Abstract

Customs revenue represents a major source of funding for most governments. Accordingly, customs administrations worldwide have promoted advanced analytics techniques to detect fraud and enhance revenue collection. However, inspecting imported commodities and auditing tax declarations is time-consuming, costly, and dependent on the inspector’s expertise. Consequently, machine learning-based solutions have become critical for identifying fraud and minimizing revenue at risk. This paper applies the Dual-learning XGBoost-Based Approach (DXGBA) to the customs fraud detection domain. It demonstrates its ability to jointly detect fraud and estimate the corresponding revenue impact within a single boosting framework. The problem of under-valued imports is formulated as a dual supervised learning task, where DXGBA performs simultaneous classification and regression via a joint objective. The model ranks declarations based on their predicted revenue risk. Based on this ranking, it supports decision-makers in prioritizing inspections and enables maximizing revenue recovery under limited auditing capacity. To alleviate class imbalance, resampling strategies including the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) and Random Undersampling (RU) were investigated. DXGBA classifies declarations as “fraudulent” or “non-fraudulent” and estimates the revenue at risk. Comparative experiments on a benchmark customs dataset show the high performance of DXGBA over single-task and state-of-the-art baselines. Results indicate that DXGBA recovers up to 87.98% of revenue by auditing only 10% of declarations. Furthermore, two enhancement pipelines, including tree-based embeddings and autoencoder-based deep feature representations, were examined. They both yield further gains in accuracy and revenue estimation performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Customs authorities can be presented as governmental entities responsible for regulating the movement of commodities and individuals across borders, as well as collecting customs duties and taxes from merchants and individuals1. Every year, customs authorities worldwide process millions of customs declarations filed by government agencies, logistics companies, and various other entities involved in international trade. Typically, import declarations contain financial data crucial to the activities of importers and exporters. One should notice that the incidence of fraudulent trade activities increases with the continued expansion of cross-border commerce2. In fact, customs duty is typically proportional to the value of the imported good. Specifically, it depends on the type of commodity, its country of origin, and the applicable trade agreements. False declarations of any of this information may yield a fraudulent transaction3. Globally, tariff code misclassification and undervaluation of goods pose major risks for customs authorities. In other words, importers report commodity values at prices inferior to their actual worth, mostly to evade customs duties completely or partially customs duties1.

To ensure traders’ compliance, customs perform physical inspections to verify the conformity of the imported goods with the declarations. Typically, this conventional process includes the investigation of numerous documents for the sake of identifying suspicious shipments1. However, such conventional inspections are constrained by the substantial volume of international trade, in addition to the diminished inspection capacity of customs authorities4. In fact, according to the World Bank, the proportion of physical inspections conducted in 72% of countries globally has remained below 30%5. Furthermore, the vast amount of data that customs authorities collect and maintain in their systems is not being utilized effectively to improve the detection rate of customs fraud4. Essentially, most case selection procedures rely on inspectors’ intuition and previous experience, with a notable lack of data-driven analysis of the collected declarations6. Moreover, traders innovate continuously and employ novel methods to evade customs control. This has triggered the need for advanced and robust fraud detection strategies7,8.

Better customs fraud detection would yield an increased revenue generation and strengthen a country’s trade competitiveness. Consequently, customs administrations put more effort into managing the substantial volume of cross-border flows effectively with reduced oversight1. Moreover, risk analytics and management strategies have been established for better illicit trade detection and government revenue boosting without disrupting legitimate trade flows1,2. The earliest fraud detection approaches were typically deployed as rule-based techniques9. Although such techniques are simple and interpretable, they require human expertise and may be prone to subjective intuitions. They are also less adapted to the continued evolution of fraudulent practices10. Besides, implementing rule-based models has remained challenging, especially when the number of proficient officers capable of executing and refining the rules is limited11. Thus, one can conclude that rule-based fraud detection solutions are difficult to build and maintain. Moreover, they proved to be subject to expert knowledge and expertise11. Despite these limitations, it is worth noting that the majority of customs administrations continue to employ rule-based techniques12.

Currently, the World Customs Organization (WCO)13 is exploring the potential of machine learning and data mining techniques for fraud detection14,15,16. Moreover, several customs authorities have effectively implemented machine learning models for their fraud detection systems17. They partially succeeded in handling the vast volume of transactions and enhancing their ability to capture fraudulent behavior through the automation of fraud detection using machine learning techniques17. Automating the inspection process has not only enhanced the fraud detection performance. It has also boosted the operational efficiency and reduced the need for human resources conducting inspections1.

In order to preserve the trade flow and support their economic targets, governments have required customs administration to maintain low inspection rates. This triggered the design of intelligent solutions intended to detect customs fraud without exhausting the available inspection resources. Although some supervised machine learning based approaches have addressed the predictive mining task1,2,3,4,12,17,18, customs administrations still face the challenge of prioritizing the detected cases in order to maximize the revenue. In other words, although existing works have succeeded in detecting fraudulent cases accurately, they have not mitigated the prioritization challenge. In particular, their outcomes do not allow customs authorities to collect most of the revenue at risk without exceeding their inspection and audit capacity.

This research applies our previously developed Dual-learning XGBoost-Based Approach (DXGBA)19 to the critical domain of customs fraud detection. It demonstrates how the model can simultaneously detect fraud and estimate revenue loss in real-world customs operations. The model simultaneously classifies customs declarations as fraudulent or non-fraudulent and predicts the associated revenue at risk. Beyond detection, the approach is designed to maximize the revenue to be collected by prioritizing the inspection of specific trade flows based on the predicted fraud risk. DXGBA, a gradient boosting-based technique, carries out classification and regression tasks concurrently using a joint learning objective function. When applied in the customs context, it allows customs authorities to classify taxpayers into compliant or non-compliant. Moreover, it determines the priority list that should be audited first in order to optimize the revenue without exhausting the inspection resources. Beyond the baseline DXGBA, this study also evaluates enhanced variants that integrate tree-based embeddings and neural features to enrich representation.

Related works

The development of machine learning for customs fraud detection has grown from traditional supervised learning approaches to more sophisticated approaches. Early research focused on using conventional machine learning approaches such as logistic regression20, decision trees, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)21 to identify fraudulent customs declarations. On the other hand, recent approaches focused on leveraging a combination of machine learning paradigms, including ensemble methods and deep learning, to efficiently handle complexity in custom variables. More recent research has moved toward models capable of addressing multiple objectives simultaneously, including both fraud detection and revenue estimation. The subsequent review critically evaluates the primary contributions of these developments and highlights their methodological advancements and constraints. It also shows how the gap in current approaches motivates the application of the Dual-learning XGBoost-Based Approach in the customs domain.

