Abstract

This study presents a spatially explicit stochastic agent-based model (ABM) to simulate the complex non-linear interactions between T-cells, HIV virions, and therapeutic agents. The model framework operates on a two-dimensional grid, explicitly modeling biological entities as discrete agents to investigate the effects of antiretroviral drug therapy and specific lifestyle interventions. To benchmark model behavior, three distinct clinical stages of HIV infection were simulated under four comparative intervention scenarios. Quantification across 100 independent stochastic replicates per scenario demonstrated robust findings. The key result is that while antiretroviral drug therapy is essential for immediate viral suppression, the combination of drug therapy and lifestyle factors consistently produces a synergistic effect that leads to favorable long-term T-cell outcomes across all clinical stages simulated. Sensitivity analysis employed to assess the model’s robustness identified the rate of wild-type virus production as the single most critical biological factor for viral control and clarified that the observed synergy stems mechanistically from lifestyle factors that boost T-cell proliferation, thereby improving immune recovery and promoting the clearance of infected T-cells. The comprehensive analysis in this study presents that a holistic management approach, integrating pharmacological and lifestyle interventions, provides a crucial synergistic effect that promotes sustained immune health. The model presented in this study serves as an exploratory framework for investigating optimal and personalized HIV treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The introduction of mathematical models has been crucial in understanding the complex dynamics of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Early models, such as1, provided fundamental insights into studying viral decay process and the lifespan of infected cells, and these frameworks have been expanded by subsequent studies2,3, to include the effects of drug therapy and their interactions between viral load, CD4+ T-cells, latent reservoirs, and immune responses, particularly from cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)4. Recent advancements have also incorporated stochasticity and time delays into these models to better capture the inherent randomness and temporal complexities of the system5,6. There are also significant progress in the development of models that account for multi-drug pharmacokinetics, strain-specific drug effectiveness, and viral mutation dynamics7,8.

Despite these successes, mathematical models which are often based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) operate on the assumption of a well-mixed system, thereby overlooking the crucial spatial interactions between individual cells and virions. Furthermore, some of these models do not thoroughly capture emergent phenomena like the development of drug resistance, which is a consequence of viral mutation and selection pressures from antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, the importance of personalized treatment strategies and dynamic drug dosage schedules has been highlighted through approaches like optimal control and optimization processes9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, but these often remain limited by the deterministic nature of their underlying models.

Agent based modeling (ABM) approach has been successfully applied to a variety of infectious diseases to capture complex dynamics that are often difficult to model with traditional approaches18. For example, ABMs have been used to simulate the spread of influenza19, the transmission of COVID-19 within a population20, and the modeling system of vaccination strategy21. These models are particularly effective at capturing spatial and social network effects, such as how individual movement and contact patterns influence disease transmission22,23.

In the context of HIV case management, ABMs have been used to study various aspects of the disease beyond the foundational work on viral dynamics. Specifically, in the area of intervention and control24, ABMs have been applied to model the impact of different intervention programs and to identify the economic value of these interventions in reducing the spread of the disease25,26. However, the stochastic nature of ABMs can allow a more realistic representation of how random mutations can lead to the selection of resistant viral strains, which is a key clinical challenge. Furthermore, these models, in conjunction with other optimization methods like modern algorithms, can be used to explore the effectiveness of different drug dosage schedules and combination therapies to find optimal treatment strategies.

This work addresses this research gap by introducing a spatially explicit Agent Based Model. Unlike traditional approaches presented in works like10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, the ABM simulates individual biological entities (T-cells, viruses, and drugs) as discrete agents interacting on a two-dimensional grid . The methodology is constructed to capture emergent phenomena like viral mutation and the development of drug resistance, providing a transparent and stochastic framework for understanding the non-linear dynamics of HIV infection and the synergistic effects of therapeutic and lifestyle interventions. The ABM framework presented in this study is solely designed to investigate the effects of antiretroviral drugs and lifestyle factors on viral load and T-cell populations.

