Abstract

The important risk factor of edentulism provides a new perspective and entry point for the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases (NDs). Nevertheless, previous studies mostly focused on the short-term effects of a single factor and ignored the combined effects of long-term and multiple factors. We aim to comprehensively ascertain the impact of edentulism on the risk of NDs among middle-aged and older adults. We conducted a longitudinal analysis of respondent data from 2011 to 2020 in the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS) to investigate the association between the two. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to reduce the effects of bias and confounding, and the Cox proportional hazards model was applied to evaluate the association between edentulism and risk of NDs. Among 10,851 respondents, incidence of NDs were 29.5% (2935/9942) among respondents without edentulism and 44.1% (401/909) among those with edentulism. After PSM, respondents with edentulism showed a higher risk of NDs (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.45, P = 0.005) over time compared with traditional multivariable Cox analysis. Hearing impairment, heart disease and hypertension are important factors that exacerbate the progression of NDs. Sensitivity and subgroup analysis showed the results were still stable. A significant interaction (P for interaction = 0.030) was found between edentulism and age, particularly in the 45–64 age group. A comprehensive and targeted strategy for the 45–64 age group to practice good oral hygiene, combined with personalized management of specific health conditions, can be instrumental in preventing NDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the global acceleration of population aging, neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) among middle-aged and older adults1 have become an increasingly severe public health issue. NDs are a group of disorders characterized by the progressive loss of structure and function of specific neuronal populations. This study investigates a spectrum of conditions involving neurodegeneration, including both chronic progressive forms such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), as well as conditions where an acute insult (e.g., stroke, traumatic brain injury(TBI)) initiates a secondary neurodegenerative process2. Together, these conditions represent major causes of disability and mortality worldwide, posing significant challenges to global health systems.

The incidence of NDs is rising currently, there are no effective cures, making early prevention and intervention particularly critical. Previous studies have identified multiple risk factors for NDs, including genetic predispositions3, environmental exposures4, and lifestyle factors such as sleep quality5 and physical activity6. Despite the increasing understanding of these traditional risk factors, the developmental mechanism of NDs still cannot be fully explained. Therefore, searching for new potential risk factors is crucial for better prevention and prognosis of NDs.

At the same time, oral health problems are also very common among middle-aged and older adults. Edentulism, a more serious oral disease, not only impairs chewing, swallowing and speech function, but also has potential impact on systemic health status. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that the South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions experience the highest burden of oral diseases7. Moreover, individuals with missing teeth have been found to have a life expectancy 10 to 20 years shorter than those with a full set of teeth. In China, approximately 80% of adults aged 65 to 74 are affected by edentulism8. Research also suggests that older adults with total tooth loss face a significantly increased risk of disability within five years9 and a reduced life expectancy10. Thus, investigating whether edentulism constitutes a significant risk factor for NDs is crucial, offering a novel perspective for NDs prevention.

Emerging evidence indicates that oral health problems influence cognitive function, leading to NDs. The potential mechanisms linking oral diseases with degenerative neurological disorders in the brain like AD and PD, have garnered considerable academic interest. However, most research has focused on developed regions such as Europe, North America, Japan, and South Korea11, with limited exploration in developing countries like China. Additionally, many studies examine short-term effects of isolated factors, overlooking the combined effects of multiple factors. Predominantly reliant on clinical oral trials and cross-sectional designs, existing research often suffers from limited sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and single study design12. Moreover, existing research has not fully considered the influence of confounding factors, resulting in insufficient explanatory power and reliability of the results13. These limit our comprehensive understanding of the role of edentulism in the risk of NDs.

Our study aims to comprehensively explore the relationship between edentulism and the risk of NDs in middle-aged and older adults through a ten-year cohort study using the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database. To address the limitations of prior research, we employed propensity score matching (PSM) to control for confounding factors and used a Cox regression model to analyze time-dependent risks. Additionally, subgroup analyses were conducted to examine heterogeneity in the impact of edentulism on the risk of NDs across different populations. Robustness tests were also performed to enhance the credibility of the findings. This study seeks to accurately identify the unique role of edentulism in NDs risk, providing a robust scientific foundation for future prevention and treatment strategies.

