Abstract

To evaluate the factors influencing the teaching effectiveness of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course, a probabilistic linguistic term set-based evaluation method is proposed. Firstly, evaluation indicators are constructed based on semantics. To ensure the objectivity of weight allocation, the DEMATEL (Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) method is used to calculate the weights of these indicators. Secondly, the probabilistic linguistic term set (PLTS) is combined with the possibility degree formula to construct a probabilistic linguistic possibility degree evaluation matrix. This matrix comprehensively reflects the “expectation” and “variance” characteristics of two PLTS. Finally, the linguistic evaluation information of the candidate sets is compared using the probabilistic linguistic possibility degree evaluation matrix, and a comprehensive possibility degree matrix is calculated and ranked. Various experimental results validate the stability and effectiveness of the proposed method in evaluating the factors influencing the teaching effectiveness of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course and its applicability in enhancing teaching effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The course “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” is one of the fundamental courses crucial for agricultural laboratory safety, playing a positive role in enhancing safety standards in agricultural laboratories. The focus of this study is to evaluate the factors influencing the teaching effectiveness of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course, thereby improving teaching quality and strengthening laboratory safety.

MCDM (Multiple Criteria Decision Making) methods include AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process), TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution), VIKOR (Multi-Criteria Optimization and Compromise Solution), etc1,2,3. , and there have been many studies on their application in various decision-making problems. The core idea of the AHP method is to break down complex decision-making problems into levels such as objectives, criteria, and alternatives4. It determines the relative importance of each factor through pairwise comparisons and uses mathematical methods to calculate their weights, thereby providing a basis for the selection of the best alternative. he interval-valued circular intuitionistic fuzzy set-based AHP provides a structured framework for evaluating innovative teaching approaches5. An improved AHP method is applied to optimize the teaching and delivery of PE Physical Education programs6. A curriculum evaluation system based on AHP and clustering is used to evaluate the performance of the English hybrid teaching courses7.There are also some studies on the application of the TOPSIS method in teaching. An enhanced TOPSIS is utilized to analyse the teaching evaluation in a fuzzy environment8.The TOPSIS combined with fuzzy analytic network process is proposed to analyse the dimensions, indicators and alternatives of blended design teaching service quality9.The improved TOPSIS method is proposed to assess the knowledge share quality10.A TOPSIS method with N-valued neutrosophic trapezoidal numbers is proposed to MCDM problems11.Some related studies on the VIKOR method are as follows: the VIKOR combined with type-2 neutrosophic number is used to assist decision-makers in making the most informed choice12. A VIKOR method based on the entropy measure is developed to solve the problem of MCDM13. The VIKOR is integrated with AHP to analyse the most pertinent renewable energy sources for electricity generation in developing countries14. Additionally, several improved approaches have been proposed, including modifications to various decision-making methods using trapezoidal fuzzy multi-numbers15,16,17,18, grey relational theory18, interval type-2 fuzzy sets19,20, and regret theory21. However, when these methods are applied to the evaluation of teaching effectiveness for courses such as “Laboratory Safety Admission Education”, two key limitations remain: the lack of consideration for complex interrelationships among indicators and insufficient handling of uncertainties inherent in linguistic evaluations.

In terms of the complex interrelationships among factors, since the influencing factors of teaching effectiveness are not isolated but rather have complex mutual connections, the core idea of the AHP method is that the criteria are independent of each other, and its hierarchical structure cannot describe this network-like causal relationship. The TOPSIS and VIKOR methods also assume that the indicators are orthogonal and independent in their calculations. If there are strong correlations among the factors, the ranking will be distorted due to the repeated calculation of information based on weighted distances or compromise solutions. To overcome these problems, based on the effectiveness of the DEMATEL19 method in analysing the mutual influence relationships among factors in complex systems20, this study introduces DEMATEL to determine the weights of the influencing factors of teaching effectiveness. Unlike AHP, which is based solely on importance comparisons, DEMATEL quantifies the direct influence intensity among factors through expert judgment, and then calculates the cause degree and centrality of each factor. Factors with high centrality are in a pivotal position in the entire influence network, while those with high cause degree are the fundamental sources driving system changes. Therefore, in the evaluation of the teaching effectiveness of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course, using DEMATEL to determine the weights can objectively reflect the actual mutual promotion or restriction relationships among the influencing factors of teaching effectiveness, laying a foundation for subsequent precise evaluations.

After determining the interrelationship structure and weights of the influencing factors of teaching effectiveness through the DEMATEL method, another challenge in the evaluation of teaching effectiveness is how to precisely handle the inherent uncertainty and fuzziness of the semantic evaluation information from different evaluators. Although there have been improved studies such as fuzzy AHP or fuzzy TOPSIS, the requirement of AHP for precise scale in pairwise comparisons and the dependence of TOPSIS/VIKOR on precise numerical performance matrices make it difficult to handle the evaluation information characterized by possibility language term sets, which simultaneously contain preference probability distributions and the fuzziness of language terms, without information loss. Linguistic terms or direct fuzzy sets can mathematize qualitative language concepts, enabling knowledge based on experience and intuition to be formally expressed, reasoned, and calculated, thus building a bridge between human subjective and fuzzy cognition and the precise computation of machines. The theory of fuzzy sets has been studied in many aspects. For instance, q-Rung Orthopair Fuzzy Set21, Fuzzy CoCoSo with Bonferroni methods22, Fuzzy Best Worst Method Approach23, Random Forest Algorithm with fuzzy sets24. According to the characteristics of fuzzy decision-making theory, to address this issue, this study further introduces PLTS as the carrier of semantic evaluation information25. PLTS allows each language term to be associated with a probability, thereby enabling the lossless encapsulation of group language evaluation opinions with distribution characteristics. Since its proposal, PLTS has been used in many aspects for research, such as, PLTS is integrated with other two methods to maximize customer satisfaction26. PLTS combined with the Best-worst method is applied to the location selection of offshore wind power station27. An improved PLTS is used to establish a hotel evaluation model to process the hotel information28. The PLTS is connected with discrete probability distribution to assess the practical atmospheric pollutant evaluation problem29. PLTS and its variants are utilized in online production ranking30, air quality index31, hotel recommendation32, tourism attraction selection33, and PLTS also has research in the field of teaching, the multi-granularity PLTS is used to improve the teaching quality34, an extended PLTS is employed to promote the teaching reform of big data technology and application courses in the new liberal arts construction scenario35. While PLTS excels at fully preserving and leveraging the probability distribution information embedded in expert group evaluations, it falls short in capturing the deviations of results during outcome comparisons.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we proposed a hybrid evaluation framework that systematically integrates the DEMATEL method, PLTS and a modified possibility degree method, aiming to tackle the dual complexity inherent in teaching effectiveness evaluation. Specifically, DEMATEL is employed to unpack and quantify the complex causal network structure among factors influencing teaching effectiveness, thereby deriving objective weights. PLTS serves to encapsulate the fuzziness associated with probabilistic distributions in expert group semantic evaluations. A pivotal advancement lies in the introduction of a modified possibility degree method: this formula not only computes the overall preference possibility between two PLTS but also simultaneously captures discrepancies in both the mean and variance of the compared pairs. This enhancement enables the model to effectively differentiate between evaluation outcomes with comparable expected values yet substantial divergences in expert opinions, thereby capturing risk and divergence information that traditional methods tend to overlook.

When evaluating the teaching effectiveness of courses such as “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories”, there are problems such as the lack of complex correlations among indicators and the insufficient handling of the uncertainty in language evaluation, as well as the insufficiency of PLTS in result comparison. This study constructs a two-stage hybrid evaluation framework: in the first stage, DEMATEL is used to analyse the correlation network among factors to obtain the objective weights reflecting the system structure; in the second stage, the probability linguistic term set is combined with the improved possibility degree formula mentioned above to construct a probability linguistic possibility degree evaluation matrix for effective comparison and ranking of PLTS. This framework combines the advantages of DEMATEL in analysing the correlation of system structure with the advantages of probability linguistic methods and possibility degree theory in handling the uncertainty of semantic information, making the evaluation results more scientific.

