Abstract

Global change and the associated increase in temperature raise serious concerns for the conservation of Antarctic marine biodiversity, which is particularly vulnerable due to the stenothermal nature and highly specialized adaptations of its fauna. Trematomus bernacchii (commonly named emerald rockcod), a Southern Ocean-endemic benthic fish, serves as a valuable model organism for investigating the molecular and physiological impacts of climate change in polar ecosystems. Transposable elements (TEs) are of particular interest, as they are known to become activated under stress and to influence genome plasticity and gene regulation. In this study, we examined the transcriptional response of TEs and their silencing mechanisms in the gills and liver of T. bernacchii specimens exposed to thermal stress (+ 1 °C and + 3 °C compared to a 0 °C control) for 5 and 15 days. Our results showed that temperature increase triggered a transient activation of TEs, followed by the upregulation of silencing-related genes, including members of the Argonaute family, heterochromatin-associated factors, and components of the NuRD complex. Tissue-specific patterns were observed: the liver exhibited a rapid balance between TE activation and silencing, indicating a coordinated and resilient response, while the gills showed a sustained upregulation of both TEs and silencing genes, likely due to their greater sensitivity to environmental changes. These findings highlighted a complex, dynamic interplay between TEs and their regulatory systems under heat stress, offering new insights into early adaptive responses and potential resilience mechanisms in a cold-adapted species facing climate-induced biodiversity loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rates of current global warming have largely exceeded those experienced in the past1,2,3,4 and changes in seawater temperature are expected to occur on a faster time-scale and with a greater magnitude in the Southern Ocean compared to temperate regions. Indeed, the Southern Ocean is one of the hotspots for global warming5,6. Moreover, in Antarctica, the biological cycles of marine organisms are strongly shaped by seasonal abiotic variation, and therefore polar ecosystems could experience a negative impact under the environmental perturbations induced by climate change7,8.

Antarctic fish represent a major component of the biomass in the Southern Ocean, and, in an ecological setting, they are a link between low trophic levels and top predators9,10. Nototheniidae is one of the five Antarctic families belonging to the suborder Notothenioidei11 that is mostly composed of endemic species. They inhabit coastal ecosystems around Antarctica in waters characterized by temperature reaching − 1.9 °C due to the isolation created by the water masses of the Antarctic convergence surrounding the continent12,13. Indeed, the Antarctic continental shelf represents one of the most oceanographically constant environments of the Earth. Antarctic fish have acquired a wide range of adaptations to the cold12,13,14,15, including limited thermal plasticity16,17, enabling survival within a restricted range of temperatures. During 10–14 million years of evolution, the thermal stability of the Antarctic environment has driven the loss of coding genes and regulatory networks required for coping with environmental variability18,19, reducing the adaptive potential of living species20.

In the field of polar biology, Trematomus bernacchii is considered a target species for studying the physiological and biochemical response to environmental changes. This species has a ubiquitous distribution around the Antarctic continent and shows a remarkable abundance21. T. bernacchii has traditionally been described as stenothermic; however, several studies have indicated that this species retains the capacity for thermal acclimation. Davis et al.16 have demonstrated metabolic compensation to warming, suggesting that T. bernacchii can adjust its metabolism under elevated temperatures. Similarly, Enzor and Place17 have reported that oxidative damage and standard metabolic rate exhibit acclimation under warming over time. These findings have indicated that T. bernacchii is not strictly stenothermic and can exhibit thermal plasticity. The acclimation capacity of T. bernacchii has been the subject of many studies22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. In particular, through transcriptomic studies, functional investigations were extended to the layer of gene expression to better understand how the physiological plasticity influences the response of organisms in the face of global climate change. Several papers have reported the inability of T. bernacchii and other notothenioid fishes to mount a heat shock response since no genes encoding heat shock proteins (HSP) (except for Hsp40) were upregulated following thermal exposure31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Nonetheless, microarray analyses have revealed that hundreds of genes related to cellular stress response were differently expressed during recovery from heat exposure, indicating that this kind of reaction to thermal stress was retained in extremely cold-adapted fish31. Using a high-throughput RNA-sequencing approach, Huth and Place32 have further confirmed the general inability of emerald rockcod to mount a heat shock response in liver, brain and gills even if Hsp70 showed a major responsiveness in this latter tissue. In 2016, the same authors33 have reported that a multi-stressor condition induces a strong initial response followed by a return to near basal levels of expression at longer acclimation times. However, a number of key genes remained up-regulated indicating that T. bernacchii has not fully compensated. Although this species could have the physiological plasticity to cope with similar environmental conditions due to climate change, the long-term impacts on populations could reduce growth and reproduction. Recently, the work by Greco and colleagues37 has highlighted in T. bernacchii an increased responsiveness of the brain compared to gills and muscle and an unexpected downregulation of HSPs in neural tissue. These papers have investigated the transcriptomic responses based on genetic pathways evolved by T. bernacchii in response to abiotic variables, particularly thermal stress.

A growing body of literature has underscored the transcriptional responsiveness of transposable elements (TEs) in relation to environmental variability in fish38,39,40,41,42,43. TEs are repetitive sequences that move throughout the genome using a transposition mechanism. TEs can be divided in class I or retroelements if they use an RNA molecule as intermediate during transposition and class II or DNA transposons if they use a DNA molecule for this purpose44. The TE transcriptional activity might be associated with the up- or downregulation of nearby genes through regulatory sequences embedded within TEs or TE-derived noncoding RNAs45,46,47. TEs are domesticated by the host genome to rewire gene expression networks allowing the physiological response of organisms, permitting species adaptation and resilience to cope with the effects of climate change. Although most of the consequences of transposition are neutral48, others can cause genome instability49. Therefore, organisms evolved silencing mechanisms such as those based on the involvement of small RNAs and proteins of the Argonaute superfamily or the KRAB zinc finger proteins and the nucleosome remodeling deacetylase complex (NuRD). These controlling machineries act modulating the heterochromatin status of TE sequences depositing epigenetic marks at DNA and histone levels50.

