Abstract

Face masking, face swapping, and face animation are downstream activities that can benefit from face parsing, in which a face image is divided into many semantic regions. Due to the widespread use of cameras, obtaining facial images has become increasingly straightforward. However, pixel-by-pixel manual labeling takes a lot of time and effort, that allows us to investigate approaches based on unlabled data. In this paper, we propose a novel hybrid transfer learning-based approach for face parsing. First, patches are randomly masked in the central region of the face images. The method then proceeds in two stages: a pre-training stage and a fine-tuning stage. In the pre-training stage, the model is able to represent some basic facial features through unlabeled data. Then, the model is adjusted for the face parsing task on a small labeled dataset in the fine-tuning stage. Experimental results on the test sets show that the model can significantly reduce labeling costs. Furthermore, the proposed method outperforms the baseline by 2.9%, 2.16%, and 1.18% of mIoU with 0.5%, 1%, and 10% labeled data, respectively, on the LaPa dataset. Moreover, experimental results on the CelebAMask-HQ test dataset reveal that the masked transfer learning-based approach significantly outperforms the baseline for various labeling samples of the training data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

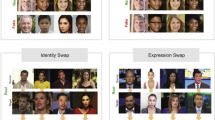

Facial parsing, or facial segmentation has recently gained significant attention due to its unique applications in areas such as face aesthetics1, expression transfer2, and face image synthesis3. As illustrated in Fig. 1, facial parsing aims to assign specific semantic labels to individual pixels within a facial image, such as nose, eye, hair, eyebrow, etc. Building reliable facial-parsing models under controlled conditions has been challenging over the last few decades. Although these approaches have produced encouraging results, their range of applicability is limited by the fact that they frequently suffer substantial degradation in uncontrolled situations. Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs)4,5,6,7 have recently significantly improved segmentation performance. However, most traditional semantic segmentation structures rely on substantial backbones, making them unsuitable for low-end embedded device deployment. For example, VGG164 uses over 500 MB of memory and performs a forward inference in about 100 ms, even on a powerful GPU). Low-latency and high-efficiency attributes are frequently incompatible for large-scale model deployments. In the process of facial parsing, it is important to think about how to maintain a balance between them.

In contrast to ordinary semantic segmentation tasks, facial parsing faces three key difficulties. First, when a person’s face is symmetrical, it can be difficult to tell the difference between their left and right eyes due to their comparable appearances and textures. Second, border ambiguity frequently interacts with annotators’ visual systems, which confounds the learned model (for example, the area between hair and dark hats). Thirdly, deep-level features often carry more semantic meaning, aiding in differentiation between categories. Shallow-level features, in contrast, encode more detailed information. Concatenation is a common technique used to combine different feature blocks, enhancing the model’s feature representation capabilities and extracting features at multiple scales.

Transfer learning, the technique of reusing a pre-trained model on a different task, has become increasingly popular in deep learning. This approach allows for the training of deep neural networks with significantly less data. This is particularly beneficial in real-world scenarios where obtaining millions of annotated data points for training sophisticated models is often challenging. Transfer learning involves leveraging a machine learning model to solve a separate but related problem for which a model has already been pre-trained. By applying the weights learned on a source task “A” to a new target task “B,”8,9,10 we can enhance generalization and achieve better results.

Facial parsing examples that augment the CelebA dataset al.ong with additional facial details2.

To effectively utilize unlabeled facial images for face parsing, we have developed a novel transfer learning approach that is composed of pretraining and fine-tuning phases. In the pre-training phase, first, in the center region of the face images, we specifically mask some patches randomly. Then, for the reconstruction of the masked patches, the model is required. By using unlabeled data, the model enables it to learn meaningful facial feature representations of facial features in the pre-training stage. For face parsing, the model is fine-tuned on a few labeled data after replacing the final layers of the pre-trained unlabeled data with that of the new layers with labeled data available in the pre-training stage. In terms of pixel accuracy, mean accuracy, mean IoU, and mean F1 score, the fine-tuning stage contributes to improved performance and other relevant metrics by incorporating a face parsing decoder.

Summary of this paper’s main contributions:

-

By using transfer learning, we developed a novel framework for face parsing that includes a pre-training stage and a fine-tuning stage. The model is trained on unlabeled data in the pre-training stage, the final layers, which were previously trained for a specific task, are replaced with new layers to learn features relevant to face parsing. Subsequently, for the face parsing task, the model is fine-tuned on labeled data.

-

For pre-training the model, we propose a masked transfer learning technique that reconstructs masked images to learn facial feature representations.

-

To demonstrate the proposed approach’s notable performance improvement over state-of-the-art (SOTA) techniques, extensive tests are run on two challenging benchmarks.

