Abstract

To analyze the potential therapeutic value and mechanism of luteolin in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) using network pharmacology and cellular experiments. SHD-compound targets were retrieved from the TCMSP database, while AMD-related targets were extracted from OMIM and DisGeNET databases. Overlapping targets were identified via Venny 2.1. A PPI network was constructed using the STRING database, followed by functional enrichment analysis of overlapping targets via Metascape. Pharmacological networks were mapped using Cytoscape. For cellular experiments, the optimal concentration of luteolin was determined by CCK-8 assay. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were divided into: Control group (Without any intervention), Model group (VEGF165-induced model), and Treatment group (VEGF165-induced + luteolin). Angiogenesis was evaluated via scratch, transwell migration, invasion, and tube formation assays. VEGFA protein expression was assessed by Western blot. We identified 157 SHD-compound targets and 87 AMD-related targets, yielding 6 overlapping targets (ESR1, PON1, SOD1, APOB, VEGFA, IL6). PPI networks and enrichment analysis revealed that luteolin in SHD may inhibit AMD neovascularization via VEGFA signaling pathways. The concentration of luteolin (25 µmol/L) used in the experiments was selected based on the dose-response results. In vitro assays showed the Treatment group exhibited: significantly reduced horizontal migration (scratch assay, p < 0.05), decreased vertical migration (transwell assay, p < 0.05), suppressed invasion (p < 0.05), and inhibited tube formation (p < 0.05). Western blot confirmed reduced VEGFA expression in the treatment group (p < 0.05). Luteolin alleviates angiogenesis in HUVECs by inhibiting VEGFA expression, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic candidate for neovascular AMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness among the elderly. Its prevalence increases with age in individuals over 60 years old1. With the rapid aging of the population, the prevalence of AMD is expected to rise from 196 million in 2020 to 288 million by 20402,3. Despite substantial advances in clinical treatments in recent years, the complex nature of the disease continues to result in suboptimal therapeutic outcomes. Current AMD therapies primarily target choroidal neovascularization (CNV), such as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents including ranibizumab4. Although these anti-angiogenic treatments have markedly reduced blindness rates, a subset of patients shows inadequate response to therapy and fails to maintain visual acuity even after prolonged treatment. Furthermore, frequent intravitreal injections elevate risks of complications and impose substantial financial burdens5,6. Consequently, developing novel therapeutic strategies to effectively treat and cure AMD remains an urgent clinical priority.

The pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) involves complex interactions among multiple factors, including genetic predisposition, impaired lipid metabolism, chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress. The disease is pathologically characterized by degeneration of choroidal endothelial cells, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and photoreceptors7. Clinically, AMD is classified into two subtypes: dry AMD (geographic atrophy) and wet AMD (choroidal neovascularization). Although wet AMD accounts for only 10–20% of cases, it carries a significantly higher risk of vision loss compared to the dry form8. Following rupture of Bruch’s membrane, abnormal blood vessels proliferate from the choroid into the subretinal or sub-RPE space. Subsequent vascular leakage causes subretinal fluid accumulation, hemorrhage, macular edema, and ultimately fibrotic scarring, resulting in irreversible vision loss9. In wet AMD, choroidal neovascularization (CNV) formation is directly associated with pathological overexpression of VEGFA. As the predominant member of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family, VEGFA exerts three principal pathological effects: (1) stimulating endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival to promote neovascularization; (2) enhancing vascular permeability leading to plasma protein extravasation; and (3) recruiting inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages) to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. These mechanisms collectively underscore the therapeutic rationale for targeting VEGFA in wet AMD management10,11.

