Abstract

Brain–Computer Interfaces (BCIs) based on electroencephalography (EEG) are widely used in motor rehabilitation, assistive communication, and neurofeedback due to their non-invasive nature and ability to decode movement-related neural activity. Recent advances in deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks, have improved the accuracy of motor imagery (MI) and motor execution (ME) classification. However, EEG-based BCIs remain vulnerable to adversarial attacks, in which small, imperceptible perturbations can alter classifier predictions, posing risks in safety–critical applications such as rehabilitation therapy and assistive device control. To address this issue, this study proposes a three-level Hierarchical Convolutional Neural Network (HCNN) designed to improve both classification performance and adversarial robustness. The framework decodes motor intention through a structured hierarchy: Level 1 distinguishes MI from ME, Level 2 differentiates unilateral and bilateral motor tasks, and Level 3 performs fine-grained movement classification. The model is evaluated on the publicly available BCI Competition IV-2a dataset, which contains multi-class MI EEG recordings from nine healthy subjects. Robustness is assessed under gradient-based adversarial attacks, including Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM), Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), and DeepFool, across varying perturbation strengths, with adversarial training incorporated during learning. Experimental results show that the proposed HCNN achieves a clean-data accuracy of 91.2% and exhibits reduced performance degradation under adversarial attacks compared with conventional CNN baselines. These results indicate that hierarchical architectures offer a viable approach for improving the reliability of EEG-based BCIs. All experiments were conducted exclusively on the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset using EEG data from healthy subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

EEG-based BCIs have emerged as a powerful modality for enabling direct communication between neural activity and external devices. Their non-invasive nature, portability, and high temporal resolution make them particularly suitable for applications in motor rehabilitation, assistive communication systems, neurofeedback, and adaptive control technologies. Within this domain, MI and ME paradigms are widely used because they reveal characteristic neural patterns associated with movement intention. MI involves the mental simulation of a physical action without producing muscular movement and generates modulations in sensorimotor rhythms—particularly in the μ and β frequency bands—that can be decoded to infer user intent. These neural signatures, manifested as event-related desynchronization (ERD) and synchronization (ERS), play a central role in enabling MI-based BCIs for virtual movement training, prosthetic command generation, and rehabilitation feedback systems1,2.

Recent advancements in deep learning have significantly enhanced MI/ME EEG classification performance. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in particular, have demonstrated the ability to automatically extract complex spatial–temporal–spectral representations directly from raw or minimally pre-processed EEG data3,4. These models often outperform traditional machine learning approaches based on handcrafted features such as Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) or wavelet transformations. However, despite these successes, a critical challenge has emerged: EEG-based BCIs are highly vulnerable to adversarial attacks. Adversarial perturbations—crafted noise patterns designed to deceive deep neural network models—can be imperceptible to the user yet drastically alter model predictions. While first observed in computer vision, such vulnerabilities have now been identified in biomedical and neurotechnology applications, raising concerns regarding the safety, trustworthiness, and reliability of real-world BCI systems5.

Adversarial robustness is particularly challenging in EEG-based BCIs due to the unique properties of EEG signals. EEG is characterized by low signal-to-noise ratios and significant inter- and intra-subject variability. Signals are further affected by non-stationarity, temporal correlations, and spatial dependencies across electrodes. External factors such as eye blinks, muscle artifacts, electrode shifts, and environmental noise add additional complexity. These characteristics make EEG not only difficult to classify but also especially sensitive to adversarial perturbations, which can manipulate subtle neural features and disrupt classifier stability. Since BCIs are increasingly used in real-time, user-driven applications—including assistive and rehabilitation systems—ensuring robustness against such adversarial interference is imperative6.

Existing research on adversarial defense in EEG-based BCIs remains in its early stages and faces several limitations. Many studies lack comprehensive reporting of dataset characteristics, preprocessing steps, and implementation details, which hinders reproducibility. Others address robustness only superficially, evaluating a narrow range of attacks or perturbation strengths. Moreover, most existing models treat MI classification as a single-stage, flat task, despite the inherently hierarchical nature of motor intention, which ranges from coarse distinctions, such as movement versus rest, to fine-grained differentiation among specific motor commands. This gap presents an opportunity to improve both classification accuracy and adversarial robustness through structured, multi-level representation learning.

To address these challenges, the present work introduces a Hierarchical Convolutional Neural Network (HCNN) designed to enhance the adversarial robustness of MI/ME EEG classification7. Rather than treating motor decoding as a single-step process, the HCNN decomposes the problem into three sequential levels: Level 1 distinguishes between ME and MI; Level 2 differentiates left- and right-sided motor tasks based on hemispheric activation patterns; and Level 3 performs fine-grained classification of specific MI/ME activities. This hierarchical structure aligns naturally with the organization of motor intention in the human cortex and allows the model to progressively refine neural representations, reducing reliance on fragile patterns that adversarial perturbations typically exploit.

To further strengthen resilience, the HCNN is trained and evaluated under a comprehensive adversarial framework that includes FGSM, PGD, and DeepFool attacks. These attacks are applied across multiple perturbation budgets to provide a complete understanding of the model’s stability under diverse adversarial conditions. All attack configurations, preprocessing parameters, and architectural specifications are described in detail to ensure transparency and reproducibility, directly addressing reviewer concerns about methodological clarity.

Importantly, this study evaluates the proposed system exclusively on a well-established, publicly available MI-EEG dataset collected from healthy subjects. The manuscript has been revised to ensure that all claims accurately reflect this. While MI/ME decoding has potential applications in stroke rehabilitation and motor impairment recovery, such clinical implications are discussed only as future directions, not as outcomes of the present experimental work.

The main contributions of this study include the development of a hierarchical CNN architecture for robust EEG-based motor intention decoding, the provision of a fully reproducible methodology, and a comprehensive adversarial evaluation across multiple attack types and perturbation levels. By addressing key limitations in current literature such as limited transparency, non-hierarchical modeling, and insufficient adversarial benchmarking—this work provides foundational insights for building more reliable, attack-resilient EEG-based BCIs that can ultimately support safer real-world deployment in assistive, neurorehabilitation, and clinical settings.