The paper is divided into the following sections. The literature review for facial parsing and segmentation using transfer learning and other cutting-edge technologies is presented in Sect. “Related work”. The proposed framework is thoroughly explained in Sect. “Design Methodology”, with special emphasis on how the network architecture and masked transfer learning work. We provide the experimental results in Sect. “Experimental results and analysis” and compare the qualitative results with SOTA algorithms. Finally, a summary of this paper’s conclusions is provided in Sect. “Conclusion”.

Related work

In this section, we review perior studies relevant to face parsing and segmentation, as well as recentadvances in transfer learning and self-supervised learning technologies in facial analysis. Furthermore, we highlight how the proposed hyprid masked transfer learning approach differs in terms of architecture design, training efficiency and data utilization.

Traditional and deep Learning-Based face parsing approaches

Early face parsing methods relied on probabilistic graphical models to capture local and global dependencies In face segmentation process, Kae et al.11 utilized both local and global condition random fields (CRFs) and restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs). For structured prediction problems, Liu et al.12 incorporated CNNs into graphical models. According to13, exemplar-based segmentation, which transfers partial masks from aligned exemplars to test images, leverages landmarks and SIFT features.

With the rise of deep convolutional networks (DCNNs), more efficient CNN-based architectures have been explored. Liu et al.14 proposed a shallow CNN integrated with a spatially variant RNN to reduce computational costs. In order to parse faces, Guo et al.15 developed a network of encoder-decoders. Moreover, Lee et al.16 developed an adaptive prior approach using RoI Tanh-Warping, achieving state-of-the-art performance by incorporating contextual cues beyond cropped regions such as hair.

Lightweight and efficient network architectures

To achieve real-time performance with limited computational resources, several lightweight CNN models have been developed. SqueezeNet17 reduced parameters via 1 × 1 and parallel convolutions. Despite its significantly reduced parameter count (eightfold compared to AlexNet), it achieves comparable performance. To balance low latency with minimal accuracy loss, MobileNet18,19 introduces deep separable convolutions. By combining channel shuffling and group convolution operations, ShuffleNet20,21 ensures information flow and reduces channel dimensionality. Four unique rules by ShuffleNet v2 are particularly beneficial for creating lightweight systems. Octave convolution22 reduces feature redundancy and memory usage by sharing features in nearby regions and minimizing low-frequency features. Contemporary approaches to accelerate model runtime often incorporate these modules and channel pruning techniques23.

Context-Aware and Multi-Scale segmentation

Enhancing contextual representation is crucial for accurate segmentation. Therefore, exploiting contextual information to improve segmentation’s representational abilities has been the subject of a lot of research. Global pooling is a widely used method in many neural network architectures to extract the relevant contextual information necessary for creating a comprehensive representation of the input data. By introducing an expansion rate, often used in semantic segmentation tasks, dilated convolution24 expands the receptive field. By cascading subnetworks and substages, the DFANet25 combines discriminative features. Multi-scale pyramid pooling employed by PSPNet26, aggregates features at multiple scales. The contextual data is gathered by ACFNet27 from a category viewpoint. ExFuse28 has recently been suggested as a way to enhance the low-level environment by giving the encoder more supervision. Numerous researches have shown that edge contour prediction can be further sharpened and refined with boundary supervision. By adding more boundary supervision to the facial parsing task, CE2P29 enhances edge segmentation in a multi-task learning way. In order to facilitate feature extraction during medical segmentation, ETNet30 imposes fine-grained boundary limitations in the encoder. In contrast to what was stated above, MSFNet31 implements border monitoring with classes using characteristics taken from the backbone.

