Abstract

In the modern world, individuals with intellectual or communication disabilities face significant challenges in communicating with others. To reduce their communication difficulties, a communication system is designed and developed to convert sign language into text and speech. Dynamic hand gesture recognition (HGR) is a preferred option that focuses on human–computer interactions (HCI). HGR investigation is obtaining increasing attention from investigators globally. Also, regular application in day-to-day life, gesture recognition (GR) is beginning to enter education, virtual reality, automotive, mobile devices, and so on. Owing to the massive growth in artificial intelligence (AI), computer vision (CV)-based GR systems are the most extensively researched field recently. This paper presents a Feature Fusion-based Hand Gesture Recognition for Sign Language Accessibility using the Tornado Optimisation Algorithm (FFHGR-SLATOA) model to aid hearing- and speech-impaired people. The aim is to develop an innovative deep learning-based HGR model to enhance communication accessibility for hearing- and speech-impaired individuals. The image pre-processing stage begins with median filtering (MF) to improve image quality by removing noise. Furthermore, the fusion of ConvNeXt Base, VGG16, and EfficientNet-V2 techniques is employed for the feature extraction process. Moreover, the FFHGR-SLATOA approach employs the deep belief network (DBN) model for classification. Finally, the tornado optimization algorithm (TOA) model is implemented for the parameter tuning process. The experimental analysis of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach is performed under the GR dataset. The comparison study of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach portrayed a superior accuracy value of 99.14% over existing models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Across the globe, there are 466 million individuals who are hearing- and speech-impaired, and out of them, 34 million are children1. World health organization (WHO) reports that it might rise to 900 million by the year 2050. Genetic factors and birth-related issues, etc., cause hearing impairment. Sign language helps people in the signing community connect with the general population2. Inside a family, a hearing- and speech-impaired person may use unique methods to communicate, so there is no necessity for standard sign language gestures, but while talking with the hearing- and speech-impaired person, one should utilize the standard sign language gestures3. On this platform, the interaction is like an HCI. When it comes to sign language recognition, it is highly challenging to acquire appropriate input data due to numerous factors, including the environment and complications in the sign language data4. In everyday life, people communicate through speech and use gestures to guide, indicate, and emphasize their points. Gestures are more suitable and natural for HCI, making a stronger link between humans and machines. For many hearing-impaired and deaf person, sign language is their main way of expression and forms a deep part of their cultural and social identity5.

HGR is employed in human–robot interaction (HRI) to form user interfaces that are user-friendly and beginner-friendly. Sensors leveraged for HGR comprise external sensors, namely video cameras, and wearable gadgets, like data gloves6. Video-based GR tackles such problems; however, it poses a novel issue: finding the hand and separating it from the background in a sequence of images is a challenging task, specifically when there are variations in lighting, obstructions, fast movements, or the presence of skin-colored objects in the background7. Data gloves may deliver precise movement and hand posture measurements; however, they need wide calibration, limit natural hand motion, and are costly. Creating HGR systems, like sign language applications, is crucial to address the communication barrier with individuals who are unfamiliar with sign language8. Technology that spontaneously interprets hand gestures into audible speech or text for a non-signing person to understand can assist in reducing this barrier. Because of the significant advancement in camera technology and AI, CV-assisted gesture detection systems have become a commonly studied research area currently9. Deep learning (DL) techniques have received considerable attention from the academic community and businesses swiftly, as they are powerful and have attained better performance in the HGR area10.

This paper presents a Feature Fusion-based Hand Gesture Recognition for Sign Language Accessibility using the Tornado Optimisation Algorithm (FFHGR-SLATOA) model to aid hearing- and speech-impaired people. The aim is to develop an innovative deep learning-based HGR model to enhance communication accessibility for hearing- and speech-impaired individuals. The image pre-processing stage begins with median filtering (MF) to improve image quality by removing noise. Furthermore, the fusion of ConvNeXt Base, VGG16, and EfficientNet-V2 techniques is employed for the feature extraction process. Moreover, the FFHGR-SLATOA approach employs the deep belief network (DBN) model for classification. Finally, the tornado optimization algorithm (TOA) model is implemented for the parameter tuning process. The experimental analysis of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach is performed under the GR dataset. The key contribution of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach is listed below.