In this study, we investigated the transcriptional response of TEs and their associated silencing mechanisms in the gills and liver of T. bernacchii exposed to + 1 and + 3 °C with respect to the control temperature (0 °C). The fish gills represent the body part in direct contact with external environment and thus are expected to be sensitive to temperature changes51; the liver hosts a wide variety of pathways included those related to thermoregulation52. Thermal stress induced a transient activation of TEs, followed by the upregulation of silencing mechanisms aimed at preserving genomic stability in T. bernacchii. Notably, the two tissues displayed distinct responses: the liver showed a more coordinated and resilient reaction, whereas the gills displayed sustained upregulation of both TEs and silencing genes throughout the exposure, likely due to their increased sensitivity to temperature fluctuations.

Results

Transposable element composition and sequence divergence in T. bernacchii genome and transcriptomes

The scaffold-level genome assembly of T. bernacchii spans a total of 867.1 Mb. RepeatMasker analysis indicated that transposable elements (TEs) account for 44.02% of the genome, with DNA transposons representing the most prevalent class (21.73%), followed by LINE retrotransposons (9.77%), LTR retrotransposons (3.83%), and SINE retrotransposons (0.37%) (Supplementary Table S1). The TE landscape, based on Kimura distance analysis, exhibited a prominent peak at low K-values, with the majority of TE copies concentrated below a K-value of 25 (Supplementary Fig. S1). The Kimura two-parameter model was used to estimate nucleotide substitutions (transitions and transversions) between each TE copy and its consensus sequence. Low K-values therefore indicate low sequence divergence and are interpreted as evidence of recent insertions.

Transcribed TEs constituted a smaller proportion of the assembled transcriptomes compared to the genomic content. In both liver and gill tissues, the Kimura distance landscapes displayed comparable patterns, characterized by a sharp peak near K = 0 and a secondary elevation at K-values ranging from 20 to 25 (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Transcriptional activity of TEs in T. bernacchii liver and gills

Specimens of emerald rockcod were exposed to temperatures of + 1 °C (T1) and + 3 °C (T3) to simulate future scenarios due to global warming and compared with corresponding control groups sampled after 5 (CT5) and 15 (CT15) days. At each time point, the transcriptional activity of TEs was assessed in liver and gill tissues (Fig. 1). Overall, a substantial transcriptional contribution from DNA transposons and LINE retrotransposons was observed, followed by LTR retrotransposons. In contrast, SINE retrotransposons exhibited generally low expression levels in both tissues under all experimental conditions, exception for the control liver sample at day 5, which showed comparatively higher expression (Fig. 1a). Heatmap analyses revealed distinct TE transcriptional profiles between control and temperature-exposed samples at both time points (5 and 15 days) in both tissues (Fig. 1). Notably, in the liver, TE expression pattern of CT5 was significantly distinct from all other samples including the two exposed groups (Fig. 1a). In the gills, the transcriptional profiles under + 1 °C and + 3 °C were significantly different, but T1 was not significantly different from CT15 and T3 was not significantly different from CT5. CT5 and CT15 were significantly different from each other (Fig. 1b).

Heatmaps of TEs in liver and gill tissues for each experimental and control groups. (a) Liver panel, transcriptional contribution of TEs activity as percentage of mapped reads is reported for the analyzed conditions. (b) Gills panel, transcriptional contribution of TEs activity as percentage of mapped reads is reported for the analyzed conditions. “Unknown” means TEs that are not specifically classified as DNA transposons, LINE, SINE, and LTR retrotransposons; “non-LTR” retrotransposons are referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE or SINE retrotransposons; “Retro” is referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE, SINE, LTR or non-LTR retrotransposons. Statistically significant differences are presented as * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and *** for p < 0.001.

In liver, differential expression analysis allowed the identification of 365 differentially expressed transposable elements (DETEs) in the T1 vs. CT5 comparison, of which 360 were downregulated in the T1 condition. Among these, 124 were LINE retrotransposons, 86 DNA transposons, 64 L retrotransposons, 43 unknown elements, 38 retrotransposons, four SINE retrotransposons, and one non-LTR retrotransposon (Supplementary Table S2). No DETEs were detected in the comparison between CT15 and T3 (Fig. 2).

Volcano plot of differentially expressed TEs (DETEs) between test vs. control for liver samples. The top row shows significant (red) and non-significant (light grey) TEs. In the second row TEs are represented as color-codes by typology (DNA transposons in blue, LINE retrotransposons in coral, LTR retrotransposons in grey, SINE retrotransposons in yellow, Retro in purple, non-LTR retrotransposons in cyan, and unknown in green). Subsequent rows are related to single TE classes. “Unknown” means TEs that are not specifically classified as DNA transposons, LINE, SINE, and LTR retrotransposons; “non-LTR” retrotransposons are referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE or SINE retrotransposons; “Retro” is referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE, SINE, LTR or non-LTR retrotransposons. The blue dashed lines indicate the significant thresholds for Log2 Fold Change >|2|, while the red dashed the statistically significant threshold (p-adj < = 0.05). Light grey plots indicate comparisons for which no DETEs were identified.

In gills, fewer DETEs were identified compared with liver, with most elements showing upregulation (Fig. 3). In the T1 vs. CT5 comparison, 86 DETEs were detected, including 68 upregulated and 18 downregulated elements (Supplementary Table S2). Among the upregulated TEs, 26 were LINE retrotransposons, 15 L retrotransposons, eight DNA transposons, 13 retrotransposons, five unknown elements, and one SINE retrotransposon. The downregulated group included ten LINE retrotransposons, six DNA transposons, and two LTR retrotransposons. The T3 vs. CT15 comparison yielded 138 DETEs, with 122 upregulated and 16 downregulated. Within the upregulated set, 48 were LINE retrotransposons, 24 L retrotransposons, 23 DNA transposons, 16 retrotransposons, seven unclassified, two SINE retrotransposons, and two non-LTR retrotransposons. Among the downregulated elements, LINE retrotransposons (5 elements) were again the most represented, followed by retrotransposons (4 elements), DNA transposons (3 elements), LTR retrotransposons (2 elements), and unknown elements (2 elements) (Supplementary Table S2). Comparisons within each tissue between control time points (CT15 vs. CT5) and between thermal exposures (T3 vs. T1) revealed a limited number of DETEs (Supplementary Table S2).