Transfer learning in facial analysis

Transfer learning has been extensively applied across facial domains, including emotion recognition, attribute classification, and sketch recognition. In the field of deep learning, transfer learning theory is prevalent. But we are unsure of how far it can operate. The neural networks’ adaptability is investigated in the suggested study. While transfer learning can significantly improve efficiency when high-level features are transferred, it’s still advantageous to use transfer learning over training a network from the ground up. With minimal adjustments in transfer learning, we can achieve superior outcomes compared to starting with random weights. This highlights the potential of transfer learning to be far more effective than learning from scratch32. The Advanced Driver Assistance System (ADAS) was enhanced through a non-invasive method of recognizing the driver’s emotional state. This system utilizes a solitary thermal camera to detect and interpret thermal cues associated with emotions. The fact that this particular image was acquired with a thermal camera makes the situation significantly worse in situations with little to no light. In order to improve the user’s experience and safety, a thermal sensor will be incorporated33. Although stress is generally recognized as a serious illness, it can be challenging to determine whether or not someone is experiencing stress. The degree of stress on the individuals’ faces was measured using thermal spatial-temporal data from videos of specific subjects. This can also regulate medication dosage based on stress levels34. To analyze the perception of emotions, temporal data relating to facial temperature is used in35. First, facial regions are split into smaller parts, and statistical points connected to data on facial temperature are extracted. The extracted features, related to differential temperature, are then used to create a histogram and analyzed using the difference matrix pertaining to facial temperature. For each feature, classification is performed using discrete hidden Markov models. Four key steps are physiological signal processing for emotion recognition: pre-processing collected signals, biological feature extraction, matching, and feature classification36. Each part examines the statistics, performance, and characteristics of modern approaches. The relationship between the variables influencing human emotions and emotional state is crucial for model simplification. So, while evaluating emotions, psychological signals might be quite beneficial. A wearable wristband with a physiological signals acquisition system was created by Krupa et al.37. The SVM method can classify “Autism Spectrum Disorder” (ASD) as influenced by emotions like neutral, involvement, and happiness. Emotions are categorized using variations in the HR and SR galvanic potentials. To elicit authentic emotional facial expressions, Esposito et al.38 conducted a meticulously designed experiment using high-emotion videos. They provided comprehensive details regarding the experimental setup, image acquisition conditions, stimulus generation, and statistical analysis. Their research focused on the impact of emotions on memory word recognition tasks, utilizing experimental data to investigate these effects. Thermal and audible emotional facial expressions are included in the author’s dataset for her investigations. Wang et al.39 explores the application of deep residual networks for visual categorization tasks, including action recognition, human action recognition, and image classification. Transfer learning is employed to tackle these challenges effectively. Moreover, transferring learning to the action detection process and image classification can address common issues like view divergence and concept drift.

Self-Supervised and masked Pre-Training approaches

Self-supervised learning has recently emerged as a key strategy for representation learning without explicit labels40,41. These methods can be broadly classified into context-based, temporal-based, and contrast-based approaches. Among context-based techniques, masked image modeling (MIM) has gained particular attention. Early work by Vincent et al.42 introduced denoising autoencoders, while Doersch et al.43 proposed spatial prediction tasks between random image patches. Zhang et al.44 extended this to colorization-based learning, teaching models to predict missing visual information. Such methods encourage robust feature extraction that transfers effectively to downstream tasks such as segmentation.

However, existing MIM and self-supervised models are often domain-agnostic and do not account for facial structural priors, which are crucial for accurate parsing. Moreover, encoder–decoder decoupling during pre-training limits the decoder’s ability to generalize for fine-grained facial segmentation. These limitations motivate the development of hybrid and task-aware pre-training mechanisms.

In this paper, we propose a novel face parsing framework that uses unlabeled facial images to their fullest potential. There are two steps in the framework: pre-training stage and fine-tuning stage. Images are randomly masked in the central area during the pre-training stage, and the reconstructed images are subsequently supplied into the model. For this pre-training stage, no labels are required to utilize any image. It is anticipated that the pre-trained model would reflect facial features accurately. By utilizing the principles of transfer learning, we also replace the final layers that have learned a particular task with the new layers that will learn features particular to face parsing. The proposed method significantly outperforms supervised learning when incorporating the transfer learning-based pre-training stage. Furthermore, experimental results indicate that our method achieves SOTA performance on the LaPa and CelebAMask-HQ datasets.

Design methodology

The proposed masked transfer learning (MTL) strategy involves two stages, as shown in Fig. 2. First, pre-training a neural network on masked images without parsing labels to reconstruct inputs. Second, fine-tuning it on labeled images, replacing final layers to learn facial parsing and segmentation features like shapes, edges, and colors. To evaluate the performance of the proposed MTL model, we use two synthetic standard benchmarks of face images for face parsing: the LaPa48 and CelebAMask-HQ16.

Proposed MTL Pre-training stage

This paper proposes a novel masking method for extracting semantic features from unlabeled images to improve neural network pre-training. Selected image regions (32–64 px patches, 128 total) are occluded and reconstructed using a deep CNN. For facial images, masking is limited to the central region containing the face to compute reconstruction loss. This study defines the central area as the portion that the entire image consists of two-thirds of it. To reconstruct the masked image, we use a simple R Decoder with a single convolutional layer, followed by an encoder based on UNet++45. The encoder processes a masked input of size\(3 \times H \times W\), producing an \(n \times H \times W\)feature output. Furthermore, the \(3 \times H \times W\) image is reconstructed by a simplistic R Decoder based on the input received from the encoder, i.e., \(n \times H \times W\)features. Figure 2 depicts the overall pre-training stage framework.

Fine-tuning stage

The encoder can acquire facial feature representation after the pre-training phase. We use the same encoder in the fine-tuning stage to learn the facial semantic characteristics by creating a facial parsing decoder in the transfer learning process, as shown in Fig. 3. In the transfer learning process, we replace the final layers with the new layers by employing a facial parsing decoder.

