Abstract

Path-following control for wheeled mobile robots operating on varying terrains constitutes a fundamental challenge in robotic motion control, as terrain variations directly impact steering dynamics. This study models steering dynamics as a first-order system, where the dynamic parameter is matched to specific terrains. To achieve terrain adaptation, Support Vector Machine (SVM) methodology enables real-time matching of steering dynamics parameters to identified terrains through instantaneous image recognition. By integrating time-varying steering dynamics with fundamental kinematics, we establish the control model and subsequently design a path-following controller for this time-varying system using Lyapunov stability theory. Comparative experiments conducted in variable terrain environments evaluated fixed-parameter versus terrain-adaptive parameter control across linear, square, and circular paths. The results demonstrate that when the dynamic parameter can adapt to terrain variations, the designed time-varying parameter path following controller enables the mobile robot to converge to the predefined path more rapidly with reduced overshoot.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wheeled mobile robots (WMRs) are a type of robotic system capable of perceiving their environment and self-status through sensors, achieving goal-oriented autonomous motion in complex environments to accomplish specific operational functions1. Currently, wheeled mobile robots are increasingly being applied in fields such as smart agriculture, industrial automation, smart grids, intelligent delivery, smart homes, security, extreme environment exploration, and military domains2,3, providing technological support for high-quality development in related fields. For precise autonomous operation tasks in these military and civilian applications, a crucial prerequisite is that the robot must possess the capability to move from its current position to a target position along a predefined trajectory or path under constrained conditions. This relates to one of the core research issues in wheeled mobile robots – motion control. The motion control of wheeled mobile robots primarily takes two forms: path following and trajectory tracking4.

In path following, the desired motion of the mobile robot is described by geometric paths without constraints on its velocity. In trajectory tracking control, all states of the robot vary according to desired time functions, where the reference trajectory contains not only geometric path information but also corresponding reference velocities, meaning the robot’s speed cannot be arbitrarily set in trajectory tracking5. In practice, performance limitations in trajectory tracking can be eliminated through well-designed path following algorithms. Unlike trajectory tracking methods, path following control deals with implicit function equations of path curves or time-independent parameterized expressions. Being time-independent, path following can flexibly employ timing laws as additional control variables. This extra degree of freedom allows the robot to advance at constant or any other desired speed6.

The path following control of wheeled mobile robots primarily encompasses linear and nonlinear control methods. In linear control methods, the Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller, as a traditional model-free control approach, has been widely applied in path following control7. However, when the robot operates under different initial states, the control performance of fixed-parameter PID path following controllers cannot be guaranteed8. In such scenarios, PID controllers with parameter self-tuning capabilities, such as neural network PID controllers and fuzzy PID controllers9, have been implemented for mobile robot path following.Although these controllers demonstrate favorable tracking performance under varying initial conditions, their global stability remains challenging to ensure. Additionally, by constructing linear models related to desired heading errors and lateral position errors, the LQG technique has also been employed in path following control10. It should be noted that the difference between the heading angle and the desired path angle must remain relatively small; otherwise, the linearization conditions required for controller design would be violated, potentially leading to system instability.

Compared to linear control methods, nonlinear path following control approaches can more comprehensively account for system characteristics. Nonlinear control methods primarily include model predictive control, adaptive control techniques, intelligent control technologies, and Lyapunov stability theory-based approaches. Numerous scholars have conducted path following control research under specific constraints using MPC based on either kinematic or dynamic models of robots11,12,13,14,15, where controller stability is ensured through the construction of Lyapunov functions derived from cost functions. While most of these methods have been validated through simulations, implementing MPC-based path following control using complete robot models generates substantial computational loads. Particularly with larger prediction horizons, this imposes significant burdens on robot controllers, making real-time implementation challenging.

Model-based path following controllers can ensure stability of the designed controller when utilizing Lyapunov stability theory. Sliding mode control (SMC) method exhibits strong robustness, and its theoretical framework has been widely applied to path following control of wheeled mobile robots, achieving notable control performance16,17. However, the chattering phenomenon observed during sliding mode control may degrade control effectiveness. Path-stabilizing following controllers based on the Vector Field concept have also been implemented for wheeled mobile robots, enabling guidance along general smooth planar paths18,19,20. To address the path following control problem for wheeled mobile robots with unknown dynamic parameters, a novel time-varying adaptive controller was proposed21. This time-varying controller ensures stability via Lyapunov techniques, and simulation results validated its effectiveness. In22,23,24, the authors have used the Lyapunov-based control scheme designed the nonlinear time-invariant stabilizing continuous acceleration controllers, which will navigate the robot from an initial position to a target location in the presence of static obstacles. However, the parameters of these controllers are single, and their adaptability to multiple terrain environments in different states is insufficient. In summary, researchers around the world have employed diverse approaches to study path tracking control for wheeled mobile robots, obtaining notable results in both theoretical and experimental domains. Nevertheless, many of these methods are developed based on the kinematic models of wheeled mobile robots, often overlooking dynamic effects or their associated influences.

In25, the authors utilized experimental data with identification methods to acquire the robot’s dynamic model parameters. These parameters were subsequently employed in a simulation environment for training neural network parameters of a deep reinforcement learning-based path following control method, which was ultimately validated in a physical system. It should be noted that these dynamic model parameters were obtained exclusively from a single terrain type. In26, a terrain-dependent kinematic model based on the Instantaneous Centre of Rotation (ICR) concept was established and used to develop a nonlinear path following control law using the Lyapunov method. The path following control experiments were conducted on three different ground surfaces, namely grass, vinyl, and macadam, by obtaining ICR parameters offline and substituting them into the control law. Good results were achieved on these three ground surfaces. However, no corresponding studies were carried out on mixed-terrain scenarios.