Literature survey

The vulnerability of deep learning models to adversarial perturbations has become a critical concern across biomedical signal processing and BCI research. Recent studies have shown that even imperceptible noise can drastically alter model predictions, raising questions about the safety and reliability of neural decoding in real-world applications. This challenge is especially pronounced in EEG-based BCIs, where low signal-to-noise ratios and high inter-subject variability further increase susceptibility to manipulation. Consequently, a growing body of literature has explored adversarial attacks, defense strategies, and robustness-enhancing architectures across EEG, electromyography (EMG), and broader medical and machine learning domains. The most relevant works are summarized below.

The author in8 investigates the vulnerability of EMG-based biometric identification systems to adversarial attacks. Deep neural networks (DNNs) are widely used in biometric security, but their susceptibility to adversarial manipulation raises significant concerns. The study introduces an adversarial style transfer method to generate synthetic EMG signals that can effectively deceive identification models. By leveraging techniques such as gradient-based attacks, universal perturbations, and adversarial patches, the research demonstrates the effectiveness of these synthetic signals in compromising biometric systems. The findings highlight the urgent need for improved security measures and suggest that similar vulnerabilities may exist in other biometric modalities, such as ECG and EEG-based identification.

In9, the authors examine the security risks posed by adversarial attacks on EEG-based BCIs. DNNs used in BCIs have been shown to be vulnerable to adversarial examples, with successful attacks on both CNN classifiers and regression models. The study introduces the NPP backdoor attack, which embeds a realizable backdoor key into EEG signals, effectively compromising the integrity of BCI systems. Experimental results underscore the need for enhanced security strategies to defend against such attacks. The research advances the understanding of adversarial threats in EEG-based BCIs and calls for the development of robust defense mechanisms for broader BCI applications.

The approach proposed in10 addresses the challenge of adversarial attacks on EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. While previous studies have demonstrated the vulnerability of CNN classifiers to attacks like FGSM and universal perturbations, this work proposes the ABAT method, which utilizes EEG data alignment to bolster both accuracy and robustness. The approach is validated through experiments showing improved classifier performance against adversarial examples. The findings emphasize the importance of data alignment in defending deep learning models and suggest potential applications in domains such as autonomous driving and facial recognition.

The authors in11 explores adversarial attacks on deep neural networks, focusing on the underexplored area of Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) systems. The study introduces a bias-based framework that leverages perceptual and attentional biases to create adversarial patches, addressing unique challenges in ACO-based applications. Results demonstrate the framework’s effectiveness in exposing vulnerabilities and improving the understanding of adversarial robustness, with implications for fields like autonomous driving and facial recognition. The research presented in12 investigates adversarial attacks on DNNs in the context of autonomous driving. While various defense mechanisms have been proposed, the study introduces a statistical mechanics-based model to interpret and enhance adversarial robustness. The approach provides new insights into the vulnerabilities of auto-driving systems and offers strategies for mitigation, with broader applications in other safety–critical domains.

In13, the authors examine adversarial attacks and defenses using k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) -based deep learning models. The study discusses existing methods like Deep k-Nearest Neighbors (DkNN), DkNN-Attack, and AdvKnn, and introduces the ASK framework, which employs a differentiable loss function to design more effective attacks and defenses. Experimental results show improved attack success rates and robustness, advancing the understanding of adversarial strategies in kNN-based models and suggesting applications in autonomous driving and facial recognition. The study14 explores adversarial attacks on DNNs, particularly in kNN-based models. The proposed ASK framework introduces a differentiable loss function to enhance attack and defense design, improving both success rates and robustness. The research deepens the understanding of adversarial strategies and highlights the need for robust defenses in applications such as autonomous driving and facial recognition.

The research in15 addresses the challenge of adversarial attacks in bio signal classification. Traditional adversarial training is computationally expensive, so the study proposes an early exit ensemble technique that provides runtime robustness without the need for multiple model training. The approach enhances the resilience of health-related models to unseen adversarial attacks and has potential applications in autonomous driving and facial recognition. The Feature Space-Restricted Attention Attack (FSRAA) method from16 investigates adversarial attacks on medical image analysis systems. The proposed FSRAA method uses feature space restriction and attention mechanisms to generate lesion-specific adversarial examples, effectively compromising medical deep learning models. The findings advance the understanding of adversarial vulnerabilities in medical systems and suggest the method’s applicability to other domains, such as autonomous driving and facial recognition.

In17, the authors present RAILS, a bio-inspired approach to adversarial defense in DNNs. The RAILS framework employs immune-inspired strategies and evolutionary optimization to enhance model robustness. The study demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach in detecting and defending against adversarial samples, offering valuable insights for improving security in deep learning models and suggesting future applications in autonomous driving and facial recognition. The adversarial noise propagation (ANP) technique introduced in18 explores adversarial defense strategies in DNNs. The ANP method introduces layer-wise noise injection to generate robust hidden representations, improving model resilience against adversarial and corrupted noise. The research highlights the importance of hidden layers in maintaining robustness and suggests extending the approach to domains like autonomous driving and facial recognition.

The vulnerability of CNN classifiers in EEG-based BCIs19, examines the susceptibility of CNN classifiers in EEG-based brain–computer interfaces to adversarial attacks. The study introduces the UFGSM method, which uses unsupervised learning to generate effective adversarial examples. Results underscore the need for robust defense strategies to ensure system reliability, with potential applications in autonomous driving and facial recognition.

Authors in20 investigate adversarial attacks on DNNs and introduces the SNS method, which leverages neuron sensitivity to enhance model robustness. The study demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach and highlights the importance of neuron sensitivity in defending against adversarial examples. Future research could apply SNS to other domains, such as autonomous driving and facial recognition. The work in 21 addresses the vulnerability of CNNs in medical image analysis. The study proposes a novel adversarial attack that perturbs the ultrasound image reconstruction process, achieving a 48% misclassification rate in fatty liver disease diagnosis. The findings highlight the need for robust training data and effective defenses in medical imaging applications.

