Abstract

Identifying stable-resistant sources offers an eco-friendly and sustainable insect management strategy. Sixty-eight wild pigeonpea accessions were systematically screened against three predominant bruchid species (Callosobruchus analis, C. chinensis, C. maculatus) using a high-throughput screening pipeline at Kanpur, India, from 2021 to 2024. Resistance classification was based on seed damage and susceptibility index. Four Rhyncosia bracteata accessions consistently exhibited convergent and complete resistance across species, while few C. scarabaeoides accessions were resistant to C. chinensis and C. maculatus but moderately stable against C. analis. Multivariate analyses revealed significant species- and condition-driven variation, with seed damage, emergence and developmental period, as key discriminators. Correlation funnel confirmed antibiosis as the predominant resistance mechanism, while antixenosis was species-specific, particularly against C. maculatus. Machine learning model predicted seed and insect traits as major contributors. Factorial Analysis of Mixed D and hierarchical clustering validated biologically meaningful grouping of resistant versus susceptible accessions, with biochemical traits enhancing separation of intermediate classes. Collectively, R. bracteata emerges as a robust multi-species resistance donor, and C. scarabaeoides as a species-specific donor. These multi-species resistant resources act as invaluable resources for introgression breeding to develop bruchid-resistant pigeonpea cultivars and highlight opportunities to dissect biochemical pathways and QTLs underlying resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bruchids, also known as, pulse or seed beetles, are major pests of legume crops worldwide. They attack matured or dried grains both in the field and during storage, often causing substantial economic losses, especially in stored grains1. Bruchids are cosmopolitan in distribution, with over 1700 species described worldwide across 62 genera. Among these, the predominant genera include Callosobruchus, Bruchus, Bruchidius, and Acanthoscelides2,3. In India, over 100 species under 11 genera are documented, with Callosobruchus being most significant4. Among them, Callosobruchus maculatus (F.), C. analis (F.), and C. chinensis L. are widespread causing extensive damage to stored pulses5.

Pulses are vital crops for the livelihoods of tropical and subtropical nations including India, which is both largest producer (~ 25 MT, 25% of global production) and the largest consumer. Despite recent progress toward self-sufficiency, imports remain substantial at 4.7 MT in 2023–246. Government initiatives have targeted productivity gains, especially in pigeonpea, black gram, and lentils, but policy efforts alone cannot meet domestic demand; multidimensional research is also essential to reduce both field and post-harvest losses. Current post-harvest losses in pulses are estimated at 5.65–8.41% (nearly USD 1 billion), with storage losses contributing ~ 2%, largely due to insect damage7,8. Pigeonpea is particularly vulnerable, with storage losses of 1.54–1.9%. Bruchids alone can cause 4–60% grain damage, sometimes reaching total loss under unmanaged infestations3,9. NITI Aayog6 projects pulse production to reach 30 MT by 2030 and 45.79 MT by 2050; at ~ 2% storage loss, this equals 0.6–1 MT or more of annual grain loss by 2050. Thus, strengthening post-harvest protection, especially against bruchids, is crucial for safe pulse storage and for ensuring national food and nutritional security.

Traditional and modern approaches for managing bruchids remain inconsistently effective3. In India, only one contact insecticide (deltamethrin) and two fumigants (phosphine, EDCT) are available, and their overuse has led to resistance, residues, and health and environmental risks10. Reports of rising phosphine resistance11 underscore the need for effective, practical, and sustainable alternative strategies.

Identification and utilization of genetic sources of resistance in grain legumes through host plant resistance (HPR) remains one of the most reliable and sustainable strategies for bruchid management. HPR relies on plant traits that adversely affect insect development, survival, and biological fitness, thereby reducing grain damage12,13. Because bruchids are oligophagous, the discovery of diverse resistance mechanisms is particularly valuable for developing durable resistant cultivars while broadening the genetic variability. Achieving this requires systematic exploration of wild relatives across multiple gene pools related to the target crop.

In pigeonpea, numerous wild accessions have been collected, characterized, and conserved in Indian institutes such as ICRISAT, NBPGR, and IIPR, and these resources have been widely explored for resistance to major biotic (pod borers, wilt, SMD) and abiotic (draught, salinity) stresses14,15,16,17,18. Further, the utilization of wild Cajanus species has facilitated the introgression of productivity-enhancing and stress-resistance traits into cultivated pigeonpea. Through modern genomics and pre-breeding approaches, these wild alleles are helping broaden the crop’s genetic base, thereby improving yield stability and resilience under challenging environments19,20,21. Although few studies22,23,24 have identified bruchid-resistant donors in certain wild and cultivated Cajanus species against C. maculatus and/or C. chinensis from India, these findings were based on single- screening condition and a single resistance scoring criterion. Moreover, none of these species were evaluated against C. analis–a often-overlooked yet equally prevalent and more destructive species5,25,26. This gap limits the broader applicability of the previously identified resistant donors for comprehensive bruchid management.

Considering these limitations, this study aimed to identify and validate stable bruchid-resistance donors from diverse wild pigeonpea germplasms against all three major bruchid species infesting stored pulses across India5,25,26. Unlike earlier studies; a high-throughput protocol integrating multiple screening conditions and resistance scoring criteria over three consecutive years enabled systematic and comprehensive evaluation of the germplasm panel. The study also examined host-insect trait interactions to identify key predictors of resistance. Importantly, the study reports stable, multi-species, convergent resistance donors in wild pigeonpea accessions with strong potential for deployment in introgression breeding to develop bruchid-resistant cultivars.

Material and methods

Location of the study, plant and insect materials

The study was conducted between 2021 and 2024 at the Storage Entomology Laboratory, Division of Crop Protection, ICAR-Indian Institute of Pulses Research (IIPR), Kanpur, India. Sixty-eight diverse wild pigeonpea accessions were evaluated for bruchid resistance. These accessions, maintained in wild garden and genebank, were originally collected from different agro-ecological regions and national repositories (NBPGR & ICRISAT) including IIPR.. Seeds were screened against three major bruchid species5- Callosobruchus chinensis, C. analis, and C. maculatus. Species identity was confirmed using standard morphological keys and molecular characterization25. Pure cultures of the three species were maintained under controlled conditions (28 ± 1 °C, 70 ± 2% RH, and 12 h photoperiod), with uniform-aged populations obtained through continuous subculturing on sterilized mungbean seeds.

Screening of accessions against bruchid species

Screening was conducted following high-throughput multiple screening protocols25,27. All 68 accessions were initially evaluated under free-choice (FC) screening condition, followed by no-choice (NC) to impose maximum pressure on seeds and assess resistance under contrasting conditions. Twenty-three accessions that exhibited varied resistance reactions against the three species in these two screenings were further validated in confirmatory no-choice (CNC) screening.

The FC tests were conducted in modified screening chambers with each accession replicated three times using30 seeds per replicate25,27.The NC and CNC tests were conducted in plastic vials (4 × 5 cm, W × H). , enabling rigorous validation of resistance responses. Each vial contained 30 seeds per accession, with three replicates per accession.

Across all assays, freshly emerged 3–4-day-old adults were used at three pairs per replicate (one pair per ten seeds). Sexes were distinguished using antennal and pygidium morphology. Adults were removed after 72 h of exposure, initial seed infestation was recorded, and samples were incubated under standard conditions used for culturing. Post-emergence observations began once F1 adults emerged in any replicate.

Data collection and statistical analyses

Seed morphological traits

Seed morphological traits were recorded for all 68 accessions prior to initiating bruchid infestation, as these traits contribute to antixenosis and influence oviposition preference.. Both quantitative and qualitative traits were recorded using 10 seeds per accession with three replications. Test weight (x100sw) was recorded by measuring the weight (g) of 100 seeds. Seed length (sl) and width (sw) were measured with a vernier caliper and expressed in millimeters. Seed surface area (ssa) was derived from length and width using the formula of McCabe et al.28 and expressed in mm2. Qualitative traits including seed texture (st), seed coat color (scc), seed coat pattern (sccp), seed shape (ss), and seed hilum (sh), were recorded using a hand lens and stereo-zoom trinocular microscope following ICAR-NBPGR descriptors29.

Seed biochemical traits

Biochemical traits were quantified from seeds of 16 accessions that consistently exhibited resistance responses across species and screening conditions, along with a susceptible check (ICP15630, G23). This was done to understand the role of seed antibiosis, and three replications were used for each accession. The biochemical estimations were performed at ICRISAT, Hyderabad.