Recent years have witnessed growing interest in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) as a potential therapeutic approach for AMD. Sanhua Decoction (SHD), a classical TCM formula, comprises four herbal components: Rheum palmatum (Da Huang), Magnolia officinalis (Hou Po), Notopterygium incisum (Qiang Huo), and Citrus aurantium (Zhi Shi)12,13,14,15. Preclinical studies demonstrate its neuroprotective effects through antioxidative stress mitigation and anti-inflammatory actions, along with a favorable safety profile16. Furthermore, SHD alleviates ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating tight junction-associated proteins, preserving vascular endothelial integrity, and regulating endothelial function16. Notably, Ying Huang et al.13 identified that bioactive compounds in SHD may attenuate cerebral and inflammatory damage through multi-pathway regulation involving IL-6, APP, AKT1, and VEGFA signaling. Given the established pathological links between AMD and oxidative damage, inflammatory responses, and endothelial dysfunction17,18, these findings suggest substantial therapeutic potential of SHD in AMD management. However, no prior studies have specifically investigated SHD’s efficacy in AMD. Through integrated network pharmacology analysis and cellular validation, our study reveals that luteolin—a key bioactive constituent of SHD—emerges as a promising candidate for wet AMD treatment by suppressing VEGFA protein expression and subsequent pathological angiogenesis.

Materials and methods

Network pharmacological analysis

Screening of bioactive compounds in Sanhua decoction and their corresponding target genes

Using the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP; https://tcmspw.com/index.php), chemical constituents of Sanhua Decoction components—Rheum palmatum (Da Huang), Magnolia officinalis (Hou Po), Notopterygium incisum (Qiang Huo), and Citrus aurantium (Zhi Shi)—were systematically screened based on pharmacokinetic criteria: oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18. After merging non-redundant entries12,13, target genes corresponding to the identified bioactive compounds were subsequently retrieved from the TCMSP platform.

Identification of AMD and Sanhua decoction-related target genes

The target proteins of the active components were mapped to their corresponding gene names using the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/)19. Potential AMD-associated targets were identified through the DisGeNET database (https://www.disgenet.org/) and the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (https://www.omim.org/)20. The overlapping target genes between AMD treatment and Sanhua Decoction were determined via intersection analysis using Venny 2.1 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/)21.

Construction and analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

To further identify core regulatory targets, the overlapping target genes of AMD and Sanhua Decoction’s active compounds were submitted to the STRING biological database (https://string-db.org/) for PPI network construction22. The analysis was performed with the species parameter set to “Homo sapiens” and a minimum interaction score threshold of 0.4023.

Enrichment analysis of overlapping target genes

To identify the biological functions associated with the overlapping target genes, the shared targets between AMD and Sanhua Decoction’s active compounds were submitted to the Metascape(the version v3.5.20250701) online database (http://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1) for functional enrichment analysis24.

Construction of the Sanhua decoction pharmacological regulatory network

To further explore the potential mechanisms of action of Sanhua Decoction in AMD treatment, we utilized Cytoscape software (Version 3.9.1) to visualize the network relationships among the herbal components, chemical active compounds, target genes, disease associations, and signaling pathways, thereby constructing the pharmacological regulatory network of Sanhua Decoction13,25.

Experimental validation in vitro

Cell culture

HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells) were cultured in complete medium composed of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution, and 89% DME/F-12, and maintained in a cell culture incubator under standard conditions (37℃, 5% CO₂)26.

CCK-8 assay to evaluate the effect of Luteolin on HUVECs viability

Luteolin solutions with concentration gradients (0–200 µmol/L) were prepared in culture medium27. HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h. After removing the original medium, 100 µL of fresh medium containing 10 µL CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, followed by incubation for 3 h. The optical density (OD) values were measured using a microplate reader. The cell viability in the 0 µmol/L luteolin group was normalized to 1, and the relative cell viability of each concentration group was calculated. The optimal luteolin concentration was selected for subsequent experiments28.

Experimental groups

Control group: Cultured in complete medium; Model group: Cultured in medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL VEGF165; Treatment group: Cultured in medium containing 20 ng/mL VEGF165 and 25 µmol/L luteolin.

Scratch wound healing assay

HUVECs from each group were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured to confluence. Scratches were created in the cell monolayer using a sterile pipette tip, followed by PBS washing and further incubation in the cell culture incubator for 24 h. Images were captured at 0 h and 24 h, and the cell migration distance for each group was measured using Image-Pro-Plus software. The relative horizontal transfer rate was determined from three independent experimental replicates29.