Architecture details

The proposed method employs the same encoder twice with distinct decoders. Initially, a masked learning strategy enables the encoder to learn basic facial representations. Once these semantic features are captured, new layers replace the initial ones, and the facial parsing decoder learns more complex features. Using a UNet + + with ResNet50 core51, the encoder ensures robustness, while both R and FP decoders use only one convolution layer, emphasizing the encoder’s critical role in pre-training and fine-tuning.

Training process

For the facial parsing challenge, we use masked images in the datasets to pre-train our encoder and then enhance the encoder performance by connecting it to FP Decoder. The pre-training stage aims to reconstruct the missing patches from the masked input image. Here, we compute the reconstruction loss during the pre-training stage, as shown in Eq. (1).

where \(L\left( {\widehat {{{p_{ij}}}}} \right.,\left. {{p_{ij}}} \right)\) represents the difference between the original and the reconstructed image in terms of the pixel loss, \({W_s}=W/6,{H_s}=H/6,{W_e}=5W/6,{H_e}=5H/6\).

Facial parsing is a process that categorizes each pixel of an image into a specific semantic label representing a facial component. By employing a combined loss function, we aim to establish more precise decision boundaries and ensure accurate data distribution, as outlined in Eqs. (2) and (3).

where \({\lambda _{cr - ent}}\) and \({\lambda _{dice}}\) are hyperparameters. The value of \({\lambda _{cr - ent}}\) determines how much emphasis is placed on minimizing the cross-entropy loss, and the value of \({\lambda _{dice}}\) determines the relative contribution of the dice loss term compared to the cross-entropy loss term. \({L_{cr - ent}}\) and\({L_{dice}}\) represent the cross-entropy and dice loss, and \(\widehat {p}\) represent the ground truth and predicted segmentation values, and\(\langle p,\widehat {p}\rangle\) represents the dot product between the ground truth and predicted segmentation values. \(\alpha\) controls the balance between foreground and background classes in the cross-entropy term. By adjusting the value of \(\alpha\), the weighting between these two classes can be controlled. \(\gamma\) applies a power transformation which help in controlling the impact of the predicted probabilities on the loss function. Higher values of \(\gamma\) place more emphasis on the misclassified pixels, while lower values give more importance to the well-classified pixels.

Hybrid approach for facial semantic classification

Figure 4 illustrates the transfer learning process where initial layers extract basic facial features. In pre-training, the encoder and R decoder learn facial semantic representations. During fine-tuning, the R decoder is replaced by the FP decoder while retaining the encoder to enhance facial parsing accuracy. Training then uses LaPa and CelebAMask-HQ datasets to evaluate the proposed MTL algorithm against standard benchmarks.

The proposed method employs a combination of transfer learning and the standard classification technique46. Facial features are extracted from the images using transfer learning. Concurrently, Multiclass Support Vector Machine (SVM) is utilized due to its exceptional efficiency in categorizing data with multiple classes. To ensure the effectiveness of SVM, it is crucial that the dataset is labeled, as SVM is renowned for its ability to distinguish between labeled data. Figure 5 shows the architecture of the hybrid (Transfer Learning + SVM) approach for facial feature classification.

Furthermore, we employed a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to construct a multi-class hyperplane that separates distinct facial features. Support vectors, representing the extreme points of a specific class, were instrumental in distinguishing between these features. These support vectors proved to be effective in differentiating distinct facial features within this study.

The SVM classification with a reduced hyper-plane (SVM-RH) is illustrated in Fig. 6. The Nth class is isolated from the remaining N-1 classes to minimize classification error and identify the optimal separating the Nth class from all N-1 classes by a hyper-plane in SVM-RH. Afterwards, the algorithm determines the class of any remaining samples in the “N-1” class. Any remaining “N-1” class samples are then classified according to the algorithm. In order to determine the next class to be isolated from the “N-1” classes, one class sample from the “N-2” class samples is isolated. Next, we determine the hyperplane that separates these data. This process continues until the class samples’ data can be categorized. In this way, the data of class samples is classified until it is complete. As a result, the required hyper-plane for data separation is minimized47. The amount of training time decreases as categorization accuracy increases in SVM-RH.

Support vector machine with binary decision tree (SVM-BDT)

The SVM-BDT was developed by Madzarov et al.54 to address the issue of a distributed class in the Binary tree of SVM. This approach combines SVM’s high classification accuracy with efficient tree architecture computing. This architecture generates a tree with N-1 internal nodes, each responsible for evaluating there are N leaf nodes, each containing the class label for a subset of the data, and a binary decision function. The SVM-BDT prohibited the class from appearing on either side of the tree. As a result, it is more efficient than the binary tree of SVM47 since it does not check the class on both sides of the tree. This approach’s disadvantage is that it starts by looking for cluster centers in the data using a clustering algorithm. The binary tree depicted in Fig. 7 categorizes the data into 10 distinct classes. Nodes in the tree consist of four internal and 10 leaf nodes. An individual leaf node represents a specific class to which the sample belongs.

