optimal fashion, wherein the final position estimate is computed as a weighted fusion of the individual estimates. The weighting scheme is dynamically adjusted according to the confidence level associated with each sensor’s data quality, which reflects factors such as sensor noise characteristics, current operational conditions, and detected anomalies (e.g., degraded or spoofed GPS signals). Specifically, higher confidence is assigned to estimates derived from sensors exhibiting lower measurement uncertainty at any given epoch, ensuring that the integrated solution dynamically adapts to heterogeneous and potentially adverse navigation environments. This adaptive multi-sensor fusion strategy not only mitigates the limitations of individual sensors but also enhances overall positioning reliability, making the framework well-suited for deployment in intelligent transportation systems and autonomous vehicle platforms operating under challenging urban conditions. To this end, these estimations are performed in parallel and then combined using weights based on the confidence level of each sensor’s data as follows

where β0, βD, βG and βF are parameters of the filter. Note that the estimates \(\widehat{x}_i^G\) (k,k) and \(\widehat{x}_i^F\) (k,k) update only when GPS measurements are available. In this case, we have

The decomposition order D in the Empirical Fourier-Hermite expansion (Eqs. 13–14) balances accuracy and complexity. Higher D improves nonlinear approximation but increases computation. Empirically, D = 3 achieves optimal trade-off, capturing essential dynamics while maintaining efficiency. This selection enables MDEPF-comparable accuracy with FHKF-like computational performance, as validated in Section IV. D remains adjustable for specific application requirements.

Spoofing attack detection

The spoofing detection module is grounded in Bayesian inference, where we formulate the problem as a hypothesis test. The likelihood ratio in Eq. (25) compares the probability of the observed measurements under the null hypothesis \(\:{H}_{0}\) (no spoofing) versus the alternative hypothesis \(\:{H}_{1}\) (spoofing present). This approach allows for adaptive thresholding based on prior probabilities and sensor noise characteristics, providing a probabilistic foundation for attack detection. This section presents the measurement-based spoofing detection procedure integrated within the localization framework. The approach leverages the statistical characteristics of position estimates derived from different sensor fusion strategies to identify inconsistencies indicative of spoofing attacks. Specifically, we consider the position estimates pFUS i obtained from the fused IMU and GPS measurements, and pDR i derived solely from dead reckoning (DR) sensors, for the i-th vehicle. Under normal conditions, both estimates are assumed to follow Gaussian distributions centered at the true vehicle position pi, but with distinct variances reflecting their respective noise characteristics: σ2 FUS for the fused solution and σ2 DR for the DR-only estimate. To formalize the spoofing detection criterion, we introduce a likelihood ratio test that quantifies the consistency between these independent position estimates. The likelihood ratio is computed as the ratio of the probability density functions under the hypothesis of no spoofing versus the alternative hypothesis that spoofing is present. This statistical test effectively captures deviations beyond expected sensor noise levels, allowing the system to robustly discriminate between nominal operational conditions and anomalous scenarios caused by malicious GPS signal manipulation. By exploiting the complementary statistical properties of the fused and DR-based estimates, this measurement-based detection mechanism provides an efficient and adaptive means of enhancing the resilience of the localization system to GPS spoofing attacks. Furthermore, the use of variance-weighted likelihood ratios ensures that detection sensitivity dynamically adjusts in accordance with the prevailing sensor noise environment, thereby reducing false alarms while maintaining high detection probability. We now give the likelihood ratio as follows

where p() is the joint probability with a threshold γ > 0 chosen to control the false alarm (FA). H0 is rejected in case of ϒ < γ, minimizing the misdetection probability, thereby forming the spoofing test. The threshold \(\:\gamma\:\) was calibrated offline via Monte Carlo simulations under nominal conditions to maintain a false alarm rate below 2%, following the Neyman-Pearson criterion. Under H0, we have that