Transwell migration assay

Adherent HUVECs were appropriately digested with trypsin to prepare a single-cell suspension. The cell density was adjusted to 1 × 10⁵ cells/mL based on cell counting. 100 µL of serum-free cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of Transwell inserts, while 600 µL of complete medium containing 10% serum (as a chemoattractant) was added to the lower chamber (24-well plate). After 24 h of incubation, non-migrated cells on the upper membrane surface were carefully removed. The migrated cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa stain for 30 min under light-protected conditions. Images were captured using an inverted microscope (100× magnification). The relative vertical migration rate was determined from three independent experimental replicates29,30.

Transwell invasion assay

Pre-chilled Transwell inserts (upper chamber) were coated with 60 µL of diluted Matrigel matrix and incubated in a cell culture incubator for 2 h to allow gel polymerization. Adherent HUVECs were appropriately digested with trypsin to prepare a single-cell suspension, and the cell density was adjusted to 1 × 10⁵ cells/mL based on cell counting. 200 µL of serum-free cell suspension was added to the Matrigel-coated upper chamber, while 600 µL of complete medium containing 10% serum (as a chemoattractant) was added to the lower chamber (24-well plate). The cells were then cultured for 24 h in the incubator. Non-invasive cells on the upper membrane surface were removed, and the invaded cells were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa stain, and imaged using an inverted microscope (100× magnification), following the same protocol as the Transwell migration assay. The relative invasion rate was determined from three independent experimental replicates30,31.

Tube formation assay

HUVECs were seeded onto Matrigel-coated 24-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 10⁵ cells/well and incubated in a cell culture incubator for 12 h. The number of tubular structures and their total area were quantified using Image-Pro-Plus software. The tube formation capacity of the control group was normalized to 1. The relative tube formation rate (based on tube number and area) was determined from three independent experimental replicates29.

Western blotting analysis

Total proteins were extracted by lysing cells with a mixture of RIPA buffer, PMSF, and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein samples were adjusted to equal concentrations, subjected to electrophoresis, and transferred onto PVDF membranes. β-Actin was used as the housekeeping protein for normalization. The gray values of protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software. Data from three independent experimental replicates were subjected to statistical analysis32.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently repeated at least three times. Experimental data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. One-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate intergroup differences, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant33.

Results

Identification of active components in Sanhua Decoction and target prediction

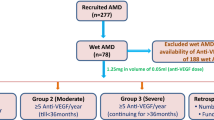

Active components of Sanhua Decoction were screened from the TCMSP database using the criteria OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18. The results are summarized in Table 1: Rheum palmatum (Da Huang): 16 active components with 109 targets; Magnolia officinalis (Hou Po): 2 active components with 33 targets; Notopterygium incisum (Qiang Huo): 15 active components with 109 targets; Citrus aurantium (Zhi Shi): 22 active components with 306 targets. After deduplication and consolidation, a total of 18 unique active components and 157 targets were identified from the four herbal constituents. For AMD-related targets: 77 disease targets were retrieved from the OMIM database; 30 disease targets were obtained from the DisGeNET database. After merging and deduplication, 87 AMD-associated targets were retained. The 157 Sanhua Decoction targets and 87 AMD targets were intersected using the Venny 2.1 online tool (Fig. 1), revealing 6 overlapping hub genes: ESR1, PON1, SOD1, APOB, VEGFA, and IL6.

Construction of PPI network and functional enrichment analysis of target genes

The six overlapping hub genes (ESR1, PON1, SOD1, APOB, VEGFA, and IL6) were imported into the STRING database to construct a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network (Fig. 2A). Functional enrichment analysis was performed using the Metascape online database with the following criteria: p < 0.01, minimum count = 3, and enrichment factor > 1.5. The results revealed that these target genes were primarily enriched in the key pathways: R-HSA-2,262,752 (Cellular responses to stress); GO:0035239 (tube morphogenesis) (Fig. 2B; Table 2), which were closely associated with the pathological changes of choroidal neovascularization in AMD, highlighting its potential role in disease progression.

