Abstract

This study aimed to compare the short-term effects of multimodal physiotherapy (MPT) with intra-articular corticosteroid injection (IAI) on pain, disability, effectiveness of treatment, and passive range of motion in patients with frozen shoulder. Randomized Controlled Trial. University Hospital. Patients diagnosed with frozen shoulder with at least 50% passive range of motion (PROM) limitation. Forty-eight patients were allocated into two groups: Group A: MPT and Group B: IAI. After allocation, all patients received a prescription of a comprehensive home exercise pamphlet (HEP) and were instructed to perform them for six weeks. Pain ((visual analogue scale (VAS), shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI)), disability (SPADI), and PROM for abduction, external rotation, and scaption were recorded at the baseline and 6 weeks after randomization. The effectiveness of treatment (global rating scale (GRC)) was recorded 6 weeks after randomization. Pain (VAS) and (SPADI), disability (SPADI), and passive range of motion (PROM) significantly improved after both treatments (p < 001). The effect size of MPT was larger than IAI for all outcomes. Notably, significant positive differences were observed in internal rotation PROM (p = 0.036, effect size (ES) = 0.627) and the disability section of the GRC scale (p = 0.005), indicating that MPT was more effective. However, in VAS, SPADI (total), GRC (pain), external rotation, abduction, and scaption PROM, the difference between the treatment groups was not statistically significant. MPT and IAI are both effective short-term interventions. The stronger effect and specific superior outcomes of MPT are promising, but the limited sample size precludes definitive conclusions regarding superiority. Larger trials are warranted to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frozen shoulder is one of the most common pathologies in the shoulder that can affect up to 5% of the total general population and is associated with obesity and diabetes1. The etiologic factors behind this pathology remain unclear but it has been associated with shoulder pain, fibrosis, and stiffness of the anterior portion of the glenohumeral articular capsule2. The functional limitations of frozen shoulder can present themselves in various ways, such as sleep disturbances caused by pain, severe restrictions in the range of motion of the upper extremity, and reduced participation in social activities3. Despite the benign and partially self-limiting nature of frozen shoulder, it’s widely agreed upon it should be treated nonetheless since the complications might not resolve and may persist in the long term4.

There are various evidence-based approaches for managing frozen shoulder. A cornerstone of conservative management is physiotherapy (PT), which typically encompasses a multi-modal strategy. This includes supervised therapeutic exercises aimed at restoring range of motion and strength, joint mobilizations to address capsular restrictions, and electrotherapeutic modalities for pain control and tissue healing5,6. Moreover, corticosteroids such as prednisolone and triamcinolone can be delivered either intra-articularly or via subacromial approach7. Based on a recent systematic review, intra-articular injection (IAI) produces quicker and more significant effects on pain when compared to subacromial (SA) injection8. Various studies have supported IA corticosteroid injection as an effective treatment for frozen shoulder for pain and passive range of motion (PROM) improvement in the short-term6,7. When comparing the effect of PT and IA corticosteroid injection, multiple systematic reviews are supportive of the superiority of IA injection while PT could not reach the pain relief effects of placebo treatment, making it the worst treatment for pain management for frozen shoulder in the short term4,6,7,9. Despite the effectiveness of injection, this approach is plagued with side effects such as tendon rupture following heavy lifting, soft tissue or intra-articular infection, muscular atrophy, severe allergic reaction, and complications (i.e., fear of injection, dizziness, and light-headedness after injection, etc.) while PT suffers from none of the aforementioned side effects and could be considered as an alternative treatment if prescribed appropriately10.

Other approaches such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques, are used for mobility improvements, pain reduction, and articular movement coordination. Other PNF techniques such as hold-relax, while relying on principles such as reciprocal innervation and post-isometric relaxation, can improve mobility and musculoskeletal performance. A recent systematic review confirmed the superiority of PNF techniques when compared with traditional physiotherapy, especially when hold-relax technique and the D2 flexion pattern were included in the treatment11. When considering the natural history of this pathology, glenohumeral mobilization techniques can be effective in reducing pain and improving the range of motion. Another recent systematic review concluded that mobilization techniques, when accompanied with Kaltenborn’s distraction techniques, are superior to conventional physiotherapy4. Various promising treatments in PT were examined to assess their effectiveness in patients diagnosed with frozen shoulder. Another PT element is Low level laser therapy (LLLT), which is a non-invasive approach that can be used in a variety of musculoskeletal disorders. In a study that used LLLT for treating patients diagnosed with frozen shoulder, significant differences in pain reduction were demonstrated when compared to placebo LLLT12.

