Abstract

Seismic fault identification remains critical for resource exploration and geohazard prevention, yet conventional methods suffer from subjective interpretation bias and computational inefficiency. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) enhance automation, their neglect of multiscale frequency features limits accuracy. Here, propose a novel Wavelet-Convolutional Neural Network (W-CNN) and its variants (W-CNN R1, W-CNN R2 and W-CNN R3) that architecturally fuses discrete wavelet transforms (DWT) with CNNs, establishing a spatial-frequency learning paradigm. By embedding Haar wavelet filter banks with cross-scale residual connections, W-CNN achieves explicit decoupling of high-frequency fault details from low-frequency structural contexts, reducing parameters by 21% versus conventional CNNs. Evaluated on coal mine datasets, W-CNN R3 achieves 90.0% accuracy (F1-score 90.3%), surpassing mainstream CNNs (LeNet-5, AlexNet, VGG16) by 0.6–12.3%, with the highest recall (95.5%) and faster convergence. The model successfully resolves 30 out of 32 exposed complex micro-faults (93.8% detection rate), demonstrating strong consistency with roadway-exposed faults in geologically complex zones, which significantly enhances its predictive capability for small-scale discontinuities. The frequency selection mechanism effectively suppresses noise interference, while the optimized architecture enables orders-of-magnitude acceleration in 3D processing. This framework provides an extensible solution for intelligent geological interpretation, with critical applications in mine safety monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurately characterizing subsurface fault systems constitutes a critical geological imperative for ensuring coal mine safety and optimizing shale gas recovery1. Although 3D seismic exploration enables high-resolution fault detection2, manual interpretation remains limited by the inherent ambiguity in fault-strata contact relationships within complex structural zones3, and by the unreliable detection, using conventional seismic attributes, of micro-faults (< 5 m throw) exposed in underground roadways4. Traditional machine learning approaches—including support vector machines5,6 and random forests7,8—have enhanced automation but remain constrained by feature engineering dependencies that compromise generalization in heterogeneous reservoirs9,10.

CNNs have introduced a new paradigm for automated fault detection through end-to-end seismic feature learning3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Architectures like U-Net and ResNet leverage encoder-decoder structures to effectively capture fault spatial characteristics19,20. However, these models predominantly focus on spatial dimensions (depth, width, channels) while neglecting the critical frequency-domain information: spectral aliasing between low-frequency stratigraphic reflections and high-frequency fault edges fundamentally limits micro-fault detection accuracy21,22,23,24,25,26,27. This deficiency becomes particularly pronounced in complex coal-bearing formations where spectral competition between low-frequency anomalies (e.g., water-rich zones) and high-frequency rupture signatures drastically reduces model specificity28,29,30.

Orthogonal transformations simplify data complexity by converting correlated variables into uncorrelated principal components and improve convergence in adaptive signal processing31. For example, fast Fourier transform (FFT) has been applied to machine learning for shark behaivor classification7, while discrete wavelet transform (DWT) detects high impedance faults27. Wavelet transform’s time-frequency localization properties offer a theoretical breakthrough32,33,34,35,36.Unlike Fourier transform, DWT enables multi-resolution analysis through adjustable basis functions37,38,39, where high-frequency coefficients enhance edge singularity responses while low-frequency components preserve macrostructural continuity40,41,42,43.Current implementations, however, predominantly utilize DWT as preprocessing subtools rather than deep integration with CNN feature extraction15,44,45,46. Inspired by Fujieda et al.‘s wavelet CNNs for texture analysis47 and Yeh et al. ‘s CNN architecture with skip connections48, we propose architecturally embedding DWT modules into CNN feedforward paths to establish spatial-frequency fusion—suppressing stratigraphic noise while enhancing cross-scale fault representation.

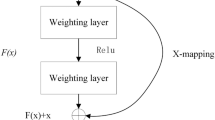

Herein, we present a novel Wavelet-Convolutional Neural Network(W-CNN, Fig. 1a)and its variants (W-CNN R1, W-CNN R2 and W-CNN R3, Fig. 1b) that achieves architectural tight-coupling between DWT and deep learning. Through hybrid wavelet layers (Haar-based filter banks) and cross-scale residual connections, W-CNN explicitly decouples low-frequency structural constraints from high-frequency fault responses in feature space while enhancing physical interpretability. Comparative experiments with coal mine data demonstrate W-CNN’s superior predictive performance over mainstream CNNs with fewer training epochs. Our frequency-space co-interpretation framework establishes a new methodology for intelligent mining in complex coal measures.

