Abstract

Facing declining conventional resources, the oil industry requires advanced methods to maximize recovery. Polymer flooding is a key technique, but its optimization is hindered by complex parameter interactions and the high computational cost of traditional simulation. This study presents a novel solution: a hybrid AI-Genetic Algorithm (GA) framework that integrates numerical simulation with machine learning for efficient optimization. A large dataset of 960 core-scale simulation cases was generated to analyze key parameters like permeability and polymer concentration. The core innovation was the development of two neural networks, a Feedforward Neural Network (FNN) and an Elman Recurrent Neural Network (E-RNN), to act as fast proxy models. The E-RNN proved superior for forecasting dynamic production data, achieving exceptional accuracy (R² > 0.99) by effectively capturing time-dependent behaviors. This high-fidelity E-RNN proxy was then coupled with a GA for multi-objective optimization. Results showed that maximum oil recovery is achieved by maximizing permeability, injection rate, and polymer concentration while minimizing reservoir heterogeneity. Crucially, economic optimization revealed a different strategy, favoring a short, intensive injection period to maximize profit, highlighting a key technical-economic trade-off. The study successfully validated the framework’s generalization capability. This work provides a powerful tool for accelerating polymer flooding design, with future efforts aimed at integrating laboratory data for calibration and scaling the application to full-field models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

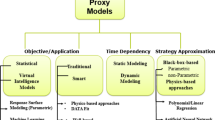

The global transition toward sustainable, low-carbon energy sources is a defining trend of our time. While the integration of renewables into energy portfolios advances, the inherent intermittency and forecasting challenges of these sources underscore the complexity of this shift. Within this broader energy landscape, and during this transition, optimizing the efficiency of existing hydrocarbon assets remains a critical industrial and economic imperative1. Global energy demand is escalating, driven by population growth and technological advancement, that spurs industrial expansion. It has been reported that worldwide energy consumption in 2022 was about 65% higher than in 2000 2. Concurrently, global oil consumption increased by 2.9 million barrels per day in 2022 compared to the previous year. The probability of discovering new, large-scale hydrocarbon resources is continually diminishing. Given that oil accounted for about 40% of the global energy supply in 2019, as reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA), enhancing production efficiency, specifically the oil recovery factor, in existing assets is imperative3. Since the realization of industrial hydrocarbon production, oil has emerged as one of the most significant global energy sources. In light of growing demand and the depletion of easily accessible reserves, heavy oil reservoirs have become a crucial alternative resource. A principal challenge in recovering such resources, particularly in ordinary-heavy oil reservoirs (oil viscosity between 100 and 10,000 cp.), is the low displacement efficiency of conventional methods like hot water flooding, primarily due to unfavorable oil-water mobility ratios. While various chemical agents (polymers, surfactants, alkalis) have been used as water-soluble viscosity reducers, they often face limitations regarding salinity, temperature stability, or effectiveness4. In recent years, the application of different polymers has become an attractive issue in various industries including the petroleum industry. The fluid adsorption process in different polymers is a vital circumstance in oil industry concepts such as enhanced oil recovrey (EOR)5. Polymer flooding is an EOR technique designed to improve the displacement efficiency of oil by water in reservoir formations. The process involves adding polymers to injection water to increase its viscosity. This improves oil recovery by stabilizing the displacement front and improving sweep efficiency. Additionally, polymer adsorption and plugging reduce permeability in swept zones, diverting flow into un-swept areas to mobilize trapped oil. Certain polymers also exhibit non-Newtonian rheological behavior, where their viscosity depends on the shear rate6,7,8. The success of a polymer flooding hinges on a thorough understanding of how design parameters, such as slug size, polymer concentration, and injection strategy, influence both ultimate recovery and economic performance. While traditional sensitivity analysis has been used to study individual parameters, it fails to capture the complex, interactive effects between variables that are critical for effective optimization. Furthermore, for project viability, two critical measures must be considered simultaneously: maximizing production gain (Net Present Value) and optimizing polymer efficiency. This inherently multi-objective problem requires advanced optimization approaches capable of identifying the optimal compromise between competing goals9. The oil and gas industry is increasingly leveraging sophisticated data-driven methodologies, fueled by the continuous acquisition of large-scale operational datasets10. This shift is driven by the complex and uncertain nature of hydrocarbon reservoirs, which necessitates advanced analytical techniques. Production and injection optimization are paramount for managing the reservoir performance and also maximizing oil recovery. However, a principal challenge in applying optimization directly to high-fidelity numerical simulation models is their prohibitive computational cost, especially for full-field models with many wells, as optimization routines typically require hundreds to thousands of simulation runs11. The oil and gas sector now continuously acquires vast operational datasets. However, the inherent complexity of hydrocarbon reservoirs, combined with the substantial volume, variety, and uncertainty of geoscientific data, demands sophisticated tools to integrate multi-disciplinary information, quantify uncertainty, and extract non-obvious, actionable insights. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a key discipline in this context. AI algorithms can process immense quantities of raw data to uncover implicit, previously unrecognized, and valuable relationships. This iterative process uses historical and real-time data to discover latent patterns and build predictive models to forecast future reservoir performance. For optimization tasks within this complex, high-dimensional space, stochastic methods are often preferred over traditional gradient-based algorithms. Techniques like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) are particularly valuable because of their robust ability to explore the entire solution space and avoid becoming trapped in local optima, thereby increasing the probability of finding a global or near-global optimum solution12,13,14. Nature-inspired algorithms have emerged as a preferred tool for tackling the complex optimization problems in polymer EOR. They are a class of metaheuristics that includes Evolutionary Algorithms and Swarm Intelligence, and they excel precisely where traditional methods struggle: they navigate rough, multi-modal objective functions without gradient information and effectively manage the operational constraints of the injection planning. While the reservoir engineering application of algorithms like PSO remains an active area of research, previous successes are encouraging. The hybridization of AI surrogates with optimizers like the GA has already demonstrated a marked ability to improve recovery factors and profitability15. Our study is positioned within this innovative trajectory, leveraging a hybrid AI-GA framework to build upon these established successes. To quantitatively characterize and predict this complex process, previous studies have employed methods ranging from numerical simulation to empirical models. For instance, Hou’s models combined with GA and support vector machine have been developed for the quantitative characterization and prediction of polymer flooding performance, demonstrating a viable data-driven approach16. Similarly, for Surfactant-Polymer (SP) flooding, Genetic Programming (GP) has been used to create accurate, simplified mathematical functions for predicting recovery factor and net present value (NPV), highlighting the potential of such methods to bypass complex physical descriptions17. Further advancing the field, sophisticated hybrid techniques like multi-objective global and local surrogate-assisted particle swarm optimization (MO-GLSPSO) have been developed to efficiently resolve conflicting objectives, such as maximizing oil production while minimizing polymer usage18. Other studies have framed polymer flooding as an optimal control problem, solved using hybrid GAs to determine the most profitable injection strategies19. Table 1 presents a summary of previous investigations into the integration of AI with optimization algorithms for water-based enhanced oil recovery methods.