Methods

Study design and participants

The research utilized data from CHARLS, a comprehensive and nationally representative survey that tracks the health and well-being of individuals over 45 years old in China14. Initiated in 2011, CHARLS has consistently followed up with respondents at 2 to 3 year intervals, with data currently available up to the year 2020. Survey respondents provided written consent, and more information is accessible on the CHARLS website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en). The Biomedical Ethical Review Committee of Peking University approved the ethics of the study. The main household survey’s ethical approval number was IRB00001052-1101515.

This cohort study utilized data from the CHARLS across five waves from 2011 to 2020. Enrollment at the outset included 17,708 individuals. The average follow-up period was approximately 8.8 years, in line with the design expectations of the decade-long cohort study’s design.

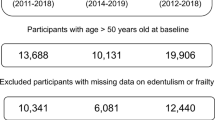

The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) age ≥ 45 years; (2) participation in the CHARLS survey between 2011 and 2020; (3) availability of complete data on edentulism status, NDs, and all relevant covariates at baseline. Exclusion criteria were: (1) missing data on edentulism, NDs, or relevant covariates (n = 5,139); (2) loss to follow-up or death prior to the second survey wave (n = 1,446); and (3) a diagnosis of NDs at baseline (n = 272). The final analysis included 10,851 respondents (Fig. 1).

Measurements

Assessment of edentulism

Edentulism was considered as the exposure variable in this study. In this study, the edentulism group was defined as participants who had lost all their natural teeth at baseline. The control group includes participants who did not lose all teeth at baseline or only had a few missing teeth but did not meet the criteria for edentulism. All participants confirmed their baseline dental status by self-report. The validity of self-reported tooth status is reported elsewhere16,17. The calculated starting point of the survival time is the status confirmation time at the baseline. For the edentulism group, survival time was calculated from the baseline confirmed edentulism. Control survival time was calculated from the healthy tooth condition recorded at baseline.

Assessment of NDs

The dependent variable was physician-diagnosed conditions that involve significant neurodegeneration. This includes chronic progressive neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., AD, PD) and acute cerebrovascular or traumatic events (e.g., stroke, TBI) which are recognized to lead to secondary neurodegenerative pathways and are thus relevant in the context of studying overall neurodegeneration risk18,19.

The presence of NDs was identified through a questionnaire that inquired about common diseases. A primary query was: “Have you been diagnosed with the following diseases by a doctor? (Yes or No)”. According to previous research by relevant scholars, our study mainly focuses on NDs under different types and symptom conditions, such as memory-related disease (e.g. AD, PD)20, stroke21. The study considered the interval from baseline to the initial diagnosis of NDs as the duration for survival analysis, with the analysis period extending to the last follow-up for those without NDs.

Covariates

The study selected potential variables across socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle behaviors, and medical history, informed by existing literature22. Key covariates encompassed sex (male or female), age groups (45–64 years as middle-aged and ≥ 65 years as older adults), residence area (village or city/town), education level (illiteracy or informal education, Elementary school or above), geographical region, and body mass index (BMI, underweight to obese) categories23. The division of China into eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions followed the criteria from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS)24. Lifestyle behaviors included smoking and drinking habits (Yes or No), sleeping duration (sleep time < 6 h or ≥ 6 h). Medical history encompassed hearing problems, heart disease history, stroke, hypertension, and diabetes history, all assessed as binary variables (Yes or No)25.

Statistical analyses

In this study, participants’ baseline characteristics were presented using frequencies and percentages. The differences across edentulism groups were evaluated via descriptive statistics and chi-square tests among baseline.

To address missing data, which accounted for 7.2% of all covariates and were assumed to be missing at random, multiple imputation was performed using a random forest-based algorithm suitable for capturing complex variable interactions. The imputation process was considered satisfactory once the out-of-bag (OOB) imputation error stabilized below a pre-set threshold. As an internal validation, we compared the distributions of the imputed and observed data and confirmed that the means, standard deviations, and inter-variable correlations remained consistent, supporting the plausibility of the imputed values. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), to consider the association between edentulism and NDs and to address time-dependence. The proportional hazards assumption was verified and found to be satisfied using Schoenfeld residual tests (global P > 0.05).

