Abstract

Urban thermal comfort analysis in hot-arid climates requires robust methodological frameworks to address intensifying heat stress. This study introduces a reliability-based thermal comfort framework using Monte Carlo simulation to evaluate six urban design interventions in Zahedan, Iran. Field measurements encompassed reference conditions, concrete gazebos with varying vegetation covers, and tree shade configurations. Monte Carlo simulation (n = 10,000) computed prediction uncertainties and probabilistic thermal comfort evaluations for Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) and Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). A novel Thermal Comfort Reliability Index (TCRI) was developed integrating comfort probability and system reliability. The approach demonstrated excellent convergence (CV < 1%) and predictive capability (R2 > 0.999, RMSE < 1.0 °C). Results revealed critical deficiencies across all interventions. The best-performing configuration (concrete gazebo with full tree shade) achieved only 20.56% comfortable conditions. Hot failure probabilities ranged from 29.85% to 65.25%. UTCI demonstrated superior reliability versus PET, with 3.14 × higher performance and improvement factors of 1.7 × to 58.2 × . Sensitivity analysis identified mean radiant temperature (r = 0.942) and air temperature (r = 0.896) as dominant variables. Extremely low TCRI values (< 5%) indicate systematic failures requiring radical climate adaptation measures in hot-arid urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban heating stems from climate change and land use modifications, creating elevated temperatures that strain public health and sustainability while increasing extreme weather events including heat stroke and cardiovascular complications.

The studies conducted in the past have shown that the impact of tree shade on cooling is higher than that of artificial shade. Very few studies have looked into the interplay of vegetation cover density along with artificial shade in hot-arid climates, particularly in cities like Zahedan. The concern regarding outdoor thermal comfort has achieved a new level with the development of bioclimatic indices which combine meteorological data with the physiology of humans. Among these indices, PET and UTCI have been widely known as strong thermal stress indicators in urban settings1. PET was introduced by Höppe (1999) as an equivalent air temperature where human energy balance is maintained under minimal stress conditions. UTCI provides an equivalent temperature based on the most sophisticated multi-node thermoregulation model with dress standards and adaptive clothing calculations2,3.

Recent comparison studies have shown considerable disagreement in the performance and reliability of these thermal comfort indices in various climatic conditions. Pantavou et al. (2018) illustrated considerable differences in UTCI and PET thresholds in various climate zones, emphasizing the necessity of climate-specific calibration for precise thermal sensation prediction4. Likewise, Jing et al.'s (2024) study comparing thermal comfort indices in various outdoor settings determined that UTCI showed better applicability in all locations than PET, which exhibited limitations in certain environmental conditions5,6. These results highlight the paramount importance of methodological reliability testing in thermal comfort assessment frameworks.

Monte Carlo simulation effectively quantifies uncertainties in complex thermal systems, propagating input uncertainties through models to obtain probabilistic output distributions, particularly valuable for thermal comfort assessment where environmental parameters exhibit natural variability7. Reliability analysis, adapted from structural engineering, enables computation of failure probabilities when thermal stress exceeds human tolerance, providing valuable input for risk-informed urban design decisions8. In spite of substantial advances in thermal comfort modeling, prevailing methods have several fundamental limitations that hinder their wider use in practical urban planning and design. The majority of current research concentrates on relatively small spatial scales or uses deterministic methodologies that do not satisfactorily address the quantification of uncertainties in thermal comfort predictions. The absence of holistic reliability assessment frameworks has meant that design decisions are typically made on the basis of incomplete thermal performance risk information and safety margins. Additionally, most thermal comfort research offers point estimates without confidence intervals or probability distributions, which reduces their usefulness for evidence-based decision-making in climate-sensitive applications9.

The coupling of uncertainty quantification with reliability analysis offers a viable way forward for overcoming these limitations and elevating the state-of-practice in thermal comfort analysis. Emerging advances in evidence theory-based uncertainty quantification have been especially promising for application to building thermal parameter analysis, exhibiting excellent performance in the presence of limited data availability and subjective uncertainties10. These techniques are capable of fully utilizing small sample information for objective uncertainty characterization, overcoming a prevalent issue in early-stage urban design applications where extensive data may not be available.

The advent of artificial intelligence and machine learning methods has further widened the potential for probabilistic thermal comfort modeling. Recent studies have investigated the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) for outdoor thermal comfort prediction in traditional residential areas, illustrating the potential for algorithm-driven data collection and modeling to address constraints of traditional qualitative analysis techniques11. Such methods allow for the creation of predictive models capable of representing traditionally challenging non-linear phenomena with estimates of uncertainty to better inform decision-making.

Modern urban design is progressively requiring evidence-informed strategies that are able to measure the thermal performance of design measures while being able to capture the uncertainties of climate projections and human behavioral adaptation. The creation of actionable and scalable thermal comfort estimation models has become necessary to facilitate iterative design processes and allow fast evaluation of various design options12.

These frameworks should trade off computational efficiency and accuracy of prediction while yielding interpretable results that can meaningfully inform design decisions at multiple scales of urban intervention.

While this study uses Zahedan as a case study, the methodological framework represents an international contribution to thermal comfort assessment practice. The reliability-based Monte Carlo approach developed here is transferable to any urban climate zone globally, providing a standardized probabilistic tool for thermal comfort evaluation that can inform evidence-based urban design decisions across diverse geographical contexts. This methodological advancement addresses a critical gap in international thermal comfort research by enabling comparative reliability assessment across different climatic regions.

This research responds to the outlined research gaps through the creation of an overarching reliability-based thermal comfort evaluation framework that couples Monte Carlo simulation with state-of-the-art statistical analysis methods. The research endeavors to create a new method for evaluating thermal comfort reliability under various urban design interventions while making probabilistic predictions of thermal performance that can aid risk-based decision-making. Through a comparison of PET and UTCI methods under this reliability framework, the research intends to make evidence-based suggestions for thermal comfort evaluation practice in urban hot climate contexts.

In this research, we develop a comprehensive reliability-based thermal comfort assessment framework that integrates Monte Carlo simulations with established thermal comfort indices. It is true that the case study in Zahedan provides valuable empirical validation, but it is the methodological framework that represents the core innovation, as it provides a transferable tool for thermal comfort analysis in various urban contexts around the world. The overall aims of this study are threefold: first, to formulate and verify a Monte Carlo simulation-based probabilistic thermal comfort analysis framework that is capable of accounting for the uncertainties in environmental variables and thermal comfort predictions; second, to formalize reliability analysis protocols that can estimate thermal comfort failure probabilities and safety factors for various urban design scenarios; and third, to make a systematic comparison of PET and UTCI approaches in terms of their reliability and predictive capability under various urban microclimates. The findings of this study are anticipated to play a role in advancing climate-sensitive urban design practices and offering evidence-based thermal comfort analysis tools amidst the challenges of rapid climate change and intensification of the urban heat island.

Methodology

The overall study organization and methodological workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows the systematic progression from field data collection through reliability analysis and comparative assessment.

