Abstract

Mobbing is a major workplace problem that harms employees’ mental and physical well-being, reduces organizational productivity, and undermines social stability. In many regions and organizational contexts, understanding how different generations cope with mobbing has become increasingly important; however, the existing literature provides limited and fragmented evidence. This study offers a comprehensive and context-based analysis by identifying the most effective coping strategies for Generations Y and Z and examining the qualifications that influence their implementation. Data were obtained from five experts specializing in mobbing and organizational behavior. Experts’ importance weights were calculated using a machine learning-based method that incorporates demographic characteristics, criteria weights were determined using the Entropy technique, and strategies were ranked through the CRADIS approach. To address uncertainty in expert evaluations, Pythagorean fuzzy numbers were integrated into the decision-making process. The proposed model contributes to the literature by (1) incorporating demographic-based expert weighting through machine learning, an approach rarely applied in previous studies; (2) developing separate analytical models for Generations Y and Z, thereby clarifying generational differences within a defined regional and organizational context; and (3) applying Pythagorean fuzzy numbers to enhance methodological robustness. Results indicate that for Generation Y, psychological resilience is the most critical qualification, and social activities such as meditation or sports constitute the most effective strategies. For Generation Z, academic education emerges as the key qualification, and leaving the job is identified as the most suitable strategy. The findings confirm distinct generational patterns in coping with mobbing and demonstrate the practical value of the proposed analytical model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mobbing is a serious problem in today’s workplace that must be addressed at individual, institutional, and societal levels. Systematically belittling, excluding, putting excessive pressure on, or subjecting employees to psychological violence primarily threatens individuals’ mental and physical health. It leads to stress, depression, burnout, loss of self-confidence, and even long-term withdrawal from the workplace. This not only reduces an individual’s quality of life but also leads to a loss of motivation at work, decreased productivity, increased absenteeism, and increased employee turnover1. At the institutional level, mobbing damages communication among employees, undermines trust, disrupts team harmony, and hinders innovative and creative work processes. Furthermore, it can damage the organization’s reputation and undermine the trust of both internal and external stakeholders2. On a societal level, it can lead to a loss of individual confidence in their work lives, disruption of production processes, and negatively impact economic productivity. Therefore, developing and implementing ways to combat bullying is a critical necessity not only to protect victims but also to ensure the sustainable success of institutions and the healthy functioning of society3. In this context, preventive policies, awareness campaigns, effective oversight mechanisms, and a supportive organizational culture should be considered essential tools for reducing bullying and establishing a healthy work environment.

There are various methods individuals can employ in the process of dealing with mobbing, both at the organizational and individual levels. The effectiveness of these methods is largely dependent on the skills and psychological resilience of employees. First and foremost, recording mobbing incidents in detail and sharing them with upper management or relevant institutions allows for the formalization and objective evaluation of the process. Furthermore, establishing healthy relationships with upper management facilitates the implementation of internal organizational support mechanisms, contributing to the reduction of victimization4. Meditation, sports, and similar personal development activities increase an individual’s mental resilience and strengthen their capacity to cope with stress. This, in turn, helps reduce the devastating effects of mobbing on an individual. Furthermore, reassigning to a different department or changing workplaces are among the radical yet effective solutions for individuals who want to completely escape the mobbing. For the successful implementation of all these strategies, it is crucial that employees possess certain qualifications. A strong educational background, sufficient work experience, and professional skills facilitate access to alternative solutions and ensure an individual maintains a strong position in the labor market. Furthermore, participating in new training programs, developing professional skills, and being open to continuous learning help employees become more resilient to bullying5. Furthermore, being psychologically help individuals make healthier decisions and take more effective action during this process.

The fact that ways to cope with mobbing can vary across generations is a significant issue in organizational psychology and human resources management. Because Generations Y and Z have different perspectives on work life, value systems, communication styles, and levels of technological adaptation, their preferred coping strategies can also differ. For example, while Generation Y may prefer institutional mechanisms and formal processes based on their experience and work experience, Generation Z tends to lean more toward individual freedom, digital platforms, and quick-fix strategies. Identifying the most effective coping strategies for each generation is crucial for managing these differences. However, a review of the existing literature reveals that research demonstrating which strategies are more effective against mobbing across generations is quite limited. This can be considered a missing gap in the literature and creates a significant gap both theoretically and practically. This deficiency makes it difficult for organizations to develop effective policies that take generational differences into account, leading to employees lacking sufficient support in the face of mobbing, and consequently, to decreases in job satisfaction and productivity. Therefore, the need for new, comprehensive and comparative research to determine which strategies different generations use to cope with mobbing are most appropriate and effective is of critical importance both for the enrichment of academic literature and for establishing organizational practices on a sounder basis.

