Abstract

To meet stricter environmental regulations, the SuperClaus process has been proposed to enhance sulfur recovery in Claus sulfur recovery units (SRUs). SuperClaus modifies the traditional Claus process by adding a catalytic bed for direct hydrogen sulfide oxidation after the Claus beds. This study begins with a steady-state simulation of the Claus process using AspenPlus, with results closely matching industrial data—showing relative errors of 5.56% for SO₂, 8.10% for H₂S, and 0.84% for sulfur recovery. The SuperClaus process is then designed, optimized, and simulated under steady-state conditions. Unit operations, such as the reaction furnace, heat recovery boiler, and catalytic reactors, were modeled as plug-flow reactors (PFRs). Simulation results show sulfur recovery increases from 95.9% to 98.5% using SuperClaus process. In addition to considering the detailed reaction kinetics and design of an optimized SuperClaus reactor, the main novelty of this work is the dynamic simulation of the SuperClaus unit performed using AspenPlus Dynamics. The control system is tested under step changes in feed temperature (±20%), pressure (±10%), and concentration (±5%). Results indicate that concentration changes have the most significant impact on overshoot in the control loop. Despite disturbances, the control system effectively maintains desired setpoints, demonstrating the robust performance of the SuperClaus configuration under varying operating conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In processes like natural gas sweetening, hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) is separated from hydrocarbons, forming an acid gas stream containing H₂S, CO₂, water vapor, hydrocarbons, and trace compounds1. Due to environmental concerns, acid gas cannot be released directly and must undergo treatment. Sulfur Recovery Units (SRUs) convert H₂S to elemental sulfur, which is used in industries such as rubber, pharmaceuticals, sulfuric acid, and pesticides2.

The history of SRUs dates back to 1883 when Carl Friedrich Claus developed a process to convert H₂S to sulfur via a partial oxidation reaction: H2S + 1/2 O2 → 1/8 S8 + H2O.

In 1938, the process was improved by partially burning H₂S with air to form SO₂, which reacted with unburned H₂S in a catalytic reactor3. The modified Claus process consists of thermal and catalytic sections. In the thermal section, one-third of H₂S combusts to form SO₂, which reacts with the remaining H₂S to form sulfur. Equations (1) and (2) presents these reactions.

The resulting gas passes through a heat recovery boiler and condensers, where sulfur is removed. The catalytic section promotes further H₂S and SO₂ conversion via the Claus reaction (Eqs. 1–3).

Each catalytic stage includes a reactor and condenser. Sulfur vapor is condensed, and with each stage, H₂S and SO₂ levels drop, allowing lower reactor inlet temperatures. Water vapor increases in the stream over time, raising corrosion risks and shifting equilibrium away from sulfur production. Thus, recovery gains from additional reactors diminish. Two-reactor Claus units recover 90–96% sulfur; three-reactor systems recover 95–98%.

Stricter environmental regulations have prompted the development of improved methods, such as the SuperClaus process. A key distinguishing feature of this process is the SuperClaus catalyst used in the final reactor, which directly oxidizes hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) to sulfur (as shown in Eqs. 1–5), bypassing any equilibrium limitations. The SuperClaus process can achieve sulfur recovery rates of up to 99%3.

Dynamic simulation of the SuperClaus process is crucial for process design and optimization because feed conditions—such as temperature, pressure, and composition—vary due to multiple upstream gaseous effluent streams.

Sulfur recovery units (SRUs), particularly the Claus process, have been extensively studied. In the following, the research on both the Claus and SuperClaus methods has been reviewed, focusing on three areas: (I) empirical and equilibrium modeling, (II) reaction kinetics and rate equations, and (III) process simulation.

-

(I)

Empirical and equilibrium modeling.

Bennett and Meisen studied equilibrium models for the reaction furnace4. They developed the model using experimental equilibrium data at atmospheric pressure and a temperature range of 600–2000 K. By changing oxygen-to-hydrogen sulfide ratios in the feed between 0.05 and 1, they concluded that if the oxygen-to-hydrogen sulfide ratio is less than stoichiometric and the furnace temperature is maintained, sulfur recovery can increase by 10%. Fischer published volume percentage charts for the main compounds exiting the reaction furnace in 1974 but did not provide data on the method’s accuracy5. Maneri et al. extensively reviewed the research works on the Claus reaction furnace models6. The models were based on equilibrium and empirical formulation, and were able to predict the outlet stream composition of the heat recovery section especially hydrogen, carbon monoxide, carbonyl sulfide, and carbon disulfide concentrations.

-

(II)

Reaction kinetics and rate equations.

In 1976, Steijns et al. proposed a mechanism for the direct oxidation of hydrogen sulfide, consistent with most of the available kinetic data7. They considered four different catalysts: molecular sieves 13X, gamma-alumina, molecular sieve carbon, and active carbon. They also developed a reaction rate equation for the direct oxidation of hydrogen sulfide. However, they did not consider possible side reactions alongside the primary selective oxidation of hydrogen sulfide.