Traditional supervised classifiers, including ANNs21, Logistic Regression20, Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines (SVMs)22, Random Forests23, and Gradient Boosted Trees24, were the primary methods used in earlier studies to identify fraudulent declarations3,25,26,27. While these methods achieved reasonable accuracy, they share several drawbacks. First, they have limited adaptability to dynamic fraud patterns. In other words, static models such as decision trees or SVMs cannot efficiently adapt to emerging behaviors of traders. Another limitation is the sensitivity to class imbalance. As shown in some studies3,25, most models rely heavily on external balancing methods like SMOTE28 to maintain good performance. Furthermore, most of these models lack interpretability. For instance, neural-network-based methods21,26 offer little insight into why transactions are classified as suspicious. Consequently, traditional supervised models often fail to generalize well to the highly imbalanced and heterogeneous nature of customs data.

Furthermore, unsupervised learning has been implemented to identify irregular declaration patterns in order to mitigate dependence on labeled data29,30,31,32. Clustering and density-based models, such as spectral clustering with Kernel Density Estimation29 and two-stage clustering-outlier detection30, are designed to identify fraudulent shipments. Recent works have explored deep unsupervised frameworks such as autoencoders and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)31,32. They are used to learn the approximate distribution of the dataset, identify anomalies, and achieve improved reconstruction-based anomaly scoring. However, these approaches exhibit key limitations. One of the limitations is the weak discrimination between fraud types. More specifically, clustering-based models detect anomalies but cannot distinguish between undervaluation, misclassification, or false origin. Another problem with these approaches is the absence of revenue estimation. None of these models incorporates the financial estimation into the learning process. Another drawback of unsupervised learning is the dependence on threshold tuning. The detection performance often depends on arbitrary thresholds rather than robust probabilistic modeling. Thus, unsupervised models have valuable detection capabilities but fail to provide risk prioritization.

Hybrid and dual-learning frameworks have also been proposed. Some studies applied ensemble strategies that combine SVMs22, Random Forests, and Naïve Bayes under boosting or voting schemes12,14,17. Although ensemble learning improved accuracy and robustness, these studies generally optimized classification only and overlooked revenue recovery and interpretability. Similarly, the XBNet model2 integrated gradient-boosted trees with deep neural networks to enhance feature learning. However, XBNet2 focuses on single-task fraud classification and does not support simultaneous regression. More recently, the Dual-Task Attentive Tree-aware Embedding (DATE)1 model has made an advancement in the field of simultaneous revenue estimation and classification. Despite its novelty, DATE presents notable limitations. First, it has a high computational cost due to multi-head attention mechanisms and complex embedding layers. Another limitation is that it depends on pretraining to extract cross features, which may not generalize across datasets. Lack of gradient-boosting interpretability is another limitation. The model’s attention-based mechanism lacks the transparency and explainability inherent in boosting-based frameworks. Although DATE1 is the first dual-task model for fraud detection and revenue estimation, its architecture depends heavily on attention-based cross-feature pretraining and deep embedding layers. This dependence reduces interpretability and scalability for real-world customs deployment. In contrast, customs administrations prioritize transparent and computationally efficient models that can operate on real-time data streams. Therefore, a dual-task framework based on gradient boosting is still absent in the literature. Such a framework would retain the interpretability and low-overhead learning properties of tree-based models.

These shortcomings indicate a clear research gap and motivate the DXGBA model. It lies in the absence of a scalable and interpretable dual-task model that integrates the structured learning power of gradient boosting with the ability to predict both categorical and continuous targets simultaneously. Table 1 summarizes representative studies in customs fraud detection. The reviewed literature shows progress from traditional supervised models to more advanced dual-learning systems. However, existing solutions either focus only on classification accuracy or introduce computationally intensive architectures that reduce scalability. None of the prior studies integrates classification and regression within a unified, interpretable, and scalable boosting framework. Hence, this study applies the Dual-learning XGBoost-Based Approach to the customs domain. It addresses these limitations by combining efficiency, interpretability, and dual-objective optimization.

Proposed approach

Building upon our previously developed Dual-learning XGBoost-Based Approach (DXGBA)19, this study applies and adapts the model to the customs fraud detection domain. DXGBA is a unified machine learning framework designed to simultaneously perform classification and regression using a single gradient boosting model. Thus, the contribution of this work lies in demonstrating the effectiveness of DXGBA in identifying fraud while simultaneously estimating the corresponding revenue impact.

To improve the model’s performance and generalization capability, the proposed approach further incorporates two independent feature augmentation techniques, namely Tree-Based Embedding and Autoencoder-Based Augmentation. This section starts with the baseline DXGBA model, followed by its two enhancement strategies. A concise mathematical overview is included to summarize the key principles of the DXGBA model for completeness, while the full theoretical formulation and implementation details are provided in the previously developed study19.

Overview of DXGBA

The Dual-learning XGBoost-Based Approach (DXGBA) extends the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm to produce dual outputs, a continuous regression value and a binary classification label, within a single framework. Instead of developing separate models for classification and regression, DXGBA introduces a shared tree structure and a joint objective function that concurrently minimizes classification error (via binary cross-entropy) and regression error (via mean squared error). Let the dataset be defined as \(X = {\{x_i\}}_{i=1}^N\), where each instance \(x_i \in \mathbb {R}^M\) is associated with a regression target \(y_i \in \mathbb {R}\) (e.g., revenue at risk) and a classification target \(z_i \in \{0,1\}\) (fraud indicator). The model seeks to learn a non-linear mapping \(\psi : X \rightarrow (\mathbb {R}, \{0,1\})\), so that both targets are predicted simultaneously. The prediction update at boosting round k is:

where \(\theta _i = \{\tilde{y}_i, \tilde{z}_i\}\) denotes the regression and classification outputs, \(\alpha\) is the learning rate, and \(f_k\) is the k-th base learner tree with leaves \(w_j = \{w_{cls_{j}}, w_{reg_{j}}\}\).

Formally, let \(\tilde{y}_i\) and \(\tilde{z}_i\) be the predicted value and the predicted class of the ith instance, respectively. The joint objective of DXGBA is:

where \(\ell _{reg}\) is the squared error, \(\ell _{cls}\) is binary cross-entropy, \(\lambda\) is the L2 regularization parameter, \(\gamma\) penalizes tree complexity, and T is the number of leaves.

