Abstract

Swelling laminated rock exhibits inherent anisotropy due to the preferred orientation of mineral grains and/or cracks which consequently impact its deformation behavior in terms of strain distribution and crack pattern during water–rock interaction (WRI). The classical method of measuring swelling deformation with dial gauges can not reveal the complex process of strain accumulation and the complex characterization in such interaction of water-anisotropic rock. In this work, we applied optical techniques along with image processing to measure tensile strain development across the surface of laminated rocks with various lamination angles under unconfined swelling testing conditions, thereby investigating their swelling behavior. Full-field strain development was monitored over time and the role of lamination in the overall expansion of the samples was identified utilizing the digital image correlation (DIC) technique. The results show that the tensile strain is distributed at the laminations and localizes at the cracks formed during imbibition. The direction of laminated rock expansion is perpendicular to the lamination and independent of the angle of the lamination. Laminated rocks preferentially crack in the lamination plane during free imbibition and form cracks that intersect the lamination planes at a small angular angles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Swelling is a water–rock interaction (WRI) phenomenon1,2. When in contact with water, fine-grained sedimentary rocks containing certain clay minerals such as montmorillonite can present considerable volume change3,4. Depending on the boundary conditions, this expansion will result in an increase of volume or even breakdown and sometimes mobilizing high swelling pressures. The deformation of swelling rock alters the stress–strain response of the surrounding rock, thereby jeopardizing the safety of embankment fills, transportation infrastructure, and underground engineering and potentially triggering geological hazards5,6; it can also affect reservoir wellbore integrity and the long-term stability of geological carbon dioxide (CO2) storage7,8.

Due to a non-linear deposition accompanied by biological and diagenetic processes, highly heterogeneous and laminated formations are frequently formed in sedimentary rocks9,10,11. The lamina is the smallest megascopic layer (commonly, fractions of millimeters to millimeters in thickness) without internal layers in a sedimentary succession12. The laminated rocks, therefore, are usually treated as a transversely isotropic medium13,14. The deformation behavior of transversely isotropic rocks changed as a function of the orientation of the lamination such as the uniaxial compression behavior15, the tensile behavior16, and the triaxial compression behavior17 as well as the free swelling behavior18. Wakim et al.19. evaluated the degree of free swelling anisotropy of Tournemire shale and found that not only the swelling intensity is varied with the angles of lamination but the kinetics swelling seems slower in the case of the measurement direction parallel to bedding. Similar experimental investigations were performed by Chai et al.20. who reported that the swelling of clayey rock was anisotropic due to the bedded and layered structures. However, previous evaluations of the free swelling of anisotropic rocks were commonly based on the average swelling strain recorded by traditional pointwise, contact measurement methods—such as strain gauges, linear variable differential transformers (LVDT), extensometers, and dial indicators (dial gauges)—which are limited to reporting only the overall expansion of specimens and therefore neglect the contribution of lamination to anisotropic deformation behavior. Furthermore, with these methods it is not possible, at a given time step, to obtain temporally resolved full-field strain development, to localize high-strain regions, or to dynamically track the initiation and propagation of cracks throughout the entire imbibition process. Consequently, improving the study of material behavior21,22 and achieving accurate strain measurement are crucial, as they directly affect the prediction of important material properties23. To reach these goals, we utilize a non-contact optical technique—digital image correlation (DIC)—to create quantitative maps of full-field deformation over time during the entire imbibition process, thereby capturing spatial heterogeneity linked to lamination and enabling the identification of strain concentrations and crack evolution that conventional single-point instruments inherently miss.

Since Chu et al.24. introduced the fundamentals of the DIC technique, it popularized in detecting the displacement and the strain fields across the surface of a specimen as a real-time, non-contact, and flexible measurement. It received a widespread application first in the mechanical behavior test of transversely isotropic rocks such as the indirect tensile test23, the uniaxial creep test25, and the uniaxial compression behavior15 in which the heterogeneity deformation, failure process, and fracture pattern of rocks are captured successfully. The application of this technique in the field of water–rock interaction is receiving increasing attention. Wang et al.26,27,28,29,30. combined DIC with ESEM to conduct an experimental investigation for the nonlinear and time-dependent swelling behavior of argillaceous rock under a controlled relative humidity environment. Parrikar et al.31. illustrated the DIC technique in characterizing the free swelling behaviour of naturally fractured shale samples with different clay content. Chuprin et al.32. investigated the effect of salt type and concentration on the free swelling behaviour of heterogeneous shales using the DIC technique.

In this study, the free anisotropic swelling behaviour of argillaceous siltstone was investigated and the evolution of full-field strain was obtained using digital image correlation. Thin section analysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Atterberg limits were utilized to assess the swelling potential of tested samples. Cubical specimens were prepared at various angles of lamination (0°, 35°, 55°, and 90°). The average vertical swelling strain for tested specimens was recorded by a dial gauge over time. It combined with the full-field strain development to better understand how the lamination behaves in terms of laminated rock swelling. Then, the time dependency of the swelling intensity was evaluated based on anisotropy and angle of lamination. The cracking pattern induced by the clay hydration and swelling in laminated rocks was evaluated and predicted.

The DIC-derived patterns of strain evolution and fracture development can be used to identify high-risk zones for support structures and drainage in underground works within swelling laminated rocks33,34, thereby enhancing overall stability. They also facilitate monitoring of near-well permeability and stress redistribution during hydrocarbon production from shale, ensuring the integrity of reservoir wellbores35,36. In addition, they help identify high-risk, poorly sealed areas at geological CO₂ storage sites, thereby guiding confining-pressure management and the placement of monitoring stations to ensure storage security.