In 1993, Tong et al. suggested a kinetic model for the hydrolysis reaction of carbonyl sulfide8. In another study, they used four mechanisms to study the kinetics of carbon disulfide hydrolysis on alumina and Titania catalysts9. In 1997, they employed their developed rate equations for Claus catalytic reactions to simulate Claus catalytic reactors10.

Karan conducted research for his doctoral thesis, focusing on the partial oxidation of hydrogen sulfide and the potential side reactions that could occur in the Claus process and heat recovery furnace11. He utilized experimental data to develop reaction rate equations to produce carbonyl sulfide and carbon monoxide, as well as a thermal decomposition rate equation for hydrogen sulfide. Karan also investigated the production of carbonyl sulfide within the heat recovery furnace. He concluded that by adjusting operational variables and unit design, the amount of carbonyl sulfide produced in the heat recovery furnace could be reduced by over 50%. Additionally, Karan et al. studied the formation reaction of carbonyl sulfide (COS) at high temperatures, proposing a rate equation for its reversible production from carbon monoxide and sulfur12. In 1999, Kara et al. investigated the thermal decomposition of hydrogen sulfide, the reaction that produces carbon monoxide from hydrogen and carbon dioxide, and the reaction that generates carbonyl sulfide from carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide13. In a separate study, Karan and Behie conducted a kinetic analysis of carbon disulfide (CS2) formation from reactions involving methane (CH4) with hydrogen sulfide and methane with sulfur14.

Hawboldt conducted kinetic modeling of crucial reactions in the Claus process furnace15. The reactions he studied included the reversible thermal decomposition of hydrogen sulfide, thermal decomposition, and the oxidation of ammonia, as well as two main Claus reactions. He derived rate equations for these reactions using the kinetic data from a pilot-scale pipe reactor. The pilot conditions were similar to the operating conditions of the industrial Claus units. He also conducted experiments to determine the competition for oxygen consumption between hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and ethane. In 2000, Hawboldt et al. developed a rate equation for the thermal decomposition of hydrogen sulfide16. Monnery et al. presented a rate equation for the thermal Claus reaction17.

In 2018, Shinkarev et al. proposed a kinetic model for the selective oxidation of hydrogen sulfide on carbon nanofiber catalysts18. Their research included catalyst synthesis and kinetic studies. In addition to the direct oxidation of hydrogen sulfide to elemental sulfur, they also considered possible side reactions in the direct oxidation reactor and provided rate equations for those reactions.

-

(III)

Rigorous modeling of Claus process.

In 2016, Zarei et al. focused on modeling the heat recovery section of the Claus process19. They minimized Gibbs’s free energy and added parameters to thermodynamic property relationships to model the reaction furnace. These new parameters reduced the prediction error of the outlet flow rate from 33.5% to 7.86%. They modeled the kinetics of the heat recovery boiler. The combined reaction furnace and heat recovery boiler modeling aligned well with experimental data. They optimized the parameters of the heat recovery boiler and the reaction furnace to maximize sulfur recovery and minimize carbonyl sulfide emissions.

In 2017, Kazempour et al. conducted kinetic modeling of the thermal section of an industrial Claus unit and compared the results with industrial data20. Their optimization focused on maximizing sulfur recovery and steam production while meeting the hydrogen sulfide to sulfur dioxide ratio limit. In 2018, Kardan and Eslamloueyan utilized kinetic, equilibrium, and kinetic-equilibrium models to simulate a furnace and heat recovery boiler in an industrial sulfur recovery unit21. Their comparison of the modeling results with industrial data revealed that the kinetic model provided the most accurate simulation of the unit. They also examined the impact of heat loss from the furnace on the outlet stream conditions, discovering that preheating the acid gas feed reduces sulfur recovery efficiency. Conversely, their simulation results indicated that lowering the acid gas temperature could optimize the ratio of hydrogen sulfide to sulfur dioxide.

In 2020, Mehmood et al. conducted kinetic modeling of a reaction furnace, considering 11 reactions and three different acid gas concentrations22. They found their model reliable and suggested it could be used for computational fluid dynamics studies, optimization, and control of sulfur recovery units, comparing it to others’ published work. Abedini et al. modeled and simulated the catalytic beds of an industrial Claus unit23. They split the 2-meter catalytic bed into 100 parts and solved mass and energy balance equations for each part.

