Abstract

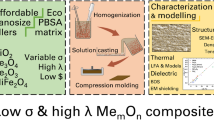

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) remains a critical challenge for modern electronic systems, driving the need for lightweight materials with efficient shielding capabilities. In this work, Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nano-fillers were synthesized via a co-precipitation route and incorporated into a poly(di-allyl phthalate) (PDAP) matrix to produce composite films with tunable dielectric–magnetic coupling. Structural analyses confirmed the uniform decoration of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on RGO sheets and their homogeneous dispersion within the PDAP network. The calculated electromagnetic parameters (ε′ ≈ 12, ε″ ≈ 4, µ′ ≈ 1.3, µ″ ≈ 0.3 at 10 GHz) reveal strong dielectric and magnetic loss channels that support an absorption-dominated shielding mechanism. The optimal composite (PMR20) achieved a total shielding effectiveness of ~ 31.5 dB across the X-band, corresponding to > 99.9% attenuation of incident radiation, with SEA contributing the major portion of the overall SE. The synergy between conductive RGO pathways, magnetic relaxation of Fe3O4, and interfacial polarization within PDAP underpins the enhanced attenuation behavior. This study demonstrates PDAP as a promising and underexplored thermosetting host for hybrid EMI shielding materials, offering a platform for lightweight and high-performance electromagnetic protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to rapid advancements in digital technologies and electronic network infrastructure in recent years, smart urban architecture is rapidly developing, relying heavily on sensing technology and wireless communication networks1. As a result of these developments, however, a significant problem concerning electromagnetic interference (EMI) has emerged and is growing in terms of the extent of its influence on the operation of electronic equipment2, a form of electromagnetic pollution that will impair the functioning of many electronic devices and reduce their operating efficiencies3 unless a mitigation strategy such as the use of shielding materials is employed3. Beyond reducing the effects of EMI, sophisticated materials engineering also enhances the reliability and life expectancy of all electronic architectures4. Metallic alloys and compounds have traditionally represented the most common choice of materials used for EMI shielding5; unfortunately, they represent a limited class of materials because of their high mass density, susceptibility to corroding processes, and costly manufacturing process5. The properties of carbon based materials present an attractive alternative with respect to these limitations as they possess a high level of resistance to corrosion, low mass density, high levels of electrical conductivity, and excellent thermal stability6. Therefore, due to their favorable properties related to cost, performance, and efficiency in microwave absorption, these materials can be utilized to design lightweight shielding structures7. There are two primary mechanisms that provide EMI shielding: (i) reflection which relies upon electrical conductivity to absorb the electric field components of electromagnetic waves and attenuate them and (ii) absorption which is provided by magnetic materials that convert the magnetic field components of electromagnetic waves into heat8. While conventional shielding relies on heavy metal matrices, polymer-based nano-composites have emerged as attractive candidates because of their low weight, flexibility, corrosion resistance, and ease of fabrication9. Of all the other electrically-conductive fillers that have been studied such as carbon black, carbon nanotubes, carbon fibers, graphite, graphene, and reduced graphene oxide (RGO)10 graphene has attracted the most attention because of its unique combination of physical properties including electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties11,12; and because it is considered to be one of the thinnest, strongest nanomaterials available13. The SE of graphene-based materials can be enhanced by modifying their electromagnetic properties through adjusting both dielectric and magnetic properties of these materials. The adjustment of dielectric and magnetic properties are typically achieved by adding functionalized nanoparticles onto the surface of graphene sheets, such as Fe3O4 or BaTiO3, in order to modify permittivity and permeability14,15. Several studies have reported graphene-enhanced polymer composites exhibiting strong absorption-dominated shielding performance. For example, Wang et al. demonstrated that graphene/epoxy composites could achieve > 30 dB shielding in the X-band through enhanced dipole polarization and percolated conductive pathways16. More recently, hybrid graphene systems combining dielectric and magnetic components have shown superior performance due to synergistic loss mechanisms. Katheria et al. integrated Fe3O4 nanoparticles onto graphene sheets to produce a magnetic–conductive hybrid that reached 35–40 dB in the X-band17. Comparable results were obtained by Wei et al. using Fe3O4@rGO within polyurethane, achieving enhanced SEA values driven by magnetic relaxation18. Magnetic fillers used in EMI shielding include Ni nanowires, permalloy alloys, ferrites, and spinel oxides19, each offering distinct magnetic loss mechanisms such as natural resonance and eddy-current damping. Fe3O4-based hybrids are particularly attractive due to their high stability, low cost, and strong magnetic relaxation, making Fe3O4@RGO a competitive class of magnetic–conductive fillers20. Fe3O4 nanoparticles are considered to be among the best candidates for use due to their strong spin-polarization at room temperature, suitable magnetic behavior, low toxicity, and good chemical compatibility with polymer matrices21,22. Furthermore, Fe3O4 nanoparticles show a skin depth effect and moderate electrical conductivity which ensures the good absorption of the electromagnetic radiation22. The synergistic effect of the RGO together with the Fe3O4 enhances this electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding due to the effect of the electrical conductivity of the RGO phase and the magnetic loss due to the Fe3O4 phase23. For effective electromagnetic attenuation it is essential that the polymer composites have sufficient electrical conductivity and permeability along with proper structure retention which can be achieved by the addition of conducting and magnetic fillers to the polymer host24. Increase in filler concentration leads to a corresponding increase in EMI shielding until the (optimum) concentration is obtained when any further loading will tend to lessen the structural integrity of the composite25. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nanostructures for EMI shielding due to their combined conductive and magnetic loss characteristics. Fe3O4 nanoparticles introduce magnetic dipole resonance and domain-wall relaxation, while RGO provides conductive pathways for dielectric and interfacial polarization losses17. Several reports have shown Fe3O4@RGO-based polymer composites achieving moderate-to-high shielding performance in the X-band, confirming the relevance of this hybrid design26. However, most studies have focused on flexible matrices such as epoxy, silicone, or polyethylene-based systems, while thermosetting polyesters such as PDAP remain largely unexplored27. These gaps highlight the need to investigate Fe3O4@RGO hybrids within new polymer hosts and to optimize filler ratios to achieve synergistic absorption-dominated EMI shielding. Some of the Fe3O4@RGO/polymer composites have been made and the literature shows that most of the work has been done on their applications in epoxies and polyurethanes which are known to have poor conductivity and interface adhesion. In contrast the poly (di-allyl phthalate) (PDAP) polymer has a rigidity due to cross-linked ester structure and has been shown to have the ability to improve the interfacial polarizability and dielectric enhancement. However, its potential as an EMI shielding matrix remains largely unexplored. PDAP was selected as the polymer host due to its high thermal stability, cross-linked structure, and strong dielectric strength, which are advantageous for EMI shielding materials. The ester and aromatic groups in PDAP exhibit good compatibility with Fe3O4@RGO hybrids through hydrogen bonding and dipole–dipole interactions with residual hydroxyl, epoxy, and carbonyl functionalities on RGO and Fe3O4 surfaces. Such interfacial affinity enhances nano-filler dispersion and promotes interfacial polarization, which contributes to improved dielectric losses and absorption-dominated shielding. Therefore, the present study aims to synthesize and characterize Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites and evaluate their electromagnetic performance within the X-band frequency range (8–12 GHz). The novelty of this work lies in employing PDAP as a new polymer host to exploit its cross-linked ester structure for improved interfacial interactions with Fe3O4@RGO hybrids. The study demonstrates how the magnetic–dielectric coupling between Fe3O4 and RGO within PDAP leads to efficient absorption-dominated EMI shielding behavior, offering a new material platform for lightweight and high-performance EMI protection.

