Abstract

This article examines distance and similarity measures in multidimensional fuzzy sets, which are essential in decision-making and aggregation across various fields. It defines the axioms for multidimensional distance measures and introduces a framework for normalized distance and similarity measures within a suitable fuzzy space. The concept of complement-invariant proximity measures is also discussed. The paper further explores the relationship between distance and similarity, linking them with multidimensional entropy. It presents \(\sigma\)-distance, \(\sigma\)-similarity, and \(\sigma\)-entropy measures that balance values between fuzzy sets and their complements. Finally, two decision-making problems are analyzed, with a comparative study showing the proposed model’s advantage over existing approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fuzzy sets are playing an important part in the growing field of general systems research because of their capacity to describe systems with imprecise components and linkages, which is a feature of many biological and social systems. Most decision-making circumstances, particularly group and multi-criteria scenarios, assign a unique membership value to each element and are difficult due to the inherent ambiguities of the circumstances. One solution to this is to replace the unique membership value with a collection of membership values, as is done in interval-valued fuzzy sets1, hesitant fuzzy sets2,3, m-polar fuzzy sets4, and n-dimensional fuzzy sets5. Another approach is to replace the single membership function with more than one function, as in intuitionistic fuzzy sets6,7 and picture fuzzy sets8. Although certain variations of fuzzy sets such as m-polar, intuitionistic, and n-dimensional models, offer extended flexibility, they often fail to assign membership values precisely based on the unique characteristics of each attribute under study. Likewise, interval-valued and hesitant fuzzy sets present operational complexities that hinder real-world implementation.

Two intriguing fuzzy models are the m-polar fuzzy sets4 and the n-dimensional fuzzy sets5, where each set can independently assign a positive integer representing the number of membership values that an element can assume. However, these models restrict the modification of individual element dimensions according to contextual requirements. This limitation inspired the emergence of multidimensional fuzzy sets (MDFS)9, a modified form of fuzzy sets that allows each element to have an independent number of membership values. In MDFS, each element can be represented with as many values as needed based on its inherent uncertainty, unlike in m-dimensional or m-polar fuzzy sets where all elements are treated equally. Consequently, MDFS provides flexibility by enabling unique and independent dimensional assignments to each element, making it more suitable for modeling heterogeneous real-world data.

The concept of MDFS was introduced and discussed by Annaxsuel and Palmeira9 using a partially ordered set \(\mathcal {I}_\infty ([0, 1])\). Each element can be assigned a specific dimension, offering individualized representation without restricting available knowledge. Compared with other generalized fuzzy models such as type-2 fuzzy sets10, genuine sets11, intuitionistic fuzzy sets12, and interval-valued fuzzy sets1,13, MDFS is more efficient for practical problems because of its simplicity and adaptability. Several applications highlight its usefulness–for instance, an interviewer grading candidates under uncertain judgment, or multiple doctors diagnosing a patient with different conditions–where MDFS can naturally accommodate variable uncertainty levels. Further developments such as multidimensional complements, t-norms, and t-conorms, and properties like De Morgan’s laws have been explored in14.

To analyze differences, similarities, and uncertainty among fuzzy structures, key measures such as distance, similarity, and entropy are essential. A fuzzy distance measure quantifies the dissimilarity between fuzzy sets and was formally established by Liu15. Its complementary notion, the similarity measure, introduced by Wang16, quantifies resemblance between fuzzy data. These concepts have since been extended to multiple fuzzy environments, including bipolar and intuitionistic fuzzy sets17,18. Such measures are widely applied in decision-making, pattern recognition, image processing, and medical diagnostics16,19,20. Therefore, defining and analyzing distance and similarity measures for MDFS is crucial for addressing complex, real-world problems effectively.

Recent research further strengthens this direction. Khan et al.21 proposed an infrared–visible image fusion approach combining knowledge measures for intuitionistic fuzzy sets with the Swin Transformer, while Kumar et al.22 introduced circular intuitionistic fuzzy preference relations for group decision-making. Chen et al.23 developed an intuitionistic fuzzy set-guided fast fusion transformer, and Zhao et al.24 proposed a lightweight infrared–visible image fusion model via adaptive DenseNet. Additionally, Li et al.25 designed new distance and similarity measures for picture fuzzy sets, and Radhakrishnan26 established \(\sigma\)-entropy and \(\sigma\)-similarity for multi-set structures. These works reveal a growing integration of fuzzy measures with computational intelligence, underscoring the need to extend such methodologies to the multidimensional fuzzy framework.

Motivation

Traditional probability theory has long been used to model uncertainty; however, Zadeh’s introduction of fuzziness provided an alternative and more flexible framework. Measuring fuzziness–through entropy, distance, and similarity–remains vital for evaluating uncertainty within fuzzy systems. Entropy quantifies fuzziness within a fuzzy set, as initially formalized by De Luca and Termini using Shannon’s entropy27. Subsequent developments include Ebanks’ five fundamental properties for fuzzy entropy28, Kaufmann’s distance-based approach29, Yager’s negation-based interpretation30, and Liu’s sigma measures15. Despite this rich literature, the study of entropy and similarity measures in the multidimensional fuzzy context remains underexplored. Given that MDFS can represent real-world data more accurately by assigning independent membership values to elements, exploring its associated entropy and similarity measures is essential to close this research gap.

Contributions

This paper extends the notions of distance, similarity, and entropy to multidimensional fuzzy sets (MDFS). It establishes relationships among these measures through theoretical analysis and illustrative examples. Specifically, Section 2 provides essential preliminaries, while Section 3 defines multidimensional distance measures, similarity measures, proximity distances, perfect measures, and linear forms, introducing the concept of crisp approximation using distance measures and \(\sigma\)-based extensions. Section 4 discusses multidimensional entropy, perfect entropy, and \(\sigma\)-entropy. In Section 5, two decision-making applications based on distance and entropy are presented, followed by a comparative study in Section 6 with other fuzzy structures. Overall, the proposed framework contributes to a unified and flexible foundation for analyzing and applying fuzzy measures in multidimensional settings, enhancing both theoretical depth and practical usability.

Distance measures on fuzzy sets

In this section, we concisely review the formal articulation of distance measures on Fuzzy Sets and their multidimensional extensions. These measures quantify the dissimilarity between fuzzy sets, providing a numerical representation of differences in the data. The basic notations and properties of fuzzy sets follow the standard framework given in15.

Fuzzy sets and distance measures

Let \(\mathscr {F}(Y)\) denote the class of all fuzzy sets of Y, and \(\mathscr {P}(Y)\) the class of all crisp sets of Y. Following the formulations in15, we consider \(\mathscr {F}\) as a subclass of \(\mathscr {F}(Y)\) satisfying the usual closure properties.

A fuzzy distance measure \(\hat{d}: \mathscr {F}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) is defined according to the axioms established by Xuecheng15, ensuring reflexivity, symmetry, and consistency with complement and subset relations.

Common examples include the Hamming and Euclidean distances, widely used for quantifying dissimilarity:

Normalized variants of these measures are often employed to keep values within [0, 1]20.

Similarity and entropy measures

Analogous to distance measures, similarity measures \(\hat{s}: \mathscr {F}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) are defined by a corresponding set of axioms15. For continuous fuzzy sets, the parametric similarity measure

provides a flexible method of quantifying resemblance between fuzzy sets.

A fundamental relationship between normalized distance and similarity measures is given by the theorem in15, stating that if \(\hat{d}\) is a normalized distance measure, then \(\hat{s} = 1 - \hat{d}\) is a normalized similarity measure, and vice versa.

Further, \(\sigma\)-similarity measures and entropy functions on fuzzy sets are defined in15, establishing their core properties and interrelations. An example entropy on \(\mathscr {F}(Y)\) is given by

which satisfies the entropy axioms outlined therein.

Discussion

These foundational definitions of fuzzy distance, similarity, and entropy measures15,20 form the basis for their multidimensional generalizations. Their normalized and parameterized versions facilitate consistent comparison and interpretation in both low- and high-dimensional fuzzy environments.

Multidimensional fuzzy sets

Definition 1

9 Let U be a non empty set and given \(r: U \rightarrow \mathbb {N}\). We define the set:

where \(\mu _\mathcal {M}^i: U \rightarrow [0,1]\) satisfies \(\mu _\mathcal {M}^1(y) \le \cdots \le \mu _\mathcal {M}^{r(y)}(y)\) for all \(i=1, \ldots , r(y)\) and for each y \(\in U\). Then the set \(\mathcal {M}\) is called a multidimensional fuzzy set on U.