Asadi et al. examined the Claus process using T-SWEET (PROSIM) software24. They investigated the effects of acid gas feed conditions, such as hydrogen sulfide concentration, the hydrogen sulfide to carbon dioxide ratio, and the airflow rate, on the temperature of the reaction furnace and the sulfur recovery. With the improvement of the above parameters, the sulfur recovery increased from 96.67% to 98.67%. There were no validations with industrial data in their work. Manenti et al. used a kinetic model with 2400 reactions and 140 compounds to model the Claus unit’s thermal and catalytic Sect25. They considered the furnace’s combustion chamber a stirred reactor, the reaction section as tubular reactors, and the Claus catalytic beds as tubular plug-flow reactors. They optimized for maximum sulfur recovery and steam production.

In 2015, Nabikandi and Fatemi conducted a study on the kinetic and equilibrium modeling of a sulfur recovery unit, achieving a recovery rate of 97.4 mol%. They determined that the kinetic model is more accurate, effectively predicting concentration, temperature, and pressure throughout the furnace and reactors. In contrast, the equilibrium model is limited to predicting conditions only at the outlets of the furnace and reactors26. In 2016, Nabjan et al. simulated the Claus process using the Aspen HYSYS simulator27. They examined how changes in operating variables affect sulfur recovery and utilized conversion and R-Gibbs reactors without employing reaction rate equations. The results indicated that sulfur recovery increases as the nitrogen to oxygen (N2 to O2) ratio in the air stream rises. Additionally, the study found that when the air flow rate reaches 140.6 kgmol/hr, sulfur recovery can attain 100%. However, the simulation results were not compared or validated with industrial data, and the initial sulfur recovery rate before the sensitivity analysis was unknown. Ghahraloud et al. used energy and mass balance equations to model an industrial sulfur recovery unit and employed a genetic algorithm to optimize the process2. Furthermore, they found that replacing adiabatic catalytic reactors with autothermal reactors can increase sulfur recovery by 5.18%. Al Hamadi et al. used Chemkin Pro and Aspen HYSYS to simulate the reaction furnace and heat recovery boiler and validated their results using literature data28. They also explored the impact of oxygen concentration on sulfur recovery. In three different conditions with different hydrogen sulfide concentrations, they used a precise reaction mechanism to investigate the effect of oxygen concentration (between 20 and 100%) of the inlet air flow on sulfur recovery, BTEX compound destruction, toxic gas release rate, gas fuel consumption, etc. They presented the simulation results in the form of graphs. They interpreted the graphs and stated that oxygen concentrations above 30% can have an adverse effect on sulfur recovery rate. With increasing oxygen concentration, the CO2 concentration output from the BTEX incinerator and the gas fuel consumption rate in the incinerator decreased, but the SO2 concentration increased. Also, the carbon monoxide concentration increases with increasing oxygen concentration until the furnace temperature is less than 1350, and then with further increasing oxygen concentration and increasing furnace temperature, the carbon monoxide concentration also decreases. They recommended an oxygen concentration above 50% for UAE sulfur recovery units, given their feed concentration, to maximize aromatics breakdown and minimize carbon monoxide production. In 2019, Ibrahim et al. proposed improvements to Claus sulfur recovery units using Chemkin Pro software29. The modifications included two reaction furnaces, heat recovery boilers, and separate intermediate condensers for water and sulfur products. The study found increased sulfur recovery efficiency from 63% to 75%. Hashemi et al. conducted a study using PROSIM software to simulate an industrial Claus sulfur recovery unit with an acid gas bypass from the reaction furnace in 202030. They validated the simulation results with plant data and examined the impact of operational parameters on sulfur recovery. Rao and Haydary simulated the SuperClaus process using the Sulsim tool within Aspen HYSYS software in 201931. Initially, they achieved a sulfur recovery of 93.89%. By incorporating Air Demand Analysis and adjusting the H₂S to SO₂ ratio in the tail gas stream to 2, they improved the recovery rate to 98.6%. They then simulated a feed stream with a higher H₂S percentage. To meet the desired recovery rate in this scenario, they employed the bypass flow method, which did not significantly enhance sulfur recovery. In the subsequent steps, they added a selective oxidation reactor, resulting in a recovery rate of 99.14%. Furthermore, by incorporating a tail gas section with a recycle stream and replacing the alumina catalyst with a titania catalyst, the performance improved to 99.92%.

Despite the SuperClaus process’s high efficiency in achieving the targeted recovery percentage, we could not find any articles specifically dedicated to the simulation of this process. Moreover, despite the critical importance of dynamic simulation in analyzing and predicting system behavior and control system performance—especially when acid gas conditions deviate from steady state, a situation likely to occur in sulfur recovery units—we did not find any dynamic studies on the Claus or SuperClaus processes in the available literature. Our research aims to fill that gap by presenting a comprehensive model of the SuperClaus process. Along with an in-depth analysis of the reaction kinetics and the design of an optimized SuperClaus reactor, this work’s main novelty lies in the dynamic simulation of the SuperClaus unit conducted using AspenPlus Dynamics. We will thoroughly analyze how this process behaves under steady and unsteady-state conditions. By developing this model, we will gain valuable insights that will enhance our understanding of the SuperClaus process performance and its capabilities compared to conventional SRU units.