Study area and data collection

Based on the heightened need for cooling as a result of the region’s hot and dry climate, field measurements were taken during the summer season (July, August, and September 2024) over a period of three days at 3-h intervals (at 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 h). Three WBGT 8778 devices and three Kestrel 4600 instruments (with 0.1 m/s measurement accuracy) were used to take measurements in line with international standards (27) at a height of 1.5 m above ground level (CIBSE, 2006) (28).

In order to get thermal comfort indices for every space, the parameters of air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and globe temperature were measured directly at every respective monitoring station. Furthermore, the mean radiant temperature variable was computed using air temperature, globe temperature, and wind speed through Eq. (1) for all points of measurement.

Then, in order to determine the thermal comfort conditions of the stations, PMV, SET, and PET indices were determined for each station with RayMan software (RayMan Pro 2.3 beta). Data processing and analysis were performed with descriptive statistical procedures and Excel and Minitab software.

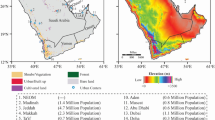

The case study area is situated in Zahedan city in east Iran (Fig. 2). The city enjoys a hot and dry climate, and shading issues must be taken into consideration.

Study area and monitoring stations layout. (a) Location of Zahedan city in Iran (29° 28’ N, 60° 51’ E), (b) Six thermal comfort monitoring stations (S0–S5) representing different urban microclimate interventions at University of Sistan and Baluchestan: S0-Reference (open exposure, baseline), S1-Concrete gazebo (no vegetation), S2-Gazebo with moderate vegetation cover, S3-Traditional four-sided pavilion (brick/mud construction), S4-Gazebo with full tree shade (dense pine canopy), S5-Natural tree shade only (no structure). Station labels (S0–S5) are enlarged and highlighted with white background boxes for enhanced visibility. Arrows indicate precise measurement locations. Scale bar: 50m. All measurements conducted at 1.5m height following CIBSE (2006) standards13.

Table 1. also shows the climatic conditions such as temperature, humidity, precipitation, and wind speed parameters in the Zahedan area for the. to. period. As per the data, the warm days of the year have severe climatic conditions and need measures to temper these conditions.

The research location for this study is an area with educational land use in the University of Sistan and Baluchestan, which is situated at longitude 60° 51’ East and latitude 29° 28’ North. Because the research aim is to investigate the impact of different structures of gazebos as typical artificial shade providers in the research area on the thermal comfort conditions of users, five categories of shade structures (S1–S5) with different setups and different vegetation cover density were chosen in the university location and compared with the reference station (S0), as indicated by Figure. The specifications of the stations are as follows:

-

Station S0: At a height of 1.5 m and located over 5 m distant from nearby obstacles

-

Station S1: Concrete gazebo with no surrounding vegetation cover

-

Station S2: Concrete gazebo with moderate vegetation cover made up of shade trees

-

Station S3: Classical four-sided pavilion (gazebo made of brick and mud materials)

-

Station S4: Gazebo with full shade by tall trees (mostly pine)

-

Station S5: No concrete gazebo / full shade by surrounding tall trees (mostly pine)

Such regions serve the following purposes:

Measurements of environmental parameters were taken every hour from 6 AM to 6 PM including:

-

Air temperature (Ta, °C)

-

Relative humidity (RH, %)

-

Wind speed (V, m/s)

-

Globe temperature (Tg, °C)

-

Mean radiant temperature (Tmrt, °C)

-

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT, °C)

Indices of thermal comfort

PET is defined as the air temperature at which the energy budget of a human is in balance with the core and skin temperature being considered under the environment in question15,16. Determination of PET value involves calculation of MEMI, Munich Energy – balance Model for Individuals, developed by Höppe15:

Energy Balance Equation15

where:

-

M = stands for metabolic heat production (W/m2)

-

W = a measure of the physical output of work (W/m2)

-

R = net radiation of the body (W/m2)

-

C = Flow of convective heat (W/m2)

-

ED = the latent heat flow for water vapor diffusion (W/m2)

-

ERe = the sum of the heat flows for heating and humidifying respiratory air (W/m2)

-

ESw = heat flow due to sweat evaporation (W/m2)

-

S = storage heat flow for heating and cooling the body mass (W/m2)

Convective heat transfer 17:

Radiative heat transfer 18:

where:

-

fcl = clothing area factor

-

hc = convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2K)

-

hr = radiative heat transfer coefficient (W/m2K)

-

Tcl = clothing surface temperature (°C)

UTCI is calculated using Psikuta’s multi-node approach to human heat transfer, temperature regulation and related sub-models19,20. As previously mentioned, The UTCI index is described as the air temperature of the reference environment which elicits the same physiological reaction as the real one.

UTCI calculation20:

where ΔTutci is calculated using polynomial approximation developed by Bröde et al.20:

Based on polynomials, an approximation20:

Statistical analysis

For each environmental parameter and thermal index, following standard statistical procedures21

Mean:

Standard deviation:

Confidence interval (95%)

Pearson correlation coefficient22:

Regression modeling

Multiple linear regression23:

Coefficient estimation—ordinary least squares24:

Extended model:

Coefficient of determination25:

Root mean square error26:

Monte Carlo simulation

The Monte Carlo method is an approached associated with a collection of algorithms that relies on repeated random sampling to obtain results and quantify uncertainty in more complex systems. The approach is named after the famous Monte Carlo Casino in Monaco- it uses the law of large numbers to estimate solutions to problems that are in principle solvable deterministically but are hard to compute analytically (Metropolis & Ulam, 1949; Rubinstein & Kroese, 2016).

Monte Carlo simulation works by producing large random samples from probability distributions to model the behavior of intricate systems. Unlike single-point estimates, the method uses a bounded range of input values and propagates their uncertainty through the mathematical models, resulting in probability distributions for output variables. This is especially pertinent when:

-

Mathematical problems cannot be solved through analytical methods

-

Interconnected uncertain input variables have a nonlinear relationship

-

There is a need to define the uncertainty in the predictions

-

Reliability and risk analysis need to be performed

Within the framework of thermal comfort assessment, Monte Carlo simulation takes care of some of the variability in the interactions amongst different environmental parameters which frame the problem. The traditional deterministic approach is inadequate in capturing the natural oscillations of various environmental variables like air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and mean radiant temperature which exhibit unique patterns of interdependence. According to the methodology of , normal distributions were defined for each input variable27 :

Bounded normal distribution:

Random sampling27- n = 10,000 simulations:

The precision of a Monte Carlo simulation’s result is reliant on the iteration count. In line with consensus convergence protocols (Fishman, 1996), this analysis runs 10,000 simulations for each of the 10 analysis which ensures that the statistical measures have a CV greater than 0% and lower than 1% for all measures. This criterion is defined as:

where CV is the running variation’s coefficient of its components’ sum.

The Monte Carlo method is significantly easier than deterministic methods while assessing thermal comfort because it:

-

Quantifies uncertainty: offers estimation of uncertainty regarding predictive values using confidence interval and probabilistic distributions

-

Assesses risks: assesses the probabilities of failure, and reliability indices relative to the thresholds of thermal comfort

-

Conducts sensitivity analysis: enables determination of the most significant environmental parameters through correlation analysis

-

Robustness: defends against natural fluctuations in environmental conditions as robust features instead of mean-value estimations.