The \(j^{th}\) membership degree of the element y with respect to the set \(\mathcal {M}\) is given by \(\mu _\mathcal {M}^j(y)\).

Let, \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }\Big ([0,1]\Big )=\bigcup \limits _{n=1}^{\infty } \mathcal {I}_{n}\Big ([0,1]\Big )\) where, \(\mathcal {I}_{n}\Big ([0,1]\Big )= \Big \{(y_1,\) \(\ldots , y_n)\) \(\in [0,1]^n \Big \vert y_1\) \(\le y_2 \le\) \(\cdots\) \(\le y_n\Big \}\)

Hence if \(\mathcal {M}\) is a multidimensional fuzzy set on U, then for each \(y \in U\): \(\left( \mu _\mathcal {M}^1(y), \ldots , \mu _\mathcal {M}^{r(y)}(y)\right) \in \mathcal {I}_{r(y)}\Big ([0,1]\Big ) \subseteq \mathcal {I}_{\infty }\Big ([0,1]\Big )\)

Thus any mdfs \(\mathcal {M}\) on U can be treated as a function from U to \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1]).\)

Let \(\mathcal {|W|}\) denote the natural number \(n \in \mathbb {N}\) such that \(\mathcal {W} \in \mathcal {I}_{n}([0,1])\) called cardinality of \(\mathcal {W}\). For a given \(\mathcal {W} \in \mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\) the \(i^{th}\) component will be denoted by \(w_i\) , \(i \le \mathcal {|W|}\).

Let /w/n denote the element of \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\) which has w in all of their n components, \(w \in [0,1]\).

Let \(\overline{1}=\{/ 1 /m, m\in \mathbb {N}\}, \overline{0}=\{/ 0 /m, m\in \mathbb {N}\},{\dot{1}}\) is an arbitrary element of \(\overline{1}~\text {and}~{\dot{0}}\) is an arbitrary element of \(\overline{0}\).

Let \(\overline{\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}}=\{\mu :U\rightarrow \mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1]):\forall y\in U, \mu (y)=/ 0.5 /m, m\in \mathbb {N}\}\) and \(\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}\) denotes an arbitrary element of \(\overline{\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}}.\)

There are many partial orders available if the elements of \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\) have the same dimension. But we use a natural partial order on \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\) given by:

\(\mathcal {W} \le _{\infty } \mathcal {V} \Leftrightarrow \mathcal {|W|}=\mathcal {|V|}=n\) and

\(\mathcal {W} \le _n^p \mathcal {V}\) where \(\mathcal {V} \le _n^p \mathcal {W}\) is the product order on \(\mathcal {I}_{n}([0,1])\), \(n \in \mathbb {N}\).

Also, if \(\mathcal {M}_1\) and \(\mathcal {M}_2\) are two mdfs we say that \(\mathcal {M}_1 \subseteq \mathcal {M}_2\) if \(\mathcal {M}_1(y)\le _{\infty }\mathcal {M}_1(y)\) for every y.

Standard t-norm and t-conorm for mdfs are defined in14, using two functions, \({F_1}\) and \({F_2}\) as:

-

If \(F_1(\mathcal {V},\mathcal {W})=k\) then:

-

min(\(\mathcal {V},\mathcal {W})=(v_1\wedge w_1, v_2\wedge w_2,\dots , v_k\wedge w_k)\)

-

where \(v_i=w_i=1 \forall i> k\), and

-

If \(F_2(\mathcal {V},\mathcal {W})=l\) then :

-

max(\(\mathcal {V},\mathcal {W})\) = \((v_{n-(l-1)}\vee w_{m-(l-1)}\), \(v_{n-(l-2)} \vee w_{m-(l-2)}\), \(\cdots\), \(v_n\vee w_m\))

-

where \(v_{n-i}=w_{m-j}=0 \forall i\ge n \text { and } j\ge m\).

Now the standard multidimensional complement is given by:

Additional investigations of multidimensional fuzzy sets, particularly concerning multidimensional t-norms, t-conorms, and complements, are documented in14. An innovative rough approximation technique for multidimensional fuzzy sets by integrating rough sets and multidimensional fuzzy sets is presented in31. Further extended to Categorical accommodation of various notions in generalized multidimensional fuzzy sets32. Throughout the remainder of our analysis, we exclusively rely on the intersection, union, and complement operations mentioned above.

Distance and similarity measures of multidimensional fuzzy sets

Distance and similarity measures are fundamental components across various generalized set theories, underpinning applications in decision-making, pattern recognition, and aggregation. Their development reflects the ongoing refinement of quantitative methodologies in fuzzy and multidimensional environments15,33.

Definition 2

Consider a nonempty set \(U\), and let \(\mathbb {F}\) denote the collection of all multidimensional fuzzy sets over \(U\). Within this framework, let \(\mathbb {D} \subset \mathbb {F}\) consist of multidimensional fuzzy sets \(D\) such that \(D(y) \in \overline{1}\) or \(D(y) \in \overline{0}\) for every \(y \in U\). Define \(\mathcal {F} \subseteq \mathbb {F}\) to satisfy:

-

(i)

closure under finite unions and complements,

-

(ii)

\(\overline{\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}} \subseteq \mathcal {F}\),

-

(iii)

\(\mathbb {D} \subseteq \mathcal {F}\).

Distance measure of multidimensional fuzzy sets

Multidimensional fuzzy sets represent a generalized framework that extends traditional fuzzy set theory. Correspondingly, their distance measures generalize classical and intuitionistic fuzzy distances such as the Hamming and Euclidean metrics33.

An intuitionistic fuzzy set \(J\) in a set \(Y\) is defined as:

where \(\mu _J(y)\) and \(v_J(y)\) denote membership and non-membership degrees, satisfying \(0 \le \mu _J(y)+v_J(y) \le 1\), and \(\pi _J(y)=1-\mu _J(y)-v_J(y)\).

For two intuitionistic fuzzy sets \(E\) and \(F\) on \(Y=\{y_1,\dots ,y_n\}\), the Hamming distance is defined as:

and the square of the Euclidean distance is given by:

The axioms governing multidimensional distance measures, adapted from15, ensure properties such as symmetry, reflexivity, maximal separation between complements, and consistency with set inclusion.

Definition 3

A multidimensional distance measure on \(\mathcal {F}\) is a function \(\delta : \mathcal {F} \times \mathcal {F} \rightarrow [0,\infty )\) satisfying:

- (D1):

-

\(\delta (G,H) = \delta (H,G)\)

- (D2):

-

\(\delta (G,G) = 0\) for all \(G \in \mathcal {F}\)

- (D3):

-

\(\delta (D,D^c) \ge \delta (G,H)\) for all \(G,H \in \mathcal {F}\) and \(\forall D \in \mathbb {D}\) whenever:

\(| G(y) | = | H(y) | = | D(y) |\) \(\forall y\)

- (D4):

-

For \(G,H,E \in \mathcal {F}\): if \(G \subseteq H \subseteq E\), then \(\delta (G,H) \le \delta (G,E)\) and

\(\delta (H,E) \le \delta (G,E)\)

Example 1

Discrete distance: Define \(\delta (G, H) = 0\) if \(G = H\), and 1 otherwise. Clearly, \(\delta\) satisfies all the axioms of a distance measure on \(\mathcal {F}\).

The above axiomatic structure provides a consistent mathematical foundation for comparing multidimensional fuzzy sets, ensuring both interpretability and generality across diverse fuzzy frameworks.

Identification of elements in \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\) as infinite sequences

To present pertinent examples of multidimensional distance measures, it is imperative to establish an association between the elements of \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\) and a space where the cardinality of elements does not influence but imparts a distinctive structure to each element.

Definition 4

Let \(\widetilde{\mathcal {I}}_{\infty }([0,1])\) denote the set comprising all sequences with elements from [0,1] and possessing only finitely many nonzero terms. Consider \(\mathcal {Y}=(y_1,...,y_n) \in \mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\). We establish the identification of \(\mathcal {Y}\) with an element of \(\widetilde{\mathcal {I}}_{\infty }([0,1])\), denoted as \(\widetilde{\mathcal {Y}}\), represented by \(\widetilde{\mathcal {Y}}=(0,...,0,y_1,...,y_n,0,0,...)\), where there are precisely \(n-1\) zeros preceding \(y_1\). For any multidimensional fuzzy set A, we denote its corresponding sequential multidimensional fuzzy set as \(\widetilde{A}\), where \(\widetilde{A}(y)=\widetilde{A(y)}\).