Materials and methods

This section outlines the modeling and simulation of the SuperClaus process using AspenONE software. We utilize industrial data from a Claus unit to perform and verify a steady-state simulation of the Claus process. We then present the steady-state simulation of the SuperClaus process in Aspen Plus and discuss its dynamic simulation procedure.

Steady-state simulation of an industrial Claus process

Process description

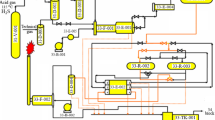

Figure 1 shows a simplified schematic of the Claus unit under study. Acid gas containing 31.66% hydrogen sulfide is preheated to 220 °C and split into a furnace feed (414.3 kmol/hr) and a bypass stream (10.58 kmol/hr). Both air and feed streams are preheated before entering the reaction furnace, which has combustion and non-combustion zones. The hot gas exits the furnace at 954 °C, cools to 307 °C in the heat recovery boiler, and undergoes further non-combustion reactions. It is then cooled to 180 °C in the first condenser, separating liquid sulfur. The remaining gas mixes with the bypass stream and enters the first catalytic reactor at 235 °C, where Claus and carbon disulfide hydrolysis reactions occur. After cooling to 181 °C in the second condenser, sulfur is separated, and the vapor is reheated to 215 °C before the second catalytic reactor. The gas is cooled again in the third condenser, reheated to 200 °C, and passes through the third catalytic reactor. Finally, it is cooled to 129 °C in the fourth condenser. The resulting tail gas, containing residual sulfur compounds, is incinerated before atmospheric release.

Pseudo-component definition and thermodynamic model

In the thermal and catalytic Claus reactions and the super-Claus reactor, sulfur forms as S₂, S₆, and S₈ allotropes. Although selectable in Aspen Plus, missing property data prevents successful simulation. Therefore, these allotropes were defined as pseudo-components based on their normal boiling point (444 °C), density (1810 g/mol), and molecular weight32. The Peng-Robinson equation of state, previously used successfully for Claus process modeling30, was applied in the simulation.

Simulation of the reaction furnace and waste heat boiler

Table 1 presents the Claus unit’s acid gas feed properties. Preheated air (378.2 kmol/hr) and methane-rich fuel (3.3 kmol/hr) enter the adiabatic tubular reaction furnace (1.2 m diameter, 0.9 m length). Table 10 lists the combustion reactions and rate equations used for modeling. Due to missing combustion data for benzene, toluene, and mercaptans, their reactions were simulated using a stoichiometric reactor model.

The oxygen-free second section of the furnace is where non-combustion reactions occur. We modeled this section as a 3.2-meter-diameter and 3.5-meter-long adiabatic tubular reactor, considering reactions 5 through 10.

Table 11 represents the rate equations for these reactions. The waste heat boiler (WHB) consists of a 5.5-meter-long shell containing 300 tubes, each 64 mm in diameter. Furnace effluent passes through the tubes, cooling via heat transfer with boiling water. Boiler feed water enters the shell side at 110 °C, and steam exits at 165 °C. As reactions 5 to 10 occur within the tubes, the WHB was modeled as a tubular plug-flow reactor with heat transfer. The shell-to-tube heat transfer coefficient was reported as 44.5 W/m²·K by Dimian and Bildea (2008)35.

Simulation of the catalytic section

The catalytic section of the Claus process includes preheaters, catalytic reactors, and condensers. An auxiliary furnace preheats the stream to the first reactor, while simple heat exchangers heat the feeds to the second and third reactors to 215 °C and 200 °C, respectively, with slight pressure drops. The catalytic reactors are modeled as adiabatic plug-flow reactors, each with a 1.4-meter catalytic bed. Reactor diameters are based on maintaining the same volume as the beds. The spherical catalyst used is activated alumina with a 4 mm diameter and 1300 kg/m2 density26. The specifications of the catalytic beds are as below:

Claus reactor | Length, mm | Diameter, m | Catalyst weight, Kg |

|---|---|---|---|

1st reactor | 1400 | 4625 | 18,650 |

2nd reactor | 1400 | 5046 | 13,650 |

3rd reactor | 1400 | 4625 | 16,850 |

In the first catalytic reactor, the hydrolysis reactions of carbon disulfide and carbonyl sulfide take place alongside the Claus reactions. Equation 11 to 13 show the hydrolysis reactions, and Table 12 gives the rate equations for these reactions.

In Aspen Plus, the condensers were modeled with a simple heat exchanger and a two-phase separator. Following the first through third catalytic reactors, the condensers reduce the reactor outlet temperatures to 181 °C, 173 °C, and 129 °C, respectively. Like the industrial condenser, each heat exchanger has a pressure drop of 0.035 bar.