Referring to previous studies26, to minimize potential treatment allocation bias and confounding, Cox regression with PSM was used to estimate the likelihood of patients experiencing NDs based on variables such as socio-demographic characteristics (sex, age, residence, marital status, education level, region, BMI), lifestyle behaviours (smoking habits, drinking habits, sleeping duration) and medical history (hearing problems, heart disease history, hypertension, and diabetes history). It is beneficial to elucidate the impact of various factors on survival and disease prognosis. Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression model, and 1:1 nearest neighbor matching without replacement was performed with a caliper width of 0.01 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. We assessed the quality of propensity score matching using the standardized mean difference (SMD), with a threshold of less than 0.1 considered acceptable.

To identify possible variations in the interaction effect of the edentulism on NDs risk across diverse subgroups, respondents were categorized into separate subgroups depending on different sociodemographic variables, using forest plots for visualization. All analyses were conducted using Stata/MP version 17.0 and R Version 4.2.3. Statistical significance was determined as a p-value below 0.05 through two-sided testing.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table S1 showed the characteristics of respondents with different edentulism. Our study included a total of 10,851 respondents, of whom 909 self-reported having edentulism, the mean age was 59.0 years (ranging from 45 to 101). After PSM, we obtained 907 matched pairs of respondents (Table 1). The majority of respondents were female (54.69% of the total) and fell within the 45–64 age bracket, with 72% of the respondents residing in city areas. Regarding lifestyle behaviors, 36% of respondents smoked, and 43.88% consumed alcohol. 61.47% reported sleeping less than 6 h per night. Within the scope of medical history, 68.3% of the respondents experienced hearing issues.

A P-value exceeding 0.05 for all covariates indicated a substantial overlap in propensity scores, suggesting effective matching. After PSM, we obtained 907 matched pairs of respondents. Balance diagnostics confirmed that all covariates were well-balanced, with SMD below the threshold of 0.1. The SMD plot (Figure S1) visually illustrates the improvement in covariate balance before and after matching, while the probability density analysis (Figure S2) further confirmed a substantial overlap in propensity score distributions between groups, indicating adequate sample similarity for subsequent analysis. Figure S3 showed the receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC) of incidence of NDs in participants with/without edentulism after PSM.

Longitudinal association of baseline edentulism with NDs at follow-up, 2011–2020

During the 9-year follow-up, incidence of NDs were 29.5% (2,935/9,942) among respondents without edentulism and 44.1% (401/909) among those with edentulism (Table 2). Notably, respondents with edentulism exhibited higher incidence of NDs with crude analysis (chi-squared test: P < 0.001). After adjustment for all of the covariates, the HR was 1.20 (95% CI, 1.07 to 1.35, P = 0.002) in the multivariable Cox regression analysis. The matched analysis confirmed a statistically significant association between edentulism and NDs over time, with a 24% increase in the risk of adverse outcomes associated with NDs (HR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.07 to 1.45, P = 0.005) (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis after PSM

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using four different models to further validate the stability of the results, as presented in Table S3. Subgroup analysis (Fig. 2), stratified by socio-demographic factors, revealed that the risk of NDs due to edentulism was notably higher among females, individuals aged 45–64, those residing in rural areas or the eastern region, and those with obesity or limited education. Interaction effects between edentulism and age were statistically significant (P for interaction = 0.030), with effects being more significant in the 45–64 age group (Figure S4).

