Abstract

Yachting tourism, as part of the global marine leisure industry, presents unique operational characteristics that increase vulnerability to safety incidents. While human factors are widely recognized as a dominant cause of maritime accidents, existing analytical frameworks offer limited explanatory power for the complexity of yachting contexts. This study develops an adapted Human Factors Analysis and Classification System for yachting (HFACS-YA) and applies it to a comprehensive dataset of yachting tourism accidents. A combination of chi-square tests was used to identify statistically significant human factor categories, and complex network modeling was employed to reveal structural relationships and critical causal pathways. Results show that “unsafe acts” are the most frequent immediate contributors to accidents, but the underlying root causes largely originate from “organizational influences,” including deficiencies in safety management systems, inadequate training programs, and low safety awareness. Prominent pathways involve legislative gaps, flawed organizational processes, poor supervisory oversight, and decision-making errors. By integrating statistical inference with network analysis, this research provides a replicable methodological framework for investigating accident causation in small-vessel maritime tourism. The findings offer actionable insights for regulators, maritime authorities, and industry stakeholders to enhance safety governance and reduce accident risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continued growth of global social and economic development, coupled with rising living standards, has driven increasing demand for high-quality, personalized travel experiences. Within the spectrum of leisure tourism, maritime tourism represents a rapidly expanding interface between the global shipping industry and the tourism economy. Within this continuum, cruise shipping has long exemplified the economic and safety significance of passenger-oriented maritime transport, while yachting tourism constitutes its small-scale, private, and often less regulated counterpart. As a distinct form of Special Interest Tourism (SIT), yachting tourism has emerged as a rapidly expanding niche market, offering unique recreational and experiential value1,2,3.Its market potential is underscored by optimistic global and regional forecasts: the global yacht market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.2% between 2021 and 2028, with the Chinese market expected to expand even faster—by 20–25% annually4,5. In 2021, the global yacht charter market was valued at USD 13.28 billion, with an anticipated CAGR of 5.4% through 20316. In China, the sector recorded a CAGR of 15% from 2019 to 2023 and is projected to surpass USD 12 billion by 20307.

Despite the sector’s momentum, scholarly investigations into yachting tourism have predominantly examined economic8, social9, and ecological impacts10,11, consumer behaviour12, and development strategies13. Research addressing safety issues—particularly those involving human factors—remains limited. Yachting accidents pose acute risks to human life, property, and the marine environment due to the inherently high-risk nature of such activities. Data from the China Cruise and Yacht Industry Association indicate that 6% of 1,335 surveyed yachts reported insurance claims for accidents14. In the United States, the U.S. Coast Guard recorded between 3,844 and 5,265 recreational boating accidents annually from 2020 to 2023, while the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) conducted 8,868 rescue operations in 2021. These statistics illustrate persistent and widespread safety risks, yet academic research on the topic remains sparse.

International studies consistently attribute a substantial share of maritime accidents—up to 96%—to human error15,16,17. Similar ratios have been documented across vessel types, including 84–88% of tanker accidents18, 79% of tugboat groundings19, and 75% of maritime fires20. In the Chinese context, research on human error in yachting accidents is especially underdeveloped. The country’s rapidly expanding yachting sector faces notable regulatory gaps in yacht leasing, marina operations, and coastal zoning21,22. These structural deficiencies can interact with individual decision-making in ways consistent with the “Swiss Cheese Model” of accident causation, which underscores the alignment of systemic failures and unsafe acts23. While prior work has largely focused on individual-level behaviours24,25, few studies have examined the role of organizational and regulatory systems in shaping accident risk—particularly in fast-growing but weakly regulated markets.

Accident causation has been conceptualized through several multi-layered theoretical models—including the Swiss Cheese Model, the Human Error Identification (HEI) framework, and the Systems-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes (STAMP)—which collectively emphasize the systemic and organizational nature of human error. Building on these insights, the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) provides a structured, hierarchical approach to identifying both latent and active failures across sectors such as aviation, shipping, mining, petroleum, medical treatmen and architecture26,27,28,29,30,31,32. However, HFACS has seen limited application in yachting tourism despite the unique risk profiles of this sector, including recreational equipment malfunctions, propeller entanglement, and nearshore navigation errors33,34. Moreover, existing HFACS-based studies often overlook the interdependencies among human factors, treating them as discrete hierarchical levels rather than components of a dynamic system35.

This study aims to clarify the human factors that contribute to yachting tourism accidents by classifying accident-related behaviors and identifying the multi-level mechanisms through which operational, supervisory, and organizational elements interact. Rather than relying on broad or generic categories, the analysis focuses on scenario-specific errors—such as guest management and recreational navigation practices—and examines how these frontline behaviors are shaped by assumptions embedded in safety management, training, and oversight. To pursue this objective, we develop an adapted Human Factors Analysis and Classification System for Yachting Accidents (HFACS-YA) and employ a mixed-method design that integrates grounded theory, statistical testing, and network-based modeling. Grounded theory is used to inductively identify human and organizational factors; chi-square and odds-ratio analyses evaluate significant associations among them; and complex network modeling maps the hierarchical structure and propagation pathways of failures within yachting operations.

This integrated approach combines qualitative insight with quantitative rigor, extending HFACS from a static classification tool to a dynamic analytical framework. It provides a multi-level understanding of accident causation in China’s emerging yachting tourism sector and offers generalizable methodological and practical implications for improving safety management in small-vessel maritime tourism worldwide.

Literature review

Yachting tourism

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has not classified yachts as mandatory management entities under international maritime conventions, leading to varied definitions and regulatory frameworks across different countries. In China, the Yacht Safety Management Regulations define a yacht as a mechanically propelled vessel intended solely for the personal use of its owner, such as for sightseeing and recreational purposes36. This definition explicitly excludes unpowered vessels and those used for public rentals, excursions, or recreational operations in parks, coastal areas, and scenic waters. Yachts are commonly categorized by propulsion type into unpowered boats, sailboats, and powerboats37. For the purposes of this study, “yachts” refer specifically to mechanically propelled powerboats used for sightseeing, leisure, and water sports38.

Despite its growing economic and recreational importance, yachting tourism lacks a universally accepted definition. Terms such as “yachting tourism,” “nautical tourism,” “boating tourism,” “recreational boating,” and “pleasure boating” are often used interchangeably39. Sariisik et al. (2011) describe it as a romantic, leisure-driven, and sport-oriented tourism activity involving privately or commercially owned medium-sized vessels40. Across definitions, common themes emerge: yachts are used for leisure or sport, with recreation, athleticism, and charterability forming the core elements of yachting tourism41. Accordingly, yachting tourism can be defined as a range of tourism activities conducted at sea, ports, or along coastlines, in which yachts serve as both transportation and accommodation to fulfill recreational, sporting, and entertainment needs.

Yachting tourism risks

Research directly addressing risks in yachting tourism remains limited; however, relevant evidence can be drawn from studies on small-vessel operations, coastal maritime accidents, and marine tourism activities. Existing work consistently demonstrates that yachting-related risks emerge from the interplay between human behavior, vessel characteristics, environmental conditions, and managerial practices.