Steady-state simulation of the superclaus process

Unlike the Claus process, the SuperClaus process uses SuperClaus catalysts in the final reactor to directly oxidize hydrogen sulfide into sulfur, with air supplying the necessary oxygen. Operational parameters differ slightly from the Claus process. In 2018, Shinkarev et al. studied the kinetics of hydrogen sulfide oxidation on carbon nanofiber-based SuperClaus catalysts18, identifying two side reactions (Eqs. 14–16). The catalysts, with a density of 2.2 g/cm237, have diameters between 1 and 5 mm, and 3 mm was used for simulation.

The rate equations for these reactions and their corresponding constants are presented in Table 13.

Since industrial data were unavailable for the SuperClaus reactor, this reactor and its operating conditions were designed using Aspen Plus optimization and the sequential-quadratic programming (SQP) method to maximize sulfur recovery. Decision variables included catalyst mass, air flow rate and temperature to the reactor, feed temperature, and airflow to the furnace. The constraint was to maintain the hydrogen sulfide molar percentage exiting the last Claus catalytic reactor between 0.8% and 1.5%.

Dynamic simulation of the superclaus process

Before dynamic simulation, equipment and valve sizes must be specified under normal conditions. Reactor sizes were provided earlier. Industrial data show that the first three condensers are horizontal (2.5 m long, 0.5 m diameter), and the fourth is vertical (0.75 m long, 2.5 m diameter). Control valves were sized to operate 50% open at the steady state condition.

Due to fast combustion reactions, dynamic modeling of the SuperClaus process creates a complex system of stiff ODEs and nonlinear equations, especially in the furnace. To address this, hydrogen sulfide combustion was modeled using Aspen’s plug-flow reactor, while hydrocarbon combustion used a stoichiometry reactor model.

Control structure of the superclaus process

Figure 2 shows the SuperClaus control system, which regulates hydrogen sulfide at the third condenser outlet instead of maintaining a H₂S/SO₂ ratio like the Claus process. A concentration controller adjusts the air-to-acid gas ratio based on H₂S content. The air splits before the furnace, with 30% sent to a bypass, and a flow controller manages total inlet airflow.

Airflow to the auxiliary furnace controls the first catalytic reactor’s inlet temperature, and a ratio controller adjusts the bypass acid gas flow accordingly. Preheaters regulate feed temperatures for the second Claus and direct oxidation reactors. The final condenser controls the tail gas temperature. Level controllers regulate condenser sulfur levels by adjusting the exit stream. Flow controller FC-AS maintains the SuperClaus reactor air supply. All controllers are listed in Table 2. The SuperClaus process with the main controllers was modeled in the AspenPlus dynamic simulator.

Controller tuning method

Proper control structure and parameters are essential for good dynamic performance under disturbances. Fast-acting level and flow controllers used Luyben’s heuristics and Aspen Plus Dynamics defaults38. For flow control, Luyben suggests a PI controller with a 0.5 gain and 0.3 min integral time, while Aspen defaults for level control are a gain of 10 and 60 min integral time. Aspen Plus Dynamics’ autotune feature, which uses the relay-feedback method, was applied to tune temperature and concentration controllers. Ultimate gain and period were determined by inducing sustained oscillations, and controller settings were calculated using the Tyreus-Luyben method.

Results and discussion

This section presents the steady-state and dynamic simulation results. First, we validate the Claus process steady-state results against plant data, followed by the SuperClaus steady-state results. Then, we show the controller tuning and the closed-loop dynamic performance of the SuperClaus unit.

Steady-state simulation of Claus process

Table 3 shows the simulated operating conditions of the Claus unit’s tail gas, including temperature, pressure, flow rate, and component mole percentages. A comparison with industrial data shows that all relative errors are within acceptable limits.

Steady-state simulation of superclaus process

As discussed, simulating the SuperClaus process requires replacing the Claus catalyst properties with those of a direct oxidation catalyst in Aspen Plus and optimizing the operating conditions. The AspenPlus optimizer conducts the optimization calculation. Table 4 represents the decision variables affecting the sulfur recovery.

This Table summarizes the optimization results, which increased sulfur recovery efficiency to 98.5% and reduced H₂S in the third condenser output to 1.39%.

The sensitivity analysis was performed to select these decision variables. For instance, Fig. 3 illustrates the sensitivity analysis results of the airflow inlet to the SuperClaus reactor. As can be observed in Fig. 3, the optimal mass flow of air supplied to the SuperClaus reactor is 16 kg/h. The air flow rate has varied from 15 to 18 kg/h, and its effect on the concentration of hydrogen sulfide in the tail gas has been plotted.

Table 5 compares the tail gas streams of the Claus and SuperClaus processes, showing a significant reduction in hydrogen sulfide from 4392 ppmv to nearly 0.0 ppmv. Sulfur recovery also improves from 95.9% to 98.5%, highlighting the effectiveness of the SuperClaus process.