This study establishes a comprehensive AI-driven workflow to optimize polymer flooding strategies by addressing three critical gaps in current optimization approaches. First, to overcome the limitations of static proxy models, we developed a dynamic Elman Recurrent Neural Network (E-RNN) that incorporates temporal memory, demonstrating superior accuracy in forecasting production profiles compared to traditional FNNs. Second, we bridge the crucial disconnect between technical and economic optimization by integrating a comprehensive economic model directly into the workflow. Finally, we resolve the computational bottleneck of traditional methods through a hybrid AI-GA framework that enables rapid multi-objective optimization while maintaining accuracy. The methodology integrates advanced numerical simulation with machine learning techniques, beginning with the generation of a comprehensive dataset of 960 core-scale simulation cases using reservoir simulator coupled with the MATLAB Reservoir Simulation Toolbox (MRST). This systematic evaluation of key geological and operational parameters, including permeability, porosity, injection rate, polymer concentration, and Dykstra-Parsons coefficient models the transition from secondary waterflooding to tertiary polymer flooding. Following data extraction and normalization of outputs such as oil recovery factor and water cut, the high-performing E-RNN architecture was integrated with a GA to form an optimization framework that balances maximal recovery efficiency with economic profitability through optimal injection scheduling and parameter configuration.

Methodology

This study establishes a comprehensive, AI-driven workflow to optimize polymer flooding strategies by integrating advanced numerical reservoir simulation with machine learning (ML) and evolutionary optimization techniques. Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive four-phase workflow developed in this study, which consists of: (1) Data Generation, involving structured sensitivity analysis and parallelized core-scale simulations to create a large synthetic dataset of 960 models; (2) Data Processing, where key performance indicators such as oil recovery factor and water cut are extracted and prepared for ML modeling through normalization; (3) Model Development, wherein different neural network architectures (FNN and E-RNN) are trained and evaluated to create a robust proxy for the simulator; and (4) Optimization, where the superior E-RNN proxy model is integrated with a GA to perform multi-objective optimization, balancing maximal oil recovery with economic profitability. This integrated AI-driven approach provides a powerful and efficient framework for determining optimal polymer injection parameters.

Numerical model setup

To ensure reproducibility, this section provides a comprehensive description of the synthetic, laboratory-scale numerical model used for polymer flooding simulation. The model was constructed and executed using the Eclipse 100 reservoir simulator coupled with the MATLAB Reservoir Simulation Toolbox (MRST) for workflow automation and data processing. The reservoir rock and fluid properties were derived from laboratory data for a heterogeneous sandstone reservoir ¹⁰,²³, while certain parameters were hypothetically based on assumptions appropriate for a synthetic study.

Grid configuration, initial and boundary conditions

The reservoir was discretized using a Cartesian grid of 40 × 40 × 1 cells, representing a physical domain of 100 cm (x) × 100 cm (y) × 50 cm (z). This single-layer configuration assumes negligible vertical flow effects, focusing on a two-dimensional areal displacement typical of core-scale studies. The model was initialized with the following conditions presented in Table 2:

Rock, fluid, and polymer properties

The model incorporated the following key properties for rock and fluid properties (Table 3):

Polymer model

The polymer flooding process was modeled considering viscosity enhancement and adsorption as functions of polymer concentration. The simulations assumed isothermal conditions and utilized a black-oil formulation.

Sensitivity analysis and experimental design

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to quantify the influence of five critical parameters on oil recovery and water cut: permeability, porosity, injection rate, polymer concentration, and the Dykstra-Parsons heterogeneity coefficient. Each variable was assigned a defined range (minimum and maximum values) and a variation level, which specifies the number of data points sampled within that range for statistical replication. The rationale for these ranges and levels is described here, with their specific values provided in Table 4.

Based on the variation levels presented in the table above, 960 models were planned for replication. Using Python software and the specified variables, the process of generating and constructing these 960 synthetic models was executed.

Model simulation process

Effective simulation necessitates a balance between high accuracy and computational speed. Processing the extensive number of models required for this study in a sequential manner would be prohibitively time-consuming. To address this, an automated workflow was developed to execute all simulations within the environment. This was achieved by integrating MRST with a reservoir simulator, which significantly enhanced workflow efficiency. The integration streamlined data handling, improved operational organization and precision, and drastically reduced the total simulation time. To further accelerate computation, a parallel processing framework was implemented in MRST. This approach maximizes computational efficiency by distributing the total workload across multiple processor cores, with each core independently processing a subset of the models. This strategy mitigates potential processing errors and complexities associated with inter-core coordination. The simulations were performed on a Core i7-12700 K processor, which features 12 cores (8 performance and 4 efficiency). This configuration allowed for the concurrent processing of multiple models, with each core handling a total of 80 models throughout the study. It is important to note that the efficacy of parallel computing can be constrained by high computational loads, large output file sizes, and storage I/O limitations. To prevent these bottlenecks from forcing sequential processing despite the parallel setup, the models were optimized to minimize complexity and unnecessary output data, ensuring efficient distribution across all available cores.

Data preprocessing

Simulation data was initially stored in proprietary binary formats. To facilitate external analysis, outputs were saved in a compressed ASCII format using the FMTOUT keyword, which reduces file size and accelerates post-processing. The key performance indicators, such as oil recovery factor and water cut, were then programmatically extracted from all 960 simulated models using the MRST toolbox. To ensure balanced learning, the input data was normalized to a uniform [0, 1] range via min-max scaling. Finally, the complete dataset was partitioned into 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing to enable robust model development and evaluation.

Data extraction

Given the extensive number of simulated models and the impracticality of manually extracting results, specialized computational tools are required to automate the retrieval of essential data from simulation outputs. To this end, the MRST was used in this study. Its modular architecture comprises a core library and approximately 65 supplementary modules, which encompass discretization methods, solvers, physical models, simulators, and flow utilities33. A particularly relevant feature of MRST is its capacity to import both initial and results data generated by reservoir simulator. For this study, oil recovery and water cut results from all 960 simulated models were programmatically extracted and stored using the MRST toolbox.