Studied material

Petrographic description

Laminated siltstones of the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation are widespread across the Sichuan Basin, and the formation hosts important tight-sandstone hydrocarbon reservoirs in the region37. In engineering practice, the principal challenge posed by these rocks is the pronounced anisotropy of their swelling behavior, which is widely recognized as a dominant driver of rock-mass instability. Elucidating how sedimentary lamination governs swelling deformation is therefore of immediate practical relevance to excavation-intensive applications, including transportation infrastructure, tunneling, oil-and-gas drilling, and hydraulic fracturing. Accordingly, this study investigates lacustrine facies clastic sedimentary rocks sampled from the Shaximiao Fm in the Sichuan Basin (Fig. 1). The rock samples have a laminated texture with the thickness of 1–2 mm consisting of small-scale sedimentary structures. The laminae are defined by changes in grain size. Thin slices for optical microscopy and light polarizing microscope were prepared and analyzed from the rock samples. The surface of samples is very heterogeneous, and some macro pores and micro-cracks are also observed in Fig. 2a. It appears that the reddish brown beddings are associated with a coarse-grained texture, while the light gray color is associated with a fine-grained texture.

Petrologic analysis indicated that the rock sample is a fine-grained siltstone with a matrix of quartz and feldspar (Fig. 2b–c). The cement consisted of chlorite and clay minerals. The particles are angular to subangular and range in size from 0.01 to 0.5 mm. Flakes of muscovite and biotite are evident, and these were typically larger than the feldspar grains and bent and deformed due to compression. Orthoclase is the main type of feldspar. Some feldspar grains are surrounded by inclusions of chlorite or clay minerals, its weathering product. The shape of chlorite is flake or needle-like with grain sizes between 0.05 mm and 0.09 mm. The porosity was qualitatively estimated to be 10% by studying the thin-section scans of samples.

Mineralogical investigation and estimated swelling potential

Prior studies have used a variety of approaches to comprehensively evaluate the swelling potential of rock samples38. Among these, the Atterberg limits are a standard method for clays13,39. The Atterberg limits comprise the liquid limit, the plastic limit, and the plasticity index. Materials exhibiting both high liquid limit and high plastic limit are typically stiff in the dry state but undergo a marked loss of strength upon wetting. Based on plasticity index and established classification criteria, swelling potential can be directly assessed. In addition, this study quantifies the proportion of swelling clay minerals by X-ray diffraction (XRD). Combined with the Atterberg limits, the XRD results provide a mineralogical, mechanistic basis for interpreting the swelling potential of the samples analyzed here.

XRD analysis shows that the typically layered material is mainly composed of 31 wt% quartz, 32 wt% feldspar, 4 wt% hematite, and 27 wt% clay minerals, with micas and biotitic minerals making up the majority of the rest. Besides, it is observed that the clay component is mainly composed of 33 wt% chlorite and 67 wt% highly swelling montmorillonite (Fig. 3).

For the Atterberg limits test, the rock was crushed, ground, and sieved (0.125 mm). The fine fraction was mixed with distilled water to form a homogeneous paste2, after which the liquid limit and plastic limit were determined as 35.3% and 10.9% respectively, then the plasticity index could be calculated to be 24.4%. According to published classification criteria4,38, these values indicate a moderate swelling potential for the samples.

Sample preparation

To reduce heterogeneity, four cubic samples with different lamination angles were serially cut from the same irregular parent block; the cut boundaries between adjacent samples were contiguous (Fig. 1).

To avoid hydration caused by wet cutting, we used diamond raw cutting and grinding on a lathe under dry conditions. To minimize mechanical or thermal damage during cutting, we employed a low cutting speed with a slow feed; the cutting of each sample was brief, and ample pauses were inserted between operations to allow natural air cooling of both the cut faces and the blade, preventing appreciable heat build-up. After preparation, all sample surfaces were inspected to confirm the absence of heat-related discoloration, scorching, or newly formed cracks. Each sample face was then finely polished to remove any potentially disturbed surface layer, yielding an end-face non-planarity within ± 0.05 mm (Fig. 5). The prepared samples were subsequently equilibrated for a sufficient period in a temperature-controlled laboratory to match ambient temperature and humidity. This protocol preserves, to the greatest extent possible, the original state of water-sensitive rocks against preparation artefacts.

The dimensions and basic parameters of the samples are listed in Table 1. The adopted sample size is consistent with prior DIC-based studies of rock swelling and has been shown to be optimal for capturing full-field strain at the lamination scale in heterogeneous argillaceous rocks31,32. This scale is large enough to express the macroscopic lamination fabric, yet small enough to minimize inter-sample material heterogeneity.

For clarity, because natural rocks possess mild intrinsic heterogeneity, the samples inevitably exhibit small differences in initial dimensions and moisture content. Our evaluation metric is strain, which is a normalized measure of deformation and therefore removes any influence of sample size. Furthermore, the experiments show that lamination angle is the primary control on swelling deformation. Consequently, these minor inter-sample differences do not materially affect the reliability or fairness of the comparisons and the final results retain robust, meaningful comparability. Figure 4 shows the definition of the orientation of laminations and the images of the DIC-facing side of the four specimens taken using a digital microlens reflex camera.

