Abstract

This study aims to address the critical challenge of the formation of acid mine drainage (AMD) in coal mining areas by systematically investigating groundwater recharge pathways and developing targeted source reduction strategies. A range of methods were employed, including field investigations, surveying and mapping, in situ measurements of hydraulically conductive fracture zones (HCFZs), spatial and hydrological analyses, yielding multi-source data. Based on the comprehensive dataset obtained, a novel methodology was developed to identify surface water infiltration pathways. Downhole video monitoring results indicate that the advancements in coal mining technology have gradually increased the heights of HCFZs. Furthermore, mining-induced fissures in hard rock layers were found to extend further vertically and form dense, interconnected networks, leading to higher permeability coefficients compared to those in weak rock layers. Surface water preferentially infiltrates at intersections of HCFZs, coal seams, and topographic features. Notably, groundwater recharge in the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam primarily occurs along the paleo-valley system where natural drainage aligns with mining-induced fissures. This study provides an example of source reduction treatment for AMD in mining areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Based on the ecological protection and high-quality development strategies for the Yellow River basin, China has recently implemented a series of projects to enhance the ecological integrity in the basin. The AMD treatment in abandoned mines is a critical component of these efforts. Unlike conventional post-pollution remediation, this study focuses on AMD formation at its source, highlighting geological prevention and elucidating the mechanisms linking pollution and the mining process. Current AMD treatment research and applications focus primarily on pollutant treatment through various methodologies. For instance, oxygen barriers1,2,3, surface passivation4,5, and bactericides6,7 are employed to prevent AMD formation. Agents such as crustaceans and limestone are used to neutralize acidic water bodies8,9. In addition, microorganisms10,11, permeable reactive barriers12,13, and phytoremediation technology14,15 are utilized to reduce water acidity and remove metal ions among others. Researchers have explored to transform AMD into resources16,17,18. However, these methods frequently overlook the role of water circulation in AMD formation, leading to a lack of rational geological pollution control plans.

Since the 1980s, the rapid expansion of China’s mining industry has driven systematic investigations into the overburden deformation and failure mechanisms and the propagation of mining-induced fissures. The establishment of a conceptual model incorporating caving zones, HCFZs and bending zones (also referred to as the three-zone model) marks a landmark achievement (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). Empirical formulas for calculating the heights of caving zones and HCFZs were derived based on a large amount of observational data19. In addition, the masonry beam model for the overburden structure, the critical layer theory for rock control20,21, and the transmitted rock beam theory22 have lain the foundation for research on the structure, dynamics of the overburden and mining pressure distribution in coal mines of China. Subsequently, researchers conducted detailed studies on the overburden failure under specific conditions23,24,25. They evaluated the applicability of relevant empirical formulas26,27, assessed the overburden permeability28,29, examined the mechanisms driving surface runoff in goaves30,31,32, and simulated the hydrogeological processes in mining areas33,34. Although a robust theoretical framework for mining geomechanics has been developed, quantifying the impacts of mining on surface hydrology remains a challenge. To bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and ecological restoration practices, it is necessary to intensify field studies on the runoff, convergence and infiltration processes in mining areas.

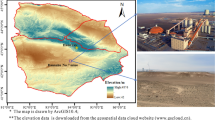

The Modi Valley of the Yellow River system hosts two minable coal seams in the loess hilly landform. Over a prolonged period, local residents and mining enterprises have mined these coal seams using methods such as opencast mining, excavation, blasting, conventionally mechanized mining and fully mechanized mining. These activities have induced severe surface deformations and altered the hydrological cycle. Consequently, surface water infiltrates into goaves rather than discharging naturally, leading to the formation of AMD. The contaminated water emerges as overflow springs from coal seams or mine entrances on the left bank of the lower Modi Valley. These overflow springs exhibit pH values ranging from 2.5 to 3, with SO₄2⁻, Fe2⁺, Fe3⁺, and Mn2⁺ concentrations substantially exceeding regulatory limits, and a total average discharge rate of approximately 15 L/s (see Supplementary Figs. S2–S7 online). These anthropogenic modifications have resulted in significant ecological contamination, necessitating the need for urgent remediation (Fig. 1).

