Abstract

To overcome inter-observer variability in conventional antral follicle count (AFC) assessment and AMH testing limitations, we developed an AI-powered framework using routine 2D ultrasound to standardize ovarian-reserve evaluation in assisted reproductive technology (ART). This multicenter retrospective study analyzed 395 women with infertility from two affiliated hospitals. The cohort was divided into training (n = 210), internal-test (n = 91), and external-test (n = 94) cohorts. We established three prediction models: radiomics model, 674 IBSI-compliant features; deep-learning model, ResNet50-based feature extraction; fusion model, hybrid approach combining both modalities. Model performance was validated against the manual AFC and serum AMH levels. Sequential classification categorized patients into low, moderate, or high ovarian-response risk groups. Strong correlation and consistency existed between routine 2D ultrasound image AFCs and three-dimensional dynamic-scan AFCs. The deep learning–radiomics fusion model displayed superior AFC prediction (R²=0.743 internal/0.583 external), surpassing the performance of single-modality models (radiomics: 0.586/0.572; deep learning: 0.737/0.541). For AMH prediction, the fusion model maintained generalizability (external R²=0.509 vs. 0.420 radiomics and 0.352 deep learning, p < 0.05). In ovarian-response stratification, the fusion model achieved an AUC of 0.881 (95%CI: 0.828–0.925), which was 8.0% higher than that of individual models, with 69.1% sensitivity and 84.6% specificity for identifying high-risk patients requiring stimulation-protocol modifications. The developed AI framework enables standardized ovarian-reserve evaluation using routine 2D ultrasound, effectively bridging imaging limitations by synergizing radiomics and deep learning. Meanwhile, the model achieves clinical applicability by enabling personalized ovarian-stimulation protocol optimization, demonstrating particular value in resource-limited clinical environments without requiring advanced imaging infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assessing ovarian reserve is crucial for determining female reproductive potential1, formulating controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) protocols2,3, predicting menopause risk4, and diagnosing premature ovarian insufficiency5. Common evaluation methods include biochemical tests and ultrasound exams, such as basal follicle-stimulating hormone, inhibin B, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), the clomiphene citrate challenge test, antral follicle count (AFC), ovarian volume, and ovarian blood supply6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. AMH and AFC are ideal for evaluating the ovarian reserve and predicting COS outcomes15,16,17. They both have a high accuracy in the prediction of ovarian response category18. For predicting high and low response to ovarian stimulation, use of either AFC or AMH is recommended19.

Limitations of AMH include the absence of an international standard for concentration evaluation, high costs, and time-consuming procedures, necessitating more stable and automated detection methods20,21. AFC is advantageous due to its non-invasive nature, ease of performance, and ability to separately evaluate each ovary15. Transvaginal ultrasound provides a comprehensive view of the structure and potential lesions of the uterus and bilateral adnexal areas22. However, manual follicle counting lacks standardization and is affected by inter-observer and inter-equipment variability16,21,23.

Three-dimensional ultrasound and intelligent analysis software can shorten transvaginal ultrasound scanning duration, allow offline AFC data analysis, and enhance inter-observer reliability24,25. However, these methods may inaccurately assess follicles averaging 2–10 mm in diameter26. Additionally, the high cost of equipment and software limits widespread use27,28. Poor image quality more adversely affects three-dimensional ultrasound than manual methods24.

We hypothesized that artificial intelligence could analyze static ultrasound images of bilateral ovaries to predict the ovarian reserve. We combined radiomics for high-throughput image feature quantification29 with deep convolutional neural networks for efficient feature learning30, integrating these methods into a unified system31,32.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

Appropriate ethical standards were followed throughout the entire study. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of the Women and Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (IRB-2024021) waived the need of obtaining informed consent. The study was carried out in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and the STROBE guidelines.

Data were retrospectively collected from 395 patients clinically diagnosed with infertility33, who underwent ovarian reserve assessment including AFC and AMH testing, at the Women and Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University between October 2016 and August 2023. As illustrated in Fig. 1, patients from Center 1 (Qixinggang branch) were divided into a training cohort (n = 210) and an internal-test cohort (n = 91) to develop and evaluate the model. To ensure model robustness and assess real-world generalizability across different clinical settings, patients from Center 2 (Ranjiaba branch), which operates independently with different equipment and sonographers, were used as the external-test cohort (n = 94).

