Abstract

The staging of liver fibrosis is essential in influencing the final clinical management and treatment intervention that depends on proper and prompt diagnosis. The suggested multi-stream deep learning architecture that also involves the combination of EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 models may be regarded as a feature-level fusion solution that utilizes the most sophisticated normalization/regularization techniques. A full fusion model was also implemented, reaching a classification accuracy of 99.45% and a loss of 0.0295, which was higher than in any of the individual models (EfficientNetB0 with 98.50% and ResNet50 with 99.13%). In order to establish the robustness of the model, ablation analysis was carried out in detail, and it investigated the impact of an architectural element, including batch normalization, dropout layers, and fusion strategies. The results support the advantage of both normalization and dropout in terms of better generalization ability, but the feature fusion dramatically outperforms a simple concatenation in respect to discriminative ability. The findings reveal the strength of the multi-stream approach offered in the problem of homeless liver fibrosis stage classification, which means that it can be used in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver fibrosis is a pathological condition in the patient associated with the irreversible deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in the liver tissue. It is a serious intermediate phase in the pathogenesis of the chronic liver disease (CLD) and can lead to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) without proper diagnosis and treatment. The classical gold standard is liver biopsy and staging fibrosis, but this invasive method has risks and is limited in sampling and inter-observer. As a result, less invasive imaging processes, especially ultrasound elastography, have become safer methods of fibrosis measurement. Besides, the literature also emphasizes that the traditional pipelines, particularly pure ones, are time-consuming and expensive, which is why, to provide the necessary predictions precisely and efficiently, the computational models are required [1].Despite these developments, the subject of manual interpretation of ultrasound imaging has proved difficult and is usually influenced by low sensitivity at an early stage of fibrosis and high inter-observer difference [2, 3]. Medical imaging tasks have received increased focus to deal with the challenges with the help of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning techniques. The use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) has demonstrated state-of-the-art results in image classification, segmentation, and detection of diseases in most clinical applications [4, 5. However, it is also mentioned in the literature that ordinary deep convolutional networks can be restricted to capture contextual patterns across the world, which inspires the incorporation of non-CNN frameworks or multi-model fusion/ensuring to better reflect complicated patterns in medical images [6]. Moreover, more recent literature on medical image classification highlights that, despite the fact that deep learning has greatly enhanced the detection of anomalies and acquisition of features in medical images, end-to-end training in deep learning can be costly and time-intensive, which prompts the use of lightweight models that can be readily deployed into practice to serve the needs of clinical applications [7].Some CNN-based fibrosis classification methods used in liver imaging have used pretrained backbones including ResNet50, EfficientNetB0, DenseNet121, and VGG16. In [8], Park et al. achieved high accuracy to classify the stages of fibrosis on B-mode ultrasound with the fine-tuned ResNet50 model, whereas in [9] Paul and Govindaraj used a fine-tuned model called Efficient Net and attention mechanisms to focus better on attention and enhance interpretability. These works represent that analysis of liver diseases may be improved through transfer learning, yet they also underline such shortcomings as the need to have large annotated datasets and the impossibility to explain the outcomes. Regularly, current literature on AI-assisted diagnosis highlights how standard deep learning classifiers may be limited by the large quantity of annotated-data needed, and by the elevated cost of training which encourages studies into more data efficient training models which preserve good performance with lower annotation and training costs [10].In addition to the data and training efficiency, there is recent evidence that the learned representation of the diagnostic can be enriched to enhance performance. Specifically, ensemble-based deep-feature-driven classification on the input of fused deep features has been demonstrated to yield higher accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score than single classifiers and traditional ensemble baselines on medical image classification, which justifies the usefulness of deep-feature-driven ensemble learning [11]. Although the results are impressive, a great number of the existing approaches are based on one CNN backbone, which potentially limits the ability of the model to detect various spatial and textural featuresthat would identify the differences between closely related stages of fibrosis. Furthermore, black box characteristics of most CNNs may inhibit clinical trust particularly when predictions cannot be justified visually. Despite the extensive research on Grad-CAM to visualize class-discriminative regions, there has been little application of Grad-CAM to liver fibrosis diagnosis, especially in multi-branch or fusion models in which explainability needs additional research [12, 13]. Similarly, the recent research in AI-driven medical image diagnosis states that a single deep model can limit classification performance, whereas ensemble training on an ensemble of diverse feature embeddings between different representation learners and classification can perform better than their SOTA counterparts [6].In this regard, scholars have looked more into the study of hybrid structures and ensemble learning to increase feature diversity and model resilience. To illustrate, Zhang et al. in [14] made use of dual-stream CNN to classify liver steatosis and obtained better precision when features were fused. On the same note, Che et al. in [15] demonstrated that the generalizability of ultrasound-based liver disease detection can be enhanced by the inclusion of heterogeneous CNN features. Nevertheless, a noticeable gap in existing literature is the lack of explainable AI (XAI) integration to stage fibrosis. Grad-CAM and similar methods can enhance clinical trust in the detection of regions of fibrosis in ultrasound images. In [16], Brunese et al. have shown that interpretability and diagnostic reliability can be improved by using Grad-CAM-derived visual attention maps. However, the use of such explainability frameworks on CNN-based fusion models to classify fibrosis is very limited.Simultaneously, rather than using a single backbone, other works suggest taking deep convolutional features of the pretrained CNNs and inputting them to a collection of classical ML classifiers, performing better at the aggregate than that of a single model and incurring a lower training cost than traditional DL pipelines [7]. Moreover, recent hybrid architectures demonstrate that transformer self-attention (to model long-range dependencies), combined with convolutional blocks, can be used to learn better representations by learning local finer-grained features with global context and produce better results than single-paradigm models on benchmark tasks [1]. A new trend aims at reducing the cost of labeling, namely active learning: the model only consults experts on the most informative unlabeled samples; metaheuristic optimization can also be employed to optimize the sample selection, increasing accuracy with a reduced percentage of labeled data [10]. The recent ensemble models also state that by combining feature embedding of two or more trained deep models together using a structured fusion strategy, a single representation can be obtained thatretains spatial/contextual information but eliminates redundant features, thus improving further downstream classification accuracy [11].Based on such limitations and gaps in the research, the present study creates a fusion-based multi-branch approach based on the deep learning that entails strong CNN backbones called within a single multi-branch model. It is proposed that the suggested model can be trained and tested on images of liver ultrasound to predict fibrosis at five stages and enhanced with Grad-CAM to give a visual interpretation that can be understood clinically. In general, to facilitate the creation of AI-based liver fibrosis diagnostic tools, this methodology will enhance classification accuracy, strength, and transparency.