Protein content (prot) was determined by Lowry’s method30,31 using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (FCR). A standard curve was prepared using bovine serum albumin (BSA), and absorbance was measured at 660 nm andexpressed as mg protein per g seed sample. The tannin content (tan) using the Vanillin–Hydrochloride method, which relieson the reaction of phenolic compounds with vanillin under acidic conditions to form a red-colored complex measurable at 500 nm and expressed as mg tannin per gram of sample32. Total phenolic content (phen) in the sample was estimated using the Folin–Ciocalteu method, wherein the FCR is reduced by phenolic compounds under alkaline conditions to generate blue-colored complex measurable at 650 nm33. A catechol-based standard curve was used, and values were expressed as catechol equivalents (mg/g sample). Total soluble sugars (cho) were quantified using the Anthrone method32, in whichcarbohydrates are dehydrated by concentrated sulfuric acid to form furfural derivatives, which react with anthrone to produce a blue-green chromogen measurable at 630 nm. A glucose standard curve was used, and results were expressed as mg g⁻1 seed sample. Flavonoids (flav) were estimated by the vanillin–sulfuric acid method34, where phloroglucinol-type compounds react with vanillin in the presence of concentrated sulfuric acid to form a red complex measured at 500 nm. Results were expressed as absorbance values (A₅₀₀).

Insect traits

Insect infestation traits were recorded during pre-incubation and post-emergence phases. Pre-incubation observations included oviposition (op) and egg density (ed). Post-emergence traits included seed damage (gd), adult density (ad), number of males (m), and number of females (f). Adult emergence was monitored daily for 30 days after first emergence and the mean developmental period (mdp) was calculated with this data using Howe’s formula35. Oviposition and seed damage were expressed as percentages, while egg, adult, and sex counts were recorded per 30-seed sample. Adult survivability (as) percentage was estimated as per Seram et al.36.

Categorization of resistance reactions

Resistance reactions by accessions were categorized using two established criteria: susceptibility index (SI; rflag_si) and seed damage (SD, rflag_sd). SI was calculated from adult survivability and mean developmental period35,37. Accessions were categorized as resistant (R, SI < 0.05), moderately resistant (MR, 0.051–0.060), moderately susceptible (MS, 0.061–0.070), susceptible (S, 0.071–0.080), and highly susceptible (HS, > 0.081). The seed damage scale directly categorized accessions as highly resistant (HR, 0% damage), resistant (R, 1–9%), moderately susceptible (MS, 10–69%), and highly susceptible (HS, 70–100%)35.

Statistical analyses

Data from insect, seed morphological and biochemical traits were analyzed using multiple statistical approaches to understand trait interactions across accessions, screening conditions, and species. Data were first tested for normality and suitability prior to analysis wherever necessary. The detailed statistical analyses adopted for this are as follows:

-

a.

Descriptive statistics and boxplots Descriptive statistics, including ANOVA was done ascertain the variability of different traits between accessions. These were worked out for insect, seed morphological and biochemical traits using the TraitStats package38. Boxplots were prepared with ggplot239.

-

b.

MANOVA, Univariate analyses, Correlation funnel and Random Forest: Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was employed to examine whether insect traits varied significantly across screening conditions (FC vs. NC) within each species and between species (when pooled across conditions). Wilks’ Lambda was used as the test statistic to evaluate multivariate effects of species or condition. When MANOVA indicated significant differences, univariate ANOVA was applied on individual traits to identify the specific contributors of observed variation. Analyses were carried out in R using the base ‘stats’ package for MANOVA and ANOVA and visualization through ggplot2 and gridExtra40. Separate MANOVAs were run within each species (FC vs. NC) and across species (FC and NC pooled), with significance tested at α = 0.05.

To investigate role of each trait on the observed bruchid resistance, the correlationfunnel package version 0.2.0 in R was employed41. Two resistance criterion-based flags (‘rflag_sd’ for SD and ‘rflag_si’ for SI) were used as outcome variables representing resistant categories of accessions. The method binarizes numeric and categorical variables and qantifies their correlation with a binary target, thereby ranking the strength traits-resistance associations. Funnels were constructed separately for each of the three bruchid species, and for both SD- and SI-based resistance classifications, enabling rapid exploratory identification of key insect and seed morphological traits linked with resistance or susceptibility.

The identification of key traits strongly associated with resistance was further validated using Random Forest (RF). RF was selected because it is particularly effective for high-dimensional biological datasets, offering the ability to model complex nonlinear interactions while minimizing risks of overfitting. In this study, RF classification was applied to predict bruchid-resistance traits in wild pigeonpea using two independent indicators: resistance categories based on seed damage (rflag_sd) and susceptibility index (rflag_si). Two datasets were analyzed: (i) insect and seed morphological traits across 68 germplasms, and (ii) insect, seed morphological and biochemical traits across 17 germplasms. Resistance categories were binarized by grouping “HR” and “R” as Resistant and “MS”, “S”, and “HS” as Susceptible, while “MR” accessions excluded to avoid ambiguity. Models were implemented in R using the caret package42 for training and resampling, and randomForest for classification43. Repeated five-fold cross-validation was used for the 68-accession dataset, while leave-one-out cross-validation was employed for the smaller 17-accession dataset. Data preprocessing, reshaping, and visualization were performed using the tidyverse suite44. For each classification model, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and performance metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity) and compiled into a single summary table (Table 6). All intermediate outputs (confusion matrices, ROC plots, partial dependence plots, and variable importance rankings) are provided in the supplementary files (Supplementary files 3–5) forreproducibility.

-

c.

Grouping of accessions through FAMD and Clustering Since the study recorded both qualitative and quantitative data, the Factorial Analysis of Mixed Data (FAMD) was used to jointly analyse quantitative insect and seed traits through PCA and qualitative resistance categories through MCA, thereby providing a unified ordination framework. Analyses were conducted in R using FactoMineR45 and factoextra46, with plots refined using ggplot239. Two levels of analysis were performed: (i) all 68 germplasms per species, using insect traits data from FC and NC conditions, and (ii) a subset of 17 germplasms, incorporating insect traits from FC, NC, and CNC conditions along with biochemical traits. In both analyses, accessions were grouped by resistance categories (HR, R, MR, MS, S, HS), and 95% confidence ellipses were plotted to visualize within-group variance.

To further explore variability and grouping pattern among pigeonpea germplasms, hierarchical clustering was performed using both insect and seed morphological traits, and subsequently incorporating biochemical traits. For each bruchid species, datasets from FC and NC tests were combined by averaging trait values per germplasm. Morphological traits were merged by germplasm identity, and in a second analysis, biochemical traits were integrated for the 17 germplasms. All quantitative traits were standardized (Z-score) to eliminate scale effects. Hierarchical clustering was done based on Euclidean distances and Ward’s minimum variance in R with pheatmap 1.0.13 package47. For each species, two heatmaps were generated: (i) insects + morphological data of 68 germplasms, and (ii) insects + morphological + biochemical data of 17 germplasms. Dendrograms were cut into four clusters, enabling identification of germplasm groups with similar insect response patterns and evaluation of whether morphological or biochemical traits improved resistance discrimination.

-

d.

Role of antibiosis in accessions’ resistance against bruchid species Correlation analyses were prformed between insects and seed biochemical traits recorded for 17 germplasms under FC, NC, & CNC conditions to ascertain the influence of seed antibiosis on insect development. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were computed using Hmisc package in R48 with adjusted p-values, and heatmaps (ggplot239) were generated for each bruchid species, combining all three screening conditions into a single correlation matrix, with significance levels indicated by stars (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

-

e.

Influence of accessions’ resistance levels on sex ratio of bruchid species This analysis tested whether sex ratio (male/(male + female)) varied across germplasm resistance classifications (SD- and SI- based) using male and female data from two FC and NC conditions for each species. Sex ratio values < 0.5 indicated female-biased emergence, while > 0.5 indicated male-biased emergence.

Analyses followed a three-tier approach. First, exploratory visualization was performed using ggplot239, generating boxplots of sex ratio distributions per resistance class, faceted by species (CA, CC, CM) and screening condition (FC, NC). Second, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) were fitted using lme449 and lmerTest50, with sex ratio as the response, resistance flags × condition × species as fixed effects, and germplasm as random intercept. Since sex ratio is a proportion, LMMs were used tather than arcsine transformation, which is unsuitable for ecological proportion data51. Post-hoc Tukey comparisons were obtained using emmeans52, and model fit was evaluated using DHARMa53. Third, validation analyses were conducted with classical ANOVA with Tukey HSD. Given that sex ratio is a proportion, beta-regression models (betareg54) and beta-family GLMMs (glmmTMB55) were fitted as alternatives, particularly for data with many zero/one values.

