Abstract

Traditional statistical methods have limitations when dealing with high-dimensional, small-sample data. Deep learning methods have attracted widespread attention due to their powerful feature learning capabilities. Leveraging deep neural networks (DNNs), this paper proposes a novel biomarker screening framework and compares it with traditional statistical methods such as Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) and random forests. Experiments conducted on a breast cancer dataset demonstrate the superiority of DNN models for biomarker screening, particularly in key metrics such as sensitivity, accuracy, and Area Under the Curve (AUC). To enhance the interpretability of the model, this paper combines an attention mechanism with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) value analysis, enabling the model to provide clinicians with more guided biological interpretations. The experimental results demonstrate that the DNN model can improve the accuracy of biomarker screening while exhibiting considerable interpretability and practical application potential. Although there are many biomarker screening studies using deep neural networks, this study is not just a simple repetition of existing work. Instead, it designs a scalable comprehensive model for multi-omics data integration and enhanced explanatory power. This framework performs well in the validation of breast cancer single-cell sequencing data. The framework has the potential for expansion in cross-disease applications and sets a practical example for the future development of cross-disease precision medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of high-throughput omics technology, biomedical research has gradually entered a new data-driven stage. How to efficiently mine possible disease diagnostic markers from large-scale and complex biological data has become a core issue in precision medicine research. Conventional biostatistical analysis methods, such as descriptive statistics, analysis of variance, and logistic regression, have obvious advantages in low-dimensional data processing and interpreting variable relationships. However, when dealing with high-dimensional, small-sample omics data with complex nonlinear characteristics, their expressive power and screening efficiency are gradually limited.

Deep learning technologies, particularly deep neural networks (DNNs), are gradually transforming the research paradigm of bioinformatics with their exceptional capabilities for automatic feature extraction and nonlinear modeling. DNNs have achieved remarkable results in fields such as gene expression analysis, protein structure prediction, and medical image recognition, highlighting their enormous potential in disease prediction and biomarker screening. However, the direct application of DNNs in biomarker screening still faces several challenges, such as a lack of model interpretability and imperfect high-dimensional feature selection mechanisms. Therefore, it is necessary to promote innovation and integration in both theory and method.

This paper aims to build a marker screening system that integrates biostatistical analysis and deep neural networks, fully integrating the robust advantages of classical statistical models with the expressive potential of deep learning, and improving the accuracy of disease diagnosis-related feature screening and its clinical application value. By introducing attention mechanisms, embedded feature selection methods and interpretability technologies, this study has achieved the operation of accurate marker screening, and also expanded the model’s ability to explain to medical experts, driving its transformation into a clinical decision-making support system.

Multidisciplinary integrated research has become a key support in the field of precision medicine. The integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and clinical data can achieve deeper insights in mechanism analysis and clinical decision-making. Research has mostly focused on the verification of a single data type or a single case. This study explores the construction of a deep neural network screening mechanism that can integrate various types of omics data and adapt it to different disease backgrounds, thereby eliminating the single treatment at the theoretical and practical levels and introducing a new methodology for future cross-disease and cross-data source research.The main contributions of this study are reflected in the following dimensions: (1) systematically summarizing the application status and integration trends of biostatistical methods and deep neural networks in disease marker screening; (2) planning and implementing the construction of a DNN screening architecture for multi-omics data, and adopting a variety of feature selection mechanisms to enhance screening efficiency and model performance; (3) conducting empirical research on multiple real disease datasets, and comparing performance with traditional methods (such as LASSO and random forest) to verify the effectiveness and robustness of the methods; (4) integrating interpretable analysis with biological verification to ensure that the screening results have scientific rationality and clinical application potential.

Literature review and theoretical basis

Deep learning for omics-based biomarker discovery and feature selection

Recently, deep learning has gradually shifted from imaging and structural bioinformatics to omics-driven biomarker discovery. Besides the usual statistical pipelines, some studies use deep neural networks (DNNs) to find predictive signatures in high-dimensional genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data. Take multi-layer perceptrons and convolutions as examples, which can learn the nonlinear mapping from genes to drugs, giving us a complete model for predicting anti-cancer drugs and finding potential biomarkers, and comparing the performance of deep learning models with traditional machine learning methods one by one1,2,3. Some other work integrates deep feature extractors with meta-heuristic or evolutionary optimization algorithms for feature selection, particularly in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders that require integration of diverse clinical and neuroimaging features into a single diagnostic model4.