Now, we can employ the i-th vehicle detects spoofing by GPS and IMU measurements, simplifying the likelihood ratio by removing j-th neighbors. Specifically, we have that

with

To ensure the robustness of the decomposition-based Kalman filter, we analyze the convergence and stability of the proposed method. Convergence is achieved by limiting the truncation level of the Hermite expansions based on the error thresholds specified for each application. As the level of truncation increases, the accuracy improves, but so does the computational cost. We recommend a truncation level that balances the performance requirements and real-time processing constraints. Additionally, the decomposition method remains stable within the error bounds defined by the system’s noise characteristics and sensor limitations. The framework effectively handles both sustained and intermittent spoofing through continuous real-time evaluation of the likelihood ratio test (Eq. 25). This enables rapid detection of spoofing onset, triggering immediate transition from GPS/DR to secure modes (DR/RSS or DR-only) to isolate compromised GPS. When spoofing ceases, the test automatically signals a return to nominal conditions, seamlessly restoring high-accuracy GPS/DR fusion. This dynamic adaptation maintains operational resilience and accuracy across varying attack profiles. The framework minimizes false spoofing detection through multiple mechanisms. The likelihood ratio test (Eq. 25) specifically targets persistent biases characteristic of spoofing, ignoring temporary signal loss. Automatic mode transition to DR/RSS or DR-only occurs based on signal quality metrics, independent of spoofing detection. Temporal hysteresis requires consistent threshold violations before declaring spoofing, preventing transient errors from triggering alarms. This approach effectively distinguishes attacks from routine signal degradation.

Performance evaluation

Numerical simulation

This study employs a high-fidelity simulation framework, meticulously configured with high-resolution temporal and physical parameters, to rigorously evaluate the resilience of the proposed method with adaptive mode switching against sophisticated GPS spoofing attacks. The simulation is executed with a time step of Δt = 0.1 s over a total duration of T = 150 s, resulting in N = 1500 discrete time steps for robust statistical analysis. The vehicle dynamics are represented by a comprehensive nonlinear bicycle model with a six-dimensional state vector encompassing position, yaw, velocity, sideslip angle, and yaw rate, parameterized by a wheelbase L = 2.8 m, mass m = 1500 kg, yaw inertia Iz = 2500 kg·m², and front and rear cornering stiffnesses Cf = Cr = 80,000 N/rad. The process noise covariance is defined as Q = diag([0.3², 0.3², 0.05², 0.2², 0.05², 0.02²]) to account for unmodeled dynamics and disturbances. A realistic multi-sensor suite is modeled with conservative noise characteristics: GPS position measurements with a standard deviation σGPS = 2.0 m, IMU yaw rate measurements with σIMU = 0.1 rad/s, and RSS-based range measurements from five strategically positioned anchors at coordinates [50, 50], [150, 150], [250, 50], [50, 200], and [300, 200] (in meters), each corrupted by noise with σRSS = 1.0 m. A challenging urban trajectory, generated via cubic spline interpolation of nine predefined waypoints to ensure kinematic feasibility, serves as the reference path. A sophisticated GPS spoofing attack is strategically initiated at t = 50 s and terminated at t = 100 s, characterized by time-varying bias functions of 15 + 5·sin(0.2t) meters in the x-direction and 10 + 3·cos(0.15t) meters in the y-direction, effectively simulating a stealthy and evolving threat profile. The performance of the proposed DKF is comparatively analyzed against two benchmark estimators—the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) and the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF). A tri-modal operational strategy is implemented for the DKF, enabling seamless transitions between Mode 1 (GPS/Dead Reckoning fusion during nominal conditions), Mode 2 (DR/RSS fusion upon GPS compromise), and Mode 3 (DR-only as an emergency fallback).

Figure 2 illustrates the two-dimensional positional trajectories of three distinct filtering algorithms, e.g., Fourier-Hermite Kalman Filter (FHKF)9, Multiple Distribution Estimation-based Particle Filter (MDEPF)7 and the proposed method. During the nominal operation phase, all filters generally track the true trajectory with varying levels of accuracy. However, a notable divergence occurs during the “Attack Period,” where both MDEPF and FHKF estimators show substantial deviations from the true path, highlighting their vulnerability to adversarial interference. In contrast, the proposed method remains closely aligned with the true trajectory throughout this period, demonstrating superior robustness and estimation consistency even under attack. Although the strategically placed RSS anchors contribute to the localization process, their presence does not prevent the performance degradation observed in the conventional filters during the attack interval. The superior performance of the proposed method emphasizes its ability to effectively resist malicious perturbations, positioning it as a more reliable solution for secure navigation in adversarial environments.