Except for the first Sect. Introduction Introduction, the remainder of the article is structured as follows: The second section is Model Construction, encompassing 2.1 Evaluation Indicators and 2.2 Indicator Weight Calculation via the DEMATEL Method. The third section, Probabilistic Linguistic Term Sets and Possibility Degree, includes two subsections: Sects. Construction of probabilistic linguistic term sets and possibility degree and Probabilistic linguistic possibility degree-based teaching evaluation process. The fourth section, Teaching Effectiveness Evaluation and Validation, comprises Sects. Validation of teaching effectiveness, Robustness test, Reliability analysis of expert evaluations, Bootstrap-based confidence interval estimation, Comparative analysis of methods, and Summary. The last section is Conclusions.

Model construction

Evaluation indicators

The teaching of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course typically involves instructors delivering lectures followed by routine safety exams, with assessment scores provided as the evaluation method. The course teaching evaluation indicators are divided into five categories: teaching contents, teaching methods, professional distinction, teaching quality assessment methods, security knowledge acquired, and classroom atmosphere. The descriptions of each indicator are as follows:

-

1.

Teaching contents (TC) The richness and novelty of the teaching content directly determine the teaching effectiveness and student engagement in the classroom36,37.

-

2.

Teaching methods (TM) The rise of teaching approaches such as “online + offline” and “in-class + extracurricular,” along with the application of teaching platforms like MOOC and Rain Classroom, provides more options for teaching methods. Selecting appropriate teaching methods significantly enhances teaching effectiveness38.

-

3.

Professional distinction (PD) Different agricultural disciplines have varying directions, requiring different levels and scopes of knowledge39. The professional distinctions should be fully considered when constructing the scoring matrix.

-

4.

Teaching quality assessment methods (TQ) Choosing reasonable assessment methods not only boosts students’ learning motivation but also improves their innovative competencies40.

-

5.

Security knowledge acquired (SC) Adopting different teaching contents, methods, and assessment approaches leads to varying levels of safety knowledge acquired by students. This indicator serves as the ultimate evaluation of teaching effectiveness41.

Miller’s classic research indicates that the capacity of human working memory is approximately 7 ± 2 information chunks42. The seven-point scale is precisely located near the upper limit of this cognitive comfort zone. It can provide evaluators with sufficient gradation to make fine distinctions (superior to the five-point scale), while avoiding decision fatigue and cognitive unreliability caused by too many levels (such as ten). This design ensures data variance while minimizing the subjective measurement error of evaluators to the greatest extent. At the same time, the seven-point scale has a wide application basis, such as semantic differential43, self-evaluation44, etc. Relevant studies have shown that seven evaluation levels can ensure discrimination while avoiding cognitive overload of evaluators45, Moreover, in the early stage of the research, interviews were conducted with ten teaching experts, and the collected evaluation data showed that the score values were non-uniformly distributed, with obvious clustering phenomena near thresholds such as 0.45 and 0.75, verifying the rationality of the interval division in Table 1. Therefore, this study selects seven evaluation levels.

Each indicator is divided into seven levels based on its characteristics: Extremely High (EH), High (H), Lower High (LH), Middle (M), Lower (LE), Low (L), and Extremely Low (EL). The indicators are quantified according to semantic conventions, and the levels and corresponding scoring ranges are shown in Table 146,47.

After quantifying the indicator scores, the evaluation indicator set \(\varvec{\varOmega}\) is constructed based on the evaluation indicators:

Indicator weight calculation based on the DEMATEL method

Typically, the weights of teaching evaluation indicators are determined subjectively, which introduces uncertainty into the evaluation of influencing factors. To ensure the objectivity of the weights, the DEMATEL method is used to calculate the weights48,49. The steps are as follows:

Step 1

Based on the evaluation indicator set \(\varvec{\varOmega}\), the scoring matrix \(\varvec{\varOmega}{\text{=}}{\left[ {{\sigma _{ij}}} \right]_{m \times m}}\) is obtained. The scores in the matrix are normalized according to Formula 2.

where \(t=\frac{1}{{\mathop {\hbox{max} }\limits_{{1 \leqslant i \leqslant m}} \sum\nolimits_{{j=1}}^{m} {{s_{ij}}} }}\)is a standardization factor, ensuring that the sum of all rows in the standardized matrix \({\varvec{\varOmega}_0}\) does not exceed 1. \({s_{ij}}\)represents the influence intensity of indicator i on indicator j,\(\sum\nolimits_{{j=1}}^{m} {{s_{ij}}}\)represents the total direct influence of indicator i on all other indicators, and \(\mathop {\hbox{max} }\limits_{{1 \leqslant i \leqslant m}} \sum\nolimits_{{j=1}}^{m} {{s_{ij}}}\) represents the maximum value among all row sums.

Step 2

According to Eq. (3), the comprehensive relationship matrix \({{\varvec{R}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{j}}}}={\left[ {{r_{ij}}} \right]_{m \times m}}\) is calculated.

where \({\varvec{\varOmega}_0}\) represents the standardized direct influence matrix, \({\varvec{E}}\) is the identity matrix, \({\left( {{\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}} \right)^{ - 1}}\)represents the inverse matrix of \(\left( {{\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}} \right)\), and \({\varvec{R}}\) represents the total influence matrix (including both direct and indirect influences).

Step 3

Based on the comprehensive relationship matrix \({{\varvec{R}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{j}}}}\) and the rules of determinant operations, the influence degree \({{\varvec{A}}_{\varvec{i}}}={\left[ {\sum\limits_{{j=1}}^{m} {{r_{ij}}} } \right]_{m \times 1}}\) and the influenced degree \({{\varvec{B}}_{\varvec{j}}}={\left[ {\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{m} {{r_{ij}}} } \right]_{m \times 1}}\) of each indicator are obtained by summing the rows and columns, respectively.

Step 4

The cause degree represents the influence factors between indicators, while the centrality degree indicates the importance of each indicator itself. According to Eqs. (4) and (5), the cause degree and centrality degree are calculated, respectively.

The formula for the cause degree is:

where \({{\varvec{C}}_i}\) represents the cause degree. If \({{\varvec{C}}_i}>0\)t indicates that the indicator is a causal factor, if \({{\varvec{C}}_i}<0\), it indicates that the indicator is result facto, if \({{\varvec{C}}_i}=0\)it indicates that the indicator is a balancing factor.

The formula for the centrality degree is:

where \({{\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) represents the centrality degree. The larger \({{\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) it is, the more important the indicator i is in the system. A high value \({{\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) means that the indicator strongly influences other indicators and is also strongly influenced by other indicators, reflecting the indicator’s pivotal position in the network.

Step 5

Calculate the comprehensive evaluation value of each indicator according to Eq. (6)

where \({{\varvec{Q}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) represents the comprehensive evaluation value of the corresponding indicator.

Step 6

Calculate the relative weights according to Eq. (7)

where \({\omega _i}\) represents the weights of each indicator, \({\omega _i} \in (0,1)\), and \(\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{m} {{\omega _i}} =1\).

The weight set \(\varvec{\omega}={\left[ {{\omega _i}} \right]_{i=m}}\) is obtained through calculations from Step 1 to Step 6.

Example 1

Toy example for the DEMATEL process.

Step 1: Problem definition. Consider a simplified teaching evaluation system with three indicators: TC, TM and PD. We construct a 3 × 3 direct influence matrix based on expert linguistic assessments in Table 2.

Step 3

Normalization. Firstly, calculate row sums.

Row 1 (TC): 0 + 0.825 + 0.675 = 1.500.

Row 2 (TM): 0.525 + 0 + 0.825 = 1.350.

Row 3 (PD): 0.25 + 0.40 + 0 = 0.650.

Maximum row sum:\(\hbox{max} (1.500,1.350,0.650)=\)1.500

Using formula (2), solve for the Normalized Matrix.

