Abstract

The Perseverance rover has collected rock samples from the floor of Jezero crater, Mars, set to be returned to Earth through the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. These surface rocks are continuously bombarded by cosmic rays, resulting in the formation of cosmogenic nuclides. To accurately date these rocks and understand past geological events, precise estimates of nuclide production rates are essential. Here, we simulate neutron-induced cosmogenic nuclide production in the igneous rocks of Jezero crater using neutron flux data from the radiation assessment detector (RAD) and rock compositions from the planetary instrument for X-ray lithochemistry (PIXL). Our calculations focus on stable and long-lived isotopes up to Z = 27 (Co) over an exposure period of 100,000 years (0.1 Ma). The highest yields are observed for \({}^{1}H\) and \({}^{4}He\), followed by \({}^{12}C\), \({}^{13}C\), \({}^{15}N\), \({}^{23}Na\), \({}^{27}Al\) and \({}^{36}Cl\). We show that the predicted cumulative production over 0.1 Ma of long-lived radionuclides such as \(^{10}Be\) (T1/2 = 1.39 Ma), \(^{26}Al\) (0.72 Ma), \(^{36}Cl\) (0.301 Ma), and \(^{41}Ca\) (0.104 Ma) reaches ~ 108–109 nuclei per gram, a concentration well within the detection limits of current accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) techniques. We project the impact of extended cosmic radiation exposure (1.4 billion years) on isotopic ratios, showing significant shifts in δ13C and δ15N values, whose correct interpretation is critical for astrobiology. These calculations can help define the instrumentation requirements for the future analysis of the Martian samples on Earth, ensuring accurate interpretation and helping to distinguish radiation effects from other planetary and biological cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Perseverance rover is acquiring a collection of drilled rock samples of about 5 cm depth, at the surface of Jezero Crater, its delta and crater rim, on Mars. This collection will be brought to Earth as part of the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission1,2,3. The present-day surface and subsurface of Mars have been bombarded for tens of millions to billions of years by the energetic particles of galactic cosmic radiation (GCR), solar cosmic rays (SCR) and the secondary particles produced by their interaction with atomic nuclei in the atmosphere and surface. This incident flux produces cosmogenic nuclides on exposed rocks, regolith and bedrock altering also the original element isotopic composition of rocks formed on the surface of Mars4,5.

Depending on the surface exposure age of the rocks, this process may have happened for tens of millions to billions of years. The crater floor of the Jezero crater has undergone a complex accumulation and exhumation history. First, the deltaic/lacustrine activity would have produced sediments burying the dark floor unit, and then, later, due to their erosion, the dark floor unit would have been gradually exposed6. As the crater floor is the only major crater-retaining surface within Jezero, its crater density has been investigated by several independent studies and the crater-counting derived ages range from 3.5 to 1.4 Gy (billion years), that is, from Hesperian to Amazonian7,8,9,10,11,12. Schon et al.8 suggest that the most recent resurfacing event of the crater floor unit can be dated, based on the size-frequency distribution of superposed craters, to the Early Amazonian with a best fit of 1.4 Gy. In comparison, the high-resolution crater size‐frequency distributions analysis done by Rubanenko et al.12 in the centre of Jezero attests that this part of the floor unit has been exposed since about 2.5 Gy ago. The chronology of Martian surfaces is currently estimated using the crater counting method, which relies on the number and distribution of impact craters to infer relative ages. However, this method requires absolute age calibration to ensure accuracy. The precise formation and exposure age can only be assessed by analyzing on Earth, the isotopic ratios of different nuclides.

The Curiosity rover, at Gale crater on Mars, has already demonstrated the potential of isotopic fractionation analysis of Martian samples to interpret the history of the planet. In-situ measurements indicate that elevated δD values suggest recent atmospheric exchange, while carbon isotope data in fine-grained materials point to multiple carbon sources13,14. Many studies have focused on the effects of ionizing radiation on the production of cosmogenic noble gases15,16,17, while other research has explored its impact on organic preservation, biological survival, habitability, and the potential of \(\delta^{13}C\) and \(\delta^{15}N\) as biomarkers5.

The analysis of noble gas isotopes, such as He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe, is commonly used in planetary science for dating rocks. Their atmospheric abundances on terrestrial planets are mainly controlled by the outgassing of solid materials throughout their geological history. Notably, the radiogenic production of \({}^{40}Ar\) by decay of \({}^{40}K\), has been studied with Curiosity rover, at Gale Crater, to date rocks18,19,20. Conversely, cosmogenic production of \({}^{36}Ar\), \({}^{21}Ne\), and \({}^{3}He\) was used for the in-situ dating of the Cumberland mudstone18. The K–Ar age of the mudstone showed a 4.21 ± 0.35 Gy old for the mixture of detrital and authigenic components and confirms the expected antiquity of rocks comprising the crater rim. However, the cosmic-ray–produced \({}^{3}He\), \({}^{21}Ne\), and \({}^{36}Ar\) yielded surface exposure ages of only 78 ± 30 million years, demonstrating the possibility for surface rocks to have been formed long before, while being exposed only recently by erosional process. This is an example of where the recent formation of nuclides can alter the rock isotopic composition.