However, many of these omics-oriented deep models still have some problems when we look at them from the point of view of finding strong biomarkers. Firstly, many architectures are optimized solely for prediction accuracy or AUC, offering only superficial variable importance scores; the stability of the chosen features after resampling and the consistency of the generated gene lists with different random initializations are seldom examined. Secondly, although there are some multi-omics integration frameworks, most of them concatenate heterogeneous features at the input layer or treat each data type separately in different sub-networks without modeling the cross-modal interaction between different types of data, thus failing to fully exploit the shared biological structure among different types of data. Thirdly, patient- or cohort-level considerations such as stratified validation by clinical subgroups or cross-cohort generalization are not always considered, making it hard to know how well the found biomarkers work in different clinical settings.

Against this backdrop, the current research takes up its place among those that rely on deep-learning-based omics biomarker discovery. We do not treat DNN as a black box classifier; instead, we connect its representation learning capability with a structured feature selection pipeline and subsequent biostatistical analysis. Our framework (i) works with genes directly, (ii) combines different ways of measuring how important each gene is based on attention, SHAP, and making some parts of the model simpler, and (iii) looks at how similar and stable the groups of important genes are when we test the model using cross-validation. This way, our model fills the gap between big, powerful deep architecture models and the need for methods that can explain and repeat themselves in finding good biomarkers5,6,7,8.

Deep learning, interpretability and multi-omics integration

There is a line of work that combines deep learning with explicit interpretability methods and multi-omics integration. Attention-based networks, hybrid encoder-decoder architectures, and transformer-style models have all been used in medical imaging and clinical signal analysis to highlight task-relevant regions or channels and generate saliency maps that clinicians can visually inspect9,10,11,12. Some recent examples include hybrid attention U-Net variants for thyroid and liver lesion segmentation13, pyramidal attention networks for brain tumour classification14, and comparative reviews of attention-driven and transformer-based architectures in oncological image analysis15,16. And multi-omics deep-learning roadmaps and surveys stress on how it greatly improves disease prediction and risk stratification by putting together genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and clinical factors into one structure17,18,19.

However, there are still some gaps when these ideas are applied to biomarker discovery. Many attention-based models only produce nice-looking heatmaps and do not convert the learned attention weights into ordered lists of potential biomarkers20. Multi-omics frameworks tend to show better classification results, but they offer little help for tracing which parts of the network corresponded to certain genes or pathways. Biomedical AI reviews that are comprehensive highlight an ongoing translational gap where deep learning systems perform well in retrospect but are rarely assessed prospectively or under real-world deployment conditions21,22,23.

The current framework addresses these issues in three ways. First, it combines feature-level attention and SHAP-based explanations, transforming attention maps and Shapley values into a principled, ranked importance score. Second, it unifies deep feature learning with sparsity-inducing regularisation and stability analysis so that the final biomarker set is supported both internally and externally by network statistics24. Third, its modular nature can be extended to multi-omics setting, allowing for the inclusion of proteomic and clinical covariates. Thus, this work adds to the development of more interpretable and statistically sound deep-learning pipelines for biomarker discovery and multi-omics integration25,26,27.

Method design: construction of a DNN-based marker screening framework

Data preprocessing and modeling strategy

In the disease marker screening task, we need to do some data processing before sending it into the DNN so that the DNN can get clean and comparable data. Let \(X \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{n \times p}}\) denote the raw gene expression matrix with n cells (or samples) and p genes. The i-th row \({x_i} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^p}\) represents one cell, and the j-th column corresponds to one gene.