In reality, as mobile robots operate in increasingly diverse environments, there emerges a critical need for stable motion control across multiple terrains. The dynamic responses of mobile robots vary significantly under different terrain conditions, and these variations directly affect their path following control performance. The path following control of wheeled mobile robots that can adapt to various terrains needs to be studied. In this study, the impact of terrain surfaces on robotic following control is defined as a dynamic response model, which is integrated with the fundamental kinematic model to establish a foundational framework for path-following control law design. The dynamic response model exhibits terrain-dependent characteristics, where terrain-specific response parameters vary across different terrain conditions. Building upon this modeling framework, nonlinear control laws are developed using Lyapunov-based techniques. To enhance adaptability across heterogeneous terrains, a vision recognition system is implemented at the robot’s front-end, enabling real-time terrain identification and feedback to the controller. This configuration constitutes a vision-based multi-terrain adaptive path following controller.

To the best of our knowledge, this work pioneers the integration of visual recognition with variable-terrain path-following control algorithms to achieve multi-surface adaptive path following, thereby enhancing path following performance. The contributions of this study are:

-

(1)

A novel hybrid modeling paradigm is proposed that systematically integrates terrain-induced dynamic response characteristics with conventional kinematic models, addressing the critical gap in conventional terrain-agnostic control models.

-

(2)

A Lyapunov-based nonlinear control law has been designed with rigorous stability proofs, effectively bridging theoretical kinematics and practical dynamic constraints in unstructured environments.

-

(3)

A vision-enabled scheme for cross-terrain adaptation was designed, establishing a closed-loop integration of perception and control. This allows real-time visual terrain recognition to dynamically configure the controller parameter, resulting in faster convergence to the predefined path and reduced overshoot during multi-surface path following compared to baseline methods.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section Problem description provides the problem description. Section Steering control law for the curved path following introduces the design of a Lyapunov-stable nonlinear controller for generating rotational velocity commands applicable to implicitly defined curved paths. The design incorporates steering dynamics via a formulated time-varying dynamic response parameter and utilizes the backstepping technique. In Section Varing terrain recognition based on support vector machine(SVM), the SVM based real-time terrain classifier is developed to identify the terrain where the robot is currently moving. Experimental validation on a real 4-wheel skid-steering mobile robot platform is presented in Section Experiments, alongside a comparative discussion of different steering control laws. Concluding remarks are given in Section Conclusion.

Problem description

A four-wheel skid-steering robot is a mobile platform that achieves steering through differential drive between left and right wheel sets and ground skid friction, without any active steering mechanism. To obtain the kinematic model required for the path-following controller design, we first illustrate the basic kinematics of the robot through Fig. 1. We establish a fixed global reference frame XOY and assign a body-fixed coordinate frame \({x}_{r}{o}_{r}{y}_{r}\) to the robot, with its origin coinciding with the robot’s center of mass (CoM). Furthermore, V and \(\omega\) denote the translational and rotational velocities, respectively, where R denotes the wheel radius, and 2f represents the lateral distance between the left and right wheels. Using (1), the wheel angular velocity commands can be derived from the desired translational and angular velocity inputs.

The mobile robot’s translational velocity V and rotational velocity \(\omega\) are commanded by a path-following controller, while its left and right driving wheels are independently regulated via PID-based speed controllers. This coupled kinematic behavior be characterized by the model formulated in (2).

The robot’s center of mass (CoM) position is given by coordinates (x, y), its orientation in the plane by \(\theta\), its angular velocity by V, and the distance from its instantaneous center of rotation (ICR) to the CoM by l. Given that l is sufficiently small, the term \(l\omega\) in Eq. (2) becomes negligible. The kinematics of a skid-steering robot can be approximately modeled by a simple “unicycle” vehicle model15. We therefore adopt the following approximate kinematic model.

The wheel angular velocities of the robot are regulated by tuned PID-based speed controllers, enabling steering control through differential actuation of the left and right wheels. During steering maneuvers, lateral slippage occurs due to frictional interaction between the wheels and the ground, resulting in transient dynamics of the steering behavior. To characterize the transient steering effects, this work approximates the dynamics with a first-order system:

where \({\omega }_{c}\) is the rotational speed command, and \({\alpha }_{\omega }>0\) is the steering dynamics response coefficient.

When the robot moves on the same type of pavement terrain, \({\alpha }_{\omega }\) remains constant; however, it becomes terrain-dependent and varies when operating on different pavement terrains. For a given terrain, \({\alpha }_{\omega }\) can be experimentally identified through system identification methods.

Therefore, the integrated control-oriented model combining steering dynamics and kinematic characteristics is formulated as:

Assumption 1

In this study, the desired path is assumed to be a smooth planar curve expressible as a twice continuously differentiable implicit function:

where f(x, y) serves as a signed distance function to the path, following the methodology in27.

Assumption 2

The first- and second-order partial derivatives of f(x, y), denoted as \(f_{x}\), \(f_{y}\), \(f_{xx}\), \(f_{xy}\), and \(f_{yy}\), are assumed bounded within any compact domain \(D\subset R^{2}\).