Location of the study area. (a) Map of China. (b) Map of coalfields in Shanxi Province. (c) Map of the Modi Valley. Note: In Fig. 1c, AMD overflow springs (AMD 1 ~ 4), as well as mining-induced fissures in rock outcrops, surface fissures, and land subsidence, were identified by field investigation. The outcrops of the Nos. 2 and 10 coal seams, the pinch-out and erosional zones of the No. 10 coal seam, stratigraphic attitudes, and normal faults in this figure were determined through data collection. This figure is prepared using ArcGIS ver.10.8 (https://www.esri.com/) and the WGS84 coordinate system.

This study investigated groundwater recharge mechanisms by systematically analyzing mining-induced HCFZs and their spatial intersections with surface features. Accordingly, it identified critical infiltration pathways connecting the surface water system to subsurface workings. The findings will offer fundamental insights for developing targeted AMD mitigation strategies in mining areas.

Overview of the study area

Landforms and coal seam distribution

The study area is located along the southern margin of the Lvliang Mountain and Hedong Coalfield in Shanxi Province, China. It features a loess hilly landform, with alternating loess ridges and valleys. Two stable, mineable coal seams, i.e., Nos. 2 and 10, occur in the mining area, with average thicknesses of 3.81 m and 2.61 m, respectively. The No. 2 coal seam is predominantly exposed at the slope foot of a tributary valley in the Modi Valley, while the No. 10 coal seam is exposed along the steep cliff of the valley. The No. 10 coal seam inclines toward the northwest, and its dip angles are determined at about 4° in the northeast, increasing to 10° to 15° near the Mianyang Mountain and even reaching 30° locally. This coal seam has a maximum burial depth of 150 m, with erosional and pinch-out zones distributed along the southern and northern boundaries, respectively. The normal fault and mudstone formation in the eastern part of the mining area acts as a hydrological barrier, delineating the boundaries of the surface water and groundwater basins. The geological structure can be found as Supplementary Fig. S8 online, the coal mining history and mining methods can be found as Supplementary Fig. S9 online, and the mining-induced surface deformation can be found as Supplementary Fig. S10 online.

Lithology and pollution source

The strata in the study area are relatively thin, with marker layers showing distinct lithologies (Table 1). The Carboniferous strata are rich in pyrite nodules, with the concentration increasing toward the bottom, therefore, these strata are identified as the pollution sources of AMD.

Surface drainage

Multiple coal mining methods had been applied in the study area, among them, the open-pit mining changed the terrain severely, which mainly distributed in the middle and lower reaches of rivers with shallow coal seam, the waste residue was used for land leveling and farmland reconstruction. To maintain moisture in the reconstructed farmland, the lower reaches even exhibit higher elevations than their upper reaches locally, inducing serious silting up. There exist 10 ponding areas in the Niuyao Valley and five in the Banpo Valley within the mining area, preventing surface water from flowing out. Furthermore, the upper reaches of the Yangshan, Gaomei, and Yangwa valleys are silted up. After rainstorms, the surface water in these valleys can only infiltrate underground or evaporate rather than flow out smoothly (Fig. 2).

Methodology

A novel methodology for identifying the recharge pathways of AMD in abandoned coal mines was developed by integrating multidisciplinary technical methods (Fig. 3). Compared to existing approaches, the novel methodology enables the accurate characterization of preferential recharge channels connecting surface water and underground goaves, especially in mining areas with complex terrain. Multiple datasets are required in this study. First, to identify the infiltration and ponding areas, it is necessary to conduct precise topographic mapping, followed by hydrological analysis using ArcGIS 10.8 and field investigations. Second, based on the mining data, the stratigraphic characteristics and HCFZ heights were determined through drilling and DHV. Accordingly, a 3D geological model was established for spatial and hydrologic analyses. Third, boreholes can be utilized to collect samples, monitor groundwater levels, and conduct tracer tests. This will help determine the flow characteristics of groundwater.

The critical points including: (1) The precision determination of the morphologies of HCFZs induced by coal mining using various mining techniques. This requires a comprehensive consideration of geological features and excavation conditions; (2) The spatial extrapolation of HCFZs throughout the study area from representative HCFZs. This necessitates geostatistical modeling and 3D visualization, which enable crucial spatial correlations between fracture networks, surface morphology, and coal seam configuration; (3) Hydrological analysis. Tracer tests and hydraulic gradient calculations are required to identify the bi-directional flow pattern. This analysis involves both surface water systems and phreatic aquifers, highlighting their potential interconnections through fractured zones.

Downhole video

Empirical formulas, derived from extensive data collected, have been widely accepted by both engineering professionals and academic researchers due to their practical efficacy23,35,36. However, these formulas have inherent limitations when used under varying mining methods and specific geological conditions24, resulting in insufficient predictive accuracy to meet the rigorous objective of this study.