Model formulation

Introduction

The model system is formulated to be a discrete-time stochastic simulation on a two-dimensional grid. The state of the system at time step t is defined by the population count and spatial position of each agent type. The simulation progresses from time t to \(t+1\) by applying a series of rules in a fixed order, ensuring a stable causal structure. The model is designed to track the number of healthy T-cells \(N_H(t)\), latent T-cells \(N_L(t)\), active T-cells \(N_A(t)\), wild-type virus particles \(V_{WT}(t)\), resistant virus particles \(V_R(t)\), reverse transcriptase inhibitor drug particles \(D_{RT}(t)\), and protease inhibitor drug particles \(D_{PI}(t)\). The spatial position of each agent is defined by its coordinates (x, y) on an \(80 \times 80\) grid, as interactions are based on Manhattan distance between agents.

Model dynamics

The model is designed such that at each time step t, the state of the system is updated based on certain processes. The infection and viral inactivation is constructed such that at coordinates (x, y), a healthy T-cell \(T_H\), interacts with any wild-type virus \(V_{WT}\), or resistant virus \(V_R\), within an interaction radius, \(r_{int}\). The probability of a successful infection within the system is set to be a function of the virus’s base infectivity and the local concentration of RT-inhibitor drugs \(C_{RT}\). If an infection is successful, the healthy T-cell is removed and a new infected cell is created at the same location. This newly created cell becomes latent T-cell with probability \(P_{latency}\), active T-cell with probability \(1 - P_{latency}\). Similarly, if the infecting virus is a wild-type, a mutation to a resistant strain occurs with probability \(P_{mut}\). In such case, the new active T-cell is of the resistant strain, otherwise, it is a wild-type. Also, if the infecting virus is a resistant virus, the new active T-cell will be a resistant.

For processes involving viral production and cell death, active T-cells produces new virus particles, this process is inhibited by PI drugs. All agent types are subject to stochastic death or decay at each time step based on their respective probabilities given by \(P_{death,H}\), \(P_{death,L}\), \(P_{death,A}\), \(P_{decay,V}\), and \(P_{decay,D}\). Likewise, the latent T-cells can also become reactivated into active T-cells with a probability \(P_{reactivation}\).

Proliferation and agent movement finally takes place as healthy T-cells proliferate with a new T-cell being created at a nearby location with a probability \(P_{prolif,H}\). In scenarios involving lifestyle factors like diet score, exercise score, these probabilities are modified. All agents (T-cells, viruses, drugs) undergo random movement on the grid at each time step and their new position \((x',y')\), is determined by adding a random displacement \(\pm 1\) or 0 in both x and y directions to their current position (x, y), ensuring they remain within the grid size boundaries.

Governing equations

The core dynamics of the model are governed by a set of stochastic equations, defined for each time step. The effective probability of a healthy T-cell becoming infected by a virus of strain S is calculated based on the local drug concentration, the number of new virus particles produced by an active T-cell of strain is dependent on the local concentration of protease inhibitor drugs and the base probabilities for healthy and active T-cell dynamics are altered by lifestyle scores, representing the effects of diet and exercise.

If given \(C_{RT}(x,y)\) to be the number of reverse transcriptase inhibitor drug particles within the interaction radius of a healthy T-cell at position (x, y), then we have

and

as the infection probability.

Similarly, let \(C_{PI}(x,y)\) be the number of protease inhibitor drug particles within the interaction radius of an active T-cell at position (x, y), then we have viral production given by

For lifestyle modifications, we set \(S_{diet}\) and \(S_{exercise}\), to be the scores for diet and exercise, respectively to have

Model algorithmic description

To ensure the maximum degree of reproducibility and clarity, the precise sequence of events and stochastic rules is formalized in Algorithm 1. This sequential update ensures that events like drug administration precede infection, and infection precedes cell death, providing a stable causal structure. The underlying MATLAB source code for this simulation will be made publicly available via a repository.