Experimental procedure

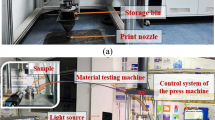

The unconfined swelling test was performed in the acclimatized room to minimize the effect of temperature or humidity changes. Throughout the entire test duration (> 48 h), the ambient temperature was maintained at 23 ± 1 °C. As the specimens were fully submerged in water, their deformation was insensitive to ambient humidity; nonetheless, the relative humidity in the laboratory remained stable. There was no additional external pressure exerted on the specimens. A typical unconfined swelling testing diagram combined with the DIC system is shown in Fig. 5. The test was conducted using the ISM-CONTR-VG5-2DB series non-contact video strain displacement precision measurement system (Imetrum, Bristol, UK). Once the specimens were prepared, a high-contrast speckle pattern required for DIC analysis was created on the front surface. This was achieved by applying a fine mist of matte white spray paint from a distance of approximately 30–40 cm. The preparation aimed to produce a random, isotropic pattern consistent with the best practices for DIC analysis, which recommend an average speckle size of 3–5 pixels and a density of approximately 50% for optimal accuracy. The painted surface faces the digital camera to capture deformation images over time. The spatial resolution of the image is 3840 × 2160 and the average length-pixel ratio of the imaging system is about 0.02 mm/pixel. The LED bulb is leveled with the specimen to ensure the speckle paint pattern can be identified clearly by the camera. For stability, the experimental system is mounted on an antivibration table40. The time intervals for capturing images were set based on the swelling behavior studies on rocks as follows:

-

For the first 2 h at a frequency rate of 1/60 Hz, 120 pictures were taken

-

For the next 2 h at a frequency rate of 1/300 Hz, 24 pictures were taken

-

For the next 36 h at a frequency rate of 1/600 Hz, 216 pictures were taken

-

For the next 10 h at a frequency rate of 1/1800 Hz, 20 pictures were taken

After image acquisition, the changes in the specimen’s speckle pattern were analysed using the analysis software (Imetrum Video Gauge) bundled with the DIC system, yielding displacement and strain data across the entire specimen surface. Meanwhile, a dial gauge was placed on the top of the specimen to record the vertical displacement over time throughout the test. DIC computer integrated with the dial gauge to get the synchronized displacement data with images at the same time steps. The average strain of the vertical direction was calculated by the following formula:

where ∆z is the displacement recorded by the dial gauge, and z is the height of specimens. The test is terminated by ε ≤ 0.001 mm over two hours and a total time of at least 48 h.

Before commencing the formal experiments, we calibrated the DIC measurement system to assess its accuracy. A non-deforming aluminum plate, comparable in size to the rock sample, was prepared with a speckle pattern using the same control standards and procedures as for the sample. The plate was mounted on a precision linear translation stage and positioned at the same location used for the submerged rock sample, under laboratory conditions identical to those of the formal tests. Prescribed rigid-body displacements were then applied in the in-plane direction (parallel to the plate surface) and the out-of-plane direction (normal to the plate surface). Images were acquired concurrently and analyzed with the DIC system. Because rigid translation should generate zero strain, the resulting deformation fields provide a direct check of system accuracy. The results are summarized in Table 2. Overall, the mean systematic (spurious) strain produced by the DIC analysis under imposed translations was very small—below 0.1% in all cases. The out-of-plane translations yielded relatively larger spurious strain, and this error increased with displacement amplitude. To minimize DIC error in the formal tests, we therefore kept the direction of maximum swelling—normal to the sample lamination—parallel to the imaging plane.

Results and analysis

Free swelling behaviour of laminated rocks

Time is a fundamental parameter for describing the swelling behavior of rocks. Figure 6 shows the trend of swelling strain over time for laminated rock samples. Three distinct stages of rock swelling, the rapid swelling stage, the slow swelling stage, and finally, the stable stage can be observed in the figure. The displacement is linearly increased initially due to the thirst of the clay minerals in dry samples to the water, namely the rapid swelling stage. The swelling deformation at the slow swelling stage follows immediately into a non-linear deceleration growth pattern after reaching a certain point. Finally, the swelling tends to stabilize due to the balance between the internal stress and the cemented strength of rocks. The three stages of sample swelling are the same as the imbibition of rocks with no laminations which were reported by Liu et al.41. and Wang et al.42. This result reveals that the presence of laminae texture does not alter the overall evolution trends of vertical average deformation during water–rock interaction.

The formulation governing the evolution of swelling strains with time is borrowed from Wittke-Gattermann et al.43. in the present paper, which assumes an exponential convergence of the current swelling strain towards the final swelling strain. This model, which is mathematically equivalent to a Kelvin creep model, is widely used for describing the time-dependent deformation of argillaceous rocks44,45 and is consistent with the physical swelling process as it converges to a finite final strain. The dashed lines in Fig. 6 are the fitted results of the borrowed model using the least square method. The coefficients of determination for the fitting results are all higher than 0.95, indicating that the time dependency of the average swelling strain of argillaceous siltstone with different lamination angles can be precisely fitted by the adopted model.

The trend of the swelling intensity regarded by the final average swelling strain was evaluated based on the angle of lamination of samples (0°, 35°, 55°, and 90°). The swelling intensity of the samples displayed an overall trend of decreasing from 0° to 90°. For current observation, normal to the lamination (β = 0°), represented a maximum state, whereas the final average vertical swelling strain, parallel to the lamination (β = 90°), corresponded to a minimum state. The swelling potential of the 35° and 55° samples was significantly lower than the 0° sample while they were close to the 90° sample. Previous literature also found a similar trend for shale swelling and clayey rock swelling19,20. An exponential function regression analysis was carried out between the swelling potential and the lamination angles and the obtained regression equations and the coefficient of determination are listed in Fig. 7. The orientation of lamination was also correlated with the kinetics coefficient of swelling which is a fitted parameter obtained by the borrowed model. A general trend was observed that as the angle increased, the kinetics coefficient of swelling decreased. The smaller coefficient leads to a slower behavior of the kinetics of swelling, as Wakim et al.19. pointed out. However, it does not show a clear mapping relationship between the kinetics coefficient of swelling and the lamination angle.