Theory of EMI shielding

The ratio of the electric or magnetic field intensity before and after transmission through a shielding material defines the shielding effectiveness (SE), which can be expressed as shown in Eq. 128.

where P, E, and H represent the electromagnetic wave power, electric field, and magnetic field, respectively. Subscripts T and i denote transmitted and incident waves. Shielding effectiveness is dependent on many different variables; primarily the amount of physical separation between the source of the interference and the shielded area, the thickness of the shield, the frequency being shielded against, and the electric and magnetic characteristics of the material used to construct the shield. Shielding effectiveness is generally quantified in terms of Decibel levels (dB). Variables that affect the magnitude of EMI reduction include wavelength, the proximity of the interference source to the shielded area, the physical dimensions and inherent properties of the shielding material. There are three basic mechanisms that govern how electromagnetic waves interact with shielding materials. As indicated in Fig. 1, when an electromagnetic wave enters into a shielding material some of it will be reflected off the front surface, a portion of it will be absorbed by the material itself, and a portion of it may exit the material and reflect off the rear surface. In accordance with this behavior, the total shielding effectiveness (SET) of the material can be calculated based upon a combination of the reflection loss (SER), the absorption loss (SEA), and a correction factor (M) which represents the number of times that the remaining portions of the electromagnetic wave internally reflects. This relationship is outlined in Eq. 2:

When absorption loss exceeds a value of 10 dB, then the contribution of the multiple reflection component (M), is reduced to negligible amounts and can be simple computational models for plane waves, current induced in conducting media are lost as heat rather than contributing to additional reflections29. Reflections occur due to impedance discontinuities at the interface of the incoming wave and the shield surface. As SEA approaches values of approximately 6 dB, and beyond, reflection correction factors become irrelevant especially at low frequencies (less than 20 kHz)30. Alternatively, shielding characteristics can be evaluated using two-port Vector Network Analyzer methods, where the reflection and transmission characteristics of the electromagnetic wave are determined by S-parameters. When a wave is propagated from Port 1 to Port 2, it interacts with the shield through reflection, absorption and transmission mechanisms; therefore, the S11 and S21 represent the reflected and transmitted portions of the incident wave, respectively31. Consequently, the relationships between transmittance (T), reflectance (R), and absorbance (A) and their corresponding S-parameters are expressed through Eqs. (3–5)32:

Here, A represents the absorbed portion of the electromagnetic power. Even when multiple reflections between the front and back interfaces are minimal, the fraction of the effective incident energy entering the shield is determined by (1 – R). Consequently, the effective absorption can be expressed as shown in Eq. 633:

Using power balance relationships, the reflection (SER), absorption (SEA), and total shielding (SET) effectiveness can be calculated in terms of R, T, and A as shown in Eqs. (7–9):

Experimental work

Materials

PDAP (Average M.W. 65000 (GPC), purity 69%), Graphite powder (G) (99.5%), Ammonium iron (II) sulfate hexahydrate (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·6H2O (Mw − 392.14 g/mol, purity 98.5%), Iron (III) chloride FeCl3.6H2O (Mw − 270.30 g/mol, purity 98.5%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99.5%), Potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 98.5%), Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), Sodium Borohydride ( NaBH4, 99.5%), Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36%) and Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) were obtained from Alpha Chemicals, Haryana; India. All chemicals were used as purchased without further treatment or purification.

Preparation of reduced graphene oxide (RGO)

The preparation of graphene oxide (GO) involved oxidizing graphite powder via a modified Hummers’ method34. During the process, the graphite powder was first mixed into concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) with ongoing agitation, after which potassium permanganate (KMnO4) was introduced gradually while ensuring the mixture stayed below 20 °C to avoid excessive heat and over-oxidation. Deionized water was then added step by step to dilute the reaction, followed by the careful incorporation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) to halt the oxidation, which produced a vivid yellow hue indicative of GO formation. The suspension was subjected to several washes with distilled water and ethanol, as well as 5% hydrochloric acid until the pH of the solution was neutral. The residue was filtered off and dried at 60 °C giving the pure GO. The exfoliation of dried graphite oxide was obtained by ultra-sonication for three hours giving a uniform suspension of GO dispersions35. A chemical reduction of this suspension of GO was then carried out with sodium borohydride or NaBH4 resulting in the synthesis of reduced graphene oxide (RGO) which has excellent electrochemical properties with a regenerated framework of π-conjugated units36.

Synthesis of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nanocomposites

The preparation of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4@RGO nanocomposites was completed using a chemical co-precipitation method37 for both processes. The general process involved a solution containing a combination of ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6 H2O) and ammonium iron (II) sulfate hexahydrate ((NH4)2Fe(SO4)2⋅6H2O), which was created by dissolving these two compounds in 25 mL of DI water with a molar ratio of 2:1. This solution was then stirred magnetically for several hours until the temperature reached 120 °C and then slowly added to 1 L of 1.5 M NaOH solution that contained a variable amount of RGO (0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt%). At the time of mixing of the solutions, there was an immediate formation of a black precipitate indicating successful co-precipitation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles onto RGO sheets. After completion of the reaction, all of the products were separated from solution by use of a magnetic separator; washed 3 times each with ethanol and DI water; and dried under vacuum at 60 °C overnight. These resulting nanocomposites received designations of Fe3O4, MR10, MR20, MR30, and MR40, aligned with RGO contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, respectively.

Synthesis of Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites

The Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites were fabricated through a solvent-assisted blending method to ensure homogeneous distribution of the hybrid filler and to avoid premature crosslinking of the PDAP resin. A predetermined amount of Fe3O4@RGO powder was dispersed in 40 mL acetone using probe sonication (576 W, 25 min). The PDAP resin was added gradually under magnetic stirring and mixed for 1 h to ensure complete wetting of the filler. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure, and the resulting viscous mixture was poured into Teflon molds and cured at room temperature for 24 h. Four composite samples were prepared with different hybrid filler loadings and are denoted as PMR10, PMR20, PMR30, and PMR40 corresponding to 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt% Fe3O4@RGO, respectively. It is important to clarify that PDAP is a thermosetting resin and cannot be processed by melt blending due to the risk of in-situ thermal crosslinking during heating. For this reason, no melt-processing was used in this study. All mixing steps were performed at room temperature using a solvent-assisted blending method, ensuring that PDAP remained un-crosslinked during filler incorporation. Crosslinking occurred only during the final curing stage inside the mold, thereby avoiding any premature polymer network formation during composite preparation.

