Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of sedentary behavior among patients with knee osteoarthritis and its associated factors, providing a reference for developing future intervention programs to improve sedentary behaviour in this population. A total of 311 patients with knee osteoarthritis admitted to a tertiary hospital in Guizhou Province were enrolled in the study. Assessments were conducted using the following instruments: a sociodemographic questionnaire, Tampa Kinesiophobia Scale, Knee Function Scale, Social Support Scale, Fatigue Scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Results showed that the median daily sedentary time of the total sample was 5 h (range: 4–7 h), with 140 patients (45.0%) exhibiting ≥ 6 h/day of sedentary time. Logistic regression analysis indicated that female (OR = 0.126, 95% CI 0.033–0.480, P = 0.006), live alone (OR = 0.195, 95% CI 0.042–0.944, P = 0.042), town (OR = 6.502, 95% CI 1.678–25.197, P = 0.007), city (OR=9.652, 95% CI 1.591–58.572, P=0.014), NRS≥ 4 (OR = 4.624, 95% CI 1.471–14.539, P = 0.009), social support (OR = 0.070, 95% CI 0.024–0.208, P < 0.001), anxiety (OR = 4.615, 95% CI 1.523–13.986, P = 0.007), depression (OR = 5.693, 95% CI 1.824–17.776, P = 0.003), fatigue (OR = 5.767, 95% CI 1.907–17.442, P = 0.002), KSS (OR = 0.183, 95% CI 0.045–0.743, P = 0.018), and other factors significantly increased the incidence of sedentary behaviour among patients with knee osteoarthritis. The study revealed that sedentary behaviour is substantial proportion among knee osteoarthritis patients, with extended sedentary periods. Consequently, healthcare providers should emphasize the importance of regular physical activity, employ evidence-based pain management strategies, enhance social support networks, and advise patients to promptly implement measures improving knee function while increasing their awareness of their own sedentary habits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis of the knee (KOA) is a chronic degenerative joint disease characterized by progressive loss of articular cartilage, subchondral bone sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. Clinically, it primarily manifests as joint pain, stiffness, and limited mobility1. As one of the primary causes of disability among China’s elderly population, KOA has a prevalence rate of 14.3%–22.3% in individuals aged 50 and older, with its disease burden showing a persistent upward trend2,3. Globally, over 250 million people suffer from KOA-related pain and functional limitations, imposing a heavy medical and socioeconomic burden on patients, families, and healthcare systems4,5.

Sedentary behaviour (SB) refers to sitting, reclining, or lying down with energy expenditure ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) during waking hours6. SB can be described by total daily sitting time or sitting patterns, including the distribution and interruption of sitting bouts, such as periods exceeding 30 min–1 h of continuous sitting7,8. Research indicates that SB is associated with a range of health risks, including metabolic disorders/muscle atrophy and cardiovascular diseases9. For KOA patients, SB may exacerbate joint stiffness and pain, reduce muscle strength around the joints and joint stability, and limit daily activity capacity, thereby leading to knee joint functional deterioration and reduced quality of life10. Furthermore, psychological factors like fear of exercise, anxiety, and depression may reinforce sedentary lifestyles in this population11,12. Recent studies from countries like Germany and Canada13,14 have examined SB patterns among KOA patients and their impact on pain and physical function, revealing that daily total SB duration ≥ 6 h is more substantial proportion among KOA patients than in healthy individuals. However, existing evidence varies across populations, and current Chinese SB studies15,16,17 predominantly focus on general elderly populations or chronic disease cohorts. Research on SB in KOA patients—a group with specific clinical manifestations—remains scarce. The prevalence of SB, associated factors, and modifiable determinants among KOA patients remain poorly understood.

Given the important role of SB measurement in understanding behavioural patterns, it is essential to note that SB can be assessed using both objective tools (e.g., accelerometers)18 and self-report instruments19. Although objective devices provide detailed information on sitting duration and patterns, their use is often limited in clinical settings due to cost, technical requirements, and patient compliance challenges. In contrast, self-reported measures such as questionnaires are widely used in epidemiological studies and have demonstrated acceptable validity for estimating total sitting time8,20. Considering feasibility, participant burden, and the clinical context of KOA patients awaiting surgery, this study employed self-reported sedentary behaviour measures, which are appropriate for capturing typical sitting time in daily life and are consistent with prior research in similar populations.

A deeper understanding of SB determinants in KOA patients is crucial for clinical management. Therefore, this study aims to patients with knee osteoarthritis who are awaiting surgery and identify key influencing factors. We hypothesize that pain, poor knee function, low levels of social support, and fatigue are significantly associated with SB among this type of people. The findings are expected to provide key evidence-based support for developing targeted intervention strategies to reduce SB duration and improve rehabilitation outcomes in KOA patients.