From our analyses, the stage-wise temporal evolution of swelling strain in laminated rocks and the dependence of swelling intensity and swelling potential on lamination angle provide a reference for refined tunnel-lining design that accounts for time-varying stress–strain in the surrounding rock mass. They help determine the deformation allowance for the lining and the scheduling of support and lining installation. In addition, accounting for the lamination angle of the surrounding rock enables optimisation of lining stiffness and expansion-joint layout, reducing risks associated with over-reinforcement. Fits of the swelling-strain time-evolution model can be embedded in coupled reservoir–wellbore models to improve predictions of early- and long-term formation stability during waterflooding, thereby safeguarding reservoir integrity. In shale hydraulic fracturing, incorporating differences in swelling strength arising from lamination angle helps predict fracture orientation and calibrate the critical injection pressure.

Analysis of strain development during free swelling

The DIC analysis of the captured images described the accumulation of strain on the entire speckled surface of the samples over time. The strain measurements at different time steps during testing are provided in the presented study according to the deformation characters at three stages of imbibition. The t1, t2, and t3 were chosen at the rapid swelling stage, while t4 and t5 were arranged at the slow swelling stage and the final state of the tested sample respectively (Fig. 8). The horizontal strain (εyy) and vertical strain (εzz) of samples are presented at these given time terms. These two different strain maps present the perspective on the swelling deformation that occurs during water–rock interaction, namely tensile deformation in two directions. It should be noted that the positive strain values represent tensile strain due to the expansion of rock being dominated by tensile46.

Figure 9a–d shows full-field strain maps of the tested samples in the horizontal and vertical directions as well as images of the sample at the given time term. The lamination is the active and focus area for the swelling deformation of laminated rocks when it is directly exposed to water. Almost every lamination is in the high tensile strain region if there is no crack appearing during imbibition. For instance, the high strain region in the horizontal and vertical strain maps of the 35° sample coincides with the distribution of laminations on the measuring surface. The high strain, of course, would be localized to the cracks induced by clay hydration and swelling while the cracks are initiated and propagated actually at the lamination of rocks, such as the horizontal and vertical strains of the 55° sample, the vertical strain of the 0° sample and the horizontal strain of the 90° sample. The horizontal strain of the 0° sample and the vertical strain of the 90° sample are all heterogeneous and similar to the non-linear swelling behavior of non-laminated argillaceous rock observed by Wang et al.28. One primary reason is that the permeability of laminated rocks is markedly anisotropic. Prior studies47,48 indicate that early-stage hydration of the clay matrix can initially shrink micro-pores, thereby reducing matrix permeability; subsequently, as swelling stresses increase and the rock softens, microcracks are induced along the lamination, increasing local permeability. This evolution of permeability naturally yields a nonlinear, spatially heterogeneous strain field within the rock. During early imbibition, the lamination planes are effectively sealed by the retardation process of the cementing material49,50, yielding low permeability across the lamination plane, whereas the presence of micropores and microcracks affords relatively high permeability parallel to the lamination. As the cementing material hydrates, swells and disintegrates, the along-lamination permeability increases further. Meanwhile, matrix pores normal to the lamination contract and close due to mineral-hydration swelling, which further reduces the permeability across the lamination plane. Meanwhile, as water infiltrates the rock, swelling stresses generated by clay hydration within the laminated matrix—combined with water-weakening effects such as dissipation of capillary suction and reduction in cementing material strength—first trigger microcracks along lamination planes and adjacent weak layers. These microcracks then coalesce and link along the lamination to form macroscopic, lamination-parallel fractures, which further increase permeability parallel to the lamination and produce spatially heterogeneous swelling with locally accelerated rates relative to surrounding regions. From the start of the experiment to the end, it was found that the horizontal strain of the 0° specimen was consistently weaker than the vertical strain. As the angle of lamination increased, the horizontal strain gradually increased, while the vertical strain gradually decreased. Finally, the horizontal strain of the 90° specimen was always stronger than the vertical strain during the testing. Based on the above observations, It can be concluded that the deformation direction of laminated rock expansion is always perpendicular to the lamination plane.

Time-average vertical strain curves (Fig. 6) show that all samples have essentially reached the stable swelling stage twenty hours after the start of the test. This finding is consistent with the results of the free swelling tests on bedding mudstones carried out by Chai et al.20. He, therefore, concludes that there is no need to wait for the swelling to reach a final stable value to begin engineering construction because the largest amount of swelling takes place relatively rapidly. Nevertheless, DIC results show that the cracks are all activated about three hours or so after the start of the test and develop quickly. Therefore, it is possible to track the time points that the key factors affecting swelling behavior could be emergence to treat the problem of rock swelling46.

Both the time-swelling strain curve and DIC strain (εzz and εyy) maps consistently provided the deformation behaviors until the swelling reached the stable stage completely. All of the above observations suggest that DIC is an efficient tool to analyze the dynamic swelling behavior of the sample including deformation development, crack initiation, and propagation. The DIC observations are consistent with the near-wellbore damage simulations for shale-oil formations reported by Wang et al.51, who employed a coupled fluid-mechanics numerical model. The simulations indicate that elevated pore pressure converts local compression into tension, thereby initiating damage. Temporally, both damage and fracture growth exhibit rapid early propagation followed by pronounced deceleration. Spatially, damage preferentially extends along the direction of the initial maximum horizontal principal stress, whereas fracture growth is governed by the lamination direction. Although the external drivers differ between the two studies, the underlying physical mechanisms are shared, and the results mutually corroborate one another.