The dynamic simulation results of the superclaus process

The following sections assess how well the control system handles step disturbances to the incoming acid gas, as defined in Table 6. All controllers in the SuperClaus dynamic simulation are PI-type. Table 7 presents their tuning results: rows 1–3 cover feed temperature controllers for the two Claus and one SuperClaus reactors; row 4 shows the tail-gas temperature controller; row 5 relates to the H₂S concentration controller after the third condenser; and rows 6–7 list flow and level controller parameters from Table 2.

The control system response to D1 and D2: ±20% step change in the feed temperature

In case of disturbance D1, fifteen minutes into the simulation, the acid gas feed temperature rises from 55 °C to 66 °C, which causes an abrupt increase in H₂S concentration after the third condenser (Fig. 3a). With an increase in the feed temperature, the volumetric flow rate of the acidic gas entering the reaction furnace rises, which reduces the residence time of the feed in the reaction furnace and consequently decreases the conversion of hydrogen sulfide. Therefore, the concentration of this component initially increases sharply, and as the concentration controller gradually increases the airflow rate to the reaction furnace, its concentration begins to decrease.

The controller raises the air-to-acid gas ratio setpoint to correct this, as shown in Fig. 3b, leading to increased airflow into the reaction furnace (Fig. 3c). Initially, the air valve opening and airflow drop briefly (Fig. 3c, d) due to a quick rise in acid gas volumetric flow, prompting the feed valve to reduce the acid gas flow before the controller adjusts the air ratio. Disturbance D1 impacts the reactor temperature controllers When the first reactor’s feed temperature rises, its controller reduces air to the auxiliary furnace, lowering the bypass acid gas flow. In contrast, D1 causes the second reactor’s feed temperature to drop due to reduced air, lowering the first reactor’s output rate and reducing flow to the second condenser. As a result, the condenser overcools the gas, and the preheater compensates by increasing its heat load. The SuperClaus reactor’s controller behaves similarly to the second reactor controller. The tail gas temperature controller is barely affected, and control is maintained effectively. All four condenser-level controllers performed well, so their responses are not shown.

For disturbance D2, controller responses are opposite to those in D1. The H₂S mole fraction at the third condenser outlet decreases as the acid gas temperature drops. The concentration controller compensates by lowering the air-to-acid ratio, reducing airflow. Meanwhile, the first reactor feed temperature drops, prompting its controller to increase auxiliary furnace airflow, which raises bypass acid gas flow, so the second reactor feed temperature increases due to higher flow from the first reactor. The condenser cannot fully cool the stream, so the second reactor’s controller reduces the preheater heat load. The SuperClaus reactor’s controller responds similarly. D2 also raises the last condenser’s outlet temperature, which is corrected by reducing its heat load. Liquid sulfur level controllers performed well, so their responses are not shown.

The control system response to D3 and D4: ±5% step change in the H2S feed concentration

For disturbance D3, as the concentration of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) increases in the acid gas, its levels at the outlet of the third condenser also rise. Figure 4 illustrates the controller’s responses and their effects on the feed temperature controllers of the catalytic reactors. In response, the concentration controller adjusts by increasing the air-to-acid gas ratio. This change aims to enhance the conversion of H₂S in the furnace, which helps return the outlet concentration to its designated set point.

The controllers respond to the disturbance D4 in the opposite way to D3. When H₂S in the acid gas feed decreases, its concentration at the third condenser’s outlet also drops. The controller lowers the air-to-acid gas ratio to maintain the setpoint, reducing H₂S conversion in the furnace and restoring the outlet concentration. Reactor temperature controller responses are similar to those for D3, so they are not repeated here. In all cases, the temperature controllers effectively rejected the disturbance.

The control system response to D5 and D6: ±10% step change in the feed pressure

In case of the disturbance D5, fifteen minutes into the simulation, a 10% increase in acid gas feed pressure increases the molar flow of acid gas and air to the furnace. Figure 5 illustrates this response to disturbance D5.

An increase in acid gas pressure at the reactor furnace inlet causes a sudden surge in the stream’s flow rate, consequently reducing the residence time within the reaction furnace. This reduced residence time lowers the conversion efficiency of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). As a result, the H₂S concentration in the output from the fourth condenser rises, triggering the concentration controller to increase the furnace air intake. This corrective action boosts the H2S conversion to reduce the H₂S level. Due to a slightly oscillatory response, the H₂S concentration undershoots the setpoint before eventually stabilizing at the target value.

In the short term, this boosts flow rates; however, in the long term, it increases the H₂S concentration at the outlet of the fourth condenser. This change triggers the concentration controller to adjust airflow and restore the setpoint. The disturbance has minimal impact on the inlet temperatures of the Claus and SuperClaus reactors, which the temperature controllers swiftly correct. Additionally, level controllers ensure that the liquid levels in the condensers remain at their setpoints.