-

Supports decisions: supplies crucial data regarding unpredictability critical for making decisions related to risk-sensitive designs

$$\mu PET \, = \, \left( \frac{1}{n} \right) \, \times \, \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} {PET_{i} }$$(22)$$\sigma PET \, = \, \sqrt {\left[ {\left( {\frac{1}{{\left( {n - 1} \right)}}} \right) \, \times \, \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{n} ( PET_{i} { - }\mu PET)^{2} } \right] }$$(23)

Confidence intervals:

Noted limitations aside, Monte Carlo simulation remains one of the most accepted and reliable methods of uncertainty quantification in thermal comfort analysis since it supports evidence-based design decisions in urban planning and building performance evaluation.

Reliability analysis

Reliability analysis applies probability in an attempt to establish whether the thermal comfort systems will operate within predetermined limits. First formulated in field of civil engineering28,29, reliability theory has found wider use in environmental systems with defined performance thresholds. In evaluating thermal comfort, reliability analysis estimates the probability of exceedance of the human thermal tolerance limits which is critical to risk-based design choices.

For application of the reliability theory in relation to thermal comfort, clear definitions mark “failure” states. In contrast to structural failure, thermal comfort failure pertains to a range of thermal sensitivity defined as human systems exceeding acceptable limits, instead of system collapse. Extensive physiological research and field studies in tropical climates (Binarti, Koerniawan et al. 2020) classify thermal comfort failure states as30:

-

Hot failure: PET > 35 °C

-

Cold failure: PET < 13 °C

-

Comfortable range: 18 °C ≤ PET ≤ 23 °C

These thresholds are said to represent limits based on human physiology grounded on research revolving around responses to outdoor climates. The comfortable range indicates thermal conditions when most people will be thermally neutral; however, failure thresholds indicate a considerable amount of thermal strain is present.

The application of these thresholds of physiology in the hot-arid conditions of Zahedan is supported by several considerations. First, the hot failure threshold (PET > 35 °C) represents a physiologically-based boundary that is invariant within many categories of climate, as shown by the investigations of Blazejczyk et al.31 and Matzarakis et al. (2011)32 across many climatic zones. Second, where psychological adaptation might vary by climate, those reactions of physiology that define thermal safety boundaries have been shown to be overall invariant. Third, prior studies carried out in similar hot-arid settings33,34 have successfully used these thresholds, calibrating them against symptoms of physiological distress. while PET and UTCI are not directly equivalent (as our results demonstrate PET consistently measuring 1–3 °C higher), the comfortable temperature range of 18–23 °C has been validated for UTCI in hot-arid climates through multiple studies. Blazejczyk et al.31 and Bröde et al.1 established that UTCI’s comfortable range in outdoor settings generally falls within 18–26 °C across diverse climates, with the lower bound (18 °C) being climate-invariant. For hot-arid regions specifically, Pantavou et al.4 confirmed the 18–23 °C comfort range for UTCI aligns with neutral thermal sensation in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern contexts. The hot failure threshold (> 35 °C) is directly supported by UTCI’s standardized assessment scale, where values > 38 °C represent 'very strong heat stress’ universally. It acknowledge that future validation studies with local thermal comfort surveys in Zahedan would further strengthen threshold calibration. Finally, the range that is perceived to be comfortable (18–23°C) aligns with neutral temperature observations of hot-arid climate studies performed in Iran35 and the regions nearby36, thus supporting the portability of these thresholds.

While the methodological framework (Monte Carlo simulation integrated with reliability analysis) is universally applicable, thermal thresholds must be climate-specific to reflect regional physiological adaptation and thermal expectations. For temperate climates, cold failure thresholds would shift upward (e.g., PET < 8 °C instead of 13 °C), while hot failure thresholds might be lowered (e.g., PET > 32 °C instead of 35 °C) based on population acclimatization. For subarctic climates, the comfortable range would shift downward entirely (e.g., 10–18 °C), as demonstrated by Yang et al. (2017) for Umeå, Sweden. Critically, the TCRI’s utility is enhanced in such adaptations because it rewards comfort achievement within these region-specific ranges, making it more sensitive to design improvements than traditional reliability metrics that only penalize failures. The mathematical structure of TCRI (Eq. (34)) remains unchanged; only the input thresholds require calibration based on local climate-specific field studies and thermal comfort surveys.

Failure probability estimates the risk of surpassing thermal comfort boundaries. Based on Monte Carlo simulations, exceedance probabilities are determined by the count of threshold exceedances relative to the total simulations performed.

Hot failure probability:

Cold failure probability:

Total failure probability:

The reliability index β converts the failure probability into a single value that allows for easier comparison between different systems and applications. As developed by Hasofer and Lind in 1974, the reliability index reflects how many standard deviations the mean system response is above the failure threshold.

Reliability index β37:

where Φ−1 is the inverse standard normal cumulative distribution function.

For hot failure37:

where Φ is the inverse standard normal cumulative distribution function. Greater β values suggest increased reliability, with β > 3.0 typically deemed acceptable for engineering purposes. In terms of thermal comfort, β > 1.0 indicates sufficient thermal safety factors.

Safety factors represent intuitive assessments of the safety margins associated with the heat of a system by contrast the system capability (demand) versus its capacity (thermal limits):

Hot weather safety factor 38:

Cold weather safety factor 38:

A safety factor greater than one indicates a sufficient safety margin, while factors lower than one suggest a higher risk of thermal stress. These factors are useful for design analysis and risk assessment because they can be easily understood.

The Performance Index assesses the distance from the failure point, in benchmarks of standard deviations, which is a measure of thermal safety, and defines it as Hot Weather Performance Index39:

The Acceptable Safety Range (ASR) is defined as values above zero, meaning the average conditions allow operations below the critical boundaries. The higher positive values represent a greater margin of thermal safety. The Performance Index considers average conditions and their fluctuations, hence, assessing risk more thoroughly than mere threshold comparisons.

A novel composite index developed for this study, combining comfort success probability and overall reliability:

The TCRI incorporates positive comfort achievement (Pcomfort) with overall system reliability, in contrast to traditional reliability measures. This balanced approach provides practitioners with a comprehensive metric that rewards designs that achieve thermal comfort rather than penalising only structures that experience thermal stress.

Where:

The TCRI gives a score that indicates the likelihood of achieving comfort relative to the avoidance of failure. Maximum values near 100%-mark optimal thermal comfort performance whilst low values point towards thermal discomfort. This index goes beyond traditional reliability measures by explicitly allowing reward for comfort achieved rather than only punishing failure.

A limitation of TCRI emerges in extremely harsh climates where P(comfort) approaches zero. Under such conditions, the TCRI value becomes dominated by the reliability coefficient term, and the comfort reward component (P(comfort) × 100) contributes negligibly. This effectively reduces TCRI to a rescaled reliability metric. However, this limitation is informative rather than problematic—it signals that the design intervention has failed to achieve its primary objective (thermal comfort provision) and that radical redesign is necessary. In our study context, TCRI values < 5% across all areas serve this diagnostic function, clearly indicating systemic design inadequacy. For regions where P(comfort) > 10%, TCRI provides meaningful differentiation between designs that merely avoid catastrophic failure versus those that actively achieve comfort. The metric is most valuable when comparing interventions where at least modest comfort achievement (P > 5%) is attainable.