Table of model parameters

Simulation and results

o benchmark the model’s qualitative behavior and quantify uncertainty, the model was simulated using 100 independent stochastic replicates for all four intervention scenarios across three distinct clinical stages. The model parameters were calibrated to align with established public health and medical data on CD4+ T-cell counts and HIV viral load measurements, as specified by public health authorities32. For each case study (case 1 to case 3), the model was simulated using four scenarios, no treatment, drug therapy, patient lifestyle changes, and a combination of drugs and lifestyle interventions. The model case 1 captures the simulation of a chronic asymptomatic infection. This scenario models a patient in the long-lasting, untreated phase of HIV where the virus and the immune system are in a state of clinical equilibrium. The initial conditions are set to \(N_H\) = 1000, \(N_L\) =1, \(N_A\) = 500, \(V_{WT} = 1000\), and \(V_R\) = 0. Clinically, this case reflects a patient with a normal CD4 count and a moderate viral load, a characteristic of a chronic phase where the immune system successfully manages but does not eliminate the virus. The model case 2 simulates a patient in the early acute stage of HIV infection, where the virus is beginning to rapidly replicate. The initial conditions are set to \(N_H\) = 1400, \(N_L\) =0, \(N_A\) = 100, \(V_{WT} = 500\), and \(V_R\) = 0. This represents a patient with a high CD4 count, which is a characteristic of the acute phase before significant immune damage has occurred. The model case 3 simulates a patient with advanced stage infection, clinically defined as AIDS, where the immune system is severely compromised. The initial conditions are set to \(N_H\) = 150, \(N_L\) = 10, \(N_A\) = 2000, \(V_{WT} = 10000\), and \(V_R\) = 50. The high viral load of 10,000 copies/mL and severely low healthy T-cell count are signs of advanced untreated disease. The numerical values for the simulation parameters were sourced from the detailed biological data available in the literature, as cited in the model parameters Table 1. The model’s endpoint analysis at \(T=90\) is summarized quantitatively in Tables 2, 3, and 4, reporting the mean and \(90\%\) Confidence Interval (CI) for Healthy T-cells (\(N_H\)) and Total Virus Count (\(V_{Total}\)). A sensitivity analysis was performed to quantify the influence of the model’s key input parameters on the final Healthy T-cell population (\(\bar{N}_H\)) and Total Virus population (\(\bar{V}_{\text {Total}}\)). Each parameter was varied by \(\pm 20\%\) from its baseline value, and the resulting change in model output was reported using the Normalized Sensitivity Index presented in Table 5.

Discussion of results

The model was simulated across the three clinical stages of HIV infection to benchmark its ability to capture the disease’s diverse dynamics and the impact of various interventions. The analysis presented are supported by the statistical endpoint summaries (Tables 2, 3, 4), providing a breakdown for each model case study by comparing the outcomes of four distinct scenarios across key patient metrics, healthy \(\text {T}\)-cells, total virus count, active \(\text {T}\)-cells, and resistant virus. The simulation for the chronic asymptomatic infection (model case 1), presented in Fig. 1, demonstrates the long-term equilibrium characteristic of this stage. In the No Treatment scenario, the mean healthy \(\text {T}\)-cell count showed a persistent decline to a mean of 106, consistent with the gradual immune damage of an untreated chronic infection. However, drug therapy led to a significant recovery in \(\text {T}\)-cell count, with the Drugs Only scenario reaching a mean of 1122, and the Drugs + Lifestyle combination therapy yielding the highest long-term mean count of 1293 as presented in Table 2. The Lifestyle Only scenario had a limited effect, resulting in a final mean of 115, with no statistical distinction from the No Treatment outcome. While the viral load in the No Treatment scenario remained relatively stable with a mean of \(8.80\textrm{e}-01\), this reflects a fragile equilibrium, the Drugs Only and Drugs + Lifestyle scenarios disrupted this balance, leading to a rapid and sustained viral suppression to a persistent low level mean \(1.80\textrm{e}-01\) and \(2.30\textrm{e}-01\), respectively. The Lifestyle intervention showed only a temporary viral mitigation before its viral load stabilized at a higher level (mean \(5.40\textrm{e}-01\)). The count of active \(\text {T}\)-cells dropped significantly in all scenarios as the initial viral replication was contained/suppressed. Regarding the resistant virus population, the statistical mean remained at 0.00 throughout all scenarios, indicating that the efficacy of the interventions prevented its persistent emergence within the simulation’s period.

The Early Acute Infection (Case 2), presented in Fig. 2, demonstrates the effect of early intervention on disease progression. In the No Treatment scenario, the healthy T-cell count declined severely from 1400 to a mean of 423 as the untreated infection began to wear down the immune system. In contrast, both the Drugs Only and Drugs + Lifestyle scenarios led to maximal immune restoration. The Drug + Lifestyle combination yielded a superior mean outcome of 2347 T-cells, which is significantly higher than the Drugs Only mean of 2038 as presented in Table 3. On the viral load, the No Treatment scenario showed a characteristic viral spike. Both the Drugs Only and Drugs + Lifestyle scenarios successfully prevented this spike and led to complete viral clearance (mean \(V_{Total} = 0.00\)), confirming the effect of early drug intervention. Notably, the Lifestyle Only scenario also significantly mitigated the initial spike and decline, showing that lifestyle changes can enhance the body’s natural defense, but it was insufficient for viral clearance (mean \(V_{Total}=1.10\textrm{e}+02\)). The count of active T-cells peaked around the same time as the viral spike in the untreated and lifestyle only scenarios, as the body immune system ramped up to fight the infection. However, similar to Case 1, the resistant virus population remained at zero in all scenarios.