It is imperative to emphasize that the equivalence between two sets, \(\mathcal {V}\) and \(\mathcal {W}\), within \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\), is contingent upon the equivalence of their respective closures \(\widetilde{\mathcal {V}}\) and \(\widetilde{\mathcal {W}}\). In other words, \(\mathcal {V}=\mathcal {W}\) if and only if \(\widetilde{\mathcal {V}}=\widetilde{\mathcal {W}}\), where both \(\mathcal {V}\) and \(\mathcal {W}\) belong to the set \(\mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1])\).

Considering the above conditions, we define the following distance measures:

Examples

-

➀

Euclidean Distance: Consider \({U}=\{y_1,y_2,\cdots\), \(y_m\}\) and let A and B be two multidimensional fuzzy sets over U. Let \(\widetilde{A},\widetilde{B}\) denote the corresponding sequential multidimensional fuzzy sets with \(\widetilde{A}(y)=(\widetilde{A}_1(y)\), \(\widetilde{A}_2(y),...)\) and \(\widetilde{B}(y)\) = \((\widetilde{B}_1(y)\), \(\widetilde{B}_2(y)\), ...). Then, we define the Euclidean distance \(d^\infty _e(A, B)\) as:

\(d^\infty _e(A, B)= \sum \limits _{j=1}^m \Bigg ( \sum \limits _{i=1}^\infty \Big \vert \widetilde{A}_i(y_j)-\widetilde{B}_i(y_j) \Big \vert ^2 \Bigg )^{\frac{1}{2}}\)

It is noteworthy that the convergence of the infinite summation in the expression is assured by the finite nature of the nonzero terms constituting the sum.

-

➁

Hamming Distance: The Hamming distance \(\delta ^\infty _h(A\), B) is given by:

$$\begin{aligned} \delta ^\infty _h(A,B)=\sum \limits _{j=1}^m \left( \sum \limits _{i=1}^\infty \Big \vert \widetilde{A}_i(y_j)-\widetilde{B}_i(y_j) \Big \vert \right) \end{aligned}$$ -

➂

The \(p^{th}\) Distance: The \(p^{th}\) distance \(\delta ^\infty _p(A,B)\) is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} \delta ^\infty _p(A,B)=\sum \limits _{j=1}^m \left( \sum \limits _{i=1}^\infty \left( \Big \vert \widetilde{A}_i(y_j)-\widetilde{B}_i(y_j) \Big \vert ^p \right) ^{\frac{1}{p}} \right) \end{aligned}$$where \(p\ge 1\).

-

➃

Supremum Distance: The supremum distance \(\delta ^\infty _s(A,B)\) is expressed as:

$$\begin{aligned} \delta ^\infty _s(A,B)=\sup \left\{ \sum \limits _{i=1}^\infty \Big \vert \widetilde{A}_i(y)-\widetilde{B}_i(y) \Big \vert : y\in {U} \right\} \end{aligned}$$ -

➄

Integral Distance: Assuming \(A_i\) and \(B_i\) are continuous functions for all i, the integral distance \(\delta ^\infty _I(A,B)\) is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} \delta ^\infty _I(A,B)=\sup \left\{ \int _{U} \Big \vert \widetilde{A}_i(y)-\widetilde{B}_i(y) \Big \vert d_y : y\in {U} \right\} \end{aligned}$$

It is noteworthy that among the array of distance measures mentioned earlier, with the exception of the discrete distance measure, none exhibit bounded characteristics. Yet, in practical applications, the imposition of boundedness proves indispensable. Consequently, we delineate a tailored space for multidimensional fuzzy sets, characterized by the following specifications.

Definition 5

Let U be a nonempty set and \(n \in \mathbb {N}\). \(\mathbb {F}_n\) denotes the collection of all multidimensional fuzzy sets over U such that:

It is evident that \(\mathbb {F}_n\) encompasses a broader concept than traditional n-dimensional fuzzy sets, and in most real-life scenarios, a suitable value of n can be determined such that the cardinality of membership values is less than or equal to it.

Definition 6

Let \(\mathbb {D}_n\) denote a subset of \(\mathbb {F}_n\) comprising multidimensional fuzzy sets D with membership values \(D(y) \in \overline{1}\) or \(D(y) \in \overline{0}\) for each y in U. Furthermore, let \(\mathcal {F}_n\) be a subset of \(\mathbb {F}_n\) possessing the following properties:

-

(i)

closed under finite union and complements

-

(ii)

if \(A \in \mathbb {F}_n\) such that \(A(y) = /0.5/m\) for some \(m (1\le m \le n)\) and for all y, then \(A \in \mathcal {F}_n\), and

-

(iii)

\(\mathbb {D}_n \subseteq \mathcal {F}_n\).

Theorem 1

When restricting \(\delta ^\infty _p\) and \(\delta ^\infty _s\) from \(\mathcal {F}\) to \(\mathcal {F}_n\), both measures are bounded.

Proof

It is evident that if \(\Big \vert \textbf{U} \Big \vert = m\), then \(\delta ^\infty _p\) is bounded by \(m(2n-1)\), given that there are m elements in \(\textbf{U}\) and each element can contribute to the first \(2n-1\) positions with non-zero membership values. Similarly, \(\delta ^\infty _s\) is bounded by \((2n-1)\). \(\square\)

Similarity measure of multidimensional fuzzy sets

A crucial tool in analyzing multidimensional fuzzy sets is the similarity measure, which provides insights into the degree of resemblance between two such sets. Complementary to distance measures, similarity measures elucidate the likeness between sets and exhibit a close interrelation with them. The second axiom in our framework underscores the absence of similarity between a set D and its complement \(D^c\) within the domain \(\mathbb {D}\). Fundamentally, it aligns with our intuitive expectation that a multidimensional fuzzy set should exhibit maximum similarity with itself, a notion encapsulated by axiom S3. Additionally, axiom S4 ensures the principle of monotonicity, akin to its counterpart in distance measures.

Definition 7

A multidimensional similarity measure on \(\mathcal {F}\) is a function \(\xi : \mathcal {F} \times \mathcal {F} \rightarrow [0,\infty )\) satisfying the following four axioms:

-

(S1)

\(\xi (G,H) = \xi (H,G)\)

-

(S2)

\(\xi (D,D^c) \le \xi (G,H) \quad \forall G,H \in \mathcal {F}\) and \(\forall D \in \mathbb {D}\) whenever

\(\Big \vert G(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y \Big \vert\) for all y

-

(S3)

\(\xi (G,G) \ge \xi (H,E) \forall G,H,E \in \mathcal {F}\) whenever

\(\Big \vert G(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert E(y) \Big \vert\) for all y

-

(S4)

If \(G,H,E \in \mathcal {F}\) and \(G \subseteq H \subseteq E\), then

\(\xi (G,H) \ge \xi (G,E)\) and \(\xi (H,E) \ge \xi (G,E)\)

It is imperative to acknowledge that akin to distance measures, the boundedness of similarity measures cannot be assumed. As such, to ensure suitability for practical applications, we constrain similarity measures to operate within the realm of \(\mathcal {F}_n\).

Henceforth, we direct our focus exclusively towards normalized distance and similarity measures, achieved by dividing the bounded measures by their respective maximum values. Under this normalization scheme, the ensuing theorem stands:

Theorem 2

Let \(\delta\) be a distance measure, then \(\xi =1-\delta\) is a similarity measure.

Proof

This result directly follows from the definitions of distance and similarity measures. \(\square\)

Theorem 3

If \(\delta\) is a distance measure, then \(\xi = \frac{1}{1 + \delta }\) is a similarity measure.

The subsequent definition encapsulates the desired properties of distance and similarity measures, elucidating essential relationships connecting them.

Definition 8

A distance measure is deemed perfect if \(\delta (D,D^c) = 1\) for all \(D \in \mathbb {D}_n\), while a similarity measure is considered perfect if \(\xi (D,D^c) = 0\) and \(\xi (G,G) = 1\) for all \(D \in \mathbb {D}_n\) and \(G \in \mathcal {F}_n\).

