Abstract

Addressing uncertainties on the demand side caused by electricity price fluctuations during integrated energy system (IES) dispatch, modeling biases resulting from static assumptions about equipment energy efficiency, and cost redundancy issues stemming from unreasonable seasonal allocation of carbon quotas, this study constructs an electricity PDR economic dispatch optimization model incorporating dynamic energy efficiency and dynamic carbon trading. It proposes a “distributed robust optimization (DRO)-model predictive control (MPC)” collaborative framework and a tiered dynamic carbon quota allocation strategy accounting for seasonal output and efficiency variations of equipment, tailored to match carbon emission characteristics across different seasons. At the demand response level, an electricity price elasticity coefficient matrix is introduced to quantify the impact of real-time price fluctuations on load, integrating it into the MPC model to resolve the time-scale mismatch between day-ahead and intraday scheduling. Simulation results demonstrate: The coupled dynamic energy efficiency and carbon trading model reduces total system costs by 13.07% and carbon trading costs by 11.57% compared to the conventional approach. Regarding tracking error, the combination of rolling optimization and feedback correction improves tracking accuracy by 14.66% and 6.13% compared to cases without feedback correction and rolling optimization, respectively, while reducing total costs by 4.36% compared to the case without rolling optimization. This study provides a scientifically feasible optimization solution for low-carbon economic dispatch of IES under uncertainty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Serving as the foundational infrastructure of the energy internet, the integrated energy system (IES) has attracted attention due to its strengths in enabling multi-energy coupling, offering high flexibility, and facilitating the integration of renewable energy1. In 2024, China’s total electricity consumption hit 9,852.1 billion kWh, which was nearly five times the figure recorded in 20002. However, the continuous growth in electricity demand has driven a relentless increase in power generation, resulting in substantial carbon emissions and posing severe challenges to the stability and security of power systems. Against this backdrop, IES has emerged as a critical solution due to its ability to coordinate multiple loads including heat, gas, electricity, and hydrogen3. Yet, IES involves multi-energy flow coupling and exhibits high complexity, making the optimization of its scheduling a key focus in current power system research.

To ensure IES stability, numerous studies have proposed corresponding optimization models from different dimensions. Reference4 introduced a differentiated dynamic pricing demand response model based on a user satisfaction function. This model accounts for the distinct electricity consumption characteristics and price elasticity of commercial and residential electricity consumers (EC), coupling user demand with electricity prices. It effectively reduced peak power demand, lowering peak demand for commercial and residential ECs by 4.99% and 9.99%, respectively. Reference5 proposes a risk-free arbitrage-aware electricity pricing model combined with robust optimization (RO) to enhance pricing scientificity. Reference6 employs real-time price forecasting to reduce peak-to-valley differences in load curves, lowering user electricity bills by 17.5%. Reference7 introduced a three-stage robust optimization to address uncertainties in renewable generation and load forecasting, enabling system stability under extreme conditions while maintaining emissions within target ranges. However, it did not address intraday scheduling. A dynamic optimal scheduling approach with multi-timescale combining RO with MPC-driven rolling optimization was proposed in Reference8, aiming to tackle the mismatch between the time horizons of thermal loads and electrical loads.

AI models have also emerged as a hot research topic in recent studies on IES robustness optimization. For example, Reference9 proposed a topology-aware multi-task reinforcement learning approach based on soft modularization to address load restoration challenges in IES following extreme events, fully leveraging the flexibility of multi-energy microgrids (MEMGs). However, it did not account for the dynamic coupling between source-load forecasting and scheduling, relying instead on predefined fault scenarios. Consequently, its ability to generalize to unseen uncertainties remains limited. Reference10 constructs a Transformer-LSTM hybrid forecasting model, integrating Gaussian process regression to achieve multi-step interval forecasting for random variables; Through a synchronous training mechanism, it couples the double-delay deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm to form an integrated “prediction-scheduling” framework. This addresses nonlinear coupling and source-load uncertainty in IES scheduling, enhancing scheduling optimization performance. However, research on carbon chains is lacking, and carbon costs have not been incorporated into the study scope. Refernece11 integrates carbon capture, power-to-gas (P2G), and carbon trading mechanisms; proposes a two-stage learning-based robust optimization approach. By learning and calibrating the shape of ellipsoidal uncertainty sets, it ensures statistical feasibility, yet lacks sufficient refinement in the coordinated scheduling of multi-energy coupled equipment.

Electricity price-based demand response (EPDR), a crucial tool in IES scheduling, relies heavily on the accuracy of electricity price signals12. Although related electricity price forecasting models have matured and EPDR-based optimization has achieved positive results, research on system stability optimization models considering the impact of real-time electricity price fluctuations on user demand response remains scarce. Concurrently, with the widespread adoption of renewable energy sources, the hourly-level electricity price fluctuations caused by their variability, as an uncertainty factor affecting system stability, have also received limited in-depth discussion in the literature. Furthermore, simple day-ahead DRO models show limited effectiveness in optimizing load fluctuations caused by intraday price fluctuations. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a collaborative model that integrates intraday optimization scheduling with day-ahead robust optimization to enhance the system’s overall resilience against load fluctuation uncertainties induced by electricity prices.

With the advancement of global low-carbon economic strategies, carbon costs are increasingly internalized as critical constraints in IES operations. Beyond optimizing system volatility uncertainties, the coupling design between carbon trading and IES systems has emerged as a new research focus. Reference13 proposed a seasonal carbon trading model that reduced system carbon emissions by 2.54% while lowering operational costs by 22.58%, but it did not address coupling with actual equipment conditions. Reference14 addressed a dynamic carbon quota model, reducing carbon emission costs by 9%, but failed to integrate seasonal variations. Reference15 constructed a two-stage planning model for an electricity-gas coupled integrated energy system (EGC-IES), incorporating carbon capture equipment into power plants to transform them into carbon-capturing facilities. Although low-carbon economic dispatch models have reached relative maturity, significant deficiencies persist in carbon trading model development. Reference16 only considered the impact of dynamic energy efficiency models on equipment and stepwise carbon quotas, failing to effectively couple stepwise carbon trading models with dynamic energy efficiency models. Reference17 optimized the cascading economic dispatch of a park’s integrated energy system through a dynamic energy efficiency model, reducing daily operating costs by 17.04%. However, it employed an annual average carbon quota allocation method, overlooking significant seasonal variations in annual carbon emissions and equipment output. Such an allocation not only deviates from reality but also increases the system’s carbon trading costs, as noted in Reference18. However, taking gas-fired units as an example, summer electricity loads are approximately 1.4 times higher than winter loads19. In actual operation, summer carbon emission intensity of equipment is more than 1.22 times that of winter20. Applying a uniform quota allocation method to each quarter’s carbon allowances would significantly increase carbon trading costs.

In addition, traditional IES systems set equipment efficiency to a fixed value, as described in references21 and22. However, when considering other relevant costs such as system gas procurement expenses, variations in equipment efficiency due to load differences across different time periods within a day can lead to estimation errors in gas procurement costs, operating expenses, and other related costs when using fixed energy efficiency calculations.

Based on the literature review, current IES system optimization scheduling research exhibits numerous shortcomings. To address these limitations, this paper constructs an IES optimization model that comprehensively considers real-time electricity price fluctuations, integrates a tiered carbon trading strategy with seasonal dynamic equipment output, and incorporates a dynamic equipment energy efficiency model. The model’s effectiveness in engineering practice is validated through computational examples. To clearly present the research work, the Table 1 (TOU represents time-of-use) is provided for reference.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

-

A multi-energy flow coupling model integrating load-side demand response through electricity pricing and source-side equipment load dynamic energy efficiency has been established. This model overcomes the limitations of traditional IES models, which neglect the impact of load fluctuations on energy efficiency and treat electricity prices as constants, significantly enhancing the accuracy of multi-energy flow collaborative optimization.

-

By integrating real-time electricity prices with user load and renewable energy output, a real-time pricing calculation method was proposed. This approach simultaneously accounts for renewable energy generation and user-side demand response, effectively enhancing renewable energy absorption rates.

-

A cascading dynamic carbon trading mechanism considering equipment’s dynamic energy efficiency and carbon emissions is proposed. This mechanism enables dynamic allocation of carbon quotas and demonstrates its effectiveness in reducing carbon trading costs within low-carbon economic dispatch.