Materials and methods

Study population

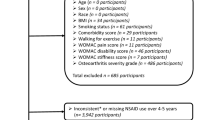

This study employed a cross-sectional design and was conducted from October 2024 to May 2025 in the Department of Orthopedics at the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Guizhou Province. All recruited patients were hospitalized but had not yet undergone surgical treatment. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age ≥ 18 years; (2) Meeting the diagnostic criteria for knee osteoarthritis outlined in the Chinese Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for Osteoarthritis (2024 Edition)21; (3) Being conscious and able to actively complete questionnaires; (4) Voluntarily participating and signing an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with arthritis or joint diseases in other locations; (2) Patients with significant damage to other major organs or tissues; (3) Patients requiring physical activity restrictions due to other conditions such as deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs or heart failure; (4) Patients currently participating in other similar studies.

Sample size calculation

According to multivariate statistical analysis requirements, the sample size should be 5 to 10 times the number of variables. This study involved 21 variables. Considering a 20% sample loss rate, the final sample size was determined to be 126 to 252 cases. A total of 325 questionnaires were distributed, with 311 valid responses ultimately included, yielding a response rate of 95.69%. Questionnaires were deemed invalid under the following circumstances: (1) patients with significant damage to other major organs or tissues; (2) patients requiring physical activity restrictions due to other conditions such as deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs or heart failure; (3) patients with mental disorders unable to independently complete self-reporting; (4) Patients participating in other similar studies. A total of 311 valid questionnaires were ultimately included. Questionnaires were deemed invalid under the following circumstances: (1) Incomplete questionnaires (e.g., missing or extra pages); (2) Partially answered sections with missing responses; (3) Multiple selections on single-choice questions.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (Ethics Review Number: KLLY-2024-019) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in the study.

Data collection

This study employed paper-based questionnaires for data collection. All investigators were thoroughly familiar with the administration methods and purposes of each questionnaire to ensure consistency and accuracy. Prior to questionnaire completion, investigators explained the study’s objectives and procedures to patients and obtained written informed consent. Patients completed the questionnaires in a quiet area of the ward under the supervision of a researcher. For questions or items that patients found difficult to understand, the researcher provided explanations without influencing the patient’s judgment and recorded the final answer based on the patient’s response.

Variables

The variables included in this study encompassed age, gender, BMI, marital status, living arrangements, place of residence, employment status, educational attainment, income level, healthcare payment status, duration of knee pain, comorbidities, pain intensity, social support, anxiety and depression, sleep quality, fatigue, fear of movement, and knee function. This framework was developed based on a review of prior literature and subsequent discussions8. However, existing evidence may still exhibit certain discrepancies. Therefore, we included these variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of SB in KOA patients.

Survey tools

Socio-demographic characteristics

The general information questionnaire was designed by the research team according to the study objectives. It included items on age, gender, educational attainment, employment status, place of residence, marital status, average monthly income, method of medical payment, BMI, comorbidities, and duration of knee pain. BMI was calculated based on patients’ height and weight, which were measured by medical staff using standardized professional tools upon admission.

Assessment of sedentary behaviour

Sedentary behaviour was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-S)22. Although the original IPAQ-S items referred to sitting time on “workdays,” our survey not only inquired about patients’ sitting time on workdays based on the IPAQ-S but also requested patients to recall their sitting time on weekends to better reflect their overall sedentary behaviour. After reviewing relevant literature, we established a cutoff of 6 h per day (h/d) for sedentary behaviour. Participants were classified as sedentary if their total daily sitting time was ≥ 6 h/d and non-sedentary if < 6 h/d. Following the IPAQ data processing and analysis guidelines, sedentary time was described using the median and interquartile ranges (IQRs).

Tampa scale of kinesiophobia (TSK-11)

The TSK-1123 consists of 1 dimension and 11 items. Each item is scored on a scale of 1 to 4, where one indicates strongly disagree, two indicates disagree, three indicates agree, and four indicates strongly agree. The total score ranges from 11 to 44. Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived kinesiophobia. A total score of ≥ 26 points is diagnostic of kinesiophobia24. The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.883, and the test-retest reliability is 0.798.

Knee Society Score (KSS)

The Knee Society Score (KSS)25 was developed by the American Knee Society to evaluate knee function across various knee conditions. The scale consists of two parts: joint score and function score. This study utilizes the function score component to assess patients’ knee function. The functional score (100 points) comprises walking (50 points) and stair climbing (50 points), with a penalty of -20 points for cane use. Based on scoring criteria, knee function is categorized into four grades: Excellent (80–100 points), Good (70–79 points), Fair (60–69 points), and Poor (< 60 points). Among inpatients scheduled for surgery, a small proportion had knee function rated as excellent (80–100 points) or good (70–79 points). Scores < 60 points were classified as poor function, while ≥ 60 points indicated fair function. The scale demonstrated a test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.93 and a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.8826.

Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS)

This item scale comprises three dimension27: subjective support, objective support, and utilization of support. The total score ranges from 12 to 66 points, with higher scores indicating greater social support. Scores ≤ 22 indicate low social support, 23–44 indicate moderate social support, and 45–66 indicate high social support. In this study, ≤ 22 points were defined as low social support, and > 22 points as higher social support. The scale demonstrated a test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.92 and a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.89.

Fatigue severity scale (FSS)

Krupp28 first developed the FSS. It is used to assess the severity, frequency, and impact of fatigue on daily life. The scale consists of nine items, and the average score of all items is the final total score. An FSS score of less than 4 indicates no fatigue, while an FSS score of 4 or higher indicates the presence of fatigue.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

Zigmond29 developed the HADS, and it is widely used to assess anxiety and depression in hospitalised patients. The scale consists of 14 items, divided into two subscales: anxiety (items 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13) and depression (items 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14). The total score for each dimension ranges from 0 to 21 points. A score below 8 indicates no anxiety or depression symptoms, 8–10 suggests possible symptoms and 11–21 indicates definite symptoms.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

The PSQI30 consists of 18 items and seven components, with a total score of 21 points. A PSQI score < 7 indicates good sleep quality, while a PSQI score ≥ 7 indicates poor sleep quality; the higher the score, the poorer the patient’s sleep quality. The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.84.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0 (IBM, Armonk). The Shapiro-Wilk test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to verify the normality and homogeneity of the data. Continuous variables following a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Continuous variables not following a normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). Participants were categorized into sedentary and non-sedentary groups based on total sitting time, with sedentary behaviour defined as ≥ 6 h per day. Differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between groups were assessed using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and independent samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables. Binary logistic regression was primarily employed to examine the relationship between a dichotomous dependent variable and one or more independent variables. This model was selected because our dependent variable was dichotomous. For multicollinearity diagnosis, we used variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Results showed all VIF values were less than 5, indicating no multicollinearity among the independent variables. Variables showing significant statistical differences in univariate analysis and those potentially representing confounding factors were included in the binary logistic regression model to identify key determinants influencing sedentary behaviour. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Participant characteristics

This study surveyed 311 patients with knee osteoarthritis. Results showed that daily sedentary time ranged from 2 to 10 h, with a median of 5 h (P25, P75: 4 h, 7 h). 45% of knee osteoarthritis patients reported ≥ 6 h of daily SB.

Univariate analysis of sedentary time in patients with knee osteoarthritis

Among the 311 enrolled patients, 62 (19.9%) were male and 249 (80.1%) were female; Ages ranged from 50 to 83 years (mean 64.96 ± 7.62), with 87 (28.0%) < 60 years, 131 (42.1%) aged 60–69 years, 84 (27.0%) aged 70–79 years, and 9 (2.9%) ≥ 80 years; Regarding BMI, 10 (3.2%) had a weight < 18.5 kg/m², 164 (52.77%) had 18.5–24.9 kg/m², 100 (32.2%) had 25.0–29.9 kg/m², and 37 (11.9%) had ≥ 30.0 kg/m²; Regarding marital status, 278 (89.4%) were married, while 33 (10.6%) were single, divorced, or widowed; Regarding lifestyle, 288 (92.6%) lived with others, while 23 (7.4%) lived alone. In terms of residential location, 54 (17.4%) resided in rural areas, 190 (61.1%) resided in towns, and 67 (21.5%) resided in cities. Regarding employment status, 149 (47.9%) were employed, while 162 (52.1%) were unemployed; In terms of education, 273 (87.8%) had received primary school education or below, and 38 (12.2%) had received junior high school education or above; For monthly per capita income, this classification was based on the 2024 disposable income of all residents in Guizhou Province (28,561 yuan/year) as released by the National Bureau of Statistics: 164 (52.7%) earned < 3,000 yuan/month, 133 (42.8%) earned between 3,000 and 5,000 per month, and 14 individuals (4.5%) earned over 5,000 per month. Regarding duration of knee pain, 43 (13.8%) experienced pain for less than 3 years, 91 (29.3%) experienced pain for 3 to 5 years, and 177 (56.9%) experienced pain for over 5 years. Patient characteristics with statistically significant differences are presented in Table 1.