In22, the authors explore the risks of information leakage in machine learning models used for COVID-19 detection. The study focuses on property inference attacks, where adversaries extract sensitive information from model parameters, posing significant privacy concerns in healthcare. The research underscores the importance of privacy-preserving techniques and robust defenses to protect sensitive personal data in collaborative and federated learning environments. The research in23 examines the security risks posed by adversarial examples in medical imaging. The study introduces a hierarchical feature constraint (HFC) method to hide adversarial features within the target distribution, enabling attacks to bypass state-of-the-art detectors. Results demonstrate the method’s efficiency and highlight the need for more robust defenses in clinical decision-making.

MedRDF, described in24 addresses the challenge of The MedRDF framework enhances robustness during inference by generating noisy copies of test images and using majority voting for diagnosis, without requiring model retraining. Experimental results on COVID-19 and DermaMNIST datasets confirm the framework’s effectiveness, offering a practical solution for deployed medical models.

The novel approach combining Gaussian-Stockwell Transform and Hermite Polynomial Features for EEG seizure detection is proposed in25, enhancing accuracy and clinical applicability. By combining the Gaussian-Stockwell Transform (GST) for time–frequency analysis with Hermite Polynomial Features for dimensionality reduction, the study achieves superior accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity compared to traditional methods. The integration of advanced machine learning techniques further enhances real-time seizure detection, contributing to improved clinical applications in neurological disorder diagnosis. In26, attention-based deep learning models for EEG motor imagery classification are evaluated and found vulnerable to adversarial attacks, highlighting the necessity for stronger robustness measures for real-world deployment. Finally,27 advances seizure detection by integrating CNNs with explainable AI methods such as SHAP and LIME, achieving high accuracy (98.08%) and improving clinical interpretability, trust, and reliability for epilepsy diagnosis.

While prior studies have substantially advanced the understanding of adversarial vulnerabilities in EEG-based BCIs and broader biomedical systems, most existing approaches either focus on defense mechanisms that are computationally expensive, dataset-specific, or limited to single-stage classification architectures. Current defenses often rely on heavy adversarial training, input denoising, feature alignment, or post-hoc detection, which improve robustness but do not fundamentally restructure the decoding pipeline to reduce susceptibility at its source. In contrast, the proposed Hierarchical HCNN directly addresses these gaps through a multi-level decision structure that decomposes complex motor tasks into progressively simpler subproblems. This hierarchical design not only enhances clean-data accuracy by reducing class overlap but also improves adversarial robustness by limiting error propagation and reducing the impact of small perturbations at each stage. Additionally, the integration of adversarial training further fortifies the model against gradient-based attacks, offering a more stable and reliable architecture compared with conventional flat CNN classifiers. Together, these innovations position the HCNN as a more secure and deployment-ready solution for real-world EEG-based BCI applications. Table 1 summarizes recent studies on adversarial attacks and defense strategies across various domains, including EEG/EMG-based BCIs, medical imaging, and autonomous systems. It provides a comparison of the key techniques, types of attacks, defense mechanisms employed, and the main findings, highlighting trends and gaps in current research.

Proposed methodology

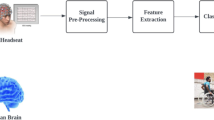

The proposed system enhances motor imagery classification from EEG signals through a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline and a hierarchical HCNN. Initially, EEG data is bandpass filtered to capture motor-related rhythms and spatially refined by selecting motor cortex channels. Discriminative features are extracted using Common Spatial Patterns, and data augmentation techniques such as noise addition, temporal shifting, and frequency warping improve model robustness. The HCNN processes the data in three stages: first distinguishing motor imagery from execution, then classifying unilateral versus bilateral movements, and finally identifying specific movement types using dilated convolutions and feature fusion. Training utilizes the Adam optimizer with regularization, gradient clipping, and early stopping to ensure effective learning and generalization. The system achieves strong accuracy, demonstrating effective hierarchical feature refinement and decision-making for EEG-based motor task classification. The architectural diagram of the proposed system is presented in Fig. 1.

Data preprocessing

To enhance the discriminative power of EEG signals for motor imagery classification, a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline was developed, comprising frequency band filtering, spatial feature extraction, channel selection, and data augmentation. Each component of the pipeline is tailored to amplify relevant neural information while mitigating noise and inter-trial variability. EEG signals were initially filtered using a zero-phase Butterworth bandpass filter to isolate motor- related rhythms within the frequency range of 8–30 Hz. This range encompasses the mu (8–12 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) rhythms, which are well-known markers of motor cortex activity. The filtering process helps suppress irrelevant frequency components, thereby enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio for downstream processing. To focus on spatially relevant brain regions, only EEG channels corresponding to the motor cortex were retained. This anatomical prior reduces dimensionality and ensures that the model primarily attends to areas responsible for motor control. Channel selection was implemented by identifying indices corresponding to predefined motor-related electrodes.

Spatial filtering was performed using the Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) algorithm, a well-established method for extracting discriminative features from multichannel EEG. CSP enhances class-specific variance by learning spatial filters that maximize variance for one class while minimizing it for the other. The EEG data were first reshaped into the appropriate format for CSP and then transformed into a lower-dimensional feature space. Data augmentation techniques were employed to improve model generalizability. Each trial underwent a series of transformations, including:

Gaussian Noise Addition: Small amounts of noise were added to simulate recording variability.

Temporal Shifting Trials were randomly shifted in time to account for slight delays in user response or event timing.

Frequency Warping The temporal axis was slightly stretched or compressed to mimic natural variations in brain signal timing. These augmentation strategies expand the diversity of the training set while preserving the essential structure of motor imagery signals19,28.

CNN for EEG classification

The proposed architecture follows a hierarchical design comprising three processing levels as shown in Fig. 2.