Result

Overview

Seismic data were converted to grayscale (single-channel input). Using Haar wavelets, we integrated 2D-DWT outputs into CNNs, creating a multiresolution-inspired architecture (Fig. 1). Benchmarking commenced with synthetic data, followed by real 3D seismic validation.

The architecture of the W-CNN for seismic fault prediction. The Haar wavelet transform’s low pass (LP) and high pass (HP) filters are incorporated as \(\:{k}_{l,t}\) and \(\:{k}_{h,t}\), respectively. (a) Base W-CNN. (b) Enhanced variants: black structures denote W-CNN R1; red-dashed skip connections added for R2; orange-dashed connections added for R3.

Wavelet-guided multiscale feature decoupling

In this network (Fig. 1), Haar wavelets were selected for their balance of architectural compatibility and engineering practicality. Compared with alternative wavelets such as Daubechies and Symlets, Haar wavelet filter coefficients only include ± 1 and 0, eliminating the need for complex floating-point operations. This allows seamless embedding into CNN convolutional layers as learnable parameters, adapting to the demand for fast processing of 3D seismic data. Additionally, the step characteristics of Haar wavelets are highly matched with the “spatial discontinuity” signals of faults, enabling effective extraction of micro-fault edge features. Previous studies have also validated the effectiveness of Haar wavelets in seismic structural interpretation33. All convolutions used 3 × 3 kernels with 1 × 1 padding, preserving spatial dimensions. Stride-2 convolutions replaced max-pooling, to maintain multiresolution integrity. Dense connections49 and skip connections50,51 are employed to maximizes the utilization of information from multiresolution analysis. Dense connections allow each layer’s image to be directly connected to all subsequent layers, promoting efficient information flow52. Skip connections help maintain general features with 1 × 1 convolution kernels and activation functions, increasing the network’s input dimensions. It connects data of the same size but at different levels, preventing the loss of original features caused by increasing the number of convolution layers. This ensures that feature maps of different sizes are connected without causing vanishing or exploding gradients. Global average pooling is used to improve model robustness and prevent overfitting53, and batch normalization is applied between convolution and activation layers to further stabilize the network structure. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function is used throughout the network.

In W-CNN, 2D-DWT decomposes images (Fig. 2) where: low-frequency components preserve structural features, while high-frequency components retain finer details (including noise). Faults induce spatial discontinuities—particularly subtle dislocations imperceptible visually—which are optimally captured by wavelet high-pass filtering. Higher-level approximations become increasingly abstract, losing fault-relevant information.

Synthetic validation drives spectral-spatial feature refinement

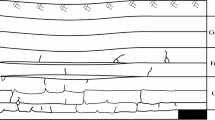

The synthetic seismic dataset was generated by integrating geological constraints derived from exposed mine roadway profiles, encompassing coal seam thickness variations and structural undulations (Fig. 3). This synthesis incorporated calibrated subsurface velocity models (based on well-log data from the study area) and key petrophysical properties of the coal-bearing formations (e.g., density and impedance contrasts between coal seams and surrounding rocks), ensuring geological authenticity and consistency with actual seismic acquisition scenarios. While these datasets did not encompass the full complexity of stratigraphic sequences, the deliberate introduction of realistic geological features significantly enhanced their physical fidelity compared to idealized models.

The synthetic profiles (Fig. 3) were partitioned into 32 × 32 pixel windows using the sliding-window method described in Eq. (10). This yielded an initial dataset containing 288,450 training samples and 166,850 test samples. Crucially, the unprocessed training data exhibited severe class imbalance between fault and non-fault samples. To address this, we implemented random down-sampling to reduce non-fault samples, resulting in a balanced training set of 3,476 samples (Table 1). Conversely, the test dataset remained unmodified to preserve real-world evaluation conditions, retaining all 266,850 samples for comprehensive assessment.

Using the base W-CNN architecture (Fig. 1a) to predict faults in the synthetic test dataset (Fig. 3b), we visualized the results through continuous fault probability maps where color gradient intensity (yellow = high probability) indicates predicted fault likelihood (Fig. 4). The predicted demonstrated strong spatial alignment with ground-truth fault locations embedded in the synthetic model, successfully validating the core feasibility of W-CNN for seismic fault prediction.

