Abstract

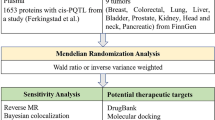

Lung cancer (LC) is among the most prevalent cancers globally, posing a significant threat to human health. This study employed Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to identify key drug targets for LC treatment. MR results from the inverse variance weighted (IVW) algorithm highlighted 352 expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) and 31 protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs) causally associated with LC. Sensitivity and Steiger analyses confirmed that 305 eQTLs and 28 pQTLs exhibited a robust causal relationship with LC. Colocalization analysis further identified 20 eQTLs as potential drug targets for LC. Predictions were made for 257 drugs and 17 diseases, establishing a target-drug network that included PTGFR-D005557 and IREB2-C004925, among others. The drugs-diseases network revealed associations such as D007213 with Liver Cirrhosis and D013749 with Schizophrenia. Notably, the strongest binding interaction was observed between Valproic acid and eight genes (BRAT1, H2BC11, IREB2, MICAL1, MPHOSPH6, PTGFR, RHNO1, SERPING1), suggesting a significant molecular interaction. Ultimately, seven key drug targets (SERPING1, TDRD9, GBAP1, FAM241A, ZKSCAN4, ZKSCAN3, Z94721.1) were consistently identified across two MR studies and validated. These targets offer new avenues for LC treatment, highlighting their potential in therapeutic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC), the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally1, is categorized into small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with NSCLC being the more prevalent type. While smoking is the primary risk factor, non-smokers may also develop LC due to genetic predisposition, air pollution, or occupational exposure2. Symptoms of LC vary, but typically include persistent cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, shortness of breath, hoarseness, weight loss, and fatigue3. Early symptoms are often subtle, leading to high diagnostic costs, with most LC cases diagnosed at advanced stages4,5. Despite improvements in treatment modalities such as surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies, the five-year survival rate remains low (15–20%)1,6. Targeted therapy has become the primary treatment for advanced LC, but challenges remain, including inefficacy in the absence of driver mutations and frequent acquired resistance7. Consequently, identifying new therapeutic targets for LC continues to be a critical area of research.

Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), primarily single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), are genomic variants that regulate gene expression and can be classified as cis-eQTLs or trans-eQTLs, depending on their proximity to the target genes8,9. Similarly, protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs) map genetic variants that influence protein levels, with cis-pQTLs located near coding regions10. eQTLs analysis involves assessing SNP-gene expression correlations and physical distance, with databases like the eQTL Gen Phase II providing transcriptomic insights for complex traits derived from blood11. While numerous large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified SNPs associated with LC risk, most studies focus on eQTLs or pQTLs in isolation, with limited integration of multi-omics approaches. Moreover, many of these SNPs reside in non-coding regions or gene intervals, resulting in GWAS data that offer limited insights into pathogenic genes and drug targets. Therefore, this study aims to provide further theoretical support for identifying drug targets in LC.

Traditional observational studies are often hindered by confounding bias and reverse causality in causal inference. Mendelian randomization (MR) addresses these limitations by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to estimate causal effects between exposures and outcomes, provided that key assumptions (relevance, independence, exclusion restriction) are met12,13. Gene expression levels are influenced by eQTLs, with cis-eQTLs commonly recognized as regulatory factors affecting gene expression in drug target MR analysis. The robustness of MR against unmeasured confounding has established it as a crucial method for identifying causal biomarkers and therapeutic targets across various complex diseases, including bipolar disorder, inflammatory bowel disease, coronary heart disease, sepsis, and aortic aneurysms14,15,16,17,18. In drug target MR studies, cis-eQTLs act as genetic proxies for gene expression modulation9. Recent MR analyses also assess potential side effects of drug targets and their adverse reactions. Notably, MR analysis of LC is gaining traction, with studies demonstrating potential causal relationships between specific gut microbiota and SCLC, as well as genetic predictors of schizophrenia and LC19,20. However, comprehensive genomic evidence supporting druggable targets for LC remains lacking.

This study identified causal drug targets for LC through MR analyses integrating multi-omics data. Additionally, co-localization analysis was performed to prioritize therapeutic candidates and validate their clinical potential.

Materials and methods

Data extraction

Data for LC, plasma genes, and plasma proteins were obtained from the publicly available Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) Open GWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) on December 21, 2023. The LC dataset included two GWAS IDs: ieu-a-987 (used as the training set), comprising 85,449 samples (29,863 LC and 55,586 controls) with a total of 10,439,018 SNPs, and ieu-a-966 (used as the testing set), comprising 27,209 samples (11,348 LC and 15,861 controls) with 8,945,893 SNPs. Additionally, the eQTL dataset included 19,942 genes, and the pQTL dataset included 3622 plasma proteins derived from 3301 healthy samples from the Open GWAS database, as well as 1531 plasma proteins from the literature21,22. In this study, the eQTL and pQTL of plasma were collectively referred to as epQTL. Furthermore, this study adhered to the STROBE-MR checklist.