Volcano plot of differentially expressed TEs (DETEs) between test vs. control for gills samples. The top row shows significant (red) and non-significant (light grey) TEs. In the second row TEs are represented as color-codes by typology (DNA transposons in blue, LINE retrotransposons in coral, LTR retrotransposons in grey, SINE retrotransposons in yellow, Retro in purple, non-LTR retrotransposons in cyan, and unknown in green). Subsequent rows are related to single TE classes. “Unknown” means TEs that are not specifically classified as DNA transposons, LINE, SINE, and LTR retrotransposons; “non-LTR” retrotransposons are referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE or SINE retrotransposons; “Retro” is referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE, SINE, LTR or non-LTR retrotransposons. The blue dashed lines indicate the significant thresholds for Log2 Fold Change >|2|, while the red dashed the statistically significant threshold (p-adj < = 0.05). Light grey plots indicate comparisons for which no DETEs were identified.

When comparing liver and gills, a substantial number of DETEs was observed, primarily involving LINE retrotransposons, followed by DNA transposons and LTR retrotransposons (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2). Downregulated DETEs were predominant in comparisons between control conditions (CT5 and CT15), whereas comparisons between temperature treatments showed a more balanced distribution between up- and downregulated elements.

Volcano plot of differentially expressed TEs (DETEs) between test vs. control for comparisons between liver and gills samples. The top row shows significant (red) and non-significant (light grey) TEs. In the second row TEs are represented as color-codes by typology (DNA transposons in blue, LINE retrotransposons in coral, LTR retrotransposons in grey, SINE retrotransposons in yellow, Retro in purple, non-LTR retrotransposons in cyan, and unknown in green). Subsequent rows are related to single TE classes. “Unknown” means TEs that are not specifically classified as DNA transposons, LINE, SINE, and LTR retrotransposons; “non-LTR” retrotransposons are referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE or SINE retrotransposons; “Retro” is referred to retrotransposons that are not specifically classified as LINE, SINE, LTR or non-LTR retrotransposons. The blue dashed lines indicate the significant thresholds for Log2 Fold Change >|2|, while the red dashed the statistically significant threshold (p-adj < = 0.05).

Transcriptional profiles of genes involved in TE silencing

To better understand the regulation of TEs under thermal stress, we analyzed the expression profiles of key genes implicated in TE silencing pathways. These included components of the RNA interference machinery (e.g., Argonaute subfamily genes), genes encoding proteins involved in heterochromatin formation, and genes encoding epigenetic regulators such as proteins of the NuRD complex.

In the liver, no transcripts corresponding to Ago1 were detected under any conditions. However, transcripts for Ago2, Ago3a, Ago3b, and Ago4 were expressed in both control and test samples. Notably, all four genes exhibited increased expression in the T1 group compared with CT5, whereas expression patterns between CT15 and T3 remained largely comparable (Fig. 5a).

Heatmaps of expression profiles of genes encoding proteins involved in TE silencing in liver and gill tissues. (a) Heatmap based on logarithmic TPM values of Argonaute genes at four experimental conditions in liver. (b) Heatmap based on logarithmic TPM values of genes involved in heterochromatinization at four experimental conditions in liver. (c) Heatmap based on logarithmic TPM values of genes involved in NuRD complex at four experimental conditions in liver. (d) Heatmap based on logarithmic TPM values of Argonaute genes at four experimental conditions in gills. (e) Heatmap based on logarithmic TPM values of genes involved in heterochromatinization at four experimental conditions in gills. (f) Heatmap based on logarithmic TPM values of genes involved in NuRD complex at four experimental conditions in gills. Statistically significant differences are presented as * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and *** for p < 0.001.

Regarding genes associated with heterochromatin formation, expression profiles of control samples (CT5 and CT15) were more closely related than those of exposed groups. Differential expression was observed in both T1 vs. CT5 and T3 vs. CT15 comparisons, with the latter showing more pronounced changes. In particular, an upregulation of cbx1b, cbx5, cbx3a, setdb1b, dnmt3a, and dnmt3b was recorded in T3 relative to CT15 (Fig. 5b). Genes encoding components of the NuRD complex also displayed altered expression between CT5s and T1, whereas no significant differences were detected between CT15 and T3. However, the two thermally stressed groups (T1 and T3) showed broadly similar transcriptional profiles (Fig. 5c).

In the gills, Ago1 transcripts were absent under all conditions. The other Argonaute genes (Ago2, Ago3a, Ago3b, and Ago4) showed differential expression between controls and exposed samples. In the T1 vs. CT5 comparison, all four genes displayed increased transcriptional activity. Moreover, expression patterns of Ago genes were more similar within control groups and within exposed groups than between them (Fig. 5d).

Conversely, genes involved in heterochromatin formation showed similar expression trends between each control and its corresponding exposed group. With the exception of dnmt3b, all analyzed genes were upregulated in T1 relative to CT5 (Fig. 5e).

For genes encoding components of the NuRD complex, expression profiles differed between control and exposed samples, with more marked differences observed between CT5 and T1. Additionally, expression profiles were more similar between the two exposed groups than control conditions (Fig. 5f).

Discussion

Global warming poses a serious threat to Antarctic marine fauna due to the stenothermal nature of the environment and the highly specialized adaptations of its species to cold, stable temperatures. In this context, T. bernacchii, a key benthic fish species endemic of the Southern Ocean, represents an important model organism. Its limited thermal tolerance and evolutionary adaptations to the extreme conditions of the Southern Ocean make it particularly valuable for studying the physiological and ecological consequences of climate change in polar ecosystems. Although numerous studies have investigated the susceptibility of the emerald rockcod to the effects of global warming by analyzing genetic pathways30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, the role of TEs has received comparatively little attention and remains underexplored in this species. This study firstly explores TE expression and related silencing gene responses to thermal stress in an Antarctic fish. TEs are key drivers of genome evolution, capable of influencing gene expression, generating genetic diversity, and facilitating rapid adaptation53,54,55,56. Their activity may be particularly relevant under environmental stress, making them key players in the evolutionary responses of species to climate change53,54,55,56,57,58.

TEs constitute a substantial portion of the T. bernacchii genome, with DNA transposons and LINE retrotransposons being the most represented classes. Moreover, the TE sequence divergence analysis showed a peak at low K values, indicating a recent burst of amplification. Most TE copies were distributed below a K-value of 25, indicating the presence of recently inserted elements. These findings were consistent with observations in other teleost species, including those from non-Antarctic environments, in which DNA transposons and LINE retrotransposons are also the most abundant TE classes and a high proportion of recent insertions is commonly observed59,60,61,62,63.