Inclusion criteria: (1) premenopausal women aged ≥ 18; (2) individuals with a sexual history willing to undergo transvaginal ultrasound and AMH testing; and (3) regular menstrual cycles. Exclusion criteria: (1) ovarian disease, previous ovarian surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy; (2) prior ovarian stimulation; (3) functional cysts or follicles > 10 mm in diameter; and (4) poor-quality ultrasound images.

Additionally, considering the correlation between different ovarian responses after COS and AFC17,34, the participants were categorized based on their AFC values (≤ 5, 6–19, and ≥ 20), corresponding to poor, normal, and high ovarian responses, respectively1,15,35,36,37,38. AFC predictions was conducted for each of these categories.

AFC (dynamic scanning)—AFC3D

Transvaginal examinations were performed using ultrasound equipment, including the GE E8, GE S6, GE S8, GE E6 (GE Healthcare, USA), and the IE33, Q5 (Philips Company, USA). Antral follicles were counted manually after a comprehensive scan of both ovaries with the probe frequency set at 3–11 MHz, and the results were used as the AFC3D. All doctors who conducted the examinations had over 5 years of experience in gynecological ultrasound.

AFC (static image)—AFC2D

During the AFC3D assessment, fan-type scanning was performed in the long axis view of each ovary, and images were frozen at the section displaying the highest number of antral follicles. Subsequently, duplex images of both ovaries were stored in a Picture Archiving and Communication System (Fig. 2). A doctor with 5 years of experience in gynecological ultrasound examinations (Reader 1) counted the antral follicles in the duplex images, resulting in the AFC2D. Next, another doctor with 11 years of experience in gynecological ultrasound verified the counts (Reader 2). When discrepancies occurred, the counts from Reader 2 were considered the final decision.

AMH test

Venous blood samples (10 mL) were collected on the day of the transvaginal ultrasound. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then centrifuged at 3,000 r/min for 10 min using a centrifugation radius of 12 cm. The supernatant was subsequently transferred to another clean centrifuge tube and stored at -20 °C for analysis using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Image segmentation and pre-processing

Reader 2 segmented duplex ultrasound images of both ovaries using an open-source labeling tool (LabelMe; http://labelme.csail.mit.edu/Release3.0) to identify the regions of interest (ROIs). To enhance the visual contrast of these ROIs, a histogram equalization technique was applied to adjust the gray level distribution of the images. Subsequently, the pre-processed images were normalized and resized to 224 × 224 pixels for input into the deep-learning (DL) models. Specifically, the bicubic sampling method was employed for the images, while the nearest neighbor method was used for the masks, expanding the images into three channels to leverage the pretrained weights of ImageNet. The entire image-processing workflow was executed using Python (version 3.12.1) and OpenCV (version 4.9.0).

Development of machine learning-based radiomic model

Radiomic feature extraction selection

Radiomic features were extracted from each ovary’s ROI using Pyradiomics (version 3.0, https://pypi.org/project/pyradiomics/) per the Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative guidelines39. Original images underwent wavelet and Gaussian Laplacian filtering with kernel sizes of three and five, respectively, to extract first-order and textural features. Bin width parameters were set using the Freedman–Diaconis rule. The mean value of the bilateral ovarian features was standardized using z-score normalization to serve as the final radiomic feature. Details are presented in Online Resource 1 and 2.

Feature selection

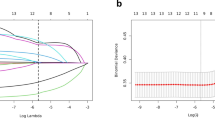

The stability of features was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Features with ICC ≥ 0.75 were considered highly stable and retained for further analysis. The selection of relevant radiomic features involved three steps: (1) Univariate linear regression was used for feature selection in the regression tasks (AFC3D and AMH), while the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for the three-class classification task to identify features with significant group differences; (2) redundant features with Pearson correlation coefficients > 0.90 were removed to eliminate collinearity; and (3) the most relevant radiomic features in the training cohort were identified using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method. The optimal parameter λ was determined through 10-fold cross-validation with 5,000 iterations. Coefficients for each feature were calculated based on the optimal λ, and features with non-zero coefficients were selected for model development.

Model development

Multivariate linear regression models were created to quantitatively predict AFC3D and AMH levels. For the three-class classification of AFC3D, five classifiers were developed: support vector machine, random forest, logistic regression, decision tree, and XGboost. Optimal parameters for each model were identified using five-fold cross-validation combined with a grid search strategy within the training cohort. The final model was chosen based on a comparative analysis of each classifier’s predictive performance in the internal-test cohort.