The gradient magnitude of f(x, y) is defined as:

We define \(D_{s}=\{(x,y)\mid x\in \mathbb {R}, y\in \mathbb {R}, \Vert \nabla f\Vert \ge \lambda \}\) as the robot’s safe movement region in this study, with \(\lambda\) being a positive constant. This implies that safe motion control can only be performed when the robot is located at points where the gradient magnitude is greater than or equal to \(\lambda\). In the following, the rotational speed command \({\omega }_{c}\) will be designed based on (5) to ensure that the robot converges asymptotically to the reference path shown as (6) in multi-terrain environments.

Steering control law for the curved path following

When a mobile robot operates in multi-terrain environments, consider a working scenario with n distinct terrain types. For the \({i}_{th}\) terrain type \(i\in \{1,2,...,n\}\), its corresponding steering dynamic response characteristic parameter is denoted as \({\alpha }_{\omega ,i}\). The complete set of steering dynamic response parameters is defined as \(A=\{{\alpha }_{\omega ,1},...,{\alpha }_{\omega ,n}\}\). Let \({\alpha }_{\omega ,j}\in A\) represent the steering dynamic response parameter associated with the terrain contacted by the robot before time instant \({t}_{j}\), where \(j\in {Z}^{+}\) remains finite given the robot’s finite operating duration. When terrain transition occurs at time \({t}_{j}\), a transition time window \(\Delta T\) is introduced to prevent abrupt parameter discontinuities that may perturb subsequent control systems. Specifically, after time \({t}_{j}+\Delta T\), the steering dynamic response parameter corresponding to the newly contacted terrain becomes \({\alpha }_{\omega ,j+1}\). During the transitional interval \(t\in ({t}_{j},{t}_{j}+\Delta T)\), the dynamic response parameter \({\alpha }_{\omega }(t)\) must satisfy continuous differentiability constraints. The designed time-varying dynamic response parameter is formulated as:

Analysis reveals that the parameter \({\alpha }_{\omega }(t)\) exhibits temporal continuity and maintains intrinsic monotonicity with smoothness over the interval \(({t}_{j},{t}_{j}+\Delta T)\). Notably, the temporal derivative of \({\alpha }_{\omega }(t)\) vanishes at both boundary instants, i.e.,

As shown in Fig. 2, the schematic diagram of \({\alpha }_{\omega }(t)\) illustrates these properties, confirming its compliance with the prescribed smooth transition requirements. This formulation aligns with the physical realizability of terrain transitions in robotic systems, providing a mathematically rigorous foundation for stability-guaranteed control synthesis. Therefore, the integrated control-oriented model combining steering dynamics and kinematic characteristics is formulated as:

Under the assumption that the velocity V and its derivative \(\dot{V}\) are bounded, satisfying \(V_{p2}\ge V \ge V_{p1}\), where \(V_{p1}\) and \(V_{p2}\) are positive constants. The desired direction along the reference path is represented by vector \((f_{x},f_{y})\) in Fig. 1. Accordingly, the desired heading angle \(\theta _{d}\) is defined as:

To further derive the robot’s steering control law, we introduce the virtual distance error \(e_{d}\) and the heading error \(e_{\theta }\), which are defined as follows:

By differentiating (12) and (13) with respect to time, we obtain:

To further analyze the system’s tracking control performance for steering angular velocity commands, an auxiliary control input \(\nu\) and the desired steering angular velocity rate \(\omega _{d}\) are introduced. The definition of \(\nu\) is given by (16) as follows:

Define the steering angular velocity error \(e_{\omega }\) as:

Based on the aforementioned mathematical operations, we derive the following error dynamic model for the control objective:

Define \(D_{1}=\{(e_{d},e_{\theta },e_{\omega })\mid |e_{d}|<e_{d1}, |e_{\theta }|<\pi , |e_{\omega }|<e_{\omega 1}\}\), where \(e_{d1}\) and \(e_{\omega 1}\) are fixed positive numbers. Let \({\textbf {x}}=(e_{d},e_{\theta },e_{\omega })\). We select the following Lyapunov function \(L({\textbf {x}})\):

Where \(k_{1}\) is a fixed positive number. \(f_{sat}(x)\) denotes a saturation function, defined as follows:

Where \(y_{0}\) is a given positive constant.

It holds that \(L({\textbf {0}})=0\). Within the region \(D_{1}-\{(0,0,0)\}\), the Lyapunov function \(L({\textbf {x}})\) is positive definite. Furthermore, the time derivative of \(L({\textbf {x}})\) is given by:

Introduce the desired control law \({\omega }_{d}\) as:

where \(k_{2}\) is a fixed positive constant. Substituting (22) into (21) yields:

By choosing \(\nu\) as follows:

And then, (18) can be rewritten as:

From the above derivation, it can be concluded that \((0,0,0)\) is the unique equilibrium point of the nonlinear system described by (25) within \(D_{1}\). Furthermore,