-

A novel two-stage DRO-MPC collaborative optimization framework based on price elasticity and incorporating electricity price fluctuations is proposed. This framework optimizes load uncertainty on the demand side caused by electricity price fluctuations, mitigates the time scale mismatch between day-ahead optimization and load demand forecasting, and enhances the system’s robustness against risks.

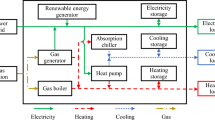

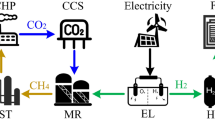

IES modeling

Figure 1 shows the IES structure utilized in this paper and will be further delineated in the ensuant sections. Four forms of energy are integrated the system to meet energy demands under different scenarios, they are electricity, heat, gas, and hydrogen.

Energy conversion equipment modeling

EL and MR modeling

where, \(P_{\text {ng},t}^{\text {pro}}\) and \(P_{\text {H},t}^{\text {EL}}\) represents the output power of MR and EL respectively; \(\eta _{\text {MR}}^{\text {pro}}\) and \(\eta _{\text {H},t}^{\text {pro}}\) donates the energy efficiency of MR and EL at time t, respectively.

HFC modeling

The hydrogen energy can be converted into electric and heat energy by HFC. The model is outlined below:

where, \(P_{\text {HFC},e,t}\) and \(P_{\text {HFC},h,t}\) donates the electrical power and thermal power output of HFC respectively; \(\eta _{\text {HFC}}^{\text {e}}\) and \(\eta _{\text {HFC}}^{\text {h}}\) represents the electrical and thermal efficiency of HFC; \(\kappa _{\text {HFC}}^{\text {max}}\) and \(\kappa _{\text {HFC}}^{\text {max}}\) donates the upper and lower limit heat-to-electric ratio of HFC respectively.

GB and GT modeling

The model of GB and GT can be expressed as follows:

where, Y stands for the GB or GT; \(\eta _{Y,t}\) represents the energy efficiency of device Y at time t; \(P_{Y,t}\) is the output power of device Y at time t; \(P_{Y,t}^{\text {in}}\) represents the natural gas energy input to the device Y; \(\Delta P_{Y}^{\text {in,max}}\) and \(\Delta P_{Y}^{\text {in,min}}\) donates the upper and lower limit of ramp-rate respectively.

Dynamic efficiency model (DEM)

To enhance the accuracy of the model constructed in this paper, the IES model developed here treats equipment efficiency not as a constant value but as a dynamic value dependent on equipment load. Based on equipment load, the efficiency model can be established as follows:

where, \(\alpha _{\text {Y},i}\) represents the i-th order fitting factor of the efficiency function polynomial for device Y; \(P_{\text {Y,N}}\) indicates the rated output power of device Y.

Energy storage equipment modelling

Considering that energy storage devices such as batteries, hydrogen storage tanks, gas storage tanks, and heat-sensitive tubes operate on similar principles, modeling is performed using batteries as an example, with other devices following analogous approaches:

where, \(\tau _{\text {es}}\) represents self-energizing rate of the device; \(\eta _{\text {es,chr}}\) and \(\eta _{\text {es,dis}}\) donates the charge and discharge efficiency of the device respectively; \(U_{\text {es,chr},t}\) and \(U_{\text {es,dis},t}\) represents the charging and discharging flag bit of the device.

Renewable energy equipment modelling

In this paper, wind energy and solar energy are selected as the renewable energy sources. wind power go conversion process via wind turbines (WT) and solar power go conversion via photovoltaic (PV) devices. Thus, the output power of renewable energy devices in the IES can be outlined in the following way:

where, \(P_{\text {res},t}, P_{\text {wind},t}\), and \(P_{\text {pv},t}\) represent the output power of the renewable energy system, WT, and PV power generation equipment, respectively.

Price-driven demand response (PDR)

This paper introduces a price elasticity coefficient matrix to describe PDR, quantifying the impact of electricity prices on system load-side stability. The expression for the price elasticity coefficient matrix is:

where the price elasticity coefficient \(\epsilon _{i,j}\) is expressed as:

where \(Q_{\text {PDR,b}}^i\) represents the benchmark of user’s electrical demand; and \(Q_{\text {PDR}}^i\) donates the real value of user’s electrical demand; \(\lambda _{\text {ele,fix}}^{\text {buy},j}\) is the TOU electricity price at time j; \(\lambda _{\text {ele,float}}^{\text {buy},j}\) represents the real time value when considering the PDR model.

The real-time electricity price calculation formula considering renewable energy output and load fluctuations is:

where: 1, 2, 3…n represent the first, second, third…nth time periods, respectively. From the above formulation, the price-demand load response model is derived:

Carbon trading cost modelling

Since different equipment exhibits varying energy efficiency across seasons, changes in energy efficiency often imply shifts in carbon emissions. To minimize carbon trading costs, this study proposes a dual-tiered dynamic carbon trading cost optimization model that integrates dynamic equipment energy efficiency with seasonal carbon trading patterns.

The specific calculation for the amount of \(\mathrm {CO_2}\) captured by the carbon capture and storage equipment(CCS) is:

where, \(P_{w}^{{\text {CCS}},t}\) donates total output power of CCS unit at time t; \(P_{w}^{{\text {I}},t}\) represents the net output power of CCS unit at time t; \(P_{w}^{{\text {D}},t}\) stands for the fixed energy consumption CCS unit at time t and \(P_{w}^{{\text {B}},t}\) means operating energy consumption of CCS unit at time t respectively; w donates the device number index of CCS; \(\kappa _{{\text {CCS}}}\), \(\varepsilon _{t}\), \(\xi _{w}\) \(\mu\) represents carbon capture coefficient, actual carbon emission coefficient, flue gas diversion ratio, maximum operating coefficient of regeneration tower and compressor of CCS unit respectively; \(\nu\) donates the power consumed by the CCS to capture a unit amount of \(\text {CO}_2\); \(\varphi _{w,t}\) stands for the total volume of \(\text {CO}_2\) captured by CCS at time t, while \(m_{w,t}\) donates the total volume of \(\text {CO}_2\) produced by the CCS unit at time t; \(\varphi _{w,t}^{{\text {Store}}}\) represents the quantity of \(\text {CO}_2\) to be captured by the solution reservoir; \(P_{w}^{{\text {max}}}\) the maximum output of the generator set.

When the equipment uses \(\text {CO}_2\) to produce methane, it consumes a portion of the \(\text {CO}_2\). Therefore, the equipment’s \(\text {CO}_2\) emissions are:

where, \(E_{\text {act},t}^{\text {G}}\), \(E_{\text {act},t}^{\text {Gas}}\) donates the carbon emmision of generator set and gasload respectively; \(\tau _{\psi }^{\text {act}}\), \(\tau _{\text {Gas}}^{\text {act}}\) represents the corresponding coefficients of each unit.

The system’s carbon allowance \(E_{\text {q},t}\) can be calculated using the following Eq. (14):

The system’s net carbon emissions equal actual carbon emissions minus the carbon allowance, i.e.:

where, \(\zeta _{\text {carbon}}^{\text {power}}\) donates the \(\text {CO}_2\)emmitted per unit of electricity consumed by user.

The quarterly base carbon allowance coefficient \(\tau _{\psi ,\text {base}}^\text {allo}\) for gas-fired power generation equipment is determined by the equipment’s output:

During actual operation, equipment energy efficiency varies by season. Therefore, the dynamic energy efficiency carbon quota coefficient model is:

The formula for calculating \(\lambda _{i}^{\text {season}}\) using the equipment’s dynamic energy efficiency model is shown as Eq. (18):

where \(\eta _{i}^{\text {D}}\) donates the average dynamic efficiency of each season, \(\eta _{i}^{\text {season}}\) donates the rated efficiency of the device.