Multivariate analysis of sedentary time in patients with knee osteoarthritis

In addition to variables showing statistically significant differences after univariate analysis (P < 0.05)—including age, BMI, place of residence, employment status, monthly per capita income, duration of knee pain, pain intensity, social support, anxiety/depression, sleep quality, fatigue, fear of movement, and knee function—the analysis also incorporated potential confounding factors previously identified in literature reviews as potentially influencing SB: gender, educational attainment, and housing type. A total of 17 variables were ultimately included in the binary logistic regression analysis (see Table 2 for variable coding). The results of the binary logistic regression analysis indicated that gender, living arrangement, place of residence, pain intensity, level of social support, presence of anxiety/depression, presence of fatigue, and knee function level were all risk factors for SB. Female (OR = 0.126, 95% CI 0.033–0.480, P = 0.006), live alone (OR = 0.195, 95% CI 0.042–0.944, P = 0.042), town (OR = 6.502, 95% CI 1.678–25.197, P = 0.007), city (OR = 9.652, 95% CI 1.591–58.572, P = 0.014), NRS ≥ 4 (OR = 4.624, 95% CI 1.471–14.539, P = 0.009), social support (OR = 0.070, 95% CI 0.024–0.208, P < 0.001), anxiety (OR = 4.615, 95% CI 1.523–13.986, P = 0.007), depression (OR = 5.693, 95% CI 1.824–17.776, P = 0.003), fatigue (OR = 5.767, 95% CI 1.907–17.442, P = 0.002), and KSS (OR = 0.183, 95% CI 0.045–0.743, P = 0.018) (see Table 3).

Discussion

SB is substantial proportion among patients with knee osteoarthritis

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and influencing factors of SB in patients with knee osteoarthritis. In this sample, 45% of participants reported at least 6 h of sitting time per day, suggesting that a substantial proportion of patients have a total sitting time of ≥ 6 h per day. Univariate analysis revealed that several sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were significantly associated with SB, including BMI, place of residence, employment status, monthly per capita income, pain, social support, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and knee function. After adjusting for potential confounders via binary logistic regression analysis, gender, living arrangement, pain, social support, anxiety/depression, fatigue, and knee joint function emerged as independent factors influencing SB. Notably, while gender did not show a significant effect on SB in univariate analysis (P = 0.243), it was identified as an independent factor in the multivariate model (P = 0.006). This suggests gender may exert an indirect influence on SB as a confounding or interaction variable, potentially mediated by other sociodemographic or psychological factors.

Although this finding was lower than results from previous studies2,9,20, this discrepancy may stem from the reliance on patient self-reports without objective measurement tools. Another possible reason is that patients lack systematic understanding and awareness of SB, potentially overlooking activities in daily life that qualify as sedentary (e.g., watching TV, playing board games), leading to underreported time spent sedentary31,32. SB increases intra-articular knee pressure and is closely associated with muscle atrophy and knee stiffness33, Without adequate joint loading and exercise, knee cartilage may progressively thin, increasing the risk of joint mobility limitations and functional decline34,35. Furthermore, studies indicate33,36 that SB not only correlates with metabolic risks like muscle weakness, elevated blood pressure, and reduced insulin sensitivity but may also indirectly impact mental health. It can trigger negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and fatigue, further diminishing patients’ willingness and ability to engage in rehabilitation exercises. In summary, SB serves as an independent and modifiable health indicator. Clinically, multi-level intervention strategies should be strengthened, encompassing routine inquiries and documentation of sedentary time by healthcare providers during consultations, alongside promoting individual behavior management under community rehabilitation guidance. Concurrently, policy initiatives can advance public education on “sedentary prevention,” fostering proactive rehabilitation awareness among patients during the early stages of disease.

Analysis of factors influencing SB in patients with knee osteoarthritis

Gender, living arrangements, and place of residence

Gender is a factor influencing SB. Our findings indicate that female patients had lower odds of reporting ≥ 6 h/day of sitting time than male patients. This may be attributed to female patients being more active in personality and social engagement, while older male patients tend to prefer static activities such as listening to the radio or watching television37. Furthermore, in traditional lifestyles, most women bear the responsibilities of caring for spouses and performing household chores38, which reduces their total sitting time. Furthermore, the study found that patients living alone had a lower odds of SB than those living with others (OR = 0.195, 95% CI: 0.042–0.944). Living alone necessitates independent management of daily affairs, increasing opportunities for activity39 and reducing the likelihood of SB compared to patients living with children or spouses. When accompanied or cared for, individuals may develop dependency, reducing their independent activity time and increasing sedentary tendencies40. The study indicates that patients residing in towns and cities have higher odds of engaging in SB than those in rural areas. This disparity may stem from lifestyle differences: rural residents often engage in agricultural labor and primarily walk for daily commutes, while urban dwellers rely more on electronic devices for entertainment and indoor social interactions41. Previous research42 indicates that environments influence individuals’ mental frameworks, health, and participation in physical activities, including engagement with and adherence to exercise. This finding suggests that addressing SB among urban and town residents should leverage accessible information and healthcare services⁴¹ to enhance health behavior promotion and guidance, thereby comprehensively reducing sedentary-related health risks across different residential areas.