However, quantitative analysis revealed a key limitation: insufficient integration of low-frequency information in the base architecture caused reduced prediction smoothness, manifesting as locally fragmented probability distributions near fault boundaries (Fig. 4b). This observation motivated the development of enhanced variants—W-CNN R1, R2, and R3 (Fig. 1b)—which explicitly address spectral completeness through modified connectivity schemes. Notably, we consciously exclude higher-level low-frequency components during wavelet decomposition since progressively increased abstraction and diminished information richness in these layers provide diminishing returns for fault detection. This deliberate omission reduces computational complexity while maintaining detection efficacy. Subsequent validation on actual seismic data confirmed the efficacy of these architectural improvements.

Geological complexity validates architectural superiority

While synthetic data established methodological feasibility, real-world performance requires evaluation under the complex geological conditions inherent in field seismic data. For this purpose, we utilized 3D seismic data from a coal mine in northern China—a region characterized by structurally complex formations, steeply inclined strata, and significant faulting with variable coal seam thickness. The dataset, extracted from a densely drilled area, comprised dimensions of 185 (inline) × 145 (crossline) × 256 (time samples). Geological experts manually labeled 50 inline and 38 crossline profiles based on integrated borehole and roadway exposure data, from which we selected 83 representative profiles to construct the actual seismic dataset (Table 2).

In rigorous benchmarking against three seminal CNN architectures—LeNet-5 representing early shallow networks54, AlexNet exemplifying intermediate depth55, and VGG16 as a deep learning baseline56—W-CNN variants demonstrated transformative performance. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, W-CNN R3 achieved peak F1-score of 90.3%, outperforming LeNet-5 (78.0%), AlexNet (88.8%) and VGG16 (89.7%) by 0.6–12.3% points. Industry-leading recall (95.5%) was attained by R3—11.9% higher than VGG16 (87.3%)—demonstrating unprecedented sensitivity to micro-faults (< 5 m) Despite VGG16 maintained a narrow precision advantage (92.36% vs. R3’s 85.7%), its spectral limitations result in significantly lower recall (87.26%) confirming W-CNN’s superior balance in the precision-recall tradeoff.

Trough architectural performance progression revealed by study (Table 3), base W-CNN’s underperformance (Accuracy: 85.6% vs. R3’s 90.0%) directly resulted from insufficient low-frequency information integration, while R2’s red-dashed skip connections optimally balanced F1-score (89.8% vs. VGG16’s 89.7%) with superior recall (92.19% vs. 87.26%). Notably, W-CNN R3 achieves an industry-leading recall of 95.5%, which directly stems from the directional retention and enhancement of high-frequency features. Haar wavelet high-pass filters () effectively amplify edge discontinuity signals induced by micro-faults—these signals are dominated by high-frequency components in seismic data, which are easily masked by low-frequency stratigraphic reflection noise. The cross-scale residual connections (orange-dashed pathways in Fig. 1b) ensure that high-frequency features are not lost in deep network layers, avoiding the attenuation of micro-fault information caused by pooling operations in traditional CNNs. This design enhances the model’s response sensitivity to small-scale discontinuities, significantly reducing the false negative rate.

The red/orange-dashed skip connections in W-CNN variants (Fig. 1b) differ fundamentally from classical ResNet blocks. Both alleviate the vanishing gradient problem through direct feature transmission, but ResNet focuses on identity mapping of same-scale features, while W-CNN’s skip connections realize cross-scale fusion of high-frequency and low-frequency features. This design not only solves the gradient problem but also achieves multi-scale feature reuse, allowing the model to retain macro-stratigraphic structures while not missing micro-fault high-frequency details—an innovation not involved in classical ResNet, which enhances the scenario pertinence of the architecture.

We also compared the network layers, training parameters, and convergence speeds of the models. W-CNN converges faster than other networks despite having more layers, thanks to its efficient parameter optimization (Table 4). While VGG16 achieves similar accuracy to W-CNN, it has fewer layers and converges more slowly, highlighting W-CNN’s balance between fast convergence and high accuracy. Critically, W-CNN achieves these results with architectural efficiency.

Fault distribution prediction was performed using the full 3D seismic volume, with five expert-annotated seismic profiles extracted from the dataset and visualized (Fig. 6a). While all models demonstrate competent predictive capabilities—validated through roadway fault exposures—their architectural designs dictate fundamental performance boundaries.