To develop a robust model that accurately captures the relationship between input and output variables, it is necessary to address features with disparate scales. For instance, polymer concentration ranges from 0 to 3600 ppm, while permeability varies from 100 to 3000 mD. Such a significant discrepancy in scale can cause machine learning algorithms, particularly those like linear regression and neural networks that rely on weighted input values, to become biased towards features with larger numerical ranges. This bias can result in disproportionate adaptation and suboptimal model performance. To mitigate this issue, input data must be normalized prior to model training, as recommended by Hemmati-Sarapardeh et al. 34. Normalization improves the training efficacy and convergence of neural networks. In this study, the min-max scaling method was applied, whereby the range of each input parameter was individually transformed using Eq. (1). This process rescales all features to a uniform range of [0, 1], ensuring balanced contribution during the learning process.

In the above equation, \(\:{\text{V}\text{a}\text{l}}_{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}\) and \(\:{\text{V}\text{a}\text{l}}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\) represent the minimum and maximum values of the parameter within the studied range, respectively. \(\:{\text{V}\text{a}\text{l}}_{\text{n}\text{o}\text{w}}\) is the variable’s value before normalization, and \(\:{\text{V}\text{a}\text{l}}_{\text{n}\text{e}\text{w}}\) is the new value after normalization, now ready for use in the neural network.

Artificial neural networks (ANN)

ANN models are widely employed to address diverse challenges in reservoir engineering. Their applications encompass reservoir characterization, infill well placement optimization, virtual well test interpretation, and the design and optimization of field development strategies, among others. Commonly utilized ANN architectures within the field include FNN, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), RNN, Radial Basis Function Neural Networks (RBFNN), and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS)24,30,35.

Feedforward neural network (FNN)

The FNN represents one of the fundamental architectures in ANNs. In an FNN, information propagates unidirectionally from the input layer, through any hidden layers, to the output layer, forming an acyclic graph. The input data is processed sequentially; at each hidden layer, a transformation is applied by computing the weighted sum of the inputs and subsequently passing this value through a non-linear activation function. This forward propagation continues until the final output layer, where the network’s prediction is generated36. For a network containing a single hidden layer, the final output can be mathematically represented by Eq. (2):

In Eq. (2), \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{k}}\) represents the matrix of input values, \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{k}\text{j}}^{\left(2\right)}\) denotes the weight matrix between the input layer and the hidden layer, \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{j}\text{i}}^{\left(1\right)}\) denotes the weight matrix between the hidden layer and the output layer, and \(\:\text{f}\) represents the applied activation function. The activation function applied to the hidden layers may differ from that used in the output layer.

Recurrent neural network (RNN)

A significant limitation of FNNs is their exclusive reliance on current input data for learning and prediction. This architecture is ineffective for processing sequential or time-dependent data where contextual information from previous steps is critical. For instance, accurately interpreting the meaning of a word within a sentence requires memory of the preceding words and their syntactic relationships37.

RNNs address this limitation by incorporating a form of memory, enabling them to utilize historical information to inform the analysis of current inputs. Their unique structure allows them to maintain an internal state that captures relevant context from prior elements in a sequence (Fig. 2). While similar in structure to FNNs, RNNs are distinguished by a feedback loop in which the output from each processing step is fed back into the network as an additional input for the subsequent step. This recurrent connection allows the network to propagate information across sequence positions, making it particularly well-suited for tasks involving sequential data.

More precisely, an RNN incorporates a context layer in addition to the standard hidden layer (Fig. 3). The activations from the hidden layer are weighted and stored in this context layer, where they serve as a memory of previous states. For each subsequent time step in the sequence, the input to the network consists of both the new primary input data and the context information from the previous step. These combined inputs are then processed by the hidden layer. The outputs of this hidden layer are, in turn, stored in the context layer to influence the following step. Consequently, while the initial step processes a number of inputs equal to the number of primary parameters, every subsequent step processes an input vector that is the sum of the primary parameters and the number of neurons in the context layer.

Following architectural design, both the FNN and E-RNN were optimized through a structured hyperparameter tuning process. Key parameters, including the number of hidden layers (1–3), neurons per layer (10–50), activation functions (Tanh, ReLU, Sigmoid), and training algorithms (Levenberg-Marquardt, Bayesian Regularization), were evaluated iteratively based on validation performance. A single hidden layer with 20 neurons and the Tanh activation function, trained using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm with early stopping, yielded the best balance of accuracy and efficiency for both networks. All input and output variables were normalized to [0, 1] via min-max scaling prior to training.

Network architecture and training strategy for dynamic prediction

The primary Objective of developing the proxy models was to forecast complete production profiles, specifically the time-dependent Oil Recovery Factor (FOE) and Water Cut (WCT) using static reservoir and operational parameters as inputs.

Input and Output Vector Structure: For each simulation case, the neural network input was a static vector, \(\:\text{x}\), comprising the five key parameters defined in the sensitivity analysis:

where \(\:\text{k}\) is permeability (md), \(\:\phi\:\) is porosity, \(\:\text{Q}\) is injection rate (scc/hr), \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{poly}}\) is polymer concentration (ppm), and \(\:{V}_{\text{DP}}\) is the Dykstra-Parsons coefficient.

The target output was the full time-series profile of a dynamic variable. The simulation period of 3000 h was discretized into 150 uniform steps of 20 h each. Consequently, the target was a 150-dimensional vector:

Separate networks were trained to predict the FOE and WCT profiles. Thus, for each of the 960 simulation cases, a single training sample was formed by pairing the static input vector \(\:\text{x}\) with its corresponding dynamic output vector \(\:\text{y}\).

Architectural approaches for Temporal data processing

The fundamental distinction between the FNN and E-RNN networks lies in their methodology for processing the time-series output.

-

FNN Approach: The FNN will treat the prediction as a large multiple-input, multiple-output regression problem. It maps the static input vector directly to the entire 150-point output vector in a single step. While capable of learning the general shape of the production curves, this architecture inherently lacks a mechanism to model temporal causality, as it does not explicitly utilize the sequential order of the data points.

-

E-RNN Approach: The E-RNN is designed to handle sequential data through an internal “memory” mechanism. Its context layer stores activations from the previous time step and feeds them back as part of the input for the subsequent prediction. In this study, the E-RNN was trained in a recursive, autoregressive manner:

-

1.

The static input vector is presented to the network at the first time step.

-

2.

The network predicts the output for \(\:{\text{t}}_{1}\).

-

3.

The internal state of the context layer is updated.

-

4.

For the prediction of \(\:{\text{t}}_{2}\), the network uses this updated internal state in conjunction with the original static input parameters.

This recursive process enables the E-RNN to learn the dynamic evolution of the displacement process. The “memory” of past production states directly informs future predictions, offering a more physically realistic representation of polymer flooding.