Proposed approach

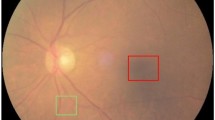

The proposed research presents a hybrid fusion model composed of two existing strong convolutional neural networks (CNNs), EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50, to classify liver fibrosis severity using ultrasound images as shown in Fig. 1. The architecture has the ability to use the ImageNet pretrained weights and has a feature-level fusion, which helps in increasing the discriminative power with computational effectiveness. It is also explained through explainability, where Grad-CAM is used to interpret the model in a clinical situation.

Overview of model architecture

The proposed fusion architecture has a dual-branch architecture that parallels working between EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 to extract deeper semantic features of the input ultrasound images. Both models will start with weights pretrained on ImageNet and do not include the top layers of both models, that is, the name “top classification layer.” Rather, just like in the case of CNNs, every network produces a feature map, which is then subjected to global average pooling. The concatenated pooled features will be taken as surmised information and passed on to a collection of fully connected layers to get a classification. In this fusion strategy, the benefits of compound scaling based on EfficientNetB0 and residual learning based on ResNet50 are complementary, and the former enriches the robustness of classification17,18.

To have a rigorous and reproducible training exercise, the proposed study involves a total of 6,223 liver ultrasound images in the five stages of fibrosis (F0-F4). Resizing to 224 × 224 pixels, image normalization in the range 0–1, and image conversion to RGB are done before model training to ensure consistency with the ImageNet-pretrained backbones. The dataset was divided according to an 80/20 stratified approach, with 80% of the dataset (4978 images) being used to train and validate the dataset, and only 20% (1245 images) to be used to test independently. The stratified split also provides proportional representation of minority classes (F1, F2, F3), which is required due to the inherent nature of the clinical imbalance of fibrosis staging data. There was no data spillage between institutions: the images of Seoul St. Mary hospital were used only in the context of training/validation, whereas images of Eunpyeong St. Mary hospital were used only as the external test set.

EfficientNetB0 feature extraction

EfficientNetB0 deploys a compound scaling method to balance depth, width, and input resolutions uniformly through fixed coefficients so the model can be highly accurate by using a much smaller number of parameters compared with conventional structures19. Its effectiveness and competitiveness were proven in several of the medical imaging tasks, such as diabetic retinopathy detection and chest X-ray classification20,21. Within our suggested pipeline, EfficientNetB0 starts with random weights but is initialized with ImageNet pretrained weights and is used as a light but powerful feature extractor (backbone), with the classification (top) layers removed. The resulting representations are given to a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer, which yields a compact one-dimensional feature vector (Eq. 1) where the pretrained weights are frozen to avoid overfitting and minimize computation cost. This shortened feature embedding reflects multi-scale structured motifs and small changes in texture, which are especially essential in discriminating fine-grained fibrosis stages on ultrasound images.

