Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a major microvascular complication of diabetes, associated with high morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Early detection is challenging due to the lack of highly specific diagnostic tools. This study aimed to develop and validate a nomogram for predicting DKD risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by integrating conventional biochemical indicators with noninvasive lens advanced glycation end product (AGE) measurements. A total of 868 patients with T2DM from Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital (November 2019 to February 2024) were enrolled. Independent predictors of DKD were identified using logistic regression and incorporated into a predictive nomogram. Model performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curves, calibration plots, and decision curve analysis. The cutoff value for lens AGE fluorescence (0.306) was derived from our previous study using ROC analysis with Youden’s index. Seven variables were independently associated with DKD: systolic blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin, triglycerides, serum cystatin C, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, red blood cell count, and lens AGE values. The nomogram showed good discrimination, with an AUC of 0.809 in the training cohort and 0.806 in the validation cohort. Calibration demonstrated close agreement between predicted and observed risk, and clinical utility was confirmed. This novel nomogram provides a practical and highly specific tool for early DKD screening and individualized risk assessment in T2DM patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a leading cause of end-stage renal disease worldwide. Current diagnostic tools such as urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for early detection. More sensitive, noninvasive markers are urgently needed to improve early diagnosis and management of DKD.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with multiple metabolic disturbances, including hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, all of which contribute to DKD progression. Previous prediction models have included conventional risk factors but demonstrated limited specificity and clinical utility. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and serum cystatin C (CysC) have emerged as promising markers of renal function and damage. Lens AGE fluorescence provides a rapid, noninvasive measure of systemic AGE accumulation, while CysC is a more accurate surrogate for glomerular filtration than serum creatinine.

We aimed to establish and validate a nomogram combining routine clinical indicators with lens AGE fluorescence and CysC for early prediction of DKD risk in T2DM patients.

Study design and methods

Study participants

Participant grouping, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and sample collection

-

(1)

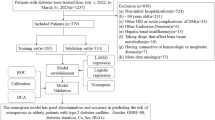

A schematic overview of the patient selection process and overall study design is depicted in Fig. 1. A total of 212 T2DM patients admitted to the Department of Endocrinology at Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital, Fudan University, from November 2019 to February 2024 were selected to construct receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and determine cutoff points for noninvasive lens AGEs and CysC to predict worsening kidney function. According to the “Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease (2021 Edition)”1, patients were divided into a DKD group (31 males, 27 females) and a non-DKD group (99 males, 55 females). Patients were categorized into three groups according to the CKD prognostic risk stratification recommended by the KDIGO 2024 guidelines2. The low-risk category was defined as the mild group (n = 154), the moderately increased risk category as the moderate group (n = 36), and the high- plus and very-high-risk categories were combined and defined as the severe group (n = 22) (Fig. 2).

-

(2)

Reproducibility Validation and Construction of the Nomogram Prediction Model: Patient data collection continued until February 2024, and the sample size was expanded to 2980. Patients who did not meet the study criteria or who demonstrated poor compliance were excluded. After completing relevant examinations and further excluding ineligible patients or those with incomplete clinical data, 868 T2DM patients (536 males, 332 females) were included. The grouping was consistent with the first phase: 644 patients were in the non-DKD group (403 males, 241 females), and 224 were in the DKD group (133 males, 91 females).

A total of 127 candidate variables were initially collected and entered into univariate analyses for screening potential DKD-associated factors: (1) demographic characteristics, including age, sex, smoking and drinking history, and body mass index (BMI); (2) clinical information, such as the duration of T2DM and diabetic microvascular complications, including DKD, diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), and diabetic retinopathy (DR); and (3) medical history, including hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, gout, hyperlipidemia, and fatty liver. Additionally, 48 laboratory indicators, such as blood biochemistry, complete blood counts, liver function tests, kidney function tests, and lipid profiles, were included. (4) Noninvasive lens AGE measurements were dichotomized at 0.306. Consistent with our previously published findings3, we applied the validated lens AGE cutoff of 0.306, which was originally derived through ROC analysis using Youden’s index to define the optimal threshold for identifying DKD.

AGE fluorescence detection was performed by certified and trained medical personnel via a noninvasive lens AGEscan fluorescence detector (provided by Sinocare Inc.), which was used to obtain AGE accumulation levels.