Thus, \(\dot{L}({\textbf {x}})\) is negative semidefinite. It can be found from (26) that \(L({\textbf {x}})\) is lower-bounded and \(e_{\omega }\) is bounded. Thus, the derivative of \(e_{\omega }\), i.e. \(\dot{e}_{\omega }\) is also bounded from the third equation of (25). Since V, \(\Vert \nabla f\Vert\), \(e_{\omega }\), \(\alpha _{\omega }(t)\), and their derivatives are all bounded, the derivative of \(\dot{L}({\textbf {x}})\) with respect to time t, i.e. \(\ddot{L}({\textbf {x}})\) is bounded. Consequently, \(\dot{L}({\textbf {x}})\) is uniformly continuous in time. Applying Barbalat’s lemma28, \(\dot{L}({\textbf {x}})\rightarrow 0\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\). Hence, \(e_{\theta }\rightarrow 0\), \(e_{\omega }\rightarrow 0\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\). Furthermore, (25) shows that \(sin(e_{\theta })\rightarrow 0\), and \(\dot{e}_{d}\rightarrow 0\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\). Since \(e_{d}\) is bounded, this implies \(e_{d}\) tends to a finite limit, specifically \(\overline{e}_{d}\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\). It can also be derived from \(\dot{e}_{\theta }\) in (25) that the derivative of \(\dot{e}_{\theta }\) with respect to time t, i.e. \(\ddot{e}_{\theta }\) is bounded. It follows that \(\dot{e}_{\theta }\) in (25) is uniformly continuous in time. Since \(e_{\theta }\rightarrow 0\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\), and \(\dot{e}_{\theta }\) in (25) is uniformly continuous, this guarantees that \(\dot{e}_{\theta }\rightarrow 0\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\). Since \(e_{\omega }\rightarrow 0\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\), \(V\ge V_{p1}\), and \(\Vert \nabla f\Vert \ge \lambda\), it then follows that \(\lim _{t\rightarrow \infty } f_{sat}(e_{d})=f_{sat}(\overline{e}_{d})\rightarrow 0\), and, by (20), \(\overline{e}_{d}=0\). Therefore, the auxiliary control input \(\nu\) shown in (24) and the desired steering angular velocity rate \(\omega _{d}\) shown in (22), together ensure the asymptotic convergence of \(e_{d}\), \(e_{\theta }\), and \(e_{\omega }\) to zero, and \(\omega \rightarrow \omega _{d}\) as \(t\rightarrow \infty\). Based on (4), the steering speed command \(\omega _{c}\) is calculated as follows:

Varing terrain recognition based on support vector machine(SVM)

Different terrain types correspond to distinct steering dynamics response parameters \(\alpha _{\omega }\). Consequently, the robotic system requires integrated capabilities for real-time terrain classification, dynamic parameter mapping, and adaptive control transmission, ultimately constructing a terrain-aware path-following controller with varying-terrain adaptation.

Common pavement terrain recognition methods include color space analysis, texture feature extraction, grayscale image edge detection, and artificial neural networks29. In addition to the effects of uneven illumination, pavement images may also be affected by factors such as high noise and tilted road angles during road recognition. To address these issues, this paper proposes a pavement recognition method based on HSV color features and texture features to overcome the limitations of single-algorithm approaches. By combining the advantages of both methods, this approach further enhances the real-time performance and accuracy of pavement recognition.

HSV color features

The accuracy of pavement recognition is closely related to the research on pavement recognition algorithms and the quality of pavement sample data collection. Simultaneously, factors such as lighting and weather conditions can also affect pavement recognition outcomes. Photographs of the same pavement captured from different angles may exhibit significant variations, while varying illumination conditions may lead to degradation in image quality. Therefore, before conducting analysis, preprocessing of pavement terrain images must be performed to enhance image quality30.

To minimize the negative impacts on road images, a series of steps must be performed during the image preprocessing stage to standardize the images. These steps include the establishment of a pavement image library, RGB feature extraction, HSV transformation, HSV feature extraction, and the calculation of the mean and variance of the image data. Through these processing steps, certain adverse effects of external factors are eliminated, resulting in more standardized pavement images.

HSV is a color space created by A.R. Smith in 1978 based on the intuitive characteristics of color, which divides color into three dimensions: Hue (H), Saturation (S), and Value (V). Hue represents the type of color; Saturation indicates the purity of color; Value denotes the brightness level. The HSV color space separates color from brightness, eliminating the correlation between chromaticity and luminance, thereby exhibiting robustness to illumination variations30. In OpenCV, the ranges for Hue, Saturation, and Value are 0-180, 0-255, and 0-255, respectively.

Color moments, a method for extracting image color features, were proposed by researchers Stricker and Orengo31. Leveraging the distribution characteristics of color spaces, color moments serve as an effective tool for color feature extraction. Color moments extract features by calculating the mean (first-order moment) and variance (second-order moment) across the three channels (H, S, V) of the HSV space.

Figure 3 demonstrate the first-order and second-order moments of three pavement terrains (wooden plank, rubber, and linoleum) in the HSV color model. It can be observed that under first-order moments, the H and S values of wooden and rubber surfaces exhibit minimal differences. In contrast, the second-order moments of all three surfaces demonstrate significant distinctiveness. Therefore, selecting second-order moment parameters in the HSV model as color features for subsequent pavement terrain recognition proves to be more appropriate.

Texture features

Texture features are used to distinguish microscopic structures and patterns of different objects or surfaces, typically extracted as numerical descriptors to represent textural information in images. Since textures are formed by the repetitive occurrence of gray-level distributions across spatial positions, there exists a specific gray-level relationship between pixel pairs separated by a given distance in the image space, known as the spatial correlation characteristics of gray levels. The gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) serves as a conventional method for texture description through analyzing these spatial correlation characteristics of gray values32.

The GLCM is a matrix function involving pixel distance and angular orientation, which quantifies the correlation between paired pixel grayscale values at specified distances and directions to characterize comprehensive image information regarding orientation, interval, variation magnitude, and transition patterns. Based on GLCM, Haralick proposed 14 statistical measures including mean, variance, entropy, difference variance, difference mean, difference entropy, angular second moment, contrast, maximum correlation coefficient, and information measures32.