Results and discussion

Germplasm details

The study utilized 68 wild pigeonpea accessions belonging to two genera: Cajanus (49 accessions) and Rhynchosia (19 accessions). The genera Cajanus represented by five species, including C. scarabaeoides (30 accessions), C. platycarpus (9), C. crassus (6), C. cajanifolius (3), and C. mollis (1). The genus Rhynchosia was represented by three species: R. minima (9 accessions), R. rothii (6), and R. bracteata (4). Together, the panel encompassed accessions from the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary gene pools of pigeonpea, reflecting broad genetic diversity with considerable variability for resistance reported to diverse biotic and abiotic stresses (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Variability of seed morphological and biochemical traits

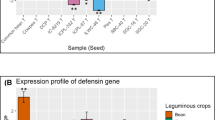

The variation was highly significant among accessions for all the quantitative seed morphological traits (p < 0.001). Seed length varied ~ 2–6 mm while averaged at 4 mm, width ranged ~ 1.4–4.4 mm (~ 2.4), surface area ranged ~ 2.8–19 mm2 (~ 7.9), and 100-seed weight 3.45 g. The highest variability was observed for 100-seed weight (ANOVA = 440.2, CV = 53.2%) and surface area (314.7, 40.9%) followed by other two traits (Table 2, Fig. 2, Supplementary file 1).

Boxplots showing variation in seed morphological (68) and biochemical (17) traits across pigeonpea accessions. Each box displays the interquartile range (IQR), with the middle line indicating the median value. The upper and lower box edges represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR from the quartiles, capturing the spread of most data points, while circles represent outliers lying beyond this range. This visualization highlights both central tendency and variability of traits among accessions. Abbreviations: x100sw, 100-seed weight; sl, seed length; sw, seed width; ssa, seed surface area; prot, protein; tan, tannins; phen, phenols; flav, flavonoids; cho, carbohydrates.

Significant genotypic differences were also observed in biochemical composition (p < 0.001). Proteins ranged between 139–223 mg/g while averaged at ~ 191, tannins ranged ~ 18–47 mg/g (28), phenols 0.93–1.96 mg/g (1.23), total sugars 25–59 mg/g (~ 45), and flavonoids 0.1–0.39 mg/g (0.27). Variability was greatest for sugars, flavonoids and tannins (CV > 25%), while lower for phenols. Among accessions, protein content was highest in G33 and lowest in G34. Tannin content was highest in G34 and lowest in G40. Phenol content was maximum in G26 and minimum in G23, with G26, G60, G27, and G61 remaining on the higher side. Soluble sugars varied widely, with the maximum in G36 and the minimum in G37. Flavonoids peaked in G38, followed by G36, G33, and G34, whereas the lowest value was in G67. Similarly, tannins were abundant in G34, G36, G33, and G32, while G40 exhibited the least (Table 2, Fig. 2, Supplementary file 1.xlsx).

Variability in insect infestation traits

Significant variance in insect traits was recorded between accessions across screening conditions and species (Table 3, Figs. 3, 4, Supplementary file 1). Egg density (ed) varied significantly higher (p < 0.001) among accessions within each species and screening condition. However, the average egg density per seed by three species across accessions was > 1 (1.15–2.5) indicating good egg laying under all screening conditions. Between species, C. chinensis consistently recorded higher average density (~ 2.3–2.5 per seed) under three screening conditions, followed by C. analis (~ 1.5–2.0). While C. maculatus (CM) had lower (1.1–1.5).

Boxplots showing insect traits of pigeonpea genotypes under FC and NC screening conditions across three species. Boxes represent interquartile range (IQR), middle lines denote medians, whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR, and circles indicate outliers. Abbreviations: ed, eggs density; op, oviposition; gd, seed damage; ad, adults density; m, males; f, females; mdp, mean development period; si, susceptibility index; as, adult survivability.

Boxplots showing insect traits of pigeonpea genotypes under CNC screening conditions across three species. Boxes represent interquartile range (IQR), middle lines denote medians, whiskers extend to 1.5 × IQR, and circles indicate outliers. Abbreviations: ed, eggs density; op, oviposition; gd, seed damage; ad, adults density; m, males; f, females; mdp, mean development period; si, susceptibility index; as, adult survivability.

Oviposition (op) differed significantly (p < 0.001) across accessions. For C. analis and C. chinensis, the mean oviposition exceeded 90% under three screening conditions, while C. maculatus displayed more variable oviposition with < 83% in FC and NC (3.33–100%), and higher in CNC (98%, range 90–100%). Seed damage (gd) exhibited the strongest differentiation between accessions (p < 0.001). Overall, the average seed damage (%) did not cross 60, 50 and 26 for C. analis, C. chinensis, and C. maculatus, respectively. Few of the prominent accessions suffered nil damage against three species in three conditions and while susceptible ones suffered higher up to 100%. Between screening conditions, the mean seed damage was higher in FC and NC, while it was lower in CNC. C. analis inflicted consistently higher mean seed damage across accessions and screening conditions followed by C. chinensis and C. maculatus. C. maculatus recorded overall lowest damage, with many accessions sustaining < 10% under CNC.

Total adults (ad), male (m) and female (f) densities also differed significantly between accessions. C. analis and C. chinensis produced > 15 adults per replication (n = 30 seeds) in FC and NC, but numbers were slighly reduced under CNC. C. maculatus recorded far fewer adults overall (mean < 8), with several resistant accessions none. Between species, C. analis produced the highest adult densities, C. chinensis intermediate, and C. maculatus the lowest. However, based on the range values, C. chinensis record up to 55 adults per 30 seeds while against 30 for remaining two species. Adult survivability (as) varied significantly among accessions within each species. In C. analis, survivability averaged ~ 31% in FC, rose to ~ 42% in NC, but dropped to 26% under CNC. C. chinensis recorded > 50% survivability in NC, while C. maculatus was often below 20%. Between conditions, CNC consistently recorded reduced survivability as it contained majority of resistant accessions with one check. Overall, across species, C. analis exhibited the highest survivability, C. chinensis moderate, and C. maculatus the lowest.

Mean developmental period (mdp) also differed significantly. C. analis completed development in ~ 28 days, C. chinensis in ~ 29 days, and C. maculatus required longer (~ 34 days). CNC assays tended to prolong development compared to FC and NC. Susceptibility index (si) index values differed markedly among accessions within species. In C. analis and C. chinensis, the mean SI clustered around 0.04–0.05 under FC and NC but declined in CNC, whereas CM accessions often recorded < 0.04. Overall, the mean SI values were not more than 0.5 across screening conditions and species.

Categorization of resistance reactions

Based on susceptibility index (SI) and seed damage (SD), wild pigeonpea accessions showed wide variability in their resistance to three bruchid species under three screening conditions (Tables 4 and 5).

For C. analis (as per SI), 30 accessions were resistant under FC, 33 under NC, and 20 under CNC. Notable donors included R. bracteata (G26, G27, G60, G61) and several C. scarabaeoides entries (G31–G42, G66, G67, G13, G12, G8, G9). However, SD revealed that R. bracteata (G26, G27, G60, G61) were the only highly resistant (HR) accessions across all test conditions, while C. scarabaeoides accessions were resistant only in FC and shifted to MS or HS in NC and CNC. For C. chinensis (SI), 36 accessions were resistant under FC, 26 under NC, and 22 under CNC. The resistant accessions included R. bracteata (G26, G27, G60, G61) and C. scarabaeoides (G31–G42, G66, G67, G13, G12, G8, G9). However, SD revealed that R. bracteata (G26, G27, G60, G61) were the only highly resistant (HR) accessions across all test conditions, while C. scarabaeoides accessions (G31–42) were resistant in three conditions. Overall, SD confirmed the stability of R. bracteata as HR or R criteria and conditions, while C. scarabaeoides maintained HR to R responses, indicating broader resistance against C. chinensis. However, for C. maculatus (SI), resistance was most widespread, with 51 resistant accessions under FC, 48 under NC, and 22 under CNC. R. bracteata (G26, G27, G60, G61) and C. scarabaeoides (G31–G42, G66, G67, G13, G12, G8, G9) consistently showed resistance to highly resistant across conditions. SD confirmed this pattern, with R. bracteata maintaining HR across conditions, and C. scarabaeoides also showing HR or R responses in most cases.