The primary objective of this study is to identify the most effective strategies for coping with mobbing for different generations and to analyze the qualifications employees must possess during this process. The literature review identifies six different strategies that can be considered in combating mobbing and four key qualifications that play a significant role in implementing these strategies. Within this framework, two separate, original fuzzy decision-making models are developed for both Generation Y and Generation Z employees, aiming to systematically examine intergenerational differences through these models. The study’s dataset is built on the opinions of five different experts in mobbing and organizational behavior. Importance weights are determined based on the experts’ demographic characteristics using a machine learning-based approach, and criteria weights are calculated using the entropy method. The CRADIS approach is used to rank strategy alternatives, and Pythagorean fuzzy numbers are integrated into the method to better manage the uncertainties inherent in the process. This methodological integration enhances the originality of the study and enables a more in-depth analysis of the intergenerational effectiveness of mobbing coping strategies. The motivation for this study is to clarify the differences in intergenerational strategies, which have been limitedly addressed in the literature, and to offer applicable policy recommendations for organizations. In this context, the research seeks to answer the following questions: (1) What strategies are most effective for Generation Y and Z employees in coping with mobbing? (2) Which qualifications play a more critical role in implementing these strategies? (3) What differences in strategy priorities emerge across generations? (4) To what extent can the integration of fuzzy decision making and machine learning reduce uncertainty in the intergenerational strategy-making process?

This study contributes to the literature by presenting a comprehensive and methodologically innovative model that analyzes coping strategies and essential qualifications for different generations through the integration of fuzzy decision-making techniques and machine learning. The novelty of the proposed model is reflected in several dimensions. First, expert importance weights are computed using a machine learning–based dimensionality reduction algorithm that incorporates demographic variables such as age, managerial experience, global experience, and involvement in mobbing-related projects. Unlike most studies that assign equal weights to experts, this data-driven approach captures heterogeneity in expertise and produces more objective, realistic, and reliable assessments. Second, the construction of two separate decision-making models for Generation Y and Generation Z represents a significant conceptual advancement. By explicitly modeling generational differences rather than treating the workforce as homogeneous, the study provides a structured and comparative understanding of how coping strategies vary across cohorts. This dual-model design enables organizations to develop targeted interventions and generationally sensitive policies. Third, the integration of Pythagorean fuzzy numbers enhances the model’s ability to manage uncertainty more effectively than traditional fuzzy sets, including triangular fuzzy numbers, type-2 fuzzy sets, or q-ROF sets. Their greater expressive capacity allows more nuanced representation of expert judgments, improving robustness and accuracy. Additionally, the hybridization of machine learning–based expert weighting, entropy-based qualification weighting, and CRADIS ranking establishes a novel multi-stage analytical architecture that has not been previously applied in mobbing research. Overall, the proposed model extends the methodological boundaries of existing studies and offers a more comprehensive, flexible, and context-sensitive framework for understanding generational differences in coping with mobbing.

Although the proposed framework combines existing techniques, its originality lies in the structured and integrated way these methods are operationalized to address a problem that has not previously been examined through such a comprehensive analytical architecture. The study introduces a multi-layered decision-making model in which expert weighting, uncertainty modeling, and strategy ranking are linked through a sequential and mutually reinforcing process. Unlike traditional approaches, the model incorporates machine learning–based dimensionality reduction to objectively derive expert weights, enhances uncertainty management through Pythagorean fuzzy numbers, and applies Entropy–CRADIS in a generation-specific manner. This hybrid integration is not a simple aggregation of methods; rather, it enables more accurate representation of expert heterogeneity, clearer differentiation between generational groups, and more robust prioritization of coping strategies. As such, the methodological contribution stems from adapting and combining these tools in a novel context and forming a unified decision-making framework that has not been applied in mobbing research before.

This manuscript consists of five different sections. The second section highlights the research gap in the literature. The proposed model is explained in the third section. The results are presented in the following part. The final section is related to the discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

One of the most effective indicators in combating mobbing is the strong educational background and academic development of employees. A strong educational background supports professional development by providing employees with a broader perspective in the job search process6,7. Individuals’ high academic portfolio not only improves their professional competencies but also contributes to more resilient attitudes towards organizational conflicts and increases their self-confidence8,9. Šagátová et al.10 revealed that individuals with doctoral degrees are less exposed to workplace mobbing compared to those with bachelor’s degrees. Almotairy et al.11 stated that employees with advanced nursing education and professional competencies such as strong communication skills are more accepted within teams. Therefore, education is an important protective factor in preventing mobbing and preserving the psychosocial well-being of employees.

One indicator in preventing mobbing is employees’ professional experience. Experienced employees are better equipped to identify negative attitudes they encounter in their professional lives, set boundaries, and develop solutions, so they can be relatively more resilient to mobbing10,12. In contrast, young employees just entering the workforce may be more vulnerable to mobbing due to both their lack of understanding of organizational dynamics and their lack of experience13,14. Banga et al.15, in a study with 5405 participants from 79 countries, found that young employees with a lack of experience were more likely to experience mobbing. Hodgins et al.16 reported in a study conducted in higher education institutions that young employees were highly vulnerable, and employees with higher academic seniority were found to have exceptional power relations. Therefore, not only individual experience but also an ethical and inclusive corporate culture that supports intergenerational learning stands out as a determining factor in preventing mobbing.

Certification programs and additional training are among the key competencies needed to protect employees from mobbing. Such training improves employees’ communication skills, stress management strategies, and awareness of legal recourse17,18. This allows employees to recognize potential mobbing behaviors earlier, develop appropriate coping mechanisms, and evaluate alternative job opportunities19,20. Louw et al.21 reported that physiotherapists with additional certifications have shorter job search times. A study conducted by AlSadah et al.22 on nurses in Saudi Arabia emphasized the importance of additional certification training among employees. Furthermore, employees equipped with certifications and additional training become more visible and valued within the organization, reducing the risk of being pushed into a passive or vulnerable position.