In this study, four GLCM parameters—contrast (Con), energy (ASM), entropy (Ent), and Inverse Difference Matrix (IDM) —were selected as texture features initially. Contrast (Con) quantifies local variation intensity in images, reflecting both texture depth gradation and image sharpness, with higher values indicating more pronounced visual effects resulting from greater texture depth variations. Angular second moment (Asm) measures the uniformity of gray-level distribution and texture coarseness, where increased disparities between GLCM element values correspond to higher energy levels and coarser texture patterns. Entropy (Ent) evaluates the randomness of image information, demonstrating an inverse relationship between texture complexity and gray-level distribution simplicity: simplified distributions yield lower entropy values associated with homogeneous textures, while intricate distributions produce higher entropy values indicative of complex structural variations. Inverse Difference Matrix (IDM) is used to reflect the degree of local texture regularity and clarity in an image. When the image texture is irregular, unclear, and difficult to describe, the resulting value of IDM is small; conversely, it is larger.

Figure 4 demonstrates the comparative analysis of Con, Asm, Ent,and IDM parameters across wooden plank, linoleum, and rubber pavement terrains, revealing pronounced variations among the corresponding feature values. It can be observed that the comparative trends of the feature values ASM and IDM across the three different pavement terrains are similar. Therefore, only one of them needs to be selected. In this study, three GLCM parameters—contrast (Con), energy (ASM), and entropy (Ent) —are selected as components of the feature vector for image texture characterization.

Training SVM classifier

Based on the aforementioned analysis of image features, we extract three GLCM-derived features—Con, Asm, and Ent—and integrate them with HSV-derived second-order moments to construct a six-dimensional feature vector. This multimodal descriptor provides discriminative characterization of the three pavement terrain types (wooden plank, rubber, and linoleum).

The dataset comprises three pavement terrain types categories: wood planks, rubber, and linoleum, each containing 1,000 images. From each image, we extract the second-order moments of the HSV model and three texture features (Contrast, Energy, Entropy), forming a six-dimensional feature vector. These vectors are used to train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) model33. The flowchart of training the SVM classifier is shown as Fig. 5.

In this study, SVM in the Sklearn module is used to divide the data set into training set and testing set, where the ratio is 7:3. The RBF (Radial Basis Function) kernel function is selected as the feature kernel. A one-vs-one strategy is adopted to address the multi-class classification problem, establishing the SVM model34. The trained model is then evaluated experimentally. Table 1 summarizes the training results.

In Table 1, the index precision represents the ratio of samples correctly predicted as positive to all samples predicted as positive, with a higher value indicating greater reliability in the model’s positive predictions. The index recall represents the ratio of actual positive samples that were correctly identified, with a higher value indicating lower rates of false negatives and misses. To comprehensively evaluate these two metrics, the F1-score signifies that precision and recall are equally weighted. Support indicates the number of samples (instances) of the current class within the testing data. Accuracy represents the proportion of all samples that were classified correctly. Macro Avg (Macro Average) calculates the metric (Precision, Recall, or F1-score) independently for each class and then computes the unweighted arithmetic mean across all classes. Weighted Avg (Weighted Average), a refinement of the macro average, calculates the average weighted by the support (number of instances) for each class, thereby giving more influence to metrics from classes with larger sample sizes. These metrics collectively provide a detailed assessment of the SVM model’s performance on the test images.

Based on the training results, the model achieved a prediction accuracy of 0.9856, which satisfies the requirements for pavement recognition across diverse terrain environments. The trained model should be saved for subsequent applications.

Experiments

Experimental platform

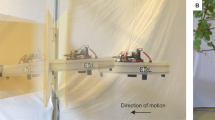

In this study, we constructed an experimental test bench incorporating three distinct types of terrain surfaces. The bench measures 4 meters in length, 4 meters in width, and 15 centimeters in height, and is designed to accommodate different materials including wooden planks, linoleum, and rubber. A photograph of the physical setup is provided in Fig. 6.

This bench is designed as a modular system, with each module measuring 1 meter in length, 1 meter in width, and 15 centimeters in height, constructed through the assembly of aluminum profiles. The surface materials adopt a modular configuration: each wooden board measures 1m\(\times\)1m, each linoleum sheet 1m\(\times\)1m, and each rubber mat 0.5m\(\times\)0.5m. Through flexible combination of these modular components, experimental platforms of various dimensions can be configured. This design enables the construction of diverse terrain surfaces for dynamic parameter measurements across different terrains, thereby significantly enhancing experimental efficiency and adaptability.

The experimental trials were conducted on a four-wheel skid-steering mobile robot (Fig. 7). The robotic platform incorporates dual control boards: a Raspberry Pi 4B-based system and an STM32F103RCT6-based controller. The Raspberry Pi 4B control unit acquires sensor data from a UWB positioning tag, LiDAR, monocular camera, and depth camera through USB serial interfaces. Motor actuation is achieved via a dedicated driver board, which integrates an MPU6050 inertial measurement unit (IMU). Inter-board communication between the two control systems is established through an I2C serial bus. Power management is implemented by a DCDC module embedded in the STM32-based controller, delivering a regulated 5V supply (maximum current 3A) to the Raspberry Pi subsystem. The comprehensive hardware architecture is illustrated in the block diagram of Fig. 8.

The control architecture employing Raspberry Pi 4B operates on an Ubuntu Raspbian platform with integrated Robot Operating System (ROS) Kinetic Kame framework. The control frequency is 100Hz. The key mechanical specifications and control parameter configurations of the robotic system are comprehensively tabulated in Table 2.