ResNet50 feature extraction

ResNet50 is a very deep CNN, such as 50 layers. And features the addition of skip connections to combat the vanishing gradient22. Its residual architecture allows deeper networks to be trained to work effectively, and so it has become a reliable choice in cases where high-order patterns of classification, as in staging liver fibrosis, must be accomplished. In this model, ResNet50 functions jointly with EfficientNetB0 and introduces its characteristic representations to the step of concatenation. With respect to the liver and pancreatic regions, it has been proved successful through the literature that the models developed on ResNet50 are very effective in the medical image scenario23,24.

The second branch of the model uses the ResNet50 residual learning network consisting of 50 layers and identity shortcuts to resolve the problem of the vanishing gradient. As is done with EfficientNetB0, the model is trained as a frozen feature extractor. The convolutional backbone used extracts effective spatial and edge-level features in the ultrasound scans. After extracting features, ResNet50 produces a feature vector whose outputs undergo a GAP layer to get a vector FRes. The focus of this vector on lower- and mid-level representations is complementary to the representations of EfficientNetB0.

The fusion classifier was created so as to balance regularization and expressive power. Following the process of obtaining feature embeddings of EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 by using Global Average Pooling, the two feature vectors were combined to obtain a single representation. Such a fused vector was then subjected to a batch normalization layer, then a fully connected layer with 512 units and ReLU activation to allow high-level interactions between the two branches. A dropout rate of 0.3 was used to minimize overfitting, and then a 128-unit dense layer with a second dropout stage was added. The last layer of classification was five softmax neurons that represented the fibrosis levels F0-F4.

Fusion and classification layers

After we obtain the global average pooled batch of our two branches, the vectors below it will be concatenated, and then dense types of layers will. This is then followed by a batch normalization layer, the 512-unit dense layer where the activation turns to ReLU, and the 128-unit dense layer, which will be regularized by dropping out at the end due to overfitting. Eventually, we feed the input into a liberating layer (softmax layer), which separates the stage of fibrosis into predetermined levels (F0-F4) by using five outdoor neurons. This late fusion model allows this model to collapse the fine and coarse computations of other CNN architectures and, in so doing, increase the general high classification accuracy25,26.

The essence of the suggested strategy is that we can combine the strengths of the pretrained models through feature-level fusion. The results of GAP layer FESE and FRes are summed up to have a shared feature vector Ffusion. This is then followed with two fully connected (FC) layers and dropout regularization to allow better generalization. The fusion pipeline permits memorizing complicated connections between abstract and spatial qualities in the model. The last layer of classification is the softmax of 5 neurons that provide predictions of fibrosis stages.

The Adam optimizer was used, with a learning rate of 1 × 10−4, which was selected due to preliminary tuning as the optimization configuration that performed best in terms of stable convergence. The model was trained up to 30 epochs, and the batch size was set to 64 under the influence of early stopping (patience = 5 epochs) to avoid overfitting. The loss function was sparse categorical cross-entropy, which is suitable when the classification has many classes and the labels are integers. Due to a large amount of class imbalance, especially F0 and F4 being overrepresented, the weights of the classes were calculated and utilized in the training process so that the model might focus equally on underrepresented fibrosis stages.

Training strategy and class balancing

Parameters of the model training are the Adam optimizer, the learning rate of 1e-4, and the sparse categorical cross-entropy loss function. Class weights are computed and used in training so as to deal with the imbalance in classes within the data. The overfitting is prevented by using early stopping, and the patience is at five epochs. The input images are unified in size and normalized; their size is set to 224 × 224. The training process is done with a batch size of 64 and a maximum of 30 epochs with an observation of validation accuracy. These tactics coincide with existing best practices in deep learning procedures27.

Model explainability with Grad-CAM

In order to increase the transparency of a model, the Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) is used, which allows visualizing discriminative areas that are operative and biased in a model. Namely, Grad-CAM is calculated on the last convolutional layer of the EfficientNetB0 branch. The approach creates a heatmap on the input image aimed at showing locations that are of diagnostic significance. In clinical practice, the use of visualization will be essential because it will allow radiologists to understand the rationality behind the AI-based system and develop trust in its results28,29.