Considering the seasonal nature of carbon emissions, carbon quotas are allocated according to different seasons as Eq. (19):

The carbon quotas for each quarter are:

Constraints

The constraints for IES primarily include: equipment power balance, equipment output constraints, equipment ramping constraints, and curtailment ratio constraints for renewable energy equipment. Their specific forms are:

-

(1)

Power balance:

-

Electrical power balance:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned}&P_{\text {ele},t}^{\text {buy}} + P_{\text {wind},t} + P_{\text {vc},t} + P_{\text {es,dis},t}^{\text {ele}} + P_{\text {HFC},e,t} + \sum _{\text {k}=1}^{N_{\text {GT}}} P_{\text {GT},k,t} = P_{\text {EL,in},t} + P_{\text {WCC},t} + P_{\text {LCC},t} + \frac{Q_{\text {PDR}}^{t}}{\Delta t} + P_{\text {es,chr},t}^{\text {ele}} + P_{\text {w}}^{\text {CCS},t} \\&Q_{\text {PDR}}^{t} = Q_{\text {PDR,b}}^{t} + \Delta Q_{\text {PDR}}^{t} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(21)where: \(P_{\text {WCC},t}\) and \(P_{\text {LCC},t}\) represent curtailed wind power and curtailed solar power, respectively.

-

Thermal power balance:

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{k=1}^{N_{\text {GB}}} P_{\text {GB},k,t} + P_{\text {HFC},h,t} + P_{\text {es,dis},t}^{\text {heat}} = P_{\text {heat},t}^{\text {load}} + P_{\text {es,chr},t}^{\text {heat}} \end{aligned}$$(22)where \(P_{\text {heat},t}^{\text {load}}\) is the heatload of the system at time t.

-

Hydrogen power balance:

$$\begin{aligned} P_{\text {H},t}^{\text {EL}} + P_{\text {Hs,chr},t} = P_{\text {Hs,dis},t} + P_{\text {H}_2,\text {HFC},t} + P_{\text {H},t}^{\text {MR}} \end{aligned}$$(23)-

Gas balance:

$$\begin{aligned} P_{\text {ng},t}^{\text {pro}} + P_{\text {gs,chr},t} + n_{\text {ng,t}}^{\text {buy}} \cdot \text {G}_{\text {ng}}^{\text {calor}} = P_{\text {gs,dis},t} + P_{\text {GB},t}^{\text {in}} + P_{\text {GT},t}^{\text {in}} + P_{\text {gasload}}^{t} \end{aligned}$$(24) -

-

(2)

Power purchase constraint:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned}&P_{\text {ele,min}}^{\text {buy}} \le P_{\text {ele},t}^{\text {buy}} \le P_{\text {ele,max}}^{\text {buy}} \\&\Delta P_{\text {grid,down}} \le P_{\text {ele,float}}^{\text {buy},t} - P_{\text {ele,float}}^{\text {buy},t-1} \le \Delta P_{\text {grid,up}} \\&0 \le P_{\text {EL,in}} \le P_{\text {ELN}} \\&0 \le P_{\text {HFC},t}^{\text {discharge}} \le P_{\text {HFC},t,\text {max}}^{\text {discharge}} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(25) -

(3)

Energy storage constraints Constraints related to energy storage equipments include natural gas storage, hydrogen storage, and thermal power storage. They are detailed in section “Energy storage equipment modelling” on energy storage modeling and will not be repeated here.

-

(4)

Gas purchase constraints The quantity of natural gas purchased during the period from 0 to T, \(n_\text {ng}^\text {buy}\), can be expressed as Reference23 mentioned:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned}&n_{\text {ng}}^{\text {buy}} = \max \left\{ 0, \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \left( \frac{\sum _{k=1}^{N_{\text {GB}}} \frac{P_{\text {GB},k,t}}{\eta _{\text {GB},k,t}} + \sum _{k=1}^{N_{\text {GT}}} \frac{P_{\text {GT},k,t}}{\eta _{\text {GT},k,t}} }{G_{\text {ng}}^{\text {calor}}} - \frac{P_{\text {ng},t}^{\text {pro}}}{G_{\text {ng}}^{\text {calor}}} - \frac{S_{\text {ng},t-1}}{G_{\text {ng}}^{\text {calor}}} \right) \cdot \Delta t \right\} \\&0 \le n_{\text {ng},t}^{\text {buy}} \le \frac{S_{\text {ng,max}}}{G_{\text {ng}}^{\text {calor}}} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(26) -

(5)

Output constraints of renewable energy equipment:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned}&P_{\text {wind},t}^{\text {min}} \le P_{\text {wind},t} \le P_{\text {wind},t}^{\text {max}} \\&P_{\text {vc},t}^{\text {min}} \le P_{\text {vc},t} \le P_{\text {vc},t}^{\text {max}} \\&\Delta P_{\text {wind},t}^{\text {min}} \le P_{\text {wind},t} - P_{\text {wind},t-1} \le \Delta P_{\text {wind},t}^{\text {max}} \\&\Delta P_{\text {vc},t}^{\text {min}} \le P_{\text {vc},t} - P_{\text {vc},t-1} \le \Delta P_{\text {vc},t}^{\text {max}} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(27) -

(6)

Constraint of the renewable energy curtailment ratio:

$$\begin{aligned} P_{\text {WCC},t} + P_{\text {LCC},t} \le \varepsilon _{\text {c}} \cdot \left( P_{\text {wind},t} + P_{\text {vc},t} \right) \end{aligned}$$(28)Considering the varying power generation of clean energy across different time periods, \(\varepsilon _{\text {c}}\) is set as two segments: daytime (7:00-18:00) and nighttime (18:00-7:00), i.e.:

$$\begin{aligned} \varepsilon _{\text {c}} = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \varepsilon _{\text {c1}}, & t \in (7:00 - 18:00) \\ \varepsilon _{\text {c2}}, & t \in (18:00 - 7:00) \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(29)where: \(\varepsilon _{\text {c}}\) represents the curtailment ratio.

Cost calculation

The total cost of IES can be devided into several parts listed below:

-

(1)

Carbon trade costs: When actual carbon emissions of IES surpass its assigned quota, the IES is obligated to buy carbon credits. Aiming at reducing the harm to the environment, tiered carbon trading model is adopted. The model is detailed as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} c_{\text {carbon}}^{\text {trade}} = \left\{ \begin{aligned}&\alpha E_{\text {net}}, \ E_{\text {net}} \le \gamma \\&\alpha \gamma + (1 + \beta )\alpha (E_{\text {net}} - \gamma ), \ \gamma< E_{\text {net}} \le 2\gamma \\&(2 + \beta )\alpha \gamma + (1 + 2\beta )\alpha (E_{\text {net}} - 2\gamma ), \ 2\gamma< E_{\text {net}} \le 3\gamma \\&(3 + 3\beta )\alpha \gamma + (1 + 3\beta )\alpha (E_{\text {net}} - 3\gamma ), \ 3\gamma< E_{\text {net}} \le 4\gamma \\&(4 + 6\beta )\alpha \gamma + (1 + 4\beta )\alpha (E_{\text {net}} - 4\gamma ), \ 4\gamma < E_{\text {net}} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(30) -

(2)

Gas procurement costs:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned} C_{\text {gas}}^{\text {buy}}&= C_{\text {ng}}^{\text {buy}} + C_{\text {CO}_2}^{\text {buy}} \\ C_{\text {ng}}^{\text {buy}}&= \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \lambda _{\text {ng}}^{\text {buy}} n_{\text {ng},t}^{\text {buy}} \\ C_{\text {CO}_2}^{\text {buy}}&= \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \lambda _{\text {CO}_2}^{\text {buy}} n_{\text {CO}_2,t}^{\text {buy}} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(31)where: \(\lambda _{\text {ng}}^{\text {buy}}\) and \(\lambda _{\text {CO}_2}^{\text {buy}}\) represent the unit prices for purchasing the corresponding gas; \(C_{\text {ng}}^{\text {buy}}\) and \(C_{\text {CO}_2}^{\text {buy}}\) denote the costs for purchasing the corresponding gas; \(C_{\text {gas}}^{\text {buy}}\) indicates the total gas procurement cost.

-

(3)

Electricity Purchase Cost:

$$\begin{aligned} C_{\text {ele}}^{\text {buy}} = \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \left( \lambda _{\text {ele,fix}}^{\text {buy}} P_{\text {ele,fix}}^{\text {buy}} + \lambda _{\text {ele,float}}^{\text {buy}} P_{\text {ele,float}}^{\text {buy}} \right) \end{aligned}$$(32) -

(4)

Operation cost The operational costs of each piece of equipment are calculated using its energy parameters and corresponding coefficients. In the context of energy generation devices, this energy is referred to as the output power. In the context of gas-electricity conversion systems, it signifies the aggregate energy input derived from all devices that are connected to the system. With regard to energy storage devices, this term denotes the energy released by the storage system. The comprehensive expression is as Eq. (33):

$$\begin{aligned} C_{\text {ope}} = \sum _{t=1}^{\text {T}} \sum _{i=1}^{\text {N}} c_{i} E_{i,t} \end{aligned}$$(33)where: \(c_{i}\) represents the operating cost coefficient for device i, and \(E_{i,t}\) denotes the total energy released by the device.