-

(3)

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: According to the “Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetic Kidney Disease (2021 Edition),1” patients were divided into the DKD group (UACR ≥ 30 mg/g and/or eGFR < 60 mL/[min·1.7m2]) and the non-DKD group (UACR < 30 mg/g and eGFR ≥ 60 mL/[min·1.7m2]). Exclusion Criteria: ① Age < 20 or > 70 years; ② type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes, or specific types of diabetes; ③ acute or chronic infections, benign or malignant tumors, hematological diseases, immune disorders, urinary tract stones, non-DKD CKD, or DKD coexisting with non-DKD; ④ fluorescein angiography within the past 6 months, photodynamic drug treatment within the past year, clinical diagnosis of lens opacity (e.g., cataracts), or ocular surface diseases (e.g., dry eye); ⑤ white blood cell count (WBC) > 9.5 × 10^9/L or < 3.5 × 10^9/L; and ⑥ poor patient compliance.

-

(4)

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The procedures were approved by the Ethics Board at Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital, Fudan University (approval no. (2021) (142)). Study participants with a clinical diagnosis of T2DM or DKD provided informed consent. The clinical characteristics of the study participants, including sex, age, and BMI etc. were recorded.

Data collection

Trained surveyors conducted face-to-face interviews via standardized paper-based questionnaires to retrospectively collect relevant data. All questionnaires were distributed, completed, and collected onsite. The data were entered independently by two individuals and cross-verified for accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Sample size considerations: this study used a retrospective design, all eligible patients were included and no a priori sample-size calculation was conducted. Adequacy for multivariable regression was ensured using the events-per-variable (EPV) principle4. A total of 224 DKD events provided > 30 EPV for the seven predictors in the final model, substantially exceeding the minimum requirement of 10 EPV.

The data were analyzed via SPSS 23.0 and R 4.0 software and are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) or medians (interquartile ranges); comparisons between groups were performed via independent sample t tests or nonparametric tests. Categorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and differences between groups were analyzed via the χ2 test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify independent risk factors for DKD. The nomogram was constructed and validated via the rms package in R. The predictive performance of the model was evaluated via the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Calibration curves and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test were used to assess model calibration. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was applied to evaluate the clinical utility of the model.

Results

Construction of ROC curves to identify cutoff values of noninvasive lens AGEs and CysC for predicting worsening kidney function

Group analysis based on CKD prognostic risk stratification recommended by the KDIGO 2024 guidelines

Compared with the mild and moderate KDIGO groups, the severe KDIGO group presented significantly greater noninvasive lens AGE values and CysC levels and significantly lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels (P < 0.05). Compared with the mild KDIGO group, the severe KDIGO group presented significantly greater WBCs, neutrophil counts, platelet counts, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios (NLRs) (P < 0.05). Compared with the mild KDIGO group, the moderate and severe KDIGO groups had significantly greater platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios (PLRs) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). In the KDIGO 2024 and CDS guideline systems, inflammatory markers such as the NLR and PLR were positively correlated with the severity of kidney damage. We hypothesize that elevated AGE levels may directly or indirectly promote systemic chronic inflammation. This raises the question of whether these inflammation-related markers could also be used to assess DKD progression or aid in its diagnosis.

Group analysis based on the CDS guidelines for DKD diagnosis

In the DKD group, noninvasive lens AGE values, CysC levels, WBCs, Neutrophil counts, the NLR, and the PLR were significantly greater than those in the non-DKD group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Pearson correlation analysis of non-invasive lens AGEs and CysC values across domestic and international guidelines

In both the CDS and KDIGO stratification systems, noninvasive lens AGE values were positively correlated with kidney function indicators (r = 0.272 and 0.251, respectively; P < 0.05). CysC was also positively correlated with kidney function indicators in both systems (r values of 0.208 for CDS and 0.420 for KDIGO; P < 0.05).

Logistic regression analysis of CysC and noninvasive lens AGE values between groups

Logistic regression analysis based on KDIGO stratification revealed that patients in the moderate group were 2.97 times more likely (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 1.72–4.22) and 3.63 times more likely (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 2.46–4.80) to develop DKD than those in the mild group were. Patients in the severe group had a 4.21-fold (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 2.88–5.54) and a 12.49-fold (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 3.71–11.23) greater likelihood of developing DKD than did those in the mild group. Logistic regression analysis based on CDS dichotomization revealed that noninvasive lens AGE values and CysC levels in the DKD group were 2.75 times (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 1.50–4.00) and 3.13 times (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 1.91–4.34) higher, respectively, than those in the non-DKD group.