Hyperparameter configuration and training settings

Table 1 shows the hyperparameters that were used to train the proposed dual-branch fusion model have been chosen based on initial tuning experiments as well as confirmed by an ablation study to ensure the best performance and generalization. Every ultrasound image was down sampled to the size of 224 × 224x3 to fit the input sizes of EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50, which were trained with ImageNet pretrained weights and frozen throughout training to maintain constant, low-level feature representations. The optimization of the model was done in the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1 × 10−4, and it was used together with sparse categorical cross-entropy as the loss function, giving a smooth convergence. Class weights were estimated to eliminate the existing class imbalance in the fibrosis data set and used in the training. The merged feature vector was channeled through a 512-unit dense layer and a 128-unit dense layer that is followed by ReLU activation, 0.3 dropout, and batch normalization in order to enhance regularization and reduce overfitting. Up to 30 epochs were trained, each using a batch size of 64, and early stopping (patience = 5) was used in maintaining the most optimal model. The last layer employed a five-class softmax classifier, which represents the stages of fibrosis F0-F4, and the data is divided into 80 percent training/validation and 20 percent testing to make sure that the performance is evaluated impartially.

Results and discussion

Dataset

The liver ultrasound (US) images dataset that were taken to classify liver fibrosis as a non-invasive alternative to the biopsy, as it relies on sound wave reflections without exposing harmful radiation. In contrast to superficial structures, liver image acquisition is sensitive to noise and signal attenuation owing to its deep anatomical location, but US is a popular and reasonably priced imaging modality used to image chronic liver disease. The training and validation data are patients in Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, whereas the test data are patients in Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital30. It entails five fibrosis stages (F0-F4), the class imbalance of which reflects the actual clinical rates: F0 (2114 images) and F4 (1698 images) are the majority, corresponding to no fibrosis and cirrhosis, respectively, whereas the intermediate stages (F1 (861), F2 (793), and F3 (857)) are underrepresented, as fewer patients have been diagnosed with early-stage fibrosis. The images are all in the JPG format; the dataset represents a realistic range of severity in fibrosis and hence is useful in the development of an automated deep learning-based liver fibrosis classification system. To train and evaluate, the dataset was subdivided into 80 percent of the training data and 20 percent of the test data to enable a strong validation of the models as well as accuracy in assessing performance. The model training and evaluation were done on a workstation with an NVIDIA Tesla T4 (16 GB VRAM) GPU, an Intel Xeon CPU, and 64 GB of RAM. TensorFlow 2.x and Python 3.10 were used to implement it.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the classes in the training set of liver fibrosis ultrasound data, each classified into five stages of fibrosis as F0, F1, F2, F3, and F4. The distribution is unbalanced, with the greatest number of samples being that of class F0 (no fibrosis), namely, about 1700 images, and the least being that of class F4 (cirrhosis), with around 1350 samples. The medium levels (F1, F2, and F3) contain fewer numbers of samples; F1 and F3 contain about 700 images, and F2 contains the lowest number of about 630 images. Such bias shows that the data is biased towards severe stages of fibrosis (F0 and F4). This makes sense, given the availability of clinical data with fibrosis stages. This imbalance can influence the performance of the model and may interfere with balancing the classes themselves or with the weight loss of the weights during training.

The test set of the liver fibrosis ultrasound dataset is shown in Fig. 3, and it is repeatedly partitioned into five extended annotations: F0, F1, F2, F3, and F4. Like the training set, it is also unbalanced, with class F0 No Fibrosis having the highest number of around 425 samples, followed by F4 Cirrhosis with around 340 samples. The intermediate features F1, F2, and F3 possess fewer samples; the number of images varies between 160 and 175. The test set has this distribution of class skew, reflecting the reality of actual frequencies of very high and very low stages of fibrosis (F0 and F4). This skew necessitates the necessity of adopting evaluation strategies that would accommodate skewed classes.

Results

Table 2 shows the classification ascendancy of a multi-class model of five classes (labels 0 to 4) using precision, recall, and F1-score measures. All the classes have an exceptionally high performance, with a precision recall close to or equal to 1.00, indicating that the model is good at predicting either the negatives or the positives of each of the classes with minimum errors. Class 0 and Class 4 were perfect (0.00), in the sense that both adequately captured the classes in all the remaining metrics. The precision, recall, and F1-scores are nearly one hundred percent on classes 1, 2, and 3, further supporting an equal performance of all categories. The model obtained a validation loss of 0.0295 and an overall average accuracy of 99.45%, suggesting a high level of generalization and robustness with very minimal prediction error. Such precision and a minimal loss reveal that the model has been performing excellently at the specified classification task.

Figure 4 shows that the Full Fusion Model has exemplary classification results on five liver fibrosis stages (classes 0 to 4), as the pattern along the diagonal is quite strong, so prediction accuracy is high. Class 0 (no fibrosis) was perfectly classified, with all 423 instances classified accurately. Class 1 had an accuracy of 170 / 172, and these were classified incorrectly in classes 2 and 4 but were minor errors. Likewise, Class 2 predicted 156 correctly out of 159 menu items, with 3 in Class 1. Class 3 made 170 correct predictions and only 1 erroneous one. Class 2 and Class 4 obtained 339 correct and 1 wrong prediction. The findings support the accuracy and stability of the Full Fusion Model to discriminate among the stages of fibrosis, which proves the efficiency of using EfficientNetB0, ResNet50, and VGG16 in a united structure to provide their fused results to enhance the liver fibrosis classification task.

