Abstract

External ear size varies dramatically across animals, in part because of its role in thermoregulation: small ears conserve heat, while large ears dissipate heat. Genetic factors influencing ear size are known in several domesticated species but remain unexplored in dogs. We used whole-genome sequences aligned to canFam4 to perform an across-breed genome-wide association study (GWAS) for drop ear length. We identified a significant locus on canine chromosome (CFA) 10, intergenic to MSRB3 and HMGA2. The position of the lead variant (chr10:8,612,500, P = 1.85 × 10− 17) is evolutionarily conserved and, in humans, interacts with an MSRB3 enhancer. Given that this locus governs ear carriage in dogs, which was uniform in our cohort, we conducted a GWAS using prick- and drop-eared breeds to disentangle genetic determinants of ear size and carriage. Our results indicate that two independent variants on CFA10 are associated with ear carriage, but only a recombinant haplotype containing both derived alleles results in drop ears. The allele for ear size arose on the recombinant haplotype and this tri-allelic combination predominates in breeds having the largest drop ears. Conversely, breeds having the ancestral haplotype have small, erect ears. Our findings suggest that each derived variant may act independently to increase ear size, which in turn influences ear carriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

External ear size is a distinctive phenotypic trait that exhibits considerable variation across species and can play a critical role in thermoregulation1. Animals inhabiting hot environments tend to have large, highly vascularized ears that facilitate heat dissipation, such as the jackrabbit2. In contrast, species adapted to cold climates have smaller ears that conserve body heat, like the Arctic hare3. This thermoregulatory pattern is also evident in domesticated animals. Production animals from hot climates often exhibit long, drop ears, as seen in Brahman cattle4 and Awassi sheep5. Domesticated dogs are unique in that selective pressures for ear morphology are not always applied for functionality, but often for aesthetic preference. Still, similar trends are observed: breeds native to the desert (e.g., Pharoah Hound, Rhodesian Ridgeback) typically have larger ears, whereas northern breeds (e.g., Siberian Husky, Great Pyrenees) tend to have smaller ears.

Variation in ear size has been attributed to a diverse set of genes across multiple domesticated species, reflecting the involvement of distinct biological pathways. In cattle and swine, mutations in IBSP4 and PPARD6, respectively, have been shown to increase ear size. Multiple genes have been associated with ear size in sheep, including GATA65, DCC7, and HMX18,9. HMX1 is also associated with ear shortening in Highland cattle10. Notably, MSRB3 stands out as the only gene to be associated with ear size in several species, namely pigs, sheep, and goats11,12,13,14, highlighting its role as a conserved regulator of ear development15,16.

The genetic basis of ear size in dogs has not been the subject of direct study. To date, only a retrogene insertion of FGF4 on canine chromosome (CFA) 12, which underlies chondrodystrophy, has been associated with larger ears17,18. Ear carriage, on the other hand, has been extensively studied in dogs, likely because of its intriguing relationship with tamability and domestication19. Genome-wide studies comparing prick- and drop-eared breeds consistently point to a selective sweep on CFA10 that encompasses MSRB3 and HMGA2 (OMIA 000319–9615)18,20,21,22. This region is also strongly associated with body size (OMIA 001968–9615)22,23. We hypothesized that loci contributing to ear length in dogs could be identified using a population that is uniform in ear carriage. In this investigation, we performed a quantitative genome-wide association study (GWAS) for ear length using high-coverage, whole-genome sequences from breeds for which drop-ear is a defining trait.