The simulation for Case 3, representing the advanced stage of AIDS, demonstrated the severe pathological consequences of advanced infection and the critical role of intervention. As shown in Fig. 3, the No Treatment and Lifestyle Only scenarios led to a rapid decline in healthy T-cells, resulting in a consistent immune system collapse (mean \(N_H = \textbf{0}\) for both, see Table 4). In contrast, both the Drugs Only and Drugs + Lifestyle scenarios promoted a survival-level recovery of the healthy T-cell population, with the combination therapy yielding the highest long-term mean count of 27 against 24 for Drugs Only. The total virus plot explains the model drug dynamics by showing that in the No Treatment and Lifestyle Only scenarios, the virus remained dominant and uncontrolled. Conversely, the Drugs Only and Drugs + Lifestyle scenarios resulted in immediate and sustained viral load suppression. The high initial count of active T-cells, which served as viral production source, dropped significantly across all scenarios, confirming that the interventions successfully contained the infection. Crucially, the statistical figures confirms that the resistant virus population failed to establish a persistent presence in this case (mean \(V_R = 0.00\)) across all scenarios, including both Drug-Only and Drug + Lifestyle, implying that the model’s parameters suppressed \(V_R\) before it could become self-sustaining.

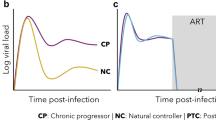

The results presented in this study, provide a robust foundation for a comprehensive discussion. The analysis across all the three clinical stages not only benchmarks the model’s behavior but also offers new insights into the complex dynamics of HIV case management. The model presented in this study elucidates key pathological trajectories of HIV infection, mirroring established clinical understanding. For instance, in Early Acute Infection (case 2), the simulation captures core details of primary infection which is characterized by a rapid viral spike followed by the immune system’s containment response. Similarly, the Chronic Asymptomatic (Case 1) simulation demonstrated a distinct clinical equilibrium where a stable viral load coexisted with a slow but persistent decline in healthy T-cells, accurately reflecting a long-term and low-grade immune damage. The Advanced Stage AIDS (Case 3) simulation also confirmed a state of catastrophic immune collapse, where the host defenses are completely overwhelmed by the viral load.

The model’s ability to reproduce these distinct stages validates its relevance as a theoretical framework for studying HIV pathogenesis. The comparative analysis of the four scenarios also provides crucial insights into the effectiveness of different interventions. The results underscore the impact of drug therapy, which consistently led to immediate and sustained viral suppression across all stages. However, the most significant finding is the consistent statistically supported synergistic effect of combining drugs with lifestyle interventions. As clearly seen from the model figures, lifestyle interventions alone demonstrated a limited capacity to manage viral load in the acute phase, but when combined with ART drug therapy, they promoted the highest level of T-cell proliferation and recovery. In the Advanced Stage, while drug therapy was a critical intervention for preventing immune collapse, the combination with lifestyle gives a statistically superior treatment process. The complete absence of a persistent resistant virus population in the combination scenario, as well as the drug-only scenario, highlights that the current model parameters lead to overwhelming viral suppression. This results affirms that while aggressive drug therapy is essential for controlling viral load, a multi-faceted approach that incorporates patient lifestyle factors provides a crucial added benefit, particularly in promoting long-term immune health.