Comprehensive structural, morphological, DC electrical conductivity and electromagnetic characterization

The physical and electromagnetic properties of the developed composites were evaluated through the use of several analysis techniques to characterize their structural, morphological, magnetic, and electromagnetic characteristics. The images obtained from Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of the developed composites were taken on a Thermo Scientific Talos F200i system (USA) that produced images in a voltage range of 20 to 200 kV and resolutions of less than or equal to 0.10 nm. The samples for TEM characterization were prepared by suspending a diluted composite dispersion onto a carbon coated ultrathin copper grid, followed by air-drying the samples at room temperature. Patterns of X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) were collected using a PANalytical X’Pert Pro Diffractometer (UK) that used both Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54Å) and Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71Å). Raman Spectroscopy measured the wavenumbers of the 400–3000 cm−1 region at a resolution of 4 cm−1, using a Bruker SENTERRA II spectrometer (USA) equipped with a 785 nm laser at 10mW. FT/IR Spectra were collected to determine the chemical bonding between the PDAP matrix and the Fe3O4@RGO fillers using a Nicolet iS50 instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA) that provided a resolution of 0.09 cm−1 over the 15–27,000 cm−1 range. Magnetic attributes such as Saturation Magnetization (Ms), Magnetic Remanence (Mr), and Coercivity (Hc) for the Fe3O4, MR10, MR20, MR30, and MR40 specimens were determined by Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM, Model UP200S, Hielscher, Germany). Surface morphology and the distribution of the filler material within the polymer matrix were inspected by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, ZEISS EVO 15, Carl Zeiss, Berlin, Germany). The DC electrical conductivity (σ) of the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites was measured using a standard four-point probe station (Keithley 2400 SourceMeter coupled with a Jandel RM3000 Four-Point Probe System). The measurements were performed in accordance with ASTM F76-08 (Standard Test Method for Measuring Resistivity of Thin Conductive Materials). Rectangular specimens (typically 20 × 10 × 3–5 mm3) were cut from the cured composite sheets. A constant current was applied through the outer probes while the voltage drop between the inner probes was recorded. Each measurement was repeated three times at different surface positions to ensure reproducibility, and the average DC conductivity was calculated according to the standard geometric correction factors specified in ASTM F76-08. The DC conductivity values (σ) were obtained for all composite formulations: PMR10, PMR20, PMR30, and PMR40. These values were later correlated with the EMI shielding performance and with the calculated dielectric parameters in the Results and Discussion section. The electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding capability of the developed composites was assessed in the X-band frequency range (8–12 GHz) using a vector network analyzer (N9918A Field Fox, Agilent Scientific, USA). Rectangular-shaped samples measuring 22.86 × 10.16 mm2 were prepared to fit the WR-90 waveguide setup. The recorded scattering parameters included S11, S21, S22, and S12, from which the total shielding effectiveness (SET), reflection loss (SER), and absorption loss (SEA) were calculated. Three sets of measurements were performed for each specimen for consistency purposes, the results shown represent the average value of the three measurements; the uncertainty of the measured quantities of the EMI shielding efficiency and electrical conductivity is < ± 3%. A full NRW retrieval from S-parameters was not available with the current instrumentation; therefore, an analytical NRW-based approach was employed, where the complex permittivity and permeability were calculated from EMI shielding data using classical Maxwell relations.

Results and discussion

Filler characterization

X-ray diffraction analysis

The XRD patterns in Fig. 2 show that both RGO and as-received graphite produced strong peaks associated with their respective d-spacings. Graphite gave rise to a large signal at 26.6° (002) showing a d-spacing of approximately 3.5 Å. Following the oxidation process, a very weak peak was observed at 27.32° (d = 3.57 Å) demonstrating expanded d-spacing due to the inclusion of H2O molecules between adjacent layers and the introduction of O-functional groups on the graphite layers38.

The interlayer spacing (d) was calculated using Bragg’s law, as indicated in Eq. (10):

Where λ is the wavelength of the X-rays; θ is the angle of diffraction; d is the spacing between crystallographic planes39. Using Bragg’s Law, we determined the d-spacing for unmodified graphite to be 3.41Å at 2θ = 26.4°. We also determined that a large decrease in intensity of the (002) peak at 2θ = 27.32° resulted from the chemical reduction of graphene oxide using sodium borohydride, which indicated the partial restoration of the conjugated graphitic structure. The d-spacings were equivalent for both graphite and reduced GO, indicating that the majority of oxygen containing functional groups were removed from the RGO via the modification of the Hummers oxidation process40. In Fig. 3, we have provided the XRD patterns for pristine Fe3O4 nanoparticles, RGO and the Fe3O4@RGO nanocomposites (MR10, MR20, MR30, and MR40). There is a broad diffraction pattern located near 2θ = 25° that corresponds to the (002) plane of RGO, and there is a strong increase in intensity of this peak as the amount of RGO increases to reach an extreme in the MR40 sample. Conversely, the pure Fe3O4 has sharp diffraction peaks that indicate no shift in the lattice parameters relative to the original spinel structure41. Notable peaks emerged at 2θ values of 31°, 37°, 43°, 57°, and 65°, linked to the (220), (311), (400), (511), and (440) planes of Fe3O4, respectively. These characteristics indicate that the material is an inverse spinel magnetite (JCPDS card number 19–0629). The peaks’ loss of clarity and strength as the amount of RGO increased suggested that there were reduced crystalline features due to strong interactions between RGO layers and structured Fe3O4 domains42, such that a determination of the average crystallite dimension (L) could be made by applying Scherrer’s equation as defined in Eq. 11:

where L is the crystallite size (nm), k is the shape factor (~ 0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength (nm), and β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the most intense peak43. The observed broadening of Fe3O4 peaks in the composites further supports the nanoscale crystallite dimensions and the successful hybridization of Fe3O4 with RGO, yielding well-dispersed magnetic domains within the conductive carbon network.

The calculated crystallite domain sizes of all the samples are shown in Table 1. Pure Fe3O4 has the largest average crystallite size (29.6 nm) which progressively decreases, due to the increased RGO content, down to ∼5.44 nm for MR40 composite. This considerable reduction in crystallite size at higher RGO loadings suggests the incorporation of RGO limits the growth and aggregation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles during synthesis. The decrease in crystallinity and crystallite size of the material is indicative of the strong interfacial interactions of Fe3O4 with the conductive RGO sheets, which serve as effective nucleation and confinement sites for the feeder nanoparticle growth. In effect it is shown that the addition of RGO at higher concentrations promotes dispersion of the smaller particles, resulting in a greater degree of structural homogeneity of the hybrid composite, as indicated by the broadening of the observed XRD peaks.