Figure 5 illustrates the training and validation accuracy of one of the deep learning models in a span of 16 epochs. The left figure represents accuracy, in which the training accuracy and validation accuracy both rise steadily and begin at approximately 0.55 and reach nearly 1.0, representing good learning and generalization. The fast progress of the early epochs and then a plateau point to the convergence of the model. The right figure shows the loss curves, which show that both training and validation loss decline precipitously in the initial epochs and then flatten out near zero, indicating good progress toward optimal training and little overfitting. Overall, the plots reveal that the model attains high accuracy alongside low loss, which testifies to the model working well and being organized correctly.

Matters of the real labels of the actual fibrosis stage as well as the predicted ones made by the proposed model are shown in Fig. 6 as a set of sample ultrasound images of the liver. Both annotations (“Actual” and “Predicted”) on each picture are used: the former is the truth, i.e., belonging to the recording or the model, and the latter is the definition provided by the model. According to the outcomes, there is a substantial degree of concordance between the real and predicted classes of different fibrosis levels (F0-F4), showing that the model is highly able to adequately classify liver fibrosis. Only some minor discrepancies can be observed, which indicates that the model works very well, but there can be some tricky cases (e.g., due to visual similarity between two neighboring stages of fibrosis or noise in ultrasound images). One of the ways the robustness of the model was proven by this visualization is through the high classification accuracy that was reported.

Figure 7 shows liver ultrasound images, some of which the predicted stages of fibrosis differ from the actual labeled stages, thus indicating model misclassification. Each image is labeled with the classes (actual and predicted), with the error occurring in most of the cases between the adjacent stages (e.g., F1 was misclassified as F4 or F3 as F2), so it can be assumed that visual features are shared between some of the stages. These errors in classification show that although the model had great overall accuracy, it was struggling to differentiate between the adjacent stages, which can be attributed to the fact that these stages might not have much noticeable difference in their textures, as presented in ultrasound images. This visualization points out possible areas of improvement, which include the implementation of advanced feature extraction methods or the implementation of larger, more diverse data to be more robust.

Discussion

The results of the experimental model indicate that the developed EfficientNetB0-ResNet50 fusion architecture can achieve quite high-level results to classify liver fibrosis staging in ultrasound images, but there are several factors that can affect its further application in practice. To begin with, the model had a validation accuracy of 99.45, which can be limited regarding its ability to be generalized since training was done on data from one institution only; imaging settings, operator expertise, and device shape may vary in other hospitals. This makes the datasets biased, with that possibility being that the performance of the model would deteriorate when used in a heterogeneous real-world setting. Second, although fusion learning enhances feature richness, architecture is computationally expensive, and training and relatively computationally intensive inference tasks make it too costly to be useful in resource-constrained or point-of-care healthcare environments. Third, the model uses only the 2D ultrasound data; therefore, it does not reflect the temporal changes and the volumetric patterns that can be more indicative of the fibrosis progression. Finally, Grad-CAM visualizations make the system more interpretable but not entirely explainable, which is necessary to support the adoption of the systems in the clinical environment, and more rigorous explainability frameworks are needed. Taken altogether, these aspects highlight the importance of external validation between multicenter datasets, architectural design to ensure efficient deployment, and the integration of more comprehensive imaging modalities and powerful XAI models to enhance clinical preparedness and applications in practice.

Table 3 shows the comparative performance table gives a general idea of deep learning and CNN-based models that have been applied in previous liver lesion and fibrosis classification research and reveals large differences in the dataset size, number of classes, and diagnostic performance among the studies. The previous research, like Hwang et al.(2015) , worked with relatively small datasets and simple architectures (two-layer FFNN), with moderate accuracy levels of 84–91 and high sensitivity of classes that were easily distinguishable, like cysts, but very low sensitivity of malignancies. Future participants with CNNs and transfer learning, such as Reddy et al.(2018) and Yamakawa et al.(2019), also achieved better performance but still lower sensitivity on difficult categories (HCC 46–48%). The results of the larger dataset studies, such as Ryu et al.(2021), were balanced (ca. 90% accuracy) yet exhibited a class-dependent disparity, especially in the realm of HCC detection. Even the larger VGNet-based study by Nishida et al.(2022) had a significant specificity (96%), but with relatively low sensitivity (67.5%) to HCC, which suggested that the available data was not helping to identify the malignant ones. The suggested fusion model, however, which combines EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 and is trained on a significantly larger set of fibrosis images (n = 5628 images), led to the highest performance of all categories, and the highest sensitivity of each fibrosis stage is 98–100%, and the estimated specificity is approximately 99%, which is much better than all the proposed benchmark models. This overall class-independent enhancement is a clear sign that the proposed fusion architecture is able to extract fine-grained textual and global structural features, comparing with traditional CNNs, single-backbone networks, and previous liver lesion classification techniques.