Variability of insect traits across conditions and species. Identification of key traits driving resistance

Did insect traits vary significantly across conditions within and between species, and which traits contributed?

Multivariate analyses (MANOVA) showed significant effects of both species and screening conditions on insect traits (Table 6 a&b, supplementary file 2). Within-species comparisons of FC vs. NC indicated significant differences for C. analis (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.839, F = 3.51, df = 7128, p < 0.05) and C. chinensis (Λ = 0.859, F = 2.99, df = 7128, p < 0.05), while C. maculatus exhibited a weaker but significant effect (Λ = 0.955, F = 0.86, df = 7128, p < 0.05). Across species, the MANOVA revealed highly significant main effects of species (Λ = 0.452, F = 27.76, df = 14,796, p < 0.001), confirming strong interspecific differences in insect traits, and smaller but significant effects of condition (Λ = 0.935, F = 3.97, df = 7398, p < 0.05). The species × condition interaction was also significant, indicating that the magnitude of condition effects differed among species (Table 6a). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs identified the traits contributing to these effects (Table 6b). In C. analis, seed damage (gd), adult density (ad), and numbers of males (m) and females (f) differed significantly between FC and NC. For C. chinensis, gd and mean developmental period (mdp) were most affected. In C. maculatus, condition effects were mainly reflected in adult emergence traits (ad, m, f). When pooled across species, seed damage, adult emergence, and developmental period were the primary contributors to the observed differences across screening conditions within each species and between species.

What are the key traits driving accessions’ resistance as per SI and SD criteria?

Correlation funnel analysis revealed that between the two resistance outcomes (SD and SI), the influence of insect traits on resistance was significant over seed traits across species which was evident as they trended towards outcome variables (Fig. 5).

Correlation funnel plots showing associations of insect biology and seed traits with resistance levels of pigeonpea accessions observed against three bruchid species. SD and SI were used as outcome variables. Abbreviations: ed, eggs density; op, oviposition; gd, seed damage; ad, adults density; m, males; f, females; mdp, mean development period; si, susceptibility index; as, adult survivability; x100sw- test weigh; sw, seed weight; sl, seed length; ss, seed shape; ssa, seed surface area; scc, seed coat color; sccp, seed coat color pattern; sh, seed hilum; FC, free-choice; NC, no-choice.

For C. analis (as per SD), the funnel showed that lower grain damage (gd) values strongly associated with resistance. In parallel, reduced adult density (ad), females (f), males (m), and adult survivability (as) aligned with resistant accessions. Conversely, higher values of these insect traits trended towards susceptibility. This pattern confirms that resistance to C. analis was largely due to restricted adult emergence and reproduction, thereby minimizing seed damage. The SI-based funnels highlighted a complementary picture: lower damage (gd) and higher development time (mdp) were major contributors towards resistance. Accessions with delayed adult development (high mdp) and minimal adult emergence (low ad, m, f, as) exhibited low SI values, reflecting stronger resistance. For C. chinensis (SD), resistance was again tied to lower gd and reduced adult emergence traits (ad, m, f, as). High mdp values also aligned with resistance. Accessions that delayed or suppressed emergence, maintained resistance across both FC and NC conditions, showing consistency in the outcome. The SI-based funnels revealed a strong negative correlation between resistance and adult emergence traits (ad, m, f, as). Higher mdp reinforced this resistance trend. These results suggest that accessions resistant to C. chinensis prolong insect development while limiting adult establishment, thus reducing susceptibility. In C. maculatus, resistance in SD funnels was driven by lower gd, along with suppressed ad, m, f, and as. Interestingly, resistance was also tied more closely to seed morphological traits than in CA or CC, suggesting a larger role of antixenosis (smaller seed size and surface area). The SI funnel confirmed this pattern: resistant accessions consistently showed reduced egg density and oviposition. High mdp contributed to resistance, but the effect was less pronounced than in C. analis or C. chinensis, pointing towards morphological rather than purely antibiosis mechanisms in C. maculatus resistance.

Across all six funnels, a consistent pattern emerged: wild pigeonpea resistance was primarily driven by traits that reduce insect multiplication (low ad, m, f, as) and extend development time (high mdp). Direct seed damage (gd) and susceptibility index (SI) served as reliable resistance discriminators, with SI integrating multiple biological determinants. Morphological traits, though minor, contributed species-specific resistance cues, particularly for C. maculatus. Thus, correlation funnel analysis provided a clear and ranked view of the key drivers of wild pigeonpea resistance, reinforcing the importance of insect biological parameters while also validating the roles of seed morpho-traits. Across species, the pattern of stronger link of resistance to seed damage, lower emergence and survivability (as), and prolonged mean development period (mdp) anticipate stronger antibiosis as a key mechanism. Species-specific differences were also evident. In C. analis and C. chinensis, resistance was largely driven by antibiosis, as indicated by lower damage, emergence and extended development times. While for C. maculatus, it was due to antixenosis on majority accessions except for few prominent ones.

Validation and prediction of key traits driving bruchid resistance in wild pigeonpea accessions

Random forest models demonstrated excellent performance in classifying pigeonpea accessions into resistant and susceptible categories based on seed traits. Across all datasets and targets, classification accuracy exceeded 99%, with areas under the ROC curve (AUC) approaching 1.0 (Table 7; Supplementary file 3). Models trained on the 68-accession dataset (insect + seed morpho traits) achieved near-perfect classification: for rflag_sd, accuracy was 99.9%, sensitivity 1.0, and specificity 0.998 (AUC = 0.999); for rflag_si, accuracy was 99.8%, sensitivity 1.0, and specificity 0.996 (AUC = 1.0). Similarly, the 17-accession dataset (insect + seed morphological + seed biochemical traits) yielded perfect discrimination, with both rflag_sd and rflag_si models achieving 100% accuracy and AUC = 1.0, though these results should be interpreted cautiously due to the smaller sample size.

ROC curves confirmed excellent separation of resistant and susceptible classes for both resistance flags (Fig. 6). Variable importance rankings consistently identified seed damage (gd) and adult emergence traits (ad, m, f) as the strongest insect predictors. Among seed descriptors, 100-seed weight and seed surface area emerged as key morphological predictors, while phenolics and flavonoids contributed significantly within the biochemical subset (Fig. 7). Supplementary outputs (Supplementary file 4 and 5) provide additional transparency through full ranked importance scores, partial dependence plots, and confusion matrices.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showing model performance for rflag_sd and rflag_si predictions (Area under the curve (AUC) values are indicated in Table 6).

Response based grouping of accessions vis-à-vis insect and seed traits using FAMD and hierarchical clustering

FAMD effectively captured the multivariate structure of resistance in pigeonpea accessions (Figs. 8, 9). For C. analis, the 68-accession FAMD plots showed clear separation of resistance groups. Under seed damage (SD), highly resistant (HR) and resistant (R) accessions formed distinct clusters on the negative side of Dim1, while highly susceptible (HS) accessions grouped on the positive axis. Moderate categories (MS, MR) overlapped partially, reflecting intermediate responses. For susceptibility index (SI), clustering was less distinct, but resistant categories still trended towards separation. In the 17-accession plots (insects + seed biochemical), HR and R categories again grouped separately from HS, confirming that biochemical traits reinforced resistance categorization. For C. chinensis, the 68-accessions FAMD revealed similar structuring, with HR and R accessions clustered tightly apart from HS on the positive Dim1 axis. SI-based grouping separated MR and S categories more clearly, with resistant groups localized towards negative coordinates. In the 17-accession analysis, biochemical traits improved discrimination: resistant accessions formed a compact cluster, while the lone HS accession (G23) appeared isolated, confirming its distinct susceptibility.

FAMD plots showing the grouping of pigeonpea 68 genotypes based on insect traits and resistance categories. Each figure presents three paired plots (Callosobruchus species- CA, CC, CM) for seed damage (SD, left) and susceptibility index (SI, right). Genotypes are colored by resistance categories, with 95% confidence ellipses drawn to illustrate group clustering.