Large quantities of drilling and downhole videos were strategically deployed in goaves induced by mining using various methods including excavation, blasting, conventionally mechanized mining and fully mechanized mining. This approach is aimed at systematically determining the developmental characteristics and vertical extents of both caving zones and HCFZs. Previous studies indicate that the HCFZ morphologies vary significantly with the mining scale and coal seam inclination37,38. In the case of a working face at a certain scale, HCFZs exhibit O- and saddle-shaped patterns planarly and vertically, respectively. In contrast, for a working face with limited dimensions, the initial mining phase produces arch-shaped HCFZs39. The experimental design in this study incorporated critical morphological transformations associated with varying dip angles and the progressive advancement of the working face. To achieve conservative estimates, the maximum observed values were used for statistical analysis since underestimated fracture heights tended to cause inadequate anti-seepage design. By systematically distinguishing mining-induced fissures within rock masses from pre-existing fractures, this study successfully determined the heights of HCFZs induced by coal mining using various mining methods.

Spatial analysis

Measured data reveal that fully mechanized mining of the No. 2 coal seam produces a rock movement angle of 55°, while the conventionally mechanized mining of the No. 10 coal seam yields a strata movement angle of approximately 75° in flat seams. For conservative estimation, these parameters were used to calculate the spatial geometries of HCFZs along working faces subjected to conventionally and fully mechanized mining. In the case of other mining method, the mining ranges were treated as assessment units.

By processing the spatial data, this study determined the intersection relationships between the surface, coal seams and HCFZs, and displayed them using the spatial analysis software. Given that the valley terrains have been significantly altered by human activity in recent years, historical remote sensing data and drilling data were required to correct the terrains. This help avoid the negative impact of large-scale artificial filling.

Hydrologic analysis

Multiple methods have been explored to determine the overburden permeability, including computed tomography (CT) scanning of mining-induced fissures in cores40, laboratory experiments on rock permeability under triaxial compression41, in-situ test35,42 and numerical modeling43,44. Despite significant progress, these methods remain inadequate for practical applications primarily due to the difficulty in accurately measuring the permeability coefficient of the overburden using methods such as pumping tests in the field. Therefore, the stress–strain-permeability dependencies and non-Darcy seepage behavior of post-peak fractured rocks are generally used to estimate the permeability coefficient of the composite key strata45.

The hydrologic analysis of surface water using ArcGIS 10.8 accurately determined runoff throughout the study area thanks to high-accuracy surveying and mapping (DEM accuracy: up to 0.3 m). Additionally, areas with rapid surface water infiltration were identified through field surveys after rainstorms, contributing to improved data quality.

However, determining the groundwater flow directions remains a challenge, this study employed field investigations, hydraulic gradient calculations and tracer tests. Specifically, great efforts were made to investigate runoff during rainstorms, especially in areas where runoff diminished or ceased. Meanwhile, substantial targeted drilling was performed in the study area to monitor the groundwater table, and tracer tests were conducted in complex zones to comprehensively determine the groundwater flow directions.

Results

Heights of caving zones and HCFZs

DHV images reveal that the caving zone heights in the No. 2 coal seam range from 6.5 to 16.5 m, corresponding to mining heights of 2‒4.5 m. In contrast, the HCFZ heights in the coal seam span significantly from 19.8 to 91.5 m. Specifically, in small coal mines with mining heights of 2‒2.5 m, the HCFZ heights range from 19.8 to 35.7 m. In small coal mines with a mining height of 4 m, the HCFZ height reaches 61.8 m. In the Dujiagou Coal Mine, where the mining height is 4.5 m fully mechanized mining is used, the HCFZ height is up to 91.5 m.

In small coal pits and mines where excavation and blasting technologies are employed, HCFZs extend through bedrock but fail to penetrate the overlying semi-diagenetic conglomerates and thick red clay, with the HCFZ development being severely hindered (Fig. 4a–f). However, in the case of a great mining height and the application of fully mechanized mining technology, HCFZs can extend through these layers and reach the surface directly (Fig. 4g–j).