It is known that organisms exposed to stress conditions may exhibit TE activation and such mobilization can generate genetic variability that provides the raw material for adaptive evolution57,64. Transcriptomic analyses performed in this study revealed active TE expression in the liver and gills of T. bernacchii specimens exposed to thermal stress. In the early phase (day 5), in both tissues, heat exposure induced distinct TE expression profiles compared with control conditions, suggesting a rapid transcriptional response to environmental perturbation. This response was more pronounced in the liver, where a greater number of DETEs was observed than in the gills. These findings highlighted that the two tissues have a distinct response in relation to thermal stress as further supported by the high number of DETEs identified when comparing liver and gills. Interestingly, most DETEs in hepatic tissue were downregulated, whereas those in the gills were predominantly upregulated. Indeed, TE activation is not a generalized process but under stress TE repression may also occur39,64,65,66. It has been proposed that stress often triggers repression of more TEs that it activates, serving as a stabilizing mechanism that balances the potential for genetic innovation with the need to limit genome instability caused by TE activation by stress66. Our analyses revealed that the majority of DETEs belonged to LINE retrotransposons in both tissues. This suggests that LINE retrotransposons were responsive to heat stress in T. bernacchii, indicating a bias towards these elements. Similar associations between specific TE types and stress conditions have been reported in both animal and plant species67,68,69,70,71,72.

A transcriptional response was still detectable in the gills when comparing CT15 and T3 conditions, whereas no DETEs were identified in the liver for the same comparison. The transient yet coordinated modulation of TE expression observed, characterized by early activation followed by later silencing, may reflect a more generalized transcriptional strategy in T. bernacchii in response to thermal stress. This pattern has previously been noted for several canonical gene pathways related to cellular stress and plasticity24,73, and it is further supported by preliminary transcriptomic data showing similar dynamics in immune- and stress-related genes.

Expression of genes involved in TE silencing, particularly Argonaute proteins, chromatin modifiers, and members of the NuRD complex, supported the hypothesis of an active repression mechanism in response to TE mobilization. In both tissues, ago2, ago3a, ago3b, and ago4 were upregulated under stress, particularly at T1. This early transcriptional activation aligns with the observed TE expression profiles and may reflect an immediate counter-regulatory response to TE mobilization. At day 15, expression levels stabilized, especially in the liver, suggesting the establishment of a new regulatory balance after initial perturbation.

Genes involved in heterochromatin formation, such as cbx3a, cbx5, setdb1b, dnmt3a, and dnmt3b, also exhibited significant upregulation, particularly in the liver at T3, indicating reinforcement of transcriptional repression mechanisms at later time points. These epigenetic regulators likely contribute to restoring genome stability following TE activation. The NuRD complex, a key chromatin remodeling factor, showed differential expression in response to thermal stress. The similarity in expression patterns between T1 and T3 samples in both tissues suggested that, once activated, this regulatory complex remains consistently involved in chromatin reorganization under prolonged stress exposure.

Overall, liver and gills exhibited distinct TE responses to thermal stress, emphasizing the importance of tissue-specific regulation in stress adaptation. Although both tissues showed early transcriptional activation at T1, in T3 the liver no longer displayed any differentially expressed TEs compared with its control, suggesting a recovery in hepatic tissue that was not observed in the gills. The liver showed a more coordinated and possibly repressive response to TE activation, the gills exhibited sustained upregulation of TEs and silencing genes, potentially reflecting their direct interface with the external environment and greater sensitivity to temperature fluctuations33.

With due caution, we are confident that the observed results were minimally influenced by housing conditions during the acclimation period. However, it must be acknowledged that the lack of feeding may have influenced the results. Antarctic fish have exceptionally low metabolic rates compared to temperate and tropical species74, and although they are known to feed infrequently during summer and may completely cease feeding during winter, we cannot rule out hunger may still influence specific physiological processes. Stepanowska and Nędzarek75 have reported that up to 50 days of starvation periods caused no significant changes in body weight or chemical composition in two Antarctic species, Notothenia coriiceps and N. rossii. The same authors reported a marked reduction in excretion rates in starved fish, indicating changes in metabolic activity after the first day of starvation, with very limited changes thereafter. This suggests that the fasting period used in our experiment may contribute to some of the temporal differences observed, particularly in the initial phase. However, ensuring frequent nutrition can also increase metabolism at feeding time, temporarily increasing oxygen consumption. It is known that this factor increases the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to the activation of the antioxidant system, which in these fish is very efficient76, and to post-transcriptional regulation77 that may affect the results.

Conclusions

Together, these results suggested that thermal stress in T. bernacchii triggers transient TE activation, followed by upregulation of silencing pathways to restore genomic stability. The observed transcriptional patterns underscore the responsiveness of both the RNA interference machinery and epigenetic regulators to environmental stress, highlighting their critical role in genome defense. The tissue-specific responses further indicated differential regulatory strategies that may be vital for maintaining physiological function under changing environmental conditions. This study sheds light on an underexplored aspect of Antarctic fish biology, suggesting that even in highly cold-adapted fish, TEs and their regulators may contribute to genomic plasticity and stress resilience.

Future research should investigate the long-term effects of TE activation and silencing under chronic stress and explore the potential adaptive significance of these processes in polar fish facing ongoing climate change.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

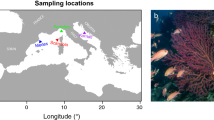

Adult individuals of T. bernacchii (Boulenger, 1902) (n = 12, average length = 23.76 ± 2.99 cm, average weight = 211.92 ± 80.40 g) were sampled at the end of October 2022, from the Ross Sea at Baia Terra Nova (74°42′S, 164°7′E) using hand lines with artificial baits at depths ranging from 60 to 100 m. After capture, the specimens were temporarily kept in buckets and then transported to the aquarium facility of the Mario Zucchelli Italian research station. There, they were housed in aerated 100 L-tanks with a continuous flow of seawater sampled from a depth of 5 m to replicate their native environmental conditions. Fish underwent a five-day acclimation period, during which the water temperature was kept constant at 0.01 ± 0.02 °C, as required by logistical limitations78. The tanks were also covered to reproduce the low-light conditions typical of their natural environment and to avoid stress induced by human presence. During acclimation, fish were not fed; water quality and temperature were monitored to ensure stable and optimal conditions. Recovery was additionally assessed by observing behavioral indicators.