However, for C. maculatus, resistance patterns were stronger than other species. In the 68-accessions plots, HR and R accessions grouped tightly on the left-hand side of Dim1, whereas HS and S clustered distinctly on the right. SI plots highlighted antixenosis-driven resistance, as resistant accessions overlapped but remained distinct from susceptible categories. The 17-accession plots further underscored this: HR and R accessions formed a cohesive group influenced by biochemical defenses, while susceptible accessions were widely dispersed. The clear separation supports the interpretation that C. maculatus resistance is mediated both by oviposition deterrence and biochemical composition. Overall, across species, the FAMD plots confirmed that resistance categories derived from insect traits aligned well with multivariate clustering. Inclusion of biochemical traits in the 17-accession subset provided further resolution, especially for distinguishing intermediate categories.

Hierarchical clustering revealed clear but species-specific accession groupings (Figs. 10 and 11). When insect resistance traits were combined with seed morphological traits across the 68 accessions, three to four distinct clusters were consistently observed per species (Fig. 10). In C. analis, clusters differentiated resistant accessions (e.g., G26, G27, G60, G61) from susceptible accessions (e.g., G23, G34, G35), with seed damage and adult emergence traits contributing strongly to separation. C. chinensis displayed broader divergence, with one large cluster grouping mostly susceptible accessions (e.g., G59, G52, G55) showing high seed damage and emergence, and a smaller cluster comprising resistant accessions with low oviposition and damage. In C. maculatus, clusters were less sharply separated, but resistant accessions (G26, G27, G60, G61) consistently grouped together, highlighting shared defense responses.

Hierarchical clustering heatmaps of 68 wild pigeonpea genotypes screened against three species using insect bioassay and seed morphological traits. Clustering was performed with Ward’s minimum variance method based on standardized (Z-score) data. Warmer colors indicate higher trait values, cooler colors lower values. Abbreviations: Callosobruchus analis (CA); C. chinensis (CC); and C. maculatus (CM); ed, egg density; op, oviposition; gd, seed damage; ad, adult density; m, males; f, females; mdp, mean development period; as, adult survivability; si, susceptibility index; x100sw, 100-seed weight; sl, seed length; sw, seed width; ssa, seed surface area.

Hierarchical clustering heatmaps of 17 wild pigeonpea genotypes incorporating insect, seed morphological and biochemical traits for three species. Warmer colors indicate higher trait values, cooler colors lower values. Abbreviations: CA, Callosobruchus analis; CC, C. chinensis; CM, C. maculatus; ed, egg density; op, oviposition; gd, seed damage; ad, adult density; m, males; f, females; mdp, mean development period; as, adult survivability; si, susceptibility index; x100sw, 100-seed weight; sl, seed length; sw, seed width; ssa, seed surface area.

When biochemical traits were incorporated for the 17 selected accessions, discrimination improved further. Clustering separated resistant accessions (e.g., G26, G27, G60, G61) from highly susceptible accessions (e.g., G23), with biochemical traits such as phenols, tannins, and flavonoids contributing significantly. In C. analis and C. chinensis, biochemical profiles reinforced resistance groupings previously identified by insect traits alone, while in C. maculatus, inclusion of biochemical data revealed more refined subgrouping among moderately resistant accessions. Notably, susceptible accessions exhibited consistently low levels of phenolic compounds, aligning with higher insect survival and seed damage. These results indicate that biochemical defense traits complement insect and morphological data, improving discrimination of resistance categories across species.

Role of antibiosis in accessions’ resistance against bruchid species

Correlation analysis revealed distinct associations between biochemical seed traits and insect developmental parameters across the three Callosobruchus species (Fig. 12). In C. chinensis, strong positive correlations were observed among insect traits such as grain damage, adult emergence, and susceptibility index (r > 0.85***), confirming their reliability as indicators of susceptibility. Phenols and tannins displayed significant negative correlations with grain damage and adult emergence, indicating their role in resistance. Protein content showed moderate positive correlations with oviposition and egg density, particularly under free-choice conditions, suggesting its influence on insect fecundity. For C. analis, a similar trend was noted, with insect traits remaining strongly interrelated and Phenols and tannins negatively associated with infestation parameters. Carbohydrates and flavonoids exhibited weak or inconsistent correlations, reflecting limited involvement in resistance. In C. maculatus, grain damage and adult emergence were again tightly correlated (r > 0.9***), while phenolic compounds consistently showed negative correlations with susceptibility traits. Overall, across species and conditions, phenols as major followed by tannins, emerged as key biochemical defenses against bruchids, while protein contributed variably and carbohydrates and flavonoids appeared less influential (Fig. 13).

Heatmaps showing Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between seed biochemical traits and insect biology parameters across three bruchid species under three screening conditions. Positive and negative correlations are represented by red and blue gradients, respectively, with significance levels indicated (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Abbreviations: CA, Callosobruchus analis; CC, C. chinensis; CM, C. maculatus; FC, free-choice; NC, no-choice; CNC, confirmatory no-choice; op, oviposition; ed, egg density; gd, seed damage; ad, adult density; m, male density; f, female density; mdp, mean developmental period; as, adult survivability; si, susceptibility index; x100sw, 100-seed weight; sl, seed length; sw, seed width; ssa, seed surface area; prot, protein; tan, tannins; phen, phenols; cho, carbohydrates; flav, flavonoids.

Does sex ration is influenced by germplasms resistance levels?

The sex ratios of three bruchid species recorded on all the accessions across resistance classes in different screening conditions were consistently female-biased (mean < 0.5). In both seed damage–based and susceptibility index–based classifications, the average proportion of males remained below 0.5, indicating predominance of females among emerged adults. Across resistance classes, resistant accessions (HR, R, MR) generally exhibited stronger female bias, with lower sex ratios than moderately susceptible or highly susceptible accessions. In contrast, susceptible categories (MS, S, HS) displayed slightly elevated sex ratios, approaching but not exceeding 0.5, suggesting a relative increase in male emergence under higher susceptibility but without reversing the overall female dominance. Condition-specific comparisons showed that NC assays tended to yield higher sex ratios than FC assays, implying that less favorable screening conditions may reduce the degree of female bias. Species-level differences were also observed: C. analis consistently showed stronger female bias than other two species, though all three species followed the same broad trend of female dominance across resistance classes. Mixed-effects models supported these observations. For both resistance classes, species and condition effects were statistically significant (p < 0.05), while resistance class effects were weaker but retained significance in interaction with species. Post-hoc contrasts indicated that differences between resistant and highly susceptible classes were significant in several species–condition combinations. Diagnostic checks confirmed adequate model fit, and beta regression provided consistent results. A concise summary of statistical outcomes is provided in supplementary file 6. Full model summaries, ANOVA outputs, Tukey comparisons or pairwise contrasts, and diagnostic plots are retained in the supplementary file 7 for transparency and reproducibility.

Discussion

Wild pigeonpea relatives are known to contribute valuable traits for multiple biotic and abiotic stresses, andsome also serve as cytoplasmic male sterility sources (Table 1). Although earlier studies evaluated a few wild species against one or two bruchids22,23,24, the present work22,23,24 identifies and validates bruchid-resistance donors with broader applicability using high throughput screening against multiple Callosobruchus species. Notably, it provides the first empirical evidence of convergent high in R. bracteata, underscoring its potential as a durable resistance donor.

Earlier literature only broadly recognized Rhynchosia spp. as wild relatives with potential sources of tolerance to pod borer (Helicoverpa armigera), pod fly (Melanagromyza obtusa), and SMD, and abiotic stress adaptation such as drought tolerance16,56,58,64,68. However, no accession-level evaluations had been conducted, and their donor potential remained largely theoretical due to severe crossability barriers with cultivated pigeonpea. R. bracteata accessions (G26, G27, G60, G61) exhibited consistence and convergent high resistance across C. analis, C. chinensis, and C. maculatus under FC, NC, and CNC, establishing them as robust multi-species bruchid-resistant donors.

C. scarabaeoides has been frequently reported as a donor for many biotic (including C. maculatus, pod borer, pod fly, pod wasp, Fusarium, SMD, and nematode) and abiotic (draught, salinity and aluminium toxicity tolerance) stresses16,22,56,67,69. Similarly, C. platycarpus (accession ICPW-130) was previously reported to be tolerant to C. macualtus with 16% seed damage23. In this study, multiple accessions of C. scarabaeoides (G31–G42, G66, G67, G13, G12, G8, G9) showed resistant to highly resistant reactions, especially against C. chinensis and C. maculatus. However, their convergence across screening conditions occurred only as per SI and not as per SD. Likewise, accessions of C. platycarpus (G20–G22, G43–G47, G50) displayed resistance to the same species, in agreement with earlier reports22,23,24, but did not exhibit full convergence across SI and SD like R. bracteata, indicating species-specific rather than broad-spectrum resistance.