Construction of ROC curves based on noninvasive lens AGEs and CysC

Using the KDIGO 2024 guidelines for risk stratification, the ROC curve indicated that the cutoff value of CysC for predicting worsening kidney function was 1.185 mg/L (AUC = 97.0, sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 86.8%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). When the CDS guidelines were used to categorize patients as diagnosed with DKD or not diagnosed with DKD, the ROC curve indicated that the cutoff value of CysC for predicting worsening kidney function was 1.005 mg/L (AUC = 61.8, sensitivity = 51.8%, specificity = 76.9%, P = 0.009). The cutoff value of noninvasive lens AGEs for predicting worsening kidney function was 2.893 (AUC = 64.6, sensitivity = 66.1%, specificity = 67.3%, P = 0.001) (Fig. 5B).

Construction of a nomogram for DKD

In the first part of the study, the sample size was further expanded. After strict screening of the study population according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1002 patients were initially included. After patients with incomplete clinical data were excluded, a total of 868 T2DM patients were included in the study, including 332 females and 536 males.

Group analysis based on different kidney damage evaluation indicators

Patients were divided into a DKD group and a non-DKD group according to the diagnostic criteria of the CDS guidelines. Among them, 224 patients (25.81%) were classified as having DKD, whereas 644 patients (74.19%) were classified as having non-DKD. The baseline characteristics of the two groups, including demographic characteristics, physical examination results, routine blood test parameters, and biochemical indicators, are shown in Table 1. Patients were divided into three groups according to the CKD prognostic risk stratification recommended by the KDIGO 2024 guidelines, as described in the previous section. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses

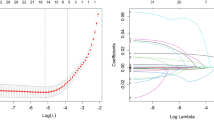

A total of 127 variables were included in the univariate analysis. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed between the DKD and non-DKD groups in terms of AGE risk stratification, age, 25(OH)D, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c, %), systolic blood pressure (SBP), fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels, postprandial BG (PBG) levels, the PLR, the RBC, the WBC, SCr, CysC, and triglycerides (TGs). Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were subsequently entered into a backward elimination stepwise logistic regression model for multivariable predictor selection. All eligible variables were included in the initial full model, and predictors were sequentially removed based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The elimination process continued until no further improvement in model fit was achieved.

Seven variables remained in the final model and were identified as independent risk factors for DKD: SBP (OR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.09), HbA1c (OR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.07–1.43), TG (OR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.04–1.45), CysC (OR = 9.14, 95% CI 1.73–51.35), 25(OH)D (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–1.00), RBC (OR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.26–0.84), and AGEs (≥ 0.306 vs < 0.306, OR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.09–3.32) (Table 3).

Construction of the nomogram

On the basis of the 7 independent risk factors identified through regression analysis—SBP, HbA1c (%), TGs (mmol/L), CysC (mg/L), 25(OH)D (nmol/L), the RBC (10^12/L), and AGEs (dichotomized at 0.306)—we constructed a nomogram for predicting DKD risk in T2DM patients (Fig. 6). Each risk factor is assigned a score proportional to its contribution to DKD risk. A vertical line is drawn from the patient’s value on the corresponding scale to the top points scale to determine the score for each risk factor. All the scores are added to calculate the total score. Using the bottom section of the total points scale, the probability of DKD occurrence can be predicted.

Internal validation of the nomogram and model performance

The accuracy of the nomogram for predicting DKD risk was assessed via a calibration curve from the training set (Fig. 7A). The X-axis represents the predicted DKD risk, whereas the Y-axis represents the actual observed DKD risk. In this study, the ideal model with perfect predictive ability is represented by the diagonal dashed line. The “Apparent” dashed line represents internal validation, whereas the solid line (bias-corrected) represents the externally calibrated nomogram. The results of this study indicate that the constructed model aligns well with the actual observed outcomes. The ROC curve, with an AUC value of 0.809 (95% CI: 0.773–0.845; P < 0.05), is displayed in Fig. 7B. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.690 and 0.800, respectively.