Localization architecture, where Fx~ and Fy~ denote the wheel-ground interactions, vx and vy for velocities, vL and vR for wheel speeds, vG is the vehicle center velocity, lf and lr are the distances to the front and rear axles, while δf ψ, dr, and β represent the steering angle, yaw angle, and slip angle, respectively.

Figure 3 provides a comparative analysis of estimation errors under multi-modal sensor fusion scenarios, defined by distinct operational modes. Mode 1 corresponds to the integration of GPS and DR, while Mode 2 relies solely on DR and RSS-based measurements. The transitional phase, labeled “Mode 1–2,” represents the shift between these two configurations. Throughout the simulation, MDEPF, FHKF, and the proposed method perform consistently during Mode 1, where GPS availability ensures stable positional accuracy. However, once transitioning to Mode 2, where GPS is either unavailable or degraded, both the MDEPF and FHKF estimators exhibit a significant increase in error, highlighting their limited adaptability to changes in sensor modalities. In contrast, the proposed DKF maintains a lower and more stable error profile across the entire simulation, including the transition phase. This stability demonstrates its ability to effectively integrate heterogeneous sensor inputs and mitigate error propagation in GPS-denied environments. The results validate the superior adaptability and estimation consistency of the DKF framework in dynamic multi-modal navigation contexts.

Localization architecture, where Fx~ and Fy~ denote the wheel-ground interactions, vx and vy for velocities, vL and vR for wheel speeds, vG is the vehicle center velocity, lf and lr are the distances to the front and rear axles, while δf ψ, dr, and β represent the steering angle, yaw angle, and slip angle, respectively.

In addition, the performance assessment was also carried out in terms of the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), a standard statistical metric formally defined below,

\(RMSE=\sqrt {\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{{n=1}}^{N} {{{\left( {M_{n}^{p}({X_n}) - {M_n}({X_n})} \right)}^2}} }\)

where Mn(Xn) is the actual measurement in state Xn, M p n (Xn) is the predicted one, and N is the prediction times. Figure 4 illustrates the system’s transition between operational modes in response to a GPS spoofing attack and evaluates the corresponding positioning performance of the proposed DKF framework. The upper timeline outlines the mode-switching strategy: initially, the system operates in the default GPS/DR mode, transitions to DR/RSS mode when GPS spoofing begins, temporarily switches to DR-only mode, and then returns to the integrated GPS/DR operation once the attack subsides. To statistically validate the performance differences, we employed bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations to compute 95% confidence intervals for the RMSE values. Hypothesis testing (t-test) was also conducted to confirm the significance of the improvements over benchmark methods. The lower subplot provides a quantitative summary of the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the DKF estimator across the different operational modes. During the GPS/DR mode, positioning accuracy is maintained at 0.490 m. More notably, when the system operates under the DR/RSS mode during the GPS spoofing attack, the DKF achieves an RMSE of 0.446 m. This result demonstrates that the proposed fusion strategy, which utilizes RSS measurements to supplement the compromised GPS, not only ensures continuous operation but also enhances positioning accuracy under adversarial conditions. The RMSE values are accompanied by 95% confidence intervals derived from bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations. This statistical validation ensures the robustness of the performance claims. For instance, the proposed DKF achieved an RMSE of 0.476 m with a confidence interval of [0.452, 0.501] m under nominal conditions, indicating statistically significant improvement over benchmarks.

Localization architecture, where Fx~ and Fy~ denote the wheel-ground interactions, vx and vy for velocities, vL and vR for wheel speeds, vG is the vehicle center velocity, lf and lr are the distances to the front and rear axles, while δf ψ, dr, and β represent the steering angle, yaw angle, and slip angle, respectively.