Psychological resilience is an individual characteristic that enables employees to cope with negative workplace experiences such as mobbing. Employees with high psychological resilience can evaluate negative behaviors more objectively by using their emotional intelligence and self-awareness23,24. This allows them to set boundaries and develop effective coping strategies25. Chang et al.26 reported in their study that employees with low perceived well-being experienced higher levels of burnout when exposed to mobbing. Sani et al.27, in their study of Portuguese healthcare workers, indicated that providing psychological support and increasing the resilience of employees exposed to bullying or mobbing can help them overcome the process more easily. Psychological resilience plays a critical role in reducing the negative effects of mobbing.

The literature contains limited studies addressing the role of factors such as education level, professional experience, certification programs, and psychological resilience in preventing mobbing. This leaves organizations with insufficient scientific basis for developing strategies to combat mobbing. Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive evidence on the subject creates a significant gap in protecting employees and sustainably promoting workplace well-being.

Methodology

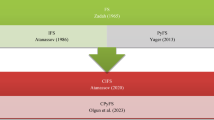

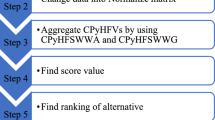

This section includes the description of the model proposed for the analysis in which the strategies for coping with mobbing are prioritized according to generations. The importance coefficient of the experts’ evaluations, or the expertise score, is objectively obtained using a dimensionality reduction algorithm, a machine learning technique. The qualifications necessary to cope with mobbing are then weighted using the Entropy method. Finally, the strategies to cope with mobbing are ranked using CRADIS. The computational process of the proposed model constructed through these steps is illustrated in Fig. 1.

To improve methodological clarity, the present study provides a structured overview of the soft computing techniques applied in the analysis. The model integrates four core components: a dimensionality-reduction–based machine learning algorithm for deriving expert weights, Pythagorean fuzzy sets for handling uncertainty, the Entropy method for determining the importance of qualifications, and the CRADIS approach for ranking coping strategies. Each technique is briefly introduced before the methodological details, ensuring that readers can clearly understand their theoretical foundations and role within the proposed decision-making framework. The equations are given in the appendix part.

Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PFS)

Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PFSs) were first introduced by Yager28, who extended the concept of intuitionistic fuzzy sets by allowing the squared sum of membership and non-membership degrees to be less than or equal to one. This formulation provides greater expressive flexibility and allows decision-makers to model uncertainty more effectively compared to classical or intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Since its introduction, PFS has been widely applied in multi-criteria decision-making, clustering, and uncertainty modeling due to its enhanced representational capacity. This section recalls the definitions of PFS for measuring uncertainty, machine learning for computing expertise scores, entropy method for weighting of qualifications necessary to cope with mobbing, and CRADIS method for ranking of the strategies to cope with mobbing29.

Definition 1

A PFS \(\left(\widetilde{\mathcal{P}}\right)\) in a finite universe of discourse is identified as in Eq. (1).

Wherein \({\mathcal{U}}_{\widetilde{\mathcal{P}}},{\mathcal{V}}_{\widetilde{\mathcal{P}}}:\mathcal{S}\to \left[0, 1\right]\) with the condition in Eq. (2). This condition is the square sum of the degrees of membership and non-membership is smaller than or equal to one.

Definition 2

The indeterminacy degree of \(\mathcal{s}\) to \(\widetilde{\mathcal{P}}\) is described using Eq. (3).

Definition 3

Let \(\mathcal{X}\) and \(\mathcal{Y}\) be any two PFNs. Then, basic algebraic operations are computed in Eqs. (4)–(10).

Dimensionality reduction algorithm

The dimensionality reduction algorithm is an unsupervised machine learning process developed to create a smaller number of latent variables than the observed variables. Experts’ expertise is not the same, and unfortunately, this expertise score cannot be measured directly. However, this latent structure can be obtained through related observed variables. In other words, an expertise score can be calculated by analyzing expertise indicators. This algorithm is used to provide an objective approach to calculating this score. The operation of the algorithm is detailed below30.

Firstly, the observed variables of the experts regarding their expertise are collected and the matrix formed in Eq. (11) is constructed. Wherein \(\mathcal{e}\) and \(\mathcal{o}\) define the number of experts and observed variables, respectively. Then, \({\mathfrak{a}}_{ij}\) refers to the value of the jth observed variable of ith expert. Next, the observed variables are standardized using Eqs. (12)–(15). Afterwards, covariance coefficient values between the standardized observed variables are estimated with Eqs. (16) and (17). After the creating covariance matrix, the eigenvalues of this matrix are obtained by solving Eq. (18). In this case, there are \(\mathcal{o}\) solutions. The maximum of the solutions is determined by Eq. (19).

Wherein identity matrix is symbolized as \(\text{\rm I}\) and det is the determinant function. Later, the eigenvector regarding to \({\lambda }^{*}\) is set by solving Eq. (20). Finally, observed variables are multiplied by \(\theta\) using Eq. (21) and then, the multiplication result is normalized with Eq. (22). Wherein \(\rho\) represents the expertise score as latent variable.