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative cohort of middle-aged and older Chinese adults, we found that edentulism was associated with a modest but statistically significant 24% increase in the risk of developing NDs over a decade of follow-up. This finding, derived after robust adjustment for potential confounders using a PSM-Cox model, indicates a consistently higher incidence of NDs among edentulous respondents (44.1%) compared to their non-edentulous counterparts (29.5%), corresponding to a 14.6% absolute risk difference. To our knowledge, this is the first study to employ this rigorous approach to extensively investigate this relationship in a national sample, effectively reducing data bias and confounding to enhance the stability and accuracy of the results. The association remained consistent across sensitivity and subgroup analyses, underscoring its robustness. Given the high prevalence of edentulism and the substantial baseline incidence of NDs in China’s aging population, this modest relative risk may translate into a significant disease burden at the population level, underscoring the potential value of integrating oral health into broader preventive strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

The specific mechanism of the association between edentulism and NDs

Our findings of a significant association between edentulism and increased risk of NDs are consistent with growing evidence positioning oral health as a modifiable risk factor for neurological decline. It is important to note that our observational study did not directly investigate the underlying biological mechanisms. Instead, we acknowledge that several pathways proposed in the literature may explain this association between edentulism and NDs, including loss of chewing function, chronic inflammation27, microbial imbalances28, and malnutrition29.

Firstly, edentulism-induced masticatory dysfunction reduces mechanical stimulation of the trigeminal and facial nerves, which project to cognitive-related brain regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex30. Chronic under-stimulation leads to decreased neuronal activity and reduced synaptic connections in the brain, accelerating cognitive decline and inducing NDs. Animal studies have confirmed increased neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampal region of rats following tooth extraction31. Secondly, the role of oral pathogenic microorganisms cannot be overlooked. Edentulous patients often suffer from chronic periodontal infections. Oral pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis can breach the blood-brain barrier via the circulatory system32. The gingipains they secrete degrade tau protein in the brain, promoting the formation of neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles are the primary cause of neuronal fiber degeneration and a hallmark pathological feature of AD33,34, further accelerating the development or progression of NDs. Moreover, chronic oral inflammation associated with edentulism continuously releases proinflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α. These factors enter the central nervous system via the peripheral circulation, activate microglia, and trigger neuroinflammation, which is a core pathological mechanism underlying NDs like PD and AD35,36.

The interaction between age and the relationship between edentulism and NDs

Our subgroup analysis revealed a significant interaction between edentulism and age (P for interaction = 0.030). While advanced age is a well-established risk factor for NDs such as AD and PD37, it is noteworthy that in our study, older adults (≥ 65 years) with edentulism did not exhibit a statistically significant increase in NDs risk compared to their non-edentulous counterparts. In contrast, middle-aged individuals with edentulism had a 1.76 times higher risk of developing NDs than those without edentulism. This suggests that midlife may represent a critical window for intervention.

Mechanistically, we hypothesize that the age-related discrepancy may be attributed to two potential factors. First, we hypothesize that the 45–64 years group may represent a critical “neurofunctional sensitive period” where neural function remains relatively intact but lacks the cumulative resilience of younger age groups, rendering it highly susceptible to damage from edentulism-induced masticatory dysfunction and subsequent insufficient nutrient absorption, and such nutritional imbalances have been shown to impair neuronal repair mechanisms, directly heightening NDs risk38. In contrast, adults ≥ 65 years already exhibit age-driven neurodegenerative changes and diminished neural reserve, where the additional risk from edentulism is overshadowed by other age-related NDs drivers. Certainly, this interpretation remains hypothetical and requires validation through future longitudinal studies incorporating direct neurobiological and oral health measures. Second, edentulism in the 45–64 years group is often pathological and accompanied by chronic oral inflammation, an established contributor to neuroinflammation (a core pathophysiology of NDs). While denture adaptation rates in this group are lower, leaving masticatory and inflammatory damage uncompensated. For adults ≥ 65 years, edentulism is mostly age-related physiological tooth loss, with higher denture use mitigating functional deficits39,40.

Since people aged ≥ 65 years are affected by age-related edentulism, our findings underscore the greater potential value of targeting dental health interventions in the 45–64 age group for the prevention of NDs. Certainly, further longitudinal and mechanistic studies are needed to confirm these observations.

Correlation between edentulism and NDs in response differences in different subgroups

The results of subgroup analyses showed that the risk of NDs among female respondents with edentulism is significantly higher than those without edentulism. Studies indicate that many diseases, such as periodontal disease and AD, show a female predilection41, particularly with higher incidence rates among postmenopausal women42, which may be due to changes in the immune system resulting from the decline in estrogen levels after menopause in women. We speculate this hormonal change may affect the oral microbiome, further increasing the risk of NDs due to periodontal disease. Sex-based disease susceptibility should be considered comprehensively in the future, which would affect the response of gender differences to the prevention or treatment of NDs43.

