Abstract

We propose and numerically validate a scheme for the realization of Schrödinger cat-like states in a two-component Bose-Einstein condensate, emphasizing their twinning across components under tunable intra- and inter-species interactions within the miscibility regime. Wigner phase-space analysis reveals sub-Planck-scale interference fringes, confirming the nonclassical character of the states and their potential utility in quantum-enhanced metrology. The dynamical response of the system to a weak linear gravitational-like perturbation further demonstrates cooperative enhancement: while the directly perturbed component retains its cat-like features, the coupled partner exhibits a pronounced population imbalance and a distinct phase-space rotation, providing a sensitive detection channel absent in single-component condensates. These results establish binary condensates as a versatile platform for engineering macroscopic quantum superpositions and exploiting their twinning dynamics for precision measurements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The experimental realization of Bose-Einstein condensation (BEC) in dilute alkali vapors1,2,3 opened new avenues for exploring macroscopic quantum phenomena in weakly interacting degenerate gases. Ultracold atomic systems have since become a versatile platform in atomic, molecular, and optical physics, as well as nonlinear wave dynamics4,5,6,7, owing to advances in trapping, cooling, and interaction control techniques8. A key breakthrough was the creation of two-component condensates by Myatt et al. in 19979, which enabled the study of binary Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs) with rich interaction-driven physics not present in single-species systems. Binary mixtures exhibit tunable miscibility, determined by the balance of intra- and interspecies interactions, leading either to overlapping or phase-separated states. Experimental demonstrations include immiscibility in \(^{87}\)Rb mixtures10,11,12 and controllable miscibility under attractive or weakly repulsive couplings13,14,15, supported by theoretical stability analyses16,17. Such systems have revealed diverse nonlinear phenomena, including soliton formation20,21, quenched dynamics22, controlled phase separation23, dual-species condensates10,24, tunable miscibility in heteronuclear mixtures25, nonlinear excitations26, hydrodynamic modes27, collision-induced dynamics28, and beyond-mean-field effects29,30,31. These developments establish binary BECs as a fertile ground for probing emergent states of matter and motivate studies of coherence, correlations, and nonlinear excitations under tailored external potentials. In particular, exploring cat-like states, phase-space distributions, and responses to weak linear perturbations such as gravity-like fields opens new pathways for precision metrology and quantum state engineering.

On the theoretical front, binary BECs have been widely studied across diverse trap geometries and interaction regimes. Ground-state analyses have addressed density profiles and excitation spectra32, phase separation in confined and homogeneous systems33, Thomas-Fermi classifications34, and analytical treatments of segregated regimes35,36. The energetics and geometry transitions of the interface37,38, the stability diagrams of density-functional approaches39, and the coupling-strength thresholds for collapse and coexistence40 further elucidate the boundaries of miscibility - immiscibility. Nonlinear dynamics adds further richness: modulation instability drives fragmentation and domain formation41,42, with growth rates and dynamical instabilities examined in collisional and gain-induced settings43,44,45,46. Soliton physics has revealed dark-bright solitons in inhomogeneous traps47, vector soliton collisions48, lattice-induced excitations49, and long-lived solitary structures50, alongside Faraday patterns51, vortex nucleation52, bright solitary vortices53, gap solitons in optical lattices54, and quantum echo dynamics55. In parallel, macroscopic quantum superpositions–Schrödinger cat states–have been realized across optical systems56,57,58, atomic ensembles59,60, superconducting circuits61,62, and quantum optical setups63,64. These states serve as key resources for foundational tests in quantum mechanics65, quantum metrology66,67,68,69,70,71,72, and quantum information processing73,74,75. Binary BECs provide a natural setting for engineering such mesoscopic superpositions: double-well confinement induces cat-like states in one component, which can transfer coherence to the second under miscible conditions. This coupling enables twin cat-like states, identifiable through correlation functions and Wigner distributions, establishing binary BECs as promising platforms for nonlinear many-body physics and quantum-enhanced metrology, including gravity-like sensing.

In this work, we propose and analyze a binary BEC framework for the controlled generation and transfer of cat-like states between two miscible components. By judiciously tuning the intra- and interspecies interaction strengths, we demonstrate that a nonclassical cat-like state initially prepared in one component can be faithfully replicated in the other, a mechanism that we designate as state twinning. The underlying dynamics are modeled within the mean-field description using coupled Gross-Pitaevskii equations (GPEs), where the ground-state configurations are obtained through imaginary-time propagation, and the subsequent dynamical evolution is investigated via real-time simulations. The efficiency of state transfer is systematically characterized using a combination of first-order coherence functions, Wigner phase-space distributions76,77, and population imbalance diagnostics in a double-well potential geometry78. This multifaceted analysis not only captures the quantum coherence properties but also elucidates the role of nonlinear interactions in stabilizing and propagating cat-like features across the binary mixture. Furthermore, we illustrate that the proposed scheme constitutes a versatile platform for precision quantum metrology, as evidenced by its enhanced sensitivity to weak, linear gravitational-like perturbations79,80,81. A systematic stability analysis has been performed to evaluate the feasibility and robustness of the system under realistic, noise-induced perturbations. These results underscore the potential of multi-component condensates as robust carriers of non-classical correlations with direct relevance to emerging quantum technologies.