Pain perception and knee joint function

Pain is one of the primary symptoms in patients with knee osteoarthritis and a significant factor influencing their SB. Our findings indicate that after adjusting for confounding factors, patients with pain scores (NRS ≥ 4) were approximately 4.624 times more likely to engage in SB compared to those with mild pain (NRS < 4). This result aligns with studies by Chang et al.43 and Powell et al.11, who noted that pain is a major barrier to reducing sedentary time, with over 40% of individuals exhibiting high sedentary frequency. The relationship between pain relief and SB is bidirectiona9l. Studies44 indicate that knee osteoarthritis patients may experience temporary pain relief shortly after sitting. This “temporary relief” reinforces SB, making patients more inclined to choose sitting to reduce discomfort. However, patients may be unaware that choosing to remain seated can lead to lower limb muscle atrophy, increased joint stiffness, accelerated functional decline, and chronic pain45. The long-term, repetitive interaction between pain and SB may create a vicious cycle of “pain-inactivity-pain,” thereby influencing disease progression and prognosis11. Knee joint dysfunction is also an important independent factor affecting SB. This study found that patients with knee function scores ≥ 60 had significantly lower odds of engaging in SB (OR = 0.183). Converted to probability terms, patients with scores ≥ 60 were approximately 35% less likely to sit ≥ 6 h per day compared to those with scores < 6012. Functional decline signifies activity limitations and insufficient muscle strength. To avoid pain and fall risks, patients reduce activity time, opting for SB46. These findings suggest that pain management and functional rehabilitation should be prioritized to reduce SB. This approach not only alleviates pain and improves knee function but also boosts patients’ confidence in activity, thereby breaking the vicious cycle of “pain-inactivity-more pain” and promoting the resumption of active movement.

Social support

This study found that individuals with knee osteoarthritis who reported lower levels of social support (≤ 22 points) were more likely to engage in SB. The Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) was employed in this research to measure social support, encompassing three dimensions: subjective support, objective support, and support utilization27. This scale reflects an individual’s comprehensive resource status in terms of psychological perception and actual support availability. Social support serves not only as a psychological coping mechanism but also as a crucial social driver for promoting healthy behavioral change. It influences SB through multiple pathways47: at the family level, companionship, care, and encouragement from family members provide practical assistance and emotional comfort during periods of pain or functional limitations; at the community level, interactions with peers and friends enhance patients’ sense of social engagement and motivation for activity, thereby reducing sedentary time48. This study further validates the protective effect of social support against SB: patients with social support scores > 22 points were less likely to exhibit total sitting time ≥ 6 h per day compared to those with scores ≤ 22 points. Findings suggest that SB interventions for knee osteoarthritis patients should integrate a social support perspective alongside individual-focused approaches.

Anxiety and depression

Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression are considered key psychological drivers of SB in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Our findings indicate that patients experiencing anxiety and depression are more likely to engage in SB, consistent with previous research48. From a behavioral mechanism perspective, depressive mood can diminish patients’ motivation to act and their sense of self-efficacy, leading them to prefer low-energy coping strategies like sitting still or resting to manage discomfort49. Anxiety, meanwhile, amplifies knee osteoarthritis patients’ fears of falling, pain recurrence, or exercise-related injury, cognitively exaggerating exercise risks and limiting their willingness to engage in physical activity50. Psychological factors may trigger SB through multiple pathways: First, at the behavioral motivation level, depressive mood reduces dopamine activity, diminishing patients’ drive to act and fostering avoidance or passive coping strategies51,52. Second, at the cognitive level, anxiety heightens anticipatory fears of exercise-related risks like falls or pain recurrence, fostering “catastrophizing” thought patterns that induce exercise phobia and behavioral avoidance. This inactivity may further diminish muscle strength and joint stability, exacerbating a vicious cycle of pain and anxiety53. Third, at the physiological level, neuroendocrine dysregulation triggered by emotional disorders may further suppress physical activity levels and recovery capacity. Prolonged neuroendocrine imbalance not only slows physical recovery but also intensifies fatigue and pain sensitivity, thereby further limiting activity tolerance54. Notably, SB itself may feed back to exacerbate emotional issues, forming a classic bidirectional vicious cycle between behavior and emotion55. Therefore, clinical management should integrate mental health assessments into SB intervention systems, promoting active participation in exercise rehabilitation by improving emotional states.