Data pre-processing for MR study

In this MR analysis, epQTLs were treated as exposure factors, and LC was regarded as the outcome. The three main assumptions of classical MR analysis were satisfied: (i) the independence assumption (IVs are not associated with any confounders); (ii) the association assumption (IVs directly affect exposure); and (iii) the exclusivity assumption (IVs affect the outcome solely through the exposure and not via other pathways). To identify and screen IVs, the following steps were performed. First, the exposure factors were screened for IVs (p < 5 × 10–8) using the ‘extract instruments’ function from the “TwoSampleMR” R package (version 0.5.6)23. This stringent p-value threshold ensures that only highly significant genetic variants are selected as potential IVs, minimizing the risk of weak or spurious associations. Simultaneously, SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) were removed (r2 = 0.001, kb = 10,000), eliminating redundant genetic variants that are highly correlated and reducing multicollinearity, thus improving the independence of the selected IVs. Next, the strength of each IV was assessed using F-statistics (F > 10), which ensures that the IVs are sufficiently strong, reducing the potential for weak instrument bias and enhancing the reliability of causal inference. F-statistics were calculated using the formula:

where “se” indicates the standard error. Subsequently, SNPs associated with the outcome were removed, and effect alleles and effect sizes were harmonized. After eliminating duplicates, the remaining SNPs were used for the subsequent MR analysis.

MR study

In the MR analysis, five algorithms were employed using the ‘mr’ function: Inverse variance weighted (IVW)24, MR Egger25, Weighted median26, Simple mode27, and Weighted mode26. Among these, IVW was regarded as the most crucial method. The weighting formula for IVW was calculated as follows:

For the ith IV, \({\upbeta }_{{\text{i}}}\) represents the effect estimate of the IV on the exposure, \({\upgamma }_{{\text{i}}}\) indicates the effect estimate of the IV on the outcome, and se denotes the standard error. Missing values were handled based on their quantity: if missing values were minimal, observations with missing data were excluded using the na.omit function; otherwise, multiple imputation via the mice package was employed to address larger amounts of missing data.

The inclusion criteria for MR results were PIVW < 0.05 and a minimum of three SNPs (SNP ≥ 3). The odds ratio (OR) quantifies the likelihood of one event relative to another. An OR greater than 1 suggests an increased likelihood of the event due to the risk factor, while an OR less than 1 indicates a protective effect. Scatter plots were generated to assess the correlation between SNPs of the exposure and the outcome, and forest plots were created to illustrate the diagnostic impact of exposure on the outcome. A funnel plot was also constructed to evaluate the symmetry of causal effects, aiding in the detection of publication bias, assessment of small-study effects, and ensuring the overall reliability of the results.

A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the MR results. Heterogeneity was tested using the mr_heterogeneity function28 based on Cochran’s Q test. When P > 0.05, the fixed IVW method was applied; if P < 0.05, the random IVW method was used. Additionally, the MR-Egger method from the “TwoSampleMR” R package (version 0.5.6) was employed to test for horizontal pleiotropy, with a P-value greater than 0.05 indicating the absence of horizontal pleiotropy. The MR-PRESSO method from the “MRPRESSO” R package (version 1.0)29 was also used to identify potential confounders. A P-value greater than 0.05 suggested no confounding factors. Furthermore, a leave-one-out (LOO) analysis was performed using the mr_leaveoneout function30.

Steiger analysis

To establish the causal relationship, the Steiger analysis was applied using “TwoSampleMR,” with the criteria for passing the Steiger test being a correct causal direction (value = 1) and a Steiger test adjusted P-value < 0.05.

Colocalization analysis

To identify potential drug targets for LC, epQTL-GWAS colocalization analysis was performed using the “coloc” R package (version 5.2.2)31. Four hypotheses were tested in the colocalization analysis: Hypothesis 0 (H0) indicating no association with GWAS and epQTL, Hypotheses 1 and 2 (H1/H2) indicating association with either GWAS or epQTL, Hypothesis 3 (H3) indicating that both GWAS and epQTL are associated but with distinct causal variants, and Hypothesis 4 (H4) indicating shared causal variants for both traits. Posterior probabilities (PPs) were calculated for each hypothesis. A PP greater than 0.6 for H4 suggests that colocalization analysis is valid, indicating that these epQTLs could serve as potential drug targets for LC.

Drug and disease predicted, molecular docking analysis

Based on the identified drug targets, the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, http://ctdbase.org) was utilized to predict potential drugs and associated diseases. Subsequently, target-drug and drug-disease networks were constructed and visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.10.1)32.