Analysis of the DIC visualisations identifies the principal swelling direction as normal to the lamination plane, enabling targeted placement of drainage, pressure-relief, and tension-resisting elements in tunnel lining design. Using the characteristic times of rapid crack growth and subsequent stabilisation allows optimised construction scheduling that avoids high-risk windows. In hydrocarbon production, incorporating the principal swelling direction into an anisotropic model of the near-wellbore formation improves predictions of water-induced local stress redistribution. Coupled with the timing of fracture evolution, this supports early warning of casing and wellbore instability. The results also indicate that, during shale hydraulic fracturing, fractures preferentially nucleate near lamination planes; together with the temporal characteristics of fracture growth, this informs optimisation of stage scheduling and fracturing-fluid formulation.

Effect of lamination on the free swelling behavior

Wakim et al.19. proposed an anisotropy coefficient to characterize free swelling anisotropy of rocks with strongly bedded and layered structures and the calculation formula is shown as follows:

where χ = the anisotropy coefficient, ε = the average vertical swelling strain (Eq. (1)). The anisotropy coefficient χ calculated by Eq. (2) is 4.1 for the laminated argillaceous rock in the present study. Currently, the maximum value of this coefficient for sedimentary rocks is 6.5 for the Tuscaloosa marine shale which is provided by Chuprin et al.32, while the minimum value is 4 reported by Wakim et al.19. for the Tournemire shale. Froehlich18 and Chai et al.20. obtained the free anisotropy coefficient for the clayey rock and the diagenetic consolidated claystone is 4.71 and 5 respectively.

As shown on the full-field strain maps in Fig. 9, all samples show the anisotropic free swelling behavior that the laminated rocks tend to expand more in the direction perpendicular to the bedding plane. The preferred orientation of mineral grains and/or cracks is the recognized reason to exhibit the inherent anisotropy of laminated rocks19,20,32,52,53. During the diagenetic process, the clay minerals tend to be arranged regularly undergoing gradual gravitational compression due to the mass of overburden, usually forming a horizontal layered structure, resulting in the micro fabric of rock developing anisotropic properties. Chuprin et al.32. conducted the inspection of a scanning electron microscope (SEM) on the orientation of the clay fakes and substantiated that it is parallel to the bedding plane. The intercrystalline swelling of the clay minerals happened only in a direction normal to the bedding surface (i.e. the C-axis direction of the clay mineral structure)54. Another easily overlooked reason is that the microfractures in the laminated rocks are also oriented parallel to the laminations (Fig. 10). Most micro-cracks, either the ones that exist before the experiment or induced during the immersion through the weak laminations by the imbibed water, are the abundant region of the air-breakage phenomenon (Fig. 2). Terzaghi and Peck55 found that the air pressure buildup occurs in the internal pores due to water entering the developed cracks by surface capillary effect. The pressure developed in the pores exerts tension on the solid skeleton of rocks, causing the material to swell in the direction perpendicular to the cracks46.

The coefficient of anisotropy for free swelling provides input parameters for directional swelling loads in internal-force calculations for tunnel lining design, and it enables optimisation of the relative orientation between the lining and the excavation face, thereby avoiding direct action of the maximum free swelling normal to the lamination plane on the lining. Incorporating the coefficient of anisotropy for free swelling into constitutive models of reservoir formations enhances the credibility of predictions of directional deformation and wellbore stability under injection or imbibition conditions. The coefficient likewise aids assessment of the interaction between fracture growth and rock lamination during shale hydraulic fracturing, enabling optimisation of pump rates and injector–producer well spacing.

Microstructure and cracking pattern

To investigate the underlying microstructural cause of the anisotropic swelling behavior discussed in Section “Effect of lamination on the free swelling behavior”, the fabric of the laminated rock was examined using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The resulting images (Fig. 10) reveal a complex, heterogeneous microstructure that provides a direct explanation for the observed macroscopic phenomena.

At low magnification (Fig. 10, × 150), the rock exhibits a clear fabric with a preferred orientation of platy minerals. At higher magnifications (Fig. 10, × 500 and × 1000), it becomes evident that this fabric is dominated by well-organized aggregates of clay minerals displaying a distinct “book-like” structure. These aggregates are composed of numerous individual clay platelets stacked in a highly parallel alignment. A dense network of inter-platelet micropores and microcracks, also oriented parallel to the lamination, is clearly visible between these platelets. This intrinsic, oriented microstructure is the fundamental reason for the observed anisotropy. Since the swelling of clay minerals occurs primarily perpendicular to the basal surfaces of the platelets, their parallel alignment at the micro-scale culminates in a dominant macroscopic expansion in the direction perpendicular to the lamination. Beyond explaining the anisotropic swelling, this microstructure also dictates the rock’s failure mechanism. The network of aligned micropores and the weak interfaces between clay platelets act as preferential pathways for water infiltration and constitute pre-existing planes of mechanical weakness. Consequently, when swelling-induced stress exceeds the rock’s tensile strength, fractures are most likely to initiate and propagate along these planes. This explains the cracking pattern observed during free imbibition.