-

The FFHGR-SLATOA method improves input quality by applying the MF model for image pre-processing, effectively mitigating noise. This step ensures cleaner data for subsequent processing, contributing to an enhanced feature extraction and classification accuracy within the GR process.

-

The FFHGR-SLATOA technique integrates a fusion of ConvNeXt Base, VGG16, and EfficientNet-V2 models for extracting rich and diverse features from gesture inputs, enabling more robust and discriminative representations. This fusion significantly improves the model’s ability to capture intrinsic spatial patterns, resulting in higher recognition accuracy.

-

The FFHGR-SLATOA approach implements the DBN technique for robust and hierarchical classification of gesture inputs, effectively capturing intrinsic feature relationships. This improves the decision-making capability of the model, contributing to more accurate and reliable GR across diverse input discrepancies.

-

The FFHGR-SLATOA model utilizes the TOA technique for fine-tuning the parameters of the model, thus enhancing the overall accuracy and convergence. This intelligent optimization effectively improves the effectiveness and adaptability of the model and also plays a crucial part in improving the performance across varying GR scenarios.

-

The novelty of the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology is in its unique integration of multi-CNN feature fusion, DBN-based hierarchical classification, and TOA-driven parameter optimization. This incorporates allows for effective extraction, classification, and optimization. The model is also commonly explored in prior GR studies. This results in a highly efficient, scalable, and accurate end-to-end recognition framework.

Section "Related works" presents the related works in the field of hand GR for hearing- and speech-impaired individuals. Section "The proposed methodology" describes the proposed methodology, followed by Section "Experimental validation", which outlines the experimental validation of the approach. Finally, Section "Conclusion" concludes the study with a summary of the findings’ directions.

Related works

Alabduallah et al.11 presented a new Sign Language Recognition through Hand Pose alongside a Hybrid Metaheuristic Optimiser Algorithm in DL (SLRHP-HMOADL) method for hearing-impaired persons. The methods aim to focus on HGR for enhancing the efficacy and precision of sign language understanding for deaf individuals. Alaimahal et al.12 proposed an innovative result using the ability of DL models, long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, for addressing specific problems. This method concentrated on estimating and identifying movements made by people with disabilities depending on consecutive frames of activities. This ground-breaking service of LSTM and DL approaches presents a real-world solution to overcome communication barriers and helps to advance accessible technologies. Singhal et al.13 explored the employment of vision-based HGR to address communication problems encountered by people who are deaf or hard of hearing in HCI. Emphasizing the barriers presented by sign language interpretation and traditional communication techniques, this study presents the dumb aid phone system as a new solution. Shegokar et al.14 introduced a new adaptive sign language detection network, which merges CNN with the histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) method. The system bridges the communication gap between hearing and deaf individuals by effectively identifying dynamic and static gestures utilizing a classic web camera. This tool, which is projected to be both cost-effective and accessible, eliminates the necessity for expensive hardware, permitting broader application.

In15, an innovative Inverted Residual Network Convolutional Vision Transformer-based Mutation Boosted Tuna Swarm Optimiser (IRNCViT-MBTSO) model is suggested to recognize both hand sign languages. The presented dataset is intended for identifying diverse dynamic names, and the anticipated images are pre-processed to enhance the model’s generalization potential and improve image quality. The local features are captured with the help of feature graining, whereas global features were extracted from the pre-processed images by the ViT transformer algorithm. Tan et al.16 introduced the stacking of distilled ViT (SDViT) for HGR. Firstly, a pre-trained ViT containing a self-attention mechanism is presented to efficiently identify complex associations among image patches, thus augmenting its ability to manage the difficulty of higher-order relationships in hand signals. Then, knowledge distillation is presented to constrain the ViT model and refine the model’s generalizability. Alyami and Luqman17 recommended the Swin multi-scale temporal perception (Swin-MSTP) architecture, where the Swin transformer (Swin T) is employed as the spatial feature extractor that can capture clear spatial information and deliver a greater contextual interpretation among SL components in video frames.

The proposed methodology

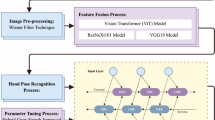

In this manuscript, a FFHGR-SLATOA technique is proposed to aid hearing- and speech-impaired people. The primary objective of this paper is to propose a novel DL-based HGR technique to enhance communication accessibility for hearing- and speech-impaired individuals. It comprises distinct levels of image pre-processing, fusion of transfer learning, classification, and parameter tuning methods. Figure 1 illustrates the overall process of the FFHGR-SLATOA model.