Theorem 4

Let \(\delta\) and \(\xi\) denote distance and similarity measures, respectively, such that \(\delta = 1 - \xi\). Then, \(\delta\) is perfect if and only if \(\xi\) is perfect.

Proof

The proof is straightforward and thus omitted. \(\square\)

A proximity measure is a specialized form of measure that remains invariant under complements, defined as follows:

Definition 9

A distance (similarity) measure is termed a proximity measure if \(\delta (G,H) = \delta (G^c,H^c)\) (consequently, \(\xi (G,H) = \xi (G^c,H^c)\)) holds for \(\forall G,H \in \mathbb {F}\).

Theorem 5

Let \(\delta\) be a distance measure. Then:

is a proximity distance measure.

Proof

To demonstrate that \(\hat{\delta }\) is a distance measure, it suffices to establish the axioms of the distance measure, denoted by \(\hat{D}_1, \hat{D}_2, \hat{D}_3\) and \(\hat{D}_4\)

For \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), it is evident that \(\hat{\delta }(G,H) = \hat{\delta }(G^c,H^c)\). To show that \(\hat{\delta }\) satisfies \(\hat{D}_3\), consider \(E,F \in \mathbb {F}\) and \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) such that \(\Big \vert E(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert F(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y) \Big \vert\) for every y:

For \(D_4\), suppose \(G \subseteq H \subseteq E \Rightarrow E^c \subseteq H^c \subseteq G^c\). Thus, \(\delta (G,H) \le \delta (E,G)\) and \(\delta (H^c,E^c) \le \delta (E^c,G^c)\), implying \(\hat{\delta }(G,H) \le \hat{\delta }(G,E)\). Since:

Similarly, it can be shown that \(\hat{\delta }(H,E) \le \hat{\delta }(G,E)\). \(\square\)

Theorem 6

\(\hat{\delta }(G,H) = \min \{\delta (G,H), \delta (G^c,H^c)\}\) also constitutes a proximity measure.

Example 2

The \(p^{th}\) distance \(\delta _p\) serves as a proximity measure. For instance, if:

Thus, \(\Bigg (\sum \limits _{i=1}^\infty \Big \vert \widetilde{G}_i(y)-\widetilde{H}_i(y)\Big \vert ^p \Bigg )^{\frac{1}{p}} = \Bigg (\sum \limits _{i=1}^\infty \Big \vert \widetilde{G}_i^c(y)-\widetilde{H}_i^c(y)\Big \vert ^p\Bigg )^{\frac{1}{p}} \forall y\) indicating \(\delta _p(G,H) = \delta _p(G^c,H^c)\)

Definition 10

Let G, H, and \(\widehat{\frac{1}{2}} \in \mathcal {F}\) such that \(\Big \vert G(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert (\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y) \Big \vert\) for every y, where \(\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y) = /0.5/m\) for some \(m \in \mathbb {N}\). Then, G and H are considered a similar pair if \(\xi (G,\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}) = \xi (H,\widehat{\frac{1}{2}})\).

It is evident that when \(\xi\) serves as a proximity measure, the sets G and its complement \(G^c\) are similar pair. Extending this notion, we rigorously establish the ensuing theorem.

Theorem 7

If \(\xi\) is a proximity similarity measure, then G and H are a similar pair if and only if \(G^c\) and \(H^c\) are also a similar pair.

Proof

Assume \(\xi\) is a proximity measure. If G and H form a similar pair with respect to \(\xi\), then

since \(\xi\) is a proximity measure.

Hence, \(G^c\) and \(H^c\) also constitute a similar pair. The converse follows similarly. \(\square\)

Definition 11

Let \(\delta\) be a distance measure in \(\mathcal {F}\). A multidimensional fuzzy set \(G \in \mathcal {F}\) is said to be linear if it satisfies the equation \(\delta (G,G^c)=\delta (G,\widehat{\frac{1}{2}})+\delta (G^c,\widehat{\frac{1}{2}})\), where \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y)\Big \vert\) for all y. If every \(G \in \mathcal {F}\) is linear, then \(\delta\) is termed a linear distance measure.

The Hamming distance measure \(\delta ^\infty _h\) is an instance of a linear distance measure.

It is discernible that if \(\delta\) represents a proximity linear distance measure, then for every \(A \in \mathcal {F}\), \(\delta (G, G^c)=2\delta (G,\widehat{\frac{1}{2}})\). The interplay between linear distance measures and multidimensional entropy will be thoroughly investigated in the forthcoming discourse.

While fuzzy sets offer a refined approach to data representation, the process of defuzzification is equally crucial for decision-making. Distance measures play a pivotal role in determining the optimal crisp approximation of a multidimensional set. Hence, we define the crisp approximation of \(A \in \mathcal {F}\) using \(\delta\) as follows:

Definition 12

Let \(G \in \mathcal {F}\). A multidimensional fuzzy set \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) is termed a crisp approximation of G with respect to \(\delta\) if \(\delta (G, D)=\min \{\delta (G,D') \,|\, D' \in \mathbb {D}\}\).

Consider \(\delta ^\infty _p\) as the \(p^{th}\) distance measure. There exist cases where \(G \in \mathcal {F}\) does not possess a unique crisp approximation. For instance, consider \({U}=\{x_1,x_2\}\) and let \(n=2\). Define a 2-dimensional fuzzy set on U as follows:

Now, define \(D'\) and \(D'' \in \mathbb {D}\) as:

Then, \(\delta (G, D')=\delta (G, D'')\) and \(D'\) and \(D''\) are evidently crisp approximations of A.

Theorem 8

Let \(G, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}} \in \mathcal {F}\) such that \(G(y) \le _{\infty } \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y)\) or \(\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y) \le _{\infty } G(y)\) for each y, with strict inequality holding for every y. Then, G possesses a unique crisp approximation with D, respect to \(\delta ^\infty _p\), satisfying the property \(\Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert\) for every y.

Proof

Define \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) as follows:

Clearly, \(\delta (G, D)=\min \{\delta (G,D'),D'\in \mathbb {D}\}\).

Suppose, for contradiction, that there exists \(D' \in \mathbb {D}\) such that \(\delta (G,D)=\delta (G,D')\) and \(D \ne D'\), yet \(\Big \vert D'(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert\) for every y.

Then, there exists \(y \in {U}\) such that \(D(y)\ne D'(y)\). Without loss of generality, assume:

Thus, if \(G(y)=(G_1,...,G_n)\), then:

Similarly, a lower summation value is obtained for D(y) and G(y) compared to \(D'(y)\) and G(y) whenever \(D(y)\ne D'(y)\). Hence, \(\delta (G,D)<\delta (G,D')\), which is a contradiction. \(\square\)

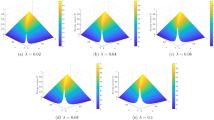

\(\sigma\)-distance measure

The \(\sigma\)-distance measure and \(\sigma\)-similarity measure are specialized metrics distributing distance or similarity equally between multidimensional fuzzy sets and their complements. Subsequently, we introduce \(\sigma\)-entropy measures, which distribute the entropy among each mdfs and crisp mdfs. It will be demonstrated that \(\sigma\)-distance measures and \(\sigma\)-similarity measures yield \(\sigma\)-entropy measures.

Definition 13

A multidimensional distance measure is termed a \(\sigma\)-distance measure if it satisfies \(\delta (G,H)=\delta (G\cap D,H\cap D)+\delta (G\cap D^c,H\cap D^c)\) for every \(G,H \in \mathcal {F}\) and for every \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) whenever \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert H(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all y.

Theorem 9

The \(p^{th}\) distance measure \(\delta ^\infty _p\) is a \(\sigma\)-measure.

Proof

Let \(G, H \in \mathcal {F}\) and \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) be arbitrary, with \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert H(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all \(y\). Select \(y \in {U}\) and, without loss of generality, assume that \(D(y) = /0/n.\) \(\begin{array}{llll} \implies & G(y) \cap D(y) & = & \mathrm{/0/n} \\ & H(y) \cap D(y) & = & \mathrm{/0/n} \\ & G(y) \cap D^c(y) & = & G(y) \qquad \text {and} \\ & H(y) \cap D^c(y) & = & H(y) \end{array}\)

Therefore, the contribution of \(y\) to the sum of \(d^\infty _p(G, H)\) remains unchanged when partitioning the sum into \(d^\infty _p(G\cap D^c, H\cap D^c)\), while the contribution to \(d^\infty _p(G\cap D, H\cap D)\) becomes zero. Thus, the separation of the sum preserves its value, yielding the desired result. \(\square\)

Theorem 10

The supremum distance measure \(\delta ^\infty _s\) is not a \(\sigma\)-measure.