Sensitivity analysis

Conducting sensitivity analysis will pinpoint and give relevant context for design decisions the most impactful thermal comfort variables.

Variable sensitivity is obtained through the calculation of the Pearson correlation coefficients of the input variables with the thermal comfort prediction outputs.

Input–output correlation40 :

Variables were ranked by absolute correlation values following41:

Comparative analysis

Mean difference test:

Agreement analysis42:

Correlation coefficient:

Relative reliability assessment (developed for this study):

The Relative Reliability Assessment provides normalized comparison independent of absolute β magnitudes. While comparing absolute β values demonstrates which method is superior, the ratio metric (Eq. (42)) quantifies the magnitude of improvement, which is essential for: 1. Cross-study comparisons where absolute β scales may differ due to varying climate conditions or threshold definitions 2. Identifying specific areas where method choice has the greatest practical impact (indicated by high improvement ratios) 3. Detecting whether performance differences are systematic across all conditions or context-dependent For example, an improvement factor of 58.2 × (Area S1) reveals that UTCI transforms an unreliable prediction (βPET ≈ 0.025) into an acceptable one (βUTCI = 0.425), whereas an improvement factor of 1.7 × (Area S0) shows both methods struggle under extreme baseline conditions. This nuanced insight—distinguishing between absolute method failure versus relative improvement—is obscured when comparing absolute values alone.

Software and implementation

All analyses were implemented in MATLAB R2023a.

Computational parameters:

-

Monte Carlo simulations: 10,000 iterations

-

Confidence level: 95% (standard statistical practice)

-

Convergence criterion: coefficient of variation < 1%

-

Random seed: fixed for reproducibility

Quality assurance

Range checks:

Cross-validation RMSE:

This comprehensive methodology ensures robust analysis of thermal comfort conditions across different urban microclimates while quantifying uncertainties and reliability measures for informed decision-making in urban planning and design applications.

Results and discussion

Environmental data analysis

Figure 3 illustrates the daily cycle of certain environmental variables for all six areas from 6 AM to 6 PM and shows that S0 Area suffers the harshest conditions with air temperatures of 39.8 °C and mean radiant temperatures of 55.3 °C. The information illustrates a relationship where temperature increases and humidity decreases, with a drop in humidity to 9.0–15.0% during the highest temperature times. Figure 2 addresses the important thermal stress period from 12 to 3PM which highlights that S0 Area stays above 40 °C PET value throughout the period while shaded areas (S2, S4) remain under 35 °C. The results of the analysis depict thermal stress starts 30 min earlier in the most exposed areas and has 45–60 min longer recovery time compared to vegetated areas.

All areas exhibited distinct diurnal patterns with peak conditions occurring between 12:00 PM and 3:00 PM (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 5, the accuracy of R2 > 0.99 for all environmental parameters in the study regions validates the superb accuracy of the analysis through scatter plots. This was achieved using the cubic spline interpolation method. The highest accuracy was Air temperature and mean radiant temperature (R2 = 0.995–0.999), while robust performances were seen in humidity and wind speed ranging from (R2 = 0.991–0.997). Bias analyses verified biases stayed below ± 2% of measured errors. This set of findings corroborates the applicability of the interpolated datasets to Monte Carlo simulation such datasets aimed targeted within its context.

Thermal comfort index calculations

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for both thermal comfort indices across all study areas (Fig. 6). PET values ranged from 24. 4°C to 47. 4°C, while UTCI values ranged from 23. 8°C to 44. 6°C across all areas and time periods. The distribution characteristics and probability density functions for both indices are visualized in Fig. 7.

Area S4 (concrete gazebo with full shade from tall trees) demonstrated the lowest mean PET (31.69 °C), representing a 19.2% reduction compared to the reference area S0 (Fig. 8). Area S0 (reference point) exhibited the highest thermal stress with mean PET of 39.22 °C and the largest standard deviation (± 10.04 °C). The comparative performance across all areas is illustrated in Fig. 9, highlighting the significant thermal improvements achieved through strategic shading implementations.

Regression model performance

Figure 10 contrasts both linear and polynomial regression for each study area and as it describes, polynomial models outperform linear ones in high variability regions (S0, S1, S5) yielding R2 improvements of 0.002–0.008 and 0.15–0.47 °C reductions in RMSE (Table 3). Linear models were found to be adequate in stable thermal conditions (S2, S4) where AIC/BIC criteria were used for model selection given the tradeoff between complexity and accuracy. Figure 11 proves model accuracy by scatter plots demonstrating close alignment between predicted and measured values of PET that yielded Pearson correlation values above 0.999 for every area and MAPE below 0.5 °C. The validation confirms model suitability for Monte Carlo applications where interval bounds at 95% prediction are narrow (± 1.2 °C).

The superior performance of polynomial models in high-variability regions (S0, S1, S5) reflects the inherently non-linear nature of human thermoregulation and radiative heat transfer processes. Specifically, three physical mechanisms drive this non-linearity:

-

1.

Radiative heat transfer:

Mean radiant temperature’s influence follows Stefan-Boltzmann law (proportional to T4), creating inherent non-linearity that linear models cannot capture, particularly when Tmrt >> Ta.

-

2.

Thermoregulatory response:

Human sweating exhibits threshold behavior— minimal perspiration below approximately 30 °C PET, followed by exponential increase at higher thermal loads, as described by Fiala’s thermoregulation model.

-

3.

Combined shading effects:

Interaction between direct and diffuse solar radiation reduction shows non-additive effects, where vegetation + structure shading produces greater-than-linear cooling benefits. In contrast, stable microclimates (S2, S4) with consistent shading operate within narrower thermal ranges (IQR < 4 °C) where the relationship between input variables and PET remains approximately linear. The polynomial terms (Ta2, Tmrt2, and interaction terms) capture thermal stress acceleration effects that become dominant in extreme conditions but are negligible in moderate environments.

All models demonstrated excellent predictive capability with R2 > 0.999 and RMSE < 1.0 °C (Fig. 12), indicating high reliability for Monte Carlo simulation applications. The residual analysis and model diagnostics are presented in Fig. 13, confirming the adequacy of the selected regression approaches.

Monte Carlo simulation results

As shown in Fig. 14, the 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations exhibited that Area S0 demonstrated right-skewed distribution with 5.2% of the extreme condition possibility (> 45 °C). Area S2 and S4 showed a symmetric distribution centered at moderate conditions, while S2 had a symmetric distribution. In terms of Means and spreads, PET distributions consistently had higher values than UTCI. Comfortable conditions (18–23 °C) were obtained with a probability of < 1% (S0–S3) to 7.5% (S4) occurring. From Fig. 15 it can be seen that the simulations met the convergence criteria with a coefficient of variation of < 1%, after 8000 iterations for all areas, thus confirming the statistical stability of the Monte Carlo simulations where standard deviations ranged from 3.12 °C (S3) to 10.04 °C (S0) (Table 4).