Results

Ear length

To identify genomic regions associated with ear length, we performed a quantitative GWAS with 272 dogs from 76 breeds (Supplementary Table 1) and 5,091,547 single nucleotide variants (SNVs) called against the dog reference genome UU_Cfam_GSD_1.0, canFam424. Each breed was assigned to one of five categories based on breed standard ear lengths, illustrated in Fig. 1A. On CFA10, 62 SNVs between 8.38 and 8.81 Mb surpassed Bonferroni significance (Figs. 1B-D; Supplementary Table 2). The lead SNV was g.8612500T > C (P = 1.85 × 10− 17), which remained the lead in (1) a quantitative GWAS with an unpruned dataset of 8,016,060 SNVs and (2) a binary GWAS using 219 dogs: 25 breeds with short ears (above the jawline) and 37 having long ears (below the jawline). The latter GWAS (Supplementary Fig. 1) also yielded a significant locus upstream of RUNX3, associated with pheomelanin intensity in dogs25, likely resulting from the overrepresentation of red coat color in long-eared breeds. Human embryonic stem cell chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) data26, visualized with the 3D Genome Browser, revealed that the locus encompassing the homologous position (Chr12:65,723,786 in hg38) directly interacts with an enhancer of MSRB3 (Fig. 1E). The lead SNV for ear length is highly conserved across placental mammals (PhyloP = 3.58). ChIP-seq data viewed in the UCSC Genome Browser (ReMap Atlas) indicate that the homologous human locus contains a cis-regulatory element, with a ReMap density of 45 occupied by 13 different transcription factors and 4 chromatin remodelers (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Quantitative GWAS for ear length across 76 drop-eared breeds. (A) Representative breeds are shown for each of the phenotypic categories. (B) Manhattan plot illustrating GWAS results. The -log10 P-values for 5,091,547 SNVs are plotted on the y-axis against chromosome position (x-axis, canFam4). Red line indicates Bonferroni significance (P = 9.82 × 10− 9). (C) Q-Q plot shows observed vs. expected -log10 P-values and genomic inflation factor (λ). (D) Corresponding regional plot depicts pairwise LD (r2) with chr10:8,612,500 (purple diamond) (E) Arc plot of the human syntenic region depicting chromatin interactions were visualized using the 3D Genome Browser from Hi-C data generated from human embryonic stem cells. Relevant interacting regions are marked in yellow, with the corresponding human position of the long ear lead SNV indicated by an asterisk (*). The two MSRB3 isoforms are shown, with MSRB3A on top and MSRB3B on the bottom.

Ear carriage

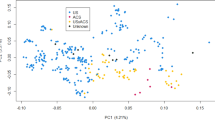

Because the region identified on CFA10 is also known to govern ear carriage18,20,22, we sought to dissect the contribution of this locus to ear morphology. We first conducted a GWAS for prick vs. drop ears using 826 dogs from 229 breeds and 8,231,585 SNVs (Fig. 2A). Significant SNVs within the strong signal on CFA10 ranged from 6.96 to 9.93 Mb. A regional Manhattan plot (Fig. 2B) revealed a broad, indiscriminate signal, suggesting that multiple variants in the locus govern one or more phenotypes.

To disentangle the genetic contribution of variants in this locus, we repeated the GWAS using the lead variant for ear length (g.8612500T > C) and a previously described candidate variant for small body size23 (g.8703415G > A) as covariates. The CFA10 signal was diminished (Fig. 2C), but a regional LD (r2) plot revealed distinct signals at 8.40 and 8.72 Mb, over MSRB3 and HMGA2, respectively (Fig. 2D). The lead SNVs from each signal were not in linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 0.14), suggesting that these variants contribute independently to ear morphology.

We also detected weaker associations at 9.29 Mb on CFA13, 35.49 Mb on CFA32, 18.71 Mb on CFA34, and 34.44 Mb on CFA2 (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table 3). These signals likely stem from allele imbalances across our large multi-breed cohort, as three of the loci mark RSPO2, FGF5, and IGF2BP2, associated with furnishings, hair length, and body size, respectively27. The single significant SNV on CFA32 encodes FGF5 C95F, a causal variant for long coat28.

The stronger, centromeric signal is located within the 3′ UTR of MSRB3 and harbors a SNV (g.8394697C > T, P = 1.24 × 10− 30) that was recently shown to alter MSRB3 expression29. While both alleles are present among 63 wolves, we denoted the C allele as ancestral because it was homozygous in all 4 coyotes and present in the reference genomes of the arctic fox, African hunting dog, and dingo30,31,32. Across our population of 1,404 purebred dogs, the ancestral C allele had a frequency of 31.5% and was predominant in prick-eared dogs (Supplementary Table 4). The lead SNV of the telomeric signal (g.8721822A > G, P = 5.18 × 10− 19) is located within a short interspersed element in intron 3 of HMGA2. Canfam4 possesses the derived allele (A). The ancestral allele (G) had a frequency of 34.2% across our population and also predominated in prick-eared dogs (Supplementary Table 4).