-

(5)

Wind curtailment cost (WCC) and solar light curtailment cost (LCC):

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned} C^{\text {WCC}}&= \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \lambda _{\text {WCC}} P_{\text {WCC},t} \\ C^{\text {LCC}}&= \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \lambda _{\text {LCC}} P_{\text {LCC},t} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(34)where \(\lambda _{\text {WCC}}\) and \(\lambda _{\text {LCC}}\) denote the WCC and LCC coefficients, respectively; \(C^{\text {WCC}}\) and \(C^{\text {LCC}}\) denote the WCC and LCC, respectively.

-

(6)

Energy storage cost: As electrical, heat, gas, and hydrogen storage devices feature a comparable model structure, the example provided below will utilize battery modeling for demonstration purposes:

$$\begin{aligned} C_{\text {es,ele}} = \sum _{t=1}^{\text {T}} \lambda _{\text {es}} S_{\text {e},t} \end{aligned}$$(35)Where: \(\lambda _{\text {es}}\) denotes the cost per unit of power stored by the energy storage device.

-

(7)

Costs of CCS operation:

$$\begin{aligned} C^{\text {CCS}} = \sum _{t=0}^{\text {T}} \left( \text {a}_{\text {CCS}} P_{w}^{\text {CCS},t} + \text {b}_{\text {CCS}} \right) \end{aligned}$$(36)where: \(\text {a}_{\text {CCS}}\) represent the linear term coefficient and \(\text {b}_{\text {CCS}}\) donates the constant term of the CCS equipment cost. Through the discussion above, the total cost of the system \(C_{\text {total}}\) is outlined:

$$\begin{aligned} C_{\text {total}} = C_{\text {carbon}}^{\text {trade}} + C_{\text {gas}}^{\text {buy}} + C_{\text {ele}}^{\text {buy}} + C_{\text {ope}} + C^{\text {WCC}} + C^{\text {LCC}} + C^{\text {CCS}} + C_{\text {es}} \end{aligned}$$(37)

Day-ahead DRO for electricity PDR

Scenario acquisition

Before conducting DRO, the acquisition of data relies on scenario generation. In this paper, uncertainty scenarios are consist of the PV, WT and fluctuations of diverse form of energy demands. This article adopts a data-driven DRO model, where a simplified data source is required. The target is realised using latin hypercube sampling (LHS), and k-means clustering to determine the optimal number of representative scenarios and the final set. Before clustering, the elbow method is needed to find out the best k value to be applied to the clustering.

The framework of data-driven DRO

Based on the features of different devices, all discrete variables (including determined quantities and flag variables representing device operational states) are defined as the first-stage decision variable \(\varvec{x}\). All remaining uncertain continuous variables serve as the second-stage decision variable \(\varvec{y}\). Based on the variables discussed above, the objective function are outlined as follows:

where, K represents the quantity of discrete scenarios; T denotes the total number of time periods in the current day; \(\text {F}_1(\varvec{x})\) denotes the objective function for the first stage; \(p_k\) represents the probability distribution value for the scenario k; \(\Omega\) denotes the feasible region for scenario probability distributions under the comprehensive norm constraint; \(\text {g}(\varvec{x}, \varvec{\xi }_k)\) defines the inner minimization problem; \(\varvec{\xi }_k\) corresponds to the discrete scenario k; \(\text {Y}(\varvec{x}, \varvec{\xi }_k)\) indicates the feasible region for \(\varvec{y}_k\) given a set of \((\varvec{x}, \varvec{\xi _k})\); \(\varvec{y_k}\) represents the variable for the second stage under the scenario k; \(\text {A}(\varvec{x})\) constitutes the constraint related solely to first-stage variables; \(\text {F}_2(\varvec{x}, \varvec{\xi _k}, \varvec{y_k})\) serves as the objective function for the second stage; \(\text {B}(\varvec{x}, \varvec{\xi }_k, \varvec{y}_k)\) reflects the second-stage constraint accounting for uncertain information.

In the formula, \(\min \limits _{\varvec{x}}\) ensures reasonable and conservative first-stage decisions to guarantee model availability under worst-case scenarios; the intermediate layer \(\max \limits _{p_k \in \Omega }\) ensures the model can identify the probability distribution of worst-case scenarios from fuzzy sets \(\Omega\); the inner layer \(\min \limits _{\varvec{y_k} \in \text {Y}}\) ensures optimal second-stage scheduling for equipment during the two-stage decision process and minimizes the total cost of IES under all possible scenarios.

In the model, it is imperative that both the \(\infty\)-norm and the 1-norm are incorporated with a view to minimizing the discrepancy between the real distribution and the initial distribution \(p_k\), which is generated through history data. The fuzzy set \(\Omega\) is as follows:

where, \(p_k^0\) denotes the initial scenario probability distribution value; \(\theta _{1}\) and \(\theta _{\infty }\) donate the maximum probability deviation constraints which correspond to the 1-norm constraint and \({\infty }\)-norm constraint, respectively. Where \(p_k\) obeys the confidence level below:

Setting the right-hand side of the above equation equal to the confidence levels \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _{\infty }\) yields:

The objective function for the first stage is:

The objective function for the second stage is:

Intraday MPC

Although day-ahead robust optimization effectively enhances system stability, uncertainty in electricity price fluctuations persists, typically occurring at the intraday level. This necessitates addressing the temporal mismatch between day-ahead robust optimization and intraday forecasting. Accordingly, this paper proposes an intraday MPC optimization approach to resolve the temporal discrepancy between day-ahead optimization and electricity price responsiveness.

During the intraday MPC scheduling phase, the first step is to obtain the electricity prices and load parameters for each time period with the data derived from the optimized results of DRO. In the MPC prediction process, user loads are forecast using these parameters, ensuring robustness while maintaining prediction accuracy. Based on the definition of price elasticity coefficients, i.e., the price elasticity matrix:

where, n denotes the number of time periods affected by electricity prices.

Rewritten in state equation form:

where, \(Q_{\text {PDR,pred}}^{t}\) represents the rolling optimization forecast value.

Rolling optimization

The objective function for rolling optimization is:

where, \(\rho\) represents the electricity price penalty coefficient; \(\varvec{x}\) signifies the optimal solution for variable x obtained through DRO; \(\delta _{\lambda , t}^{\text {float}}\) represents the allowable electricity price forecast fluctuation during MPC; \(\delta _{\text {PDR}}^t\) denotes the allowable user load fluctuation during MPC.

Feedback correction

In practical implementations of MPC, discrepancies can arise between the outcomes of rolling optimization and the system situation in reality due to model mismatch and prediction errors. To alleviate these inconsistencies, a dynamic feedback correction mechanism based on electrical price elastic coefficient is incorporated. The deviation between actual and predicted demand is calculated as:

where, \(\Delta Q_{\text {PDR, err}}^t\) represents the error between actual user electricity consumption and the model prediction.

The price elasticity response coefficient is corrected using \(\Delta Q_{\text {PDR,pred}}^{t}\):

where, \(\epsilon _{t, j}^{\text {new}}\) is the corrected electricity price elasticity coefficient; \(\epsilon _{t, j}^{\text {old}}\) represents the elasticity coefficient before correction; and \(\omega\) denotes a weighting factor between 0 and 1, used to adjust the correction intensity of the elasticity coefficient based on prediction errors. Its value will be determined during the simulation process.