Various studies compared PT with intra-articular injection (IAI) in patients with frozen shoulder. Several of the studies that used PNF and mobilization techniques showed no significant difference in pain and range of motion in short term follow up (6 weeks)13. Although glenohumeral mobilizations and PNF techniques are effective, solitary utilization of either does not seem to result in a significant difference in pain and mobility compared to IAI. Additionally, LLLT did not show any effect on the shoulder range of motion12. When considering the superior effects of the PNF and glenohumeral mobilization techniques on shoulder mobility and pain relief and the superior effects of LLLT on pain, there is a compelling chance that when relying on the new evidence and recent protocols, the utilization of a multimodal PT (MPT) would result in a safer, quicker, and less invasive treatment effect when compared to IA injection6,11,14. To the best knowledge of the authors, no study has evaluated the effect of MPT and compared them with IA injection. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the short-term effect of corticosteroid IAI with MPT on pain, disability, effectiveness of treatment, and PROM in patients diagnosed with frozen shoulder. Our explicit hypothesis was that IAI and MPT would have similar effects on pain and disability. However, we anticipated that MPT would lead to greater improvement in passive range of motion (PROM) compared to IAI.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present study was a parallel group, two-arm randomized clinical trial. Blinded assessments were performed both on data analysis and patient evaluations. Ethics approval was obtained from the regional research ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.REC.1400.345). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The trial was registered in the Iranian registry of clinical trials at 2022-03-21 (IRCT20161221031506N8). The study began on March 22, 2022.

Participants

The patients with frozen shoulder were recruited through flyers, announcements, and referral from department of orthopaedics. The study was conducted in Ghaem university hospital, Mashhad, Iran. Patients with frozen shoulder were randomly assigned into two groups of MPT (n = 24) and IAI (n = 24) after the first evaluation through selecting odd and even cards in sealed envelopes for concealed allocation. The assessor was not involved in the treatment sessions and the assessor was blinded to group allocation during data collection. The frozen shoulder patients were included if they were; (1) 18 years and older13; (2) had more than 50% limitation in both passive and active glenohumeral abduction and external rotation (confirmed by a digital goniometer)15; (3) had shoulder pain for at least 4 weeks16 (4) had no history of coagulative diseases and15(5) had sleep disturbances due to pain and were incapable of sleeping on the affected side due to their shoulder pain17. At baseline, none of the participants reported ongoing anti-inflammatory treatment, ensuring comparability between groups.

Patients were excluded if presented with any of the following criteria: (1) history of severe trauma to the shoulder that resulted in shoulder dislocations and/or surgeries13; (2) history of cervical radiculopathy that could be provoked by active neck pain and spurling test15; (3) history of full-thickness complete rotator cuff tear that resulted in a positive drop-arm sign13,15; (4) severe infection (local or systemic)12; (5) history of shoulder fracture and osteoarthritis17; (6) presence of malignancy in shoulder14; (7) radiotherapy within the last 4 to 6 months in the shoulder14 and (8) any contraindication regarding injection (allergic to drug, previous injection, etc.)18,19.

Dependent variables measured for each patient were: pain (visual analogue scale (VAS) and (shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI)); function (SPADI); PROM in four planes (external rotation, internal rotation, abduction, and scaption), and effectiveness of treatment (global rating of change scale (GRC)). The outcome measurements were selected based on previous studies that addressed reliability and validity of each measure considered. Pain measured using the SPADI questionnaire was the primary outcome measure, whereas function, PROM, and effectiveness of treatment were secondary outcome measurements. The questionnaires and PROM were evaluated at baseline and 6 weeks after randomization.

This clinical study was conducted at a primary care PT clinic that treats a variety of musculoskeletal disorders. Patients in the PT group were treated by an experienced physiotherapist who specialized in shoulder orthopaedical pathologies. Before assessing the eligibility criteria, a clinical evaluation of the referred patients was performed by an orthopaedic surgeon specializing in arthroscopic shoulder surgery. The independent variables for the present study were time with 2 levels (i.e., before treatment, 6 weeks after randomization), and group with two levels (i.e., MPT and IAI).