The results of the subgroup analysis indicated that the edentulism group respondents from rural and eastern regions of China had a greater risk of developing NDs compared with non-edentulism respondents. Previous studies have found that developed countries, with advanced medical systems and high socio-economic levels, have matured the popularization of oral health care, and the progression patterns of edentulism and NDs are relatively slow44. In contrast, we speculate developing countries are deeply mired in a dual dilemma: firstly, the scarcity of medical resources and insufficient public health literacy have led to the proliferation of oral diseases, resulting in a high incidence of edentulism45. The second is the rapid aging combined with environmental and lifestyle factors, resulting in a heavy burden and complex condition of NDs. In rural areas of China, the allocation of dental medical resources is uneven, and a large number of middle-aged and older adults are prone to developing edentulism due to difficulty in correcting oral problems in a timely manner. The risk of NDs such as AD increases with the age of edentulism46. At the same time, the economic level of rural residents is relatively low, the health awareness of the elderly is weak, the lack of cognition of edentulism harm, delayed treatment time, and may lack of treatment of standard dentures, exacerbating the risk of NDs47. In addition, edentulism leads to impaired chewing function, and inadequate grinding of food enters the digestive system, affecting nutrient intake and weakening the body’s resistance to NDs48.

Moreover, during the period of social transformation in developing countries, especially in the eastern region of China, which serves as a window for opening up to the outside world, the economic rise is accompanied by rapid changes in lifestyle49. In the context of edentulism, we speculate high sugar and high salt diets, insufficient physical activity, increasing mental stress50, smoking and drinking are common51, have led to the prominent problem of obesity52, further exacerbating the risk of neurodegenerative changes. By comparison, it can be seen that rural and eastern areas may be interwoven by various factors, and precise intervention strategies are urgently needed to prevent and control NDs caused by edentulism. This is conducive to narrowing the health gap, contributing to global health equity, helping to rewrite the dilemma of developed countries’ experience that is difficult to transplant, and opening up a unique health management path for developing countries.

Furthermore, respondents in the edentulism group with higher levels of education have a low risk of developing NDs. The likely reason for this is that education also prevents and delays the onset and progression of certain NDs by creating a knowledge base and health behaviours such as protecting oral health, providing a compensatory mechanism for the remission of certain neuropathies53.

Research implications and practical value

In light of these findings and considering the pursuit of healthy aging, our findings not only have enlightening significance for the development of targeted screening and intervention programs for the middle-aged and older adults, but also paves the way for collaborative research between geriatric oral health and the disciplines of neuroscience.

From a clinical perspective, for the high-risk subgroup aged 45–64 identified in this study, dental clinics could intensify education on the “oral health-systemic health” connection. For patients with edentulism, it could be beneficial to conduct oral examinations regularly while considering the potential addition of rapid cognitive function screening. In addition, neurology departments may incorporate “history of edentulism” into NDs risk assessment checklists, prioritizing biomarker testing for edentulous patients to enhance early diagnosis rates of AD/PD. For rural and eastern regions, it might be valuable to expand oral health service coverage to reduce the incidence of edentulism caused by insufficient medical resources. Concurrently, oral health management should be integrated into community NDs prevention programs, such as providing free denture fitting services for edentulous seniors to mitigate the negative impact of chewing dysfunction on neurological health. These proposed implications are exploratory and derived from the observed epidemiological associations. Their clinical utility and cost-effectiveness warrant further evaluation in dedicated implementation studies. In brief, it is recommended that targeted intervention guidance be provided for relevant high-risk groups in subgroup analysis, by fostering awareness of the importance of protecting teeth and encouraging the practice of healthy behaviors54,55, as well as increasing the accessibility of medical resources for these populations, we can maximize the prevention of NDs and delay the progression of the disease.