Manhattan plots for ear carriage across 229 breeds. (A) GWAS results are shown for ear carriage, with insets depicting ear carriage phenotypes (left) and a Q-Q plot showing observed vs. expected -log10 P-values (right). Red line indicates Bonferroni significance (P = 8.78 × 10− 9). (B) Corresponding regional plot depicts pairwise LD (r2) with the lead SNV at chr10:8,386,190 (purple diamond). The SNVs used as covariates in panel C are represented as squares and indicated with arrows. (C) GWAS results for ear carriage using lead SNV for ear length and the allele for small body size as covariates, with inset Q-Q plot showing observed vs. expected -log10 P-values. Red line indicates Bonferroni significance (P = 8.78 × 10− 9). (D) Corresponding regional plot depicts pairwise LD (r2) with the lead SNV at chr10:8,397,522 (purple diamond).

Allele frequencies for the ear carriage and size variants in coyotes, wolves, and across breeds are shown in Fig. 3A. Prick-eared breeds more often have ancestral genotypes at these loci and rarely possess both derived alleles for ear carriage. Of note, prick-eared breeds having a high frequency of one derived allele tend to have a very low frequency of the other derived allele. Conversely, drop-eared breeds have derived alleles at both ear carriage loci. Across both loci, the number of derived alleles correlates with ear carriage (Fig. 3B), such that prick-eared dogs have 2 or fewer derived alleles whereas drop-eared dogs have 3 or 4. Additionally, drop-eared breeds having long ears (categories 3–5) nearly always possess derived alleles across all three loci. Short, drop-eared breeds (categories 1 and 2) have lower derived allele frequencies, particularly at the ear length locus.

Derived allele frequencies correlate with ear morphology. (A) Derived allele frequencies for the ear carriage and size variants in coyotes, wolves, and domesticated dogs. The derived allele (A) for g.8721822A > G is reference. Each row represents a breed and shows sample size (n), ear carriage, and ear length categorization (for drop-eared breeds). Columns depict derived allele frequencies with white indicating low allele frequency, and red indicating high allele frequency. (B) The number of derived alleles across the two loci for ear carriage, chr10:8,394,697 and chr10:8,721,822, in 1,404 dogs from 242 breeds. Bars indicate the number of prick- and drop-eared dogs having 0 to 4 derived alleles.

Haplotypes

For 1,402 purebred dogs, we constructed haplotypes for the lead variants of the three identified ear loci and the small body size variant, in order on CFA10: MSRB3 3′ UTR, ear length, small body size, and telomeric ear carriage (Table 1; Supplementary Table 1), with 0 representing the ancestral allele. We detected 11 unique haplotypes, 9 of which were homozygous in at least one individual. All coyotes and 9 wolves possess the ancestral haplotype, 0|0|0|0, along with 77 breeds. The major wolf haplotype 1|0|0|0, harboring only the MSRB3 3′ UTR variant, was present in 32 breeds and predominated in the Basenji and the Ibizan hound. On this background, the HMGA2 mutation arose (1|0|1|0), contributing to short stature in 52 breeds. The 0|0|0|1 haplotype, containing only the telomeric ear carriage variant, was present in 70 breeds. Notably, a haplotype containing both derived ear carriage variants (1|0|0|1) was present almost exclusively in drop-eared breeds. The lead variant for ear length appears to have arisen on this background, forming the 1|1|0|1 haplotype present in 134 breeds, all drop-eared. This variant was also present on a rare haplotype with the HMGA2 mutation, 1|1|1|0, that was homozygous in all three Pekinese.

Correlating with ear length, the 1|1|0|1 haplotype was nearly fixed in breeds having the longest ears, groups 4 (96%) and 5 (99%), and was the major haplotype in group 3 (88%). Breeds with short ears had much lower frequencies of 1|1|0|1: 18% and 51% in groups 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 4A). Using the di statistic, we detected a strong signature of selection over CFA10 in 20 long-eared breeds compared to 15 breeds having prick ears (Fig. 4B). In 15 short-eared breeds compared to the same prick-eared population, we observed a much weaker signal of selection, consistent with the variability in haplotypes that exist in these breeds.