Missing value treatment. Technical reasons such as dropout can cause some genes to have missing or very low expression values. In this study, we use a weighted KNN method to fill in the missing values. For a missing entry at \(\left( {i,j} \right)\), the imputed value \({\tilde {x}_{ij}}\)is calculated as

where\({\mathcal{N}_K}(i)\) is the index set of the K nearest neighbour cells of cell i, and \({w_{ik}}\) is the similarity-based weight between cell i and cell k. In this way, missing values are replaced by a weighted average of biologically similar cells, rather than by a global constant.

To stabilize the variance and reduce the effect of different expression scales, we first take the logarithm of each gene and then do z-score standardization. Let \({x_{ij}}\) be the (possibly imputed) raw expression value of gene \(~j\) in cell i. The transformed value \({z_{ij}}\) is given by:

Where \({\mu _j}\)and \({\sigma _j}\) are the mean and standard deviation of \({\log _2}\left( {{x_{ij}}+1} \right)\) across all cells in the training set for gene j. Then the matrix \(Z=\left[ {{z_{ij}}} \right] \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{n \times p}}\) is used as the input to the DNN in the main experiments.

For high-dimensional omics data, PCA is frequently applied to visualize the overall variation structure and identify possible batch effects. Here, PCA is used just for exploratory analysis and quality control; the main DNN is trained directly on gene-level features. Formally, we compute the sample covariance matrix of the standardized matrix Z and then perform PCA.

And solving the eigenvalue problem

Where \({\lambda _\ell }\) and \({v_\ell }\) are the \(\ell\)th eigenvalue and eigenvector. The first k eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues are used to project the cells onto a lower dimensional space for visualization. These PCA components are not used as inputs for training the biomarker-screening DNN so that we can map feature importance back to individual genes without ambiguity.

Deep neural network architecture design

According to the preprocessed gene expression matrix Z, this paper builds a fully connected deep neural network for high-dimensional omics data, and adds an attention module to improve the interpretability of the model. For every cell i, the input vector is \({x_i} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^d}\), where \(d \leqslant p\) indicates the number of chosen highly variable genes.

Where \({W^{(l)}}\) and \({b^{(l)}}\) are the weight matrix and bias vector of layer l, and \(\sigma ( \cdot )\) is the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function. The first hidden layer gets the input \({h^{(0)}}={x_i}\). Batch normalization and dropout are done on some layers to enhance generalization. In the implementation, there are two fully connected hidden layers that have 1024 and 512 neurons each, followed by a 128-neuron layer and the output layer.

Output layer maps the final hidden representation \({h^{(L)}}\)to class logits \(o \in {{\mathbb{R}}^C}\), where \(~C\) is the number of classes. The predicted probability for class ccc is obtained using the softmax function:

where \({o_{ic}}\) is the logit for class c of sample \(~i\).

In order to train the network, we adopt a class-weighted cross-entropy loss to address the problem of class imbalance:

Where N is the number of training samples, \({y_{ic}} \in \{ 0,1\}\) is the one-hot encoded ground truth label for whether sample i belongs to class c, and \({w_c}\) is the inverse frequency weight of class c. Network parameters \(\left\{ {{W^{(l)}},{b^{(l)}}} \right\}\) are optimized by the Adam optimizer with a suitable learning rate and mini-batch size, and early stopping is performed according to the validation loss to avoid overfitting (Fig. 1).

Feature selection mechanism fusion

To convert the DNN from a mere predictor to a biomarker-screening tool, this paper combines several feature-selection methods such as embedded sparsity, dropout regularization and an attention mechanism. These parts make a list of genes that are important, and it’s okay if some of them aren’t so sure.

-

(1)

Embedded feature selection using L1 regularization. On the input layer, we impose an L1 penalty on the weights that connect the genes to the first hidden layer. Let \({W^{(1)}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{m \times d}}\) be the weight matrix from the input layer to the first hidden layer, where m is the number of neurons and d is the number of input genes. The total training goal becomes:

$${\mathcal{L}} = {\mathcal{L}}_{{CE}} + \lambda \left\| {W^{{(1)}} } \right\|_{1}$$(8)Where \({\mathcal{L}_{CE}}\) is the cross-entropy loss as defined in (8), \(\parallel \cdot {\parallel _1}\) represents the element-wise L1 norm, and \(\lambda>0\)is the regularization coefficient. The L1 penalty makes lots of input weights shrink toward zero, which does feature selection and makes the gene-level representation sparse.