Internal validation of the nomogram and model performance

To validate the DKD model established in this study, 145 T2DM patients from the Department of Endocrinology, Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital, Fudan University, were included for internal validation. The calibration curve for internal validation, which was in good agreement with the ideal calibration curve, is shown in Fig. 8A, whereas the ROC curve, with an AUC value of 0.806 (95% CI: 0.714–0.899; P < 0.05), is presented in Fig. 8B. The sensitivity and specificity were 0.632 and 0.944, respectively.

Clinical utility of the nomogram

The Y-axis represents the net benefit. The diagonal gray line assumes that all patients have DKD, whereas the horizontal black line assumes that no patients have DKD. The red line represents the risk nomogram. The nomogram achieved maximum clinical benefit in both the training set (Fig. 9A) and validation set (Fig. 9B) when the threshold probability ranged from 0.101.00, indicating that the model has broad applicability and high clinical utility.

Finally, a total of 868 T2DM patients were included, with 224 (25.8%) diagnosed with DKD and 644 (74.2%) without DKD. Patients with DKD exhibited higher systolic blood pressure (SBP), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), triglycerides (TG), cystatin C (CysC), and AGE values, while 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and red blood cell (RBC) counts were lower (all P < 0.05).

Seven independent predictors were identified: SBP, HbA1c, TG, CysC, 25(OH)D, RBC, and AGEs. A nomogram incorporating these variables achieved strong discrimination (AUC 0.809 in the training set and 0.806 in the validation set) and good calibration. Decision curve analysis confirmed clinical benefit across a broad range of thresholds.

Discussion

Comparison with previous models

DKD is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide and develops through the long-term interaction of multiple metabolic and hemodynamic factors. Conventional diagnostic markers such as serum creatinine (SCr), eGFR, and UACR are limited by delayed changes, which usually occur after irreversible renal damage has already developed5,6,7,8. In recent years, several nomograms have been proposed to predict DKD risk in T2DM patients9,10,11,12,13,14. These models typically included variables such as disease duration, BMI, blood pressure, HbA1c, triglycerides (TG), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Reported predictive performance was acceptable (C-index ~ 0.76–0.81), but most models relied solely on routine clinical parameters, and few underwent adequate internal or external validation. In contrast, our model is the first to incorporate noninvasive lens AGE values alongside CysC and conventional risk factors, showing robust discrimination (AUC 0.809 in the training set; 0.806 in the validation set) and particularly high specificity (0.944 in the validation set).

Role of cystatin C (CysC)

Cystatin C (CysC) is a critical marker of glomerular damage in diabetic kidney disease (DKD)15. As a low–molecular-weight protein produced by all nucleated cells and released into the bloodstream at a constant rate, CysC is freely filtered by the glomeruli and almost completely reabsorbed and degraded in the proximal tubules with minimal tubular secretion. These physiological characteristics make CysC a highly sensitive indicator of changes in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR)16,17,18,19. Unlike serum creatinine (SCr), CysC levels are not significantly affected by age, sex, muscle mass, diet, or inflammatory status, allowing it to more accurately reflect true renal function. Recently, several studies showed that serum Cysc is a better marker of declining GFR in DM patients than serum creatinine (Scr)20.Most of the evidence came from cross-sectional studies demonstrating that serum Cysc levels in DKD patients were significantly higher when compared to those in DM cases without DKD21,22,23.

Previous studies have shown that CysC demonstrates excellent sensitivity and specificity in the early diagnosis and monitoring of diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive nephropathy, and acute kidney injury24. Consistent with these findings, our study confirmed that CysC maintained high sensitivity and specificity within both the Chinese Diabetic Society (CDS) and KDIGO 2024evaluation frameworks. The incorporation of CysC into our model substantially enhanced its diagnostic accuracy and clinical interpretability. Collectively, these results provide a strong theoretical and empirical basis for the combined use of CysC as emerging diagnostic indicator for DKD risk prediction.

Role of advanced glycation end products (AGEs)

Autofluorescence (AF) of the lens, skin tissue, and serum reflects cumulative glycemic exposure in patients with diabetes to a certain extent25,26. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are irreversible adducts formed through nonenzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and free amino groups on proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. Initiated by aldehyde or ketone groups of glucose and other reducing sugars, these reactions yield stable AGE structures that progressively accumulate in long-lived tissues27. Accelerated AGE generation and deposition promote oxidative stress and inflammatory activation, contributing to chronic tissue injury and metabolic dysfunction28,29.