Selection for the 1|1|0|1 haplotype in long, drop-eared dogs. (A) Haplotype frequencies are shown for the predominant drop-ear haplotypes, 1|1|0|1 and 1|0|0|1, across 76 breeds representing all five categories of length. All alternative haplotypes are lumped into one group (Other). (B) Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) di values (y-axis) are shown for 15 short- and 20 long-eared breeds independently compared to 15 prick-eared breeds. Chromosome 10 positions (Mb) are indicated along the x-axis.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted the first genetic analysis focused specifically on ear length in dogs. Through categorization of standard ear lengths in breeds with drop ears, we used a GWAS to identify a single associated locus on CFA10. Notably, this region is strongly linked to ear carriage18,20,21,22; however, ear carriage was uniform across our study cohort.

One variant (g.8612500T > C) was consistently best associated with long ears. This variant lies intergenic to MSRB3 and HMGA2, within a putative cis-acting regulatory element that shows enrichment for transcription factor and chromatin remodeler binding. Hi-C data indicate that the homologous human locus physically interacts to form a loop structure with a sequence in the first intron of MSRB3, upstream of the start site of the MSRB3B isoform33. The intronic sequence has characteristics of an active enhancer, including H3K27Ac modifications34. Interactions between regulatory elements are well-documented, but knowledge of the exact mechanisms by which these interactions influence gene regulation is incomplete35.

MSRB3 catalyzes the reduction of methionine sulfoxide to methionine, thereby mitigating cellular oxidative stress and supporting cellular growth and proliferation36. In addition, MSRB3 plays a critical role in maintaining the structure and function of inner ear hair cells and has been implicated in the regulation of hippocampal volume15,37. MSRB3 deficiency in both murine and human fibroblasts induces cell cycle arrest and suppresses cell proliferation38. In dogs, Wang et al. (2024)29 demonstrated that a 3′ UTR variant of MSRB3 (g.8394697 C > T) influences gene expression levels. Specifically, the ancestral C allele, frequent among wolves and breeds with smaller erect ears, corresponds to less MSRB3 expression than the derived T allele. Based on these findings, we posit that the derived long-ear allele enhances MSRB3 expression and promotes cell proliferation, ultimately contributing to larger ear size.

Our proposed mechanism is in direct contrast with a study in pigs, wherein larger ears are associated with reduced MSRB3 protein abundance, despite unchanged mRNA expression14. In an alternative scenario, the derived long-ear allele identified herein may disrupt a distal gene enhancer for other genes associated with ear size (e.g., HMGA2, LEMD3, WIF1)39,40. It is also plausible that the variant may be in high linkage disequilibrium with a causal variant that was not identified in this investigation.

Our study is the first to propose that CFA10 harbors two independent loci underlying the drop-ear phenotype. The derived ear carriage alleles each appear on an ancestral haplotype (1|0|0|0, 0|0|0|1), suggesting that they arose separately. As breeds having these haplotypes predominantly have prick ears, these loci do not appear to independently influence ear carriage. However, a recombinant haplotype containing both derived alleles is highly predictive of drop ears. Furthermore, a haplotype containing these alleles in conjunction with the derived ear length allele, is under selection in breeds with the longest drop ears. In contrast, breeds that retained the ancestral canid haplotype typically exhibit small, erect ears. These observations raise the possibility that each derived variant may independently increase ear size and that ear size itself plays a significant role in determining ear carriage, as larger ears are more prone to droop.

A limitation of our study is the use of breed standard ear lengths, which prohibited consideration of within breed variation. The use of morphometric data from a breed exhibiting variability in both ear length and haplotype composition (e.g., the Labrador Retriever) would increase our understanding of the additive effects of the derived alleles. This approach would minimize the impact of confounding morphological factors that vary across breeds and alter the position of the ear relative to the jawline, such as skull shape and ear set. It would also eliminate population substructure due to selection for breed-defining characteristics, such as coat color and type. Finally, future studies using long-read resequencing data would permit the identification of structural variants that may have been missed herein.

Although CFA10 is consistently the strongest signal in association studies for ear morphology, it is likely that additional loci also contribute. For instance, we observed that breeds having furnishings, caused by RSPO2, are predominantly drop-eared, despite having low numbers of derived alleles on CFA10 (e.g., Maltese, Black Russian Terrier). Likewise, the haplotype containing the small-body allele (1|0|1|0) contains only a single derived ear carriage allele, yet is found in both prick- and drop-eared breeds.