To investigate the interaction between the targets and drugs, drugs with the highest degree values from the target-drug network were selected for molecular docking analysis. Protein crystal structures of the targets (acting as receptors) were sourced from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/), while the 3D molecular structures of the selected drugs (acting as ligands) were obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Molecular docking was conducted using AutoDock Vina (https://vina.scripps.edu/), and the binding energies were calculated. A binding energy below -5.0 kcal/mol typically suggests a strong affinity between the molecules for effective binding.

Phenotypic scanning

To further investigate the potential side effects of interventions that reduce LC risk by targeting the identified drug targets, an agnostic phenome-wide MR (PheW-MR) analysis was performed. This analysis used the same cis-epQTL, with genetic instruments for disease traits selected from the IEU Open GWAS database.

Validation analysis

The same MR analysis methods were applied to validate the results, using the identified potential drug targets as exposure factors and LC (GWAS ID: ieu-a-966) as the outcome. The methodology and procedures for this analysis align with Sects. "Data pre-processing for MR study" and "MR study" of this study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.2.2), with differences analyzed via the Wilcoxon test (P < 0.05). The overall study design is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results

383 epQTLs had a causal relationship with LC

After screening, 5,522 epQTLs (340 eQTLs and 5,182 pQTLs) were retained as exposure factors for further analysis. The univariate MR analysis revealed a causal relationship between 383 epQTLs (352 eQTLs and 31 pQTLs) and LC using the IVW method (p < 0.05). Among these, 199 risk factors were identified, including GBP6 (OR = 1.072, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.002–1.147, p = 0.043) and GPD1L (OR = 1.073, 95% CI = 1.011–1.138, p = 0.020), and 184 protective factors were identified, such as FAM3D (OR = 0.942, 95% CI = 0.917–0.968, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1).The scatter plot corroborated these findings, with FAM3D showing a negative slope and BCL2L13 showing a positive slope, indicating that FAM3D is a protective factor, while BCL2L13 is a risk factor (Fig. 2a). Forest plot analysis further supported these results, with the MR effect size for BCL2L13 greater than 0, while the effect size for FAM3D was less than 0 in the IVW method (Fig. 2b). The funnel plot (Fig. 2c) demonstrated that IVs were symmetrically distributed around the IVW line, consistent with Mendel’s second law. Additionally, heterogeneity testing revealed a P-value for exposure factors greater than 0.05, indicating no heterogeneity in the MR study (Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). The MR-Egger method also showed no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (p > 0.05). In the MR-PRESSO analysis, 130 eQTLs and 28 pQTLs were missing (NA), while the remaining 222 eQTLs and 3 pQTLs showed no evidence of confounding factors (p > 0.05) (Table 2, Supplementary Table 3). The LOO analysis indicated no significant aberrations, supporting the reliability of the MR results (Fig. 2d). Ultimately, 383 epQTLs were confirmed to have a causal relationship with LC in our MR study.

MR analyses of the causal effect of epQTL on LC. (a) Scatter plots for MR analyses of the causal effect of epQTL on LC; (b) forest map for MR analyses of the causal effect of epQTL on LC; (c) funnel plot for MR analyses of the causal effect of epQTL on LC; (d) leave-one-out for MR analyses of the causal effect of epQTL on LC.

Steiger analysis confirmed the causality of 333 epQTL to LC was real and effective

To determine the precise causal relationship between 383 epQTLs and LC, a Steiger analysis was performed, with LC as the exposure and epQTL as the outcome. A total of 333 epQTLs (305 eQTLs and 28 pQTLs) passed the Steiger test, confirming that the causality between epQTLs and LC was valid and not influenced by reverse causality (Table 3, Supplementary Table 4).

The potential drug targets were identified using colocalization analysis

Colocalization analysis identified 20 epQTLs (20 eQTLs and 0 pQTLs) that passed the test, including B3GNT5 (PP.H4 = 0.671), BRAT1 (PP.H4 = 0.738), and COPS3 (PP.H4 = 0.996) (Table 4). These were considered potential drug targets. As shown in Fig. 3, BRAT1 exhibited a strong association with LC, with the rs13243437 locus linking BRAT1 to LC and supporting a causal relationship.

The targets-drugs and drugs-diseases networks might be helpful for treating LC

From the 20 drug targets identified through colocalization, 257 drugs were predicted. A target-drug network was constructed, consisting of 275 nodes (18 targets and 257 drugs) and 692 edges, including PTGFR-D005557, IREB2-C004925, and others (Fig. 4a). Additionally, 17 diseases were predicted based on the targeted drugs, including liver cirrhosis, epilepsy, and schizophrenia. A drug-disease network was created, comprising 139 nodes (17 diseases and 122 drugs) and 643 edges, with examples such as D007213-Liver Cirrhosis and D013749-Schizophrenia (Fig. 4b).