Limitations and future prospects

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged and that inform avenues for future research. First, while the observational nature of our data precludes definitive causal claims, future studies employing longitudinal designs with more frequent assessments could better elucidate the temporal relationship between oral health and neurological decline. Second, the use of self-reported measures for both edentulism and NDs, though practical for a large-scale survey, may be subject to misclassification and recall bias. Future research incorporating clinical dental examinations and biomarker-confirmed NDs diagnoses would help to validate our findings. Third, despite our efforts to control for confounding through PSM, the possibility of reverse causality whereby undetected cognitive impairment leads to poor oral hygiene and subsequent tooth loss cannot be entirely discounted. Prospective studies that actively screen for and exclude participants with early cognitive deficits at baseline would be valuable in mitigating this concern.

Fourth, our definition of edentulism as complete tooth loss, while clear, does not capture the nuances of partial tooth loss or denture use. Subsequent investigations collecting detailed information on denture quality, periodontal health, and the pattern of tooth loss could provide a more granular understanding of the exposure. Fifth, The composite nature of our NDs outcome, while enhancing statistical power, may mask heterogeneity among specific diseases. Although we conducted extensive subgroup analyses to explore potential heterogeneity, these analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Consequently, some observed interactions, particularly those with wider confidence intervals or borderline significance, should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory, to avoid an increased risk of Type I errors. Therefore, examining the association with individual NDs subtypes in dedicated cohorts with sufficient sample size represents an important next step. Finally, the potential for survival bias in our aging cohort and the exploratory nature of our subgroup analyses suggest that the observed associations should be interpreted with caution. Future work could explicitly model competing risks and pre-specify subgroup hypotheses to confirm the heterogeneity we observed.

Conclusion

We have confirmed that exposure to edentulism in middle-aged and older adults is associated with an increased risk of NDs over time and found that interventions targeting the 45–64 age group are more meaningful. The association between the two is stronger in subgroups such as women, those living in eastern and rural areas, obese individuals, and those with lower levels of education. Additionally, we can enhance preventive measures and treatment strategies, ultimately contributing to a more holistic approach to NDs patient care.

Data availability

The data involved in this study are publicly available and can be found at: https://charls.pku.edu.cn/ (accessed on 26 September 2023). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- NDs:

-

Neurodegenerative diseases

- CHARLS:

-

China health and retirement longitudinal study

- PSM:

-

Propensity score matching

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- WHO:

-

The world health organization

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- NBS:

-

National bureau of statistics of China

- SMD:

-

The standard mean difference

References

Leng, Y., Musiek, E. S., Hu, K., Cappuccio, F. P. & Yaffe, K. Association between circadian rhythms and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 18, 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30461-7 (2019).

D’Arrigo, C., Labbate, S. & Galante, D. Boosting the therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells via advanced preconditioning for neurodegenerative disorders. Stem Cells Int. 2025 (2616653). https://doi.org/10.1155/sci/2616653 (2025).

Zhang, W., Chen, T., Zhao, H. & Ren, S. Glycosylation in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 56, 1208–1220. https://doi.org/10.3724/abbs.2024136 (2024).

Peters, S., Bouma, F., Hoek, G., Janssen, N. & Vermeulen, R. Air pollution exposure and mortality from neurodegenerative diseases in the netherlands: A population-based cohort study. Environ. Res. 259, 119552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119552 (2024).

Lysen, T. S., Ikram, M. A., Ghanbari, M., Luik, A. I. & Sleep 24-h activity rhythms, and plasma markers of neurodegenerative disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 20691. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77830-4 (2020).

Wu, P. F. et al. Assessment of causal effects of physical activity on neurodegenerative diseases: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Sport Health Sci. 10, 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.01.008 (2021).

Tu, C. et al. Burden of oral disorders, 1990–2019: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2019. Arch. Med. Sci. 19, 930–940. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms/165962 (2023).

Zhang, Q., Kreulen, C. M., Witter, D. J. & Creugers, N. H. Oral health status and prosthodontic conditions of Chinese adults: a systematic review. Int. J. Prosthodont. 20, 567–572 (2007).

Holm-Pedersen, P., Schultz-Larsen, K., Christiansen, N. & Avlund, K. Tooth loss and subsequent disability and mortality in old age. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 56, 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01602.x (2008).