Fatigue

Chronic fatigue, a complex subjective experience, is present yet underestimated among patients with knee osteoarthritis, yet it significantly influences SB. This study found that patients experiencing fatigue were more likely to engage in SB, suggesting fatigue may increase the likelihood of SB by reducing physical energy reserves, activity tolerance, and motivation levels56. Previous research has indicated57 that fatigue serves as a key mediating variable between pain and functional capacity, potentially diminishing patients’ willingness to engage in daily activities by impairing physical recovery speed and muscle strength, thereby promoting sedentary choices58. Concurrently, SB impedes blood circulation and metabolic rates, exacerbating fatigue perception and creating a self-reinforcing negative feedback loop. Notably, fatigue is not a static condition but a malleable factor amenable to intervention59. Future research should therefore explore activity management strategies for KOA patients to achieve multiple objectives: pain control, fatigue reduction, and decreased SB.

Study limitations

This study is cross-sectional in nature and can only demonstrate statistical associations between SB and related variables. It cannot determine causal relationships or temporal sequences among these factors. For instance, whether anxiety and depression lead to SB, or whether SB exacerbates patients’ anxiety and depression, requires further validation. Additionally, data collection primarily relied on patient self-reports, which may be subject to memory bias and subjective judgment. Furthermore, the IPAQ-S questionnaire used in this study focused solely on “total daily sedentary time,” lacking differentiation for “single-session sedentary duration.” Future research could enhance data quality and reliability by incorporating wearable device monitoring or third-party assessments. This study classified daily sedentary time ≥ 6 h as SB based on prior literature. However, this threshold may introduce potential classification errors: First, no unified standard exists for defining SB thresholds. Second, some studies use ≥ 8 h daily as the cutoff for SB classification. The representativeness of the clinical sample is limited, as participants were exclusively hospitalized patients. The exclusion of asymptomatic KOA individuals in the community or early-stage patients may have resulted in a higher proportion of subjects with pain or impaired knee function, potentially amplifying the association between SB and symptoms. Furthermore, the study employed univariate analysis to prescreen variables before multivariate regression, potentially overlooking covariates with nonlinear relationships or interactions with the outcome.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the prevalence and influencing factors of SB among patients with knee osteoarthritis. Results indicate that SB is highly substantial proportion in this population and is influenced by multiple factors including place of residence, knee pain, knee function, fatigue, anxiety/depression, and level of social support. Findings suggest that SB is not merely a passive manifestation of knee function decline but may mediate between pain exacerbation and emotional distress, intensifying patients’ physical and psychological burdens. Clinically, SB is often overlooked; thus, this study emphasizes its importance as a key behavioral indicator in knee osteoarthritis rehabilitation management. For high-risk populations—such as those with functional limitations, low mood, or insufficient social support—integrated interventions combining behavioral modification, exercise guidance, and psychological support should be reinforced beyond standard treatments. Future research should further explore the time-dose effects of SB, validate the mechanisms by which behavioral changes influence disease progression and quality of life, and provide theoretical foundations and practical directions for developing precise, sustainable intervention strategies.

Data availability

The authors are able to provide the data that supports the findings of this study upon request. Please contact the corresponding author for further information.

References

Chinese Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation & West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Chinese guideline for the rehabilitation treatment of knee osteoarthritis (2023 edition). Chin. J. Evidence-Based Med. 24, 1–14 (2024).

Sliepen, M., Mauricio, E., Lipperts, M., Grimm, B. & Rosenbaum, D. Objective assessment of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in knee osteoarthritis patients - beyond daily steps and total sedentary time. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19, 64 (2018).

Skou, S. T., Pedersen, B. K., Abbott, J. H., Patterson, B. & Barton, C. Physical activity and exercise therapy benefit more than just symptoms and impairments in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 48, 439–447 (2018).

You, C. H. et al. Tuina promotes regeneration and remodeling of skeletal muscle vascular network in knee osteoarthritis. Chin. J. Integr. Traditional Western Med. 44, 627–631 (2024).

Clinical practice guidelines for exercise therapy in knee osteoarthritis Writing Group. Clinical practice guidelines for exercise therapy in knee osteoarthritis. Natl. Med. J. China. 100, 1123–1129 (2020).

Dzakpasu, F. Q. S. et al. Musculoskeletal pain and sedentary behaviour in occupational and non-occupational settings: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 18, 159 (2021).

Yin, M. et al. Short bouts of accumulated exercise: review and consensus statement on definition, efficacy, feasibility, practical applications, and future directions. J. Sport Health Sci. 101088 (2025).