Raman spectroscopy analysis

The Raman Spectra are displayed in Fig. 4 for graphite as well as reduced graphene oxide (RGO) as well as the spectra show the typical 3 bands associated with sp2 hybridized carbon graphitic material; namely the 2D, D, and G bands. The G Band at 1570 cm−1 is indicative of the in-plane motion of sp2 hybridized carbon atoms in the hexagonal structure of graphite44,45 and represents the universal signature of sp2 carbon systems including graphite, CNTs, fullerenes, and amorphous carbon. Upon chemical reduction, the G Band in RGO shifts slightly to 1574 cm−1 and diminishes significantly in intensity as an indication of the incomplete recovery of sp2 domains. The D Band, indicative of breathing motions of sp2 carbon rings that are activated via lattice disorder or sp3 defect formation, is located at 1339 cm−1 in graphite and at 1344 cm−1 in RGO46, and indicates increased defect and boundary region creation during the oxidation and reduction stages as evidenced by the incomplete removal of oxygen containing functional groups. Graphite exhibits the 2D band at 2723 cm−1 while RGO exhibits the same band at 2711 cm−1 but with increased symmetry and strength indicating the emergence of a few layered sheets. The I2D/IG band intensity ratio provides a qualitative estimate of graphene layer thickness47; according to this ratio, the original graphite consists of > 20 layers, in contrast to the estimated 7–9 layers present in the RGO, which is consistent with the observed upward shift in the 2D band position. The migration of the 2D band from 2705 cm−1 (single layer) to 2730 cm−1 (20 layers) further supports the multi-layered nature of the prepared RGO48.

In addition to XRD measurements, Raman spectroscopy was performed to evaluate structural properties of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nanocomposite samples. An excitation wavelength of 633 nm was utilized to prevent oxidation or phase transitions that could occur upon measurement due to the relatively high energy level. The Raman spectrum of pure Fe3O4 nanoparticles (see Fig. 5a) showed five unique bands corresponding to the T2g(1), Eg, T2g(2), T2g(3), and A1g vibrational modes of magnetite located at 195, 304, 462, 541, and 665 cm−1, respectively. In comparison, the Raman spectra of maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) are generally described as having three bands at 352, 501, and 703 cm−1; none of these bands were observed in the data obtained from this study, further supporting the conclusion that magnetite was present in the sample49,50. In addition to observing the presence of RGO using the D and G bands at 1363 cm−1 and 1592 cm−1, respectively, see Fig. 5b, the presence of magnetite was verified through the observation of an A1g band at 665 cm−1, which is indicative of the presence of magnetite on the surface of RGO51. The relative intensities of the D and G bands of RGO decreased progressively as the proportion of Fe3O4 increased in the composites. Additionally, the positions of the D and G bands shifted slightly to lower wavenumbers (blue-shifted). These position shifts can be attributed to the significant interaction occurring at the interface between the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the RGO framework resulting in localized strain and altered electron–phonon coupling in the sp2 system52. These results collectively demonstrate the successful formation of RGO hybrids with attached magnetite particles, exhibiting strong structural correlation and proximity between the magnetic and conducting components, thus providing additional support for the enhanced electromagnetic performance of the composites.

Transmission electron microscopy

The transmission electron micrographs shown in Fig. 6 present the morphology of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, RGO and the various Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nanocomposite architectures produced using different ratios of RGO to Fe3O4 (MR10, MR20, MR30 and MR40). In addition to illustrating the structural features of both the Fe3O4 and RGO components, TEM was used to provide morphological evidence for the formation of hybrid nanostructures through the interfacial association of the two materials. In particular, TEM images of the Fe3O4 component presented in Fig. 6a demonstrate that the particles are quasi-spherical in shape and have a narrow size distribution with a mean diameter of approximately 10 ± 5 nm; this is indicative of efficient control over nucleation and particle growth during the synthesis of the iron oxide via the co-precipitation method. The TEM image of RGO depicted in Fig. 6b provides further support for the crumpled and layered morphology commonly associated with reduced GO and demonstrates that it has been successfully exfoliated into individual sheets during the production of GO. The presence of uniformly distributed Fe3O4 nanoparticles attached to the surface of the RGO sheets (Fig. 6c–f) supports strong interfacial interactions between the magnetic material and the carbon-based electrical conductor and serves to act as attachment sites for other Fe3O4 nanoparticles, thereby inhibiting agglomeration of these entities and facilitating their uniform dispersion within the composite material structure53.

Vibrating sample magnetometer analysis

Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM) was employed to examine the magnetic characteristics of Fe3O4 alongside the Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nanocomposites (MR10, MR20, MR30, and MR40) at a temperature of 298 K. Figure 7 displays the hysteresis loops obtained with each sample, while Table 2 shows the associated magnetic parameters of each sample; namely saturation magnetization (Ms), remanent magnetization (Mr), and coercivity (Hc) values. Hysteresis loops of all the samples recorded were narrow and symmetrical which are characteristics of ordinary soft magnetic materials54. The saturation magnetization of the pure Fe3O4 sample was the highest measured (Ms = 47.145 emu/g) with a gradual decrease in value noted with an increase in RGO content having values of 35.25, 24.11, 13.86 and 11.00 emu/g for MR10, MR20, MR30 and MR40 respectively. This systematic decrease in Ms values would be attributed to the diamagnetic effect of RGO which in effect decreases the total magnetic moment of the composite materials through a decrease in the relative amount of magnetic Fe3O4 per mass unit55. Similarly the remanent magnetization (Mr) decreased from 2.15 emu/g in the pure Fe3O4 to values of 0.887, 0.658, 0.524 and 0.198 emu/g with MR10, MR20, MR30 and MR40 respectively. The decrease in Ms and Mr noted as the RGO fraction was increased in the composites indicates the strong coupling present at the magnetic–nonmagnetic interface between the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the RGO sheets not allowing for unlimited spin orientation and weakening of the magnetic exchange interactions. All of the samples exhibited very low coercivity value (Hc < 100 Oe) indicating there is low magnetic hysteresis and the magnetization is reversible. Such behavior is characteristic of superparamagnetic materials, in which thermal effects at room temperature are sufficient to randomize the magnetic moments in the absence of an applied magnetic field56. The combination of soft magnetic behavior, high saturation magnetization, and negligible remanence makes the Fe3O4@RGO hybrids particularly suitable for applications that require rapid magnetic response and efficient electromagnetic absorption, such as EMI shielding and microwave attenuation.