Due to space constraints, prediction results from underperforming models (LeNet-5 and AlexNet) are not visualized, as both exhibit fundamental limitations including excessive false positive rates and discontinuous fault predictions. In contrast, VGG16 (Fig. 6b) and W-CNN variants (Fig. 6c-f) achieve superior geological plausibility through deep hierarchical feature learning. The base W-CNN architecture (Fig. 6c), while demonstrating exceptional edge sensitivity through high-frequency retention, suffers from insufficient precision (Accuracy: 85.6%) due to its exclusion of low-frequency information—this architectural limitation results in spatially fragmented predictions despite rapid convergence (9 epochs).

The R1 variant (Fig. 6d) addresses this deficiency through low-frequency integration, yielding measurable accuracy gains (+ 1.5%) at the cost of extended convergence (13 epochs). While still trailing VGG16 in overall performance, this modification establishes the critical foundation for spectral balance. The enhanced R2 and R3 architectures (Fig. 6e-f) with skip connections ultimately bridge this performance gap, achieving comparable accuracy to VGG16 (89.8% vs. 89.7% F1-score) while demonstrating superior boundary continuity—particularly evident in R3’s prediction continuity that exceeds VGG16’s capabilities. This progression validates W-CNN’s core operational value: providing engineers with configurable architecture pathways to prioritize either fault detection sensitivity (R3: recall 95.5%) or prediction stability (R2: precision 89.4%) based on specific mine safety requirements.

Comparative performance evaluation of VGG16 and W-CNN in fault prediction tasks on representative seismic profiles. Expert-annotated faults are delineated by red lines, with color intensity in prediction maps (yellow gradient) denoting fault probability. a Expert-interpreted seismic profiles. b VGG16 predictions. c W-CNN predictions. d W-CNN R1 predictions. e W-CNN R2 predictions. f W-CNN R3 predictions.

Roadway-exposed validation of micro-fault detection

Field validation against 32 exposed faults in Coal Seam No.4 conclusively demonstrates W-CNN R3’s operational efficacy (Fig. 7), achieving a 93.8% detection rate (30/32 faults). The model successfully resolved complex structural linkages—including the F4-F5 and F14-F17-F25 fault systems. Remarkably, it resolves micro-faults (< 5 m), overcoming fundamental resolution barriers in conventional seismic methods. Residual challenges persist in high-density clustered fault zones (specifically the F6-F10 and F20-F24 groups), where azimuthal discrepancies between predicted and observed fault strikes indicate limitations in resolving intersecting micro-fault networks under intense strain partitioning.

Cross-validation of W-CNN R3 fault predictions against in-situ roadway exposures in Coal Seam No.4. Documented faults (n = 32) show 93.8% detection consistency with W-CNN predictions (30/32 matched events), where red lines denote field-validated faults and yellow probability maps indicate model outputs.

Discussion

This study develops a novel W-CNN and its variants (W-CNN R1, W-CNN R2 and W-CNN R3) that synergistically combines DWT with deep learning architectures. Validated on 3D seismic data from structurally complex coal measures, the framework delivers three transformative advancements: (1) Architectural integration of Haar wavelet filter banks with residual pathways enables explicit decoupling of high-frequency fault signatures from low-frequency structural contexts. This suppresses stratigraphic noise while detecting micro-faults (< 5 m), achieving 93.8% field validation accuracy (30/32 exposed faults detected). (2) Despite operating at 2.6× greater depth than VGG16 (60 vs. 23 layers), W-CNN R3 maintains near-parameter parity (22.1 M vs. 20.4 M, + 8.3% increase) with 30% faster convergence (14 vs. 19 epochs). (3) W-CNN R3 achieves 90.3% F1-score and 95.5% recall—outperforming LeNet-5 (F1:78.0%), AlexNet (F1:88.8%), and VGG16 (F1:89.7%) by up to 12.3% points. Crucially, it resolves fault linkages (e.g., F4-F5 continuity) that are undetectable using conventional seismic attributes, while achieving a 93.8% field-validated detection rate (Fig. 7). This capability substantially enhances operational safety guidance for coal mining.

The azimuthal deviations (approximately 15°) in clustered fault zones (e.g., F20–F24 group) mainly result from two core factors: first, the signal superposition interference in high-density clustered fault zones—multiple micro-faults intersect and overlap spatially, leading to the coupling of multi-azimuth edge features and spectral aliasing, which makes it difficult for the model to distinguish the true strike of a single fault; second, the isotropic limitation of Haar wavelet filters—current filters respond consistently to edge features in different directions (horizontal, vertical, diagonal), lacking directional enhancement capabilities for the dominant signals of clustered faults. Future work will address these limitations by introducing direction-sensitive wavelet bases (e.g., Gabor wavelets) and adding an azimuthal attention mechanism to the residual connections, enabling the model to automatically identify and enhance the dominant azimuthal signals of clustered faults while suppressing interference from secondary signals. However, this work establishes W-CNN as a new paradigm for intelligent seismic interpretation, with immediate applications in mine hazard prevention and subsurface resource exploration.