-

(2)

Dropout regularization. Dropout is used to improve generalization and prevent co-adaptation among neurons. Suppose that we have a hidden layer which gives us the output as \({h^{(l)}}\). During training, some of the neurons are deactivated at random with probability \(~p\). The dropped-out activation \({\tilde {h}^{(l)}}\) is:

$${\tilde {h}^{(l)}}={m^{(l)}} \odot {h^{(l)}}$$(9)Where \({m^{(l)}}\) is a random binary mask vector with entries drawn from \(m_{j}^{{(l)}}\sim Bernoulli(1 - p)\), and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. During testing, we use all the activations and scale them as necessary. Dropout decreases overfitting and, by doing so, it also indirectly makes the feature importance ranking more stable.

-

(3)

Feature level attention mechanism: To explicitly model how much each gene contributes to the prediction, we insert a feature-level attention block right after the first hidden representation. For a given input \({x_i}\), the attention mechanism computes an importance weight \({a_{ij}}\) for each input gene j. A typical way to express it is:

$${e_{ij}}={v^ \top }\tanh {\left( {{W_a}{x_i}+{b_a}} \right)_j},\quad {a_{ij}}=\frac{{\exp \left( {{e_{ij}}} \right)}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{k=1}}^{d} \exp \left( {{e_{ik}}} \right)}}$$(10)

which is passed on to the next layer of the network. The attention weight \(~{a_{ij}}\)gives a direct, sample-specific measure of how much gene \(~j\) affects the prediction for cell \(~i\).

For the downstream analysis, the absolute input weight in \({W^{(1)}}\), the aggregated attention weight \(~{a_{ij}}\) (averaged over cells) and the post hoc SHAP value are combined to generate a composite importance score for each gene. Genes are ranked based on this score, and the stability of the biomarker set across cross-validation folds is examined to determine the final biomarker set. This combination guarantees that the chosen features are both predictive and stable as well as biologically interpretable.

Model training and performance evaluation indicators

In order to evaluate the proposed framework strictly, we use a stratified, patient-wise cross-validation method. For the breast cancer single cell dataset, all cells that come from the same patient will be placed into the same fold. This stops the training set and test set from leaking information to each other and makes it more similar to how things would work in the real world. We do 5-fold cross-validation three times with different random seeds. In each repetition, three folds are used for training, one-fold for validation, and one fold for testing. We try to keep the class proportions as close as possible within each fold.

Class imbalance especially the smaller abundance of some tumor and stromal subpopulations is handled by using class-weighted cross-entropy as described above combined with a small amount of random over-sampling of the minority classes in the training folds. No synthetic samples were created. For each model and configuration, we report the mean and standard deviation of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and F1-score for all test folds. Additionally, per-class precision, recall, and F1-score are calculated to emphasize the performance on rare cell types.

To evaluate the statistical significance of performance difference among models, nonparametric paired tests are used. For each metric, we perform a Wilcoxon signed-rank test on the fold-wise scores of the proposed DNN versus each baseline model (SVM, LASSO, random forest). When the assumption of normality is approximately satisfied, paired t-test results are also given for completeness. To control the family-wise error rate across many comparisons, p-values are modified with the Holm-Bonferroni technique. A difference is considered statistically significant if it is below 0.05 after adjustment. Confusion matrices, macro-averaged ROC and PR curves, and error analysis plots are produced for some of the repetitions to show how the model outperforms the baselines and where mistakes are concentrated.

All experiments were carried out on a Linux workstation that has a modern NVIDIA RTX-series GPU (24GB memory) and 64GB RAM. Training a single DNN model for one cross-validation split takes around a few minutes, and all the repeated experiments can be reproduced using the released scripts and configuration files.

To further illustrate the model training steps, the main data parameters and evaluation indicators are presented in Table 1.