C. crassus and C. cajanifolius have been reported to harbor CMS sources and disease resistance, and two accessions (ICPW-30, ICPW-31) of C. cajanifolious were also reported as resistance against C. maculatus and C. chinensis32. However, in this study none of the accessions of C. crassus or C. cajanifolius showed notable bruchid resistance. Three underexplored taxa (C. mollis, R. minima, R. rothii) were evaluated for the first time for bruchid resistance. R. rothii was previously noted mainly for drought tolerance60. Similarly, R. minima has rarely studied for pest resistance. No accessions from these species showed bruchid resistance. Collectively, these findings expand the evidence base for lesser-studied wild relatives in pigeonpea improvement.

The convergence in resistance across species, conditions and indices (SI and SD) for prominent accessions confirms their status as robust, multi-species resistant donors. Importantly, SI did not classify any accession as highly susceptible under any species or condition, highlighting a baseline tolerance in wild relatives. The distinction between true convergent high resistance (R. bracteata) and partial resistance (C. scarabaeoides) provides clear pre-breeding guidance: the former are ideal for immediate deployment in durable resistance breeding, while latter serve as species-specific resistance sources. These accessions belong to secondary to quaternary gene pools, which face significant transfer challenges due to crossability barriers, linkage drag, and sterility14,58,67,70. Advances in embryo rescue, tissue culture, molecular breeding, and genome editing14 offer new avenues to harness these resources effectively.

Regarding criteria used for resistance categorization, the seed damage (SD) scoring emerged as the most reliable indicator of stable bruchid resistance. Although susceptibility index (SI) reflects host suitability for insect development35,37, its reliance on mean developmental period (MDP) can lead to misclassification, particularly where delayed development reduces SI despite substantial seed damage25,36. Correlation funnel, MANOVA, Random Forest, FAMD, and clustering consistently identified seed damage and adult emergence as key predictors, validating SD-based HR and R accessions as the most stable donors.

Seed size plays a critical role in supporting bruchid larval development. Female bruchids carefully assess seeds for adequate resources, influencing oviposition behavior. Among the species studied, C. maculatus is the largest5; it laid fewer eggs on smaller seeds , resulting in lower seed damage, adult densities, and survivability, leading many accessions to appear resistant primarily due to non-preference. In contrast, C. chinensis (3–4 smaller than C. maculatus), being much smaller, deposited more eggs and survived on many accessions except those expressing strong antibiosis. C. analis (~ 1.2–1.5 times smaller than C. maculatus) exhibited greater adaptability, surviving on small-seeded accessions by reducing F1 body size and persisting even on accessions resistant to the other two species. This species tolerated a broader biochemical spectrum, making it the most challenging species.

Most pigeonpea accessions displayed strong resistance to C. maculatus due to antixenosis. However, some accessions of R. bracteata and C. scarabaeoides received higher egg loads from C. maculatus yet remained resistant, attributable to elevated phenolic content, indicating antibiosis. Seed morphology (100-seed weight,surface area) contributed to non-preference, while phenols and tannin provided effective antibiosis. Similer findings were reported by Hamzei et al.71, who showed that biochemical (phenol, tannin and anthocyanin) and physical traits determined seed susceptibility or resistance to C. maculatus. Species-specific responses revealed that C. chinensis and C. maculatus were most suppressed by high-phenol, high-tannin accessions, whereas C. analis survived wider biochemical range, rendering many accessions that resisted the other two species only moderately resistant or susceptible. Overall, accessions with minimal seed damage, low adult densities, reduced survivability, and prolonged MDP showed stable resistance.

Across species and conditions, all traits showed highly significant genotypic variation, confirming the existence of resistant and susceptible accessions. Between species, C. analis was the most aggressive pest, C. chinensis intermediate, and C. maculatus the least damaging. Across conditions, CNC validated resistance accessions by putting them under maximum pressure with higher oviposition and egg density.. Further, lower infestation traits and higher mdp, in CNC than FC and NC validated the consistent convergence of resistance accessions.

Multivariate (MANOVA) and univariate (ANOVA) analyses showed that bruchid resistance in wild pigeonpea is shaped by both species identity and experimental conditions. Significant inter-specific variation on accessions reflected biological differences among C. analis, C. chinensis, and C. maculatus, matching earlier reports24,25. SD- and SI-based resistance classifications were generally consistent, but trait sensitivities reflected distinct mechanisms: in C. analis and C. chinensis, antibiosis dominated, with reduced seed damage, suppressed emergence, and delayed development which previously recognized as strong indicators of resistance35,37. In contrast, resistance to C. maculatus was associated mainly with seed morphology, indicating antixenosis as a major mechanism72.

The correlation funnel approach effectively highlighted the biological and morphological traits driving bruchid resistance in pigeonpea. Traits influenced by antibiosis consistently defined resistance across species, consistent with earlier findings in legumes73,74. These patterns parallel Aidbhavi et al.25, where resistance in wild Vigna was almost exclusively explained by lower seed damage, adult survivability, and egg density, with minimal role of seed morphology, reinforcing antibiosis as the central mechanism. In pigeonpea, however, seed morphological traits contributed for antixenosis against C. maculatus. Some accessions of R. bracteata and C. scarabaeoides received higher oviposition yet remained highly resistant indicating a biochemical defense. Thus, accessions categorized as resistant solely due to small seed size may not be reliable donors, whereas biochemically mediated resistance provides more durable resistance sources. Collectively, these findings indicate that antibiosis is the dominant mechanism, with antixenosis providing a minor, species-specific layer.

Machine learning approaches, particularly Random Forest have been widely used for pests detection, prediction and forecasting, and crop yield performance modelling75,76,77. Recently, Random Forest has been employed for disease-resistance prediction using multi-omics data78,79. This study is the first to apply Random Forest to predict key bruchid-resistance governing traits. Grain damage, insect emergence, and seed weight consistently emerged as the strongest predictors, highlighting contributions from both host and insect traits. These findings corroborate reports identifying insect emergence traits as accurate classifiers of bruchid-resistance26,80. Stronger model performance in the 68-accession dataset underscores the importance of adequate sample size for machine-learning stability81,82, while the smaller biochemical dataset (17 accessions) yielded exploratory but less stable predictions, emphasizing that biochemical or omics traits require larger sampling scales for robust inference. These results reinforce the feasibility of integrating machine-learning tools with phenotypic and biochemical screening to enhance bruchid-resistance breeding pipelines in pigeonpea.

The FAMD analysis demonstrated that resistance against Callosobruchus species is a multivariate trait, jointly shaped by insect bioassay outcomes and biochemical factors. Previous studies73,83,84 emphasized the roles of antixenosis and antibiosis, particularly seed coat and chemical traits. The present results support this: resistant accessions clustered distinctly in FAMD plots, especially when biochemical traits were included. FAMD captures both quantitative and qualitative dimensions, enabling accession groupings that mirror biological resistance patterns. Aidbhavi et al.25 highlighted the utility of FAMD for grouping accessions based on trait interactions; here, FAMD extends these insights by visualizing how traits jointly structure accession groupings and reinforce predictor traits identified using other tools. These results confirm that SD and SI resistance flags reflect integrated trait interactions, not arbitrary thresholds.

The clustering analyses further support the fact that insect resistance in pigeonpea is shaped by both insect and seed biochemical traits. The strong separation of resistant versus susceptible accessions aligns with previous reports shwoing that biochemical defenses play central roles in limiting bruchid infestation73,74,85. Similar multivariate clustering approaches have been effective in identifying key bruchid-resistance traits in pigeonpea and other legumes32,86. Importantly, biochemical traits enhanced resolution among moderately resistant lines, suggesting that integrating these enhances accuracy in breeding for durable resistance.

The group correlation patterns confirm that seed biochemicals, especially phenols and tannins, are key denterminants of resistance. Their consistent negative association with grain damage and adult emergence supports the role of seed antibiosis, where chemical defenses limit insect development. Similar effects of phenolics and tannins have been reported in other legumes26,73,74,86. Conversely, protein showed positive correlations with oviposition and egg density, suggesting its role as a nutritional cue, though responses varied across conditions. Carbohydrates and flavonoids exhibited weak or inconsistent relationships, implying a minor role in resistance. Some specific chemicals and antinutritional compounds were reported to influence the legumes resistance against pod fly and borers68,69,83,84,87. Thus, investigating the role of these factors in bruchid-resistance would be valuable.