Substitute the corrected price elasticity coefficient into the model for a new round of prediction, thereby completing the feedback correction of the price elasticity coefficient:

Solution method of model

DRO solution method

To address the DRO problem proposed in this paper, the C&CG method is employed. Through iteration, this method transforms the complex min-max-min problem in the DRO model into a series of alternately solved subproblems within the main problem domain, featuring clearer structures that facilitate computational processing. Furthermore, this algorithm does not rely on exhaustively enumerating all possible worst-case scenarios to derive the fuzzy sets required for DRO. Instead, during each iteration, the subproblem identifies the worst-case scenario under the current solution of the main problem and dynamically incorporates it into the main problem. This approach significantly reduces computational effort. By progressively tightening upper and lower bounds, overall convergence is ensured, ultimately yielding robust scheduling results. Therefore, decomposing the original problem into a main problem and subproblems for iterative solution is essential. The expressions for the main problem and subproblems are provided below:

-

(1)

MP In the scenario delineated by the probability distribution p, the primary objective is to identify the optimal solution that not only ensures system economic efficiency but also establishes a lower bound for the objective function:

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned}&\min _{\varvec{x, \xi _k} \in Y(\varvec{x, \xi _k})} \{ \text {F}_1(\varvec{x}) + \text {f}_1 \} \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(54)$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned}&\text {s.t.} \left\{ \begin{array}{l} \text {f}_1 \ge \sum _{k=1}^{K} p_k^m \text {g}(\varvec{x, \xi _k}) \\ \text {A}_1(\varvec{x}) \le 0 \\ \text {A}_2(\varvec{y}) \le 0 \\ \text {A}_3(\varvec{x, y}) = 0 \end{array} \right. \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(55)where, m denotes the iteration count, and \(\text {A}_1(\varvec{x})\), \(\text {A}_2(\varvec{x})\), \(\text {A}_3(\varvec{x})\) are constraint functions associated with \(\varvec{x}\) and \(\varvec{y}\), respectively.

-

(2)

SP In consideration of the first-stage variables \(\varvec{(x)^*}\) of MP, the objective of SP is to ascertain the worst-case probability distribution within the context of real-time operation. Subsequently, SP returns this information to the MP, thereby providing an upper limit for the objective function.

$$\begin{aligned} f_2 = \max _{p_k \in \Omega } \left\{ \sum _{k=1}^{\text {K}} p_k \text {g}(\varvec{x, \xi _k}) \right\} \end{aligned}$$(56)where:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {g}(\varvec{x, \xi _k}) = \min _{y_k \in Y(\varvec{x, \xi _k})} \{ \text {F}_2(\varvec{x, \xi _k, y_k}) \} \end{aligned}$$(57)$$\begin{aligned} \text {s.t.} \left\{ \begin{array}{l} \text {A}_1(\varvec{x}) \le 0 \\ \text {A}_2(\varvec{y}) \le 0 \\ \text {A}_3(\varvec{x,y}) = 0 \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(58) -

(3)

C&CG algorithm solution steps are as follows, as illustrated in Fig. 2

DRO-MPC solution method

Based on DRO-based solution combined with MPC solution methods, Fig. 3 shows the proposed DRO-MPC model solution method

:

Overall schematic diagram

To help readers gain a clearer understanding of the work presented in this paper, Fig. 4 illustrates the structural schematic diagram of the proposed architecture.

Simulation analysis

Simulation situation and parameters

A typical IES located in Nanchang City, Jiangxi Province, China serves as the case study to investigate the proposed scheduling optimization scheme. For carbon trading cost analysis, both full-year data and data from a single summer day are employed for comprehensive evaluation, while other models utilize data from a single summer day. Put into effect in MATLAB R2023b, the simulation makes use of the YALMIP toolbox and adopts CPLEX as its solver.

Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 shows parameters of the IES, and the TOU electricity prices are shown in Fig. 6 (right).

As what mentioned before, by using LHS, 1000 data was obtained. Subsequently, the elbow method determined the optimal number of clusters to be 8, as shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5a, b, and c illustrate the output of wind power and solar power, and the electricity demand on the load side throughout a day, respectively. The distribution of probabilities for each scenario is shown in Table 7.

Through field research, actual electricity load baseline values were obtained. The electricity price elasticity coefficient matrix was calculated as follows, as shown in Fig. 6 (left).

Research on the effectiveness of PDR

Simulation analysis case design

To validate the specific effects of coupling the PDR model with the electricity price fluctuation calculation model that considering the output power of renewable energy equipment and load-side response, this study simulates the following scenarios under the framework of dynamic carbon trading, dynamic energy efficiency modeling, and DRO-MPC:

-

(1)

Scenario considering only TOU electricity pricing.

-

(2)

Scenario considering only TOU pricing and PDR.

-

(3)

Scenario considering only TOU pricing and the price fluctuation model.

-

(4)

Simultaneous consideration of TOU pricing, price volatility, and the PDR model.

Analysis of simulation results

Based on the experiment in section “Simulation analysis case design”, the abandoned power of renewable energy, the consumption rate of renewable energy and the electricity electricity purchasing cost cost are adopted as evaluation metrics. After simulation, the three metrics for the four scenarios are shown in Table 8.

As shown in the Table 8, scenario 2 exhibits the lowest electricity procurement costs, followed by scenario 4. This is because both scenarios incorporate an electricity pricing-based demand response mechanism. Price signals serve as the core driver of this mechanism, which is designed to steer users toward adjusting how they consume electricity, thereby encouraging users to implement “peak shaving and valley filling” operations to some extent. This, in turn, helps achieve the goal of minimizing electricity procurement costs.

A detailed analysis of the data reveals that the lower cost in scenario 2 stems from the following: during peak periods, increased user consumption triggers the price linkage mechanism of the PDR, causing the variable portion of the electricity price to rise accordingly. This results in peak-period prices being higher than the base rate. During off-peak hours, reduced electricity demand causes the variable price component to decrease, potentially even resulting in negative adjustments, leading to slightly lower off-peak rates compared to the base rate. However, since peak-hour consumption volumes far exceed off-peak levels, overall electricity procurement costs only show a marginal increase.

Simultaneously, electricity procurement cost of scenario 4 increases by only 0.12% compared to scenario 2, yet it boosts the renewable energy absorption rate by approximately 0.4%. Moreover, this increase in absorption rate will continue to expand as renewable energy output within the IES grows. In large-scale IES scenarios, the effect of increasing renewable energy absorption rates becomes more pronounced. This demonstrates that the fluctuating electricity pricing calculation method proposed in this paper possesses certain advantages in promoting renewable energy absorption, thereby contributing to the low-carbon development of IES to a certain extent.

Effectiveness analysis of dynamic carbon trading model and dynamic energy efficiency model

Simulation analysis case design

While keeping other modeling components unchanged, simulations were conducted for the following four scenarios using a summer day as the study case:

Scenario 1: Annual average carbon quota + dynamic energy efficiency

Scenario 2: Annual average carbon quota + fixed energy efficiency

Scenario 3: Dynamic carbon quota + dynamic energy efficiency

Scenario 4: Dynamic carbon quota + fixed energy efficiency

Analysis of simulation results

Hourly values for various costs under each scenario are shown in Fig. 7.

The costs for each scenario are shown in Table 9.

Compared to the scenario with annual average carbon quota + fixed energy efficiency, the dynamic and annual carbon trading cost reductions for the remaining three scenarios are shown in Table 10.

Figure 7 illustrates the primary components of hourly total costs across four scenarios. Subfigure (a) exhibits a steeper peak, while subfigure (c) shows a relatively flatter peak. This demonstrates that employing a dynamic carbon trading model effectively optimizes the system’s cost structure, mitigates peak-valley effects, and reduces overall system costs. Comparing Subfigures a and b, the fixed energy efficiency model exacerbates peak-valley cost differences while effectively reducing overall costs, particularly during peak electricity consumption periods. The dynamic energy efficiency model demonstrates a more pronounced cost-reduction effect. This occurs because during peak electricity consumption, equipment operates at higher efficiency, reducing costs associated with purchasing electricity, gas, and carbon credits. Simultaneously, based on the dynamic carbon quota calculation formula, the system acquires more carbon quotas, ultimately lowering total system costs and effectively mitigating peak-valley effects.