“Count” is the number of genes in the user-provided lists with membership in the given ontology term. “%” is the percentage of all of the user-provided genes that are found in the given ontology term (only input genes with at least one ontology term annotation are included in the calculation). “Log10(P)” is the p-value in log base 10. “Log10(q)” is the multi-test adjusted p-value in log base 10.

Construction of the pharmacological regulatory network

The pharmacological regulatory network of Sanhua Decoction (comprising four herbal components: Rheum palmatum (Da Huang), Magnolia officinalis (Hou Po), Notopterygium incisum (Qiang Huo), and Citrus aurantium (Zhi Shi)) revealed that its chemical active components (Fig. 3, left panel) modulate AMD pathogenesis through regulating signaling pathways associated with overlapping target genes (Fig. 3, right panel). Dysregulation of VEGFA signaling is a central driver of the pathological angiogenesis observed in AMD. The network diagram (Fig. 3) delineates the potential associations among Luteolin (MOL000006), VEGFA, and AMD, suggesting a mechanistic link in the pathogenesis of AMD.

Optimal concentration of Luteolin

As shown in Fig. 4A, the effect of luteolin on HUVEC viability was assessed after 24-hour treatment at various concentrations. Cell viability increased initially at low concentrations (25 and 50 µmol/L) but decreased at higher concentrations (≥ 100 µmol/L). Based on the dose-response curve generated from the viability of HUVECs treated with various concentrations of luteolin, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated to be 101.4 µmol/L, and the 10% inhibitory concentration (IC10) was 25.26 µmol/L (Fig. 4B). Consequently, a luteolin concentration of 25 µmol/L was selected for subsequent experiments.

Luteolin suppresses angiogenesis in HUVECs

Scratch assay (Fig. 5A, B) demonstrated that the relative horizontal migration rate was significantly increased in the model group versus the control group (p < 0.05), whereas luteolin treatment markedly reduced migration compared to the model group (p < 0.05), indicating that luteolin inhibits horizontal migration of HUVECs. Transwell migration assay (Fig. 5C, D) revealed a significant increase in relative vertical migration rate in the model group versus controls (p < 0.05), while luteolin treatment significantly decreased migration relative to the model group (p < 0.05), confirming suppression of vertical migration by luteolin. Invasion assay (Fig. 5E, F) showed enhanced relative invasion rate in the model group versus controls (p < 0.05), with luteolin treatment significantly attenuating invasion compared to the model group (p < 0.05), demonstrating inhibition of HUVECs invasion capability. Tube formation assay (Fig. 5G–I) indicated elevated relative lumen formation rate in the model group versus controls (p < 0.05), while luteolin treatment dramatically reduced tube formation versus the model group (p < 0.05), proving luteolin’s suppression of lumen formation capacity. Collectively, these results demonstrate that luteolin effectively inhibits the angiogenic capacity of HUVECs.

Luteolin suppresses angiogenesis in HUVECs. (A) Scratch assay revealed that Luteolin inhibited horizontal migration of HUVECs; (B) Quantitative analysis of relative horizontal migration rate in (A) (n = 3); (C) Transwell migration assay demonstrated Luteolin’s suppression of vertical migration in HUVECs; (D) Quantitative analysis of relative vertical migration rate in (C) (n = 3); (E) Invasion assay indicated Luteolin inhibited HUVEC invasiveness; (F) Quantitative analysis of relative invasion rate in (E) (n = 3); (G) Tube formation assay showed Luteolin suppressed tube-forming capability of HUVECs; (H) Quantitative analysis of relative tube formation rate (branching points) in (G) (n = 3); (I) Quantitative analysis of relative tube formation rate (total tube area) in (G) (n = 3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Luteolin suppresses VEGFA expression in HUVECs

As shown in Figure 6A-B, VEGFA protein expression was significantly up-regulated in the model group compared to the control group (P < 0.05), while luteolin treatment markedly down-regulated VEGFA expression versus the model group (P < 0.05). This indicates that luteolin inhibits VEGF165-induced VEGFA expression in HUVECs.