The disturbance D6 initially reduces acid gas and air flow rates. Over time, lower H₂S at the fourth condenser’s outlet activates the concentration controller, which adjusts airflow to restore the setpoint. Reactor inlet temperatures are largely unaffected, and temperature and level controllers maintain their setpoints.

Conclusion

This study conducted steady-state and dynamic simulations of the SuperClaus process by using AspenPlus and AspenPlus dynamics software. Although there are some research works that simulated the Clause SRU units but this works differs in several respects as shown in Table 8.

Industrial data for a Claus unit verified the simulation results for the Claus process at steady-state conditions. For instance, the relative error percentages for hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide concentrations in the tail gas stream are 8.10% and 5.56%, respectively, and the relative error percentage for sulfur recovery in the Claus unit is 0.84%. To simulate the SuperClaus process, we calculated some of the unknown design parameters of the SuperClaus process so that they maximize the sulfur recovery percentage. A comparison between the simulation results of the Claus and SuperClaus processes indicates that changing from the Claus to the SuperClaus process can increase the sulfur recovery percentage from 95.9% to 98.5% and reduce the concentration of hydrogen sulfide present in the tail gas from 4392 ppmv to zero.

Table 9 represents a comparison between Claus and SuperClaus process. Furthermore, this research investigated the dynamic behavior of the SuperClaus process in response to step changes in the feed temperature, concentration, and pressure. The dynamic simulation results show that the process control system could reject the disturbances and adjust the controlled variables at their set points.

Also, the simulation results confirmed that the worst disturbance is the variation of hydrogen sulfide concentration in the feed stream. Although the step change in the feed temperature can be as significant as 20% and 10%, respectively, the hydrogen sulfide concentration change in the acid gas feed cannot become more than 5% because the control valve on the inlet airflow to the auxiliary furnace gets saturated.

Data availability

The data used in this study were generated through simulation and would be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mokhatab, S., Poe, W. A. & Mak, J. Handbook of Natural Gas Transmission and Processing: Principles and Practices (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/C2013-0-15625-5

Ghahraloud, H., Farsi, M. & Rahimpour, M. Modeling and optimization of an industrial Claus process: thermal and catalytic section. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 76, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2017.03.005 (2017).

Nehb, W. & Vydra, K. Sulfur. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00897990360a

Bennett, H. & Meisen, A. Hydrogen sulphide—air equilibria under Claus furnace conditions. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 51 (6), 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.5450510616 (1973).

Fischer, H. Burner/fire box design improves sulfur recovery. (1974).

Monnery, W. D., Svrcek, W. Y. & Behie, L. A. Modelling the modified Claus process reaction furnace and the implications on plant design and recovery. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 71 (5), 711–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.5450710509 (1993).

Steijns, M. et al. The mechanism of the catalytic oxidation of hydrogen sulfide: II. Kinetics and mechanism of hydrogen sulfide oxidation catalyzed by sulfur. J. Catal. 42 (1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9517(76)90094-4 (1976).

Tong, S., Dalla Lana, I. & Chuang, K. Kinetic modelling of the hydrolysis of carbonyl sulfide catalyzed by either Titania or alumina. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 71 (3), 392–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.5450710308 (1993).

Tong, S., Dalla Lana, I. & Chuang, K. Kinetic modeling of the hydrolysis of carbon disulfide catalyzed by either Titania or alumina. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 73 (2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.5450730208 (1995).

Tong, S., Dalla Lana, I. G. & Chuang, K. T. Effect of catalyst shape on the hydrolysis of COS and CS2 in a simulated Claus converter. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 36 (10), 4087–4093. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie970277g (1997).

Karan, K. An Experimental and Modeling Study of Homogeneous Gas Phase Reactions Occurring in the Modified Claus Process (University of Calgary, 1998). http://hdl.handle.net/1880/42546

Karan, K., Mehrotra, A. K. & Behie, L. A. COS-forming reaction between CO and sulfur: A high-temperature intrinsic kinetics study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 37 (12), 4609–4616. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie9802966 (1998).

Karan, K., Mehrotra, A. K. & Behie, L. A. A high-temperature experimental and modeling study of homogeneous gas-phase COS reactions applied to Claus plants. Chem. Eng. Sci. 54, 15–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2509(98)00475-8 (1999).

Karan, K. & Behie, L. A. CS2 formation in the Claus reaction furnace: a kinetic study of methane – sulfur and methane – hydrogen sulfide reactions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 43 (13), 3304–3313. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie030515+ (2004).

Hawboldt, K. A. N. Kinetic modelling of key reactions in the modified Claus plant front end furnace. (1998). http://hdl.handle.net/1880/42493

Hawboldt, K., Monnery, W. & Svrcek, W. New experimental data and kinetic rate expression for H2S pyrolysis and re-association. Chem. Eng. Sci. 55 (5), 957–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2509(99)00366-8 (2000).