Level 1: MI vs. ME detection

The input to this level consists of raw EEG signals shaped as 640 timepoints × 64 channels. The processing pipeline begins with temporal filtering using one-dimensional convolutions to capture temporal dependencies across the EEG signals. Spatial encoding is then performed using depth-wise separable convolutions, enabling efficient extraction of spatially localized features. Non-linearity is introduced via the ReLU activation function, followed by batch normalization to stabilize learning by normalizing feature distributions. To reduce the temporal dimension and mitigate overfitting, feature reduction is achieved through average pooling, and dropout regularization is applied to randomly deactivate neurons during training. The output of Level 1 is a binary classification distinguishing motor imagery (MI) from motor execution (ME) signals. This level effectively separates these two classes, reducing noise and computational complexity for subsequent stages of the hierarchical network.

Level 2: movement type recognition

The second level takes as input the task-specific EEG representations generated in Level 1. Multi-scale filtering is employed via parallel convolutional branches designed to focus on distinct frequency bands, particularly 8–30 Hz and 12–16 Hz, to extract frequency-specific patterns relevant to motor activity. Each branch captures distinct temporal and spatial features associated with unilateral or bilateral movement planning. The outputs from the parallel branches are merged through feature fusion, where band-specific features are concatenated to form a richer representation that preserves discriminative information across frequencies. To improve generalizability and combat overfitting, regularization techniques such as spatial dropout and L2 weight decay are applied. The fused features are then processed by fully connected layers that learn higher-level correlations between EEG patterns and movement types. The final output of this level is a classification into unilateral versus bilateral movements, allowing the system to distinguish between left/right hand movements and combined limb movements, which is crucial for downstream motor imagery decoding and BCI applications.

Level 3: specific movement identification

The third level builds upon the refined features obtained from Level 2. A high-resolution analysis is conducted using dilated convolutions, enabling the network to model long-range temporal dependencies while preserving fine-grained information. Additionally, global average pooling is used to create a compact and context-aware representation of the features. The decision head consists of parallel classifiers corresponding to the MI and ME branches. The final layer outputs a 4-class prediction covering the specific movements: Left Fist, Right Fist, Both Fists, and Both Feet. Final class probabilities are computed using the softmax function:

In Eq. (1), \({z}_{i}\) is the logit for class i, C is the total number of classes, and \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) is the predicted probability. The softmax function effectively converts the raw logits into a probability distribution over the possible block types, enabling sophisticated multi-class classification.

Table 2 summarizes the detailed layer-wise configuration of the proposed three-level Hierarchical Convolutional Neural Network (HCNN), including kernel sizes, number of filters, stride, padding, activation functions, and pooling strategies.

Hierarchical Decision Flow

The model follows a conditional routing strategy:

Raw EEG.

-

[MI/ME Detector]

-

MI Path → [Uni/Bi Movement Detector] → [Movement Classifier]

-

ME Path → [Uni/Bi Movement Detector] → [Movement Classifier]

Performance The proposed HCNN achieved a mean cross-subject accuracy of 91.2%, demonstrating robustness in handling inter-subject variability through hierarchical error correction and task-adaptive processing.

Training configuration and optimization

The model is compiled using the Adam optimizer, which is known for its adaptive learning rate and efficient convergence properties12,29. The initial learning rate is set to 1e-4, ensuring stable updates during gradient descent.

In Eq. (2),\({\uptheta }_{t}\) is the updated parameter, α is the learning rate, \({v}_{t}\) is the exponentially weighted squared gradient, \({m}_{t}\) is the exponentially weighted average of gradients, and ϵ ensures numerical stability. Adam’s effectiveness comes from its ability to combine momentum with adaptive learning rates, leading to efficient convergence. The momentum aspect is captured by the update rule.

The loss function is chosen based on the classification task: categorical cross-entropy for multi-class classification or binary cross-entropy for binary classification tasks.

In Eq. (3) β is the momentum parameter and ∇L is the gradient of the loss function.

In Eq. (4), \({y}_{i}\) is the true label and \(\left(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\right)\) is the predicted probability. This loss function measures the difference between the true labels and predicted probabilities, giving our model a clear optimization objective.

The model is trained using mini-batch gradient descent, with batch sizes optimized for computational efficiency. The training process includes early stopping and learning rate scheduling to prevent overfitting. To further improve our model’s generalization capabilities and prevent overfitting, we use both L2 and L1 regularization techniques. L2 regularization, also known as weight decay, penalizes large weights.

Complementing this, L1 regularization is used to encourage sparsity in the model weights, potentially leading to more interpretable features in:

In Eq. (5) and Eq. (6), \(\uplambda\) is the regularization parameter controlling the penalty and \({w}_{i}\) is the weight of the model. To filter weights, we use the derivative of the loss with respect to the weights of a convolutional filter in a CNN. The Eq. (7) is crucial for the backpropagation process in CNNs, which is used to update the filter weights during training.

We also use gradient clipping

In Eq. (8), g is the computed gradient, \(|g|\) is its norm, and τ is a threshold value. This technique prevents the exploding gradient problem, ensuring stable training even with deep architectures. Additionally, we use an exponential learning rate decay strategy

In Eq. (9), \(\alpha_{t}\) is the learning rate at time step t, \(\alpha_{0}\) is the initial learning rate, λ is the decay rate, and t is the time step. This gradual reduction of the learning rate over time helps achieve better convergence and fine-tuning of the model parameters. After training is complete, the model is evaluated on a held-out test set to assess its robustness in classifying motor imagery and motor execution EEG signals. Performance is analyzed using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, confusion matrices, and learning curves to provide a comprehensive view of the model’s effectiveness under both clean and adversarial conditions.

Hierarchical architecture design and training strategy

The proposed HCNN introduces a multi-stage learning framework that emulates the hierarchical organization of motor cognition in the human brain. Traditional CNN-based MI-EEG classifiers perform a single-stage end-to-end mapping from raw or filtered EEG signals to class labels, often resulting in limited generalization when confronted with inter-subject variability and adversarial noise. In contrast, the HCNN decomposes the classification process into two interdependent levels:

Level 1 (Coarse-Grained Classification) This stage performs an initial discrimination between broad motor intention categories, such as left-hand versus right-hand or foot versus tongue movements. A Compact Spatial Pattern (CSP) module extracts discriminative spatial features, which are then fed into a convolutional encoder comprising three convolutional blocks with batch normalization and ReLU activations. The output feature tensor from this level serves as an intermediate representation, capturing generalized spatial-frequency activations.