Discussion

AMD is a degenerative retinal neuro-disorder affecting the macula that may present asymptomatically in early-to-intermediate stages but leads to severe visual impairment in late-stage disease34. This multifactorial disease involves risk factors including aging, genetic susceptibility, and smoking, with pathological mechanisms encompassing chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipid deposition35,36,37. Currently, there are no established therapeutic approaches capable of curing AMD in clinical practice. Consequently, developing safe, effective, and cost-efficient therapeutics represents an imperative unmet clinical need in AMD management. Accumulating evidence indicates that SHD exerts pivotal effects on suppressing inflammatory responses, alleviating oxidative stress, and promoting neuroprotection16,38,39,40. Given that AMD—a neurodegenerative disease—shares pathological mechanisms including chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipid deposition41, SHD’s potential therapeutic value for AMD warrants in-depth investigation.

To investigate the therapeutic potential of SHD for AMD, we first identified 18 bioactive constituents targeting 157 unique proteins from its four herbal components (Da Huang, Hou Po, Qiang Huo, Zhi Shi) via the TCMSP database. Cross-referencing with 87 AMD-associated targets from OMIM and DisGeNET databases revealed six core intersection genes (ESR1, PON1, SOD1, APOB, VEGFA, IL6) using Venny 2.1. Subsequent PPI network analysis, functional enrichment, and pharmacological mapping indicated that MOL000006 (luteolin) from Zhi Shi likely modulates AMD angiogenesis by targeting VEGFA within the GO:0035239 tube morphogenesis pathway. Luteolin—a natural flavonoid in carrots, broccoli, and perilla—exerts anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumor effects42,43,44,45. It protects ARPE-19 cells from oxidative death, suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines, attenuates epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Nrf2/AKT/GSK-3β pathways46,47,48, and inhibits RPE fibrosis by inactivating Smad2/3/YAP signaling in laser-induced CNV models49. While these findings underscore luteolin’s therapeutic promise for AMD, its specific anti-angiogenic mechanism through VEGFA suppression remains unelucidated, necessitating rigorous experimental validation. To validate luteolin’s anti-angiogenic effects, we established a VEGF165-induced HUVEC model for functional analyses. Scratch assays—assessing horizontal migration as cells move directionally via cytoskeletal deformation50,51—revealed significantly reduced relative migration rates in luteolin-treated versus model groups (Fig. 5A–B, p < 0.05). Transwell assays quantifying vertical migration demonstrated markedly decreased migration rates with treatment (Fig. 5C–D, p < 0.05), collectively confirming luteolin’s inhibition of cellular motility. Invasion assays, evaluating matrix-degrading migration essential for neovascularization52,53, showed attenuated relative invasion rates in treated groups (Fig. 5E–F, p < 0.05). Tube formation assays—a gold standard for angiogenic tubulogenesis54,55—revealed substantially diminished relative lumen formation rates post-treatment (Fig. 5G–I, p < 0.05). These findings demonstrate that 25 µmol/L luteolin suppresses HUVEC angiogenesis. Given VEGFA’s role as an endothelial-specific mitogen driving proliferation/migration in wet AMD56,57, Western blot analysis confirmed significantly reduced VEGFA protein expression in luteolin-treated groups (Fig. 6, p < 0.05), mechanistically substantiating its anti-angiogenic action.