In this broader research landscape, Yao et al. (2023) provided one of the few comprehensive assessments by combining fishbone diagrams and the Analytic Hierarchy Process to identify risks across human, vessel, environmental, and management dimensions. Their dynamic Bayesian network–based Yachting Tourism Safety Risk (YTSR) model further showed that human factors constitute the primary source of safety vulnerability42. Similar patterns are also observed in adjacent small-vessel research: Zhang et al. (2024) used probabilistic modeling to analyze fishing vessel collisions43, Francis et al. (2022) constructed a generic Bayesian network for small fishing vessel operational risks25, and Lee et al. (2019) developed a coastal accident model that explicitly incorporates human factors, underscoring their systemic significance24.

Beyond causal modeling, technological interventions have been explored to enhance operator performance and reduce risk. Kim et al. (2019) proposed a collision-avoidance support system based on dynamic risk-zone assessment, addressing the narrow decision windows typical in small-vessel navigation44. Complementing these safety-oriented studies, emerging research highlights the psychosocial dimensions of risk in commercial yachting. Paker and Osman (2021), for example, examined how customer-to-customer interaction (CCI) risks shape yacht navigators’ perceived value and service outcomes, revealing human-centered risk mechanisms often overlooked in operational analyses45.

Taken together, the literature indicates that although yachting tourism remains understudied, its risk architecture aligns closely with established patterns in small-vessel maritime safety—particularly the predominance of human factors across technical, environmental, and social domains. This convergence provides a strong rationale for the present study’s focus on systematically examining the human element within the yachting tourism safety system.

Human factors analysis and classification system

The HFACS offers a structured framework for identifying human contributions to accidents, hazardous events, and organizational failures. Originally developed for aviation, the model classifies human error across four hierarchical levels: unsafe acts, preconditions for unsafe acts, unsafe supervision, and organizational influences. Its demonstrated utility has led to widespread adaptation across diverse industries seeking greater contextual relevance and diagnostic precision.

HFACS has subsequently evolved along two complementary directions: contextual adaptation and methodological integration. Contextual adaptations refine HFACS taxonomies to better represent sector-specific realities. Omole and Walker (2015), for instance, broadened the framework by incorporating external influences—including political and societal pressures—recognizing that systemic failures often extend beyond organizational boundaries46. In the maritime domain, Uğurlu et al. (2018) proposed the HFACS-PV model for passenger vessels, adding a new “prerequisite” level to capture causal factors unique to that sector47.

At the same time, methodological integrations extend HFACS beyond descriptive classification toward quantitative and dynamic system analysis. Akyuz and Celik (2014) combined HFACS with cognitive mapping to elucidate complex causal relationships in a cruise ship lifeboat drill incident48. Subsequent research has embedded HFACS within probabilistic frameworks, such as Wang et al.’s (2024) Bayesian network model quantifying human and organizational contributions to vessel collisions49. Qiao et al. (2022) further advanced this line by integrating HFACS with Bayesian and complex network theories to reveal root causes of ship maintenance accidents50.

Despite its extensive application in aviation, merchant shipping, and construction, HFACS has not yet been systematically applied to yachting tourism, where safety insights are largely inferred from general maritime or marine tourism studies51,52. This gap limits the sector’s ability to identify human error pathways that are specific to yacht-based recreational and commercial activities. To address this deficiency, the present study develops and validates the HFACS-YA (Yachting Accidents) model, designed to capture the unique operational, environmental, and behavioral characteristics of yachting tourism. By contextualizing HFACS for this sector, the study seeks to reveal its distinctive human-factor causal patterns and provide targeted strategies for accident prevention.

The complex networks for risk analyse

Complex network theory has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing the structure and dynamic behavior of complex systems and has gained increasing prominence in the domain of risk analysis in recent years53,54. Unlike traditional accident causation models, which primarily emphasize linear, unidirectional causal chains, complex network theory enables the exploration of non-linear, interconnected, and emergent behaviors among multiple contributing factors. Accidents often result from a chain of interdependent events and interactions—known as coupling effects—which are inadequately captured by linear models. This limitation hinders a comprehensive understanding of how risk propagates through complex systems.

Complex network analysis addresses this gap by characterizing the structure of interactions among risk factors, thus providing novel insights into the hidden propagation mechanisms and coupling dynamics that underlie accident causation. The application of this approach has proven valuable for enhancing risk identification, evaluation, and mitigation strategies in high-risk environments. For example, Zhang et al. (2023) developed a Rule-based Maritime Traffic Situation Complex Network (R-MTSCN) model by defining directed edges based on ship collision avoidance rules. Using Automatic Identification System (AIS) data from vessels navigating the Yangtze River Estuary, they validated the applicability of the model in real-world maritime navigation scenarios55. Similarly, Deng et al. (2023) constructed a coastal maritime accident network in China by integrating four major risk domains—human, vessel, environment, and management—into a comprehensive network structure. They applied complex network metrics to examine the structural characteristics and systemic vulnerabilities of the maritime accident system56. Ma et al. (2024) focused specifically on human factors in maritime accidents, constructing a complex network of causative elements leading to ship groundings. Through topological analysis, they revealed the intricate interrelationships among human error nodes and highlighted critical points of intervention57.

Building on these foundations, the present study applies complex network theory within the HFACS framework to construct a human factors network tailored to yachting tourism accidents. By integrating qualitative causation analysis with quantitative topological metrics, this approach enhances our understanding of risk propagation pathways and provides a more holistic perspective on the dynamics of human error in recreational maritime activities.

Materials and methods

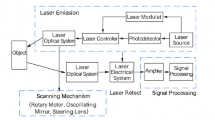

The methodology integrating HFACS, grounded theory, chi-square test, ratio analysis, and complex network analysis is described as follows:

Step 1: Qualitative analysis was performed utilizing Nvivo12.0 to discern the human factors present within the data samples.

Step 2: The conventional HFACS framework was adopted, leading to the introduction of the HFACS-YA framework, which categorizes the identified human factors based on strata. This framework facilitates the calculation of frequency counts and frequencies.

Step 3: The correlations and influence paths among human factors across different levels, as well as within the same level, were established through a chi-square test and ratio analysis.

Step 4: A complex network model was developed to identify the risk factors and critical causal elements, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Data source

The data utilized in this study were collected from multiple sources to ensure comprehensiveness and reliability while minimizing potential bias. Primary sources include official yacht accident reports issued by governmental agencies such as the Maritime Safety Administration and the Emergency Management Bureau. Supplementary data were obtained from yachting industry-related websites, literature databases, and relevant media reports. Following a rigorous screening process, a total of 179 yachting tourism accidents occurring between 2006 and 2024 were selected for analysis. These cases encompass a variety of incident types, including collisions, fires, groundings, reef strikes, and capsizings.

The selected cases predominantly involve motor yachts constructed from fiberglass and glass fiber, which are commonly used materials in modern yacht manufacturing. These vessels primarily operated in coastal environments, reflecting typical usage scenarios in Chinese yachting tourism. According to the classification by Popescu and Mocanu (2019), yachts are categorized as small (< 12 m), medium (12–24 m), and large (> 24 m)38. The majority of cases in this study involve small and medium-sized yachts under 24 m, which constitute the mainstream of China’s yachting industry. Large yachts, often classified as luxury vessels with more extensive crew and enhanced safety features, are relatively rare in China and associated with a limited number of publicly available accident cases. As such, they were excluded from the research sample.