Theoretical framework and dynamical equations

We consider a binary BEC, where the two components represent distinct hyperfine states of the same atomic species. The dynamics of such a multicomponent condensate is well described within the mean-field framework by a set of coupled GPEs82. In the present work, we assume that the condensate is confined in a highly anisotropic, cigar-shaped trapping geometry. Under conditions of strong transverse confinement in the y and z directions, such that \(\omega _\perp \gg \omega _x\), the system undergoes a dimensional reduction to an effective quasi-one-dimensional (1D) model83,84. In dimensionless units, the evolution of condensate wavefunctions \(\psi _{j}(x,t)\) (\(j=1,2\)) is governed by coupled GPEs:

Here, x is expressed in units of the transverse harmonic oscillator length \(l=\sqrt{\hbar /m\omega _\perp }\), with \(\omega\) denoting the transverse trapping frequency. Energies and times are expressed in units of \(\hbar \omega _\perp\) and \(1/\omega _\perp\), respectively. The condensate wavefunctions are normalized as \(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty } |\psi _{j}(x,t)|^2 dx = 1\). For simplicity, we consider equal atomic masses and equal populations in both components, i.e., \(m_{1}=m_{2}=m\) and \(N_{1}=N_{2}=N\), so that the density unit is \(Nl^{-2}\). The effective interaction parameters are defined as \(g_{j}=2Na_{j}/l\) and \(g_{12}=2Na_{12}/l\), where \(a_{j}\) and \(a_{12}\) are the intra- and interspecies s-wave scattering lengths, respectively.

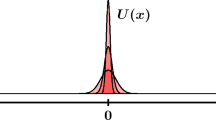

Our objective is to investigate the state twinning mechanism, in which a cat-like superposition generated in one component is effectively replicated in the other. To this end, we consider component 1 to evolve in free space, i.e., \(V_{1}(x)=0\), while component 2 is subject to a double-well-type potential of the form

where \(\gamma\) denotes the normalized harmonic confinement strength, while A and \(\sigma\) represent the scaled amplitude and width of the Gaussian barrier, respectively. This configuration enables the controlled preparation of macroscopic superposition states in component 2, which can then be dynamically mapped onto component 1 through interspecies interactions. From an experimental perspective, such a binary mixture can be realized with alkali atoms such as \(^{87}\)Rb or \(^{39}\)K, where two hyperfine states of the same isotope serve as the two components11,85. The ability to tune intra- and interspecies scattering lengths via Feshbach resonances provides an additional handle to access the desired interaction regimes86. Double-well potentials of the type considered here have been routinely implemented using optical lattices or focused laser beams87, thereby making the proposed scheme experimentally feasible within current ultracold-atom platforms.

The dynamical equations (1) and (2) represent coupled GPEs, which belong to the larger class of nonlinear Schrödinger-type equations. Such equations provide a well-established mean-field description of binary BECs, capturing the interplay of dispersion, external confinement, and nonlinear interactions. To investigate the binary system, we numerically integrate these equations using the split-step Fourier method (SSFM)88,89,90, a spectral algorithm particularly suited for nonlinear dispersive systems. The SSFM efficiently treats the linear kinetic term in momentum space while evaluating the nonlinear and potential terms in position space, making it highly accurate and computationally efficient for simulating condensate dynamics. This framework enables us to compute both ground-state properties and the subsequent real-time dynamical evolution. To determine the ground state, we employ the imaginary-time propagation (ITP) technique, in which the real-time variable t is analytically continued to \(-i\tau\)91,92. This transformation suppresses excited-state contributions and drives the system toward the lowest-energy stationary solution, provided that normalization of the condensate wavefunction is enforced at every iteration. The ITP method is widely used in BEC studies because of its robustness and reliability in preparing equilibrium states.

For the present simulations, we adopt the following numerical parameters: spatial grid size \(N_x = 2^5\), spatial discretization step \(dx = 0.001\), real-time step \(dt = 0.001\), imaginary-time step \(d\tau = 0.001\), and convergence tolerance of \(10^{-6}\). These values are chosen to ensure a balance between computational efficiency and numerical precision, in accordance with established practices in the literature90,91. The combination of SSFM for dynamical propagation and ITP for ground-state preparation thus provides a robust and well-validated numerical framework for exploring the static and dynamical properties of binary condensates.