In diabetes, AGE accumulation induces crosslinking of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, disrupting matrix architecture and promoting renal fibrosis. AGEs can also generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) through interactions with molecular oxygen and transition metals, amplifying oxidative stress and activating downstream inflammatory signaling. Through binding to the receptor for AGEs (RAGE), they trigger NF-κB–mediated transcription of proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines, thereby exacerbating renal damage.

Skin autofluorescence (SAF) provides a widely used noninvasive measure of tissue AGE burden and correlates strongly with biochemical AGE quantification by high-performance liquid chromatography, supporting its analytical validity. However, SAF is influenced by melanin-dependent light absorption, sun exposure, skin pigmentation, epidermal thickness, topical products (such as moisturizers or sunscreens), and dermal vascularity, which may reduce measurement accuracy and limit its clinical applicability.

Lens crystallins are extremely long-lived proteins with minimal turnover, allowing AGEs to accumulate continuously over time and providing a stable reflection of lifetime glycemic and oxidative stress exposure. Lens fluorescence measurement is rapid (approximately 6 s), fully noninvasive, and does not require fasting or other patient preparation. It is applicable to most individuals except those who have undergone cataract extraction or lens replacement surgery.

As independent risk factors for the development and progression of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), AGEs not only predict glycemic deterioration but also the occurrence of diabetic microvascular complications. Renal fibrosis is a central driver of DKD progression toward end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)—characterized by loss of epithelial polarity and adhesion along with acquisition of mesenchymal features—is a key event in this fibrotic process. Experimental evidence suggests that AGEs induce metabolic reprogramming in renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs), shifting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) toward glycolysis and increasing renal lactate production, which contributes to metabolic maladaptation and fibrosis29.Our previous research further confirmed that lens AGEs levels were positively correlated with the occurrence of DKD, and the incidence of DKD in the high lens AGEs group was 2.739 times that in the low lens AGEs group.The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showed that patients with T2DM with a lens AGEs value ≥ 0.306 were likely to have DKD3.

Other independent risk factors

In addition to CysC and AGEs, six conventional variables—SBP, HbA1c, TG, RBC, and 25(OH)D—were identified as independent predictors. Elevated SBP and HbA1c are well-established risk factors for DKD progression30,31,32, underscoring the importance of strict blood pressure and glycemic control. Hypertriglyceridemia has been implicated in renal injury via lipid-mediated inflammation, oxidative stress, and ectopic lipid deposition33,34,35. Reduced RBC counts, reflecting anemia due to impaired erythropoietin production, are frequently observed in DKD and have been linked to accelerated microvascular complications36,37,38. Finally, low 25(OH)D levels have been associated with impaired immune regulation, inflammation, and oxidative stress, all of which promote DKD progression39,40,41,42,43,44. Together, these findings emphasize that DKD results from a multifactorial interplay of metabolic, inflammatory, and hemodynamic factors.

Clinical implications

Our study provides a novel, easy-to-use, and clinically practical nomogram that integrates both traditional and emerging risk factors. The incorporation of noninvasive lens AGE values is of particular significance, offering a rapid, cost-effective, and patient-friendly method for DKD risk assessment. By achieving high specificity, this model reduces the likelihood of overdiagnosis and unnecessary interventions, thereby optimizing clinical resource allocation. In addition, the nomogram can assist clinicians in identifying high-risk individuals for early intervention, personalized treatment, and regular follow-up, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare burden.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, This was a single-center study performed in a tertiary care hospital, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to milder or community-based diabetic populations and external multicenter validation with larger and more diverse populations is required to confirm the generalizability of our findings. Second, lifestyle and behavioral factors—including smoking status, diet, physical activity, and medication adherence—were not systematically collected, although these variables are known to influence DKD risk and may have introduced residual confounding.Third, the cross-sectional design precluded evaluation of causal relationships .Finally, while internal validation showed promising performance, further external validation and prospective studies are warranted.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chinese Diabetes Society Microvascular Complications Group. Guideline for the prevention and treatment of diabetic kidney disease in China (2021 edition). Chin. J. Diabetes Mellitus 13, 762–784 (2021).