The optimization of the objective function in equation (2) relies on second-order Taylor approximation and integrates gradients g and Hessians h of both tasks in a unified loss function \(\mathcal {L}^{(k)}\). Here, the gradients \(g_{reg_i}\) and Hessians \(h_{reg_i}\) for regression are computed as follows:

whereas the gradients \(g_{cls_i}\) and Hessians \(h_{cls_i}\) for classification are defined as:

The simplified loss for a single leaf becomes:

leading to optimal weights:

where \(I_j = \{x_i \mid q(x_i) = j\}\) is the set of instances in leaf j.

The construction of the tree commences from a singular leaf, which initially encompasses all regression and classification residuals derived from the baseline predictions \(\theta _i^{(0)}\). The tree then progressively expands by identifying and incorporating the most advantageous splits that maximize the total gain G. The expansion of the weights \(w_{reg}\) and \(w_{cls}\) in equation (7) yields the simplified objective function \(\tilde{\mathcal {L}}^{(k)}\), expressed as:

Accordingly, \(\tilde{\mathcal {L}}^{(k)}\) serves as a scoring function to assess the structural integrity of the tree. Specifically, the regression similarity score \(S_{reg_{I_j}}\) and the classification similarity score \(S_{cls_{I_j}}\) are calculated for each leaf j using:

and

To ascertain the most beneficial split that maximizes the overall gain G, let \(I_L\) and \(I_R\) represent the sets of instances in the left and right nodes post-split, respectively, where \(I = I_L \cup I_R\). The gains from regression \(G_{reg}\) and classification \(G_{cls}\) are articulated as:

and

Here, \(S_{reg_I}\) and \(S_{cls_I}\) denote the regression and classification similarity scores of the parent node before the split, whereas \(S_{reg_{I_L}}, S_{reg_{I_R}}, S_{cls_{I_L}}\), and \(S_{cls_{I_R}}\) represent the similarity scores of the left and right child nodes after the split. The cumulative gain G is therefore calculated as:

The core DXGBA training process is outlined in Algorithm 1 in the Appendix.

Tree-based embedding augmentation using random forest

The DXGBA framework employs tree-based embeddings that are derived from both a random forest classifier and a random forest regressor to improve the representation of the input features. This dual-embedding approach is capable of encoding non-linear feature interactions that are applicable to both the classification and regression tasks, thereby enriching the input representation in addition to the capabilities of raw features.

Initially, a random forest classifier is trained using the classification labels from the training data, and a random forest regressor is trained using the corresponding regression targets. Each model learns a hierarchy of splits, which accurately partitions the input space based on its specific objective. For every sample, both trained forests are used to determine the leaf node indices, which are the terminal nodes each instance reaches in every tree. These indices capture high-level semantic information about the data learned by both the classifier and regressor. To make these indices compatible with numerical learning algorithms, the leaf indices from both models are one-hot encoded. They produce two high-dimensional binary vectors in which each dimension represents a possible leaf node across all trees in the respective ensemble. For instance, if each forest comprises 100 trees, each averaging 32 leaves, the encoded vector can encompass up to 3,200 dimensions. The traversal trajectories of each sample through the classifier and regressor forests are characterized by these vectors, which function as tree-based embeddings. The resulting one-hot encoded vectors from both the classifier and regressor are then concatenated with the original input features to form an augmented input matrix. Subsequently, this enhanced feature set is fed into the DXGBA architecture. The tree-based embedding integration is described in Algorithm 2 in the Appendix, and the process is illustrated in Figure 1.

By integrating raw input features with high-level tree-structured representations derived from both tasks, the model achieves a comprehensive encoding of low-level statistics and complex non-linear patterns that are relevant to both classification and regression objectives. This method offers a computationally efficient and robust mechanism for integrating the hierarchical patterns obtained from both predictive tasks, thereby improving the model’s ability to perform classification and regression in a unified boosting framework.

Although incorporating tree-based embeddings requires an extra preprocessing stage, the associated computational expense remains feasible. In this experiment, training the random forest classifier and regressor, each consisting of 100 trees, took approximately 0.16 minutes on a laptop equipped with an Apple M1 CPU and 8 GB of RAM. Once trained, the embedding extraction and one-hot encoding steps are computationally lightweight. Consequently, the overall training time of the DXGBA model with tree-based embeddings increased by roughly 28.8% compared to the baseline DXGBA without embeddings. This modest increase is justified by the possible improvement in representation and predictive accuracy.

Autoencoder-based feature fusion for simultaneous learning

In order to improve the feature representation within the DXGBA framework, we implement an autoencoder-based feature fusion strategy that integrates raw input features with non-linear representations obtained by a deep neural network. This hybrid input is subsequently employed to train a single XGBoost model that is capable of performing both classification and regression simultaneously.

Let \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times d}\) represents the original feature matrix, where n is the number of samples and d is the number of features. An autoencoder is employed to a subset of the features \(X_{AE} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times k}\) for non-linear transformation. However, the gradient boosting model preserves the remaining features \(X_{XGB} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times (d-k)}\) in their unaltered form for direct use.

The encoder sequentially compresses the selected feature subset \(X_{AE}\) using layers of fixed sizes 64, 32, and 16. Each layer is followed by the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity. The decoder reflects this structure in reverse order and the input features are reconstructed in the output layer using linear activation. The model is optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01. Training is performed for up to 50 epochs. Once trained, only the encoder part is retained to generate latent representations for all data partitions, while the decoder is discarded.

The autoencoder consists of an encoder-decoder architecture in which the encoder maps input \(X_{AE}\) into a low-dimensional latent space \(Z \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times \ell }\), with \(\ell < k\). The decoder reconstructs the input from the latent representation. The training objective \(\mathcal {L}_{AE}\) minimizes the Mean Squared Error33 (MSE) between the input and reconstruction:

Here, \(x_i\) denotes the original input sample, while \(\hat{x}_i\) represents its reconstruction generated by the decoder. Once trained, only the encoder component is retained to generate latent representations for the training, validation, and test subsets, whereas the decoder is discarded. The latent feature matrix Z is concatenated with the raw feature matrix \(X_{XGB}\) to form an enriched input representation:

The integrated feature matrix \(X^*\) is subsequently utilized as input for the DXGBA framework, which concurrently optimizes classification and regression objectives through a customized dual-loss function.