Cosmogenic nuclides are typically used for the study of the formation and evolution of terrestrial and extraterrestrial samples21. To analyse cosmogenic nuclides in a given sample two conditions must be met: (1) their concentration must be sufficiently high to exceed the detection limits of current analytical techniques and the initial background level of the nuclide in the sample, and (2) the nuclides must be either stable or possess a half-life comparable to, or longer than, the timescale under study. The samples from Jezero crater, where Perseverance is sampling, are rich in SiO2 and Fe oxides, as all rocks on Mars. Energetic cosmic ray particles and their secondary cascade particles (e.g., neutrons) impacting on iron (Fe), silica (Si) and oxygen, can produce different nuclides through spallation reactions21. The future analysis on Earth of the rocks, regolith, and atmospheric samples acquired by Perseverance rover for the Mars Sample Return collection presents a unique opportunity to use cosmogenic nuclides as tools to delineate the evolutionary history of the planet. For instance, this analysis can help determining the chemical and thermal evolution of the planet, using mineralogy, geochemistry, and isotopic analysis of xenoliths in volcanic and plutonic rocks. Stable isotopes on authigenic minerals can help determine conditions (e.g., temperatures, depth) of formation, whereas precise radiometric isotope dating of cementing agents or K-rich authigenic components can help interpret the cementation processes.

In particular, the \({}^{13}C\)/\({}^{12}C\) and \({}^{15}N\)/\({}^{14}N\) isotopic ratios are key indicators of the Martian atmospheric evolution and the surface-atmosphere interactions. These elements, which are essential for organic molecules and life, also have astrobiological significance. Isotopic variations provide insights into atmospheric escape processes and potential organic reservoirs. The carbon isotopic \(\delta {}^{13}C\)=[((\({}^{13}C\) )⁄\({}^{12}C\))sample/(((\({}^{13}C\))⁄\({}^{12}C\))stand.)-1] × 1000 of a sample, is a measure of the ratio of the two stable isotopes of carbon \({}^{13}C\) and \({}^{12}C\) reported in parts per mil. Where ((\({}^{13}C\))⁄\({}^{12}C\))stand. = 0.0112372, based on the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard value22. For instance, the Curiosity rover has analysed in situ the isotopic ratio of carbon13,14,23,24,25,26,27. Stern et al.26 analysed the isotopic ratio of the high energy combustion released CO2 in a sample with 273 ppm of organic carbon, on the Yellowknife Bay mudstone at Gale crater and found \(\delta^{13}C\) = −32.9 to −10.1‰. House et al. 2022 analysed the CH4 released during pyrolysis of 24 powder samples at Gale crater, finding a high degree of variation (\(\delta {}^{13}C\)=−137 ± 8‰ to + 22 ± 10‰). Included in these data are 10 measured \(\delta {}^{13}C\) values less than −70‰ found for six different sampling locations, all potentially associated with a possible paleosurface.

The future high-precision laboratory investigation of the Mars Sample Return samples on Earth will require the analysis of different isotopes to establish a geochronology and interpret the role of planetary, atmospheric and biological cycles on the isotopic fractionation. In particular, the isotopic analysis of the samples from the Jezero region is expected to provide constraints on the timing of events, the emplacement of the crater floor as well as on the onset of lake activity and the recent erosional, burial and exhumation history of these rocks. However, these isotopic ratios may also have been partly influenced by the more recent impact of cosmic radiation on the exposed rocks and may additionally depend on the specific composition of the sampled rock. Pavlov et al.5 analysed with the Monte-Carlo simulation code GEANT4 the potential impact of GCR and SCR radiation on the isotopic ratios of carbon C on a standard Mars rock composition demonstrating the nucleogenesis would alter \(\delta {}^{13}C\) and \(\delta {}^{14}N\) overtime.

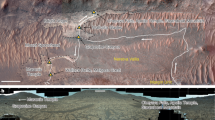

In this study, we examine cosmogenic nuclide production in the four igneous rocks sampled by Perseverance from the crater floor to illustrate the expected production rates. These rocks, located within approximately 600 m of each other, may have distinct origins and cosmic exposure history. All crater floor outcrops are igneous rocks, dominantly ultramafic to mafic in composition, displaying variable degrees of aqueous alteration3. For our analysis, we consider an igneous basalt, two ultramafic cumulates and an igneous andesite, see Fig. 1, which were characterized and sampled by Perseverance during the crater floor campaign2, and are part of the collection to be returned to Earth. The composition of the rocks from Jezero crater base has been assessed in situ using the Planetary Instrument for X-Ray Lithochemistry (PIXL)28, see Supporting Information Table 1.

Igneous rocks sampled at Jezero crater floor by Perseverance during the Crater floor campaign. (a) Igneous basalt (Bellegarde abraded patch and samples Montdenier and Montagnac). (b) Ultramafic cumulate (Dourbes abraded patch and Salette and Coulettes). (c) Ultramafic cumulate (Quartier abraded patch and samples Robine and Malay). (d) Igneous andesite (Alfalfa abraded patch and samples Hahonih and Atsah). Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

To investigate the effect of the incident radiation on the rock, we use the fully integrated particle physics Monte Carlo simulation package FLUKA29. FLUKA is a well-validated Monte Carlo simulation code widely used for nucleogenesis, radiation transport, and particle interactions with matter which has been extensively benchmarked against experimental data and is used in various scientific and engineering applications such as high-energy physics, space radiation studies and shielding design. It includes comprehensive nuclear interaction models, such as PEANUT (Pre-Equilibrium Approach to Nuclear Thermalization), which accurately describes the entire nuclear reaction chain. This simulation code allows calculating the cosmogenic nuclide production by tracking individual particles and their secondary cascade particles in the target rock. Only protons and neutrons with energies > 20 MeV for protons and > 4 MeV for neutrons can produce cosmogenic isotopes through spallation nuclear reactions5,21.