Before the start of the experiment, fish were randomly and equally divided into two tanks, the control and the experimental group. Both were maintained for a total of 15 days in which the control group was set at a constant temperature of 0 °C while the experimental group was initially kept at a 0 °C for one day, followed by a gradual increase of + 1 ± 0.24 °C within 24 h and then maintained at this temperature for four days. Afterwards, the temperature was increased by a further degree and maintained for an additional four days, and finally this was repeated until + 3 ± 0.26 °C was reached over fifteen days. The temperature increase protocol was adapted from previous studies on Antarctic fish79,80. The gradual increase of + 1 °C every four days was implemented both to minimize mortality and to reflect natural thermal dynamics, while also accounting for logistical constraints inherent to Antarctic fieldwork. The selected temperature levels are ecologically relevant: +1 °C is slightly lower than the maximum summer temperature occasionally recorded at Baia Terra Nova (+ 1.5 °C), while + 3 °C is approximately twice this maximum, simulating an acute marine heatwave scenario. These values are consistent with temperature variations measured by multi-parameter probes deployed at 25 m depth in Terra Nova Bay.

At the end of the experiment fish were anesthetised using clove oil (diluted to 50 µL/L) to ensure minimal stress and human handling. Once unresponsive, fish were euthanised by severing the spinal cord following ethical guidelines for animal experimentation. For each fish, the heart was divided immediately after excision, and one portion was allocated for RNA extraction and treated with RNAlater®. The other portion was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C served as backup sample.

Three samples were harvested on the fifth and fifteenth days to obtain biological replicates for both the control (CT5 and CT15) and the experimental group (T1 and T3). Sample collection and animal research methods complied with the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research regulations concerning activities and environmental protection in Antarctica and with the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, Annex II, Art. 3. All the activities on animals performed during the XXXIII Italian Antarctic Expedition were supervised by a PNRA Ethics Referent, acting on behalf of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In particular, the required data for the project identification code PNRA16_00099 are as follows. Name of the ethics committee or institutional review board: Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Name of PNRA Ethics Referent: Dr. Carla Ubaldi, ENEA Antarctica, Technical Unit UTA. All experiments were performed under the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines; EU Directive 2010/63/EU; and Italian DL 2014/26 for animal experiments. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

RNA isolation and sequencing

Total RNA extraction from liver and gill tissues was performed using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of RNA samples was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and assayed for quantity using Qubit™2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and for quality with NanoDrop ™ 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The high-quality RNA biological replicates for tissues and conditions of interest were sent to IGA Tech (IGA Technology Services Srl, Udine, Italy) for sequencing. In all cases, RNA concentrations were > 1 µg/µl, with an RNA integrity number (RIN) > 6. Libraries for RNA-Seq were performed with Zymo-Seq RiboFree Total RNA library preparation kit (Zymo Research) producing paired-end 150 bp raw reads on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) platform. Sequencing data are available in NCBI under BioProject: PRJNA1345203.

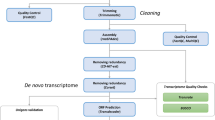

Transcriptional activity and differential expression of TEs

All the RNA-seq raw paired-end data from biological replicates of liver and gill tissues (Supplementary Table S3) were imported into CLC Genomics Workbench v.12 (Qiagen) and trimmed to remove low-quality bases/reads and sequencing adapters using default parameters. De novo transcriptomes were assembled using default parameters and then their completeness was assessed using BUSCO v.5.0.081, with the Actinopterygii OrthoDB v.10 database as reference82.

In order to assess the transcriptional contribution of TEs, we identified TEs in the de novo assembled transcriptome with RepeatMasker v.4.1.0 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/cgi-bin/WEBRepeatMasker, accessed on 10 October 2024), employing a custom TE genome library of T. bernacchii, built as here briefly described. Firstly, the genome of T. bernacchii (accession number GCA_902827165.1) was downloaded from NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/) and a species-specific de novo TE library was constructed following the methods outlined in Carotti et al.59. RepeatScout v.1.0.683 was employed to identify TEs and the resulting “build_lmer_table” was masked using RepeatMasker. Filtering steps were applied to exclude sequences repeated fewer than 10 times and to remove sequences not identified as TEs performing BLASTX84 searches against Uniprot-Swissprot database85 and InterProScan v5-34–73.0.086 using a threshold e-value of 1 × 10− 50. The non-matching elements were further analyzed using HMMER87 to detect integrase, reverse transcriptase, and transposase domains (e-value < 1 × 10− 5). The remaining sequences (excluding simple tandem repeats) were classified using TEclass-2.13 (https://www.bioinformatics.uni-muenster.de/tools/teclass/index.hbi?, accessed on 13 January 2025). The resulting library was used to mask the de novo liver and gill transcriptomes assembled. For the transcribed TE sequences, values obtained from mapping of replicate trimmed reads against the transcriptome were used to calculate their overall contribution as a percentage of mapped reads for each sample (CT5, CT15, T1, T3) and tissue (liver and gills) considered in this study. The results were graphically represented in heatmaps using Rstudio88 packages (readxl89, ComplexHeatmap90, RColorBrewer91, magick92, and circlize93. Statistical analysis was performed in R using the vegan package94. A PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance) was conducted to assess differences in transposon expression patterns among experimental groups, based Euclidean distance matrices and 999 permutations; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

For each tissue, to evaluate the differentially expressed TEs (DETEs), we used TEtranscripts v2.2.395 between pairwise comparisons for each experimental vs. control group, according to the following scheme: T1 vs. CT5, T3 vs. CT15, CT15 vs. CT5, T3 vs. T1. Comparisons between gills vs. liver were performed as follow: gills CT5 vs. liver CT5, gills CT15 vs. liver CT15, gills T1 vs. liver T1, and gills T3 vs. liver T3. For this analysis, the input files included the BAM files of replicates sorted by position using SAMtools96, gene annotation file derived from NCBI (GCF_902827165.1), and TE annotation file generated from RepeatMasker output file. DETEs with Log2 Fold Change > |2| and the statistically significant threshold -Log10 (p-adj) = 0.05 were visualized in Rstudio88 using ggplot297, dplyr98 and patchwork99 packages.