The target-drug and drug-disease networks. (a) Target-drug network, comprising 275 nodes (18 targets and 257 drugs) and 692 edges, where the red circles represent drug targets and the blue diamonds represent drugs; (b) Drug-disease network, comprising 139 nodes (17 diseases and 122 drugs) and 643 edges, with red circles representing drug targets and blue diamonds representing drugs. The line thickness indicates the confidence between drug targets and diseases, with thicker lines signifying higher confidence.

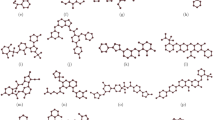

Valproic acid might be helpful for treating LC

In the target-drug network, valproic acid and bisphenol A exhibited the highest degree values. However, due to potential health risks associated with bisphenol A, including its weak estrogenic effects that may interfere with the human endocrine system and its lack of medicinal properties33, valproic acid was selected for molecular docking analysis. Among the 18 targets, protein structures were available for only 8 genes (BRAT1, H2BC11, IREB2, MICAL1, MPHOSPH6, PTGFR, RHNO1, and SERPING1), so molecular docking was conducted for these 8 genes. The results revealed favorable binding energies between valproic acid and all 8 genes, with the following binding energies: valproic acid and BRAT1 at − 4.9 kcal/mol (Fig. 5a), valproic acid and H2BC11 at − 5.3 kcal/mol (Fig. 5b), valproic acid and IREB2 at − 5.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 5c), valproic acid and MICAL1 at − 4.8 kcal/mol (Fig. 5d), valproic acid and MPHOSPH6 at − 4.2 kcal/mol (Fig. 5e), valproic acid and PTGFR at − 5.2 kcal/mol (Fig. 5f), valproic acid and RHNO1 at − 6.2 kcal/mol (Fig. 5g), and valproic acid and SERPING1 at − 4.9 kcal/mol (Fig. 5h).

Some potential side effects might occur in LC patients

A search of the GWAS IDs for 17 diseases revealed 6 diseases with relevant studies, including liver cirrhosis, endometriosis, and schizophrenia. These 6 diseases corresponded to 20 epQTLs, requiring 120 phenotypic scans. Seven results were visualized, such as the phenotype scan showing that GBAP1 had a causal relationship with influenza (OR = 1.130, p = 0.006), identifying GBAP1 as a risk factor (Fig. 6). However, the MR study demonstrated a causal relationship between GBAP1 and LC, with GBAP1 acting as a protective factor (OR = 0.908, p = 0.08). This suggests that, in the treatment of LC, potential side effects may arise if the patient also has influenza.

A total of 7 key drug targets passed validation

To further validate the 20 drug targets identified in the previous studies, a validation analysis was conducted. Seven key drug targets (SERPING1, TDRD9, GBAP1, FAM241A, ZKSCAN4, ZKSCAN3, Z94721.1) were significantly associated across two MR studies, with one outcome GWAS ID being ieu-a-987 and the other being ieu-a-966. These 7 drug targets were thus classified as key drug targets (Fig. 7).

Discussion

LC remains a significant threat to human health, with current treatment methods facing limitations such as restricted efficacy, substantial adverse reactions, and varying degrees of drug resistance, highlighting the urgent need for new therapeutic targets and strategies7. MR has emerged as a powerful tool, with numerous studies utilizing genetic variation as IVs to infer causality between potential drug targets and disease outcomes34,35. The integration of MR with genetic and proteomic data offers a novel approach to identifying promising targets for LC treatment.

This study conducted a large-scale MR analysis incorporating LC along with plasma gene and protein data obtained from the IEU Open GWAS database. Multiple MR analyses provided strong evidence of an association between 20 predicted eQTLs and LC. These 20 eQTLs, including B3GNT5, BRAT1, COPS3, FAM241A, and GBAP1, are proposed as potential drug targets for LC. Additionally, the CTD database was employed for drug and disease prediction, followed by molecular docking to validate the pharmaceutical potential of the identified targets. To assess potential side effects associated with candidate drug targets, phenotype scanning was performed, revealing 7 key drug targets (SERPING1, TDRD9, GBAP1, FAM241A, ZKSCAN4, ZKSCAN3, Z94721.1) that showed significant overlap. For instance, GBAP1, identified as a potential drug target, exhibited a causal relationship with influenza (p < 0.05) and was classified as a risk factor. However, MR analysis indicated that GBAP1 is protective for LC, suggesting that potential side effects may arise if LC patients with GBAP1 as a target also have influenza.