DHV images showing the characteristics of HCFZs in the study area. (a)–(c) Images showing that semi-diagenetic conglomerates hinder the HCFZ development under the excavation of the No. 2 coal seam. (d)–(f) Images showing that red clay hinders the HCFZ development under the mining of the No. 2 coal seam through blasting. (g)–(j) Images showing that semi-diagenetic conglomerates fail to hinder the HCFZ development under the fully mechanized mining of the No. 2 coal seam. (k)–(l) Images showing that the roofs do not collapse under the mining of the No. 10 coal seam through excavation and blasting. (m)–(n) Images showing the presence of a caving zone and many fissures in the overburden under the conventionally mechanized mining of the No. 10 coal seam.

No caving zone can be observed in the No. 10 coal seam within small coal pits and mines (Fig. 4k–l), except in Dujiagou Coal Mine (Fig. 4m–n), where a caving zone with heights ranging from 3.9 m to 11.7 m occurs due to the conventionally mechanized mining. The HCFZ heights in the No. 10 coal seam vary from 40.6 to 60.8 m, proving low in small coal pits and small coal mines but high in the Dujiagou Coal Mine.

Spatial relationships between the surface, coal seams, and HCFZs

A comparison between HCFZ heights and treated surfaces (excluding artificial fills) reveals the spatial relationships among the HCFZs of the Nos. 2 and 10 coal seams and the surface (Fig. 5).

The results indicate that the HCFZs of the No. 10 coal seam that reach the surface are primarily observed in low-lying mining zones of the Dujiagou Coal Mine. They exhibit a contiguous distribution pattern in the southern part and a banded distribution pattern along valleys in the northern part. In contrast, the HCFZs of the No. 2 coal seam that extend to the surface occur intensively along mountain ridges in the southeastern part of the mining area, with the remaining mostly scattered on the slopes on either side of the valleys. Additionally, the HCFZs of the No. 10 coal seam that extend to the No. 2 coal seam are mainly distributed in the southern part of the mining area. Multiple tracer tests utilizing sodium fluorescein, fluorescent whitening agents, and NaCl were performed in the study area. The monitoring data revealed that surface infiltration preferentially occurs at the intersections of HCFZs and topography in the Banpo and Yangshan Valleys, characterized by the shallow burial of the No. 10 coal seam. Conversely, in the Niuyao Valley, complex hydrogeological conditions prevented the formation of direct recharge pathways, resulting in limited tracer migration.

Identification of pathways for surface water infiltration

Observational data reveal that the characteristics of mining-induced fissures in the overlying strata are closely related to the mining scale. Conventionally and fully mechanized mining both produce extensive, roughly continuous fissures. In these cases, the fissure density and permeability of the overlying strata increase gradually from the tops of HCFZs downward. In contrast, fissures induced by mining using blasting exhibit a higher density in hard rock layers and lower in weak rock layers, which can impede groundwater infiltration. For instance, in the Niuyao Valley, sandy mudstones with a thickness of about 15 m occur between sandstones in layers K5 and K7. Due to their relatively low permeability, these mudstones prevent the immediate infiltration of water from the upper reaches and groundwater in the goaves of the No. 2 coal seam. As a result, trough-shaped perched water is formed along the paleo-valley above the mudstones. Such water slowly infiltrates into the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam (Fig. 6c).

Schematic diagrams showing pathways for surface water infiltration. (a) and (b) Schematic diagrams showing pathways for surface water infiltration in the Niuyao and Banpo valleys, indicating that the surface water tends to infiltrate to the goaves along the paleo-valleys with thin overburden and high permeability but AMD converges in the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam and then overflows in the Modi Valley. (c) Cross section showing pathways for surface water infiltration in the Niuyao Valley, indicating that the surface water infiltrates into the paleo-valley and the goaves of the No. 2 coal seam, then forms perched water with the groundwater from the upper reaches, and finally slowly infiltrates into the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam.

Pathways for surface water infiltration exhibit different distribution characteristics across watershed units, as exemplified by the Niuyao and Banpo valleys. The Niuyao Valley, characterized by relatively complex hydrogeological conditions, consists of one main and three tributary valleys, all of which contain a large area of artificial fills. In the northern tributary valley, surface water can infiltrate to recharge the goaves of the No. 2 coal seam and then flow downstream along the paleo-valley. The middle tributary valley is severely silted up, causing surface water to directly recharge the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam. In the southern tributary valley, besides recharging the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam directly, surface water initially enters the abandoned mine entrances of the No. 2 coal seam and then recharges the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam at locations connected by HCFZs. In the main valley, three streams of water converge to form a trough-shaped perched water body along the paleo-valley: (1) surface runoff and ponding water subjected to infiltration; (2) groundwater from the upper reaches, recharging the perched water body; and (3) ponding water in the goaves of the No. 2 coal seam on both sides of the valley. After converging, these three water streams collectively recharge the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam along HCFZs. The Banpo Valley also features complex hydrogeological conditions, with recharge pathways widely distributed. Accordingly, the goaves of the Nos. 2 and 10 coal seams are roughly completely connected by HCFZs. In this valley, the HCFZs of the No. 2 coal seam that reach the surface are concentrated in the upper reaches of watersheds, while those of the No. 10 coal seam primarily occur in the middle and lower reaches. Additionally, the surface runoff and the ponding water infiltrate to recharge the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam along HCFZs.