Transcriptional activity of genes involved in TEs silencing

Using TBLASTN84 genes of interest were searched and characterized in the RNA-seq data considered. The set of genes encoding proteins involved in TE controlling systems included: for Argonaute gene subfamily: Argonaute RISC Component 1 (ago1), Argonaute RISC Component 2 (ago2), Argonaute RISC Component 3a (ago3a), Argonaute RISC Component 3b (ago3b), Argonaute RISC Component 4 (ago4); for heterochromatinization: chromobox homolog 1a (cbx1a), chromobox homolog 1b (cbx1b), chromobox homolog 3a (cbx3a), chromobox homolog 3b (cbx3b), chromobox homolog 5 (cbx5), DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 1 (dnmt1), DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 alpha (dnmt3α), DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3beta (dnmt3β) and, SET domain bifurcated histone lysine methyltransferase 1b (setdb1b); for NuRD complex chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 3 (chd3), chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 4a (chd4a), chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 4b (chd4b), histone deacetylase 1b (hdac1b), methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2 (mbd2), methyl-CpG binding domain protein 3a (mbd3a), methyl-CpG binding domain protein 3b (mbd3b), metastasis associated 1 (mta1), metastasis associated 1 family, member 2 (mta2), metastasis associated 1 family, member 3 (mta3), GATA zinc finger domain containing 2Ab (gatad2ab), GATA zinc finger domain containing 2B (gatad2b), retinoblastoma binding protein 4 (rbbp4), retinoblastoma binding protein 7 (rbbp7) and, Tripartite Motif Containing 33 (trim33).

The transcriptional activity values of the considered genes were calculated as Transcript per Million (TPM) and were calculated using the pipeline described in our previous work39 using mapping parameters: length fraction = 0.9 and similarity fraction = 0.9. Logarithmic TPM values were graphically represented in heatmaps using Rstudio88 packages (readxl89, ComplexHeatmap90, RColorBrewer91, magick92, and circlize93. Statistical analysis was performed in R using the vegan package94. A PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance) was conducted to assess differences in gene expression patterns among experimental groups, based on Euclidean distance matrices and 999 permutations; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Kimura distance-based TE age distribution in the genome and transcriptomes of T. bernacchii

The Kimura distance landscapes, representing rates of transitions and transversions, were generated using the “calcDivergenceFromAlign.pl” and “createRepeatLandscape.pl” scripts provided by the RepeatMasker package. This analysis was conducted at the genome level and for expressed TEs identified in the assembled transcriptomes for both liver and gills at control and test conditions (CT5, CT15, T1, T3). This approach was also applied to DETEs obtained using TEtranscripts.

Data availability

RNA-seq data analysed during this study were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers reported in supplementary table S4.

References

Judd, E. J. et al. A 485-million-year history of earth’s surface temperature. Science 385, 6715 (2024).

Fernández-Barba, M., Belyaev, O., Huertas, I. E. & Navarro, G. Marine heatwaves in a shifting Southern ocean induce dynamical changes in primary production. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 404 (2024).

Frölicher, T. L. & Fischer, E. M. Gruber, N. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364 (2018).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1324 (2018).

Frölicher, T. L. et al. Dominance of the Southern ocean in anthropogenic carbon and heat uptake in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 28, 862–886 (2015).

Cai, W. et al. Southern ocean warming and its Climatic impacts. Sci. Bull. 68, 946–960 (2023).

Weiskopf, S. R. et al. Climate change effects on biodiversity, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and natural resource management in the united States. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 137782 (2020).

Dahlke, S. et al. The observed recent surface air temperature development across Svalbard and concurring footprints in local sea ice cover. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 5246–5265 (2020).

Saunders, R. A., Collins, M. A., Stowasser, G. & Tarling, G. A. Southern ocean mesopelagic fish communities in the Scotia sea are sustained by mass immigration. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 569, 173–185 (2017).

Christiansen, H. et al. Diversity of mesopelagic fishes in the Southern ocean: a phylogeographic perspective using DNA barcoding. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6, 120 (2018).

Lecointre, G. Phylogeny and systematics of Antarctic teleosts: methodological and evolutionary issues. (eds di Prisco G, Verde C), Adaptation and evolution in marine environments – the impacts of global change on biodiversity, Vol. 1, From Pole to Pole series, 97–117Springer, Berlin. (2012).

Eastman, J. T. The nature of the diversity of Antarctic fishes. Polar Biol. 28, 93–107 (2005).

Hunt, B. M., Hoefling, K. & Cheng, C. H. C. Annual warming episodes in seawater temperatures in McMurdo sound in relationship to endogenous ice in notothenioid fish. Antarct. Sci. 15, 333–338 (2003).

Cheng, C. H. C. & Detrich, W. H. Molecular ecophysiology of Antarctic notothenioid fishes. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B. 362, 2215–2232 (2007).

Cziko, P. A., Evans, C. W., Cheng, C. H. & DeVries, A. L. Freezing resistance of antifreeze-deficient larval Antarctic fish. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 407–420 (2006).

Davis, B. E. et al. Antarctic Emerald Rockcod have the capacity to compensate for warming when uncoupled from CO₂-acidification. Glob Change Biol. 24, e655–e670 (2018).

Enzor, L. A. & Place, S. P. Is warmer better? Decreased oxidative damage in notothenioid fish after long-term acclimation to multiple stressors. J Exp. Biol. 217, 3301–3310 (2014).

Cocca, E. et al. Do the hemoglobinless icefishes have globin genes? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 118, 1027–1030 (1997).

Somero, G. N. The physiology of climate change: how potentials for acclimatization and genetic adaptation will determine ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 912–920 (2010).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgrò, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485 (2011).

Donnelly, J., Torres, J. J., Sutton, T. T. & Simoniello, C. Fishes of the Eastern Ross Sea, Antarctica. Polar Biol. 27, 637–650 (2004).

Weinstein, R. B. & Somero, G. N. Effects of temperature on mitochondrial function in the Antarctic fish trematomus bernacchii. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 168, 190–196 (1998).

Enzor, L. A., Zippay, M. L. & Place, S. P. High latitude fish in a high CO2 world: synergistic effects of elevated temperature and carbon dioxide on the metabolic rates of Antarctic notothenioids. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 164, 154–161 (2013).