Elman and Jordan recurrent neural networks

The elman recurrent neural Network (E-RNN) is a globally recognized and widely utilized recurrent architecture, first introduced by Jeffrey Elman38. It is based on a feedforward structure augmented with recurrent connections. Both the Elman and Jordan networks represent foundational architectures within the broader category of RNNs. The primary distinction between them lies in the composition of their context layers. The general principles of RNNs described thus far pertain specifically to the Elman network. In this architecture, the context layer receives its input from the hidden layer activations of the previous time step. In contrast, the Jordan recurrent network supplies its context layer from the output values of the previous time step (Fig. 4).

Genetic algorithm (GA)

The GA is an intelligent, stochastic optimization method inspired by natural selection and genetics. It operates without requiring derivative or gradient information, making it highly versatile for complex, nonlinear problems. The GA begins with a randomly generated population of candidate solutions, each encoded as a chromosome composed of genes representing optimization variables. Through an iterative process, the population evolves using genetic operators, selection, crossover, and mutation, to progressively improve solutions. Key strengths of the GA include its ability to converge toward global optima (avoiding local solutions), parallelizability for accelerated computation, effectiveness in high-dimensional search spaces, and robustness in handling discontinuous or complex objective functions. These attributes have led to its widespread adoption across scientific and industrial domains. In this study, the GA is employed to optimize polymer flooding parameters by efficiently exploring the solution space and identifying configurations that maximize recovery and profitability39,40. A simplified schematic of the GA is presented in Fig. 5. In the GA framework, a candidate solution is represented as a chromosome, which is composed of multiple genes. Each gene corresponds to an optimization variable; for instance, a problem with five input variables would be encoded using chromosomes of five genes.

Optimization framework and control vectors

The GA was employed to optimize polymer flooding performance under two distinct scenarios. In both scenarios, the optimization aimed to find the optimal control vector, \(\:\text{u}\), composed of five key decision variables within defined search spaces. The control variables and their optimization boundaries were defined based on the ranges used in the initial sensitivity analysis (Table 4) to ensure physical realism and consistency with the trained proxy models’ domain of applicability. Control Variables and Optimization Boundaries are defined in Table 5:

Optimization scenarios and objective functions

The optimization process was conducted under two key scenarios to address both technical and economic performance metrics. The first scenario targeted the maximization of the Ultimate Oil Recovery Factor, while the second focused on maximizing Economic Profitability. The specific formulations for the objective function, control vector, and system constraints for each scenario are detailed in Table 6.

Subsequently, the associated costs of polymer injection and water injection are computed at each time step using Eq. (6) and Eq. (7), respectively. These economic metrics are incorporated into the fitness evaluation to determine profitability.

\(\text{Cos} t_{{water\left( t \right)}}\) = \({\text{Price}}_{{water}}\) \(\:\times\:\)Rate \(\:\times\:\)t

In Eq. (6), \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{p}\text{o}\text{l}\text{y}}\) is the polymer concentration in gr/cc, \(\:{\text{P}\text{r}\text{i}\text{c}\text{e}}_{\text{p}\text{o}\text{l}\text{y}}\) is in dollars/gr, Rate is in cc/hr, and t is the injection time in hours. Also, in Eq. (7), \(\:{\text{P}\text{r}\text{i}\text{c}\text{e}}_{\text{w}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{r}}\) is in dollars/cc. The total cost is calculated using Eq. (8):

In Eq. (8), \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}\text{s}\text{t}}_{\text{w}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{r}\left(\text{t}\right)}\) includes produced water handling and treatment, and \(\:{\text{C}\text{o}\text{s}\text{t}}_{\text{p}\text{o}\text{l}\text{y}\left(\text{t}\right)}\) is the cost of polymer injection. In this scenario, the revenue obtained comes from oil production. To calculate the amount of oil produced, the initial oil in place before the start of the simulation must first be calculated. Equation (9) is used to calculate the initial oil in place:

In the above equation, \(\:{\text{V}}_{\text{o}\text{i}}\) is the initial oil volume in cc, \(\:{\text{V}}_{\text{b}}\) is the total core volume in cc, ∅ is the core porosity, and \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{o}\text{i}}\) is the initial oil saturation. The oil revenue at time t is calculated using Eq. (10):

In Eq. (10), \(\:{\text{F}\text{O}\text{E}}_{\left(\text{t}\right)}\) is the oil recovery factor at time t, \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{o}}\) is the oil formation volume factor in bbl/STB, and \(\:{\text{P}\text{r}\text{i}\text{c}\text{e}}_{\text{o}\text{i}\text{l}}\) is the oil price in dollars/cc. To identify the optimal injection duration, profitability must be calculated across all time intervals using the specified equations. The time interval corresponding to the maximum profitability is subsequently returned as the chromosome evaluation criterion to the GA 32,41.

Genetic algorithm implementation

The GA was configured with parameters selected through preliminary testing to balance convergence speed and solution quality. It was configured with a population size of 20 candidate solutions per generation, a maximum of 1000 generations as a stopping criterion to limit computation time, and 5 genes per chromosome corresponding to the five control variables being optimized. The fitness evaluation was scenario-dependent: for Scenario 1, it was defined as the final recovery factor at 3000 h, while for Scenario 2, it was the maximum net present value profit across all time steps. Convergence was deemed achieved when the improvement in the best fitness value between successive generations fell below a tolerance of 1 × 10⁻⁶ or when the maximum generation count of 1000 was reached. The combination of the genetic algorithm and the proxy model is shown in the flowchart below (Fig. 6):

Results and discussion

This section details the data, methodology, results, and analysis of the neural network systems. The initial simulation model data is first reviewed, followed by a rigorous post-processing evaluation to validate model performance and utility. The predictive accuracy of the FNN and E-RNN was quantitatively assessed using the coefficient of determination (R²), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Their generalization capability was tested on both a known scenario (Model 1) and a completely unseen scenario (Model 2). The architectures were implemented with maximal functional parity to ensure a direct comparison, with the superior performance of the E-RNN demonstrating the significant impact of incorporating temporal dependencies. Finally, the obtained value of the models was confirmed through optimization, where the hybrid AI-GA framework was applied to maximize both ultimate oil recovery and economic profitability.

Initial modeling data

The data used for the initial core-scale modeling can be categorized into three distinct sections: structural model data, reservoir rock and fluid properties data, and rock properties under study. The rock and fluid properties, as well as the polymer properties, were set according to the reference13,42. The numerical model was constructed with a grid of 40 × 40 × 1 cells, representing a physical domain of 100 cm (x) by 100 cm (y) by 50 cm (z). The initial conditions were set at an irreducible water saturation (\(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{w}\text{i}}\)) of 0.31 and a reservoir pressure (\(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{i}}\)) of 102 atm. Production was governed by a constant bottom-hole pressure (BHP) constraint of 100 atm, and the simulation was executed over 150 time steps, each with a 20-hour duration.