Stevens, P. E. et al. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 105, S117–S314 (2024).

Zhang, X.-M. et al. Exploration of noninvasive detection of advanced glycation end products in the lens to screen for diabetic kidney disease. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 892070 (2022).

Riley, R. D. et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m441 (2020).

Kwan, B. et al. Metabolomic markers of kidney function decline in patients with diabetes: Evidence from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76, 511–520 (2020).

Hosseini Sarkhosh, S. M., Hemmatabadi, M. & Esteghamati, A. Development and validation of a risk score for diabetic kidney disease prediction in type 2 diabetes patients: a machine learning approach. J Endocrinol Invest 46, 415–423 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Design of machine learning algorithms and internal validation of a kidney risk prediction model for type 2 diabetes mellitus. IJGM 17, 2299–2309 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Machine learning-based predictive modeling of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes using integrated biomarkers: A Single-center retrospective study. DMSO 17, 1987–1997 (2024).

Ahn, H.-S. et al. Differential urinary proteome analysis for predicting prognosis in type 2 diabetes patients with and without renal dysfunction. IJMS 21, 4236 (2020).

Xi, C., Wang, C., Rong, G. & Deng, J. A nomogram model that predicts the risk of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A retrospective study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 1–9 (2021).

Wang, X., Liu, X., Zhao, J., Chen, M. & Wang, L. Construction of a nomogram-based prediction model for the risk of diabetic kidney disease in T2DM. DMSO 17, 215–225 (2024).

Jiang, W. et al. Establishment and validation of a risk prediction model for early diabetic kidney disease based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 cohorts. Diabetes Care 43, 925–933 (2020).

Shi, R. et al. Nomogram for the risk of diabetic nephropathy or diabetic retinopathy among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus based on questionnaire and biochemical indicators: A cross-sectional study. DMSO 13, 1215–1229 (2020).

Zhou, D., Wei, J., Zhang, T., Shen, F. & Yang, J.-K. Establishment and validation of a nomogram model for prediction of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients with proteinuria. DMSO 15, 1101–1110 (2022).

He, D. et al. The difference between cystatin C- and creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate and risk of diabetic microvascular complications among adults with diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 47, 873–880 (2024).

Zou, Y. et al. Development and internal validation of machine learning algorithms for end-stage renal disease risk prediction model of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 44, 562–570 (2022).

Ding, S. et al. Diagnostic value of the combined measurement of serum HCY and NRG4 in type 2 diabetes mellitus with early complicating diabetic nephropathy. JPM 13, 556 (2023).

Wang, T., Wang, Q., Wang, Z., Xiao, Z. & Liu, L. Diagnostic value of the combined measurement of serum Hcy, Serum Cys C, and urinary microalbumin in type 2 diabetes mellitus with early complicating diabetic nephropathy. ISRN Endocrinology 2013, 1–5 (2013).

Shlipak, M. G., Inker, L. A. & Coresh, J. Serum cystatin C for estimation of GFR. JAMA 328, 883 (2022).

Zhou, B., Zou, H. & Xu, G. Clinical utility of serum cystatin C in predicting diabetic nephropathy among patients with diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res 41, 919–928 (2016).

Aksun, S. A. et al. β2-microglobulin and cystatin C in Type 2 diabetes: Assessment of diabetic nephropathy. Exp. Clinic. Endocrinol. Diabetes 112(04), 195–200 (2004).

Chen, H. & Li, H. Clinical implication of cystatin C and β2-microglobulin in early detection of diabetic nephropathy. Clinic. Lab. 63(2), 241–247 (2017).

Wang, T., Wang, Q., Wang, Z., Xiao, Z. & Liu, L. Diagnostic value of the combined measurement of serum Hcy, serum Cys C, and urinary microalbumin in type 2 diabetes mellitus with early complicating diabetic nephropathy. ISRN Endocrinol. 2013, 1–5 (2013).

Xiong, K. et al. Serum cystatin C for risk stratification of prediabetes and diabetes populations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 17, 102882 (2023).