MF-based image pre-processing

Initially, the image pre-processing phase applies MF to upgrade image quality by eliminating the noise18. MF preserves crucial edge details that are considered significant for accurate hand gesture recognition. Also, this model avoids edge blurring compared to other models such as Gaussian or mean filters, thus ensuring that gesture contours remain sharp for feature extraction. This model is also more appropriate for real-time applications due to its simplicity, computational efficiency, and robustness.

MF is a nonlinear digital filter method usually used to eliminate noise from images, which is particularly effective in preserving edges, while removing impulse (salt-and-pepper) noise. In the field of HGR, MF is used in the pre-processing stage to improve the quality of the image before feature extraction. By substituting each value of the pixel with the median of neighbouring pixel values, this filter smooths the image without blurring significant details such as finger edges or hand contours. This is important to maintain the precision of gesture shape detection. MF also facilitates decreasing background interference and enhancing segmentation performance. Therefore, it improves the reliability and robustness of the HGR system, particularly after addressing real-time video input or variable lighting states.

Fusion of feature extractor

Besides, the fusion of ConvNeXt Base, VGG16, and EfficientNet-V2 techniques is employed for the feature extraction process19. The fusion model appropriate maximizes the feature learning capability of the technique. Among the fusion techniques, ConvNeXt enable efficient comprehension of intrinsic visual patterns while also maintaining computational efficiency. Additionally, VGG16 provides a simple yet effective hierarchical convolutional structure, enhancing gradual abstraction and robust spatial feature extraction. Furthermore, MBConv blocks are utilized by the EfficientNet-V2 technique for ensuring robust generalization and low computational cost. Also, the fusion operation is accomplished via concatenation to integrate the high-level features extraction from the prior layer into a unified, discriminative representation. This fusion also effectually integrates the merits of all three architectures, improving accuracy, robustness, and overall performance in hand gesture recognition.

ConvNeXt base model

ConvNeXt Base is an innovative CNN structure that exemplifies a significant advancement in the CV field. Although not as generally recognized as a few conventional structures, it has gathered attention for its strong feature extraction abilities and computational efficacy. Outstanding for its use of grouped convolutions, layer normalization (LN), and random depth regularisation, this model targets to strike a subtle balance between model performance and complexity. Regarding performance, it has shown promise in different image classification tasks. For example, investigators have applied ConvNeXt Base to classify composite medical images, such as those associated with tumour recognition in histopathological analysis and mammography. Its capability to take complex visual designs while preserving computational complexity makes this model an excellent selection for different applications. Structurally, this model consists of a sequence of CNBlocks, all featuring permutations, grouped convolutions, and linear transformations. These blocks, boosted with random depth layers, assist in improved model strength and generalizability. Additionally, this model utilizes LN and several activation functions to seize complex patterns successfully.

VGG16 method

VGG16 is an innovative CNN structure that has left a permanent mark on the image classification environment. Well-known for its effectiveness and simplicity, it remains a basis in the domain even with the development of innovative models. Its structural design, consisting of repeated blocks of convolutional layers followed by max‐pooling operations and rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions, selects spatial downsampling and feature extraction. Practically, this model is widely applied in numerous CV tasks, ranging from image recognition to object localization. Its direct model and robust performance make it a preferred choice for benchmarking and experiments in research settings. Structurally, it contains a hierarchical model of convolutional layers, developed by max pooling operations and ReLU activation functions. This model promotes hierarchical feature extraction, allowing the method to capture gradually abstract representations as information passes through deeper into the network. Moreover, the combination of max‐pooling layers helps spatial down-sampling, lowering computational efficiency, while preserving selective information.