Patients with shoulder pathologies, referred from various sources to an orthopaedic shoulder specialist (***), were clinically examined and then determined whether they were eligible to be assessed for the inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e., whether they were diagnosed with frozen shoulder and no other major pathologies). After this process, if a patient was deemed suitable to enter the study, a blinded examiner then would explain the nature of the study to the patient. Subsequently, all included patients would sign the ethics-approved informed consent form. Patients’ baseline assessment (demographic and baseline outcomes) was obtained and then, using stratified randomization for diabetic patients with two indexes, they were allocated to either PT or IAI groups. All the allocated patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm absence of the aforementioned pathologies and other possible sources mimicking frozen shoulder.

Intervention

Intra-articular injection

Patients in the IAI group received their treatment via landmark-guided posterior approach. Based on recent trials and systematic reviews, an ultrasonic guided injection does not offer any significant clinical advantage when compared to the blinded approach in patients with frozen shoulder20. A combination of 40 milligrams of triamcinolone (1 milliliter) and 9 milliliters of 2% lidocaine was injected into the glenohumeral joint by a guided posterior approach21. Injections were administered by posterior approach while the patient was seated, the affected arm supported by a pillow, and slightly internally rotated. The physician’s index finger was placed on the coracoid process and the thumb was placed on the corner of the scapula between the spine and the acromion. The needle was then inserted 1 cm below the thumb and pointed toward the coracoid process. Equipped with a 21-gauge needle, the orthopedist used a 10-milliliter syringe to deliver the required dosage. Patients then received a comprehensive home exercise program pamphlet consisting of pendulum exercises (2 sets of 8 repetitions, twice daily), active-assisted range of motion exercises (2 sets of 8 repetitions, twice daily), and stretching to tolerance (2 sets of 8 repetitions, twice daily). Progression was individualized based on patient tolerance, with weekly reassessment to increase the available range of motion at home if pain remained below 5/10 on the VAS. Adherence to the home exercise program was monitored primarily through weekly patient self-reports. We acknowledge that this method is subjective and has inherent limitations, such as potential recall bias and over reporting. It was logistically the most feasible method for our study design.

Multimodal physiotherapy

In the MPT group, there were a total of ten sessions, three sessions weekly, each lasting an hour. Patients were given the same home exercise pamphlet as the injection group. The interventions were introduced in a particular sequence, to augment their effect based on clinical evidence available. At first, hot pack application, which covered the entire anterior-posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint, was applied while the patient’s upper extremity that was put in a comfortable position to avoid any discomfort with static positioning for 15 min. Then, Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) (class 3B Endolaser 422, Enraf-Nonius (Rotterdam, Netherlands) was applied at the most painful points directed at the capsule of the glenohumeral joint (eight points) which was indicated by the patient and confirmed with palpation. The points were delineated with a permanent marker on the first session. To minimize backscattering and refraction of the laser beam, we disinfected the target area with 95% alcohol before each application. The probe was then placed perpendicular to the skin to avoid wasting energy due to beam divergence. The laser (pulsed mode) with a wavelength of 905 nm, a power of 60 milliwatts, a spot size of 1 cm2, a frequency of 6000 Hz, an energy density of 1.8 J/cm2, and a 30 s process per each point for a total dose of 14.4 Joules per session was administered. 12. Afterwards, grade 2 glenohumeral joint mobilizations, with emphasis on the improvement of abduction and external rotation, were applied and accompanied with grade 1 Kaltenborn distraction technique5,9. The techniques included distraction, posterior, inferior, and lateral glide in supine and anterior glide in prone position, each performed for 5–10 min. The joint was reassessed each session to follow Maitland’s principles. Finally, the D2 flexion pattern of the involved extremity (flexion, abduction, and external rotation in the glenohumeral joint) accompanied by hold relax technique, performed with a 10 s contraction of the antagonist pattern muscles, were administered 5 times per each session11.

Outcome measurement

Outcomes of this trial included pain intensity, disability, effectiveness of treatment, and PROM in 4 movements at the glenohumeral joint (external rotation, internal rotation, abduction, and scaption). These outcomes were measured in a random order using a dice to avoid learning/fatigue effects. The primary outcome of this trial was pain that was measured via SPADI. The secondary outcomes were general pain, measured via VAS, effectiveness of treatment measured via Global rate of change (GRC) scale, and PROM measured via a digital goniometer.