Proof

Let \({U} = \{y_1, y_2\}\), and \(G, H \in \mathcal {F}\) be such that:

Define \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) as:

Consequently, \(\delta ^\infty _s\) does not satisfy the \(\sigma\)-measure property. \(\square\)

Theorem 11

If \(\delta\) is a proximity distance measure, then \(\delta\) is a \(\sigma\)-distance measure if and only if \(\delta (G,H) = \delta (G^c \cup D^c,H^c\cup D^c) + \delta (G^c \cup D^c,H^c\cup D^c)\) for all \(G, H \in \mathcal {F}\) and for every \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) whenever \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert H(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all \(y\).

Proof

The proof follows straightforwardly since the standard t-norm, standard t-conorm, and the standard complement satisfy De Morgan’s laws. Utilizing De Morgan’s law and the proximity property of \(\delta\), we have \(\delta (G\cap D,H\cap D) + \delta (G\cap D^c,H\cap D^c) = \delta (G^c \cup D,H\cup D) + \delta (G^c \cup D^c,H^c\cup D^c)\). Thus, the remainder of the result follows directly. \(\square\)

\(\sigma\)-similarity measure

A multidimensional similarity measure \(\xi\) is defined as a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure if it adheres to the following definition:

Definition 14

For every pair of fuzzy sets \(G\) and \(H\) belonging to the set of fuzzy sets \(\mathcal {F}\), and for every \(D\) belonging to the set of multidimensional sets \(\mathbb {D}\), the equality \(\xi (G,H) = \xi (G \cap D, H \cup D^c) + \xi (G \cap D^c, H \cup D)\) holds whenever \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all \(y\).

Theorem 12

Let \(\xi\) is a perfect similarity measure. Then, \(\xi\) is a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure if and only if it satisfies the equation \(\xi (G,H) = \xi (G \cap D, H \cup D^c) + \xi (G \cup D, H \cap D^c)\) for every pair of fuzzy sets \(G\) and \(H\) in \(\mathcal {F}\), and for every \(D\) in \(\mathbb {D}\), provided that \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all \(y\).

Proof

We demonstrate the sufficiency part; the necessity part follows a similar argument.

Suppose \(\xi (G,H) = \xi (G \cap D, H \cup D^c) + \xi (G \cup D, H \cap D^c)\) for every pair of fuzzy sets \(G\) and \(H\) in \(\mathcal {F}\), and for every \(D\) in \(\mathbb {D}\), provided that \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all \(y\). Then,

where \(D'\) is an element of \(\mathbb {D}\) defined by \(D'(y) = /0/n\) for some \(n\), and \(\Big \vert D'(y)\Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for every \(y\). Consequently, \(\xi (D', {D'}^c) = 0\), and thus:

which proves the result.

\(\square\)

Theorem 13

Let \(\delta\) and \(\xi\) be the perfect distance measure and perfect similarity measure, respectively, such that \(\delta = 1 - \xi\). Then, \(\delta\) is a \(\sigma\)-distance measure if and only if \(\xi\) is a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure.

Proof

Let us assume \(\delta\) to be a \(\sigma\)-distance measure, and denote \(\xi =1-\delta\). We aim to demonstrate that \(\xi\) qualifies as a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure.

Consider two fuzzy sets \(G, H \in \mathcal {F}\), along with a set \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) such that \(\Big \vert G(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert D(y) \Big \vert\) holds for all y. Then, we have:

where \(D'(y)=/0/n\) for all y and for some n with \(\Big \vert D'(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for every y. Similarly, we obtain:

Combining both equations, then we derive:

However, it holds that:

From which, we can deduce:

Hence, \(\xi\) qualifies as a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure. Similarly, it can be shown that if \(\xi\) is a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure, then \(\delta = 1 - \xi\) constitutes a \(\sigma\)-distance measure. \(\square\)

It is noteworthy that the theorem presented above elucidates scenarios wherein \(\sigma\)-similarity measures emanate from \(\sigma\)-distance measures. This observation underscores a fundamental relationship between these two measures within the framework of multidimensional fuzzy set theory.

Entropy of multidimensional fuzzy sets

The entropy component of the proposed framework can be further enriched by integrating the recent developments on entropy measures for specialized fuzzy structures. In particular, the construction methods for entropy measures of circular intuitionistic fuzzy sets provide valuable insights into designing entropy functions that preserve rotational invariance, complement symmetry, and information consistency under uncertainty34. These methods highlight systematic ways to construct entropy measures that align with the axioms of fuzzy uncertainty quantification. Incorporating such approaches within the multidimensional fuzzy set (MDFS) framework can further strengthen the theoretical foundation of \(\sigma\)-entropy measures and enhance their applicability in real-world decision-making and aggregation scenarios. Thus, future work may extend the proposed model by drawing from these circular entropy construction strategies to generalize entropy computations over multidimensional domains.

Definition 15

An entropy on \(\mathcal {F}\) is a function \(\epsilon\): \(\mathcal {F} \rightarrow [0,\infty )\) which satisfies the following axioms:

-

(E1)

\(\epsilon (D)=0,\) \(\forall D \in \mathbb {D}\)

-

(E2)

\(\epsilon (\widehat{\frac{1}{2}})\ge \epsilon (G)\) whenever \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y)\Big \vert \forall y\), \(G\in \mathcal {F}\)

-

(E3)

\(\epsilon (G^c)=\epsilon (G),\) \(\forall G\ in \mathcal {F}\)

-

(E4)

Let \(G, H \in \mathcal {F}\) be such that \(H(y)\le _{\infty } G(y)\le _{\infty } \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y)\)

or \(\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y)\le _{\infty } G(y)\le _{\infty } H(y)\) for every y, then

\(\epsilon (H) \le \epsilon (G)\)

Example 3

Let \(\mathbb {U}=\{y_1,y_2,...y_m\}\) and let \(G \in \mathcal {F}\). Define \(S:\displaystyle \mathcal {I}_{\infty }([0,1]) \rightarrow [0,\infty )\) by:

Then \(\epsilon (G)=\displaystyle \sum \limits _{j=1}^mS(G(y_j))\) is an entropy on \(\mathcal {F}\).

Example 4

Given \(G \in \mathcal {F}\), define \(\hat{G} \in \mathcal {F}\) such that \(\hat{G}(y)=(g_1,...g_n)\) with \(g_i= {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0& \text {if} ~G_i(y)\le 0.5\\ 1& \text {if} ~G_i(y)>0.5 \end{array}\right. }\) Then \(\epsilon ^\infty (G)=1-\delta (G,\hat{G})\) represents an entropy measure, where \(\delta\) denotes a perfect distance measure.

Example 5

For \(G \in \mathcal {F}\), \(\epsilon ^\infty _c(G)=1-\delta (G,G^c)\) defines an entropy measure, where \(\delta\) is a perfect distance measure.

Similar to distance and similarity measures, multidimensional entropy measures may not necessarily be bounded. For instance, consider Example 3.

Definition 16

A multidimensional entropy is termed perfect if \(\epsilon (\widehat{\frac{1}{2}})=1\) for every \(\widehat{\frac{1}{2}} \in \mathcal {F}\).

The subsequent theorem establishes a significant relationship among entropy, similarity measure, and distance measure:

Theorem 14

If s is a perfect similarity measure, then \(\epsilon (G)=\xi (G, G^c)\) represents a perfect entropy. Moreover, if \(\delta\) is a perfect distance measure, then \(\epsilon (G)=1-\delta (G, G^c)\) signifies a perfect entropy.

Proof

The proof immediately follows from the definitions. \(\square\)

Definition 17

Let \(\delta\) be a distance measure and \(\epsilon\) be an entropy measure. We say that \(\epsilon\) is symmetric with respect to \(\delta\) if, for any \(G, H, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}} \in \mathcal {F}\) with \(\Big \vert G(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert H(y) \Big \vert = \Big \vert \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y) \Big \vert\) for all y, the condition \(\delta (G, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y)) = \delta (H, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}(y))\) leads to \(\epsilon (G) = \epsilon (H)\).