Development of DL and combined (rad-DL) models

Pre-processed bilateral ovarian ROI images were individually input into ResNet18. Deep features from the final convolutional layer were concatenated and processed through two fully connected layers with 256 hidden neurons each. Data augmentation techniques, including random horizontal and vertical flips, 0–30° random rotation, and gray-scale adjustments between 0.5 and 1.5, were applied to enhance model generalization. For quantitative prediction, the mean square error (MSE) loss function, Adam optimizer, and cosine-annealing strategies with an initial learning rate of 1e–3 were used. The cross-entropy loss function was utilized for classification tasks. The entire process was executed using PyTorch (https://pytorch.org/) and a GTX 4090 GPU (Nvidia GeForce).

Post ICC stability screening, radiomic features were combined with deep features and input into a two-layer fully connected network with 512 hidden neurons. We developed the Rad-DL model using the specified training strategy and parameters. For enhanced visualization, we applied the Grad-CAM40 technique to the last convolutional layer, offering visual explanations of the model’s decisions. The study design is depicted in Fig. 3.

The workflow of this study. Bilateral ovaries were contoured manually on the duplex static images with the largest number of antral follicles in the long axis, and the ROI enclosing the ovary was cropped as the predictive model input. The deep features and the radiomic features were separately extracted. The deep learning, radiomic, and Rad-DL models were developed for quantitative prediction of AFC3D and AMH levels, as well as sequential three-class classification prediction of AFC3D. Model evaluation was performed using ROC curves, calibration curves, and DCA. Additionally, Grad-CAM was employed to visualize the interpretability of deep learning. AFC, antral follicle count; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; DCA, decision curve analysis; DL, deep learning; Grad-CAM, Gradient-weighted class activation map; Rad, radiomics; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; ROI, region of interest.

Model evaluation

Evaluation indicators for quantitative predictions included R2, mean absolute error (MAE), MSE, median absolute error (MedAE), and explained variance (EV). The classification prediction models were evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic curve, as well as accuracy (ACC), confusion matrix, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score to evaluate model discrimination. Additionally, the calibration curve was utilized to assess model calibration, and decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed to evaluate the clinical utility of the prediction models by calculating the net benefit at different threshold probabilities.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range, based on the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. Spearman correlation analysis assessed correlations between continuous variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for single-sample tests. The Kruskal–Wallis test analyzed differences among three groups of sequential categorical variables, and the significance values were adjusted for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction. Bland–Altman plots verified the agreement between methods. Categorical variables are described as frequency and rate, and a two-sided test with P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Study population characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the quantitative predictions are presented in Table 1. The AFC3D was significantly greater than the AFC2D in the training cohort and in the internal-test and external-test cohorts (P < 0.05). The baseline characteristics of the sequential three-class classification prediction are presented in Table 2. The distribution of AFC3D ≤ 5, 6 ≤ AFC3D ≤ 19, and 20 ≤ AFC3D in the training, internal-test, and external-test cohorts were 62/27/34, 96/41/45, and 52/23/15, respectively. Additionally, as the number of AFC3D increased, the age of patients decreased progressively (P < 0.001), while AFC2D and AMH levels increased progressively (P < 0.001) across the three cohorts.

Correlation and consistency analysis

As shown in Table 3, AFC2D and AFC3D were highly correlated in both branches (P < 0.001). Additionally, AMH levels were strongly correlated with AFC3D (P < 0.001). The Bland–Altman plots (Fig. 4) indicated that only a few cases fell outside the 95% limit of agreement in the training, internal-test, and external-test cohorts. Specifically, this accounted for 4.3% (9 of the 210), 2.2% (2 of the 91), and 3.2% (3 of the 94), respectively. These findings demonstrate good agreement between the AFC2D and AFC3D.

Differences in AFC3D and AFC2D. Bland–Altman plots showing the mean (x-axis) and the difference (y-axis) in AFC between the methods. The full line marks the mean difference, and the dashed lines indicate the 95% limits of agreement (± 1.96 SD). A: training cohort; B: internal test cohort; C: external test cohort. AFC, antral follicle count; SD, standard deviation.

Radiomic feature extraction and selection

Overall, 674 quantitative radiomic features were extracted from the ultrasound images. After removing features with poor reproducibility (ICCs < 0.75) and stability, 437 radiomic features were selected for ANOVA and Pearson correlation analysis. Ultimately, the LASSO method identified 10 radiomic features for constructing a quantitative prediction model for AFC3D (Online Resource 3(a), (b), (c)), five radiomic features for the quantitative prediction model for AMH level (Online Resource 4(a), (b), (c)), and 10 radiomic features for the sequential three-class classification prediction of AFC3D (Online Resource 5(a), (b), (c)).