In our analysis we focus on neutrons because the incident flux on the surface of Mars is about two orders of magnitude greater than the proton incident flux30,31, but similar studies can be performed for protons. We consider as incident flux, the present-day incident spectral density of neutron flux measured on Mars by the Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) instrument at Gale crater, Mars31, see supporting information Fig. 1. We calculate the yields for a minimum exposure period of 100,000 years (0.1 Ma). We can utilize these estimates to project the effects over longer exposure periods, as proposed in previous studies5. However, significant uncertainties remain regarding past atmospheric composition, resurfacing processes, variations in rock composition, and fluctuations in cosmic radiation influx, making precise extrapolation challenging.

Results

Cosmogenic production of nuclides with half-lives greater than 100,000 years, including stable isotopes

In the context of cosmogenic nuclide formation, the yield refers to the production rate of a specific nuclide per unit time, per unit mass of the target material, under cosmic ray exposure. It quantifies how efficiently a given nuclide is produced due to interactions between high-energy radiation and the atoms in a material. Figure 2 shows the accumulated cosmogenic production yield over a period of 100,000 years, on the top 0.5 cm of rock for target (a). We have only marked the production of nuclides with half-lives greater than 100,000 years (X) or stable ( +). This chart type summarizes the production yield of all the products of cosmogenic reactions, arranged by neutron number (N) and proton number (Z) for a constant incident neutron flux, over 100,000 years. Our simulations show that for this incident energy range, only nuclides up to Co are produced. In general terms, these reactions favour the formation of the lighter stable isotopes of H, C, O and the heavier of He, N. Due to their comparable rock composition and density, targets b, c, and d yield similar results (see Supporting Information, Figs. 2–4).

Vertical profiles of the production rate and accumulated production yield.

Figure 3 shows the vertical depth profile of the production yields of different nuclides for target (a), accumulated over a period of 100,000 years. The same calculation has been performed for all the other rock types producing similar results, see supporting Information Figs. 2,3 and 4. The calculated production yields over 100,000 years, for all elements up to Z = 27 (cobalt), and for all targets (a-d), from the surface (0.5 cm, as in Fig. 2) to a depth of 55 cm are included in the supporting information data files.

The accumulated production yield (#nuclei/g) over 100,000 years (0.1 Ma) of long-lived radionuclides such as \(^{10}Be\) (t₁/₂ = 1.39 Ma), \(^{26}Al\) (0.72 Ma), \(^{36}Cl\) (0.301 Ma), and \(^{41}Ca\) (0.104 Ma) reaches ~ 10⁸–10⁹ nuclei per gram. This has been calculated assuming the incident neutron flux measured by RAD for target (a).

The most produced isotope is \({}^{1}H\) (\({\sim 10}^{11}\) nuclei/g for 100,000 years). The \({}^{1}H\) production yield curves show their maximum at around 10 – 11 cm depth. These \({}^{1}H\) isotopes are easily formed as they are just constituted by one proton. The samples acquired by the rover have a depth of about 5 cm. Within the top 5 cm (which is the length of the sampled rocks), there may be a detectable difference of about 30% of \({}^{1}H\), caused by surface radiation exposure during the last 100,000 years.

In the case of long-lived radionuclides conventionally used for exposure dating (e.g., \(^{36}Cl\), \(^{26}Al\), and \(^{10}Be\)) there is also a significant production yield, see (Fig. 4).

The production yields of the isotopes \(^{12}C\), \(^{14}N\) and \(^{15}N\) exhibit their peaks around a depth of about 10 cm, \(^{13}C\) isotopes show the highest peak of production at around 1–2 cm depth. The isotopes \(^{12}C\), \(^{13}C\) and \(^{15}N\) show a maximum production yield of \({10}^{10}\) nuclei/g whilst \(^{14}N\) isotopes are produced in much lower yields. It is also remarkable the high rate of \(^{27}Al\) and \(^{23}Na\) production in the top 10 cm of the igneous samples and of \(^{36}Cl\) at 30 cm.

Similar vertical profiles were previously calculated for C and N stable isotopes for a standard (generalized) rock with lower density (2.5 g/cm3)5. In that case the yields were maximised at depths of about 10 – 40 cm due to the different rock composition, lower density and the slightly different modelled incident flux. We have simulated with our model the impact of this flux on the standard average Martian rock composition, obtaining similar yields (See Supporting Information, Figs. 5 and 6 and Table 2).

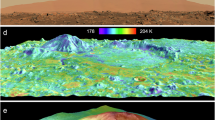

(Left) Carbon isotopic composition versus rock depth after 100 Ma (million years), 1.4 Gy (billion years) and 2.5 Gy of exposure to the neutron flux measured by RAD for a target (a) rock. The initial total carbon content was set to 10, 30 and 100 ppm with \(\delta^{13}C\) at -20 ‰. (Right) Nitrogen isotopic composition versus rock depth after 100 Ma (purple curve), 1.4 Gy (green curve) and 2.5 Gy (blue curve) of exposure to the neutron flux measured by RAD, for a target (a) rock. The initial total nitrogen content was set at 10 ppm with \(\delta {}^{15}{N}_{0}\)= 0 ‰.