Materials and methods

We generated a whole-genome sequence joint variant call file, containing 3,023 dogs, wolves, and coyotes, including 1,971 samples released by the Dog10K consortium41. Sequence reads from these 3,023 individuals were mapped to the dog reference genome UU_Cfam_GSD_1.0, canFam424,41, concatenated with the Y chromosome from ROS_Cfam_1.0 (NCBI RefSeq GCF_014441545.1; available on NCBI SRA under PRJNA615959), and processed using the OnlyWAG and ManyWags bioinformatic pipelines, as previously described42. Variants were filtered for missingness, retaining only bi-allelic SNVs with call rates > 99%. A list of all individuals used in this study and their corresponding SRA IDs is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Population inclusion criteria

Breeds were categorized into prick or drop ear based on breed standard descriptions. For phenotypically drop-eared breeds, we used breed standard images to designate each breed to one of five categories of ear length: short (1), short-medium (2), medium (3), medium-long (4), and long (5) (Supplementary Table 1). We excluded breeds having ambiguous or intermediate (e.g., rose ears) ear types, as well as those that we could not confidently classify, primarily due to variation in ear length (e.g., Dachshund), high ear set (e.g., Australian shepherd), or because long hair obscured the ear (e.g., Afghan hound). Seventy-six breeds were classified: 9 short, 16 short-medium, 14 medium, 24 medium-long, and 13 long (Supplementary Table 1). For a binary GWAS, we defined short ears as those that do not reach the jawline (25 breeds), and long ears as those that extend past the jawline (37 breeds). We attempted to minimize population stratification due to other common breed-defining traits, by including breeds with similar body sizes, coat colors, and hair types in all ear length categories.

GWAS

We selected 4 individuals, 2 males and 2 females, to represent each breed, where possible. Included individuals had median genome coverage ≥ 18X. All variants underwent filtering to exclude those missing genotypes in more than 1% of all samples or having a minor allele frequency less than 5%. For the ear length GWAS, we conducted linkage disequilibrium (LD) pruning using PLINK1.943 with the following parameters: window size = 50, step size = 5, and r² threshold = 0.99. Each GWAS was performed using a univariate linear mixed model with the Wald test using genome-wide mixed model association algorithm (GEMMA)44. Genome-wide significance was determined using a Bonferroni correction. The genomic inflation factor (λ) was calculated in R for each association using the formula: median (qchisq (1–P, df = 1))/qchisq (0.5, df = 1), where P is a vector of the Wald test P-values from the respective GWAS. LD pairwise analysis was performed using PLINK1.943 to calculate r2 values which were plotted using a custom Python script in a LocusZoom-style format. Coordinates and gene track are reported based on the canFam4 chromosome 10 (NC_049231.1).

Variant analysis

Dog genomic positions were converted to the human genome assembly (hg38) using UCSC LiftOver45. Evolutionary and functional annotations were visualized using the UCSC Genome Browser. Specifically, we examined PhyloP scores across 241 placental mammals46, and the human ReMap 2022 regulatory annotation track47, which compiles transcription factor binding sites from publicly available ChIP-seq datasets. To further investigate potential regulatory interactions, we used the 3D Genome Browser48, to visualize Hi-C data.

Haplotypes

Four-locus haplotypes were determined using an inference approach. Individuals homozygous at all four loci were first identified, as they have two identical haplotypes. These haplotypes were used to establish a reference set of haplotypes present in the dataset. For heterozygous individuals, haplotypes were inferred by determining allele combinations consistent with the established reference set, and preference was given to haplotypes most frequent within a breed.

Di statistic

Weir and Cockerham FST values were calculated49 using VCFtools for an unfiltered dataset of 56,555,601 SNVs, comparing breeds having ears that hang above (n = 15) or below the jawline (n = 20) to 15 prick-eared breeds (n = 15). The data were then filtered to only include CFA10 and imported into R. The di statistic was calculated for all autosomal SNVs using a custom script50,51. To visualize selection across CFA10, we used locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) of the resulting di values with α = 0.02 to maximize resolution.

Data availability

All genomes used to carry out this work are available on SRA under BioProject IDs: PRJNA648123 (Dog10K), PRJNA937381, PRJNA687247, PRJEB16012, PRJNA448733, and PRJNA685036.

References

Ryding, S., Klaassen, M., Tattersall, G. J., Gardner, J. L. & Symonds, M. R. E. Shape-shifting: changing animal morphologies as a response to Climatic warming. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 1036–1048 (2021).