The quantitative basis for these dynamics is provided by the sensitivity analysis presented in Table 5 and Fig. 4. The analysis identified the key mechanistic drivers governing the system’s long-term state which can help informing public health strategy. The most critical parameter for viral suppression is the Wild-Type Virus Production Rate (\(\text {V}_{\text {prod,WT,base}}\)), which showed the highest overall sensitivity index of 1.20, confirming that targeting viral generation is the primary control point of the disease. For maintaining T-cell health, the \(\text {Healthy T}\)-cell population (\(\text {N}_H\)) is primarily a struggle between Proliferation (\(P_{\text {prolif,H}}\)) with 0.196 and \(\text {V}_{\text {prod,WT,base}}\) with -0.188. Crucially, the analysis offered a clarification regarding the synergistic role of lifestyle factors. The sensitivity results show that promoting healthy \(\text {T}\)-cell creation (\(f_{\text {exercise,prolif}}\)) can be counter-productive for viral suppression, as it increases the supply of uninfected target cells for the residual virus. In contrast, the lifestyle factor promotes the removal of active infected \(\text {T}\)-cells (\(f_{\text {exercise,death,A}}\)) showed a strong negative sensitivity of -0.40, indicating that therapeutic efforts that enhance the clearance of viral production are highly effective at controlling viral load. This sensitivity analysis reinforces the conclusion that the combination therapy will be multi-pronged, leveraging drug therapy for viral production/infection blockade and lifestyle interventions for immune regeneration and the targeted removal of infected cells.

The findings of this study suggest that health practitioners should integrate lifestyle counseling and move beyond simply prescribing antiretroviral drug for HIV patients. The model provides computational evidence supporting the clinical recommendation that HIV patients should be counseled on the importance of diet and exercise as an integral components of their treatment plans. Public health practitioners should advocate for programs that combine traditional services with patient-centered support, such as nutrition counseling, exercise/keep-fit programs, and mental health services.

Conclusion

This work introduces a spatially explicit Agent-Based Model (ABM) to study HIV case management, presenting a shift from the known traditional ordinary differential equations to simulate individual cell-virus interactions in a stochastic environment, and to assess the emergent dynamics of intervention. The study leverages 100 independent stochastic replicates and a comprehensive sensitivity analysis, to provid a clear quantitative evidence required to establish key findings. The study’s key finding is the consistent statistically supported synergistic effect of combining antiretroviral therapy (ART) with patient lifestyle interventions, leading to optimal long-term immune recovery. Mechanistic insight from the sensitivity analysis clarifies this synergy, pharmacological intervention blocks viral generation, while lifestyle factors actively promote \(\text {T}\)-cell immune regeneration and targeted clearance of infected cells. This computational evidence carries significant public health relevance, demonstrating that a holistic management approach is superior for sustained immune health. The study recommends clinical and policy adoption of patient counseling on diet and exercise as a fundamental components of HIV care, moving beyond solely pharmacological prescription. For future work, the ABM can be expanded to address key biological complexities, including better modeling of drug resistance and integrating detailed mechanisms such as Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte (CTL) activity and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) processes.

Data availability

Data used to support the findings in this study are included in the article. The authors used a set of parameter values whose sources are from the literature as shown in Table 1.

References

Perelson, A. S., Neumann, A. U., Markowitz, M., Leonard, J. M. & Ho, D. D. Hiv-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science 271(5255), 1582–1586. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.271.5255.1582 (1996).

Rivadeneira, P. S. et al. Mathematical modeling of hiv dynamics after antiretroviral therapy initiation: A review. Biores. Open Access 3(5), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1089/biores.2014.0024 (2014).

Perelson, A. S. et al. Decay characteristics of hiv-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 387(6629), 188–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/387188a0 (1997).

Rasi, G., Emili, E., Conway, J. M., Cotugno, N. & Palma, P. Mathematical modeling and mechanisms of hiv latency for personalized anti latency therapies. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 11(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00538-6 (2025).

Jin, R. & Zhang, L. Ai applications in hiv research: advances and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1541942. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1541942 (2025).

Sadee, W., Wang, D., Hartmann, K. & Toland, A. E. Pharmacogenomics: Driving personalized medicine. Pharmacol. Rev. 75(4), 789–814. https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.122.000810 (2023).

Rosenbloom, D. I., Hill, A. L., Rabi, S. A., Siliciano, R. F. & Nowak, M. A. Antiretroviral dynamics determines hiv evolution and predicts therapy outcome. Nat. Med. 18(9), 1378–1385. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2892 (2012).

Rong, L., Feng, Z. & Perelson, A. S. Emergence of hiv-1 drug resistance during antiretroviral treatment. Bull. Math. Biol. 69(6), 2027–2060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11538-007-9203-3 (2007).

Callaway, D. S. & Perelson, A. S. Hiv-1 infection and low steady state viral loads. Bull. Math. Biol. 64(1), 29–64. https://doi.org/10.1006/bulm.2001.0266 (2002).