\({\varvec{\varOmega}_0}=t\cdot \varvec{\varOmega}=\frac{1}{{1.500}}\cdot \left[ \begin{gathered} {\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0.825{\text{ }}0.675 \hfill \\ 0.525{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0.825 \hfill \\ 0.25{\text{ 0}}{\text{.40 0}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]=\left[ \begin{gathered} {\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0.5500{\text{ }}0.4500 \hfill \\ 0.3500{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0.5500 \hfill \\ 0.1667{\text{ 0}}{\text{.3667 0}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]\)

Step 3: Calculate the comprehensive relationship matrix \({\varvec{R}}\).The identity Matrix \({\varvec{E}}\) is as:

\({\varvec{E}}=\left[ \begin{gathered} 1{\text{ }}0{\text{ }}0 \hfill \\ 0{\text{ }}1{\text{ }}0 \hfill \\ 0{\text{ 0 1}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]\)

Compute \({\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}\) is as:

\({\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}=\left[ \begin{gathered} {\text{ 1 -}}0.5500{\text{ -}}0.4500 \hfill \\ - 0.3500{\text{ }}1{\text{ -}}0.5500 \hfill \\ {\text{-0}}{\text{.1667 -0}}{\text{.2667 1}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]\)

Inverse of \({\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}\) is as:

\({\left( {{\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}} \right)^{ - 1}}=\left[ \begin{gathered} {\text{1}}{\text{.9547 }}1.5847{\text{ }}1.7295 \hfill \\ 1.2953{\text{ }}2.2217{\text{ 1}}{\text{.8941}} \hfill \\ {\text{0}}{\text{.7708 1}}{\text{.0169 2}}{\text{.0780}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]\)

the comprehensive relationship matrix \({\varvec{R}}\) is as:

\({\varvec{R}}={\varvec{\varOmega}_0}{\left( {{\varvec{E}} - {\varvec{\varOmega}_0}} \right)^{ - 1}}=\left[ \begin{gathered} {\text{1}}{\text{.0978 }}1.3651{\text{ }}1.4614 \hfill \\ 1.3383{\text{ }}1.3247{\text{ 1}}{\text{.7856}} \hfill \\ {\text{0}}{\text{.7246 0}}{\text{.8455 1}}{\text{.0524}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right]\)

Step 4: Calculate the cause degree and the centrality degree.

Row sums: A1 = 1.0978 + 1.3651 + 1.4614 = 3.9243, A2 = 1.3383 + 1.3247 + 1.7856 = 4.4486, A3 = 0.7246 + 0.8455 + 1.0524 = 2.6225.

Column sums: B1 = 1.0978 + 1.3383 + 0.7246 = 3.1607, B2 = 1.3651 + 1.3247 + 0.8455 = 3.5353, B3 = 1.4614 + 1.7856 + 1.0524 = 4.2994.

According to formula (4), the cause degree is as: C1(TC) = 3.9243–3.1607 = 0.7636, C2(TM) = 4.4486–3.5353 = 0.9133, C3(2.6225–4.2994 = -1.6769).

According to formula (5), the centrality degree is as: D1 (TC) = 3.9243 + 3.1607 = 7.0850, D2 (TM) = 4.4486 + 3.5353 = 7.9839, D3 (PD) = 2.6225 + 4.2994 = 6.9219.

Step 5: Calculate Final Weights. Using formulas (6) and (7), normalized prominence weights:

According the results, TM has the highest centrality degree (D2 =7.9839). indicating it is the most central indicator in the system. PD (C3 = -1.6769) is identified as a net effect factor, meaning it is highly influenced by other factors but exerts relatively less influence on them. Both TC and TM are cause factors, actively influencing other indicators in the system. The final weights reflect both the centrality and cause degree each indicator, with PD receiving the highest weight due to its strong position as an effect factor that accumulates influences from other indicators.

This toy example demonstrates the complete DEMATEL process from linguistic assessments to numerical weights, showing how qualitative judgments can be transformed into quantitative importance measures for decision-making.

Probabilistic linguistic term sets and possibility degree

Construction of probabilistic linguistic term sets and possibility degree

Definition 1

A PLTS27 defined on a domain is represented as follows:

where \({l^k}\left( {{p^k}} \right)\) represents an element in the PLTS, \({l^k}\) is the linguistic term, and \({p^k}\) is the probability corresponding to \({l^k}\).

Definition 2

If the probability information defined on the PLTS L does not satisfy \(\sum\limits_{{k=1}}^{n} {{p^k}} =1\), standardization is required. The standardized probability information is:

The standardized PLTS after standardization is represented as:

where \(\sum\limits_{{k=1}}^{n} {{{\tilde {p}}^k}} =1\).

Definition 3

Suppose \(\Omega =\left\{ {\left. {{\Omega _i}} \right|i=1,2, \ldots ,\delta } \right\}\) is a given reference PLTS, and the standardized PLTSs \({L_1}=\left( {\left. {l_{1}^{k}\left( {\tilde {p}_{1}^{k}} \right)} \right|k=1,2, \ldots ,{n_1}} \right)\) and \({L_2}=\left( {\left. {l_{2}^{k}\left( {\tilde {p}_{2}^{k}} \right)} \right|k=1,2, \ldots ,{n_2}} \right)\) are defined on \(\Omega\). The possibility degree formula50 for the PLTS \({L_1} \geqslant {L_2}\) is defined as:

where, \(c_{1}^{k}\) and \(c_{2}^{k}\) are the subscripts of \(l_{1}^{k}\) and \(l_{2}^{k}\) in the linguistic term set,\(\tilde {p}_{1}^{k}\) and \(\tilde {p}_{2}^{k}\) are the corresponding standardized probability information.

Definition 4

If there are two standardized PLTSs \({L_1}\)and \({L_2}\) the possibility degree comparison relationship between \({L_1}\)and \({L_2}\) is defined as:

Definition 5

Suppose the possibility degree matrix \({{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) for a certain attribute i is calculated according to Definition 3. \({{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) is defined as:

Based on the calculated weights \({\omega _i}\) the comprehensive possibility degree matrix \({\varvec{P}}\) is defined as:

Definition 6

Let \({\varvec{x}}={\left( {{x_1},{x_2}, \ldots ,{x_n}} \right)^T}\) and \({x_i} \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) be the ranking vectors of the comprehensive possibility degree matrix. \({x_i}\) is defined as:

Example 2

Illustrating the advantage of the proposed possibility degree.

Consider the evaluation of teaching experts using the 7-level linguistic term set with the following scoring ranges, the Linguistic term set with precise scoring ranges is shown in Table 3.

Both PLTS are based on the language set \(\Omega =\left\{ {{S_0}:EL,{S_1}:L,{S_2},LE,{S_3}:M,{S_4}:LH,{S_5},H,{S_6}:EH} \right\}\), where L1 = {S5(1.0)} (expectation = 5.0, variance = 0), L2 = {S4(0.5), S5(0.5)} (expectation = 4.5, variance = 0.25), and L3 = {S4(0.2), S5(0.6), S6(0.2)} (expectation = 5.0, variance = 0.32).

Mathematical comparison using subscripts,

For L1: Subscript = 5, Probability = 1.0.

For L2: Subscript= {4, 5} with probabilities {0.5 0.5}.

For L3: Subscripts = {4, 5, 6} with probabilities {0.2, 0.6, 0.2}.

Comparison is performed by calculating the expectation value of each PLTS:

For L1: E(L1) = 5 × 1.0 = 5.0.

For L2: E(L2) = 4 × 0.5 + 5 × 0.5 = 4.5.

For L3: E(L3) = 4 × 0.2 + 5 × 0.6 + 6 × 0.2 = 5.0.

Thus, the traditional method yields: L1 = L3 > L2.

According to formulas (7) and (8), set \(\delta =7\), the calculation process of our proposed possibility degree is as follow:

Step 1: Calculate t-values. According to the formulas (12) and (13), where \(\delta =7\):

\(t(4)\)= 0.4081,\(t(5)\) = 0.4592,\(t(6)\)= 0.4897.

Step 2: Calculate\(\sum {{t_k}{p_k}}\)for each PLTS.

For L1: \(\sum {{t_1}{p_1}}\) = \(t(5)\)×1.0 = 0.4592.