Schmidt, J. C. et al. Dental and periodontal health in a Swiss population-based sample of older adults: a cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 128, 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/eos.12738 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Tooth loss and the risk of cognitive decline and dementia: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Front. Neurol. 14, 1103052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1103052 (2023).

Hajian-Tilaki, K. Sample size Estimation in diagnostic test studies of biomedical informatics. J. Biomed. Inf. 48, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.013 (2014).

Kuang, S. et al. The effect of root orientation on inferior alveolar nerve injury after extraction of impacted mandibular third molars based on propensity score-matched analysis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 23, 929. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03661-0 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Association of visceral adiposity index and handgrip strength with cardiometabolic multimorbidity among middle-aged and older adults: findings from charls 2011–2020. Nutrients 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142277 (2024).

Kusama, T. et al. Weight loss mediated the relationship between tooth loss and mortality risk. J. Dent. Res. 102, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345221120642 (2023).

Zhang, X. & Chen, S. Association of childhood socioeconomic status with edentulism among Chinese in mid-late adulthood. BMC Oral Health. 19, 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0968-1 (2019).

Vercruysse, P., Vieau, D., Blum, D., Petersén, Å. & Dupuis, L. Hypothalamic alterations in neurodegenerative diseases and their relation to abnormal energy metabolism. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2018.00002 (2018).

Li, K. R. et al. The key role of magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of neurodegenerative Diseases-Associated biomarkers: A review. Mol. Neurobiol. 59, 5935–5954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-022-02944-x (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Self- and interviewer-reported cognitive problems in relation to cognitive decline and dementia: results from two prospective studies. BMC Med. 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-03147-4 (2024).

Wilson, D. M. 3rd et al. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell 186, 693–714 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.032 (2023).

Gibson, A. A. et al. Oral health status and risk of incident diabetes: A prospective cohort study of 213,389 individuals aged 45 and over. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 202, 110821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110821 (2023).

Lee, J. E., Yang, S. W., Ju, Y. J., Ki, S. K. & Chun, K. H. Sleep-disordered breathing and alzheimer’s disease: A nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 273, 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.086 (2019).

Statistics, N. B. o. How is the economic zone divided into different divisions? https://www.stats.gov.cn/hd/lyzx/zxgk/202107/t20210730_1820095.html (2021).

Choi, J. W. & Han, E. Risk of new-onset depressive disorders after hearing impairment in adults: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 295, 113351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113351 (2021).

Zhu, F. X., Huang, J. Y., Ye, Z., Wen, Q. Q. & Wei, J. C. Risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a population-based cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 793–799. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217013 (2020).

Dioguardi, M. et al. The association between tooth loss and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis of case control studies. Dent. J. (Basel) 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/dj7020049 (2019).

Dominy, S. S. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in alzheimer’s disease brains: evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau3333 (2019).

Popovac, A. et al. Oral health status and nutritional habits as predictors for developing alzheimer’s disease. Med. Princ Pract. 30, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518258 (2021).

Tramonti Fantozzi, M. P. et al. The path from trigeminal asymmetry to cognitive impairment: a behavioral and molecular study. Sci. Rep. 11, 4744. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82265-6 (2021).

Luo, B., Pang, Q. & Jiang, Q. Tooth loss causes Spatial cognitive impairment in rats through decreased cerebral blood flow and increased glutamate. Arch. Oral Biol. 102, 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.05.004 (2019).

Lei, S. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis bacteremia increases the permeability of the blood-brain barrier via the Mfsd2a/Caveolin-1 mediated transcytosis pathway. Int. J. Oral Sci. 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-022-00215-y (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Tooth loss is associated with increased risk of dementia and with a Dose-Response relationship. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00415 (2018).

Dominy, S. S.et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Leveille, S. G. & Shi, L. Multiple chronic diseases associated with tooth loss among the US adult population. Front. Big Data 5, 932618. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2022.932618 (2022).