To ensure adequate geographical representativeness, the dataset covers key coastal provinces—including Liaoning, Guangdong, Hainan, and Zhejiang—providing broad spatial coverage that supports the robustness and generalizability of the findings. The data used in this study exhibit strong validity. Although the overall sample size is modest, all cases are drawn from detailed official accident reports, and the core structure of the network analysis remains stable across samples. In addition, rigorous screening criteria were applied: only accidents involving motorized vessels that clearly fall within the definition of yachting tourism were included. This ensures that the identified human factors accurately reflect the characteristics of the yachting tourism context.

HFACS and its improvements

HFACS, derived from the “Swiss Cheese” model originally developed in aviation, integrates human factors and systems approaches23. Unlike other accident analysis methods, HFACS offers a detailed classification of human and organizational factors, enabling efficient identification of human errors in complex incidents58. Widely applied across industries, it is a valuable tool for analyzing accidents, hazardous events, and system failures26. The framework categorizes causal factors into four levels: unsafe acts, preconditions for unsafe acts, unsafe supervision, and organizational influences. These levels reflect a systemic approach to risk analysis, highlighting the interconnections among diverse risk sources (see Fig. 2).

While the traditional HFACS model has been widely applied, it is not universally suited to all domains, highlighting the need for domain-specific adaptations. In the maritime field, variants such as HFACS-PV (passenger vessel accidents), HFACS-MA (maritime accidents) and HFACS-Coll (collision accidents) have been developed, mainly for passenger, merchant, and fishing vessels. However, yachts differ fundamentally in terms of personnel, operating environment, and equipment. First, personnel: Yacht operators are often the owners, typically lacking professional training despite holding licenses. Their behavior is more easily influenced by emotion or risk-seeking tendencies (e.g., speeding, ignoring weather warnings). Existing models, like HFACS-PV, assume standardized crew training and do not account for passenger interference, a frequent issue in yachting. Second, operating environment: Yachting often involves high-risk recreational activities (e.g., diving, swimming, onboard parties), creating complex accident chains. In contrast, HFACS-MA addresses commercial risks such as cargo mishandling, not leisure-related hazards. Yachts also navigate shallow, congested waters, unlike commercial vessels on open routes. Third, equipment and maintenance: Yachts feature advanced systems (e.g., autopilot, electronic navigation) that may be misused by amateurs, and their maintenance is often irregular—unlike the mandatory inspections in commercial shipping. Given these distinctions, this study develops a tailored framework—HFACS-YA—to analyze human factors in yachting accidents.

Compared to the traditional HFACS framework, the HFACS-YA model introduced in this study incorporates an additional tier—External Factors—positioned above the conventional organizational level. This modification acknowledges the broader systemic influences that contribute to yachting tourism accidents. The external tier comprises four subcategories: legislative gaps, administration oversights, design flaws, and social factors, aligning with earlier extensions proposed by Reinach and Viale (2006)59.

In refining the model, the original subcategories under “Human Factors” and “Operator Status” were consolidated. Analysis of accident reports indicated that elements under “Human Factors” primarily pertained to individual preparedness, while those under “Operator Status” related to psychological conditions. To streamline the framework, these were broadly reclassified under the single category of Human Factors. Furthermore, due to insufficient evidence in the accident reports to distinguish between unintentional and routine violations, both were merged into a unified Violations category.

The revised HFACS-YA model is presented in Fig. 3, with the updated components highlighted in red. Specifically, legislative gaps refer to inadequacies in regulatory frameworks governing the yacht industry and its oversight bodies. administration oversights denotes the ineffective implementation of safety rules and monitoring mechanisms by yacht operators, owners, and relevant authorities. For example, fragmented governance in China’s yachting sector—spread across multiple agencies—often leads to overlapping responsibilities and regulatory blind spots. Design flaws relate to deficiencies in yacht architecture or marina infrastructure. Social factors encompass broader systemic issues such as economic constraints, safety culture, and political context. For instance, some yacht owners may deliberately reduce maintenance frequency or use inferior parts to minimize operational costs, thereby undermining vessel safety. Taken together, these findings underscore the necessity of integrating an external factors level into the HFACS-YA model to more accurately capture the systemic nature of accident causation in the yachting tourism sector.

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a methodological approach aimed at identifying the fundamental concepts underlying social or managerial phenomena through systematic analysis and generalization of raw data. This process involves continuous comparison and successive abstraction of core concepts and categories, ultimately leading to the construction of a theoretical framework. Since its inception, grounded theory has been recognized for its rigorous operational processes and practical methodological characteristics. This approach encompasses several stages, including data collection, three levels of coding, theory construction, testing, and revision. The three levels of coding includes open coding, axial coding, and selective encoding60,61. This is shown in Fig. 4.

The chi-square test and odds ratio analysis

The chi-square test is a hypothesis testing method that can be used to analyze the association between two variables62. In this study, the chi-square test was employed to examine whether statistically significant associations exist among human factors across different levels of the HFACS-YA framework. The chi-square test starts with the null hypothesis H0 and alternative hypothesis H1. H0: There is no significant correlation between human factors at different tiers; H1: There is a significant correlation between human factors at different tiers. The chi-square (\({\chi ^2}\)) can be expressed as

Where \({f_i}\) is the actual observed value, and \({f_e}\) is the theoretical observed value.

When p < 0.05, the null hypothesis H0 was rejected, indicating a significant correlation between the two factors; otherwise, there was no significant correlation between the two factors.

The odds ratio (OR) is an eigenvalue that measures the correlation between the attributes X and Y. This study introduces Odds Ratio (OR) to quantify the influence degree among human factors across different levels of the HFACS-YA framework. Let OR be m, and the calculation formula is

When m > 1, a change in the upper factor increases the probability of the occurrence of the lower factor. When m < 1, a change in the upper-level factor does not significantly affect the lower-level factor.

Complex network

Complex networks abstractly model real-world complex systems by visualizing data with a network topology architecture, reflecting the relationship between entities through nodes and edges, enabling an effective representation of these systems63. A complex network is a graph \(G=(V,E)\) comprising a certain number of node sets v and edge sets E. \(V=\left\{ {{v_1},{v_2},...,{v_n}} \right\}\) denotes the set of all nodes, that is, the set of human factors in Table 2, and \(E=\left\{ {{e_1},{e_2},...,{e_n}} \right\}\) denotes the set of all edges, that is, the set of effective co-occurring human factor pairs of connecting lines. Thus, a complex network can be represented by Eq. (3).

.

When a factor i triggers another factor, it triggers j and \({a_{ij}} = 1\) and vice versa\({a_{ij}} = 0\) . \({w_{ij}}\) denotes the weights of the edges between nodes. Analyzing the topological characteristics of the network can effectively identify the key nodes in the network and their dynamic characteristics.

Results

Human factors identification based on HFACS-YA and grounded theory

A grounded theory methodology was employed to examine yachting tourism accident reports with the aim of identifying the human factors contributing to the accidents. In this study, Nvivo12.0 software is used for coding. The classification attributes of the HFACS-YA were integrated into the coding framework of grounded theory. Table 1 illustrates the coding process.