Enzor, L. A., Hunter, E. M. & Place, S. P. The effects of elevated temperature and ocean acidification on the metabolic pathways of notothenioid fish. Conserv. Physiol. 5, 1 (2017).

Bilyk, K. T. & DeVries, A. L. Heat tolerance and its plasticity in Antarctic fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 158, 382–390 (2011).

Peck, L. S., Morley, S. A., Richard, J. & Clark, M. S. Acclimation and thermal tolerance in Antarctic marine ectotherms. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 16–22 (2014).

Jayasundara, N., Healy, T. M. & Somero, G. N. Effects of temperature acclimation on cardiorespiratory performance of the Antarctic notothenioid Trematomus bernacchii. Polar Biol. 36, 1047–1105 (2013).

Sandersfeld, T., Davison, W., Lamare, M. D., Knust, R. & Richter, C. Elevated temperature causes metabolic trade-offs at the whole organism level in the Antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 2373–2381 (2015).

Hudson, H., Brauer, P., Scofield, M. & Petzel, D. Effects of warm acclimation on serum osmolality, cortisol and hematocrit levels in the Antarctic fish, Trematomus bernacchii. Polar Biol. 31, 991 (2008).

Giuliani, M. E., Nardi, A., Di Carlo, M., Benedetti, M. & Regoli, F. Transcriptional and catalytic responsiveness of the Antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii antioxidant system toward multiple stressors. Antioxid. (Basel Switzerland). 10, 410 (2021).

Buckley, B. A. & Somero, G. N. cDNA microarray analysis reveals the capacity of the cold-adapted Antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii to alter gene expression in response to heat stress. Polar Biol. 32, 403–415 (2009).

Huth, T. J. & Place, S. P. De Novo assembly and characterization of tissue specific transcriptomes in the Emerald notothen, Trematomus bernacchii. BMC Genom. 14, 805 (2013).

Huth, T. J. & Place, S. P. Transcriptome wide analyses reveal a sustained cellular stress response in the gill tissue of Trematomus bernacchii after acclimation to multiple stressors. BMC Genom. 17, 127 (2016).

Bogan, S. N. & Place, S. P. Accelerated evolution at chaperone promoters among Antarctic notothenioid fishes. BMC Evol. Biol. 19, 205 (2019).

Bilyk, K. T. et al. Evolution of chaperome gene expression and regulatory elements in Antarctic notothenioid fishes. Heredity 126, 424–441 (2021).

Hofmann, G. E., Buckley, B. A., Airaksinen, S., Keen, J. E. & Somero, G. N. Heat-shock protein expression is absent in the Antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii (family Nototheniidae). J. Exp. Biol. 203, 2331–2339 (2000).

Greco, S. et al. Gene expression profiling of trematomus bernacchii in response to thermal and stabling stress. Fishes 7, 387 (2022).

Carotti, E. et al. Transcriptional contribution of transposable elements in relation to salinity conditions in teleosts and Silencing mechanisms involved. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5215 (2022a).

Carotti, E., Carducci, F., Canapa, A., Barucca, M. & Biscotti, M. A. Transposable element tissue-specific response to temperature stress in the stenothermal fish Puntius tetrazona. Animals 13, 1 (2022b).

Carducci, F., Biscotti, M. A., Forconi, M., Barucca, M. & Canapa, A. An intriguing relationship between teleost Rex3 retroelement and environmental temperature. Biol. Lett. 15, 20190279 (2019).

Rhee, J. S. et al. Diversity, distribution, and significance of transposable elements in the genome of the only selfing hermaphroditic vertebrate Kryptolebias marmoratus. Sci. Rep. 7, 40121 (2017).

Yuan, Z. et al. Comparative genome analysis of 52 fish species suggests differential associations of repetitive elements with their living aquatic environments. BMC Genom. 19, 141 (2018).

Auvinet, J. et al. Insertion hot spots of DIRS1 retrotransposon and chromosomal diversifications among the Antarctic teleosts Nototheniidae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 701 (2019).

Finnegan, D. J. Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. Trends Genet. 5, 103–107 (1989).

Makarevitch, I. et al. Transposable elements contribute to activation of maize genes in response to abiotic stress. PLoS Genet. 11, e1004915 (2015).

Zovoilis, A., Cifuentes-Rojas, C., Chu, H. P., Hernandez, A. J. & Lee, J. T. Destabilization of B2 RNA by EZH2 activates the stress response. Cell 167, 1788–1802 (2016).

Slotkin, R. K. & Martienssen, R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 272–285 (2007).

Cordaux, R., Lee, J., Dinoso, L. & Batzer, M. A. Recently integrated Alu retrotransposons are essentially neutral residents of the human genome. Gene 373, 138–144 (2006).

Konkel, M. K. & Batzer, M. A. A mobile threat to genome stability: the impact of non-LTR retrotransposons upon the human genome. Semin Cancer Biol. 20, 211–221 (2010).

Carotti, E., Carducci, F., Barucca, M., Canapa, A. & Biscotti, M. A. Transposable elements: epigenetic Silencing mechanisms or modulating tools for vertebrate adaptations? Two sides of the same coin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11591 (2023).

Foyle, K. L., Hess, S., Powell, M. D. & Herbert, N. A. What is gill health and what is its role in marine finfish aquaculture in the face of a changing climate? Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 400 (2020).

Sáez-Arteaga, A. et al. Impact of increasing temperatures on neuroendocrine and molecular responses of skeletal muscle and liver in fish: a comprehensive review. Aquac Rep. 39, 102448 (2024).

Piacentini, L. et al. Transposons, environmental changes, and heritable induced phenotypic variability. Chromosoma 123, 345–354 (2014).

Potapenko, E. et al. Transposable elements are entangled in rapid adaptation to climate change. bioRxiv (2024).

Rey, O., Danchin, E., Mirouze, M., Loot, C. & Blanchet, S. Adaptation to global change: a transposable element-epigenetics perspective. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 514–526 (2016).

Casacuberta, E. & González, J. The impact of transposable elements in environmental adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 22, 1503–1517 (2013).

Pappalardo, A. M., Ferrito, V., Biscotti, M. A., Canapa, A. & Capriglione, T. Transposable elements and stress in vertebrates: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1970 (2021).

Miousse, I. R. et al. Response of transposable elements to environmental stressors. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 765, 19–39 (2015).