For L2: \(\sum {{t_2}{p_2}}\)= \(t(4)\)×0.5 + \(t(5)\)×0.5 = 0.4081 × 0.5 + 0.4592 × 0.5 = 0.4337.

For L3: \(\sum {{t_3}{p_3}}\)= \(t(4)\)×0.2 + \(t(5)\)×0.6 + \(t(6)\)×0.2 = 0.4550.

Step 3: Calculate pairwise possibility degrees. According to the formula (11),

\(P({L_1} \geqslant {L_2})\)= 0.5 + 0.4592 − 0.4337 = 0.5255,

\(P({L_1} \geqslant {L_3})\)= 0.5 + 0.4592 − 0.4550 = 0.5042,

\(P({L_3} \geqslant {L_2})\)= 0.5 + 0.4550 − 0.4337 = 0.5213.

Step 4: Determine the ranking.

Since \(P({L_1} \geqslant {L_3})\) > 0.5, and \(P({L_3} \geqslant {L_2})\) > 0.5. Final ranking: L1 > L3 > L2.

From the above calculation process and results, we can see that the traditional method based on expectation would considerL1 = L3 > L2. However, the evaluation of L3 shows significant divergence (large variance), while the evaluation of L1 is highly consistent. In actual decision-making, we might prefer the more consistently evaluated L1. A formula based solely on expectations might yield \(P({L_1} \geqslant {L_3})\)= 0.5, failing to distinguish between L1 and L3. The possibility degree formula we proposed in this paper is used to calculate that \(P({L_1} \geqslant {L_3})\) = 0.5042 > 0.5, clearly indicating that although the expectations are the same, L1 is considered superior to L3 due to its more concentrated distribution. This counterexample demonstrates that the method presented in this paper can capture the variance information overlooked by the compared methods, thereby making more refined and reasonable distinctions.

Probabilistic linguistic possibility degree teaching evaluation process

Step 1: Construct the evaluation indicator matrix \(\varvec{\varOmega}\) based on the evaluation indicator formula (1) and the scoring table.

Step 2: Calculate the relative weights based on Eqs. (2–7) of the DEMATEL method to obtain the weight set \(\varvec{\omega}\).

Step 3: Calculate the standard probabilistic linguistic set based on Eqs. (8–10), compute the possibility degrees for individual indicator probabilistic linguistic sets according to Eqs. (11–14), and mutually compare the possibility degrees.

Step 4: Calculate the individual possibility degree matrix \({{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) based on Eq. (15), and compute the comprehensive possibility degree matrix \({\varvec{P}}\) by combining weight set \(\varvec{\omega}\) with the individual possibility degree matrix \({{\varvec{P}}_{\varvec{i}}}\) according to Eq. (16).

Step 5: Sort \({\varvec{P}}\) according to Eq. (17) to obtain the final results.

Teaching effectiveness evaluation and validation

Teaching instance validation

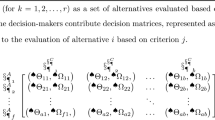

Through questionnaires, interviews, and other methods, five agricultural experts responsible for laboratory safety (T1-T5) were surveyed to rate various indicators. The standardized probabilistic linguistic evaluation matrix \(\varvec{\varOmega}\) was constructed, as shown in Table 4.

Calculate the comprehensive relationship matrix based on Eqs. (2) and (3).

Calculate the causality degrees and centrality degrees of each indicator, as shown in Table 6.

The weight set \(\varvec{\omega}=\left\{ {0.308,0.264,0.070,0.104,0.254} \right\}\) is obtained after normalization processing of each indicator. The DEMATEL causal diagram of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course is shown in Fig. 1, TC and TQ assessment methods are the core driving factors in the cause area, exerting a significant influence on other indicators. The bar chart of DEMATEL-based weights of teaching effectiveness factors is shown in Fig. 2, the weight distribution in further validates this point, with TC having the highest weight.

Step 2

Perform comparative calculations on the possibility degrees of individual indicator probabilistic linguistic sets based on Eqs. (11–14), and the results are as follows.

Step 3

Calculate the comprehensive probabilistic linguistic possibility degree comparison based on Eq. (16), as follows.

Step 4

Compare the comprehensive possibility degree matrix based on Eq. (17) and calculate as follows.

Step 5

Rank the influencing factors based on the calculation results of ranking vector \({\varvec{x}}\), with the results as follows.

According to the above ranking results, \({x_{TC}}\) has the highest score and \({x_{PD}}\) has the lowest score.

Robustness test

To verify the robustness of the research results, we conducted a systematic sensitivity analysis, including: sensitivity analysis of parameters, sensitivity test of the language-numeric mapping scheme, and cross-validation based on leave-one-out method.

Sensitivity analysis of parameters

To verify the stability of the ranking results of the model proposed in this paper, a sensitivity analysis is conducted. We fine-tune the TC indicator, which has the largest weight, by adjusting its weight by ± 5% and ± 10% from the benchmark value (0.308), and simultaneously adjust the weights of other indicators proportionally to keep the total sum at 1, to observe whether there are significant changes in the final ranking51. The original weights of the evaluation model’s indicators are shown in Table 7. The expert scores and rankings under the original indicator weights are presented in Table 8. The calculation method for the transformation of indicator weights is as follows:

where \(\mu\) is the weight adjustment coefficient, since we set TC to be adjusted by ± 5% and ± 10% respectively from the base value (0.308), the values of \(\mu\)are 0.9, 0.95, 1, 1.05, and 1.10. \(\mu \cdot {\omega _{TC}}\)represents the weight of TC after adjustment. (\(1 - \mu \cdot {\omega _{TC}}\)) is the sum of the weights of the other four indicators, \({\omega _i}\)the original proportion of the other indicators, and \({\omega _{inew}}\) is the adjusted weight of the other indicators.

Parameters sensitivity experimental results

The expert scores and rankings after adjusting the TC weights by ± 5% and ± 10% according to Formula 18 are shown in Table 9. The impact of TC weight changes on expert scores is illustrated in Fig. 3, the changes in expert rankings under different TC weights are presented in Fig. 4, and the Distribution of Indicator Weights under Different TC Weights is depicted in Fig. 5.

Parameters sensitivity analysis

As shown in Table 8, when the TC weight fluctuates within ± 10%, the ranking order of experts remains unchanged as T1 > T2 > T4 > T5 > T3. The impact of TC weight changes on expert scores is very small, indicating that the model’s ranking results are highly stable to the changes in the weight of the most important indicator. The sensitivity analysis results show that the evaluation model proposed in this paper based on DEMATEL and probabilistic linguistic possibility degree has good robustness. Even when the weight of the most important indicator fluctuates reasonably, the comprehensive evaluation results of experts’ teaching effectiveness remain stable, proving that the model can provide reliable and consistent ranking results.

Sensitivity test of the Language-numeric mapping scheme

To examine the sensitivity of the evaluation results to the selection of mapping schemes, this study designed a comparative experiment, using three alternative mapping schemes to compare with the scheme proposed in this paper.

Comparative experiment design

Let the mapping scheme of this article be M₀, and define two alternative schemes:

Equidistant mapping scheme M147: Divide the interval [0, 1] into 7 equal parts uniformly. The width of each interval = 1/7 ≈ 0.1429.

Logarithmic mapping function M252: Based on the logarithmic scale division, \(x_{i}\)\(=\)\(\log\)\((1 + i)\)\(/\log\)\(8\),\(i=0,1,...,6\),\({x_i}\) is the logarithmic division of the interval length.

The Language-numeric mapping scheme evaluation index

To quantitatively compare the differences in results, two indicators, namely the weight difference degree \(\vartriangle \omega\) and the ranking consistency index \(RCI\) are defined53. The weight difference degree is as:

where \({\omega _{ial}}\) is the weight of the original scheme,\({\omega _{ior}}\) is the weight of the alternative scheme. n is the number of indicators.

The ranking consistency index is as:

where \({C_E}\) is the number of experts with the same ranking, and \({N_E}\) is the total number of experts.