EfficientNet-V2

EfficientNet-V2 has emerged as a prominent model in the field of efficient and scalable CNN structures, exemplifying advanced developments in model optimization and design. To attain the best performance through changing computational budgets, EfficientNet-V2 has gained widespread recognition for its adaptability to different deployment settings. Its structural design, described by the normal convolutional layer succeeded by fused MobileNet-V2 (MBConv) blocks, exemplifies efficacy without compromised classification precision. In practical contexts, this model has proven phenomenal efficiency through a range of tasks, from image classification to object detection. Its hierarchical model and strategic combination of stochastic depth layers lead to improved model strength and generalizability. Structurally, it consists of a cascade of MBConv blocks, all feature depth‐wise separable convolutions and effective channel attention mechanisms. This model fosters effective feature aggregation and extraction, allowing the method to take composite visual forms while reducing computational complexity. In addition, the use of random depth layers improves regularisation of the model, contributing to enhanced performance on different datasets. Figure 2 represents the structure of the EfficientNet-V2 technique.

Classification using DBN model

Followed by, the FFHGR-SLATOA model utilizes the DBN technique for the classification process20. This technique is robust in modelling intrinsic, high-dimensional feature distributions. Additionally, the model enhances weight initialization and generalization and is also exhibit efficiency over standard deep MLP or softmax head techniques by pretraining each layer in an unsupervised manner. DBNs is capable of effectively capturing complex dependencies when applied to a fully connected classification head on the fused CNN features. The model is also computationally lighter and easier to train compared to transformer-based models, thus making it appropriate for real-time applications. Moreover, they outperform simpler and more efficient classifiers in handling hierarchical and nonlinear feature interactions. DBN is also well-aligned with the fused CNN feature structure, due to their ability in utilizing both unsupervised pretraining and supervised fine-tuning.

A restricted Boltzmann machine (RBM) is a two-part graphical model that consists of a visible layer (VL) and a hidden layer (HL), highlighting end-to-end communication amongst layers and no intra-layer connectivities. The DBN is a DL structure established in probability-based visual representation, including several layers of RBMs ordered in a stacked formation. The DBN’s ability to automatically learning higher‐level conceptual characteristics from data gives an essential benefit in handling higher‐dimensional, nonlinear datasets. The RBM acts as the basic component of the DBN. The nodes within VL describe the input data, while the nodes within HL are used to learn the feature data representation. During RBM, all nodes are displayed as the binary stochastic variable in their state, subject to the weights and states of the linked nodes. The model of contrastive divergence (CD) is proficient at learning the likelihood distribution of the data, aiding either feature learning or data generation.

The bottom layer of the DBN method uses a multi-layer RBM architecture. A greedy model is applied to train the sample data layer-by-layer. The parameters gained from the CD-based training of the initial layer of RBM serve as input for the next layer of RBM, and this procedure is reiterated for subsequent layers. The training procedure is described as unsupervised learning. This layer‐wise pre-training approach successfully deals with the gradient vanishing problem encountered in deep network training, improving either generalizability or training efficiency. The model is not restricted to treating it as a sequence issue; instead, the idea of phase space reconstructions from physics and mathematics is applied to describe and evaluate the intricate behaviour of dynamical methods. The basic concept of space reconstructions is to convert time-series data into a collection of points in phase space, facilitating a complete understanding of the model’s features and evolution. It allows the transformation of the new 1D time series into higher‐dimensional phase space vectors. These higher-dimensional space vectors can then act as inputs to the DBN, permitting it to additionally handle these vectors to remove important nonlinear features and implement dimension reduction. In detail, start with a univariate time series \(x\left( t \right)\). In contrast, t begins from 1 to \(N\) (using \(N\) to represent the dataset length), the phase space reconstruction converts \(x\left( t \right)\) into the vector \(z\left( t \right)\) in a \(d\)‐dimensional area, as demonstrated:

whereas, \(d\) is specified as the embedded dimensions that govern the space complexity, and \(m\) signifies the delay time that determines the time interval between data points. To choose suitable values for delay times and embedded dimensions, it is promising to take the internal model of the time series inside the phase space.

TOA-based parameter tuning process

Finally, the parameter tuning process is carried out through TOA to strengthen the classification performance of DBN21. This model optimizes parameters and illustrates efficiency in searching the hyperparameter space. Also, the model improves DBN accuracy and generalization and provides faster convergence, compared to manual tuning or grid search. TOA also avoids local minima, thus ensuring more robust performance. The method is also considered computationally efficient than other metaheuristic methods. TOA ensures that the model fully utilizes the discriminative power of the fused CNN features and maintains high optimization quality, resulting in robust, reliable hand gesture classification. TOC is also a heuristic optimizer model derived from the natural process of tornadoes. This model mimics the communications between windstorms, tornadoes, and thunderstorms, combining the biological phenomena of the Coriolis force to handle the searching procedure and finally discover the global best solution. This model mimics the succeeding biological phenomenon:

Tornadoes It characterizes the best solution in the present population using robust attraction abilities.