In accordance with grounded theory, concepts related to human factors were initially extracted from accident investigation reports. To reduce subjectivity during the coding process, the original statements from these reports were employed as the foundation for concept mining. Subsequently, the relevance and distinctions among these concepts were analyzed through open coding, leading to their classification into appropriate categories. During the axial coding process, the main categories were established by synthesizing the categories identified in the open coding stage. Subsequently, the relationships between the main categories were elucidated, allowing the abstraction of core categories that encompass all identified categories. This study integrates five levels of the HFACS-YA model framework for delineation purposes. Finally, a saturability test was performed; the ten accident samples that had not been previously coded and analyzed were subjected to the aforementioned coding process. The results indicated that no new concepts or categories emerged, thereby demonstrating that the human factors identified through grounded theory within the HFACS-YA framework reached a state of saturation.

Through the grounded theory approach, a comprehensive analysis identified 75 human factors contributing to yachting tourism accidents, which were subsequently categorized into various levels according to the HFACS-YA framework. Figure 5 presents the classification results. It can be seen from the results that the most significant contribution to yachting tourism accidents is the unsafe acts level (the frequency is 426, accounting for 32%), followed by the organizational influences level (the frequency is 292, accounting for 22%). The top five predominant human factors are ineffective execution of safety management responsibilities (B23), low safety awareness (B22), inadequate safety management (B21), windy waves and strong currents (D41), and failure to maintain a formal lookout (E31). The cumulative frequency of these five factors exceeded one (1.04), suggesting that accidents were attributable to the confluence of multiple interacting factors rather than a singular cause. The detailed list and statistics for Fig. 5 can be found in Appendix A1.

Using \({\chi ^2}\) and OR to analyze the relevance of human factors in yachting tourism accidents

Based on the identified human factors, chi-square tests and odds ratio analysis were performed on 144 factor pairs using SPSS. The calculations included p-values and odds ratios (m). Applying the criteria of p < 0.05 and m > 1, a total of 103 factor pairs were filtered out, such as legislative gaps (A1) and inadequate supervision (C1), among others. The filtering results are presented in Table 2.

In the HFACS-YA framework, external factors are classified as Level 1 and exert influence over the following four levels: external factors, organizational influences, unsafe supervision, preconditions for unsafe acts, and unsafe acts. Notably, the strongest associations among these relationships are observed in the pairs of :

-

- administration oversights (A2)→inadequate supervision (C1);

-

- administration oversights (A2)→supervisory violations (C4);

-

- social factors (A4)→supervisory violations (C4).

This highlights the connection between external factors and unsafe supervision. Furthermore, the m values for these three pairs of factors ranked among the highest, at 6.563, 9.429, and 10.08, respectively. The analysis shows that administration oversights increases the likelihood of inadequate supervision and supervisory violations by 6.563 and 9.429 times, respectively. In addition, social factors raise the probability of supervisory violations by 10.08 times.

Organizational influences affect unsafe supervision and preconditions for unsafe and unsafe acts. Eighteen sets of factor pairs were found to be significantly associated. Based on the p-value, the top 3 factor pairs identified were:

-

- poor organizational safety climate (B2)→failure to correct problems (C2);

-

- poor organizational safety climate (B2)→decision errors (E2);

-

- poor organizational safety climate (B2)→human factors (D2).

Based on the ORs, B2 is expected to increase the probabilities of C2, E2, and D2 by approximately 20, 10, and 10 times.

Unsafe supervision is categorized as Level 3, and there are 7 sets of factor pairs with significant correlations with the preconditions for unsafe acts and unsafe acts. Two groups of factors were most prominent:

-

- factor pairs (C4)→violations (E4);

-

- inadequate supervision (C1)→decision errors (E2).

C4 increasing the probability of E4 occurring to 5 times the original probability, and C1 is expected to cause an increase in the probability of E2 being generated by a factor of about 4.

According to HFACS-YA, the preconditions of unsafe acts predispose individuals to the human factors associated with these acts. Unsafe acts can only occur if specific conditions are present. There is a significant correlation between operator status (D1), human factors (D2) and physical environment (D4) at the precondition level of unsafe acts and skill errors (E1), decision errors (E2) and perceptual errors (E3) at the level of unsafe acts, where the m of physical environment (D4)→skill errors (E1) is the largest at 4.144.

Correlations between human factors exist not only between different upper and lower tiers but also between individual factors in the same tier. Table 3 shows the results. Eleven groups of factor pairs were significantly correlated, of which administration oversights (A2) had the strongest correlation with social factors (A4), with an m value of 31.2. A2 led to an approximately 31-fold enhancement in the likelihood that A4 would be present.

Based on the results in Tables 2 and 3, the influence pathways among human factors were derived and are illustrated in Fig. 6, where dashed lines represent incomplete causal chains. As summarized in Table 4, eight complete causal paths were identified. The strongest pathway is A1–B3–C1–D2–E2 (legislative gaps→improper organizational processes→inadequate supervision→human factors→decision errors), with a cumulative weight of 17.627.

Human factors complex network

Building upon the initial analysis of closely linked elements within the HFACS-YA framework, this study constructs a complex network to further explore the intricate relationships among human factors in yachting tourism accidents. By incorporating more granular causes, the network approach enhances the depth of accident analysis and reveals additional insights.

Recognizing that human factors can interact both within and across hierarchical levels, the analysis includes intra-tier and cross-tier relationships. To identify latent multi-factor interactions not captured by HFACS or chi-square tests, association rule mining was applied using SPSS Modeler 18.0, yielding 1,452 factor pairs64. Based on the hierarchical logic of the HFACS-YA framework, cross-tier connections are directional (from higher to lower tiers), while intra-tier relationships are non-directional. Invalid or logically inconsistent pairs were excluded from the final model65.

The cleaned edge and node lists were imported into Gephi 0.10.1 to construct a complex network model comprising 75 nodes and 1,357 valid edges. The resulting network visualization is presented in Fig. 6. In the network, the 75 identified human factors (see Fig. 7) serve as nodes and are categorized by different colors. Specifically, external factors (Level 1) are shown in dark green; organizational influences (Level 2) in blue; unsafe supervision (Level 3) in orange; preconditions for unsafe acts (Level 4) in light green; and unsafe acts (Lecel 5) in purple. The size of each node reflects its importance or influence. Edges represent causal relationships between nodes, with their direction indicating causality. Edge weights correspond to the frequency of factor pair co-occurrences across 179 accident reports66,67, and edge thickness indicates the strength of the connection.

To further identify the key elements within the complex network, a core subnetwork was extracted based on the top 10 nodes ranked by PageRank (PR) values, see Fig. 8. This subnetwork highlights several organizational-level factors—B22 (low safety awareness), B23 (ineffective implementation of safety management responsibilities), and B21 (inadequate safety management)—as central hubs with both high PR values and dense interconnections. Their dominant positions and extensive outward influence across hierarchical levels suggest that these organizational deficiencies play a pivotal role in shaping downstream unsafe conditions and operational errors. The structure of the subnetwork demonstrates that interventions directed at these organizational hubs are likely to disrupt major causal pathways and yield the greatest systemic impact.