As shown in Table 9, using this case study (a summer day) as an example, the proposed dynamic energy efficiency model combined with the dynamic carbon trading model significantly optimizes the system’s total cost. Compared to the traditional annual average carbon quota model with a fixed energy efficiency model, this model reduces the system’s total cost from 393,617 yuan to 342,145 yuan, and carbon trading costs from 248,340 yuan to 219,607 yuan. This represents a 13.07% reduction in total costs and an 11.57% decrease in carbon trading costs, fully validating the superior cost control capabilities of this coupled model. This is primarily because traditional annual average carbon quotas overlook seasonal emission imbalances, while fixed energy efficiency fails to account for dynamic operational conditions, often leading to redundant carbon costs or energy efficiency waste. In contrast, the dynamic energy efficiency model in this paper adapts in real-time to fluctuations in system operating states, while the dynamic carbon trading model aligns with seasonal carbon emission characteristics and equipment energy efficiency profiles across different time periods, enabling dynamic quota adjustments.

Further analysis of the optimization contributions from each model component reveals that compared to standalone approaches like “annual average carbon trading model + dynamic energy efficiency model” or “dynamic carbon trading model + fixed energy efficiency model”. The coupled model achieves cost reductions of 1.13% and 7.02%, respectively. This result indicates synergistic optimization between the “operating condition adaptability” of dynamic energy efficiency and the “emission period adaptability” of dynamic carbon trading. Their integration overcomes the limitations of single-model optimization, achieving a coupled optimization effect where “1+1>2” and providing a more comprehensive solution for system cost control.

As shown in Fig. 8, during IES operation, equipment efficiency varies with load changes rather than remaining constant. Therefore, establishing dynamic energy efficiency models for equipment is essential. Dynamic models more accurately describe IES equipment performance, enabling subsequent modeling—such as gas and electricity procurement—to better align with engineering realities and achieve greater precision, holding significant importance for practical applications.

Analysis of data from Table 10 reveals significant variations in carbon trading cost reduction rates across seasons among different models. These differences correlate with how well each model integrates dynamic energy efficiency with seasonal carbon quota characteristics. When considering only dynamic energy efficiency models, annual fixed carbon quota limit adaptation to seasonal equipment operation patterns, resulting in low reduction rates throughout the four seasons - averaging just 1.03% annually. When only the dynamic carbon trading model is applied, although dynamic carbon quotas are considered, the fixed energy efficiency assumption deviates from reality. Reduction rates are relatively high in spring, summer, and autumn. However, the winter reduction rate decreases due to more pronounced deviations between equipment winter operation characteristics and fixed energy efficiency assumptions, resulting in an annual average of approximately 6.44%. In contrast, the combined dynamic energy efficiency and dynamic carbon allowance approach fully aligns with equipment high-efficiency operation and flexible carbon allocation during spring, summer, and autumn. Although winter reduction rates are slightly lower due to seasonal energy efficiency variations in some equipment, overall high seasonal reduction levels are achieved, with an annual average of 10.92%. This highlights the adaptive advantage of synergistic dynamic energy efficiency and dynamic carbon allowances in optimizing carbon trading costs across different seasons.

Simulation analysis of DRO model

To validate the effectiveness of the distributed price-responsive demand response and dynamic carbon trading model under the DRO framework, this study decomposes the model components using the weighting coefficient as an example. Each component is then validated through distinct case studies.

Evaluation of the DRO model

To testify the vital function of the DRO model, simulation experiments were conducted for stochastic optimization (SO), traditional robust optimization (RO), and DRO while keeping all other modeling aspects consistent. Six evaluation metrics were derived and compared: total system cost, electricity procurement cost, natural gas procurement cost, the cost of carbon trade, the cost of system operation, and CCS operation cost.

Table 11 presents daily cost values in categories (in CNY) for four scenarios. Data from Table 12 indicate that the DRO model, which describes uncertainty using fuzzy sets to balance conservatism and feasibility, incurs total costs 0.19%, 4.03%, 7.66%, and 8.01% higher than the SO model in the four scenarios, respectively. This increase stems from the SO model’s reliance on deterministic probability distribution assumptions. This result demonstrates that the DRO model is more conservative than SO, overcoming SO’s heavy reliance on probability distributions. It better accounts for cost fluctuations under worst-case scenarios involving uncertain parameters, thereby enhancing the robustness of scheduling solutions.

Simultaneously, the total cost of the DRO model decreased by 4.6%, 4.7%, 2.8%, and 3.0% compared to traditional RO models. This indicates that while preserving its core robustness advantage (ensuring minimized worst-case costs), DRO effectively reduces the conservative redundancy of traditional RO by dynamically optimizing the uncertainty set boundary. This significantly enhances the model’s economic efficiency, achieving the dual objectives of “controlling worst-case risks” and “optimizing overall dispatch costs.”

Simulation analysis under extreme conditions

To demonstrate the model’s effectiveness under extreme conditions, simulation analysis under such scenarios is conducted. To simulate real-world extremes, a scenario is defined where renewable energy output and load-side demand fluctuate by 50% and 30% respectively relative to historical averages over a continuous 10-hour period within a single day. Analysis focuses on two metrics under this scenario: total system cost and imbalance between supply and demand for SO, traditional RO, and DRO systems. Simulation results are as following Table 12.

As shown in Table 12, under the extreme conditions described earlier in this paper, the three optimization methods exhibit significant differences in cost and supply-demand balancing performance. Traditional SO relies on predefined probability distributions to optimize expected costs but lacks robustness against extreme scenarios not covered by the distribution, thus serving as the baseline for subsequent performance comparisons; RO designs solutions based on absolute boundaries of uncertainty parameters, maximally addressing extreme fluctuations: while increasing costs by 19.67% compared to SO, it reduces the supply-demand imbalance by 20.42%. However, its excessive coverage of extremely rare extreme values leads to significant conservative redundancy and higher system costs; The DRO approach adopted in this paper achieves a balance between risk and conservatism through an uncertain set of probability distributions: on one hand, by covering reasonable extreme scenarios rather than RO’s absolute boundaries, it reduces the supply-demand imbalance by 15.56% compared to SO while only increasing costs by 8.08% over SO, effectively mitigating SO’s mismatch risk in extreme scenarios; On the other hand, while DRO achieves a 6.11% lower reduction in supply-demand imbalance compared to RO, it reduces total system costs by 9.68%, eliminating the redundancy costs incurred by RO’s excessive conservatism.

Combining the findings of sections “Evaluation of the DRO model” and “Simulation analysis under extreme conditions”, the proposed DRO model demonstrates both scientific rigor and engineering practicality. It adheres to the core logic of DRO, controlling worst-case risks within reasonable uncertainty, while overcoming RO’s limitation of trading robustness for high costs. This achieves a balance between robustness and economy, avoids resource waste from redundant design, and provides a more practical optimization solution for efficient system operation under extreme conditions, which holds significant engineering significance.

Analysis of norm constraint parameters

For case 4, different confidence levels were assigned to \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _\infty\) within the robust optimization model. For comparison, simulations were conducted under three scenarios: constraining only \(\alpha _1\), constraining only \(\alpha _\infty\), and simultaneously constraining both \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _\infty\). The total cost of each situation were derived and analyzed comparatively.

As shown in Fig. 9, increasing the values of relevant parameters progressively enhances the conservatism of the optimization model. A higher value of [the confidence parameter] signifies that the model places greater emphasis on addressing extreme scenarios throughout the optimization process. In such cases, the system develops and implements more prudent scheduling strategies to reduce potential risks. However, such a conservative strategy results in higher consumption of redundant resources, ultimately driving up the system’s operational costs. This clearly demonstrates the unavoidable trade-off that exists between risk prevention and cost escalation.

Comparing scenarios with single-norm constraints versus combined-norm constraints reveals consistent trends: combined-norm constraints typically achieve more effective cost reduction than single-norm constraints. For instance, under the scenario \(\alpha _{\infty }=0.95\) , the cost with a single-norm constraint is 355,843 yuan, whereas the combined-norm constraint reduces it to 347,212 yuan, which means a decrease of approximately 2.43%. This result demonstrates that combined norm constraints are capable of effectively alleviating the cost escalation triggered by conservative optimization, all the while safeguarding system stability. Consequently, they achieve higher levels of economic efficiency and scheduling flexibility, demonstrating significant advantages when applied as constraints in DRO.

Intraday DRO-MPC two-stage forecasting model evaluation

Sources of forecast data

Just as with day-ahead scheduling, intraday scheduling faces uncertainty primarily from variations in renewable energy generation and different types of energy loads. Therefore, this research introduces a 5% random error into the day-ahead forecast data, which is used to mimic the intraday fluctuations of both renewable energy and load. The MPC forecast data source is illustrated in Fig. 10.