Extrapolation of the accumulated effect on \({\varvec{\delta}}{}^{13}{\varvec{C}}\) and \({\varvec{\delta}}{}^{15}{\varvec{N}}\) over time

Using the calculated yields, we can extrapolate the cosmogenic production for longer exposure times. For instance, for a rock exposed to this radiation during a period of 100 million years, at the depth of maximal yield, there would be a net production of \({1.43\times10}^{13}\) \(^{12}C\)/g of rock, i.e. 0.285 ppb in mass, and of \({3.93\times10}^{12}\) \(^{15}N/g\), i.e. 0.097 ppb. Assuming that this can be extrapolated to 1 Gy, this would lead to the production of 2.85 ppb or \(^{12}C\) and 0.978 ppb of \(^{15}N\) in 1 Gy.

To illustrate the potential impact of cosmogenic nuclide production on \(\delta {}^{13}C\) and \({}^{15}N\), following the approach proposed by Pavlov et al. (2014), we have calculated the \(\delta {}^{13}C\) produced by the incident neutron flux measured by RAD at Gale crater on the rocks with the composition measured by PIXL at Jezero crater, see Fig. 5 -left. We derived whole rocks’ total carbon isotopic composition as a function of depth, time of exposure to cosmic radiation, and the original (indigenous) carbon abundance. Assuming a rock with an initial \(\left(\frac{{}^{13}C}{{}^{12}C}\right)\)=0.0112372, i.e., the standard terrestrial reference22, we can estimate \(\delta {}^{13}C=\left[\frac{P\left({}^{13}C\right) \times t}{{N}_{0}\left({}^{12}C\right)}\times \left(\frac{{}^{13}C}{{}^{12}C}\right)\right]\times 1000\). We vary the carbon content of the original rock from 10 to 100 ppm (i.e. 10 to 100 × 10−6 μg/g) then \({N}_{0}\left({}^{12}C\right)\)= 10 to 100 × 10−6/12 × 6.02323 #nuclei/gram. In our case \(P\left({}^{13}C\right)\) is the production yield shown above, accumulated over a period of 100,000 years. We have also applied the same procedure to calculate \(\delta {}^{15}N\), \(\delta {}^{15}N=\left[\frac{P\left({}^{15}N\right) \times t}{{N}_{0}\left({}^{14}N\right)}\times \left(\frac{{}^{15}N}{{}^{14}N}\right)\right]\times 1000\), where \(P\left({}^{15}N\right)\) is the production yield accumulated per 100,000 years, as before. The initial total nitrogen content was set to 10 ppm. In this case an initial rock of \(\left(\frac{{}^{15}N}{{}^{14}N}\right)\) =0.003676 is assumed32, (i.e., \(\delta {}^{15}{N}_{0}\) at 0 ‰), see Fig. 5 -right. These results are comparable to those obtained previously by Pavlov (2014) for a generalized, standard Martian rock composition.

If this is extrapolated to longer periods, then t is a factor 1000 (to calculate the total production yield over 100 Ma), 14,000 (to calculate the total production yield over 1.4 Gy), and 25,000 (to calculate the total production yield over 2.5 Gy). However, this extrapolation is definitively inaccurate and only represents an upper limit, as surface materials have likely been protected by other materials and have undergone erosion over these geological time scales. Additionally, carbon retention and mobility on Mars over such an extended period may have been highly variable, introducing uncertainties in any linear extrapolation. Furthermore, the Martian atmosphere has likely evolved through different stages within this timeframe, which would have affected the incident flux.

Discussion

The Mars Sample Return collection offers a unique opportunity to study isotopes generated on Mars due to cosmic ray exposure. Once the samples are brought to Earth, a detailed comparative analysis of elements and their isotopes will be crucial to differentiate cosmogenic reactions from other geological, atmospheric, or potential biological processes. Measuring all cosmogenic isotopes and analysing their ratios will aid in determining exposure times, modelling the evolution of the Martian atmosphere, and exploring other planetary cycles. To achieve this, simulations of nuclear reactions induced by cosmic rays on the rock compositions will be essential for correctly interpreting isotope distributions and defining the upper and lower limits of isotope concentration resulting from radiation exposure alone.

For illustration, in this work, we have performed Monte Carlo simulations, with \({10}^{5}\) incident particles per study case and energy range, to examine the nucleogenesis reactions induced by the neutron flux measured by RAD at Gale crater on Mars, focusing on their effects on rocks collected by Perseverance at Jezero crater floor. Future simulations should assess the radiation effects on samples acquired from the top of the delta, the crater margin unit and the crater rim as well as on the regolith samples.