Pain (VAS)

Pain intensity was measured via VAS which includes a 100 mm line on which 0 indicates no pain and 100 indicates the worst pain imaginable. Patients were asked to draw a perpendicular line on this line via a ruler to indicate their pain level. A minimum of 20 mm of change is required for the minimally clinically important difference (MCID)22.

Pain and disability (SPADI)

Pain intensity and disability were measured via SPADI questionnaire. This index is a self-administered tool that ranges from 0 to 100 (No disability to completely disabled) and includes 13 items divided into two subscales: 5 items on pain and 8 items on disability22. The reliability, validity and responsiveness of the Persian version of this index have been validated to use in patients with shoulder pathologies (ICC = 0.89)23. Results from previous studies have shown that the SPADI questionnaire has adequate responsiveness in patients with shoulder disorders with a change of 19.7 points considered as MCID24.

Effectiveness of treatment (GRC)

The effectiveness of treatment was assessed via GRC. The reliability of the GRC was verified for use in clinical trials (ICC = 0.90). GRC is an 11-point scale that consists of -5 (much worse), 0 (no change), to + 5 (much better). Each increase or decrease of the score represented the patients’ satisfaction change on the scale. GRC scales request a person to assess the effectiveness of the treatment using this scale25.

Passive range of motion (PROM)

PROM of the glenohumeral joint was measured in 4 physiological glenohumeral movements (external rotation, internal rotation, abduction, and scaption). Shoulder abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation were measured in supine position according to measurement guidelines. Scaption was measured in sitting, with shoulder in scapular plane. For abduction, stationary arm of the goniometer was parallel to sternum and moving arm of the goniometer was parallel to anterior midline of humorous toward medial humeral epicondyle. For external and internal rotation, stationary arm of the goniometer was perpendicular to floor and moving arm of the goniometer was ulnar border of forearm toward ulnar styloid process. For scaption, axis was midpoint of lateral aspect of acromion process and moving arm of the goniometer lateral midline of humorous toward lateral humeral epicondyle. It has been proposed that a change of 10 degrees can be considered the MCID for shoulder PROMs24.

Sample size calculation

For sample size calculation, based on this formula, \(n=\frac{{({Z_{1 - \frac{\alpha }{2}}}+{Z_{1 - \beta }})(S_{1}^{2}+S_{2}^{2})}}{{({X_1} - {X_2})}}\) the means and standard deviations of SPADI (pain) was applied based on a prior study. while considering a 10% drop rate and with α: 0.05, Confidence interval: 0.95, β: 0.20, and power: 0.80, 24 subjects were be allocated to each group (48 in total)26.

Randomization and blinding

After the baseline assessment, another practitioner allocated the patients randomly to into the intervention groups. Using stratified randomization, two indexes of numbers 1 and 2, which belonged to physiotherapy (number 1) and IAI (number 2), respectively, were generated from “sealedenvelope.com” by an independent individual and put into opaque, sealed envelopes to ensure concealed allocation. One group of envelopes belonged to diabetic patients and the other group, to non-diabetic patients. Patients were randomly allocated into two groups: (1) MPT, (10 sessions in total, 3 sessions weekly) (n = 24); (2) IAI (n = 24). Statistical analyser was blinded via codes allocated to each group participant and was unaware of the interventions administered to each group. Both approaches are routinely prescribed and used in the treatment of frozen shoulder, so blinding the patient does not violate the fundamental ethical rights of the participants. Each intervention group received treatment at two separate treatment centres to remove bias effects due to different preferential treatment perceptions.