The control architecture is illustrated in Fig. 9. The developed curvature-adaptive path following controller generates angular velocity commands \(\omega _{c}\), which combine with prescribed longitudinal velocity inputs \(V_{c}\) to compute differential wheel speeds (\(\omega _{l}\) and \(\omega _{r}\)) through inverse kinematics derived from (1). These calculated speed references drive four independent PID control loops that output PWM-modulated voltage signals for precise regulation of the four-wheel DC traction motors.

To investigate the influence of terrain-adaptive steering dynamic parameter \(\alpha _{\omega }\) on path-following control performance, we designate the conventional approach with fixed \(\alpha _{\omega }\) as \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\), while the proposed terrain-adaptive method is termed \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\). Comparative experiments are conducted under identical velocity conditions for three distinct path geometries: linear segments, quadrilateral trajectories, and circular paths, employing both fixed and terrain-adaptive steering dynamic parameter configurations.

Prior to experiment commencement, \(\alpha _{\omega }\) values for different terrain will be identified through offline identification methods. This study employs the System Identification Toolbox in MATLAB and applies the Prediction Error Method to identify a first-order dynamic model. Figure 10 shows the identification of the transient dynamics for robot steering behavior on wooden planks The Pseudo-random signals are used as input excitation signals as shown in Fig. 10(a). Figure 10(b) compares the actual and predicted rotational speeds during the identification process.

Table 3 shows the identified \(\alpha _{\omega }\) values corresponding to three different terrains. Throughout the experimental process, the value of parameter \(\alpha _{\omega }\) in method \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) was maintained constant at 5.

Straight-line path following

During straight-path following experiments conducted under laboratory spatial constraints, the mobile robot’s commanded linear velocity \(V_{c}\) was fixed at 0.1 m/s, with initial position and heading angle configured as (0,0) and 0 degrees, respectively. Figure 11 compares the path following responses of the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) control strategies across four directional paths, while Fig. 12 demonstrates the corresponding distance error \(e_{d}\) evolution. The temporal profiles of \(\alpha _{\omega }\) for both methods are shown in Fig. 13. It should be noted that in these actual experiments, the transition time window \(\Delta T\) in (8) is set to the sampling period. Therefore, when the terrain changes, the the dynamic response parameter \({\alpha }_{\omega }(t)\) obtained using the proposed method change from one value to another in discrete steps. The time interval between these changes is \(\Delta T\). As a result, the time-varying dynamic response parameter in Fig. 13 appeares to depict instantaneous step-changes instantaneous step-changes during this phase.

Performance evaluation was performed using three dynamic response metrics:

-

(1)

Rise time: Duration until \(|e_{d}|\) first enters the 0.025 m tolerance band;

-

(2)

Settling time: Total duration for \(|e_{d}|\) to persistently remain below 0.025 m;

-

(3)

Overshoot: Peak lateral deviation from the reference path.

Table 4 summarizes the performance for straight-path following in four directions (0\(^\circ\), 45\(^\circ\), 90\(^\circ\), and 135\(^\circ\)) using the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) methods. Except for the 135° direction, the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) method demonstrates shorter rise times than \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\); however, it exhibits longer settling times. Additionally, the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method achieves significantly smaller overshoot values, notably below 0.04m for the 0°, 45°, and 90° directions, as illustrated in Fig. 12. These results indicate that the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method enables faster convergence of the robot toward the desired path while maintaining superior stability.

Square path following

The linear velocity command \(V_{c}\) for the mobile robot in square path-following is set to 0.1 m/s. A path switching mechanism that triggers 0.08 meters in advance of reaching each path segment is adopted. This experimental phase utilizes a square path defined by four vertices as shown in Fig. 14: A(0,0), B(2.7,0), C(2.7,2.7), and D(0,2.7). The robot’s initial position and heading are set to (0,0) and \(0^{o}\), respectively. Figure 14 further illustrates the comparative actual trajectories of path-following using both the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) methods. While executing the square path following, the predefined behavior that the robot will switch segment in advance with 0.08m was adopted. Accordingly, the robot exhibited the response characteristics of straight-line path following.

Figs. 15 and 16 present the distance error comparison and the temporal variations of \(\alpha _{\omega }\) between these two methods during square path following respectively. Table 5 summarizes the performance metrics of square path-following using the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) methods. The results demonstrate that the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method achieves overshoot values of 0.185 m, 0.20 m, and 0.16 m in Regions I, II, and III (as marked in Fig. 15), respectively. In contrast, the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) method yields consistent overshoots of 0.28 m across all three regions. This indicates that the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method significantly reduces overshoot compared to the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) approach, thereby validating the effectiveness of the adaptive parameter strategy.

During the transition from one straight segment to another, the robot requires a certain period to adjust its trajectory for aligning with the subsequent segment. As shown in Fig. 15, when the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method is employed, the distance error \(e_{d}\) converges to zero. However, under \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) approach, constrained by the limited experimental site (with each side of the square path measuring only 2.7 meters), the convergence of \(e_{d}\) is relatively slow. Consequently, the robot proceeds to the next segment before \(e_{d}\) fully converges to zero.

Figs. 17 and 18 depict the steering speed command response characteristics of the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) methods during square path following, respectively. The comparative analysis conclusively demonstrates that the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method enables the robot to achieve better square path-following performance.

Circular path following

In circular path-following experiments, the mobile robot was configured with a linear velocity command \(V_{c}=0.3m/s\) and an initial position at (0, 0). The reference trajectory comprised two concentric circles centered at \((1,-1)\), mathematically defined as \(\sqrt{(x-1)^2+(y+1)^2}=R_{c}\) with radii \(R_{c}=1\) (Circle A) and \(R_{c}=1.1\) (Circle B). The robot initially followed Circle A and autonomously transitioned to Circle B at \(t=30s\) post-initiation, demonstrating adaptive path-switching capabilities.