Discussion

In small coal pits mined using excavation, fracture zones and bending zones may occur in the overburden, with caving zones frequently absent. The complete development of these three zones tends to occur in the overlying rocks only in the case of working faces at a certain scale46. Empirical formulas for calculating the heights of caving zones and HCFZs yield merely reference values based on previous observational data. However, their accuracy needs to be further improved when used under varying mining methods, mining scales, and overburden structures. For instance, the stowing method tends to produce lower zone heights compared to the fully mechanized caving method, while fully mechanized mining yields significantly higher three zones than conventionally mechanized mining, blasting, and excavation. Additionally, the overburden with special structural characteristics may inhibit the further upward development of HCFZs. Therefore, it is necessary to determine these heights through observation and theoretical analysis.

The mining sequence of coal seams in the study area affects the heights of caving zones and HCFZs. In the early stage, the Nos. 2 and 10 coal seams were mined alternately. In other words, one coal seam was first mined, while the other was extracted after 2‒3 years when the overburden regained stability. Presently, only the No. 2 coal mine is being mined using reversed mining as the No. 10 coal mine has been shut down. Coal mining would damage the overburden structure. Results of previous studies reveal that weaker overlying rocks are associated with lower heights of caving zones and HCFZs47. Therefore, regardless of the mining sequence, the heights of both zones will generally decrease when the overlying rocks are weakened23.

From the perspective of regional geology, the study area located on the southwestern edge of the Hedong Coalfield, exhibits shallow burial depths of coal seams and relatively thin overburden. Moving toward the middle part of the coalfield in the northwest direction, both the burial depth of the coal seams and the overburden thickness increase. In the southern part of the study area, rock layers between the Nos. 2 and 10 coal seams are typically 40‒45 m thick, with an absence of sandstones in K5. In contrast, in the northwestern part, the rock layers are up to about 60 m thick. River incision has led to the erosion of the No. 2 coal seam in valleys. Meanwhile, the No. 10 coal seam has a shallow burial depth of 15 m locally in the southern part. Notably, the paleo-valley system serves as preferential flow pathways. Geologically, the paleo-valleys are filled with loose Quaternary sediments characterized by high primary porosity and permeability compared to the surrounding tight bedrock. The intersection of these permeable sediments with mining-induced fissures leads to the formation of direct and rapid flow pathways of surface water and meteoric water, significantly intensifying their infiltration into the underlying goaves, formed the groundwater funnel. It also controlling whether the goaves can exchange air with the external environment and accelerate the water rock reaction48,49, as a result, the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam exhibit varying redox environments, as ultimately manifested in the solubility of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in AMD.

The direct connection of HCFZs to the surface and the interconnection between HCFZs and coal seams provide pathways for the infiltration of surface water and the ponding water in the goaves of the No. 2 coal seam into the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam. However, under the influence of various mining methods, rock layers with varying properties, spatial locations, and thicknesses exhibit different permeability. Generally, hard and soft rocks show brittle and plastic mechanical properties, respectively. Compared to soft rocks, hard rocks create more favorable conditions for the propagation of the mining-induced fissures, the interconnectivity of the fracture network, and the increase in permeability35, under the same conditions, mudstones have lower permeability than sandstones and limestones50,51. In the southern part of the study area (e.g., the Banpo and Yangwa valleys), due to the thin overlying rocks of the No. 10 coal seam, most of the mudstones between K5 and K7 produce an insignificant water-blocking effect. Therefore, it can be considered that surface water infiltrates to recharge the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam smoothly. In contrast, in the lower reaches of the Niuyao Valley, the No. 10 coal seam is overlain by thick rock layers, where the sandstones and limestones in K2 to K5 layers exhibit high permeability but the mudstones between K5 and K7 have low permeability. This, combined with the substantial inflow from the upper reaches during the rainy season, leads to the formation of trough-shaped perched water along the paleo-valley.