Clustering coefficient

The clustering coefficient reflects the degree of clustering of nodes in a complex network68. A larger clustering coefficient indicates that the nodes are more closely related to surrounding nodes. It was calculated using Eq. (4).

Where \({E_i}\) denotes the number of connected edges that exist between neighboring nodes of node i, and \({k_i}\) denotes the number of edges connected to node i.

Figure 9 presents the clustering coefficients of nodes within the complex network of yachting tourism accidents. A higher coefficient indicates stronger interconnections among risk factors, thereby increasing the likelihood of cascading failures once anomalies occur. Excluding invalid nodes with a clustering coefficient of 1, the network’s average clustering coefficient is 0.715, indicating a pronounced clustering tendency. Notably, the highest clustering coefficients were found among external factors, organizational influences, and unsafe acts. The top five nodes are:

-

- A42 (0.964, subjective misconceptions of yacht owners);

-

- B13 (0.945, poor quality of life jackets);

-

- E211 (0.933, incomplete emergency plan);

-

- D13 (0.901, thrill-seeking behavior);

-

- E11 (0.886, no showing the signal light).

In contrast, nodes such as B22 (0.493, low safety awareness), B23 (0.541, ineffective execution of safety management responsibilities), B21 (0.546, inadequate safety management), E24 (0.552, improper operation), and E210 (0.555, improper emergency measures) exhibit relatively low clustering coefficients, suggesting limited systemic influence.

Nodes with high clustering coefficients indicate that their neighboring nodes are densely interconnected, often forming tightly knit subgroups. These nodes are particularly vulnerable to cascading failures and play a critical role in the propagation of accidents. Accordingly, risk management strategies should prioritize these high-clustering nodes to improve system resilience and prevent chain-reaction incidents.

A complete list of clustering coefficients is provided in Appendix A2, and the sorted ranking table is presented in Appendix A3.

Node importance based on PageRank. PageRank assessed the importance of nodes in a complex network of human factors. It can assist us in effectively identifying these key nodes, enabling targeted measures to reduce the likelihood of accidents. Its formula is as follows (5).

Where \({M_i}\) is the point connected to the node i, \(W\left( {i,j} \right)\) is the weight of the edge \(\left( {i,j} \right)\) , \(D\left( j \right)\) is the degree of the node j, and d is the attenuation coefficient, which is usually taken as d = 0.85.

The PageRank algorithm determines the relative importance of each node through an iterative calculation process, as illustrated in Fig. 10. Based on the PageRank (PR) values shown in the figure, the key nodes within the complex network of yachting tourism accidents are identified as:

-

- B22 (0.024, low safety awareness);

-

- B23 (0.022, ineffective implementation of safety management responsibilities);

-

- B21 (0.022, inadequate safety management);

-

- B31 (0.021, insufficient training);

-

- E31 (0.021, failure to maintain a proper lookout).

These nodes significantly influenced the likelihood of accidents occurring in the tourism context. Mitigating these risk factors can effectively prevent accidents, thereby enhancing safety and minimizing potential hazards.

In contrast, nodes such as E46 (0.003, illegal use of flammable materials) and B14 (0.003, improper storage and safekeeping of life jackets) occupy peripheral positions with relatively low influence.

Closeness centrality

Closeness centrality measures how central a node is within a network, reflecting its average distance to all other nodes. The shorter the distance, the more quickly the node can reach or influence others. This is expressed as Eq. (8).

Where \(d_{ij}\) is the distance between node i and j.

As shown in Fig. 11, the nodes with higher closeness centrality values are B22 (0.925, low safety awareness), B23 (0.871, ineffective execution of safety management responsibilities), B21 (0.860, inadequate safety management), B31 (0.851, inadequate training), E31 (0.841, failure to maintain a formal lookout). This indicates their central positions within the network and their ability to rapidly influence other nodes in the event of a failure. Notably, nodes B22 to B31 fall under the category of organizational influences, emphasizing that deficiencies in safety management are critical contributors to yachting tourism accidents.

In contrast, nodes such as E46 (0.463, illegal use of flammable materials), B14 (0.484, improper storage and safekeeping of life jackets), E211 (0.517, incomplete emergency plan), are located in peripheral positions and play relatively marginal roles within the network.

To mitigate risks associated with high closeness centrality, it is essential to optimize the allocation of key resources—such as personnel, equipment, and financial support—strengthen operational monitoring and maintenance, incorporate system redundancies, and reduce dependency on single points of failure. For example, daily yacht operations rely on the Chief Officer and deck crew to implement the Safety Management System (SMS), conduct regular inspections, and ensure compliance through routine drills and training69.

Modularity class

Modularity analysis was conducted to examine whether human factors form distinct communities within the network. The network was partitioned into four modules (0–3) (Fig. 12), with a modularity score of Q = 0.107—well below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.3 for strong community structure. This result suggests that human and organizational factors do not cluster into independent subsystems but instead constitute an interwoven risk network in which influences readily traverse functional and hierarchical boundaries.

Although the overall modularity is weak, several structural patterns remain observable. Module 0, the largest and most interconnected, spans multiple HFACS levels, reflecting the close coupling between organizational deficiencies and frontline operational errors. The smaller modules also maintain substantial linkages with Module 0 and with each other, indicating that localized issues may be embedded within broader system interactions and that organizational-level shortcomings can readily shape operational behaviors.

These findings reinforce that human factors seldom operate in isolation and that operational errors often originate from deeper supervisory or organizational conditions. Accordingly, effective safety management should emphasize system-level resilience rather than isolated nodes, including strengthening redundancy, enhancing cross-level communication and feedback mechanisms, and cultivating a safety culture capable of identifying and interrupting risk transmission across modules.

Comprehensive analysis

The analysis of Table 5 reveals that nodes B22, B23, B21, B31, and E31 exhibit both high PageRank scores and high closeness centrality, indicating that they possess substantial influence as well as efficient propagation capabilities within the network. These nodes span the organizational influences and unsafe acts levels within the HFACS framework, demonstrating that the various HFACS tiers are not isolated but rather tightly coupled through network interactions. This finding supports the hypothesis of strong interdependence between upper-level decision-making and frontline operations, echoing the “organizational deficiencies penetrating multiple layers of defense” mechanism described in Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model.

Notably, despite their high PageRank and closeness centrality values, nodes B22, B23, and B21 exhibit relatively low clustering coefficients. This suggests that the corresponding sectors—government departments, yacht enterprises, and tourist attractions—lack strong interconnections and collaborative linkages, resulting in an “islanding” phenomenon that impedes effective accident prevention in yachting tourism.

These nodes paradoxically hold both central decision-making authority (as they are widely relied upon) and information efficiency (as they can quickly affect the entire system), creating a unique governance dilemma: critical yet isolated nodes exert disproportionate systemic influence. Addressing this challenge requires enhanced inter-agency coordination and information sharing to improve governance resilience.

Discussion

Theoretical implications

Human factors are widely recognized as a primary driver of maritime accidents, yet the yachting tourism sector has lacked a domain-specific analytical framework. This study addresses this gap by developing an adapted Human Factors Analysis and Classification System for Yachting Accidents (HFACS-YA), calibrated to the operational characteristics of China’s rapidly expanding yachting tourism industry. By systematically identifying and classifying human-related causes and mapping their multi-level interactions through integrated qualitative and network-based methods, the study provides a coherent theoretical lens for understanding how organizational conditions, supervisory practices, and frontline behaviors jointly shape accident causation. This refined framework lays a foundation for more precise human-factor research in leisure vessel contexts and supports the development of evidence-based safety management in yachting tourism.