Hag Mohamed, S. & Sabbah, W. Is tooth loss associated with multiple chronic conditions? Acta Odontol. Scand. 81, 443–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016357.2023.2166986 (2023).

de la Fuente, A. G. et al. Novel therapeutic approaches to target neurodegeneration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 180, 1651–1673. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.16078 (2023).

Park, T. et al. More teeth and posterior balanced occlusion are a key determinant for cognitive function in the elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041996 (2021).

Yi-Chang, C., Shih-Han, W., Feng-Shiang, C. & Hsiao-Yun, H. Denture use mitigates the cognitive impact of tooth loss in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci., 1 (2024).

Steinmassl, P. A., Steinmassl, O., Kraus, G., Dumfahrt, H. & Grunert, I. Shortcomings of prosthodontic rehabilitation of patients living in long-term care facilities. J. Oral Rehabil. 43, 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12359 (2016).

Martelli, M. L. et al. Periodontal disease and women’s health. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 33, 1005–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2017.1297928 (2017).

Manly, J. J. et al. Endogenous Estrogen levels and alzheimer’s disease among postmenopausal women. Neurology 54, 833–837 (2000).

Nebel, R. A. et al. Understanding the impact of sex and gender in alzheimer’s disease: A call to action. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.008 (2018).

Bernabe, E. et al. Global, Regional, and National levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J. Dent. Res. 99, 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520908533 (2020).

Turnbull, N., Cherdsakul, P., Chanaboon, S., Hughes, D. & Tudpor, K. Tooth Loss, cognitive impairment and fall risk: A Cross-Sectional study of older adults in rural Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316015 (2022).

Crocombe, L. A. et al. Geographical variation in preventable hospital admissions for dental conditions: an Australia-wide analysis. Aust. J. Rural Health 27, 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12556 (2019).

Liu, M., Zhang, M., Zhou, J., Song, N. & Zhang, L. Research on the healthy life expectancy of older adult individuals in China based on intrinsic capacity health standards and social stratification analysis. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1303467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1303467 (2023).

Aquilanti, L. et al. Impact of elderly masticatory performance on nutritional status: an observational study. Med. (Kaunas) 56 https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina56030130 (2020).

Kip, E. & Parr-Brownlie, L. C. Healthy lifestyles and wellbeing reduce neuroinflammation and prevent neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1092537. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1092537 (2023).

Agyekum, F. et al. Behavioural and nutritional risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among the Ghanaian population- a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 24, 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17709-5 (2024).

Mudryj, A. N., Riediger, N. D. & Bombak, A. E. The relationships between health-related behaviours in the Canadian adult population. BMC Public. Health 19, 1359. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7674-4 (2019).

Sheridan, P. P.A. Obesity and microglial activation: potential for synergism in neurodegenerative diseases. FASEB J. 24, 326324–326324 (2010).

Brayne, C. et al. Education, the brain and dementia: neuroprotection or compensation? EClipSE collaborative members. Brain 133, 2210–2216. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq185 (2010).

Balow, B. & Blomquist, M. Young adults ten to fifteen years after severe reading disability. Element. School J. 66, 44–48 (1965).

Castro-Caldas, A., Reis, A. & Guerreiro, M. Neuropsychological aspects of illiteracy. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 7, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/713755546 (1997).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CHARLS database for providing this data. Thanks to all authors for their contributions to this study. Special thanks to Professor Qunhong.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.72361137562).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Q.K and W.M; data curation, W.Q.K and M.N; methodology, W.Q.K; resources, L.H and W.Q.H; software, W.Q.K and W.M, and W.K.X; supervision, W.Q.H, W.J, Z.X, Z.R.Q, W.Y.X; validation, W.P and W.Y.P, Y.T, G.Y.R; visualization, W.Q.K. Writing—original draft, W.Q.K and W.M, M.N; writing—review and editing, W.Q.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Declaration of Helsinki’s guiding principles were followed in the conduct of this investigation. The Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University approved the CHARLS (IRB00001052-11015), and all research participants signed an informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Wei, M., Meng, N. et al. Associations between edentulism and risk of neurodegenerative diseases among middle-aged and older adults in China: a decade-long cohort study. Sci Rep 16, 3931 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34017-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34017-z