Experimental results and analysis for the Language-numeric mapping scheme

The experimental results are shown in Table 10. The weight difference degree \(\vartriangle \omega\) of all alternative schemes is less than 0.03, indicating that the change of mapping schemes has a limited impact on the index weights. The expert ranking consistency \(RCI\)is all over 95%, and the optimal expert (T1) remains consistent in all schemes. Although the numerical mapping methods are different, the core results of the evaluation conclusion (optimal expert selection, identification of important indicators) remain unchanged. The experimental comparison results prove the reliability of our mapping scheme.

Cross-validation based on leave-one-out method

In the leave-one-out cross-validation process54,55, one expert is removed at a time from the five experts, and the evaluation results are recalculated using the data of the remaining four experts. Here we have defined two indicators: the ranking stability index \(RSI\) and the weight consistency coefficient \({\omega _c}\). The formula for the ranking stability index is as:

where \({C_I}\)represents the number of indicators for consistent ranking, and \({T_I}\) represents the total number of indicators. The formula for the weight consistency coefficient is as:

where \(\vartriangle {\omega _{\hbox{max} }}\)represents the maximum variation of the weight of this variable obtained in each calculation during leave-one-out cross-validation. It measures the sensitivity of the model weights to minor data perturbations (deleting one sample). If \(\vartriangle {\omega _{\hbox{max} }}\) is small, it indicates that the coefficient changes little during leave-one-out, and the model stability is high. If \(\vartriangle {\omega _{\hbox{max} }}\) is large, it indicates that the model weights are sensitive to individual samples, and the stability is poor.\({\omega _r}\)represents the absolute value of the weight of a certain variable obtained by training with all the data. The closer the \({\omega _c}\) value is to 1, the better the consistency of the weights.

As shown in Table 11, even if any one expert is removed, the evaluation rankings remain exactly the same, and the weight changes do not exceed 2%. This proves that the results are not sensitive to the evaluation of any single expert.

Reliability analysis of expert evaluations

To conduct a reliability analysis of the expert evaluations, we carried out Kendall’s coefficient of concordance test and intra-class correlation coefficient analysis.

Kendall’s coefficient of concordance test

In the Kendall’s coefficient of concordance test56, the evaluation scores of 5 experts on 5 indicators are converted into ranks, and the Kendall’s W coefficient is calculated. Let the evaluation score of expert j on indicator i be \({x_{ij}}\), convert the scores into ranks \({r_{ij}}\) (1 for the highest score and 5 for the lowest score). The calculation formula is:

where \(m=5\) is the number of experts, \(n=5\)is the number of indicators, \(S={\sum {({R_i} - R)} ^2}\), \({R_i}\) is the rank sum of indicator i, and R is the average rank sum. When \(W>0.7\), it indicates that there is good consistency among experts. When \(0.5<W \leqslant 0.7\), it indicates that there is moderate consistency among experts. When \(W \leqslant 0.7\), it indicates that the consistency among experts is poor.

Intra-class correlation coefficient analysis

We selected the ICC(3,1) model57 to conduct the intra-class correlation coefficient analysis and calculate the intra-class correlation coefficient of the expert scores. The calculation formula is:

where \(MSB\)is the mean square between groups, indicating the variation among indicators.\(MSW\)is the mean square within groups, indicating the variation among experts. k is the number of experts. When \(ICC>0.75\), it indicates excellent reliability. When \(0.6<ICC \leqslant 0.75\), it indicates good reliability. When \(ICC \leqslant 0.6\), it indicates insufficient reliability.

Analysis of the results of expert evaluation reliability

As shown in Table 12, the Kendall’s coefficient W in the expert evaluation reliability results is 0.82, indicating a high degree of consistency among the experts’ evaluations. The intra-class correlation coefficient value \(\left( {ICC} \right)\) is 0.78, suggesting excellent evaluation reliability. These two expert evaluation consistency test results indicate that all consistency indicators have reached a good level or above, proving that the evaluations of the five experts are reliably consistent and the research results are not the accidental outcome of a small sample.

Bootstrap-based confidence interval estimation

Bootstrap confidence intervals58 estimation does not rely on theoretical assumptions about the distribution of weights. Through Bootstrap confidence interval estimation, we can quantify the statistical uncertainty of model weights and evaluate their stability.

Bootstrap sampling method

The process of the sampling method based on Bootstrap is as follows:

Step 1: Five samples were randomly drawn with replacement from the experts’ original data.

Step 2: Recalculate all evaluation indicators based on the sampled data.

Step 3: Repeat the above process B = 1000 times to obtain 1000 sets of estimated values.

Step 4: Calculate the 95% confidence interval based on 1000 estimated values.

The formula for calculating the 95% confidence interval \({Q_v}\)59 is as follows:

where \({Q_{v2.5}}\) and \({Q_{v97.5}}\) represent the interval boundaries formed by taking the 2.5th percentile and the 97.5th percentile from the 1000 sets of estimated values obtained through Bootstrap resampling, respectively.

Confidence interval analysis of the degree of cause indicators

As shown in Table 13, the 95% confidence interval of TC cause degree ([0.315, 0.387]) is completely greater than 0, indicating it is a significant cause factor. The 95% confidence interval of TM cause degree ([0.005, 0.075]) includes positive values but is close to 0, suggesting it is a weak cause factor. The 95% confidence interval of PD cause degree ([−0.248, −0.182]) is completely less than 0, indicating it is a significant result factor. The 95% confidence interval of TQ cause degree ([0.418, 0.480]) is completely greater than 0, indicating it is a significant cause factor. The 95% confidence interval of SC cause degree ([−0.340, −0.284]) is completely less than 0, indicating it is a significant result factor.

where \({C_I}\) represents the width of the confidence interval, and \(\left| {{P_{EV}}} \right|\) represents the absolute value of the point estimate.

After calculation, the \(DCI\) of TQ is 0.863, that of SC is 0.821, that of TC is 0.795, that of PD is 0.693, and that of TM is 0.250.

Confidence interval analysis of centrality indicators

To analyze the stability of centrality, we have defined the centrality stability index \(CCI\)61, which is expressed as follows:

where \({C_{AR}}\) is the average relative error of centrality, and \({C_{MR}}\) is the maximum possible error of centrality.

As shown in Table 14, the centrality hierarchy of TC centrality and TM centrality is at the first level, with the highest system influence. The centrality hierarchy of SC centrality is at the second level, with medium system influence. The centrality hierarchy of TQ centrality is at the third level, with relatively low system influence. The centrality hierarchy of PD centrality is at the fourth level, with the lowest system influence.

Analysis of confidence interval of comprehensive weights

To analyze the stability of the comprehensive weight, we have set up the comprehensive weight stability index \(CWI\)62, which is expressed as follows:

where \({A_{RE}}\) is the average relative error of the weights, and \({M_{PE}}\) is the maximum possible error.

As shown in Table 15, the 95% confidence intervals of the comprehensive weights calculated based on centrality and causality for all indicators do not include 0 and there is no overlap among them. The confidence interval of TC weight is [0.291, 0.321], which is significantly higher than that of other indicators. The confidence intervals of TM and SC weights have some overlap, but the upper limit of TM (0.274) is lower than the lower limit of SC (0.242).

Comprehensive evaluation of statistical stability

To comprehensively evaluate the stability of confidence intervals, we have established a comprehensive stability index \(CSI\)63, which is expressed as follows:

where \({A_E}\) represents the average relative error of the indicator, and \({A_{BE}}\) represents the maximum possible error of the indicator.

After calculation, the stability index of the cause degree\(DCI\)is 0.652, the stability index of the centrality degree is 0.824, and the stability index of the weight is 0.867. The relative error of the weight estimation CSI = 0.867 is controlled within ± 11.43%, making the weight estimation the most stable. The relative error of the centrality degree estimation CSI = 0.824 is controlled within ± 6.52%, indicating that the centrality degree estimation is relatively stable. The cause degree estimation CSI = 0.652, and the coefficient of variation of the TM cause degree is as high as 1.750, showing relatively low stability.