Statistical analysis

Normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which is more appropriate for small sample sizes. Independent t-test was utilized to assess the background quantitative variables between groups. Chi-square test was utilized to assess the background qualitative variables between groups. Paired T-test was utilized to compare before-after outcomes for each group. For analysing the effectiveness of treatment at 6 weeks after randomization, Mann-Whitney test was utilized. Independent t-test was utilized to analyse the quantitative dependent variables before randomization and 6 weeks after randomization. Effect sizes were determined by utilizing the Cohen’s d formula for paired t-test and independent t-test amount of statistical significance was p < 0.05. MCID analysis was performed for all variables29. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 27.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

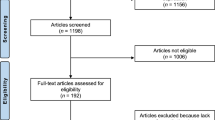

In this trial, 115 patients were assessed for their eligibility to enter the study. From this population, out of 67 excluded patients, 41 patients did not meet the study criteria and 26 patients declined to participate (Fig. 1). After baseline assessment, 24 patients were allocated to each of the IAI group (7 males, 17 females, aged: 56.21 ± 6.345) and MPT group (6 males, 18 females, aged: 57.79 ± 9.523). All background variables (qualitative and quantitative) were similar between groups with normal data distribution and no adverse effects reported during the trial period or at the second assessment (Table 1).

Significant statistical differences were found for all variables for both groups when comparing pre-treatment with post-treatment. The IAI group significantly improved pain (VAS p < 0.001, ES = 1.379, SPADI p < 0.001, ES = 1.695), disability (SPADI p < 0.001, ES = 1.491), and all PROMs (external rotation p < 0.001, ES = 1.650, internal rotation p < 0.001, ES = 0.744, abduction p < 0.001, ES = 1.262, and scaption p < 0.001, ES = 1.555). In the IAI group, out of 24 patients, MCID for VAS was achieved for 15 patients and 17 patients achieved MCID for SPADI. For PROMs, 20 patients for abduction, 20 for external rotation, 13 patients for internal rotation, and 21 for scaption achieved the MCID (Table 2; Fig. 2).

The MPT group significantly improved pain (VAS p < 0.001, ES = 2.012, SPADI p < 0.001, ES = 1.977), disability (SPADI p < 0.001, ES = 2.243), and all PROMs (external rotation p < 0.001, ES = 1.662, internal rotation p < 0.001, ES = 0.953, abduction p < 0.001, ES = 1.850, and scaption p < 0.001, ES = 2.663). In the MPT group, out of 24 patients, MCID for VAS was achieved for 22 patients and 21 patients achieved MCID for SPADI. For PROMs, 23 patients for abduction, 22 for external rotation, 14 patients for internal rotation, and 24 for scaption achieved the MCID (Table 2; Fig. 2).

No statistically significant differences were found before randomization for the baseline assessment of pain (VAS p = 0.898, SPADI p = 0.957), disability (SPADI p = 0.654), and all PROMs (external rotation p = 0.469, internal rotation p = 0.292, abduction p = 0.842, and scaption p = 0.486) between groups. This trend was repeated with independent T-test for comparing the dependent variables at 6 weeks after randomization, meaning that no significant differences were observed between groups except for internal rotation PROM where PT showed to be more effective (p = 0.036) (Table 3).

There is no statistically significant difference for GRC (pain) between groups, meaning that both groups showed similar effects (p = 0.563). MPT showed to be more effective on GRC (disability) when compared to IAI (p = 0.005) (Table 4).