It is worth mentioning that the subset of features fed into the autoencoder is determined through an importance selection process. Specifically, XGBoost models are first trained for both classification and regression tasks. After training, feature importance scores are extracted using the gain, which measures the contribution of each feature to both predictive objectives. The two importance scores are then averaged. At the same time, the average absolute correlation of each numeric feature with all others is computed to capture redundancy and shared variance. These two measures are then combined into a single score using a weighted sum of importance and correlation. The features are ranked according to this combined score while the remaining features are directly supplied to the DXGBA component.

With this improvement, the model is capable of capturing both abstract non-linear patterns from the latent space learned by an autoencoder, along with statistical features and from the raw input space. Consequently, the ability of the model to generalize across both tasks is enhanced by the more expressive representation that results from the combined input. The autoencoder feature fusion enhancement is presented in Algorithm 3 in the Appendix, and the process is illustrated in Figure 2.

The inclusion of an autoencoder adds a short neural pretraining phase before DXGBA learning. As decsribed previously, the autoencoder architecture used in this study is intentionally lightweight. Training this model on the same laptop required approximately 1.42 minutes. After the encoder is trained and the latent representations are generated, the subsequent DXGBA training proceeds normally with a minor increase in total runtime (approximately 28.6%).

Experiments

This section presents the full experimental workflow. It starts with the dataset description and outlines the evaluation protocol and optimization settings. Then, it demonstrates the application of DXGBA to customs fraud detection, followed by a comprehensive analysis of the results.

Dataset description

In this research experiment, we evaluated the proposed approach using the customs import declarations dataset34, which consists of 54,000 synthetically generated trade records created using CTGAN while conserving correlated attributes. In fact, each row corresponds to a single goods declaration. From the 62 available fields in the import declaration form, 18 representative features were selected along with two target labels, namely “fraud” and “item price”. More specifically, 78.42% of the declarations are positive (fraudulent) cases and 21.58% are negative (non-fraudulent). As can be seen, this indicates a considerable class imbalance in the dataset. Table 2 details the attributes included in the customs dataset considered in this research.

It is worth mentioning that using synthetic data in this study was necessitated by the confidentiality and privacy restrictions surrounding real customs declarations. Disclosure of import transaction records outside customs authorities is strictly prohibited. Furthermore, access is limited only to authorized internal departments and institutions. Therefore, the publicly available synthetic dataset serves as a practical alternative. It enables research to progress despite these restrictions. The synthetic data generation process minimizes identity risk in trade statistics and maintains a distribution similar to the real data. This makes the dataset suitable as a benchmark for evaluating classification and regression algorithms.

Nevertheless, although CTGAN effectively maintains the statistical dependencies among features, it cannot fully reflect the data complexity, irregularities, and noise patterns present in real-world customs transactions. As a result, the generalization of the reported results may be constrained. In other words, differences between synthetic and real-world customs data could influence model performance when applied in reality. Future research will therefore focus on validating the proposed approach using real customs datasets once access permissions are obtained.

Experimental setup and hyperparameter tuning

Hyperparameter selection was carried out in a preliminary stage using an empirical grid-search procedure on the training data. The grid search explored several settings for XGBoost parameters, including depth, learning rate, and regularization terms. The ideal configuration that achieved a balance between classification and regression performance was employed in the remaining experiments.

After fixing the hyperparameters, the evaluation was performed using 5-fold cross-validation to ensure robust and reliable estimates of performance. The dataset was divided into five folds using K-fold splitting. In each iteration, one fold held out as the unseen test fold and the remaining four folds constituted a development set. Within this development set, an additional internal split was performed to obtain a training subset (\(\approx 60\%\)) and a validation subset (\(\approx 20\%\)). The model was trained on the training subset, and early stopping was monitored on the validation subset to prevent overfitting. The test fold for each iteration was used exclusively for performance evaluation, and the final results reported in the tables are obtained only by averaging the classification and regression metrics across the five test folds.

To conduct a comprehensive assessment of the proposed framework, hyperparameters were optimized using both validation-guided manual tuning and metaheuristic exploration via the Modified Sinh-Cosh Optimizer (MSCHO)35. Both methods produced competitive performance. However, manually tuned DXGBA showed marginal superiority, especially for the classification task. Thus, it is used as the optimal configuration in this study. On the other hand, MSCHO delivered closely comparable results and demonstrated strong adaptability when manual tuning expertise is limited.

The final configuration used in this study reflects the optimal setting selected, which provides a reliable estimate of model generalization. In particular, various values were explored for the learning rate. Specifically, it was set to 0.001, 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, and 0.1, respectively. Consequently, a learning rate of 0.1 was used in these subsequent experiments. Moreover, different values, specifically 8, 16, 32, and 64, were considered to set the maximum tree depth. Accordingly, the maximum depth was selected to be 16. Furthermore, we varied the subsampling rate and set it respectively to 0.6, 0.8, and 1. Thus, a sampling rate of 0.8 was set for these experiments. The L1 regularization parameter was tested at values of 0, 0.5, 1.3, and 5, where 0.5 achieved the highest performance. Moreover, the L2 regularization coefficient (\(\lambda\)) was evaluated at 0, 0.5, 1.3, and 5, with 0.5 yielding the best performance. Similarly, the gamma parameter (\(\gamma\)) was tested at 0, 0.5, 2, and 5, and the optimal value was found to be 1. Note that a feature scaling, namely Min-Max Normalization, was applied. Moreover, categorical variables were transformed using label encoding. The classification performance was assessed using a variety of metrics. In particular, the accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score36, and Area Under the Curve (AUC)37 were computed based on the obtained confusion matrix. Additionally, regression performance is evaluated using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE).

DXGBA builds on XGBoost, which incorporates several regularization techniques to reduce overfitting in both the classification and regression branches: (i) weight penalties including L1 and L2 regularization on leaf scores; (ii) tree growth controls including maximum tree depth, minimum instance weight in a child, and the split threshold penalty \(\gamma\) to discourage complex splits; and (iii) stochastic regularization through row and feature subsampling. We also used early stopping on a validation split within each fold to stop boosting when no further generalizable improvement is observed. These mechanisms constrain model complexity and improve robustness.

Furthermore, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE)28 was deployed in this study due to the inherent class imbalance within the dataset. SMOTE generates instances based on their closest neighbors from the minority classes. Similarly, a Random Undersampling (RU)38 of the majority class was conducted. Although SMOTE was applied to address class imbalance, special precautions were implemented to reduce the potential risk of overfitting arising from oversampling and multi-task learning. A 5-fold cross-validation technique was adopted to ensure fair evaluation across different unseen test data splits. Furthermore, regularization techniques and early stopping were used to avoid overfitting. The SMOTE rate was also low to maintain actual data distributions. These measures altogether ensured that the proposed DXGBA model remained robust and maintained generalization.