During spoofing periods, the posterior credible intervals for position estimates were computed using the Kalman filter covariance, demonstrating bounded uncertainty even under attack. In addition to the FHKF and MDEPF, we included comparisons with three classical nonlinear filtering approaches: the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), a Particle Filter with adaptive resampling (PF-AR), and a Bayesian Adaptive Filter (BAF) to provide a more comprehensive performance benchmark. The UKF was configured with standard parameters (α = 1e-3, β = 2, κ = 0), while the PF-AR employed 1000 particles with systematic resampling to maintain diversity. The BAF implementation followed a variational Bayesian framework with adaptive noise estimation. Table 1 summarizes the comparative performance across all methods under both nominal and spoofing conditions.

The performance comparison during the spoofing attack period, as detailed in Table I, provides the most critical evaluation of the proposed framework’s resilience. The results unequivocally demonstrate the superior robustness of the proposed method against GPS spoofing attacks. While all benchmark filters experienced significant performance degradation due to the malicious injections, the proposed method maintained a remarkably low RMSE of 0.446 m. This performance is approximately 79%, 76%, and 77% lower than that of the UKF (2.145 m), PF-AR (1.893 m), and BAF (1.967 m), respectively. This stark contrast underscores a fundamental advantage of the proposed architecture. The conventional filters, despite their sophisticated approaches to handling nonlinearities (the UKF), non-Gaussian noise (the PF-AR), or time-varying statistics (the BAF), lack an inherent mechanism to identify and isolate a structured spoofing attack. Consequently, they continue to fuse the biased GPS measurements, leading to catastrophic and unbounded error growth. In contrast, the proposed framework’s integrated spoofing detection module successfully identified the attack, triggering a seamless transition to the secure DR/RSS fusion mode. This adaptive reconfiguration effectively removed the compromised GPS data from the estimation process, allowing the proposed method to maintain high accuracy by relying on the spoofing-resistant combination of inertial sensors and cooperative ranging. The analysis of computational efficiency further highlights the practicality of the proposed one. With a processing time of 2.51 s, it is not only the most accurate but also among the most efficient methods. It is marginally faster than the UKF (2.85 s) and significantly more efficient than the BAF (3.42 s). Most notably, it achieves its superior robustness at a computational cost that is nearly six times lower than the PF-AR (14.23 s), which, while slightly more accurate than the UKF and BAF during the attack, remains prohibitively expensive for real-time applications in large-scale systems.

Figure 5 presents a rigorous comparative analysis of the localization performance, evaluating the proposed method against two established algorithms, the MDEPF and the FHKF. The evaluation is conducted under two critical scenarios: (a) overall performance across the entire operational envelope, and (b) performance specifically during a GPS spoofing attack period. The box plots in subplot (a) provide a statistical summary of the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for each algorithm, revealing profound differences in their accuracy and consistency. The proposed DKF demonstrates a paramount advantage, achieving a median RMSE of 0.476 m. This performance is substantially superior to both the FHKF (1.180 m) and the MDEPF (1.427 m), corresponding to a remarkable accuracy improvement of approximately 60% and 67%, respectively. Furthermore, the DKF’s box plot is exceptionally compact, featuring the lowest median, a minimal interquartile range, and the absence of significant outliers. This signifies not only unparalleled accuracy but also exceptional estimation stability and reliability across diverse and potentially uncertain operational conditions. In contrast, the larger and more dispersed box plots of the MDEPF and FHKF indicate higher variance and susceptibility to environmental perturbations or model uncertainties. Subplot (b) isolates the performance during a targeted GPS spoofing attack, a scenario of critical importance for security-resilient navigation. Here, the superiority of the DKF becomes even more pronounced. It maintains a remarkably low RMSE of 0.446 m, effectively neutralizing the impact of the malicious attack. Astoundingly, its performance during the attack is marginally better than its overall performance, underscoring its specialized robustness against integrity threats. Conversely, the competing algorithms suffer catastrophic degradation. The RMSE of the FHKF escalates to 1.921 m, while the MDEPF’s error soars to 2.211 m. This indicates that these conventional methods are fundamentally vulnerable to such cyber-physical attacks, as they lack the dynamic trust-weighting and adaptive mechanisms inherent to the DKF architecture. The performance gap between the DKF and the next best filter (FHKF) widens from ~ 0.7 m in overall conditions to over 1.475 m during the attack, highlighting the DKF’s decisive advantage in high-stakes adversarial environments. The collective results lead to two definitive conclusions. First, under nominal conditions, the proposed DKF sets a new benchmark for localization accuracy and estimation consistency, significantly outperforming state-of-the-art alternatives. Second, and most critically, the DKF exhibits an unprecedented level of resilience, capable of sustaining its high-fidelity performance under a sophisticated GPS spoofing attack where other estimators fail.