Establishment and evaluation of quantitative prediction models

Multiple linear regression was used as the kernel function for the radiomic model to quantitatively predict AFC3D and AMH levels. As presented in Table 4, in the training cohort, the R2 values for the radiomics, DL, and Rad-DL models were 0.641, 0.993, and 0.976, respectively. In the internal-test and external-test cohorts, the R2 values of the radiomic model were closely aligned, while those of the DL model indicated a significant decline in the external-test cohort. Additionally, the R2 values of the Rad-DL model in the internal-test and external-test cohorts were 0.743 and 0.583, respectively.

In the quantitative prediction of the AMH levels, as presented in Table 5, in the training cohort, the R2 values of the radiomic, DL, and Rad-DL models were 0.520, 0.950, and 0.962, respectively. In the internal-test and external-test cohorts, the R2 values of the radiomic model were 0.323 and 0.420, respectively, while those of the DL model were 0.591 and 0.352, respectively, showing a significant decline in the external-test cohort. The R2 values of the Rad-DL model in the internal-test and external-test cohorts were 0.550 and 0.509, respectively.

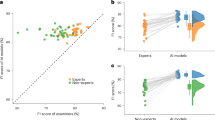

Higher R2 and EV, along with lower MAE, MSE, and MedAE values, demonstrate the superior regression performance of the models. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the radar charts based on each regression performance evaluation index indicate that the Rad-DL model exhibited the best overall performance in both prediction tasks.

A comprehensive evaluation of the quantitative prediction of AFC3D and AMH. A: the quantitative prediction of AFC3D; B: the quantitative prediction of AMH. MAE: mean absolute error; MSE: mean square error; MedAE: median absolute error; EV: explained variance; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; Rad, radiomics; DL, deep learning.

Establishment and evaluation of prediction model performance for the sequential three-class classification

Based on the results of the training cohort’s five-fold cross-validation and grid search, five machine learning models were compared in the internal-test cohort. As presented in Table 6, random forest demonstrated the best overall predictive performance according to metrics including AUC, ACC, F1, sensitivity, and specificity. Therefore, a random forest was selected as the final model for internal-test and external-test tasks.

The AUC values of the radiomic, DL, and Rad-DL models across the AFC3D categories in the training cohort, as well as the internal-test and external-test cohorts, are presented in Table 7; Fig. 6 (A–C). Detailed performance evaluation of the sequential three-class classification prediction for AFC3D is shown in Online Resource 6. According to the results of the DeLong test, the fusion of radiomic features into DL improved the predictive performance of the model in the internal-test and external-test cohorts (P = 0.15 and P = 0.08, respectively) (Table 7). The calibration curves of the three models showed good predictive performances in all cohorts, and the MAE values of the three models were 0.008, 0.035, and 0.033 for the external-test cohort, respectively (Fig. 6(D–F) and Online Resource 7(A–F)). Furthermore, the DCA results indicated that the fusion model achieved a greater net benefit across most ranges of threshold probabilities than the radiomic model, DL model, treat-all strategy, and treat-none strategy (Fig. 6(G–I)).

The performance evaluation of the sequential three-class classification prediction for AFC3D. A–C: Micro-average AUC in ROC curves of the sequential three-class classification in the training cohort and the internal and external test cohorts; D–F: calibration curves of the sequential three-class classification in the external test cohorts; G–I: DCA curves of the sequential three-class classification in the training cohort and the internal and external test cohorts. AFC, antral follicle count; AUC, the area under the curve; DCA, decision curve analysis; DL, deep learning; Rad, radiomics; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve.

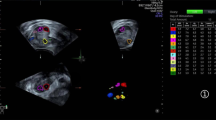

Interpretability of the DL model

We utilized Grad-CAM to visualize the interpretability of the DL model. Heatmaps and their superpositions on the ultrasound images were acquired from the external-test cohort (Fig. 7). We found that the anechoic regions of the antral follicles had the most active algorithm activation, demonstrating that these regions had the most obvious predictive value for the DL model.

Two-dimensional ultrasonic gray-scale map of ovaries and corresponding activation heat map. The color change from red to blue corresponds to the degree of algorithm activation within the region. From the examples presented, it can be observed that the anechoic regions where the antral follicles are located have the most obvious red coding, proving that these regions have the most active algorithm activation and the highest predictive value for deep learning models.