This study, for the first time, integrates network pharmacology with cellular experiments to reveal that luteolin, a key active component of SHD, may alleviate pathological angiogenesis in AMD by suppressing VEGFA expression. Notably, functional enrichment analysis suggested that the “tube morphogenesis” pathway, where VEGFA is involved, represents a potential core mechanism of luteolin, guiding our further investigation into angiogenic phenotypes. Phenotypic experiments yielded highly consistent results, collectively demonstrating that luteolin effectively inhibits the entire process of VEGF165-induced endothelial cell activation in vitro. Specifically, in both scratch wound and Transwell assays, luteolin treatment significantly reduced cell migration, strongly indicating that its target may lie upstream in the VEGF signaling pathway, regulating cytoskeletal reorganization and cell motility. Importantly, luteolin treatment reversed the VEGF165-induced upregulation of VEGFA protein expression. This finding not only validates the predictions of network pharmacology but also suggests that luteolin may function via a negative feedback loop: by suppressing VEGFA expression, it attenuates VEGF signaling output, ultimately inhibiting endothelial cell angiogenic activity. This provides a novel perspective on luteolin’s mechanism of action, distinguishing it from conventional anti-VEGF therapies (e.g., ranibizumab) that directly neutralize VEGF protein. Luteolin may act at the gene expression level, potentially yielding more sustained inhibitory effects. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, all experiments were conducted solely in HUVECs. While HUVECs are a classic model for angiogenesis research, their ability to fully recapitulate the complex pathological environment of choroidal endothelial cells (CECs) in AMD remains uncertain. Future studies should validate these findings in primary CECs or more complex in vitro models (e.g., co-culture systems with retinal pigment epithelial cells). Second, although luteolin showed no significant cytotoxicity at 25 µmol/L, we did not assess its long-term effects or potential off-target impacts on other retinal cells (e.g., photoreceptors). Most critically, the absence of in vivo data is a major limitation. Whether luteolin can effectively inhibit neovascularization in laser-induced CNV mouse models and penetrate the blood-retinal barrier to reach lesion sites are key determinants of its clinical translational potential, warranting further investigation.

Despite these limitations, this study establishes a feasible research paradigm for discovering novel AMD therapeutic strategies from traditional Chinese medicine formulations. By following a “network prediction-target screening-experimental validation” workflow, we delineated how the holistic action of SHD can be attributed to luteolin’s inhibition of VEGFA. This finding not only provides preliminary experimental support for luteolin as a candidate anti-AMD agent but also implies that other active components in SHD may synergistically target additional predicted nodes (e.g., ESR1, IL6), offering multi-faceted therapeutic benefits against AMD—a promising direction for future research.

Conclusion

Building on network pharmacology predictions that luteolin—a key component of Sanhua Decoction—may modulate AMD angiogenesis via VEGFA-associated signaling, our cellular assays and Western blotting experimentally demonstrated luteolin’s suppression of HUVEC neovascularization and VEGFA protein expression. Collectively, this study identifies luteolin as a promising candidate drug and proposes a novel therapeutic strategy for neovascular AMD, though further validation remains warranted..

Data availability

Raw data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

Wong, T. Y. et al. The natural history and prognosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 115 (1), 116–126 (2008).

Wong, W. L. et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2 (2), e106–e116 (2014).

Knobbe, C. A. & Stojanoska, M. The ‘Displacing foods of modern commerce’ are the primary and proximate cause of Age-Related macular degeneration: A unifying singular hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses. 109, 184–198 (2017).

Jensen, E. G. et al. Associations between the complement system and choroidal neovascularization in wet Age-Related macular degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 21(24). (2020).

Samelska, K. et al. Novel approach to antiangiogenic factors in age-related macular degeneration therapy. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 47 (1), 117–123 (2022).

Cox, J. T., Eliott, D. & Sobrin, L. Inflammatory complications of intravitreal Anti-VEGF injections. J. Clin. Med., 10(5). (2021).

Ochoa Hernández, M. E. et al. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation in age related macular degeneration: insights into the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Int. J. Mol. Sci., 26(8). (2025).

Mathis, T. et al. Characterisation of macular neovascularisation subtypes in age-related macular degeneration to optimise treatment outcomes. Eye (Lond). 37 (9), 1758–1765 (2023).

Chaudhuri, M. et al. Age-Related macular degeneration: an exponentially emerging imminent threat of visual impairment and irreversible blindness. Cureus 15 (5), e39624 (2023).

Yeo, N. J. Y. et al. Single-Cell transcriptome of wet AMD Patient-Derived endothelial cells in angiogenic sprouting. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23(20). (2022).