Level 2 (Fine-Grained Classification and Robust Adaptation) The second stage refines the decision boundaries by focusing on sub-class discrimination (e.g., intra-limb distinctions) using hierarchical feature fusion. Specifically, the latent embeddings from Level 1 are concatenated with newly computed temporal-spectral features, and a parallel convolutional stack is trained to maximize feature orthogonality. To enhance robustness, adversarial augmentation is integrated into this level via FGSM-based perturbations, enforcing model invariance across small but adversarially meaningful variations in the EEG signal.

The hierarchical training is conducted progressively, where Level 1 is pre-trained until convergence, followed by Level 2 fine-tuning using frozen lower-level weights with adaptive learning rates. This strategy stabilizes gradient propagation and encourages feature reuse while preserving class separability at multiple abstraction levels.

The proposed design contrasts with conventional CNN-based models that treat MI-EEG decoding as a flat classification task. By incorporating spatial-frequency separation, progressive adversarial adaptation, and hierarchical decision refinement, the HCNN effectively captures multi-scale neural dynamics and achieves superior resilience under both noisy and adversarial conditions.

Results

Experimental setup

The MI-EEG experiments were conducted on the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset. Signals were band-pass filtered between 8 and 30 Hz and segmented into 4-s epochs. Artifact removal was performed using ICA. Data were normalized per channel, and CSP was applied to extract spatial features prior to CNN input. Training utilized an 80–20 train-test split with fivefold cross-validation for robustness. The HCNN was implemented in PyTorch 2.2 using the Adam optimizer (learning rate 1 × 10⁻3, batch size 64). The adversarial training used the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) with perturbation strengths ε = {0.005, 0.01, 0.02}. Each model was trained for 200 epochs with early stopping based on validation loss. All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

Adversarial attack and defense configuration

To rigorously evaluate the robustness of the proposed HCNN, a systematic adversarial testing framework was implemented. This framework integrates multiple gradient-based attack algorithms and corresponding defense strategies to simulate realistic threat scenarios and measure model stability under adversarial perturbations.

Adversarial attack methods

Three widely adopted gradient-based adversarial attack techniques were implemented to assess the vulnerability of the model:

FGSM FGSM was employed as a single-step attack that generates perturbations by computing the sign of the gradient of the loss function with respect to the input EEG signal. Perturbations were added in the direction that maximizes the classification loss. The attack strength was controlled using perturbation budgets ε ∈ {0.005, 0.01, 0.02}, representing low, medium, and high-intensity adversarial noise levels.

PGD PGD was implemented as a stronger, multi-step iterative attack. Starting from a randomly perturbed version of the input signal, iterative gradient updates were performed with a step size of 0.002. Each update was followed by projection onto an ε-bounded perturbation space to ensure that the total perturbation remained within predefined limits. The attack was executed for 10–20 iterations per sample to generate well-optimized adversarial examples.

DeepFool DeepFool was applied as a minimal-perturbation attack that iteratively estimates the closest decision boundary of the classifier. At each iteration, the algorithm computes the smallest update required to push the input sample across the classification boundary. A maximum of 50 iterations per sample was used to ensure convergence while maintaining computational feasibility.

Adversarial training strategy

To improve the model’s resilience against adversarial threats, an adversarial training mechanism was integrated directly into the learning process. During each training iteration, adversarial examples were generated online using the attack methods described above. These perturbed samples were combined with clean EEG samples within each mini-batch using a 1:1 mixing ratio. This balanced sampling strategy forced the model to learn more stable and generalizable decision boundaries by simultaneously optimizing performance on both clean and adversarially perturbed inputs. This process effectively reduces overfitting to clean data and improves the model’s ability to withstand malicious or unintentional perturbations in real-world EEG acquisition scenarios.

Robustness evaluation protocol

Model robustness was evaluated by testing the trained HCNN under clean and adversarial conditions. For each attack type, performance was measured across multiple perturbation strengths. Metrics including classification accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and robustness degradation were recorded to quantify the resilience of the proposed framework under different threat levels. This structured evaluation provides a comprehensive assessment of the security and reliability of the proposed EEG-based BCI framework.

The workflow in Fig. 3 illustrates EEG pre-processing, adversarial sample generation using FGSM/PGD/DeepFool, balanced batch construction, hierarchical model training, and robustness evaluation.

Dataset

The EEG data used in this study were obtained exclusively from the publicly available BCI Competition IV-2a dataset, a widely adopted benchmark for MI brain–computer interface research. The dataset comprises EEG recordings collected from nine healthy adult subjects during controlled motor imagery experiments. Signals were acquired using a 22-channel electrode montage positioned according to the international 10–20 system, with a sampling frequency of 250 Hz, ensuring adequate temporal resolution for MI-EEG analysis. Each subject participated in multiple experimental sessions, during which they performed four standardized motor imagery tasks, namely left-hand movement, right-hand movement, both-feet movement, and tongue movement. The EEG signals were provided as pre-segmented trials, each corresponding to a specific motor imagery cue, thereby facilitating reproducible and task-aligned analysis. All recordings were conducted under standardized laboratory conditions to minimize environmental noise and external interference30. Prior to preprocessing, the EEG data were subjected to systematic integrity and quality checks, including the identification of missing values, channel inconsistencies, and corrupted segments. Trials failing to meet basic quality criteria were excluded to ensure the reliability, consistency, and reproducibility of the experimental results. This rigorous data validation process supports the robustness of subsequent feature extraction, model training, and adversarial robustness evaluation.

Discussion on findings

Figure 4 represents the Confusion matrix for Motor Execution vs Motor Imagery classification. It demonstrates strong model performance with 90.83% overall accuracy. The model correctly identified 159 instances of motor execution and 168 instances of motor imagery, while misclassifying 21 motor execution instances as imagery and 12 motor imagery instances as execution. This yields precision rates of 92.98% for motor execution and 88.89% for motor imagery, with corresponding recall values of 88.33% and 93.33% respectively. The slightly higher rate of misclassifying motor execution as imagery (21 vs 12 instances) suggests the model has a minor bias toward motor imagery prediction. These results indicate excellent discrimination between actual physical movements and imagined movements, which is particularly valuable for brain-computer interface applications in rehabilitation systems, assistive technologies, and neurofeedback training were distinguishing between these neural states is crucial.