The swelling of argillaceous rock commonly is accompanied by cracking56,57. The induced cracks may not only cause the enhancement of rock permeability46 but also allow a greater volume of swelling minerals to adsorb water38. The fracture of argillaceous rock, which contains both brittle and ductile mineral components, exhibits a quasi-brittle behavior. Its crack extension involves energy dissipation through both the creation of new surfaces and inelastic deformation at the crack tip. Therefore, the resistance to crack extension (R) can be described by an energy criterion that accounts for both mechanisms, as proposed by Orowan58:

where Γ is the surface energy per unit area required to form the new crack surface, and Γp is the plastic work consumed by inelastic deformation in the process zone near the crack tip. For a crack to propagate, the swelling stress must be greater than or equal to this total resistance R. According to the research of Orowan58, the effect of material plasticity on crack propagation showed that Гp is more than three orders of magnitude greater than Г. Although the swelling stress is generated by the clay hydration and it is at the plastic region, the microcracks should extend from the plastic material (clay minerals) to the brittle material (Feldspathic and carbonate minerals). This conclusion can be verified by the study of Wang et al.29. who suggested that the propagation path of microcracks is directed by the non-swelling inclusions such as carbonate, silica, or limited swelling aluminosilicates. Macro fracture propagation occurs due to the connection of microfractures59. A large amount of energy would be consumed if the microcracks were connected to cross the lamination interface. Owing to the principle of minimum energy consumption, the optimal direction of microcrack connection is connected in the lamination and ruptured along a small angular angle to the lamination plane due to the surface friction and the inherent viscoelasticity of the matrix minerals60 (Fig. 9). The formation of this fracture pattern can be understood from a mixed-mode fracture mechanics perspective. The primary driving force is the Mode I (tensile) stress generated by swelling perpendicular to the weak lamination planes. However, due to material heterogeneity, non-uniform swelling can induce localized Mode II (shear) stresses along these planes. The frictional resistance of the lamination surfaces opposes this shear, and the viscoelastic properties of the clay matrix affect the rate of stress redistribution. This complex interplay results in a local principal tensile stress at the crack tip that is not perfectly normal to the lamination, leading to the formation of small, angled, en-echelon tensile microcracks. The coalescence of these microcracks ultimately forms the macroscopic fracture path that appears sub-parallel to the laminations. Overall, macroscopic fractures formed during free imbibition of laminated rocks are more likely to develop as single fractures along the lamination plane than as complex webs of fractures61, a phenomenon that differs from the expansion and cracking of unstratified expansive rocks or soils.

The mechanism by which fractures develop along lamination planes informs the layout and design of directional waterproofing and drainage structures, as well as shear-resisting features, at the lining–rock interface. The microstructure-controlled fracture-development pattern indicates that stress redistribution during waterflooding is strongly directional. Accordingly, reservoir-stability assessments should treat weak planes along the rock lamination as primary analysis surfaces and evaluate stability by jointly considering rock permeability and the connectivity pattern of fracture growth. The results further suggest that, during shale hydraulic fracturing, fractures more readily coalesce into a single macroscopic fracture along lamination planes rather than forming a network; this tendency can be leveraged by tuning fluid formulations to enhance the targeted fracture complexity and effective conductivity62.

Conclusion

The imbibition deformation of swelling laminated rocks is non-uniform and has a laminar nature even when the angle of laminations is changed. DIC demonstrates a quick and effective way of investigating the swelling behaviour of laminated rocks at a laminar scale. Not only the strain developments across the sample face over time are provided by DIC, but the local high strain expansion sites are identified. Moreover, the optical techniques tracked dynamically the fracture initiation and propagation of the entire test. This technique can be used as a substitute for traditional physical measurements which are in various limitations. The following conclusions can be made from the study:

-

(1)

The time dependency of the average vertical swelling strain of rocks with different lamination angles can be fitted suitably by the exponential model proposed by Wittke-Gattermann et al.43. The swelling intensity is decreased exponentially by the increase of lamination angles while there is no clear mapping relationship between the kinetics coefficient of swelling and the orientation of lamination.

-

(2)

The swelling high strain regions are located at almost every lamination of the sample (β = 35°) while it will be localized at the crack formed in weak laminations of samples once a crack is activated and developed during imbibition (β = 0°, 35°, and 90°).

-

(3)

The horizontal high strain sites of the 0° sample and the vertical high strain sites of the 90° sample can not position at the lamination and are similar to the non-linear swelling found by Wang et al.28. Apart from that, the high strain sites of the rest of the tensile strain maps are developed along the laminations.

-

(4)

With the increase of the angle of the lamination, the intensity of vertical strain displayed an overall trend of decreasing while the intensity of horizontal strain displayed an overall trend of increasing. The swelling laminated rocks tend to expand more in the direction perpendicular to the lamination plane.

-

(5)

The anisotropy coefficient χ is about 4.1 which is close to the experimental observations of other rocks with bedded and layered structures. The micro investigations provided demonstrated the underlying cause is the preferred orientation of mineral grains and microcracks which is parallel to the orientation of lamination.

-

(6)

Laminated rocks are more likely to form macroscopic fractures that propagate sub-parallel to the lamination planes. This macroscopic path is often formed through the coalescence of smaller, en-echelon microcracks that intersect the laminations at small acute angles.

-

(7)

The DIC-derived results provide guidance for refined tunnel-lining design and improve the accuracy and credibility of stability predictions for reservoir formations and of fracture-evolution forecasts in shale hydraulic fracturing. Their applicability also extends to transportation-infrastructure projects and other underground works.

Data availability

The data analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author (Liliuyang Bai) on reasonable request.

References

Pimentel, E. & Anagnostou, G. New apparatus and experimental setup for long-term swelling tests on sulphatic claystones. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 46(6), 1271–1285 (2013).

Vergara, M. R. & Triantafyllidis, T. Influence of water content on the mechanical properties of an argillaceous swelling rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(7), 2555–2568 (2016).