Composite characterization

FT/IR analysis

To examine the chemical composition of PDAP along with potential interactions involving Fe3O4@RGO fillers and the PDAP framework, Fourier-transform infrared (FT/IR) spectroscopy was utilized. Figure 8 presents the FT/IR spectra for unmodified PDAP as well as the exemplary composite PMR20. In the case of pure PDAP, key absorption signals emerged at 3427 cm−1, linked to O–H stretching vibrations; prominent bands at 3156 and 3123 cm−1 related to aromatic C–H stretching, whereas those at 2956 and 2923 cm−1 connected to aliphatic C–H stretching modes. A distinct, robust peak at 1717 cm−1 corresponded to C=O stretching within ester connections, and the signal at 1600 cm−1 aligned with aromatic C=C stretching vibrations. Signals from C–H deformation developed in the range 1451–1373 cm−1 along with C–O stretching from the ester units in the range 1259–1039 cm−157. The FT/IR data for PMR20 paralleled the significant bands observed in pure PDAP, but with only slight shifts of the peak positions in some regions, near 924, 1690 and 3300 cm−1 being particularly affected. The absence of new bands and great reductions in the existing ones suggest that no chemical reactions have occurred between the polymer structure and the Fe3O4@RGO fillers. The changes in the position of the bands must therefore be due to some physical interactions and hydrogen bonding with oxygenated functional groups present on the surface of the Fe3O4@RGO and the ester groups or hydroxyl groups of the PDAP58. This constitutes evidence that the nanoparticles of Fe3O4@RGO become physically incorporated into the polymer matrix of PDAP with effective distribution owing to relatively weak interfacial interactions but not by covalent bonding. The similarity of the spectral properties of the PDAP indicated the stability of the structural characteristics of the backbone of the polymer, while the relatively small displacements of the band positions provided the evidence of interfacial polarization effects which are advantageous for EMI shielding purposes. Furthermore, the FT/IR data confirmed the presence of functional groups associated with the phthalate and allyl residues of the PDAP. Signals at 1725, 1275 and 1125 cm−1 corresponded to C=O and C–O–C stretching vibrations having their origin in the phthalate units, while the C=C stretching in the allylic group was around 1645 cm−1 which was accompanied by C=C vibrations in the aromatic rings at around 1598 cm−1. The observed decrease in intensity of 1645 cm−1 band during the polymerization process of di-allyl phthalate indicated the involvement of allyl groups and established the presence of cross-linked polymer systems. A slight shift in the C=O stretching band of PDAP and the appearance of broadened O–H features indicate hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions between PDAP chains and Fe3O4@RGO hybrid surfaces. This confirms the good interfacial compatibility between the matrix and the hybrid filler. Finally, the results of the FT/IR studies provided evidence for the successful formation of PDAP-derived nanocomposites which were characterized by significant physical interaction between the Fe3O4@RGO fillers and the polymer system which provided for uniform distribution and excellent interfacial interaction.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

The results from the characterization via scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis of the pristine PDAP polymer and its consequent use in Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP nano-composites are given in Fig. 9. The surface of the pristine PDAP polymer (Fig. 9a) reveals a smooth and homogeneous surface structure with no evident disconnected particle structures which are indicative of the homogeneous nature of the pristine bulk polymer matrix. The presence of Fe3O4@RGO fillers (Fig. 9b–d) gives a decidedly different picture to the surface morphology of the materials. The Fe3O4 nano-particles appear to be anchored upon the wrinkled RGO nano-sheets and appear to be well distributed throughout the PDAP matrix giving rise to connected conductive–magnetic interpenetrating streaks in the polymeric bulk. The effect of this component of intermixing is that the structures of microstructure of the polymer is rendered more complex and an efficient interface for the formation of charge and dipole polarization is enhanced. At the higher loadings of fillers some partial aggregation of the nano-particles and localized clustering occurs particularly in the case of the higher concentrations of Fe3O4/RGO combinations. These morphological holds are in correlation with the lowered-crystallinity of the X-ray results and are borne out by the knowledge that ample amounts of additions of fillers limits the primal capability of the matrix to evenly hold the nano-particles. The Fe3O4 nano-particles are also still well distributed upon the surfaces of the RGO to the extent resulting in avoidance of forms of too large agglomeration and affording benefit of strong interfacial adhesion between the polymeric chains and the hybrid fillers. This dual contribution uniform dispersion of conductive RGO sheets and magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles facilitates the formation of continuous conductive pathways and magnetic loss centers, thereby improving both reflection and absorption mechanisms in EMI shielding. Among all compositions, the composite containing 20 wt% RGO (PMR20) displays the most homogeneous morphology with minimal aggregation, correlating directly with its superior shielding effectiveness compared to other loading ratios.