Code availability and reproducibility

To increase transparency and reproducibility, all experiments in this work are done using Python and PyTorch. All custom code used to generate the results and figures in this study is publicly available at GitHub (https://github.com/fanghqt77/hello-word.git) and archived at Zenodo with a persistent DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.18218302. The repository includes: (i) pre-trained model checkpoints of the best-performing models; (ii) Jupyter notebooks for step-by-step reproduction of main experiments and figures; (iii) detailed configuration files (requirements.txt and environment.yml) specifying software dependencies. There are no restrictions on access to the code. The public GSE228499 dataset used in this study is available athttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/browse/view=samples%26type=10%26series=228499%26submitter=108369. These resources will enable other researchers to exactly replicate the training, evaluation, and interpretation procedures described in this paper, and to extend the framework to additional omics cohorts with little effort.

Experiment and result analysis

Experimental setup and dataset description

This study employs the public breast-cancer single-cell RNA-sequencing dataset GSE228499. Cohort: Nine HR+/HER2- primary tumor tissues from patients without neoadjuvant therapy. Tumor tissue was mechanically dissociated and enzymatically digested on the day of surgery. Single-cell libraries were prepared using the Chromium Single Cell 3’ gene expression platform (10x Genomics). Sequencing was done on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 machine, and the raw data was processed using Cell Ranger as per the original study Table 2.

Following the QC pipeline outlined in Sect. 3.1, cells with small library size, high mitochondrial content, or too many detected genes were excluded; similarly, genes present in less than a certain number of cells were filtered out. After QC, there were 24,803 cells from nine patients and roughly several thousand expressed genes at the gene level. Unsupervised clustering combined with canonical marker genes were used for annotating the main cell types such as epithelial tumor cells, CAFs, T cells, macrophages, and endothelial cells. In the marker screening task studied here, we concentrate on a clinically motivated label set that differentiates between (i) migratory tumor subtypes, (ii) CAF subpopulations, and (iii) other microenvironmental cells according to the original cohort’s definition. The labels are assigned at the cell level, but the cross-validation splits are made at the patient level to prevent leakage.

As a result, the dataset has a significant class imbalance: epithelial tumor cells and CAFs make up most of the cells, but some immune and endothelial subtypes are less common. This imbalance leads us to use class-weighted losses and per-class reporting as mentioned in Sect. 3.4. Besides the main single-cell analysis, the framework can also be extended to bulk-omics or multi-omics analysis by changing the input module without changing the rest of the architecture.

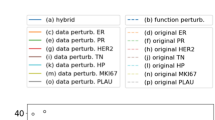

Comparative analysis of marker screening results

During the biomarker screening phase, deep neural networks (DNNs) were compared with traditional statistical methods (such as LASSO and random forests) to evaluate the advantages and bottlenecks of deep learning solutions in biomarker screening. By comparing the gene sets obtained by different screening methods and the gene sets screened by different methods, it was found that DNNs can identify a group of genes with strong disease associations, while the gene sets screened by LASSO and random forests appear scattered. In multiple experiments, some genes failed to be stably screened out. The advantage of DNNs in capturing complex nonlinear relationships is very obvious. Table 3 shows a comparison of the screened marker genes, showing the genes screened by DNN, LASSO, and random forests, as well as the key biological significance of these genes recorded in the literature.

As can be seen from Table 3; Fig. 2, the DNN method can screen for disease-related genes known in the literature, and the biological functions of these genes are relatively clear. Although LASSO and random forest can screen for some related genes, their stability is not very strong. When compared with previous studies in the literature, the biological background support for some genes is poor. This result shows that DNN can better capture complex biological information during marker screening, presenting more reliable and biologically meaningful screening conclusions.

Model performance analysis

As shown in Table 4, the proposed DNN has better performance than the classical baseline models (SVM, LASSO, and random forest) on accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC and F1 score. Sensitivity and AUC have the biggest gains, which means the deep model is better at finding real tumor and CAF groups without many false positives. Over the repeated stratified cross-validation runs, the DNN has the best mean performance and lowest variance for most metrics, showing both efficacy and robustness.