Yu, X. et al. Cracking of silty mudstone subjected to wetting-drying cycles. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.10.009 (2024).

Vergara, M. R. & Triantafyllidis, T. Swelling behavior of volcanic rocks under cyclic wetting and drying. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 80, 231–240 (2015).

Wu, Q. et al. Theoretical study on stability evolution of soft and hard interbedded bedding reservoir slopes. J. Mt. Sci. 20(9), 2744–2755 (2023).

Zhao, R. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties of highly swelling soft rocks in the Yanji Basin, Northern China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55(3), 1125–1141 (2022).

Tang, J., Zhang, M., Guo, X., Geng, J. & Li, Y. Investigation of creep and transport mechanisms of CO2 fracturing within natural gas hydrates. Energy 300, 131214 (2024).

Tang, J. et al. Re-evaluation of CO2 storage capacity of depleted fractured-vuggy carbonate reservoir. Innov. Energy. 1(2), 100019–100021 (2024).

Peng, J., Zeng, Y., Yang, Y., Yu, L. & Xu, T. Discussion on classification and naming scheme of fine-grained sedimentary rocks. Pet. Explor. Dev. 49(1), 121–132 (2022).

Peng, J., Hu, Z. & Feng, D. The classification scheme for fine-grained sedimentary rocks: A review and a new approach based on five inherent rock attributes. Gondwana Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2025.04.014 (2025).

Ma, X. et al. Developing characteristics of shale lamination and their impact on reservoir properties in the deep Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation shale of the southern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 14(2), 171 (2024).

Campbell, C. V. Lamina, laminaset, bed and bedset. Sedimentology 8(1), 7–26 (1967).

Holtz, W. G. & Gibbs, H. J. Engineering properties of expansive clays. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 121(1), 641–663 (1956).

Ip, S. C. & Borja, R. I. Multiscale interactions of elastic anisotropy in unsaturated clayey rocks using a homogenization model. Acta Geotech. 18(5), 2289–2307 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. A hybrid acousto-optical method for multiscale interpretation of strain localization in sandstone subjected to uniaxial compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 165, 105369 (2023).

Yim, J., Lee, Y., Hong, S. & Min, K. B. Effects of 3D deformation and nonlinear stress–strain relationship on the Brazilian test for a transversely isotropic rock. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15(12), 3221–3229 (2023).

Yang, F. W., Li, B. Y., Du, P. Z. & Liu, Z. H. Weakening effect of water on mechanical properties of brittle shale under triaxial compression. Lithosphere 2023(1), 5065549 (2023).

Froehlich, D. C. Embankment-Dam Breach Parameters. In Ragan, R. M. (eds) Hydraulic Engineering: Proceedings of the 1987 National Conference on Hydraulic Engineering. 570–575. (ASCE, 1987).

Wakim, J., Hadj-Hassen, F. & De Windt, L. Effect of aqueous solution chemistry on the swelling and shrinkage of the Tournemire shale. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 46(8), 1378–1382 (2009).

Chai, Z. Y., Kang, T. H. & Feng, G. R. Effect of aqueous solution chemistry on the swelling of clayey rock. Appl. Clay Sci. 93, 12–16 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. An intelligent lithology recognition system for continental shale by using digital coring images and convolutional neural networks. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 239, 212909 (2024).

Li, J. Y. et al. A large-scale, high-quality dataset for lithology identification: Construction and applications. Pet. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2025.04.013 (2025).

Nath, F. & Mokhtari, M. Optical visualization of strain development and fracture propagation in laminated rocks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 167, 354–365 (2018).

Chu, T. C., Ranson, W. F. & Sutton, M. A. Applications of digital-image-correlation techniques to experimental mechanics. Exp. Mech. 25(3), 232–244 (1985).

Traore, S., Naik Parrikar, P. & Mokhtari, M. Full-field creep mapping in a heterogeneous shale compared to a sandstone. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(1), 89–108 (2023).

Wang, L. L., Bornert, M., Héripré, E., Yang, D. S. & Chanchole, S. Irreversible deformation and damage in argillaceous rocks induced by wetting/drying. J. Appl. Geophys. 107, 108–118 (2014).

Wang, L. L. et al. Microstructural insight into the nonlinear swelling of argillaceous rocks. Eng. Geol. 193, 435–444 (2015).

Wang, L. L. et al. The mechanisms of deformation and damage of mudstones: A micro-scale study combining ESEM and DIC. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48(5), 1913–1926 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Microscale insight into the influence of humidity on the mechanical behavior of mudstones. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 120(5), 3173–3186 (2015).

Wang, L. L., Yang, R. W., Chanchole, S. & Zhang, G. Q. The time-dependent swelling of argillaceous rock under resaturated conditions. Appl. Clay Sci. 146, 186–194 (2017).

Naik Parrikar, P., Mokhtari, M. & Saidzade, A. Measurement of deformation heterogeneity during shale swelling using digital image correlation. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 144(6), 063002 (2022).

Chuprin, M., Naik Parrikar, P., Mokhtari, M. & Hayatdavoudi, A. Using digital image correlation for evaluating the impact of brine on swelling of heterogeneous shales. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55(2), 1013–1035 (2022).

Bai, X. et al. Enhanced domain tuned Yolo-driven intelligent fault identification method: Application in selection and construction of gas storage. Well Log. Technol. 49(01), 47–59 (2025).

Guo, X., Jin, Y., Zi, J., Lin, J. & Zhu, B. A 3D modeling study of effects of heterogeneity on system responses in methane hydrate reservoirs with horizontal well depressurization. Gas Sci. Eng. 115, 205001 (2023).