Electrical conductivity and EMI shielding effectiveness

The EMI shielding effectiveness (SE) of the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP nanocomposite depends upon both the composition of the Fe3O4@RGO hybrid filler and the loading level of the hybrid filler within the PDAP matrix. To identify the appropriate composition, two separate sets of experiments were performed. In the first set, the amount of hybrid filler within the PDAP was held constant as the proportion of RGO to Fe3O4 within the hybrid filler varied. In the second set, the RGO: Fe3O4 composition that resulted in the highest SE was then used to maximize the SE by optimizing the amount of hybrid filler within the PDAP. SER of each sample vs. the frequency of the radiation is depicted in Fig. 10A. Both a dependence on the frequency and the composition of the hybrid filler are evident. The average SER values for PMR10 and PMR20 were 9.9 dB and 11.4 dB, respectively. The average SER values for PMR30 and PMR40 were 6.7 dB and 3.6 dB, respectively. These trends in SER can be attributed to changes in the shape of the hybrid filler particles and the interactions between the Fe3O4 particles and the RGO sheets and the radiation. As illustrated in Fig. 10B, the SEA as a function of the frequency of the radiation increases with increasing RGO content and is clearly dependent on the composition of the hybrid filler. The average SEA values for PMR10 and PMR20 were 10.7 dB and 20.1 dB, respectively. The average SEA values for PMR30 and PMR40 were 21.3 dB and 22.5 dB, respectively. The increase in SEA with RGO content is due to the improvement in electrical conductivity of the Fe3O4@RGO composites which enhances the polarization of the electric field and the losses at the interfaces within the PDAP. The total shielding effectiveness (SET) as a function of the frequency of the radiation from 8 to 12 GHz is shown in Fig. 10C. The average SET values for PMR10, PMR20, PMR30 and PMR40 were 18.9 dB, 31.5 dB, 28.4 dB and 26.3 dB, respectively. The highest value of SE was obtained for PMR20 with an average SET of about 31.5 dB. This is likely due to the synergy of the effects of the Fe3O4 (which results in a magnetic loss mechanism and contributes to the reflection of the incident EM waves) and RGO (which contributes to the absorption of the incident EM waves through its high electrical conductivity). As the RGO content is further increased, the excess RGO sheets may result in reduced effective paths for the magnetic fields leading to a decreased SE59. To further assess the influence of total filler loading, Fe3O4@RGO with the optimized composition (MR20) was incorporated into PDAP at different weight percentages. The corresponding SE parameters are shown in Fig. 11. SER values increased steadily with increasing MR20 loading, averaging 3.4 dB, 6.3 dB, and 11.4 dB for PDAP composites containing 10 wt%, 20 wt%, and 25 wt% MR20, respectively. SEA followed the same trend, with average values of 9.7 dB, 15.9 dB, and 20.1 dB across the X-band. The resulting SET (Fig. 11c) increased from 13.2 dB to 22.3 dB and 31.5 dB, respectively, confirming the dominant contribution of absorption in high-filler composites60. This improvement can be explained by the increased proximity of RGO sheets and magnetic Fe3O4 domains within the PDAP matrix, which promotes the formation of interconnected conductive–magnetic networks. These networks facilitate multiple internal reflections, interfacial polarization, and magnetic dipole resonance, thereby enhancing both absorption and reflection components of EMI attenuation61. Although a full NRW retrieval was not experimentally feasible with the available setup, the analytical framework of the Nicolson–Ross–Weir (NRW) method was adopted conceptually to calculate the real and imaginary parts of permittivity and permeability. Using the measured SET, SEA, and SER values, together with the standard attenuation constant and impedance relations, ε′, ε″, µ′, and µ″ were calculated and used to interpret the dielectric and magnetic loss contributions. This approach provides a physically consistent estimation of the electromagnetic parameters analogous to NRW theory. To quantitatively interpret the dominant absorption contribution in the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites, the key electromagnetic parameters were calculated directly using classical electromagnetic relations at 10 GHz. The calculated permittivity values (ε′ = 12.0, ε″ = 4.0) indicate strong dielectric polarization and conduction loss associated with the partially percolated RGO network and the Maxwell–Wagner interfacial polarization at PDAP/RGO and PDAP/Fe3O4 interfaces. The calculated permeability values (µ′ = 1.30, µ″ = 0.30) reflect magnetic relaxation processes, including natural resonance and multi-domain wall damping in the Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The dielectric and magnetic loss tangents, calculated as tanδe = ε″ / ε′ ≈ 0.33 and tanδm = µ″ / µ′ ≈ 0.23, confirm the coexistence of strong dielectric and magnetic loss channels. From these parameters, the attenuation constant was calculated as α ≈ 225 Np/m, while the corresponding skin depth was found to be δ ≈ 3 mm. Since the composite specimens used in this study have a thickness of approximately 5 mm (> δ), the majority of the incident electromagnetic energy penetrates the surface and is dissipated inside the material. This directly explains the experimentally observed absorption-dominated behavior (SEA ≫ SER). The Fe3O4@RGO hybrid filler plays a synergistic role: (i) RGO forms conductive pathways that enhance conduction loss, interfacial polarization, and dipole relaxation; (ii) Fe3O4 introduces magnetic resonance and eddy current damping; (iii) the combined dielectric–magnetic effects improve impedance matching (Z ≈ Zo), allowing more energy to enter the material rather than being reflected. These combined mechanisms account for the high attenuation efficiency and the superior absorption-dominated EMI shielding performance of the PDAP-based hybrid nanocomposites. The DC electrical conductivity (σ) of the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites shows a strong dependence on the filler loading62, as presented in Fig. 12. A slow conductivity response is observed for the PMR10 sample (σ ≈ 1 × 10−2 S/m), indicating that the conductive network formed by the hybrid Fe3O4@RGO filler has not yet become continuous. Upon increasing the loading to 20 wt% (PMR20), the conductivity increases abruptly to ~ 0.8 S/m, representing nearly two orders of magnitude enhancement. This sharp transition is characteristic of a percolation-like behavior63, where the conductive pathways of RGO sheets begin to interconnect and facilitate long-range electron hopping64. Further increasing the hybrid filler content leads to a more progressive rise in σ, reaching ~ 1.8 S/m and ~ 2.5 S/m for PMR30 and PMR40, respectively. These trends clearly indicate that the electrical percolation threshold (ϕc) occurs slightly above 10 wt% and close to 15 wt% Fe3O4@RGO, where a fully connected conductive network is established within the PDAP matrix. The observed DC conductivity evolution correlates strongly with the imaginary permittivity (ε″) and with the absorption component of EMI shielding (SEA). A higher σ enhances conduction loss and Maxwell–Wagner interfacial polarization, promoting stronger dielectric loss, while the Fe3O4 nanoparticles contribute magnetic relaxation65. The synergy between these effects enables efficient attenuation of the incident electromagnetic waves, as confirmed by the calculated dielectric and magnetic loss tangents and the attenuation constant. These results demonstrate that the formation of a percolated RGO-based network at filler loadings ≥ 20 wt% plays a dominant role in governing the absorption-driven EMI shielding performance of the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP nanocomposites. The uniform microstructure observed in the SEM images of PMR20 further supports these findings, confirming the effective dispersion of hybrid fillers. A comparative summary of the EMI shielding performance of this system with previously reported Fe3O4 and graphene-based polymer composites is provided in Table 3, highlighting the superior performance of the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP system at relatively low filler loadings.

As shown in Table 3, the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP composites exhibit competitive shielding effectiveness compared to recently reported graphene-based systems, while offering absorption-dominated behavior and a thermosetting PDAP matrix that has rarely been explored for EMI shielding.

Conclusions

In summary, Fe3O4@RGO hybrid nano-fillers were successfully synthesized and uniformly integrated into a poly(di-allyl phthalate) (PDAP) matrix to produce lightweight EMI shielding composites with well-controlled dielectric–magnetic coupling. Structural analyses confirmed the effective anchoring of Fe3O4 nano-particles onto RGO sheets and their homogeneous distribution within the polymer. The calculated electromagnetic parameters (ε′ ≈ 12, ε″ ≈ 4, µ′ ≈ 1.3, µ″ ≈ 0.3 at 10 GHz) revealed strong dielectric and magnetic dissipation channels, which, together with the enhanced interfacial polarization and conduction pathways provided by RGO, resulted in an absorption-dominated shielding mechanism. This dominance of absorption is consistent with the high attenuation constant and the condition SEA ≫ SER across the X-band. The PMR20 composition exhibited the highest average SET (~ 31.5 dB), corresponding to over 99.9% attenuation of incident radiation. Overall, the Fe3O4@RGO/PDAP system demonstrates efficient dielectric–magnetic synergy, good impedance matching, and favorable absorption characteristics, establishing PDAP-based hybrids as promising candidates for lightweight EMI shielding. Future work will focus on mechanical evaluation and long-term stability to further support their practical implementation.

Data availability

The data and materials of this study are declared to be available by the authors. Interested parties can request for the datasets generated during the study from the corresponding author. (Hussein Oraby [hussein.mohamed4544@yahoo.com] (mailto: hussein.mohamed4544@yahoo.com) ) on reasonable.

References

Bhaskaran, K., Bheema, R. K. & Etika, K. C. The influence of Fe3O4@ GNP hybrids on enhancing the EMI shielding effectiveness of epoxy composites in the X-band. Synth. Met. 265, 116374 (2020).

Oraby, H. et al. Tuning electro-magnetic interference shielding efficiency of customized polyurethane composite foams taking advantage of RGO/Fe3O4 hybrid nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 12 (16), 2805 (2022).

Oraby, H. et al. Optimization of electromagnetic shielding and mechanical properties of reduced graphene oxide/polyurethane composite foam. Polym. Eng. Sci. 62 (10), 3075–3087 (2022).