You, Y. et al. The association between sedentary behavior, exercise, and sleep disturbance: A mediation analysis of inflammatory biomarkers. Front. Immunol. 13, 1080782 (2022).

Zhaoyang, R. & Martire, L. M. Daily sedentary behavior predicts pain and affect in knee arthritis. Ann. Behav. Med. 53, 642–651 (2019).

Kanavaki, A. M. et al. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and well-being: experiences of people with knee and hip osteoarthritis. Psychol. Health. 39, 1023–1041 (2024).

Powell, S. M., Larsen, C. A., Phillips, S. M. & Pellegrini, C. A. Exploring beliefs and preferences for reducing sedentary behavior among adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis or knee replacement. ACR Open. Rheumatol. 3, 55–62 (2021).

Master, H. et al. Joint association of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity and sedentary behavior with incident functional limitation: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J. Rheumatol. 48, 1458–1464 (2021).

Fiedler, J., Bergmann, M. R., Sell, S., Woll, A. & Stetter, B. J. Just-in-time adaptive interventions for behavior change in physiological health outcomes and the use case for knee osteoarthritis: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e54119 (2024).

Webber, S. C., Ripat, J. D., Pachu, N. S. & Strachan, S. M. Exploring physical activity and sedentary behaviour: perspectives of individuals with osteoarthritis and knee arthroplasty. Disabil. Rehabil. 42, 1971–1978 (2020).

Liang, Y., Tan, Y. H., Xing, H. M. & Wang, Y.The impact of behavioral change interventions on sedentary time and physical activity in patients with chronic diseases:a meta-analysis. Chin. J. Gerontol. 44, 2399–2404 (2024).

Li, X. R. & Zhang, C. Sedentary behavior after stroke and its influencing factors:a literature review. J. Nurs. Sci. 37, 106–109 (2022).

Song, X. Y., Li, X. X., Zhang, W. H., Chen, X. Y. & Lei, J. K. Status quo and influencing factors of sedentary behavior of frail elders with type 2 diabetes mellitus in nursing institutions. Military Nurs. 40, 14–17 (2023).

Bartholdy, C. et al. Reliability and construct validity of the SENS motion® activity measurement system as a tool to detect sedentary behaviour in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis. 2018, 6596278 (2018).

Rosenberg, D. E. et al. Reliability and validity of the sedentary behavior questionnaire (SBQ) for adults. J. Phys. Act. Health. 7, 697–705 (2010).

Ni, X. et al. Sedentary behaviour among elderly patients after total knee arthroplasty and its influencing factors. Sci. Rep. 14, 14278 (2024).

The Joint Surgery Branch of the Chinese Orthopaedic Association, The Subspecialty Group of Osteoarthritis, Chinese Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons, The National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric. Disorders (Xiangya Hospital) & editorial office of Chinese Journal of Orthopaedics. Chinese guideline for diagnosis and treatment of osteoarthritis (2024 edition). Chin. J. Orthop. 20, 323–338 (2024).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

Woby, S. R., Roach, N. K., Urmston, M. & Watson, P. J. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia. Pain 117, 137–144 (2005).

Xu, Y. Q. A research on influencing factors of kinesophobiain patients with knee arthroplasty, Master thesisUniversity of Electronic Science and Technology of China, (2023).

Insall, J. N., Dorr, L. D., Scott, R. D. & Scott, W. N. Rationale of the knee society clinical rating system. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 13–14 (1989).

Martimbianco, A. L. et al. Reliability of the "American Knee Society Score" (AKSS). Acta Ortop. Bras. 20, 34–38 (2012).

Xiao, S. Y. The theoretical basis and research applications of the social support rating scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 4, 98–100 (1994).

Krupp, L. B., LaRocca, N. G., Muir-Nash, J. & Steinberg, A. D. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch. Neurol. 46, 1121–1123 (1989).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 67, 361–370 (1983).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. III, Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Deguchi, N., Kojima, N., Osuka, Y. & Sasai, H. Factors associated with passive sedentary behavior among Community-Dwelling older women with and without knee osteoarthritis: the Otassha study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and osteoarthritis: a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Iran. J. Public. Health. 52, 2099–2108 (2023).

Seow, S. R. et al. Combined knee osteoarthritis and diabetes is associated with reduced muscle strength, physical inactivity, and poorer quality of life. J. Rehabil Med. 56, jrm39986 (2024).

Ma, X., Zhang, K., Ma, C., Zhang, Y. & Ma, J. Physical activity and the osteoarthritis of the knee: A Mendelian randomization study. Med. (Baltim). 103, e38650 (2024).