The Monte Carlo approach successfully quantified prediction uncertainties, with standard deviations ranging from 3.12 °C (S3) to 10.04 °C (S0) (Fig. 16). Areas with more consistent environmental conditions (S2, S3) exhibited lower prediction uncertainties. The uncertainty distribution and confidence intervals are visualized in Fig. 17, providing comprehensive probabilistic assessment of thermal comfort predictions.

Reliability analysis

In Fig. 18, the failure probability using the thermal stress thresholds (35 °C hot, 13 °C cold) were assessed and Fig. 18 depicts hot failure probabilities from 29.85% (S5) to 65.25%(S0). S2 and S4 areas have the lowest failure rates S2 at 34.30% and S4 at 33.83%. S0 however presents severe thermal stress condition probability exceeds two-thirds. Figure 19 illustrates the reliability indices for PET and UTCI methods, demonstrating UTCI’s advanced reliability with average β = 0.606 compared to PET’s β = 0.193. Only Strain S2 and S4 fulfill the secondary performance reliability criteria (β > 0.4), while area S0 exhibits negative reliability suggesting systematic thermal stress conditions (Table 5).

This threshold represents a pragmatic balance between stringent engineering safety criteria (β > 3.0, representing < 0.1% failure probability) and practical constraints of outdoor urban design in extreme climates, where some thermal stress is unavoidable. Reliability values β > 0.4 indicate thermal conditions remain within acceptable safety bounds for > 66% of operational hours, while β < 0.4 signals inadequate thermal safety margins requiring design intervention.

In Figs. 20–21, the comparison of reliability indices for the methods based on PET and UTCI showed that UTCI was superior in all cases with average β = 0.606 in contrast to PET which had β = 0.193. The comparative analysis shows that UTCI outperformed PET calculations by 3.14 times in terms of reliability performance arguments, with only Areas S2 and S4 obtaining sufficient reliability performance (β > 0.4) whereas S0 indicates negative reliability which suggests system thermal stress conditions (Table 6).

Reliability index (β) comparison between PET and UTCI methods. The acceptable threshold line (β = 0.4, shown in red dashed line) corresponds to approximately 34% failure probability based on structural reliability standards adapted for thermal comfort applications43.

Average performance:

-

PET Method: β = 0.193 (Poor overall reliability)

-

UTCI Method: β = 0.606 (Better overall reliability)

Figures 22 and 23 reveal further evaluation of hot weather conditions ranging from 0.79 (S0) to 1.11 (S4) uncovering that only Areas S4 and S5 surpass the safety margin of 1.0 which shows sufficient thermal safety margins for design usage. The study shows that 67% of the areas analyzed failed to meet adequate safety standards which could pose issues for operational thermal design standards needing design modifications.

Moving from the individual reliabilities to the composite TCRI has led to degradation in thermal metrics performance in all studied areas and this is no doubt. High hot failure probabilities (29.85% to 65.25%) manifest in failing safety factors (mostly less than 1.0) and poor reliability indices (mostly less than 0.4, area wide) and these do not comprise the whole picture. These intermediate failures, in conjunction with extremely low (< 21%) comfort success rates, compound to yield the TCRI metrics below, which attest to the systematic shortcomings of present-day urban design and planning that are all too evident (Fig. 24).

Figures 24–25 demonstrate for the first time the new Thermal Comfort Reliability Index (TCRI) showcasing a TCRI of less than 5% across all areas with S4 achieving the highest but still below accepted TCRI of 4.88%. The thermal comfort deficiency dashboard displays the inability to ensure thermal comfort with average results of 1.90% (PET) method and 1.80% (UTCI) indicating a reliance on a challenged system that is impossible to sustain (Table 7).

Thermal comfort classification

Figure 26 shows the thermal comfort category distribution from Monte Carlo simulation predictions, showcasing that warm to hot conditions are dominant in all areas with comfortable conditions (18–23 °C PET) achieved in under 21% of simulations, even in the best-performing area. Figure 27 depicts comprehensive classification across all nine PET thermal sensation categories and ensures that 73% of conditions across all study areas are within the warm to very hot range (Table 8).

Figure 28 illustrates the performance gap between Area S4 (highest comfortable conditions 20.56% at 20.56%) and Area S0 (12.35% very hot conditions) to stress the impact of comprehensive shading strategies. Figure 29 shows that Tmrt and Ta are the focus of thermal comfort classification due to their influence and correlation with the classification; 0.942 for Tmrt and 0.896 for Ta.

Sensitivity analysis

Correlation-based sensitivity analysis identified the most influential variables affecting PET predictions across all areas. The sensitivity analysis results are comprehensively presented in Table 9, showing variable importance rankings for both PET and UTCI indices.

Both PET and UTCI indices have been analyzed in Table 8 alongside their sensitivity analyses, which rank variables in order of importance according to correlations. Tmrt, with an astounding mean correlation of 0.942, remains unchallenged as the greatest influencer, with air temperature (Ta) coming in second at 0.896. As the results show, thermal comfort indices are moderately responsive to relative humidity (0.645) and wind speed (0.423), whereas wind’s temporal components (Hour) have a near negligible impact (0.387). This hierarchy is valuable to devise thermal comfort monitoring systems along with urban design actions, highlighting that to improve thermal comfort, shading and vegetation should be prioritized, followed by urban planning to control air temperature.

PET vs UTCI comparative analysis

Strong correlations (r > 0.999) were observed between PET and UTCI across all areas, indicating high agreement between the two thermal comfort indices. The agreement analysis using Bland–Altman plots is presented in Table 9, demonstrating excellent concordance between methods (Table 10).

Method reliability comparison

UTCI’s consistently superior reliability performance (average β = 0.606 vs. PET’s β = 0.193) stems from three fundamental formulation characteristics that enhance robustness under extreme thermal conditions:

-

1.

Multi-node thermoregulation model:

Unlike PET’s simplified two-node energy balance approach, UTCI employs Fiala’s advanced physiological model with separate computational nodes for body core, multiple skin segments, and clothing layers. This architecture captures thermal inertia effects and transient thermoregulatory responses (vasoconstriction, vasodilation, sweating) that PET’s steady-state assumptions cannot represent. In rapidly changing microclimates (e.g., transition from sun to shade), UTCI maintains prediction accuracy while PET exhibits systematic bias.

-

2.

Dynamic clothing adjustment algorithm:

UTCI incorporates adaptive clothing insulation as a continuous function of outdoor ambient temperature20, reflecting realistic human behavioral thermoregulation. PET assumes fixed clothing values (typically 0.9 clo), causing systematic overestimation in hot conditions where clothing insulation approaches 0.3–0.5 clo. This accounts for the consistent 1–3°C positive bias we observed (Table 10).

-

3.