Entropy based-CRADIS

The CRADIS method provides a balanced ranking by comparing ideal and anti-ideal solutions with alternatives. Furthermore, the method offers high stability, particularly through double normalization, ensuring consistent ranking. Furthermore, within the scope of the proposed model, this paper aims to obtain more realistic and accurate results by integrating entropy, a data science-based approach. The steps of entropy based-CRADIS with PFNs are introduced below31.

Firstly, the alternatives are defined and the criteria that determine the selection of alternatives are selected. Next, the alternatives are assessed by experts regarding the criteria with the linguistic expressions. The evaluations are converted to PFNs. These PFNs are multiplied by expertise scores using Eq. (9), and then, summed via Eq. (7). Thus, the values of the decision matrix are obtained. The form of the decision matrix is presented in Eq. (23).

Afterwards, the normalized values are calculated. Equation (24) is used for useful criterion and Eq. (25) is used for useless criterion. The overall entropy for each criterion is computed with the help of Eq. (26). Then, the diversity is estimated by Eq. (27). The last step for Entropy method is that the values of diversity are normalized using Eq. (28). Thus, the weights of criteria are defined. After obtaining the weights of criteria, the weighted normalized decision matrix is constructed via Eq. (29). Afterwards, the ideal and anti-ideal solutions for each criterion are determined. Equation (30) is used for useful criterion and Eq. (31) is used for useless criterion. Wherein score function is identified in Eq. (32).

Next, the deviations from the ideal and anti-ideal solutions are computed by Hamming distance. The Hamming distances for ideal and anti-ideal solutions are defined with Eqs. (33) and (34), respectively. The deviations are normalized with obtaining the utility functions for all alternatives by comparing the optimal alternatives. Equations (35) and (36) are used for this. Finally, the average of utility functions is defined as ranking of alternatives with the help of Eq. (37).

Analysis

This section recalls the results of the analysis in which the strategies for coping with mobbing are prioritized according to generations. The first subsection presents the results of obtaining the expertise scores of experts. The next subsection compares the results across generations.

Obtaining the expertise scores

Observed variables of five experts such as age, global experience, experience in industry, manager experience and number of mobbing projects are collected and presented in Table 1.

When the observed variables in Table 1 are examined, the average age, global experience, experience in industry, manager experience and mobbing projects of five experts equal to 36.6, 16, 31.2, 5.4 and 1.8, respectively. The other descriptive statistics of observed variables of five experts are summarized in Table 2.

According to descriptive statistics of observed variables, the ages of the five experts are between 28 and 44. In addition, all experts have participated in at least one project related to mobbing. Additionally, all the experts are managers. Next, the standardized observed variables are computed by Eqs. (12)–(14). Thus, the standardized matrix given in Eq. (15) is obtained. In other words, 38 − 36.6 = 1.4, then \(\frac{1.4}{{\left( {1.4^{2} + \left( { - 8.6} \right)^{2} + 4.4^{2} + 7.4^{2} + \left( { - 4.6} \right)^{2} } \right)^{0.5} }} = .107.\) The standardized observed variables are shared in Table 3.

Afterwards, covariance coefficient values between the standardized observed variables in Table 3 are estimated by Eq. (16) and thus, covariance matrix formed in Eq. (17) is created. In other word, covariance coefficient between age and global experience is \(\left(\frac{1}{5}\right)\left(.107*\left(-.109\right)+\left(-.657\right)*\left(-.711\right)+.336*.219+.566*.657+\left(-.352\right)*\left(-.055\right)\right)=.184.\) Covariance matrix is illustrated in Table 4.

Eigenvalues are found by solving Eq. (18). The eigenvalues equal to .6694, .09931, .0000, .01185, and .18939. Accordingly, the maximum eigenvalue is .6694 regarding Eq. (19). Later, the eigenvector regarding eigenvalue with .6694 is created by solving Eq. (20). The eigenvector regarding .6694 is displayed in Table 5.

Finally, observed variables in Table 1 are multiplied by the eigenvector in Table 5 using Eq. (21) and then, the multiplication result is normalized with Eq. (22). In other word, first value equals to \(38*.47898 + 14*.48757 + 14*.49784 + 8*.34726 + 3*\left( { - .40549} \right) = 33.559\).Then, first ES is equal to \(\frac{33.559}{{33.559 + 15.499 + 43.108 + 42.333 + 30.745}} = .203\). The multiplication result (MR) and expertise scores (ES) of five experts are expressed in Table 6.

As can be seen ES in Table 6, the most significant assessments belong to Expert 3. When examining the observed variable values for Expert 3, this expert has significantly more industry and managerial experience than the other experts. This expert is second in terms of age and global experience. These characteristics place Expert 3 first in terms of expertise scores.

Comparison of generations

The coping strategies of Generations Y and Z against mobbing are analyzed under separate subheadings. The analysis results obtained by these generations are compared. Recording incidents (RI), strengthening communication with management (SCM), socializing such as meditation or exercise (ME), following legal process (FLP), change in department (CD), and quitting a job (QJ) are determined as strategies to cope with mobbing. Academic education (AE), experience (EXP), additional education such as certification (AEC), and psychological strength (PS) are determined as the qualifications required for the implementation of these strategies.