Oil recovery and water cut prediction

Two neural network architectures were employed to predict the oil recovery factor curve: an E-RNN and a FNN. The configuration settings for both models were identical, with the only distinction being the E-RNN’s utilization of past information (memory) in its learning process, a feature absent in the FNN. The data was partitioned for the learning process of both networks using a 70% training, 20% validation, and 10% testing split. The data selection for training was randomized. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used for training, and the MSE and MAE metrics were employed to evaluate performance. As illustrated in Fig. 7, The FNN (b) demonstrates a straightforward, unidirectional flow of information from the input layer (5 parameters), through a single hidden layer (20 neurons), to the output layer (150 time steps of recovery factor). In contrast, the E-RNN (a) incorporates a critical feedback loop from the hidden layer to a context layer, which then feeds back into the hidden layer at the next time step. This recurrent connection, visually emphasized in the diagram, is the fundamental component that allows the E-RNN to capture temporal dependencies, giving it a “memory” that the FNN lacks.

Furthermore, the performance of the E-RNN and the FNN in estimating the recovery factor curve is demonstrated in Figs. 8 and 9. Figure 8 shows a scatter plot of the E-RNN’s predicted oil recovery factor against the corresponding simulated (true) values for all 150 time steps. The near-perfect alignment of data points along the 45-degree line (y = x) indicates an almost one-to-one match between predictions and simulations. The high R² value (0.999) quantitatively confirms that the E-RNN proxy model can replicate the simulator’s output for oil recovery with remarkable fidelity, capturing the entire production profile’s nonlinear behavior.

In Fig. 9, While the data points generally cluster around the 45-degree line, indicating decent accuracy, a closer inspection reveals a slightly wider scatter compared to the E-RNN in Fig. 8. However, the FNN model was also able to capture the complex, time-dependent dynamics of the displacement process.

In this study, Model 1 corresponds to the configuration selected from within the dataset used for the learning process, whereas Model 2 represents a scenario outside of this training data. As detailed in Table 7 the primary distinction between these two models is their respective injection rates.

The high predictive accuracy indicated by R² values approaching unity, particularly for the E-RNN, could raise concerns regarding potential overfitting. To ensure model robustness and generalizability, several precautionary measures were implemented. The dataset was rigorously partitioned into independent training (70%), validation (20%), and testing (10%) subsets. The validation set was used for early stopping during training, halting the learning process once validation error ceased to improve. Moreover, the models were evaluated on a completely unseen scenario (Model 2), where the E-RNN maintained strong performance (R² = 0.996 for oil recovery, 0.979 for water cut), confirming its ability to generalize beyond the training domain. These steps collectively support that the reported high accuracy reflects genuine learning of the underlying physical relationships rather than memorization of training data.

Figures 10 and 11 present a comparison of the network output and simulation results (recovery factor) for both Model 1 and Model 2.

In Fig. 11a, the E-RNN prediction curve for Model 1 is virtually indistinguishable from the simulation results, confirming excellent learning. In Fig. 11b for Model 2 (unseen data) which is the blind test; it shows that the E-RNN prediction closely tracks the simulation curve throughout the entire 3000-hour period. While minor deviations may be visible, the model accurately captures all major trends, including the initial rise, the inflection point, and the late-time plateau, proving its robustness as a reliable proxy for optimization tasks involving new scenarios.

Figure 10 provides a direct contrast to Fig. 11, highlighting the weaker performance of the FNN. For Model 1 (Fig. 10a), the FNN performs well, showing a good fit to the simulation data. However, for the unseen Model 2 (Fig. 10.b), the FNN’s prediction curve shows deviations from the simulator’s output. These errors are particularly pronounced in the mid-to-late time periods, where the FNN fails to accurately model the flood’s efficiency, likely because it cannot utilize the historical production data that the E-RNN’s memory mechanism provides. This visually underscores the FNN’s poorer generalization performance.

Figures 12 and 13 present the output results of the network and simulation results (water cut) for both Model 1 and Model 2.

Water cut is a challenging parameter to predict due to its sharp changes. Figure 13 evaluates the E-RNN’s performance on this key metric. The E-RNN successfully captures the overall trend of water cut development, including the timing of the initial water breakthrough and the subsequent rise. For Model 2 (Fig. 13.b), while there might be a slight over- or under-prediction during the transition phase, the model’s prediction remains qualitatively and quantitatively reliable (R² = 0.979), demonstrating its utility for forecasting water production, which is crucial for economic calculations.

The scatter plot in Fig. 12 shows a much wider spread of points compared to the oil recovery factor plots, and the R² value is significantly lower (e.g., 0.833 for Model 2). Many data points, particularly at mid-range water cut values, fall far from the ideal line. This visual evidence confirms that the FNN is a weaker predictor for the dynamic, time-sensitive water cut profile, as it cannot effectively learn the sharp, history-dependent transitions characteristic of water breakthrough.

The regression results of the two networks are included in Table 8.

As evidenced by the data presented in the accompanying Table 8, both networks demonstrate a high degree of predictive accuracy for Model 1, with performance differences remaining marginal across all metrics. The E-RNN achieves superior accuracy, as reflected by an R² of 0.999, an MSE of 3.24 × 10⁻⁶, and an MAE of approximately 0.0014 for oil recovery factor prediction. In contrast, the regression analysis for Model 2 reveals a decline in performance for both networks, characterized by a decrease in R² and increases in both MSE and MAE. Despite this overall reduction, the E-RNN remains the most accurate model, registering an R² of 0.996, an MSE of 8.74 × 10⁻⁵, and an MAE of approximately 0.0075 for oil recovery. A comparative analysis of the results for oil recovery factor and water cut curve prediction indicates a significant reduction in predictive accuracy for both architectures when estimating water cut behavior, with the FNN showing notably higher MAE (0.042) for Model 2. Furthermore, while both networks maintain strong performance on previously observed data (Model 1), their accuracy diminishes when applied to unseen data (Model 2), as confirmed by the elevated MAE values. Nevertheless, the E-RNN continues to deliver statistically reliable predictions, as visually corroborated by Figs. 11 and 13. Conversely, the FNN exhibits weaker generalization, despite demonstrating competitive learning performance on the training data.