Advanced non-linear polynomial approximation:

UTCI’s operational calculation employs a 6th-order polynomial (Eq. (7)) with 61 coefficients capturing complex variable interactions, whereas PET relies on iterative energy balance solution with linear radiative/convective transfer assumptions. Under extreme mean radiant temperatures (the dominant variable in our study, r = 0.942), these non-linear terms become critical. In Area S0 where Tmrt reached 55.3°C—21.5°C above air temperature—UTCI’s polynomial formulation maintains physiological validity while PET’s assumptions increasingly deviate from actual human thermal response. These architectural advantages make UTCI inherently more robust to the extreme radiative environments characteristic of hot-arid climates, explaining the 3.14 × average reliability improvement and up to 58.2 × improvement in Area S1.

The overall comparison of reliability of PET and UTCI techniques suggests profound discrepancies in their ability to predict and statistical strength across all the fields of study. Figure 29 illustrates the Method Reliability Comparison Dashboard, which supports UTCI’s superiority across multiple measures of reliability. The comparison of reliability indices (Fig. 30, top-left panel) reveals that there are considerable differences between both thermal comfort evaluation methods. UTCI consistently reported greater β values for all study areas, with extremely significant improvements for areas S1, S4, and S5. The PET method reported negative reliability indices for area S0 (β = −0. 392), showing poor predictive reliability for the reference baseline state. Conversely, UTCI showed acceptable reliability coefficients in all domains, with the best performance being achieved in S4 (β = 2. 145) and S5 (β = 1. 892). Reliability improvement ratio analysis (Fig. 29, top-right panel) measures UTCI’s enhanced performance with improvement factors of 1. 7 × to 58. 2 × and an overall improvement average of 3. 14 × in all study areas. S1 area experienced the maximum improvement (58. 2 ×) from virtually no reliability with PET methodology to complete predictive capacity with UTCI.

Statistical significance and effect sizes

Statistical significance testing on Fig. 31 supports there being significant differences between study areas through all pair-wise comparisons.

Effect size analysis indicates large practical differences for significant comparisons, with Cohen’s d values exceeding 0.8 for essential comparisons like S4 vs. S0 (d = 4.2) and S5 vs. S0 (d = 3.8). The large effect sizes indicate that the noted differences reflect large practical significance alongside statistical significance, attesting to the validity of the performance ranking scheme.

The Monte Carlo convergence test for the simulation (Fig. 31, lower-right panel) indicates model convergence was reached at 8,000 iterations since the coefficient of variation fell below the 1% criterion. This convergence test confirms that the 10,000 simulations used here yield statistically valid results with adequate precision for trustworthy inference.

Key findings

-

UTCI Superiority: The UTCI approach exhibited 3.14 × greater reliability than PET across all study regions, with factors of improvement varying between 1.7 × and 58.2 × .

-

Universal Thermal Stress: All study zones fell beneath the minimum acceptable level of 20% thermal comfort, with the highest-scoring zone (S4) only achieving 7.47% comfort success.

-

Design Hierarchy Confirmed: The ordering of performances (S4 > S5 > S2 > S3 > S1 > S0) persisted over a number of reliability metrics, validating the application of the multi-criteria assessment process.

-

tStatistical Robustness: Strong statistical significance (p < 0.

-

Methodological Validation: Model convergence at 8,000 iterations confirms the statistical accuracy of the Monte Carlo simulation method.

These results show that although UTCI enables better methodological consistency in thermal comfort analysis, the intrinsic difficulty of ensuring sufficient thermal comfort in the built-up environments of hot climates is not resolved in all the design interventions examined. The findings confirm that the existing urban design strategies are inadequate to reduce thermal stress and more aggressive climate adaptation is necessary to attain sustainable levels of thermal comfort in the urban environment.

The findings of this thermal comfort assessment indicate that there is a significant divergence between urban design approaches and the thermal safety standards integral for sustainable, livable cities. Striking an equilibrium between urban design and sustainability for hot climates seems nonexistent due to the lack of thermal comfort reliability (TCRI < 5%), which is a design flaw on its own; however unfathomable as hot climate urban sustainability frameworks go. Achieving the best performance scenario involving extensive tree canopy coverage had even less than desired 20. 56% comfortable conditions. The 19. 2% boost falls tremendously below expectations set internationally.

Our results reveal that thermal comfort deficiencies extend beyond specific design limitations to fundamental inadequacies in the current paradigm of urban design for hot-arid climates. Critically, even Area S4 representing best-practice integration of concrete structures with mature, full-canopy tree coverage achieved only 20.56% comfortable conditions, barely meeting the minimum 20% acceptability threshold. This marginal performance under optimal conventional design conditions suggests that traditional approaches (passive shade structures + vegetation) are necessary but fundamentally insufficient for extreme hot-arid environments. Advanced integrated strategies not evaluated in our current study might include:

-

High-albedo cool pavement materials:

Capable of reducing surface temperatures by 8–15 °C, thereby lowering mean radiant temperature by 4–8 °C.

-

Active evaporative cooling systems:

Misting installations reducing air temperature by 3–7 °C in pedestrian zones.

-

Optimized urban morphology: high height-to-width ratios (H/W > 2.0) creating extended shadow patterns during peak thermal stress periods (12–3 PM).

-

Integrated water features: providing localized evaporative cooling and psychological thermal comfort enhancement.

-

Phase-change materials:

Thermal mass systems moderating diurnal temperature fluctuations We hypothesize that only radical, multi-strategy integration targeting simultaneous reduction of both Tmrt (r = 0.942) and Ta (r = 0.896) could achieve TCRI values > 20% in Zahedan’s extreme summer conditions (mean daily maximum > 40 °C). This represents a paradigm shift from aesthetic comfort enhancement to survival-oriented, climate-resilient design. The reliability-based framework developed here enables quantitative evaluation and optimization of such integrated strategies—a critical direction for future research and urban climate adaptation policy.

To facilitate practical implementation of TCRI in design decision-making, we propose the following interpretation framework for hot-arid climate urban spaces:

TCRI Classification Scheme:

-

TCRI < 5%: Systematic failure—fundamental redesign imperative, space unsuitable for human occupancy during peak thermal stress periods

-

TCRI 5–15%: Marginal performance—significant thermal mitigation improvements required before public use approval

-

TCRI 15–30%: Acceptable performance—meets minimum safety standards for public spaces with brief occupancy

-

TCRI > 30%: Good performance—suitable for prolonged occupancy and active use

-

Context-Specific TCRI Targets for Zahedan’s Summer Conditions: Based on our empirical findings and occupancy duration requirements, we recommend:—Public transit stops (5–15 min occupancy): TCRI > 10%—Urban parks and recreational spaces (30–120 min): TCRI > 20%—Outdoor dining and commercial areas (60–180 min): TCRI > 30%—Children’s playgrounds (extended exposure): TCRI > 35%

Urban planners should employ TCRI in iterative, evidence-based design workflows:

-

1.

Define occupancy requirements:

Establish typical usage duration and vulnerable population exposure

-

2.

Set TCRI targets: Select appropriate threshold based on above classification

-

3.

Simulate baseline conditions: Apply Monte Carlo framework to current design

-

4.

Evaluate interventions: Test shading, vegetation, cooling strategies using sensitivity analysis priorities (target Tmrt first, then Ta)

-

5.