Figure 19 confirms that the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method achieves significantly smaller overshoot than \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) during circular path convergence. When applying \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) to circular-path following, Fig 20 reveals minimal overshoot in distance error \(e_{d}\) (as indicated by ellipse-marked regions I and II in Fig. 20). This result indicates that the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method promotes smoother convergence to the circular reference path.

As indicated in Table 6, the overshoot of the distance error \(e_{d}\) during the first circular path-following task is 0.0056m and 0.055m for the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) methods, respectively. When the robot transitions to the larger-radius circular path, the overshoot values of \(e_{d}\) for the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) methods are 0.095 m and 0.093 m, respectively.

Table 6 lists the convergence times for the robot tracking Circles A and B. When using the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) method, the robot achieves convergence to Circle A in only 3.6 seconds, whereas the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) method requires over 6 seconds. During the second tracking task (Circle B), the convergence times for the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) methods are 3.04 seconds and 2.96 seconds, respectively.

Figures 22 and 23 depict the steering speed command response characteristics of the \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) and \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) methods during circular path following respectively.

As evidently demonstrated, the control strategy enables faster convergence to the reference path through real-time gain adaptation, thereby significantly enhancing path-tracking efficiency. Comparative analysis confirms that, relative to the fixed-gain \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -fixed}}\) method, the method \(PFC_{{\alpha }_{\omega -adaptive}}\) maintains superior circular path-following performance, particularly in terms of settling time reduction and steady-state error suppression.

Conclusion

This study addresses the path-following control problem for wheeled mobile robots operating on varying terrains by designing a time-varying path-following controller. Unlike traditional controllers based primarily on simplified kinematic models, this research incorporates steering dynamics, treating its characteristic parameters as terrain-dependent variables. A parameter variation function for steering dynamics is introduced to account for terrain transitions. On this basis, a fundamental model for controller design is established by integrating steering dynamics with the kinematic model.

Subsequently, leveraging this time-varying model and Lyapunov stability theory, a time-varying path-following controller is designed. The derived steering velocity commands enable stable tracking of predefined smooth paths on planar surfaces.

To identify terrain changes in real time, a Support Vector Machine (SVM) method is used to train a classifier offline. This trained classifier performs real-time identification of the robot’s current terrain, matches the corresponding dynamic response parameters, and dynamically adjusts steering control commands. Path-following experiments involving linear, square, and circular paths were conducted on a variable-terrain test platform. Results demonstrate the superior performance of the controller with time-varying dynamic response parameters compared to controllers using fixed parameters.

It should be noted that the current experiments were conducted on horizontal ground surfaces. Future work will investigate path-following algorithms in three-dimensional or rough terrain environments35. Moreover, when robots perform operational tasks36 or experience changes in physical parameters, the impact on following control must be considered. Future research will focus on real-time estimation of dynamic disturbances and their compensation within the controller with prescribed performance37 to further expand the scope of path-following control.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kong, L., Chen, X. & Liu, X. Adasharing: adaptive data sharing in collaborative robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64(12), 9569–9579 (2017).

Mojtaba, S. S. & Hossein, M. Development of a mobile robot for safe mechanical evacuation of hazardous bulk materials in industrial confined spaces. J. Field Robot. 39(3), 218–231 (2022).

Zuo, Z., Song, J. & Han, Q. L. Coordinated planar path-following control for multiple nonholonomic wheeled mobile robots. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 52(9), 9404–9413 (2022).

Rameez, K., Mumtaz, M. F., Abid, R. & Naveed M. Comprehensive study of skid-steer wheeled mobile robots: development and challenges. Ind. Robot 48(1), 142–156 (2021).

Yao, W., Lin, B., Anderson, B. D. O. & Cao, M. Guiding vector fields for following occluded paths. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 67(8), 4091–4106 (2022).

Aguiar, A. P., Hespanha, J. P. & Kokotovic, P. V. Path-following for nonminimum phase systems removes performance limitations. IEEE Trans. Autom Control 50(2), 234–239 (2005).

Xiong, R., Li, L., Zhang, C., Ma, K., Yi, X. & Zeng H. Path tracking of a four-wheel independently driven skid steer robotic vehicle through a cascaded ntsm-pid control method. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–11 (2022).

Kayacan, E., Young, S. N., Peschel, J. M. & Chowdhary, G. High precision control of tracked field robots in the presence of unknown traction coefficients. J. Field Robot. 35(7), 1050–1062 (2018).

Han, G., Fu, W., Wang, W. & Wu, Z. The lateral tracking control for the intelligent vehicle based on adaptive pid neural network. Sensors 17(6), 1244 (2017).

Fernandez, B., Herrera, P. J. & Cerrada, J. A. A simplified optimal path following controller for an agricultural skid-steering robot. IEEE Access 7, 95932–95940 (2019).

Yu, S., Guo, Y., Meng, L., Qu T. & Chen H. Mpc for path following problems of wheeled mobile robots. IFAC PapersOnLine 51(20), 247–252 (2018).

Prado, A. J., Torres-Torriti, M. & Cheein, F. A. Distributed tube-based nonlinear mpc for motion control of skid-steer robots with terra-mechanical constraints. IEEE Robot. Autom. Let. 6(4), 8045–8052 (2021).

Sun, Z., Dai, L., Xia, Y. & Liu, K. Event-based model predictive tracking control of nonholonomic systems with coupled input constraint and bounded disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 63(2), 608–615 (2018).