Experimental results and analysis

Datasets

In order to evaluate our proposed MTL technique, we use two synthetic standard benchmarks of face images for face parsing: the LaPa48 and CelebAMask-HQ16. The LaPa dataset contains in total 22,176 facial images and precise pixel-by-pixel semantic labels of 10 distinct face-part categories, from which it is partitioned into 18,176, 2,000, and 2,000 images for training, testing, and validation. The CelebAMask-HQ dataset contains 24,183, 2,824, and 2,993 images for training, testing, and validation, along with 18 semantic face-part categories.

Evaluation metrics

The proposed method is evaluated on LaPa and CelebAMask-HQ datasets, the conventional Pixel Accuracy (pix Acc), Mean Pixel Accuracy (Mean Acc), Mean F1 score (Mean F1), and Mean mIoU (Intersection-over-Union) metric. Furthermore, we contrast the F1 score performance of our proposed MTL with that of other benchmarks to ensure consistency with existing research.

Implementation details

Throughout both the pre-training and fine-tuning stages, in our transfer learning experiments, we employed random rotation and scale augmentation. To be more precise, the rotation angle is chosen randomly for each step between (−30o, 30o) and (−15o, 15o). For pre-training and fine-tuning stages, a scale factor between (0.75, 1.25) and (0.8, 1.2) is randomly chosen. The hyper-parameters of cross-entropy and dice are set as 0.5. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is used to optimize pre-training and fine-tuning stages in MTL. In MTL, the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) method is used to optimize the pre-training and fine-tuning stages. There are \(480 \times 480\) inputs for the pre-training and fine-tuning stages, 16 batches, and a learning rate of 0.0001 for the pre-training, and for fine-tuning, we select the learning rate of 0.00001.

First, we pre-train the encoder using Unet + + and 500 epochs for R Decoder. A pre-trained model from ImageNet serves as the ResNet50 initialization. In the initial pre-training phase, we leverage a transfer learning model to initialize the entire encoder. Subsequently, in order to refine the facial parsing features, we use data from LaPa and CelebAMask-HQ datasets, utilizing the same encoder and FP Decoder. There are two options for evaluating the effectiveness of our strategy during the fine-tuning stage. In order to fine-tune, we first randomly chose 0.5%, 1%, and 10% from the labeled training data. We create three alternative line graphs for these experiments, and the resultant performance is the average of all three sampled data. After that, we consider the whole training dataset with labels for fine-tuning and compare it with the SOTA benchmarks.

Performance evaluation

By comparing our proposed method with a baseline model, we evaluated the efficacy of masked transfer learning that was trained directly on labeled data without masked learning in the pre-training phase. When various labeling samples were considered, the outcomes of MTL and baseline models for the LaPa and CelebAMask-HQ datasets are depicted in Figs. 8, 9, 10 and 11.

It is essential to observe that the proposed approach significantly surpasses the baseline model on two benchmarks. Notably, the proposed method outperforms the baseline when there is 0.5%, 1%, and 10% of the LaPa dataset labeled data, respectively with 2.9 mIoU, 2.16 mIoU, and 1.18 mIoU. When results from the whole training set on the LaPa dataset are compared, the proposed method performs 0.25 mIoU better than the baseline. The CelebAMask-HQ dataset also demonstrates that MTL outperforms the baseline by a substantial margin for different labeling samples of the training data on the comparative outcomes. Furthermore, the proposed MTL algorithm enhances pixel accuracy to 0.81, 0.38, and 0.11 compared to the baseline when 0.5%, 1%, and 10% labeled training data are utilized in the LaPa dataset. Similarly, MTL exhibits an improvement in pixel accuracy with 0.1, 0.18, and 0.79 against the baseline when 0.5%, 1%, and 10% labeled training data are employed in the CelebAMask-HQ dataset.

In terms of the F1 score, we evaluate the performance of our proposed method as opposed to SOTA cutting-edge techniques using the complete training data. In Tables 1 and 2, we show the performance evaluation comparisons between the proposed method and other SOTA techniques49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56 trained on the LaPa dataset and CelebAMask-HQ dataset, respectively. In LaPa, our method performs at a cutting-edge level, with a mean F1 score of 92.90%, and in CelebAMask-HQ, we achieved a mean score of 90.50%. Furthermore, our proposed method surpasses other techniques in accurately segmenting various facial semantic components such as the skin, hair, left eyebrow, right eyebrow, left eye, right eye, inside mouth, lower lip, upper lip, and nose.