Carotti, E. et al. Transposable elements and teleost migratory behaviour. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 602 (2021).

Carducci, F., Barucca, M., Canapa, A. & Biscotti, M. A. Rex retroelements and teleost genomes: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3653 (2018).

Carducci, F., Barucca, M., Canapa, A., Carotti, E. & Biscotti, M. A. Mobile elements in ray-finned fish genomes. Life (Basel). 10, 221 (2020).

Chalopin, D., Naville, M., Plard, F., Galiana, D. & Volff, J. N. Comparative analysis of transposable elements highlights mobilome diversity and evolution in vertebrates. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 567–580 (2015).

Shao, F., Han, M. & Peng, Z. Evolution and diversity of transposable elements in fish genomes. Sci. Rep. 9, 15399 (2019).

Horváth, V., Merenciano, M. & González, J. Revisiting the relationship between transposable elements and the eukaryotic stress response. Trends Gen. 33, 832–841 (2017).

de Oliveira, D. S., Rosa, M. T., Vieira, C. & Loreto, E. L. S. Oxidative and radiation stress induces transposable element transcription in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Evol. Biol. 34, 628–638 (2021).

Melo, E. S. & Wallau, G. L. Limited stress and tissue-specific transcriptional and translational activity of transposable elements in mosquitoes. BioRxiv (2024).

Pierron, F., Daffe, G., Lambert, P., Couture, P. & Baudrimont, M. Retrotransposon methylation and activity in wild fish (A. anguilla): A matter of size. Environ. Pollut. 245, 494–503 (2019).

Naito, K. et al. Unexpected consequences of a sudden and massive transposon amplification on rice gene expression. Nature 461, 1130–1134 (2009).

Pecinka, A., Dinh, H. Q., Baubec, T., Rosa, M. & Lettner, N. Mittelsten Scheid, O. Epigenetic regulation of repetitive elements is attenuated by prolonged heat stress in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 22, 3118–3129 (2010).

Yasuda, K. et al. Utilization of transposable element as a novel genetic tool for modification of the stress response in rice. Mol. Breed. 32, 505–516 (2013).

Cavrak, V. V., Lettner, N., Jamge, S., Kosarewicz, A. & Bayer, L. M. Mittelsten Scheid, O. How a retrotransposon exploits the plant’s heat stress response for its activation. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004115 (2014).

Hunter, R. G. et al. Acute stress and hippocampal histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation, a retrotransposon silencing response.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 17657–17662 (2012).

Truzzi, C., Illuminati, S., Antonucci, M., Scarponi, G. & Annibaldi, A. Heat shock influences the fatty acid composition of the muscle of the Antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii. Mar. Environ. Res. 139, 122–128 (2018).

Johnston, I. A. & Battram, J. Feeding energetics and metabolism in demersal fish species from Antarctic, temperate and tropical environments. Mar. Biol. 115, 7–14 (1993).

Stepanowska, K. & Nędzarek, A. Changes in the body chemical composition and the excretion of nitrogen and phosphorus during long-term starvation of Antarctic fish Notothenia coriiceps and Notothenia Rossii. Eur. Zool. J. 87, 571–579 (2020).

Bakiu, R., Piva, E., Pacchini, S. & Santovito, G. Antioxidant systems in extremophile marine fish species. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12, 1280 (2024).

Piva, E. et al. Unravelling stress granules in the deep cold: characterisation of TIA-1 gene sequence in Antarctic fish species. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 154, 109903 (2024).

Guillen, A. C. et al. Gradual increase of temperature trigger metabolic and oxidative responses in plasma and body tissues in the Antarctic fish Notothenia Rossii. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 48, 337–354 (2022).

Tolomeo, A. M. et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 from the Antarctic Emerald rockcod: molecular characterization of its response to warming. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 186, 59–71 (2016).

Tolomeo, A. M. et al. Molecular characterization of novel mitochondrial Peroxiredoxins from the Antarctic Emerald Rockcod and their gene expression in response to environmental warming. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 225, 108580 (2019).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genomic data quality and beyond. Curr. Protoc. 1, e323 (2021).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De Novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 21, 351–358 (2005).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

The UniProt Consortium UniProt. A worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D506–D515 (2019).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–W37 (2011).

RStudio Team & RStudio RStudio: integrated development for R (PBC, 2020).

Wickham, H. & Bryan, J. readxl: Read Excel Files (R package version 1.4.3). (2023). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readxl-

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Neuwirth, E. RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes. R package version 1.1-3. (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RColorBrewer

Ooms, J. magick: advanced graphics and image-processing in R. R package version 2.7.3. URL: (2021). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=magick

Gu, Z., Gu, L., Eils, R., Schlesner, M. & Brors, B. Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30, 2811–2812 (2014).

Oksanen, J. vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.6-6. (2024). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

Jin, Y., Tam, O. H., Paniagua, E. & Hammell, M. TEtranscripts: a package for including transposable elements in differential expression analysis of RNA-seq datasets. Bioinformatics 31, 3593–3599 (2015).

Li, H. et al. 1000 genome project data processing subgroup, the sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis (Springer-, 2016). https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L. & Müller, K. dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation (R package version 1.1.4). (2023). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr

Pedersen, T. L. patchwork: the composer of plots (R package version 1.1.3). (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=patchwork

Acknowledgements

This paper related research has been conducted during and with the support of the Italian inter-university PhD course in sustainable development and climate change (link: www.phd-sdc.it).

Funding

This research was funded by Polytechnic University of Marche in the framework of “Progetto Scientifico di Ateneo”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.T. and E.C.: methodology, transcriptomic TE data analysis and bioinformatic statistical analyses; G.S. and E.P.: experimental exposures; E.P.: tissue preparation; E.T.: RNA extraction and check-quality; F.C. and C.P.: transcriptomic gene expression analysis; A.C. and M.B.: data curation; G.S.: supervision of experimental design; and M.A.B.: research supervision and administration. All authors discussed the results, wrote the manuscript, and commented the final version of the manuscript prior to submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and consent to publish the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tittarelli, E., Carotti, E., Palladinelli, C. et al. Transcriptional response of transposable elements to thermal stress in the Antarctic fish Trematomus bernacchii. Sci Rep 16, 3440 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33487-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33487-5