Sex ratio analysis explored whether resistance levels influenced male–female patters, based on hypothesis that the insect development (emergence, MDP) reflects host suitability. Results demonstrated slightly female-biased (sex ratio < 0.5) across accessions, resistance classes, species, and conditions. Female dominance was stronger on across accessions irrespective of resistance classes, with only slight male-bias in susceptible accessions. These pattern agree with ecological evidence showing that sex-specific survival differences arise under variation in host quality and stress88. Previous studies report female bias ratios under restricted or stressful environments89,90. However, in haplodiploid sawflies91 and parasitoid wasps92, sex ratios shift adaptively depending on host quality, with high-quality hosts producing female-biased offspring. Understanding bruchid sex allocation under differing host types may require integrating host quantity (seed density) with host quality parameters for better clarify in adaptive patterns..

Summary and conclusion

This study represents the most comprehensive evaluation of bruchid resistance in wild pigeonpea, involving 68 accessions from multiple gene pools screened against three destructive species namely C. analis, C. chinensis, and C. maculatus. Notably, this is the first systematic screening including C. analis, a neglected yet highly destructive species. Seed damage (SD)- resistance categorization proved more reliable than susceptibility index (SI) for identifying true resistant donors. Across three screening conditions resistance varied significantly, with Rhynchosia bracteata (IC15815, IC15816, IC15817 and IC618509) consistently exhibiting stable, convergent highly resistant reactions across all species and conditions. Several C. scarabaeoides accessions also resistance, especially to C. chinensis and C. maculatus, though reactions were less stable against C. analis.

Advanced analyses confirmed that seed damage, adult emergence, and developmental period as the strongest predictors of resistance. MANOVA, ANOVA, correlation funnels, and machine learning consistently highlighted antibiosis as the dominant mechanism, with antixenosis contributing mainly against C. maculatus.. FAMD and clustering further confirmed biologically meaningful grouping of accessions, strengthened by biochemical traits suc as phenols and tannins which showed strong negative correlations with susceptibility. Collectively, this study identifies R. bracteata as a robust multi-species resistance donor and C. scarabaeoides as a species-specific source, establishing both as invaluable resources for developing bruchid-resistant cultivars. It also highlights integrating traditional screening with advanced analytical tools strengthens donor identification pipelines and accelerates targeted breeding for durable resistance in pigeonpea..

Funding statement

The authors are highly grateful to Indian Institute of Pulses Research (IIPR), Kanpur under Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), New Delhi, for in-house funding support during the study.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Revanasidda, S., Bandi, S. M., Verma, P., Bapatla, K. G. & Singh, B. A systematic methodology to assess bruchid field infestation and the impact of field-carry-over infestation in stored pulses. J. Food Legum. 33, 262–264. https://doi.org/10.59797/jfl.v33i4.571 (2020).

Kingsolver, M. J. Handbook of the Bruchidae of the United States and Canada (Insecta, Coleoptera), 1 and 2. (2004) https://www.ars.usda.gov/is/np/Bruchidae/BruchidaeVol1.pdf (Accessed 19 Sep 2025).

Mishra, S. K. et al. Bruchid pest management in pulses: Past practices, present status and use of modern breeding tools for development of resistant varieties. Ann. Appl. Biol. 172, 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/aab.12401 (2017).

Bano, R., Gupta, K. & Sharma, R. M. Pulse beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Retrieved from https://zsi.gov.in/WriteReadData/userfiles/file/Checklist/Checklist%20of%20Pulse%20Beetles.pdf (2015).

Aidbhavi, R., Soren, K. R., Bandi, S. M., Ranjitha, M. R. & Kodandaram, M. H. Infestation, distribution and diversity indices of bruchid species on edible stored pulses in India. J. Stored Prod. Res. 101, 102085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2023.102085 (2023).

NITI Aayog. Strategies and Pathways for Accelerating Growth in Pulses towards the Goal of Atmanirbharta. https://niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2025-09/Strategies-and-Pathways-for-Accelerating-Growth-in-Pulses-towards-the-Goal-of-Atmanirbharta.pdf (2025).

Jha, S. N., Vishwakarma, R. K., Ahmad, T., Rai, A. & Dixit, A. K. Report on assessment of quantitative harvest and post-harvest losses of major crops and commodities in India. ICAR-All India Coordinated Research Project on Post-Harvest Technology, ICAR-CIPHET, Ludhiana (2015). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3024.3924

NABCONS. Study to determine post-harvest losses of agri-produces in India. https://www.mofpi.gov.in/sites/default/files/study_report_of_post_harvest_losses.pdf (2022).

Mesterházy, Á., Oláh, J. & Popp, J. Losses in the grain supply chain: Causes and solutions. Sustainability 12, 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062342 (2020).

Nayak, M. K. et al. Resistance to the fumigant phosphine and its management in insect pests of stored products: a global perspective. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 65, 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025047 (2020).

Aidbhavi, R., Muralimohan, K. & Bandi, S. M. The status of resistance to phosphine in common bruchid species infesting edible stored pulses in India. J. Stored Prod. Res. 103, 102164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2023.102164 (2023).

Began, M., Harper, J. L. & Townsend, C. R. Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities, 2nd ed. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 945. (1990). https://doi.org/10.2307/2807146

Jaba, J., Bhandi, S., Deshmukh, S., Pallipparambil, G. R., Mishra, S. P. & Arora, N. Identification, evaluation and utilization of resistance to insect pests in grain legumes: advancement and restrictions. In Saxena, K. B., Saxena, R. K. & Varshney, R. K. (eds) Genetic Enhancement in Major Food Legumes, 93–110. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64500-7_7

Bohra, A. et al. Harnessing the potential of crop wild relatives through genomics tools for pigeonpea improvement. J. Plant Biol. 37, 83–98 (2010).

Nagaraja, N. R. et al. Genetic diversity studies and screening for Fusarium wilt (Fusarium udum Butler) resistance in wild pigeonpea accessions, Cajanus scarabaeoides (L.) Thouars. Indian J. Plant Genet. Resour. 29, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-1926.2016.00017.6 (2016).

Sharma, S. et al. Reaping the potential of wild Cajanus species through pre-breeding for improving resistance to pod borer, Helicoverpa armigera, in cultivated pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.). Biology 11, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11040485 (2022).

Mishra, R. K. et al. Identification of resistance sources against Fusarium udum (Race-2) in wild accessions of pigeon pea for strengthening the pre-breeding program. Indian Phytopathol. 75, 1197–1203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42360-022-00560-2 (2022).

Karrem, A. et al. Understanding resistance mechanisms in crop wild relatives (CWRs) of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.) against pod borer Helicoverpa armigera (Hub.). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-025-02392-1 (2025).

Singh, G. et al. Introgression of productivity-enhancing traits, resistance to pod borer and Phytophthora stem blight from Cajanus scarabaeoides to cultivated pigeonpea. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 26, 1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-020-00827-w (2020).

Singh, G. et al. Unlocking the hidden variation from wild repository for accelerating genetic gain in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1035878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1035878 (2022).

Sharma, P. et al. Inheritance and molecular mapping of restorer-of-fertility (Rf) gene in A₂ hybrid system in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan). Plant Breed. 138, 741–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12737 (2019).

Mallikarjuna, N. et al. Progress in the utilization of Cajanus platycarpus (Benth.) Maesen in pigeonpea improvement. Plant Breed. 130, 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2011.01870.x (2011).

Jadhav, D. R., Mallikarjun, N. & Rao, G. V. R. Callosobruchus maculatus resistance in some wild crop relatives and interspecific derivatives of pigeonpea. Indian J. Plant Prot. 40, 40–44 (2012).

Mishra, S. K. et al. Characterization of host response to bruchids (Callosobruchus chinensis and C. maculatus) in 39 genotypes belonging to 12 Cajanus spp. and assessment of molecular diversity inter se. J. Stored Prod. Res. 81, 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2019.02.001 (2019).

Aidbhavi, R. et al. Screening of endemic wild Vigna accessions for resistance to three bruchid species. J. Stored Prod. Res. 93, 101864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101864 (2021).

Mannava, N. et al. Bionomics of Callosobruchus analis (F.) in ten common food legumes. J. Stored Prod. Res. 98, 102010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2022.102010 (2022).