Prediction of polymer front breakthrough time

In this section, E-RNN and FNN are used to achieve a more accurate estimation of the polymer front breakthrough time at the production well. The accuracy results of the E-RNN and FNN in predicting the polymer front arrival time for Models 1 and 2 are shown in Table 9.

The results demonstrate that both network architectures achieve high predictive accuracy for Model 1. The E-RNN demonstrates good performance with a marginal deviation of 0.122%, outperforming the FNN which exhibits a 0.255% deviation. A weaker performance in predictive accuracy is observed for both networks when applied to Model 2, although E-RNN maintains a comparative advantage with an error of 13.077% versus the FNN’s error of 13.155%. This pronounced contrast between the models’ performance on in-sample (Model 1) versus out-of-sample (Model 2) data indicates that while both architectures successfully learned the training distribution, they exhibit limited generalization capability when presented with novel data scenarios beyond the original training domain.

Optimization using genetic algorithm

This section details the application of a GA to optimize polymer flooding performance under two distinct scenarios. The first scenario (Sect. 3.3.1) focuses on maximizing the ultimate oil recovery factor, while the second (Sect. 3.3.2) introduces economic constraints to determine the most profitable polymer injection strategy, with a specific emphasis on optimizing the injection timing. Leveraging the high predictive accuracy of the previously validated neural networks (FNN and E-RNN), the GA was employed to evolve an optimal set of five key reservoir parameters: permeability, porosity, injection rate, polymer concentration, and the heterogeneity coefficient.

Optimization of maximum oil recovery factor

In the first scenario, a GA was employed to identify the optimal model for achieving the maximum oil recovery factor. The values and configurations associated with the GA are presented in Table 10.

Building upon the established high predictive accuracy of the FNN for extrapolating beyond the training dataset, as validated in preceding sections, a refined (filtered) version of this network was employed to optimize the maximum oil recovery factor. The optimization process defined five key reservoir parameters as decision variables for the GA: permeability, porosity, injection rate, polymer concentration, and the heterogeneity coefficient. These parameters constituted the fundamental genetic material (genes) for the evolutionary optimization procedure. The convergence behavior and enhanced predictive precision achieved through successive generations of the algorithm are demonstrated in Fig. 14, which depicts the progressive improvement in estimating the maximum oil recovery.

This plot tracks the convergence of the GA towards the maximum oil recovery factor over 1000 generations. The curve shows a rapid, steep increase in the best fitness value (recovery factor) during the initial 200 generations, indicating an effective global exploration of the parameter space. The rate of improvement then gradually slows, transitioning into a phase of local refinement. The curve eventually plateaus, signifying that the algorithm has converged to the optimal solution, a maximum recovery factor of 0.59, confirming that the GA has thoroughly exploited the solution space and identified the best possible configuration for technical performance. The optimization results are presented in Table 11.

Analysis of Table 11 indicates that the maximum oil recovery factor, representing the optimal reservoir development strategy is attained under conditions where permeability, injection rate, and polymer concentration are maximized, and porosity and heterogeneity coefficient are minimized. The resultant maximum recovery factor, which remains within the bounds of the training data parameters (Table 4), was determined to be 0.59.

Optimization of polymer injection timing with 5 variables

In the second scenario, a GA was implemented to optimize the economic model by incorporating injection timing as a key variable. The GA was configured using the parameters detailed in Table 10. A Dycstra-Parsons coefficient of 0.4 was considered in this scenario. Economic inputs for injection and production operations, including polymer and water injection costs alongside oil production revenue, were sourced from the established reference32. The operational cost and revenue assumptions applied in the simulation were defined by a water injection cost of 0.842 $/bbl, a polymer injection cost of 2.50 $/kg, and an oil production value of 46 $/bbl32.

Prior analyses have validated the exceptional predictive accuracy of E-RNN in extrapolating oil recovery factor curves beyond the training dataset. Leveraging this demonstrated capability, the E-RNN architecture was implemented to determine the economically optimal production model with injection timing optimization. The GA framework, incorporated five key reservoir parameters as decision variables: permeability, porosity, injection rate, polymer concentration, and heterogeneity coefficient. These parameters constituted the fundamental genetic material for the evolutionary optimization process, with chromosome fitness evaluated through maximum profitability metrics. Figure 15 demonstrates the progressive refinement in identifying the most profitable injection timing strategy across successive generations, illustrating the algorithm’s convergent behavior toward an optimized solution. The y-axis represents the maximum NPV profit found in each generation. Similar to Fig. 14, the curve shows a swift ascent in early generations as high-profit regions are discovered. The convergence pattern demonstrates the GA’s effectiveness in navigating the complex economic objective function, which incorporates time-dependent costs and revenues. The plateau indicates the successful identification of the optimal economic strategy.

Figure 16 illustrates the relationship between profit and injection time for the specified model.

Figure 16 is a pivotal figure that reveals the core technical-economic trade-off in polymer flooding. The plot shows profit (y-axis) versus injection time (x-axis). It visually demonstrates that profit does not increase monotonically with time or oil recovery. Instead, it peaks sharply at a specific, relatively short injection time (300 h). After this peak, the marginal cost of continued polymer injection outweighs the revenue from the additional, slowly produced oil, causing the net profit to decline. This graph provides the fundamental economic justification for optimizing injection timing and powerfully argues against simply running floods until no more oil can be recovered. The optimization results are presented in Table 12.

As detailed in Table 12, the GA converged on an optimal configuration maximizing net present value profit, which is aligned with scenario 1, characterized by maximized permeability, injection rate, and polymer concentration, coupled with minimized porosity and heterogeneity. The critical differentiation emerges in the optimized injection duration, which was determined to be 300 h. At this operational point, the recovery factor was calculated at 0.4411. While extended operation to 3,000 h yields a higher ultimate recovery factor of 0.5942, economic analysis reveals that the net present value profit peaks at 300 h and subsequently declines, ultimately resulting in a net economic loss by the 3,000-hour endpoint.

Conclusions

This study successfully developed and validated a hybrid AI-Genetic algorithm framework for optimizing polymer flooding strategies in a heavy oil, sandstone reservoir. The work yields the following key findings:

-

It demonstrated high accuracy in predicting time-series production data, using the Elman Recurrent Neural Network (E-RNN) as a superior proxy model for dynamic forecasting, achieving coefficients of determination (R²) of 0.996 and 0.975 for oil recovery factor and water cut, respectively, on blind test data. Its incorporation of temporal memory proved critical for capturing the complex displacement dynamics of polymer flooding.

-

While the FNN demonstrated weaker performance for predicting full production profiles (e.g., R² of 0.833 for water cut on blind data), it achieved accuracy comparable to the E-RNN for estimating single-point outcomes like polymer breakthrough time (13% error). This indicates its potential utility for rapid screening of specific, time-insensitive parameters.