Theorem 15

Let \(\delta\) be a perfect linear proximity distance measure. Then, the entropy measure generated by \(\delta\) is symmetric with respect to \(\delta\).

Proof

Suppose \(\delta (G, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}) = \delta (H, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}})\). Consequently, we have \(\delta (G^c, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}}) = \delta (H^c, \widehat{\frac{1}{2}})\). Now, summing up these equations yields:

which simplifies to \(\delta (G, G^c) = \delta (H, H^c)\). This further leads to \(1 - \delta (G, G^c) = 1 - \delta (H, H^c)\), and thus, \(\epsilon (G) = \epsilon (H)\). Consequently, \(\epsilon\) is symmetric with respect to \(\delta\). \(\square\)

\(\sigma\)-entropy measure

Definition 18

An entropy function \(\epsilon\) is termed a \(\sigma\)-entropy measure if it satisfies the condition:

for each \(G\in \mathcal {F}\) and \(D\in \mathbb {D}\) whenever \(\Big \vert G(y)\Big \vert =\Big \vert D(y)\Big \vert\) for all y.

Definition 19

A subset \(\mathbb {E}\subseteq \mathcal {F}\) is considered a comparable class if it adheres to the following criteria:

-

(i)

For every \(G, H \in \mathbb {E}\), either \(G(y)\le _{\infty } H(y)\) or \(H(y)\le _{\infty } G(y)\).

-

(ii)

\(\mathbb {D}\subseteq \mathbb {E}\).

-

(iii)

\(\mathbb {E}\) is closed under finite union and complement.

-

(iv)

\(\overline{\widehat{\frac{1}{2}}}\subseteq \mathbb {E}\).

Theorem 16

Let \(\mathbb {E}\) be a comparable class. Then, an entropy function \(\epsilon\) defined on \(\mathbb {E}\) is a \(\sigma\)-entropy measure if and only if it satisfies the equation:

Proof

Let \(G,H \in \mathbb {E}\) and \(K=\{y\in {U}:H(y)\le _{\infty } G(y)\}\). Define \(D \in \mathbb {D}\) as follows:

Assume that \(\epsilon\) is a \(\sigma\) entropy then:

and

Hence,

Now assume that, \(\epsilon (G)+\epsilon (H)=\epsilon (G\cup H)+\epsilon (G\cap H) \quad \forall G, H \in \mathbb {E}\)

Then,

\(\square\)

Theorem 17

If \(\xi\) is a \(\sigma\)-similarity measure, then the entropy function defined by \(\epsilon (G)=\xi (G, G^c)\) is a \(\sigma\)-entropy measure.

Proof

Consider \(G\in \mathcal {F}\) and \(D\in \mathbb {D}\) then we have;

\(\square\)

Decision making-methods

Multidimensional fuzzy sets have extensive applications across various domains, including decision-making, pattern recognition, and granular computing, providing robust solutions to real-world challenges. Here, we present a methodological framework employing multidimensional distance measures for decision-making in practical scenarios.

Method 1: Decision-making using the weighted euclidean distance measure

In many decision-making scenarios, the evaluation of alternatives depends on multiple qualitative and quantitative attributes, each varying in significance. Typically, these attributes are bounded by a lower threshold \(\zeta\) and an upper threshold \(\eta\), representing the limits of suitability. Since not all attributes contribute equally to the final decision, a weighted approach becomes essential.

Integrating this approach with the MDFS framework enables a robust and structured mechanism for handling complex problems involving multidimensional membership information within the range \([\zeta , \eta ]\). The following algorithm formalizes the process.

This method provides a systematic and interpretable framework for decision analysis under multidimensional uncertainty. By incorporating attribute weights and boundary constraints, decision-makers can obtain more reliable and context-aware results suited to practical applications. The overall workflow of the proposed method is depicted in Fig. 1.

Illustrative example

Consider a scenario where student participants \(P_1\), \(P_2\), and \(P_3\) are evaluated based on multiple attributes (e.g., subject knowledge across disciplines) through interviews. Let \(a_1, a_2,..., a_5\) denote the evaluated attributes. Table 1 specifies the attribute ranges, lower and upper bounds (\(\zeta\), \(\eta\)), and their respective weights (\(w_i\)) on a 0–1 scale.

The corresponding participant attribute values are shown in Table 2. Attributes outside the specified bounds can be directly classified; hence, only bounded cases are considered, with ‘Nil’ indicating missing attributes.

The participant data are represented as multidimensional fuzzy sets:

The computed distances are:

Hence, the ratio values are:

implying the attribute quality ranking \(P_1< P_3 < P_2\).

Entropy-based precision evaluation identifies data fuzziness levels. Participants whose membership values are closer to 0.5 relative to the center boundary (C) exhibit greater uncertainty (see Table 3).

Entropy results:

Thus, \(P_1\) exhibits the least fuzziness and \(P_2\) the highest, indicating that while \(P_2\) has strong attributes, the decision reliability is higher for \(P_1\), whose membership values are closer to mid-boundaries.

Method 2: decision-making using weighted euclidean distance for disease severity assessment

In clinical decision-making, patients afflicted with a disease D may exhibit symptoms of varying intensity. Since the significance of each symptom differs, a weighted distance measure provides a more balanced assessment of disease severity. The following algorithm formalizes the approach.

The corresponding algorithmic workflow is shown in Fig. 2.

Note: The numerical examples presented below are illustrative and not derived from empirical clinical data. Actual parameter values may vary depending on real-world datasets and experimental validation.

Table 4 lists the considered symptoms \(s_i\), their upper bounds \(\zeta _i\), and associated weights. The patient symptom profiles are given as:

The computed distances are:

Thus, the order of disease severity is \(P_1< P_3 < P_2\), corresponding to increasing distance from the upper bounds.

Sensitive analysis

The results in Table 5 indicate that the proposed MDFS-based decision model is highly robust to changes in the weight vector. Even under substantial perturbations–such as over-weighting a single criterion or applying random variations of up to \(\pm 20\%\)–the ranking structure remains effectively unchanged, with \(P_1\) consistently emerging as the top alternative and only minor, non-critical fluctuations observed between \(P_2\) and \(P_3\). This stability demonstrates that the model does not exhibit excessive sensitivity to subjective weight adjustments, reinforcing its reliability for decision-making scenarios.

Computational considerations: cost and implementation notes

From a computational standpoint, both algorithms proposed in this work have tractable complexity when applied to finite multidimensional fuzzy sets. Let m denote the number of elements, n the number of attributes, and \(d_j\) the length of the finite membership tuple associated with element \(x_j\).

-

➀

Algorithm 1 (Evaluating Precision with MDFS): Each element requires two weighted Euclidean distance computations with respect to the lower and upper bounds, resulting in an overall time complexity

$$\begin{aligned} O\!\left( \sum _{j=1}^{m} d_j\right) \approx O(m\bar{d}) \end{aligned}$$Entropy computation has the same order, and memory usage is \(O\!\left( \sum _j d_j\right)\).

-

➁

Algorithm 2 (Disease Severity Assessment): For m entities each characterized by n attributes, the weighted Euclidean distance evaluation requires O(mn) operations, and the subsequent sorting step adds \(O(m\log m)\) time.

The examples presented in this paper are intentionally small and illustrative, as the purpose is to validate theoretical properties rather than to perform empirical benchmarking. Nonetheless, these analyses show that the procedures scale linearly in the number of elements and attributes, confirming their suitability for moderate problem sizes.

Practical implementation aspects include efficient handling of variable-length membership tuples (ragged-array storage), numerically stable weighted distance computation (use of fused multiply–add operations), and careful parameter normalization. For larger datasets, vectorized computation and parallel processing can further improve performance, and these optimizations will be explored in future applied work.

Comparative analysis with existing models

Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) frameworks play a vital role in diverse domains such as medical diagnosis, image processing, and engineering design. However, one of the persistent challenges in these systems is the precise assignment of membership values to each attribute. Classical models like the Weighted Sum Model (WSM), Weighted Product Model (WPM), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), and Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)35,36 often encounter ambiguity and inconsistency during this phase.