Thunderstorms It symbolizes sub-optimum solutions using particular local searching capabilities.

Windstorms They characterize normal solutions that are responsible for exploring the searching region. By mimicking the communications between these natural processes (like windstorms developing into thunderstorms and tornadoes) and joining the actual properties of the Coriolis force, this model may effectively balance exploitation and exploration in the searching area. In the model’s initialization, a specified number of tornadoes, windstorms, and thunderstorms are created. Each location of the individual is distributed at random within the searching region, and its fitness value is measured. The upgrades for the speeds and windstorm locations are implemented based on Eqs. (2)–(4). The parameters for this work are fixed as a population size of 50 and 300 iterations.

The storm location upgrades include dual sections: evolution towards the tornado and the thunderstorm. The evolution towards the tornado is as demonstrated:

whereas, \(x_{i,j}\) refers to the location of the \(ith\) storm in the \(jth\) size, \(x_{tornado}\) refers to the tornado’s position in the \(jth\) dimension, \(\alpha\) means random weight, and \(v_{j}\) stands for the velocity of the \(ith\) storm in the \(jth\) size. The evolution towards the thunderstorm is as shown:

Here, \(x_{thunderstorm,j}\) denotes thunderstorm’s position in the \(jth\) dimension, \(x_{tornado}\) signifies tornado’s position in the \(jth\) dimension, and \(rand\) means a randomly generated number from a uniform distribution.

The storm’s speed upgrade is subject to the Coriolis force, and the equation is as demonstrated:

Now \(, v_{i,j}\) denotes the velocity of the \(ith\) storm in the \(jth\) dimension, \(\eta\) represents the scaling factor, \(\kappa\) means the inertia weight, \(c\) refers to the random coefficient, \(f\) indicates the Coriolis force coefficient, \(R\) illustrate the radius parameter, and \(CF\) symbolizes the Coriolis force term. Algorithm 1 illustrates the TOA model.

Table 1 portrays the hyperparameters of the TOA method. This model is initialized with a population size of 50, highlighting the overall tornadoes, thunderstorms, and windstorms, and is run for 300 iterations to optimize the solution.

The TOA originates a fitness function (FF) to achieve enhanced performance of classification. It defines a progressive number to characterize the improved performance of candidate solutions. In this paper, the minimization of the classification error rate is reflected as the FF, as shown in Eq. (5).

Experimental validation

The performance evaluation of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach is investigated under the GR dataset22. The technique is simulated using Python 3.6.5 on a PC with an i5-8600 k, 250 GB SSD, GeForce 1050Ti 4 GB, 16 GB RAM, and 1 TB HDD. Parameters include a learning rate of 0.01, ReLU activation, 50 epochs, 0.5 dropout, and a batch size of 5. The utilized dataset comprises 20,000 images in total under five classes, such as Thumbs UP, Thumbs Down, Left Swipe, Right Swipe, and Stop. Each class has 4000 images.

Figure 3 illustrates the confusion matrices of the FFHGR-SLATOA technique under diverse epochs under the GR dataset. Under epoch 500, misclassifications were higher with diverse gesture instances. As training progressed to epochs 1000 and 1500, the number of correctly classified instances increased, with diagonal entries in the matrices growing larger, highlighting improved per-class accuracy. By epochs 2000 to 3000, the matrices exhibit robust diagonal dominance, emphasizing that most gestures were correctly predicted. Thus, the progression of the confusion matrices clearly highlights consistent enhancement, depicting the efficiency in distinguishing between similar hand gestures over training iterations.