Application to customs fraud detection

To adapt DXGBA to the customs domain, the model was trained on a dataset of import declarations, where the classification target indicates whether a declaration is fraudulent, and the regression target quantifies the estimated revenue loss amount. In addition to prediction, DXGBA ranks the declarations by their predicted fraud risk. This ranking enables authorities to prioritize inspections and maximize revenue recovery under limited resources. More specifically, declarations are ranked by their predicted revenue at risk among those classified as fraudulent. For each validation fold, the top n% of these declarations are selected for audit simulation. The revenue capture rate is computed as the proportion of total fraudulent revenue recovered within the top n%. It is then averaged across folds to assess effectiveness at various resource constraints. As mentioned earlier, SMOTE is applied to generate new samples of the minority (fraudulent) class by interpolating between existing minority class instances. This is followed by random undersampling of the majority class to further balance the class distribution. Together, these techniques help the model better learn fraud patterns without being overwhelmed by the dominant class. Figure 3 presents the full workflow of the proposed DXGBA model.

Although the proposed DXGBA framework demonstrates high performance for customs fraud detection, a number of ethical and practical issues must be acknowledged. False positives, where legitimate traders are incorrectly identified as fraudulent, can lead to unnecessary inspections, delays in goods clearance, and potential reputational or financial harm. Thus, it may be more advantageous to employ it first as a decision-support tool rather than independent systems. This practice will ensure that final actions remain subject to expert review and process. From a deployment perspective, customs authorities must also consider issues of data privacy, transparency, and model interpretability, especially when handling sensitive trade information39. To integrate machine learning systems with existing customs operations, it is necessary to ensure that workers are adequately trained, data channels are reliable, and international trade and data protection rules are followed39. Addressing these challenges is important to ensure that the use of AI fraud detection systems is ethical and sustainable.

Results and discussion

In contrast to traditional single-task ML approaches that require the models to be trained separately for the intended prediction task (either classification or regression), the proposed DXGBA model is trained to predict both (i) A continuous value and (ii) A binary class label within a unified framework. Consistently, we first evaluated the performance of the proposed simultaneous classification and regression model, DXGBA, and compared it with the results obtained using conventional XGBoost24 models trained separately for regression and classification tasks. Moreover, we investigated the performance of both models after deploying SMOTE with different resampling percentages, specifically 10%, 15%, 30%, 50% and balanced resampling, in addition to the hybrid SMOTE with RU. The results reported in Table 3 show that the DXGBA model consistently surpasses the XGBoost model in both classification and regression tasks across all SMOTE and RU scenarios. This showcases DXGBA’s stability and robustness across different data augmentation techniques and settings. On the other hand, XGBoost proved to be more sensitive to SMOTE changes and yielded higher results variance compared to DXGBA.

As one can notice, DXGBA consistently outperformed XGBoost across all tested data distributions and across both the classification and regression tasks. In most settings, DXGBA achieved higher accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC compared to XGBoost. Moreover, DXGBA yielded slightly higher recall even without SMOTE. It demonstrates its ability to cope with imbalanced data. This advantage becomes more evident as the dataset exhibits higher imbalance levels. DXGBA also ensured a more balanced classification outcome by achieving a better trade-off between precision and recall, which is illustrated by the improved F1-scores.

For the regression task, DXGBA yielded lower MAE and MSE values than XGBoost in every experiment. This indicates that DXGBA sustained a lower regression error and, at the same time, improved the performance of classification. These findings demonstrate the capability of the proposed dual-learning approach to mitigate the challenges associated with both tasks. In other words, DXGBA optimizes the utilization of the relevant features by jointly evaluating their influence on classification and regression. For example, features with weak relevance to the regression target may still be informative for classification. The proposed objective function captures this relationship through the inclusion of gradients and Hessians representing both objectives.

The results also provide insights into the effect of resampling strategies. SMOTE increased recall but reduced precision. This might be attributed to the generated synthetic minority-class samples that increased the overlap between classes. Accuracy experienced a minor decline at higher SMOTE rates due to potential overfitting to synthetic samples, whereas regression metrics remained predominantly stable. Among the tested SMOTE percentages, resampling by 10% produced the best balance between precision and recall.

The combination of RU and SMOTE further improved the recall as it significantly reduced class imbalance. Nonetheless, this enhancement was associated with reductions in accuracy and precision. This reduction resulted from the elimination of informative samples from the majority class. RU also introduced additional variance due to its random selection mechanism. Hence, integrating SMOTE with RU improves recall. However, it results in a reduction of precision and AUC compared to using SMOTE alone. Conversely, the maximum precision and AUC were attained when no resampling was applied.

In customs fraud detection, false negatives incur considerable operational risk, as undetected fraudulent shipments may lead to financial losses or security breaches. However, maximizing recall alone (as in the RU-only configuration) produces a substantial increase in false positives, resulting in excessive and impractical inspection loads. To balance detection sensitivity with operational feasibility, we adopted the F1-Score as the primary model selection criterion. As shown in Table 3, the 10% SMOTE + RU configuration yielded the highest F1-Score (0.4923), representing the most effective trade-off between precision and recall. Consequently, this configuration was selected for all subsequent experiments and model comparisons.

After identifying 10% SMOTE with RU as the optimal data distribution setting, all experiments were performed exclusively on the same balanced dataset. A single comprehensive experiment was conducted to compare DXGBA, conventional single-task learning methods, and recent multi-task learning frameworks. Table 4 summarizes the results across the classification and regression tasks.

We assess the performance of XGBoost models in tackling the classification and regression tasks. The purpose of this experiment was to evaluate XGBoost’s performance against the results achieved using conventional machine learning approaches employed for regression and classification problems. Namely, Support Vector Machines22, Neural Networks21, logistic regression20, and linear regression were considered in this experiment. Among the single-task models, XGBoost achieved the strongest overall performance. It recorded an accuracy of 71.75%, precision of 0.4007, recall of 0.6225, F1-score of 0.4875, and AUC of 0.7592. For the regression task, XGBoost achieved an MAE of 0.000748 and a MSE of 0.000053. These findings highlight the capability of XGBoost to effectively model non-linear patterns in the customs dataset and achieve accurate predictions. Logistic regression, neural networks, and SVM yielded substantially lower classification performance, with no model surpassing the accuracy of XGBoost. For regression, linear regression reported a MAE of 0.000681, which is numerically close to that of XGBoost, but its MSE remained higher.