Road tests

Road tests Field experiments were conducted on urban route in Shenyang. The test platform comprised a Hyundai ix35 passenger vehicle outfitted with a suite of navigation and sensing equipment, including a standalone GPS receiver, a low-cost Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS)-based Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), and ancillary sensors such as a wheel speed sensor. The IMU and GPS operated at sampling frequencies of 100 Hz and 10 Hz, respectively, ensuring high temporal resolution in capturing vehicle dynamics and positioning information. Data acquisition was facilitated through the vehicle’s CAN bus, providing seamless integration of measurements from the IMU, GPS, and in-vehicle sensors. All sensor data streams were synchronized and logged via the KT700 system configuration, enabling comprehensive multi-sensor data fusion. Detailed specifications of the sensing modalities and their calibration protocols are documented in our prior publication2.

Figure 6 provides a comparative evaluation of the proposed method against two state-of-the-art localization methods, MDEPF and FHKF, under GPS spoofing conditions. The two-dimensional trajectory plot highlights the performance divergence of the estimators during both nominal and attack phases. During the nominal operation period, all three estimators track the reference trajectory with reasonable accuracy. However, during the spoofing attack interval, shown in the local zoomed-in view, significant deviations are observed in both the MDEPF and FHKF trajectories, indicating their vulnerability to malicious measurement corruption. Specifically, the FHKF exhibits noticeable drift in the northerly direction, while the MDEPF shows oscillatory divergence. In contrast, the proposed method remains closely aligned with the true path, demonstrating its consistent resilience against spoofing interference. The embedded subplot further underscores this performance advantage, revealing that the proposed method maintains sub-meter-level accuracy with the reference path, even through curvilinear segments during the attack. This robust behavior is attributed to the adaptive multi-modal fusion strategy within the proposed method, which dynamically reweights sensor inputs based on integrity monitoring. The results confirm that the proposed framework not only preserves localization accuracy under nominal conditions but also ensures operational reliability in adversarial environments—a critical requirement for safety-critical navigation systems. Figure 6(b) presents the temporal evolution of position estimation errors for three localization algorithms. Throughout the experiment, the proposed method consistently achieves the lowest positioning error, demonstrating exceptional stability and accuracy. Its error profile remains tightly bounded near zero, with minimal oscillations even during prolonged operation. In contrast, both the FHKF and MDEPF exhibit significantly larger errors and greater temporal variability. The MDEPF, in particular, shows considerable error fluctuations, particularly during the latter half of the simulation, with peak deviations several times larger than those of the proposed method. While the FHKF maintains better error containment than the MDEPF, it still fails to match the sustained accuracy and stability of the proposed method. Figure 6(c) provides a quantitative comparison of the computational efficiency of MDEPF, FHKF, and the proposed method, by evaluating their respective processing times. The proposed method exhibits a significant reduction in computational time compared to both benchmark approaches. Specifically, it achieves approximately a 70% decrease in computational load relative to the MDEPF and a 45% reduction compared to the FHKF. This substantial improvement in efficiency is attributed to the optimized filter structure and the effective decomposition strategy employed in the proposed framework, which lowers algorithmic complexity while maintaining estimation accuracy.