Table 2 depicts the GR of the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology under diverse epochs on the GR dataset. The results suggest that the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology appropriately recognized the instances. On 500 epochs, the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology attains an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.05%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 92.64%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 92.63%, \(F{1}_{score}\) of 92.63%, and \({AUC}_{score}\) of 95.39%. Moreover, on 1500 epochs, the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology attains an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.42%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.06%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 96.06%, \(F{1}_{score}\) of 96.06%, and \({AUC}_{score}\) of 97.54%. Besides, under 2500 epochs, the FFHGR-SLATOA model attains an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.67%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.68%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 96.68%, \(F{1}_{score}\) of 96.68%, and \({AUC}_{score}\) of 97.93%. Finally, under 3000 epochs, the FFHGR-SLATOA model attains an average \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.14%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.85%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.85%, \(F{1}_{score}\) of 97.85%, and \({AUC}_{score}\) of 98.66%. The consistently high metrics across all classes confirm the robustness and reliability of the FFHGR-SLATOA model for real-time sign language recognition applications.

In Fig. 4, the training (TRAN) \(acc{u}_{y}\) and validation (VALD) \(acc{u}_{y}\) results of the FFHGR-SLATOA method under numerous epochs on the GR dataset are exemplified. The \(acc{u}_{y}\) values are calculated through an interval of 0–3000 epochs. The figure underlined that the TRAN and VALD \(acc{u}_{y}\) values show maximal tendencies, indicating the proficiency of the FFHGR-SLATOA technique with enhanced solution through different iterations. Furthermore, the TRAN and VALD \(acc{u}_{y}\) remains nearer through the epoch counts, which signifies lesser overfitting and reveals greater outcomes of the FFHGR-SLATOA technique, ensuring reliable prediction on unseen instances.

In Fig. 5, the TRAN and VALD losses graph of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach under several epochs on the GR dataset is revealed. The loss values are calculated through an interval of 0–3000 epochs. It is depicted that the TRAN and VALD values show a minimal tendency, reporting the ability of the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology in balancing a trade-off between data fitting and generalization. The constant decrease in loss values furthermore safeguards the superior solution of the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology and adjusts the prediction outcomes.

In Fig. 6, the precision-recall (PR) curve examination of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach under diverse epochs on the GR dataset provides insight into its solution by plotting Precision against Recall for every label. The figure shows that the FFHGR-SLATOA approach consistently achieves greater values of PR through diverse labels, representing its proficiency to preserve a substantial part of true positive predictions among all positive predictions (precision), likewise acquiring a considerable proportion of actual positives (recall). The continuous increase in PR solutions across all class labels reveals the efficacy of the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology in the classification procedure.

In Fig. 7, the ROC graph of the FFHGR-SLATOA model under numerous epochs on the GR dataset is examined. The performance suggests that the FFHGR-SLATOA approach accomplishes superior ROC solutions across all classes, representing substantial proficiency in differentiating classes. These consistent trends of maximal ROC values across diverse classes indicate the capability of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach in forecasting class labels, underlining the strong nature of the classification procedure.

Table 3 and Fig. 8 compare the solutions of the FFHGR-SLATOA technique with present methodologies under the GR dataset1,23. The solutions underlined that the RGB + Flow, DenseImage Net, 3DCNN + MLP, 3D CNN, Two-stream CNN-LSTM, Inception LSTM, and Xception-LSTM methodologies have stated poor outcomes. Simultaneously, the projected FFHGR-SLATOA technique informed enhanced outcomes with superior \(acc{u}_{y}\), \(pre{c}_{n}\), \(rec{a}_{l},\) and \({F1}_{score}\) of 99.14%, 97.85%, 97.85%, and 97.85%, respectively.

Table 4 and Fig. 9 indicate the comparison evaluation of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach with existing techniques under the Sign Language MNIST dataset24,25. The CNN attained slightly improved \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 89.00%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 88.70%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 88.00%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 88.50%, while RNN and LSTM exhibited slightly varied performance with an accuracy of 90.00% and 85.00% respectively. Furthermore, Conv LSTM and GRU-LSTM techniques illustrated moderate values with an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 87.00% and 78.89%, highlighting limitations. However, superior values were illustrated by the FFHGR-SLATOA model with an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.56%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.79%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.50%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 97.74%.

Table 5 and Fig. 10 specify the comparison assessment of the FFHGR-SLATOA technique with existing methods under the American Sign Language (ASL) dataset26,27. The LSTM-CNN model reached an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 91.00%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 90.00%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 89.00%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 89.50%, while ML-CNN, DPCNN, VGG16, and LSTM-GRU techniques showed moderate \(acc{u}_{y}\) values ranging from 86.00% to 90.00% and lower \(pre{c}_{n}\), \(rec{a}_{l}\), and \({F1}_{score}\) values. Finally, the FFHGR-SLATOA model illustrated higher \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.77%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.68%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.80%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 97.74%, highlighting its efficiency in capturing both spatial and temporal features.