Cat-like ground-state properties and coherence analysis

To obtain the cat-like ground-state solutions of Eqs. (1) and (2), we initialize the system with a Gaussian ansatz of the form

where \(d_j\) denotes the initial width of the condensate wavefunction for the component j. For dimensionless simulations, we adopt the parameters \(d_1=d_2=2.24\), \(\sigma = 4\), \(\gamma = 0.1\), \(V_{1}=0\), \(A = 5\), \(g_{1}=-0.5\), \(g_{2}=2\), \(g_{12}= - 5\) and \(N=10^{4}\). Mapping these values to a physical realization with \(^{87}\)Rb atoms yields the corresponding experimental parameters: axial and transverse trap frequencies \((\omega _x,~\omega ) = (10,~100)\,\text {Hz}\), atomic mass \(m = 87\) amu, harmonic oscillator length \(l = 2.70~\mu \text {m}\), and widths of the initial condensates \(d_1=d_2= 6.05~\mu \text {m}\). The intraspecies scattering lengths (in terms of Bohr radius \(a_0\)) are \(a_{1} = -1.28a_{0}\) and \(a_{2} = 5.10a_{0}\), while the interspecies scattering length is \(a_{12} = -12.76a_{0}\). The Gaussian barrier amplitude is set to \(A = 5\hbar \omega\), with width \(\sigma = 10.8~\mu \text {m}\), and \(V_{1}=0\). These parameters are within the range of experimentally achievable values in ultracold atomic systems, ensuring direct relevance to ongoing laboratory efforts.

The stationary ground state corresponds to a time-invariant solution of the coupled dynamical equations. To determine this state, we solved Eqs. (1) and (2) numerically using the split-step Fourier method in conjunction with imaginary-time propagation88,91,92. Figure 1 presents the results: (a) the initial density profiles \(|\psi _j^{i}(x)|^2\) with the scaled external potential \(V_{2}(x)\), (b) the convergent ground-state densities \(|\psi _j(x)|^2\) for both components, and (c), (d) the dynamics of density relaxation during imaginary-time propagation for components 1 and 2, respectively. The results reveal that the presence of a double-well potential in component 2 induces a characteristic cat-like splitting of its density distribution. Due to strong interspecies coupling under miscible conditions, component 1–although initially in a potential-free environment–undergoes a parallel splitting process. This leads to the emergence of a cat-like density distribution in both components, highlighting the mechanism of intercomponent state transfer.

The energetic properties of the condensates provide a complementary perspective on their stability. The energy functional \(E_j\) and chemical potential \(\mu _j\) associated with the macroscopic wavefunctions \(\psi _j(x,t)\) are defined as

with the total energy \(E_{t}(\tau )=E_1(\tau )+E_2(\tau )\). The corresponding chemical potential is

with total chemical potential \(\mu _{t}(\tau )=\mu _1(\tau )+\mu _2(\tau )\).

Figure 2 displays the temporal evolution of the total energy and chemical potential during imaginary-time propagation. Both quantities decrease monotonically, eventually saturating to constant values, which signifies convergence to the ground state. This monotonic relaxation process reflects the dissipation of higher-energy excitations and stabilization of the stationary cat-like configuration.

First-order correlation

The first-order correlation function \(G^{(1)}(t)\) provides a direct measure of coherence between the two components, and is defined as

By definition, \(0 \le G^{(1)}(t) \le 1\), with unity denoting perfect coherence and zero corresponding to complete incoherence82.

Figure 3 shows the variation of \(G^{(1)}(\tau )\) during imaginary-time propagation. Initially, \(G^{(1)}(0)=1\), as both components start from identical Gaussian wavefunctions. As evolution progresses, the double-well potential \(V_{2}(x)\) induces fragmentation in component 2, reducing coherence due to a phase mismatch with component 1. However, at later times, component 1 dynamically adapts to the density profile of component 2, leading to a partial recovery of coherence. Eventually, \(G^{(1)}(\tau )\) stabilizes near 0.99, confirming that the two components share almost perfect coherence in their stationary states.

Wigner phase-space distribution

The Wigner phase-space distribution W(x, p) offers a powerful tool for characterizing quantum states beyond conventional position- or momentum-space descriptions76. Defined as

captures the quasi-probability distribution of a wavefunction \(\psi _j(x)\) in phase space. The Wigner function possesses the key properties of (i) being real-valued, (ii) reproducing \(|\psi (x)|^2\) and \(|\psi (p)|^2\) as its marginals, and (iii) admitting negative values as signatures of non-classicality.