We extended the experiment and compared the proposed approach to recent multi-task learning frameworks, namely Cross-stitch Networks40. A Cross-Stitch architecture is evaluated with two parallel Multilayer perceptron (MLP) towers, one per task. After the first hidden layer, a learnable mixing unit combines information between the two towers so each task can borrow useful features from the other. The Cross-Stitch Network achieved a recall of 0.5964, but only 0.2378 in precision. This has led to an accuracy of 49.98% and an F1-score of 0.3386. Such findings indicate that while the mixing mechanism enabled the sharing of task-relevant information between towers, the model showed limitations in maintaining precision in fraud detection.

Furthermore, we assess the performance of the proposed DXGBA and compare it with the results achieved using the relevant state-of-the-art methods that also perform simultaneous classification and regression. It is important to mention that the related works enclose a variety of architectures and techniques. Namely, we investigated the performance of DualTaskNet4, Joint RRN Framework41, Aux-LSTM422, and DATE1. As can be seen, these multi-task models showed similar trade-offs. Aux-LSTM422 delivered a high recall of 0.7233. However, the very low precision produced a weak F1-score and low accuracy. The DATE1 framework ranked second among the multi-task baselines. It achieved an accuracy of 56.47%, an F1-score of 0.4528, and an AUC of 0.7558. Nevertheless, its regression errors remained higher than those of DXGBA.

As can be seen, DXGBA showed the highest overall performance across most evaluation metrics. It demonstrates higher performance in most evaluation metrics. It achieved an accuracy of 71.9%, precision of 0.4039, recall of 0.6305, F1-score of 0.4923, and AUC of 0.7638. For the regression task, DXGBA achieved the second lowest MAE of 0.000691 and the lowest MSE of 0.000049. Although the difference between the MAE of DXGBA and linear regression is small, DXGBA exhibited the most consistent combination of low MAE and low MSE across the dataset. These results show that the proposed model generally outperformed both single-task methods and state-of-the-art multi-task frameworks on the optimized dataset. The improved performance is likely due to the dual-learning mechanism of DXGBA. Such learning allows both tasks to reinforce one another and benefit from the feature-learning power of gradient boosting. Furthermore, it enables DXGBA to maintain high discrimination ability in fraud detection while delivering stable regression performance.

To assess generalization, the model’s performance was reported as the average of the metrics across the five test folds rather than from a single test split. This procedure reduces bias and provides a more reliable estimate of the model’s true performance. In addition, class balancing techniques were applied only to the training portion within each fold. As illustrated in Figure 4, the training and validation learning curves decrease in parallel during the first boosting rounds and then stabilize at similar values without divergence. The validation curve plateaus at approximately the same iteration and remains consistently close to the training curve. This repeated pattern in all folds provides visual evidence that DXGBA converges stably and does not exhibit large overfitting. Hence, it confirms its ability to generalize well to unseen customs declarations.

The inclusion of dual-objective optimization in DXGBA introduces additional layers of complexity that may obscure the direct relationship between inputs and outputs. However, this complexity arises from a core strength of the framework. DXGBA can estimate the probability of fraud and the associated revenue at risk at the same time. To ensure that this increased modeling capacity does not come at the cost of transparency, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)43 analysis was conducted. It quantifies both global and instance-level feature contributions for the classification and regression components. These tools enable the generation of visualizations that are easy to interpret. Furthermore, they aid in understanding the influence of the features on the predicted probability of fraud and the predicted revenue at risk. Even within the scenario of multi-task learning, the interpretability analysis assures that the decision-making procedure of DXGBA remains trustworthy and transparent.

To improve transparency and satisfy the explainability requirements of customs authorities, we incorporated SHAP43 to interpret the dual-task outputs of DXGBA. SHAP values were computed using a PermutationExplainer for both the fraud classification head and the revenue estimation head across the 5 cross-validation folds.

The SHAP summary plots in Figure 5 present the global interpretability of the DXGBA by highlighting the most influential features for each task. The dominant contributors to fraud classification were Tax Rate, Net Mass, and HS6 Code, which aligned with the customs risk indicators. For revenue estimation, the most significant positive impact was demonstrated by similar features, specifically Net Mass and HS6 Code. This suggests that the model captures structurally meaningful patterns shared by both tasks.

To further demonstrate local interpretability at the transaction level, we analyzed the highest revenue fraud case within each fold. Figure 6 shows the SHAP contributions for a representative example. Positive SHAP values indicate features that increase both the probability of fraud and the revenue estimate. HS6 Code, Country of Departure, and Tax Type were major positive contributors to the fraud probability. On the other hand, Country of Departure, HS6 Code played the largest role in the revenue prediction. These explanations demonstrate that the model’s decisions rely on meaningful trade patterns. It concludes that DXGBA delivers interpretable decision-making logic for both fraud identification and revenue-at-risk assessment. Accordingly, it confirms its practical application in customs operations.

As stated earlier, the objective of this research is two-fold: (i) Deploy DXGBA as a dual task ML model for customs fraud detection through the classification of customs declarations as fraudulent or non-fraudulent and the prediction of the corresponding revenue at risk as the outcome of the regression task. (ii) Prioritize customs inspection effort based on the classification and regression outcomes obtained using DXGBA. In other words, the designed approach categorizes customs declarations into “fraudulent” and “non-fraudulent” classes, which denote the positive and negative classes, respectively. Moreover, it identifies which cases assigned to the positive class should be prioritized for inspection by the customs administration. Note that the prioritization of these positive cases is performed according to their revenue value predicted by the learned model. Thus, DXGBA can categorize and prioritize the fraudulent instances that significantly increase the overall customs revenue upon detection.

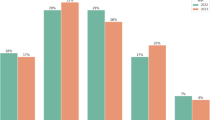

An appropriate inspection rate differs based on the strategy and regulations of customs administrations. Considering that customs administration can audit a limited number of shipments, four inspection rates were investigated in this experiment. Specifically, 2%, 5%, 10%, and 20% were used to evaluate model performance. Note that the Revenue@n% metric was considered as a performance measure. In fact, Revenue@n% represents the total revenue collected from the top n% positive transactions identified by the model over the total revenue expected from all transactions. In other words, it reflects the customs revenue derived from the top n% transactions relative to the total revenue collected if all transactions were audited. One should note that the term “top n%” denotes the riskiest transactions detected by the model. All revenue-recovery results in this experiment were obtained using the DXGBA model trained on the dataset balanced with SMOTE at 10% combined with Random Undersampling.