Discussion

Radiomics and DL are extensively used in medical image recognition and analysis. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided manual counting of antral follicles is standard for assessing the ovarian reserve41. Advances in ultrasound and computerized analysis now enable more accurate evaluations by analyzing comprehensive bilateral ovarian images rather than just counting antral follicles. Studies on automating the measurement of antral follicle diameter, volume, and number using three-dimensional ultrasonographic DL28,42 demonstrated reduced time and improved inter-observer reliability24,25,43. Clinically, the focus is on assessing the ovarian reserve rather than exact follicle counts, making the use of expensive ultrasound equipment with three-dimensional automated volume imaging and counting22 impractical.

We selected duplex static images showing the most antral follicles along the long axes of both ovaries. Despite static images displaying significantly fewer antral follicles than dynamic scans, there was a strong correlation and consistency between the two imaging methods. This indicates that ovarian storage function information from static images is closely related to that from dynamic scanning, suggesting a potential for technical replacement. This established the basis for subsequent intelligent image analysis. The radiomics model demonstrated greater robustness than the DL model in quantitatively predicting AFC3D in both internal and external cohorts. Notably, the radiomics model outperformed the DL model on the external-test cohort, a difference partly attributable to the lower resolution of external ultrasound images, which can adversely affect DL performance44,45,46,47. This effect is especially pronounced for more complex tasks, such as AMH prediction, where instability in learned deep features can reduce generalization. To mitigate this and enhance robustness, we developed a hybrid Rad-DL approach that integrates handcrafted radiomics features with automatically learned deep features, enabling the model to leverage both stable, interpretable features and rich data-driven representations. As shown in our results, the Rad-DL model achieved the best overall performance across three tasks: it performed comparably to radiomics in the simpler AFC regression task but substantially outperformed both radiomics and DL in the more challenging AMH regression, particularly under lower image-quality conditions. In the quantitative AMH study, all three models underperformed relative to AFC3D across all cohorts. This disparity is largely attributable to the strong positive correlation between AMH and AFC3D; although both are established ovarian-reserve biomarkers, they do not always concur. Zhang et al. reported that approximately 20% of infertile patients exhibited discordant AFC and AMH levels in clinical practice48. Moreover, in the AFC regression task, the three models demonstrated similar performance on the external-test cohort, likely because AFC is a morphological trait that is directly visible and measurable on ultrasound, making it a relatively straightforward learning problem for image-based models. In contrast, AMH lacks a direct visual correlate on ultrasound and must be inferred indirectly via morphological proxies such as AFC, which increases task complexity and reduces learnability from image data alone. Additionally, regarding the models themselves, we implemented several strategies during development to mitigate overfitting, including early stopping, dropout, and cross-validation. Nevertheless, the complex nature of high-dimensional data and the relatively limited sample size in the deep-learning tasks contribute to this challenge. Moreover, quantitative regression problems—because of their sensitivity to noise and the need to predict continuous values—are more prone to overfitting than classification tasks. By contrast, for the sequential three-class classification task, overfitting was much more controlled: the performance of the DL and Rad-DL models remained stable across both test cohorts. These results suggest that the overfitting-mitigation strategies were more effective for classification, and the observed generalization gap is within an acceptable range.

Accurate assessment of the ovarian reserve through AFC is crucial for identifying patients at high risk of poor or excessive ovarian response, enabling the selection of appropriate COS protocols49,50,51,52. However, counting antral follicles accurately is challenging due to factors like operator experience22, examination equipment53, and patient conditions (e.g., obesity, intestinal gas interference). Consequently, a sequential three-class classification prediction was conducted following the quantitative prediction of the AFC3D. The three models showed strong discrimination in identifying high risk patients with poor or excessive ovarian response but were less effective for those with a normal ovarian reserve. The primary clinical challenge is to prevent poor and excessive ovarian responses during COS. The proposed sequential three-class classification model offers a practical and efficient solution, particularly when AFC is challenging because of factors such as high ovaries, bowel gas interference, obesity, and the presence of pathological lesions that may obscure follicle visualization. By streamlining the assessment workflow, the model significantly reduces both the sonographer’s workload and ultrasound acquisition time. The static images for analysis can be obtained from the most common and widely used ultrasound devices. The analysis does not require the examined equipment to have additional computational capabilities, as it can be performed centrally in the cloud. By streamlining the assessment workflow, the model significantly reduces both the sonographer’s workload and the ultrasound acquisition time. Since there is no need for rigid dynamic scanning to count all antral follicles for accurate screening of patients with different ovarian responses, we believe this approach is particularly well-suited for clinical settings where high-end ultrasound equipment is lacking, operator experience is limited, or procedural standardization is weak.