The revised HFACS-YA retains the hierarchical structure of the original HFACS but introduces “external factors” as a foundational layer and adjusts classifications under preconditions for unsafe acts and unsafe acts to better represent yachting-specific hazards71,72. Grounded theory analysis revealed that unsafe acts were the most frequent category of human factor failure, often traceable to organizational deficiencies. Specifically, ineffective execution of safety management responsibilities (B23), low safety awareness (B22), and inadequate safety management (B21) emerged as consistent high-risk nodes, aligning with prior findings in broader maritime contexts72,73.

Chi-square and odds ratio analyses identified 53 statistically significant associations among human factor categories across HFACS levels. Three causal chains were particularly prominent: poor organizational safety climate (B2) → failure to correct problems (C2); poor organizational safety climate (B2) → decision errors (E2); and administration oversights (A2) → social factors (A4). In addition, eight complete causal pathways were mapped, the most influential being: legislative gaps → improper organizational processes → inadequate supervision → human factors → decision errors. Viewed through a systems lens, these pathways illustrate how seemingly individual decision errors are embedded in—and often triggered by—upstream structural conditions, echoing core principles of the myth-of-human-error framework.These results reinforce the notion that preventing accidents requires disrupting key causal pathways at their origin. Complex network analysis further highlighted the structural dominance of organizational-level nodes, particularly with respect to PageRank values and closeness centrality, underscoring their role as both frequent sources and critical conduits of systemic risk.

Interestingly, despite their structural importance, nodes such as the safety management responsibilities (B23), low safety awareness (B22), and inadequate safety management (B21) exhibited relatively low clustering coefficients, reflecting weak inter-organizational connectivity. This “islanding” phenomenon—where influential safety governance actors operate in silos—limits collaborative risk mitigation. Paradoxically, these same nodes hold substantial decision-making authority and strong information propagation capacity, creating a governance paradox in which isolated yet powerful entities exert disproportionate influence on systemic safety outcomes. Addressing this requires strengthening horizontal linkages via formal coordination mechanisms, shared data platforms, and cross-sectoral drills, thus enabling more integrated and resilient safety governance.

The study’s contributions to the literature are threefold. First, while prior research has largely examined human error in general maritime contexts, few have considered human factors specific to yachting tourism—particularly in rapidly expanding but loosely regulated markets. The HFACS-YA developed here captures both cross-hierarchical and intra-level interactions among human factors, overcoming the common limitation of focusing solely on vertical causal chains74,75 and providing a stronger theoretical basis for targeted interventions. Second, the integrated methodological approach—combining grounded theory, HFACS, complex network analysis, chi-square tests, and odds ratios—enhances the precision and comprehensiveness of human factor identification in yachting accidents. Third, by using SPSS Modeler 18.0 to extract associated factor pairs and model their relationships within a complex network, the analysis captures same-level causal pathways often overlooked in earlier studies57,76,77, broadening the methodological toolkit for human factor research in maritime tourism safety.

Managerial implications

Building on these results, a three-tiered intervention framework is proposed to enhance safety in the yachting tourism sector. First, at the policy and regulatory level, maritime authorities should establish differentiated safety standards tailored to recreational yachts, distinct from those for commercial or industrial vessels. This includes risk-based inspection regimes, leasing compliance guidelines, and standardized equipment requirements, implemented through incentive-based regulatory mechanisms. Second, in terms of training and awareness, crew members should receive standardized safety training with periodic evaluations, incorporating gamified emergency simulations to increase engagement and retention. Tourists should be provided with mandatory safety briefings, deliverable via automated video stations located at marinas and scenic areas. Third, regarding information infrastructure, the establishment of a unified yacht safety management platform integrating data from maritime, tourism, and commercial sectors is recommended. Such a platform would enable real-time risk monitoring, support evidence-based policy decisions, and facilitate inter-agency coordination for comprehensive yacht safety governance.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the accident data were obtained from publicly accessible sources, which may contain reporting biases or insufficient detail. Second, although the dataset included multiple accident types, the analysis did not distinguish differences across accident categories; future studies could conduct comparative analyses to identify type-specific human-factor patterns. Third, incidents involving luxury yachts—whose operational profiles and regulatory conditions may differ substantially—were not included. Future research should address these gaps, further calibrate and validate the HFACS-YA framework, and assess its applicability across broader small-vessel and maritime tourism settings to enhance both theoretical robustness and practical generalizability.

Conclusion

This study developed and implemented a domain-specific Human Factors Analysis and Classification System for Yachting Accidents (HFACS-YA) to systematically identify and quantify human factors contributing to yachting tourism accidents in China. By integrating grounded theory, HFACS, chi-square testing, and complex network analysis, the findings demonstrate that organizational deficiencies—particularly inadequate supervision, weak safety awareness, and insufficient training—represent the predominant root causes of such accidents.

The study provides actionable insights for improving yachting tourism safety management in both domestic and international contexts. It highlights how human factors interact within organizational systems to either amplify or mitigate risk, emphasizing the importance of organizational governance and multi-level interventions. By combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, this research advances both the theoretical understanding of human factor causation in small-vessel maritime tourism and the practical toolkit for risk reduction, offering a replicable framework applicable to similar sectors worldwide.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xu, B. & Bai, X. A review of research on project risk identification, measurement and evaluation. Project Manage. Techniques. 12 (05), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-4313.2014.05.004 (2014).

Kaptan, M., Songü, S., Uğurlu, Ö. & Wang, J. The evolution of the HFACS method used in analysis of marine accidents: a review. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 86, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ERGON.2021.103225 (2021).

Yildiz, S., Uğurlu, Ö., Wang, X., Loughney, S. & Wang, J. Dynamic accident network model for predicting marine accidents in narrow waterways under variable conditions: a case study of the Istanbul Strait. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12 (12), 2305–2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/JMSE12122305 (2024).

CCYIA - China Cruise and Yacht Industry Association. China yacht industry report in 2016–2017 (China Cruise & Yacht Industry Association, 2017).

Yacht Market Size. Share & Trends Analysis Report by Type (super yacht, fly bridge yacht, sport yacht, long range yacht). by Length, by Propulsion, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2021–2028 (Grand View Research, 2021).

FMI - Future Market Insights. Yacht charter market. global industry analysis and opportunity assessment, 2021–2031. london: FMI. (2021).

Huajing Industry Research Institute (HIRI). 2024–2030 Market Research and Future Development Trends Forecast Report on China’s Yacht Economy Industry. https://www.docin.com/touch_new/preview_new.do?id=4724205672

Walker, T. B. & Rolle, S. McLeod M. Yachting tourism’s contribution to the caribbean’s social economy and environmental stewardship. Worldw. Hospitality Tourism Themes. 15 (4), 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-03-2023-0048 (2023).

Eui, Y. C., Jang, W. Y. & Tae, H. P. Key attributes driving yacht tourism: exploring tourist preferences through conjoint analysis. Sustainability 17 (8), 3336–3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU17083336 (2025).