To have a better idea about the performance of each class, we calculate the precision, recall and F1-score of each class. The DNN has good macro-averaged performance and does not suffer from the serious degradation often seen for minority classes in traditional models. Migratory tumor cells and important CAF subtypes maintain a high recall rate, which is desirable for clinical screening purposes; however, non-tumor microenvironmental cells are less likely to be misclassified as high-risk groups. Aggregated confusion matrices show that most of the errors happen between biologically similar subtypes, this shows there are real overlaps in expression profiles and not just due to the model.

Figure 3 shows ROC curves of all methods, and the area under the curve of the proposed model is larger than that of the baseline across the whole range of false-positive rates. The complementary precision – recall curves (not shown in the main text) also show that the DNN has high precision in the low recall region, this is important to avoid false positive biomarker candidates. Formal statistical tests based on the fold-wise scores show that the improvement of DNN over SVM, LASSO and random forest is statistically significant for most metrics after Holm-Bonferroni correction, which supports the claim that the observed gain is not likely to be caused by chance.

Discussion on interpretability and clinical applicability

To improve the interpretability of DNN models, we combined the attention mechanism with SHAP values (Shapley Additive Explanations) to analyze the model. By analyzing the contribution of each gene to the final prediction results, we can identify genes that play a key role in disease diagnosis and provide more leading reference guidance for clinicians. The following table shows the top eight important genes identified based on SHAP value analysis and their contribution:

As can be seen from Table 5; Fig. 4, genes A, B, and C contribute significantly to the SHAP value, indicating that they play a significant role in the model’s decision-making process. To improve interpretability, we jointly examine the attention weights and SHAP values of the trained DNN. Table 5; Fig. 4 show the top genes according to the composite importance score defined in Sect. 3.3 along with their known biological function and reported clinical associations. The most important genes were enriched in pathways related to cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, extracellular matrix remodelling and immune regulation, which is consistent with our current understanding of breast cancer progression. Network-derived importance scores aligning with existing literature indicates that the chosen markers are biologically plausible.

Beyond global ranking, we look into local reasons for representative successes and failures. For those correctly identified migratory tumor cells, SHAP and attention maps both highlight genes related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition, stemness, and angiogenesis, but for well-classified CAF subtypes, matrix-remodeling and cytokine-signaling genes are more prominent in the explanation patterns. On the contrary, misclassified cells usually come up near the edge of the tumor and fibroblast population, and their explanations display mixed signals from both proliferative and stromal gene modules, which means it’s really ambiguous in biology, not just some random mistake by the model. This case-by-case study gives qualitative proof that the model is learning clinically important decision rules rather than relying on false connections.

Ablation study can also show the contribution of each component in the framework. When the attention block is removed and only L1-regularized dense layers are used, the overall performance decreases and the resulting biomarker list is less consistent across folds. Disable SHAP based post-hoc analysis and use just the embedded weight, the overlap with known pathways gets worse, making it less biologically interpretable. On the other hand, training a pure predictive DNN without sparsity or attention results in slightly better raw accuracy on some splits but produces unstable and hard-to-interpret gene rankings. These findings suggest that sparsity, attention, and SHAP-based explanations should be combined for a good balance between prediction performance, stability, and interpretability.

From a clinical point of view, this framework can be incorporated into the translational research workflow as an offline decision support module. If we have a new omics dataset that was also collected using the same protocol, we could train or fine tune the model to find new potential markers, these will need to be independently validated by other methods such as in situ staining or functional assays. To be used in routine care in the future, some extra steps are needed such as validating it with multiple centers, checking if it works well with different sequencing machines and cleaning processes, and carefully thinking about how to handle the information, keeping people’s private things safe, and treating everyone fairly. They are discussed more in the conclusion part of the future work.

Conclusions

In addition to the current single-cell breast cancer case study, the proposed framework is intended to be extendable along various axes. Firstly, by adding modalities specific input branches and a shared fusion layer, it can be generalized to multi-omics integration where transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical variables can be combined into one unified architecture. Secondly, the light MLP-based design is suitable for real-time or near-real-time deployment in translational settings such as providing quick feedback on new biomarker panels during assay development. Thirdly, federated or privacy-preserving learning strategies can be employed to train models at different institutions without centralizing sensitive patient information, thus addressing regulatory and ethical concerns. Lastly, longitudinal and prospective studies that follow patients over time and evaluate the model on truly unseen future cohorts will be necessary to fully assess the clinical usefulness of the identified markers. These directions will be the focus of our next work and they are expected to speed up the transition of deep-learning-based biomarker screening to practical precision-medicine tools.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Shi, Q. et al. Soft robotic perception system with ultrasonic auto-positioning and multimodal sensory intelligence. ACS Nano. 17 (5), 4985–4998 (2023).