Hill, R. W. & Veghte, J. H. Jackrabbit ears: surface temperatures and vascular responses. Science 194, 436–438 (1976).

Stevenson, R. D. Allen’s rule in North American rabbits (Sylvilagus) and hares (Lepus) is an exception, not a rule. J. Mammal. 67, 312–316 (1986).

Shen, J. et al. Genome-wide association study reveals that the IBSP locus affects ear size in cattle. Heredity (Edinb). 130, 394–401 (2023).

Jawasreh, K., Boettcher, P. J. & Stella, A. Genome-wide association scan suggests basis for microtia in Awassi sheep. Anim. Genet. 47, 504–506 (2016).

Ren, J. et al. A missense mutation in PPARD causes a major QTL effect on ear size in pigs. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002043. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002043 (2011).

Gao, L., Xu, S. S., Yang, J. Q., Shen, M. & Li, M. H. Genome-wide association study reveals novel genes for the ear size in sheep (Ovis aries). Anim. Genet. 49, 345–348 (2018).

He, S. et al. Genome-wide association study shows that microtia in Altay sheep is caused by a 76 bp duplication of HMX1. Anim. Genet. 51, 132–136 (2020).

Klawatsch, J. et al. Genetic basis of ear length in sheep breeds sampled across the region from the middle East to the alps. Anim. Genet. 55, 123–133 (2024).

Koch, C. T., Bruggman, R., Tetens, J. & Drögemüller, C. A non-coding genomic duplication at the HMX1 locus is associated with crop ears in Highland cattle. PLoS One. 8, e77841. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077841 (2013).

Wei, C. et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals population structure and selection in Chinese Indigenous sheep breeds. BMC Genom. 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1384-9 (2015).

Kumar, C. et al. Population structure, genetic diversity and selection signatures within seven Indigenous Pakistani goat populations. Anim. Genet. 49, 592–604 (2018).

Paris, J. M., Letko, A., Hafliger, I. M., Ammann, P. & Drögemüller, D. Ear type in sheep is associated with the MSRB3 locus. Anim. Genet. 51, 968–972 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. Copy number variation in the MSRB3 gene enlarges Porcine ear size through a mechanism involving miR-584-5p. Genet. Sel. Evol. 50, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-018-0442-6 (2018).

Shen, X. et al. Down-regulation of msrb3 and destruction of normal auditory system development through hair cell apoptosis in zebrafish. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 59, 195–203 (2015).

Nayak, G. et al. MSRB3 antioxidant activity is necessary for inner ear cuticular plate structure and hair bundle integrity. Dis. Model. Mech. 18, dmm052194. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.052194 (2025).

Brown, E. A. et al. FGF4 retrogene on CFA12 is responsible for chondrodystrophy and intervertebral disc disease in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 11476–11481 (2017).

Plassais, J. et al. Whole genome sequencing of Canids reveals genomic regions under selection and variants influencing morphology. Nat. Commun. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09373-w (2019).

Belyaev, D. K. Destabilizing selection as a factor in domestication. J. Hered. 70, 301–308 (1979).

Boyko, A. R. et al. A simple genetic architecture underlies morphological variation in dogs. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000451. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000451 (2010).

Vaysse, A. et al. Identification of genomic regions associated with phenotypic variation between dog breeds using selection mapping. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002316 (2011).

Webster, M. T. et al. Linked genetic variants on chromosome 10 control ear morphology and body mass among dog breeds. BMC Genom. 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1702-2 (2015).

Rimbault, M. et al. Derived variants at six genes explain nearly half of size reduction in dog breeds. Genome Res. 23, 1985–1995 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. A novel canine reference genome resolves genomic architecture and uncovers transcript complexity. Commun. Biol. 4, 185. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-01698-x (2021).

Slavney, A. J. et al. Five genetic variants explain over 70% of hair coat pheomelanin intensity variation in purebred and mixed breed domestic dogs. PLoS One. 16, e0250579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250579 (2021).

Dixon, J. R. et al. Chromatin architecture reorganization during stem cell differentiation. Nature 518, 331–336 (2015).

Boyko, A. R. The domestic dog: man’s best friend in the genomic era. Genome Biol. 12, 216. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-216 (2011).