Discussion

The purpose of this trial was to analyse the effect of PT in comparison to IAI on pain, disability, and effectiveness of treatment in patients with frozen shoulder. The results indicate that both treatments were effective on improving pain and disability, although both groups showed similar trends in reducing pain, improving disability, and restoring PROM, when comparing each group before allocation and 6 weeks after randomization, the effect size of the MPT group was larger than the IAI group in all outcomes, meaning that MPT was clinically more effective in reducing pain, improving disability, and restoring PROM. When assessing the effect of MPT and IAI on the effectiveness of treatment (pain), there was no significant difference between groups, but this difference became significant for the effectiveness of treatment (disability) as MPT showed to be more effective. These findings support multimodal PT as an effective short-term option comparable to IAI, rather than indicating overall superiority. When situating our findings within prior evidence favouring IAI for short-term pain relief, our data suggest multimodal PT can achieve comparable short-term improvements under a structured protocol with sequencing (heat, LLLT, mobilizations, PNF, and HEP). Given heterogeneity in PT content across trials, our results should be interpreted as protocol-specific rather than generalizable to all forms of “physiotherapy.” Recent systematic review long-established the superiority of IAI for pain reduction in short-term. In a systematic review, it was found that corticosteroid treatment provided significant benefits in terms of pain relief and improved function in the short-term when compared to PT6. However, PT ranked last in the network analysis for short-term pain management between placebo, IAI, subacromial corticosteroid, and arthrographic distention6. The reason for this result is most likely due to the large heterogeneity of the studies included and the general disagreement on the best treatment for frozen shoulder as many included trials used different IAI approaches and PT components27. Nonetheless, IAI showed to be more effective on pain when compared to PT. In another systematic review by Wang et al., intra-articular corticosteroid injections were more effective in pain relief and restoring PROM in the short term which reasserts the efficiency of injection. However, our findings suggest that a MPT can be equally effective or even superior to IAI in improving pain and disability, particularly for internal rotation PROM and treatment effectiveness in patients with Frozen shoulder. This may be due to the unique sequencing effect of applying heat prior to mobilizations and utilizing PNF techniques, such as hold-relax, to increase PROM and reduce pain. In a study conducted by Stergioulas, LLLT was found to significantly reduce pain by providing an analgesic effect, which in turn can produce a more positive outlook towards the rehabilitation process. This facilitates shoulder relaxation and prepares the patient to be more tolerant towards manual therapy, which is essential for successful treatment. Since the shoulder capsule is located up to 2 cm beneath the skin as confirmed by MRI measurements the energy from LLLT primarily affects the shoulder musculature, and when considering the results of this trial, it is noteworthy to emphasize the potential benefits of focusing on the shoulder musculature in a pathology most recognized for capsular inflammation12. In a trial conducted by Ryans et al., MPT consisted of eight sessions over a period of 4 weeks which according to the author was based on experts’ opinion at the time. It included PNF, Maitland mobilizations, interferential modality and exercise therapy. IAI were given by a combined lateral and anterior approach to the shoulder. The authors then concluded that corticosteroid injection is effective for improving shoulder-related disability at 6 weeks following treatment while PT showed no such effect. This result corresponds with the results of our trial for the effectiveness of IAI while in our trial, MPT was as effective as IAI in this trial for pain and disability13. An interesting notion is the fact that our study and Ryans et al. used PNF and mobilizations, but when considering the augmentation effect of sequencing each treatment and clarifying the dosage, in our trial MPT proved to be as effective as the IAI on pain and disability while Ryans et al. observed no such effect. In another trial conducted by Mobini et al., PT included transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, active ROM exercises, and ice application for 10 sessions. Corticosteroid injections included the injection of 60 milligrams triamcinolone and 3 cc lidocaine with posterior approach in glenohumeral joint and 20 milligrams triamcinolone and 1.5 cc lidocaine in subacromial space. The authors concluded that IAI was more effective than PT in reducing pain and improving function9. While this trial favoured IAI, the current trial, while utilizing the MPT with the augmentation effect of sequencing its components, reached the same effectiveness level on pain and disability as IAI. Another tangible notion is the general administration of physiotherapy without mentioning dosages or techniques by Mobini et al. and referring to PT as “modalities”26.

Our research was focused on redefining PT and utilizing all available evidence-based treatments and therapies. As a result, MPT has been found to be equally effective as IAI, although some studies have reported similar results using different PT and IAI approaches. In a study by Dacre et al., PT was administered using the method deemed most appropriate by the therapist, which included mobilizations with no significant differences between the groups16. Another study by Arslan compared IAI of methylprednisolone with PT at weeks 2 and 12. The PT consisted of hot packs applied for 20 min, ultrasound at 3.5 W/cm2 for 5 min, passive stretching of the glenohumeral joint, Codman exercises, and wall climb. There was no significant difference observed between the groups15. It appears that different dosages of IAI, unspecified home exercise programs, and a different approach to PT can potentially confound the outcomes, leaving the practitioner with more questions than answers27. While considering the ambiguous nature of frozen shoulder, the heterogeneity of the trials presents us with a conundrum. Each trial used a specific dosage for IAI and had a certain definition for PT. Ryans et al. tried to justify the administered PT with relying on the knowledge void statement, arguing that many approaches to PT remain untested13. Carette et al. used two different physiotherapy approaches to “Reflect current clinical practice”28. The same rationale was mentioned by Dacre et al.16. This evidently demonstrates that when it comes to Frozen shoulder, there is no consensus for the best and most effective combination for PT. Clearly the approach to prescribing MPT needs to be just as clear to IAI to prevent further equivocality.