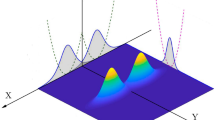

In the presence of a double-well potential, the binary condensate can host cat-like quantum states, which are characterized by coherent superpositions of macroscopically distinct configurations. A powerful diagnostic tool for such states is the Wigner quasi-probability distribution, which provides a phase-space representation of the quantum state. In particular, the emergence of interference fringes at sub-Planck scales in the Wigner function signals pronounced nonclassical correlations and phase coherence between the superposed components. Such fine-scale structures are not only hallmarks of quantum superposition but also underpin applications in quantum-enhanced metrology and precision interferometry, where sub-Planck features are directly linked to sensitivity beyond the standard quantum limit. Figure 4 presents the Wigner phase-space distributions corresponding to the ground states of components 1 and 2. The near-identical patterns exhibited by the two components demonstrate that the cat-like superposition formed in component 2 is faithfully twinned in component 1. This one-to-one correspondence highlights the strong inter-component coherence and mutual phase locking, thereby confirming the emergence of twinned macroscopic quantum states across the two condensates.

Panels (a) and (b) show the ground-state density distributions of components 1 and 2, respectively, for attractive (\(g_1=-0.5\)) and repulsive (\(g_1=0.5\)) intra-atomic interactions in component 1, with \(g_2=2\) and \(g_{12}=-5\). For \(g_1=-0.5\), component 1 exhibits stronger localization, while component 2 remains essentially unchanged. Panel (c) displays the first-order correlation function \(G^{(1)}(\tau )\) as a function of \(\tau\), where the attractive case (\(g_1=-0.5\)) achieves the highest correlation, reaching \(G^{(1)}(\tau )\approx 0.998\) between the two components. The difference in \(G^{1}(\tau )\) for \(g_1=-0.5\) and \(g_1=0.5\) is presented as \(\Delta G^{1}(\tau )\), which is shown in the inset over the range \(\tau\) =17 to 20.

Twinning dynamics under the influence of intra-species interactions

In the preceding discussion, we analyzed the emergence of cat-like ground states in the presence of attractive intra-species interactions (\(g_{1}=-0.5\)) within component 1. Since interatomic interactions can be experimentally tuned across both attractive and repulsive regimes via Feshbach resonances, it is instructive to examine how such variations influence the robustness of ground-state twinning between the two components. To this end, we compare the case of repulsive intra-species interactions (\(g_{1}=0.5\)) in component 1 with the attractive regime previously considered. Our results reveal that the density profile of component 1 in the ground-state exhibits a stronger localization in the attractive case (\(g_{1}=-0.5\)), while repulsion (\(g_{1}=0.5\)) leads to a more delocalized configuration [Fig. 5(a)]. In contrast, the density distribution of component 2 remains nearly invariant under the change of \(g_{1}\) [Fig. 5(b)], indicating that the effect of intra-species tuning in component 1 is not directly transferred to component 2 at the density level. However, the influence becomes more evident in the coherence properties of the coupled system. Figure 5(c) depicts the first-order correlation function \(G^{(1)}(\tau )\) as a function of \(\tau\). In the repulsive regime, coherence builds up more rapidly, but the maximum correlation reached is lower compared to the attractive case. By contrast, attractive interactions produce a higher degree of long-range coherence, achieving \(G^{(1)}(\tau ) \approx 0.998\), indicating a nearly perfect mirroring of the cat-like state across the two components.

The Wigner density distribution W(x, P) in phase-space of both components at time \(t=10\). The presence of linear perturbative potential doesn’t makes any significant rotational change in the interference fringe in \(W_2(x,p)\) (see fig. (b)), but a significant change is visible in the interference fringe which is noise in \(W_1(x,p)\) presented in (a). Furthermore, we present projections of the Wigner function \(W(x,p)\) at a fixed position (\(x = -6.158\)) and a fixed momentum (\(p = -0.15\)), selected to maximize the observable variation of \(W\) for both components. Panels (c) and (e) depict the position-space projections of \(W\), while panels (d) and (f) show the corresponding momentum-space projections for components 1 and 2, respectively. Component 1 is more sensitive than component-2, even though perturbation is given in component 2.

From a physical perspective, this asymmetry between attractive and repulsive regimes can be understood in terms of the competition between kinetic, interaction, and tunneling energies. In the attractive case, the negative interaction energy reduces the spatial extent of the wavefunction, lowering the overall energy of localized states and thereby suppressing quantum fluctuations. This enhanced localization amplifies overlap with the inter-species interaction channel, effectively reinforcing the twinning of cat-like states. In contrast, for repulsive interactions, the system minimizes the interaction energy by delocalizing the condensate wavefunction. The increased kinetic and tunneling contributions diminish localization, which weakens inter-component coherence and results in a reduced degree of twinning. Thus, our analysis demonstrates that attractive intra-species interactions create a more favorable energetic balance for sustaining cat-like ground-state twinning. The interplay between localization-induced coherence and interspecies coupling highlights the crucial role of interaction sign and strength in stabilizing macroscopic quantum correlations in binary condensates.