Housley, D. J. E. & Venta, P. J. The long and the short of it: evidence that FGF5 is a major determinant of canine hair-itability. Anim. Genet. 37, 309–315 (2006).

Wang, S. Z. et al. Historic dog furs unravel the origin and artificial selection of modern nordic Lapphund and elkhound dog breeds. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41, msaa108. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msae108 (2024).

Peng, Y. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the Arctic Fox (Vulpes lagopus) using PacBio sequencing and Hi-C technology. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 2093–2108 (2021).

Kliver, S. et al. A chromosome-phased diploid genome assembly of African hunting dog (Lycaon pictus). J. Hered. 116, 78–87 (2025).

Ballard, J. W. O. et al. The Australasian Dingo archetype: de Novo chromosome-length genome assembly, DNA methylome, and cranial morphology. Gigascience 12, giad018. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giad018 (2023).

Kim, H. Y. & Gladyshev, V. N. Methionine sulfoxide reduction in mammals: characterization of methionine-R-sulfoxide reductases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15, 1055–1064 (2004).

Zentner, G. E., Tesar, P. J. & Scacheri, P. C. Epigenetic signatures distinguish multiple classes of enhancers with distinct cellular functions. Genome Res. 21, 1273–1283 (2011).

Uyehara, C. M. & Apostolou, E. 3D enhancer–promoter interactions and multi-connected hubs: organizational principles and functional roles. Cell. Rep. 42, 112068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112068 (2023).

Lim, D. H., Han, J. Y., Kim, J. R., Lee, Y. S. & Kim, H. Y. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B in the Endoplasmic reticulum is critical for stress resistance and aging in drosophila. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 20–26 (2012).

Hibar, D. P. et al. Novel genetic loci associated with hippocampal volume. Nat. Commun. 8, 13624. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13624 (2017).

Lee, E., Kwak, G. H., Kamble, K. & Kim, H. Y. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B3 deficiency inhibits cell growth through the activation of p53-p21 and p27 pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 547, 1–5 (2014).

Li, P. et al. Fine mapping of a QTL for ear size on Porcine chromosome 5 and identification of high mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2) as a positional candidate gene. Genet. Sel. Evol. 44, 6 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Genome-wide scan reveals LEMD3 and WIF1 on SSC5 as the candidates for Porcine ear size. PLoS One. 9, e102085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102085 (2014).

Meadows, J. R. S. et al. Genome sequencing of 2000 Canids by the Dog10K consortium advances the Understanding of demography, genome function and architecture. Genome Biol. 24, 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-023-03023-7 (2023).

Cullen, J. N. & Friedenberg, S. G. Whole animal genome sequencing: user-friendly, rapid, containerized pipelines for processing, variant discovery, and annotation of short-read whole genome sequencing data. G3 (Bethesda). 13 (jkad117). https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkad117 (2023).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7 (2015).

Zhou, X. & Stephens, M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 44, 821–824 (2012).

Hinrichs, A. S. et al. The UCSC genome browser database: update 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D590–D598. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkj144 (2006).

Zoonomia Consortium. A comparative genomics multitool for scientific discovery and conservation. Nature 587, 240–245 (2020).

Hammal, F. et al. ReMap 2022: a database of human, mouse, drosophila and Arabidopsis regulatory regions from an integrative analysis of DNA-binding sequencing experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D316–D325. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab996 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. The 3D genome browser: a web-based browser for visualizing 3D genome organization and long-range chromatin interactions. Genome Biol. 19, 151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1519-9 (2018).

Weir, B. S. & Cockerham, C. C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38, 1358–1370 (1984).

Akey, J. M. et al. Tracking footprints of artificial selection in the dog genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 1160–1165 (2010).

Friedenberg, S. G., Meurs, K. M. & Mackay, T. F. Evaluation of artificial selection in standard poodles using whole-genome sequencing. Mamm. Genome. 27, 599–609 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Ryleigh Preuitt for illustrating the dogs in Figs. 1 and 2, and 4 and Dr. Jacquelyn Evans for critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.E.R., A.R.R., and L.A.C. conceived the study. J.N.C. and S.G.F. curated the data. T.E.R. and L.A.C. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rudolph, T.E., Ramey, A.R., Cullen, J.N. et al. Identification of genetic variants associated with ear length in drop-eared dogs. Sci Rep 16, 3105 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33036-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33036-0