Method

Theoretical synthesis of wavelet decomposition and CNN frameworks

The W-CNN integrates CNNs’ spatial feature extraction with spectral analysis’ scale-invariant capabilities, specifically W-CNN focuses on the high-pass filter output component than the low-pass filter output component in fault detection applications. This is because the high frequency component of faults in seismic data is more significant than the low frequency component. Though the physical interpretation of CNNs remains under investigation, mathematically they constitute a finite form of multi-resolution analysis, providing a foundation for wavelet transforms integration.

CNNs typically consist of convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers, with the convolutional and pooling layers serving as the core components. The convolutional layer extracts feature from the input data, while the pooling layer selects key features, reduces dimensionality, and decreases the computational load on the neural network. Let \(\:X\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{H\times\:W}\) represent a 2D tensor matrix, which serves as the input for the convolution operation. The element \(\:x(i,j)\)denotes the value at the \(\:i\)-th row and \(\:j\)-th column of the matrix, where \(\:0\le\:i<H\) and \(\:0\le\:j<W\). After the convolution operation, the output matrix \(\:Y\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{H\times\:W}\) is calculated as follows:

where \(\:{\upomega\:}(k,l)\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{H}_{i}\times\:{W}_{j}}\) represents the convolution weights. For simplicity in subsequent derivations, we can write this as:

where \(\:W=\omega\:(k,l)\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{H}_{i}\times\:{W}_{j}}\:\) and “\(\:\text{*}\)” denotes the 2D convolution operation.

The pooling layer performs a “down-sampling” operation, which mimics the human visual system’s abstraction and dimensionality reduction of visual inputs. It typically involves either average pooling or max pooling. For an input matrix \(\:X\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{H\times\:W}\), the output matrix \(\:Y\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{\frac{H\times\:W}{p}}\) is computed. The average pooling operation is expressed as:

and max pooling is:

where \(\:p\) defines the pooling support, and \(\:m=\frac{H}{p}\), \(\:n=\frac{W}{p}\). To simplify derivations, we primarily focus on average pooling, as max pooling follows a similar principle. The pooling can be written as

where \(\:P\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{p\times\:p}\) is defined as:

Average pooling thus involves performing a convolution with \(\:P\), followed by down-sampling with a stride of \(\:p\). By combining Eqs. (2) and (5), the generalized formula for convolution and pooling can be written as:

where the generalized weight \(\:R\) is defined as:

-

\(\:R=W\) for \(\:p=1\) (convolution in Eq. (2)),

-

\(\:R=P\) for \(\:p>1\) (pooling in Eq. (5)),

-

\(\:R=W*P\) for \(\:p>1\) (convolution followed by pooling).

The DWT decomposes a signal into multiple levels, each characterized by distinct time and frequency resolutions. Using an octave-based resolution, the signal is separated into approximation and detail components through low-pass (LP) and high-pass (HP) filters, respectively. This decomposition results in multiple frequency bands. For a signal \(\:s\) of length \(\:N\), two sets of coefficients are computed: approximation coefficients \(\:{c}_{A}\) and detail coefficients \(\:{c}_{D}\). The multi-resolution analysis is expressed as:

where \(\:{k}_{l}\) and \(\:{k}_{h}\) are the LP and HP filters, respectively, each with a length of \(\:2n\). The lengths of \(\:{c}_{A}\) and \(\:{c}_{D}\) are given by \(\:floor\left(\frac{N-1}{2}\right)+n\). The number of applications \(\:t\) defines the level of the multi-resolution analysis.

By comparing Eq. (7) with Eqs. (8) and (9), it is evident that when \(\:p=2\), the output is halved by taking a pairwise average. Therefore, CNNs can be seen as a limited form of multi-resolution analysis, where they entirely discard the detail coefficients \(\:{c}_{D}\) and rely solely on the approximation coefficients.