Ablation study

To validate the architectural choices of our proposed fusion model, we conducted an extensive ablation study, evaluating the performance impact of removing or altering specific components. The configurations tested include single-branch variants using only EfficientNetB0 or ResNet50, versions without batch normalization or dropout layers, a simplified classifier without dense fusion layers, and a model relying solely on concatenation without further transformations.

Figure 8 shows trends of validation accuracy of several model configurations over 30 training epochs. Comparing are Full Fusion, EfficientNetB0 only, ResNet50 only, no Batch Norm, no Dropout, Simple Classifier, and Concat-only. The most accurate and fastest converging is the Full Fusion model, and after roughly 8 epochs it maintains near-perfect performance. EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 are not up to the mark though, and their accuracy is lower than that of the fusion model. Batch normalization and dropout can be found to accelerate the converging speed and increase the overall accuracy, which demonstrates the effectiveness of such regularization mechanisms. Simple Classifier and Concat-only models demonstrate the poorest results and cannot achieve at least 85% accuracy even at the last epoch. This benchmark shows that deployment of multiple feature extractors followed by proper normalization and regularization markedly improves the classification accuracy as well as training stability.

Figure 9 illustrates the comparison of model accuracy across different ablation settings, highlighting the impact of individual components on overall performance. The Full Fusion model achieves the highest accuracy at approximately 99.45%, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating multiple feature streams. In contrast, models using only individual networks, such as EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50, show slightly reduced accuracy, with values of 98.50% and 99.13%, respectively, indicating the benefit of feature fusion over standalone architectures. Removing essential components like Batch Normalization or Dropout further decreases accuracy, emphasizing their role in stabilizing and regularizing the learning process. The Simple Classifier configuration also performs slightly lower, suggesting that the chosen fusion and classifier architecture significantly contribute to performance optimization. The lowest accuracy is observed in Concat Only approach at 84.51%, underscoring that naive concatenation without proper fusion strategies leads to suboptimal results. Overall, the figure demonstrates that the proposed Full Fusion approach outperforms all ablated variants, validating the importance of the combined architectural choices.

Table 4 shows a detailed statistical comparison of the suggested fusion model with several architectural variations is given to assess the contribution of each of the components. The Full Fusion model recorded the most accuracy (99.45) and lowest loss (0.0295) with a small 95 percent confidence interval (0.9902–0.9971), proving to be very stable and reliable. Single-backbone models, e.g., EfficientNetB0-only and ResNet50-only, had somewhat less subtle accuracies, and the McNemar test indicates that EfficientNetB0-only and the full model do not differ significantly (p = 0.00003), whereas ResNet50-only and the full model do not differ significantly (p = 0.1842). Eliminating the main architectural components, including Batch Norm or Dropout, resulted in a significant decrease in performance, and both models exhibited statistically significant differences compared to the full model (p < 0.05). The simple classifier also did not perform so well as the fusion architecture, which confirms that there is a need for more profound non-linear transformations. The Concat Only was identified as the worst-performing configuration, having significantly lower accuracy (84.51%) and a very wide confidence interval, which means that fusion, when normalization and dense layers are not done, is not enough. On the whole, the statistical test proves that the high-level fusion, normalization, and regularization are necessary preconditions of the high level of the proposed model performance and generalization.

Conclusion

This paper introduced a new combination-based deep learning architecture, which combines the relative advantage of EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 along with the goal of generating the liver fibrosis stage with a high degree of accuracy using the ultrasound image. The experimental findings showed that the proposed fusion architecture was significantly better than all the individual backbone models and architecture versions, with an impressive accuracy of 99.45% and a very low validation loss value. The ablation experiment also confirmed the critical importance of feature-level fusion, batch normalization, and dropout regularization to improve stability and discriminative ability. Overall, the results highlight the efficiency of multi-stream fusion approaches to the problem of complex medical image classification, especially in the situations when subtle changes in texture should be detected at various stages of a disease.