The ultimate goal of our research is to elucidate the correlation between ultrasound imaging features and fertility treatment outcomes, including precision-driven gonadotropin dosing strategies, the yield of mature (M2) oocytes, blastocyst formation rates, and, ultimately, clinical pregnancy rates. However, the focus of the current study was to validate the effectiveness of our new method compared with that of conventional AFC before accounting for confounding factors such as stimulation protocols, with the aim of demonstrating that this new method can be as effective as conventional AFC in predicting outcomes. Future studies should further explore the model’s applicability for long-term outcome prediction and its potential integration into personalized assisted reproductive technology protocols. This study had some limitations. First, the image resolution of the external-test cohort was significantly compromised due to disparities in image acquisition cards between the two branches, which affected the model’s performance in quantitative prediction. Developing models that can be effectively applied to ultrasound images of varying quality is essential. Future research will use DL-based super-resolution reconstruction technology54,55 to enhance image resolution and establish an improved cohort for external model testing. Second, operator subjectivity influenced the selection of static images with the most antral follicles along the long axis of both ovaries, though overall image classification was less subjective than manual methods. Third, the applicability of the model was somewhat limited due to the selection of only cases with regular menstrual cycles, therefore not suitable for patients with polycystic ovary syndrome, and the exclusion of cases with ovarian cysts or follicles larger than 10 mm in diameter. Lastly, the data comprised a moderate sample size from two branches of the same hospital. Expanding the sample size and increasing the number of participating centers is critical for enhancing prediction accuracy.

Conclusion

This study utilized radiomics and DL on static ultrasound images of the ovaries to predict AFC and AMH levels. The models can quantitatively estimate antral follicle counts and accurately identify patients with infertility who have abnormal ovarian reserves. This research lays a solid foundation for advancing beyond the conventional AFC method and exploring intelligent, non-invasive approaches for assessing the ovarian reserve.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ferraretti, A. P. et al. ESHRE consensus on the definition of poor response to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1616–1624. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der092 (2011).

Tsakos, E., Tolikas, A., Daniilidis, A. & Asimakopoulos, B. Predictive value of anti-Mullerian hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and antral follicle count on the outcome of ovarian stimulation in women following GnRH-antagonist protocol for IVF/ET. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 290, 1249–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3332-3 (2014).

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine & Suppl Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 90, S188–S193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.034 (2008).

Depmann, M. et al. Can we predict age at natural menopause using ovarian reserve tests or mother’s age at menopause? A systematic literature review. Menopause 23, 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000509 (2016).

Ke, H. et al. Landscape of pathogenic mutations in premature ovarian insufficiency. Nat. Med. 29, 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02194-3 (2023).

Navot, D., Rosenwaks, Z. & Margalioth, E. J. Prognostic assessment of female fecundity. Lancet 2, 645–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92439-1 (1987).

Fanchin, R. et al. Exogenous follicle stimulating hormone ovarian reserve test (EFORT): a simple and reliable screening test for detecting poor responders in in-vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod. 9, 1607–1611. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138760 (1994).

Broekmans, F. J., Kwee, J., Hendriks, D. J., Mol, B. W. & Lambalk, C. B. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum. Reprod. Update. 12, 685–718. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dml034 (2006).

Hall, J. E., Welt, C. K. & Cramer, D. W. Inhibin A and inhibin B reflect ovarian function in assisted reproduction but are less useful at predicting outcome. Hum. Reprod. 14, 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/14.2.409 (1999).

La Marca, A. et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART). Hum. Reprod. Update. 16, 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmp036 (2010).

Steiner, A. Z. et al. Association between biomarkers of ovarian reserve and infertility among older women of reproductive age. JAMA 318, 1367–1376. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.14588 (2017).

Leonhardt, H., Gull, B., Stener-Victorin, E. & Hellström, M. Ovarian volume and antral follicle count assessed by MRI and transvaginal ultrasonography: a methodological study. Acta Radiol. 55, 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113495835 (2014).

Kelsey, T. W. et al. Ovarian volume throughout life: a validated normative model. PLOS One. 8, e71465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071465 (2013).