Equation (7) describes the generalized form of CNN pooling, which essentially extracts key features through scale reduction—this is consistent with the core idea of wavelet multi-resolution analysis, i.e., realizing multi-scale decomposition and reconstruction of signals through high-pass and low-pass filtering57. Mallat’s fast wavelet decomposition and reconstruction algorithm proved that multi-resolution analysis essentially gradually strips redundant information and retains core features, while CNN pooling is a simplified implementation of this idea in deep learning. Unlike traditional CNNs, which primarily focus on low-frequency information (i.e., signal approximations) and automatically ignore high-frequency components, integrating wavelet transforms into the CNN structure reconstructs the complete multi-resolution framework. In wavelet transforms, \(\:{k}_{l}\) corresponds to the scaling function, and \(\:{k}_{h}\) corresponds to the wavelet function. In contrast, CNN weights \(\:\omega\:\) are unconstrained and are learned from data during training. This key difference in W-CNNs allows for the inclusion of frequency information in the network’s computations. Multi-scale feature active fusion is achieved through residual connections. The constraints imposed by the wavelet transforms reduce the number of parameters, maintaining high recognition accuracy while improving computational efficiency.

Seismic-adaptive CNN training via sliding-window augmentation

Deep learning datasets typically consist of three parts: training set, the validation set, and the test sets. The training set is used to learn model parameters, the validation set helps fine-tune those parameters, and the test set evaluates the model’s final performance. In this study, two types of datasets were used: a synthetic seismic fault dataset to validate the feasibility of the W-CNN method, and the actual seismic dataset from a coal mine in northern China. The fault labels in the seismic data were manually assigned by experts based on mining and drilling data (Interpretation Group, National Key Laboratory of Coal Fine Exploration and Intelligent Development).

In seismic fault prediction, many researchers treat the task as an image classification problem. However, compared to typical image classification, seismic fault classification is more complex due to the presence of multiple faults in a full seismic profile, making it difficult to directly locate fault positions11. To address this challenge, we implemented a sliding window method (Fig. 8) to partition seismic profiles into fixed-size (32 × 32 pixel) samples for automated fault classification. For a profile of size \(\:D\times\:W\), sample count \(\:N\) is:

where window size \(\:m=32\) and stride \(\:s=1\).

Typical CNNs consist of convolutional, activation, and pooling layers. The convolutional layer applies a filter to the input, producing feature maps passed to the next layer. The activation layer introduces non-linearity, while the pooling layer reduces dimensionality via down-sampling, merging features and lowering computational complexity. Learnable filters are initialized randomly and updated through backpropagation, optimizing the model by minimizing the loss function, which measures the difference between predicted and actual values.

To speed up computation and avoid memory overload from large datasets, the training data is divided into mini-batches of 256 samples. In each iteration, the data is randomly shuffled to ensure a more generalized training process. The model undergoes multiple epochs, each representing one full pass through the data. To mitigate overfitting, we employed early stopping, halting training if performance on a validation set did not improve within a predefined limit.

Model were trained with Adam optimizer (initial LR = 0.0001, fixed during training), mini-batches of 256 samples, and early stopping based on validation loss-training halted if validation loss did not improve for 5 epochs. Class imbalance was mitigated via random down-sampling.

Quantitative metrics for field-ready model validation

To evaluate model performance, we used a confusion matrix, which compares the predicted results with expert interpretations (Table 5). True positives (TP) are when both the model and expert agree that a fault exists, true negatives (TN) are when both agree there is no fault, false positives (FP) are when the model predicts a fault but the expert disagrees, and false negatives (FN) are when the expert identifies a fault but the model does not. The metrics calculated from the confusion matrix include accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, which balances precision and recall. The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

Data availability

The actual seismic data in the paper can not be shared due to commercial confidentiality. However, the synthetic seismic data in the study are available via [DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14673284]. The relevant codes and models involved in the research can be obtained through [DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14673435].

References

Wu, X., Liang, L., Shi, Y. & Fomel, S. FaultSeg3D: using synthetic data sets to train an end-to-end convolutional neural network for 3D seismic fault segmentation. GEOPHYSICS 84, IM35–IM45 (2019).

Suping Peng. Current status and prospects of research on geological assurance system for coal mine safe and high efficient mining. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 2331–2345 (2020).

Mousavi, S. M. & Beroza, G. C. Deep-learning seismology. Science 377, eabm4470 (2022).

Lin, P., Peng, S., Zhao, J., Cui, X. & Du, W. Accurate diffraction imaging for detecting small-scale geologic discontinuities. GEOPHYSICS 83, S447–S457 (2018).

Zou, G., Ren, K., Sun, Z., Peng, S. & Tang, Y. Fault interpretation using a support vector machine: A study based on 3D seismic mapping of the Zhaozhuang coal mine in the Qinshui Basin, China. J. Appl. Geophys. 171, 103870 (2019).