We have calculated the cosmogenic production rates of all elements up to Z = 27 (cobalt) in the igneous rocks of the crater floor, finding almost no differences among them. This is understandable given the similitude in composition and density. Our simulations show that for this incident energy range, only nuclides up to Co are produced with significant yields. \(^{1}H\), \(^{2}H\) and \(^{4}He\) have the highest yields, followed by \(^{56}Fe\), \(^{28}Si\), \(^{16}O\), \(^{12}C\), \(^{13}C\), \(^{15}N\) and \(^{27}Al\). For these types of rocks, assuming an exposure to the RAD measured neutron radiation during a period of 100 million years, cosmogenic reactions would lead to the production of \({1.43\times10}^{13}\) \(^{12}C/g\) of rock, i.e. 0.285 ppb, and of \({3.93\times10}^{12}\) \(^{15}N\)/g, i.e. 0.097 ppb. Notice that our simulations show how the isotopic ratios of different elements may vary within the 5 cm of the sampled rock. This suggests that the future mars sample return collection shall include a comparative analysis of the vertical isotopic concentration in the samples.

The natural abundances of major rock-forming elements are a critical consideration when evaluating whether cosmogenic contributions can be detected or meaningfully separated from indigenous isotopic signatures. Our work provides a comprehensive framework with quantitative estimates, enabling identification of elements for which cosmogenic contributions are negligible and do not require further correction. For major elements such as Al, Fe, and Si, the indigenous concentrations overwhelmingly exceed the cosmogenic component, making the latter effectively undetectable in bulk analyses. Nevertheless, as the precise mineralogy and grain-scale composition of returned Martian samples are not yet known, some micro-domains could exhibit sufficiently low indigenous concentrations of a given element to reveal enhanced relative contributions from cosmogenic production. Additionally, rocks may present surface coatings or compositional heterogeneities that differ from the assumed homogeneous rock composition. Our simulations adopt a generalized homogeneous composition, but future analyses incorporating specific mineral compositions—once actual sample data are available—will be necessary to rule out or quantify any isotopic shifts induced by cosmogenic processes, consistent with perspectives outlined in prior Mars sample studies18.

The concentration of stable cosmogenic nuclides increases linearly with exposure time whereas unstable cosmogenic radionuclides start to decay as soon as they are produced. Our simulation illustrates how unstable isotopes, such as \(^{36}Cl\), are produced significantly. Notice that \(^{36}Cl\) is radioactive and decays to \(^{36}Ar\) (stable) and \(^{36}S\) (stable) via beta decay. This decay has a half-life of T1/2 = 301,000 years. The \(^{36}Cl\)-\(^{36}Ar\) cosmic ray exposure time calculation is a method used in cosmochemistry and planetary science to determine how long a sample (such as a meteorite or rock) has been exposed to cosmic rays. In the absence of other processes, the accumulation of \(^{36}Ar\) is proportional to the time the sample has been exposed. However, our simulations show that \(^{36}Ar\) (stable) can also be produced directly. At the surface, it is produced at comparable rates and thus the production yields of all isotopes need to be accurately simulated to date the samples. The simulation shows that also \(^{10}Be\), whose half-life is T1/2 ~ 1.39 million years, is formed in-situ. This decay process may be good for dating the exposure of the crater floor. The isotopic ratio \(^{26}Al\)/\(^{27}Al\) can also be used to date, as the half-life of this decay is about 717,000 years. However, our simulations show that both the unstable \(^{26}Al\) and the stable \(^{27}Al\) are directly formed by cosmogenic reactions in these rocks. The ratio \(^{40}K\)/\(^{40}Ar\) can be used for dating the crater floor unit as this decay has a half-life about T 1/2 ~ 1.25 billion years. This method was used for instance by Curiosity, to date in-situ the cosmic-ray exposure ages for rocks within Gale Crater18. In the case of long-lived radionuclides conventionally used for exposure dating in extraterrestrial samples (e.g., \(^{41}Ca\) \(^{36}Cl\), \(^{26}Al\), and \(^{10}Be\)) measurable shifts may be studied33,34. Modern AMS (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) systems achieve an abundance sensitivity as low as ~ 10−15 and detection limits of ~ 105 atoms/g or better for \(^{10}Be\) (t₁/₂ = 1.39 Ma), \(^{26}Al\) (0.72 Ma), \(^{36}Cl\) (0.301 Ma), and \(^{41}Ca\) (0.104 Ma)35. Based on our FLUKA simulations, the predicted cumulative production over 105 years (0.1 Ma) is ~ 10⁸ nuclei/g for 1\(^{10}Be\) and \(^{41}Ca\), and 1–6 × 10⁹ nuclei/g for \(^{26}Al\) and \(^{36}Cl\). These results indicate that these cosmogenic nuclides in Martian samples would be readily detectable with existing instrumentation. Analysis of Martian Sample Return (MSR) materials is anticipated within the coming decade, and further advances in AMS technology may improve sensitivity, potentially enabling the detection of additional cosmogenic isotopes. Future studies should compare these emerging instrumental capabilities with the production yields reported here.

For stable isotopes, including C and N, our simulations also provide quantitative estimates of spallation-induced shifts. In samples with low concentration of carbon and nitrogen (ppm), cosmogenic reactions can alter the isotopic ratios of these elements of astrobiological interest. For an initial carbon content of 10 ppm with \(\delta^{13}C\) = −20 ‰, cosmogenic reactions would alter this ratio to \(\delta^{13}C\) to + 10 ‰ and + 40 ‰ for 1.4 Gy and 2.5 Gy, respectively. This range of variability is compatible with the \(\delta^{13}C\) measured in-situ by Curiosity rover elsewhere on Mars, at Gale crater. In rocks with higher carbon content, such as carbonate-rich rocks (like the ones that Perseverance may acquire from the delta and margin unit), the isotopic ratios would be essentially unaffected by the long-term exposure to cosmic rays and cosmogenic nuclide reactions.