Generation Y

Evaluations from five experts are collected to evaluate Generation Y’s strategies for coping with mobbing. The evaluations for Generation Y are presented in Table 7.

The evaluations in Table 7 are converted to PFNs for computing with words and analysis under uncertainty. Next, these PFNs are multiplied by the expertise scores in Table 6. Equation (9) is used for this multiplication operation. The multiplication results are then summed. This sum operation is defined in Eq. (7). As a result of this sum, the values of the decision matrix are calculated. The decision matrix for Generation Y is exhibited in Table 8.

Afterwards, the values of decision matrix in Table 8 are normalized using Eqs. (24) and (25). Since all qualifications are of useful type, the matrix obtained as a result of the normalization process is the same as the decision matrix. After the normalization process, the overall entropy for each qualification is computed with the help of Eq. (26). Then, the diversity is estimated by Eq. (27). Finally, the weights of qualifications are defined using Eq. (28). For example, first element is computed as (1 − .904)/(4 − (.904 + .909 + .919 + .889) = .253. The results are summarized in Table 9.

As can be seen from the weights in Table 9, the most important qualification for Generation Y is psychological strength with .293. In addition, the second qualification for Generation Y is academic education. As can be understood from the entropy results, Generation Y prioritizes psychological strength and academic education when determining a strategy to cope with mobbing. After the qualifications are prioritized, a weighted normalized matrix is first constructed with Eq. (29) to rank the strategies. For example, first fuzzy value is calculated as \({\left(1-{\left(1-{.718}^{2}\right)}^{.253}\right)}^{.5}=.410\), \({.290}^{.253}=.731\). The weighted normalized matrix for Generation Y is shared in Table 10.

Afterwards, the ideal and anti-ideal solutions for each qualification are determined using Eqs. (30)–(32). The ideal and anti-ideal solutions for Generation Y are shown in Table 11.

Next, the deviations from the ideal and anti-ideal solutions are computed with the help of Eqs. (33) and (34). Hamming distance metric is used for computing these deviations. The deviations for Generation Y are given in Table 12.

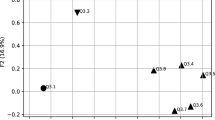

The utility functions for all strategies to cope with mobbing are estimated using Eqs. (35) and (36). Finally, the average of utility functions is defined via Eq. (37). For example, (.013 + .184)/2 = .099. The results for Generation Y are displayed in Table 13.

According to the Q values in Table 13, the most optimal strategy for Generation Y is socializing through activities such as meditation or exercise, which achieved an exceptionally high utility score of 0.969. This value stands out as the clear dominant preference and indicates a strong consensus among experts. The second-ranked strategy, quitting a job, received a utility score of 0.564, which is considerably lower—by more than 40%—than the top choice. This sizable difference reveals that although leaving the job is perceived as an effective alternative, it is not as strongly preferred as stress-reduction and emotional recovery practices.

Moreover, the substantially lower scores observed for other strategies further clarify Generation Y’s coping profile. For instance, following legal procedures produced a moderate utility value of 0.154, while changing departments registered an extremely low score of 0.018, making it the least preferred option. These figures suggest that Generation Y does not consider institutional or organizational mechanisms to be reliable or impactful means of addressing mobbing. Instead, they rely heavily on strategies that allow them to internally regulate stress or detach themselves from the negative environment entirely.

Additionally, the distribution of utility scores demonstrates a distinctive pattern: strategies requiring formal engagement (legal steps, reporting, organizational changes) consistently remain below 0.20, whereas individual-oriented strategies exceed the 0.50 threshold. This contrast highlights a generational tendency to avoid bureaucratic or confrontational processes and to prioritize emotional well-being, self-protection, and rapid stress relief. Overall, these findings portray Generation Y as a cohort that copes with mobbing primarily through personal resilience-building activities or by distancing themselves physically or psychologically from the problematic environment rather than confronting the issue through institutional channels.

Generation Z

Evaluations from five same experts are collected to evaluate Generation Z’s strategies for coping with mobbing. The evaluations for Generation Z are presented in Table 14.

The evaluations in Table 14 are converted to PFNs for computing with words and analysis under uncertainty. Next, these PFNs are multiplied by the expertise scores in Table 6. Equation (9) is used for this multiplication operation. The multiplication results are then summed. This sum operation is defined in Eq. (7). As a result of this sum, the values of the decision matrix are calculated. The decision matrix for Generation Z is exhibited in Table 15.

Afterwards, the values of decision matrix in Table 15 are normalized using Eqs. (24) and (25). Since all qualifications are of useful type, the matrix obtained as a result of the normalization process is the same as the decision matrix. After the normalization process, the overall entropy for each qualification is computed with the help of Eq. (26). Then, the diversity is estimated by Eq. (27). Finally, the weights of qualifications are defined using Eq. (28). The results are summarized in Table 16.

As can be seen from the weights in Table 16, the most important qualification for Generation Z is academic education with .280. In addition, the second qualification for Generation z is psychological strength with .247. As can be understood from the entropy results, Generation Z prioritizes psychological strength and academic education when determining a strategy to cope with mobbing as Generation Y. However, between the two generations, the order between the two is reversed. After the qualifications are prioritized, a weighted normalized matrix is first constructed with Eq. (29) to rank the strategies. The weighted normalized matrix for Generation Z is shared in Table 17.