SERPING1 (C1-inhibitor, C1INH), a member of the serine protease inhibitor family G1, encodes a highly glycosylated plasma protein involved in complement activation, contact, coagulation, and fibrinolysis systems36. Prior studies have demonstrated the strong anti-inflammatory functions of SERPING1 both in vivo and in vitro. While SERPING1 is vital for various physiological processes, its deficiency is well-documented in hereditary angioedema (HAE)37. Numerous studies have also linked SERPING1 to cancer. It has been associated with lymph node and bone metastasis in breast cancer38,39,40, and a decrease in SERPING1 mRNA levels correlates with lower survival rates and increased malignancy in prostate cancer40. Furthermore, SERPING1 has been implicated in the diagnosis and prognosis of liver cancer, ovarian cancer, colon cancer, glioma, and other cancers41,42,43,44,45. Two studies specifically on LC indicated that SERPING1 is underexpressed in LC and serves as an independent prognostic predictor in NSCLC46,47, which aligns with our research findings.

GBAP1, a glucosylceramidase (GBA) pseudogene 1, exhibits 96% homology with the GBA sequence and is located 16 kb downstream of the functional gene48,49. Despite limited available data on GBAP1, reported studies have explored its role in Parkinson’s disease, liver cancer, and gastric cancer50,51. Additionally, GBAP1 acts as a protective factor in gastric cancer, while exhibiting pro-oncogenic functions in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), positioning it as a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target52,53. In influenza-related studies, only GBA—not GBAP1—has been investigated in relation to the influenza virus54. Interestingly, in LC patients, influenza virus infection has been linked to increased disease progression55. A population-based study revealed that regional influenza-like illness (ILI) activity is associated with higher mortality rates in NSCLC patients53. Furthermore, published research indicates that after recovery from influenza A virus (IAV) infection, the lungs can develop long-lasting antitumor immunity56. However, no research has yet explored the role of GBAP1 in LC and influenza. This study fills this gap by providing reliable evidence for the potential involvement of GBAP1 in this context.

Tudor domain-containing protein 9 (TDRD9), an RNA helicase with a TUDOR domain, is primarily expressed in the germline and participates in the biosynthesis of PIWI-interacting RNAs57,58. Most existing research on TDRD9 has focused on male infertility, with fewer studies examining its role in other fields. Notably, a study on the involvement of TDRD9 in LC found that TDRD9 is significantly upregulated in NSCLC and its derived cell lines due to the low methylation of CpG islands. Additionally, the expression of TDRD9 has been associated with poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma59. Our findings corroborate a causal relationship between TDRD9 and LC, this contrasts with previous research and warrants further investigation through mechanistic studies.

ZKSCAN3 (zinc-finger with KRAB and SCAN domains 3), a member of the zinc-finger transcription factor family, is widely expressed in human tissues and plays a role in regulating various physiological processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, and tumor transformation60. Numerous studies suggest that ZKSCAN3 inhibits the expression of autophagy lysosomal mediators in certain cancer cells, thus impeding cancer progression and positioning it as a potential therapeutic target61,62,63. A GWAS and subsequent large-scale follow-up identified ZKSCAN3 as a novel locus influencing lung function, which may also be linked to other complex traits and diseases64. Ouyang et al. found that ZKSCAN3 contributes to the response to severe lung infections, including susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections following immunosuppression65. While previous studies have reported associations between ZKSCAN3 and various cancers and diseases, its role in LC has not been explored. Our study provides the first evidence that ZKSCAN3 could serve as a therapeutic target for LC, further advancing research on this gene.

ZKSCAN4 (Zinc-finger with KRAB and SCAN domains 4), also known as ZNF307, belongs to the same family as ZKSCAN3. It is expressed in various tissues, including the kidneys, mouth, skin, lungs, brain, spleen, and liver66. In HEK-293 cells, ZKSCAN4 inhibits the transcriptional activity of p53 and p21 and interacts with glucocorticoid receptors66,67. In liver cancer, ZKSCAN4 has been shown to act as a tumor suppressor68. In recent years, studies on ZKSCAN4 have been limited to its role in post-traumatic stress disorder, gastrointestinal disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis with metabolic syndrome69,70,71. However, its role in LC remains largely unexplored, and our research addresses this gap.

The gene FAM241A has been shown to play a tumor-suppressive role in human LC through the ANXA2P1/miR-20b-5p/FAM241A axis, offering significant diagnostic and prognostic value72. As for Z94721.1, little is known about this gene, with only two studies suggesting its potential as a tumor prognostic marker in esophageal and ovarian cancers73,74.

The strength of this study lies in its use of MR methods, providing a robust framework to assess causal relationships and mitigating the limitations of observational studies. Moreover, the 20 potential drug targets for LC treatment were corroborated through colocalization analysis, enhancing the reliability of the findings and minimizing the risk of false positives. The CTD database was utilized for drug and disease prediction, followed by molecular docking and phenotype scanning of the predicted diseases, which yielded 7 positive results, thus adding depth and credibility to our MR study. This research highlights genes that could serve as drug targets to enhance the efficacy, safety, and success rate of drug development for LC, addressing the limitations of large-scale randomized clinical trials. Seven drug targets related to LC were identified in our population-based study, some of which have already been partially supported by existing research45,46,59,72. These findings offer valuable insights for future drug development. Additionally, our analysis of drug and disease prediction helps identify potential safety concerns, which is crucial if these targets are to be used in clinical settings.