Bates, D. O. Vascular endothelial growth factors and vascular permeability. Cardiovasc. Res. 87 (2), 262–271 (2010).

Zheng, L. et al. Sanhua decoction: current Understanding of a traditional herbal recipe for stroke. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1149833 (2023).

YingHuang, G. S. S. et al. Mechanism of Sanhua Decoction in the Treatment of Ischemic Stroke Based on Network Pharmacology Methods and Experimental Verification. Biomed Res Int, 2022: 7759402. (2022).

Ni, Y. et al. Therapeutic effect of Sanhua Decoction on rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion and the associated changes in gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. PLoS One. 19 (2), e0298148 (2024).

Fu, D. L. et al. Sanhua Decoction, a classic herbal Prescription, exerts neuroprotection through regulating phosphorylated Tau level and promoting adult endogenous neurogenesis after cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion injury. Front. Physiol. 11, 57 (2020).

Wang, Y. K. et al. Application and mechanisms of Sanhua Decoction in the treatment of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. World J. Clin. Cases. 12 (4), 688–699 (2024).

Matías-Pérez, D. et al. Dietary sources of antioxidants and oxidative stress in age-related macular degeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1442548 (2024).

Machalińska, A. et al. Complement system activation and endothelial dysfunction in patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD): possible relationship between AMD and atherosclerosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 90 (8), 695–703 (2012).

UniProt. The universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D609–d617 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Network Pharmacology prediction and molecular docking-based strategy to explore the potential mechanism of Huanglian Jiedu Decoction against sepsis. Comput. Biol. Med. 144, 105389 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Decreased HLF expression predicts poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 27, e929333 (2021).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51 (D1), D638–d646 (2023).

Lu, S. et al. Bioinformatics analysis and identification of genes and molecular pathways involved in venous thromboembolism (VTE). Ann. Vasc Surg. 74, 389–399 (2021).

Shang, L. et al. Mechanism of Sijunzi Decoction in the treatment of colorectal cancer based on network Pharmacology and experimental validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 302 (Pt A), 115876 (2023).

Kouba, B. R., Altê, G. A. & Rodrigues, A. L. S. Putative Pharmacological depression and Anxiety-Related targets of calcitriol explored by network Pharmacology and molecular Docking. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 17(7). (2024).

Mobasheri, L. et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ferula assafoetida Oleo-Gum-Resin (Asafoetida) against TNF-α-Stimulated Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs). Mediators Inflamm. , 5171525. (2022).

Achour, M. et al. Luteolin modulates neural stem cells fate determination: in vitro study on human neural stem cells, and in vivo study on LPS-Induced depression mice model. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 753279 (2021).

Yang, R. et al. Apelin/APJ axis improves angiotensin II-induced endothelial cell senescence through AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Arch. Med. Sci. 14 (4), 725–734 (2018).

Hu, Y. et al. Exosomes from human umbilical cord blood accelerate cutaneous wound healing through miR-21-3p-mediated promotion of angiogenesis and fibroblast function. Theranostics 8 (1), 169–184 (2018).

Justus, C. R. et al. Transwell in vitro cell migration and invasion assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2644, 349–359 (2023).

Huang, X. Y. et al. Exosomal circRNA-100338 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis via enhancing invasiveness and angiogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39 (1), 20 (2020).

Ma, C. et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 35 promotes gastric cancer metastasis by increasing the stability of Snail1. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20 (3), 953–967 (2024).

Xu, W., Cao, L. & Liu, H. CAMK2D and complement factor I-Involved Calcium/Calmodulin signaling modulates sodium Iodate-Induced mouse retinal degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 66 (1), 63 (2025).

Thomas, C. J., Mirza, R. G. & Gill, M. K. Age-Related macular degeneration. Med. Clin. North. Am. 105 (3), 473–491 (2021).

Velilla, S. et al. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: review and update. J. Ophthalmol., 895147. (2013).

Hughes, A. E. et al. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration risk based on CFH, LOC387715/HTRA1, and smoking. PLoS Med. 4 (12), e355 (2007).