Ren, K. et al. Fault identification based on the KPCA-GPSO-SVM algorithm for seismic attributes in the Sihe Coal Mine, Qinshui Basin, China. Interpretation 1–58 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1190/int-2022-0039.1

Yang, Y. et al. Feature Extraction, Selection, and K-Nearest neighbors algorithm for shark behavior classification based on imbalanced dataset. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 6429–6439 (2021).

Ren, K. et al. Fault identification and reliability evaluation using an SVM model based on 3-D seismic data volume. Geophys. J. Int. 234, 755–768 (2023).

Zuo, R. & Carranza, E. J. M. Support vector machine: A tool for mapping mineral prospectivity. Comput. Geosci. 37, 1967–1975 (2011).

Han, C. et al. Intelligent fault prediction with wavelet-SVM fusion in coal mine. Comput. Geosci. 194, 105744 (2025).

Xiong, W. et al. Seismic fault detection with convolutional neural network. GEOPHYSICS 83, O97–O103 (2018).

Pochet, A., Diniz, P. H. B., Lopes, H. & Gattass, M. Seismic fault detection using convolutional neural networks trained on synthetic poststacked amplitude maps. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16, 352–356 (2019).

Di, H., Li, Z., Maniar, H. & Abubakar, A. Seismic stratigraphy interpretation by deep convolutional neural networks: A semisupervised workflow. GEOPHYSICS 85, WA77–WA86 (2020).

Geng, Z. & Wang, Y. Automated design of a convolutional neural network with multi-scale filters for cost-efficient seismic data classification. Nat. Commun. 11, 3311 (2020).

Zhang, G., Lin, C. & Chen, Y. Convolutional neural networks for microseismic waveform classification and arrival picking. GEOPHYSICS 85, WA227–WA240 (2020).

Yu, S. & Ma, J. Deep learning for geophysics: current and future trends. Rev. Geophys. 59, e2021RG000742 (2021).

Zou, G., Liu, H., Ren, K., Deng, B. & Xue, J. Automatic recognition of faults in mining areas based on convolutional neural network. Energies 15, 3758 (2022).

Deng, B. et al. An approach of 2D convolutional neural network–based seismic data fault interpretation with linear annotation and pixel thinking. Geophys. Prospect. 72, 3350–3370 (2024).

An, Y. et al. Current state and future directions for deep learning based automatic seismic fault interpretation: A systematic review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 243, 104509 (2023).

An, Y. et al. Deep convolutional neural network for automatic fault recognition from 3D seismic datasets. Comput. Geosci. 153, 104776 (2021).

Kay, S. M. & Marple, S. L. Spectrum analysis—A modern perspective. Proc. IEEE 69, 1380–1419 (1981).

Hubral, P., Tygel, M. & Schleicher, J. Seismic image waves. Geophys. J. Int. 125, 431–442 (1996).

Cao, S. & Chen, X. The second-generation wavelet transform and its application in denoising of seismic data. Appl. Geophys. 2, 70–74 (2005).

Neut, J. V. D., Sen, M. K. & Wapenaar, K. Seismic reflection coefficients of faults at low frequencies: a model study. Geophys. Prospect. 56, 287–292 (2008).

Liu, W., Wang, Z. & Cao, S. Stratigraphic interfaces identification based on wavelet transform. SEG Tech. Program. Expanded Abstracts. 2012, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1190/segam2012-0247.1 (2012). Society of Exploration Geophysicists.

Botter, C., Cardozo, N., Qu, D., Tveranger, J. & Kolyukhin, D. Seismic characterization of fault facies models. Interpretation 5, SP9–SP26 (2017).

Yeh, H. G., Sim, S. & Bravo, R. J. Wavelet and denoising techniques for Real-Time HIF detection in 12-kV distribution circuits. IEEE Syst. J. 13, 4365–4373 (2019).

Li, X., Chen, S., Wang, E. & Li, Z. Rockburst mechanism in coal rock with structural surface and the microseismic (MS) and electromagnetic radiation (EMR) response. Eng. Fail. Anal. 124, 105396 (2021).

Li, X., Chen, S., Liu, S. & Li, Z. AE waveform characteristics of rock mass under uniaxial loading based on Hilbert-Huang transform. J. Cent. South. Univ. 28, 1843–1856 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Rock burst monitoring by integrated microseismic and electromagnetic radiation methods. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 49, 4393–4406 (2016).