Determination of the electricity price penalty coefficient

During the modeling process, the electricity price penalty coefficient remains undetermined. To identify the optimal coefficient, sensitivity analysis simulations were conducted by varying within the range [0, 0.8] with increments of 0.05. The total cost and electricity price fluctuation optimization results under different values were compared. The final optimal value of was selected as the coefficient that minimizes total cost while keeping electricity price fluctuation within an acceptable range (\(\le\)10%). The trends of total cost and daily electricity price fluctuation total value with respect to the electricity price penalty coefficient are shown in Fig. 11.

As shown in the Fig. 11, when \(\rho =0.3\), both total cost and electricity price fluctuation reach their minimum values. Therefore, all simulations in this paper adopt \(\rho =0.3\) as the value of the electricity price penalty coefficient.

DRO-MPC scheduling cases and reference metric settings

Three comparative cases were established for this study. The computational duration, total cost, and tracking error were simulated as comparison metrics across these cases. The tracking error is the integral of the discrepancy between the result of rolling optimization and the actual situation in the corresponding time interval, quantifing the tracking effectiveness of MPC. Specifically shown as follows:

-

Case 1: Uses the DRO-MPC model without feedback correction

-

Case 2: MPC model with feedback calibration, but without DRO

-

Case 3: DRO-MPC model with feedback correction

The results are as following Table 13.

The comparison between tracking results and reference values for each case is shown in Fig. 12.

As indicated by the data in Table 13, case 2 exhibits the lowest cost and highest economic efficiency. This is attributed to the model’s higher optimization freedom combined with feedback correction, which enables real-time optimization of prediction strategies to minimize total costs. Compared to case 2, case 1 lacks a feedback correction mechanism, resulting in poorer adaptability to actual conditions and higher total costs. Case 3 employs DRO to handle extreme conditions, incorporating redundant costs into the total cost calculation, making it the most expensive model. However, this trade-off between increased total cost and computational time yields enhanced system robustness, as detailed in section “Comparison of DRO-MPC and MPC under extreme conditions”.

Regarding tracking accuracy, case 2 exhibits the smallest tracking error. Compared to case 2, case 3’s tracking error increases by approximately 5.22%. This occurs because in the DRO-MPC model, the MPC prediction must be based on the DRO optimization results, which partially sacrifices tracking optimality and consequently reduces tracking accuracy. Compared to case 2, case 1 exhibits the lowest tracking accuracy, showing a significant increase relative to both case 2 and case 3. This is because case 1 does not employ a feedback correction mechanism, resulting in insufficient system tracking capability for actual conditions and ultimately increasing the tracking error.

Figure 12 illustrates the hourly comparison of predicted and reference values across the three cases. The figure clearly shows that without feedback correction, the error between predicted and reference values is substantial. When using MPC optimization alone, the system exhibits low conservatism and significant fluctuations. In contrast, DRO-MPC optimization maintains tracking accuracy without significant degradation, while markedly improving system conservatism and reducing fluctuations

Comparison of DRO-MPC and MPC under extreme conditions

Since DRO primarily minimizes losses under worst-case scenarios, simulations of the system under extreme conditions are conducted to validate the proposed DRO-MPC model. These extreme conditions mirror those described in section “Simulation analysis under extreme conditions” of this paper. Comparisons are made across five metrics: total cost, renewable energy absorption rate, tracking accuracy, load curtailment rate, and computer data processing time.

As shown in Tables 13 and 14, when fluctuations in load, photovoltaic and wind power output, are all significant, the DRO-MPC model still maintains high prediction accuracy. Its tracking error increases from 38.965 to 40.133, representing a mere 3.0% rise. In contrast, when using only the MPC model, the tracking error increased from 37.032 to 46.641, a substantial rise of 20.6%. This highlights that traditional MPC optimization suffers from significant prediction errors under high system uncertainty, indicating very low robustness. The DRO-MPC model, however, effectively enhances the robustness of MPC.

Comparing data on total cost, renewable energy absorption rate, and electricity load reduction rate reveals that under extreme conditions, the DRO-MPC model’s high robustness resulted in smaller increases for all three metrics compared to using MPC alone. Correlating this with relevant data from Tables 13 and 14, it demonstrates that the DRO-MPC model effectively enhances the system’s ability to manage risks under extreme conditions, safeguards user electricity demand during such events, and reduces power outage occurrences.

Meanwhile, in terms of computational time, the DRO-MPC model took 196.4 seconds to compute, with conventional forecasting operating at a 1-hour time scale. This demonstrates that although DRO-MPC exhibits a significant increase in computational time compared to MPC, it remains capable of meeting forecasting time scale requirements in engineering applications. It effectively extends the robustness enhancement of DRO from the day-ahead scale to the intraday scale, mitigating the time scale mismatch issue in DRO’s intraday optimization.

Disscusion

This study constructs an IES economic dispatch optimization model for electricity pricing-based demand response, incorporating dynamic energy efficiency and dynamic carbon trading. It proposes a two-stage collaborative optimization framework: “Day-ahead DRO – Intraday MPC.” Simulation results demonstrate that this framework achieves significant improvements in system economics, robustness, and low-carbon performance. This section provides an in-depth interpretation of the above results and discusses them within a broader academic context.

Theoretical and practical significance of the research

Theoretically, the proposed “dynamic energy efficiency-dynamic carbon quota” coupling mechanism establishes a new paradigm for low-carbon scheduling modeling in IES, emphasizing that carbon cost optimization should not be decoupled from the physical operational state of system equipment. Concurrently, the DRO-MPC framework offers a versatile modeling and solution approach for addressing multi-timescale uncertainty optimization problems.

At the practical level, this research provides IES operators with scheduling tools that balance economic efficiency and robustness. The dynamic carbon trading model assists enterprises in more precise cost budgeting and trading decisions within carbon markets. Meanwhile, the price-elasticity-based MPC rolling optimization strategy offers theoretical foundations and technical support for designing more flexible real-time electricity pricing products for electricity retailers or aggregators.

Research limitations and future directions

Despite the achievements outlined above, this study retains several limitations that also point to directions for future research.

Research limitations

-

Simplified Modeling of Renewable Generation and Load Uncertainty: The uncertainty modeling focuses on short-term, hourly fluctuations of wind and photovoltaic output and load demand derived from historical data. It does not incorporate the impacts of extreme weather events, long-term climate variability, or the spatiotemporal correlations between different renewable sources and load nodes. The initial probability distributions for the DRO model are constructed from historical data, which may not fully capture future uncertainty patterns.

-

Static Approximation of Behavioral Response: Although the electricity price elasticity matrix incorporates a feedback correction mechanism, its initial values are derived from historical data fitting. The correction weight \(\omega\) is manually set. This approach does not fully capture the potential dynamic evolution of user response behavior driven by long-term learning effects, seasonal habits, or sudden changes in policy or market structure.

-

Assumption of a Perfectly Competitive Carbon Market: The dynamic carbon trading model operates under the assumption of a perfectly competitive carbon market with fixed price tiers. It does not account for potential carbon price volatility induced by policy shocks, market speculation, or strategic bidding behaviors of large market participants, which could significantly impact operational costs.

-

Computational Burden for Large-Scale Systems: Solving the proposed DRO-MPC framework relies on iterative algorithms like C&CG. While tractable for the case study presented, computational efficiency may become a bottleneck for very large-scale IES with hundreds of units or when applied to shorter, real-time dispatch cycles requiring solutions within minutes.

Future outlook

To address the aforementioned research gaps, future studies of the model could focus on the following areas:

-

Develop coupled models integrating numerical weather prediction, artificial intelligence algorithms, and renewable energy output forecasting to enhance the climate adaptability of dispatch strategies and improve prediction accuracy.

-

Employing online learning methods like reinforcement learning to establish adaptive mechanisms for updating elasticity coefficients.

-

Incorporate carbon price uncertainty into the fuzzy set of DRO to develop more robust carbon market models, and further explore cross-regional carbon trading and coordinated dispatch mechanisms under multi-regional IES alliances.

-

Future research may explore developing distributed optimization algorithms, deep learning proxy models, or leveraging hardware acceleration technologies to enhance the model’s real-time application potential.

-

Extend the current single-node IES model to multi-regional interconnected systems, investigate cross-regional energy exchange and carbon quota trading mechanisms, and further enhance overall system economic efficiency and low-carbon performance.