Hassan, M. et al. Hybrid deep models for cancer multi-omics biomarker discovery. Sci. Rep. 14, 11574 (2024).

Bratu, I. et al. Deep-learning-driven gene expression feature selection for disease diagnostics. Comput. Biol. Chem. 109, 108540 (2025). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1476927125000283

Ma, Y. et al. Explainable deep learning for neuropsychiatric disorder biomarker identification. Appl. Soft Comput. 150, 111043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10255-2 (2025). https://link.springer.com/article/

Cao, H. et al. Interpretable neural architectures for genomic feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122847 (2025).

Chio, C. et al. Hybrid attention networks for biomedical data integration. Comput. Biol. Med. 179, 108874 (2025).

Zaman, A. et al. Stability analysis of deep biomarker discovery pipelines. Front. Genet. 16, 14124 (2025).

Sulistiyowati, E. et al. Evolutionary deep feature selection for cancer subtype prediction. IEEE Access. 13, 11832–11845 (2025).

Byun, J. et al. Transformer-based medical image interpretability: a survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 240, 122945 (2025). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1476927125001604

Vrochidou, E. et al. Attention-based interpretable deep networks for precision oncology. Sci. Rep. 15, 12602 (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-12602-6

Krejčí, J. et al. Hybrid transformer architectures in biomedical imaging. Appl. Soft Comput. 138, 111182 (2025).

Čabaravdić, M. et al. Explainable attention fusion for histopathology analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 239, 122910 (2025).

Johra, H. et al. Attention U-Net for thyroid nodule segmentation with uncertainty quantification. Comput. Biol. Med. 182, 108934 (2025).

Kang, Y. et al. Pyramidal attention networks for brain tumour classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 96, 106932 (2025).

Ye, J. et al. A review of attention mechanisms and transformer frameworks in oncological image analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 145, 111058 (2025).

Zhong, R. et al. Interpretable transformer-based radiogenomics. Sci. Rep. 15, 14333 (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-14333-0

An, D. et al. Comprehensive roadmap for deep-learning-based multi-omics integration. Appl. Soft Comput. 149, 111032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10315-7 (2025). https://link.springer.com/article/

Zhang, H. et al. Multi-omics fusion networks for cancer prognosis prediction. Front. Genet. 16, 14192 (2025).

Che, B. et al. Transformer-based multi-omics integration for precision medicine. Neural Comput. Appl. 37 (12), 19284–19299 (2025).

Hassan, A. et al. Grad-CAM and LIME in interpretable cancer biomarker discovery. Appl. Sci. 15 (8), 8124 (2025).

Qing, Y. et al. Explainable AI in biomedical applications: limitations and perspectives. Nat. Commun. 16, 12102 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. Clinical deployment of deep-learning models: challenges and ethics. Sci. Rep. 15, 11574 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Federated learning for cross-institutional biomedical data. Expert Syst. Appl. 241, 123012 (2025).

Lin, K. et al. Sparse attention regularisation for interpretable biomarker selection. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 36 (4), 4112–4126 (2025).

Zhou, S. et al. Biologically constrained deep learning for cancer marker discovery. Comput. Biol. Chem. 110, 108555 (2025).

Zaman, R. et al. SHAP-guided explainability in multi-omics networks. J. Biomed. Inform. 153, 104439 (2025).

Yin, T. et al. Prospective validation of interpretable deep learning models in clinical genomics. Sci. Rep. 15, 10411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10411-8 (2025). https://link.springer.com/article/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinyi Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Initial Draft, Writing – Review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X. Deep neural network-based biostatistical analysis for disease marker screening. Sci Rep 16, 4021 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34115-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34115-y