Oraby, H. et al. Electromagnetic interference shielding of thermally exfoliated graphene/polyurethane composite foams. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139 (41), e53008 (2022).

Chung, D. Materials for electromagnetic interference shielding. Mater. Chem. Phys. 255, 123587 (2020).

Chung, D. D. L. Carbon materials for structural self-sensing, electromagnetic shielding and thermal interfacing. Carbon 50 (9), 3342–3353 (2012).

Klett, J. W. et al. The role of structure on the thermal properties of graphitic foams. J. Mater. Sci. 39 (11), 3659–3676 (2004).

Khodiri, A. A., Al-Ashry, M. Y. & El-Shamy, A. G. Novel hybrid nanocomposites based on Polyvinyl alcohol/graphene/magnetite nanoparticles for high electromagnetic shielding performance. J. Alloys Compd. 847, 156430 (2020).

Gupta, T. K. et al. MnO2 decorated graphene nanoribbons with superior permittivity and excellent microwave shielding properties. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2 (12), 4256–4263 (2014).

Ganguly, S. et al. Poly (N-vinylpyrrolidone)-stabilized colloidal graphene-reinforced Poly (ethylene-co-methyl acrylate) to mitigate electromagnetic radiation pollution. Polym. Bull. 77 (6), 2923–2943 (2020).

Bouhfid, N. et al. Functionalized graphene and thermoset matrices–based nanocomposites: mechanical and thermal properties, In Functionalized Graphene Nanocomposites and their Derivatives 47–64 (Elsevier, 2019).

Bhawal, P. et al. Superior electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness and electro-mechanical properties of EMA-IRGO nanocomposites through the in-situ reduction of GO from melt blended EMA-GO composites. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 134, 46–60 (2018).

Lee, C. et al. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321 (5887), 385–388 (2008).

Qiang, C. et al. Magnetic properties and microwave absorption properties of carbon fibers coated by Fe3O4 nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 506 (1), 93–97 (2010).

Yuchang, Q. et al. Graphene nanosheets/BaTiO3 ceramics as highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding materials in the X-band. J. Mater. Chem. C. 4 (2), 371–375 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Sustainable Carbon-Based catalyst materials derived from lignocellulosic biomass for energy storage and conversion: atomic modulation and properties improvement. Carbon Energy. 7 (5), e708 (2025).

Katheria, A. et al. Fe3O4@ g-C3N4 and MWCNT embedded highly flexible polymeric hybrid composite for simultaneous thermal control and suppressing microwave radiation. J. Alloys Compd. 988, 174287 (2024).

Wei, B. et al. In-Situ Synthesis of Rgo/Fe 3 O 4 Nanocomposites: Optimizing Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Properties.

Tan, Y. et al. PVDF/MWCNTs/RGO@ Fe3O4/AgNWs composite film with a bilayer structure for high EMI shielding and electrical conductivity. Polym. Compos. 46 (2), 1161–1176 (2025).

Yasir, M. & Kim, S. R. 3D-structured polymer composites using advanced templating strategies for EMI shielding. Polym. Compos., (2025). https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.29642

Tian, C. et al. Synthesis and microwave absorption enhancement of yolk–shell Fe3O4@ C microspheres. J. Mater. Sci. 52 (11), 6349–6361 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Facile synthesis of iron oxides/reduced graphene oxide composites: application for electromagnetic wave absorption at high temperature. Sci. Rep. 5 (1), 9298 (2015).

Zhan, Y. et al. Fabrication of a flexible electromagnetic interference shielding Fe3O4@ reduced graphene oxide/natural rubber composite with segregated network. Chem. Eng. J. 344, 184–193 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Novel 3D network porous graphene nanoplatelets/Fe3O4/epoxy nanocomposites with enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency. Compos. Sci. Technol. 169, 103–109 (2019).

Hong, S. Y. et al. Anisotropic electromagnetic interference shielding properties of polymer-based composites with magnetically-responsive aligned Fe3O4 decorated reduced graphene oxide. Eur. Polymer J. 127, 109595 (2020).

Vaishnavi, R. Y. et al. Green Nanocomposites of PLA/PBAT Reinforced with Fe3O4 and GNP: EMI Shielding, Mechanical, Thermal, and Morphological Analysis. Polym. Compos. (2025).https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.70453

Liu, X. et al. Enhanced dielectric-magnetic synergy in hybrid Ni@ NiO/rGO aerogel enables high-performance electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. 60 (35), 15668–15681 (2025).

Oraby, H. et al. Effective electromagnetic interference shielding using foamy polyurethane composites. Polym. Compos. 42 (6), 3077–3088 (2021).

Weston, D. Electromagnetic Compatibility: Principles and Applications, Revised and Expanded (CRC, 2017).

Li, J. et al. Morphologies and electromagnetic interference shielding performances of microcellular epoxy/multi-wall carbon nanotube nanocomposite foams. Compos. Sci. Technol. 129, 70–78 (2016).

Yun, J. et al. Effect of oxyfluorination on electromagnetic interference shielding behavior of MWCNT/PVA/PAAc composite microcapsules. Eur. Polymer J. 46 (5), 900–909 (2010).

Wang, G. et al. Injection-molded microcellular PLA/graphite nanocomposites with dramatically enhanced mechanical and electrical properties for ultra-efficient EMI shielding applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6 (25), 6847–6859 (2018).

Reddy, B. Advances in Nanocomposites: synthesis, Characterization and Industrial Applications (BoD–Books on Demand, 2011).

Jo, J. et al. Facile synthesis of reduced graphene oxide by modified Hummer’s method as anode material for Li-, Na-and K-ion secondary batteries. Royal Soc. Open Sci. 6, 181978 (2019).

Yahagi, Y. et al. Infrared absorption spectra of the high-pressure phases of Cristobalite and their coordination numbers of silicon atoms. Solid State Commun. 89 (11), 945–948 (1994).

Shalaby, A. et al. Preparation, characterization and thermal stability of reduced graphene oxide/silicate nanocomposite. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 48 (1), 38 (2016).

Jafari, A. et al. Effect of annealing temperature on magnetic phase transition in Fe3O4 nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 379, 305–312 (2015).

Paredes, J. I. et al. Graphene oxide dispersions in organic solvents. Langmuir 24 (19), 10560–10564 (2008).

Zeng, F. et al. In situ one-step electrochemical Preparation of graphene oxide nanosheet-modified electrodes for biosensors. ChemSusChem 4 (11), 1587–1591 (2011).

Song, P. et al. Fabrication of exfoliated graphene-based polypropylene nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical and thermal properties. Polymer 52 (18), 4001–4010 (2011).

Stankovich, S. et al. Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 45 (7), 1558–1565 (2007).

Elsaidy, A. et al. Tuning the thermal properties of aqueous nanofluids by taking advantage of size-customized clusters of iron oxide nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 344, 117727 (2021).