In spite of the good performance, there are a few limitations that one should recognize. To begin with, the model has been trained and tested on the data obtained in a particular clinical setting and ultrasound system, which might not be generalized to other institutions, ultrasound equipment, and positions of acquisition. Patient variations, differences in image quality, operator technique, and variation in characteristics of the image may create a shift in the distribution that may affect real-world robustness. Second, the fusion architecture, though correct, is computationally expensive and in practice not usable in low-resource clinical devices or even on mobile diagnostic systems until the model is optimized. Also, only 2D ultrasound images were used in the current work; no additional data were also taken into consideration: no temporal dynamics, elastography inputs, or multimodal imaging information, which may have given stronger diagnostic information, were considered. Lastly, even though the number of images is significant, the dataset is still a small clinical group, which can obstruct the capacity of the model to identify rare or marginal fibrosis patterns.

To strengthen the clinical usefulness and generalizability of the proposed method in the future, one should mitigate these limitations in the course of future work. The assessment of model robustness should be carefully examined by extending it to multi-center and multi-device data to ensure the measurement is rigorous and accurate under different imaging conditions. The inclusion of other modalities, shear-wave elastography or contrast-enhanced ultrasound, can be added to enhance the strength of feature representation and increase diagnostic accuracy. A 3D or sequential model of exploring temporal or volumetric data may be useful in gaining a more detailed understanding of the progression of fibrosis. In addition, such model compression methods as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation would allow using it in resource-restricted settings. Finally, incorporating the more explainable AI (XAI) tools like SHAP or LIME instead of Grad-CAM would contribute to more transparent decision-making and the development of confidence in clinicians.

Data availability

Dataset available on: [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vibhingupta028/liver-histopathology-fibrosis-ultrasound-images/data].

References

Ai, H., Huang, Y., Tai, D.-I., Tsui, P.-H. & Zhou, Z. Ultrasonic assessment of liver fibrosis using one-dimensional convolutional neural networks based on frequency spectra of radiofrequency signals with deep learning segmentation of liver regions in B-mode images: A feasibility study. Sensors 24, 5513. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24175513 (2024).

Sandrin, L. et al. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis by vibration-controlled transient elastography (Fibroscan). IntechOpen https://doi.org/10.5772/20729 (2011).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 42, 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Anaya-Isaza, A., Mera-Jiménez, L. & Zequera-Diaz, M. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging. Inform. Med. Unlocked 26, 100723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2021.100723 (2021).

Park, H. C. et al. Automated classification of liver fibrosis stages using ultrasound imaging. BMC Med. Imaging 24, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-024-01209-4 (2024).

Paul, G. & Govindaraj, R. Experimental analysis for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in ultrasound images based on efficient net classifier. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES), Chennai, India 1–7 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSES.2023.00001.

Tulsani, V., Sahatiya, P., Parmar, J. & Parmar, J. XAI applications in medical imaging: A survey of methods and challenges. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 11, 181–186. https://doi.org/10.17762/ijritcc.v11i9.8332 (2023).

Savaş, S. Explainable artificial intelligence for diagnosis and staging of liver cirrhosis using stacked ensemble and multi-task learning. Diagnostics 15, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15091177 (2025).

Zhang, C., Wang, L., Wei, G., Kong, Z. & Qiu, M. A dual-branch and dual attention transformer and CNN hybrid network for ultrasound image segmentation. Front. Physiol. 15, 1432987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1432987 (2024).

Che, H., Brown, L. G., Foran, D. J., Nosher, J. L. & Hacihaliloglu, I. Liver disease classification from ultrasound using multi-scale CNN. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 16, 1537–1548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-021-02414-0 (2021).

Brunese, M. C. et al. Explainable and robust deep learning for liver segmentation through U-net network. Diagnostics 15, 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15070878 (2025).

Hirata, S. et al. Convolutional neural network classification of ultrasound images by liver fibrosis stages based on echo-envelope statistics. Front. Phys. 11, 1164622. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1164622 (2023).

Dong, X. et al. Ultrasound image-based contrastive fusion non-invasive liver fibrosis staging algorithm. Abdom. Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-025-04991-z (2025).

Tan, M & Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. arXiv (2019), arXiv:1905.11946. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1905.11946.

Arora, L. et al. Ensemble deep learning and EfficientNet for accurate diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 14, 30554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81132-4 (2024).

Alici-Karaca, D. et al. A New lightweight convolutional neural network for radiation-induced liver disease classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 73, 103463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103463 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016) https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

Tangruangkiat, S. et al. Diagnosis of focal liver lesions from ultrasound images using a pretrained residual neural network. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 25, e14210. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.14210 (2024).

Yin, Y. et al. Liver fibrosis staging by deep learning: a visual-based explanation of diagnostic decisions of the model. Eur. Radiol. 31, 9620–9627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08005-0 (2021).