Deb, S., Kannamannadiar, J., Campbell, B. K., Clewes, J. S. & Raine-Fenning, N. J. The interovarian variation in three-dimensional ultrasound markers of ovarian reserve in women undergoing baseline investigation for subfertility. Fertil. Steril. 95, 667–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.031 (2011).

Lima, M. L. et al. Assessment of ovarian reserve by antral follicle count in ovaries with endometrioma. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 46, 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14763 (2015).

Fleming, R., Seifer, D. B., Frattarelli, J. L. & Ruman, J. Assessing ovarian response: antral follicle count versus anti-Müllerian hormone. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 31, 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.06.015 (2015).

Farquhar, C. et al. Management of ovarian stimulation for IVF: narrative review of evidence provided for world health organization guidance. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 35, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.03.024 (2017).

Liu, Y., Pan, Z., Wu, Y., Song, J. & Chen, J. Comparison of anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicle count in the prediction of ovarian response: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ovarian Res. 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-023-01202-5 (2023).

The ESHRE Guideline Group on Ovarian Stimulation et al. Ovarian Stimulation for IVF/ICSI†. European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology updated 2025. (2020).

Dewailly, D. et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum. Reprod. Update. 20, 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt062 (2014).

Iliodromiti, S., Anderson, R. A. & Nelson, S. M. Technical and performance characteristics of anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicle count as biomarkers of ovarian response. Hum. Reprod. Update. 21, 698–710. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmu062 (2015).

Coelho Neto, M. A. et al. Counting ovarian antral follicles by ultrasound: a practical guide. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 51, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.18945 (2018).

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 103, e9–e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.093 (2015).

Jayaprakasan, K., Walker, K. F., Clewes, J. S., Johnson, I. R. & Raine-Fenning, N. J. The interobserver reliability of off-line antral follicle counts made from stored three-dimensional ultrasound data: a comparative study of different measurement techniques. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 29, 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.3913 (2007).

Jayaprakasan, K. et al. Does 3D ultrasound offer any advantage in the pretreatment assessment of ovarian reserve and prediction of outcome after assisted reproduction treatment? Hum. Reprod. 22, 1932–1941. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem104 (2007).

Martins, W. P. & Jokubkiene, L. Assessment of the functional ovarian reserve. In: (eds Guerriero, S., Martins, W. P. & Alcazar, J. L.) Managing Ultrasonography in Human Reproduction: A Practical Handbook. Springer International Publishing; :3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41037-1_1 (2017).

Rodriguez, A. et al. Learning curves in 3-dimensional sonographic follicle monitoring during controlled ovarian stimulation. J. Ultrasound Med. 33, 649–655. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.33.4.649 (2014).

Rodríguez-Fuentes, A. et al. Volume-based follicular output rate improves prediction of the number of mature oocytes: a prospective comparative study. Fertil. Steril. 118, 885–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.07.017 (2022).

Gillies, R. J., Kinahan, P. E. & Hricak, H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology 278, 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015151169 (2016).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data. 8, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00444-8 (2021).

Song, D. et al. Using deep learning to predict microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma based on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI combined with clinical parameters. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 147, 3757–3767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03617-3 (2021).

Huang, B. et al. Deep semantic segmentation feature-based radiomics for the classification tasks in medical image analysis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 25, 2655–2664. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2020.3043236 (2021).

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Electronic address: asrm@asrm.org, practice committee of the American society for reproductive Medicine. Fertility evaluation of infertile women: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 116, 1255–1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.038 (2021).

Ng, E. H., Tang, O. S. & Ho, P. C. The significance of the number of antral follicles prior to stimulation in predicting ovarian responses in an IVF programme. Hum. Reprod. 15, 1937–1942. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/15.9.1937 (2000).

Hendriks, D. J., Mol, B-W-J., Bancsi, L. F. J. M. M., Te Velde, E. R. & Broekmans, F. J. M. Antral follicle count in the prediction of poor ovarian response and pregnancy after in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis and comparison with basal follicle-stimulating hormone level. Fertil. Steril. 83, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.011 (2005).

Polyzos, N. P., Tournaye, H., Guzman, L., Camus, M. & Nelson, S. M. Predictors of ovarian response in women treated with corifollitropin Alfa for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil. Steril. 100, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.029 (2013).

Jayaprakasan, K. et al. Can quantitative three-dimensional power doppler angiography be used to predict ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 33, 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.6373 (2009).