In the pre-training stage, the encoder is pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. Without transfer learning, the loss converges faster, and mIoU improves more rapidly, as shown in Figs. 12 and 13. However, after 400 epochs, the model is guided by the proposed MTL approach to perform better. It demonstrates how easily local optimization can ensnare the original model. In other words, the model is helped to surpass the local optimal level by the masked transfer learning procedure. Figure 12 shows the overall loss against epochs for MTL and baseline models using different labeling samples. In contrast, Fig. 13 depicts the mean intersection over union (mIoU) against MTL and baseline models’ epochs using different training data labeling samples.

Discussion

We thoroughly investigate the efficacy of pre-training based on masked transfer learning. Our algorithm was tested on the CelebAMask-HQ dataset, and the necklace portion of the model performed poorly, achieving a mean intersection over union (mIoU) of 0.01. An analysis of the data for every facial element in the CelebAMask-HQ dataset shows that the necklace’s pixels make up just 0.016% of all the pixels. Baseline models, when trained exclusively with semantic masks, tend to prioritize other categories, ultimately converging on a local optimum. Consequently, categories with a limited number of pixels, such as necklaces, are not effectively learned.

Facial parsing results with CelebAMask-HQ dataset and feature activation. (a) Images from CelebAMask-HQ dataset (b) Ground Truth (c) Predicted Image (d) Pre-training parsing results of baseline model (e) Pre-training parsing results with proposed MTL model (f) Encoder feature activation map from proposed MTL model.

Figure 14 illustrates every \(16 \times 512 \times 512\) sized feature activation map generated from the encoder. The necklace portion seen in Fig. 14 (a) is not activated on the baseline activation maps. To guarantee the model’s capacity to accurately reconstruct the image within our proposed MTL framework, the training process is conducted independently. This approach allows for a more precise and effective image reconstruction, ultimately enhancing the overall performance of our technique. As a result, it forces the model to emphasize each category fairly. Our model is capable of identifying the necklace feature and activating the corresponding regions using the suggested masked MTL pre-training, as illustrated in Fig. 14 (f). Additionally, Figs. 15 (a) and (b) illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed MTL on the LaPa dataset.

Generally, the existing face parsing/segmentation models in the literature frequently lack contextual information, which often leads to suboptimal segmentation performance for small objects like the “necklace” region. In the proposed method, facial features are extracted from images by using transfer learning in order to overcome this problem effectively. Additionally, we employed a Multiclass Support Vector Machine (SVM) for our categorical classification tasks due to its proven efficiency in handling such problems. As illustrated in Figs. 14 and 15, we present the qualitative findings of our experiments on CelebAMask-HQ and LaPa datasets. More smooth and natural results can be obtained using the proposed method.

Ablation study

We perform an ablation study to dissect the contribution of the key components in our proposed MTL framework. The following configurations are compared on the CelebAMask-HQ dataset using 10% of the labeled training data: (A) Baseline: supervised learning from scratch without pre-training; (B) MTL with random masking across the entire image; (C) MTL (central masking) fine-tuned using only cross-entropy (CE) loss; (D) The full proposed model: MTL (central masking) fine-tuned with the combined cross-entropy and dice loss. Table 3 clearly demonstrate the incremental benefits of each component in the proposed framework. The full model (D) achieves the highest mIoU and Mean F1 score. Most notably, the central masking strategy (C) provides a significant boost over random masking (B), particularly for facial components, validating our hypothesis that focusing reconstruction on the central face region forces the model to learn more relevant facial features. Furthermore, the combined loss function (D) outperforms the cross-entropy loss only (C), especially in improving the IoU for smaller and more challenging classes like necklace and inside mouth, by better handling class imbalance.

Furthermore, we conduct a fine-grained analysis of the proposed model performance on small semantic categories, to assess its robustness and ability to handle class imbalance. We define “small categories” as those constituting less than 1% of the total pixels in the dataset, such as necklace, left eyebrow, and right eyebrow in CelebAMask-HQ dataset. Table 4 compares the per-class IoU of our proposed MTL model (D) with the baseline (A) and a recent state-of-the-art method, Han et al.56. The results indicate that our method provides a substantial performance gain on these challenging small categories. For instance, the IoU for the necklace class jumps from 0% in the baseline to 15.32% in our model. This improvement is attributed to the pre-training stage, which forces the model to learn a more complete and equitable feature representation for all image regions to perform reconstruction, thereby preventing it from ignoring rare classes.

In conclusion, the ablation studies confirm the necessity of each component in our hybrid framework. The training efficiency analysis highlights its practical value in low-data regimes, and the examination of small-category performance underscores its superior generalization and robustness to class imbalance. These comprehensive experiments solidify the persuasiveness of the proposed MTL approach for face parsing.