-

Optimization for maximum oil recovery consistently prescribed maximizing permeability, injection rate, and polymer concentration while minimizing heterogeneity. In contrast, optimization for net present value profit converged on a short, intensive injection period of 300 h to maximize returns, even though this recovered less oil (44%) than the ultimate recovery factor (59%). This highlights the critical necessity of incorporating economics into polymer EOR design.

-

By integrating a proxy model with a robust evolutionary algorithm, this workflow enables rapid, multi-objective optimization for polymer EOR that balances technical performance with economic profitability, offering a significant advantage over traditional, computationally intensive methods.

-

This study established that for comprehensive polymer flooding optimization involving dynamic responses, the E-RNN is an essential component, while the simpler FNN can be used for rapid scalar outcome estimation. Ultimately, the AI-driven approach must be guided by economic constraints to generate practically viable development strategies.

-

The robust AI-GA framework developed in this study, provides a foundation for evolving from a prototype to field-ready technology. Future work will integrate laboratory core-flood data to calibrate the model and enhance its physical credibility. Subsequently, it will be deployed on complex field-scale models incorporating real-world constraints, maturing into a practical decision-support tool. Ultimately, integration with advanced AI techniques like deep reinforcement learning could enable a transformative shift from periodic optimization to real-time, closed-loop reservoir management, reshaping the future of intelligent hydrocarbon recovery.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study will be available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \({\text{B}}_{\text{O}}:\) :

-

Oil Formation Volume Factor (bbl/STB)

- \({\text{C}}_{\text{poly}}:\) :

-

Polymer Concentration (gr/cc)

- \({\text{Cost}}_{\text{poly}(\text{t})}:\) :

-

Cost of Polymer Injection at time t ($)

- \({\text{Cost}}_{\text{total}(\text{t})}:\) :

-

Total Cost at time t ($)

- \({\text{Cost}}_{\text{water}(\text{t})}:\) :

-

Cost of Water Injection at time t ($)

- \({\text{FOE}}_{(\text{t})}:\) :

-

Oil Recovery Factor at time t

- \({\text{Income}}_{\text{oil}(\text{t})}:\) :

-

Oil Revenue at time t ($)

- \({\text{P}}_{\text{i}}:\) :

-

Initial Pressure (atma)

- \({\text{Price}}_{\text{oil}}:\) :

-

Oil Price ($/cc)

- \({\text{Price}}_{\text{poly}}:\) :

-

Polymer Price ($/gr)

- \({\text{Price}}_{\text{water}}:\) :

-

Water Price ($/cc)

- \({\text{S}}_{\text{oi}}:\) :

-

Initial Oil Saturation

- \({\text{S}}_{\text{wi}}:\) :

-

Initial Water Saturation

- t:

-

Time hours (hr)

- \({\text{Val}}_{\text{max}}:\) :

-

Maximum value of a parameter (for scaling)

- \({\text{Val}}_{\text{min}}:\) :

-

Minimum value of a parameter (for scaling)

- \({\text{Val}}_{\text{new}}:\) :

-

Normalized value of a parameter (after scaling)

- \({\text{Val}}_{\text{now}}:\) :

-

Current value of a parameter (before scaling)

- \({\text{V}}_{\text{b}}:\) :

-

Bulk Volume (of the core) (cc)

- \({\text{V}}_{\text{oi}}:\) :

-

Initial Oil in Place (cc)

- \({\text{w}}_{\text{ji}}^{\left(1\right)}:\) :

-

Weight matrix between hidden layer and output layer

- \({\text{w}}_{\text{ji}}^{\left(2\right)}:\) :

-

Weight matrix between input layer and hidden layer

- \({\text{x}}_{\text{k}}:\) :

-

Matrix of input values to the neural network

- \({\text{y}}_{\text{i}}:\) :

-

Output of the neural network

- ∅:

-

Porosity

- AI:

-

Artificial Intelligence

- ANN:

-

Artificial Neural Network

- ANFIS:

-

Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System

- BHP:

-

Bottom-Hole Pressure

- CNN:

-

Convolutional Neural Network

- EOR:

-

Enhanced Oil Recovery

- E-RNN:

-

Elman Recurrent Neural Network

- FNN:

-

Feedforward Neural Network

- FOE:

-

Oil Recovery Factor

- GA:

-

Genetic Algorithm

- IEA:

-

International Energy Agency

- MSE:

-

Mean Squared Error

- NPV:

-

Net Present Value

- PF:

-

Polymer Flooding

- PSO:

-

Particle Swarm Optimization

- RBFNN:

-

Radial Basis Function Neural Network

- RF:

-

Recovery Factor

- RNN:

-

Recurrent Neural Network

- WCT:

-

Water Cut

References

Velasquez, J. D., Cadavid, L. & Franco, C. J. Intelligence techniques in sustainable energy: analysis of a decade of advances. Energies 16 (19), 6974 (2023).

Pali, F. et al. Energy Transitions over Five Decades: A Statistical Perspective on Global Energy Trends. Computers 14 (5), 190. (2025).

Arouri, M. & Gomes, M. Energy and economic growth: introduction and roadmap. In Handbook on Energy and Economic Growth, Edward Elgar Publishing: ; 1–7. (2024).

Li, X. et al. A Thermo-Stable Polymeric Surfactant for Enhanced Heavy Oil Recovery via Hot Water Chemical Flooding. Langmuir (2025).

Amiri-Ramsheh, B., Nait Amar, M., Shateri, M. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. On the evaluation of the carbon dioxide solubility in polymers using gene expression programming. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 12505 (2023).

Khosravi, R., Chahardowli, M. & Simjoo, M. Smart Water–Polymer Hybrid Flooding in Heavy Oil Sandstone Reservoirs: A Detailed Review and Guidelines for Future Applications (Energy & Fuels, 2024).

Saboorian-Jooybari, H., Dejam, M. & Chen, Z. Heavy oil polymer flooding from laboratory core floods to pilot tests and field applications: Half-century studies. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 142, 85–100 (2016).

Saboorian-Jooybari, H., Dejam, M. & Chen, Z. In Half-century of heavy oil polymer flooding from laboratory core floods to pilot tests and field applications, SPE Canada heavy oil technical conference, OnePetro: (2015).

Ekkawong, P., Han, J., Olalotiti-Lawal, F. & Datta-Gupta, A. Multiobjective design and optimization of polymer flood performance. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 153, 47–58 (2017).