Afterwards, the ideal and anti-ideal solutions for each qualification are determined using Eqs. (30)–(32). The ideal and anti-ideal solutions for Generation Z are shown in Table 18.

Next, the deviations from the ideal and anti-ideal solutions are computed with the help of Eqs. (33) and (34). Hamming distance metric is used for computing these deviations. The deviations for Generation Z are shared in Table 19.

The utility functions for all strategies to cope with mobbing are estimated using Eqs. (35) and (36). Finally, the average of utility functions is defined via Eq. (37). The results for Generation Z are illustrated in Table 20.

According to the Q values presented in Table 20, the most optimal strategy for Generation Z is quitting a job, which obtained the highest utility score of 0.500. Although this score is moderate compared with the top strategy identified for Generation Y, it still reflects a clear preference among experts for disengagement as Generation Z’s primary response to mobbing. The second-ranked strategy is socializing through activities such as meditation or exercise, with a utility score of 0.374. The gap of approximately 25% between the first and second strategies suggests that Generation Z evaluates job departure as a more decisive and effective option than stress-relief or well-being practices yet still values emotional coping as an important alternative.

In contrast, institutional or formal strategies such as following legal procedures or strengthening communication with management received substantially lower utility values, remaining below the 0.15 threshold. This distribution demonstrates that Generation Z does not perceive organizational channels as efficient or trustworthy tools for resolving mobbing incidents. Instead, they tend to prioritize autonomy, mobility, and personal well-being. Interestingly, while both Generations Y and Z share the same top two strategies, the order in which they prefer them differs. Generation Y clearly favors emotional coping first, while Generation Z shows a stronger inclination toward withdrawing from the workplace altogether. This indicates a generational shift toward rapid exit strategies and reflects Generation Z’s lower tolerance for negative organizational climates and stronger reliance on alternative employment opportunities.

Discussion

The findings reveal that the preferred strategies for coping with mobbing and the qualifications that increase their effectiveness vary across generations. The fact that psychological resilience is the most critical qualification among Generation Y highlights their need to develop resistance to stressors in the workplace32. Therefore, strategies that enhance individual resilience, such as meditation, sports, and social interaction, are prominent among Generation Y33. The prominence of academic education among Generation Z reflects this generation’s desire to prove themselves in the business world and increase their competitiveness34. The fact that Generation Z sees leaving their job as the most effective strategy against mobbing points to their individual freedom, search for alternatives, and quick-solution-oriented approach35. These results suggest that institutions should develop more targeted support mechanisms that take generational differences into account36. For example, strengthening psychological counseling and stress management programs for Generation Y, and education and career development opportunities for Generation Z, may be beneficial37.

However, it should be noted that the results do not fully align with all findings in the literature. Different studies have found different qualifications or strategies to be more important. This does not mean that the other factors identified in the study are unimportant. On the contrary, factors such as psychological resilience, academic education, social activities, or job departure are the only factors highlighted in this study, and context, cultural differences, industry dynamics, or sample structure may lead to variations in the results38. Therefore, the findings of this study offer a new contribution to the literature and demonstrate that coping strategies against mobbing are not absolute truths but rather context-sensitive variables39. In this context, future research should re-examine generational differences with larger samples, apply similar models to different industries or cultures, and conduct multidimensional analyses, which will increase the generalizability of the results40.

Conclusion

This study aims to identify the most effective strategies for coping with mobbing for different generations and the qualifications that play a critical role in implementing these strategies. Based on six strategies and four qualifications identified in the literature, two separate fuzzy decision-making models were developed for both Generation Y and Generation Z. Using expert-based data, experts’ importance weights were calculated through a machine learning–based dimensionality reduction approach, criteria weights were determined via the Entropy method, and strategy alternatives were ranked using the CRADIS technique, with Pythagorean fuzzy numbers employed to manage uncertainty. The quantitative results of the analysis highlight the strength of the proposed model: for Generation Y, psychological resilience received the highest qualification weight with 0.293 and social activities such as meditation or sports achieved the highest utility score with 0.969; for Generation Z, academic education had the highest weight with 0.280 and quitting a job ranked as the most effective strategy with a utility score of 0.500. These numerical findings clearly demonstrate the generational distinctions captured by the model and emphasize its contribution to identifying actionable and evidence-based coping patterns. The study’s originality lies in developing separate generational models, integrating demographic-based expert weighting through machine learning, and combining entropy-based importance evaluation with CRADIS ranking under Pythagorean fuzzy uncertainty. In this context, the study offers a robust alternative to existing models that overlook generational variability and assume equal expert competence, providing both theoretical advancement and practical policy implications for organizations.