Based on the distribution of pathways for surface water infiltration and recharge modes in small watersheds, several engineering measures are recommended to reduce the amount of surface water infiltration: valley dredging, laying anti-seepage curtains, repairing weak aquiclude and extracting perched water. To implement engineering measures in the valley for source reduction strategies, a series of factors need to be considered, such as the terrain conditions, the relationship between the HCFZ and the surface, geological and economy conditions. For example, in the U-shaped Niuyao Valley, the HCFZ is connected to the mudstones in layers K5 and K7 in a limited range, primarily at the bottom of the paleo-valley. Accordingly, groundwater accumulates above the mudstones and then infiltrates into the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam. In this case, grouting is suitable to repair the weak aquiclude52,53, and the groundwater resources above the mudstones can be extracted and utilized. In contrast, in the Banpo Valley, which exhibits a narrow U or V shape, HCFZs are connected to the surface on a large scale. In this case, repairing the weak aquiclude using grouting will lead to high costs and low engineering effectiveness. Instead, valley dredging and anti-seepage curtain laying are recommended to discharge surface runoff quickly and reduce the amount of surface water infiltration.

Conclusion

This study systematically investigated the groundwater recharge pathways in the Modi Valley mining area and proposed targeted source reduction strategies for AMD control. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The development of HCFZs is governed by both the mining intensity and the overburden lithology. Advancements in mining technology (e.g., fully mechanized mining) and the presence of hard rock layers significantly increase the vertical propagation of HCFZs. The mining-induced fissures form dense, interconnected networks, which serve as primary pathways for vertical seepage. Notably, the intersection of these mining-induced fissures and the paleo-valley system provides dominant recharge pathways for the goaves of the No. 10 coal seam due to the high permeability of the valley sediments and the accumulation of surface runoff.

-

(2)

Based on the precise identification of infiltration pathways, specific source reduction strategies are proposed to restrict the formation of AMD. Specifically, in the Banpo Valley, it is advisable to dredge silted valleys to eliminate surface ponding and lay anti-seepage curtains to cut off the lateral hydraulic connection between the paleo-valley and the fracture zones. In the Niuyao Valley, it is recommended to repair the weak aquiclude and extract perched water to further minimize the recharge volume.

-

(3)

This study has certain limitations that the long-term effectiveness of the proposed engineering interventions requires further verification. Future work should focus on long-term monitoring of groundwater quality and quantity after the implementation of these control strategies, as well as numerical modeling to optimize the layout of anti-seepage curtains and repairing weak aquiclude under varying rainfall scenarios.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Demers, I. et al. Use of acid mine drainage treatment sludge by combination with a natural soil as an oxygen barrier cover for mine waste reclamation: Laboratory column tests and intermediate scale field tests. Miner. Eng. 107, 43–52 (2017).

Beauchemin, S. et al. Geochemical stability of acid-generating pyrrhotite tailings 4 to 5 years after addition of oxygen-consuming organic covers. Sci. Total Environ. 645, 1643–1655 (2018).

Fan, R. et al. Passivation of pyrite for reduced rates of acid and metalliferous drainage using readily available mineralogic and organic carbon resources: a laboratory mine waste study. Chemosphere 285, 131330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131330 (2021).

Kollias, K., Mylona, E., Papassiopi, N. & Thymi, S. Application of silicate-based coating on pyrite and arsenopyrite to inhibit acid mine drainage. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 108, 532–540 (2022).

Dong, Y., Mingtana, N. & Lin, H. Surface hydrophobic modification of sulfur-containing waste rock for the source control acid mine drainage. Miner. Eng. 220, 109106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2024.109106 (2025).

Siebert, H. M., Marmulla, R. & Stahmann, K. P. Effect of SDS on planctonic acidithiobacillus thiooxidans and bioleaching of sand samples. Miner. Eng. 24, 1128–1131 (2011).

Alekseyev, V. A. Reasons for the formation of acidic drainage water in dumps of sulfide-containing rocks. Geochem. Int. 60, 78–91 (2022).

Gao, J., Ding, J., Kang, J., Wu, X. & Qiu, G. Identification and heavy metal toxicity assessment upon Fe2+-oxidizing ability of Leptospirillum-like bacterium isolated from acid mine drainage (in Chinese). J. Nonferrous Met. 21, 220–226 (2011).

Ighalo, J. O. et al. A review of treatment technologies for the mitigation of the toxic environmental effects of acid mine drainage (AMD). Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 157, 37–58 (2022).