Monnery, W. et al. New experimental data and kinetic rate expression for the Claus reaction. Chem. Eng. Sci. 55 (21), 5141–5148. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2509(00)00146-9 (2000).

Shinkarev, V., Kuvshinov, G. & Zagoruiko, A. Kinetics of H2S selective oxidation by oxygen at the carbon nanofibrous catalyst. Reaction Kinetics Mech. Catal. 123 (2), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11144-017-1339-z (2018).

Zarei, S. et al. Thermo-kinetic modeling and optimization of the sulfur recovery unit thermal stage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 103, 1095–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.05.012 (2016).

Kazempour, H., Pourfayaz, F. & Mehrpooya, M. Modeling and multi-optimization of thermal section of Claus process based on kinetic model. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 38, 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.12.038 (2017).

Kardan, M. H. & Eslamloueyan, R. Investigating three different models for simulation of the thermal stage of an industrial split-flow SRU based on equilibrium-kinetic approach with heat loss. Chem. Prod. Process Model. 14 (1), 20180025. https://doi.org/10.1515/cppm-2018-0025 (2018).

Mehmood, A. et al. An evaluation of kinetic models for the simulation of Claus reaction furnaces in sulfur recovery units under different feed conditions. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 74, 103106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2019.103106 (2020).

Abedini, R., Salooki, M. K. & Ghasemian, S. Modeling and simulation of condensed sulfur in catalytic beds of Claus process: rapid Estimation. Chem. Eng. Res. Bull. 14 (2), 110–114. https://doi.org/10.3329/cerb.v14i2.5595 (2010).

Asadi, S., Pakizeh, M., Pourafshari, M. & Chenar An investigation of reaction furnace temperatures and sulfur recovery. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 5, 362–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11705-011-1106-z (2011).

Manenti, F. et al. Model-based optimization of sulfur recovery units. Comput. Chem. Eng. 66, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2014.01.019 (2014).

Nabikandi, N. J. & Fatemi, S. Kinetic modelling of a commercial sulfur recovery unit based on Claus straight through process: comparison with equilibrium model. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 30, 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2015.05.001 (2015).

Nabgan, W. & Simulation of Claus Process Via Aspen Hysys for Sulfur Recovery., A Chem. Prod. Process Model., 11(4): 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1515/cppm-2016-0019 (2016).

Al Hamadi, M., Ibrahim, S. & Raj, A. Effects of oxygen enrichment on natural gas consumption and emissions of toxic gases (CO, Aromatics, and SO2) in the Claus process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58 (36), 16489–16501. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b03408 (2019).

Ibrahim, S., Rahman, R. K. & Raj, A. Dual-stage acid gas combustion to increase sulfur recovery and decrease the number of catalytic units in sulfur recovery units. Appl. Therm. Eng. 156, 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.04.105 (2019).

Hashemi, M., Pourfayaz, F. & Mehrpooya, M. Simulation, equipment performance evaluation and sensitivity analysis as a comprehensive parametric study of sulfur recovery unit. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 15 (2), e2427. https://doi.org/10.1002/apj.2427 (2020).

Rao, N. K. & Haydary, J. Studies on sulfur recovery plant performance using Aspen hysys sulsim simulations. Petroleum Coal. 61 (2), p292–305 (2019).

Greenwood, N. N. & Earnshaw, A. Chemistry of the Elements (Elsevier, 2012).

Westbrook, C. K. & Dryer, F. L. Simplified reaction mechanisms for the oxidation of hydrocarbon fuels in flames. Combust. Sci. Technol. 27 (1–2), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6 (1981).

Dowling, N. I., Hyne, J. B. & Brown, D. M. Kinetics of the reaction between hydrogen and sulfur under high-temperature Claus furnace conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 29 (12), 2327–2332. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie00108a004 (1990).

Dimian, A. C. & Bildea, C. S. Chemical Process Design: Computer-aided Case Studies (Wiley, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527621583

Jones, D. et al. Rigorous kinetic modeling and optimization study of a modified Claus unit for an integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) power plant with CO2 capture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51 (5), 2362–2375. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie201713n (2012).

Al-Saleh, M. H. & Sundararaj, U. Review of the mechanical properties of carbon nanofiber/polymer composites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac. 42 (12), 2126–2142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.08.005 (2011).

Luyben, W. L. Distillation Design and Control Using Aspen Simulation (Wiley, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118510193

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. Eslamloueyan developed the concept of work and supervised the research. He also wrote the manuscript.T. Kazemi did simulation and made Figures and tables. She also reviewed literature and provided references.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazemi, T., Eslamloueyan, R. Design, optimization and controllability analysis of an improved sulfur recovery unit based on SuperClaus process. Sci Rep 16, 4118 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33984-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33984-7