Rong, L. & Perelson, A. S. Modeling hiv persistence, the latent reservoir, and viral blips. J. Theor. Biol. 260(2), 308–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.06.011 (2009).

Coffin, J. M. Hiv population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science 267(5197), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7824947 (1995).

Pham, P. A. & Gallant, J. E. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of hiv infection. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2.3.459 (2006).

Fiebig, E. W. et al. Dynamics of hiv viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary hiv infection. AIDS 17(13), 1871–1879. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200309050-00005 (2003).

Pantaleo, G. et al. Hiv infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature 362(6418), 355–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/362355a0 (1993).

Adams, B. M. et al. Hiv dynamics: Modeling data analysis, and optimal treatment protocols. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 184(1), 10–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cam.2005.02.004 (2007).

Ribeiro, R. M. & Bonhoeffer, S. Production of resistant hiv mutants during antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97(14), 7681–7686. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.14.7681 (2008).

Komarova, N. L. & Wodarz, D. Drug resistance in cancer: principles of emergence and prevention. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102(27), 9714–9719. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0501870102 (2009).

Zhang, X. et al. Agent-based modeling of epidemics: Approaches, applications, and future directions. Technologies 13(7), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13070272 (2025).

Sun, R. & Bai, Z. The application of simulation methods during the covid-19 pandemic: A scoping review. J. Biomed. Inform. 148(7), 104543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104543 (2023).

Lukens, S. et al. A large-scale immuno-epidemiological simulation of influenza a epidemics. BMC Public Health 14, 1019. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1019 (2014).

De-Leon, D. & Aran, H. Mam: Flexible monte-carlo agent based model for modelling covid-19 spread. J. Biomed. Inform. 141, 104364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104364 (2023).

Hinch, W. et al. Openabm-covid19—an agent-based model for non-pharmaceutical interventions against covid-19 including contact tracing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009146. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009146 (2021).

Seresht, N. Enhancing resilience in construction against infectious diseases using stochastic multi-agent approach. Autom. Constr. 140, 104315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104315 (2022).

Jenness, S., Johnson, J., Hoover, K., Smith, D. & Delaney, K. Modeling an integrated hiv prevention and care continuum to achieve the ending the hiv epidemic goals. AIDS 34(14), 2103–2113. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002681 (2022).

Nosyk, B. et al. Ending the hiv epidemic in the USA: an economic modelling study in six cities. The Lancet HIV 7(7), e491–e503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30033-3 (2020).

Vermeer, W. et al. Agent-based model projections for reducing hiv infection among msm: Prevention and care pathways to end the hiv epidemic in chicago, illinois. PLoS ONE 17(10), e0274288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274288 (2022).

Cremin, I. et al. The new role of antiretrovirals in combination hiv prevention: a mathematical modelling analysis. AIDS 27(3), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ca2dd (2013).

Granich, R. M., Gilks, C. F., Dye, C., De Cock, K. M. & Williams, B. G. Universal voluntary hiv testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of hiv transmission: a mathematical model. The Lancet 373(9657), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9 (2009).

Eaton, J. W. et al. Hiv treatment as prevention: systematic comparison of mathematical models of the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on hiv incidence in south africa. PLoS Med. 9(7), e1001245. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001245 (2012).

Mansky, L. M. & Temin, H. M. Lower in vivo mutation rate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 than that predicted from the fidelity of purified reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 69(8), 5087–5094. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.69.8.5087-5094.1995 (1995).

Chun, T. W. et al. In vivo fate of hiv-1-infected t cells: quantitative analysis of the transition to stable latency. Nat. Med. 1(12), 1284–1290. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1295-1284 (1995).

CDC. Revised surveillance case definition for hiv infection—United States, 2014. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 63, 1–10 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E. Akinsumnade: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing Original Draft, Visualization. A. Azagbaekwue: Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing Review & Editing. F.G. Emunefe: Validation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing Review & Editing. O.B. Onuoha: Investigation, Resources, Writing Review & Editing. M. Raso: Supervision, Project administration, Writing Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinsunmade, A.E., Azagbaekwue, A., Emunefe, F.G. et al. HIV case management using agent-based modeling approach subject to antiretroviral therapy and lifestyle treatment plan. Sci Rep 16, 3605 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33537-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33537-y