Chaerun, S. K. et al. Coal mine wastes: Effective mitigation of coal waste slurry and acid mine drainage through bioflocculation using mixotrophic bacteria as bioflocculants. Int. J. Coal Geol. 279, 104370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2023.104370 (2023).

Huang, Y. et al. Characteristics of iron-sulfur metabolism and acid-producing microorganisms in groundwater contaminated by acid mine drainage in closed coal mines. Groundwater Sustain. Develop. 27, 101372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2024.101372 (2024).

Shabalala, A. N., Ekolu, S. O., Diop, S. & Solomon, F. Pervious concrete reactive barrier for removal of heavy metals from acid mine drainage - column study. J. Hazard. Mater 323, 641–653 (2017).

Farage, R. M. P. et al. Kraft pulp mill dregs and grits as permeable reactive barrier for removal of copper and sulfate in acid mine drainage. Sci. Rep. 10, 4083. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60780-2 (2020).

Chang, J. et al. Effective treatment of acid mine drainage by constructed wetland column: coupling walnut shell and its biochar product as the substrates. J. Water Process Eng. 49, 103116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103116 (2022).

Cai, Q. et al. Gradient of acid mine drainage regulates microbial community assembly and the diversity of species associated with native plants. Environ. Pollut. 363, 125059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125059 (2024).

Fan, C. et al. Fe(II)-mediated transformation of schwertmannite associated with calcium from acid mine drainage treatment. J. Environ. Sci. 126, 612–620 (2023).

Li, T., Cheng, F., Du, X., Liang, J. & Zhou, L. Efficient removal of metals and resource recovery from acid mine drainage by modified chemical mineralization coupling sodium sulfide precipitation. J. Environ. Sci. 156, 399–407 (2025).

Rodríguez-Alegre, R. et al. Improving efficiency and circularity of selective metals recovery from acid mine drainage. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114655 (2024).

Liu, T. Influence of mining activities on mining rockmass and control engineering (in Chinese). J. China Coal Soc. 20, 1–5 (1995).

Qian, M., Miao, X. & He, F. Analysis of key block in the structure of voussoir beam in longwall mining (in Chinese). J. China Coal Soc. 19, 557–563 (1994).

Qian, M., Miao, X. & Xu, J. Theoretical study of key stratumin ground control (in Chinese). J. China Coal Soc. 21, 225–230 (1996).

Song, Z., Jiang, Y. & Liu, J. Theory and model of ‘practical method of mine pressure control’ (in Chinese). Coal Sci. Technol. Magazine 2, 1–10 (2017).

Qu, Q., Xu, J., Wu, R., Qin, W. & Hu, G. Three-zone characterization of coupled strata and gas behavior in multi-seam mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mini. 78, 91–98 (2015).

Meng, Z., Shi, X. & Li, G. Deformation, failure and permeability of coal-bearing strata during longwall mining. Eng. Geol. 208, 69–80 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Determination method of rational position for working face entries in coordinated mining of section coal pillars and lower sub-layer. Sci. Rep. 15, 29440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15115-4 (2025).

Miao, X., Cui, X., Wang, J. & Xu, J. The height of fractured water-conducting zone in undermined rock strata. Eng. Geol. 120, 32–39 (2011).

Wei, J. et al. Formation and height of the interconnected fractures zone after extraction of thick coal seams with weak overburden in Western China. Mine Water Environ. 36, 59–66 (2017).

Poulsen, B., Adhikary, D. & Guo, H. Simulating mining-induced strata permeability changes. Eng. Geol. 237, 208–216 (2018).

Zhu, Z. et al. Mining-induced fracture network reconstruction and anisotropic mining-enhanced permeability evaluation using fractal theory. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 17, 2256–2275 (2025).

Song, X. et al. Using hydrological modelling and data-driven approaches to quantify mining activities impacts on centennial streamflow. J. Hydrol. 585, 124764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.124764 (2020).

Luan, J., Zhang, Y., Tian, J., Meresa, H. & Liu, D. Coal mining impacts on catchment runoff. J. Hydrol. 589, 125101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125101 (2020).

Tang, L. & Zhang, Y. Study on simulation of special underlying surface runoff in goaf area (in Chinese). Water Resour. Hydrop. Eng. 53, 31–42 (2022).

Cheng, W. et al. Research on the simulation of groundwater flow fields disturbed by coal mining based on multi-scale coupled decision-making. J. Environ. Manage. 391, 126441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126441 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Simulation of surface water–groundwater interaction in coal mining subsidence areas: A case study of the Kuye River Basin in China. J. Hydrol. 659, 133243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2025.133243 (2025).