The findings of this study provide several important implications for managers, human resource professionals, and organizational decision-makers. First, the clear generational differences identified in coping strategies highlight the need for tailored support mechanisms within organizations. For Generation Y employees, initiatives that strengthen psychological resilience—such as wellness programs, mindfulness training, and stress-management workshops—can significantly enhance their ability to cope with mobbing. In contrast, for Generation Z employees, career development opportunities, continuous learning programs, and transparent communication about advancement may reduce their tendency to leave the organization when faced with mobbing. Moreover, the low utility scores associated with formal mechanisms such as legal procedures or departmental changes indicate a lack of trust in organizational processes. This suggests that organizations must improve reporting systems, ensure confidentiality, and enforce anti-mobbing policies more effectively. By integrating generational needs into organizational policies and support structures, managers can create healthier work environments, reduce turnover intentions, and promote sustainable employee well-being.

This study has several methodological and theoretical limitations. First, the analysis is based on the evaluations of only five experts, and this relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of the findings. Future research involving larger expert panels or direct participation of employees from diverse sectors would enhance the reliability and applicability of the proposed model. Additionally, although the methodological framework integrates fuzzy decision-making and machine learning, employing alternative multi-criteria decision-making techniques or different artificial intelligence-based approaches could help validate, compare, and broaden the robustness of the results. From a theoretical standpoint, the study focuses solely on Generations Y and Z, leaving out other cohorts. Extending the model to Generation X or emerging groups such as Generation Alpha would offer a more holistic understanding of intergenerational differences in coping with mobbing. Moreover, the strategies and qualifications identified in this study may be influenced by cultural, institutional, or sectoral contexts. Therefore, cross-cultural comparisons, multi-country applications, or sector-specific analyses represent meaningful avenues for further research. Future studies could also examine hybrid models, longitudinal evaluations, or behavioral validations to deepen insights into how generational characteristics evolve over time. By addressing these limitations and exploring these potential directions, future research can develop a more comprehensive, generalizable, and culturally sensitive understanding of intergenerational coping strategies against mobbing.

Data availability

All datasets used in this research will be shared upon request.

References

Alper Ay, F. Workplace mobbing as a form of serious workplace conflict: A bibliometric analysis of studies from 1990 to 2024. Trauma Violence Abuse 15248380251349772 (2025)

Mohamed, Z., Ismail, M. M. & Abd El-Gawad, A. F. Analysis impact of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on job satisfaction in logistics service sector: An intelligent neutrosophic model. Neutrosophic Syst. Appl. 4, 43–52 (2023).

Atta, M. H. R. et al. Comprehending the disruptive influence of workplace gaslighting behaviours and mobbing on nurses’ career entrenchment: A multi-centre inquiry. J. Adv. Nurs. 81(4), 1815–1828 (2025).

Koinis, A., Papathanasiou, I. V., Moisoglou, I., Kouroutzis, I., Tzenetidis, V., Anagnostopoulou, D. & Malliarou, M. Resilience and mobbing among nurses in emergency departments: A Cross-Sectional Study. In Healthcare 13, 15, 1908. (MDPI, 2025)

Ergen, H., Giliç, F., Yücedağlar, A. & İnandi, Y. Leadership styles and quiet quitting in school context: Unveiling mobbing as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 16, 1538444 (2025).

Shiri, R. et al. The role of continuing professional training or development in maintaining current employment: A systematic review. Healthcare 11(21), 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212900 (2023).

Ogunja, M., Shurong, Z., Ailing, L., Wang, Y. & Anim Mante, D. Analyzing LMX impact on organizational performance on SMEs: An integrated fuzzy reasoning approach. Curr. Psychol. 44(4), 2125–2140 (2025).

Avisar, G., Cohen, T., Tziner, A. & Bar-Mor, H. Abusive behavior of employees against their managers: An explorative study. Front. Psychol. 16, 1576385. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1576385 (2025).

Zou, Y. et al. Exploration of undergraduate nursing students’ perspectives on conducting specialized nursing education during internship: A phenomenological research study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 80, 104103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2024.104103 (2024).

Šagátová, E., Rottková, J., Padyšáková, H., Slezáková, Z. & Paouris, D. Workplace mobbing among nurses in Slovakia: The impact of education, workplace type, and job position. Int. Nurs. Rev. 72(3), e70072 (2025).

Almotairy, M. M., Nahari, A., Moafa, H., Hakamy, E. & Alhamed, A. Development of advanced practice nursing core competencies in Saudi Arabia: A modified Delphi study. Nurse Educ. Today 141, 106315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106315 (2024).

Zhang, X. & Oubibi, M. The impact of generative artificial intelligence on education from the perspective of organizational behavior. TechTrends, 1–12 (2025)

Nelson, S., Ayaz, B., Baumann, A. L. & Dozois, G. A gender-based review of workplace violence amongst the global health workforce—A scoping review of the literature. PLOS Glob. Public Health 4(7), e0003336 (2024).

Ozcan Turkkan, B., Kucukaltan, B., Aydin, E. & Yesilyurt, N. Together at work: employee motivation, cognition and commitment for better management decision-making. Manage. Decis. 1–34 (2025)

Banga, A. et al. ViSHWaS: Violence study of Healthcare Workers and Systems—A global survey. BMJ Glob. Health 8(9), e013101 (2023).

Hodgins, M., Kane, R., Itzkovich, Y. & Fahie, D. Workplace bullying and harassment in higher education institutions: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 21(9), 1173 (2024).

Reato, F. et al. Transversal competencies in operating room nurses: A hierarchical task analysis. Nurs. Rep. 15(6), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15060200 (2025).