This study has several limitations. First, it predominantly focused on European populations, necessitating further validation in diverse ethnic groups to assess the broader applicability of the findings. Second, the lack of stratification in the GWAS data based on specific LC subtypes limits the ability to conduct detailed subgroup analyses. Third, while blood-derived eQTL/pQTL data reflect systemic physiological and pathological changes, they are less capable of capturing lung tissue-specific gene and protein expression profiles. Thus, exclusive reliance on blood-based epigenetic QTLs may not fully capture the pathogenesis of pulmonary diseases or their therapeutic potential. Moreover, the phenotype-associated genomic loci identified in this study are likely involved in the early stages of lung carcinogenesis, yet their role in disease progression remains unclear. Due to the observational nature of the study, it is not possible to directly validate the interventional effects of targeting these loci on established LC. Future research should include multi-ethnic cohorts to assess the generalizability of the findings across diverse populations and incorporate molecular subtype-based stratification analyses. Additionally, integrating lung tissue and single-cell multi-omics data is essential to address the limitations of blood-derived data in reflecting lung-specific biological processes. Finally, preclinical studies, including in vitro cell models and in vivo animal experiments, are critical. Using genetically engineered models and animal survival analyses, these studies should aim to definitively establish the functional roles of these QTLs in LC development, assessing their feasibility as therapeutic or preventive targets.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study employed comprehensive MR methods to establish a causal relationship between 333 epQTLs and LC, identifying 20 potential drug targets for LC treatment through colocalization analysis. Notably, 7 of these drug targets were successfully validated and can be considered key targets for LC therapy. These robust findings could pave the way for new strategies in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of LC. However, as the study primarily involves bioinformatics analyses, further in vivo and in vitro research is required to validate these drug targets and prioritize their development for LC therapy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available in the [Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) Open GWAS] repository at [https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/].

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820 (2024).

Neal, R. D., Sun, F., Emery, J. D. & Callister, M. E. Lung cancer. BMJ 365, l1725. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1725 (2019).

Beer, D. G. et al. Gene-expression profiles predict survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Nat. Med. 8, 816–824. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm733 (2002).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 511, 543–550 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13385

Lee, E. & Kazerooni, E. A. Lung cancer screening. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 43, 839–850. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1757885 (2022).

Lovly, C. M. Expanding horizons for treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2050–2051. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2203330 (2022).

Lancet, T. Lung cancer: Some progress, but still a lot more to do. Lancet 394, 1880. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32795-3 (2019).

Hernandez, D. G. et al. Integration of GWAS SNPs and tissue specific expression profiling reveal discrete eQTLs for human traits in blood and brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 47, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.020 (2012).

Zhu, Z. et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet. 48, 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3538 (2016).

Pietzner, M. et al. Mapping the proteo-genomic convergence of human diseases. Science 374, eabj1541. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj1541 (2021).

Vosa, U. et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 1300–1310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00913-z (2021).

Smith, G. D. & Ebrahim, S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?. Int. J. Epidemiol. 32, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg070 (2003).

Hingorani, A. & Humphries, S. Nature’s randomised trials. Lancet 366, 1906–1908. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67767-7 (2005).

Zheng, J. et al. Phenome-wide Mendelian randomization mapping the influence of the plasma proteome on complex diseases. Nat. Genet. 52, 1122–1131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-0682-6 (2020).

Jia, T. et al. Uncovering novel drug targets for bipolar disorder: A Mendelian randomization analysis of brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and plasma proteomes. Psychol. Med. 54, 2996–3006. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724001077 (2024).

Zhu, S., Lin, Y. & Ding, Z. Exploring inflammatory bowel disease therapy targets through druggability genes: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 15, 1352712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1352712 (2024).

Sun, Z. et al. Comprehensive mendelian randomization analysis of plasma proteomics to identify new therapeutic targets for the treatment of coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction. J. Transl. Med. 22, 404. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05178-8 (2024).

Xia, R., Sun, M., Yin, J., Zhang, X. & Li, J. Using Mendelian randomization provides genetic insights into potential targets for sepsis treatment. Sci. Rep. 14, 8467. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58457-1 (2024).

Yang, W., Fan, X., Li, W. & Chen, Y. Causal influence of gut microbiota on small cell lung cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Clin. Respir. J. 18, e13764. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.13764 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Genetic prediction of the causal relationship between schizophrenia and tumors: A Mendelian randomized study. Front. Oncol. 14, 1321445. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1321445 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. Genomic atlas of the proteome from brain, CSF and plasma prioritizes proteins implicated in neurological disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1302–1312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00886-6 (2021).