Revanasidda, et al. An improved screening method for identification of resistance to bruchids in pulses. J. Food Legumes 34, 654–667 (2021).

McCabe, W. L., Smith, J. C. & Harriott, P. Unit Operations of Chemical Engineering. 1130 pp (McGraw-Hill Press, 1986). https://evsujpiche.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/unit-operations-of-chemical-engineering-5th-ed-mccabe-and-smith.pdf

Mahajan, R. K. et al. Minimal Descriptors (For Characterization and Evaluation) of Agri-Horticultural Crops (Part I). National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, New Delhi, 230 pp (2000).

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L. & Randall, R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6 (1951).

Thimmaiah, S. K. & Thimmaiah, S. K. Standard Methods of Biochemical Analysis. 49–77 (Kalyani Publishers, 1999). ISBN 81–7663–067–5.

Sadasivam, S. & Manickam, A. Biochemical Methods for Agricultural Sciences. (Wiley Eastern Limited, 1992). ISBN: 8122403883.

Bray, H. G. & Thorpe, W. Analysis of phenolic compounds of interest in metabolism. In Methods of Biochemical Analysis, 27–52 (1954). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470110171.ch2

Hillis, W. E. & Swain, T. The phenolic constituents of Prunus domestica. II.—The analysis of tissues of the Victoria plum tree. J. Sci. Food Agric. 10, 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/JSFA.2740100211 (1959).

Howe, R. W. A parameter for expressing the suitability of environment for insect development. J. Stored Prod. Res. 7, 63–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-474X(71)90039-7 (1971).

Seram, D., Senthil, N., Pandiyan, M. & Kennedy, J. Resistance determination of a South Indian bruchid strain against rice bean landraces of Manipur (India). J. Stored Prod. Res. 69, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2016.08.008 (2016).

Sulehrie, M. A. Q., Golob, P., Tran, B. M. D. & Farrell, G. The effect of attributes of Vigna spp. on the bionomics of Callosobruchus maculatus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 106, 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1570-7458.2003.00019.x (2003).

Nitesh, S. D., Parashuram, P. & Shilpa, P. TraitStats: Statistical Data Analysis for Randomized Block Design Experiments (R package version 1.0.1). https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/TraitStats/ (2021).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag, 2016). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html

Auguie, B. & Antonov, A. gridExtra: Miscellaneous functions for “Grid” graphics (R package version 2.3). Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gridExtra (2017).

Dancho, M. correlationfunnel: Speed up Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) with the Correlation Funnel (R package version 0.2.0). CRAN. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=correlationfunnel (2020).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–26 (2008).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2, 18–22 (2002).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 25, 1–18 (2008).

Kassambara, A. & Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses (R package version 1.0.7) (2020). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra

Kolde, R. pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps (R package version 1.0.13) (2025). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap

Harrell, F. E. Jr Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous (R package version 5.1–2). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc (2024).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Warton, D. I. & Hui, F. K. C. The arcsine is asinine: The analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology 92, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1890/10-0340.1 (2011).

Lenth, R. V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (R package version 1.8.5). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (2021).

Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models (R package version 0.4.6). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (2022).

Cribari-Neto, F. & Zeileis, A. Beta regression in R. J. Stat. Softw. 34, 1–24 (2010).

Brooks, M. E. et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 9, 378–400 (2017).

Sharma, H. C., Pampapathy, G. & Reddy, L. J. Wild relatives of pigeonpea as a source of resistance to the pod fly (Melanagromyza obtusa Malloch) and pod wasp (Tanaostigmodes cajaninae La Salle). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 50, 817–824 (2003).

Saxena, K. B., Kumar, R. V. & Rao, P. V. Pigeonpea nutrition and its improvement through breeding. J. Crop Prod. 5, 227–260 (2002).

Mallikarjuna, N. Wide hybridization in pigeonpea as a tool for interspecific gene transfer. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 63, 1–18 (2003).

Srivastava, N., Vadez, V., Upadhyaya, H. D. & Saxena, K. B. Screening for intra and inter specific variability for salinity tolerance in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.) and its related wild species. SAT eJ. 2, 1 (2006).

Lamichaney, A. et al. Overcoming seed coat–imposed dormancy in wild species of Cajanus and Rhynchosia. Crop Sci. 64, 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.21130 (2024).

Khoury, C. K. et al. Crop wild relatives of pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.]: Distributions, ex situ conservation status, and potential genetic resources for abiotic stress tolerance. Biol. Conserv. 184, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.01.032 (2015).

Remanandan, P. The wild pool of Cajanus at ICRISAT, present and future. Proc. Intl. Workshop Pigeonpeas 2, 29–38 (1981).

Mallikarjuna, N., Jadhav, D. & Reddy, P. Introgression of Cajanus platycarpus genome into cultivated pigeonpea. C. cajan. Euphytica 149, 161–167 (2006).

Mallikarjuna, N., Jadhav, D. R., Srikanth, S. & Saxena, K. B. Cajanus platycarpus (Benth.) Maesen as the donor of new pigeonpea cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) system. Euphytica 182, 65–71 (2011).

Srivastava, N., Singh, R. & Mallikarjuna, N. Resistance to sterility mosaic disease in wild relatives of pigeonpea. Plant Pathol. J. 22, 214–218 (2006).

Upadhyaya, H. D., Reddy, K. N., Singh, S. & Gowda, C. L. L. Phenotypic diversity in Cajanus species and identification of promising sources for agronomic traits and seed protein content. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 60, 639–659 (2013).

Mallikarjuna, N., Sharma, H. C. & Upadhyaya, H. D. Exploitation of wild relatives of pigeonpea and chickpea for resistance to Helicoverpa armigera. J. SAT Agric. Res. 3, 4 (2007).

Parde, V. D., Sharma, H. C. & Kachole, M. S. Protease inhibitors in wild relatives of pigeonpea against the cotton bollworm/legume pod borer, Helicoverpa armigera. Am. J. Plant Sci. 3, 627–635 (2012).

Ngugi-Dawit, A. et al. A wild Cajanus scarabaeoides (L.) Thouars, IBS 3471, for improved insect-resistance in cultivated pigeonpea. Agronomy 10, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10040517 (2020).

Sameer, K. C. V., Satheesh Naik, S. J., Mohan, N., Saxena, R. K. & Varshney, R. K. Botanical description of pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.]. In The Pigeonpea Genome, 17–29 (Springer, 2017). https://oar.icrisat.org/10485/1/Botanical%20Description%20of%20Pigeonpea.pdf

Hamzei, M., Golizadeh, A., Hassanpour, M., Fathi, S. A. A. & Abedi, Z. Interaction between life history parameters of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) with physical and biochemical properties of legumes species. J. Stored Prod. Res. 102, 102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2023.102111 (2023).

Schoonhoven, L. M., van Loon, J. J. A. & Dicke, M. Insect–Plant Biology, 2nd edn. 421 pp (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Sathish, K., Jaba, J., Katlam, B. P. & Mishra, S. P. Biochemical components conferring resistance to pigeonpea genotypes against Callosobruchus chinensis (L.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) under semitropical storage conditions. Legume Res. 47, 2182–2188 (2022).

Sharma, S. & Thakur, D. R. Biochemical basis for bruchid resistance in cowpea, chickpea and soybean genotypes. Am. J. Food Technol. (2014). https://worldveg.tind.io/record/53190/

Iordache, M. D., Mantas, V., Baltazar, E., Lewyckyj, N. & Souverijns, N. Application of random forest classification to detect the pine wilt disease from high resolution spectral images. In IGARSS 2020–2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 4489–4492. (IEEE, 2020). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9324293

Zhang, L., Xie, L., Wang, Z. & Huang, C. Cascade parallel random forest algorithm for predicting rice diseases in big data analysis. Electronics 11, 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11071079 (2022).

Jadesha, G. et al. Smart solutions for maize farmers: Machine learning-enabled web applications for downy mildew management and enhanced crop yield in India. Eur. J. Agron. 164, 127441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2024.127441 (2025).

Upadhyaya, S. R. et al. Genomics-based plant disease resistance prediction using machine learning. Plant Pathol. 73, 2298–2309. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.13988 (2024).

Mohamedikbal, S. et al. Integrating multi-omics and machine learning for disease resistance prediction in legumes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 138, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-025-04948-2 (2025).

Jackai, L. E. N. & Asante, S. K. A case for the standardization of protocols used in screening cowpea, Vigna unguiculata for resistance to Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 39, 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-474X(01)00058-3 (2003).