Our study has inherent limitations typical of such simulations. We assumed a uniform rock composition; however, natural variability within rock grains can lead to differing isotope production yields at millimetric and gram scales. We also assumed a constant incident flux over the past 100,000 years. For longer geological studies, models should account for potential variations in incident flux, but uncertainties regarding the Martian atmosphere’s composition and density, as well as solar activity, complicate this. Previous studies, such as the one implemented by Pavlov et al. (2014), have faced similar limitations. While the bulk rock composition remains unchanged in this kind of simulations, a more realistic approach for long, geological-time scale, simulations should incorporate the decay of newly formed cosmogenic products. In our simulation, evaluating the impact up to 100,000 million years, we consider this contribution, which is on the order of ppb, negligible compared to the primary elements measured by PIXL in the rock. Future simulations may also investigate the role of overlaying materials which may alter the incident spectral energy flux of ionizing particles during a certain period and then surface retreat due to erosion.

In planetary science and cosmochemistry, isotopic systems involving cosmogenic nuclides are widely used to determine the exposure ages of rocks, meteorites, and planetary surfaces to cosmic rays. Several isotope combinations are commonly employed, each with specific applications depending on the target material and its composition. Our simulation underscores that, when multiple isotopes are generated in situ by cosmogenesis, a comprehensive approach is required, involving collective analysis of all relevant isotopic systems and parallel simulations of cosmogenic reactions. This will ensure that the contributions of direct production and decay pathways are disentangled, leading to more accurate exposure age determinations. The estimated yields documented here, allow to produce upper and lower bounds of isotope production, which can be used to define the instrumentation requirements for the future analysis of the Martian samples on Earth.

Materials and methods

Target rock composition

The bulk composition of the rocks sampled by Perseverance has been investigated in situ with the Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry (PIXL)28. Before every sample acquisition, an abrasion is produced in the same rock, see Fig. 1, and the composition is studied with PIXL placed close to the abraded surface. Table 1 (supporting information) summarizes the rock compositions of the abrasion patch; all data are described in the Sample Initial Reports. For each study case, the compositional per cent must be rescaled with respect to the total and given as input, as target composition, to FLUKA. We include in Table 1 (supporting information) the corresponding rock density.

FLUKA assumes that radiation propagates through homogeneous media. When defining the material of a target, only the stoichiometry and the density of each component is given. This defines the atom density per unit volume for each atomic species.

Incident radiation flux

Direct GCRs can penetrate up to 1–2 m depth4. Only protons and neutrons with energies > 20 MeV for protons and > 4 MeV for neutrons can produce cosmogenic isotopes through spallation nuclear reactions5. In our analysis we focus on neutrons because the incident flux is about two orders of magnitude greater than the proton incident flux36, but similar studies can be performed for protons.

Here we consider the present-day incident neutron flux measured on Mars by the Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) instrument within the energy range 7 to 900 MeV31. For the rest of the energy range, from 4 to 7 MeV and from 900 MeV to 8 GeV, we complement this flux with the PHITS model37,38. RAD is sensitive to neutrons arriving from all directions so the data is averaged over 4 \({\varvec{\pi}}\)36. Here we consider the flux of neutrons that impacts rocks from the top 2 \({\varvec{\pi}}\) solid angle (see Fig. 1 supporting information).

Monte Carlo simulation

FLUKA is a general-purpose Monte Carlo code able to describe the transport and interaction of any particle and nucleus type in complex geometries over an energy range extending from thermal neutrons to ultra-relativistic hadron collisions29. FLUKA is particularly strong in simulating high-energy hadronic interactions, which are important for understanding the production of cosmogenic nuclides, making it more suited than other codes for processes involving cosmic-ray interactions in the planet´s materials. FLUKA is specifically designed to model the production of secondary particles, such as neutrons and other nucleons, which are essential for the formation of cosmogenic nuclides in materials exposed to cosmic rays.

While GEANT4 and MCNPX are more commonly used in planetary and cosmogenic nuclide research, FLUKA has been extensively benchmarked against experimental data in areas directly relevant to our study, including hadron-induced spallation, neutron transport, and isotope production. For example, FLUKA has been successfully applied and validated in studies of underground cosmogenic neutron production39 and in experimental measurements of cosmogenic neutrons40. Its predictions have also been cross-checked with GEANT4 and MCNP in space radiation simulations, such as modelling the lunar radiation environment41. Additional experimental validations of FLUKA include carbon-ion radiotherapy monitoring42, response functions of organic liquid scintillators for high-energy neutrons43, and induced radioactivity at high-energy accelerators44. Collectively, these studies demonstrate FLUKA’s reliability for simulating neutron-induced cosmogenic processes relevant to Mars sample return analyses.

Our model consists of a uniform solid cylindrical rock target that is 55 cm long and has a radius of 50 cm, free of air pores. The target is divided into 65 sections, with the top layers (0 to 10 cm) being thinner (0.5 cm thick), and the remaining sections down to 55 cm being 1 cm thick. Sixty-five virtual detectors were placed, one for each section, to register the production of the isotopes due to spallation nuclear reactions with the incoming neutrons. An incident neutron beam with a radius of 1 cm propagated perpendicular to the centre of the target was applied. To guarantee statistical significance, each Monte Carlo simulation tracks \({10}^{5}\) incident particles. The target was surrounded by vacuum and enclosed by a blackbody, with trajectories terminating at the boundaries of the blackbody to prevent backscattering of escaping particles. The target composition is maintained constant during the simulation.