Granger, J. et al. Self-assessment competencies of nurse educators in Thailand showed the need to improve training in curricular development and management. Nurse Educ. Today 151, 106704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2025.106704 (2025).

Martínez-Martínez, K., Llorens, S., Cruz-Ortiz, V., Reyes-Luján, J. & Salanova, M. The main predictors of well-being and productivity from a gender perspective. Front. Psychol. 15, 1478826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1478826 (2024).

Runic Ristic, M. et al. Evaluation of leadership styles in multinational corporations using the fuzzy TOPSIS method. Systems 13(8), 636 (2025).

Louw, A., Schuemann, T. L., Smith, K., Benz, L. & Zimney, K. Is there a correlation between length of employment and receiving a post-professional certification or residency in physical therapy? A pilot study. Work Read. Mass. 81(4), 3123–3129. https://doi.org/10.1177/10519815251323990 (2025).

AlSadah, A. T., Aboshaiqah, A. E. & Alanazi, N. H. Perceived value and barriers of nursing specialty certifications among clinical nurses in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 12, 1528856. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1528856 (2025).

Pien, L. C. et al. The relationship between resilience and mental health status among nurses with workplace violence experiences: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 34(1), e13497. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13497 (2025).

Yang, T. A novel framework for TER allocation using multilayer perceptron and intuitionistic fuzzy Z numbers for talent management. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 31491 (2025).

Jang, I., Jang, S. J. & Chang, S. J. Factors influencing hospital nurses’ workplace bullying experiences focusing on meritocracy belief, emotional intelligence, and organizational culture: A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 1637066. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/1637066 (2024).

Chang, Y. P., Lee, D. C., Lee, Y. H. & Chiu, M. H. Nurses’ perceived health and occupational burnout: A focus on sleep quality, workplace violence, and organizational culture. Int. Nurs. Rev. 71(4), 912–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12932 (2024).

Sani, A. I., Magalhães, M., Meneses, R. F. & Barros, C. Workplace bullying and coping strategies among Portuguese healthcare professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 22(4), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040475 (2025).

Yager, R. R. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. In Proc. of the Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting, 57–61 (2013)

Sakrwar, M. S., Ranadive, A. S. & Pamucar, D. A novel Gustafson–Kessel based clustering algorithm using n-Pythagorean fuzzy sets. Syst. Soft Comput. 200345 (2025)

Orlov, A. A., Akhmetshin, T. N., Horvath, D., Marcou, G. & Varnek, A. From high dimensions to human insight: exploring dimensionality reduction for chemical space visualization. Mol. Inf. 44(1), e202400265 (2025).

Aytekin, A., Küçük, H. Ö., Aytekin, M., Simic, V. & Pamucar, D. Evaluation of international market entry strategies for mineral oil companies using a neutrosophic SWARA-CRADIS methodology. Appl. Soft Comput. 174, 112976 (2025).

Dindar Tıraş, S. & Güzel Özbek, A. Generation Y, Generation Z and their perception of work life. In Digital Economy and Green Growth: Opportunities and Challenges for Urban and Regional Ecosystems 175–191. (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024)

Taupe, J., Knapp, V. & Bollin, A. Teachers’ insight: digital threats that imperil children and teenagers. In Open Conference on Computers in Education 51–62 (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024)

Garza-Herrera, R. et al. Relationship of work bullying and burnout among vascular surgeons. JVS Vasc. Insights 2, 100106 (2024).

Damini, S., Blum, C. R., Sumasgutner, P. & Bugnyar, T. When to mob? plasticity of antipredator behavior in common ravens’ families (Corvus corax) across offspring development. Anim. Cogn. 28(1), 55 (2025).

Merkin, R. Gender differences, cancel culture, and shame as resource. In Shame and Gender in Transcultural Contexts: Resourceful Investigations 249–263 (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024)

Pauli, U. & Dudek, A. Young HRM professionals’ perception of supportive work environment–identifying expected changes in employment settings. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 38(8), 71–91 (2025).

Mhaka-Mutepfa, M. & Rampa, S. Workplace bullying and mobbing: Autoethnography and meaning-making in the face of adversity in academia. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 37(1), 1–18 (2024).

Çelik, C., Ata, U., Kamalak, M. & Saka, N. E. Relationship between forensic medicine education, stress factors, and mobbing perception from the perspective of specialists in Turkey’s universities. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 106, 102729 (2024).

Maxcy, B. D. & Nguyễn, T. S. T. District leadership and the politics of incivility: Classroom mobbing and the crisis of carework. In Incivility and Workplace Toxicity in P-12 Schools 185–213 (Routledge, 2025)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept—S.Y., S.T.E.; Design—S.E., S.Y.; Supervision—H.D.; Materials—S.T.E.; Data Collection and/or Processing—S.T.E.; Analysis and/or Interpretation—S.E.: Literature Review—S.T.E.; Writing—S.E., S.Y.,S.T.E., H.D.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Topaloğlu Eti, S., Yüksel, S., Eti, S. et al. Identifying effective coping strategies against mobbing for Generations Y and Z using a Pythagorean fuzzy decision support mechanism. Sci Rep 16, 3566 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33594-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33594-3