Yao, Y. H. & Luan, W. X. Analysis on the coupling and coordinated development of coastal City Economy, marine ecological environment and yacht tourism. Ocean. Bull. 37 (04), 361–369 (2018).

Antonio, A. et al. The economic impact of yacht charter tourism on the Balearic economy. Tour. Econ. 17 (3), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2011.0045 (2011).

Luo, J. M., Lam, C. F. & Ben, H. Y. Barriers for the sustainable development of entertainment tourism in Macau. Sustainability 11 (7), 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072145 (2019).

Yao, Y. H., Zheng, R. Q. & Parmak, M. Examining the constraints on yachting tourism development in china: A qualitative study of stakeholder perceptions. Sustainability 13 (23), 13178–13178. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU132313178 (2021).

China Communications and Transportation Association Cruise Yacht Branch. Shenzhen Ocean Blue Yacht Service Co., Ltd, 2020. National Yacht Development Expert Steering Committee. 2019–2020 China Yacht Industry Development Report.

Qiao, W. L., Liu, Y., Ma, X. X. & Liu, Y. A methodology to evaluate human factors contributed to maritime accident by mapping fuzzy FT into ANN based on HFACS. Ocean Eng. 197, 106892–106892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.106892 (2020a).

Fan, S., Eduardo, B. D., Yang, Z. L., Zhang, J. F. & Yan, X. P. Incorporation of human factors into maritime accident analysis using a data- driven Bayesian network. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 203(prepublished). (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.107070

Wróbel, K. Searching for the origins of the myth: 80% human error impact on maritime safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 216, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESS.2021.107942 (2021).

Ung, S. T. Human error assessment of oil tanker grounding. Saf. Sci. 104, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.12.035 (2018).

Graziano, A., Teixeira, A. P. & Soares, C. G. Classification of human errors in grounding and collision accidents using the tracer taxonomy. Saf. Sci. 86, 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.02.026 (2016).

Quinn, P. T. & Scott, S. M. The Human Element in Shipping Casualties. Tavistock Institute of Human Relations London (1982).

Ding, W. T., Qi, Y. & Ya, H. Y. Major issues and countermeasures in the construction and management of yacht terminals in China. Pearl River Water Transp. 21, 56–57. https://doi.org/10.14125/j.cnki.zjsy.2017.21.019 (2017).

Fu, G. C. & Chen, X. H. Analysis of safety management practices and countermeasures in yacht leasing. China Maritime (09), 38–39 + 43.10.16831/j.cnki.issn1673-2278.09.014 (2020). (2020).

Reason, J. Human error:models and management. Bmj 320 (7237), 768–770. http://doi.org/101136bmj3207237768/ (2000).

Kim, L. & Lee Development of a new tool for objective risk assessment and comparative analysis at coastal waters. J. Int. Maritime Saf. Environ. Affairs Shipping. 2 (2), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/25725084.2018.1562511 (2019).

Francis, O., Domeh, V., Khan, F., Bose, N. & Sanli, E. Analyzing operational risk for small fishing vessels considering crew effectiveness. Ocean Eng. 249, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCEANENG.2021.110512 (2022).

Patterson, J. M. & Shappell, S. A. Operator error and system deficiencies:analysis of 508 mining incidents and accidents from Queensland,Australia using HFACS. Accid. Anal. Prev. 42 (4), 1379–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.02.018 (2010).

Guido, P., Marco, G., Stanislav, F. & Simona, G. Natural Language Processing for the identification of Human factors in aviation accidents causes: An application to the SHEL methodology. Expert Syst. Appl. 186. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ESWA.2021.115694 (2021).

Yildirim, U., Başar, E. & Uğurlu, Ö. Assessment of collisions and grounding accidents with human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS) and statistical methods. Saf. Sci. 119, 412–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.09.022 (2019).

Guo, M. Y. et al. Investigation of ship collision accident risk factors using BP-DEMATEL method based on HFACS-SCA. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 257 (PB), 110875–110875. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESS.2025.110875 (2025).

Zhang, B., Kong, L., You, Z. L., Liu, Y. & Zhang, Y. R. Dynamic risk analysis for oil and gas exploration operations based on HFACS model and bayesian network. Pet. Sci. Technol. 43 (6), 676–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/10916466.2024.2308033 (2025).

Mahdi, J., Ehsanollah, H., Nima, K., Shapour, B. A. & Habibollah, D. A novel framework for human factors analysis and classification system for medical errors (HFACS-MES)-A Delphi study and causality analysis. PloS One. 19 (2), e0298606–e0298606. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0298606 (2024).

Qi, H. N. et al. Modification of HFACS model for path identification of causal factors of collapse accidents in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 32 (7), 4718–4745. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-02-2023-0101 (2025).

Yang, Z. C. Law of collision accidents of merchant fishing vessels and preventive measures for merchant vessels in coastal waters of Zhejiang. China Maritime (12), 20–23. https://doi.org/10.16831/j.cnki.issn1673-2278.2020.12.008 (2020).

Xing, Y. L. & Wang, X. Z. Research on fault prediction of diesel engines for yachts based on fuzzy neural network. Electromechanical Inform. 21, 58–59 (2018).

Celik, M. & Cebi, S. Analytical HFACS for investigating human errors in shipping accidents. Accid. Anal. Prev. 41 (1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2008.09.004 (2008).

Xu, Y. S. Yacht safety supervision and the application of Self-Imposed Risks-Also reviewing the revision of the yacht safety management regulations. World Shipping. 47 (02), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.13646/j.cnki.42-1395/u.2024.09.003 (2024).

Gu, Y. Z. Yacht and Cruise Ship Studies (Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 2015).

Popescu, T. D. & Mocanu, R. Classification criteria for pleasure yachts in relation to maritime safety regulations. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 24 (3), 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00773-018-00598-8 (2019).

Spinelli, R. & Benevolo, C. Towards a new body of marine tourism research: a scoping literature review of nautical tourism. J. Outdoor Recreation Tourism 40, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JORT.2022.100569 (2022).

Sariisik, M., Turkayb, O. & Akovac, O. How to manage yacht tourism in turkey:a Swot analysis and related strategies. Procedia Social Behav. Sci. 24, 1014–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.041 (2011).

Yao, Y. H. & Luan, W. X. Research on yachting tourism concept identification and development strategy. Mar. Dev. Manage. 34 (06), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.20016/j.cnki.hykfygl.2017.06.004 (2017).

Yao, Y. H., Zhou, X. X. & Merle, P. Risk assessment for yachting tourism in China using dynamic bayesian networks. PloS One. 18 (8), e0289607–e0289607. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0289607 (2023).

Zhang, M. L., Ding, T. M., Ding, C. J. & Ai, W. Z. Analysis of the causes of collisions among fishing vessels in offshore areas based on bayesian network. J. Shandong Jiaotong Univ. 32 (01), 110–115 (2024).

Kim, Y. R., Kang, S. J., Kim, W. O. & Kim, C. J. A study on the prevention of human errors in a small fishing boat. J. Fishries Mar. Sci. Educ. 31 (6), 1544–1551. https://doi.org/10.13000/jfmse.2019.12.31.6.1544 (2019).