Cross-component amplification and metrological sensitivity

To explore the metrological relevance of the system, we investigate its response to a weak linear gravitational-like perturbation \(P_{L}=Gx\) superimposed on the double-well confinement of component 2. The coupled Gross-Pitaevskii equations (1) and (2) are solved in real time using the SSFM, with ground-state solutions obtained via imaginary-time propagation serving as the initial ansatz for dynamics. The simulations employ the following parameters: spatial grid size \(N_{x}=2^{5}\), spatial step \(dx=0.001\), time step \(dt=0.001\), barrier width \(\sigma =4\), harmonic frequency \(\gamma =0.1\), Gaussian barrier amplitude \(A=5\), perturbation strength \(G=0.25\), and interaction coefficients \(g_{1}=-0.05\), \(g_{2}=1\), and \(g_{12}=-5\). Component 1 evolves in a potential-free environment (\(V_{1}=0\)), while component 2 is confined in a tilted double-well potential \(V_{2}(x)+P_{L}\).

Figures 6(a) and (b) present the density dynamics up to \(t=10\). At first sight, both components appear nearly symmetrically distributed between the wells. However, given the applied tilt, one expects a bias toward the left well. This asymmetry becomes evident when analyzing the population imbalance

which quantifies the relative difference in the atom number between the wells. As shown in Fig. 6(c), \(Z_{2}(t)\approx 0\) indicates that the directly perturbed component remains almost symmetric, while \(Z_{1}(t)>0\) reveals a pronounced imbalance in the unperturbed component. This counterintuitive cross-component amplification demonstrates that component 1 functions as a more sensitive probe of the perturbation than component 2 itself, a property absent in single-component condensates. To further highlight this sensitivity, Fig. 7 shows the Wigner phase-space distributions \(W_{j}(x,p)\) for both components at \(t=10\). The two coherent lobes for both \(W_{1}(x,p)\) and \(W_{2}(x,p)\) show a phase-space rotation, lobes are shifted in opposite directions, and their centers drift away from \(p=0\). It is the interference fringes that show a differential sensitivity of the two components to the perturbation.

To better highlight the sensitivity effects shown in Fig. 7, we present projections of the Wigner function \(W(x,p)\) at a fixed position (\(x = -6.158\)) and a fixed momentum (\(p = -0.15\)), chosen to maximize the observable variation of \(W\) for both components. The interference fringes in the Wigner distribution emerge along the position and momentum axes, depending on the spatial separation and the relative phase of the two coherent states, respectively. Notably, a larger modification of the interference fringes is observed in Fig. 7(c) and (d), corresponding to component 1, compared with Fig. 7(e) and (f), respectively. This indicates a more pronounced relative phase-space separation between the superposed coherent states in component 1.

From a broader perspective, these results illustrate how intercomponent coupling transforms the binary system into a collective quantum sensor: one component acts as an active probe experiencing the perturbation, while the other functions as a passive amplifier that records the perturbation with enhanced visibility. The amplification is rooted in the nonlinear redistribution of interaction energy, tunneling dynamics, and coherence transfer between components. Such features are highly relevant for quantum-enhanced metrology, particularly in the detection of weak forces such as gravity, acceleration, or subtle potential gradients, where sensitivity beyond the limits of single-component is required76,82. The proposed scheme can be realized using ultracold atomic mixtures such as \(^{87}\)Rb or \(^{39}\)K, where both intra- and interspecies interaction strengths are tunable via magnetic Feshbach resonances. State-dependent optical lattices combined with a Gaussian barrier allow for the engineering of tilted double-well configurations. Real-time detection of density imbalance is accessible through absorption or phase-contrast imaging, while Wigner phase-space features can be reconstructed using matter-wave interferometry. Importantly, the sensitivity enhancement observed here relies on standard experimental tools already available in cold-atom laboratories, making this approach experimentally feasible within current technological capabilities.

Stability analysis

In experiments involving the complex dynamics of BECs under intricate trapping potentials and nonlinear interactions, structural stability is often a critical concern. Under realistic laboratory conditions, unavoidable noise originating from the system or its environment can modify condensate evolution. To account for this and enhance the realism of our model, we carried out a structural stability analysis by introducing stochastic perturbations. Specifically, a random white-noise term \(R_w\), with an amplitude set to \(10\%\) of the maximum Gaussian potential A, was added to the external potential, yielding

The ground-state solutions were subsequently evolved in real time up to \(t = 50\) to assess the effect of noise on the condensate density dynamics. For this noise amplitude, the standard deviations in the densities of components 1 and 2 were found to be 0.0288 and 0.0283, respectively. Since these deviations are negligible compared to the corresponding peak densities, the overall density profiles remain largely unchanged with only minimal deformation. This confirms that the proposed model exhibits robust structural stability even in the presence of stochastic perturbations.