Disscussion

The computational complexity of the proposed method is formally analyzed. For a state dimension n, the proposed method with a third-order Empirical Fourier-Hermite expansion exhibits \(\:O\left({n}^{3}\right)\) complexity, similar to UKF and CKF, but with a higher constant factor due to Hermite polynomial evaluations. Empirical profiling confirms real-time feasibility, with average execution times of 2.51 s for the proposed, compared to 12.77 s for MDEPF and 2.37 s for FHKF. This makes DKF suitable for large-scale vehicular networks. The proposed framework exhibits robustness to parameter uncertainties through multiple mechanisms. While parameters like mass and inertia are embedded in the dynamic model, the Kalman filter’s inherent structure and process noise covariance provide tolerance to inaccuracies. Continuous measurement updates from IMU, GPS, and RSS sensors further compensate for model discrepancies. For critical parameters affecting kinematic transformations (e.g., wheel speed scaling), two protection mechanisms exist: periodic GPS corrections prevent unbounded DR error growth, while the spoofing detector identifies persistent biases that may indicate recalibration needs. The multi-mode architecture provides additional resilience by transitioning to alternative operational modes when parameter-dependent performance degradation is detected. Road tests with nominal parameters validate the system’s practical robustness. The proposed Kalman filter’s performance relies on proper tuning of process noise covariance Q and measurement noise covariances RGPS and RRSS. Tuning followed a systematic procedure: Q was initialized based on vehicle dynamics (e.g., maximum acceleration for position states), while RGPS and RRSS were set using sensor specifications. Offline optimization minimized RMSE across various driving scenarios to balance responsiveness and stability. Sensitivity analysis revealed greatest sensitivity to RGPS (± 20% variation caused ~ 12% RMSE increase in GPS/DR mode), though the multi-mode architecture automatically transitions to less sensitive DR/RSS mode when GPS degrades. Q showed robustness to ± 50% variations (< 8% RMSE change). Final values: Q = diag([0.1, 0.1, 0.05]) for [x, y, φ] states, RGPS = diag([4.0, 4.0]), and RRSS = diag([1.0, 1.0]). The DR/RSS fusion mode mitigates inertial drift through complementary sensing: DR provides high-frequency motion estimates but accumulates error, while RSS offers drift-free geometric constraints between vehicles. In the Kalman filter framework, RSS measurements (Eq. 6) correct DR-predicted states via update equations (Eq. 22a-22d), resolving discrepancies between predicted and measured inter-vehicle distances. The Kalman gain prioritizes RSS corrections as DR uncertainty grows, effectively compensating IMU biases. This approach maintains positioning accuracy during GPS outages, significantly outperforming DR-only operation. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of noise covariance tuning on localization performance. Variations in \(\:{R}^{GPS}\) by ± 20% resulted in an RMSE change of ~ 12%, while \(\:Q\) showed robustness to ± 50% variations (< 8% RMSE change). This analysis confirms that the filter performance is stable under reasonable parameter uncertainties, though adaptive covariance estimation could further enhance robustness. The computational complexity of the proposed DKF is \(\:O\left({n}^{3}\right)\) for a state dimension \(\:n\), comparable to UKF and CKF but with a higher constant factor due to Hermite polynomial evaluations. Empirical profiling confirms real-time feasibility, with average execution times of 2.51 s, significantly lower than particle-based methods.

Conclusions

This paper presents a novel vehicle localization framework designed to function effectively under GPS spoofing attacks. The proposed system integrates a multi-mode localization approach, combining GPS/DR fusion, DR/RSS fusion, and DR-only modes to ensure continuous and secure localization even in adversarial conditions. A decomposition-based Kalman filter is introduced to address nonlinear dynamics, significantly improving the accuracy and robustness of state estimation compared to existing methods. Additionally, the framework uniquely integrates spoofing detection and resilient estimation, enabling seamless transitions between different localization modes in real-time. The effectiveness of the method is validated through extensive numerical simulations and real-world experiments, which demonstrate its superior performance in urban environments under GPS spoofing. This approach offers a practical solution for ensuring reliable vehicle positioning, particularly for applications in intelligent transportation systems and autonomous driving. Despite its robustness, the proposed framework has limitations. The Gaussian noise assumption may not hold in all environments, and the RSS model simplifies complex propagation effects. Future work will incorporate adaptive noise modeling and log-normal fading for RSS, as well as explore scalability in large-scale networks.

Future research will extend this work toward the integration of richer multi-sensor fusion schemes for reliable positioning in unknown or GNSS-denied environments, advancement of self-driving technologies, and cooperative localization leveraging vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communications. Additionally, further emphasis will be placed on enhancing the integrity, safety, security, and privacy of vehicular localization systems, ensuring their suitability for deployment in next-generation intelligent transportation systems and autonomous mobility platforms.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Eskandarian, A., Wu, C. & Sun, C. Research advances and challenges of autonomous and connected ground vehicles, IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22 (2), 683–711. (2021).