Prado, A. J., Torres-Torriti, M., Yuz, J. & Cheein, F. A. Tube-based nonlinear model predictive control for autonomous skid-steer mobile robots with tire-terrain interactions. Control Eng. Pract. 101, 104451 (2020).

Wang, J., Fader, M. T. H. & Marshall, J. Learning-based model predictive control for improved mobile robot path following using gaussian processes and feedback linearization. J. Field Robot. 40(5), 1014–1033 (2023).

Akermi, K., Chouraqui, S. & Boudaa, B. Novel smc control design for path following of autonomous vehicles with uncertainties and mismatched disturbances. Int. J. Dynam. Control 8(1), 254–268 (2018).

Xie, Y., Zhang, X. & Meng, W. Coupled fractional-order sliding mode control and obstacle avoidance of a four-wheeled steerable mobile robot. ISA Trans. 108, 282–294 (2021).

Chen, J., Wu, C., Yu, G., Narang, D. & Wang Y. Path following of wheeled mobile robots using online-optimization-based guidance vector field. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mech. 26(4), 1737–1744 (2021).

Kapitanyuk, Y.A., Proskurnikov, A.V. & Ming, C.: A guiding vector field algorithm for path-following control of nonholonomic mobile robots. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 26(4), 1372–1385 (2018).

Sobański, R. M., Michałek, M. M. & Defoort, M. Predefined-time VFO control design for unicycle-like mobile robots. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 3591–3603 (2024).

Miao, Z. & Wang, Y. Adaptive control for simultaneous stabilization and tracking of unicycle mobile robots. Asian J. Control 17(6), 2277–2288 (2015).

Kumar, S. A., Chand, R. P., Chand, R. & Sharma, B. Entertainment and assistive robot: acceleration controllers of an autonomous kids personal transporter (kPT). Eng. Sci. 32, 1–13 (2024).

Chand, R. P., Chand, R., Naicker, P. R. & Narayan, S.V. Tomorrow’s smart city personal transporter: an autonomous hoverboard robot. 2022 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Computer Science and Data Engineering (CSDE), Gold Coast, Australia, 2022, 1–6 (2022).

Chand, R. P., Chand, R., Assaf, M., Narayan, S.V., Naicker, P. R. & Kapadia, V. Acceleration feedback controller processor design of a segway. 2022 IEEE 7th Southern Power Electronics Conference (SPEC), Nadi, Fiji,2022, 1–6 (2022).

Caponio, C., Stano, P., Carli, R., Olivieri, I., Ragoneet, D. & Sorniotti, A. Modeling, positioning, and deep reinforcement learning path following control of scaled robotic vehicles: design and experimental validation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 22, 9856–9871 (2025).

Huskic, G., Buck, S. & Zell, A. Path following control of skid-steered wheeled mobile robots at higher speeds on different terrain types. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 2017, 9856–9871 (2017).

Morro, A., Sgorbissa, A. & Renato, Z. Path following for unicycle robots with an arbitrary path curvature. IEEE Trans. Robot. 27(5), 1016–1023 (2011).

Khalil, H. K. Nonlinear Systems (Nonlinear Systems, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2015).

Shi, R., Yang, S., Chen, Y., Wang, R., Zhang, M., Lu, J. & Cao Y. Cnn-transformer for visual-tactile fusion applied in road recognition of autonomous vehicles. Pattern Recog. Lett. 166, 200–208 (2023).

Lee, D. & Plataniotis, K. N. A taxonomy of color constancy and invariance algorithm. In: Advances in Low-Level Color Image Processing. (eds. Celebi, M., Smolka, B.) Lecture Notes in Computational Vision and Biomechanics 11, 55–94 (2013).

Stricker, M. A. & Orengo, M. Similarity of color images. Proc. SPIE 2420, Storage and Retrieval for Image and Video Databases III, 381–392 (1995)

Benco, M., Hudec, R. & Kamencay, P. An advanced approach to extraction of colour texture features based on glcm. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2014, 1–8 (2014).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20(5), 273–297 (1995).

Zhao, J., Wu, H. & Chen, L. Road surface state recognition based on svm optimization and image segmentation processing. J. Adv. Transport. 2017, 1–21 (2017).

Li, L., Qiang, J. & Xia, Y. Adaptive dual closed-loop trajectory tracking control for a wheeled mobile robot on rough ground. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 2411–2425 (2025).

Chand, R., Kumar, S. A., Sharma, B. & Chand, R. P. Multitasking capabilities of an autonomous quad-arm mobile manipulator (qAMM) for smart city operations. Unmanned Syst. 14, 1–23 (2026).

Ge, M., Xu, Hz. & Song, Q. Prescribed-time control of four-wheel independently driven skid-steering mobile robots with prescribed performance. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 20991–21005 (2023).

Funding

This work was partially supported by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (2024J01850, 2020J05197).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. has contributed to this paper by carrying out the methodology and formulation, the supporting algorithms, and original draft preparation. W.Z. has also contributed to this paper by carrying out the methodology and formulation. X.L. and N.L. have contributed to this research by performing the experiments. S.D. was also involved in the aspect of the revision of the manuscript and in the literature review. His expertise in support vector machine in object classification and recognition has contributed towards the vision-based adaptive path following controller. Y.C., W.Z., X.L., N.L., and S.D. discussed the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Zeng, W., Liu, X. et al. Vision-based adaptive path following controller for 4W mobile robots on varied terrains. Sci Rep 16, 3782 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33893-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33893-9