Paker, N. & Osman, G. The influence of perceived risks on yacht voyagers’ service appraisals: evaluating customer-to-customer interaction as a risk dimension. J. Travel Tourism Mark. 38 (6), 582–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1969316 (2021).

Omole, H. & Walker, G. Offshore transport accident analysis using HFACS. Procedia Manuf. 3, 1264–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.270 (2015).

Uğurlu, Ö., Yildiz, S., Loughney, S. & Wang, J. Modified human factor analysis and classification system for passenger vessel accidents(HFACS-PV). Ocean Eng. 161, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.04.086 (2018).

Akyuz, E. & Celik, M. Utilisation of cognitive map in modelling human error in marine accident analysis and prevention. Saf. Sci. 70, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.05.004 (2014).

Wang, H., Chen, N., Wu, C. & Guedes, S. Human and organizational factors analysis of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels based on HFACS-BN model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 249110201. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESS.2024.110201 (2024).

Qiao, W. L. et al. Human-Related hazardous events assessment for suffocation on ships by integrating bayesian network and complex network. Appl. Sci. 12 (14), 6905–6905. https://doi.org/10.3390/APP12146905 (2022).

Yin, X. Y. et al. Data-Driven analysis of the causal chain of waterborne traffic accidents: A hybrid framework based on an improved human factors analysis and classification system with a bayesian network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 13 (3), 393–393. https://doi.org/10.3390/JMSE13030393 (2025).

Nasur, J., Krzysztof, B., Paulina, W., Mateusz, G. & Wróbel, K. Toward modeling emergency unmooring of manned and autonomous ships – A combined FRAM + HFACS-MA approach. Saf. Sci. 181106676–181106676. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSCI.2024.106676 (2025).

Wang, K. S., Wen, F. H. & Gong, X. Oil prices and systemic financial risk: A complex network analysis. Energy 293130672. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2024.130672 (2024).

Sekara, V., Stopczynski, A. & Lehmann, S. Fundamental structures of dynamic social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (36), 9977–9982. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602803113 (2016).

Zhang, F. et al. A rule-based maritime traffic situation complex network approach for enhancing situation awareness of vessel traffic service operators. Ocean Eng. 284, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCEANENG.2023.115203 (2023).

Deng, J. et al. Risk evolution and prevention and control strategies of maritime accidents in China’s coastal areas based on complex network models. Ocean Coast. Manag. 237, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2023.106527 (2023).

Ma, L. H., Ma, X. X., Wang, T., Chen, L. G. & He, L. On the development and measurement of human factors complex network for maritime accidents: a case of ship groundings. Ocean Coast. Manag. 248, 106954. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2023.106954 (2024).

Wiegmann, D. A. & Shappell, S. A. Human factors analysis of post accident data:applying theoretical taxonomies of human error. Aviat. Psychol. 7, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327108ijap0701_4 (1997).

Reinach, S. & Viale, A. Application of a human error framework to conduct train accident/incident investigations. Prevention 38 (2), 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2005.10.013 (2006).

Yang, L., Wang, X., Zhu, J. Q. & Qin, Z. Y. Risk Factors Identification of Unsafe Acts in Deep Coal Mine Workers Based on Grounded Theory and HFACS. Front. Public. Health 10852612–10852612. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPUBH.2022.852612 (2022).

Ariadna, G. S., Paola, G. E., Dolors, R. M. & Àngel, G. G. Nursing at the Intersection of Power and Practice: A Grounded Theory Analysis of the Profession’s Social Position. Journal of advanced nursing (2025). https://doi.org/10.1111/JAN.70126

Yoshiyasu, T. Assessing demographic influences on recidivism: A comprehensive analysis through chi-squared tests and machine learning techniques. Cities 166106207–166106207. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CITIES.2025.106207 (2025).

Li, K. P. & Wang, S. S. A network accident causation model for monitoring railway safety. Saf. Sci. 109, 398–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.06.008 (2018).

Dai, C. Y., Liu, J. H., Li, X. Y. & Zhang, Y. C. Research on Human Factor Analysis Methods for Accidents in Railway Locomotive Systems. Railway Transp. Economy. 47(5), 1–10 (2025).

Xia, Q. X., Wang, G. H., Wang, H., Zhang, Y. L. & Tian, L. Q. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of coal mine accident causation based on complex networks and bayesian networks. J. North. China Inst. Sci. Technol. 22 (01), 48–55 (2025).

Lan, H., Ma, X. X., Qiao, W. L. & Ma, L. H. On the causation of seafarers’ unsafe acts using grounded theory and association rule. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 223, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESS.2022.108498 (2022).

Wang, J. & Zhang, L. A complex network approach to accident causation analysis. Saf. Sci. 93, 128–140 (2017).

Paolo, B., Clemente, G. P. & Grassi, R. Clustering coefficients as measures of the complex interactions in a directed weighted multilayer network. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 610, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSA.2022.128413 (2023).

Gladkikh, V. On Board a Luxury Vessel: Demystifying the Daily Operations. Springer Books. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86406-4_5

Qiao, W. L., Liu, Y., Ma, X. X. & Liu, Y. Human factors analysis for maritime accidents based on a dynamic fuzzy bayesian network. Risk Analysis: Official Publication Soc. Risk Anal. 40 (5), 957–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13444 (2020b).

Nermin, H., Srđan, V., Vlado, F. & Leo, Č. The role of the human factor in marine accidents. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9 (3), 261–261. https://doi.org/10.3390/JMSE9030261 (2021).

Chen, S. T. An approach of identifying the common human and organisational factors (HOFs) among a group of marine accidents using GRA and HFACS-MA. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2019.1583297 (2019).

Yildiz, S., Uğurlu, Ö., Wang, J. & Loughney, S. Application of the HFACS-PV approach for identification of human and organizational factors (HOFs) influencing marine accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 208 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESS.2020.107395 (2021).

Chen, Z. B., Zeng, J. C., Dong, Z., Zhao, N. & Li, Z. W. Human factors analysis of coal mine safety accidents human factors analysis of coal mine safety accidents based on HFACS. J. Saf. Sci. 23 (07), 116–121. https://doi.org/10.16265/j.cnki.issn1003-3033.2013.07.021 (2013).

Li, L., Li, J., Ren, Y. F. & Tang, X. Research on the causes of urban rail train delay risks based on the HFACS model. J. Saf. Sci. 33 (05), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.16265/j.cnki.issn1003-3033.2023.05.0503 (2023).

Wang, H., Chen, N., Wu, B. & Guedes, S. Human and organizational factors analysis of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels based on HFACS-BN model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 249110201. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESS.2024.110201 (2024).

Wang, X. L., Xiang, Y. H., Wang, L. L., Dong, B. Y. & Tong, R. P. Identification of critical causes of construction accidents in China using a hybrid HFACS-CN model. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergonomics: JOSE. 30 (2), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2024.2308453 (2024).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Found of China [No.25CJY112].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yunhao Yao: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yujie Zhao: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Chen Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Formal analysis. U. Rashid Sumaila: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Merle Parmak: Writing – original draft, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Y., Zhao, Y., Li, C. et al. Human factors in yachting tourism accidents: an integrated human factors classification framework with statistical and network analysis. Sci Rep 16, 3737 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33808-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33808-8