We first validated our FLUKA simulation using the Standard Martian Rock elemental composition (density 2.5 g cm⁻3), as adopted by Pavlov et al.5 in their GEANT simulations of GCR and SCR interactions with the Martian atmosphere. Our results are consistent with previous reports (see Supporting Information Figs. 5 and 6), with a key distinction: we use the current incident flux measured by the radiation assessment detector (RAD) directly at the Martian surface, whereas Pavlov et al.5 simulated radiation transfer from a nominal GCR and SCR spectrum at the top of the atmosphere. In their model, GCR particles were considered in the 20 MeV–10,000 GeV range, and SCR particles in the 1 MeV–2 GeV range, with the incident flux and energy distribution at the top of the Martian atmosphere adopted from previous models. Pavlov et al. calculated an average GCR flux of 0.77 nucleons cm⁻2 s⁻1 at the surface of Mars, whereas RAD in-situ measurements at Gale crater, on Mars, indicate 1.84 nucleons cm⁻2 s⁻1, corresponding to a factor of 2.4 higher flux at the surface. Here, nucleons refer to the total number of protons and neutrons. Consequently, the production yield as a function of depth in Pavlov et al.5 is lower by roughly a factor 2.4 (Supporting Information, Fig. 6). Applying a scaling factor of 2.4 to the production yields calculated with GEANT confirms that the production yields are similar, with a progressive decay with depth from approximately 10–20 cm downward.

Data availability

The calculated production yields over 100,000 years, for all elements up to Z = 27 (cobalt), from the surface to a depth of 55 cm are included in the supplementary dataset as separate .xlsx file for all the target types (a, b, c, d and standard). The stability and half-lives data were extracted from the National Nuclear Data Center database, https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/nudat/.

References

Wiens, R. C. et al. Compositionally and density stratified igneous terrain in Jezero Crater, Mars. Sci. Adv. 8 (34), eabo3399. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo3399 (2022).

Simon, J. I. et al. Samples collected from the floor of Jezero Crater with the Mars 2020 perseverance rover. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 128 (6), e2022JE007474. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007474 (2023).

Herd, C. R. et al. Sampling Mars: Geologic context and preliminary characterization of samples collected by the NASA Mars 2020 perseverance rover mission. PNAS https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2404255121 (2024).

Pavlov, A. A. et al. Degradation of organic molecules in the shallow subsurface of mars due to cosmic ray irradiation. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL052166 (2012).

Pavlov, A. A. et al. Alteration of carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition in martian surface rocks due to cosmic ray exposure. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119 (6), 1390–1402. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JE004615 (2014).

Quantin-Nataf, C. et al. The complex exhumation history of Jezero Crater floor unit and its implications for Mars sample return. J. Geophys. Res. Planets https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007628 (2023).

Goudge, T. A. et al. An analysis of open-basin lake deposits on Mars: Evidence for associated lacustrine deposits and post-lacustrine modification processes. Icarus 219 (1), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2012.02.027 (2012).

Schon, S. et al. An overfilled lacustrine system and progradational delta in Jezero Crater, Mars: Implications for noachian climate. Planet. Space Sci. 67, 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2012.02.003 (2012).

Shahrzad, S. et al. Crater statistics on the dark-toned mafic floor unit in Jezero Crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46 (5), 2408–2416. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL081402 (2019).

Warner, H. et al. Crater morphometry on the mafic floor unit at Jezero Crater, Mars: comparisons to a known basaltic lava plain at the InSight landing site. J. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089607 (2020).

Marchi, S. A new Martian Crater chronology: Implications for Jezero Crater. Astron. J. 161 (4), 187. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/abe417 (2021).

Rubanenko, L. et al. Challenges in Crater chronology on Mars as reflected in Jezero Crater. Mars Geol. Enigmas, Chapter 5, 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820245-6.00005-7 (2021).

Leshin, L. A. et al. Volatile, isotope, and organic analysis of Martian fines with the Mars curiosity rover. Science 341 (6153), 1238937. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238937 (2013).

Webster, C. R. et al. Isotope Ratios of H, C, and O in Martian atmospheric CO2 measured by curiosity. Science 341, 260–263 (2013).

Lal, D. Cosmogenic and nucleogenic isotopic changes in Mars: rates and implications for the evolutionary history of the Martian Surface. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57 (19), 4627–4637. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(93)90188-3 (1993).

Rao, M. Neutron capture Isotopes in the Martian Regolith and implications for Martian atmospheric noble gases. Icarus 156 (2), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.2001.6809 (2002).

Cassata, W. S. In situ dating on Mars: A new K-Ar method utilizing cosmogenic argon. Acta Astronaut. 94 (1), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2013.07.040 (2014).

Farley, K. A. et al. In situ radiometric and exposure age dating of the Martian surface. Science 343 (6169), 1247166. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1247166 (2014).

Vasconcelos, P. M. et al. Discordant K-Ar and young exposure dates for the Windjana sandstone, Kimberley, Gale Crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 121 (10), 2176–2192. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JE005017 (2016).