Rabiei, M., Gupta, R., Cheong, Y., Sanchez Soto, G. & Conference In Transforming data into knowledge using data mining techniques: application in water production problem diagnosis in oil wells, SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas and Exhibition, SPE: ; pp SPE-133929-MS. (2010).

Al-Aghbari, M. & Gujarathi, A. M. Hybrid optimization approach using evolutionary neural network & genetic algorithm in a real-world waterflood development. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 216, 110813 (2022).

Bahrami, P., Sahari Moghaddam, F. & James, L. A. A review of proxy modeling highlighting applications for reservoir engineering. Energies 15 (14), 5247 (2022).

Khosravi, R., Simjoo, M. & Chahardowli, M. An innovative approach to upscale Low-Salinity polymer flooding in heterogeneous sandstone reservoirs: application of particle swarm optimization and automated history matching. Results Eng. 104761. (2025).

Xu, L., Wang, X., Wang, Z. & Cao, G. Hybrid quantum genetic algorithm for structural damage identification. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 438, 117866 (2025).

Janiga, D., Czarnota, R., Stopa, J., Wojnarowski, P. & Kosowski, P. Performance of nature inspired optimization algorithms for polymer enhanced oil recovery process. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 154, 354–366 (2017).

Hou, J., Li, Z., Cao, X. & Song, X. Integrating genetic algorithm and support vector machine for polymer flooding production performance prediction. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 68 (1–2), 29–39 (2009).

Bahrami, P., Kazemi, P., Mahdavi, S. & Ghobadi, H. A novel approach for modeling and optimization of surfactant/polymer flooding based on genetic programming evolutionary algorithm. Fuel 179, 289–298 (2016).

Zhang, R. & Chen, H. Multi-objective global and local Surrogate-Assisted optimization on polymer flooding. Fuel 342, 127678 (2023).

Lei, Y., Li, S., Zhang, Q., Zhang, X. & Guo, L. In A hybrid genetic algorithm for optimal control solving of polymer flooding, 2010 International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation, IEEE: ; pp 122–125. (2010).

Al-Dousari, M. M. & Garrouch, A. A. An artificial neural network model for predicting the recovery performance of surfactant polymer floods. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 109, 51–62 (2013).

Jiang, B. et al. Modeling and optimization for curing of polymer flooding using an artificial neural network and a genetic algorithm. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 45 (5), 2217–2224 (2014).

Le Van, S. & Chon, B. H. Artificial neural network model for alkali-surfactant-polymer flooding in viscous oil reservoirs: generation and application. Energies 9 (12), 1081 (2016).

Amirian, E., Dejam, M. & Chen, Z. Performance forecasting for polymer flooding in heavy oil reservoirs. Fuel 216, 83–100 (2018).

Sun, Q. & Ertekin, T. In Development and application of an artificial-neural-network based expert system for screening and optimization of polymer flooding projects, SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, SPE: ; pp SPE-192236-MS. (2018).

Mohammadi, S., Khodapanah, E. & Tabatabaei-Nejad, S. A. Simulation study of salinity effect on polymer flooding in core scale. J. Chem. Petroleum Eng. 53 (2), 137–152 (2019).

Siavashi, M. & Yazdani, M. A comparative study of genetic and particle swarm optimization algorithms and their hybrid method in water flooding optimization. J. Energy Res. Technol. 140 (10), 102903 (2018).

Brantson, E. T. et al. Development of hybrid low salinity water polymer flooding numerical reservoir simulator and smart proxy model for chemical enhanced oil recovery (CEOR). J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 187, 106751 (2020).

Sun, Q. & Ertekin, T. Screening and optimization of polymer flooding projects using artificial-neural-network (ANN) based proxies. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 185, 106617 (2020).

Javadi, A. et al. A combination of artificial neural network and genetic algorithm to optimize gas injection: a case study for EOR applications. J. Mol. Liq. 339, 116654 (2021).

Ng, C. S. W., Jahanbani Ghahfarokhi, A. & Nait Amar, M. Application of nature-inspired algorithms and artificial neural network in waterflooding well control optimization. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 11 (7), 3103–3127 (2021).

Larestani, A., Mousavi, S. P., Hadavimoghaddam, F., Ostadhassan, M. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Predicting the surfactant-polymer flooding performance in chemical enhanced oil recovery: cascade neural network and gradient boosting decision tree. Alexandria Eng. J. 61 (10), 7715–7731 (2022).

Khosravi, R., Simjoo, M. & Chahardowli, M. A new insight into pilot-scale development of low-salinity polymer flood using an intelligent-based proxy model coupled with particle swarm optimization. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 29000 (2024).

Berg, A. B. Combining Gmsh and MRST-Developing Software for More Efficient Grid Creation in Two Dimensions (NTNU, 2022).

Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Larestani, A., Menad, N. A. & Hajirezaie, S. Applications of Artificial Intelligence Techniques in the Petroleum Industry (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2020).

Nakutnyy, P., Asghari, K. & Torn, A. In Analysis of waterflooding through application of neural networks, PETSOC Canadian International Petroleum Conference, PETSOC: ; pp PETSOC-2008-190. (2008).

Gupta, P. et al. In Genomic Insights into Infertility Using Neural Network, International Conference on Advances and Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Springer: ; pp 141–157. (2023).

Ebrahimi Mood, S., Rouhbakhsh, A. & Souri, A. Evolutionary recurrent neural network based on equilibrium optimization method for cloud-edge resource management in internet of things. Neural Comput. Appl. 37 (6), 4957–4969 (2025).

Elman, J. L. Finding structure in time. Cogn. Sci. 14 (2), 179–211 (1990).

Razghandi, M., Dehghan, A. & Yousefzadeh, R. Application of particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithm for optimization of a Southern Iranian oilfield. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. 11 (4), 1781–1796 (2021).

Abukhamsin, A. Y. Optimization of well design and location in a real field. Unpublished MS thesis, Stanford University, CA (2009).

Thomas, A. Essentials of polymer flooding technique. John Wiley & Sons: (2019).

Khosravi, R., Simjoo, M. & Chahardowli, M. Low salinity water flooding: estimating relative permeability and capillary pressure using coupling of particle swarm optimization and machine learning technique. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13213 (2024).

Funding

declaration.

This research was conducted without any external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Milad nourizadeh: Data curation, methodology, software visualization. Razieh Khosravi: Writing original draft, data curation, methodology. Mohammad Simjoo: Supervision, visualization, reviewing and editing. Mohammad Chahardowli: supervision, visualization, reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nourizadeh, M., Khosravi, R., Simjoo, M. et al. A hybrid AI-genetic algorithm framework for the optimization of polymer flooding strategies: a numerical simulation-based approach. Sci Rep 16, 3934 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33874-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33874-y