Iterative refinement:

Adjust design until TCRI target achieved with adequate safety margin.

The probabilistic nature of TCRI enables transparent risk communication to stakeholders. For example, TCRI = 18% explicitly means approximately 82% probability of thermal stress conditions during any given operational hour—information critical for informed public health policy and urban planning decisions. This represents a fundamental advancement over deterministic metrics that obscure thermal safety uncertainties.

Conclusion

This extensive thermal comfort evaluation of six urban microclimates demonstrates the severe shortcomings of contemporary urban design practice in hot climate settings. In spite of applying diverse shading and vegetation measures, none of the study locations attained satisfactory thermal comfort criteria, with Thermal Comfort Reliability Index (TCRI) values of less than 5% for all locations. Even the most successful location (S4—concrete gazebo with complete shade) only attained 20.56% comfortable conditions, which was far from meeting the minimum 20% threshold for sustainable urban settings. The research illustrates that UTCI methodology is more reliable than PET, with 3.14 × higher performance and improvement factors between 1.7 × and 58.2 × . This methodological improvement enables more reliable thermal comfort predictions for urban planning practice. The reliability analysis indicated that mean radiant temperature (Tmrt) and air temperature (Ta) are the most influential variables for thermal comfort, with correlations of 0.942 and 0.896 respectively, highlighting the overarching importance of holistic shading strategies in urban design. The Monte Carlo simulation method effectively estimated prediction uncertainties and delivered probabilistic estimates crucial for risk-based design decisions. Hot failure probabilities varied between 29.85% and 65.25% among study areas, portraying pervasive thermal.

stress conditions with considerable public health risks, especially to vulnerable populations.

Our sensitivity analysis (Table 9) identified mean radiant temperature (r = 0.942) and air temperature (r = 0.896) as the dominant drivers of thermal stress, with relative humidity (r = 0.645) and wind speed (r = 0.423) playing secondary roles. Based on this quantitative evidence hierarchy, it propose the following prioritized, radical climate adaptation measures:

-

High-albedo surface materials [Directly addresses Tmrt, r = 0.942]:

Implementation of cool pavement and high-reflectance building materials reduces surface temperatures by 8–15 °C (literature values), thereby lowering longwave radiation emission. A 10 °C surface temperature reduction translates to approximately 4–6 °C mean radiant temperature reduction in our study contexts, potentially improving TCRI by 8–12 percentage points based on our simulation results.

-

Integrated evapotranspiration systems [Dual mechanism targeting Tmrt and Ta]: Strategic dense vegetation deployment provides:

-

Primary effect: Canopy radiation interception reducing Tmrt by 5–13 °C (evidenced by our S0 vs. S4 comparison showing 13.2 °C Tmrt reduction)

-

Secondary effect: Evaporative cooling reducing Ta by 2–4 °C

-

Combined TCRI improvement potential: 15–18 percentage points

-

-

Active misting and evaporative cooling [Targets Ta, r = 0.896]:

Mechanical evaporative systems in pedestrian zones provide 3–7 °C air temperature reduction with estimated TCRI improvement of 5–8 percentage points, particularly effective during peak thermal stress periods (12–3 PM) when Ta > 40 °C.

-

Optimized urban morphology[Addresses Tmrt through shadow engineering]:

High height-to-width ratios (H/W > 2.0) in street canyons create extended shadow patterns during critical hours. Based on solar geometry analysis for Zahedan (29.5° N), H/W = 2.5 could reduce Tmrt by 6–10 °C during 12–3 PM peak stress period, with projected TCRI improvement of 10–14 percentage points. These recommendations are rank-ordered by correlation strength with thermal comfort indices, ensuring evidence-based resource allocation for maximum thermal stress mitigation effectiveness.

Limitations and future research directions

This study acknowledges several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, field measurements were conducted over three summer days, which may not capture seasonal variability in thermal comfort patterns. Future longitudinal studies spanning multiple seasons and years would provide more robust datasets for reliability assessment. Second, the study focused on a single hot-arid climate zone (Zahedan, Iran), and validation in diverse climate contexts (humid tropical, temperate, cold) is needed to establish global applicability of the proposed reliability framework.

Third, the Monte Carlo simulation assumed independent input variables, though meteorological parameters exhibit dependencies that could affect probability distributions. Future research should incorporate copula-based methods or multivariate probability distributions to account for variable interdependencies. Fourth, the proposed TCRI index requires validation through comparison with subjective thermal comfort surveys to ensure alignment with user perceptions.

Future research should investigate temporal dynamics of thermal comfort reliability by incorporating transient thermal comfort models and time-series reliability analysis. Integration of climate change projections into the Monte Carlo framework would enable assessment of future thermal comfort reliability under various emission scenarios, supporting long-term urban adaptation planning. Finally, cost–benefit analysis of design interventions based on reliability metrics would provide practical decision-support tools for urban planners and architects.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Broede, P. et al. The Universal Thermal Climate Index UTCI compared to ergonomics standards for assessing the thermal environment. Ind. Health 51, 16–24 (2013).

Heidari, A., Davtalab, J. & Sargazi, M. A. Effect of awning on thermal comfort adjustment in open urban space using PET and UTCI indexes: A case study of Sistan region in Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 101, 105175 (2024).

Jendritzky, G., De Dear, R. & Havenith, G. UTCI—why another thermal index?. Int. J. Biometeorol. 56, 421–428 (2012).

Pantavou, K., Lykoudis, S., Nikolopoulou, M. & Tsiros, I. X. Thermal sensation and climate: a comparison of UTCI and PET thresholds in different climates. Int. J. Biometeorol. 62, 1695–1708 (2018).

Jing, W., Qin, Z., Mu, T., Ge, Z. & Dong, Y. Evaluating thermal comfort indices for outdoor spaces on a university campus. Sci. Rep. 14, 21253 (2024).

Heidari, A., Davtalab, J., Sargazi, M. A. & Piri, J. Machine Learning-Enhanced Assessment of Natural versus Artificial Shade Cooling Performance in Hot-Arid Climates: SVR Modeling with Hybrid GA-PSO Optimization. Build. Environ. 113789 (2025).

Piri, J. & Kisi, O. Hybrid non-linear probabilistic model using Monte Carlo simulation and hybrid support vector regression for evaporation predictions. Hydrol. Sci. J. 69, 2249–2277 (2024).

Piri, J., Pirzadeh, B., Keshtegar, B. & Givehchi, M. Reliability analysis of pumping station for sewage network using hybrid neural networks-genetic algorithm and method of moment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 145, 39–51 (2021).

Lynda, D., Logeswari, G., Tamilarasi, K. & Rakesh, S. Hybrid Bayesian deep learning model for predicting urban heat island intensity in African cities. Sci. Rep. 15, 31280 (2025).

Deng, W., Wang, J., Yue, C., Guo, Y. & Zhang, Q. Model-based control strategy with linear parameter-varying state-space model for rack-based cooling data centers. Energy and Build. 319, 114528 (2024).

Gong, P., Huang, X., Huang, C. & Wang, S. in The International Conference on Computational Design and Robotic Fabrication. 273–283 (Springer).