The strengths of this trial include multidisciplinary approach to PT, sequencing each component to maximize its efficiency, and relying on the latest systematic reviews to bring together the PT components in one its most effective combinations.

Limitation

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, although a HEP was prescribed, adherence was not monitored, which may have influenced individual outcomes. Second, due to practical clinical constraints, the prescribed supervised exercises could not be fully implemented in their intended sequence during treatment sessions. Third, the short-term follow-up period of 6 weeks limits insight into whether the observed improvements are sustained over time; longer-term assessment is needed to evaluate treatment durability. Finally, the relatively high number of participant exclusions may affect the generalizability of the findings to the broader population with frozen shoulder.

Based on these findings and limitations, future research is recommended to investigate the optimal sequencing and combined effects of specific manual therapy techniques, exercise prescriptions, and electrotherapy modalities within a multimodal physiotherapy framework. Additionally, studies comparing alternative injection approaches—such as subacromial injection, which may be less resource-intensive than intra-articular injection—and their integration with HEP and MPT are warranted.

Conclusion

This randomized trial demonstrates that both MPT and IAI, combined with home exercise, are effective short-term treatments for frozen shoulder, significantly improving pain, disability, and range of motion. MPT showed a stronger treatment effect, with statistically superior outcomes in patient-reported function and restoration of internal rotation. However, for most primary outcomes, the between-group differences did not reach statistical significance. The study’s sample size limits the precision of these comparisons and the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, while MPT appears to be a highly effective and possibly superior intervention, larger trials are needed to confirm its comparative advantage definitively.

Clinical message

-

Utilization of multimodal physiotherapy (MPT) would result in a safer, quicker, and less invasive treatment effect.

-

MPT can be a suitable alternative for reducing pain, and disability, as well as restoring passive range of motion.

-

Intra-articular injection can result in the same effect as MPT for improving pain and disability.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns, licensing restrictions, and ethical approvals. However, all relevant data are included within this published article and its Supplementary Information files. Additional materials may be obtained from the corresponding author, Dr. Salman Nazary-Moghadam (PT, PhD), upon reasonable request at Nazaryms@mums.ac.ir.

References

Manske, R. C. & Prohaska, D. Diagnosis and management of adhesive capsulitis. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 1, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-008-9031-6 (2008).

Andronic, O., Ernstbrunner, L., Jüngel, A., Wieser, K. & Bouaicha, S. Biomarkers associated with idiopathic frozen shoulder: a systematic review. Connect. Tissue Res. 61, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/03008207.2019.1648445 (2020).

Dias, R., Cutts, S. & Massoud, S. Frozen shoulder. Bmj 331, 1453–1456. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7530.1453 (2005).

Nakandala, P., Nanayakkara, I., Wadugodapitiya, S. & Gawarammana, I. The efficacy of physiotherapy interventions in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 34, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.3233/bmr-200186 (2021).

Wong, C. K. et al. Natural history of frozen shoulder: fact or fiction? A systematic review. Physiotherapy 103, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2016.05.009 (2017).

Challoumas, D., Biddle, M., McLean, M. & Millar, N. L. Comparison of treatments for frozen shoulder: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e2029581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29581 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Effectiveness of corticosteroid injections in adhesive capsulitis of shoulder: A meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim). 96(28), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000007529 (2017).

Chen, R., Jiang, C. & Huang, G. Comparison of intra-articular and subacromial corticosteroid injection in frozen shoulder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Surg. 68, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.06.008 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Comparative efficacy and Patient-Specific moderating factors of nonsurgical treatment strategies for frozen shoulder: an updated systematic review and network Meta-analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 49, 1669–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520956293 (2021).

Coombes, B. K., Bisset, L. & Vicenzino, B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 376, 1751–1767. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61160-9 (2010).

Tedla, J. S. & Sangadala, D. R. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques in adhesive capsulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 19, 482–491 (2019).

Stergioulas, A. Low-power laser treatment in patients with frozen shoulder: preliminary results. Photomed. Laser Surg. 26, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2007.2138 (2008).

Ryans, I., Montgomery, A., Galway, R., Kernohan, W. G. & McKane, R. A randomized controlled trial of intra-articular triamcinolone and/or physiotherapy in shoulder capsulitis. Rheumatol. (Oxford). 44, 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh535 (2005).