Elazab, N. et al. Histopathological-based brain tumor grading using 2D–3D multi-modal CNN-transformer combined with stacking classifiers. Sci. Rep. 15, 27764. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11754-9 (2025).

Bharati, S., Podder, P. & Mondal, M. R. H. Hybrid deep learning for detecting lung diseases from X-ray images. Inform. Med. Unlocked 20, 100391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2020.100391 (2020).

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 6, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0197-0 (2019).

Selvaraju, R.R., Cogswell, M., Das, A., Vedantam, R., Parikh, D. & Batra, D. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proc. of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 618–626 (Venice, Italy, 2017) https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.74.

Mahmud, M. A. A. et al. Explainable deep learning approaches for high precision early melanoma detection using dermoscopic images. Sci. Rep. 15, 24533. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09938-4 (2025).

Joo, Y. et al. Classification of liver fibrosis from heterogeneous ultrasound image. IEEE Access 11, 9920–9930. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.XXXXXXX (2023).

Hwang, Y. N., Lee, J. H., Kim, G. Y., Jiang, Y. Y. & Kim, S. M. Classification of focal liver lesions on ultrasound images by extracting hybrid textural features and using an artificial neural network. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 26(s1), S1599–S1611 (2015).

Reddy, D. S., Bharath, R. & Rajalakshmi, P. A novel computeraided diagnosis framework using deep learning for classification of fatty liver disease in ultrasound imaging. In 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on e-health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom) 1–5 (Ostrava, Czech Republic 2018) https://doi.org/10.1109/HealthCom.2018.8531118

Yamakawa, M., Shiina, T., Nishida N. & Kudo, M. Computer aided diagnosis system developed for ultrasound diagnosis of liver lesions using deep learning. In 2019 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS) 2330–2333 (Glasgow, UK) https://doi.org/10.1109/ULTSYM.2019.8925698

Ryu, H. et al. Joint segmentation and classification of hepatic lesions in ultrasound images using deep learning. Eur. Radiol. 31, 8733–8742 (2021).

Nishida, N. et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) models for the ultrasonographic diagnosis of liver tumors and comparison of diagnostic accuracies between AI and human experts. J. Gastroenterol. 57(4), 309–321 (2022).

Tangruangkiat, S. et al. Diagnosis of focal liver lesions from ultrasound images using a pretrained residual neural network. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 25(1), e14210. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.14210 (2024) (PMID: 37991141; PMCID: PMC10795428).

Reddy DS, Bharath R, Rajalakshmi P, eds. A novel computeraided diagnosis framework using deep learning for classification of fatty liver disease in ultrasound imaging. IEEE 20th international conference on e-health networking,applications and services (Healthcom),Ostrava,Czech Republic 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/HealthCom.2018.8531118 (2018).

Yamakawa M, Shiina T,Nishida N, Kudo M, eds. Computer aided diagnosis system developed for ultrasound diagnosis of liver lesions using deep learning. IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Glasgow, UK 2330–2333. https://doi.org/10.1109/ ULTSYM.2019.892569 (2019).

Ryu H, Shin SY, Lee JY, Lee KM, H-j Kang, Yi J. Joint segmentation and classification of hepatic lesions in ultrasound images using deep learning. Eur Radiol. 31:8733–8742 (2021).

35. Nishida N, Yamakawa M, Shiina T, et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) models for the ultrasonographic diagnosis of liver tumors and comparison of diagnostic accuracies between AI and human experts. J Gastroenterol. 57(4):309–321 (2022).

Tangruangkiat S, Chaiwongkot N, Pamarapa C, Rawangwong T, Khunnarong A, Chainarong C, Sathapanawanthana P, Hiranrat P, Keerativittayayut R, Sungkarat W, Phonlakrai M. Diagnosis of focal liver lesions from ultrasound images using a pretrained residual neural network. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 25(1), e14210. Epub 2023 Nov 22. PMID: 37991141; PMCID: PMC10795428 https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.14210 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University for funding this research work.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. (DGSSR-2025-02-01045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M., M.K.E. and H.H.; Methodology, H.H., M.A.M.; Software, M.A.M. and M.K.E.; Validation, H.H.; Resources, M.A.M., and M.K.E.; Data curation, M.A.M., and H.H.; Formal analysis, M.A.M., and H.H.; Investigation, M.A.M.; Project administration, H.H.; Supervision, H.H.; Visualization, M.A.M., and M.K.E.; Writing—original draft, M.A.M, and M.K.E.; Writing—review & editing, M.A.M. and H.H. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alshammari, H.H., Mahmood, M.A. & Elbashir, M.K. Explainable fusion of EfficientNetB0 and ResNet50 for liver fibrosis staging in ultrasound imaging. Sci Rep 16, 3536 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33544-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33544-z