Table 5 shows the percentage of gained revenue with respect to the auditing rate. As can be seen, inspecting a small quantity of the customs declarations yields a substantial portion of the revenue generated. More specifically, auditing just 5% of the fraudulent cases generates approximately 65.22% of the total revenue. Moreover, inspecting 20% of fraudulent transactions yields 92.80% of the total revenue. Upon predicting the classification confidence of fraudulent cases along with their associated revenue, DXGBA allows customs to prioritize inspections accordingly. This means that customs operations should focus on the positive transactions that are the most profitable in terms of revenue at risk.

Accordingly, Figure 7 reports the customs duties that can be generated from the top n% transactions. As can be noticed, the revenue rises quickly when the auditing rate reaches about 10%. This drastic increase indicates that a small proportion of transactions contributes significantly to collecting most of the customs duties. Beyond the 10% auditing rate, the increase in revenue becomes more gradual and steadier. In other words, additional inspection efforts result in smaller increments in revenue. For instance, increasing the inspection rate from 10% to 20% of the transactions boosts the revenue by about 4.82%. Additionally, the generated revenue flattens significantly as the auditing rate increases, which indicates decreasing returns from the additional auditing efforts. Thus, it would be more efficient to focus auditing efforts on this proportion of transactions, as it maximizes the revenue while minimizing the effort and resources. For instance, inspecting 2% of transactions yields 44.07% of the total revenue, and this rate jumps to 88.63% when inspecting 10%.

In summary, focusing on a smaller subset of transactions can enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of customs fraud detection efforts. In other words, the resources allocated by the customs authorities can be optimized by prioritizing the inspection of the top 10% to 20% transactions. More specifically, concentrating the efforts on the top 20% transactions could be considered optimal, as it generates more than 93% of the total revenue.

To further examine the individual contribution of the proposed enhancement mechanisms, an exploratory analysis was conducted using the SMOTE 10% with RU configuration. It serves as a diagnostic analysis of how each enhancement affects the model rather than a final model selection process. As shown in Table 6, the baseline DXGBA model achieved a balanced trade-off between precision and recall. It yields an F1-score of 0.4923 and an AUC of 0.7638. Moreover, it achieves a low regression error with an MAE of 0.0007 and MSE of 0.000049. Incorporating classifier embeddings did not make performance gains. This could be due to the sensitivity to the synthetically increased minority class. The model reached a recall of 0.8473 with low precision, leading to an F1-score of 0.4383. Regressor embeddings slightly improved the regression objective with an MSE of 0.000048. However, the overall classification performance is reduced with an F1-score of 0.4801. Joint embeddings produced similar behavior. It increases recall to 0.8545 and maintains an F1-score of 0.4405. The hybrid model, which integrates a neural network autoencoder, showed the highest accuracy of 76.37%. Nevertheless, it exhibited low precision and F1-score.

Conclusion

This study addressed the problem of customs fraud detection by applying a dual-learning gradient boosting framework. Such a framework is capable of generating a binary fraud risk decision and a continuous revenue-at-risk estimate within a single predictive model. It offers a reliable decision-support mechanism for customs inspection. Unlike traditional single-task machine learning methods, DXGBA jointly optimizes both objectives. It benefits from the shared information between them to improve the overall predictive performance. The experimental analysis revealed that DXGBA maintained competitive performance even when trained on the original imbalanced dataset. Nevertheless, a comprehensive analysis of various data resampling techniques revealed that employing SMOTE at 10% in conjunction with Random Undersampling provides the optimal balance between precision and recall. Under this configuration, the baseline DXGBA was compared against both conventional single-task learning models and recent multi-task learning architectures. Across the comprehensive comparison, DXGBA achieved the strongest overall performance. It consistently maintains a high fraud detection capability and delivers stable and low regression error. This confirms that the interaction between the classification and regression objectives achieves a mutual advantage. Furthermore, DXGBA exhibited an ability to recover 87.98% of potential revenue by auditing only 10% of the import declarations. This level of efficiency is critical for customs administrations that deal with large numbers of transactions. It helps them to find inspection resources and prevent revenue leakage through fraud without disrupting the flow of legitimate trade. An exploratory enhancement analysis showed that some variants improved individual objectives, but none consistently outperformed the baseline DXGBA.

Despite these promising results, the study has some limitations. First, the experiments were performed on artificially generated customs data due to limitations in accessing operational trade records. Although CTGAN guarantees realistic data distributions, real-world deployment may require further complexities. Second, although tree-based models are relatively more interpretable than deep learning networks, the complexity of the DXGBA framework, especially due to dual-objective optimization, reduces its transparency. Third, although the proposed DXGBA framework demonstrates high performance for customs fraud detection, some ethical and practical issues may arise. These considerations highlight future research directions. The next step is to validate DXGBA on real customs datasets as they become available. Another extension is integrating interpretability frameworks and decision systems to strengthen user trust and facilitate adoption.

Data availability

The Customs Declaration Dataset used in this study is publicly available. The dataset was originally released by Seondong et al. and can be accessed from the GitHub repository: https://github.com/Seondong/Customs-Declaration-Datasets. Additional details about the dataset are described in the corresponding publication (arXiv:2208.02484). For access to any additional materials related to this study, please contact the corresponding author, Rawabi Alwanin.

References

Kim, S. et al. Date: Dual attentive tree-aware embedding for customs fraud detection. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2880–2890, https://doi.org/10.1145/3394486.3403339 (ACM, 2020).

Novith, D. C., Sembiring, A. R. & Ridho, M. H. Customs fraud detection using extremely boosted neural network (xbnet). Jurnal BPPK: Badan Pendidikan dan Pelatihan Keuangan 16, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.48108/jurnalbppk.v16i1.816 (2023).

Kunickaite, R., Brazinskaite, A., Saltis, I. & Krilavicius, T. Machine learning approaches for customs fraud detection. In IVUS, 54–63 (2021).

Ismail, M. M. B. & AlSadhan, N. Simultaneous classification and regression for zakat under-reporting detection. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13095244 (2023).

Ojala, L. et al. Connecting to compete 2018: Trade logistics in the global economy (Tech. Rep, World Bank, 2018).

Uyar, A., Nimer, K., Kuzey, C., Shahbaz, M. & Schneider, F. Can e-government initiatives alleviate tax evasion? the moderation effect of ict. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 166, 120597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120597 (2021).