Table 6 indicates the ablation study analysis of the FFHGR-SLATOA methodology. The DBN with ConvNeXt Base without parameter tuning achieved an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 94.69%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 93.49%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 93.34%, and F1-Score of 93.26%. Additionally, the DBN + ConvNext Base + TOA technique attained an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 95.32%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 94.22%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 94.22%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 94.10%. Likewise, by integrating DBN with VGG16 without tuning resulted in an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 96.01%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 94.82%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 94.95%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 94.81%, additionally increasing to an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 96.73%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 95.59%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 95.59%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 95.71% with TOA. DBN with EfficientNet-V2 without tuning achieved an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.58%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 96.37%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 96.37%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 96.43%, which improved to an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.35%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.14%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.01%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 97.25% with TOA tuning. However, the overall FFHGR-SLATOA technique outperformed all the above combinations with an \(acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.14%, \(pre{c}_{n}\) of 97.85%, \(rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.85%, and \({F1}_{score}\) of 97.85%, thus highlighting efficiency.

Table 7 exemplifies the computational efficiency analysis of the FFHGR-SLATOA model28. The FFHGR-SLATOA model is highly lightweight and fast, requiring only 21.08 G FLOPS, 589 MB GPU memory, and an inference time of 1.67 s. Compared to other methods like YOLOv3-tiny-T and YOLOv7, the FFHGR-SLATOA method illustrates significantly lower computational cost and faster processing while maintaining competitive performance, making it appropriate for real-time deployment.

Conclusion

This paper presents an FFHGR-SLATOA model to aid hearing- and speech-impaired people. The aim is to develop an innovative DL-based HGR model to enhance communication accessibility for hearing- and speech-impaired individuals. Initially, the image pre-processing stage employs MF to upgrade image quality by extracting the noise. Furthermore, the fusion of ConvNeXt Base, VGG16, and EfficientNet-V2 techniques is utilized for the feature extraction process. Moreover, the FFHGR-SLATOA model utilizes the DBN technique for classification. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed by using the TOA model to increase the classification performance of the DBN model. The experimental analysis of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach is performed under the GR dataset. The comparison study of the FFHGR-SLATOA approach portrayed a superior accuracy value of 99.14% over existing models. The limitations include insufficient testing in real-world sign language scenarios, which may restrict its practical applicability. Another limitation includes poor usability and accessibility as no small-scale user-centric or deployment-oriented testing, such as involving real signers, has been conducted. The robustness of the FFHGR-SLATOA model under diverse lighting conditions, backgrounds, and camera types remains ambiguous as the analysis was accomplished on a controlled dataset. Furthermore, the performance of the model is not properly explored with dynamic gestures or continuous sign sequences. Future work may concentrate on large-scale, real-world testing, inclusion of diverse user populations, and evaluation across varying environmental conditions. Improvements could also explore real-time deployment and adaptive learning for personalized gesture recognition.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/imsparsh/gesture-recognition, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/muhammadkhalid/sign-language-for-numbers, https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ayuraj/asl-dataset, reference number22,24,26.

References

Al-Hammadi, M. et al. Deep learning-based approach for sign language gesture recognition with efficient hand gesture representation. IEEE Access 8, 192527–192542 (2020).

Skaria, S., Al-Hourani, A. & Evans, R. J. Deep-learning methods for hand-gesture recognition using ultra-wideband radar. IEEE Access 8, 203580–203590 (2020).

Mujahid, A. et al. Real-time hand gesture recognition based on deep learning YOLOv3 model. Appl. Sci. 11(9), 4164 (2021).

Sugimoto, M., Zin, T. T., Toriu, T. & Nakajima, S. Robust rule-based method for human activity recognition. IJCSNS Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 11, 37–43 (2011).

Côté-Allard, U. et al. Deep learning for electromyographic hand gesture signal classification using transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 27(4), 760–771 (2019).

Almjally, A., Algamdi, S. A., Aljohani, N. & Nour, M. K. Harnessing attention-driven hybrid deep learning with combined feature representation for precise sign language recognition to aid deaf and speech-impaired people. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 32255 (2025).