Otero-Lorenzo, R. et al. Solvothermal clustering of magnetic spinel ferrite nanocrystals: a Raman perspective. Chem. Mater. 29 (20), 8729–8736 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Ultralow electrical percolation in graphene aerogel/epoxy composites. Chem. Mater. 28 (18), 6731–6741 (2016).

Choudhary, N., Hwang, S. & Choi, W. Carbon nanomaterials: a review. Handbook of nanomaterials properties, 709–769. (2014).

CheunáLee, H. & RahmanáMohamed, A. Correction: Review of the synthesis, transfer, characterization and growth mechanisms of single and multilayer graphene. RSC Adv. 7 (45), 28427–28427 (2017).

Kumar, V. et al. Properties of silicone rubber-based composites reinforced with few-layer graphene and iron oxide or titanium dioxide. Polymers 13 (10), 1550 (2021).

Cui, T. et al. Effect of lattice stacking orientation and local thickness variation on the mechanical behavior of few layer graphene oxide. Carbon 136, 168–175 (2018).

De Faria, D. L., Venâncio, S., Silva & de Oliveira, M. T. Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides. J. Raman Spectrosc. 28 (11), 873–878 (1997).

Jubb, A. M. & Allen, H. C. Vibrational spectroscopic characterization of hematite, maghemite, and magnetite thin films produced by vapor deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2 (10), 2804–2812 (2010).

Yau, X. H. et al. Correction: Magnetically recoverable magnetite-reduced graphene oxide as a demulsifier for surfactant stabilized crude oil-in-water emulsion. Plos One. 19 (2), e0298915 (2024).

Kusumawati, R. et al. Characterization of Fe3O4/RGO composites from natural sources: application for dyes color degradation in aqueous solution. (2020).

Padhi, D. K. et al. Green synthesis of Fe3O4/RGO nanocomposite with enhanced photocatalytic performance for cr (VI) reduction, phenol degradation, and antibacterial activity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5 (11), 10551–10562 (2017).

Wang, Q. et al. One-pot synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticle loaded 3D porous graphene nanocomposites with enhanced nanozyme activity for glucose detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9 (8), 7465–7471 (2017).

Kahsay, M. H. et al. Magnetite nanoparticle decorated reduced graphene oxide for adsorptive removal of crystal Violet and antifungal activities. RSC Adv. 10 (57), 34916–34927 (2020).

Dewanto, A. et al. omposites of Fe3O4/SiO2 from natural material synthesized by co-precipitation method. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. (IOP Publishing, 2017).

Chowdhury, M. N. K. et al. Physicochemical and micromechanical investigation of a nanocopper impregnated fibre reinforced nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 5 (122), 100943–100955 (2015).

Jamsaz, A. & Goharshadi, E. K. Flame retardant, superhydrophobic, and superoleophilic reduced graphene oxide/orthoaminophenol polyurethane sponge for efficient oil/water separation. J. Mol. Liq. 307, 112979 (2020).

Verma, M. et al. Graphene nanoplatelets/carbon nanotubes/polyurethane composites as efficient shield against electromagnetic polluting radiations. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 120, 118–127 (2017).

Kuester, S. et al. Processing and characterization of conductive composites based on Poly (styrene-b-ethylene-ran-butylene-b-styrene)(SEBS) and carbon additives: A comparative study of expanded graphite and carbon black. Compos. Part. B: Eng. 84, 236–247 (2016).

Sharif, F. et al. Segregated hybrid Poly (methyl methacrylate)/graphene/magnetite nanocomposites for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9 (16), 14171–14179 (2017).

Nath, K. et al. Facile production of binary polymer/carbonic nanofiller-based biodegradable electromagnetic interference shield films with low electrical percolation threshold. Polym. Eng. Sci. 62 (11), 3841–3857 (2022).

Nath, K. et al. Synthesis of ionic liquid modified 1-D nanomaterial and its strategical distribution into the biodegradable binary polymer matrix to get reduced electrical percolation threshold and electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 141 (5), e54897 (2024).

Nath, K. et al. Design of interconnected 1D nanomaterials with selective localization in biodegradable binary thermoplastic nanocomposite films for effective electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. Polym. Adv. Technol. 34 (3), 1019–1034 (2023).

Nath, K. et al. Fabrication of lightweight and biodegradable EMI shield films with selective distribution of 1D carbonaceous nanofiller into the co-continuous binary polymer matrix. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 34 (8), 773 (2023).

Rao, B. B. et al. Single-layer graphene-assembled 3D porous carbon composites with PVA and Fe 3 O 4 nano-fillers: an interface-mediated superior dielectric and EMI shielding performance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17 (28), 18353–18363 (2015).

Yao, K. et al. Flammability properties and electromagnetic interference shielding of PVC/graphene composites containing Fe3O4 nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 5 (40), 31910–31919 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency of polystyrene/graphene composites with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Carbon 82, 67–76 (2015).

Yang, C. et al. Highly oriented CNTs endowing PP foam with high electrical conductivity and excellent electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 7 (18), 12682–12694 (2025).

Malakar, A., Mohanty, A. & Bose, S. Hierarchical Carbon–Metal Architectures in Flexible Polymer Multilayers Enabling High-Performance Electromagnetic Interference Shielding (ACS Applied Engineering Materials, 2025).

Nayak, J. et al. Microcellular carbon Nanotube/Thermoplastic elastomer nanocomposite foam to amplify Absorption-Driven electromagnetic shielding efficiency. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 6 (19), 11974–11986 (2024).

Kang, J. S., Zhang, H. X. & Yoon, K. B. Hybrid rGO–CNT/Epoxy nanocomposites as electromagnetic interference shielding materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7 (9), 10770–10778 (2024).

Siri, M. et al. Investigation on AC conductivity and X-band electromagnetic shielding efficacy of rGO doped PMMA-PVDF polymer blend. Synth. Met., 314, 117937. (2025).

Kaftelen Odabaşı, H. Electrical, Thermal, Flexural, and EMI-Shielding properties of Epoxy-Based polymer composites reinforced with RGO/AgRGO Spray-Coated carbon fibers. Coatings 15 (12), 1404 (2025).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The authors confirm that they did not receive any funding, grants, or other forms of support while working on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ahmed saeed Abo elfath: Methodology, Investigation, Data collection and analysis, draft preparation, Hamada Abd elwahab: Data collection, analysis, and the first draft of the manuscript, Medhat E. Owda: Data collection, analysis, Reviewing and Editing Ahmed Shalaby: Data collection, analysis, and the first draft of the manuscript, and reviewing the final copy. Hussein Oraby: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Editing and reviewing the final copy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

The manuscript has received approval and consent for authorship, publication, and submission from all mentioned authors who have read and agreed to its contents.

Consent for publication

The publication of this paper is free from any conflict of interest as declared by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elfath, A.S.A., Elwahab, H.A., Owda, M.E. et al. Poly(di-allyl phthalate) hybrid nanocomposites with magnetic conductive coupling for absorption dominated EMI shielding. Sci Rep 16, 2612 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33772-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33772-3