Shadbolt, T., Sainsbury, A. W., Foster, J. & Bernhard, T. Risks from poorly planned conservation translocations. Vet. Rec. 188, 269. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.373 (2021).

Zhou, H. et al. Education and lung cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48, 743–750. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz121 (2019).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 37, 658–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21758 (2013).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv080 (2015).

Hartwig, F. P., Davey Smith, G. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1985–1998. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx102 (2017).

Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 7, e34408. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.34408 (2018).

Lu, L., Wan, B., Li, L. & Sun, M. Hypothyroidism has a protective causal association with hepatocellular carcinoma: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 987401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.987401 (2022).

Yang, M. et al. No evidence of a genetic causal relationship between ankylosing spondylitis and gut microbiota: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients 15, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15041057 (2023).

Jin, T. et al. Causal association between systemic lupus erythematosus and the risk of dementia: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 13, 1063110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1063110 (2022).

Rasooly, D., Peloso, G. M. & Giambartolomei, C. Bayesian genetic colocalization test of two traits using coloc. Curr. Protoc. 2, e627. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.627 (2022).

Doncheva, N. T., Morris, J. H., Gorodkin, J. & Jensen, L. J. Cytoscape StringApp: Network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J. Proteome Res. 18, 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00702 (2019).

Abraham, A. & Chakraborty, P. A review on sources and health impacts of bisphenol A. Rev. Environ. Health 35, 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2019-0034 (2020).

Song, W. et al. Systematic druggable genome-wide Mendelian randomization identifies therapeutic targets for lung cancer. BMC Cancer 24, 680. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12449-6 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Proteome-wide multicenter mendelian randomization analysis to identify novel therapeutic targets for lung cancer. Arch. Bronconeumol. 60, 553–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2024.05.007 (2024).

Drouet, C. et al. SERPING1 variants and C1-INH biological function: A close relationship With C1-INH-HAE. Front .Allergy 3, 835503. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2022.835503 (2022).

Karnaukhova, E. C1-inhibitor: Structure, functional diversity and therapeutic development. Curr. Med. Chem. 29, 467–488. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867328666210804085636 (2022).

Popeda, M. et al. Reduced expression of innate immunity-related genes in lymph node metastases of luminal breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 11, 5097. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84568-0 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Identification of hub genes for early detection of bone metastasis in breast cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1018639. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1018639 (2022).

Peng, S. et al. Decreased expression of serine protease inhibitor family G1 (SERPING1) in prostate cancer can help distinguish high-risk prostate cancer and predicts malignant progression. Urol. Oncol. 36, 366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.05.021 (2018).

Ji, Q. et al. Characteristic proteins in the plasma of postoperative colorectal and liver cancer patients with Yin deficiency of liver-kidney syndrome. Oncotarget 8, 103223–103235. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.21735 (2017).

Poersch, A. et al. A proteomic signature of ovarian cancer tumor fluid identified by highthroughput and verified by targeted proteomics. J. Proteomics 145, 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2016.05.005 (2016).

Liu, J., Lan, Y., Tian, G. & Yang, J. A systematic framework for identifying prognostic genes in the tumor microenvironment of colon cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 899156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.899156 (2022).

Quan, Q., Xiong, X., Wu, S. & Yu, M. Identification of autophagy-related prognostic signature and analysis of immune cell infiltration in low-grade gliomas. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 7918693. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7918693 (2021).

Furuya, H. et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 (PAI-2) overexpression supports bladder cancer development in PAI-1 knockout mice in N-butyl-N- (4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine- induced bladder cancer mouse model. J. Transl. Med. 18, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02239-6 (2020).

O-charoenrat, P. et al. Casein kinase II alpha subunit and C1-inhibitor are independent predictors of outcome in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 10, 5792–5803. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0317 (2004).

Huang, N., Hu, C. & Liu, Z. Drug targets for lung cancer: A multi-omics Mendelian randomization study. Asian J. Surg. S1015–9584, 01373–01373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.07.019 (2024).

Horowitz, M. et al. The human glucocerebrosidase gene and pseudogene: Structure and evolution. Genomics 4, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/0888-7543(89)90319-4 (1989).

Imai, K. et al. A novel transcript from a pseudogene for human glucocerebrosidase in non-Gaucher disease cells. Gene 136, 365–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1119(93)90497-q (1993).

Straniero, L. et al. The GBAP1 pseudogene acts as a ceRNA for the glucocerebrosidase gene GBA by sponging miR-22-3p. Sci. Rep. 7, 12702. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12973-5 (2017).

Song, M. et al. Large-scale analyses identify a cluster of novel long noncoding RNAs as potential competitive endogenous RNAs in progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging 11, 10422–10453. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102468 (2019).