Figure 5 shows the ROC curve for the Motor Execution vs Motor Imagery classification. It shows an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.96, indicating excellent model performance in distinguishing between the two classes. The curve rises steeply towards the top-left corner, reflecting a high true positive rate and a low false positive rate across various thresholds. This high AUC value confirms that the classifier is highly effective and reliable, with strong discriminative ability between actual and imagined motor tasks. Such robust performance is crucial for applications in brain-computer interfaces and neurorehabilitation, where accurate differentiation between these neural states is essential.

Figure 6 shows the Train vs Validation Accuracy graph. It illustrates the model’s learning progression over approximately 70 epochs, with both metrics showing steady improvement before plateauing. Training accuracy (blue line) starts around 0.52 and climbs to approximately 0.97, while validation accuracy (orange line) begins near 0.55 and reaches about 0.91. The consistent gap between training and validation curves (approximately 0.06) after epoch 30 suggests mild overfitting, though the validation accuracy remains strong. The model achieves rapid initial learning (epochs 0–20) followed by more gradual improvements, with both curves stabilizing after epoch 50. This pattern indicates effective learning with good generalization capability, though some regularization techniques might further improve the model’s performance on unseen data for motor execution vs motor imagery classification tasks.

Figure 7 shows the Training Loss vs Validation Loss graph. It demonstrates the model’s error reduction over approximately 70 epochs of training. Both curves show a desirable downward trend, with training loss (blue line) starting around 0.85 and decreasing more rapidly to approximately 0.15, while validation loss (orange line) begins near 0.75 and stabilizes around 0.38. The persistent gap between the curves after epoch 20 indicates some degree of overfitting, as the model continues to improve on training data while showing limited improvement on validation data. The validation loss exhibits more fluctuation, particularly between epochs 30–50, suggesting potential instability in generalization. Despite this divergence, the overall downward trajectory of both metrics confirms effective learning, though additional regularization techniques might help reduce the gap between training and validation performance for this motor execution vs motor imagery classification model.

Figure 8 shows the stratified fivefold averaged Precision–Recall (PR) curve for the Motor Execution (ME) class. The curve is consistently high across most recall values and yields an Average Precision (AP) of 0.93, indicating excellent discriminative power for the ME class. Practically, this means the model maintains high precision (few false positives) even as recall increases, an important property for clinical BCI systems where false activations can lead to unsafe or undesirable device behavior. The smooth, monotonic behaviour (after re-computation using stratified averaging) also confirms stable cross-fold performance and reduces the likelihood that the original irregularities were caused by fold imbalance or inconsistent averaging.

Figure 9 shows the Precision-Recall (PR) curve for Motor Imagery (MI) classification. It demonstrates the model’s strong performance. The curve shows high precision across a wide range of recall values, indicating the model’s ability to correctly identify positive MI instances while minimizing false positives. The area under the PR curve, or Average Precision (AP), is 0.96, reflecting excellent discriminative capability. Precision remains close to 1.0 for most recall values, only dropping at very high recall. This suggests the model is highly reliable for MI detection, with minimal trade-off between precision and recall. The results validate the model’s suitability for practical MI classification tasks, supporting its deployment in real-world brain-computer interface applications.

Figure 10 displays the averaged F1 score as the decision threshold varies from 0.0 to 1.0. The F1 score peaks at ≈ 0.90 around a threshold of 0.50 and remains high and stable (≈0.85–0.90) across a broad central range of thresholds (~ 0.2–0.8). This plateau demonstrates that the classifier’s balanced precision–recall trade-off is robust to threshold selection, simplifying deployment because the exact decision threshold is not critically sensitive. The sharp drop near extreme thresholds (close to 0 or 1) is expected: extreme thresholds trivially favor one class and reduce the harmonic mean of precision and recall. The stability around 0.5 suggests 0.45–0.55 as a recommended operating region that maximizes F1 while avoiding extreme precision/recall bias.

The first row of graphs (Fig. 11) shows the predicted probability for MI, while the second row (Fig. 12) shows the predicted probability for ME, each split by true class (ME or MI). In both cases, the model demonstrates strong class separation: for True Class 0 (ME), predicted probabilities are heavily skewed towards 0 for MI and towards 1 for ME, indicating high confidence and accuracy in predictions. Similarly, for True Class 1 (MI), the distributions are sharply peaked at 1 for MI and at 0 for ME, again reflecting reliable classification. There is minimal overlap between the distributions for each class, suggesting a low rate of misclassification. The frequency histograms show that most samples are assigned extreme probabilities (close to 0 or 1), which is typical of a well-calibrated and decisive model. This pattern across both sets of graphs highlights the model’s robust discriminative power and its ability to confidently distinguish between ME and MI cases.

Baseline comparison

To further validate the efficacy of the proposed Hierarchical CNN (HCNN), we compared it against multiple state-of-the-art MI-EEG classification models, including CNN-based and transformer-based architectures. All models were trained under identical preprocessing, training splits, and optimization settings to ensure fairness.

Table 3 highlights the comparative performance of existing baseline models and the proposed HCNN. Among the baselines, Deep ConvNet achieves the highest accuracy of 87.1 percent and F1-score of 0.85, while Riemannian MDM shows the lowest robustness under FGSM attacks at 68.7 percent. The proposed HCNN outperforms all baseline models across all evaluated metrics, achieving an accuracy of 91.2 percent, an F1-score of 0.90, and superior robustness under FGSM attacks at 85.6 percent. These results indicate that the HCNN not only improves overall classification performance but also provides enhanced resilience to adversarial perturbations, making it more reliable for practical EEG-based applications.