Martin, P. E. et al. Billion-year exposure ages in gale crater (Mars) indicate mount sharp formed before the amazonian period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 554, 116667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116667 (2021).

David, J. C. & Leya, I. Spallation, cosmic rays, meteorites, and planetology. Progress Particle Nuclear Phys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2019.103711 (2019).

Craig, H. Isotopic standards for carbon and oxygen and correction factors for mass-spectrometric analysis of carbon dioxide. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 12 (1–2), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(57)90024-8 (1957).

Franz, H. B. et al. Indigenous and exogenous organics and surface-atmosphere cycling inferred from carbon and oxygen isotopes at Gale Crater. Nat. Astron. 4 (5), 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0990-x (2020).

House, C. H. et al. Depleted carbon isotope compositions observed at Gale Crater Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (4), e2115651119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2115651119 (2022).

Schoell, M. Methane 13C/12C isotope analyses with the SAM-EGA pyrolysis instrument suite on Mars curiosity rover: A critical assessment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (30), e2205344119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2205344119 (2022).

Stern, J. C. et al. Organic carbon concentrations in 3.5-billion-year-old lacustrine mudstones of Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (27), e2201139119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2201139119 (2022).

Burtt, D. G. et al. Highly enriched carbon and oxygen isotopes in carbonate-derived CO2 at Gale Crater, Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121 (42), e2321342121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2321342121 (2024).

Allwood, A. C. et al. PIXL: Planetary instrument for X-Ray lithochemistry. Space Sci. Rev. 216 (8), 134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00767-7 (2020).

Ahdida, C. et al. New capabilities of the FLUKA multi-purpose code. Front. Phys. 9, 788253. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.788253 (2022).

Matthiä, D. et al. The radiation environment on the surface of Mars - Summary of model calculations and comparison to RAD data. Life Sci. Space Res. 14, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lssr.2017.06.003 (2017).

Hassler, D. M. et al. ‘Mars’ surface radiation environment measured with the mars science laboratory’s curiosity rover. Science 343 (6169), 1244797. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244797 (2014).

Mariotti, A. Atmospheric nitrogen is a reliable standard for natural 15N abundance measurements. Nature 303 (5919), 685–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/303685a0 (1983).

Kubik, P. et al. Determination of cosmogenic 41Ca in a meteorite with tandem accelerator mass spectrometry. Nature 319, 568–570. https://doi.org/10.1038/319568a0 (1986).

Nishiizumi, K. et al. Solar cosmic ray records in lunar rock 64455. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73 (7), 2163–2176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2008.12.021 (2009).

Hotchkis, M. et al. Accelerator mass spectrometry analyses of environmental radionuclides: Sensitivity, precision and standardisation. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 53 (1–2), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-8043(00)00186-X (2000).

Flores-McLaughlin, J. Radiation transport simulation of the Martian GCR surface flux and dose estimation using spherical geometry in PHITS compared to MSL-RAD measurements. Life Sci. Space Res. 14, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lssr.2017.07.007 (2017).

Niita, K. et al. PHITS—a particle and heavy ion transport code system. Radiat. Meas. 41 (2006), 1080–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radmeas.2006.07.013 (2006).

Sato, T. et al. Particle and Heavy ion transport code system, PHITS, Version 2.52. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 50 (9), 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2013.814553 (2013).

Empl, A. et al. A fluka study of underground cosmogenic neutron production. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2014 (08), 064–064. https://doi.org/10.1088/1475-7516/2014/08/064 (2014).

Shinoki, M. et al. Measurement of the cosmogenic neutron yield in super-kamiokande with gadolinium loaded water. Phys. Rev. D 107 (9), 092009. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.107.092009 (2023).

Zaman, F. A. et al. Modeling the lunar radiation environment: A comparison among FLUKA, Geant4, HETC-HEDS, MCNP6, and PHITS. Space Weather 20 (8), e2021SW002895. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021SW002895 (2022).

Ochoa-Parra, P. et al. Experimental validation of a FLUKA Monte Carlo simulation for carbon-ion radiotherapy monitoring via secondary ion tracking. Med. Phys. 51 (12), 9217–9229. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.17408 (2024).

Ghavami, A. & Tajik, M. Validation of the FLUKA code to simulate response functions of organic liquid scintillator for high-energy neutrons. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 57 (2), 103198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2024.09.001 (2025).

Brugger, M. et al. Validation of the FLUKA Monte Carlo code for predicting induced radioactivity at high-energy accelerators. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 562 (2), 814–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2006.02.062 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank M.-T. Álvarez for support with FLUKA.

Funding

A. C. G. H. was supported by an INTA training fellowship. M.-P.Z. was supported by grant PID2022-140180OB-C21 funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE. J.M.-T. acknowledges the partial support of PID2023-146856NB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF, EU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-P. Z. devised and coordinated the project and defined the simulation inputs. A.C.G.-H. implemented the computational simulation with FLUKA. M.-P. Z., J. M.-T. and A.C.G.-H analysed the data. M.-P. Z. wrote the initial manuscript with inputs from J. M.-T. and A.C.G.-H. All authors provided critical feedback and helped writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zorzano, M.P., García-Herrera, A.C. & Martín-Torres, J. Recent production rates of cosmogenic nuclides in the igneous rocks of Jezero crater floor, Mars. Sci Rep 16, 3884 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33031-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33031-5