Duan, X. et al. GBAP1 polymorphisms (rs140081212, rs1057941 and rs2990220) contribute to reduced risk of gastric cancer. Future Oncol. 18, 1861–1872. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2021-0973 (2022).

Kinslow, C. J. et al. Influenza activity and regional mortality for non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 13, 21674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47173-x (2023).

Drews, K. et al. Glucosylceramidase maintains influenza virus infection by regulating endocytosis. J. Virol. 93, e00017-00019. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00017-19 (2019).

Angrini, M. et al. To vaccinate or not: Influenza virus and lung cancer progression. Trends in cancer 7, 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2021.02.006 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Influenza-trained mucosal-resident alveolar macrophages confer long-term antitumor immunity in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 24, 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01428-x (2023).

Aravin, A. A. et al. Cytoplasmic compartmentalization of the fetal piRNA pathway in mice. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000764. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000764 (2009).

Shoji, M. et al. The TDRD9-MIWI2 complex is essential for piRNA-mediated retrotransposon silencing in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell 17, 775–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.012 (2009).

Guijo, M., Ceballos-Chavez, M., Gomez-Marin, E., Basurto-Cayuela, L. & Reyes, J. C. Expression of TDRD9 in a subset of lung carcinomas by CpG island hypomethylation protects from DNA damage. Oncotarget 9, 9618–9631. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22709 (2018).

Chauhan, S. et al. ZKSCAN3 is a master transcriptional repressor of autophagy. Mol. Cell 50, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.024 (2013).

Li, S. et al. Transcriptional regulation of autophagy-lysosomal function in BRAF-driven melanoma progression and chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 1693. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09634-8 (2019).

Chi, Y. et al. ZKSCAN3 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503, 2583–2589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.019 (2018).

Kawahara, T. et al. ZKSCAN3 promotes bladder cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Oncotarget 7, 53599–53610. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.10679 (2016).

Soler Artigas, M. et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat. Genet. 43, 1082–1090. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.941 (2011).

Ouyang, X. et al. ZKSCAN3 in severe bacterial lung infection and sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 101, 1467–1474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-021-00660-z (2021).

Ecker, K. et al. A RAS recruitment screen identifies ZKSCAN4 as a glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 42, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1677/JME-08-0087 (2009).

Li, J. et al. ZNF307, a novel zinc finger gene suppresses p53 and p21 pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363, 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.180 (2007).

Liang, Y. et al. Zinc finger protein 307 functions as a tumor-suppressor and inhibits cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 38, 2229–2236. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2017.5868 (2017).

Zhou, S. et al. Investigating the shared genetic architecture of post-traumatic stress disorder and gastrointestinal tract disorders: A genome-wide cross-trait analysis. Psychol. Med. 53, 7627–7635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723001423 (2023).

Zhu, H. et al. Gene-based genome-wide association analysis in European and Asian populations identified novel genes for rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE 11, e0167212. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167212 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Identification of immune-associated genes in diagnosing osteoarthritis with metabolic syndrome by integrated bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 14, 1134412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1134412 (2023).

Sweef, O., Yang, C. & Wang, Z. The oncogenic and tumor suppressive long non-coding RNA-microRNA-messenger RNA regulatory axes identified by analyzing multiple platform omics data from Cr(VI)-transformed cells and their implications in lung cancer. Biomedicines 10, 2334. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10102334 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Construction of a novel necroptosis-related lncRNA signature for prognosis prediction in esophageal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 22, 345. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02421-8 (2022).

Zhu, L. et al. Derivation and validation of a necroptosis-related lncRNA signature in patients with ovarian cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 6228846. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6228846 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all contributors who have played a pivotal role in bringing this research to fruition

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Research Project of Wannan Medical College (WK2024ZQNZ01), the Anhui Provincial Department of Education University Research Project (2023AH051765), the Quality Engineering Project of Wannan Medical College (2024hhkc01), the Anhui Provincial Quality Engineering Project for Higher Education Institutions (2024xsxx060) and the Innovation project of the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China (MAI2023C012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and M.G.; Methodology, Y.H., M.G. and M.Z.; Software, Y.H. and M.Z.; Validation, Y.H., M.G. and M.Z.; Formal Analysis, Y.H. and M.G.; Inves-tigation, Y.H.; Resources, Y.H. and M.Z.; Data Curation, Y.H., M.G. and M.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.H., M.G. and M.Z.; Writing—Review & Editing, Y.H. and M.G.; Visualization, Y.H.; Supervision, Y.H.; Project Administration, Y.H. and M.G.; Funding Acquisition, Y.H., M.G. and M.Z. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study exclusively used publicly available data, which was approved by the ethical reviews of the studies cited in the Methods section.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Geng, M. & Zhang, M. Unveiling novel potential drug targets for lung cancer through Mendelian randomization analysis. Sci Rep 16, 3559 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33574-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33574-7