Confidence interval estimation analysis

All point estimates of the indicators are within the 95% confidence interval. TC and TQ are identified as cause factors, while PD and SC are recognized as result factors with statistical significance. The weight ranking (TC > TM > SC > TQ > PD) is supported by the confidence interval analysis. The uncertainty of the cause degree and weight estimation of the PD indicator is relatively large. The cause degree of TM is close to 0, resulting in its confidence interval including the area near 0. For high certainty indicators (TC, TM, SC), decision-makers can rely on the model results with more confidence. The overall model provides reliable evaluation results at the 95% confidence level.

The confidence interval analysis based on Bootstrap indicates that our conclusion is statistically significant. TC and TQ are confirmed as significant cause factors (the confidence interval is completely greater than 0), PD and SC are confirmed as significant result factors (the confidence interval is completely less than 0), and TM is a weak cause factor. The relative error of the weight estimation is controlled within a reasonable range, supporting the reliability of the evaluation results.

Comparative analysis of methods

To verify the effectiveness and advantages of the DEMATEL method (DPL) integrating PLTS and possibility degree proposed in this paper, we designed a systematic comparative experiment. To ensure that all differences in comparison are due to the methodology itself rather than different parameters or settings, all comparative methods use exactly the same original expert evaluation data and keep the pre-processing steps as consistent as possible.

Comparison baseline and experimental setup

We selected three representative benchmark methods for fair comparison, as is shown below:

-

(1)

Variants of the classical method

Crisp-DEMATEL (CD)64: The probabilistic linguistic evaluations are aggregated into crisp numbers through the calculation of expected values, and then the classical DEMATEL is applied. This comparison aims to separate and highlight the value of probabilistic linguistic processing in handling uncertainty.

PLWA-DEMATEL (PLD)65: The probabilistic linguistic evaluations are aggregated using the probabilistic linguistic weighted averaging (PLWA) operator, followed by DEMATEL analysis. This comparison is used to evaluate the impact of different information aggregation strategies.

-

(2)

Other probabilistic linguistic decision-making models

PL-TOPSIS (ET)66: A TOPSIS method based on probabilistic linguistic distance measures.

PL-TODIM (TL)67: A probabilistic linguistic TODIM method considering the psychological behavior of decision-makers.

-

(3)

Fuzzy linguistic variants

Fuzzy-DEMATEL (FL)68: The original evaluations are transformed into triangular fuzzy numbers and the fuzzy DEMATEL method is applied. This comparison aims to explore the effects of different types of linguistic uncertainty processing methods.

To ensure the reproducibility of the experiments, all key parameters of the methods were standardized as shown in Table 16. The experiments were conducted in the same computing environment (MATLAB 2023b, Windows 11 operating system, Intel(R) Core (TM) i9-14900KF (3.20 GHz)), and each method was run 30 times, with the average running time of each method recorded.

Results analysis and comparison

The evaluation results of the five teaching influencing factors by each method are shown in Table 17. To quantitatively compare the consistency of the results, we calculated the Spearman rank correlation coefficient between the results of each method and the results of the method in this paper (DPL)69.

The DPL method we proposed shows a high degree of consistency (ρ ≥ 0.95) with other mainstream methods (PLD, TL, FL) in the ranking of factor importance, all identifying TC and TM as the two most critical factors, effectively verifying the reliability of this method and the robustness of its conclusions. To further quantify the stability of DPL, we recalculated the factor ranking each time and conducted a Bootstrap stability test. We further calculated Kendall’s coefficient of concordance to be 0.82, indicating that the output ranking of this method has a high degree of internal consistency when the input data has reasonable fluctuations, verifying its good robustness.

Summary

This Section conducts a comprehensive validation of the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed DEMATEL method integrating probability linguistic possibility degree (DPL) in the evaluation of the teaching effectiveness of the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course through systematic empirical analysis and method comparison. Firstly, a standardized probability linguistic evaluation matrix was constructed, and the DPL method was applied to calculate the centrality, causality, and final weights of each indicator. The results show that TC is the core driving factor in the system, having a significant causal impact on teaching effectiveness, and it has the highest weight. The specialized differentiation of teaching methods (PD) has the least influence. This conclusion is visually presented in the DEMATEL causal diagram.

To verify the reliability of the results, this section conducts multi-level robustness tests. Parameter sensitivity analysis indicates that even when the weight of the highest-weighted TC indicator is perturbed by ± 10%, the comprehensive evaluation ranking of teaching effectiveness by experts remains stable. The sensitivity test of the language-numerical mapping scheme shows that using different mapping functions (equidistant, logarithmic) has a limited impact on the indicator weights (difference < 0.03), and the optimal expert identification results are consistent, demonstrating the robustness of the proposed mapping scheme. Leave-one-out cross-validation further confirms that the results are not sensitive to the evaluation of individual experts, with a ranking stability index of 100% and a weight consistency coefficient close to 1, demonstrating the method’s excellent anti-interference ability. Expert evaluation reliability analysis (Kendall’s W = 0.82, \(ICC=0.78\)) statistically confirms the high consistency and reliability of the expert group’s evaluation opinions.

To quantify the statistical uncertainty of the model results, this section uses the Bootstrap method to calculate the 95% confidence intervals of each indicator. The results show that all point estimates are within the confidence intervals, and the key conclusions are statistically significant: TC and TQ are confirmed as significant causal factors (confidence intervals completely greater than 0), and PD and SC are confirmed as significant result factors (confidence intervals completely less than 0). Through a comprehensive assessment of the stability indices of causality, centrality, and comprehensive weights, it is found that the stability of weight estimation is the highest (\(CSI=0.867\)), followed by centrality estimation, and the stability of causality estimation (especially TM) is relatively low. This provides a basis for decision-makers to understand the certainty differences of different indicators.

Finally, through a systematic comparative analysis with classic DEMATEL variants (CD, PLD), other probability linguistic decision-making models (ET, TL), and fuzzy linguistic variants (FL), the superiority of DPL is verified at the methodological level. DPL has a high consistency in ranking results with multiple mainstream methods (Spearman correlation coefficient ρ ≥ 0.95), proving the universality of its conclusions. More importantly, the comparison highlights the unique value of the DPL method: compared with methods that directly aggregate probability linguistic information (CD), DPL retains the distribution and uncertainty information in expert evaluations through possibility degree calculation; compared with other comprehensive decision-making models (ET and TL), DPL not only provides a ranking of factor importance but also reveals the complex causal network structure within the system, providing deeper systematic insights for management decisions.

In conclusion, this section, through various experimental design and comprehensive validation analysis, confirms that the proposed DPL method is an effective, robust, and highly interpretable tool for evaluating teaching effectiveness. It can not only reliably identify key influencing factors but also analyze the causal mechanisms between them, and it has good robustness against data perturbation, parameter settings, and calculation methods, providing scientific and reliable methodological support for complex educational system analysis and decision-making in an uncertain linguistic environment. From the above analysis results, it can be seen that the proportion of teaching content in the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course is the largest and most important, while the impact of professional differentiation is the smallest. This is mainly because the content covered in laboratory safety access education focuses more on universal and fundamental safety knowledge, thus the influence of professional differentiation is relatively weak.

Furthermore, it is observed that the evaluation results of the DEMATEL method based on probabilistic linguistic possibility degree (DL), the probabilistic linguistic fuzzy cognitive map method (FL), and the probabilistic linguistic TODIM method (TL) showed a high degree of consistency, while the ELECTRE and TOPSIS methods with probabilistic linguistic terms (ET) yielded different rankings. The DL method analyzes the causal network and influence intensity between indicators through DEMATEL, and its weights are derived from the system structure rather than subjective assumptions, reflecting the inherent importance of factors in the correlation network. The FL method uses fuzzy cognitive maps to depict the nonlinear feedback and dynamic influence between indicators, and its output is the stable state emerging from the internal interaction of the system. The TL method is based on prospect theory, focusing on depicting the decision-makers’ psychological reference points and loss aversion behavior under risk, with its core being the simulation of choices under cognitive biases. These three methods essentially deal with causal, influence, and psychological reference relationships rather than simple attribute additions. Therefore, when they face the same probabilistic linguistic information, they may capture similar systemic structures or decision-makers’ psychological patterns, leading to consistent results. The ET method usually aggregates probabilistic linguistic information into scalar expected values before entering the ELECTRE or TOPSIS process, which may lead to early information loss. This results in the difference between the ET method and the other three methods.