Dias, A., Pinto, C., Batista, J. & Neves, E. Signaling tax evasion, financial ratios and cluster analysis (2016).

Wu, R.-S., Ou, C., ying Lin, H., Chang, S.-I. & Yen, D. C. Using data mining technique to enhance tax evasion detection performance. Expert Systems with Applications 39, 8769–8777, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.01.204 (2012).

Mikuriya, K. & Cantens, T. If algorithms dream of customs, do customs officials dream of algorithms? a manifesto for data mobilisation in customs. World Customs Journal 14, 3–22 (2020).

Butgereit, L. Anti money laundering: Rule-based methods to identify funnel accounts. In Conference on Information Communications Technology and Society (ICTAS), 21–26, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTAS50802.2021.9394990 (IEEE, 2021).

Pozzolo, A. D., Boracchi, G., Caelen, O., Alippi, C. & Bontempi, G. Credit card fraud detection: A realistic modeling and a novel learning strategy. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 29, 3784–3797. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2017.2736643 (2018).

Kültür, Y. & Çağlayan, M. U. Hybrid approaches for detecting credit card fraud. Expert Systems 34, https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.12191 (2017).

World customs organization.

Chermiti, B. Establishing risk and targeting profiles using data mining: Decision trees. World Customs Journal 13, 39–58 (2019).

Grigoriou, C. Revenue maximisation versus trade facilitation: The contribution of automated risk. World Customs Journal 13, 77–90 (2019).

Zhou, X. Data mining in customs risk detection with cost-sensitive classification. World Customs Journal 13, 115–130 (2019).

Vanhoeyveld, J., Martens, D. & Peeters, B. Customs fraud detection. Pattern Analysis and Applications 23, 1457–1477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10044-019-00852-w (2020).

Seck, D. A. N. Building machine learning models for fraud detection in customs declarations in senegal. WSEAS TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SCIENCE AND APPLICATIONS 21, 208–215. https://doi.org/10.37394/23209.2024.21.20 (2024).

Alwanin, R., Bchir, O. & Ismail, M. M. B. Gradient boosting based simultaneous classification and regression approach. IEEE Access (2025).

Hosmer, D. W. & Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression (Wiley, 2000), 2 edn.

Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychological Review 65, 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042519 (1958).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 20, 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994018 (1995).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, 278–282, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.1995.598994 (IEEE Comput. Soc. Press).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, vol. 13-17-August-2016, 785–794, https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2016).

Canrakerta, Hidayanto, A. N. & Ruldeviyani, Y. Application of business intelligence for customs declaration: A case study in indonesia. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1444, 012028, (2020)https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1444/1/012028.

Regmi, R. H. & Timalsina, A. K. Risk management in customs using deep neural network. In 2018 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security (ICCCS), 133–137, https://doi.org/10.1109/CCCS.2018.8586834 (IEEE, 2018).

Sa’adah, S. A. & Hartanto, A. Fraud detection using data analytics: A case study of under invoicing importation fraud in indonesia. Jurnal BPPK: Badan Pendidikan dan Pelatihan Keuangan 16, 146–153, https://doi.org/10.48108/jurnalbppk.v16i1.823 (2023).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. Smote: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 16, 321–357. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.953 (2002).

de Roux, D., Perez, B., Moreno, A., del Pilar Villamil, M. & Figueroa, C. Tax fraud detection for under-reporting declarations using an unsupervised machine learning approach. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 215–222, https://doi.org/10.1145/3219819.3219878 (ACM, 2018).

Alqaryouti, O., Siyam, N., Shaalan, K. & Alhosban, F. Customs valuation assessment using cluster-based approach. International Journal of Information Technology 16, 4243–4252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41870-024-01821-1 (2024).

Jiang, S., Dong, R., Wang, J. & Xia, M. Credit card fraud detection based on unsupervised attentional anomaly detection network. Systems 11, 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11060305 (2023).

Oosterman, D. T., Langenkamp, W. H. & van Bergen, E. L. Customs Risk Assessment Based on Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Using Autoencoders, 668–681 (2022).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (Springer, 2009).

Jeong, C., Kim, S., Park, J. & Choi, Y. Customs import declaration datasets. arXiv:2208.02484 (2022).

Cincovic, J., Jovanovic, L., Nikolic, B. & Bacanin, N. Neurodegenerative condition detection using modified metaheuristic for attention based recurrent neural networks and extreme gradient boosting tuning. IEEE Access 12, 26719–26734. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3367588 (2024).

Rijsbergen, V. Information Retrieval (Butterworths, 1979), 2nd edn.

Green, D. M. & Swets, J. A. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics (Wiley, 1966).

He, H. & Garcia, E. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 21, 1263–1284. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2008.239 (2009).

Cheong, B. C. Transparency and accountability in ai systems: safeguarding wellbeing in the age of algorithmic decision-making. Frontiers in Human Dynamics 6, 1421273 (2024).

Misra, I., Shrivastava, A., Gupta, A. & Hebert, M. Cross-stitch networks for multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3994–4003 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Online human action detection using joint classification-regression recurrent neural networks, 203–220 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Ott, F., Rugamer, D., Heublein, L., Bischl, B. & Mutschler, C. Joint classification and trajectory regression of online handwriting using a multi-task learning approach. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 1244–1254, https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV51458.2022.00131 (IEEE, 2022).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thankOngoing Research Funding Program, (ORFFT-2025-150-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A., M.M.B.I. and O.B. conceived the study and designed the methodology; R.A. implemented the software and curated the data; R.A., M.M.B.I. and O.B. validated the approach and performed the formal analysis and investigation; R.A., M.M.B.I. and O.B. provided resources and prepared the visualizations; R.A. wrote the original draft; R.A., M.M.B.I. and O.B. reviewed and edited the manuscript; O.B. and M.M.B.I. supervised the work. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Accession codes

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

For completeness, this appendix reports the detailed pseudocode underlying the methodology adopted in this study. The main text provides a conceptual overview, whereas the operational instructions necessary for implementation are documented here. Specifically, the appendix contains the full procedures for (i) the Model Building Algorithm (DXGBA), (ii) the Tree-Based Embedding Augmentation Algorithm, and (iii) the Autoencoder Feature Fusion Algorithm, which together constitute the complete learning framework evaluated in the experiments.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alwanin, R., Ismail, M.M.B. & Bchir, O. Customs fraud detection using a gradient boosting approach for joint classification and risk estimation. Sci Rep 16, 3432 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33382-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33382-z