Huang, W. P. et al. In situ identification of water-permeable fractured zone in overlying composite strata. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 105, 85–97 (2018).

Wang, F., Xu, J., Chen, S. & Ren, M. Method to predict the height of the water conducting fractured zone based on bearing structures in the overlying strata. Mine Water Environ. 38, 767–779 (2019).

Xia, X. Study on “four-zone” models of mining strata and surface movement (in Chinese). Doctoral dissertation, Xi`an University of Science and Technology (2012).

Yu, M., Zuo, J., Sun, Y., Mi, C. & Li, Z. Investigation on fracture models and ground pressure distribution of thick hard rock strata including weak interlayer. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 32, 137–153 (2022).

Xu, Z. Overburden fracture migration and surface damage in shallow-buried coal seam with high-intensity mining (in Chinese). Doctoral dissertation, China University of Mining & Technology, Beijing (2021).

Adhikary, D. P. & Guo, H. Modelling of longwall mining-induced strata permeability change. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48, 345–359 (2015).

Shi, X. Study on deformation-failure of overlying strata induced by coal mining and its permeability assessment (in Chinese). Doctoral dissertation, China University of Mining & Technology, Beijing (2016).

Sun, C. et al. Overburden failure characteristics and fracture evolution rule under repeated mining with multiple key strata control. Sci. Rep. 15, 28029. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14068-y (2025).

Wang, G. Characteristics of mining failure and permeability evolution of coal rock pillar at the boundary of closed coal mine (in Chinese). Doctoral dissertation, Anhui University of Science and Technology (2022).

He, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution model of protected coal seam permeability before and after first fracture of overlying key strata: a case study of Mengjin coal mine. Environ. Earth Sci. 84, 557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-025-12516-6 (2025).

Sun, Q., Zhang, J., Li, M. & Zhou, N. Experimental evaluation of physical, mechanical, and permeability parameters of key aquiclude strata in a typical mining area of China. J. Clean. Prod. 267, 122109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122109 (2020).

Wang, S., Li, X. & Wang, S. Separation and fracturing in overlying strata disturbed by longwall mining in a mineral deposit seam. Eng. Geol. 226, 257–266 (2017).

Xu, J. & Qian, M. Study on the influence of key strata movement on subsidence (in Chinese). J. China Coal Soc. 25, 122–126 (2000).

Awoh, A. S., Mbonimpa, M., Bussière, B., Plante, B. & Bouzahzah, H. Laboratory study of highly pyritic tailings submerged beneath a water cover under various hydrodynamic conditions. Mine Water Environ. 33, 241–255 (2014).

Rey, N. J., Demers, I., Bussière, B. & Mbonimpa, M. Laboratory study of low-sulfide tailings covers with elevated water table to prevent acid mine drainage. Can. Geotech. J. 57, 1998–2009 (2020).

Miao, K. et al. Utilization of broken rock in shallow gobs for mitigating mining-induced water inrush disaster risks and environmental damage: Experimental study and permeability model. Sci. Total Environ. 903, 166812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166812 (2023).

Meng, S., Wu, Q., Zeng, Y. & Gu, L. Enhancing mine groundwater system prediction: Full-process simulation of mining-induced spatio-temporal variations in hydraulic conductivities via modularized modeling. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 34, 1625–1642 (2024).

Cao, Z. et al. Diffusion evolution rules of grouting slurry in mining-induced cracks in overlying strata. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58, 6493–6512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04445-4 (2025).

Ren, H. et al. Managing acidic mine water pollution in karst regions based on hydrogeological structures. Res. Eng. 24, 103399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103399 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We deeply appreciate the efforts of the project participants and their discussions on scientific issues. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (42430718), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3710000), and Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Water Pollution (2023GC010650).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Z., C.Z. and H.L. conceived and designed the study. C.Z. drafted the original manuscript, F.Z. and W.M. conducted a thorough review of the manuscript, contributing critical revisions to improve clarity and scientificalness. C.Z. and F.Z. coordinated the writing process, ensuring coherence across sections and managing the feedback. F.Z. and H.L. is responsible for the funding acquire. All authors read, revised, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Zhang, F., Mu, W. et al. Acid mine drainage control in mining areas: identification of groundwater recharge pathways and source reduction strategies. Sci Rep 16, 3593 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33612-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33612-4