Conclusion

In summary, we have introduced and numerically validated a scheme for the generation of Schrödinger cat-like states in a two-component Bose-Einstein condensate, with particular emphasis on their twinning across components under suitable interaction regimes. By tuning the intra- and inter-species interactions within the miscibility window, the binary condensate exhibits robust replication of nonclassical features, as confirmed through Wigner phase-space analysis. The observed interference fringes at sub-Planck scales serve as clear hallmarks of quantum coherence and nonclassicality, underscoring the suitability of such states for quantum-enhanced metrological protocols. Beyond state preparation, we investigated the response of the coupled system to a weak linear gravitational-like perturbation. Strikingly, while the perturbed component preserves its cat-like character, the twinned partner develops a pronounced population imbalance and undergoes a characteristic phase-space rotation in its Wigner distribution. This differential sensitivity highlights the cooperative enhancement inherent to the two-component architecture and reveals a detection channel unavailable in single-component condensates. Altogether, our results establish binary BECs as a versatile platform for engineering macroscopic quantum superpositions and exploiting their twinning dynamics for metrological applications. The demonstrated resilience of cat-like states against direct perturbation, combined with the amplified response of their twins, opens promising pathways for quantum sensing, precision measurements, and the controlled study of nonclassical states in many-body systems. The experimental feasibility of the proposed model has been analyzed under noisy conditions, revealing that the system remains sufficiently stable for the realization of sensitive quantum measurements. Looking forward, several extensions arise naturally. Incorporating optical lattice geometries could allow for scalable arrays of twinned cat states, enabling spatially distributed quantum sensors. The role of decoherence, thermal noise, and particle losses warrants systematic study to assess robustness under realistic conditions. Furthermore, exploring time-periodic driving may open connections to discrete time crystals, while engineered disorder or synthetic gauge fields could provide additional handles to probe non-equilibrium dynamics. Taken together, these directions highlight the broader potential of multicomponent condensates as a fertile testbed for foundational studies in quantum coherence and as a platform for next-generation quantum technologies.

Data availibility

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. It can be reproduced by utilizing the form of wavefunction and considered trap profiles.

References

Anderson, M. H. et al. Observations of Bose-Einstein condensation in a dilute atomic vapor. Science 269, 198 (1995).

Davis, K. B. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation in a gas of sodium atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3969 (1995).

Bradley, C. C. et al. Evidence of Bose-Einstein condensation in an atomic gas with attractive interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1687 (1995).

Bagnato, V. S. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation: Twenty years after. Rom. Rep. Phys. 67, 5 (2015).

Mihalache, D. et al. Multidimensional localized structures in optics and Bose-Einstein Condensates: A selection of recent studies. Rom. J. Phys. 559, 295 (2014).

Carretero-González, R. et al. Nonlinear waves in Bose-Einstein condensates: physical relevance and mathematical techniques. Nonlinearity 21, R139 (2008).

Sulem, C. & Sulem, P. L. The nonlinear Schrodinger equation: Self-focusing and wave collapse 139, 1–347 (1999).

Proukakis, N. P. A century of Bose-Einstein condensation. Commun. Phys. 8, 264 (2025).

Myatt, C. J. et al. Production of two overlapping Bose-Einstein condensates by sympathetic cooling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 586 (1997).

McCarron, D. J. et al. Dual-species Bose-Einstein condensate of \(^{87}Rb\) and \(^{133}Cs\). Phys. Rev. A 84, 011603 (2011).

Hall, D. S. et al. Dynamics of Component Separation in a Binary Mixture of Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 1539 (1998).

Tojo, S. et al. Controlling phase separation of binary Bose-Einstein condensates via mixed-spin-channel Feshbach resonance. Phys. Rev. A 82, 033609 (2010).

Lee, K. L. et al. Phase separation and dynamics of two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 94, 013602 (2016).

Ivanova, S. K. & Kamchatnova, A. M. Expansion dynamics of a two-component quasi-one-dimensional Bose-Einstein condensate: Phase diagram, self-similar solutions, and dispersive shock waves. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 124, 546–563 (2017).

Raghav, Sriganapathy et al. Nonlinearity mediated miscibility dynamics of mass-imbalanced binary Bose-Einstein condensate for circular atomtronics. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 474, 134558 (2025).

Xi, K.-T. et al. Fingering instabilities and pattern formation in a two-component dipolar Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. A 97, 023625 (2018).

Morise, H. et al. Two-component Bose-Einstein condensates and their stability. Physica A 281, 432–441 (2000).

Maddaloni, P. et al. Collective Oscillations of Two Colliding Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2413 (2000).

Ferrier-Barbut, I. et al. A mixture of Bose and Fermi superfluids. Science 345, 1035 (2014).

Hamner, C. et al. Generation of Dark-Bright Soliton Trains in Superfluid-Superfluid Counterflow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 065302 (2011).

Hoefer, M. A. et al. Dark-dark solitons and modulational instability in miscible two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 84, 041605 (2011).

De, S. et al. Quenched binary Bose-Einstein condensates: Spin-domain formation and coarsening. Phys. Rev. A 89, 033631 (2014).