Sang, E. F. & Yeh, H. G. The use of transform domain LMS algorithm to adaptive equalization. in Proceedings of IECON ’93–19th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics –2064 vol.3 2061. https://doi.org/10.1109/IECON.1993.339393 (1993).

Daubechies, I. Orthonormal bases of compactly supported wavelets. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 41, 909–996 (1988).

Larsonneur, J. L. & Morlet, J. Wavelets and seismic interpretation. In Wavelets (eds Combes, J. M. et al.) 126–131 (Springer, 1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-75988-8_7.

Chakraborty, A. & Okaya, D. Frequency-time decomposition of seismic data using wavelet-based methods. GEOPHYSICS 60, 1906–1916 (1995).

Graps, A. An introduction to wavelets. IEEE Comput. Sci. Eng. 2, 50–61 (1995).

Torrence, C. & Compo, G. P. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79, 61–78 (1998).

Singh, G. K. & Sa’ad Ahmed, S. A. K. Vibration signal analysis using wavelet transform for isolation and identification of electrical faults in induction machine. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 68, 119–136 (2004).

Osowski, S. & Garanty, K. Forecasting of the daily meteorological pollution using wavelets and support vector machine. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 20, 745–755 (2007).

Gumus, E., Kilic, N., Sertbas, A. & Ucan, O. N. Evaluation of face recognition techniques using PCA, wavelets and SVM. Expert Syst. Appl. 37, 6404–6408 (2010).

Liu, W., Cao, S. & Chen, Y. Seismic Time–Frequency analysis via empirical wavelet transform. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 13, 28–32 (2016).

Wang, Z., Zhang, B., Gao, J., Wang, Q. & Liu, Q. H. Wavelet transform with generalized beta wavelets for seismic time-frequency analysis. Geophysics 82, O47–O56 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Experimental study of effect of liquid nitrogen cold soaking on coal pore structure and fractal characteristics. Energy 275, 127470 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Experimental study on compressive behavior and failure characteristics of imitation steel fiber concrete under uniaxial load. Constr. Build. Mater. 399, 132599 (2023).

Liu, N. et al. Seismic data reconstruction via Wavelet-Based residual deep learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–13 (2022).

Shen, S., Li, H., Chen, W., Wang, X. & Huang, B. Seismic fault interpretation using 3-D scattering wavelet transform CNN. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5 (2022).

Jiang, J., Stankovic, V., Stankovic, L., Parastatidis, E. & Pytharouli, S. Microseismic event classification with Time-, Frequency-, and Wavelet-Domain convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–14 (2023).

Fujieda, S., Takayama, K. & Hachisuka, T. Wavelet Convolutional Neural Networks. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1805.08620 (2018).

Yeh, H. G., Corona, A. & Ramirez, T. Data-Driven Adaptive Modulation Classification Systems. in IEEE International systems Conference (SysCon) 1–7 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1109/SysCon64521.2025.11014808 (2025).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., van der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 4700–4708 (2017).

Springenberg, J. T., Dosovitskiy, A., Brox, T. & Riedmiller, M. Striving for Simplicity: The All Convolutional Net. Preprint at (2015). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.6806

Zhang, L. et al. Signal modulation classification based on deep learning and Software-Defined radio. IEEE Commun. Lett. 25, 2988–2992 (2021).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Pleiss, G., van der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Convolutional networks with dense connectivity. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 8704–8716 (2022).

Hsiao, T. Y., Chang, Y. C., Chou, H. H. & Chiu, C. T. Filter-based deep-compression with global average pooling for convolutional networks. J. Syst. Archit. 95, 9–18 (2019).

Lecun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE. 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM. 60, 84–90 (2017).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. Preprint at (2015). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556

Mallat, S. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant number 2023YFB3211002), SKL for Fine Exploration and Intelligent Development of Coal Resources 2024 Open Fund (Grant number SKLCRSM24KFA06) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 42274165).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guangui Zou: Supervision, Conceptualization, Implementation, Methodology, Data Acquisition, Analysis, Writing-Original Draft. Chengyang Han: Conceptualization, Implementation, Methodology, Data Acquisition, Analysis, Software, Writing-Original Draft. Hen-Geul Yeh: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Analysis, Proofreading. Suping Peng: Supervision, Methodology, Analysis, Writing—Review, Proofreading.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, G., Han, C., Yeh, HG. et al. Wavelet-convolutional neural network for fault prediction in coal mine seismic data. Sci Rep 16, 3318 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33312-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33312-z