Cameron, M. H. Physical Agents in Rehabilitation: An Evidence-Based Approach to Practice 5th edn, Vol. 1 (2020).

Arslan, S. & Celiker, R. Comparison of the efficacy of local corticosteroid injection and physical therapy for the treatment of adhesive capsulitis. Rheumatol. Int. 21, 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002960100127 (2001).

Dacre, J. E., Beeney, N. & Scott, D. L. Injections and physiotherapy for the painful stiff shoulder. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 48, 322–325. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.48.4.322 (1989).

Binder, A. I., Bulgen, D. Y., Hazleman, B. L. & Roberts, S. Frozen shoulder: a long-term prospective study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 43, 361–364. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.43.3.361 (1984).

Calis, M. et al. Is intraarticular sodium hyaluronate injection an alternative treatment in patients with adhesive capsulitis? Rheumatol. Int. 26, 536–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-005-0022-2 (2006).

Gottlieb, N. L. & Riskin, W. G. Complications of local corticosteroid injections. Jama 243, 1547–1548 (1980).

Cho, C. H., Min, B. W., Bae, K. C., Lee, K. J. & Kim, D. H. A prospective double-blind randomized trial on ultrasound-guided versus blind intra-articular corticosteroid injections for primary frozen shoulder. Bone Joint J. 103-b, 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.103b2.Bjj-2020-0755.R1 (2021).

Bal, A. et al. Effectiveness of corticosteroid injection in adhesive capsulitis. Clin. Rehabil. 22, 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508086179 (2008).

Nazary-Moghadam, S. et al. Comparative effect of triamcinolone/lidocaine ultrasonophoresis and injection on pain, disability, quality of life in patients with acute rotator cuff related shoulder pain: a double blinded randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2024.2316307 (2024).

Ebrahimzadeh, M. H. et al. Cross-cultural adaptation, validation, and reliability testing of the shoulder pain and disability index in the Persian population with shoulder problems. Int. J. Rehabilitation Res. Int. Z. Fur Rehabilitationsforschung Revue Int. De Recherches De Readaptation. 38, 84–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0000000000000088 (2015).

Simovitch, R., Flurin, P. H., Wright, T., Zuckerman, J. D. & Roche, C. P. Quantifying success after total shoulder arthroplasty: the minimal clinically important difference. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 27, 298–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2017.09.013 (2018).

Kamper, S. J., Maher, C. G. & Mackay, G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J. Man. Manip Ther. 17, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1179/jmt.2009.17.3.163 (2009).

Mobini, M., Zahra, K., Adeleh, B. & Morteza, Y. Comparison of corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, and combination therapy in treatment of frozen shoulder. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 28, 448–651 (2012).

de Sire, A. et al. Non-Surgical and rehabilitative interventions in patients with frozen shoulder: umbrella review of systematic reviews. J. Pain Res. 15, 2449–2464. https://doi.org/10.2147/jpr.S371513 (2022).

Carette, S. et al. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10954 (2003).

Zeinalzadeh, A. et al. Intra- and Inter-Session Reliability of Methods for Measuring Reaction Time in Participants with and without Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Arch. Bone Jt Surg. 9(1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.22038/abjs.2020.46213.2270 (2021).

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Mashhad University of Medical Science, Mashhad, Iran (Grant Number: 4001264). This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mohammad Ali Zare (PT, MSc): Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Project administration; Visualization; Writing—original draft (clinical procedures).Mohammad Hosein Ebrahimzadeh (MD): Investigation; Resources (intra-articular injections); Validation; Writing—review & editing.Ali Moradi (MD): Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Supervision; Writing—review & editing.Afsaneh Zeinalzadeh (PT, PhD): Formal analysis; Methodology (statistical); Data curation; Visualization; Supervision; Writing—review & editing.Salman Nazary-Moghadam (PT, PhD): Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Project administration; Writing—original draft (introduction/discussion); Writing—review & editing; Guarantor; Corresponding author.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zare, M.A., Ebrahimzadeh, M.H., Moradi, A. et al. Clinical outcomes of intra-articular corticosteroid injection vs. multimodal physiotherapy in patients with frozen shoulder in short term: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 16, 3607 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33598-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33598-z