Kollmann, M., Martins, W. P. & Raine-Fenning, N. Examining the ovaries by ultrasound for diagnosing hyperandrogenic anovulation: updating the threshold for newer machines. Fertil. Steril. 101, e25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.012 (2014).

Zwanenburg, A. et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology 295, 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020191145 (2020).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.74 (2017).

Chinè, A. et al. Low ovarian reserve and risk of miscarriage in pregnancies derived from assisted reproductive technology. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2023, hoad026. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoad026 (2023).

Rodrigues, A. R. O. et al. Comparing two- and three-dimensional antral follicle count in patients with endometriosis. J. Med. Ultrasound. 30, 282–286. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmu.jmu_204_21 (2022).

Scheffer, G. J. et al. Quantitative transvaginal two- and three-dimensional sonography of the ovaries: reproducibility of antral follicle counts. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 20, 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00787.x (2002).

Javed, H., El-Sappagh, S. & Abuhmed, T. Robustness in deep learning models for medical diagnostics: security and adversarial challenges towards robust AI applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 58 (1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-024-11005-9 (2024).

Sabottke, C. F. & Spieler, B. M. The effect of image resolution on deep learning in radiography. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2, e190015. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.2019190015 (2020).

Tang, S. et al. The effect of image resolution on convolutional neural networks in breast ultrasound. Heliyon 9, e19253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19253 (2023).

Thambawita, V. et al. Impact of image resolution on deep learning performance in endoscopy image classification: an experimental study using a large dataset of endoscopic images. Diagnostics (Basel). 11, 2183. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11122183 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Discordance between antral follicle counts and anti-Müllerian hormone levels in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 17, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-019-0497-4 (2019).

Mathur, P., Kakwani, K., Diplav, K. S., Kudavelly, S. & Ga, R. Deep learning based quantification of ovary and follicles using 3D transvaginal ultrasound in assisted reproduction. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2020, 2109–2112. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9176703 (2020).

Broer, S. L. et al. Added value of ovarian reserve testing on patient characteristics in the prediction of ovarian response and ongoing pregnancy: an individual patient data approach. Hum. Reprod. Update. 19, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dms041 (2013).

Racca, A., Drakopoulos, P., Neves, A. R. & Polyzos, N. P. Current therapeutic options for controlled ovarian stimulation in assisted reproductive technology. Drugs 80, 973–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01324-w (2020).

Chen, M-X. et al. An individualized recommendation for controlled ovary stimulation protocol in women who received the GnRH agonist long-acting protocol or the GnRH antagonist protocol: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 899000. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.899000 (2022).

Jayaprakasan, K., Campbell, B., Hopkisson, J., Johnson, I. & Raine-Fenning, N. A prospective, comparative analysis of anti-Müllerian hormone, inhibin-B, and three-dimensional ultrasound determinants of ovarian reserve in the prediction of poor response to controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil. Steril. 93, 855–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.042 (2010).

Hou, M., Zhou, L. & Sun, J. Deep-learning-based 3D super-resolution MRI radiomics model: superior predictive performance in preoperative T-staging of rectal cancer. Eur. Radiol. 33, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-022-08952-8 (2023).

Cammarasana, S., Nicolardi, P. & Patanè, G. Super-resolution of 2D ultrasound images and videos. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 61, 2511–2526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-023-02818-x (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the participants for the support in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization : Jinwei Zhang, Shangqing Liu, Dong Ni; Data curation : JinweiZhang, Shangqing Liu, Suzhen Ran; Formal analysis : Jinwei Zhang, Shangqing Liu; Funding acquisition: Jinwei Zhang; Investigation : Shuang Liu, Yue Rong, Chunyan Zhong; Methodology : Jinwei Zhang, Shangqing Liu; Project administration : Suzhen Ran; Resources : Jinwei Zhang, Suzhen Ran; Software: Shangqing Liu, Dong Ni; Supervision : Suzhen Ran, Dong Ni; Validation : Shuang Liu, Yue Rong; Visualization : Shangqing Liu; Writing-original draft : Jinwei Zhang, Shangqing Liu; Writing-review &editing : all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Appropriate ethical standards were followed throughout the entire study. The Ethics Committee of the Women and Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University approved this retrospective study (IRB-2024021). The requirement for informed consent was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Liu, S., Liu, S. et al. Ultrasound radiomics and deep learning for predicting antral follicle count and anti-Müllerian hormone. Sci Rep 16, 3115 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33010-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33010-w