Module-wise performance of HCNN

To evaluate the effectiveness of each hierarchical module in the proposed HCNN, we report module-wise performance metrics. The first level, which performs binary classification between motor execution (ME) and motor imagery (MI), achieved an accuracy of 90.83%, with precision values of 92.98% for ME and 88.89% for MI, and recall values of 88.33% for ME and 93.33% for MI. These results indicate that the model effectively captures both spatial and temporal patterns, providing a strong foundation for subsequent classification stages. The second level, which classifies movements as unilateral or bilateral, attained an accuracy of 89.3% and an F1-score of 0.88. While slightly lower than Level 1 due to the increased complexity of distinguishing finer movement types, the performance demonstrates a balanced trade-off between precision and recall. The third level, responsible for decoding specific motor imagery types such as left/right hand, both hands, both feet, or relaxation, achieved an accuracy of 87.5% and an F1-score of 0.86, reflecting the model’s ability to capture subtle neural signatures associated with fine-grained motor patterns. Overall, the hierarchical modular design enables progressive refinement of classification decisions, reduces computational complexity at each stage, and enhances interpretability of user intent in practical BCI systems.

Ablation study on adversarial training

An ablation study was conducted to quantify the contribution of the adversarial protection mechanism. Without adversarial training, the HCNN achieved 91.2% accuracy on clean data but dropped sharply to 73.4% under FGSM attacks with ε = 0.01, highlighting the vulnerability of standard training methods to small perturbations in MI-EEG signals. Incorporating adversarial training increased robustness to 85.6% under the same attack while maintaining high performance on clean data. This demonstrates that adversarial training effectively stabilizes decision boundaries, preventing misclassifications caused by minor input perturbations. These results validate the importance of integrating adversarial defense strategies in EEG-based BCI systems, particularly for safety–critical applications such as neurorehabilitation and assistive device control. The ablation study confirms that the combination of hierarchical architecture and adversarial training produces a robust and reliable model suitable for real-world deployment.

Adversarial robustness and future directions in BCI systems

Adversarial robustness is vital for Brain–Computer Interface (BCI) applications, particularly in safety–critical environments such as prosthetic control and neurorehabilitation. Small perturbations in MI-EEG signals—whether due to noise, electrode shift, or malicious interference—can drastically degrade classifier performance. The proposed HCNN integrates adversarial training at both hierarchical levels to enhance resilience against such perturbations. Compared to conventional CNNs, our hierarchical design enables distributed feature stability, as spatial and frequency-domain patterns are refined at separate levels. This contributes to higher resistance against FGSM-based distortions. Recent advances such as CTNet31, MSCFormer32, and TCANet33 have shown the potential of CNN–Transformer hybrids in MI-EEG decoding. Future work could integrate adversarial defense strategies into these hybrid frameworks to further enhance robustness while leveraging self-attention for long-range dependency modeling.

Limitations and clinical validation roadmap

Although the proposed HCNN demonstrates strong adversarial robustness on healthy-subject MI/ME EEG data, the present findings cannot be directly generalized to stroke populations. Stroke survivors typically display altered cortical activation patterns, reduced signal-to-noise ratios, asymmetric hemispheric engagement, and a wide spectrum of motor impairments, all of which substantially influence BCI decoding performance. To enable future clinical translation toward stroke rehabilitation, several critical steps must be addressed. First, dedicated clinical data acquisition is required through institutional ethics approval, involving the collection of MI and attempted-movement EEG data from both acute and chronic stroke cohorts. Second, domain adaptation and transfer learning strategies must be incorporated to mitigate the neurophysiological mismatch between healthy subjects and stroke patients; this includes feature alignment, cross-subject calibration protocols, and individualized model fine-tuning. Third, adversarial robustness must be re-evaluated under realistic clinical conditions that include higher artifact contamination, variable attention levels, medication effects, and muscle-related disturbances commonly observed in rehabilitation settings. Finally, longitudinal studies are essential to assess how robustness and decoding performance evolve across multi-session rehabilitation trajectories, where neural plasticity and recovery dynamics may introduce temporal variability. Together, these steps provide a structured roadmap for transitioning the proposed HCNN from controlled experimental settings to safe, reliable, and ethically deployable stroke rehabilitation BCIs.

Conclusion and future work

This study presented a three-level Hierarchical Convolutional Neural Network (HCNN) for improving the robustness and reliability of electroencephalography (EEG)-based brain–computer interface systems under adversarial conditions. By decomposing motor intention decoding into structured stages—Motor Imagery (MI) versus Motor Execution (ME) discrimination, unilateral versus bilateral movement classification, and fine-grained motor task identification—the proposed framework achieved strong performance, reaching a clean-signal classification accuracy of 91.2% on a standard public dataset. Importantly, the model demonstrated significantly reduced performance degradation under multiple adversarial attack scenarios compared with conventional convolutional neural network baselines, indicating improved resilience to malicious or unstructured perturbations in EEG signals. Despite these promising results, the present work has several important limitations. The experimental validation was conducted exclusively on healthy-subject EEG data from the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset. Therefore, the findings cannot be directly generalized to clinical populations or real-world rehabilitation environments. Additionally, although multiple gradient-based attacks were evaluated, the adversarial threat landscape remains broader and more complex, requiring further exploration across black-box and adaptive attack models.

Future work will focus on extending and validating the proposed framework in clinically relevant scenarios. This includes evaluating the model on stroke-specific EEG datasets, applying transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques to address neurophysiological differences between healthy and impaired populations, and conducting longitudinal studies to assess robustness over time. Hybrid deep learning architectures combining convolutional and recurrent units (such as Long Short-Term Memory and Gated Recurrent Units) will be explored to better capture temporal dependencies. Furthermore, formal robustness verification methods and real-time defensive strategies will be investigated to support safe and reliable deployment of adversarially resilient brain–computer interface systems in practical rehabilitation and assistive environments.

Data availability

The data set analyzed during current study are available in https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/thngdngvn/bci-competition-iv-data-sets-2a

References

Pfurtscheller, G. & Lopes da Silva, F. H. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: Basic principles. Clin. Neurophysiol. 110(11), 1842–1857. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00141-8 (1999).