Papp, S. B. et al. Tunable Miscibility in a Dual-Species Bose-Einstein Condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 040402 (2008).

Wacker, L. et al. Tunable dual-species Bose-Einstein condensates of \(^{39}K\) and \(^{87}Rb\). Phys. Rev. A 92, 053602 (2015).

Wang, F. et al. A double species 23Na and 87Rb Bose-Einstein condensate with tunable miscibility via an interspecies Feshbach resonance. J. Phys. B 49, 015302 (2016).

Mertes, K. M. et al. Nonequilibrium Dynamics and Superfluid Ring Excitations in Binary Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 190402 (2007).

Mossman, Sean M. et al. Observation of dense collisional soliton complexes in a two-component Bose-Einstein condensate. Commun. Phys. 7, 163 (2024).

Eto, Y. et al. Bouncing motion and penetration dynamics in multicomponent Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 93, 033615 (2016).

Lavoine, L. et al. Beyond-Mean-Field Effects in Rabi-Coupled Two-Component Bose-Einstein Condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 203402 (2021).

Romero-Ros, A. et al. Experimental Realization of the Peregrine Soliton in Repulsive Two-Component Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 033402 (2024).

Delannoy, G. et al. Understanding the production of dual Bose-Einstein condensation with sympathetic cooling. Phys. Rev. A 63, 051602 (2001).

Pu, H. & Bigelow, N. P. Properties of Two-Species Bose Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1130 (1998).

Timmermans, E. Phase Separation of Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5718 (1998).

Trippenbach, M. et al. Structure of binary Bose-Einstein condensates. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 33, 4017 (2000).

Ao, P. & Chui, S. T. Binary Bose-Einstein condensate mixtures in weakly and strongly segregated phases. Phys. Rev. A 58, 4836 (1998).

Barankov, R. A. Boundary of two mixed Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 66, 013612 (2002).

Van Schaeybroeck, B. Interface tension of Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 78, 023624 (2008).

Gautam, S. & Angom, D. Ground state geometry of binary condensates in axisymmetric traps. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 43, 095302 (2010).

Tanatar, B. & Erkan, K. Strongly interacting one-dimensional Bose-Einstein condensates in harmonic traps. Phys. Rev. A 62, 053601 (2000).

Kim, J. G. & Lee, E. K. Characteristic features of symmetry breaking in two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. E 65, 066201 (2002).

Shukla, P. K. et al. Modulational Instability of Two Colliding Bose-Einstein Condensates. Physica Scipta 64, 553 (2001).

Kasamatsu, K. & Tsubota, M. Multiple Domain Formation Induced by Modulation Instability in Two-Component Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 100402 (2004).

Raju, T. S. et al. Modulational instability of two-component Bose-Einstein condensates in a quasi-one-dimensional geometry. Phys. Rev. A 71, 035601 (2005).

Tabi, C. B. et al. Interplay between spin-orbit couplings and residual interatomic interactions in the modulational instability of two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. E 107, 044206 (2023).

Ronen, S. et al. Dynamical pattern formation during growth of a dual-species Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. A 78, 053613 (2008).

Robins, N. P. et al. Modulational instability of spinor condensates. Phys. Rev. A 64, 021601 (2001).

Busch, T. & Anglin, J. R. Dark-Bright Solitons in Inhomogeneous Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 010401 (2001).

Vaduganathan, R. K. et al. Controlled Fission and Superposition of Vector Solitons in an Integrable Model of Two-Component Bose-Einstein Condensates. Symmetry 17(8), 1189 (2025).

Kevrekidis, P. G. et al. Dark-in-bright solitons in Bose-Einstein condensates with attractive interactions. New J. Phys. 5, 64 (2003).

Becker, C. et al. Oscillations and interactions of dark and dark-bright solitons in Bose-Einstein condensates. Nature Physics 4, 496–501 (2008).

Balaž, A. & Nicolin, A. I. Faraday waves in binary nonmiscible Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 85, 023613 (2012).

Feder, D. L. et al. Vortex Stability of Interacting Bose-Einstein Condensates Confined in Anisotropic Harmonic Traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4956 (1999).

D’Ambroise, J. Stability and dynamics of massive vortices in two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. E 111, 034216 (2025).

Pu, Tu. et al. Vector gap solitons of two-component Bose gas in twisted-bilayer optical lattice. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 190, 115773 (2025).

Wang, C. Y. Quantum echo in two-component Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 109, 063327 (2024).

Fengyi, Xu. et al. Quantifying quantum coherence of optical cat states in a noisy channel. Opt. Contin. 4, 1554–1561 (2025).

Zhao, X. L. et al. Optical Schrödinger cat states in one mode and two coupled modes subject to environments. Phys. Rev. A 96, 013824 (2017).

Chen, Y. R. et al. Generation of heralded optical cat states by photon addition. Phys. Rev. A 110, 023703 (2024).