Guo, X. et al. Numerical investigation of depressurization through horizontal wells in methane-hydrate-bearing sediments considering sand production. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10(11), 1777 (2022).

Guo, X., Jin, Y., Zi, J. & Lin, B. Numerical investigation of the gas production efficiency and induced geomechanical responses in marine methane hydrate-bearing sediments exploited by depressurization through hydraulic fractures. Energy Fuels 35(22), 18441–18458 (2021).

Liang, Q. & Chen, C. Chlorite-induced porosity evolution in multi-source tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study of the Shaximiao Formation in western Sichuan Basin. Open Geosci. 16(1), 20220732 (2024).

Selen, L., Panthi, K. K., Vergara, M. R. & Mørk, M. B. Investigation on the effect of cyclic moisture change on rock swelling in hydropower water tunnels. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54(1), 463–476 (2021).

Peck, R. B., Hanson, W. E. & Thornburn, T. H. Foundation Engineering (John Wiley & Sons, 1991).

Ferrer, B., Tomas, M. B. & Mas, D. Use of image correlation to measure macroscopic strains by hygric swelling in sandstone rocks. Appl. Sci. 11(6), 2495 (2021).

Liu, C. D. et al. Experimental study on the effect of water on mechanical properties of swelling mudstone. Eng. Geol. 295, 106448 (2021).

Wang, T., Yan, C., Zheng, H., Zheng, Y. & Wang, G. Microfracture behavior and energy evolution of heterogeneous mudstone subjected to moisture diffusion. Comput. Geotech. 150, 104918 (2022).

Wittke-Gattermann, P. & Wittke, M. Computation of strains and pressures for tunnels in swelling rocks. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 19(4–5), 422–423 (2004).

Jia, Q., Galindo Aires, R. A., Liu, X. & Xu, H. Effect of slake durability on time dependent swelling behavior of red-bed siltstone in Sichuan Basin. J. Mt. Sci. 21(9), 3123–3138 (2024).

Zhong, Z. et al. Time-dependent swell–shrink behavior of red-bed mudstone under cyclic wetting and drying. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82(12), 470 (2023).

Liu, K., Sheng, J. J. & Zhang, Z. A simulation study of the effect of clay swelling on fracture generation and porosity change in shales under stress anisotropy. Eng. Geol. 278, 105829 (2020).

Bai, T., Hashemi, S., Melkoumian, N., Badalyan, A. & Zeinijahromi, A. Permeability evolution of shale during high-ionic-strength water sequential imbibition. Energies 17(14), 3598 (2024).

Gao, Q., Liu, J., Leong, Y. K. & Elsworth, D. A review of swelling effect on shale permeability: Assessments and perspectives. Energy Fuels. 37(5), 3488–3500 (2023).

Dewhurst, D. N., Yang, Y. & Aplin, A. C. Permeability and fluid flow in natural mudstones. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 158(1), 23–43 (1999).

Wilson, M. J. & Wilson, L. Clay mineralogy and shale instability: An alternative conceptual analysis. Clay Miner. 49(2), 127–145 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Evolution of near-well damage caused by fluid injection through perforations in wellbores in low-permeability reservoirs: A case study in a shale oil reservoir. Lithosphere 2022, 3824011 (2022).

Ip, S. C. & Borja, R. I. Evolution of anisotropy with saturation and its implications for the elastoplastic responses of clay rocks. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 46(1), 23–46 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Nano-scale synchrotron imaging of shale swelling in the presence of water. Fuel 344, 127999 (2023).

Anderson, R. L. et al. Clay swelling—A challenge in the oilfield. Earth-Sci. Rev. 98(3–4), 201–216 (2010).

Terzaghi, K., Peck, R. B. & Mesri, G. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice (John Wiley & Sons, 1996).

Winhausen, L., Khaledi, K., Jalali, M., Bretthauer, M. & Amann, F. The Anisotropic Behavior of a Clay Shale: Strength, Hydro‐Mechanical Couplings and Failure Processes. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth. 128(11), e2023JB027382 (2023).

Wang, H., Cui, Y. J., Vu, M. N., Zhang, F. & Talandier, J. On the hydro-mechanical behaviour of unsaturated damaged Callovo-Oxfordian claystone. Eng. Geol. 319, 107107 (2023).

Orowan, E. Fracture and strength of solids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 12(1), 185 (1949).

Liu, K. & Sheng, J. J. Experimental study of the effect of water-shale interaction on fracture generation and permeability change in shales under stress anisotropy. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 100, 104474 (2022).

Shi, X. M., Wang, G. M., Xiong, Z. H. & Li, M. P. Experimental study on influence of laminae direction on P-wave and S-wave velocities and elastic parameters of shale. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 38, 1567–1577 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Tang, J., Zhang, J., Meng, S. & Li, J. Modeling of scale-dependent perforation geometrical fracture growth in naturally layered media. Eng. Geol. 336, 107499 (2024).

Tang, J., Wang, X., Du, X., Ma, B. & Zhang, F. Optimization of integrated geological-engineering design of volume fracturing with fan-shaped well pattern. Pet. Explor. Dev. 50(4), 971–978 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2025YFE0107200).

Funding

This research received funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2025YFE0107200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.L.: Project Administration, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. L.L.Y.B.: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft. Q.J.J.: Methodology, Visualization, Data Curation. X.M.L.: Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. L.J.Z.: Validation, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors declare that they have all agreed to publish the work reported in this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Bai, L., Jia, Q. et al. Optical visualization of the full-field swelling of laminated rocks. Sci Rep 16, 3554 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33584-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33584-5