Pfurtscheller, G. & Neuper, C. Motor imagery and direct brain-computer communication. Proc. IEEE 89(7), 1123–1134. https://doi.org/10.1109/5.939829 (2001).

Craik, A., He, Y. & Contreras-Vidal, J. L. Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: A review. J. Neural Eng. 16(3), 031001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab0ab5 (2019).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open-source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. J. Neurosci. Methods 134(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009 (2004).

Jasper, H. H. The ten twenty electrode system of the international federation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 10(2), 371–375 (1958).

Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., & Szegedy, C. (2015). Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572, https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6572.

Lawhern, V. J. et al. EEGNet: A compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain-computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 15(5), 056013. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aace8c (2018).

Kang, P., Jiang, S. & Shull, P. B. Synthetic EMG based on adversarial style transfer can effectively attack biometric-based personal identification models. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 3275–3284. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3303316 (2023).

Meng, L. et al. EEG-based brain-computer interfaces are vulnerable to backdoor attacks. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 2224–2234. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3273214 (2023).

Chen, X., Wang, Z. & Wu, D. Alignment-based adversarial training (ABAT) for improving the robustness and accuracy of EEG-based BCIs. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 32, 1703–1714. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2024.3391936 (2024).

Wang, J., Liu, A., Bai, X. & Liu, X. Universal adversarial patch attack for automatic checkout using perceptual and attentional bias. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 598–611. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2021.3127849 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Interpreting adversarial examples and robustness for deep learning-based auto-driving systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23(7), 9755–9764. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2021.3108520 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. ASK: Adversarial soft k-nearest neighbor attack and defense. IEEE Access 10, 103074–103088. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3209243 (2022).

Huang, Q.-X., Chiang, L.-K., Chiu, M.-Y. & Sun, H.-M. Focus-shifting attack: An adversarial attack that retains saliency map information and manipulates model explanations. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 73(2), 808–819. https://doi.org/10.1109/TR.2023.3303923 (2024).

Mascolo, C., Towards adversarial robustness with early exit ensembles.In: 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom, 2022, pp. 313–316, https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC48229.2022.9871347.

Wang, Z. et al. A Feature space-restricted attention attack on medical deep learning systems. IEEE Trans Cybern 53(8), 5323–5335. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2022.3209175 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. RAILS: A robust adversarial immune-inspired learning system. IEEE Access 10, 22061–22078. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3153036 (2022).

Liu, A. et al. Training robust deep neural networks via adversarial noise propagation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 30, 5769–5781. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2021.3082317 (2021).

Zhang, X. & Wu, D. On the vulnerability of CNN classifiers in EEG-based BCIs. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 27(5), 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2908955 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Interpreting and improving adversarial robustness of deep neural networks with neuron sensitivity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 30, 1291–1304. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2020.3042083 (2021).

Byra, M. et al., Adversarial attacks on deep learning models for fatty liver disease classification by modification of ultrasound image reconstruction method.In: 2020 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2020, pp. 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IUS46767.2020.9251568.

Rohanian, O. et al. Privacy-aware early detection of COVID-19 through adversarial training. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27(3), 1249–1258. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2022.3230663 (2023).

Yao, Q. et al. Adversarial medical image with hierarchical feature hiding. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 43(4), 1296–1307. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2023.3335098 (2024).

Xu, M., Zhang, T. & Zhang, D. MedRDF: A robust and retrain-less diagnostic framework for medical pretrained models against adversarial attack. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41(8), 2130–2143. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2022.3156268 (2022).

Jaffino, G., Jose, J. P., Pv, E., Dhineshbabu, N. R. & Kit, C. C. Seizure detection in EEG signal using Gaussian-Stockwell transform and Hermite polynomial features. Results Eng. 23, 102684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102684 (2024).

Aissa, N. E., Korichi, A., Lakas, A., Kerrache, C. A. & Calafate, C. T. Assessing robustness to adversarial attacks in attention-based networks: Case of EEG-based motor imagery classification. SLAS Technol 29(4), 100142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slast.2024.100142 (2024).

Murugan, T. K. & Kameswaran, A. Employing convolutional neural networks and explainable artificial intelligence for the detection of seizures from electroencephalogram signal. Results Eng 24, 103378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103378 (2024).

Schirrmeister, R. T. et al. Deep learning with CNNs for EEG decoding. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38(11), 5391–5420. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23730 (2017).

Kingma, D. P., & Ba, J. (2014). Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980., https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980.

Devi, S., Singh, K., Singha, N., & Singh, M. K. (2024). A comparative analysis for EEG-based motor imagery classification across diverse datasets. In: 2024 First International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Signal Processing (ICECSP) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

Zhao, W. et al. CTNet: A convolutional transformer network for EEG-based motor imagery classification. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20237 (2024).

Zhao, W. et al. Multi-scale convolutional transformer network for motor imagery brain-computer interface. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 12935 (2025).

Zhao, W. et al. TCANet: A temporal convolutional attention network for motor imagery EEG decoding. Cognit Neurodyn 19, 91 (2025).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Vellore Institute of Technology. No funding was received for conducting this study and preparation of manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jebin Samuel: Contributed to the development of the hierarchical CNN architecture, implementation of data preprocessing techniques, and conducted adversarial training experiments. Tamilarasi Kathirvel Murugan: Conceptualized the research framework, supervised the overall study, provided clinical relevance interpretation, and led the manuscript preparation. Logeswari Govindaraj: Assisted in literature review, dataset acquisition, and preprocessing pipeline including CSP filtering and EEG artifact handling. Madhan Balaji: Designed the experimental protocol for motor imagery and execution tasks, contributed to model evaluation under cross-subject scenarios, and statistical analysis. Vikkram SenthilKumar: Focused on the generation of adversarial examples and implementation of robustness validation metrics across different threat models. Sreenevedh Sundararajan: Supported software integration, performance benchmarking, and helped with visualization and result interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samuel, J., Murugan, T.K., Govindaraj, L. et al. Adversarial robust EEG-based brain–computer interfaces using a hierarchical convolutional neural network. Sci Rep 16, 4353 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34024-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34024-0