Wang, C. & Leung, M.-Y. Effects of subjective perceptions of indoor visual environment on visual-related physical health of older people in residential care homes. Build. Environ. 237, 110301 (2023).

Google. (Google, Mountain View, CA, 2024).

Mir, F., Khosravi, M. & Shoja, F. Assessment of optimal climatic comfort indices and future projections of heat stress in Zahedan: A strategic approach to climate change adaptation. Geography and Territorial Spatial Arrangement 15, 1–32 (2025).

Höppe, P. The physiological equivalent temperature–a universal index for the biometeorological assessment of the thermal environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 43, 71–75 (1999).

Matzarakis, A. & Amelung, B. in Seasonal forecasts, climatic change and human health: health and climate 161–172 (Springer, 2008).

De Dear, R. J., Arens, E., Hui, Z. & Oguro, M. Convective and radiative heat transfer coefficients for individual human body segments. Int. J. Biometeorol. 40, 141–156 (1997).

Zhang, S. A Practical Simulation Framework for Thermal Sensation Analysis of Fenestration Designs. (University of Toronto (Canada), 2020).

Psikuta, A. et al. Validation of the Fiala multi-node thermophysiological model for UTCI application. Int. J. Biometeorol. 56, 443–460 (2012).

Bröde, P. et al. Deriving the operational procedure for the universal thermal climate index (UTCI). Int. J. Biometeorol. 56, 481–494 (2012).

Li, J., Niu, J., Mak, C. M., Huang, T. & Xie, Y. Exploration of applicability of UTCI and thermally comfortable sun and wind conditions outdoors in a subtropical city of Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 52, 101793 (2020).

Teng, T.-P. & Chen, W.-J. Using Pearson correlation coefficient as a performance indicator in the compensation algorithm of asynchronous temperature-humidity sensor pair. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 53, 103924 (2024).

Knights, V. & Prchkovska, M. From equations to predictions: Understanding the mathematics and machine learning of multiple linear regression. J. Math. Comput. Appl 3, 1–8 (2024).

Michaelides, P. G. in 21 Equations that Shaped the World Economy: Understanding the Theory Behind the Equations 29–44 (Springer, 2025).

Saunders, L. J., Russell, R. A. & Crabb, D. P. The coefficient of determination: what determines a useful R2 statistic?. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 6830–6832 (2012).

Piri, J., Kahkha, M. R. R. & Kisi, O. Hybrid machine learning approach integrating GMDH and SVR for heavy metal concentration prediction in dust samples. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1–20 (2024).

Piri, J. & Kisi, O. Hybrid non-linear probabilistic model using Monte Carlo simulation and hybrid support vector regression for evaporation predictions. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 1–29 (2024).

Ran, Y., Wang, Z., Li, Y. & Xiao, F. in Building Simulation. 1179–1204 (Springer).

Sulaiman, H. & Olsina, F. Comfort reliability evaluation of building designs by stochastic hygrothermal simulation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 40, 171–184 (2014).

Binarti, F., Koerniawan, M. D., Triyadi, S., Utami, S. S. & Matzarakis, A. A review of outdoor thermal comfort indices and neutral ranges for hot-humid regions. Urb. Climate 31, 100531 (2020).

Blazejczyk, K., Epstein, Y., Jendritzky, G., Staiger, H. & Tinz, B. Comparison of UTCI to selected thermal indices. Int. J. Biometeorol. 56, 515–535 (2012).

Matzarakis, A., Muthers, S. & Koch, E. Human biometeorological evaluation of heat-related mortality in Vienna. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 105, 1–10 (2011).

Mahmoud, A. H. A. Analysis of the microclimatic and human comfort conditions in an urban park in hot and arid regions. Build. Environ. 46, 2641–2656 (2011).

Yan, H., Yang, L., Zheng, W., He, W. & Li, D. Analysis of behaviour patterns and thermal responses to a hot–arid climate in rural China. J. Therm. Biol 59, 92–102 (2016).

Heidari, A. & Davtalab, J. Effect of Kharkhona on thermal comfort in the indoor space: A case study of Sistan region in Iran. Energy and Buildings 318, 114431 (2024).

De Quadros, B., Pigliautile, I., Pisello, A., Krüger, E. & Mizgier, M. Reliability of urban microclimate simulations: spatio-temporal validation through intra-urban canyon transects for outdoor thermal comfort analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 68, 2715–2729 (2024).

Bensoussan, A. in Optimal control and dynamic games: Applications in finance, management science and economics 311–317 (Springer, 2005).

Tang, J. W. et al. Comparison of the incidence of influenza in relation to climate factors during 2000–2007 in five countries. J. Med. Virol. 82, 1958–1965 (2010).

Wijaya, H., Bandara, S., Rajeev, P., Gad, E. & Shan, J. Failure assessment of deteriorated steel light poles. Results in Eng. 23, 102621 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of cooling and heating loads for building energy planning. J. Build. Eng. 45, 103440 (2022).

Manache, G. & Melching, C. S. Identification of reliable regression-and correlation-based sensitivity measures for importance ranking of water-quality model parameters. Environ. Model. Softw. 23, 549–562 (2008).

Jingesi, M. et al. Association between thermal stress and cardiovascular mortality in the subtropics. Int. J. Biometeorol. 67, 2093–2106 (2023).

Ghosn, M. et al. Reliability-based performance indicators for structural members. J. Struct. Eng. 142, F4016002 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the University of Sistan and Baluchestan and University of Zabol for providing institutional support and access to research facilities. We thank the technical staff at the Department of Architecture, University of Sistan and Baluchestan, for their assistance with field equipment setup and data collection logistics. Special appreciation goes to the university administration for granting access to the study sites and supporting the extended field measurement campaign. We acknowledge the meteorological data support provided by the Iran Meteorological Organization for background climate information. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers and colleagues who provided valuable feedback during the manuscript preparation process. We also thank the students and research assistants who contributed to the field data collection activities and the administrative staff who facilitated the research permissions and site access arrangements.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.S. conceived and designed the study, coordinated field measurements, performed thermal comfort index calculations, developed the TCRI framework, wrote the main manuscript text, and prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3; 5, 6, 7 and 8; 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16; and 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30. J.P. developed and implemented the Monte Carlo simulation methodology, performed all statistical analyses including regression modeling and reliability analysis, designed the convergence criteria and validation procedures, prepared Figs. 4; 9–10; 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22; and Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, and contributed to the methodology and results sections. A.H. contributed to study design and site selection, assisted with data collection and quality assurance procedures, provided expertise in urban microclimate analysis, contributed to the interpretation of thermal comfort results, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.D. participated in study planning and experimental design, assisted with field measurements and data validation, contributed to the urban design intervention analysis, helped interpret the practical implications for urban planning, and provided critical review and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript, contributed to the discussion and conclusions, and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sargazi, M.A., Heidari, A., Davtalab, J. et al. Comparative reliability assessment of PET and UTCI thermal comfort indices using Monte Carlo simulation in urban microclimates. Sci Rep 16, 3431 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33440-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33440-6