-

In future research, incorporating incentive-based demand response (IDR) could further enhance the system’s peak shaving and valley filling capabilities. For instance, integrating IDR with PDR to develop a hybrid demand response model warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

This paper conducts systematic research on three core issues in IES economic dispatch: electricity price fluctuations, dynamic characteristics of equipment energy efficiency, and dynamic carbon trading. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

The effectiveness of the multi-timescale collaborative optimization framework. A two-stage DRO-MPC collaborative optimization strategy is proposed: The day-ahead stage employs data-driven DRO, incorporating \(\infty\)-norm and 1-norm constraints to model price and load uncertainties, addressing the limited adaptability of traditional SO to extreme scenarios. The intraday MPC stage integrates MPC with an electricity price elasticity coefficient matrix to construct state equations. It dynamically adjusts electricity prices through rolling optimization and employs a feedback correction mechanism to update elasticity coefficients in real time. This two-stage strategy embeds DRO robustness into MPC optimization, satisfying both the intraday forecasting time scale requirements and enhancing the robustness of the prediction model. Under extreme conditions of 50% renewable output fluctuation and 30% load fluctuation, tracking error increases by only 3.0%. Compared to traditional MPC models, load curtailment rate decreases by 4.15%, while renewable energy absorption rate increases by 10.1%.

-

Synergistic Benefits of Dynamic energy efficiency and Dynamic Carbon Trading. A polynomial relationship model linking equipment load factor and energy efficiency replaces the traditional fixed-efficiency model, making system modeling more aligned with engineering realities. Concurrently, this paper proposes a seasonal-based tiered carbon quota allocation mechanism. Combined with dynamic energy efficiency correction factors, this enables carbon quotas to adjust dynamically based on actual equipment output and energy efficiency. This model dynamically adjusts quotas for units with higher summer carbon intensity based on equipment output and the proportion of seasonal emissions relative to annual emissions. It reduces the cost of carbon trade in summer by 10.7% and annual costs of IES by 9.89%, representing a 2.88% greater reduction in summer costs compared to13. Compared to the fixed quota plus annual average quota model, the dynamic efficiency plus dynamic quota coupling model reduces total system costs by 13.07%. This finding serves to substantiate the assertion that dynamic carbon trading models are instrumental in reducing carbon emissions and costs, while concurrently demonstrating the synergistic effect of the “dynamic efficiency-seasonal quota” coupling mechanism.

-

Effectiveness of real-time electricity pricing models considering load and renewable energy output. The impact of TOU electricity prices was quantified using an elasticity coefficient matrix. Renewable energy output and load fluctuations were incorporated into the real-time electricity price calculation model. Feedback correction was employed to integrate electricity price elasticity coefficients into MPC forecasting, enhancing the accuracy of intraday load fluctuation tracking. Case studies demonstrate that incorporating load and renewable energy output into the real-time electricity price fluctuation model increases peak-hour electricity procurement costs by only 0.12%, while boosting renewable energy absorption rates by 0.4%.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due some of the data in the paper were obtained from a certain comprehensive energy system in Nanchang. The person in charge of that system requested us to keep the data confidential, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. To contact the corresponding author, please send an email to yangxiaohui@ncu.edu.cn.

References

Siqin, Z. et al. Distributionally robust dispatching of multi-community integrated energy system considering energy sharing and profit allocation. Appl. Energy 321, 119202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119202 (2022).

Institute, C. E. P. P. E. Chinese power system transformation report. https://www.nea.gov.cn (2025).

Liu, Z. et al. Multi-time scale operation optimization for a near-zero energy community energy system combined with electricity-heat-hydrogen storage. Apply Energy 291, 130397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.13039 (2024).

Wen, L. et al. Co-optimization of system configurations and energy scheduling of multiple community integrated energy systems to improve photovoltaic self-consumption. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 71, 1439–1451. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2022.3158390 (2024).

Wu, J., Chen, R., Qu, H. et al. Robust optimization method for integrated energy system considering uncertain electricity price. In 2024 4th International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Information Engineering (ECIE) 308–312 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ECIE61885.2024.10627463.

Wang, Z. & Paranjape, R. Optimal residential demand response for multiple heterogeneous homes with real-time price prediction in a multiagent framework. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 8, 1173–1184. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2015.2479557 (2017).

Li, L., Yuan, Z. & Li, J. Three-stage stochastic robust day-ahead optimization of hydrogen-containing integrated energy system considering source-load multiple uncertainties. Power System Technol. 2025, 256. https://doi.org/10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2025.0327 (2025).

Yang, X. et al. An optimized scheduling strategy combining robust optimization and rolling optimization to solve the uncertainty of res-cchp mg. Renew. Energy 211, 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.04.103 (2023).

Wang, Y., Qiu, D., Sun, X., Bie, Z. & Strbac, G. Coordinating multi-energy microgrids for integrated energy system resilience: a multi-task learning approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 15, 920–937 (2024).

Zhang, L., He, Y., Wu, H. & Hatziargyriou, N. D. An optimal scheduling framework for integrated energy systems using deep reinforcement learning and deep learning prediction models. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 16, 4620–4634 (2025).

Yang, Y., Shi, J., Wang, D., Wu, C. & Han, Z. Net-zero scheduling of multi-energy building energy systems: a learning-based robust optimization approach with statistical guarantees. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 15, 2675–2689 (2024).

Mo, J. et al. Review of demand response-based optimal scheduling of electric and thermal integrated energy systems. Adv. Eng. Sci. 57, 296–307. https://doi.org/10.15961/j.jsuese.202300187 (2025).

Yan, N. et al. Low-carbon economic dispatch method for integrated energy system considering seasonal carbon flow dynamic balance. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 14, 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2022.3220797 (2023).

Xiongg, J. et al. Consider flexible carbon capture power plants with dynamic carbon quotas—a low-carbon economic scheduling for generalized energy storage systems. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 46, 696–705. https://doi.org/10.19912/j.0254-0096.tynxb.2024-0062 (2024).

Xuan, A., Shen, X., Guo, Q. & Sun, H. Two-stage planning for electricity-gas coupled integrated energy system with carbon capture, utilization, and storage considering carbon tax and price uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 38, 2553–2565. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2022.3189273 (2023).

Wei, Z. et al. Low-carbon economic scheduling for integrated energy system based on dynamic hydrogen doping strategy. Power Syst. Technol. 48, 3155–3164. https://doi.org/10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2023.2180 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. Study on cascade optimization operation of park-level integrated energy system considering dynamic energy efficiency mode. Power Syst. Technol. 46, 1027–1038. https://doi.org/10.13335/j.1000-3673.pst.2021.0484 (2022).

Li, W., Kang, J., Sun, H. & Pang, G. Impact of carbon abatement policies on cross-border supply chain remanufacturing: the role of import quotas. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 72, 1281–1296. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2025.3555392 (2025).

Taneja, J., Katz, R. & Culler, D. Defining cps challenges in a sustainable electricity grid. In 2012 IEEE/ACM Third International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems 119–128 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCPS.2012.20.

Hans, M., Hikmawati, E. & Surendro, K. Predictive analytics model for optimizing carbon footprint from students’ learning activities in computer science-related majors. IEEE Access 11, 114976–114991. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3324725 (2023).

Fu, Y. et al. Effects of uncertainties on the capacity and operation of an integrated energy system. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 48, 101625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101625 (2021).

Ma, W., Fang, S. & Liu, G. Demand response performance and uncertainty: a systematic literature review. Energy 141, 1439–1455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.11.081 (2017).

Cui, Y., Zeng, P. & Zhong, W. Low-carbon economic dispatch of electro-gas-thermal integrated energy system based on oxy-combustion technology. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 41, 592–607. https://doi.org/10.13334/j.0258-8013.pcsee.191708 (2021).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. M. is responsible for conceptualization, methodology,proofreading, writing-reviewing and software; Q. D. is responsible for data curation, writing original draft preparation; Z. Z. is responsible for investigation and simulation; X. Y. is responsible for visualization, supervision and validation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mao, H., Deng, Q., Zhang, Z. et al. Optimized economic scheduling of demand response in integrated energy systems considering dynamic energy efficiency and dynamic carbon trading. Sci Rep 16, 1350 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33497-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33497-3