Monroe, C. et al. A Schrödinger Cat Superposition State of an Atom. Science 272, 1131–1136 (1996).

Brune, M. et al. Observing the progressive decoherence of the Meter in a quantum measurement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4887 (1996).

Friedman, J. R. et al. Quantum superposition of distinct macroscopic states. Nature 406, 43 (2000).

van der Wal, C. H. et al. Quantum superposition of macroscopic persistent-current states. Science 290, 773 (2000).

Ourjoumtsev, A. et al. Generating optical Schrödinger kittens for quantum information processing. Science 312, 83 (2006).

Takahashi, H. et al. Generation of large-amplitude coherent-state superposition via ancilla assisted photon-subtraction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 233605 (2008).

Zurek, W. H. Sub-planck structure in phase space and its relevance for quantum decoherence. Nature 412, 712–717 (2001).

Gilchrist, A. et al. Schrdinger cats and their power for quantum information processing. J. Opt. B: Quantum Semiclassical Opt. 6, S828 (2004).

Giovannetti, V. et al. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Li, L. et al. Cat codes with optimal decoherence suppression for a lossy bosonic channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 030502 (2017).

Pezze, L. et al. Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018).

Tóth, G. & Apellaniz, I. Quantum metrology from a quantum information science perspective. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 47, 424006 (2014).

Ghosh, S. et al. Mesoscopic quantum superposition of the generalized cat state: a diffraction limit. Phys. Rev. A 92, 053819 (2015).

Carr, L. D. et al. Cold and ultracold molecules: science, technology and applications. New J. Phys. 11, 055049 (2009).

Vlastakis, B. et al. Deterministically encoding quantum information using 100-photon schrödinger cat states. Science 342, 607–610 (2013).

Xi, Yu. et al. Schrödinger cat states of a nuclear spin qudit in silicon. Nat. Phys. 21, 362–367 (2025).

Hoshi, D. et al. Entangling Schrödinger’s cat states by bridging discrete- and continuous-variable encoding. Nat. Commun. 16, 1309 (2025).

Wigner, E. On the Quantum Correction For Thermodynamic Equilibrium. Phys. Rev. 40, 749 (1932).

Weinbub, J. & Ferry, D. K. Recent advances in Wigner function approaches. Appl. Phys. Rev. 5, 041104 (2018).

Smerzi, A. Quantum Coherent Atomic Tunneling between Two Trapped Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 4950 (1997).

Pattinson, R. W. et al. Equilibrium solutions for immiscible two-species Bose-Einstein condensates in perturbed harmonic traps. Phys. Rev. A 87, 013625 (2013).

Belobo Belobo, D. et al. Exotic complexes in one-dimensional Bose-Einstein condensates with spin-orbit coupling. Sci. Rep. 8, 3706 (2018).

Yang, Q. & Zhang, J. Bose-Einstein solitons in time-dependent linear potential. Opt. Commun. 258, 35 (2005).

Pethick, C. J. & Smith, H. Bose-Einstein Condensation in Dilute Gases 2nd edn. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2008).

Cheng, Y. & Adhikari, S. K. Symmetry breaking in a localized interacting binary Bose-Einstein condensate in a bichromatic optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 81, 023620 (2010).

Adhikari, S. K. & Malomed, B. A. Two-component gap solitons with linear interconversion. Phys. Rev. A 79, 015602 (2009).

Modugno, et al. Bose-Einstein Condensation of Potassium Atoms by Sympathetic Cooling. Science 294, 1320 (2001).

Chin, et al. Feshbach resonances in ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1225 (2010).

Albiez, et al. Direct Observation of Tunneling and Nonlinear Self-Trapping in a Single Bosonic Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 010402 (2005).

Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics (Academic Press, New York, 1995).

Javanainen, J. & Ruostekoski, J. Symbolic calculation in development of algorithms: split-step methods for the Gross-Pitaevskii equation. J. Phys. A: Math. Gener. 39, 179–184 (2006).

Bao, W. & Cai, Y. Mathematical theory and numerical methods for Bose-Einstein condensation. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 73, 2055–2078 (2013).

Bao, Weizhu et al. Numerical Solution of the Gross-Pitaevskii Equation for Bose-Einstein Condensation. J. Comput. Phys. 187, 318–342 (2003).

Antoine, X. & Duboscq, R. GPELab, a Matlab toolbox to solve Gross-Pitaevskii equations I: Computation of stationary solutions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2969–2991 (2014).

Funding

There are no funds, grants, or other support received for Open access funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, Writing-first draft; Jagnyaseni Jogania; Conceptualization, Validation, Writing-review and editing, Supervision; Jayanta Bera and Ajay Nath. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jogania, J., Nath, A. & Bera, J. Nonclassical correlations in binary Bose-Einstein condensates: from double-well confinement to twin Schrödinger cat states. Sci Rep 16, 3565 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33633-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33633-z