According to the results of this study, teachers in the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course should prioritize the allocation of limited resources to optimizing teaching content and teaching methods. Teaching content and teaching methods are the core for stimulating students’ interest, so more attention should be paid to the quality and interest of teaching content, such as adding appropriate safety education animations and using actual safety incidents in the laboratory as teaching cases.

Conclusions

To evaluate the influencing factors of teaching effectiveness in the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course, this study proposes a method combining the DEMATEL method with probabilistic linguistic possibility degrees. The conclusions are as follows:

By evaluating the influencing factors of teaching effectiveness in the “Safety Access Education in University Laboratories” course, targeted improvements can be made: Teaching content has the greatest impact, so enriching and optimizing content can enhance student engagement and motivation. Professional distinction has the least impact, allowing for appropriately reduced requirements in instructional design. Teaching method plays a positive role in improving teaching outcomes.

The framework integrating the DEMATEL method and probabilistic linguistic possibility degrees proposed in this study provides an effective tool for addressing complex and uncertain educational evaluation issues. The research findings can be directly applied to guide universities in optimizing the design and implementation of laboratory safety courses, which has positive practical significance. Although certain achievements have been made, this study has certain limitations in sample selection: only five experts from the fields of agriculture and laboratory management were invited to participate in the evaluation, with a relatively limited sample size and a relatively concentrated disciplinary background. This may affect the stability and generalizability of the evaluation conclusions to some extent. Simultaneously, although the evaluation index system constructed is based on literature review and theoretical analysis, it may still not fully cover all potential factors affecting teaching effectiveness, thereby introducing the risk of systematic bias.

To overcome the above limitations and deepen the research, future work will be carried out in the following three aspects: First, expand the sample range and diversify the disciplinary background, and conduct verification in a more diverse expert group to enhance the robustness and universality of the conclusions. Second, promote the cross-integration of methodologies, and attempt to combine this model with other multi-criteria decision-making methods (such as the Analytic Network Process) to construct a more refined and adaptable evaluation framework for complex relationships. Finally, extend the data sources and evaluation scenarios: on the one hand, incorporate evaluation data from the student group to form a dual-group decision-making model with expert evaluations; on the other hand, apply this framework to the evaluation of other types of courses to further test its transferability and application boundaries.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this paper.

References

Taylan, O. et al. Assessment of energy systems using extended fuzzy AHP, fuzzy VIKOR, and TOPSIS approaches to manage Non-Cooperative opinions. Sustainability. 12(7). (2020).

Dagistanli, H. A. et al. The optimization of long-term dynamic defense industry project portfolio management with a mixed and holistic project prioritization approach (Dynamic Games and Applications, 2024).

Dağıstanlı, H. A. Weapon system selection for Capability-Based defense planning using Lanchester models integrated with fuzzy MCDM in computer assisted military experiment. Knowl. Decis. Syst. Appl. 1, 11–23 (2025).

Das, U. & Behera, B. Geospatial assessment of ecological vulnerability of fragile eastern duars forest integrating GIS-based AHP, CRITIC and AHP-TOPSIS Models Vol. 15 (Geomatics Natural Hazards & Risk, 2024). 1.

Zhang, W. Investigation of physical education classroom teaching using AHP with IV-CIFS-based aggregation operators. Sci. Rep. 15(1). (2025).

Sun, X., Yu, B.S. & Li, R.M. Designing an innovative Multi-Criteria decision making (MCDM) framework for optimized teaching and delivery of physical education curriculum. Sci. Rep. 15(1). (2025).

Jia, H.C. A study on evaluation of english hybrid teaching courses based on AHP and K-means. Peerj Comput. Sci. 10. (2024).

Afzal, U. et al. Intelligent faculty evaluation and ranking system based on N-framed plithogenic fuzzy hypersoft set and extended NR-TOPSIS. Alexandria Eng. J. 109, 18–28 (2024).

Lin, C.L., Chen, J.J. & Ma, Y.Y. Ranking of service quality solution for blended design teaching using fuzzy ANP and TOPSIS in the Post-COVID-19 era. Mathematics, 11(5). (2023).

Yu, X.J. et al. Comprehensive Evaluation on Teachers’ Knowledge Sharing Behavior Based on the Improved TOPSIS Method. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022 (2022).

Deli, I., Uluçay, V. & Polat, Y. N-valued Neutrosophic Trapezoidal Numbers with Similarity Measures and Application To multi-criteria decision-making Problems. J. Ambient Intell. Humanized Comput. (2021).

Deveci, M. et al. Evaluation of cooperative intelligent transportation system scenarios for resilience in transportation using type-2 neutrosophic fuzzy VIKOR 172 (Transportation Research Part a-Policy and Practice, 2023).

Uluçay, V. & Deli, I. Vikor method based on the entropy measure for generalized trapezoidal hesitant fuzzy numbers and its application (Soft Computing, 2023).

Abdul, D., Jiang, W. Q. & Tanveer, A. Prioritization of renewable energy source for electricity generation through AHP-VIKOR integrated methodology. Renew. Energy. 184, 1018–1032 (2022).

Uluçay, V., Deli, I. & Edalatpanah, S.A. Prioritized aggregation operators of GTHFNs MADM approach for the evaluation of renewable energy sources. Informatica 35 (4), 859–882 (2024).

Deli, I. Bonferroni mean operators of generalized trapezoidal hesitant fuzzy numbers and their application to decision-making problems. Soft. Comput. 25 (6), 4925–4949 (2021).

Deli, I. & Keles, M. A. Distance measures on trapezoidal fuzzy multi-numbers and application to multi-criteria decision-making problems. Soft. Comput. 25 (8), 5979–5992 (2021).

Deli, I. & Karaaslan, F. Generalized trapezoidal hesitant fuzzy numbers and their applications to multi criteria decision-making problems. Soft. Comput. 25 (2), 1017–1032 (2021).

Shi, J. H. et al. Evolutionary model and risk analysis of ship collision accidents based on complex networks and DEMATEL. Ocean Eng., 305. (2024).

Zhang, Z. X. et al. A novel alpha-level sets based fuzzy DEMATEL method considering experts’ hesitant information 213 (Expert Systems with Applications, 2023).

Dagistanli, H. A. & Gencer, C. T. Evaluation of medium-lift forest fire helicopter using q-rung orthopair fuzzy set based alternative ranking technique based on adaptive standardized intervals approach 148 (Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2025).

Erdal, H. et al. Evaluation of anti-Tank guided missiles: an integrated fuzzy entropy and fuzzy CoCoSo multi criteria methodology using technical and simulation data. Appl. Soft Comput., 137. (2023).

Dağıstanlı, H.A., Defense, A.T. & University T.M.A.N. Department of Industrial Engineering, and Prioritizing design criteria for unmanned helicopter systems under uncertainty using fuzzy best worst method approach. J. Intell. Decision Making Granular Comput. 1(1): pp. 1–12. (2025).

Dağıstanlı, H. A. et al. Electric car price prediction using random forest algorithm comparative analysis for Türkiye example and solution proposals with fuzzy sets. Comput. Decis. Mak. Int. J. 2, 671–686 (2025).

Pang, Q., Wang, H. & Xu, Z. S. Probabilistic linguistic linguistic term sets in multi-attribute group decision making. Inf. Sci. 369, 128–143 (2016).

Wu, X. L. & Liao, H. C. An approach to quality function deployment based on probabilistic linguistic term sets and ORESTE method for multi-expert multi-criteria decision making. Inform. Fusion. 43, 13–26 (2018).

Wu, X. L. et al. Probabilistic linguistic MULTIMOORA: A multicriteria decision making method based on the probabilistic linguistic expectation function and the improved Borda rule. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 26 (6), 3688–3702 (2018).