Moin, A. et al. A wearable biosensing system with in-sensor adaptive machine learning for hand gesture recognition. Nat. Electron. 4(1), 54–63 (2021).

Daniel, E., Kathiresan, V. & Sindhu, P. Real time sign recognition using YOLOv8 object detection algorithm for Malayalam sign language. Fusion Pract. Appl. 1, 135–235 (2025).

Rastgoo, R., Kiani, K. & Escalera, S. Hand sign language recognition using multi-view hand skeleton. Expert Syst. Appl. 150, 113336 (2020).

Basheri, M. Automated gesture recognition using zebra optimization algorithm with deep learning model for visually challenged people. Fusion Pract. Appl. 16(1) (2024).

Alabduallah, B., Al Dayil, R., Alkharashi, A. & Alneil, A. A. Innovative hand pose based sign language recognition using hybrid metaheuristic optimization algorithms with deep learning model for hearing impaired persons. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 9320 (2025).

Alaimahal, A., Vasuki, S., Harini, T. P., Niranjana, B. & Lavaniya, M. Sign language recognition with image processing using deep learning LSTM Model. In 2025 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS) 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Singhal, P., Verma, S., Gupta, R., Kumar, R. & Arya, R. K. February. Vision-based hand gesture recognition system for assistive communication using neural networks and GSM integration. In 2025 2nd International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Technology and Networking (CICTN) 891–895 (IEEE, 2025).

Shegokar, A., Kale, T., Patil, L. & Gupta, P. Sign language detection system using CNN and HOG: Bridging the communication gap for deaf and hearing communities. In 2025 IEEE International Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation (IATMSI) vol. 3 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Vaidhya, G. K. & Anand, G. P. Dynamic Doubled-handed sign language Recognition for hearing- and speech-impaired people using Vision Transformers (2024).

Tan, C. K., Lim, K. M., Lee, C. P., Chang, R. K. Y. & Alqahtani, A. SDViT: Stacking of distilled vision transformers for hand gesture recognition. Appl. Sci. 13(22), 12204 (2023).

Alyami, S. & Luqman, H. Swin-MSTP: Swin transformer with multi-scale temporal perception for continuous sign language recognition. Neurocomputing 617, 129015 (2025).

Herbaz, N., El Idrissi, H. & Badri, A. Advanced sign language recognition using deep learning: A study on Arabic sign language (ArSL) with VGGNet and ResNet50 models (2025).

Aksoy, S. Multi-input melanoma classification using MobileNet-V3-large architecture. J. Autom. Mob. Robot. Intell. Syst. 73–84 (2025).

Liu, Y., Zhao, Z., Zhang, Z. & Yang, Y. A novel sea surface temperature prediction model using DBN-SVR and spatiotemporal secondary calibration. Remote Sens. 17(10), 1681 (2025).

Zhao, X. et al. Optimization design of lazy-wave dynamic cable configuration based on machine learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 13(5), 873 (2025).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/imsparsh/gesture-recognition.

Hax, D. R. T., Penava, P., Krodel, S., Razova, L. & Buettner, R. A novel hybrid deep learning architecture for dynamic hand gesture recognition. IEEE Access 12, 28761–28774 (2024).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/muhammadkhalid/sign-language-for-numbers.

Baihan, A., Alutaibi, A. I., Alshehri, M. & Sharma, S. K. Sign language recognition using modified deep learning network and hybrid optimization: A hybrid optimizer (HO) based optimized CNNSa-LSTM approach. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 26111 (2024).

Kothadiya, D. et al. Deepsign: Sign language detection and recognition using deep learning. Electronics 11(11), 1780 (2022).

Chen, R. & Tian, X. Gesture detection and recognition based on object detection in complex background. Appl. Sci. 13(7), 4480 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024-343

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Najm Alotaibi: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, Reham Al-Dayil: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing Nojood O Aljehane: methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation Mohammed Rizwanullah: software, visualization, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alotaibi, N., Al-Dayil, R., Aljehane, N.O. et al. Enhanced feature fusion with hand gesture recognition system for sign language accessibility to aid hearing and speech impaired individuals. Sci Rep 16, 3998 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34100-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34100-5