The proposed Multidimensional Fuzzy Set (MDFS) model addresses this limitation by allowing each attribute to hold multiple membership values, representing its various aspects and interdependencies. This multidimensional structure enhances expressiveness, preserves data richness, and ensures that uncertainty is modeled more comprehensively.

To demonstrate the superiority of MDFS, this section presents an extended comparison with several existing fuzzy models.

Comparison with intuitionistic fuzzy sets (IFS)

Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets (IFS), introduced by Atanassov, extend classical fuzzy sets by associating each element with both membership and non-membership degrees. The hesitation degree, \(\pi (x) = 1 - \mu (x) - \nu (x)\), captures the uncertainty or incompleteness of information.

In the present study, the dataset representing participants’ performances was converted into IFS form as shown in Table 6. Here, \(\mu (P_i)\) and \(\nu (P_i)\) represent the degree of positive and negative contributions of participant \(P_i\), respectively.

The Euclidean distance measure between each participant’s IFS and the ideal IFS \(I_M = \{(0.72, 0)\}\) was computed as:

The resulting distances indicate the ranking \(P_1< P_3 < P_2\), aligning with the MDFS-based findings. However, it is evident that MDFS yields a larger spread in ranking scores, demonstrating enhanced discriminatory capability and sensitivity to subtle variations among alternatives.

Advantages over IFS are:

-

➀

MDFS eliminates the constraint \(\mu (x) + \nu (x) \le 1\), thereby permitting multidimensional membership evaluation.

-

➁

It supports variable cardinality for each attribute, capturing overlapping or dependent evaluations.

-

➂

It retains richer informational content without normalization-induced loss.

Comparison with fuzzy soft sets (FSS)

Fuzzy Soft Sets (FSS)37,38 are powerful tools for handling parameterized uncertainty. Each element in an FSS is defined with respect to a parameter set, allowing attribute-specific flexibility.

In the current context, each participant \(P_i\) corresponds to a parameter influencing a universal set \(U = \{s_1, s_2, \ldots , s_5\}\). The fuzzy soft sets (F, A) and (G, A) represent observed and ideal data distributions, respectively. The normalized Euclidean metric distance between (F, A) and (G, A) was calculated as:

The obtained weighted distance \(d^w_2((F, A),(G, A)) = 0.0450\) verifies the order \(P_1< P_3 < P_2\), consistent with the MDFS model.

Advantages over FSS are :

-

✯

MDFS captures multi-level uncertainty for each attribute rather than single scalar mappings.

-

✯

The FSS framework requires normalization to compare fuzzy sets, while MDFS inherently preserves scale independence.

-

✯

Attribute interrelations can be represented within MDFS, improving contextual coherence.

Comparison with n-dimensional fuzzy sets

n-Dimensional Fuzzy Sets extend the traditional model by assigning an n-tuple of membership values to each element. This provides limited multi-attribute flexibility but is constrained by a fixed dimension.

In the applied example, the dataset was reduced to three dimensions due to structural limitations, yielding:

After computing distances, the ranking order shifted to \(P_1< P_2 < P_3\), indicating sensitivity to dimensional truncation.

Advantages over n-Dimensional Fuzzy Sets are :

-

✯

mdfs is not restricted by a predefined dimension n; it adapts dynamically to the structure of the dataset.

-

✯

Data loss due to dimensional reduction is eliminated, ensuring integrity and robustness.

-

✯

Enhanced flexibility allows different attributes to have different numbers of membership values.

Comparison with other advanced fuzzy models

Recent extensions of fuzzy theory–such as Pythagorean, q-Rung Orthopair, Picture, and Hesitant Fuzzy Sets–aim to increase expressiveness in uncertainty representation. Despite these advances, they still rely on rigid structural constraints between membership and non-membership functions (e.g., \(\mu ^q + \nu ^q \le 1\)), limiting scalability. The proposed MDFS framework generalizes these models by allowing independent and multidimensional membership representations. This improves the adaptability across diverse applications, particularly where information from multiple evaluators or features must be integrated.

Table 7 presents a comparative summary of major fuzzy set models, highlighting their membership structures, dimensional flexibility, information retention, and computational complexity. Classical, Intuitionistic, Pythagorean, and q-Rung Orthopair fuzzy sets differ primarily in their numerical constraints on membership and non-membership functions, offering increasing expressive power at the expense of higher complexity. Picture fuzzy sets enrich the representation by incorporating neutral judgments, whereas Hesitant fuzzy sets allow multiple possible membership values, providing a very rich but computationally intensive framework. Fuzzy Soft Sets and n-Dimensional Fuzzy Sets introduce parameterization and structured multidimensionality, though typically with fixed dimensional configurations. In contrast, the proposed MDFS model offers variable-size membership tuples, enabling full dimensional flexibility and complete information retention while maintaining scalability. This positions MDFS as a unifying and extensible framework capable of capturing diverse uncertainty structures more efficiently than existing models.

Summary and discussion

The comparative analysis clearly demonstrates that while models like IFS and FSS provide fundamental frameworks for handling uncertainty, they suffer from dimensional rigidity and information loss during transformation. MDFS overcomes these issues by:

-

➀

Supporting arbitrary membership cardinalities for different attributes;

-

➁

Preserving full data dimensionality without requiring normalization;

-

➂

Achieving more discriminative ranking results due to higher sensitivity to attribute variations.

Thus, MDFS offers a generalized, scalable, and information-preserving decision-making framework that subsumes several classical and modern fuzzy set models as its special cases.

Validation analysis and comparative assessment of advantages and disadvantages

To ensure the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed Multidimensional Fuzzy Set (MDFS) framework, a detailed validation was performed based on three essential criteria: consistency, stability, and information preservation. Table 8 summarizes the validation outcomes in comparison with existing fuzzy-based decision-making models.

The comparative analysis of fuzzy-based decision-making models highlights how each framework offers distinct advantages while presenting inherent limitations. Intuitionistic and Fuzzy Soft Sets provide enhanced representational richness but face constraints when handling multidimensional or highly correlated data. The n-Dimensional Fuzzy Set model offers mathematical clarity but lacks flexibility due to its fixed dimensional structure. Pythagorean and q-Rung Fuzzy Sets extend the expressive range of membership modeling, though at the cost of increased computational demand. In contrast, the proposed MDFS framework overcomes these limitations by enabling dynamically scalable dimensionality, preserving information integrity, and accommodating complex, structured uncertainty with significantly improved adaptability and interpretability. A detailed juxtaposition and analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of fuzzy-based decision-making models is presented in Table 9.

The validation analysis confirms that the MDFS framework consistently outperforms existing models in stability, ranking accuracy, and information fidelity. Unlike classical fuzzy approaches that rely on fixed or parameter-dependent dimensions, MDFS dynamically adapts to data complexity, preserving the integrity of multidimensional relationships. Although the computational demand increases with data size, the proposed model’s robustness and adaptability make it highly suitable for real-world applications such as complex decision-making, medical diagnosis, and multi-criteria optimization. Future improvements should focus on optimizing computational efficiency and developing automated parameter-tuning strategies to further enhance scalability.

Conclusions and future works

This study expands the notion of multidimensional fuzzy sets by introducing specialized metrics tailored to their representation, including multidimensional distance measurements, similarity measures, entropy, and crisp approximation techniques. The mdfs offers a precise and robust representation of data by addressing each element individually. However, practical problem-solving with mdfs requires a thorough understanding of the data it represents, prompting an exploration of essential mdfs measures and their characteristics, along with fundamental theorems relating to these metrics. Crisp approximation, facilitated through distance measures, proves valuable for problem-solving within the mdfs framework. Case study analysis highlights the importance of selecting appropriate distance measures for optimal problem-solving. The comparison section underscores the advantages of mdfs in data presentation, emphasizing the need to select the most suitable data presentation method for addressing complex problems. While multidimensional fuzzy sets (MDFS) provide flexible and precise data representation, they face several limitations. The approach involves higher computational complexity, making large-scale applications challenging. Results are sensitive to parameter choices, which can affect accuracy and consistency. Practical usability is limited for non-expert users due to the complexity of measures like distance, similarity, and entropy. Additionally, empirical validation is still insufficient, and existing tools may struggle with highly intricate or dynamic real-world scenarios. Simplification and optimization are needed to enhance accessibility, efficiency, and broader applicability.