Although the proposed MTL framework demonstrates consistent performance on the LaPa and CelebAMask-HQ datasets, future work will focus on cross-dataset evaluation to further assess generalization capability across heterogeneous face parsing benchmarks. Additionally, we plan to conduct ablation studies to disentangle the effects of individual components such as the masking strategy, encoder pre-training, and fine-tuning layers, to better understand their relative contributions for performance improvements.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a novel transfer learning technique in order to reduce a load on dense face part annotations of manual labeling. The proposed method aims to reconstruct masked images by initially pre-training the Unet + + model using patches extracted from the central region of the masked images. Following pre-training, our model is refined using the face parsing dataset target faces after the final pre-training layers are replaced with the new layers that should obtain precise facial semantic characteristics using a facial parsing decoder. Through feature visualization, the fine-tuned MTL model can accurately identify feature activations for each category, even those with extremely low frequencies. The experiments demonstrate that the proposed MTL model significantly improve parsing performance, particularly for classes with extremely low proportions (like the necklace in CelebAMask-HQ). We believe that additional face-related tasks such as face generation, face landmark identification, and face attribute learning, can also be achieved using our proposed MTL-based pre-training and fine-tuning method.

Although the proposed method achieves promising results, it relies on a fixed central masking strategy that may not generalize well to occluded or side-view faces. The fine-tuning stage still requires a minimal amount of labeled data, and the pre-training process remains relatively computationally demanding for real-time deployment. Future efforts will aim to improve model robustness through adaptive masking and multi-view learning, integrate self-supervised or contrastive learning to further reduce labeling needs, and extend the proposed framework to tasks such as face synthesis, landmark detection, and facial attribute estimation. Furthermore, we will examine the possible efficacy of transfer learning-based pre-training for small portions of labeled data.

Data availability

The synthetic datasets CelebAMask-HQ [16] and LaPa[48] are freely available on: [https://github.com/switchablenorms/CelebAMask-HQ](https:/github.com/switchablenorms/CelebAMask-HQ), and [https://github.com/lucia123/lapa-dataset](https:/github.com/lucia123/lapa-dataset), respectively. Furthermore, the algorithmic implementations used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Ou, X. et al. Beauty eMakeup: A Deep Makeup Transfer System. Proceedings of the 24th ACM international conference on Multimedia, (2016).

Zhang, D. et al. Content-Adaptive sketch portrait generation by decompositional representation learning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 26 (1), 328–339 (2017).

Song, W. et al. AttriDiffuser: adversarially enhanced diffusion model for text-to-facial attribute image synthesis. Pattern Recogn. 163, 111447 (2025).

Shelhamer, E., Long, J. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015: 3431–3440. (2015).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W., Frangi, A. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015 MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9351. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Szegedy, C. et al. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. in AAAI. (2017).

Kenei, J. & Moso, J. Classification of heartbeats using convolutional neural network with range normalization. Medinformatics 2 (2), 120–131 (2025).

Pan, S. J. & Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 22 (10), 1345–1359 (2010).

Yang, J., Wang, G., Xiao, X., Bao, M. & Tian, G. Explainable ensemble learning method for OCT detection with transfer learning. PloS One, 19(3), 1–17 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Sample-Cohesive Pose-Aware contrastive facial representation learning. Int. J. Comput. Vision. 133 (6), 3727–3745 (2025).

Kae, A. et al. Augmenting CRFs with Boltzmann machine shape priors for image labeling. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2013, 2019–2026 (2013).

Liu, S. et al. Multi-objective convolutional learning for face labeling. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015: 3451–3459. (2015).

Smith, B. M. et al. Exemplar-Based Face Parsing. 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3484–3491. (2013).

Liu, S. et al. Face Parsing Via Recurr. Propag. ArXiv:1708.01936. (2017).

Guo, T. et al. Residual Encoder Decoder Network and Adaptive Prior for Face Parsing. in AAAI. (2018).

Lee, C. H. et al. Maskgan: Towards diverse and interactive facial image manipulation. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 5549–5558. (2020).

Iandola, F. N. et al. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and < 1 MB model size. ArXiv:1602.07360. (2016).

Howard, A. G. et al. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications ArXiv:1704.04861. (2017).

Sandler, M. et al. MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 4510–4520 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. ShuffleNet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 6848–6856 (2018).

Ma, N. et al. ShuffleNet V2: Practical Guidelines for Efficient CNN Architecture Design. in ECCV. (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Drop an Octave: Reducing Spatial Redundancy in Convolutional Neural Networks With Octave Convolution. 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), : pp. 3434–3443. (2019).

Yin, L. et al. AFBNet:A lightweight adaptive feature fusion module for Super-Resolution algorithms. CMES- Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 140 (3), 2315–2347 (2024).

Ning, L., Zhang, Z., Ding, W., Shao, D. & Zhu, Y. Multilevel distribution alignment for multisource universal domain adaptation. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 36 (9), 17365–17379 (2025).

Li, H. et al. DFANet: Deep Feature Aggregation for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), : pp. 9514–9523. (2019).

Zhao, H. & Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017: pp. 6230–6239. (2017).