Celkova, L., Doyle, S. L. & Campbell, M. NLRP3 inflammasome and pathobiology in AMD. J. Clin. Med. 4 (1), 172–192 (2015).

李雯洁 三化汤及其拆方对大鼠脑缺血再灌注损伤的保护机制研究. (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Connotative analysis of the formulation of Sanhua Decoction in the treatment of stroke based on network Pharmacology. (2022).

Luo, S. et al. Application of omics technology to investigate the mechanism underlying the role of San Hua Tang in regulating microglia polarization and blood-brain barrier protection following ischemic stroke. J. Ethnopharmacol. 314, 116640 (2023).

Fleckenstein, M., Schmitz-Valckenberg, S. & Chakravarthy, U. Age-Related macular degeneration: A review. JAMA 331 (2), 147–157 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Luteolin protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting NF-κB-mediated inflammation and activating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses. Phytomedicine 59, 152774 (2019).

Cho, Y. C., Park, J. & Cho, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative effects of luteolin-7-O-glucuronide in LPS-Stimulated murine macrophages through TAK1 Inhibition and Nrf2 activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 21(6). (2020).

Ryu, S. et al. Effects of Luteolin on canine osteosarcoma: suppression of cell proliferation and synergy with cisplatin. J. Cell. Physiol. 234 (6), 9504–9514 (2019).

陈玉芬 木犀草素抑制脉络膜黑色素瘤细胞血管生成和血管生成拟态的机制研究. (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Luteolin Alleviates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transformation Induced by Oxidative Injury in ARPE-19 Cell via Nrf2 and AKT/GSK-3β Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2022: 2265725. (2022).

陈美玲 木犀草素对增殖性玻璃体视网膜病变的防治作用及机制研究. (2023).

Hytti, M. et al. Fisetin and Luteolin protect human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death and regulate inflammation. Sci. Rep. 5, 17645 (2015).

Zhang, C. et al. Luteolin inhibits subretinal fibrosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in laser-induced mouse model via suppression of Smad2/3 and YAP signaling. Phytomedicine 116, 154865 (2023).

Romano, D. J. et al. Tracking of endothelial cell migration and stiffness measurements reveal the role of cytoskeletal dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23(1). (2022).

Radstake, W. E. et al. The effects of combined exposure to simulated Microgravity, ionizing Radiation, and cortisol on the in vitro wound healing process. Cells, 12(2). (2023).

Pijuan, J. et al. In vitro cell Migration, Invasion, and adhesion assays: from cell imaging to data analysis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 7, 107 (2019).

Hulkower, K. I. & Herber, R. L. Cell migration and invasion assays as tools for drug discovery. Pharmaceutics 3 (1), 107–124 (2011).

Tahergorabi, Z. & Khazaei, M. A review on angiogenesis and its assays. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 15 (6), 1110–1126 (2012).

Moleiro, A. F. et al. A Critical Analysis of the Available In Vitro and Ex Vivo Methods to Study Retinal Angiogenesis. J. Ophthalmol., 3034953. (2017).

Ulker, E. et al. Ascorbic acid prevents VEGF-induced increases in endothelial barrier permeability. Mol. Cell Biochem., 412(1–2): 73 – 9. (2016).

Kaiser, S. M., Arepalli, S. & Ehlers, J. P. Current and future Anti-VEGF agents for neovascular Age-Related macular degeneration. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 13, 905–912 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaoting Li designed the study, Sichong Yang performed data collection and management; Sichong Yang and Dan Mu performed data analysis and interpretation; and Sichong Yang wrote, and Xiaoting Li reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This research has been reviewed by the Ethics Committee of The 92493 Military Hospital of PLA, and it is believed that the project meets the requirements for exemption from ethical review and agrees to exempt the project from review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Mu, D. & Li, X. Luteolin alleviates angiogenesis in HUVECs by inhibiting VEGFA expression: integrating network pharmacology and experimental validation. Sci Rep 16, 3706 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33839-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33839-1