To further advance this research area, several future works are proposed. These include delving into more complex measures, optimizing computational efficiency, conducting robustness and sensitivity analyses, extending applicability to dynamic environments, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, refining theoretical analyses, and developing user-friendly software tools. Applying these measures to real-world domains and integrating them into decision-making systems are also highlighted. To be more specific and particular, multidimensional fuzzy sets and distance measures offer a straightforward method for representing real-world data, there exist intricate scenarios beyond current tool capabilities. Recently, mdfs distance measures were utilized to create a hybrid framework known as the Multidimensional measure space, which addresses harder challenges. Future work aims to study continuous functions in multidimensional measure space and investigate distance-based rough approximation methods for mdfs. By pursuing these avenues, researchers aim to enhance the effectiveness and theoretical understanding of distance and similarity measures for multidimensional fuzzy sets, opening up new avenues for applications and advancements in the field. The study presents a generalized and flexible framework for defining distance, similarity, and entropy measures in multidimensional fuzzy sets (MDFS), offering significant advantages over existing fuzzy structures. It enables variable-dimensional membership representation, ensuring better modeling of real-world uncertainty and improved decision-making accuracy. The introduction of normalized, proximity, and \(\sigma\)-measures strengthens consistency and complement invariance, while establishing theoretical links between distance, similarity, and entropy enhances interpretability. However, the approach involves higher computational complexity and sensitivity to parameter choices, which may limit large-scale applications. Additionally, further empirical validation and simplification are needed to enhance practical usability and understanding among non-expert users.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Li, D.-F. Extension principles for interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy sets and algebraic operations. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 10, 45–58 (2011).

Xu, Z. & Zhang, S. An overview on the applications of the hesitant fuzzy sets in group decision-making: Theory, support and methods. Front. Eng. Manag. 6, 163–182 (2019).

Qian, G., Wang, H. & Feng, X. Generalized hesitant fuzzy sets and their application in decision support system. Knowl.-Based Syst. 37, 357–365 (2013).

Kausar, R., Riaz, M., Simic, V., Akmal, K. & Farooq, M. U. Enhancing solid waste management sustainability with cubic m-polar fuzzy cosine similarity. Soft Comput. 1–21 (2023).

Shang, Y.-G., Yuan, X.-H. & Lee, E. S. The n-dimensional fuzzy sets and zadeh fuzzy sets based on the finite valued fuzzy sets. Comput. Math. Appl. 60(3), 442–463 (2010).

Atanassov, K. T. & Gargov, G. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Logics. Springer, (2017).

Yaqoot, I. et al. New similarity measures and topsis method for multi stage decision analysis with cubic intuitionistic fuzzy information. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 42(Preprint), 1–24 (2023).

Cuong, B. C. & Kreinovich, V. Picture fuzzy sets. J. Comput. Sci. Cybern. 30(4), 409–420 (2014).

Lima, A., Palmeira, E. S., Bedregal, B. & Bustince, H. Multidimensional fuzzy sets. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 29(8), 2195–2208 (2020).

Mendel, J. M. Uncertain rule-based fuzzy systems. Introd. New Dir. 684 (2017).

Novák, V. Genuine linguistic fuzzy logic control: powerful and successful control method. In Computational Intelligence for Knowledge-Based Systems Design: 13th International Conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty, IPMU 2010, Dortmund, Germany, June 28-July 2, 2010. Proceedings 13, pp. 634–644 (2010). Springer.

Atanassov, K.T. & Atanassov, K.T. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets. Springer, (1999).

Zeng, W. & Shi, Y. Note on interval-valued fuzzy set. In Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery: Second International Conference, FSKD 2005, Changsha, China, August 27-29, 2005, Proceedings, Part I 2, pp. 20–25 (Springer, 2005).

Josen, J. & John, S. J. Multidimensional fuzzy norms and cut sets in the context of medical decision making. SN Appl. Sci. 5(9), 239 (2023).

Xuecheng, L. Entropy, distance measure and similarity measure of fuzzy sets and their relations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 52(3), 305–318 (1992).

Lee-Kwang, H., Song, Y.-S. & Lee, K.-M. Similarity measure between fuzzy sets and between elements. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 62(3), 291–293 (1994).

Riaz, M., Riaz, M., Jamil, N. & Zararsiz, Z. Distance and similarity measures for bipolar fuzzy soft sets with application to pharmaceutical logistics and supply chain management. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 42(4), 3169–3188 (2022).

Liang, Z. & Shi, P. Similarity measures on intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 24(15), 2687–2693 (2003).

Majumdar, P. & Samanta, S. On similarity measures of fuzzy soft sets. Int. J. Adv. Soft Comput. Appl. 3(2), 1–8 (2011).

Di Pierro, A., Mengoni, R., Nagarajan, R. & Windridge, D. Hamming distance kernelisation via topological quantum computation. In: Theory and Practice of Natural Computing: 6th International Conference, TPNC 2017, Prague, Czech Republic, December 18-20, 2017, Proceedings 6, pp. 269–280 (Springer, 2017).

Khan, M. J., Jiang, S., Ding, W., Huang, J. & Wang, H. An infrared and visible image fusion using knowledge measures for intuitionistic fuzzy sets and swin transformer. Inf. Sci. 684, 121291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2024.121291 (2024).

Kumar, K. coauthors. Group decision making using circular intuitionistic fuzzy preference relations. Expert Systems with Applications (2025) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126502 . defines circular IF preference relations and uses similarity-based additive consistency.

Chen, B. coauthors. Intuitionistic fuzzy set guided fast fusion transformer for image fusion. Symmetry 16(12), 1705 (2024).

Zhao, Z. coauthors. Lightweight infrared and visible image fusion via adaptive densenet with knowledge distillation. Electronics 12(13), 2773 (2023).

Li, H., coauthors. New distance and similarity measures of picture fuzzy sets with applications. International Journal of Computational Intelligence (2025). proposes novel distance/similarity measures applied to pattern recognition and diagnosis

Radhakrishnan, S. Similarity measures, entropy and distance measures of multiple sets. Journal of Fuzzy Extension and Applications (2024). introduces sigma-entropy, sigma-distance and sigma-similarity for multiple-set contexts.

De Luca, A. & Termini, S. A definition of a nonprobabilistic entropy in the setting of fuzzy sets theory. In Read. Fuzzy Sets. Intell. Syst. (eds Bezdek, J. C. et al.) 197–202 (Elsevier, San Diego, CA, 1993).

Ebanks, B. R. On measures of fuzziness and their representations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 94(1), 24–37 (1983).

Kaufmann, A. Introduction to the Theory of Fuzzy Subsets. Academic press, (1975).

Yager, R. R. On the measure of fuzziness and negation part i: membership in the unit interval. International Journal of General Systems (1979).

Josen, J., Mathew, B., John, S. J. & Vallikavungal, J. Integrating rough sets and multidimensional fuzzy sets for approximation techniques: A novel approach. IEEE Access (2024).

Josen, J., John, S. J. & Vallikkavungal, J. Categorical accommodation of various notions in generalized multidimensional fuzzy sets. J. Interdiscip. Math. 28(5), 1955–1971. https://doi.org/10.47974/JIM-2183 (2025).

Wang, W. & Xin, X. Distance measure between intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 26(13), 2063–2069 (2005).

Singh, R., Gupta, P. & Garg, H. Construction methods for entropy measures of circular intuitionistic fuzzy sets and their application. Appl. Intell. 54, 7892–7908 (2024).

Triantaphyllou, E. & Lin, C.-T. Development and evaluation of five fuzzy multiattribute decision-making methods. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 14(4), 281–310 (1996).

Li, D.-F. Multiattribute decision making models and methods using intuitionistic fuzzy sets. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 70(1), 73–85 (2005).

Roy, A. R. & Maji, P. A fuzzy soft set theoretic approach to decision making problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 203(2), 412–418 (2007).

Feng, Q. & Zheng, W. New similarity measures of fuzzy soft sets based on distance measures. Annals. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 7(4), 669–686 (2014).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors, Jomal Josen, Sunil Jacob John, and Jobish Vallikavungal, contributed to the study conception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Josen, J., John, S.J. & Vallikavungal, J. On distance, similarity and entropy measures of multidimensional fuzzy sets. Sci Rep 16, 3525 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33430-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33430-8