Zhang, Y.R.J., Liang, D.C. & Xu, Z.S. Cross-platform hotel evaluation by aggregating multi-website consumer reviews with probabilistic linguistic term set and choquet integral (Annals of Operations Research, 2022).

Li, Y. et al. Probability Distribution-Based processing model of probabilistic linguistic term set and its application in automatic environment evaluation. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 23 (6), 1697–1713 (2021).

Liu, Z. X. et al. A deep Learning-Based sentiment analysis approach for online product ranking with probabilistic linguistic term sets. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 71, 6677–6694 (2024).

Han, X. R., Zhang, C. & Zhan, J. M. A three-way decision method under probabilistic linguistic term sets and its application to air quality index. Inf. Sci. 617, 254–276 (2022).

Cui, C. S. et al. Hotel recommendation algorithms based on online reviews and probabilistic linguistic term sets. Expert Syst. Appl. 210. (2022).

Yang, H. & Xu, G. L. Tourism attraction selection driven by online tourist reviews: A novel multi-attribute decision making method based on the evidence theory and probabilistic linguistic term sets. Appl. Soft Comput., 177 (2025).

Liu, P. D. et al. Distance education quality evaluation based on multigranularity probabilistic linguistic term sets and disappointment theory. Inf. Sci. 605, 159–181 (2022).

Wu, W. S. Probabilistic linguistic TODIM method with probabilistic linguistic entropy weight and hamming distance for teaching reform plan evaluation. Mathematics, 12(22). (2024).

Fernández-garcía, C. M., Rodríguez-Alvarez, M. & Viñuela-Hernández, M. P. University students and their perception of teaching effectiveness. Effects on students’ engagement. Revista De Psicodidactica, 26(1), 62–69. (2021).

Northey, G. et al. The effect of here and now learning on student engagement and academic achievement. Br. J. Edu. Technol. 49 (2), 321–333 (2018).

Diekhoff, T. et al. Effectiveness of the clinical decision support tool ESR eGUIDE for teaching medical students the appropriate selection of imaging tests: randomized cross-over evaluation. Eur. Radiol. 30 (10), 5684–5689 (2020).

Gosling, E. & Reith, E. Capturing farmers’ knowledge: Testing the analytic hierarchy process and a ranking and scoring method (Society & Natural Resources, 2020) 33, 700–708

Beuchel, P., Ophoff, J. G. & Cramer, C. Thin slices of teaching behavior: Video observation as complement to the assessment of teaching quality and teacher training interventions. Stud. Educational Evaluation, 86. (2025).

Hassim, M. H., Zakaria, Z. & Mahmud, H. Process safety teaching in universities - Current practices and way forward. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 192, 1431–1443 (2024).

Segundo, J. et al. Mapping success profiles for digital freelancers: A configurational approach using entrecomp competencies 83 (Technology in Society, 2025).

Kim, J. et al. Semantic discrepancies between Korean and english versions of the ASHRAE sensation scale. Build. Environ. 221. (2022).

Want, S. C. et al. Seven points as an estimate of the smallest subjectively experienced decrease in body satisfaction on a one-item visual analogue scale. Body Image 51. (2024).

Korbach, A., Brünken, R. & Park, B. Differentiating different types of cognitive load: A comparison of different measures. Educational Psychol. Rev. 30 (2), 503–529 (2018).

Akinci, H. & Ozalp, A. Y. Investigating the effects of different data classification methods on landslide susceptibility mapping. Adv. Space Res. 75 (4), 3427–3450 (2025).

Huang, F. M. et al. Effects of different division methods of landslide susceptibility levels on regional landslide susceptibility mapping. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ., 84(6). (2025).

Bai, Y. P. et al. A BN-based risk assessment model of natural gas pipelines integrating knowledge graph and DEMATEL Vol. 171, p. 640–654 (Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 2023).

Zhou, T.T. et al. Smart experience-oriented customer requirement analysis for smart product service system: A novel hesitant fuzzy linguistic cloud DEMATEL method. Adv. Eng. Inform. 56 (2023).

Fang B., H.B., & Xie D.Y. Probabilistic linguistic multi-attribute decision making method based on possibility degree matrix. Control Decis., 37(8): p. 8. (2021).

Nguyen, V. D. & Gigliarano, C. Sensitivity-based weighting method for composite indicators (Annals of Operations Research, 2025).

Kennedy-Hunt, P. et al. Divisors and curves on logarithmic mapping spaces. Selecta Mathematica-New Ser. 30 (4). (2024).

McAvinue, S. & Dev, K. Comparative evaluation of large Language models using key metrics and emerging tools. Expert Syst., 42(2). (2025).

Pang, Y. et al. Enhanced Kriging leave-one-out cross-validation in improving model estimation and optimization 414 (Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 2023).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 27 (5), 1413–1432 (2017).

Franceschini, F. & Maisano, D. Aggregating multiple ordinal rankings in engineering design: the best model according to the kendall’s coefficient of concordance. Res. Eng. Design. 32 (1), 91–103 (2021).

Xian, S. L. & Zhang, L. Robustness measurement of comprehensive evaluation model based on the intraclass correlation coefficient. Mathematics, 13(11). (2025).

Cheung, S. F., Pesigan, I. J. A. & Vong, W. N. DIY bootstrapping: getting the nonparametric bootstrap confidence interval in SPSS for any statistics or function of statistics (when this bootstrapping is appropriate). Behav. Res. Methods. 55 (2), 474–490 (2023).

Gañan-Cardenas, E. et al. Estimating traffic congestion cost uncertainty using a bootstrap scheme 136 (Transportation Research Part D-Transport and Environment, 2024).

Sabri, D. Rethinking causality and inequality in students’ degree outcomes. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 44 (3), 520–538 (2023).

Jongerling, J., Epskamp, S. & Williams, D. R. Bayesian uncertainty Estimation for Gaussian graphical models and centrality indices. Multivar. Behav. Res. 58 (2), 311–339 (2023).

Horowitz, J. L. & Rafi, A. Bootstrap based asymptotic refinements for high-dimensional nonlinear models. J. Econ., 249. (2025).

Jaworski, J. et al. Evaluation of measurement reliability for selected indices of postural stability based on data from the GYKO inertial sensor system. Biology Sport. 41 (2), 155–161 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Probabilistic Linguistic multi-attribute Group Decision Making Method Considering the Important Degrees of Experts and Attributes 265 (Expert Systems with Applications, 2025).

Liao, H. C. et al. Advances of probabilistic linguistic preference relations: A survey of theory and applications. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 25 (8), 3271–3292 (2023).

Mao, X. B. et al. A new method for probabilistic linguistic multi-attribute group decision making: application to the selection of financial technologies. Appl. Soft Comput. 77, 155–175 (2019).

Liu, P.D. & Teng, F. Probabilistic linguistic TODIM method for selecting products through online product reviews. Inf. Sci. 485, 441–455 (2019).

Ju, P.H.C.Z., Ran Y., & Tu S.Z., A Novel QFD method considering expert’s psychological behavior character under probabilistic linguistic environment . J. Harbin Institute Technol. 52, 8 (2020)

Jiang, J.F., Zhang, X.Y. & Yuan, Z. Feature selection for classification with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient-based self-information in divergence-based fuzzy rough sets. Expert Syst. Appl., 249. (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by Guizhou Provincial “Golden Course” Construction Project (2022294), Guizhou Provincial Teaching Reform Project (GZJG2024297), Project of Department of Education of Guizhou Province: ‘Key Laboratory of Plant Protection Informatization for Characteristic High-efficiency Agriculture in Central Guizhou’ (Qianjiao Keji (2022) No. 052), Research on the Construction and Practice of the Ideological and Political Teaching System for the Course Environmental Engineering Microbiology (2022248).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaohui Song: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Data testing. Yubo Zhang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Formal analysis. Xiangcai Chang: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources. Jie Xiao: Conceptualization, Resources. Xueli Feng: Conceptualization, Formal analysis. Zhengxue Zhao: Conceptualization, Data testing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, X., Zhang, Y., Chang, X. et al. Evaluation of teaching effect factors based on probabilistic language set. Sci Rep 16, 3527 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33404-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33404-w