Zhang, F. et al. ACFNet: Attentional Class Feature Network for Semantic Segmentation. 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), : pp. 6797–6806. (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. ExFuse: Enhancing Feature Fusion for Semantic Segmentation. in ECCV. (2018).

Liu, T. et al. Devil in the Details: Towards Accurate Single and Multiple Human Parsing (ArXiv, 2019). abs/1809.05996.

Zhang, Z. et al. ET-Net: A Generic Edge-aTtention Guidance Network for Medical Image Segmentation. in MICCAI. (2019).

Si, H. et al. Real-Time Semantic Segmentation via Multiply Spatial Fusion Network. ArXiv, abs/1911.07217. (2020).

Yosinski, J. et al. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? in NIPS. (2014).

Kolli, A. et al. Non-intrusive car driver’s emotion recognition using thermal camera. in Proceedings of the Joint INDS’11 & ISTET’11. (2011).

Wang, J., Wang, C., Guo, L., Zhao, S., Wang, D., Zhang, S.,… Tian, Q. (2025). MDKAT:Multimodal Decoupling with Knowledge Aggregation and Transfer for Video Emotion Recognition.IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology.

Liu, Z. & Wang, S. Emotion recognition using hidden Markov models from facial temperature sequence. In D’Mello, S., Graesser, A., Schuller, B., Martin, JC. (eds) Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6975. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. (2011) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24571-8_26.

Wu, N., Jiang, H. & Yang, G. Emotion Recognition Based on Physiological Signals. In Advances In Brain Inspired Cognitive Systems (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012).

Krupa, N. et al. Recognition of emotions in autistic children using physiological signals. Health Technol. 6 (2), 137–147 (2016).

Esposito, A. et al. A naturalistic database of thermal emotional facial expressions and effects of induced emotions on memory. In: Esposito, A., Esposito, A.M., Vinciarelli, A., Hoffmann, R., Müller, V.C. (eds) Cognitive Behavioural Systems: COST2012. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 7403. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 158–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-34584-5_12 (2012).

Wang, T. et al. ResLNet: deep residual LSTM network with longer input for action recognition. Front. Comput. Sci. 16 (6), 166334 (2022).

Dike, H. U. et al. Unsupervised Learning Based On Artificial Neural Network: A Review. IEEE International Conference on Cyborg and Bionic Systems (CBS), 2018: pp. 322–327. (2018).

Dheivya, I. & Kumar, G. S. VSegNet–A variant SegNet for improving segmentation accuracy in medical images with class imbalance and limited data. Medinformatics 2 (1), 36–48 (2025).

Vincent, P. et al. Stacked denoising autoencoders: learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 11, 3371–3408 (2010).

Doersch, C., Gupta, A. K. & Efros, A. A. Unsupervised Visual Representation Learning by Context Prediction. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2015: pp. 1422–1430. (2015).

Zhang, R. & Isola, P. and A.A. Efros. Colorful Image Colorization. in ECCV. (2016).

Zhou, Z. et al. UNet++: redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 39 (6), 1856–1867 (2020).

Zeiler, M. D. and R. Fergus. Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. in ECCV. (2014).

Liu, Y., Wang, R. & Zeng, Y. S. An Improvement of One-Against-One Method for Multi-Class Support Vector Machine. in. International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics. 2007. (2007).

Liu, Y. et al. A New Dataset and Boundary-Attention Semantic Segmentation for Face Parsing. in AAAI. (2020).

Luo, L. & Xue, D. Feng ehanet: an effective hierarchical aggregation network for face parsing. Appl. Sci. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093135 (2020).

Te, G. et al. AGRNet: adaptive graph representation learning and reasoning for face parsing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. PP, 1–1 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. A Masked Self-Supervised Pretraining Method for Face Parsing (SSRN Electronic Journal, 2022).

Zheng, Q. et al. Decoupled Multi-task Learning with Cyclical Self-Regulation for Face Parsing. in 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2022).

Sarkar, M. et al. Parameter efficient local implicit image function network for face segmentation. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR). 2023, 20970–20980 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. General Facial Representation Learning in a Visual-Linguistic Manner. in 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2022).

Han, S. & Yoon, H. Advancing face parsing in Real-World: synergizing Self-Attention and Self-Distillation. IEEE Access. 12, 29812–29823 (2024).

Han, C., Cheng, P. & You, Z. A light end-to-end comprehensive attention architecture for advanced face parsing. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 26 (3), 89–109 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shahadat Shahed: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shahriar Md Arman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Samiul Haque Sami: Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Afraa Z. Attiah: Software, Validation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Abeer Hakeem: Validation, Software, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Linda Mohaisen: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Validation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Mahmoud Emam: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. All authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahed, S., Arman, S.M., Sami, S.H. et al. A hybrid approach for facial parsing using transfer learning. Sci Rep 16, 3405 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33366-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33366-z