Cao, Z., Li, Q., Li, Y. & Wu, J. Causal association of leisure sedentary behavior with arthritis: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 59, 152171 (2023).

Sohn, M. W. et al. Sedentary behavior and blood pressure control among osteoarthritis initiative participants. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22, 1234–1240 (2014).

Zhu, C. J. et al. Research on the current situation and influencing factors of sedentary behavior in patients with colorectal cancer. Chin. Gen. Pract. 21, 1478–1481 (2023).

Hansen, B. H. et al. Monitoring population levels of physical activity and sedentary time in Norway across the lifespan. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 29, 105–112 (2019).

Li, X. R. et al. Analysis of the current situation and influencing factors of sedentary behavior in stroke patients. Chin. Gen. Pract. Nurs. 20, 1699–1702 (2022).

Fei, X. et al. The influence of the team follow-up model on the occurrence of complications and treatment compliance in bedridden stroke patients. Clin. Med. Res. Pract. 10, 48–51 (2025).

Zuo, Q., Peng, W. X., Zhu, L. L. & Jiang, X. L. Analysis of the urban-rural differences in the electronic health literacy level and influencing factors of community residents. Nurs. Res. 36, 587–593 (2022).

Shah, N., Kramer, J., Borrelli, B. & Kumar, D. Interrelations between factors related to physical activity in inactive adults with knee pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 44, 3890–3896 (2022).

Chang, A. H. et al. Association of long-term strenuous physical activity and extensive sitting with incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e204049 (2020).

Zhaoyang, R., Martire, L. M. & Darnall, B. D. Daily pain catastrophizing predicts less physical activity and more sedentary behavior in older adults with osteoarthritis. Pain 161, 2603–2610 (2020).

Luo, X. Q., Xia, L. X., Zeng, Y. K., Yan, Z. & Zheng, S. L. A qualitative study on the dilemma of changing sedentary behavior in patients with lower extremity arteriosclerosis obliterans. Chin. J. Nurs. 60, 2252–2257 (2025).

Parsowith, E. J. et al. The influence of chronic knee pain and age on conditioned pain modulation and motor unit control. Exp. Gerontol. 207, 112803 (2025).

Chen, Y. Y., Weng, L. C., Li, Y. T. & Huang, H. L. Mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between social support and self-management behaviors among patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 22, 635 (2022).

Kanavaki, A. M. et al. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open. 7, e017042 (2017).

Casanova, F. et al. Effects of physical activity and sedentary time on depression, anxiety and well-being: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 21, 501 (2023).

Hallgren, M. et al. Associations of interruptions to leisure-time sedentary behaviour with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Transl Psychiatry. 10, 128 (2020).

Rathbun, A. M. et al. Association between depressive symptoms and self-reported physical activity in persons with knee osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 52, 505–511 (2025).

Carratalá-Ros, C. et al. Preference for exercise vs. more sedentary reinforcers: validation of an animal model of tetrabenazine-induced anergia. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13, 289 (2019).

Kandola, A. & Stubbs, B. Exercise and anxiety. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1228, 345–352 (2020).

Nowacka-Chmielewska, M. et al. Running from stress: Neurobiological mechanisms of exercise-induced stress resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022).

Kloek, C. J. J. et al. Effectiveness of a blended physical therapist intervention in people with hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis, or both: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 98, 560–570 (2018).

Hodges, A. et al. Prevalence and determinants of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and fatigue five years after total knee replacement. Clin. Rehabil. 36, 1524–1538 (2022).

Foucher, K. C., Aydemir, B. & Huang, C. H. Walking energetics and fatigue are associated with physical activity in people with knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Biomech. 88, 105427 (2021).

Fawole, H. O. et al. Is the association between physical activity and fatigue mediated by physical function or depressive symptoms in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis? The multicenter osteoarthritis study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 50, 372–380 (2021).

Lynch, J., O’Donoghue, G. & Peiris, C. L. Classroom movement breaks and physically active learning are feasible, reduce sedentary behaviour and fatigue, and may increase focus in university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the study participants. This study would not have been possible without their contributions.

Funding

This study was funded by Zunyi Municipal Bureau of Industry and Science and Technology [Zunyi Science and Technology Cooperation HZ No. (2024) 292] and Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (Guizhou Composite Support [2023] General 263).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. and D.X.: conceived the study. D.X. and T.J.:designed the study. T.J., Y.C., L.Z. and Y.L.: conducted the questionnaire survey and collected the data. T.J. and Y.C.: performed the data analysis. D.X.: drafted the manuscript. L.S.,D.X. and T.J.reviewed the manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xing, D., Jia, T., Chen, Y. et al. Self-reported sedentary time and its influencing factors among patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 16, 3146 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32969-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32969-w