Belali, O. M. et al. LCZ696 Protects against Diabetic Cardiomyopathy-Induced Myocardial Inflammation, ER Stress, and Apoptosis through Inhibiting AGEs/NF-κB and PERK/CHOP Signaling Pathways. IJMS 23, 1288 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. The role of advanced glycation end products between thyroid function and diabetic nephropathy and metabolic disorders. Sci. Rep. 15, 7202 (2025).

Gao, Y. et al. Study on the relationship between non-invasive measurement of advanced glycation end products in the lens and different renal injury assessment systems in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Chin. J. Pract. Intern. Med. 43, 396–400 (2023).

Oshitari, T. Advanced glycation end-products and diabetic neuropathy of the retina. IJMS 24, 2927 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Lactate drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition in diabetic kidney disease via the H3K14la/KLF5 pathway. Redox Biol. 75, 103246 (2024).

Jiang, Y., Liu, X., Gao, H., Yan, J. & Cao, Y. A new nomogram model for the individualized prediction of mild cognitive impairment in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1307837 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. High normal urinary albumin-creatinine ratio is associated with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, HTN with T2DM, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population: a report from the REACTION study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 864562 (2022).

Atkin, S. L., Butler, A. E., Hunt, S. C. & Kilpatrick, E. S. The retinopathy-derived HbA1c threshold of 6.5% for type 2 diabetes also captures the risk of diabetic nephropathy in NHANES. Diabetes Obesity Metabolism 23, 2109–2115 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Poor control of plasma triglycerides is associated with early decline of estimated glomerular filtration rates in new-onset type 2 diabetes in China: results from a 3-year follow-up study. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 1–8 (2020).

Gong, L. et al. High concentrations of triglycerides are associated with diabetic kidney disease in new-onset type 2 diabetes in C hina: Findings from the C hina C ardiometabolic D isease and C ancer C ohort (4C ) S tudy. Diabetes Obesity Metabolism 23, 2551–2560 (2021).

Afshinnia, F. et al. Increased lipogenesis and impaired β-oxidation predict type 2 diabetic kidney disease progression in American Indians. JCI Insight 4, e130317 (2019).

Wang, Z.-S. et al. Red blood cell count as an indicator of microvascular complications in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. VHRM https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S43211 (2013).

Sun, W. et al. Increased risk of vascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease. BMC Endocr Disord 24, 235 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Red blood cell count and cystatin C as the specific biomarkers for diabetic retinopathy from diabetes mellitus: A case–control study. Sci Rep 14, 29288 (2024).

Zheng, X. et al. Vitamin D is involved in the effects of the intestinal flora and its related metabolite TMAO on perirenal fat and kidneys in mice with DKD. Nutr. Diabetes 14, 42 (2024).

Liyanage, P., Lekamwasam, S., Weerarathna, T. & Liyanage, C. Effect of Vitamin D therapy on urinary albumin excretion, renal functions, and plasma renin among patients with diabetic nephropathy: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J. Postgrad. Med. 64, 10–15 (2018).

Domazetovic, V., Iantomasi, T., Bonanomi, A. G. & Stio, M. Vitamin D regulates claudin-2 and claudin-4 expression in active ulcerative colitis by p-Stat-6 and Smad-7 signaling. Int J Colorectal Dis 35, 1231–1242 (2020).

Yu, M. et al. Vitamin D receptor inhibits EMT via regulation of the epithelial mitochondrial function in intestinal fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100531 (2021).

Souza, C. S. et al. Vitamin D deficiency contributes to the diabetic kidney disease progression via increase ZEB1/ZEB2 expressions. Nutr. Diabetes 13, 9 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Quercetin alleviates acute kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. J. Adv. Res. 28, 231–243 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (No. 202140345) and Shanghai Municipal Key Discipline (2024ZDXK0016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.-L.J., J.L., and M.-X.Y. designed the study. L.-L.J., Y.-H.H., Y.G., and T.P. collected the data. J.L., X.-D.Z., and C.-H.Z. analyzed the data. Z.-X.Z. provided technical support. L.-L.J., J.L., and M.-X.Y. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lu-Lu Jin and Jun Liu: First authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, LL., Liu, J., Huang, YH. et al. A nomogram prediction model incorporating noninvasive lens AGEs and conventional biochemical indicators for assessing and predicting diabetic kidney disease. Sci Rep 16, 3653 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33770-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33770-5