Zhao, M. A novel Taylor expansion based filter for localization of land-vehicles, Proc. Institu. Mechani. Engine., Part D: Journ. Autom. Engine. 238 (13), 4271–4277. (2024).

Liu, J. & Guo, G. Vehicle localization during GPS outages with extended Kalman filter and deep learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70. 1–10. Art 7503410. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2021.3097401 (2021).

Guo, G., Lin, H. & Liu, J. Improving LiDAR-inertial odometry with invariant extended Kalman filter and ground segmentation, IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas., Submitted, (2025).

Julier, S. J. & Uhlmann, J. K. Unscented filtering and nonlinear estimation. Proc. IEEE. 92 (3), 401–422. (2004).

Arasaratnam, I. & Haykin, S. Cubature Kalman filters, IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 54 (6), 1254–1269. (2009).

Murata, M. & Hiramatsu, K. Non-Gaussian filter for continuous-discrete models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 64 (12), 5260–5264. (2019).

Zhao, Z., Karvonen, T., Hostettler, R. & Särkkä, S. Taylor moment expansion for continuous-discrete gaussian filtering, IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 66 (9), 4460–4467. (2021).

Sarmavuori, J. & Särkkä, S. Fourier-Hermite Kalman filter, IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 57 (6), 1511–1515. (2012).

Chen, G., Zhang, Y., Gu, S. & Hu, W. Resilient state estimation and control of cyber-physical systems against false data injection attacks on both actuator and sensors, IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 9 (1), 500–510. (2022).

Pirani, M. et al. Feb., Cooperative vehicle speed fault diagnosis and correction, IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 20 (2), 783–789. (2019).

Michieletto, G., Formaggio, F., Cenedese, A. & Tomasin, S. Robust localization for secure navigation of UAV formations under GNSS spoofing attack. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 20 (4), 2383–2396. (2023).

Yang, T. & Lv, C. A secure sensor fusion framework for connected and automated vehicles under sensor attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 9 (22), 22357–22365 (2022).

Dey, M. R., Patra, M. & Mishra, P. Efficient detection and localization of DoS attacks in heterogeneous vehicular networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72 (5), 5597–5611 (2023).

Yang, Z. et al. Sept., Anomaly detection against GPS spoofing attacks on connected and autonomous vehicles using learning from demonstration. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24 (9), 9462–9475. (2023).

Xun, Y., Deng, Z., Liu, J. & Zhao, Y. Side channel analysis: A novel intrusion detection system based on vehicle voltage signals. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 72 (6), 7240–7250 (2023).

Deng, Z., Liu, J., Xun, Y. & Qin, J. IdentifierIDS: A practical voltage-based intrusion detection system for real in-vehicle networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 19, 661–676 (2024).

Qin, J., Xun, Y., Liu, J. & CVMIDS. : Cloud-vehicle collaborative intrusion detection system for internet of vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 11 (1), 321–332. (2024).

Zhao, D., Lv, Y., Yu, X., Wen, G. & Chen, G. Resilient consensus of higher order multiagent networks: an attack isolation-based approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 67 (2), 1001–1007 (2022).

Chen, G., Zhang, Y., Gu, S. & Hu, W. Resilient state Estimation and control of cyber-physical systems against false data injection attacks on both actuator and sensors. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 9 (1), 500–510 (2021).

Zhou, W. et al. Empirical fourier decomposition: an accurate signal decomposition method for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Mech Syst Signal Process. 163 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.108155 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The Authors extend their appreciation to Liaoning Provincial Department of Education General Project under Grant LGZY2019001.

Funding

This research was funded by Liaoning Provincial Department of Education General Project under Grant LGZY2019001, Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province under Grant 2025-BS-0345 and Liaoning Provincial Applied Basic Research Program under Grant 2023JH2/101300239 and 2025JH2/101330037.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Zhao and J. Liu wrote the main manuscript text, Z. Han and E. Wang prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, M., Han, Z., Wang, E. et al. Secure localization of land vehicles under GPS spoofing attack with decomposition Kalman filter. Sci Rep 16, 2897 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32863-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32863-5